The nature of the transaction is a fundamental element of the Digital Supply and Use Tables (SUTs) framework. The Digital SUTs break down rows and columns based on whether the product was digitally ordered and/or digitally delivered. This chapter looks at the nature of ordering and of delivery, provides definitions and explores the data sources. It also introduces digital ordering via digital intermediation platforms and considers consistency with the digital trade framework and treatment of digitally ordered retail margins.

OECD Handbook on Compiling Digital Supply and Use Tables

3. The nature of the transaction (the “how”)

Abstract

Introduction

This chapter focuses on the nature of the transaction when ordering and delivering products (the “how”, discussed in Chapter 2). The use of this perspective to delineate existing transactions is a defining aspect of the Digital Supply and Use Tables (Digital SUTs). While many other extended SUTs and satellite accounts include breaking up or aggregating existing products and industries, the splitting of a single product row based on the nature of the transaction is new. Importantly, this allows the Digital SUTs to provide an indicator of the impact of digitalisation on the ordering and provision of digital products as well as those products traditionally viewed as non-digital.

While the concept of splitting transactions based on the nature of the transaction is new for SUTs, it is already well established in business and household surveys. Some of these examples are discussed in this chapter, including their usefulness in producing Digital SUTs.

The nature of the transaction is also the fundamental link between the compilation of Digital SUTs and digital trade estimates, which are not only incorporated into the Digital SUTs but are a standalone statistical output. This connection is also discussed in the chapter.

This chapter will begin by outlining the concepts of digital ordering and digital delivery in more detail than in Chapter 2. It will then present some examples of data sources that countries may use to break down product and total rows in the Digital SUTs. The final section covers the breakdown between the retail margin and non-margin components for goods purchased digitally.

The nature of the transaction: ordering and delivery

The nature of the transaction is a fundamental element of the Digital SUTs. As discussed in Chapter 2, conventional Supply and Use Tables (SUTs) make no distinction on how the transaction is facilitated, focusing only on what product was produced, who produced it, and who consumed it. Within the Digital SUTs, the nature of transactions is reflected in two ways:

Six additional rows, under each product category and total, separating transactions by how they are ordered.

Two additional columns, located after certain expenditure aggregates, showing what part of the products is digitally delivered.

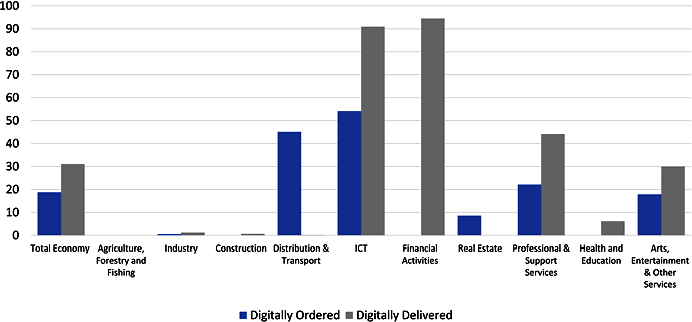

Compilers can present the nature of the transaction from either the supply or the use perspective. Figure 3.1, from the Central Statistics Office (CSO) Ireland, shows the proportion of goods and services produced that were digitally ordered and/or digitally delivered in 2020. In this case, the estimates are aggregated from rows on the supply table.

Figure 3.1. Proportion of output digitally ordered and digitally delivered, Ireland, 2020

% of total output in the sector

Note: Digitally ordered output may include digitally delivered output and vice versa.

Source: (CSO Ireland, 2022[33]).

Nature of ordering

A product can be either digitally ordered or not digitally ordered. Digitally ordered transactions can be further broken down into ordered directly from the counterparty, ordered via a resident digital intermediation platform, and ordered via a non-resident platform, as shown in Table 3.1 for accommodation services.

Table 3.1. Transaction types in Digital SUTs: accommodation services example

|

Accommodation services |

|

|---|---|

|

A |

Digitally ordered |

|

A_i |

Direct from a counterparty |

|

A_ii |

Via a DIP |

|

A_ii_1 |

Via a resident DIP |

|

A_ii_2 |

Via a non-resident DIP |

|

B |

Not digitally ordered |

Source: The authors.

As described in Chapter 2, the additional transaction breakdown is also applied to the rows displaying the total (or aggregate) of all products that are standard in conventional SUTs. The addition of the breakdowns at this level allows for the creation of high priority indicators such as digitally ordered estimates of total exports, total imports and total household consumption. While these totals can be calculated by summing up the digitally order components for each product, countries producing these estimates may find it more practical to apply transaction indicators directly to the totals.

Digitally ordered

The first line (Row A) of Table 3.1 shows digitally ordered services. In this handbook, a digitally ordered transaction is defined as:

“The sale or purchase of a good or service, conducted over computer networks by methods specifically designed for the purpose of receiving or placing orders”.

This definition is the same as that in the Handbook on Measuring Digital Trade (IMF, OECD, UNCTAD, WTO, 2023[13]), and is consistent with the one first put forward by the OECD in the Guide to Measuring the Information Society in 2011:

“An e-commerce transaction is the sale or purchase of a good or service, conducted over computer networks by methods specifically designed for the purpose of receiving or placing orders. The goods or services are ordered by those methods, but the payment and ultimate delivery of the goods or services do not have to be conducted online. An e-commerce transaction can be between enterprises, households, individuals, governments, and other public or private organizations. To be included are orders made over the web, extranet or electronic data interchange. To be excluded are orders made by phone, fax or manually typed email.” (OECD, 2011[28])

The alignment in concepts and terminology with previous initiatives provides clarity for users and ensures that compilers can leverage the measurement instruments already in place (such as e-commerce surveys) to produce estimates of digital trade.

The full definition from the 2011 Guide to Measuring the Information Society includes the specific exclusion of orders made by phone, fax or manual email. This exclusion has been a point of discussion (see Box 3.1. The different definitions of digitally ordered). As can be seen in Table 3.2, the approaches vary between countries (including between OECD countries). Therefore, it is unlikely that all surveys used to measure e-commerce and digitally ordering will converge to a single definition. This underlines the need for compilers to explain clearly to users what is and is not included in their Digital SUT outputs.

Table 3.2. Classification of economies by features of e-commerce definitions

|

|

Excludes orders via manually typed email |

Includes orders via manually typed email |

|---|---|---|

|

All “Computer Networks” |

Austria China France Hong Kong Japan Korea (Rep.) Malta Philippines Singapore Spain United Kingdom |

United States |

|

Internet only |

Canada Malaysia |

Australia Indonesia Mexico Thailand |

Source: (UNCTAD, 2022[34]).

Box 3.1. The different definitions of digitally ordered

An important consideration in the OECD’s 2011 definition of digitally ordered in the Digital SUT framework is the wording “over computer networks by methods specifically designed for the purpose of receiving or placing orders” (OECD, 2011[28]). Since this definition has been in place, it has been used in many (but not all) of the e-commerce surveys conducted by statistical offices. For example, in Australia’s “purchases made via the internet” (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2022[35]) and in the United Kingdom’s “total retail sales generated via the internet” (ONS, 2022[36]), the language of “via the internet” is used; but both definitions of internet sales are based on the previously mentioned OECD definition of e-commerce. (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2013[37]) (ONS, 2019[38]).

The clarification in the OECD’s 2011 definition was required because digitalisation has not just transformed how producers and consumers buy and sell but also how people communicate. Most communication nowadays is digital, so it could be argued that an order placed using digital hardware (a mobile phone or email) is digitally ordered. Previous OECD definitions of e-commerce had a more ambiguous definition: transactions “conducted over computer-mediated networks”. In response to concerns about different interpretations of what a computer-mediated transaction is, it was decided to make the exclusion of orders made via emails and phones more explicit (OECD, 2011[28]).

Additionally, while email reflects the impact of digitalisation, it is still fundamentally a communication device. The actual business process and accompanying production is still the same as if the order was made physically, with a human being likely to be required to read and action the email. This is in contrast to automated systems, which can generate demand for production simply by the consumer pushing buttons. Finally, the exclusion of email results in a definition that is more pragmatic and clearly defined, which avoids misinterpretation by compilers and users (OECD, 2011[28]).

Statistics Canada makes this clear by noting that “online sales, or electronic commerce (e-commerce) refers to all sales of a business's good or service where orders were received, and the commitment to purchase was made, over the internet. [Respondents should] include sales made on this business's or organization's website and third-party websites and apps. [Respondents should] exclude the delivery of digital products and services for which orders were not made online and orders received or commitments to purchase made by telephone, facsimile or email.” (Statistics Canada, 2022[39])

A similar distinction is made by Eurostat which considers e-commerce “the sale or purchase of goods or services, whether between businesses, households, individuals or private organizations, through electronic transactions conducted via the internet or other computer-mediated (online communication) networks […] Orders via manually typed e-mails, however, are excluded” (Eurostat, 2022[40]).

The US Census Bureau, on the other hand, takes a broader approach. In their annual retail trade survey, they define e-commerce as “the sales of goods and services where the buyer places an order, or the price and terms of the sale are negotiated, over an internet, mobile device (M-commerce), extranet, Electronic Data Interchange (EDI) network, electronic mail, or other comparable online system. Payment may or may not be made online” (United States Census Bureau, 2020[41]). It would be useful to try to quantify how much this difference in definition impacts on the estimates of e-commerce in the United States compared with Europe, Australia and Canada.

The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), in its Manual for the Production of Statistics on the Digital Economy (UNCTAD, 2021[42]), advocated collecting data on orders received or placed over the internet, including by email, in order to reflect different levels of technological development across countries. During a recent stocktake exercise, UNCTAD presented a list showing whether the definitions used by countries a) cover all computer networks or just the internet and b) include manually typed emails.

A key aspect of the rise in digital ordering has been the increase in the role of Digital Intermediation Platforms (DIPs) in facilitating orders. Therefore, digital ordering is broken down into two categories:

Orders that are made directly from the counterparty to the transaction (the producer or retailer), and

Orders that are made via a DIP.

The Informal Advisory Group on Measuring GDP in a Digitalised Economy decided to separately identify transactions involving DIPs due to their disruptive role in the economy, the high policy interest and specific measurement challenges they pose. Chapter 4 covers DIPs in more detail.

An “of which” split is made to transactions recorded via a DIP into those made via resident DIPs and those made via non-resident DIPs. This gives the final breakdown shown in Table 3.1. A more detailed definition of each of these categories is provided below.

Digitally ordered direct from a counterparty

The second line (Row A_i) of Table 3.1 shows the category “digitally ordered direct from a counterparty”, which involves the digital ordering of products directly with the producer or retailer (the owner of the product). This would usually occur via the producer’s website or application (‘app’) and cannot involve any other third party to the transaction. Examples include the purchase of flights direct from an airline’s website, or clothing direct from the brand’s website or a loaf of bread via a supermarket’s e-commerce app. While in these examples there is a difference between the airline (the producer of the services ultimately provided) and the supermarket (a retailer, not the producer of the bread), they both have ownership of the product being purchased, so they are both considered a counterparty to the transaction.

Ordered via a resident or non-resident DIP

The transaction ordered “via a DIP” in the third line (Row A_ii) of Table 3.1 involves any good or service purchased through a DIP. This is a sub-set of “digitally ordered” because, by convention, all ordering via a DIP must be digital in nature (IMF, OECD, UNCTAD, WTO, 2023[13]). In this case, the DIP has no ownership of the good or service being purchased and is acting only as a facilitator of the transaction, bringing the buyer and seller together. A broader discussion on DIPs, including transactions relating to them, is provided in Chapter 4.

There is an additional split between DIPs that are residents of the same country as the institutional unit undertaking the ordering and DIPs that are non-residents. This additional split may be difficult to compile due to the lack of information that consumers have on the DIP they are using. This is one of the aspirational outputs of the Digital SUTs. It is included because having a split between purchases via resident and non-resident DIPs would help to determine the amount of digital intermediation services being imported compared with the amount that is produced and consumed domestically. The estimation of this non-resident split may be possible to do in different ways, including even as a residual if the amount of total intermediation services consumed and the amount produced domestically are both known.

Not digitally ordered

The final transaction row (Row B) in Table 3.1 represents orders made non-digitally, which are also part of the breakdowns shown in Digital SUTs. A transaction being included in this row does not preclude electronic payment if the item was ordered physically or via other non-digital means, such as on the phone. Conceivably, a transaction could be recorded in this row while also being recorded as digitally delivered. An example is mobile or broadband telecommunication services that may be purchased “over the counter” but are delivered digitally. That said, the vast majority of transactions that are recorded in this row will also be delivered non-digitally.

Since this is the traditional mode of transactions, it is assumed that this row will likely be populated as a residual. In other words, output when it is taken from the conventional SUTs will be considered as non-digital by default, until it is moved to one of the “digitally ordered” rows.

There is no further breakdown under the “not digitally ordered” transaction row because all products that are non-digitally ordered are, by definition, ordered directly from the counterparty (producer) rather than via a DIP.

Nature of delivery

Products can be delivered digitally or non-digitally. The nature of the delivery is represented as breakdowns of the columns for total output, total imports, total exports, and total household consumption expenditure, shown as “of which” items. Unlike digital ordering, there is only one choice: digitally delivered or not digitally delivered.

Digitally delivered is defined within the Digital SUTs as “transactions that are delivered remotely over computer networks”. This definition is consistent with that used in the Handbook on Measuring Digital Trade (IMF, OECD, UNCTAD, WTO, 2023[13])1 and includes the delivery of digital services, such as telecommunications, software and cloud computing, as well as the digital delivery of some non-digital services such as education and gambling.

The breakdown of the nature of the transaction into rows (for digitally ordered) and columns (for digitally delivered) provides a consistent way to record all the different interactions between producers and consumers as all four ordering and delivery possibilities are represented. These are:

1. digitally ordered and digitally delivered;

2. digitally ordered and non-digitally delivered;

3. non-digitally ordered and non-digitally delivered; and

4. non-digitally ordered and digitally delivered.2

This avoids the need for many additional rows specifying the nature of delivery for each of the different methods of ordering.

Digitally delivered vs digitally deliverable

Some services are entirely digital in nature and as such, as well as meeting the definition of a digital product (see Chapter 4), they will always be digitally delivered. For example, downloadable software and streaming media will always be delivered digitally as it is not possible to provide them in a non-digital manner. Therefore, for such products, all output is digitally delivered output. Conversely there are certain products, including all goods (by convention), that are not possible to deliver digitally. Also included in this category are many transport services, such as train or aeroplane travel, even if the service is purchased and the ticket received digitally. As the person must physically board the aeroplane or train to consume the service, it is received non-digitally. Therefore, the output is considered to be “not digitally delivered”.

There is also a group of services which can be digitally delivered but need not be. These services, referred to as “digitally deliverable”, can be delivered through computer networks (most often the internet). For example, in recent years there has been a rise in online education, and some universities are now only online. The COVID-19 pandemic increased digital delivery of education services, but most education services are still delivered physically, so such services are considered to be “digitally deliverable”. The first list of “digitally deliverable services”, at the time labelled as “potentially ICT-enabled services”, was developed in the context of international trade by the UNCTAD-led Task Group on Measuring Trade in ICT Services and ICT-enabled Services (TGServ) in 2015. This list has now been expanded in the Handbook on Measuring Digital Trade (IMF, OECD, UNCTAD, WTO, 2023[13]) to include digital intermediation services provided by DIPs. Identifying digitally deliverable services and measuring exports and imports of those services is the recommended starting point for compiling statistics on digital trade outputs.

In a similar vein, this handbook advocates the concept of “digitally deliverable” as a first stage indicator that countries may use in compiling Digital SUTs. A Central Product Classification (CPC)-based list of digitally deliverable services is included in Annex 3.A.3 This classification provides a basis for compiling an upper-bound estimate of transactions that are “actually digitally delivered” offering a solution to a couple of well-known challenges.

The first challenge is that, in practice, applying the concept of digitally delivered is not always as clear-cut as digitally ordered. Digital ordering of a product usually occurs instantaneously, when the button is pushed on the computer or phone. On the other hand, delivery of professional services, such as accounting, legal or engineering services may be a mixture of in-person and email exchanges. A person may receive financial services without ever stepping foot in a physical bank, but such a decision is often the choice of the consumer rather than the bank. The customer may switch between physical and digital without any interruption to the financial service they are receiving. Applying the digitally delivered concept in complex cases such as these may be challenging and requires the collection of detailed information. By contrast, it is relatively straightforward to identify whether a class of products is digitally deliverable (i.e. can be digitally delivered).

Secondly, as indicated by the scarcity of examples for collection of data on digital delivery, the measurement of digitally delivered to domestic markets has often taken a lower priority than e-commerce and digital ordering. This may reflect both the conceptual difficulties and lower policy priorities.

Therefore, compilers of Digital SUTs may consider measures of “digitally deliverable” as a starting point to develop estimates of product that are digitally delivered. As will be discussed in Chapter 6, Ireland and the Netherlands have taken this approach, whereas Canada has tried to identify the specific services and level of products being actually digitally delivered. Table 3.3 shows that these different approaches can create big differences in results, reducing comparability between countries and requiring additional explanation for users. However, the compilation of potentially digitally deliverable allows for greater consistency with digital trade estimates.

Table 3.3. Estimates of digitally delivered in Ireland, Netherlands, and Canada

|

|

Ireland |

Netherlands |

Canada |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Digitally Delivered (% of total output) |

28.5 |

22.6 |

2.4 |

Note: Ireland and Netherlands are recording digitally deliverable products. Canada is recording products actually digitally delivered. Ireland’s estimates are for 2020, Netherlands and Canada’s estimates are for 2018.

Source: OECD using (CSO Ireland, 2022[33]) (Statistics Canada, 2021[29]) (Statistics Netherlands, 2021[43]).

Consistency with measurement of digital trade

Importantly, splitting product rows and totals columns based on the nature of the transaction permits the creation of aggregate estimates of digitally ordered goods and services and digitally delivered services. These include imports of digitally delivered services in the supply table and digitally delivered exports in the use table. Additionally, the aggregate proportion of goods imported and exported that were digitally ordered is presented in the product rows.

The definitions of digitally ordered and digitally delivered are consistent with that used in the Handbook on Measuring Digital Trade (IMF, OECD, UNCTAD, WTO, 2023[13]). As such, digital trade estimates can be used in the Digital SUTs or vice versa. In their initial Digital SUTs, Statistics Canada estimated that 7.0% of imports were digitally ordered and just under 2.0% of imports were delivered digitally (Statistics Canada, 2021[29]). The benefits of consistency between the digital trade and Digital SUT frameworks extends beyond the numbers. It allows sharing of best practices between the two communities on methodology, data collection and conceptual interpretation (see Box 3.2).

As shown in a fuller description of the digital trade framework (see Annex 3.B), while the concepts are the same, the product breakdown applied within digital trade reporting is normally less detailed than that of supply and use tables. The digital trade reporting template requests services broken down by the Extended Balance Of Payments Service Classification (EBOPS).

Importantly, although EBOPS produces higher-level breakdowns than the Classification of Products by Activity (CPA) or CPC4 which are used to compile most conventional SUTs, there are already established concordances between EBOPS, CPA and CPC, and it is envisaged that during the early stages of compilation, compilers would focus on being consistent at the higher level of imports and exports (i.e. total goods and total services).

Box 3.2. Consistency between Digital SUT and digital trade concepts

Additional clarification on certain digital ordering concepts

Consistency between the concepts and definitions used when compiling estimates of digital trade and the Digital SUTs is important. The most obvious advantage of such consistency is that estimates created as part of digital trade can also be used when completing the high priority indicators as part of the Digital SUTs. Imports and exports, split based on the nature of the transaction, are a key component of the high priority indicators from the transaction perspective.

This consistency also allows for best practices and methodology to be shared between compliers, as well as for clarification of definitional and conceptual interpretations. Several of these, which relate to digital ordering and delivery, are explained in the Handbook on Measuring Digital Trade:

For digitally ordered transactions, the payment and ultimate delivery of the goods or services do not have to also be conducted online.

Orders made by phone, fax or manually typed email are excluded from digitally ordered trade.

Offline transactions formalised using digital signatures are excluded from digitally ordered trade.

Each trade transaction should be treated separately. When a transaction is established via offline ordering processes, but subsequent transactions (or follow up orders) are made via digital ordering systems, the follow-up orders should be considered as e-commerce.

The Handbook on Measuring Digital Trade also provides clarity regarding the treatment of on-going provision of services with accompanying payments (recurring transactions). Examples include subscriptions to streaming media, online software and gaming services, subscriptions for online platform delivery services and clothing rental subscriptions. Although the order is placed only once, the service continues over subsequent periods as long as it is not cancelled, and the subscription fee is paid. While the transaction (and value) associated with the initial digital order should clearly be included in the estimate of supply (and use) digitally ordered, the subsequent transactions should also be regarded as digitally ordered (i.e. an extension of the original digital order) and be recorded in digitally ordered trade.

Additionally, based on discussions with several organisations, it appears that most surveys consider these recurring payments as a continuation of the initial order, and reflect its nature. While some are attempting to make this conceptual treatment more explicit in their survey wording, in practice it is likely that firms will not have the information needed to identify the original ordering method associated with recurring payments – especially for subscriptions which began years or even decades ago. It may therefore be necessary to estimate the share of total subscription income in the current period arising from digital orders. One possibility, advocated by the Handbook on Measuring Digital Trade, is to create an estimate based on the share of digital ordering among subscriptions initiated in the current recording period. This can be conceived as reflecting the share of digital ordering which would arise if customers had to place a new order each time instead of the service automatically renewing.

Importantly, the Handbook on Measuring Digital Trade provides a useful complimentary resource to this handbook with additional examples and case studies that compilers can use to improve measurement.

Source: (IMF, OECD, UNCTAD, WTO, 2023[13]).

Data sources

Data that provides information on the level and characteristics of digital ordering and delivery can be obtained from either the producer/seller perspective or the consumer/buyer perspective. This section discusses some of the existing and proposed methods to collect this information.

The producer or seller perspective (business surveys)

Digital ordering

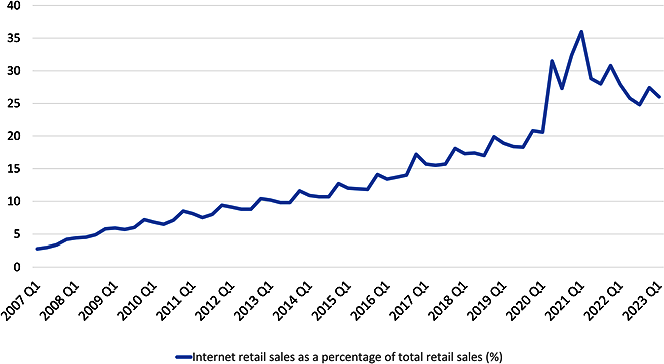

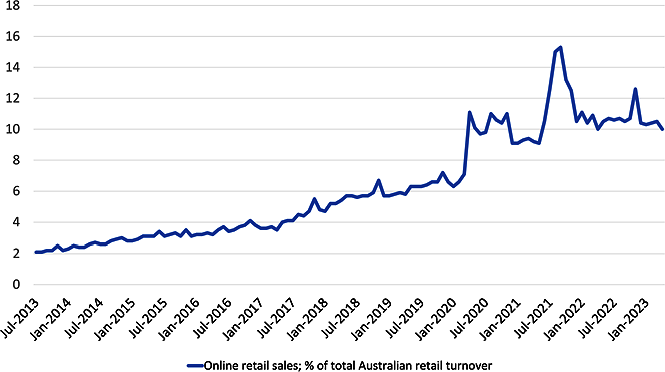

National statistical offices may add questions to existing business surveys to gather information on the nature of the transaction. Examples include the United Kingdom Office for National Statistics (ONS) and the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), which use such information to provide estimates about retail sales that take place online (Figure 3.2 and Figure 3.3), without providing additional information on the specific activity of the business or the products being transacted.5

Figure 3.2. Internet retail sales, United Kingdom, Q1 2007 to Q1 2023

% of total retail sales

Figure 3.3. Online retail sales, Australia, July 2013 to April 2023

% of total retail turnover

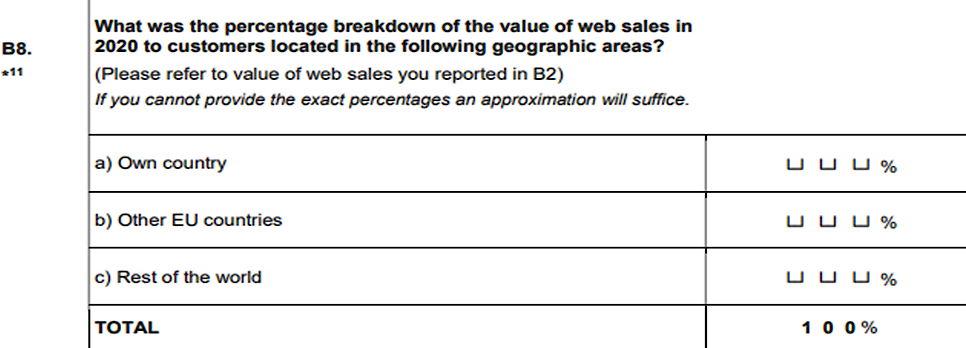

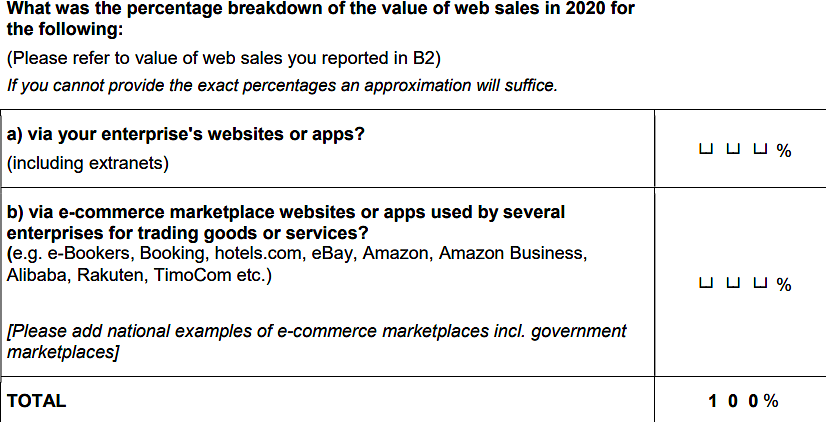

Within Europe, many countries publish estimates for e-commerce collected via surveys based upon Eurostat’s enterprise survey on Information and Communication Technology (ICT) usage and e-commerce (Eurostat, 2021[44]). These provide information either on the percentage of firms that offer e-commerce as an ordering option or the percentage of turnover from e-commerce. Annex 3.C provides examples of the survey questions used by Eurostat.

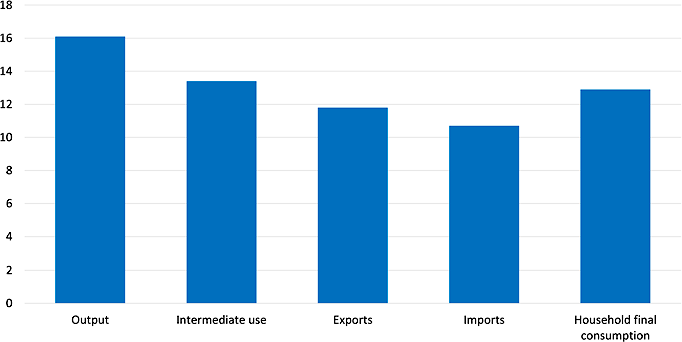

The ICT usage and e-commerce survey is the main data source for estimates of digital ordering published by Statistics Netherlands. Information from this survey was used together with data from the structural business survey and the household budget survey to break down estimates from the conventional SUTs. Estimates of digital ordering were applied to rows in both the supply and use tables, but only the aggregate estimates were published. These include total output and imports from the supply table; and exports, intermediate use and household final consumption from the use table. The results are shown in Figure 3.4.

Figure 3.4. Proportion of digitally ordered products, Netherlands, 2018

% of total that is digitally ordered

E-commerce estimates provide analytical value, for example providing insights into consumer behaviour during specific peak seasons such as Christmas and the increasing global phenomenon of Black Friday, as well as trends during periods such as the COVID-19 lockdowns. The United States, for example, publishes annual estimates of e-commerce at the aggregate level (See Box 3.3).

However, often these are high-level aggregates, and this limits their usefulness for the purpose of compiling product rows in the SUTs. Some national statistical offices are going further in their business data collection in this area, seeking to gain more information than just totals and proportions. This more granular data, collected in the United States via the annual retail trade survey (Table 3.4) and the service annual survey provides additional opportunities for compilers.6

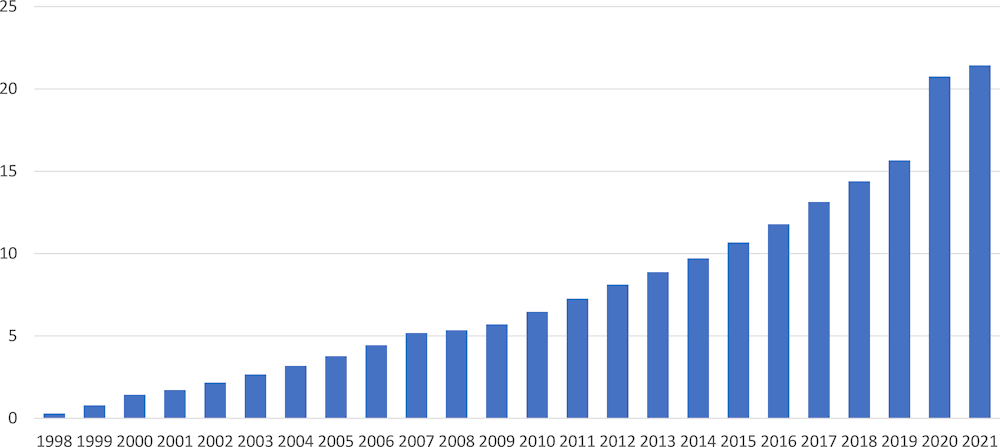

Box 3.3. Spotlight on e-commerce retail sales trends in the United States

Figure 3.5 below is based on the US Census Bureau’s retail sales survey, which provides quarterly and annual e-commerce data. The survey shows the increasing share of e-commerce in retail sales over the long term, from less than 1% in 1999 to over 21% in 2021. with a noticeable jump in 2020 in response to COVID related restrictions. These results also informed the policy discussions about how the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the adoption of digital retail as the proportion of retail sales undertaken via e-commerce jumped from 15.6% in 2019 to 20.7% in 2020.

Standardising and integrating e-commerce data into final demand estimates via the Digital SUTs framework could throw more light on e-commerce at detailed product levels and make this information more accessible to a wide range of policy users.

Figure 3.5. Share of e-commerce in retail sales, United States, 1998-2021

% of retail sales

Note: Retail sales of motor vehicles and parts dealers and gasoline stations are excluded from the author’s illustrative calculation of e-commerce share because they account for roughly 30% of total retail sales with relatively little e-commerce involved.

Table 3.4. Estimated annual retail trade sales: total and e-commerce, United States, 2021

|

NAICS Code |

Kind of business |

2021 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Total (Million US dollars) |

E-commerce |

||

|

Total retail trade |

6,522,609 |

958, 715 |

|

|

441 |

Motor vehicles and parts dealers |

1,484,108 |

D |

|

442 |

Furniture and home furnishings stores |

140,586 |

4,529 |

|

443 |

Electronics and appliance stores |

93,511 |

2,761 |

|

444 |

Building material and garden equipment and supplies dealers |

480,946 |

2,852 |

|

445 |

Food and beverage stores |

889,145 |

26,706 |

|

446 |

Health and personal care stores |

387,000 |

D |

|

447 |

Gasoline stations |

566,086 |

S |

|

448 |

Clothing and clothing access. stores |

290,652 |

20,495 |

|

451 |

Sporting goods, hobby, musical instrument, and book stores |

102,493 |

6,328 |

|

452 |

General merchandise stores |

797,704 |

D |

|

453 |

Miscellaneous store retailers |

159,503 |

8,722 |

|

454 |

Non-store retailers |

1,130,875 |

823,803 |

|

4541 |

Electronic shopping and mail-order houses |

1,027,971 |

820,843 |

Note: “D” - Estimate withheld to avoid disclosing data of individual companies; data are included in higher-level totals. “S” - Estimate withheld as it does not meet US Census Bureau’s publication standards because of high sampling variability, poor response quality, or other concerns about the estimate's quality.

The United States retail trade survey shows that e-commerce made up 14.6% of total sales in the retail industry in 2020. It takes place in all retail industries, but most of the transactions occur within a single sub-industry: non-store retailers. This sub-industry is defined in the 2017 North American Industry Classification System (NAICS)7 as “mail-order houses, vending machine operators, home delivery sales, door-to-door sales, party plan sales, electronic shopping, and sales through portable stalls” (NAICS, 2017[46]). Therefore, it covers transactions in a range of products that are separately identified in the conventional and Digital SUTs. On the other hand, many of the other sub-industries in Table 3.4 probably contribute to only one or two product rows, allowing for more straightforward link with “digitally ordered” in the Digital SUTs.

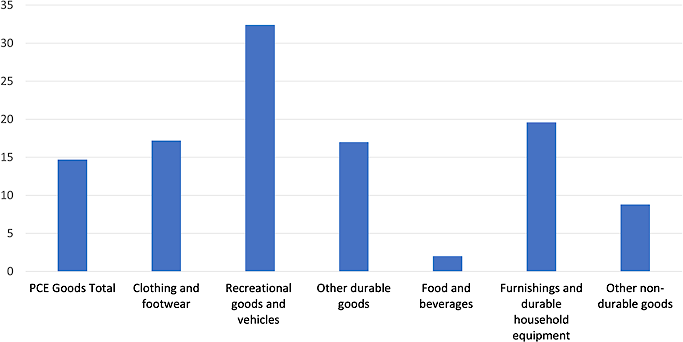

In its most recent digital economy publication, the BEA has used this e-commerce data to split up private consumption estimates (PCE)8 from the conventional SUTs. These outputs contrast with those compiled by Ireland’s CSO and shown in Figure 3.1, in that they show the nature of the transaction from the perspective of rows on the use table. The BEA data is displayed in Figure 3.6. It shows that in 2019, 14.7% of total PCE was digitally ordered. Similar to the Irish estimates, the nature of the transaction (in this case digitally ordered) is not shown for every row in the SUT; rather, rows have been aggregated to an appropriate level that improves the quality of the output.

Figure 3.6. Digitally ordered share of selected PCE goods by type of product, United States, 2019

% of goods that are digitally ordered

Note: PCE goods excludes motor vehicles and parts, gas and other energy goods, pharmaceutical and other medical products and tobacco.

Other sources can also be used to estimate e-commerce. Statistics Netherlands uses tax records and web scraping to derive estimates of imports of e-commerce, that is consumers in the Netherlands digitally ordering goods from non-resident enterprises (see Box 3.4).

Box 3.4. Measuring e-commerce imports in the Netherlands

To measure expenditure by Dutch consumers at webshops located elsewhere in the EU, a study by Statistics Netherlands used the Dutch VAT returns filed by foreign EU companies, which are mandatory across the EU for all traders exporting more than a certain threshold (EUR 35,000 or EUR 100,000 per year, depending on the EU Member State) to another EU Member State.

The VAT returns were combined with data from Bureau Van Dijk’s Orbis, a database of companies across the world. This was used to identify enterprises engaged in retail as their primary or secondary activity. Statistics Netherlands was able to match VAT records to company names, and also to match the companies with data collected through web scraping to identify the websites of the shops through which products can be ordered online. Webpages were identified on the basis of the company name, with sites checked (automatically) for the display of a shopping cart. Manual checking was undertaken to gauge the size of measurement errors in the algorithm.

The results indicate that Dutch consumers spent over 1 billion euros (excluding VAT) on products sold by foreign EU webshops in 2016, an increase of 25% relative to 2015, and six times higher than the value previously recorded with demand-side surveys of consumers. More than half of all online purchases were made at webshops located in Germany, followed by the United Kingdom, Belgium and Italy. Clothing and shoes were the main items purchased.

Classification changes

Breakdowns depend on the classifications used for e-commerce providers. In the updated version of the NAICS released in 2022, the split between store and non-store has been removed, with retail sales primarily being classified by product rather than by the method of sale (NAICS, 2022[50]). A similar change was made for the recent revisions to the statistical classification of economic activities in the European Community (NACE), and the International Standard Industrial Classification (ISIC). In ISIC Revision 5, which was endorsed by the UN Statistical Commission in 2023 (see Chapter 5), the classification has “eliminated the distinction between in-store and non-store retail trade in Division 47” (UNSC, 2022[51]).

Such changes, when implemented by countries, will help provide information on breakdowns at product level of digitally ordered transactions. In the future, e-commerce transactions are unlikely to be reported as consolidated in a single sub-industry, but instead will be spread across different industries, allowing for a better analysis of which products are being ordered on a digital basis. However, practical considerations, especially regarding firms that sell a wide range of products, may still cause compilation challenges.

Comparability

It is important to note that while most of these examples, as well as others not listed here, attempt to measure the same conceptual phenomenon (e-commerce), there are small differences between surveys used as data sources in different countries. Some of these differences relate to the question wording used in relation to digital ordering (see Box 3.1). Others might include scope differences regarding who the survey is sent to, for example only include enterprises explicitly classified in the retail industry versus all stores that provide retail services.

As will be further discussed in Chapter 6, in some regards these differences do not matter if the results are only being used as an indicator to break down rows and columns rather to create an estimate of the level of digital ordering and delivery. If the conventional SUTs are being used and are accurately compiled, conceptually the entire economy is already being captured in the estimates. This implies that there is less concern regarding minor differences in the indicators.

Digital delivery

Most of the examples so far have focused on digital ordering. This is because most business surveys collecting information on the nature of the transaction have focused on digital ordering rather than digital delivery. However, despite the relatively limited focus on mode of delivery in surveys, services being delivered digitally appear to be increasing rapidly over time.

Currently most source data available to national statistical offices to divide the specific columns (imports, exports, household consumption) into digitally delivered and not digitally delivered services are associated with international trade. For instance, trade surveys focusing on mode of supply can be used as a proxy for digital delivery. It could be argued that trade in services via Mode 1, which represents “cross-border supply: from the territory of one country into the territory of another country” (WTO, 2013[52]) is only possible if the service is able to be digitally delivered. Similarly, the concept of ICT-enabled services, defined as “services that are delivered remotely over ICT networks” (UNCTAD, 2015[53]) would appear to be broadly suitable for compiling estimates of digitally delivered services across borders. This concept, which is similar to that of “digitally deliverable” services, can be used as a starting point for estimating aggregate levels of digital deliveries, particularly as they pertain to digitally delivered imports and exports. The Handbook on Measuring Digital Trade elaborates on this and makes a similar recommendation (IMF, OECD, UNCTAD, WTO, 2023[13]).

Transforming business surveys

In response to the Digital SUTs framework and the limited amount of source data on both digital ordering and digital delivery (especially at a more granular level), some countries have undertaken efforts to update relevant business surveys to improve the data available to split transactions by their nature.

For example, the United States Census Bureau has made changes to question wording in its service annual survey to improve the breakdown between digitally ordered transactions direct with the counterparty and those made via a DIP. Following cognitive testing of the e-commerce question, they concluded that “some services respondents were not including certain categories of electronic revenues in their response, such as sales generated from third-party websites and electronic systems other than public-facing websites” (United States Census Bureau, 2018[54]). Therefore, they split the existing question into three questions. This not only improved the coverage of the survey, as responders were made more aware of the different perspectives of e-commerce, but it also allowed for a potential differentiation between transactions direct with counterparties and those that involved a third party such as a DIP. While the results of this split are not published, they allow the producers of these statistics to explore additional analyses and improve quality assurance.

The ONS has added questions to its retail trade survey (see Box 3.1) and completely re-engineered its e-commerce and ICT survey (see Box 3.5). The changes to the e-commerce and ICT survey seek a more granular level of information on a firm’s digital activity, including the nature of the transactions for both buying and selling (ONS, 2022[55]). Some of the questions that were added to the survey are presented in Annex 3.D.

Box 3.5. Developing information on the digital economy in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom’s e-commerce and ICT survey was paused in December 2020 to undergo re-development. The development work was linked with a wider initiative to consider the best approach to measuring the digital economy.

Following the pause of the survey in 2020, the team at the ONS launched a wide-reaching user engagement exercise to learn more about the needs of users and policy makers in relation to digital statistics. First, bi-lateral meetings were set up with key stakeholders across government to learn more about their needs for data linked to digital activity to help inform their decision-making. Second, a four-week user engagement exercise was launched to understand the needs of non-government users. The user engagement exercise was launched online and a link to the electronic survey was included in monthly mailouts from the ONS to over 40,000 users.

The consultation work led the ONS to develop a set of over 200 desired outputs. These required a range of data needs, each of which, if implemented, would have equated to individual questions on the redeveloped survey, increasing the survey size by almost four times. A key consideration at this stage was to try and meet the needs of users while not overburdening sampled businesses. Each of the requirements were reviewed, prioritised and reduced by over half to 80 questions in total. Not all the questions that would feature on the re-developed survey were new, as some were carried over from the existing survey or were similar to previous questions. This limited the amount of testing, as only the new questions needed to be cognitively tested.1

A small number of United Kingdom businesses were recruited to assist with cognitively testing the new questions. Over 40 recommendations were made, which resulted in some questions being removed as the relevant information could not be provided by respondents. Also, more clarification was added to ensure businesses correctly understood what should be reported.

The key changes made to the old survey include:2

Expanding the survey to collect data on e-commerce purchases.

More detailed (but still quite high-level) geographical breakdowns of consumers.

Breakdowns by types of customers: business to business, business to government and business to consumer.

Breakdowns by goods and services and whether these were digitally or non-digitally ordered and delivered.

Collecting data on actual values of e-commerce activity instead of percentages.

Specific questions regarding any interactions with DIPs.

The initial development work up to the point of dispatch spanned 14 months in total and on 28 February 2022 the re-developed and rebranded survey was dispatched. Given the scale of survey changes, the survey was relaunched as the Digital Economy Survey (DES). The DES survey is an annual survey with data collected using an electronic questionnaire from a sample of around 11,000 businesses.

1. Only new questions were subject to cognitive testing. With hindsight, a limitation of this approach was that the routing and flow of the whole questionnaire was not tested. This will need addressing before the next iteration of the survey is dispatched in 2023.

2. For a full list of questions asked on the redeveloped survey, see 2021 Digital Economy Survey: Survey Questions (ONS, 2022[66]).

Source: (ONS, 2022[55]).

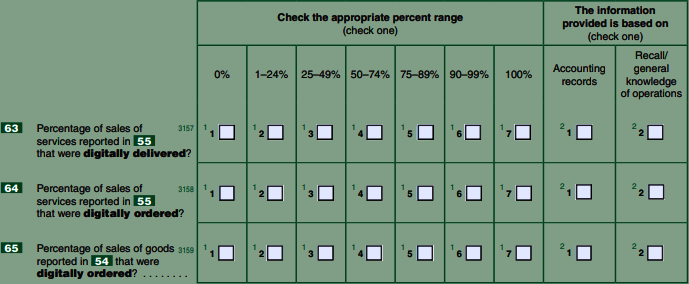

A similar process has also occurred in the United States for the BEA’s survey of direct investment abroad. Unlike the ONS, the BEA took the approach of asking for a percentile range of sales that were digitally ordered or delivered (see Box 3.6). This was designed to re-assure respondents that estimates are acceptable if the required detailed information is not available. Furthermore, since the construction of the Digital SUTs is a re-allocation of existing estimates, rather than a compilation from scratch (a theme that will be repeated throughout this handbook), percentiles of sales that provide an indication of the level of digital ordering and delivery is sufficient to inform the breakdowns of product rows.

Box 3.6. New questions in the Benchmark Survey of United States Direct Investment Abroad

The BEA’s most recent benchmark survey1 of direct investment abroad, covering direct investment abroad and foreign direct investment in the United States by multinational enterprises (MNEs), was in 2019. Due to the interest in measuring the digital economy, the 2019 benchmark survey included a special section on digital activities on each of the MNE parent (“A”) forms and the MNE foreign affiliate (“B”) forms, including questions about digitally ordered and digitally delivered sales. The new questions closely followed the definitions in the first edition of the OECD’s Handbook on Measuring Digital Trade (OECD, WTO and IMF, 2020[12]).2

The survey asked about the percentage of goods and services sales that were digitally ordered and the percentage of services sales that were digitally delivered. Digital ordering was defined as relating to “sales conducted over computer networks by methods specifically designed for the purpose of receiving or placing orders, negotiating terms of sales or price”. Digitally delivered services were defined as “those that are delivered remotely over information and communications technology networks”. The percentages were collected using checkboxes corresponding to ranges, as shown below.

1. The BEA’s two broad survey programs collect data on 1) trade in services, and 2) direct investment and activities of MNEs. The latter of these programs covers direct investment abroad and foreign direct investment in the United States and consists of mandatory quarterly, annual, and benchmark surveys. Benchmark surveys are censuses conducted once every five years that typically cover a broader range of data items than the annual surveys. For example, they may collect more underlying detail on standard financial statement items or may cover special topics.

2. The full survey forms for United States parents and foreign affiliates can be found on the BEA website.

United States MNE parents are key digital sellers. Therefore, these new survey questions should help providing valuable information for the Digital SUTs on digital ordering of goods and services and digitally delivered services in the United States.

The producer or buyer perspective

National statistical offices are also able to gather relevant information from the other side of the transaction: the people who purchase or receive products digitally. Whereas aggregate information is often obtained from the supply side, product-level information is usually best sourced from the consumer. The household sector is not the only consumer of goods and services ordered digitally, but it is to households that statistical offices most often turn in order to collect additional product level information on e-commerce.

Statistics Canada undertakes the Canadian Internet Use Survey (CIUS) (Statistics Canada, 2021[57]), a specific household survey focusing on how the household sector accesses and uses the internet. While part of the survey, such as the ability to access the internet or average length of time spent online, is not relevant for compiling the Digital SUTs, there is a range of potentially useful outputs from the survey. These include information on the prevalence of online shopping, the amounts and products purchased, as well as whether the purchase was part of a subscription or just one-off. Having this survey in place prior to the COVID-19 pandemic meant that Statistics Canada was able to show how digital ordering had significantly changed due to lockdowns and other COVID-19 related policies (Statistics Canada, 2021[58])

Statistics Sweden has used household surveys to obtain information on the frequency and intensity of digital ordering. Importantly, they have also asked about the products that are being purchased online, allowing for the publication of 24 different product categories (Table 3.5).9

Table 3.5. Proportion of online purchases, Sweden, 2021

|

Goods/services bought/ordered via the Internet, by type of goods/service (% of people purchasing) |

2021 |

|---|---|

|

Clothes |

53 |

|

Medicine |

34 |

|

Furniture, home accessories or garden products |

28 |

|

Cosmetics, beauty or wellness products |

27 |

|

Sports goods |

24 |

|

Deliveries from restaurants, fast-food chains, catering services |

23 |

|

Physical goods from a private individual |

23 |

|

Food or beverages from stores or meal-kit providers |

22 |

|

Printed books, magazines or newspapers |

21 |

|

Other physical goods |

20 |

|

Computers, tablets, mobile phones or accessories |

18 |

|

Consumer electronics or household appliances |

16 |

|

Cleaning products or personal hygiene products |

16 |

|

Mobile phone or internet subscriptions |

15 |

|

Children´s toys and childcare items |

13 |

|

Bicycles, mopeds, cars, or other vehicles |

9 |

|

Insurance policies |

9 |

|

Electricity, water or heating subscriptions |

8 |

|

Household services |

5 |

|

Films or series such as DVDs, Blu-ray |

3 |

|

Tickets to cultural or other events |

3 |

Source: (Statistics Sweden, 2022[59]).

Household surveys offer a level of detail that can be used to break up rows and columns to provide more granular information than is possible from broad-based business surveys. Some categories may need to be combined or used for multiple product rows, as with other indicators on the nature of the transaction. However, they provide a good starting point that allows for preliminary estimates to be created and compared with other source data.

Treatment of digitally ordered retail margins

Most of the source data listed in this chapter has focused on digital ordering or e-commerce associated with the retail industry. However, in the SUTs, the outputs of the retail and wholesale industries cover only their margin activity and not the value of their gross sales. The products being distributed are treated instead as directly purchased by consumers from the industries producing them or from non-residents as imports.

The SUTs’ treatment of margins presents challenges for tracking the value of digitally ordered sales and purchases. The first is a lack of information: often while the compiler knows the nature of the final transaction, they may not know how the transaction between producer and retailer occurred. Even if this information is known, because the purchase of a product is only shown on one product row and even if a retailer has added value to it, a decision on how to reflect the two transactions in a single row is required. An assumption may be required, such as treating the final transaction nature as the nature for the entire production process in order to maintain the supply-use equilibrium at both the aggregate and the digitally ordered (and non-digitally ordered) level. While this solution is pragmatic, it may artificially inflate the level of output listed as digitally ordered. The alternative is to try and split the single transaction and show only the retail margin as digitally ordered, and the non-retail components as non-digitally ordered. Not only would this be very difficult to achieve; it would also alter the existing treatment of retail margins in the conventional SUTs.

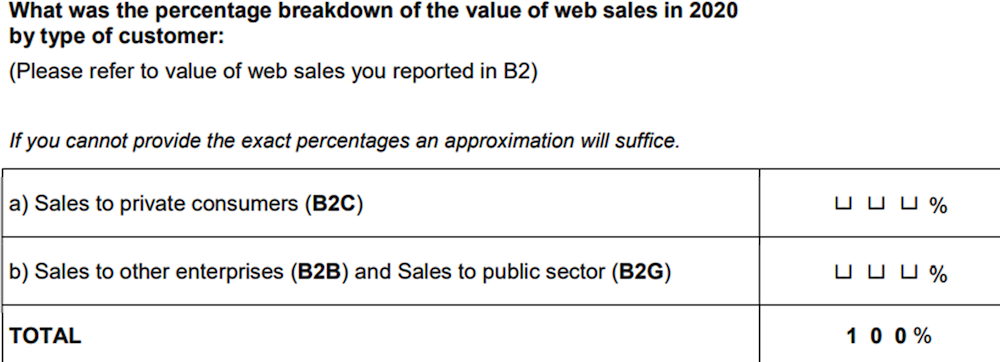

A different presentation, adopted in the Canadian Digital SUTs, shows the full value of digitally ordered purchases from distributors. However, the equivalent supply of the non-margin value allocated to domestic industries producing the products is shown under “Digitally ordered via a resident retailer or wholesaler” to separately track these activities (Table 3.6). Box 3.7 provides a more detailed explanation of the options available and Figure 3.7 shows a numerical example.

Table 3.6. Digital supply table, Canada, 2019

|

Nature of the transaction |

Output, all industries Million Canadian dollars |

|---|---|

|

Total |

4,065,386 |

|

Digitally ordered |

277,933 |

|

218,757 |

|

1,193 |

|

3,839 |

|

Via a resident retailer or wholesaler |

54,144 |

|

Not digitally ordered |

3,787,453 |

Source: (Statistics Canada, 2021[29]).

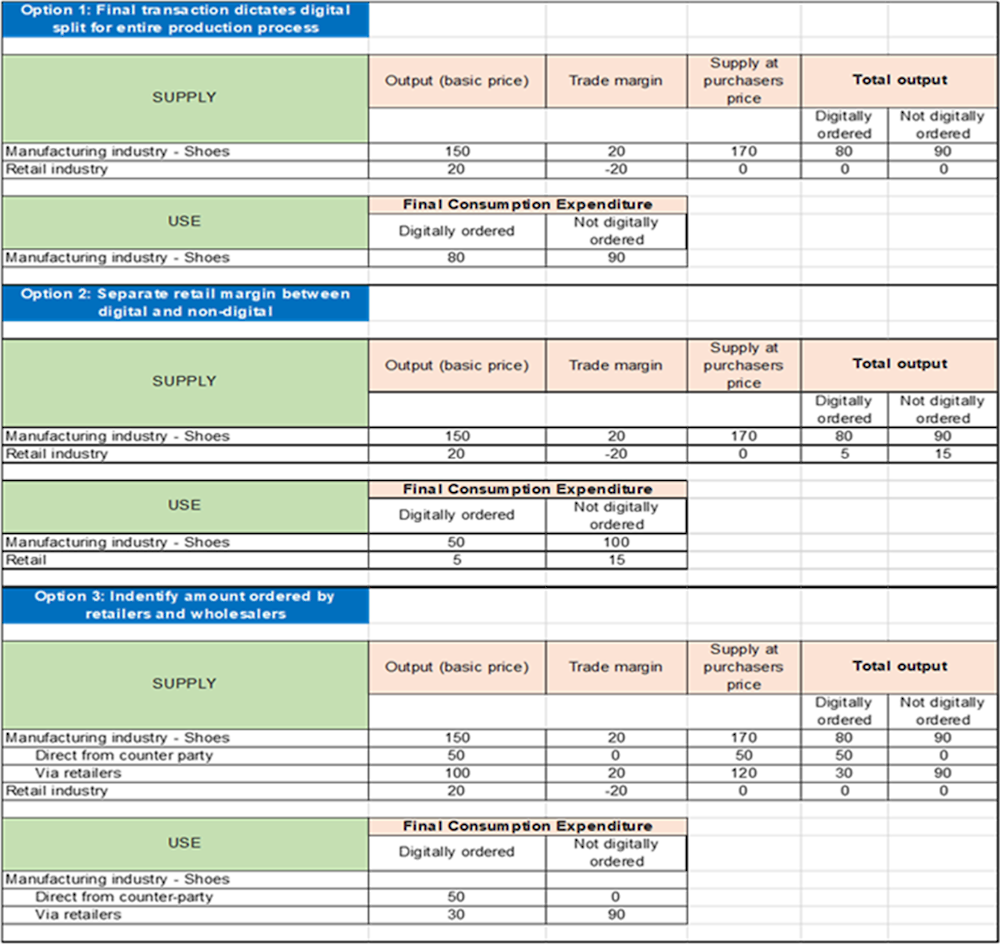

Box 3.7. The recording of digital ordering involving retail margins

To Illustrate the different options available to compilers for recording digital ordering involving retailers and wholesalers, Figure 3.7 displays the three recording treatments proposed. Since the high priority indicators focus on expenditure split by the nature of the transaction for household consumption, it is considered useful to specifically address the different recording options involving retailers.

In the example shown, the manufacturing industry produces $150 worth of shoes; $50 worth of these shoes are sold direct to the consumer through digitally ordering, $100 worth of these shoes are sold to a retailer, who resells at $120, thereby adding a retail margin of $20. Of the shoes sold via the retailer, 25% or $30 are sold via digital ordering.

Option 1 sees the nature of the final transaction as dictating the digital/non-digital split for the entire production process. The digital ordering of $50 direct to the producer as well as the $30 to the retailer are considered as digital ordering. This approach ignores the nature of the transaction between the producer and the retailer resulting in total digital ordering worth $80 and non-digital ordering worth $90. If information on the nature of the transaction is taken from household surveys, then this would appear the most likely treatment as data from households is usually provided for the value of the entire purchase not just the retail component. Since the digital/non-digital split on the supply side must equal that on the use side, the final consumption expenditure of shoes on the use table shares the $80/$90 digital/non-digital split. It could be argued that this overstates the value of digitally ordering in the economy as the it implies that every transaction in the production process mirrors the nature of the final transaction.

Option 2 attempts to break up the value of the product between the retail margin and non-margin components. This would allow for the value of the product to be applied appropriately while separately recording the digital/non-digital split as it pertains to the retail margin. Not only would this information be incredibly difficult to assign to many different products flowing through retailers, it would also go against the fundamental SUT framework where the output of the retail industry is considered a margin and added to the price of the existing product rather than being consumed directly. For this reason, this option is not recommended.

Option 3 represents the alternative undertaken by Statistics Canada in their representation of the Digital SUTs. It builds on Option 1, but rather than automatically representing the value digitally ordered via the retailer as equal to the directly digitally ordered component, it sees the supply (and the subsequent consumption) as being done via a retailer. While the overall output and consumption split is still the same as Option 1 at $80-digital, $90-non-digital, $30 of this value is clearly shown to have be done via a retailer. This can signal to the reader that the digital/non-digital splits for prior transactions in this processing chain are unknown, unlike in the case of Option 1 where $50 was directly digitally ordered from the producer.

The choice between Option 1 and Option 3 will probably depend on different factors including source data availability, the level of B2B and B2C digital ordering and user preference. While Option 3 provides additional information to the users, not every B2B transaction is able to be fully represented in the production process of every product.

Figure 3.7. Numerical example of recording options for retail margins

Source: The authors.

Option 3 provides greater insight into whether the expenditure is definitively digitally ordered or potentially digitally ordered. While it does create an extra row and thus extra calculations, it would appear easier to implement such a solution than trying to divide the gross purchase into a retail and non-retail components. It is also more consistent with the existing SUT treatment. It is therefore seen as a useful approach that could be considered by countries, especially for the rows containing aggregates and totals.

Conclusion

This chapter has looked at the nature of the transaction, which is the foundation of the Digital SUTs. It includes the differentiation of the supply and use of products based on how the product is ordered, and the separation of totals - such as final consumption and imports – into the parts that are digitally delivered and the part that are not.

Such breakdowns are of interest to policy makers because they show which products are experiencing the largest disruptions in the producer-consumer paradigm as the importance of the digital economy grows. They may also provide an indication of which economic activities might relocate across borders if service delivery became fully digital (not physical).

Compilation challenges such as a lack of data on digitally delivered services and digitally ordered estimates at the product level, still exist; but many countries already have some data available. On top of the data already available, several countries have undertaken steps to develop source data in this area. The success of these efforts should be monitored so that other countries can replicate success stories and learn from initial challenges as faced by some countries.

Annex 3.A. List of products considered digitally deliverable

Annex Table 3.A.1. List of products considered digitally deliverable

|

CPC 2.1 product codes |

CPC 2.1 Products |

|---|---|

|

611 |

Wholesale trade services, except on a fee or contract basis |

|

A612 |

Wholesale trade services on a fee or contract basis |

|

621 |

Non-specialised store retail trade services |

|

622 |

Specialised store retail trade services |

|

623 |

Mail order or internet retail trade services |

|

624 |

Other non-store retail trade services |

|

625 |

Retail trade services on a fee or contract basis |

|

69112 |

Electricity distribution (on own account) |

|

692 |

Water distribution (on own account) |

|

7111 |

Central Banking services |

|

7112 |

Deposit services |

|

7113 |

Credit-granting services |

|

7114 |

Financial leasing services |

|

7119 |

Other financial services, except investment banking, insurance services and pension services |

|

712 |

Investment banking services |

|

71311 |

Life insurance services |

|

71312 |

Individual pension services |

|

71313 |

Group pension services |

|

7132 |

Accident and health insurance services |

|

71331 |

Motor vehicle insurance services |

|

71332 |

Marine, aviation and other transport insurance services |

|

71333 |

Freight insurance services |

|

71334 |

Other property insurance services |

|

71335 |

General liability insurance services |

|

71336 |

Credit and surety insurance services |

|

71337 |

Travel insurance services |

|

71339 |

Other non-life insurance services |

|

714 |

Reinsurance services |

|

715 |

Services auxiliary to financial services other than to insurance and pensions |

|

7161 |

Insurance brokerage and agency services |

|

7162 |

Insurance claims adjustment services |

|

7163 |

Actuarial services |

|

7164 |

Pension fund management services |

|

7169 |

Other services auxiliary to insurance and pensions |

|

717 |

Services of holding financial assets |

|

7212 |

Trade services of buildings |

|

722 |

Real estate services on a fee or contract basis |

|

73220 |

Leasing or rental services concerning video tapes and disks |

|

73311 |

Licensing services for the right to use computer software |

|

73312 |

Licensing services for the right to use databases |

|

7332 |

Licensing services for the right to use entertainment, literary or artistic originals |

|

7333 |

Licensing services for the right to use R&D products |

|

73340 |

Licensing services for the right to use trademarks and franchises |

|

7335 |

Licensing services for the right to use mineral exploration and evaluation |

|

7339 |

Licensing services for the right to use other intellectual property products |

|

811 |

Research and experimental development services in natural sciences and engineering |

|

812 |

Research and experimental development services in social sciences and humanities |

|

813 |

Interdisciplinary research and experimental development services |

|

814 |

Research and development originals |

|

821 |

Legal services |

|

822 |

Accounting, auditing and bookkeeping services |

|

823 |

Tax consultancy and preparation services |

|

824 |

Insolvency and receivership services |

|

8311 |

Management consulting and management services |

|

8312 |

Business consulting services |

|

8313 |

IT consulting and support services |

|

83141 |

IT design and development services for applications |

|

83142 |

IT design and development services for networks and systems |

|

83143 |

Software originals |

|

8315 |

Hosting and IT infrastructure provisioning services |

|

8316 |

IT infrastructure and network management services |

|

8319 |

Other management services, except construction project management services |

|

832 |

Architectural services, urban and land planning and landscape architectural services |

|

833 |

Engineering services |

|

8342 |

Surface surveying and map-making services |

|

8343 |

Weather forecasting and meteorological services |

|

8344 |

Technical testing and analysis services |

|

836 |

Advertising services and provision of advertising space or time |

|

837 |

Market research and public opinion polling services |

|

83811 |

Portrait photography services |

|

83812 |

Advertising and related photography services |

|

83814 |

Specialty photography services |

|

83815 |

Restoration and retouching services of photography |

|

83815 |

Restoration and retouching services of photography |

|

83819 |

Other photography services |

|

8382 |

Photographic processing services |

|

83911 |

Interior design services |

|

83912 |

Industrial design services |

|

83919 |

Other specialty design services |

|

8392 |

Design originals |

|

8393 |

Scientific and technical consulting services n.e.c. |

|

8394 |

Original compilations of facts/information |

|

8395 |

Translation and interpretation services |

|

8396 |

Trademarks and franchises |

|

8399 |

All other professional, technical and business services, n.e.c. |

|

8399 |

All other professional, technical and business services, n.e.c. |

|

841 |

Telephony and other telecommunications services |

|

842 |

Internet telecommunications services |

|

84311 |

On-line books |

|

84312 |

On-line newspapers and periodicals |

|

84313 |

On-line directories and mailing lists |

|

8432 |

On-line audio content |

|

8433 |

On-line video content |

|

8434 |

Software downloads |

|

84391 |

On-line games |

|

84392 |

On-line software |

|

84393 |

On-line adult content |

|

84394 |

Web search portal content |

|

84399 |

Other on-line content n.e.c. |

|

844 |

News agency services |

|

845 |

Library and archive services |

|

8461 |

Radio and television broadcast originals |

|

8462 |

Radio and television channel programmes |

|

84631 |

Broadcasting services |

|

84632 |

Home programme distribution services, basic programming package |

|

84633 |

Home programme distribution services, discretionary programming package |

|

84634 |

Home programme distribution services, pay-per-view |

|

851 |

Employment services |

|

8521 |

Investigationservices |

|

8522 |

Security consulting services |

|

855 |

Travel arrangements, tour operator and related services |

|

8591 |

Credit reporting services |

|

8592 |

Collection agency services |

|

8593 |

Telephone-based support services |

|

8594 |

Combined office administrative services |

|

8595 |

Specialised office support services |

|

8596 |

Convention and trade show assistance and organization services |

|

8599 |

Other information and support services n.e.c. |

|

86312 |

Support services to electricity distribution |

|

8713 |

Maintenance and repair services of computers and peripheral equipment |

|

891 |

Publishing, printing and reproduction services |

|

921 |

Pre-primary education services |

|

922 |

Primary education services |

|

923 |

Secondary education services |

|

924 |

Post-secondary non-tertiary education services |

|

925 |

Tertiary education services |

|

92911 |

Cultural education services |

|

92912 |

Sports and recreation education services |

|

92919 |

Other education and training services, n.e.c. |

|

92919 |

Other education and training services, n.e.c |

|

9292 |

Educational support services |

|

931 |

Human health services |

|

961 |

Audiovisual and related services |

|

963 |

Services of performing and other artists |

|

96511 |

Sports and recreational sports event promotion services |

|

969 |

Other amusement and recreational services |

|

96921 |

On-line gambling services |

Source: Adapted from (IMF, OECD, UNCTAD, WTO, 2023[13]).

Annex 3.B. Digital trade framework and the Handbook on Measuring Digital Trade

The framework for measuring digital trade

Over the last twenty years, a number of measurement initiatives have emerged in the area of digital trade, including the work of OECD and the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) on defining and measuring e‑commerce, UNCTAD’s work on ICT-enabled trade and the OECD’s Going Digital Project (OECD, 2023[60]). On the policy front, the World Trade Organisation (WTO)’s Work Programme on Electronic Commerce, established in 1998, defines e-commerce as the "production, distribution, marketing, sale or delivery of goods and services by electronic means” (WTO, 1998[61]). More recently, the work of López‑González and Jouanjean (López González and Jouanjean, 2017[62]) proposed a framework for digital trade for trade policy analysis, in which all digitally enabled transactions are considered to be in scope for digital trade.

The first edition of the Handbook on Measuring Digital Trade (OECD, WTO and IMF, 2019) formalised for the first time a statistical definition of digital trade, combining the two key criteria of digital ordering and digital delivery: “digital trade is all international trade that is digitally ordered and/or digitally delivered”. This statistical definition reflects the multidimensional character of digital trade by identifying the nature of the transaction as its defining characteristic. It is the basic building block of a conceptual measurement framework, which is fully consistent with macroeconomic accounts.

The nature of the transaction – digitally ordered and/or digitally delivered – is the overarching defining characteristic of digital trade, i.e. it is how the transaction is conducted that determines the scope of digital trade. However, the framework also includes two other dimensions crucial for trade policy purposes: the product dimension (what is traded) and the actors engaged in digital trade (who is trading). The second edition of the Handbook on Measuring Digital Trade (IMF, OECD, UNCTAD, WTO, 2023[13])provides clarifications to the concepts and definitions introduced in the first edition, and to the guidelines on how to operationalise them. It also builds on national experiences and best practices to expand compilation guidance.

Digital trade transactions are a subset of existing trade transactions, as measured in international merchandise trade statistics and in international trade in services statistics. Any economic actor can engage in digital trade. The accounting principles for recording digital trade follow those defined in the International Merchandise Trade Statistics Concepts and Definitions (United Nations, 2011[63]), the Manual on Statistics of International Trade in Services (United Nations et al, 2010[64]) and the Balance of Payments (IMF, 2009[65]). Although international trade statistics should, in principle, cover digital trade, digital ordering and delivery, some of the known measurement challenges involved in recording international transactions are exacerbated in the case of digital trade. One reason is that digitalization increases the involvement of small firms and households in international trade, and this involvement may not be adequately covered by traditional data sources, which are often reliant on large firms. Also the rise in digital ordering has led to an increase in low-value trade in goods, which may elude methods of tracking merchandise trade based on value thresholds. For some transactions, the involvement of digital intermediation platforms (DIPs) compounds the difficulties by adding a third party.

To overcome these challenges, it is necessary to reconsider the existing data sources in terms of their coverage and accuracy, not only to develop digital trade statistics, but also to improve the measurement of international trade in general. The Handbook on Measuring Digital Trade recommends building on and combining existing data sources with a view to producing comprehensive digital trade statistics.

Digital trade concepts

In line with the OECD definition of e-commerce (OECD, 2011), digitally ordered trade is defined in the Handbook on Measuring Digital Trade as “the international sale or purchase of a good or service, conducted over computer networks by methods specifically designed for the purpose of receiving or placing orders”. Digitally ordered trade is therefore synonymous with international e-commerce and covers transactions in both goods and services.

Digitally delivered trade is defined in the handbook as “all international trade transactions that are delivered remotely over computer networks”. The handbook takes the view that only services can be digitally delivered. Unlike digital ordering, which is instantaneous, digital delivery can take place over a longer period and can involve a significant degree of inter-personal interaction. Crucial to the definition is that such interaction occurs remotely through computer networks.

DIPs are defined in the handbook as “online interfaces that facilitate, for a fee, the direct interaction between multiple buyers and multiple sellers, without the platform taking economic ownership of the goods or rendering the services that are being sold (intermediated)”. The service provided by DIPs is that of “matching” buyers with sellers and thus facilitating the exchange of goods or the provision of services. These digital intermediation services (DIS), which are, by definition, both digitally ordered and digitally delivered, are defined as “online intermediation services that facilitate transactions between multiple buyers and multiple sellers in exchange for a fee, without the online intermediation unit taking economic ownership of the goods or rendering the services that are being sold (intermediated)”.

To record transactions facilitated by DIPs, it is necessary to distinguish the supply of goods or services (i.e. the transaction between the seller and the buyer) from the provision of intermediation services (i.e. the transaction between the DIP and both the seller and the buyer). Regardless of whether a given DIP facilitates transactions in goods or services, the intermediation fees should be recorded under trade-related services in the international accounts.

Reporting digital trade transactions

The Handbook on Measuring Digital Trade proposes a reporting template which supports the compilation of the two components of digital trade – digitally ordered trade and digitally delivered trade – as well as the calculation of total digital trade. The template allows the different components to be measured in the way that best suits the compiler, even when only partial information is available.

Annex Table 3.B.1. Reporting template for digital trade

|

Item |

|

Total exports |

Total imports |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Total digital trade |

2+3 minus 4 |

||

|

2 |

Digitally ordered trade |

2.1+2.2 |

||

|

2.1 |

Goods |

|||

|

2.1.a |