Increased regional economic and trade integration, especially in the South Caucasus and Central Asia, will be critical to generating increased traffic and demand along the Middle Corridor. While this is a long-term goal, governments advance it now by (i) creating more favourable conditions for private sector development in Central Asia and the South Caucasus; (ii) developing regional logistics services to support the development of both trade and transit in the short to medium term; and (iii) fostering common standards for a more sustainable approach to the development of the route.

Realising the Potential of the Middle Corridor

2. Further regional economic and trade integration is key to the route’s long-term viability

Abstract

This chapter explains how increasing regional economic integration can contribute to the Middle Corridor’s competitiveness by stimulating demand for freight transport along the route on the long run, and rather than seeing it solely as a substitute for the Northern Corridor. First, it sheds light on the low integration of Central Asia and Southern Caucasus countries in global trade beyond the export of commodities. Then it looks at the gaps in the logistics sector preventing the development of the route’s potential. Finally, the chapter formulates recommendations on how to develop private sector demand for the route and increase the quality of logistics services.

This chapter, as well as in the rest of the report, relies in great part on a policy consultation that the OECD conducted to identify bottlenecks and reform needs in four countries along the corridor – Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Georgia and Türkiye. The consultation focused on trade facilitation, infrastructure and stakeholder co-ordination. The OECD collected over 143 responses, mainly from individual companies, but also from business associations and government entities. The survey questions were adapted to the respondents’ profiles. They centred on the competitiveness of the Middle Corridor, the constraints and bottlenecks encountered while operating on the Middle Corridor and possible improvements in terms of infrastructure and trade facilitation. Qualitative interviews complemented the survey and allowed for a better overview of the challenges for governments and private sector user of the Middle Corridor.

Limited integration into global trade constrains private-sector demand for the Middle Corridor

The corridor countries’ trade integration could improve

The participation of the South Caucasus and Central Asia in global trade is limited

Only 45% of companies responding to the OECD survey indicated that they used the Middle Corridor as a main route for their operations; the chief determinant for their decisions was access to a regional market. While companies are discouraged by practical issues, such as non-competitive transport costs, limited digitalisation of services, and lack of infrastructure, the absence of a sufficient demand for a wide range of goods remains a major factor reducing the private sector’s interest in trading on the Middle Corridor compared to other trade routes. Indeed, a majority of respondents using the Middle Corridor as a main route respond to European demand and, therefore, use the corridor for transit only. Government agencies responding to the survey consider weak regional demand the foremost reason preventing the use of the Middle Corridor.

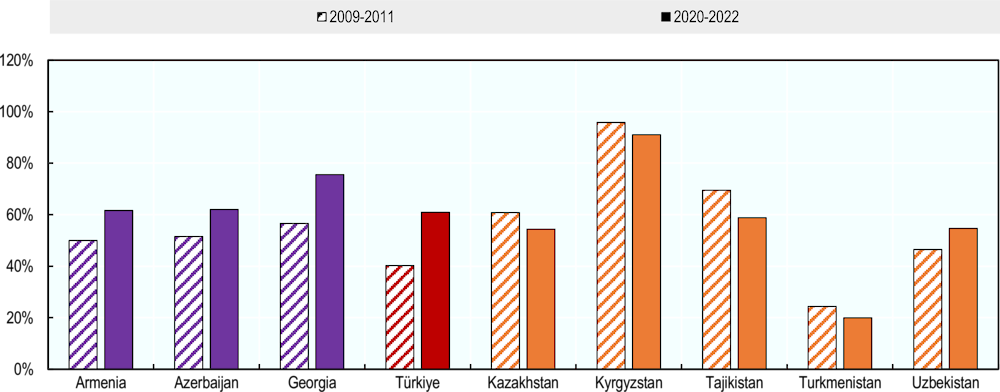

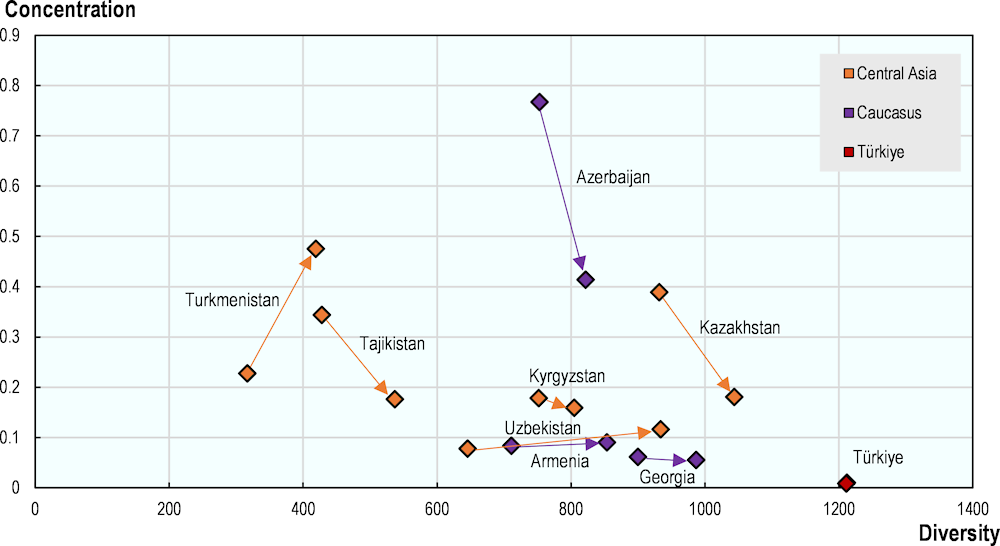

The economies of Central Asia and the South Caucasus have both relatively undiversified export baskets and a limited range of trading partners. Despite significant differences in terms of population, resource endowments and economic structures, the economies of the two regions are characterised by export concentration in terms of both products and destinations, chiefly China and Russia in terms of export markets (see Chapter 1). Even if the region’s economies were to start diversifying, the impact on the composition of output would be limited for some time (Figure 2.1). For instance, between 2000 and 2021, all countries of the region significantly increased the range of exported products. Kazakhstan and Georgia have by far become the most diversified exporters, respectively, in Central Asia and the South Caucasus, in terms of the number of different export products (diversification of the export basket), and they are moving closer to OECD countries such as Türkiye. However, the concentration of either country’s exports in value terms did not change in the same proportions. It increased for Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Armenia, meaning that the overall concentration of their export baskets in terms of volume and value has increased. Moreover, Kazakhstan is an interesting case: while it followed the same pattern as these three countries between 2010 and 2019, with an increased concentration of hydrocarbon products in its export basket, the relative de-concentration of exports between 2010 and 2021 masks a shift in Kazakhstan’s commodity exports between 2019 and 2021, as the share of metals rose by 20 percentage points in the export basket, lowering the share of mineral fuels from 67% to 47% of total exports (OECD, 2023[1]; The Observatory of Economic Complexity, 2023[2]). A similar trend of relative de-concentration of exports (rather than of diversification) can also be observed in Azerbaijan, with the share of mineral fuels in exports decreasing only slightly from 94% in 2010 to 88% in 2021. This continuing reliance on hydrocarbons reflects low levels of competitiveness in non-oil sectors and the and persisting connectivity barriers that firms continue to face in international trade (OECD, 2021[3]; OECD, 2020[4]; OECD, 2023[1]).

Figure 2.1. Evolution of export diversification in Central Asia, the South Caucasus and Türkiye, 2010-2021

Note: The concentration of exports is measured with a normalised Herfindahl-Hirschman index (HHI) on exported products classified according to the HS 4-digit system. Diversity is measured as the number of exported products according to the HS 4-digit system. The HHI is an index, traditionally used to assess the concentration of markets for competition regulators, with a value of 0.15 corresponding to low concentration, 0.15-0.25 a moderate concentration, and above 0.25 a high concentration. When measuring export diversification, a concentration of 0.10 still indicates a high concentration. The HHI being a non-linear indicator, a 0.1 change does not represent the same gap at different levels of concentration.

Source: OECD calculations (2023) based on OEC data (The Observatory of Economic Complexity, 2023[2]).

Exports remain an important growth driver in Central Asia and the South Caucasus. In Armenia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan, the share of exports in GDP has been increasing between 2010 and 2022; a similar, though more moderate, trend is observed for Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan.

Yet Central Asia remains in some respects at the margins of international trade. Overall, Central Asian countries other than Kazakhstan remain less integrated into international trade than their regional neighbours or many other countries at similar levels of income. Though trade openness ratios can be relatively high, particularly for Kyrgyzstan, they don’t reflect an important integration in global trade. Indeed, Central Asian countries mostly export commodities and import finished investment and consumption goods, without for the most part being well integrated into Global Value Chains.

This low integration should seen in a larger context, though, as classical trade integration indexes do not reflect integration in the global economy through labour migration. The Heckscher Olin model of international trade posits that a country will export goods that are relatively intensive in the factors that it has in abundance. In this respect, countries of Central Asia and the Southern Caucasus might be expected to export labour-intensive goods. Yet, because of the low development of manufacturing sectors, institutional weaknesses and transport challenges, they “export” labour instead, sending large numbers of migrant workers abroad, chiefly (but not only) to Russia. As a result, Central Asia and Southern Caucasus countries, except for Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan, rely greatly on remittances from migrant workers. In 2022, these remittances were estimated to equal 32.1% of GDP in Tajikistan, 31.3% in Kyrgyzstan, 18.9% in Armenia, 17.1% in Uzbekistan and 16.3% in Georgia (World Bank, KNOMAD, 2022[5]).

Figure 2.2. Trade openness (total exports and imports as a percentage of GDP) in Central Asia, the South Caucasus and Türkiye, 3 years average for 2009-2011 and 2022-2022

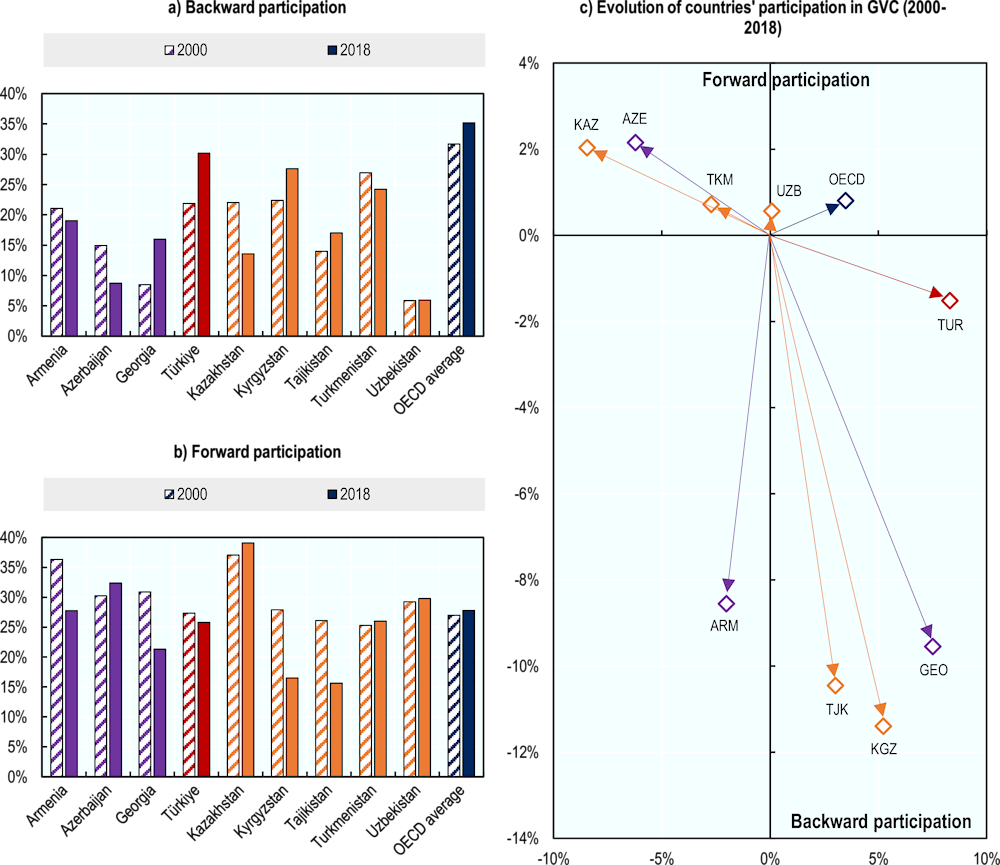

This diverging trend between the two regions can be explained in part by differences in the evolution of their economic structures and by the South Caucasus countries’ improving GVC participation. Over the last decades, several Eastern Partnership countries have been investing in the development of their manufacturing sectors and increasing their participation in GVCs (Box 2.1). As a result, backward participation has increased for Georgia, even if its absolute participation remains below the levels observed for more advanced OECD economies such as Türkiye or Germany (Figure 2.3). This trend is indicative of a persisting gap in the sophistication of their manufacturing output, reducing both export opportunities and the need for intermediate input imports of foreign components. However, forward participation has been rising substantially for Armenia and Azerbaijan, while backward participation has been deteriorating due to the prevalence of primary commodities (hydrocarbons, metals and agricultural products) in their export baskets. This evolution indicates that increased energy and mineral exports have reduced the relative contribution of foreign added value, while they represented the countries’ main inputs in partner countries’ production (OECD, 2023[9]).

Box 2.1. Defining countries’ participation in global value chains

Global value chains (GVC) have emerged as a defining feature of the world economy

In a globalised and interconnected world, production processes are frequently fragmented and dispersed across different countries. Therefore, the flows of goods and services with these global production chains are not always reflected in conventional measures of international trade: a single country is rarely responsible for the export of a given good, and the analysis of international trade from the export/import approach becomes insufficient to infer the role of a given country.

Analysing participation in GVCs

While traditional measures of gross exports can be subject to double accounting, new approaches in terms of value added can distinguish between the domestic and foreign share of value added in each country’s exports: a given country’s exports are composed of domestically produced value added, but also of foreign value added previously imported. Therefore, two questions arise: to what extent is a country dependent on imported foreign production to export? To what extent does a country contribute to the exports of other economies through its domestic production?

Two indicators are therefore considered when analysing GVCs:

Backward participation: corresponds to the value added of inputs that were imported to produce intermediate or final goods/services to be exported. It is computed as the share of foreign value added of exports in total gross exports.

Forward participation: represents the domestic value added contained in intermediate goods/services exported to a partner economy that re-exports them to a third economy embodied in other products. It is computed as the share of domestic value added sent to third economies in total gross exports.

Source: (WTO, 2018[10]; UNCTAD-Eora, 2019[11]).

Kazakhstan’s participation in GVCs has been declining over the last decade, reflecting both a heavy reliance on commodity exports and higher relative trade costs. Like Armenia and Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan is substantially forward integrated into other countries’ exports as a supplier of primary and intermediate inputs, especially raw materials (hydrocarbons and metals), though the country’s backward integration into GVCs is weak. Since the early 2000s, the share of foreign value added in Kazakhstan’s exports has halved to 9.7% in 2018, the latest available year, well below the levels of some comparable resource-rich countries such as Indonesia (14.4%), and far below the levels found in highly integrated countries such as Mexico (35.9%) (OECD, 2021[12])1. Most strikingly, the decrease in use of foreign inputs is found across all industries in Kazakhstan and seems to reflect higher relative trade costs linked, inter alia, to transport, logistics, tariff structure, and non-tariff measures (World Bank, 2020[13]).

Figure 2.3. Participation of Central Asia and South Caucasus countries in GVCs

Note: Backward participation in the global value chain refers to the ratio of the foreign value-added content of exports to the economy’s total gross exports. Forward participation in the global value chain corresponds to the ratio of the domestic value added sent to third economies to the economy’s total gross exports. The third graph (c) simultaneously shows the evolution in percentage points of countries’ backward and forward participation in GVC, between 2000 and 2018. The North-East quadrant indicates an increase in both backward and forward participation, while the South-West quadrant indicates a decrease in both backward and forward participation.

Source: (UNCTAD-Eora, 2019[14])

Central Asia suffers from a significant connectivity gap to international markets, which acts as a constraint on export growth and integration into GVCs. Geographic remoteness from major global transport networks imposes distance and transport costs on local manufacturers and reduces the attractiveness of transport routes running through the region, the latter mainly related to border crossing and handling costs. Distance and cost each accounted for about a third of Central Asia’s connectivity gap in 2019, with the estimated cost of accessing market demand equivalent to 20% of world GDP amounting to USD 300 per tonne for Kazakhstan, compared to USD 50 per tonne for Germany and the United States – two of the world’s best-connected economies. Moreover, the average distance for a Kazakh manufacturer to reach markets representing the equivalent of 20% of global GDP is 4000km, twice as much as for a German or US manufacturer (OECD-ITF, 2019[15]).

Intra-regional trade remains under-developed in Central Asia and the South Caucasus

There is limited trade integration between the four countries covered by this report, as economies of Central Asia and the South Caucasus are bound more by geographical proximity and historical legacy than by regional intra-industry trade patterns. Table 2.1 displays the IIT index for the four Middle Corridor countries under study here (Box 2.2). The number of products subject to intra-industry trade is quite limited. Although there are small fluctuations, there is an increase in the IIT index at the bilateral level among Middle Corridor countries from 2002 to 2022, especially between Georgia and Türkiye. The weighted indices of Georgia and Türkiye for other Middle Corridor economies have also risen over this period. However, the indices are quite low when compared to intra-industry trade in other partner country groups such as the EU, as the IIT index for the EU in Turkey was 0.404 in 2007 and 0.442 in 2018 (Nikolić and Nikolić, 2023[16]).

The low IIT product share in trade between countries signals a lack of division of labour amongst them. The sectoral composition of the intra-industry trade is concentrated on a few agricultural and industrial products. The countries under study may also exchange commodities that can be found specifically in one country, but there is a lack of specialisation in higher value-added industries that could foster the development of intra-industry trade.

Table 2.1. Intra-Industry Trade/Regional Trade Potential in Central Asia and the South Caucasus

Trade Among MC Countries (Except Reporter Country)

|

Reporter Country |

Variable |

2002 |

2012 |

2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Azerbaijan |

Number of IIT* |

6 |

6 |

13 |

|

IIT Import Share |

0.28% |

0.16% |

0.68% |

|

|

IIT Export Share |

3.89% |

7.15% |

0.28% |

|

|

Weighted IIT Index |

0.016 |

0.028 |

0.024 |

|

|

Georgia |

Number of IIT* |

18 |

23 |

28 |

|

IIT Import Share |

1.65% |

2.07% |

1.71% |

|

|

IIT Export Share |

7.90% |

2.79% |

3.70% |

|

|

Weighted IIT Index |

0.036 |

0.056 |

0.064 |

|

|

Kazakhstan |

Number of IIT* |

12 |

12 |

26 |

|

IIT Import Share |

4.50% |

0.34% |

1.91% |

|

|

IIT Export Share |

2.16% |

0.08% |

0.55% |

|

|

Weighted IIT Index |

0.052 |

0.007 |

0.021 |

|

|

Türkiye |

Number of IIT* |

7 |

8 |

13 |

|

IIT Import Share |

0.06% |

1.54% |

0.49% |

|

|

IIT Export Share |

0.14% |

1.25% |

0.53% |

|

|

Weighted IIT Index |

0.014 |

0.021 |

0.050 |

Note: *: Number of IIT indicates the items whose IIT index is equal to or higher than 0.5

Source: OECD analysis.

Table 2.2. Intra-Industry Trade among Middle Corridor countries

|

Reporter Country |

Partner Country |

2002 |

2012 |

2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Azerbaijan |

Georgia |

0.031 |

0.027 |

0.020 |

|

Kazakhstan |

0.006 |

0.006 |

0.017 |

|

|

Türkiye |

0.017 |

0.032 |

0.026 |

|

|

Georgia |

Azerbaijan |

0.062 |

0.057 |

0.086 |

|

Kazakhstan |

0.001 |

0.004 |

0.025 |

|

|

Türkiye |

0.019 |

0.061 |

0.062 |

|

|

Kazakhstan |

Azerbaijan |

0.102 |

0.013 |

0.094 |

|

Georgia |

0.022 |

0.005 |

0.004 |

|

|

Türkiye |

0.029 |

0.007 |

0.018 |

|

|

Türkiye |

Azerbaijan |

0.016 |

0.027 |

0.054 |

|

Georgia |

0.021 |

0.043 |

0.091 |

|

|

Kazakhstan |

0.010 |

0.002 |

0.019 |

Note: The indices in the table show the weighted IIT index of each reporter-partner country pairwise. Theoretically, for a given pair of countries, values should be symmetrical. Here, it is not the case because of reporting inconsistencies for trade values.

Source: OECD analysis.

Box 2.2. Interpretation of the intra-industry trade index (IIT)

Intra-industry trade occurs when two countries both export and import similar goods between one another. For instance, France and Germany both import and export an important number of cars from each other. The Intra-industry trade index (ITT), also known as the Grubel-Lloyd (GL) Index, is the most widely used measure of intra-industry trade in the literature.

There is an ITT for each country pair and specific good. The closer the ITT is to 1, the more intra-industry trade there is between these two countries for this good. An ITT of 0 means that no intra-industry trade occurs for this good.

The weighted ITT for a country pair represents the average intra-industry trade of the two countries, weighted by the importance of each industry in the total trade between the two countries. The higher the index, the more intra-industry trade occurs between the two countries. Developed countries typically have higher ITT indexes.

Though Central Asian countries have engaged in regional integration initiatives, they have not achieved much change in intra-industry trade patterns. This is mainly due to the loose and shallow nature of engagement aimed at only bonding tariff structures and insufficient implementation of the existing arrangements but also lack of market-based integration in the region (Box 2.3). In any case, the embryonic stage at which intra-industrial trade is in Central Asia means that there is considerable scope to increase it and therefore grow the demand for freight transport in the region.

Box 2.3. Dynamics of intra-industry trade (IIT) and regional integration in the world

Intra-industry trade represents international trade within industries rather than between industries. Such trade is argued to have more beneficial spillover effects than inter-industry trade because it stimulates innovation and exploits economies of scale and of scope. Moreover, since productive factors do not switch from one industry to another, but only within industries, intra-industry trade is less disruptive than inter-industry trade. About 60% of U.S. trade or European trade is intra-industry. Around 80% of U.S. trade with Mexico is intra-industry.

Intra-industry trade in Eastern Europe

IIT is often high for economies where FDI inflows have risen sharply. Among the countries with the most rapid increase in intra-industry trade over the 1990s were the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and the Slovak Republic. All these countries were characterised by high and increasing inflows of foreign direct investment (FDI) over the 1990s, especially from Germany. The combination of rising intra-industry trade and high foreign direct investment inflows is also observed as consistent with the increasing extent to which multinational firms have located parts of their production operations in these countries. Partly reflecting the trends in these countries, and the fact that there has been a steady increase in foreign direct investment outflows over the 1990s, Germany has also experienced a relatively rapid increase in intra-industry trade over the 1990s.

Intra-industry trade patterns have not developed yet in Central Asia

In Central Asia, the initial conditions were entirely different. The manufacturing matrix and integrated market did not exist in this region. In addition, Central Asian countries had not established a market-based resource allocation mechanism, they lacked diverse industrial structures, and they were located inland, far from the centres of global demand. Therefore, it is uncertain whether, and to what extent, regional trade agreements among Central Asian countries promoted the intra-regional trade. Byrd et al. (2006) point out that the current Central Asian economies would achieve dramatic growth in trade and economic welfare if they co-operated in trading policies, border control, customs clearance, and transport management.

Most of the countries that have relatively low and stable intra-industry manufacturing trade are also those that are most heavily dependent on non-manufactured goods in total exports. This indicates that the low share of intra-industry trade reflects a tendency for a high proportion of these countries’ manufactured exports to consist of relatively simple transformations of the raw materials with which the country is endowed and that such transformations are not suited to division across different countries.

In Central Asia road freight traffic is largely concentrated around local markets and population hubs and does not outline important regional trade flows. Historically, South Caucasus countries have been – and remain – an important transit corridor, well connected to international routes. Georgia has access to the Black Sea, Azerbaijan has a coast on the Caspian Sea, and the two countries have solid rail and road connections with Türkiye. Given Central Asia’s landlocked position and relatively low population densities, road freight flows are concentrated around local markets and population hubs. Around urban centres, traffic on the region’s road network is comparable to traffic in OECD countries, dropping by a factor of three outside these areas and falling at border crossing points (BCPs). As a result, road freight mainly serves local markets, with 50% to 70% of trucks operating on inter-urban services. Official statistics indicate an average shipment distance under 100 km, falling to 20 km in Uzbekistan (OECD-ITF, 2019[15]).

Weaknesses in the overall business climate in Central Asia and the South Caucasus constrain private sector development and export growth

In Central Asia and the South Caucasus, the connectivity agenda is directly linked to structural reform challenges. Lower population densities and longer distances to major markets weaken competition and reduce productivity and innovation incentives. As a result, smaller goods baskets and higher prices confront domestic consumers, while domestic exporters face a competitive disadvantage, as competitive exports require sufficiently high productivity to offset higher transport costs. Weak domestic business environments undermine local competition, prevent productivity growth, and fail to protect local producers when enhanced connectivity leads to reduced trade protection (OECD-ITF, 2019[15]; López González and Sorescu, 2019[22]; OECD, 2021[23]).

In Central Asia, the pace of regulatory reforms and implementation gaps hinders confidence and predictability. Countries across the region have adhered to major international organisations and instruments that enable and govern foreign trade and developed relatively sound legal and regulatory frameworks for investment. Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan have joined the World Trade Organisation (WTO), with Uzbekistan an observer; all have joined the World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO), ratified the Convention of the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (except Tajikistan) and signed the New York Convention (except Turkmenistan). More broadly, over recent years key anticorruption reforms, including increased digitalisation of public services, have improved the transparency of government and local public authorities and facilitated dialogue with representatives of the non-governmental sector. However, across all countries, implementation lags, creating low confidence, uncertainty, and administrative hurdles for domestic and international businesses alike. In particular, the pace of regulatory change remains a headache for private sector development, as firms face difficulties in adapting, while public administration lacks the time and capacities to properly implement changes, creating new barriers to business operations. (OECD, 2021[23]).

Despite reforms, remaining obstacles prevent the growth of SMEs in South Caucasus Since the early 2000s, countries across the region have been working to reform their business environments, focusing in priority on the development of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and investment, the reduction of informality and corruption, and levelling the playing field between enterprises of all sizes and ownership types. However, important gaps remain, such as ensuring business integrity, competitive neutrality and equal access to inputs and markets for all businesses, all of which impede internationalisation efforts. In particular, the economic potential of the region’s SMEs, which represent up to 99% of firms, 57% of private sector employment and 47% of value added, remains largely untapped, with the vast majority of SMEs being subsistence micro-entrepreneurs operating mainly in low-value added sectors and with a limited propensity for export (OECD, 2020[4]).

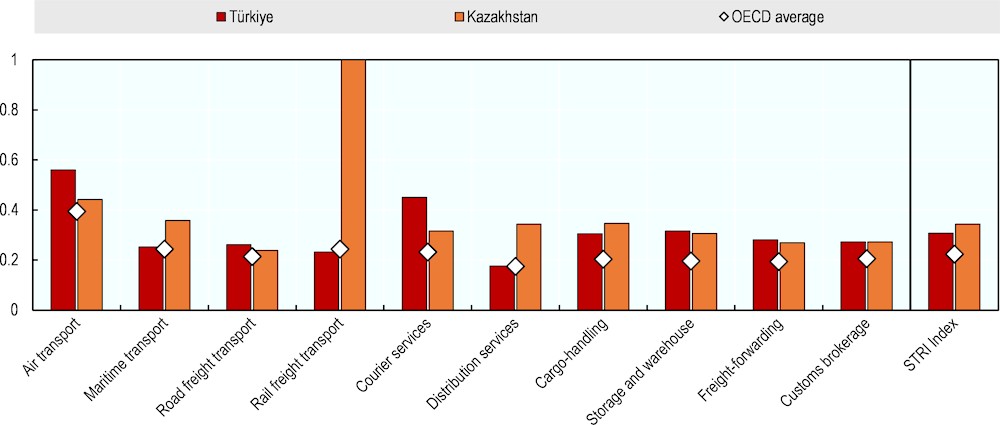

Restrictions and barriers in tradable services remain in the countries covered here, as illustrated by the data collected in Kazakhstan and Türkiye by the OECD. Despite a relatively open overall regulatory framework for investment, the OECD Services Trade Restrictiveness Index (STRI) reveals that Kazakhstan is the seventh most restrictive of the 50 economies covered by the index, even if services trade restrictions have been somewhat relaxed in recent years following the country’s WTO accession (OECD, 2023[24]). Among the most heavily regulated service sectors are those in logistics and related services, including maritime and rail freight transport, as well as cargo handling (Figure 2.4). This impedes their ability to deepen regional integration and engage in enter regional and global value chains. While above the OECD average on nearly all logistics and trade services indicators, Türkiye scores better on rail freight transport and distribution services and performs better than Kazakhstan on maritime and rail freight transport, as well as cargo handling. However, Türkiye performs less well than both Kazakhstan and the OECD average on freight forwarding.

Figure 2.4. Kazakhstan and Türkiye’s performance in the OECD Services Trade Restrictiveness Index (2022)

Note: The maximum score of 1 represents the highest level of regulation, often in relation to a total state monopoly, which is for instance the case for rail freight transport in Kazakhstan. Data for other countries of Central Asia and the South Caucasus is not available (not part of OECD database)

Source: (OECD, 2022[25])

Regional logistics services remain underdeveloped along the Middle Corridor reducing transit efficiency and reliability

High prices and low capacity along the Middle Corridor weigh on its competitiveness

Companies surveyed declared that non-competitive logistics prices and the low capacity of fleets hamper the Middle Corridor’s ability to represent an alternative to the Northern Corridor. Respondents stress that Middle Corridor economies need to develop an offer for integrated national freight-forwarding and logistics services in the region to enhance the route’s viability. Moreover, surveyed firms consider that the under-developed logistics sector is another serious challenge that hinders the development of regional markets in Central Asia, the South Caucasus, and Türkiye. According to respondents of all kinds (individual companies, business associations, and government agencies), a major consequence of Russia’s war in Ukraine was the rise in logistics service prices in the region and a shortage of containers. In reaction, a plurality of businesses was forced to change their logistics network and work with new actors, upsetting the stability and reliability of flows.

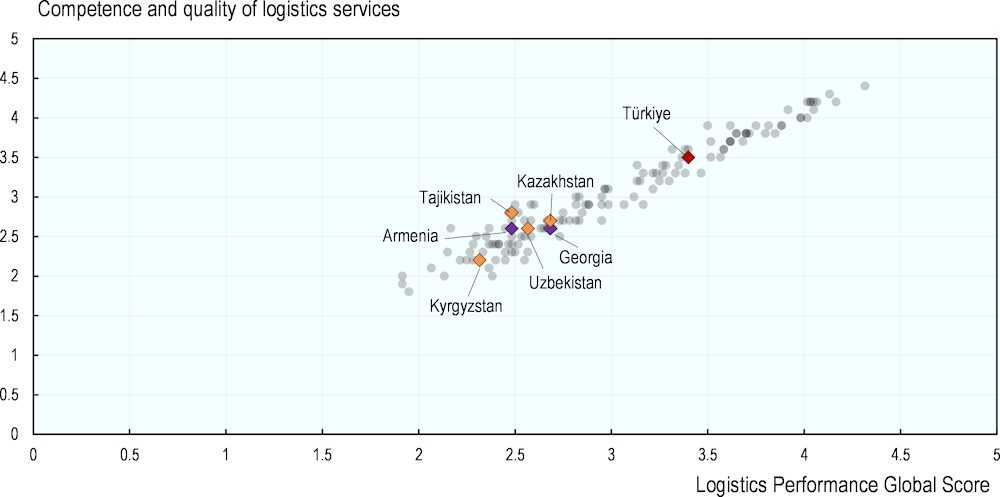

Figure 2.5. Logistics and services trade performance of Central Asia, South Caucasus, and Türkiye

Box 2.4. Overview of the logistics sector in Türkiye

Türkiye in the World Bank Logistic Performance Index (LPI)

Türkiye is an upper-middle income country that has witnessed rapid economic growth and export expansion over the past decade, combined with keen attention to related policy actions including transport policy. In addition, Türkiye has shown a rather coherent development in the World Bank Logistic Performance Index (LPI) on several accounts until 2016 when the country`s performance declined until returning to an upward trajectory by 2023. Türkiye ranks 38th out of 139 countries in 2023 with a score of 3.4, indicating a relatively strong logistics performance compared to peer countries in the Middle Corridor (Kazakhstan and Georgia’s equal scores of 2.7 place them 79th). Türkiye increased its ranking in all dimensions except the quality of trade and transport infrastructure. It performs rather well in ease of arranging competitively priced shipments jumping from 53rd in 2018 to 26th in 2023, and in quality of logistics services. Customs, scoring the lowest, still improves performance compared to 2018.

The logistics industry in the economy

Especially in emerging and developed economies, the main driver of logistics services is the quality of services. In logistics-friendly countries, shippers already outsource much of their logistics, in particular transport and warehousing operations, to third-party providers. The Turkish logistics market has grown rapidly and has attracted many international players through joint ventures. The share of transport services in GDP ranges from approximately 6% to 12% in developed countries. In Türkiye, the average share of transport and storage services in total GDP between 1998 and 2019 is around 9.0%; it reached 8.8% in 2021 after declining to 7.9 % in 2020. The share of transport and storage services in GDP ranks third in the Turkish economy after the "manufacturing industry" and "wholesale and retail trade and repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles”.

Turkish logistics performance is primarily strengthened by the development of the private sector, which has evolved significantly in the last decade. It constitutes a growing number of international companies with overseas offices and the industry has experienced a transition from independent logistics service suppliers to integrated logistics service providers. However, many manufacturing companies still run their logistics operations in-house without extensive use of third-party logistics (3PL) providers. Türkiye’s extensive network of chambers of commerce and industry associations are also strong promoters of the logistics industry; The Union of Chambers and Commodity Exchanges of Türkiye (TOBB) has financed the building of new Turkish border crossing points for instance.

Trade and logistics

Trade, and predominantly merchandise trade, has been a major driving force behind Türkiye’s overall connectedness. Maritime transport dominates Turkish foreign trade by value accounting for 55.7%, followed by road transport (22.4%), air transport (9.6%) and railways (1%). Sea transport is projected to remain the dominant transport mode for international trade in 2025, measured in tonne-kilometres. The average share of rail transport is estimated to remain at around 1% between 2010 and 2025, according to ITF’s projections. The Ministry of Trade has started to extend its support program for improving the quality and quantity of logistical services in the country. Trade in Transport and logistical services account for 40.3% of trade in services in Türkiye reaching 51.7 billion USD in 2022.

Rail and maritime tariffs and schedules are unpredictable and often poorly accessible

The Middle Corridor International Association annually sets the tariff schedules for rail and maritime cargo transport along the route. Established in 2017, the Working Group of the TITR Association is composed of the representatives of the national railway companies of Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Kazakhstan, of the ports of Aktau (Kazakhstan), Baku (Azerbaijan), and Batumi (Georgia), and of Azerbaijan Caspian Shipping (ASC), the main Caspian Sea ferry operator. In co-operation with associate members and partners, including the chief port management and transport companies, the Working Group sets the freight tariff rates for cargo transport along the rail and maritime segments of the route (ADB, 2021[34]; Middle Corridor Association, 2023[35]). Azerbaijani railroads JSC, Kazakhstan Temir Zholy JSC and Georgian Railway JSC have signed an agreement to create a single logistics company to deal with issues of tariff policy, cargo handling and transport process simplification on the TITR (Prime Minister, 2023[36]). The 2022-27 TITR Roadmap refers to carrying out a stable and competitive tariff policy in the railway sector and compliance with established through rate for transport along the Middle Corridor.

However, despite such co-ordination efforts, interviewees report unpredictable and poorly accessible rail and maritime tariff schedules. During interviews conducted by the OECD, transport and logistics companies raised the issue that actual rail and maritime tariff schedules often differ from the TITR agreed rates, in some cases with substantial amounts. These findings also seem to concur with a forthcoming World Bank study hinting at a substantial gap between agreed TITR association tariffs and the actual ones paid by transport companies along the route. In addition, interviewees raised the issue of an absence of clear communication on tariff schedules and their changes, reporting many instances where the cargo transporter is only informed of the actual tariff when arriving either at the rail or the maritime loading terminal. Sharp increases in transport costs, often at short notice, reduce the predictability of shipment costs for freight forwarders and thus the attractiveness of the route.

Overall, quasi-monopolies hamper the development of this sector

These issues point to a wider issue of price competitiveness along the route due to quasi-monopolies in rail and maritime freight services. Even if actual data are difficult to obtain, OECD interviews suggest that the cost of cargo delivery along the route from China to Europe is more than twice as high as on the Northern Corridor and amounts to about USD 5500 per TEU. Interviews conducted by the OECD indicate that tariff levels result in part from the quasi-monopolistic behaviour of the dominant railway and shipping companies. For instance, although Kazakhstan opened railway freight to competition since January 2021, allowing for the creation of private freight carriers, the cargo branch of the national operator KTZ retains a monopoly over freight traffic. Indeed, while the Ministry of Industry and Infrastructural Development of Kazakhstan delivers licenses to private freight carriers allowing for operations across the country, KTZ being the infrastructure operator retains the right to grant access to the network. Interviewees reported that in many instances, if access to the network is granted, it is only for small segments, preventing the development of a real private rail freight market. For Georgia, interviewees reported that cargo handling prices and tariffs are among the highest in Europe, mainly due to the monopoly situation of the operator in Poti port. For Azerbaijan, interviewees report that limitations on container usage for shipping to certain destinations imposed by the largest maritime shipping companies reduce the route’s competitiveness. For instance, firms must return containers within a maximum of 14 days when shipping directly to Central Asia. However, Azerbaijan-Central Asia roundtrips are reported to last 25 to 35 days on average due to multiple bottlenecks along the route (see Chapters 3 and 4), with high maritime shipment tariffs doubling due to high downtime payments, amounting to up to USD 50 per day of delay.

Recommendations

Further reforms to improve framework conditions for private-sector development can enhance the region’s trade potential and stimulate demand along the route

Develop national and regional export promotion strategies through SME and entrepreneurship development

The challenges related to the development of the Middle Corridor go beyond the purely technical aspects relating to the construction of modern infrastructure or trade facilitation procedures. It is vital to focus on the conditions of economic development in the countries concerned, particularly the development of diversified and complexified production activities and industries, that would then allow trade with other countries of the region. Indeed, if the increased activity along the Middle Corridor currently benefits from a substitution effect from the Northern Corridor due to the war in Ukraine, the longer-term sustainability of the route requires sufficient demand, as well as enhanced regional economic ties. If the impetus for the development of the Middle Corridor is, for the moment, prompted by the war, it nevertheless represents a real opportunity for the region to develop and benefit from enhanced trade and co-operation. Governments should continue to work to promote innovation and entrepreneurship (innovation hubs, research centres, and entrepreneurship programs to foster innovation and technology-driven growth) and to support SME development (access to financing, technology, and market information, etc).

Governments can also collaborate to formulate comprehensive export promotion strategies tailored to the comparative advantages of each country. These strategies should encompass targeted incentives, market diversification efforts, and capacity-building programmes to help local industries tap into regional and international markets. Governments should support linkages between local SMEs and national or international multinational enterprises (MNEs) to boost GVC integration through know-how and technology spillovers. Government-led regional integration initiatives are more likely to facilitate a level playing field where the countries would be exposed to competition necessary to develop their economies through benefiting from enhanced and deeper integration in larger markets like the EU (Wang, 2014[37]).

Address remaining gaps in the operational environment for firms, particularly in relation to trade and investment

Governments should prioritise addressing barriers that hinder businesses from fully capitalising on the Middle Corridor. This includes streamlining cross-border trade procedures, reducing bureaucratic hurdles, and providing efficient dispute-resolution mechanisms. Additionally, transparent and investor-friendly investment policies should be formulated to attract foreign direct investment and nurture local entrepreneurship. This could include digitalisation of procedures with online single windows for setting up business, targeted toward foreign investors.

The implementation of trade agreements and/or economic areas to promote trade among the countries along the Middle Corridor and their neighbours would enhance the development of regional trade by providing firms a better environment to trade with other countries. ADB (2021[34]) concludes, “In the long run, a trans-Central Asia–Caucasus–Türkiye trade area would enable participating countries to engage more effectively with the EU and China on trade policy, practices, standards, and technical and legal developments. For Middle Corridor economies, transparent pricing, openness to foreign investment, and transparent international agreements all point to a greater level of economic integration across the Middle Corridor economic area, with possibilities for future multilateral trade bloc integration. Creating a uniform transport bloc that could better facilitate trade with both Europe and the PRC is the best possible policy solution for these regional economies.” Such areas would eventually promote intra-regional trade and investment but also attract foreign traders and investors.

Improved logistics services can increase the efficiency and reliability of the Middle Corridor and contribute to more integrated regional markets

Incentivise the development of logistics centres along the route, especially in Central Asia and the South Caucasus

Governments should incentivise private sector participation in establishing modern logistics centres strategically located along the corridor. These centres can act as hubs for efficient cargo handling, storage, and distribution, thus reducing transit times and costs. Improved logistics services would help mitigate the costs arising in connection with the multimodality of the route. Alongside the development of logistics centres, policymakers should support professional training and higher education in the field of logistics and transport. They could also give the private sector a greater voice in the design of national logistics policies.

Harmonise, and clearly communicate, rail and maritime tariffs along the route

The authorities should aim for stable tariffs and predictable and transparent pricing policy. Clarity and transparency would be reinforced by a unique way of communicating these tariffs and other associated issues. These actions could be performed by a single regional oversight body, allowing an easier transmission of the necessary data. The UNECE lists the evaluation of a reliable corridor-wide tariff policy in its priority actions, though it notes the operational difficulties of achieving it. TRACECA is also working on the harmonisation of methodology for tariff calculations on railways and looking for partners who can work with them and finance this research.

Box 2.5. Policies to build a country’s industrial base and export profile: the case of Türkiye

Foreign direct investment policies

Since the 1980s, Türkiye has substantially liberalised its investment regime. One significant milestone was the Foreign Direct Investment Law No. 4875 in 2003. This law allowed foreign investors to establish wholly owned subsidiaries or form joint ventures with local partners, under national treatment. It also prompted stronger protection of investment against expropriation and nationalisation. The OECD FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index for the country, which stood at 0.283 in 1997 (far higher than the OECD average of 0.127) declined to 0.059 in 2019 (lower than the OECD average of 0.064). The total FDI stock of Türkiye, which stood at USD 15 billion in 2002, reached USD 253 billion by the end of 2022 (The Investment Office of the Presidency of the Republic of Türkiye, 2023[38]). In 2022 Türkiye ranked as the 28th most attractive FDI destination (World Bank, 2023[39]).

To attract foreign capital, the Turkish government implements a range of investment incentives. These incentives encompass tax benefits, customs duty exemptions, reduced corporate tax rates, and grants tailored to specific industries or regions. Additionally, the government has introduced sector-specific investments, engaged in Public-Private Partnerships (PPP), and designated free trade zones to further facilitate foreign investments. “Türkiye’s Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) Strategy (2021–2023)”, aims at increasing the share of knowledge-intensive and high-value-added investments and high-quality jobs.

Industrial policies

The acceleration of industrialisation of Türkiye went hand in hand with liberalisation of trade and investment, which created a more market-oriented and business-friendly environment for firms. Turkish exporters benefited from efficiency gains through foreign competition, as well as acquiring new technology through foreign investments. Firm efficiency and overall production also benefited greatly from overall improvements in transport and energy infrastructure, accomplished especially through PPP investments over the past two decades. Specialisation through industrial clusters notably in automobile, textiles, electronics, and most recently the defence industry has increased industrial production, regional employment, and SME development. Türkiye’s 10th and 11th Development Plans put a higher emphasis on increasing the share of R&D and scaling up in global value chains.

Customs Union

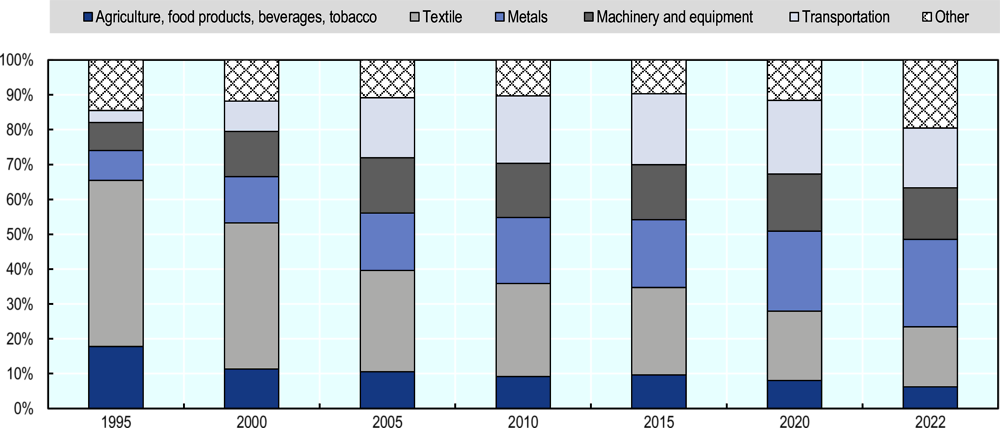

The Customs Union (CU) agreement signed between Türkiye and the European Union in 1995 eliminated customs duties and other barriers in industrial and processed agricultural goods, creating a single customs territory between the EU and Türkiye for the free movement of these goods without tariffs or quantitative restrictions. Going beyond a typical FTA, the CU allowed Türkiye to enjoy the same level of tariff protection from third parties, while levelling the playing field between Turkish and EU companies. Simplification of rules of origin coupled with the elimination of other bureaucratic barriers facilitated trade beyond what would have been the case with a conventional FTA. World Bank estimates that under an FTA, exports from Türkiye to the EU would have been 3.0-7.2% lower, with EU exports to Turkey as much as 4.2% lower compared to what has been achieved under the CU (World Bank, 2014[40]). Mandating Türkiye to harmonise its domestic legislation with EU standards for goods and adopt EU rules on commercial, competition policy, and intellectual property rights, the CU has facilitated the integration of Türkiye’s industrial sector into EU value chains. It has allowed Türkiye to diversify its exports to the EU from traditional sectors of agrifood and textiles towards motor vehicles, chemicals, metals, electronics, and machinery (Figure 2.6).

Figure 2.6. Composition of Türkiye’s exports to the EU27 (1995-2022)

References

[34] ADB (2021), Middle Corridor - Policy Development and Trade Potential of the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route, https://www.adb.org/publications/middle-corridor-policy-development-trade-potential.

[44] Aslam, A., N. Novta and F. Rodrigues Bastos (2017), “Calculating Trade in Value Added”, IMF Working Papers, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2017/07/31/Calculating-Trade-in-Value-Added-45114.

[20] Baldwin, R. (2007), Managing the Noodle Bowl: The Fragility of East Asian Regionalism, https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/28464/wp07-baldwin.pdf.

[19] Byrd, W. et al. (2006), Economic Cooperation in the Wider Central Asia Region.

[6] IMF (2023), World Economic Outlook Database, April, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2023/April.

[42] ITC Trade Map (2023), Trade Map Database, https://www.trademap.org/Index.aspx.

[28] ITF (2019), Enhancing Connectivity and Freight in Central Asia, ITF/OECD.

[27] ITF (2015), Drivers of Logistics Performance A Case Study of Turkey, ITF/OECD.

[22] López González, J. and S. Sorescu (2019), Helping SMEs internationalise through trade facilitation, OECD Trade Policy Papers, No. 229, OECD Publishing, Paris,, https://doi.org/10.1787/2050e6b0-en.

[35] Middle Corridor Association (2023), Middle Corridor Association, https://middlecorridor.com/ru/.

[43] Ministry of Trade of the Rebublic of Türkiye (2021), Gümrük Birliğinin Güncellenme Süreci, https://ticaret.gov.tr/dis-iliskiler/avrupa-birligi/gumruk-birliginin-guncelleme-sureci.

[30] Ministry of Transport and Infrastructure of the Republic of Türkiye (2023), 2053 Transport and Logistics Master Plan, TR Ministry of Transport and Infrastructure.

[16] Nikolić, G. and I. Nikolić (2023), “Can Structural Indicators of Trade Explain Why EU Candidate Countries Are Integrating Slowly?,”, Eastern European Economics, pp. 1-23.

[9] OECD (2023), Assessing the Impact of Russia’s War against Ukraine on Eastern Partner Countries, https://doi.org/10.1787/946a936c-en.

[1] OECD (2023), Insights on the Business Climate in Kazakhstan, https://www.oecd.org/publications/insights-on-the-business-climate-in-kazakhstan-bd780306-en.htm.

[24] OECD (2023), Insights on the Business Climate in Kazakhstan.

[25] OECD (2022), Kazakhstan (2022), OECD Services Trade Restrictiveness Index (STRI), OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/trade/topics/services-trade/documents/oecd-stri-country-note-kaz.pdf.

[3] OECD (2021), Beyond Covid-19: Prospects for Economic Recovery in Central Asia, OECD Publishing, https://www.oecd.org/eurasia/Beyond%20COVID-19%20Advancing%20Digital%20Transformation%20in%20the%20Eastern%20Partner%20Countries%20.pdf.

[23] OECD (2021), Improving the Legal Environment for Business and Investment in Central Asia, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/eurasia/Improving-LEB-CA-ENG%2020%20April.pdf.

[12] OECD (2021), Trade in Value Added database (TiVA), OECD Publishing, Paris, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=TIVA_2021_C1.

[4] OECD (2020), SME Policy Index: Eastern Partner Countries 2020: Assessing the Implementation of the Small Business Act for Europe, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/8b45614b-en.

[18] OECD (2002), Economic Outlook 71, OECD.

[15] OECD-ITF (2019), Enhancing Connectivity and Freight in Central Asia, https://www.itf-oecd.org/sites/default/files/docs/connectivity-freight-central-asia.pdf.

[8] OIC-SESRIC (2023), OIC Statistics Database, https://www.sesric.org/oicstat.php.

[36] Prime Minister (2023), Heads of Kazakhstan and Georgia Government discuss TITR development and increase of mutual trade, https://primeminister.kz/en/news/heads-of-kazakhstan-and-georgia-government-discuss-titr-development-and-increase-of-mutual-trade-24521 (accessed on 28 August 2023).

[33] R.T. Ministry of Industry and Technology and UNDP Türkiye (2021), Logistics Sector Analysis Report and Guidelines TR63 Region (Hatay, Kahramanmaraş, Osmaniye), R.T. Ministry of Industry and Technology General Directorate of Development Agencies.

[17] Ruffin, R. (1999), The Nature and Significance of Intra-industry Trade - Economic and Financial Review.

[38] The Investment Office of the Presidency of the Republic of Türkiye (2023), FDI in Türkiye, https://www.invest.gov.tr/en/whyturkey/pages/fdi-in-turkey.aspx.

[2] The Observatory of Economic Complexity (2023), Countries Profile, The Observatory of Economic Complexity, Cambridge MA, https://oec.world/.

[41] Turkish Statistical Institute (2023), Foreign Trade, https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Kategori/GetKategori?p=dis-ticaret-104&dil=1.

[7] UN (2023), UN Comtrade Database, https://comtradeplus.un.org/.

[31] UNCTAD (2022), Review of Maritime Transport, Navigating Stormy Waters, UNCTAD.

[14] UNCTAD-Eora (2019), Global Value Chain Database, https://worldmrio.com/unctadgvc/.

[11] UNCTAD-Eora (2019), Improving the analysis of global value chains: the UNCTAD-Eora Database, https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/diaeia2019d3a5_en.pdf.

[29] UTIKAD (2022), Lojistik Sektörü Raporu (Report on Logistics Industry), UTIKAD.

[21] Wang, W. (2014), “The Effects of Regional Integration in Central Asia”, Emerging Markets Finance & Trade, pp. 219-232.

[37] Wang, W. (2014), “The Effects of Regional Integration in Central Asia.”, Emerging Markets Finance & Trade, Vol. 50, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24475713.

[26] World Bank (2023), Logistics Performance Index, https://lpi.worldbank.org.

[39] World Bank (2023), World Development Indicators, https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators.

[13] World Bank (2020), Kazakhstan - Trade Competitiveness and Diversification in the Global Value Chains Era, World Bank Group, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/274611580795362180/Kazakhstan-Trade-Competitiveness-and-Diversification-in-the-Global-Value-Chains-Era.

[40] World Bank (2014), Evaluation of the EU-Turkey Customs Union, https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/298151468308967367/evaluation-of-the-eu-turkey-customs-union.

[5] World Bank, KNOMAD (2022), Remittances Brave Global Headwinds.

[10] WTO (2018), Trade in Value Added and Global Value Chains, https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/statis_e/miwi_e/explanatory_notes_e.pdf.

[32] Zhang, G. (2023), Turkey’s place in the Asia-Europe logistics reconfiguration, https://market-insights.upply.com/en/turkeys-place-in-the-asia-europe-logistics-reconfiguration.

Note

← 1. The report prioritises the use of OECD data, and therefore the OECD TiVA database (2021) when it comes to analysing the participation of countries in global value chains. However, among the countries of the present study, the OECD TiVA database only covers Kazakhstan and Türkiye. For the needs of our analysis, the UNCTAD-Eora database (2019) has also been used. Results across the two databases may differ but an overall consistency is observed (UNCTAD-Eora, 2019[11]). In an IMF working paper, Aslam et al. (2017) compared for different years the foreign value-added shares of UNCTAD-Eora and OECD TiVA databases and concluded that: “Overall, the scatterplots reassure us that Eora and the OECD-WTO TiVA statistics are generally consistent with one another. Given this, we can feel somewhat more comfortable using Eora for countries for which the OECD-WTO TiVA data are not available” (Aslam, Novta and Rodrigues Bastos, 2017[44]).