This chapter presents an overview of the global legal landscape regarding gender-based violence (GBV): it begins with a description of existing international and regional legal instruments designed to promote gender equality and women’s empowerment. The chapter highlights similarities and differences among different national legal frameworks that govern various forms of GBV, including domestic violence, rape, and sexual harassment as well as female genital mutilation (FGM) and child marriage. It concludes with good practices and recommendations for more comprehensive legal systems. The findings are based on the Social Institutions and Gender Index (SIGI) and on 24 countries’ responses to the SIGI Gender-Based Violence Legal Survey (SIGI GBV Legal Survey).

Breaking the Cycle of Gender-based Violence

2. Strong legal frameworks: a necessity to end and prevent gender-based violence

Abstract

In this report, “gender” and “gender-based violence” are interpretated by countries taking into account international obligations, as well as national legislation.

Key findings

Many women and girls experience diverse forms of gender-based violence (GBV) that may begin in the post-natal period and can persist and overlap through adulthood and through to the end of their lives. Women and girls are exposed to the threat of GBV in all spheres of their lives.

While most countries have acknowledged the importance of legal frameworks and have introduced significant legal reforms to combat GBV, only a limited number of countries included in the fifth edition of the Social Institutions and Gender Index (SIGI) provide for a comprehensive legal framework – i.e. one that protects victims/survivors from all forms of violence.

The persistence of informal laws (traditional, customary or religious laws) can undermine the enforcement of the codified formal law. Preventing and ending GBV thus requires transforming discriminatory informal laws and underlying social norms, along with legal reforms.

In almost all OECD countries and SIGI GBV survey participants, the legal provision on domestic violence comprises physical, sexual and psychological abuse. However, 11 OECD countries do not account for economic violence.

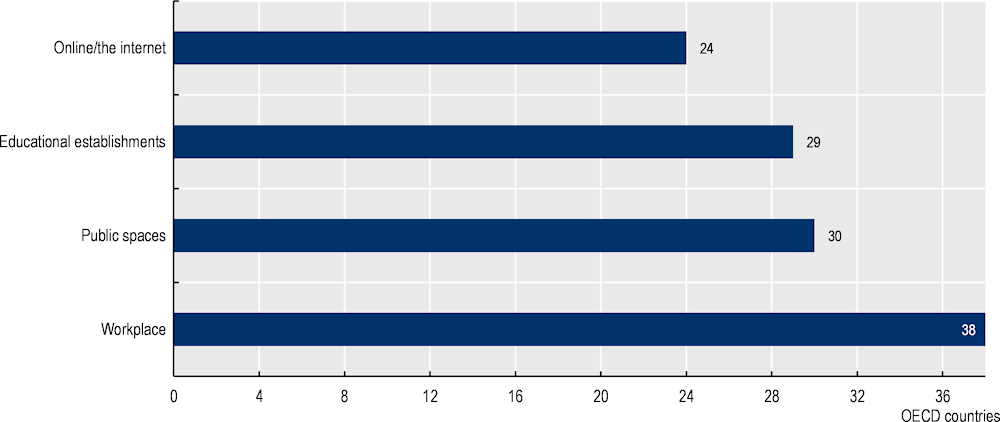

Cyber harassment, a specific form of sexual harassment is an increasing threat to women and girls’ well-being and participation in the online space, yet this form is least covered by countries, in comparison to legislation covering the workplace, educational establishments or public places.

While all OECD countries criminalise rape under their legal frameworks, only 22 countries base their legal definition of rape on the lack of consent. Coercion-based definitions of rape are still used in 16 OECD countries, which can constitute a high legal threshold and a barrier to justice.

Evidence shows that FGM is practiced in OECD countries. Countries have taken action to protect girls from the harmful practice and more than half of OECD countries have laws that explicitly prohibit FGM. This, however, still leaves many young girls at risk, as FGM does not stop at national borders.

While most countries have set 18 as the minimum age of marriage for girls and boys, 25 OECD countries allow legal exceptions for child marriage.

2.1. The international community has established important normative frameworks and benchmarks on GBV

GBV manifests in various forms and can occur throughout a woman’s lifecycle (see Figure 2.1). There is not a single sphere (economic, social, political, psychological, etc.) in women’s lives where they are not exposed to the threat or reality of GBV. Domestic violence in the family and home is ubiquitous. In their lifetime, women and girls may also experience some form of sexual harassment in educational institutions, the workplace and in public spaces. Legal provisions to protect women and girls from every form of GBV are indispensable at every level – whether international, regional, national or local. Such legislation not only sends a strong signal that GBV is a serious crime but can also contribute significantly to changing harmful social norms so that victims’/survivors’ human rights are effectively protected. Adopting and implementing holistic laws that take into account and respond to the experiences of all victims/survivors is a vital component of the Systems Pillar (see Figure 1.2 and discussed in Chapter 3).

Figure 2.1. Gender-based violence is a lifelong continuum that mainly affects women and girls

In recent decades, the international community has developed global and regional minimum standards for GBV. The latest General Recommendation No. 35: Violence against women of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) requires States Parties to “have an effective and accessible legal and services framework in place to address all forms of gender-based violence” (United Nations, 2017[2]). Furthermore, parties must provide “appropriate protective and support services” to victims/survivors (United Nations, 1992[3]). The CEDAW describes GBV as an “obstacle to the participation of women, on equal terms with men, in political, social, economic and cultural life” (United Nations, 1979[4]). This Convention, intended to eliminate all forms of discrimination against women, was ratified by all but seven countries,1 making it almost universal. The CEDAW provides for a mandatory reporting mechanism, as “States parties are required to submit a periodic report on the progress made every four years”, allowing for monitoring of legislative and regulatory changes in combating GBV globally (United Nations, 1992[3]). More recently, the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Target 5.2 called on countries to “eliminate all forms of violence against women and girls” by 2030 (United Nations, 2016[5]).

While legislation alone will not eradicate GBV, comprehensive legal frameworks that protect women and girls from all forms of GBV constitute a vital step in putting an end to impunity and societal acceptance of GBV. Progressive legal frameworks need to be complemented by a change in social attitudes towards women’s rights and gender equality. This is necessary to empower women and girls to claim their rights by addressing the lack of information, limited legal literacy and restricted access to the justice system (see Chapter 6). Comprehensive legal frameworks should ensure that girls and women are protected from all forms of GBV including domestic violence and intimate partner violence, rape and marital rape, honour crimes and sexual harassment – without any exceptions or legal loopholes. It also requires legally codified provisions for the investigation, prosecution and punishment of these crimes, as well as protection and support services for victims/survivors (OECD, 2019[6]). Laws and policies should also embed an intersectional approach that considers various factors and forms of discrimination and oppression. For instance, victims/survivors are exposed to individual experiences of oppression, as gender discrimination interacts with other factors such as race, ethnicity, class, income, caste, education level, or health. Therefore, an intersectional and comprehensive approach that includes all actors in society is needed to ensure that women and girls enjoy their human rights.

2.1.1. Despite some progress, no countries have developed legal frameworks that address GBV holistically

Worldwide, only 12 countries have a legal framework that comprehensively protects girls and women from GBV. Five OECD countries and seven non-member countries legally protect girls and women from the following forms of violence: intimate partner violence; rape, including marital rape; honour crimes; and sexual harassment – without any exceptions or legal loopholes. For instance, this requires that domestic violence laws define and criminalise all types of abuse (physical, sexual, psychological and economic violence) and that laws on sexual harassment apply in all places (including educational establishments, online violence or public places) and are not limited to the workplace only. While the majority of countries still have a long way to go, these 12 countries represent major progress at the global level as there was no country with a comprehensive legal framework in the fourth edition of the Social Institutions and Gender Index (SIGI) in 2019 (see Box 2.1) (OECD, 2019[6]; OECD Development Centre/OECD, 2023[7]).

Box 2.1. The Social Institutions and Gender Index (SIGI) and the SIGI GBV Legal Survey 2022

Since 2009, the OECD Development Centre has measured discrimination in social institutions globally. The SIGI assesses the level of discrimination that girls and women face in formal and informal laws, social norms and practices. This captures the underlying, often “hidden” drivers of gender inequality and makes it possible to collect the data necessary for transformative policy and norm change. The SIGI is also one of the official data sources, together with UN Women and the World Bank Group’s Women Business and the Law for monitoring the SDG 5.1.1 indicator “Whether or not legal frameworks are in place to promote, enforce and monitor gender equality and women’s empowerment”.

The SIGI framework adopts the life cycle approach to better understand GBV against women and girls (see Figure 2.1). The SIGI framework (Ferrant, Fuiret and Zambrano, 2020[8]) measures legal frameworks on three primary counts. First, national legal frameworks; second, enforcement and monitoring of national action plans, programmes and policies aimed at eradicating all forms of GBV; and third, informal (customary, traditional, religious) laws/rules that restrict women’s control over their own lives. While this chapter places a special focus on legal progress and shortcomings, it is also well-documented that there is no single cause of GBV. Some of the strongest and most persistent drivers of GBV are embedded in harmful social norms and the perpetuation of social practice. The SIGI is the only tool that systematically captures the existence and prevalence of informal laws.

To assess the status of the legal frameworks on GBV, identify legal loopholes and showcase good practices, in 2022, the “SIGI GBV Legal Survey” was conducted among 24 member countries of the OECD Development Centre. The fifth edition of the SIGI Global Report will be published in 2023 and will be dedicated to discriminatory social institutions. The forthcoming report will also provide information on the areas where further action is needed to eradicate GBV in 178 countries.

Note: This survey was part of the OECD Horizontal Initiative “Taking Public Action to End Violence at Home”, carried out by the Development Centre, the Directorate for Employment, Labour and Social Affairs (ELS) and the Directorate for Public Governance (GOV). The countries that participated in the SIGI Gender-Based Violence Legal Survey are Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, the Czech Republic, Denmark, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Finland, Guatemala, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Kazakhstan, Korea, Mexico, the Netherlands, Panama, Peru, Portugal, Romania, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain and the Republic of Türkiye.

Source: Ferrant, Fuiret and Zambrano (2020[8]), “The Social Institutions and Gender Index (SIGI) 2019: A revised framework for better advocacy”, OECD Development Centre Working Papers, No. 342, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/022d5e7b-en.

Nevertheless, countries have made efforts to strengthen their institutional responses to GBV, as discussed throughout the report. Some countries provide a more comprehensive and supportive response to victims/survivors of GBV and recognise the intersectional dimension of GBV. Within Canada’s National Action Plan to End Gender-Based Violence, particular attention is paid to being “gender-informed/sensitive and inclusive, intersectional, trauma- and violence-informed, and culturally appropriate” in preventing GBV. The collection and management of data on concerns of Lesbians, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, Intersex, Queer (LGBTIQ+), non-binary and Indigenous persons is particularly promoted. The government has aimed to strengthen the implementation of family and criminal laws by providing training for judges on gender and diversity (Government of Canada, 2021[9]). This approach aims to enable awareness-raising at all levels to remove the obstacles to women and gender-diverse individuals’ equal participation in society. See some promising steps towards reforming legal frameworks for more comprehensive responses to GBV in Box 2.2.

Box 2.2. Comprehensive legal reforms to strengthen responses to GBV

Mexico

Mexico is a signatory and ratifying party to the Inter-American Convention on the Prevention, Punishment and Eradication of Violence against Women (better known as the Belém do Pará Convention), a legally binding international treaty criminalising all forms of violence against women. In accordance with the convention, Mexico has introduced important legal reforms, including a “General Law on Women’s Access to a Life Free of Violence” in 2020.

The law recognises several types of GBV, including psychological violence, physical violence, patrimonial violence, economic violence and sexual violence, and “any other analogous acts that harm or may harm the dignity, integrity or freedom of women” and femicide. The law aims to eradicate violence in all spheres of women’s lives, and dedicates several articles to violence at the workplace, educational institutions and unions.

Besides the expanded recognition of types of violence against women and girls, the law provides an extensive overview of the roles and responsibilities of governmental agencies and ministries, as well as public service providers in the fight against GBV, in the areas of implementation, co-ordination of policy, capacity building and data collection. The law is also victim/survivor-centred, and introduces specific actions to improve their treatment, protection and their access to justice.

Spain

Following the recommendations of GREVIO in 2020, Spain has introduced several legal reforms to expand its protection of victims/survivors of violence, under the new Organic Law 10/2022 of comprehensive guarantee of sexual freedom. The law strengthens existing protection mechanisms for victims/survivors of IPV and extends it to victims/survivors of other forms of GBV, including sexual violence, forced marriages and female genital mutilation. Moreover, legal provisions on psychological violence, stalking, sexual violence, sexual harassment and against the exploitation of prostitution are strengthened.

For example, certain provisions expand protection to victims of online violence and violence in the digital environment, especially for victims under the age of 16. In Spain, Article 172 of the Criminal Code criminalises a wide range of stalking, which it defines as repeated and insistent behaviour to physically approach the victim, communicating with the victim using any available means, stealing personal information or engaging in any other similar activity. The Spanish Criminal Code recognises several areas and means of stalking and Spain has become one of the first European countries to criminalise stalking through digital means of communication or “cyberstalking”. If perpetrators are the partners, ex-partners or close relatives of the victim/survivor, this constitutes an aggravating factor.

The legal reform included several measures to expand protection. It adopted the inclusion of an intersectional approach, as well as a gender perspective. It also introduced the right to reparation. The new law introduced provisions for strengthening the capacity of professionals in the teaching, educational field, health and social services, security forces, in judicial career and in the forensic and prison system, through training and professional specialisations. Finally, the reform adopted an obligation to strengthen institutional responses, by developing a State Prevention Strategy and evaluating and monitoring the new law.

Source: (MESECVI, 2020[10]; EELN, 2022[11]).

Despite the progress individual countries have made in strengthening their laws against GBV, further efforts are needed to ensure that legal frameworks capture the multiple dimensions of GBV. Some do now allow legal loopholes. Furthermore, “plural” legal systems and informal laws can increase women’s and girls’ vulnerability to GBV. Plural legal systems refer to co-existing legal systems, such as the co-existence of state judicial courts bound by a country’s national law and traditional courts that make decisions based on customary law and practices. In some non-OECD countries, such systems can create challenges to effectively enforcing laws against GBV for all groups of women and girls. Informal laws2 undermine the reach and enforcement of legal provisions. Such traditional, customary or religious rules and laws are often undocumented and deeply rooted in society and, combined with discriminatory social norms, weaken the implementation of codified gender-sensitive laws and policies and justify harmful practices.

2.2. Gaps in national legal frameworks on domestic violence put women at risk

As with broader forms of GBV, OECD countries have made some progress in adopting comprehensive laws on specifically tackling domestic violence. Yet a range of legal loopholes persist.

2.2.1. Laws on domestic violence do not adequately protect women from all forms of abuse

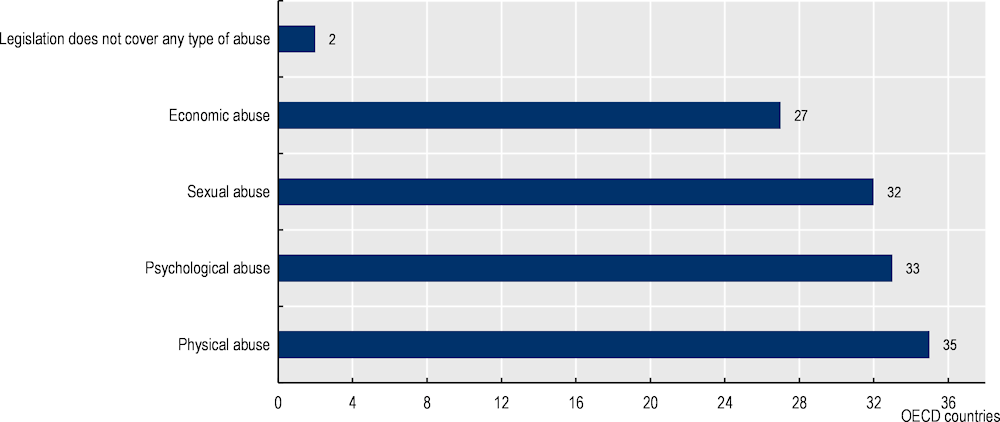

Despite widespread recognition of domestic violence as a criminal offence, legal loopholes persist. While 32 OECD countries reported criminalising domestic violence, six countries either do not have legislation on domestic violence at all, or existing legislation does not extend to the entire territory or domestic violence is only covered in civil legislation (OECD Development Centre/OECD, 2023[7]). Moreover, some countries with criminal or civil provisions on domestic violence fall short of addressing all of its forms. Nonetheless, progress is underway as countries update their legislation (see Box 2.3). Most OECD countries reported having adequate provisions for physical, sexual and psychological abuse. However, economic abuse is only covered in 27 countries. This is a recognised form of domestic violence that involves limiting a partner’s access to economic resources or preventing them from getting a job. Accounting for this type of domestic abuse is essential, because it is harder to escape an abusive relationship for victims/survivors who are economically dependent on the perpetrator and cannot support themselves. While 32 countries reported covering sexual abuse in a domestic relationship as an offence, the law in 10 OECD countries does not explicitly prohibit marital rape.

Figure 2.2. Economic abuse is the form of domestic violence least covered in legal frameworks

Source: OECD Development Centre/OECD (2023[7]), “Gender, Institutions and Development (Edition 2023)”, OECD International Development Statistics (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/7b0af638-en (accessed on 01 June 2023).

To address domestic violence through legislation comprehensively, countries should review legal loopholes and mechanisms to protect victims/survivors. For instance, they can ensure that mediation is permitted fairly and consensually. In cases that involve intimate partners, such as marital disputes and even domestic violence, alternative dispute resolution (ADR) is often encouraged by society. Among OECD countries, only ten OECD countries3 reported prohibiting mediation and/or conciliation in domestic violence cases. Arguments supporting ADR note that it is a faster, more flexible and affordable process for the resolution of interpersonal disputes. Yet for successful mediation processes, the Committee on the Elimination of Violence Against Women provides “the free and informed consent of victims/survivors and that there are no indicators of further risks to the victims/survivors or their family members” (United Nations, 2017[2]).

Box 2.3. Legal reforms on domestic violence towards covering all forms of abuse

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom has taken several significant steps to align its definition of domestic violence with the Istanbul Convention, before its ratification in 2022. The Domestic Abuse Act 2021 has introduced for the first time a statutory definition on domestic violence, covering several forms of domestic violence, including i) physical or sexual abuse; ii) controlling or coercive behaviour; iii) economic abuse; iv) psychological, emotional or other abuse. The Act also stipulates that there is no requirement of repetition of domestic violence for prosecution. Economic violence is also defined under the Act, as any behaviour that has a substantial adverse effect on another person’s ability to i) acquire, use or maintain money or other property, or ii) obtain goods or services.

2.2.2. Social norms lead to under-reporting and failure to prosecute domestic violence

Social norms such as victim blaming or the acceptance of domestic violence by women themselves, and the insensitivity/ineffectiveness of law enforcement agencies, can lead to under-reporting of crimes of domestic violence. Victim-blaming attitudes generally contribute to forging a climate of tolerance that reduces action against domestic violence, makes it more challenging for women to come forward, and promotes social indifference. Awareness-raising is needed to break the silence of victims/ survivors, decrease the levels of social acceptance and increase social responsibility, by promoting individual and collective actions and measures concerning domestic violence against women. Moreover, encouraging reporting of crimes by concerned actors such as caretakers or NGOs can increase support for victims/survivors of domestic violence, and over time, address this tolerance and acceptance in society.

In addition, restrictive norms of masculinity, such as that “real” men should be the breadwinner, or that they should dominate financial, sexual or reproductive choices, can lead to intimate partner violence, especially when these norms are challenged. Evidence shows that men who report feeling stressed about insufficient or lack of work, or feeling ashamed about their financial or economic situation, are almost 50% more likely to commit violence against their female partner (OECD, 2021[14]). This may create a sense that the violence is justified in the minds of both victims/survivors and perpetrators and discourage reporting of these crimes.

Domestic violence must be tackled at every level, whether legal, societal or individual. There is a strong need to explicitly define and criminalise all types of domestic violence, including marital rape. International guarantees such as the Istanbul Convention4 can provide guidance for countries seeking to enact new legislation or revise current law. It is also important to ensure that the provisions of the law can be implemented and to provide guidelines to bridge the gap between policy and practice. For example, in Finland, the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health aims to comprehensively address domestic and intimate partner violence, by providing recommendations (“soft laws”) to self-governing authorities of cities, municipalities and regions. To highlight the complementary nature of these “soft laws”, the Finnish Institute of Health and Welfare is updating the country’s national structure of social and healthcare services. Moreover, strengthening co-operation between different stakeholders, including governments, Official Development Assistance (ODA) donors, foundations, civil society organisations, private companies and schools, can increase awareness about domestic violence and help create bridges between various efforts at the legal, societal and individual levels.

2.3. Consent-based legal frameworks on rape are a good sign of countries’ intent to deal with misconceptions about sexual violence

Rape is understood as the unwanted penetration of the body. Distinctions in the definition emerge, concerning such topics as whether the fundamental issue is the absence of consent or the use or threat of force; the orifice of the body being penetrated; and the object doing the penetration. In circumstances where rape is committed as a part of a “widespread or systematic attack directed against any civilian population”, Article 7 of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court recognises rape as a crime against humanity (International Criminal Court, 2011[15]).5

2.3.1. Progressive rape legislation can address societal stigma and acknowledge the victims’/survivors’ physical integrity

All OECD countries have passed laws that classify rape as a criminal offence (OECD, 2019[6]). Moreover, many have progressively adopted more affirmative conceptions of sexual consent. More than half of OECD countries reported having adopted legislation defining rape based on the lack of free consent.6 This understanding of rape emphasises the importance of the voluntary nature of sexual acts, where involuntary sexual acts include intimate-partner rape, rape perpetrated by an acquaintance of the victim/survivor or committed by a perpetrator of the same gender as the victim/survivor. Moreover, a definition based on a lack of freely given consent can address the issues both of bodily integrity and of sexual autonomy. It can also recognise a set of circumstances where the consent may be coercive or where the victim/survivor may be unable to give free consent (for instance, under the statutory age). While a progressive definition of rape is a necessary step in addressing the long-standing issue of sexual violence, countries should make sure to avoid legal loopholes in legislative reforms.

2.3.2. High legal thresholds of proof of rape can create hurdles to punishment

Even with legal recognition of rape and criminal penalties, governments do not effectively address the consequences of this crime, which are felt both at the personal and the societal level. Victims/survivors experience physical and mental trauma and stigma in many societies. This is evident where laws allow for mitigating conditions around sexual violence that require proof of rape by physical force or penetration. In Japan, for instance, evidence of physical force (such as assault) is required to prove rape. Similarly, in Romania, the legal definition of rape involves coercion that makes it impossible for the victim/survivor to defend themselves or express their will (OECD Development Centre, 2022[16]). Defining rape based on the lack of free consent rather than on coercive circumstances, such as physical force, threat or violence, would make these requirements void.

High legal thresholds such as penetration tests can also create obstacles for the victim, especially if police and medical staff are not sensitive to and/or trained to deal with cases of sexual violence. Moreover, they may also result in the belief that other forms of sexual violence are less important. In Colombia, for instance, Article 212 of the Penal Code addresses carnal access. A penetration test, whether with a virile member or with an object, is required to prove the commission of the criminally violent carnal access or of carnal access to a person who is unable to resist (Government of Colombia, 1992[17]).

Quite apart from legal reforms, a myriad of policy actions can be adopted to address rape, prevent it and support victims/ survivors. This removes the previous requirement that to prove rape, victims must prove violence, force or intimidation. Several OECD countries have made progress towards this, by including a lack of consent in the definition of rape and by reducing the legal thresholds for proof of rape (see Box 2.4).

Box 2.4. Legal reforms towards more progressive rape legislation

Iceland

Chapter XXII of Iceland's General Penal Code was amended in 2018 to include the concept of consent in the definition of rape, which is now described as “sexual intercourse or other sexual relations with a person without her or his consent, which is considered to have been given if it is freely stated”. If forms of unlawful coercion have been used, such as violence or threats of violence, consent cannot be considered to have been given. The amendment was intended to encourage a cultural shift for professionals dealing with cases and to reach a broader consensus within society on the definition of rape.

Sweden

In 2018, an amendment to the Criminal Code criminalises all sexual acts with a person “who is not participating voluntarily”. This introduced a definition of rape based on a lack of consent, departing from the previous definition, under which the offence required the use of force, threats or taking advantage of a vulnerable victim. The amendment also introduced two new offences: “negligent rape” and “negligent sexual abuse”. These cover cases where no reasonable measures were taken to establish the victims’/survivors’ consent.

The Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention published an evaluation of the new consent-based law in 2020 and found a 75% increase in prosecutions and convictions of rape since the law was passed. The evaluation also noted that while the reported instances of rape had increased, this was in line with the trend in the years before the new law was passed.

All OECD countries have a long way to go to systematically criminalise different forms of rape, such as marital rape and rape committed by partners of the same gender, but these progressive steps can address misconceptions about rape and signal a political will to combat GBV. As the UN Special Rapporteur on violence against women has noted, governments must bring their legal frameworks in line with international standards to effectively prevent and combat impunity for rape and sexual violence (OHCHR, 2021[21]).

2.4. Sexual harassment perpetuates discrimination in public spaces, educational settings and the workplace

2.4.1. Sexual harassment is present in every aspect of the daily life of girls and women

While all OECD countries, as well as those that participated in the SIGI Gender-Based Violence Legal Survey, increasingly take steps to prohibit sexual harassment (Box 2.5), not all areas are protected by the law (Figure 2.3). All OECD and additional surveyed countries had established explicit regulations for sexual harassment in the workplace. Yet, comprehensive prohibitions on sexual harassment in the workplace nevertheless need to acknowledge hierarchies in the workplace and offer civil and criminal protections. This is critical so that complaints of sexual harassment against managers are not unfairly silenced. Acknowledging workplace hierarchies in sexual harassment protocols can also ensure that victims/survivors do not lose jobs or promotions for filing a complaint. The #MeToo movement demonstrated that workplace harassment remains prevalent. Companies can set up internal complaint committees to review harassment claims or to include arbitration agreements in contracts. Such measures can force employees to settle complaints rather than pursue criminal liability. As part of the OECD Gender Recommendations,7 OECD member countries have committed to implement all appropriate measures to end sexual harassment in the workplace.

Figure 2.3. Cyber harassment is not extensively covered by sexual harassment laws

Source: OECD Development Centre/OECD (2023[7]), “Gender, Institutions and Development (Edition 2023)”, OECD International Development Statistics (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/7b0af638-en (accessed on 14 April 2023).

Public spaces, educational establishments and cyber harassment are not sufficiently covered by the law. About one-quarter of OECD countries do not explicitly include public spaces or educational establishments in their legal framework on sexual harassment. This is an important omission, as school-related GBV can have adverse consequences on students’ lives, including on school attendance, educational outcomes, physical and mental health (UNESCO, n.d.[22]). In addition, in 14 OECD countries, the legal provisions on sexual harassment do not specifically apply to cyber harassment/cyberstalking, an emerging form of sexual harassment (Figure 2.3). Even when laws exist to address online violence, it is often difficult for law enforcement structures and the courts to take action when web-enabled technology is used to commit acts of violence against women and girls. The role of the private sector, especially of internet service providers, is still limited, and national laws often do not recognise the continuum of violence that women experience offline and online (see Box 2.5 for promising practices on legal reforms towards criminalising online sexual harassment).

Box 2.5. Progress towards criminalising online sexual harassment

Austria’s legal reform package for better response to online violence

In 2021, Austria introduced a legal reform package that made it easier to prosecute and convict perpetrators of online violence, completing existing provisions on online stalking, harassment and other forms of online violence. The government also relies on an official reporting organisation against online violence, ZARA (Zivilcourage und Anti-Rasissmus-Arbeit), that advises and supports victims of online violence.

The legal reform is also part of the broader government efforts to regulate online platforms, to increase their responsibility in combating online hate speech.

Greece is criminalising non-consensual pornography

In 2022, Greece introduced a new article in the Penal Code criminalising non-consensual pornography as a distinct crime against sexual freedom. Non-consensual pornography is defined as online gender-based violence where perpetrators post online images, audio or audio-visual materials showing the victims’/survivors’ non-public sexual life. Non-consensual pornography has also been increasing, due to new technologies that perpetrators can use to alter, corrupt and create images, audio or audio-visual materials showing the non-public sexual life of the victims/survivors.

Article 346 criminalises the act of divulging to a third person, or posting in public, a picture or visual or audio-visual material (whether real, corrupted or designed) of a non-public act of a person related to her/his sexual life. It is considered an aggravating factor if the non-consensual pornography i) is posted on the internet or social media with an unidentifiable number of receivers; ii) is posted by an adult against a minor; iii) is posted against a spouse/partner or former spouse/former partner, or against a person living in the same household as the perpetrator, or against a person who is connected to the perpetrator by employment or a service relationship; iv) is posted with the aim of material benefit.

United States’ legal reforms towards a comprehensive framework on online violence

The United States has taken several steps to combat online violence, including creating the White House Task Force to Address Online Harassment and Abuse and by launching a Global Partnership for Action on Gender-Based Online Harassment and Abuse.

The legal framework provided by Title 18 Paragraph 2261A of the U.S. Code aims to address all forms of online violence and distinguishes between the acts of i) cyberstalking; ii) cyber harassment; iii) doxxing; and iv) non-consensual intimate imagery (or pornography). However, laws on the criminalisation of each subtype of online violence vary by state.

Cyberstalking includes the “act of prolonged and repeated use of abusive behaviours online, intended to kill, injure, harass, intimidate, or place under surveillance with intent to kill, injure, harass, or intimidate”.

The legal system also identifies cyber harassment as an online expression targeted at a specific person that causes the individual substantial emotional distress. In many states, the harassment needs to be repeated and the perpetrator must act with the intent to harass, alarm or threaten.

Some states criminalise the act of doxxing in specific professions (healthcare workers, judges, police officers), which includes the act of publishing sensitive personal information online (e.g. addresses or contact information), to harass or intimidate another person.

The District of Columbia and 48 states also criminalise non-consensual intimate imagery, and define it as the act of sharing private, sexually explicit images or videos without the consent of the person featured in them.

2.4.2. Women face barriers in reporting sexual harassment and seeking judicial remedies

Comprehensive legal frameworks on sexual harassment can include both criminal and civil sanctions, although about a quarter of OECD countries still need to make progress in these areas. Even when the law provides for penalties, some victims/survivors may have to bear the additional burden of proving the crime of sexual harassment (also see Chapter 6). Law reforms would be required to help close these gaps and better protect victims/survivors. For instance, the Brazilian Criminal Code provides for civil remedies in cases of sexual harassment that may specifically be applied to sexual harassment cases in the workplace. This can help victims/survivors financially, since they may be provided compensation as reparations for damage (OECD Development Centre, 2022[16]).

It is vital that laws around sexual harassment be constantly updated so that they can adapt to new challenges and technologies. The legal framework should not lag behind technological developments, social relations and workplace rights. When laws on sexual harassment consider identity markers like age, race and class, they can encourage reporting of such crimes. Removing statutory limitations on reporting a crime of sexual harassment against children, for example, allows survivors to come forward years later.

2.5. Laws banning FGM and child marriage can protect girls from negative consequences

2.5.1. FGM is a serious human rights violation with drastic health and economic consequences for women and girls

The international community and states have committed to prioritising the fight against female genital mutilation (FGM) at the international, regional and domestic levels.8 FGM is an extreme form of GBV against women and especially against young girls, who are exposed to this form of violence due to several factors, including, but not limited to: not having the means of protecting themselves, a lack of awareness or difficulties with challenging norms and traditions, and lack of support, prevention and protection systems. Legal protection is therefore particularly important in averting not only immediate health complications, such as severe pain, excessive bleeding or urinary problems, but also long-term complications such as bacterial infections, painful menstruation, pain during sexual intercourse or psychological problems (WHO, 2022[27]). In addition to health complications, mental health problems including post-traumatic disorders can be associated with FGM, sometimes emerging long after the procedure (Wulfes et al., 2022[28]).

International commitments that promote zero tolerance of FGM are of considerable importance, given that FGM does not stop at country borders. In some contexts, girls are taken across national borders to be subjected to FGM in a country where legislation against FGM is either non-existent or more lax. This is known as cross-border FGM. Despite this practice, existing international legal provisions are not fully implemented in many countries, as illustrated by the fact that about half of OECD countries and participants of the SIGI GBV Legal Survey have implemented laws that explicitly prohibit FGM (OECD Development Centre, 2022[16]; OECD Development Centre/OECD, 2023[7]). A good example is Australia, where each state or territory has legal provisions on cross-border FGM. In Germany, not only performing but assisting or persuading others to perform FGM is a criminal offence, even if it is committed abroad. Furthermore, FGM is sometimes only prohibited for citizens, or if the procedure is undertaken on the respective territory that fails to consider the practice of cross-border FGM. Girls who are not citizens but are living in the country and are taken abroad for mutilation are not always covered by the domestic FGM law. In Greece, the extraterritoriality clause applies only in cases where the perpetrator or the victim has Greek citizenship (End FGM European Network, 2021[29]). More information is needed on the global prevalence of FGM, which is often perceived as a practice restricted to certain African countries. The evidence, however, suggests that FGM is practised on every continent (EIGE, n.d.[30]). Reliable and nationally representative data is important to detect and combat FGM effectively, including by prohibiting the practice in the law.

Globally, customary and traditional practices continue to allow and encourage the harmful practice of FGM. Informal laws in many countries support the practice as a rite of passage into womanhood or preparation for marriage, and women and girls who have not undergone FGM may face stigma. In certain Indigenous communities in Colombia, deeply rooted customs and traditions continue to encourage FGM. The sexual and reproductive health of children and women is threatened, for example, because the growth of the clitoris is associated with its ability to develop into a male organ. Girls or women who resist FGM may be rejected by the community (UNFPA, 2020[31]).

Given the seriousness of the offence, laws need to go further than simply prohibiting FGM. They need to be preventative and to provide adequate protection for victims/survivors after the procedure. Most countries fall short of this standard: only 12 OECD countries9 address FGM in a national action plan (OECD Development Centre, 2022[16]). The government of the Netherlands has established a wide range of measures on FGM, compared to other European countries. The legal provisions are embedded in a comprehensive system to end FGM. This includes, for instance, statistical surveys on the prevalence of FGM, local action plans with concrete steps to eliminate FGM for all sectors of society, FGM-related child protection interventions, and compulsory hospital/medical records of FGM. In addition, FGM is recognised as a reason for asylum. However, no specific criminal law provision on FGM would clarify the consequences. Only one case was brought before the criminal court in 2009, indicating that the legal provisions alone are insufficient to counteract this harmful practice.

2.5.2. Children are exposed because legal prohibitions on child marriage are circumvented

Child marriage has been addressed in numerous international agreements (see Box 2.6) that recognise the need for legal protection against this human rights violation against children, disproportionally jeopardising girls’ health and well-being as well as their future economic empowerment. An estimated 110 million girls are expected to marry in the next decade, which has been amplified since the COVID-19 crisis (UNICEF, 2022[32]). Young brides are exposed to dramatic consequences that negatively affect their physical and psychological well-being. Girls who are married off young are more likely to drop out of school, more likely to experience domestic violence and become pregnant as an adolescent. All this has serious consequences not only for them but also for their families and communities (Girls not Brides, 2017[33]).

Box 2.6. International standards condemning child marriage

Child marriage is recognised in international legal instruments as a serious violation of a child’s human rights. Since the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, numerous international treaties and agreements have followed to prevent child marriage and protect the rights of children, including:

The UN Convention on Consent to Marriage, Minimum Age for Marriage, and Registration of Marriages (1962) establishes that all State parties should take ‘legislative action to specify a minimum age of marriage (Articles 1, 2 and 3).

The UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (1979) states that ‘the betrothal and the marriage of a child shall have no legal effect’ (Article 16 (2)).

The UN Convention of the Rights of Child (1989) precluded State parties from permitting or giving validity to a marriage between persons who have not attained the age of majority.

The Protocol to the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa (2003) (known as the Maputo Protocol) (Article 6, clauses (a), (b), (d).

The 2030 Agenda under the Sustainable Development Goals Target 5.3 aims to ‘eliminate all harmful practices, such as child, early and forced marriage’.

Despite the general recognition that child marriage is a serious violation of human rights, legal loopholes, ineffective implementation and inconsistencies in legal frameworks, coupled with discriminatory practices, still allow girls to marry before the age of 18 years. Most surveyed and OECD countries have set 18 as the minimum age of marriage for girls and boys. A law reform for the United Kingdom is underway and will raise the age to 18 years in 2023 (Government of the United Kingdom, 2022[38]). In the United States, the minimum age of marriage varies across states and is as low as 15 years old for girls in the state of Mississippi. Moreover, two thirds of OECD countries allow legal exceptions for child marriage, via parental consent, the court or both (OECD Development Centre, 2022[16]; OECD Development Centre/OECD, 2023[7]). These exceptions on the minimum age of marriage mainly concern the age of girls, which is why greater attention should be given to the gender dimension of violence against children and adolescents.

Even when child marriage is prohibited, with no legal exceptions, there are often no legal sanctions against those who facilitate marriage to a person below the legal age of marriage. Seventeen countries have no provisions that render it illegal to facilitate child marriage (OECD Development Centre, 2022[16]). Measuring the numbers of child marriages and facilitators is even more difficult, as many are never registered. Nevertheless, child marriages are often arranged within social networks, which gives parents a decisive role (Girls Not Brides, 2022[39]). In some cases, it can be in the interest of parents that their daughters are married off to improve their own – often poor – financial situation (UNICEF, 2022[32]). The involvement of third parties must thus be prohibited by law.

Crucial to protecting women is applying the law to all groups of women so that no one is excluded from protection through derogations, as is the case in most OECD countries. Among OECD countries, only Colombia introduces exceptions to the application of the general law prohibiting child marriage: for women belonging to Indigenous groups, Afro-descendants, Raizal, Roma or Gypsies are subject to the rules of their ethnic group and/or community when marrying, under Indigenous jurisprudence and/or customs (OECD Development Centre, 2022[16]). This also indicates that legal frameworks are effective when they address intersectionality because marginalised groups face the brunt of social and economic hardship. This is important to protect the rights of all children and girls. For instance, the right to exercise their jurisdiction is enshrined in Article 246 of the Constitution of Colombia, which creates an option for other regimes that allow child marriage to be legally enforced and for children not to be protected.

Several countries have also recognised the need to raise awareness of the consequences of child marriage (Box 2.7). This means allowing it to be discussed as a societal issue that has many adverse consequences, such as dropping out of school, health complications and limiting girls’ agency. Egypt has a programme to address the problem of girls who are forcibly married not completing their education (General Assembly of the United Nations, 2014[40]).

Box 2.7. Legal frameworks towards the elimination of child marriage

Norway

Norway is a global advocate for eliminating child marriage and banned child marriage in 2018. Since its amendments to the Marriage Act, the age requirement for marriage has been 18, and does not allow for exceptions. The law now also bans Norwegians from marrying abroad if either party is under 18.

In 2019, the government developed Norway’s International Strategy to Eliminate Harmful Practices (2019-2023). This goes beyond domestic actions and measures, making the fight against child, early and forced marriage integral to development co-operation in all areas, from education to healthcare.

Source: Girls Not Brides (2022[41]), Child Marriage Atlas, Norway, https://www.girlsnotbrides.org/learning-resources/child-marriage-atlas/regions-and-countries/norway/

2.6. Policy Recommendations

Legal frameworks: Comprehensive legal frameworks should address various forms of domestic violence and intimate partner violence (physical, sexual, psychological, and economic) and sexual harassment (at work, in educational and sporting facilities, in public spaces and online). They also require legally codified provisions for the investigation, prosecution and punishment of these crimes, as well as protection and support services for survivors.

Regional and international agreements: Governments should commit to signing and ratifying any outstanding regional and international agreements relating to gender equality and GBV.

Definitions of rape: A definition of rape should criminalise rape as a violation of both bodily integrity and sexual autonomy, and explicitly extend to marital rape. A definition based on the lack of freely given consent can address both physical and personal integrity.

Laws on sexual harassment: Laws pertaining to sexual harassment should be constantly updated, so that they can be adapted to new challenges and technologies. This is key, because legal developments should not lag behind technological developments, social relations and workplace rights.

Culture/gender norms: Progressive legal frameworks should be complemented by efforts to develop a victim/survivor-centred culture and a change in social attitudes towards women’s rights and gender equality. This is necessary to empower women and girls to claim their rights by addressing a lack of information, limited legal literacy and restricted access to the justice system.

Laws on FGM and child marriage: Given that FGM does not stop at country borders, countries should enact comprehensive laws that criminalise FGM based on international commitments. To eliminate child, early and forced marriage, governments should ensure that women and men have the same minimum age of marriage of over 18 years, with no legal exception.

References

[36] African Union (2003), Protocol to the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa, https://au.int/sites/default/files/treaties/37077-treaty-charter_on_rights_of_women_in_africa.pdf.

[25] EELN (2022), Country report Gender Equality Austria, European Equality Law Network, https://www.equalitylaw.eu/downloads/5754-austria-country-report-gender-equality-2022-1-06-mb.

[24] EELN (2022), First-ever formal criminalisation of revenge pornography, European Equality Law Network, https://www.equalitylaw.eu/downloads/5720-greece-first-ever-formal-criminalisation-of-revenge-pornography-131-kb.

[11] EELN (2022), New Law on Sexual Freedom ’only yes means yes’, European Equality Law Network, https://www.equalitylaw.eu/downloads/5763-spain-new-law-on-sexual-freedom-only-yes-means-yes-86-kb.

[30] EIGE (n.d.), Data Collection on Violence Against Women, European Institute for Gender Equality, https://eige.europa.eu/gender-based-violence/data-collection (accessed on 20 October 2021).

[29] End FGM European Network (2021), “Greece”, https://map.endfgm.eu/countries/502/Greece (accessed on 13 March 2023).

[8] Ferrant, G., L. Fuiret and E. Zambrano (2020), “The Social Institutions and Gender Index (SIGI) 2019: A revised framework for better advocacy”, OECD Development Centre Working Papers, No. 342, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/022d5e7b-en.

[40] General Assembly of the United Nations (2014), Preventing and eliminating child, early and forced marriage - Report of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, United Nations, New York.

[41] Girls Not Brides (2022), Child Marriage Atlas, Norway, https://www.girlsnotbrides.org/learning-resources/child-marriage-atlas/regions-and-countries/norway/ (accessed on 13 March 2023).

[39] Girls Not Brides (2022), Gender inequality - About child marriage, https://www.girlsnotbrides.org/about-child-marriage/why-child-marriage-happens/ (accessed on 13 March 2023).

[33] Girls not Brides (2017), How ending child marriage is critical to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals, https://www.girlsnotbrides.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Child-marriage-and-achieving-the-SDGs_DAC.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2019).

[9] Government of Canada (2021), The Gender-Based Violence Strategy, https://women-gender-equality.canada.ca/en/gender-based-violence-knowledge-centre/gender-based-violence-strategy.html#what (accessed on 13 March 2023).

[17] Government of Colombia (1992), Penal Code of Colombia.

[23] Government of Greece (2019), Criminal Code.

[38] Government of the United Kingdom (2022), Implementation of the Marriage and Civil Partnership (Minimum Age) Act 2022, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/implementation-of-the-marriage-and-civil-partnership-minimum-age-act-2022 (accessed on 13 March 2023).

[12] Government of the United Kingdom (2021), Domestic Abuse Act 2021, https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2021/17/section/1/enacted (accessed on 13 March 2023).

[13] Government of the United Kingdom (2003), Sexual Offences Act 2003, https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2003/42/contents (accessed on 13 March 2023).

[26] Government of the United States (n.d.), United States Code, https://uscode.house.gov/ (accessed on 13 March 2023).

[20] GREVIO (2022), Baseline Evaluation Report: Iceland, https://rm.coe.int/grevio-inf-2022-26-eng-final-report-on-iceland/1680a8efae (accessed on 13 March 2023).

[18] GREVIO (2018), Baseline Evaluation Report: Sweden, https://rm.coe.int/grevio-inf-2018-15-eng-final/168091e686 (accessed on 13 March 2023).

[15] International Criminal Court (2011), Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, https://www.icc-cpi.int/sites/default/files/RS-Eng.pdf.

[10] MESECVI (2020), Informe de Implementación de las Recomendaciones del Comité de Expertas Del MESECVI, https://belemdopara.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/FinalReport2019-Mexico.pdf.

[1] OECD (2023), About the SIGI, https://www.genderindex.org/sigi/ (accessed on 12 February 2020).

[14] OECD (2021), Man Enough? Measuring Masculine Norms to Promote Women’s Empowerment, Social Institutions and Gender Index, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/6ffd1936-en.

[6] OECD (2019), SIGI 2019 Global Report: Transforming Challenges into Opportunities, Social Institutions and Gender Index, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/bc56d212-en.

[42] OECD (2017), 2013 OECD Recommendation of the Council on Gender Equality in Education, Employment and Entrepreneurship, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264279391-en.

[16] OECD Development Centre (2022), SIGI Gender-based Violence Legal Survey, OECD, Paris.

[7] OECD Development Centre/OECD (2023), “Gender, Institutions and Development (Edition 2023)”, OECD International Development Statistics (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/7b0af638-en (accessed on 17 April 2023).

[21] OHCHR (2021), Harmonization of criminal laws needed to stop rape – UN expert, Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights.

[19] The Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention (2020), The new consent law in practice, https://bra.se/download/18.7d27ebd916ea64de53065cff/1614334312744/2020_6_The_new_consent_law_in_practice.pdf.

[22] UNESCO (n.d.), School-related gender-based violence.

[31] UNFPA (2020), En Colombia, esfuerzos para poner fin a la mutilación genital femenina están empoderando a las mujeres para ser líderes, https://colombia.unfpa.org/es/news/esfuerzos-para-poner-fin-a-la-mutilacion-genital-femenina (accessed on 13 March 2023).

[32] UNICEF (2022), Child Marriage, https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-protection/child-marriage/ (accessed on 13 March 2023).

[35] UNICEF (1989), Convention on the Rights of the Child, https://www.unicef.org/child-rights-convention/convention-text (accessed on 13 March 2023).

[2] United Nations (2017), General recommendation No. 35 on gender-based violence against women, updating general recommendation No. 19 (1992), CEDAW/C/GC/35, Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, https://www.ohchr.org/en/documents/general-comments-and-recommendations/general-recommendation-no-35-2017-gender-based (accessed on 13 February 2020).

[5] United Nations (2016), Sustainable Development Goal 5, Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform, https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdg5 (accessed on 15 November 2019).

[37] United Nations (2015), The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 13 March 2023).

[3] United Nations (1992), General recommendation No. 19: Violence against women, https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/Treaties/CEDAW/Shared%20Documents/1_Global/INT_CEDAW_GEC_3731_E.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2020).

[4] United Nations (1979), Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), https://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6b3970.html (accessed on 11 June 2020).

[34] United Nations (1962), Convention on Consent to Marriage, Minimum Age for Marriage and Registration of Marriages, https://treaties.un.org/doc/treaties/1964/12/19641223%2002-15%20am/ch_xvi_3p.pdf.

[27] WHO (2022), Fact sheet: Female genital mutilation, World Health Organization, Geneva, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/female-genital-mutilation.

[28] Wulfes, N. et al. (2022), “Cognitive–Emotional Aspects of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in the Context of Female Genital Mutilation”, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, Vol. 19/9, p. 4993, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19094993.

Notes

← 1. CEDAW has not been ratified by Iran, Palau, Somalia, Sudan, the Holy See, the United States and Tonga.

← 2. According to the SIGI, informal laws are defined as customary, traditional or religious laws that create different rights or abilities between men and women.

← 3. Chile, Costa Rica, France, Greece, Ireland, Mexico, Slovenia, Spain, Switzerland and Türkiye.

← 4. The Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence against Women and Domestic Violence – better known as the Istanbul Convention - is a European legal instrument that was adopted in 2011. The Convention was negotiated by Council of Europe’s 47 member states. To date, 34 member states of the Council of Europe have ratified the convention.

← 5. The Rome Statute reproduced herein was originally circulated as document A/CONF.183/9 of 17 July 1998.

← 6. Australia, Belgium, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Denmark, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, New Zealand, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, United Kingdom and the United States.

← 7. The 2013 OECD Recommendation of The Council on Gender Equality in Education, Employment and Entrepreneurship calls for promoting measures to end sexual harassment in the workplace such as prevention campaigns and actions by employers and unions (OECD, 2017[42]).

← 8. Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT), the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (ECHR) and the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (2010/C 83/02).

← 9. Australia, Belgium, Canada, Colombia, Finland, France, Ireland, Italy, Norway, Spain, Sweden and Switzerland.