Beyond its human toll, Russia’s war of aggression in Ukraine has also profoundly affected regional and global trade patterns, disrupted global supply-chains, and transformed trade routes. The Northern Route, bringing goods from China to Europe through Russia, has seen a significant reduction in traffic following international sanctions. Traffic shifted to the Middle Corridor route, also referred to as the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route (TITR). If the route received renewed political attention to develop it into an alternative transit corridor, its multimodal nature puts it at a structural disadvantage compared to other routes. Building the Middle Corridor’s potential and overcoming its lack of competitiveness lies in its ability to become a trade route fostering economic and regional integration within Central Asia and the South Caucasus, as well as between these regions, Asia, and Europe.

Realising the Potential of the Middle Corridor

1. The Context: Growing interest in the Middle Corridor

Abstract

This chapter sets the stage for the rest of the report. The introduction section defines the Middle Corridor and the Northern Corridor and explains in which context the latter has been affected by disruptions that bring attention to the former. Then, the first section details the trade opportunities that could support demand along the Middle Corridor. The second section explains the challenges that the countries of the corridor must face in order to enhance the route’s competitiveness and create a viable alternative to the Norther Corridor. The last section recalls the key issues identified in terms of trade for Central Asia and the South Caucasus and delivers an overview of the report’s recommendations.

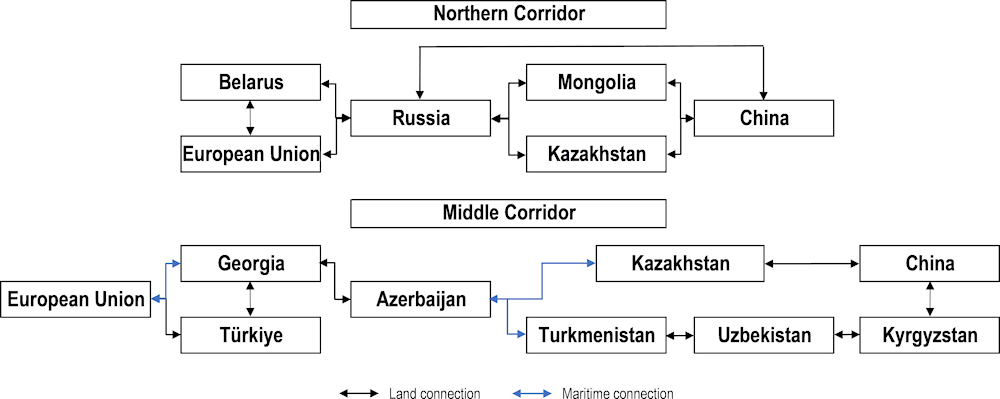

Until February 2022, the Eurasian Land Bridge Economic Corridor, also known as the “Northern Route”, was the most-used overland freight route between China and Europe. Transiting through Kazakhstan, Mongolia, Russia and Belarus, the corridor had been gradually streamlining cross-border trade, modernising rail infrastructure and easing trade procedures along 12,000km of railroad (Box 1.1 and Figure 1.1). Since 2011, the Northern Route has gradually become the fastest non-air freight connection between China and Europe among the different routes available (Table 1.1).

Table 1.1. Cost and time estimates for main EU-China corridors in 2020

Per 40-foot container, from Chengdu, China

|

Cost range (USD) |

Average time (days) |

Northern Europe time (days) |

Central Europe time (days) |

Balkans time (days) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Northern Route |

2,800 – 3,200 |

14 – 18 |

16 |

15 – 16 |

20 |

|

Middle Corridor |

3,500 – 4,500 |

16 – 20 |

18 |

17 |

14 |

|

Maritime Route |

1,500 – 2,000 |

28 – 40 |

28 – 40 |

28 – 40 |

28 – 40 |

Source: (World Bank, 2020[1])

Since Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, international sanctions have increased the cost of shipping cargo along the Northern Route. Ensuing logistics disruptions have affected almost all trade flows between Russia and Europe, causing significant delays and global freight price increases. As a result, container shipping between the European Union (EU) and China through Russia is estimated to have decreased by at least 35% (Index, 2023[2]).

Figure 1.1. Northern and Middle Corridor schematic routes

Source: OECD analysis (2023)

Box 1.1. The Eurasian Land Bridge Economic Corridor (or Northern Route)

The Eurasian Land Bridge is a rail transport corridor comprising two main overland rail routes: the Trans-Siberian Railway and the New Eurasian Land Bridge. It represents the main overland route connecting China and the EU and carries approximately 3% of total China-Europe container trade.

The Trans-Siberian Railway

Completed in 1916, the Trans-Siberian Railway is a 9,200km-long line from Vladivostok to the EU, with access to Russian Pacific ports and the North-East region of China. This line can handle up to 200,000 TEU of containerised international transit freight per year.

The New Eurasian Land Bridge

As the southern part of the route, the New Eurasian Land Bridge runs through China and Kazakhstan, before crossing into Russia and reaching the EU. This section is more recent; the first segments were completed during the second half of the 20th century. From Kazakhstan, two North-South railways connect with the Trans-Siberian while another segment goes directly to Western Russia.

Operational connectivity issues remain

While the Eurasian Land Bridge is a network of uninterrupted railways connecting a whole continent, operational challenges hamper the efficiency of the route. Since the different segments of the route were established in different countries at different times, technical barriers exist regarding the length of fleets and trains, and railway electricity infrastructure. Moreover, due to the complexity of documentation requirements, there are risks and costs related to administrative rules and customs clearance procedures, which increase transit time.

Source: (World Bank, 2022[3]; UNESCAP, 2022[4]).

Central Asia, the South Caucasus and Türkiye can play a central role in intensifying regional co-operation and opening new trade routes

Türkiye represents a central East-West and North-South trade hub

Türkiye is located at the crossroads of Europe and Asia, granting access to the Middle East, North Africa, the South Caucasus, the Balkans, and Central Asia. The Turkish Straits, two crucial international waterways that connect the Mediterranean and the Black Sea, make Türkiye an important player in maritime trade, most recently showcased by the Black Sea Grain Corridor Initiative that facilitated the transport of Ukrainian grain to international markets. Türkiye is situated on transport corridors between Europe and Asia, including the Middle Corridor, the Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T), and TRACECA, as well as energy corridors from the Middle East and Caspian to Europe, which render it significant for local and regional trade activities. This strategic location combined with progress in road, port, airport, and railway infrastructure investments has helped improve inland and cross-border connectivity. Advances in trade facilitation via simplification and digitalisation of customs procedures and multiple bilateral and multilateral trade agreements have bolstered Türkiye’s position as a regional trade and logistics hub.

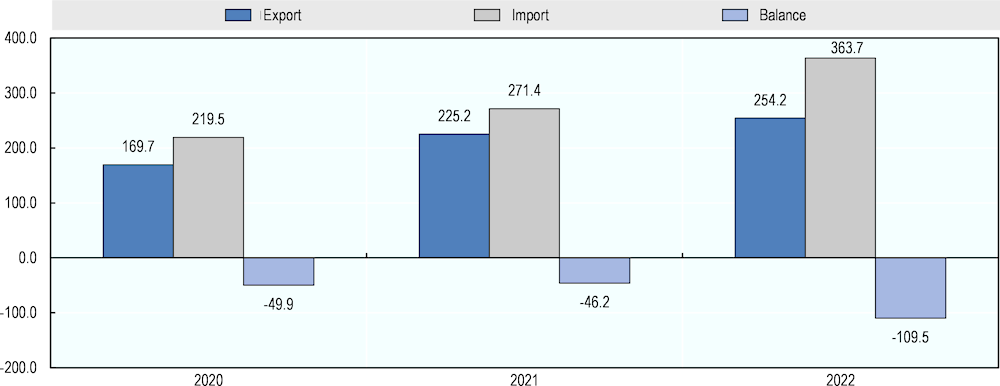

As an upper-middle income OECD and G20 country, Türkiye is a significant player in regional merchandise and services trade. In 2022, it ranked as the 19th largest economy globally, with a GDP of USD 906 billion. That year it ranked 30th in exports and 19th in imports globally, with a trade volume of USD 618 billion. The EU is Türkiye’s largest trading partner, amounting to 40.5% of total exports and 25.6% of total imports, with a coverage ratio of 110.5%. Türkiye is the 5th largest exporter and 7th largest importer in Extra-EU trade. The Customs Union (CU) established in 1995 has been a significant driver of transformation in Türkiye’s policy environment, including trade policy, helping the country advance in global value chains and diversify its portfolio from traditional exports of agrifood and textiles towards electrical equipment, machinery, chemicals, and motor vehicles.

In addition to the EU, Türkiye also maintains strong trade ties with other neighbouring regions It is among the top five trade partners for the South Caucasus and Central Asian countries except for Armenia, being the largest source of imports for Georgia and Turkmenistan, and the second largest for Azerbaijan in 2022. Whereas Türkiye predominantly imports fuels and minerals from the region, it exports machinery, electronic equipment, textiles and plastic. Türkiye is also active in the neighbouring regions through services trade, most notably through overseas contracting services, which is a highly competitive sector with 42 Turkish companies ranking among top 250 firms globally, second only to China. In 2022, Turkish companies contracted USD 19.1 billion worth of projects in Commonwealth of Independent States (USD 7.1 billion, 37.2%), Europe (USD 4.9 billion, 26.0%), Middle East (USD 3.4 billion, 18.0%), and Africa (USD 3.3 billion, 17.1%) predominantly in housing (USD 4.36 billion, 22.8%) and road-tunnel-bridge infrastructure (USD 4.30 billion, 22.5%) (Ministry of Trade of the Republic of Türkiye, 2023b[5]).

Figure 1.2. Türkiye’s merchandise trade profile (2020-2022)

Central Asia and the South Caucasus could benefit from a possible shift in China’s regional trade and transit strategy

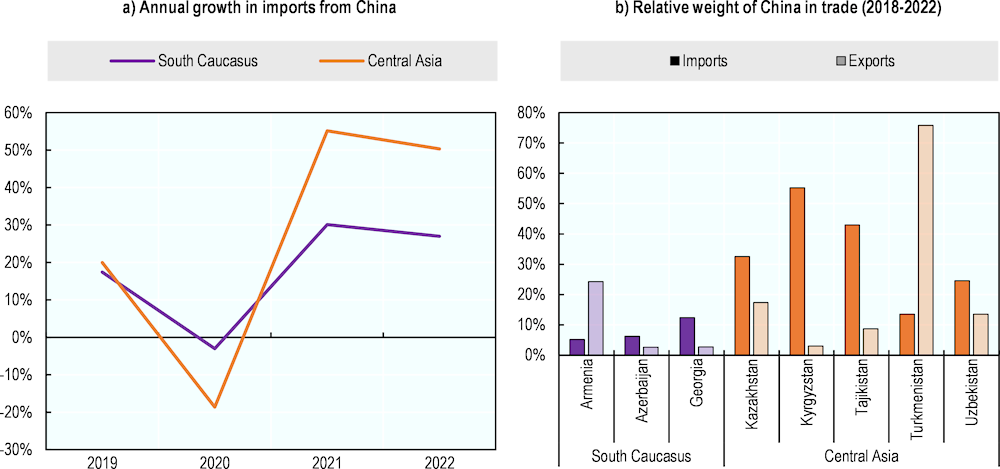

In recent years, China has become a major trading partner and an important financing source for Central Asia and the South Caucasus. China has become a major source of imports for all Central Asian countries except Turkmenistan, as well as for Azerbaijan and Georgia, albeit to a lesser extent than for Central Asia (Figure 1.3) (OECD, 2023[7]; OECD, 2022[8]). Room for expanded export opportunities exists, in particular for non-energy related commodities, as energy and mineral resources constitute the bulk of both regions’ exports to China. For instance, Kazakhstan’s exports to China are dominated by crude oil and petroleum gas, while metals represent the largest share for Georgia, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan (UNCTAD STAT, 2022[9]).

Central Asia and the South Caucasus have grown in importance in China’s trade and transit strategy to Europe. Over the past decade China has deepened its political and financial presence in Central Asia, especially with the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Throughout 2022 and early 2023, high-level political co-operation between China and Central Asia has deepened, aiming to increase trade turnover and investments in particular. The joint China-Central Asia summit in January 2022 called for a doubling of bilateral trade turnover by the end of the decade and for increased Chinese investment in the region, while the May 2023 presidential Xi’an Summit showcased China’s development plans for the region. Recent investments have notably expanded beyond energy supply and transport infrastructure, as discussions are on-going to open the Chinese consumer market to Central Asia’s food exports. For instance, Chinese President Xi Jinping announced in January 2022 that China would further open its market to Central Asian imports with the goal of increasing total China-Central Asia trade turnover to USD 70 billion by 2030 (OECD, 2022[8]; The State Council of the People's Republic of China, 2022[10]). China also has a strong trade transit perspective in South Caucasus economies, focusing efforts on the infrastructure and transportation sectors to develop a continuous transit corridor to Europe (World Bank, 2020[11]).

Figure 1.3. Trade dynamics between China and Central Asia and the South Caucasus (2018-2022)

The current disruptions to Chinese freight on the Northern Route could accelerate the shift in China’s regional trade and transit strategy in favour of Central Asia and the South Caucasus. The slowdown of Chinese cargo traffic on the Northern Route has already resulted in China’s increased interest in the development of the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route (TITR), also called the Middle Corridor. China committed to the further development of the corridor and the construction of transport and logistics hubs for China-Europe freight train services at the May 2023 China-Central-Asia summit in Xian. However, the growth of Chinese manufacturing and exports has slowed in recent years as a result of weaker global demand. If this slowdown were to persist, prospects for increased exports from Central Asia would look less promising in the medium-term (IMF, 2023[13]).

The Middle Corridor constitutes a promising alternative to the Northern route, but much remains to be done to realise its potential

The Middle Corridor is a viable, albeit complex, route connecting Asia to Europe through Central Asia and the South Caucasus

Since Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route, also called the Middle Corridor, has gained renewed attention from governments and firms as an alternative to the Northern Route. The route is a multi-modal transport network (road, containerised rail freight and ferry routes) connecting Asia to Europe via Kazakhstan, the Caspian Sea, Azerbaijan and Georgia before going on to Europe through the Black Sea and/or Türkiye. It is an alternative to the Northern Route and the various maritime routes between Europe and Asia, and also offers new opportunities for the enhancement of regional trade and the economic development of the countries along the route. The current Middle Corridor is a relatively recent trade route: the two major initiatives to strengthen it (Trans-Kazakhstan railroad, Baku-Tbilisi-Kars railway) were completed in 2014 and 2017, following the establishment of the Co-ordination Committee for the Development of the TITR. Hitherto, the Middle Corridor has carried far less traffic than the “Northern Route” through Russia and Belarus, but trade-disruptions following Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine triggered sharp growth along the route and much discussion of what could be done to develop it further (OECD, 2022[8]).

The route could offer the shortest alternative to the Northern Route for freight transport between Asia and Europe. Recent studies indicate that transporting goods from Chengdu through the Middle corridor would only take one additional day to Central Europe compared to the Northern Corridor, and two additional days to Northern Europe. The Middle Corridor even offers a competitive advantage for transit of goods between China and the Balkans, with a 6 days cut in transit time compared to the Northern Corridor. It is also the shortest route for trade from China or Central Asia to North Africa when considering the access to the Mediterranean Sea from Georgian and Turkish ports. Enhancing the TITR would potentially reduce transport costs and boost trade among the countries it traverses. Realising this potential would require not only significant infrastructure investment but also trade facilitation reforms (see below). The Corridor’s current capacity represents only a fraction (at most 5%) of that of the Northern Route (Rail Freight, 2022[14]; ITF, 2022[15]).

In 2022, cargo traffic on the Middle Corridor increased sharply, due to a shift away from the Northern route. The volume of cargo transportation along the route has increased by 2.5 times (albeit from a low baseline) to 1.5 million tons in 2022. The route also witnessed an estimated doubling of container shipments to 50,000 TEU containers (ITF, 2022[15]; Middle Corridor Association, 2022[16]). Cargo volumes crossing the Caspian followed the same dynamic. This evolution also creates new trade opportunities for the countries along the route. For instance, Kazakhstan’s share of cargo increased 6.5-fold compared to 2021, to about 900,000 tons. Container shipments across the Caspian Sea increased by 33%, reaching 33,600 twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs) containers, of which 18,000 are estimated to have transited along the whole Middle-Corridor (Port Aktau, 2023[17]; Adilet, 2022[18]). For the five first months of 2023, cargo traffic growth is estimated to be 64% compared to the same period in 2022, with 1 million tons transported (Prime Minister of the Republic of Kazakhstan, 2023[19]).

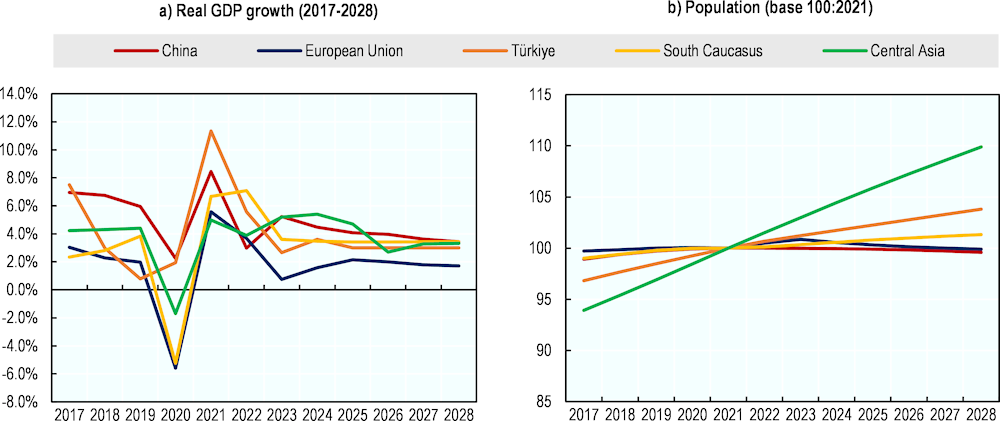

The route also offers a perspective for future trade and transit growth connecting Asia to Europe through quickly growing economies. Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Türkiye, as well as the other countries of Central Asia and the South Caucasus, are growing in terms of GDP and population (Figure 1.4). Kazakhstan offers a trade gateway to a market of about 100 million consumers around the Caspian Sea, including 76 million in Central Asia, as well as routes to Western China, Türkiye and the European Union (International Trade Administration, 2022[20]; Presidency of the Republic of Türkiye, 2023[21]). A recent EBRD study finds that transit container volume could increase from the current 18,000 TEUs to 130,000 TEUs by 2040 only attributable to population and GDP growth (EBRD, 2023[22]).

Figure 1.4. The Middle Corridor runs through and connects growing regions

Opportunities for trade growth will also expand to the extent that China evolves into a more consumption- (rather than export-) oriented economy and that the economies of Central Asia and the South Caucasus manage to move up along value chains. A shift towards more consumption-led growth in China would generate additional West-East Middle Corridor traffic and intensified trade ties with Central Asia and the South Caucasus. The development of manufacturing industries in Central Asia and the Southern Caucasus would lead to increased exports, while the production of higher value-added technological goods would boost imports of intermediate parts and components.

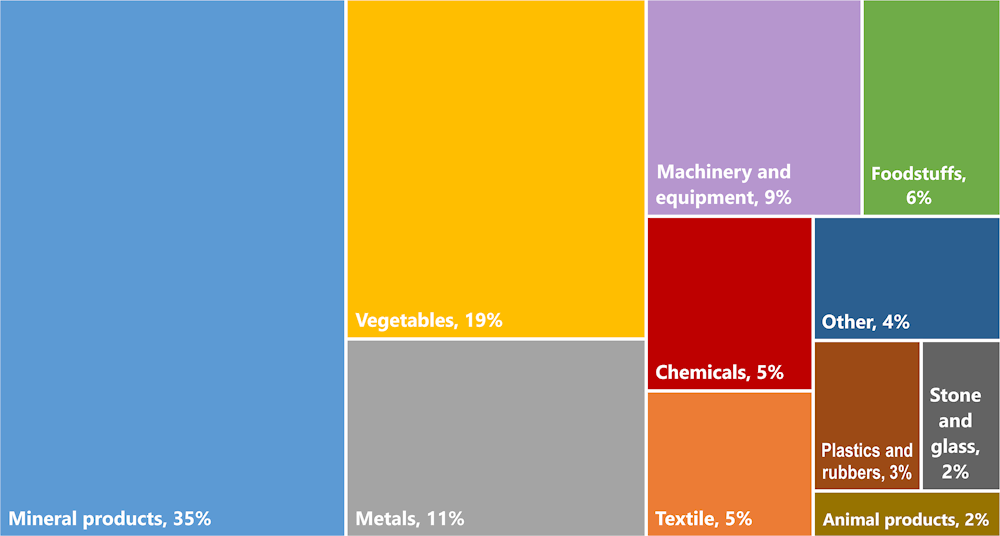

Figure 1.5. Composition of intra-regional trade in Central Asia and the South Caucasus (2017-2021)

Note: Categories of products respect the Harmonised Commodity Description and Coding System (HS). Regional trade accounted for 39.5 billion USD over the period. The figure includes exports from Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia to these same countries.

This report assesses challenges and identifies reform priorities in relation to infrastructure, trade facilitation and stakeholder co-ordination along the Middle-Corridor

The purpose of this report is to offer targeted advice to the governments of Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Georgia, and Türkiye on how to harness the potential of the Middle Corridor. In particular, the report complements recent work on the Corridor’s development potential by drawing on the perspectives of private sector actors to help map and sequence main reform and implementation priorities.

Drawing upon original data collected in each of the Middle Corridor countries (Box 1.2), the report includes an analysis of the main factors that hinder or contribute to the route’s development. In each project country, the OECD has consulted with representatives of the government, the private sector, and other development partners through a detailed online survey, complemented by qualitative in-depth interviews. Based on this analysis, the study assesses reform priorities in relation to infrastructure, trade facilitation and stakeholder co-ordination along the Middle-Corridor and suggests issue-specific recommendations to increase the countries’ trade and connectivity potential and at the regional level, to create the conditions for increased demand and traffic along the Middle Corridor.

Box 1.2. Realising the Trade Potential of the Middle-Corridor: methodology (2023)

The current report assesses bottlenecks and maps reform and implementation priorities in relation to (i) transport infrastructure, (ii) trade facilitation, and (iii) national and supra-national stakeholder co-ordination to develop the potential of the Middle Corridor as a central trade route connecting Asia to Europe. In particular, the report aims at highlighting the perspective of the private sector and key public-sector actors in Kazakhstan, Georgia, Azerbaijan and Türkiye to help map and sequence main reform and implementation priorities. The analysis also considers the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic and the disruption caused by Russia’s war in Ukraine on regional trade and integration to ground the analysis of the route’s development potential.

The study relied on two main dimensions:

(i) A series of qualitative online surveys building on the recent ITF Policy Brief (ITF, 2022[15]) focusing on trade facilitation, infrastructure development and national and supra-national stakeholder co-ordination in the four project countries.

(ii) A series of qualitative interviews with selected public and private stakeholders, as well as with IOs (EBRD, World Bank, etc.) active in the four project countries to broaden the perspective on the challenges and opportunities for realising the route.

The analytical work relied on a continuous dialogue between the OECD, the governments of Kazakhstan, Georgia, Azerbaijan and Türkiye, the private sector, and international partners, including through several bilateral consultations in the first half of 2023. In particular, the OECD has used a series of tools, including questionnaires, data requests and collection, analysis of surveys and interviews, to collect data and information.

The report focuses on the private sector’s perspective on the route to help policymakers map and sequence reform priorities. Accordingly, whilst many of the most important aspects of the route’s development are addressed in this report, some, such as the investment and fiscal challenges, are not. These are covered by other recent studies and remain important aspect to realising the Middle Corridor’s potential.

Note: The detail of the methodology is available in Annex A.

Source: OECD (2023).

Infrastructure bottlenecks and inadequate trade facilitation increase costs and transit times along the Middle Corridor

The Middle Corridor’s multimodal nature challenges its attractiveness from the private sector perspective. Private sector stakeholders consulted for this study (see below) emphasise the importance of cost, time, and safety factors in a route’s competitiveness. Currently, the Middle Corridor appears less competitive than alternatives, chiefly due to the unpredictability of transit times and higher costs arising from the large number of modal switches and international frontiers along the route (Eurasianet, 2022[26]; ADB, 2021[27]). These structural issues are further exacerbated by limited transport and logistical capacity, deficient infrastructure, gaps in the operational and trade facilitation environment, and inadequate regional, national, and supra-national stakeholder co-ordination (OECD, 2023[28]; OECD, 2023[29]; ADB, 2021[30]; USAID, 2022[31]; ITF, 2022[15]). As a result, despite intensifying trade and transit, and a positive outlook, the Middle Corridor does not yet provide a real alternative to the Northern Route (Rail Freight, 2022[14]).

Transit capacity constraints have been highlighted by the shift of traffic from the Northern Route throughout 2022. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has led to an uptick in Middle Corridor traffic, resulting in reduced transit capacities and a rise in cargo shipping and logistics prices. Capacity limitations have visibly manifested themselves through container shortages and a decrease in available Caspian Sea vessels that have been mobilised to service traffic stemming from Russian ports rather than servicing their usual itineraries. This can be explained by Russia seeking to adjust its import inflows through increased trade with the Southern Caucasus and exploring alternative North-South routes through Iran. Logistics service prices increased in 2022 following a rise in service costs along the Northern Route reverberating on other trade routes, as well as heightened risk-premia for goods originating from Russia’s neighbours. Prices have tended to fall back to their pre-war levels since then.

Turning the Middle Corridor into a robust transit and trade route will require addressing infrastructure, trade facilitation, and regional co-ordination bottlenecks in Central Asia, the South Caucasus, and Türkiye. Being both a land and sea route, the Middle Corridor requires a complex set of road, rail, and maritime infrastructures. Despite recent developments in Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Türkiye, two palpable regional integration barriers are insufficient infrastructure, especially multimodal schemes in ports, and disparities in the legal and regulatory frameworks governing trade and transit requirements across the route. As a result, bottlenecks at the main seaports and border points increase transit times by as much as 10-15 days due to congestion, reaching 20-30 days in some cases. For example, the Kazakh border rail gauge change can last from one to 10 days, followed by two to three days to discharge at the Baku Alat port, and finally two to 10 days’ waiting in Georgia’s Poti port (EBRD, 2022[32]). Addressing these issues will require a common approach to infrastructure and trade facilitation reforms at both the national and regional levels.

Limited regional trade and economic integration in Central Asia and the South Caucasus further reduce the route’s trade competitiveness

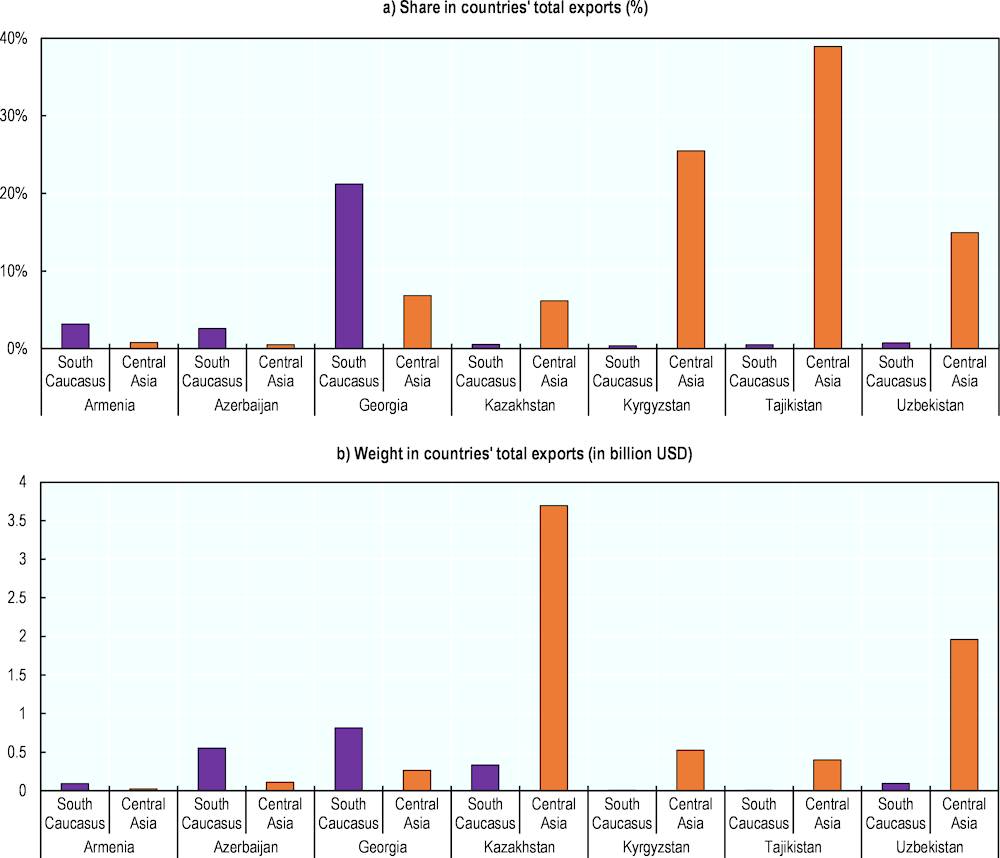

Regional trade represents only a small fraction of trade in Central Asia and the South Caucasus. Except for some of the smaller economies such as Georgia, Kyrgyzstan, or Tajikistan, regional exports represent a limited share of total exports. Exports to the region accounted for 15% of the total, on average, for Uzbekistan between 2017 and 2022; the corresponding figures for Kazakhstan (8%) and Armenia (2%) were even lower (Figure 1.6). This pattern largely reflects the commodity composition exports, which is strongly skewed towards mineral commodities, except in Georgia, which relies more on agricultural goods and some manufactures (OECD, 2020[33]). As a result, export destinations are highly concentrated, mainly in Europe, Russia, and China. Uzbekistan’s comparatively greater share of regional exports could be linked to its larger industrial base and the weight of agricultural goods in its export basket, leading to a more diversified trade partner portfolio (OECD, 2022[34]).

Trade between Central Asia and the South Caucasus is also limited. Trade with the neighbouring region accounts for an even smaller share of countries’ total exports (Figure 1.6), which can be indicative of the countries’ low integration in regional and global value chains. Indeed, manufacturing output in the South Caucasus countries and even more strikingly in Central Asia displays low levels of added value, reducing exports and requiring only small levels of foreign components as intermediate inputs (OECD, 2022[8]; OECD, 2023[7]). As a result, the Middle Corridor suffers from an attractiveness gap compared to other corridors transiting more economically integrated regions, providing for trade opportunities along the way.

Figure 1.6. Share of regional trade in countries of Central Asia and the South Caucasus

Note: “South Caucasus” refers to Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia; “Central Asia” covers Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. 2022 export data is missing for Tajikistan.

Source: (UN Comtrade, 2023[12]).

Unlocking the Potential of the Middle Corridor: Challenges, Opportunities, and Pathways Forward

Before the war, the Eurasian Land Bridge Economic Corridor (also known as the Northern corridor) was the most competitive route for rail shipment between China and Europe. Following Russia’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine, sanctions have brought logistic disruptions that hampered the corridor’s viability. Therefore, the Middle Corridor appears as a relevant alternative for the transit of goods across Eurasia, though its multimodal nature and multiple border crossings make it more challenging to develop.

The economies of the South Caucasus and Central Asia remain closely integrated with Russia, leaving them vulnerable to supply risks and secondary sanctions

Russia remains a predominant trade partner for Central Asia and the South Caucasus countries, both for imports, and exports and as a transit destination. These important ties are strengthened for some countries. by membership of the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU). Though the EAEU seeks to create a unified market, issues remain in terms of the harmonisation of tariffs. Due to the prevailing role of Russia in the EAEU, the organisation tends to favour Russia’s interests, and its operations can complicate trade relations with non-member countries (GIS, 2021[35]).

Trade in Central Asia and the South Caucasus was less affected than expected following the sanctions imposed on Russia in 2022. Russia is one of the main markets for the countries of the region, and its economic downturn could have affected exports. Instead, products from Central Asia and the South Caucasus appeared as substitutes for European products, and rising metals and hydrocarbon prices benefited countries like Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan.

However, the disruptions in trade with Russia are still likely to affect supply chains, and the conflict led to an increase in transport and logistics costs. Moreover, intermediate trade between Russia and third countries through Central Asia and the South Caucasus adds to the pressure on transport fees and exposes the region to secondary sanctions.

Countries along the corridor can foster regional co-operation and generate trade opportunities

At the western end of the route, Türkiye has a strong experience in developing as a logistics hub at the crossroads of continents and promoting integration to global markets. At the eastern end, China’s interest in the region is growing and could fuel new trade opportunities. The Chinese authorities have expressed their interest in developing imports of non-energy commodities and have invested heavily in infrastructure in the region as an alternative to the Northern Route.

Countries in Central Asia and the South Caucasus are also contributing to the emergence of trade routes. The intensity of high-level dialogue within the region and with global partners shows that trade facilitation is a priority topic for policymakers. Governments have been carrying out trade reforms and have invested heavily in East-West transport infrastructure.

The Middle Corridor has the potential to become a viable route if capacity constraints and regional co-operation issues are addressed

The Middle Corridor has the potential to become a viable and strategic route between Asia and Europe through Central Asia and the South Caucasus. Traffic has been strongly growing on the Middle Corridor following the restrictions on the Northern Route. The route benefits from solid fundamentals, with important economic and demographic growth, and the possible development of China as a consumption economy, ensuring the growth of the markets served by the corridor.

This report aims at identifying the priority reforms and enhancements to be made in terms of trade facilitation, stakeholder co-ordination and infrastructure to improve the competitivity of the route. The conclusions are based on both a comprehensive survey and qualitative interviews conducted with public and private stakeholders.

These consultations highlighted the capacity limitations at several bottlenecks along the corridor. The increase in traffic following the shift away from the Northern Route in 2022 increased waiting times at ports and border crossings, hampering the competitiveness of the route. Issues preventing the development of the corridor are not only related to infrastructure, but also to the lack of economic integration in Central Asia and the South Caucasus. Enhancing the route’s attractiveness will require facilitating trade to ease pressure at border crossing and increase demand for transport in a regional perspective.

Table 1.2. Overview of identified reform priorities

|

Priority areas |

Increasing regional economic and trade integration |

Improving transport infrastructure capacity |

Advancing trade facilitation |

Enhancing national and transnational co-ordination |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Suggested priority reforms |

Improve framework conditions for private sector development to stimulate demand along the Middle Corridor |

Develop multimodal infrastructure at ports and border points |

Harmonise transit and transport regulation, harmonise and digitalise border and transit documents for all transport modes |

Develop the institutional tools to support a common approach to the development of the route |

|

Improve logistics services to increase the efficiency and reliability of the route |

Increase fleet capacity and regularity in the Caspian Sea |

Build customs capacity at the national and regional level to reduce border procedure times |

Align national, transnational and regional infrastructure plans |

|

|

Improve regulatory frameworks and planning capacities for environmental standards |

Develop rail capacity |

Advance trade facilitation reforms at the regional level and in line with European standards |

Source: OECD analysis (2023).

References

[27] ADB (2021), Middle Corridor - Policy Development and Trade Potential of the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route, https://www.adb.org/publications/middle-corridor-policy-development-trade-potential.

[30] ADB (2021), Middle Corridor - Policy Development and Trade Potential of the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route, https://www.adb.org/publications/middle-corridor-policy-development-trade-potential.

[18] Adilet (2022), On approval of the Concept of Development of Transport and Logistics Potential of the Republic of Kazakhstan until 2030 (Об утверждении Концепции развития транспортно-логистического потенциала Республики Казахстан до 2030 года), https://adilet.zan.kz/rus/docs/P2200001116#z165 (accessed on 21 April 2023).

[22] EBRD (2023), Sustainable transport connections between Europe and Central Asia, https://www.ebrd.com/news/publications/special-reports/sustainable-transport-connections-between-europe-and-central-asia.html.

[32] EBRD (2022), Middle Corridor—Policy Development and Trade Potential of the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route.

[26] Eurasianet (2022), “Turkey and Central Asia: Ukraine war will strengthen ties”, Eurasianet, pp. https://eurasianet.org/perspectives-turkey-and-central-asia-ukraine-war-will-strengthen-ties.

[35] GIS (2021), A closer look at the Eurasian Economic Union, https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/eurasian-economic-union/.

[23] IMF (2023), World Economic Outlook Database, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2023/April/download-entire-database.

[13] IMF (2023), World Economic Outlook: A Rocky Recovery - April 2023, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2023/04/11/world-economic-outlook-april-2023.

[2] Index, E. (2023), ERAI Statistics, https://index1520.com/en/statistics/?direction=all&view=map§ion=route&previousPeriodType=year&period=202202-202302&orderField=currentPeriodTeu&orderDirection=desc.

[20] International Trade Administration (2022), Market Overview, https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/kazakhstan-market-overview#:~:text=Kazakhstan%20has%20an%20export%2Doriented,58%20percent%20of%20total%20exports). (accessed on 15 May 2022).

[15] ITF (2022), Transport Policy Responses to the War in Ukraine.

[16] Middle Corridor Association (2022), The stable growth of transit and container traffic along the TITR was noted in the final report. Thus, over the past year, 25.2 thousand twenty-foot equivalent containers (TEU) were transported along the TITR route, which is 20% more than in 2020., https://middlecorridor.com/en/press-center/news/the-growing-importance-of-the-trans-caspian-international-transport-route-was-discussed-in-turkey.

[5] Ministry of Trade of the Republic of Türkiye (2023b), Yurt Dışı Müteahhitlik ve Teknik Müşavirlik, https://ticaret.gov.tr/hizmet-ticareti/yurtdisi-muteahhitlik-teknik-musavirlik.

[25] Observatory for Economic Complexity (2023), Data visualizer (database), Observatory for Economic Complexity, Cambridge MA, https://oec.world/en/visualize/tree_map/hs92/export/arm.aze.geo.kaz.kgz.tjk.tkm.uzb/arm.geo.kaz.kgz.tjk.tkm.uzb/show/2017.2018.2019.2020.2021/.

[7] OECD (2023), Assessing the Impact of Russia’s War against Ukraine on Eastern Partner Countries, https://doi.org/10.1787/946a936c-en.

[28] OECD (2023), Improving Framework Conditions for the Digital Transformation of Businesses : Peer-Review of Kazakhstan.

[29] OECD (2023), OECD Middle Corridor report - upcoming.

[8] OECD (2022), Assessing the impact of the war in Ukraine and the international sanctions against Russia on Central Asia.

[34] OECD (2022), Boosting the Internationalisation of Firms through better Export Promotion Policies in Uzbekistan, https://www.oecd.org/eurasia/Monitoring_Review_Uzbekistan_ENG.pdf.

[33] OECD (2020), SME Policy Index: Eastern Partner Countries 2020: Assessing the Implementation of the Small Business Act for Europe, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/8b45614b-en.

[17] Port Aktau (2023), The volume of cargo transportation along the Trans-Caspian route increased by 2.5 times (Объем перевозок грузов по Транскаспийскому маршруту вырос в 2,5 раза), https://www.portaktau.kz/ru/obem-perevozok-gruzov-po-transkaspijskomu-marshrutu-vyros-v-25-raza/ (accessed on 3 April 2023).

[21] Presidency of the Republic of Türkiye (2023), Large domestic and regional markets, https://www.invest.gov.tr/en/whyturkey/top-reasons-to-invest-in-turkey/pages/large-domestic-and-regional-markets.aspx.

[19] Prime Minister of the Republic of Kazakhstan (2023), , https://primeminister.kz/en/news/air-flights-increase-and-trans-caspian-international-transport-route-development-10-documents-signed-during-visit-of-alikhan-smailov-to-azerbaijan-24512.

[14] Rail Freight (2022), Middle Corridor unable to absorb northern volumes, opportunities still there | RailFreight.com, https://www.railfreight.com/specials/2022/03/18/middle-corridor-unable-to-absorb-northern-volumes-opportunities-still-there/ (accessed on 24 June 2022).

[10] The State Council of the People’s Republic of China (2022), Full Text: Remarks by Chinese President Xi Jinping at the Virtual Summit to Commemorate the 30th Anniversary of Diplomatic Relations Between China and Central Asian Countries, http://english.www.gov.cn/news/202305/19/content_WS6467059dc6d03ffcca6ed305.html.

[6] Turkish Statistical Institute (2023), Foreign Trade, https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Kategori/GetKategori?p=dis-ticaret-104&dil=1.

[12] UN Comtrade (2023), UN Comtrade Database, https://comtradeplus.un.org/.

[9] UNCTAD STAT (2022), Merchandise trade matrix in thousands United States dollars, annual, 2016-2020 (database), https://unctadstat.unctad.org/wds/TableViewer/tableView.aspx?ReportId=217476&IF_Language=eng (accessed on 23 June 2022).

[4] UNESCAP (2022), Connectivity along the Eurasian Northern Corridor, https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/d8files/Ch%201%20Connectivity%20along%20the%20Eurasian%20Northern%20Corridor.pdf.

[24] United Nations (2022), Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, https://population.un.org/wpp/Download/Standard/Population/.

[31] USAID (2022), Trans-Caspian Corridor Development, https://www.carecprogram.org/uploads/19th-TSCC_A05_USAID-TCAA.pdf.

[3] World Bank (2022), Equitable Growth, Finance and Institutions Insight, World Bank Group, Washington DC, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099750104252216595/pdf/IDU0008eed66007300452c0beb208e8903183c39.pdf.

[1] World Bank (2020), Improving Freight Transit and Logistics Performance of the Trans-Caucasus Transit Corridor, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/701831585898113781/pdf/Improving-Freight-Transit-and-Logistics-Performance-of-the-Trans-Caucasus-Transit-Corridor-Strategy-and-Action-Plan.pdf.

[11] World Bank (2020), South Caucasus and Central Asia - The Belt and Road Initiative, https://doi.org/10.1596/34122.