As the digital economy is a multidimensional phenomenon, any framework for measuring it requires multiple perspectives. This chapter outlines the transition from conventional Supply and Use Tables (SUTs) to Digital SUTs, with three dimensions for measuring the digital economy: the nature of the transaction, the goods and services produced and the new digital industries. The chapter also presents the high priority indicators that countries are encouraged to compile using the Digital SUTs.

OECD Handbook on Compiling Digital Supply and Use Tables

2. Framework for digital SUTs

Abstract

The basic framework

Fundamental concepts

Many publications present estimates of how digitalisation is affecting the economy. These include a few that are consistent with the System of National Accounts (SNA), and some of these were discussed in Chapter 1. However, a framework that can bring some of these estimates together in a consistent and internally comparable way has so far been absent.

This chapter describes in more detail the framework behind the Digital Supply and Use Tables (Digital SUTs) including the terminology and definitions of the framework. It is important to emphasise that the terminology and definitions proposed in this handbook and other complementary documents are intended for statistical measurement purposes. While the framework attempts to maintain consistency with the terminology and definitions used in other digital economy contexts, some differences are required in order to align with the conventional SUTs, which the Digital SUTs are based on.

The SUTs within the SNA are different from the standard accounts in that they are a “global table” (Lequiller and Blades, 2014[22]). This refers to the fact that they show the supply (production or import) and use (consumption, investment or export) of every group of products in the economy. Furthermore, the tables are split via industrial activity classification, therefore ensuring that “everything made by someone, is used by someone else” (Lequiller and Blades, 2014[22]).

The SUTs are a good starting point for increasing the visibility of digitalisation in the economy because:

Comprehensiveness. As all production is recorded in the SUTs, the estimates of output, value added, consumption, etc. already include the components that (within the Digital SUTs) should be broken down based on the nature of transaction or on the basis of the unit that produced it. Therefore, the task is one of re-allocation rather than estimation.

Broad availability. As outlined in the 2008 SNA, the SUTs provide “a powerful tool with which to compare and contrast data from various sources and improve the coherence of the economic information system.” (§14.3) (UNSD, Eurostat, IMF, OECD, World Bank, 2009[18]). Most developed countries produce SUTs on a regular basis as part of their existing national accounts releases. These are often undertaken as part of the compilation of annual estimates of GDP or as part of a semi-regular benchmarking exercise.

Consistency across counties. The industries and products are based on the internationally agreed industrial activity and product classifications, the International Standard Industrial Classification (ISIC) and Central Product Classification (CPC), with some regional variations.1 Therefore, a SUT database that is consistent across countries can be produced, and such a database is provided by the OECD.

Multidimensionality. As mentioned in Chapter 1, the digital economy is a multidimensional phenomenon. Thus, any framework tasked with measuring it requires multiple perspectives. The SUTs capture all facets of the economy by requiring that all supply is accounted for (as either domestic production or imports) and that it matches demand (domestic consumption and investment plus exports). Not only does this ensure that all production is accounted for, but it also provides both an industry and product perspective on the supply and use of goods and services.

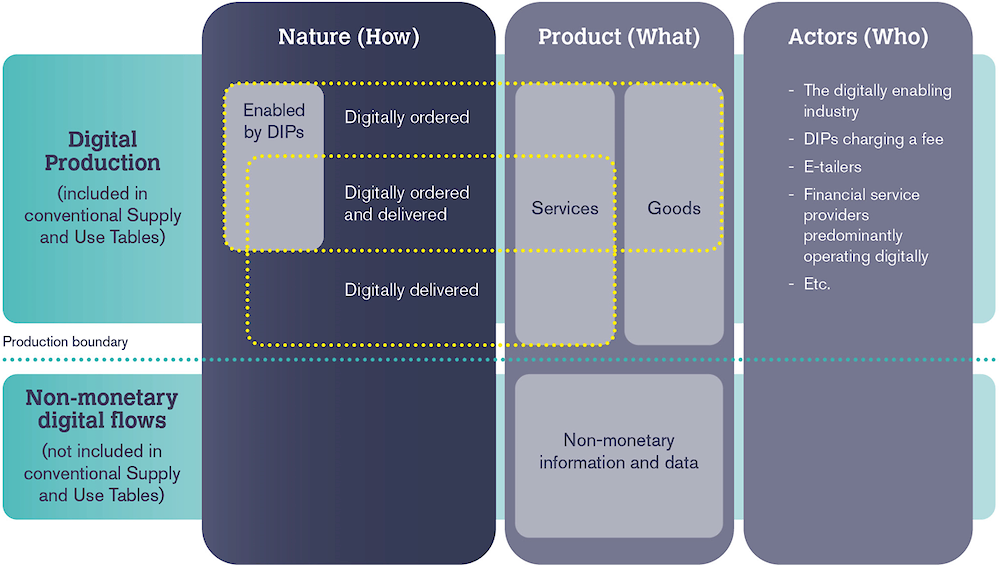

The framework of the Digital SUTs is shown in Figure 2.1. The fundamental point of delineation in the framework is the nature of the transaction (the “how”). However, in order to provide outputs that respond to policy questions, additional variables are included: the product being ordered and delivered (the “what”); and some new digital industries (the “who”). Figure 2.1 also clarifies which interactions/transactions are within the SNA production boundary (shown by a dotted line separating digital production from non-monetary digital flows).

Figure 2.1. Proposed framework of Digital SUTs

1. DIPs = Digital Intermediation Platforms.

2. There are currently seven new digital industries; the last column in Figure 2.1. shows examples. The full list is provided later in the chapter.

Source: (IMF, OECD, UNCTAD, WTO, 2023[13]) adapted.

Box 2.1. Defining the digital economy

A question that is often asked when it comes to measuring digitalisation of the economy is how to define the digital economy. Despite many attempts by academics, international organisations and national statistical offices, there is currently no single, generally accepted definition of what the digital economy entails. This absence of agreement could be attributed to the multidimensional nature of the digital economy. Since digitalisation has affected the production, ordering, delivery, and consumption of all most all goods and services, the delineation of the digital economy could be considered almost the same as most modern economies. Even GDP, the most well-known economic indicator produced by the national accounts, still provokes discussion regarding what is to be included and excluded, seventy years after its creation (Coyle, 2014[23]). Most historical definitions of the digital economy have focused on the characteristics that differentiate the digital economy from the rest of the economy;1 but, while helpful for policy analysis, these definitions may not be helpful for measurement purposes.

A recent OECD publication, prepared for the G20 Digital Economy Task Force (DETF) (OECD, 2020[6]) outlined the two common approaches to defining and measuring the digital economy. The first, a “bottom up” approach, considers the digital economy as limited to a finite set of economic activities that produce specific Information and Communication Technology (ICT) goods and digital services, which facilitate the digitalisation of the economy. This contrasts to the alternative (and broader) “top down” or “trend-based” view, in which the digital economy includes economic activity enabled by the use of ICT goods and digital services, reflecting the trend of digitalisation across the economy.

The digital economy can also be measured by aggregating certain products or industries, seen as representing digitalisation. Evidence of this approach was the classification and definition of the ICT sector in the ISIC Revision 4 (UNSD, 2008[24]) and the complementary list of ICT products in the CPC (UNSD, 2015[25]). These classifications are now widely used internationally. From a policy point of view however, these definitions are often considered too narrow because they miss the impact of digitalisation on the production of traditional goods and services. While growth in these newly formed industries have usually been higher than economic growth, it is likely that the output of these “narrow” interpretations of the digital economy understates the overall impact of digitalisation on the economy.

A recent attempt to merge these two approaches was the definition acknowledged in the 2020 G20 DETF ministerial declaration. This defined the digital economy as “all economic activity reliant on, or significantly enhanced by the use of digital inputs, including digital technologies, digital infrastructure, digital services, and data; it refers to all producers and consumers, including government, that are utilising these digital inputs in their economic activities” (G20 DETF, 2020[5]). Building on previous work by Bukht and Heeks (2017[26]), this was accompanied by a tiered definitional framework, which further delineated the impacts of digitalisation on the economy. These tiers, that are consistent with outputs from the Digital SUTs, separate economic units into firms that produce ICT goods and services (the digitally enabling industry), firms that are reliant on these digital inputs (other new digital industries), and finally firms that are enhanced by the use of digital inputs (the remaining industries).

The question of how best to define the digital economy prompted early discussions among those interested in developing a Digital SUTs framework about the need to avoid the issue of what should be included or excluded and focus instead on gaining a better understanding of how digitalisation impacts the economic transactions being measured. The Digital SUTs provide countries with some flexibility on the choice of definition, while also implying that increasing the visibility of digital transactions (and of the products and new digital industries involved in them) is a more achievable outcome in the short term than reaching an international agreement on a statistically implementable definition.

1. Bukht and Heeks (2017[26]) provides an extensive guide to various definitions of the digital economy from 1996 to 2017.

Source: Adapted from (Mitchell, 2021[27]).

Differences between digital and conventional SUTs

The multidimensional nature of the digital economy requires a framework that can produce outputs reflecting the production and consumption of digital products as well as the production and consumption of non-digital products which are obtained through digital means, whether digitally ordered, digitally delivered or both. The SUTs are uniquely positioned to do this: they record not just what was produced and consumed but also who produced and consumed it. Moreover, additional products and industries can be added in order to provide more detail on specific topics, without disrupting the balance within the tables: output, value added and other components are simply moved between rows and columns as required.

The Digital SUTs contain the following additions to the conventional SUTs:

Six additional rows under each product (and total), separating transactions by whether they are: digitally ordered or not digitally ordered, with digitally ordered transactions further broken down into ordered directly from the counterparty or ordered via a digital intermediation platform (DIP), with a final breakdown splitting the products ordered via DIPs between resident and non-resident platforms.

Two additional columns showing the nature of the delivery of the service as either digitally delivered or not digitally delivered.

Four additional rows, representing two digital products of particular interest: digital intermediation services (DIS) and cloud computing services (CCS), as well as total Information and Communication Technology (ICT) goods and digital services that fall within the SNA production boundary.

Three additional rows, representing data and digital service products that are currently outside the SNA production boundary.

Seven additional columns for new digital industries that are considered worthwhile to show separately. The producers within these industries are aggregated based on characteristics related to the nature of the transaction or how they are leveraging digitalisation.

These additions are important. However, as will be emphasised throughout this handbook, in the initial stages of compilation it is not expected that countries will create estimates for all of them.

Later in this chapter, a set of high priority indicators will be presented. These indicators have been identified by the Informal Advisory Group on Measuring GDP in a Digitalised Economy (the body which has coordinated the development of this handbook, see Chapter 1). They represent a more attainable set of outputs that countries may aim for. In the experimental Digital SUT estimates already published by some countries, the focus has been on digital ordering and delivery related to aggregate estimates rather than a transaction breakdown for each product.

The three dimensions of the framework

The three basic dimensions of the Digital SUTs framework are:

The nature of the transaction (the “how”).

The goods and services produced (the “what”).

The new digital industries shown separately in the Digital SUTs (the “who”).

The following sections outline the definitions and concepts that underpin these three dimensions. Each dimension is further elaborated in later chapters, which provide examples of how countries are generating indicators in order to produce outputs in the Digital SUTs related to each of them.

The nature of the transaction (the “how”)

The nature of transaction is a fundamental element of the Digital SUTs. Conventional SUTs make no distinction on how a transaction is facilitated, focusing only on what product was produced and which industry produced it. Since digitalisation has allowed for such a large expansion of digital ordering and digital delivery, including for decidedly “non-digital” products such as burgers and chips, it is increasingly important to identify the digital nature of transactions.

Nature of ordering

A product can either be:

(A) digitally ordered, or

(B) non-digitally ordered.

For a digitally ordered product (A), a further breakdown is made into whether it is ordered:

(A_i) directly from the counterparty (producer), or

(A_ii) via a DIP.

With a final breakdown of products ordered via DIPs depending on if the product is ordered:

(A_ii_1) via a resident DIP, or

(A_ii_2) via a non-resident DIP.

Table 2.1 presents an example for the product row accommodation services. Theoretically, such a breakdown is conceivable for each product in the SUTs, but it is unlikely that such a breakdown will be compiled at such a detailed level for all products.

Table 2.1. Transaction types in Digital SUTs: accommodation services example

|

Accommodation services |

|

|---|---|

|

A |

Digitally ordered |

|

A_i |

Direct from a counterparty |

|

A_ii |

Via a DIP |

|

A_ii_1 |

Via a resident DIP |

|

A_ii_2 |

Via a non-resident DIP |

|

B |

Not digitally ordered |

Source: The authors.

Although shown for only a single product (accommodation services) in Table 2.1, the additional transaction breakdown is also applied to the rows displaying the total (or aggregate) of all products that are standard in conventional SUTs. The addition of the breakdowns at this level means that higher-level totals of digitally ordered (and non-digitally ordered) products can be produced for all the columns in both the Supply tables and the Use tables. However, as outlined later in the chapter, digitally ordered estimates of total exports, total imports and total household consumption are the highest priority.

Products that are digitally ordered

Transactions in digitally ordered goods and services (e-commerce) are defined in this handbook in the same way as in the Handbook on Measuring Digital Trade (IMF, OECD, UNCTAD, WTO, 2023[13]). In both cases, the definition is consistent with the definition first put forward by the OECD in 2011 in the Guide to Measuring the Information Society:

“An e-commerce transaction is the sale or purchase of a good or service, conducted over computer networks by methods specifically designed for the purpose of receiving or placing orders. The goods or services are ordered by those methods, but the payment and ultimate delivery of the goods or services do not have to be conducted online. An e-commerce transaction can be between enterprises, households, individuals, governments, and other public or private organizations. To be included are orders made over the web, extranet or electronic data interchange. To be excluded are orders made by phone, fax or manually typed email.” (OECD, 2011[28]).

Digitally ordered transactions – row (A) in Table 2.1 – are split into those where the product is purchased directly from the counterparty (the producer of the goods or services) and those that are made via a digital intermediation platform (DIP). DIPs are digital platforms designed for the purpose of receiving or placing orders. They produce an intermediation service product.

To differentiate between a transaction via a DIP and one that is direct with the counterparty (producer), it is necessary to know whether the firm facilitating the sale has any ownership of the product being sold. DIPs do not take any economic ownership of the goods and services. They are generating revenue simply by facilitating the transaction between the producer and the consumer. The evolution of DIPs and their involvement in the economy is a key example of the rise of digitalisation and a subject of significant policy interest. Further discussion on DIPs is included in Chapter 5, including their definition, how they are classified and how transactions involving them are recorded in the accounts.

Products that are not digitally ordered

Non-digitally ordered goods and services – row (B) in Table 2.1 – are also part of the breakdowns shown in Digital SUTs. This row is likely to be populated as a residual, that is, output from the conventional SUTs will be considered as non-digital by default until moved to “digitally ordered”. If an item is ordered physically or via other non-digital means, such as via the phone or email, it is included in this row even if it is purchased using an electronic payment method.

There is no further breakdown under the “not digitally ordered” transaction row because all products that are non-digitally ordered are, by definition, ordered directly from the counterparty (producer) rather than via a DIP.

Nature of delivery

Products can also be delivered to the consumer digitally or non-digitally. Digitally delivered is defined as “transactions that are delivered remotely over computer networks”2. This definition is consistent with that used for defining digital trade and includes the delivery of digital services, such as telecommunications, software and cloud computing, as well as the digital delivery of some non-digital services such as education and gambling.

Unlike ordering, which is reflected as breakdowns of the product rows, the nature of the delivery is represented as breakdowns of the columns for total output, total imports, total exports, and total household consumption, including “of which” items on the nature of delivery. Such a representation is observed in the Digital supply table produced by Statistics Canada (see Table 2.2). The inclusion of import and exports provides a direct link to the digital trade estimates consistent with the framework in the Handbook on Measuring Digital Trade (IMF, OECD, UNCTAD, WTO, 2023[13]).

Table 2.2. Digital supply table: product totals, Canada, 2019

Million Canadian dollars

|

|

Output, all digital industries |

Output, all digital industries- digitally delivered |

Total output |

Total output, industries- digitally delivered |

Total imports |

Imports, digitally delivered |

Taxes on products |

Total supply at purchasers’ prices |

Total supply at purchasers' prices, digitally delivered |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Total |

204,768 |

76,461 |

4,065,386 |

96,580 |

722,624 |

13,236 |

173,179 |

4,961,189 |

115,527 |

|

Digitally ordered |

73,953 |

50,362 |

277,933 |

65,665 |

51,723 |

9,144 |

6,696 |

336,352 |

75,019 |

|

Direct from a counterparty |

59,612 |

49,658 |

218,757 |

64,961 |

19,588 |

8,559 |

1,072 |

239,416 |

73,659 |

|

Via a resident digital intermediation |

1,193 |

704 |

1,193 |

704 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1,193 |

704 |

|

Via a non-resident digital intermediation |

3,839 |

0 |

3,839 |

0 |

984 |

584 |

70 |

4,893 |

606 |

|

Via a resident retailer or wholesaler |

9,308 |

0 |

54,144 |

0 |

31,150 |

0 |

5,555 |

90,849 |

50 |

|

Not digitally ordered |

130,815 |

26,098 |

3,787,453 |

30,915 |

670,902 |

4,092 |

166,483 |

4,624,837 |

40,508 |

Source: (Statistics Canada, 2021[29]).

The breakdown of the nature of the transaction into rows (for digitally ordered) and columns (for digitally delivered) allows for a link with outputs from the digital trade framework, as all four ordering and delivery possibilities are represented:

1. digitally ordered and digitally delivered,

2. digitally ordered and non-digitally delivered,

3. non-digitally ordered and non-digitally delivered, and

4. non-digitally ordered and digitally delivered.

This avoids the need for many additional rows specifying the nature of delivery for each of the different methods of ordering.

In practical implementation, countries often assume that if services are digitally delivered then they must have been digitally ordered. While it is possible to think of examples where this does not hold (for example, in-store purchases of an internet or mobile subscription), these cases are considered to be only a small part of digitally delivered services.

Digital delivery will be discussed further in Chapter 3.

The goods and services produced (the “what”)

While all goods and services produced in the economy are theoretically included in the Digital SUTs, the framework focuses on producing totals for ICT goods and digital services that fall within the SNA production boundary (see Overview). This includes all products that “must primarily be intended to fulfil or enable the function of information processing and communication by electronic means, including transmission and display” (UNSD, 2015[25]). This definition is used to determine the classification of ICT products included in the “alternative structures” section (part 5) of the CPC 2.1 (UNSD, 2015[25]).

In the conventional SUTs, ICT goods and digital services may be recorded in many product rows. In the Digital SUTs portions of these product rows should be aggregated to form two high-level rows: ICT goods and digital services.3

In addition, two products within ICT goods and digital services are of considerable policy interest and therefore will be shown separately in the Digital SUTs: digital intermediation services (DIS) and cloud computing services (CCS). Neither of these products is currently identified in existing product classifications, but they are of interest to users because they represent the production and consumption of a service that has fundamentally altered the way businesses operate.

The Digital SUTs also encourages the transactional breakdown of non-digital goods and services that are more likely to be digitally ordered and/or digital delivered. Examples include travel services, transport, accommodation and food services. Non-digital products that are rarely, if ever, transacted digitally (such as trade in primary commodities, or wholesale business services) are within scope of the Digital SUTs, but identifying the nature of the transaction for these products is a low priority.

A final inclusion from the product perspective within the Digital SUTs framework concerns three products that are outside the current SNA production and asset boundary. These are: data, zero priced digital services provided by enterprises, and zero priced digital services provided by the community. The status of data is expected to change in the 2025 SNA, as it is likely to be acknowledged as a Produced asset in the central framework (“core accounts”). However, production and consumption of zero priced digital services are likely to remain outside the central framework. Nevertheless, due to the analytical value of such estimates, countries are encouraged to complete these additional lines in the Digital SUTs. Completion could form the basis of a digital economy satellite account (DESA), discussed in the Overview.

More information on ICT goods and digital services and on the two newly identified digital products – DIS and CCS – is provided in Chapter 4. This chapter includes information on how countries are currently attempting to delineate ICT goods and digital services from existing product rows and to derive estimates of DIS and CCS.

The new digital industries (the “who”)

The “who” perspective of the Digital SUTs relates to the creation of new digital industries. These industries are shown in separate columns in order to quantify digitally enabled activities that are not visible in the conventional SUTs. At present, seven new digital industries have been identified:

The digitally enabling industry.

DIPs charging a fee.

Data- and advertising-driven digital platforms.

Producers dependent on DIPs.

E-tailers.

Financial service providers predominantly operating digitally.

Other producers only operating digitally.

The new digital industries are based on classifying producers by how they utilise digital technologies within their business models or to interact with consumers, rather than the fundamental type of economic activity undertaken,4 which is the basis for classification in the conventional SUTs. For example, a retailer becomes an e-tailer if they receive most of their orders, based on value, digitally. In practice, this means that two economic entities that are currently classified in separate ISIC industries due to their fundamental economic activity may be placed in the same digital industry within the Digital SUTs if they are leveraging digitalisation in the same manner. For example, a bookmaker (gambling services) and a tertiary education provider (education services) would be classified separately in the conventional SUTs but would be placed together in other producers only operating digitally in the Digital SUTs, if they are both only delivering their services digitally.

Separating out firms and other producers into the new digital industries will provide important perspectives on the amount of output, value added, compensation of employees and even employment being provided by industries that are reliant on digitalisation. A broader discussion, covering the definition and possible collection methods for all digital industries is included in Chapter 5.

Outputs of the Digital SUTs

The Digital SUTs have not been designed to produce a single estimate that represents the whole digital economy. Rather, as discussed above, they are based on a multidimensional approach which generates estimates on a range of perspectives of the economy being affected by the digital transformation. Some examples of these outputs include:

Household expenditure/consumption online (totals and breakdowns for specific products).

The value of digitally traded goods and services.

The value of ICT goods and digital services in the economy, and their (likely) growing contribution to production over time.

Expenditure on products purchased via a third party (DIP).

Digitally delivered products including the proportions delivered domestically and exported.

The amount of output and value added produced by units within the new digital industries (producers that predominately interact with consumers on a digital basis).

High priority indicators of the Digital SUTs

The Digital SUTs framework presented in this chapter is ambitious. The additional rows and columns are added to all products for consistency, but it is not expected that any country will be populating all rows and columns.5 Therefore, the Informal Advisory Group on Measuring GDP in a Digitalised Economy proposed a set of high priority indicators for countries compiling Digital SUTs, focusing on some of the most important outputs from a user perspective. Agreeing on high priority indicators helps the co-ordination of initial results derived from the Digital SUTs and maximises its use as an internationally comparable framework. It also provides a more obtainable goal for countries to aim for in early stages of development.

The high priority indicators are:

1. Expenditure split by nature of the transaction. Indicators of expenditure broken down by nature of transaction are considered highly relevant because digital ordering and delivery are often seen as the most visual representation of the digital economy for consumers and policy makers. To monitor these developments, the following indicators are proposed:

total household final consumption expenditure digitally ordered;

total imports digitally ordered; and

total exports digitally ordered.

Initially, the priority for these indicators will be digitally ordered products as this is seen as more achievable in the short term. However, similar breakdowns for digitally deliverable products are also desirable.

2. Output and/or Intermediate consumption of DIS, CCS and total ICT goods and digital services. These three indicators of intermediate consumption provide insight into the evolution of the digital transformation across industries. While it is not possible to measure the exact amount of output or value added that is due to the impact of digitalisation on the production process, an increasing percentage of intermediate consumption of ICT goods and digital services relative to other products is considered to be a good indicator. Intermediate consumption of DIS and CCS is important to better understand which industries are being most disrupted by the use of intermediation platforms or require more flexible data storage to undertake their business.

3. Digital industries’ output, gross value added (GVA) and its components.. This group of indicators relates to the seven new digital industries. If possible, the provision of subtotals for each of these industries is encouraged. Output and value added should preferably be valued at basic prices.

The initial high priority indicators were chosen after considering both their usefulness and interpretability for users as well as the feasibility of generating them in the short to medium term. There are a range of other indicators that could be pursued beyond the high priority indicators listed. For instance, as outlined in Box 2.2, looking at the characteristics of digital industries could provide useful information. While ideally countries should aim for the agreed high priority indicators, each country may wish to choose indicators produced by the Digital SUTs that are particularly relevant for them. Ultimately, the indicators published will reflect policy demands and source data availability for each country.

Box 2.2. Alternative indicators

It is well known that firms benefit from the adoption and use of digital technologies, as they can boost efficiency and productivity while fostering innovation (Gal et al., 2019[30]) (Sorbe et al., 2019[31]). Collection and dissemination of information on the growth and level of investment in digital products, as well as labour-related indicators such as hours worked or occupations for the digital industries, are useful to policy makers. Such information can contribute to analysis of productivity and provide insights into the institutional make-up of firms that comprise the digital industries.

The establishment of digital industries based on digital attributes rather than economic activity also provides benefits. Surveys on innovation uptake, labour force strategy and firm behaviour can be undertaken in order to better understand the profile of digital businesses, including the differences between them and businesses which remain classified in their traditional industries. Such information gathering and comparisons have already been done for the ICT sector (the digitally enabling industry in the Digital SUTs). For example, it is well established that, within Europe, the ICT sector is significantly overrepresented in expenditure on research and development (R&D) relative to its contribution to Gross Value Added (Eurostat, 2022[32]). The digital economy now extends beyond simply the ICT sector, so while indicators about business behaviour and profiles of units within the digital industries are not an explicit indicator included in this handbook, the definitions and classification of the digital industries offer an opportunity to further differentiate firms, allowing for greater comparison and analysis.

Notes

← 1. The exact classifications used in reach region vary, for instance within the industrial activity classification there are: the statistical Classification of Economic Activities in the European Community (NACE), the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) and the Australian and New Zealand Standard Industrial Classification (ANZIC). For products, there are: the Classification of Products by Activity (CPA) used in Europe and the North American Product Classification System (NAPCS). However, these activity and product classifications are all based on the standard industrial and product classifications, ISIC and CPC.

← 2. This is a variation on the definition used in the Handbook on Measuring Digital Trade (IMF, OECD, UNCTAD, WTO, 2023[13]). The original is “All international trade transactions that are delivered remotely over computer networks.” While the amounts represented in the Digital SUTs include cross-border transactions, they also include deliveries made domestically.

← 3. This split into two rows partially relates to the measurement of goods and services being digitally delivered. While the concept of digitally ordered extends to all products including goods this is not the case for those that are digitally delivered. As in the Handbook on Measuring Digital Trade, it is assumed that goods cannot be digitally delivered. Therefore, while almost all products can be ordered digitally and more and more services are becoming available to be delivered on a digital basis, goods are still considered to be delivered on a non-digital basis only.

← 4. The exception is the digitally enabling industry where units are classified based on the products they are producing.

← 5. The OECD database of conventional SUTs contains over 90 products. The splitting of all these products based on the nature of transaction would require an additional 540 rows. Many of the rows represent goods that cannot be digitally delivered, so the column representing the amount of this good digitally delivered is redundant.