Organising Committees are ultimately responsible for the delivery of a complex web of individual projects ranging from sports-related infrastructure to associated services such as hospitality or transport. Bringing all these pieces together to form a successful, coherent Games’ experience comes with specific challenges: interlinked procurement strategies, lack of market capacity to support delivery or complex relationships with suppliers. This chapter provides insights, good practice and concrete tools to help Organising Committees delivering a full programme of projects and services.

Guidelines on the Effective Delivery of Infrastructure and Associated Services for the Olympic Games

5. Programme management

Abstract

5.1. What are the risks?

OCOGs operate in a challenging delivery environment. Along with risks related to the delivery of specific elements of the Games, OCOGs face challenges related to the management of the integrated delivery of the full programme of projects and services. OCOGs play a diversity of roles in the delivery of infrastructure and associated services: depending on the institutional arrangements as well as the infrastructure and services being procured, the OCOG may be directly conducting procurements, or setting specifications and standards and overseeing procedures by other actors. In both cases, the OCOG is responsible for ensuring the coordinated delivery of infrastructure and associated services. OCOGs are ultimately responsible for the successful delivery of a suite of venues and services, an inherently more complex task than delivering a single sports event or a single venue.

Choosing the wrong procurement strategy or failing to adequately manage delivery risks can lead to cost overruns, delays, and quality issues. The first stages of the procurement cycle – including delivery model choice and assessment of market capabilities – are of key importance, and shortcomings in these early phases may set the stage for later challenges, as they tend to be overlooked in the infrastructure procurement of sporting mega-events (OECD-IPACS, 2019[1]).

As explained in Section 1, the new delivery model seeks to provide a more efficient and cost-effective approach to event delivery. Supported by the enhanced flexibility in delivery that is a critical component of the IOC’s ‘New Norm’, the new delivery model seeks to leverage the event organisation industry’s ability to supply readymade solutions, reducing the scope and complexity for OCOGs and promoting efficiency.

This section examines those challenges in the context of the procurement and delivery of Games infrastructure and associated services, with a focus on four areas of risk:

Choice of delivery mode (i.e. the way in which the infrastructure asset or service will be procured and financed);

Market capacity and readiness;

Contract and supplier management; and,

The fast-paced environment and tight time constraints of the Games.

5.1.1. Choosing the wrong delivery mode can negatively impact value for money

Selecting the delivery mode which provides the optimal value for money is critical to successful delivery. Factors such as the capabilities of the OCOG and its potential partners, the characteristics of the project or service, and the desired allocation of risks and controls (OECD, 2021[2]) should all be considered when deciding whether to bundle different components of event delivery in a single contract, as well the bidding procedures and payment mechanisms. When these key factors differ significantly between events, projects or services, imposing a single delivery mode risks costs overruns and delays. For example, a turnkey solution with payment terms that transfer significant risks to the supplier may be appropriate where there is a robust market of sophisticated suppliers, the event scope and outputs can be fully specified, and there are limited risks related to integration with the overall Games programme. However, if outputs cannot be well specified ex-ante and risks cannot be defined and measured, it may be more appropriate to implement a more traditional approach, where the OCOG would take on a project management role and be responsible for integrating multiple suppliers.

Box 5.1. Joint management for dual purpose: the 2015 Pan Am Games Athletes’ Village

The Athletes’ Village for the Pan American and ParaPan American Games in Toronto had two objectives. First, it was to provide temporary residences for the athletes, staff and coaches involved in the Pan Am Games. Second, it was to serve the needs of future residents with a mixture of affordable housing and community spaces. As the facilities would have mixed purpose and multiple stake holders, the design, construction and management of the Athletes’ Village were overseen by different partners at different times. The joint management of the facilities, between Infrastructure Ontario (a provincial government agency) and Toronto 2015 (the organising committee for the Games), allowed it to both serve the needs of the international sporting event and residents.

In the construction phase, the project used a design-build-finance delivery mode. Infrastructure Ontario, the owner, worked with several private partners to deliver the facilities. For the purposes of the Pan Am Games, temporary infrastructure was designed and constructed under the supervision of Toronto 2015.

During the period of the Pan Am Games (the 'Operational Period') private partners remained involved. They were responsible for building management and maintenance, along with maintenance of the roads and grounds within the site. Following the end of the Operational Period, the facilities were turned over to Infrastructure Ontario, which repurposed the Village to serve the long-term residential population. This included the creation of a community centre and sports facility, a student housing complex and 253 affordable rental units. The decision to use the site for the Village expedited the area’s redevelopment by five to 10 years.

Delivery mode choice that is not grounded in an analysis of risk and uncertainty can reduce the pool of potential bidders and allocate risk inefficiently, undermining value for money. The number of parties involved in Games planning and delivery creates risk allocation challenges by making it more difficult to map the distribution of responsibilities and decision making across all of those involved. For OCOGs, risk allocation can be a particular challenge where responsibility for delivery and funding of non-sport infrastructure or services, such as transportation or security, is unclear or sits with other stakeholders.

In the case of London 2012, the OCOG was responsible for venue security operations, while the government was responsible for setting security requirements and overseeing security arrangements. By 2010, however, the government and the OCOG had not fully agreed on the responsibilities or budget for venue security: costs eventually reached over GBP 500 million from an initial GBP 29 million budget and the military and police were forced to provide thousands of additional personnel after the OCOG’s contractor was unable to fulfil its obligations (House of Commons Committee of Public Accounts, 2013[5]). While a settlement was reached with the contractor to reduce payments, the OCOG was unable to transfer the full delivery risk, and ultimately bore a significant reputational cost for the high-profile failure.

Box 5.2. Considerations to guide delivery mode choice

Delivery mode choice requires an understanding of strategic outcomes and their relationships to the full Olympic programme, an analysis of the market and the relevant delivery risks, and a consideration of a full range of potentially suitable options.

The following questions can support OCOGs’ in their decisions about the delivery mode for different events:

|

Event Scope and Characteristics |

Capacity and Capabilities |

Risk Management and Transfer |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Source: Adapted from (OECD, 2017[6]; OECD, 2022[7]; Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development, 2008[8]))

Box 5.3. Centralising risk for the construction of Heathrow T5

In the early 2000s, the construction of Heathrow Airport Terminal 5 (T5) was the largest construction project in Europe. The British Airports Authority (BAA), a major airport operator that was privatised in 1986, realised that if the projects were to be built on time and within budget, a unique approach would be required.

The foundation of the BAA’s project management strategy was the T5 Agreement, a relational contract between the BAA and all the T5 first-tier suppliers. The Agreement was structured differently from traditional construction contracts. It aimed to create incentives for positive problem-solving behaviours in order to minimise the conflicts that had previously plagued major projects.

The BAA took a different and unique approach to risk in the T5 project: it held all the risk. As such, incentives were required to encourage all other partners involved in the project to minimise risk. This was achieved through financial incentives for suppliers, rewarding successful performance. GBP 100 million was taken from individual projects and put into a central pot. This allowed the risk contingency to be allocated based on need. This allowed for greater control over the financial implications of risk at a more global level and thus tighter overall budget control.

Source: (OECD, 2015[9])

5.1.2. Limited market readiness and capacity can result in high costs

The new delivery model emphasizes the need for a strong market of potential suppliers: outsourcing delivery to entities that have existing capacity and experience can reduce costs and delivery risks, but may reduce competition. For example, there may only be one existing venue that is appropriate for the Games, leading to its owner or operator having an advantageous position. Without appropriate mitigation processes in place, this has the potential to create significant risk. The OECD Recommendation on the Governance of Infrastructure advises engaging in transparent and regular dialogues with suppliers and business associations to present procurement strategies (including planning, scope, identified delivery mode, procurement method, requirements and award criteria) and to assure an accurate understanding of market capacity, while addressing possible risks of collusive practices.

A strong network of experienced and reliable suppliers is key to an efficient procurement strategy and the successful delivery of Games infrastructure and associated services. OCOGs will face significant challenges if this delivery environment, and the associated relationships, are not in place early in the Games delivery process. For example, London 2012’s heavy use of temporary venues led to challenges sourcing enough suppliers of items such as seating, toilets and other temporary infrastructure, which made up 30% of the OCOG’s procurement budget (London Organising Committee of the Olympic Games and Paralympic Games, 2013[10]). Whereas a typical organisation can rely on supplier capability and capacity building and continual improvement to achieve its objectives, an OCOG does not have the time or repeated market engagements required for such an approach. Much of an OCOG’s leverage is likely to be at the start of its engagement with suppliers and partners, with little or no leverage in the final stages of the Games when infrastructure and services have been delivered and the OCOG is close to dissolution (International Olympic Committee, 2019[11]).

5.1.3. Contract management strategies need to be tailored to the characteristics of elements of the programme

Although inherently unique, individual projects included in the overall programme present one common trait because of their size and complexity: by far, the longest phase of the procurement cycle is contract execution. However, while pre-tendering activities and the tendering stage concentrate the attention of stakeholders, further efforts could be devoted to contract execution so objectives defined during early development phases translate into tangible achievements.

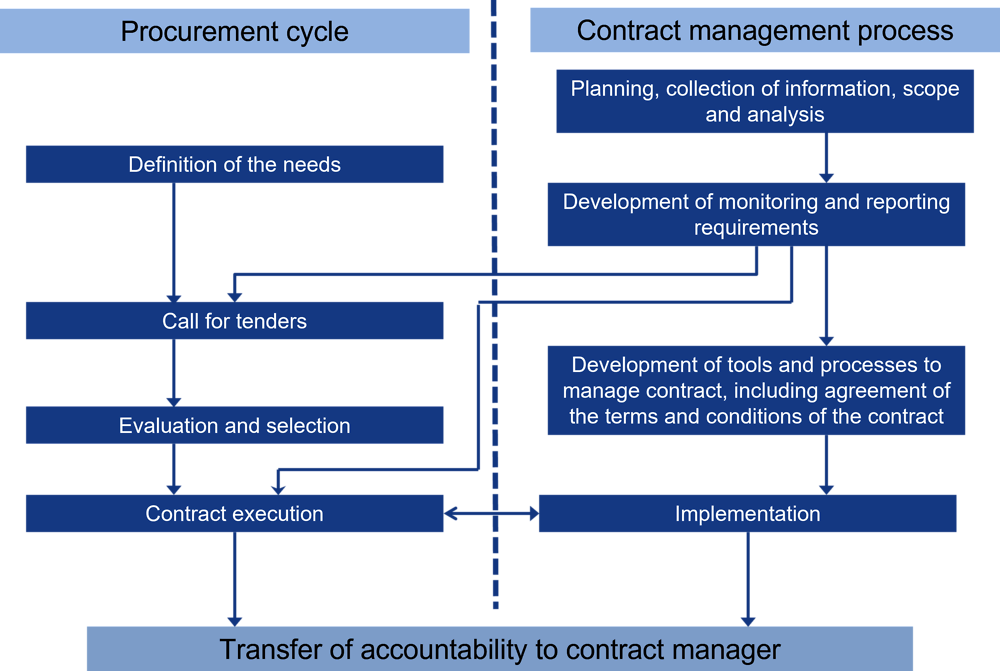

Further, limited resources available in OCOGs to manage the multitude of contracts composing the overall programme require a strategic approach to contract management, acknowledging that contractors have varying influence on the effective delivery of the Games. Contract management objectives and supplier relationship strategies need to be enshrined into projects and defined well before works or services are put to tender. As shown in the figure below, strategic contract management requires to define mechanisms and reporting requirements which would be integrated in tender documents and will form the basis on which suppliers will also be assessed based on their capabilities to adhere to reporting requirements.

Figure 5.1. Development of contract management strategies

Being one of the most labour-intensive activities, construction works have a direct impact on the supply base, especially for projects of large magnitude. This holds particularly true in countries where markets in the construction industry are concentrated. The impact on the supply base is further emphasized by the relative low share of cross-border procurement in OECD countries and, sometimes, local content provisions.

Those elements directly influence contract management strategies since they provide for a higher probability of suppliers holding multiple contracts in the overall programme. This calls for a transition from individual contract management to supplier relationship management. Analysing OCOGs’ portfolio of suppliers could provide insights to better rationalise the allocation of internal resources dedicated to contract management and to ensure that supplier relationship management strategies are the most effective in supporting the delivery of the programme. Indeed, suppliers’ relative importance to OCOGs in terms of risks and business value warrants for tailored contract management strategies.

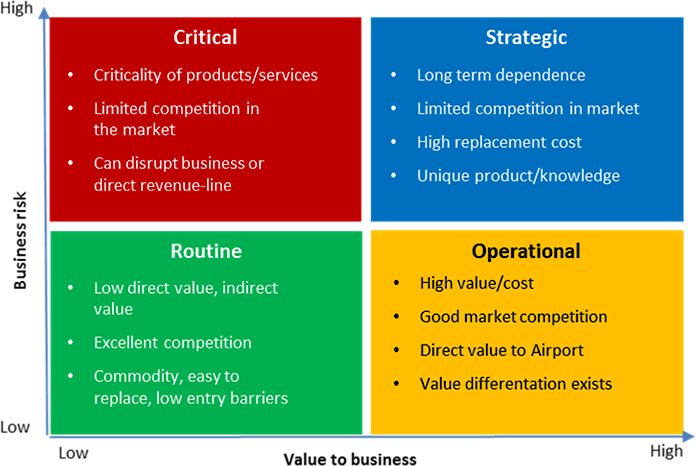

This effort should first build on a structured segmentation of the supply base according to criteria based on OCOG’s values and objectives. This exercise can be supported by longstanding literature on supplier segmentation helping to allocate suppliers in the following categories.

Figure 5.2. Supply base segmentation

Last, procurement for Olympic programmes often imply long and sometimes interconnected supply chains. Further, considering the high degree of specialisation of some works, specific subcontractors might provide critical inputs to the overall programme. It is therefore necessary to define contract management and supplier relationship strategies that go beyond first-tier contractors and provide OCOGs with a clear visibility on supply chains composition. This enhanced understanding of relationships between OCOGs, first-tier suppliers and subcontractors would provide critical insights to effectively manage risks posed to the execution of the whole programme as well as supply chains risks such as possible violation of human rights.

By tailoring supply contracts based on values and objectives OCOGs can ensure that contracts are efficient and well defined. This means defining contracts based on the specific interaction with suppliers and would simultaneously mitigate risks relating to insufficient financial and human resources allocated to contract management. For example, referring to figure 5.2, suppliers categorised as routine might only be subject to contractual oversight with operational involvement whereas critical or strategic suppliers would be subject to greater involvement of senior management on both ends with the view to improve performance beyond contractual obligations.

5.1.4. Fast-paced environments and tight time constraints create a challenging delivery environment

Delivery for major events like the Games is complex, and a strategy and procedures must be in place in order to deliver on time, on budget, and according to specifications. If not prepared from an early stage, a weak cost plan or unfinished project scope and requirements can create unnecessary contract and financial management difficulties, as well as variations post-contract award that can significantly raise project costs (International Olympic Committee, 2020[14]). The immovable deadline of the Games poses significant challenges: with no room for delay, there is a heightened risk of cost overruns to ensure infrastructure is delivered in time and that services meet requirements.

Failure to adequately oversee and evaluate infrastructure delivery and performance can have a negative impact on value for money throughout the infrastructure life cycle. Immovable deadlines incentivises a focus on the swift delivery of assets and less on their quality and life cycle performance or on controlling costs. If long-term operators are not involved in the procurement and delivery process, risks around life cycle performance and long-term financial viability can be significantly exacerbated.

Box 5.4. Coordinating temporary overlays at Tokyo 2020

Temporary overlays for Tokyo 2020 included not only simple structures such as tents, prefabricated buildings, and seats, but also buildings with heavy steel frames, light towers, and extensive utility work. Temporary overlays were constructed in all 85 venues, including existing, new and temporary competition venues, across ten prefectures. A large number of parties were involved in the construction of the overlays, including different areas of the OCOG, the IOC, sports associations, venue owners and administrators, and local municipal entities.

To manage this challenging set of projects and help manage costs, the OCOG put in place a number of strategies:

Use of design-build contracts (including demolition, removal, and restoration) to reduce the number of involved parties and associated change orders. However, separate procurements were conducted where the scale and characteristics were particularly challenging for the market, for example temporary seating.

Where possible, overlays for multiple venues were procured together as a cluster to facilitate construction schedule control and achieve economies of scale.

The OCOG set standard specifications for elements that would be commonly procured, such as tents and security fences.

The implementation of coordination mechanisms such as an Overlay Book, which compiled the plans for all venues and was updated every six months, and a Venue Integration Group, which managed the progress of planning and construction and maintained a consolidated construction schedule.

An overly strong focus on financial criteria during the pre-tender and tender phases can encourage the selection of proponents that submit low proposals, instead of suppliers that have valuable experience in the delivery of sport infrastructure and related services (International Olympic Committee, 2020[14]). Low-balling strategies can also lead to subsequent post-contract-award negotiations and significant cost increases during implementation.

5.2. Experiences from Paris, Milano-Cortina and Los Angeles

Box 5.5. Paris 2024 is leveraging external expertise to deliver a more efficient Games

Paris 2024 is pioneering the use of the new event delivery model for the 2024 Games. From infrastructure to services, the model aims to leverage existing experience as much as possible in the delivery of the Games. This model has two objectives: excellence in delivery, capitalising on existing expertise while limiting the OCOG’s operational costs and creating sustainable opportunities for the sports and events sector.

The OCOG is overseeing delivery while engaging external providers for support, helping the Games benefit from a greater range of innovation and efficiency. An event platform was established where interested stakeholders could view opportunities and needs related to the Games organisation. This provides transparency for bidders and a way for Paris 2024 to assess the most optimal delivery option.

Three venues, Yves du Manoir in Colombes for field hockey, Golf National in Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines, and the Paris La Défense Arena for swimming races, were chosen to pilot the delivery model with external stakeholders and providers. Through these pilots, the OCOG decided on two approaches to delivery: a delivery model based on the involvement of several delivery entities overseen by Paris 2024, and a delivery model handled in-house by Paris 2024 for complex events where there is limited expertise available on the market.

Source: Information provided by Paris 2024

Box 5.6. Implementing the new event delivery model for Milano-Cortina 2026

Milano-Cortina 2026 aims host the Olympic and Paralympic Games in a fiscally responsible, socially sustainable, and environmentally friendly manner. A key goal of the OCOG is to maximize the use of local expertise and capabilities by involving Event Delivery Entities (EDEs). EDEs are organisations with existing experience and expertise contracted to deliver venues and sport operations for selected disciplines. Partnering with EDEs that have previously organised world-class events will allow the OCOG to leverage their specific knowledge. EDEs will be selected based primarily on their previous experience in organising specific Games events. For example, the OCOG will partner with an existing South Tyrol-based company which successfully organised the 2019 Biathlon World Cup to deliver biathlon at the Games.

Each Games venue or zone will be planned and delivered differently depending on the most efficient solution for the specific context. The events will be delivered by the OCOG, EDEs or a combination of both. Where an EDE is not in place (e.g. in Milan), the OGOC will manage event delivery in-house, while still leveraging the expertise of venue owners and operators through extended venue use agreements. This event-centric organisation model will rely on a local management structure with an Event Director who has responsibility for the venue and event.

The strategy is underpinned by the following considerations:

Establish an event-driven planning process to enhance the effectiveness of venue design and development, particularly with respect to sustainability, legacy, operational excellence, and cost-efficiency.

Accelerate knowledge-sharing procedures to shorten the preparation time and Games delivery, thus reducing the overall resource requirement and the size of the workforce.

Reduce the cost and complexity of each venue and event where possible.

Explore the most efficient way to deliver each sport/discipline, outsourcing the delivery to selected EDEs to leverage their expertise where appropriate.

Increase the knowledge and capabilities of EDE staff regarding best practices in sustainable event management, that can be applied to future events organised by the EDEs after the Games.

Source: Information provided by Milano-Cortina Foundation

5.3. Addressing programme management risks

5.3.1. Key principles

Box 5.7. Key principles for mitigating programme management risks

1. Use robust, evidence-based analysis to guide delivery mode decisions

OCOGs should work carefully to evaluate available delivery modes against well-defined criteria rather than applying one-size-fits-all solutions. Delivery options should be assessed based on projects’ characteristics, local context, optimal risk allocation and value for money evaluations.

The questions in Box 5.2 provide a guide for the development of criteria by OCOGs.

2. Take measures to ensure market readiness and capacity

OCOGs should work with delivery partners to ensure that the supplier market is able to meet the requirements of the Games. This can include engaging in transparent and regular dialogues with suppliers and business associations to present procurement strategies (including details such as scope, identified delivery mode, procurement method, requirements and award criteria) and to develop an accurate understanding of market capacity.

3. Take a strategic approach to supplier management

OCOGs should define contract management objectives and supplier relationship strategies during the planning phase, before contracts are put to tender. Coordination mechanisms and reporting requirements should be integrated into tender documents. A supplier relationship management approach can be effective in supporting the delivery of the full Games programme. Identifying the relative importance of suppliers to the overall delivery of the Games, including subcontractors, can help to manage risks.

4. Implement a risk-based approach to manage the short timelines inherent to Games delivery

A focus on risk identification, assessment, mitigation and monitoring throughout planning and delivery can help to prevent cost overruns and delays. By integrating risk management in their delivery processes and implementing appropriate risk management tools, OCOGs can mitigate the challenges posed by the immovable deadline of the Games.

5.3.2. Checklist

Table 5.1. Programme management checklist

|

Task |

Status (Yes/No) |

|---|---|

|

Make evidence-informed decisions about delivery modes to maximize value for money |

|

|

Are there clear criteria for evaluating available delivery modes? Criteria should be based on projects’ characteristics, the optimal risk allocation and the use of value for money analytical tools. |

|

|

Does the project have a transparent and appropriate allocation of risks throughout the full life cycle? |

|

|

Have the different delivery models been stress tested by checking their sensitivity to circumstances when certain risks materialise? |

|

|

Score: /3 |

|

|

Ensure market readiness and capacity |

|

|

Has a comprehensive analysis and evaluation been undertaken to ensure a strong understanding of the structure of the market? |

|

|

Is there a plan to engage with suppliers and business associations to present procurement strategies? This could include details on planning, scope, identified delivery mode, procurement method, requirements and award criteria. |

|

|

Score: /3 |

|

|

Take a strategic approach to supplier management |

|

|

Has an overall contract and supplier management strategy been developed before going to tender? Has the strategy been incorporated into the development of tender documents? |

|

|

Have you undertaken an analysis of the OCOGs’ supplier portfolio, including evaluating the relative importance of suppliers to OCOGs from a risk perspective? |

|

|

Have you implemented mechanisms and processes to go beyond first-tier contractors and develop visibility on the full supply chain? |

|

|

Score: /3 |

|

|

Implement a risk-based approach to manage the short timelines inherent to Games delivery |

|

|

Has risk management been incorporated into all stages of the delivery of infrastructure and associated services? |

|

|

Are there standardised tools to identify, assess and monitor risks and bring them to the attention of relevant personnel? |

|

|

Have procurement activities and tracking been integrated into the OCOG’s overall financial management and budgeting processes? |

|

|

Score: /3 |

|

|

Total Score: /12 |

|

5.3.3. External resources

OCOGs can take advantage of a range of existing policies, tools and good practices from the world of sport and from broader infrastructure governance practice to develop the methods for programme management. These resources provide opportunities for OCOGs to assess their current practices and approaches, inform the development of their own strategies and policies, and serve as examples of good practice.

Most of these external tools do not pertain directly to sport, however, could be useful to organisers of large-scale international sporting events as they detail relevant public procurement roles and functions. The STEPS tool outlined in Table 5.2, for example, allows organisers to identify the best procurement method and approach for their specific project. Other tools provide specific advice on how to manage a project that is under tight time and constraints while adequately addressing risks.

Table 5.2. External resources for programme management

|

Tool |

Description |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Tools and guidance to support procurement strategy: these tools provide advice and concrete support in the development of procurement strategies, including decisions around delivery mode and evaluating market capacity. |

||

|

Support Tool for Effective Procurement Strategies (STEPS) |

The STEPS tool bridges a major capability gap for public and private sector procurement of infrastructure and other bespoke projects. STEPS approaches the development of procurement strategies in an evidence-based way, helping project owners identify and manage potential procurement failures. A comprehensive procurement strategy developed using STEPS helps to define, among others, the capabilities required in-house, contract scoping, and commercial terms. More broadly, STEPS sheds light on the options and trade-offs project owners face in achieving their objectives. |

https://www.oecd.org/gov/infrastructure-governance/STEPS-brochure-april-22.pdf |

|

Reference Guide on Output Specifications for Quality Infrastructure |

This reference guide is designed to assist in the development of output specifications (i.e. a technical specification that predominantly adopts performance-based requirements to define the project scope) to deliver quality infrastructure. Focused on PPPs, it includes sector case studies and output specification examples across a range of jurisdictions and sectors. |

https://cdn.gihub.org/umbraco/media/2761/gih_output_specs_art_web.pdf |

|

OECD Infrastructure Toolkit: Procurement Strategies |

Procurement is an essential part of the infrastructure life cycle, it is thus important that it is done in an efficient and transparent manner to ensure infrastructure objectives are achieved. The OECD Infrastructure Toolkit is an online resource to guide the planning, financing and delivery of infrastructure. |

https://infrastructure-toolkit.oecd.org/governance/procurement/ |

|

Tools and guidance to support programme management: these tools provide strategies and templates to support the delivery of Games infrastructure and associated services in fast-paced environments and under tight time constraints. |

||

|

Rapid mobilisation playbook |

The New Zealand rapid mobilisation playbook is designed to help construction or infrastructure projects get started faster. It includes tools such as checklists and templates to support tasks including risk allocation and project team and governance selection. |

https://www.procurement.govt.nz/assets/procurement-property/documents/rapid-mobilisation-playbook.pdf |

|

Project and programme management |

The United Kingdom's Infrastructure and Projects Authority (IPA) supports the successful delivery of infrastructure and large-scale projects. |

https://www.gov.uk/guidance/project-and-programme-management |

|

Tasmania’s (Australia) checklist of potential risks in the goods and services procurement process |

The Tasmanian Government (Australia) developed a checklist of potential risks in the procurement cycle that is composed of 11 parts. |

https://www.purchasing.tas.gov.au/Documents/Checklist-of-Potential-Risks---goods-and-services-procurement-process.doc |

References

[8] Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development (2008), National Public Private Partnership Guidelines (Volume 1: Procurement Options Analysis), https://www.infrastructure.gov.au/sites/default/files/migrated/infrastructure/ngpd/files/Volume-1-Procurement-Options-Analysis-Dec-2008-FA.pdf.

[3] Global Infrastructure Hub (n.d.), Case Study: Pan Am Games Athletes’ Village, https://cdn.gihub.org/umbraco/media/2751/case-study-pan-am-games-athletes-village.pdf.

[5] House of Commons Committee of Public Accounts (2013), The London 2012 Olympic Games and Paralympic Games: post-Games review, https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201213/cmselect/cmpubacc/812/812.pdf.

[14] International Olympic Committee (2020), Procurement of Major International Sport-Events-Related Infrastructure and Services: Good practices and guidelines for the Olympic movement, https://stillmed.olympic.org/media/Document%20Library/OlympicOrg/IOC/What-We-Do/Leading-the-Olympic-Movement/ipacs/Procurement-Guidelines-EN-v4.pdf#_ga=2.110570885.1600316014.1590398634-406123057.1536651541.

[11] International Olympic Committee (2019), Olympic Games Guide on Sustainable Sourcing, https://stillmed.olympics.com/media/Document%20Library/OlympicOrg/IOC/What-We-Do/celebrate-olympic-games/Sustainability/Olympic-Games-Guide-on-Sustainable-Sourcing-2019.pdf.

[10] London Organising Committee of the Olympic Games and Paralympic Games (2013), London 2012 Olympic Games Official Report Volume 3.

[7] OECD (2022), The Support Tool for Effective Procurement Strategies (STEPS): Informing the Procurement Strategy of Large Infrastructure and Other Bespoke Products, https://www.oecd.org/gov/infrastructure-governance/STEPS-brochure-april-22.pdf.

[2] OECD (2021), OECD Implementation Handbook for Quality Infrastructure Investment: Supporting a Sustainable Recovery from the COVID-19 Crisis, https://www.oecd.org/finance/OECD-Implementation-Handbook-for-Quality-Infrastructure-Investment-EN.pdf.

[12] OECD (2018), Second Public Procurement Review of the Mexican Institute of Social Security (IMSS): Reshaping Strategies for Better Healthcare, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264190191-en.

[6] OECD (2017), Getting Infrastructure Right: A framework for better governance, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264272453-en.

[9] OECD (2015), Effective Delivery of Large Infrastructure Projects: The Case of the New International Airport of Mexico City, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264248335-en.

[1] OECD-IPACS (2019), Mitigating Corruption Risks in the Procurement of Sporting Events, https://www.oecd.org/gov/public-procurement/mitigating-corruption-risks-procurement-sporting-events-IPACS.pdf.

[4] Office of the Auditor General of Ontario (2016), Special Report: 2015 Pan Am/Parapan Am Games, www.auditor.on.ca/en/content/specialreports/specialreports/2015panam_june2016_en.pdf.

[13] Runar Stalsberg (2018), Contract Management in Avinor.

[15] Tokyo Organising Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games (2022), Tokyo 202 Official Report (Volume 1), https://library.olympics.com/Default/doc/SYRACUSE/2954165/tokyo-2020-official-report-the-tokyo-organising-committee-of-the-olympic-and-paralympic-games#.