This chapter illustrates the increasing shareholder engagement focused on environmental issues in Asia. This engagement tends to take the form of direct dialogue with company management via a shareholders’ meeting or, sometimes, through court action. The chapter also provides an overview of the commitments made by Asian jurisdictions to achieve carbon neutrality and/or net-zero GHG emissions, and the number of companies disclosing information on GHG emissions in the region.

Sustainability Policies and Practices for Corporate Governance in Asia

4. Shareholders

Abstract

In Asia, a significant number of jurisdictions have made commitments to achieve carbon neutrality and/or net-zero GHG emissions, aligning with both the Paris Agreement on Climate Change and the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. With the increasing adoption of these commitments, regulators, and societies in general, have started taking actions in that direction. The transformation of the global economy towards a more sustainable model requires the corporate sector to implement significant changes. Therefore, shareholders and regulators are increasingly calling for enhanced engagement with companies on sustainability-related issues. There is a global recognition that shareholder engagement at the company level is crucial to achieve concrete actions to address sustainability-related issues, in particular climate change. The increasing number of environmental shareholder resolutions is evidence of such shareholder engagement activities. Often, these initiatives are the result of joint actions by domestic and foreign investors. Collaboration between domestic and foreign investors can be an effective strategy to demonstrate to companies that domestic and global agendas are aligned. Disclosure is key for shareholders to efficiently engage with companies and to influence and support the necessary business transformation of companies. In particular, disclosure on GHG emissions and reduction targets could hold companies accountable to shareholders and stakeholders on their actions and progress towards addressing climate‑related issues. While there are differences between jurisdictions, Asian companies are generally lagging behind large parts of the world, such as Europe and the United States, with respect to disclosure of GHG emissions and reduction targets.

4.1. Shareholder engagement

There are a variety of ways that shareholders can engage with corporations to influence their decisions. The most common forms of engagements are direct dialogue with company management via a shareholder meeting, or through court action (OECD, 2022[1]). The G20/OECD Principles provide recommendations on the rights and equitable treatment of shareholders and highlight that “[s]hareholders’ rights to influence the corporation centre on certain fundamental issues, such as the election of board members, or other means of influencing the composition of the board, amendments to the company’s organic documents, approval of extraordinary transactions, and other basic issues as specified in company law and internal company statutes”. The G20/OECD Principles also stress the rights of shareholders in terms of sustainability‑related matters by recommending that corporate governance frameworks should “[a]llow for dialogue between a company, its shareholders and stakeholders to exchange views on sustainability matters as relevant for the company’s business strategy and its assessment of what matters ought to be considered material” (OECD, 2023[2]).

Globally, evidence shows climate change is clearly a priority for shareholders in their engagement with companies (see also sections 4.1.1 and 4.1.2). There are many examples of investors around the world calling for companies to do more on sustainability, with engagement on climate change increasing in recent years. For example, management-supported resolutions that seek shareholders’ approval of a company’s climate transition plan or actions (“say-on-climate” votes) are emerging. As of 1 February 2022, 33 companies in the MSCI ESG Ratings coverage had held, or planned to hold, such a vote (MSCI, 2022[3]). In addition, in 2023, over 700 capital market entities were signatories to the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP), which was established in 2000 and encourages companies to disclose their climate impact (CDP, 2023[4]). More broadly, in a 2021 survey of citizens covering 17 advanced economies across Asia‑Pacific, Europe and North America, 80% of respondents indicated that they would be willing to make some changes in the way they work and live to mitigate the impacts of climate change (Pew Research Centre, 2021[5]).

The number of Asian companies and jurisdictions with net‑zero commitments is also increasing (Climate Action 100+, 2022[6])). However, Asian jurisdictions still generally lag behind when it comes to disclosure of GHG emissions. At the end of 2021, companies representing 72% of the world’s total market capitalisation and 12.5% of the number of listed companies publicly disclosed information on their scope 1 and 2 GHG emissions, significantly higher than the number in Asia, where 7.6% of listed companies representing 53% of total market capitalisation disclose the same information. In addition, companies representing almost two-thirds of the global market capitalisation disclose their GHG emissions reduction targets, compared to around one‑third of companies by market capitalisation in Asia (see section 4.2 for further details).

Therefore, an important factor going forward in the transition to net‑zero will be whether the increase in shareholder engagement on sustainability issues in recent years, both globally and in Asia, continues. Direct shareholder engagement with company management has been an important mechanism to drive climate‑positive change by companies. There are many ways that shareholders and management can engage in direct dialogue, including on sustainability‑related issues, ranging from confidential correspondence and meetings to public letters (OECD, 2023[7]). Shareholders may engage individually, or they may coordinate their efforts with other shareholders and stakeholders. In this respect, evidence shows that the assets under management invested in funds that employ shareholder power to influence corporate behaviour are estimated to be about 30% (USD 10.5 trillion) of the USD 35.9 trillion reported total sustainable investing amount in 2020 (GSIA, 2020[8]). Another example of collaboration is the establishment of investor networks, including those that operate in Asia, which have regionally focused working groups to ensure that engagement is effective in specific markets.

4.1.1. Engagement related to shareholder meetings

There are a range of actions that can be taken in shareholders’ meetings, including resolutions requiring a change in corporate policy, changing the composition of the board or even altering a company’s articles of association. Globally, there were 146 environmental shareholder resolutions voted on in 2022, representing a 22% increase compared to 2021. Around 55% of these proposals mentioned climate-related policies, strategies, targets and/or reporting (Insightia, 2022[9]). There are also indications of an increase in the number of such resolutions in Asia (ClientEarth, 2022[10]; Insightia, 2023[11]).

Shareholder resolutions are effective in influencing companies, even if they do not receive the required level of support for the resolution to be passed, or even if the vote is non-binding on the board. For example, globally, BlackRock’s 2021 Global Principles and Market-level Voting Guidelines indicate that for shareholder resolutions that received 30-50% support, companies then fully or partially implemented the substance of the proposal for 67% of the resolutions. Where shareholder resolutions received more than 50% support, companies later fully implemented the proposal for 94% of the resolutions. BlackRock has also reported that where they consider that companies need to act with greater urgency on climate-related issues, their “most frequent course of action will be to hold directors accountable by voting against their re-election” (BlackRock, 2020[12]).

Shareholder resolutions related to climate are becoming more common in Asia. For example, the first climate‑related shareholder resolution for a Japanese company was filed in 2020 and such resolutions have been on the rise in recent years (3 in 2021 and 12 in 2022), where the proponents were environmental organisations, international institutional investors and local governments (Glass Lewis, 2023[13]; Responsible Investor, 2020[14]; Insightia, 2023[11]). Another example is a resolution filed in 2021 at HSBC Bank, which is listed in London and Hong Kong (China). The resolution, which was withdrawn when HSBC put forward an alternative resolution, was for the bank to publish targets to reduce its exposure to fossil fuels (HSBC, 2021[15]). Similarly, there has been an increase in Korea, with the first environmental shareholder resolution in 2022, leading to environmental resolutions at 12 companies that year (Insightia, 2023[11]).

Survey evidence shows that in the Asia-Pacific region,1 support for ESG shareholder resolutions is lower, at 10% for environmental proposals (69 total) and 16.7% for social proposals (16 total), compared to 82.7% for governance proposals (83 total) in 2021-22 (Insightia, 2022[9]).

There are various resources available to encourage and support shareholder resolutions in Asia.2 For instance, there is a Climate Earth guide for institutional investors “considering shareholder resolutions as a complement to other stewardship options when engaging with companies on climate‑related matters”. The guide provides analysis on the framework for shareholder climate resolutions in China, Hong Kong (China), India, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Viet Nam. In all of these jurisdictions, shareholder climate resolutions can be proposed, however the process and requirements to do this vary (ClientEarth, 2022[10]).

The Climate Earth guide for institutional investors highlights that the legal framework varies across Asian jurisdictions and there are key differences. Firstly, the scope of the types of matters on which shareholders can generally bring resolutions varies across Asian jurisdictions. For example, in Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore the scope of matters is wider and shareholder climate resolutions are not precluded. Secondly, there may be circumstances where the articles of association need to be amended to give effect to a shareholder climate resolution or the resolution could be to amend the articles of association to add a climate target. For example, in India and the Philippines, climate resolutions are generally not in scope for shareholders to file a resolution on, instead the company’s articles of association may need to be amended to expressly permit such resolutions. Thirdly, certain forms of meetings (e.g. annual general meeting (AGM) or extraordinary general meeting (EGM)) may be more appropriate for shareholders to bring climate resolutions, and this will vary across Asian jurisdictions. For instance, in Viet Nam for joint stock companies, a general meeting of shareholders (GMS) is typically the appropriate meeting, which can either be in the form of an AGM or EGM. This includes for resolutions to change the articles of association if the matter does not already fall within the scope of matters that a GMS can decide (ClientEarth, 2022[10]).

In terms of the substance of climate‑related resolutions, depending on whether the aim is to enhance governance or disclosure, they tend to oppose director appointments, auditor appointments or financial statements. For example, an activist investor gained support from institutional investors for a shareholder resolution that resulted in the election of three new directors with a climate focus on the board of ExxonMobil (NY Times, 2021[16]). The common categories of requests in shareholder climate resolutions include calls for: increased transparency and disclosure; setting a long‑term net-zero goal; developing a Paris Agreement‑aligned strategy or transition plan with interim and long‑term goals, and providing the opportunity for shareholder approval for these plans; future capital investment to align with emissions reduction targets; and disclosure of climate and energy policy advocacy and advertising (ClientEarth, 2022[10]).

Relatedly, Asian regulators are increasingly indicating that they support active ownership. For example, a number of jurisdictions have introduced stewardship codes to encourage investors to monitor the companies they invest in, which often aims to encourage investor engagement on a wide range of issues and how they exercise their vote. For instance, in Korea, a Stewardship Code was introduced in 2016, containing seven soft law principles for participating institutional investors to monitor investee companies and actively engage when issues are identified (KCGS, 2016[17]). Since the Code was introduced, there has been an increase in engagement, visible for instance through a rise in dissenting votes by institutional investor and letters to companies requesting them to improve governance (Chun, 2022[18]).

In Japan, the Stewardship Code, originally introduced in 2014 and revised in 2020, requires institutional investors to engage constructively, or have purposeful dialogues with investee companies to enhance the returns for clients, while taking into account medium- to long-term sustainability, including ESG factors, in line with their investment management strategies (FSA, 2020[19]). Analysis shows that the Code has influenced the voting activities of certain financial institutions and institutional investors (Tsukioka, 2020[20]). The Japanese Financial Services Agency has also noted that “[e]ngagement and exercise of voting rights play an important role as one of the investment methods that are used in conjunction with ESG integration. Many asset management firms recognize the significance of engagement in active investment […] and are working to improve corporate values while managing milestones”. The outcomes of engagement and exercise of voting rights can include: deepening the understanding of investee companies by discussing their businesses and management strategies, as well as ESG-related business opportunities and risks and their responses; encouraging companies with deficiencies in their policies and practices relating to ESG to make changes; and providing feedback on voting rights and communicating expectations for the following year(s) (FSA, 2022[21]).

4.1.2. Court action

When engagement between shareholders and companies is insufficient to resolve issues, it may sometimes escalate to lawsuits. This includes disputes related to climate. Globally, there are 2 341 cases in the Sabin Center’s climate change litigation database. Of these, 190 were filed in the last year (from June 2022 to May 2023) and the diversity of cases appears to be growing (Higham, 2023[22]). Climate‑related court action is not as common in Asia as in other regions. In the database, there are 46 cases in Asia, covering China, India, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Pakistan, the Philippines, Chinese Taipei and Thailand. The majority of these cases are brought by stakeholders against the government or the government against companies (Sabin Center, 2023[23]).

While it is usually shareholders who have standing to sue, there are possible grounds for stakeholders to bring a suit against a corporation or its managers. Some sustainability‑related claims have taken a rights‑based approach. For example, an investigation by the Commission on Human Rights of the Philippines found that 47 major fossil fuel companies should be held accountable to citizens for the human rights harms caused by climate change. The existing laws of the Philippines were considered by the Commission to provide possible civil and criminal grounds for future action against these companies (White & Case, 2021[24]).

4.2. Climate change risks and GHG emissions reduction

A significant amount of scientific research indicates that human activities have significantly driven the increase in greenhouse gas emissions, resulting in around 1.0ºC of global warming above pre‑industrial levels (IPCC, 2021[25]). This global warming has also been proved to be related to an increasing occurrence of natural disasters. In response, the Paris Agreement was established to strengthen the global response to the threat of climate change by “holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2ºC above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5ºC above pre‑industrial levels” (United Nations, 2015[26]). Specifically, to reach the goal of restricting the global temperature increase to 1.5ºC above pre-industrial levels, it is necessary that CO2 emissions be reduced by around 45% from the 2010 level by 2030 and net‑zero emissions will need to be achieved by around 2050 (IPCC, 2018[27]).

The net-zero transition requires concerted efforts from all countries. Of the 18 Asian jurisdictions surveyed in this report, 14 have already made commitments to achieving carbon neutrality3 and/or net-zero GHG emissions4, aligning with both the Paris Agreement on Climate Change and the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. While the majority of jurisdictions have committed to achieving their goal by 2050, consistent with the timeline set in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2018[27]), there are a few exceptions, including China, India and Indonesia, which have set their target year beyond 2050 (Table 4.1).

A key feature of the Paris Agreement is its iterative five-year cycle, designed to foster increasingly ambitious climate commitments. It also establishes the framework to communicate nationally determined contributions (NDCs) in which many jurisdictions have established intermediate targets as part of their climate agendas. These intermediate targets serve as milestones towards the long‑term goal of achieving carbon neutrality and/or net-zero emissions. As shown in Table 4.1, almost all jurisdictions have set certain intermediate targets to reduce carbon emissions, or GHG emissions more broadly, by 2030. In addition, jurisdictions have also established objectives related to the development of renewable energy sources to enhance their decarbonisation efforts. For instance, China aims to reach over 1 200 GW of installed wind and solar power by 2030. However, despite all these NDC commitments and carbon neutrality pledges, national development plans still fall behind what is needed to achieve these objectives (ESCAP UN, 2022[28]).

Table 4.1. Asian jurisdictions’ commitments related to climate change

|

Jurisdiction |

Commitment area |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

GHG emissions |

Renewable energy |

Net‑zero / Carbon neutrality |

|

|

Bangladesh |

To reduce GHG emissions by 5% by 2030, and a further 10% conditional1 reduction |

To increase the share of renewables in power generation to 10% by 2041 |

No commitment |

|

Cambodia |

To reduce GHG emissions by 42% by 2030 |

To increase the share of renewable energy resources in the energy mix to 25% by 2030 from the 2020 level |

Carbon neutrality by 2050 |

|

China |

To reduce carbon intensity of GDP by over 65% in 2030 compared to the 2005 level |

To reach over 1 200 GW installed wind and solar power by 2030 |

Carbon neutrality by 2060 |

|

Hong Kong (China) |

To reduce carbon emissions by 50% in 2035 compared to the 2005 levels |

To increase the share of renewable energy resources to 7.5-10% of total electricity generation by 2035, and to 15% by 2050 |

Carbon neutrality by 2050 |

|

India |

To reduce the emissions intensity of its GDP by 45% by 2030 from 2005 levels |

To increase renewable energy sources to 50% of its electricity requirements by 2030 |

Net-zero GHG emissions by 2070 |

|

Indonesia |

To reduce 31.89% of GHG emissions by 2030, and a further 43.2% conditionally1 |

To achieve an energy mix of new and renewable sources of energy to at least 23% by 2025 and 31% by 2050 |

Net-zero GHG emissions by 2060 or sooner |

|

Japan |

To reduce its GHG emissions by 46% in 2030 from 2013 levels |

To increase renewable power generation target to 36-38% of the total power generation mix by 2030 |

Carbon neutrality by 2050 |

|

Korea |

To reduce GHG emissions by 40% by 2030 from 2018 levels |

To increase renewables to at least 21.6% of total electricity generation in 2030 |

Carbon neutrality by 2050 |

|

Lao PDR |

To reduce GHG emissions by 60% by 2030 and further conditional1 targets |

To increase renewable energy capacity to 1 GW solar and wind power and 300 MW biomass power capacity by 2030 |

Net-zero GHG emissions by 2050 |

|

Malaysia |

To reduce 45% of economy-wide carbon intensity5 by 2030 from 2005 level |

To increase the total installed capacity of renewable energy to 31% by 2025 and 40% by 2035 |

Net-zero GHG emissions by 2050 |

|

Mongolia |

To reduce GHG emissions to 22.7%, and a further 4.5% conditional1 reduction by 2030 from 2010 levels |

To reach 20% renewable energy installed capacity by 2023 and 30% by 2030 |

No commitment |

|

Pakistan |

To reduce GHG emissions by 35% by 2030, and a further 15% conditionally,1 from 2015 levels |

For 60% of all energy produced to be generated from renewable energy resources by 2030 |

No commitment |

|

Philippines |

To reduce GHG emissions by 2.71%, and a further 72.29% conditionally1 by 2030, from 2011 levels |

To increase the share of renewable energy in the total power generation mix to 35% by 2030 and 50% by 2040 |

No commitment |

|

Singapore |

To reduce emissions to around 60 MtCO2e by 2030 |

To deploy at least 2 GWp of solar power by 2030 and launch a hydrogen strategy |

Net-zero GHG emissions by 2050 |

|

Chinese Taipei |

To reduce GHG emissions by 23-25% by 2030 compared to the 2005 level |

To increase renewable energy to 27-30% of total power generation by 2030 |

Net-zero GHG emissions by 20502 |

|

Thailand |

To reduce GHG emissions by 30-40% by 2030 compared to the business-as-usual scenario |

To increase renewable energy to 30% in the energy mix by 2036 |

Carbon neutrality by 2050 and net‑zero GHG emission by 2065 |

|

Sri Lanka |

To reduce GHG emissions by 4% and a further 10.5% conditionally1 by 2030 |

To achieve 70% renewable energy in electricity generation by 2030 |

Carbon neutrality in electricity generation by 2050 |

|

Viet Nam |

To reduce GHG emissions by 15.8% and a further 27.7% conditionally1 by 2030 compared to the business-as-usual scenario |

To increase the utilisation rate of renewable energy from about 7% in 2020 to more than 10% in 2030 |

Net-zero GHG emissions by 2050 |

Notes:

1 Conditional contributions are based on the jurisdiction receiving funding for the actions to meet these targets.

2 Chinese Taipei has established a target even without being a signatory of the Paris Agreement.

Source: See Annex C of this report for relevant sources by jurisdiction.

The measurement and disclosure of corporate GHG emissions (and reductions) is central to understanding a company’s contribution to climate change, as well as its progress towards potential emissions reduction targets. In addition, given that a significant share of companies, measured by global market capitalisation, are exposed to financially material risks related to climate change (see Figure 1.4), there is widespread investor interest in such disclosure. Particularly, this information is essential for shareholders to efficiently engage with companies and to influence and support the necessary business transformation of companies. Regulators and international standard-setting bodies have responded accordingly, with GHG emissions representing an essential part of sustainability disclosure standards outlined in Table 2.2.

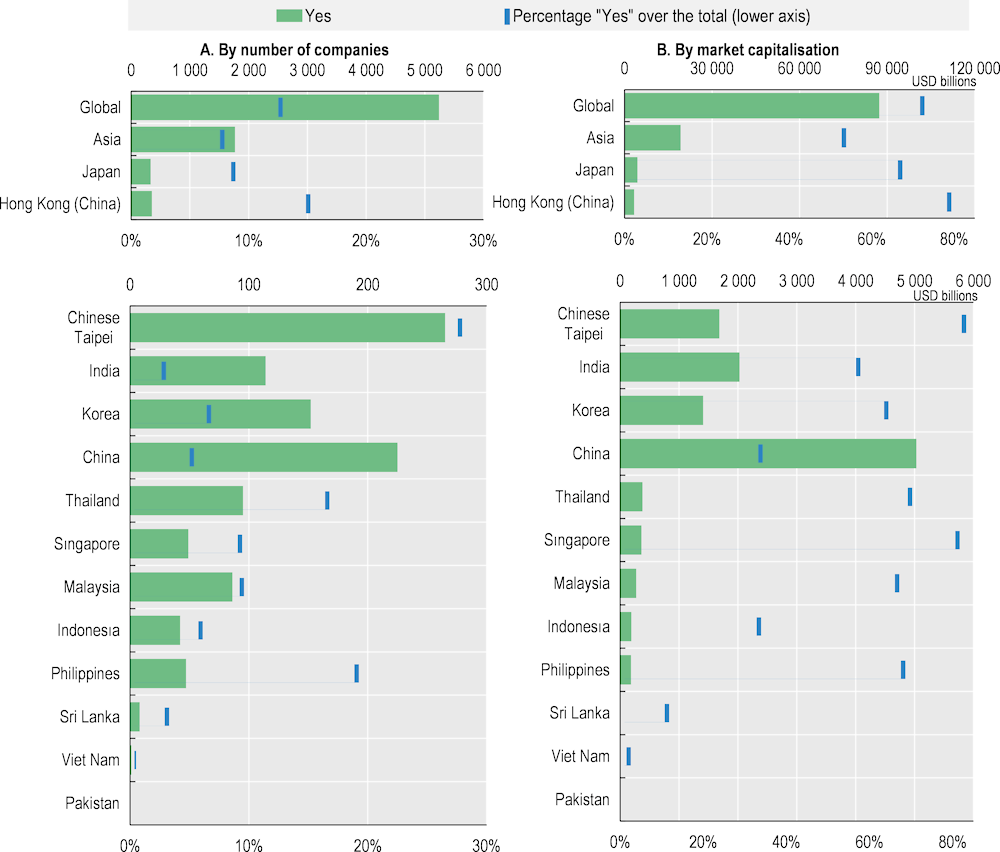

GHG emissions are divided into three different scopes. Scope 1 covers direct emissions, scope 2 refers to indirect emissions such as purchased and consumed energy, and scope 3, the broadest category, covers indirect emissions through a company’s value chain. The ISSB will require disclosure on all three scopes in its standards (IFRS, 2022[29]). Figure 4.1 shows the share of listed companies disclosing information on scope 1 and 2 emissions at the end of 2021. Globally, 5 239 companies representing 72% of the global market capitalisation publicly disclosed this information. This is a significantly higher share than in Asia, where it is only 53% (1 766 companies). However, the share differs substantially between jurisdictions, ranging from 82% in Chinese Taipei to 0% in Pakistan. The median share by market capitalisation in the Asian jurisdictions displayed below is 65%.

Figure 4.1. Disclosure of Scope 1 & 2 GHG emissions by listed companies, end-2021

Note 1: The “total” in “percentage of ‘Yes’ over the total” includes all listed companies within each category, including those for which there is no available information. For instance, in the case of the global category, the percentage is calculated over 41 802 worldwide listed companies, while in Asia the percentage is calculated over 23 304 companies.

Note 2: Only the companies that reported both scope 1 and scope 2 emissions are counted in the analysis.

Note 3: Asian data on sustainability do not include relevant information about Bangladesh, Cambodia, Lao PDR and Mongolia.

Note 4: The information provided in these tables was retrieved from LSEG and Bloomberg, therefore, it may differ from the national statistics. Source: OECD Corporate Sustainability dataset, LSEG, Bloomberg. See Annex for details.

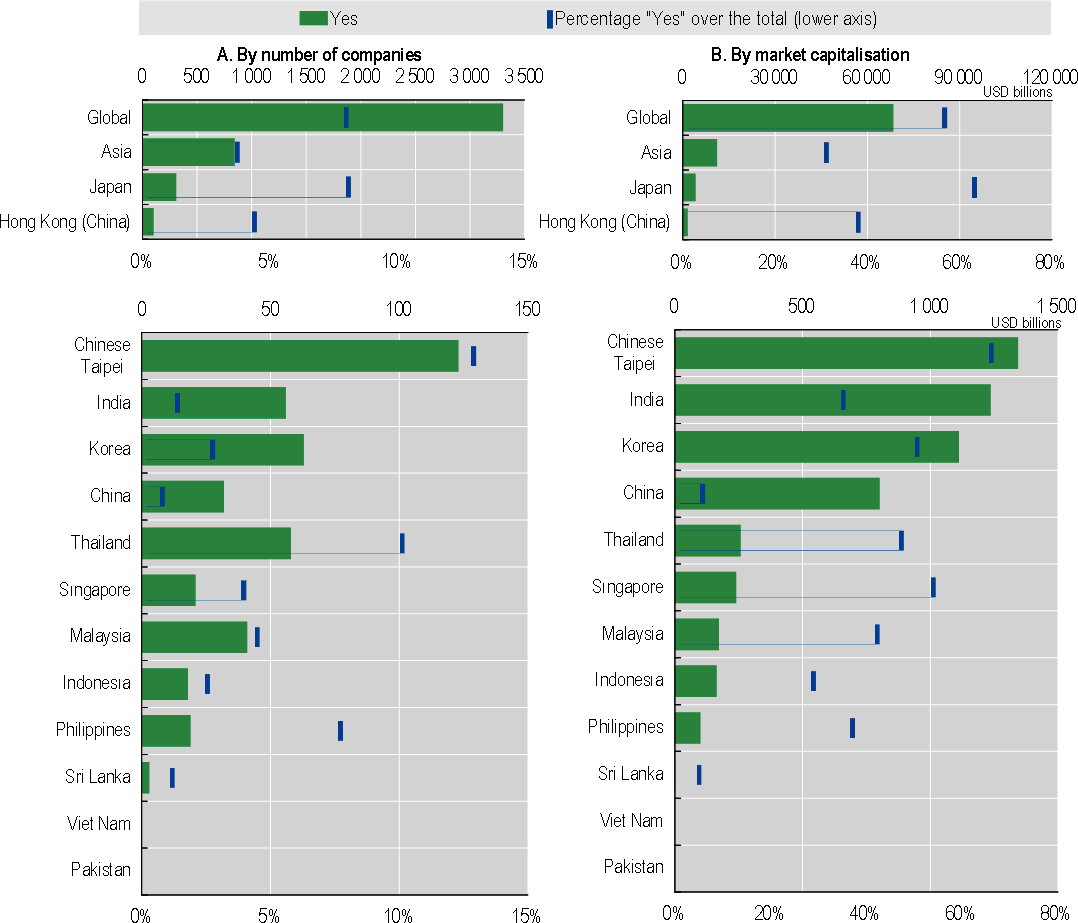

Scope 3 is by far the most wide-spread measure and makes up the majority of emissions in most industries. While there are naturally significant sectoral differences, it is estimated that scope 3 emissions account for 75% of total emissions on average across industries (CDP, 2023[30]). As it refers to indirect emissions, scope 3 is also the most difficult to measure. This is reflected in the share of companies disclosing these emissions. As shown in Figure 4.2, only 3 303 companies globally and 846 in Asia, (representing 56% and 31% of total respective market capitalisation) disclosed scope 3 emissions at the end of 2021. That is markedly lower than the disclosure of the more easily estimated scope 1 and 2 emissions. Similar to the disclosure of scopes 1 and 2, Chinese Taipei is the Asian jurisdiction with the highest share of companies disclosing scope 3 emissions at 66% of total market capitalisation, followed by Japan (63%), Singapore (53%) and Korea (50%). Recognising the complexity of estimating scope 3 emissions, the ISSB will develop relief provisions as part of its disclosure requirements to help corporations apply them, including possible safe harbour provisions to limit liability related to such disclosure (IFRS, 2022[29]).

Figure 4.2. Disclosure of Scope 3 GHG emissions by listed companies, end-2021

Note 1: The “total” in “percentage of ‘Yes’ over the total” includes all listed companies within each category, including those for which there is no available information. For instance, in the case of the global category, the percentage is calculated over 41 802 worldwide listed companies, while in Asia the percentage is calculated over 23 304 companies.

Note 2: Asian data on sustainability does not include relevant information about Bangladesh, Cambodia, Lao PDR and Mongolia.

Note 3: The information provided in these tables was retrieved from LSEG and Bloomberg, therefore, it may differ from the national statistics. Source: OECD Corporate Sustainability dataset, LSEG, Bloomberg. See Annex for details.

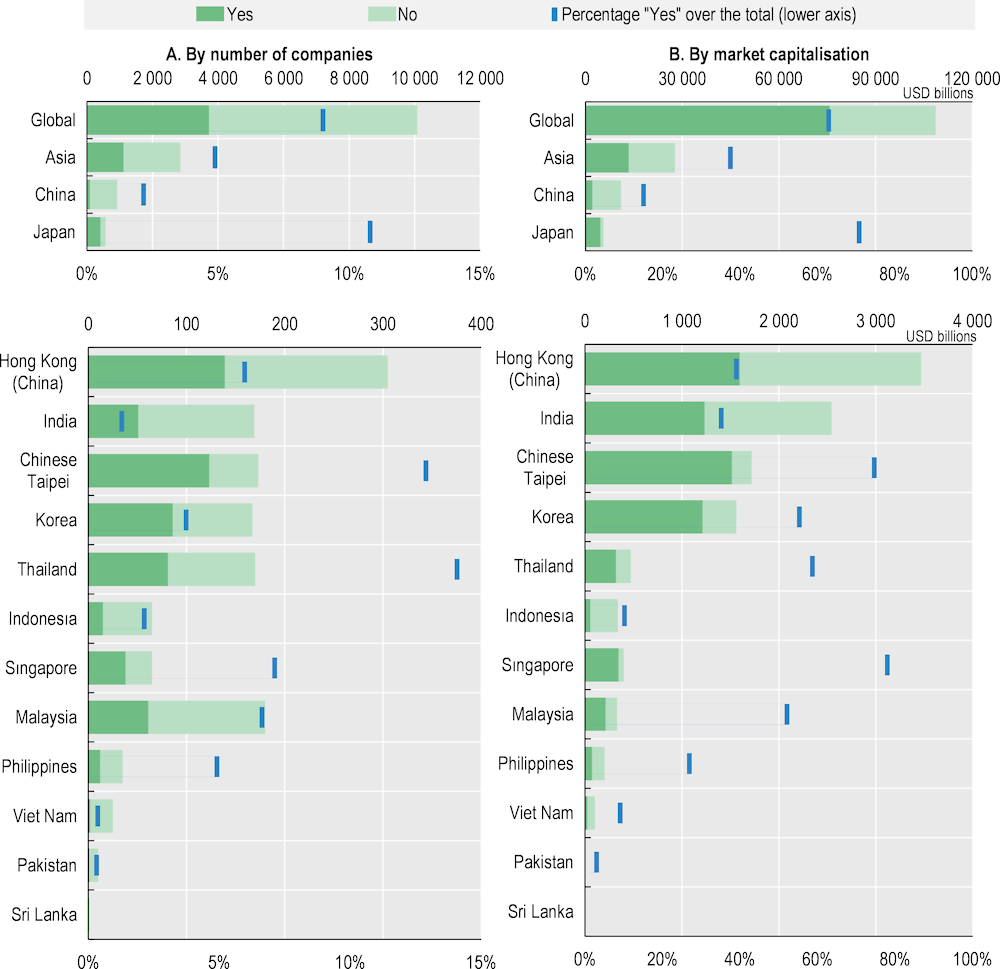

Around the world, almost 4 000 listed companies disclose their GHG emission reduction targets. As these companies are generally larger, they represent almost two-thirds of the world’s market capitalisation. This share is significantly higher than in Asia, where only 37% of companies by market capitalisation (1 118 companies) declare their GHG emissions reduction targets. However, there are significant differences across jurisdictions. While over 70% of listed companies by market capitalisation disclose their target in Japan, Singapore and Chinese Taipei, the figure is less than 10% in Indonesia, Viet Nam, Pakistan and Sri Lanka.

Figure 4.3. Disclosure of GHG emissions reduction targets by listed companies, end-2021

Note 1: The “total” in “percentage of ‘Yes’ over the total” includes all listed companies within each category, including those for which there is no available information. For instance, in the case of the global category, the percentage is calculated over 41 802 worldwide listed companies, while in Asia the percentage is calculated over 23 304 companies.

Note 2: Asian data on sustainability do not include relevant information about Bangladesh, Cambodia, Lao PDR and Mongolia.

Note 3: The information provided in these tables was retrieved from LSEG and Bloomberg, therefore, it may differ from the national statistics. Source: OECD Corporate Sustainability dataset, LSEG, Bloomberg. See Annex for details.

References

[12] BlackRock (2020), Our 2021 Stewardship Expectations: Global Principles and Market-level Voting Guidelines, https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/literature/publication/our-2021-stewardship-expectations.pdf.

[4] CDP (2023), CDP Investor Signatories, https://www.cdp.net/en/investor/signatories-and-members.

[30] CDP (2023), CDP Technical Note: Relevance of Scope 3 Categories by Sector, https://cdn.cdp.net/cdp-production/cms/guidance_docs/pdfs/000/003/504/original/CDP-technical-note-scope-3-relevance-by-sector.pdf?1649687608.

[18] Chun, S. (2022), Korea’s Stewardship Code and the Rise of Shareholder Activism, https://blogs.law.ox.ac.uk/business-law-blog/blog/2022/05/koreas-stewardship-code-and-rise-shareholder-activism.

[10] ClientEarth (2022), Net zero engagement in Asia: A guide to shareholder climate resolutions, https://www.clientearth.org/latest/latest-updates/opinions/net-zero-engagement-in-asia-a-guide-to-shareholder-resolutions/.

[6] Climate Action 100+ (2022), Investor Guide for Engaging in Asia: Engaging in Asia, https://www.climateaction100.org/news/engaging-for-ambition-in-asia/.

[28] ESCAP UN (2022), 2022 review of climate ambition in Asia and the Pacific: raising NDC targets with enhanced nature-based solutions with a special feature on engagement of children and youth in raising natinal climation ambition, https://repository.unescap.org/handle/20.500.12870/5085.

[21] FSA (2022), “Progress Report on Enhancing Asset”, https://www.fsa.go.jp/en/news/2022/20220527/20220527_4.pdf.

[19] FSA (2020), Stewardship Code, Financial Services Agency of Japan, https://www.fsa.go.jp/en/refer/councils/stewardship/20200324.html.

[13] Glass Lewis (2023), apan’s 2023 Proxy Season: Shareholder Proposals, Climate, Capital Efficiency & Gender Diversity, https://www.glasslewis.com/japan-proxy-season-preview-2023/.

[8] GSIA (2020), Global Sustainable Investment Review 2020, https://www.gsi-alliance.org/.

[22] Higham, J. (2023), Global trends in climate change litigation: 2023 snapshot, https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/publication/global-trends-in-climate-change-litigation-2023-snapshot/.

[15] HSBC (2021), Shareholders back HSBC’s net zero commitments, https://www.hsbc.com/news-and-media/hsbc-news/shareholders-back-hsbcs-net-zero-commitments.

[29] IFRS (2022), ISSB unanimously confirms Scope 3 GHG emissions disclosure requirements with strong application support, among key decisions, https://www.ifrs.org/news-and-events/news/2022/10/issb-unanimously-confirms-scope-3-ghg-emissions-disclosure-requirements-with-strong-application-support-among-key-decisions/.

[11] Insightia (2023), Corporate Governance in Asia, Corporate Governance in Asia, https://www.insightia.com/press/reports/.

[9] Insightia (2022), The Proxy Voting Annual Review 2022, https://www.insightia.com/press/reports/.

[25] IPCC (2021), Summary for Policymakers, https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/#SPM.

[27] IPCC (2018), Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5ºC, https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/.

[17] KCGS (2016), Korea Stewardship Code: Principles on the Stewardship Responsibilities of Institutional Investors, Korea Institute of Corporate Governance and Sustainability, https://sc.cgs.or.kr/common/aboutdown.jsp?fp=agMgb5yRtiV6r6qmSXlBSw%3D%3D&fnm=fPT20vKlTVaBTmwVIXQKWRY7h1HGP329JwlrMs0U9YGMI2jGfUWXUHjQXo63NONjOKfdEeoXt%2FZGxHDQEgQoXQAp71n60naW8uLQCSglNbs%3D.

[3] MSCI (2022), Say on Climate: Investor Distraction or Climate Action?, https://www.msci.com/www/blog-posts/say-on-climate-investor/03014705312.

[16] NY Times (2021), Exxon’s Board Defeat Signals the Rise of Social-Good Activists, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/09/business/exxon-mobil-engine-no1-activist.html (accessed on 5 July 2023).

[2] OECD (2023), G20/OECD Principles of Corporate Governance 2023, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/ed750b30-en.

[7] OECD (2023), Sustainability Policies and Practices for Corporate Governance in Latin America, Corporate Governance, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/76df2285-en.

[1] OECD (2022), Climate Change and Corporate Governance, Corporate Governance, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/272d85c3-en.

[5] Pew Research Centre (2021), In Response to Climate Change, Citizens in Advanced Economies Are Willing To Alter How They Live and Work, https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2021/09/14/in-response-to-climate-change-citizens-in-advanced-economies-are-willing-to-alter-how-they-live-and-work.

[14] Responsible Investor (2020), Japan’s first climate resolution receives substantial support at Mizuho, https://www.responsible-investor.com/japan-s-first-climate-resolution-receives-substantial-support-at-mizuho/.

[23] Sabin Center (2023), Global Climate Change Litigation Database, http://climatecasechart.com/ (accessed on 4 July 2023).

[20] Tsukioka, Y. (2020), “The impact of Japan’s stewardship code on shareholder voting”, International Review of Economics & Finance, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1059056018309973#:~:text=My%20results%20demonstrate%20that%20Japan%27s,and%20the%20corporate%20governance%20system.

[26] United Nations (2015), Paris Agreement, https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2015/cop21/eng/l09r01.pdf.

[24] White & Case (2021), Climate change disputes: Sustainability demands fuelling legal risk, https://www.whitecase.com/insight-our-thinking/climate-change-disputes-sustainability-demands-fuelling-legal-risk.

Notes

Notes

← 1. Data is from Asia‑Pacific‑based companies in the 2021-22 proxy season.

← 2. Shareholder “climate resolutions” has been “understood as shareholder‑filed resolutions which concern a company’s governance, disclosure or business strategy on climate change and which can complement other stewardship options” (ClientEarth, 2022[10]).

← 3. Carbon neutral means that the amount of CO2 released into the atmosphere by a company's activities is offset by removing an equivalent amount of CO2 from the atmosphere.

← 4. Net-zero GHG emissions refers that from a company’s activities eliminates any GHG emissions.

← 5. Carbon intensity refers to greenhouse gas emissions intensity from seven gasses, namely carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), perfluorocarbons (PFCs), sulphur hexafluoride (SF6) and nitrogen trifluoride (NF3).