Understanding levels of consumer detriment from specific financial products and services offered in different market sectors can help policymakers, regulators and supervisors strengthen financial consumer protection frameworks and address areas of highest concern. This chapter analyses products and services giving rise to consumer detriment in five product markets: banking and payments, credit, insurance, investments and pensions.

Consumer Finance Risk Monitor

5. Products and services giving rise to consumer detriment

Abstract

While the previous three chapters evaluated factors that can potentially lead to harm (i.e. risks), this chapter examines the vectors (i.e. financial products and services) through which those risks transform into actual consumer detriment. The definition of consumer detriment used for this Report is consistent with the definition provided in the OECD Recommendation on Consumer Policy Decision Making [OECD/LEGAL/0403]. The definition is as follows:

the harm or loss that consumers experience, when, for example, i) they are misled by unfair market practices into making purchases of goods or services that they would not have otherwise made; ii) they pay more than what they would have, had they been better informed, iii) they suffer from unfair contract terms or iv) the goods and services that they purchase do not conform to their expectations with respect to delivery or performance.

Understanding levels of consumer detriment from specific financial products and services offered in different market sectors can help policymakers, regulators and supervisors strengthen financial consumer protection frameworks and address areas of highest concern. For each of the five market sectors (banking and payments, credit, insurance, investments, and pensions) jurisdictions were asked to select three products or services giving rise to the most significant consumer detriment in 2022 and indicate whether such detriment was expected to increase, decrease or stay the same in 2023.

Because quantifying consumer detriment can be challenging and definitions vary across jurisdictions, the reporting template was not overly prescriptive in how it expected jurisdictions to rank products and services. Instead, responding authorities were free to base their assessment on their knowledge of their own markets, which may be informed by consumer research, past supervisory actions, thematic reviews or complaints data, among other sources.

5.1. Banking and payments

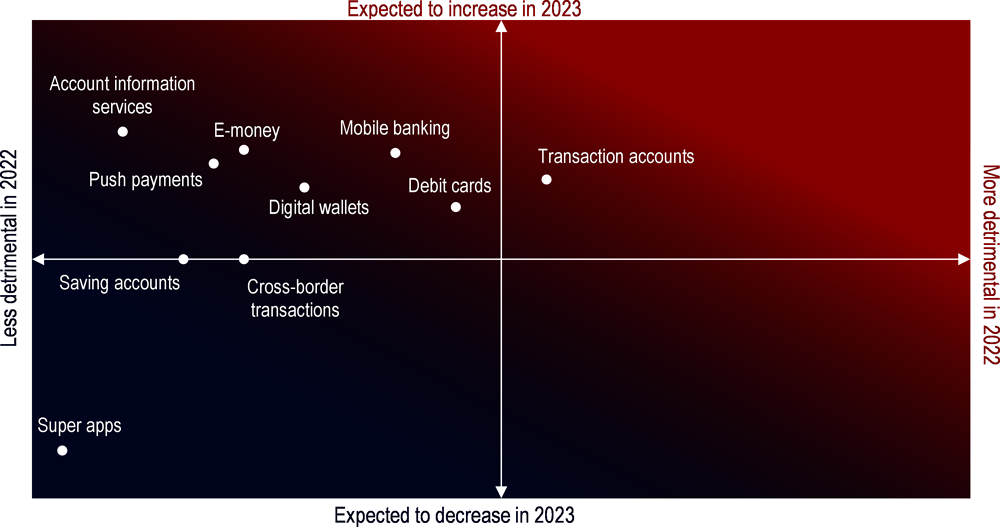

Figure 5.1 presents banking and payment products positioned on a heatmap according to the level of consumer detriment they caused in 2022 and jurisdictions’ expectations for how this level would change in 2023. The following key findings emerge:

Transaction accounts and debit cards gave rise to the greatest consumer detriment in the banking and payments sector in 2022, primarily due to harms linked to financial scams and frauds and blocked accounts. These products were selected by 55 and 45% of respondents, respectively.1

Mobile banking and digital wallets also caused concern. On average, the detriment arising from these products was expected to increase over the course of 2023 as the adoption of new digital technology may increase consumers’ exposure to financial scams and frauds.

Cross-border transactions, E-money, push payments, savings accounts and account information services gave rise to relatively less consumer detriment in 2022; however, detriment from account information services, E-money and push payments was expected to increase in 2023.

Harm to consumers from super apps – applications that combine multiple financial and non-financial services in one platform – was expected to decrease in 2023.

Figure 5.1. Products and services giving rise to consumer detriment in the banking sector

Note: The x-axis (horizontal) presents responses to questions asking for the top three products and services that gave rise to consumer detriment in the sector in 2022. The y-axis (vertical) presents responses to a follow-up question asking whether jurisdictions anticipate the detriment arising from the selected product would increase, stay the same or decrease in 2023.

Products and services are placed along the x-axis (horizontal) according to how frequently they were selected by respondents (more frequently selected products are farther to the right). The intersection of the y-axis represents the median number of responses per product, i.e., products to the right of the y-axis were selected more frequently than the median. The relative positioning of the products and services along the y-axis is determined by calculating an average of responses for the corresponding product or service (“increasing”, “staying the same” or “decreasing”).

Source: OECD Consumer Finance Risk Monitor Reporting Template 2023

When asked to describe the consumer detriment that could arise from banking and payment products, jurisdictions reported concerns about scams and frauds that arise from banking and payment transactions conducted online. According to a survey conducted in 2021 by the National Bank of Rwanda, around one in five Rwandan consumers reported being a victim of financial fraud. Canada, Indonesia, Mozambique, Peru, Rwanda and Spain noted that fraudsters target transaction accounts and that digital products and services come with higher potential risk of fraud to consumers. In Bulgaria, nearly a quarter of the complaints received by the Bulgarian National Bank concerned unauthorised payment transactions. Such scams and frauds include phishing and social engineering attacks.

Challenges can also arise related to blocked or frozen accounts. For example, in Thailand, contract terms may stipulate that financial service providers can freeze a customer’s account if it is suspected of fraud, illegal activity, or misuse. This may, however, potentially harm consumers if there was no such activity and the freeze continues for a long period of time. Portugal noted that one of the most complained matters regarding deposits, including current accounts, relates to constraints imposed by the institution on the management of the account, which could include restrictions on access to the account, in particular resulting from the unavailability of digital channels, or blocking of current accounts. The United Kingdom described a similar phenomenon relating to firms freezing customer accounts unfairly due to a misapplication of financial crime controls. Other situations of potential detriment for the consumer include delays in closing accounts, which jeopardises consumer mobility, and difficulties opening accounts, which hampers consumers’ access to indispensable banking products.

Regarding cross-border payments, Australia noted that a lack of transparency in the cost of conducting cross-border payments can be detrimental to consumers if they lack information and understanding about the fees on such payments. In Lithuania, intermediaries (correspondent banks) that participate and facilitate cross-border transactions often apply commission fees, which consumers are not made aware of before initiating the payment transaction.

5.2. Credit

Within the reporting template, the definition of credit included a range of products and services, some of which may not be legally classified as credit in certain jurisdictions but nevertheless share many of the characteristics that could be reasonably understood as credit. Such products include traditional offerings like mortgages, personal loans, credit cards and car loans. It also includes less traditional forms of credit such as payday lending, peer-to-peer lending, salary advance schemes, Buy Now Pay Later and overdraft facilities.

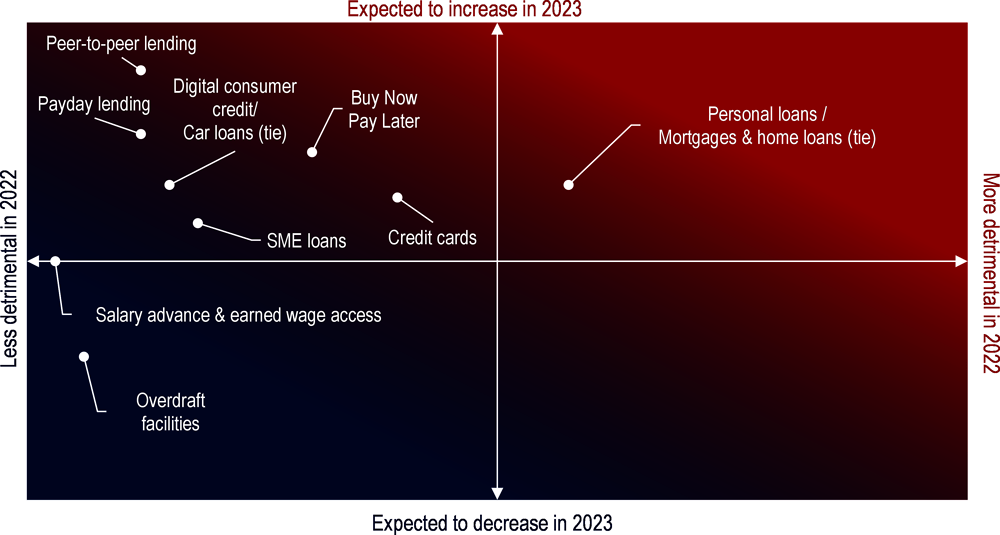

Figure 5.2 presents credit products and services according to the consumer detriment they caused in 2022 and jurisdictions’ expectations for 2023.

Mortgages/home loans and personal loans gave rise to the greatest consumer detriment in the credit sector in 2022; both of which were selected by 58% of respondents.2

Credit cards were cited by 39% of respondents and Buy Now Pay Later by 30%. On average, the detriment arising from these products was expected to increase over the course of 2023.

Relative to other product categories, peer-to-peer lending received the most pessimistic outlook for 2023, while the detriment arising from overdraft facilities received the least pessimistic outlook.

Figure 5.2. Products and services giving rise to consumer detriment in the credit sector

Note: The x-axis (horizontal) presents responses to questions asking for the top three products and services that gave rise to consumer detriment in the sector in 2022. The y-axis (vertical) presents responses to a follow-up question asking whether jurisdictions anticipate the detriment arising from the selected product would increase, stay the same or decrease in 2023.

Source: OECD Consumer Finance Risk Monitor Reporting Template 2023.

Regarding personal loans, consumer detriment may arise from misprocessed transactions, improper charges including unfair penalties or restrictions for earlier payback, and inadequate disclosures about the terms and conditions. Hungary noted the high cost of services in doorstep loans, a type of personal loan where the cash loan is delivered and collected at the home of the consumer. Indonesia, Italy and Canada cited debt collection practices as a cause for concern.

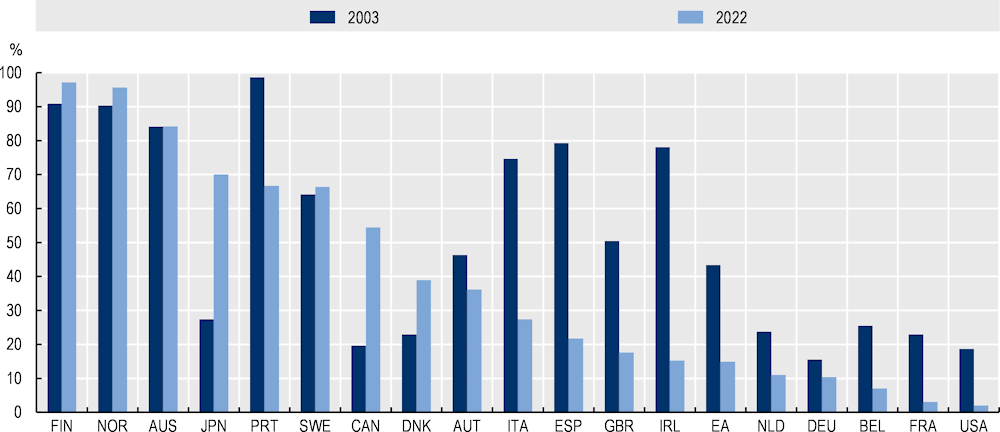

Interest rate hikes affected adjustable-rate mortgages held by consumers in many jurisdictions, thus increasing the debt burden on consumers and their household expenses. As shown in Figure 5.3, the share of adjustable-rate mortgages as a percentage of all mortgages issued in 2022 varied widely across jurisdictions, from 2% in the United States to 97% in Finland. This heterogeneity can be explained by demand-side factors (e.g. borrowers’ preferences), supply-side factors (e.g. the types of funding available to mortgage issuers) and regulation (Albertazzi, Fringuellotti and Ongena, 2019[1]). Figure 5.3 also contrasts this proportion against mortgages issued in 2003, showing that the prevalence of adjustable-rate mortgages within jurisdictions has evolved over time, significantly increasing in Japan and Canada, for example, while falling in Italy, Spain and Ireland. The decline in the share of adjustable-rate mortgages in OECD countries results partly from the narrowing spread between fixed and variable rates (van Hoenselaar et al., 2021[2]).

Figure 5.3. Share of adjustable-rate mortgages issued in 2003 and 2022, in selected housing markets

Note: Adjustable-rate mortgage loans are new loans issued at variable rate or with an initial rate fixed for a period of up to 1 year. Due to limited data availability, the light blue bars for Norway and Sweden refer to 2006. For the United Kingdom, Canada and Australia the light blue bars respectively refer to 2008, 2013 and 2019. Dark blue bars refer to 2022 or to the latest available data.

Source: ECB; Financial Conduct Authority; Japan Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism; Norges Bank; Federal Housing Finance Agency; Bank of Canada; Australian Bureau of Statistics, and OECD calculations published in OECD (2022[3]), OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2022 Issue 2.

The Financial Consumer Agency of Canada noted data points and anecdotal examples suggesting that variable rate mortgages with fixed payments were most likely sold to consumers who did not understand the product or would have not qualified for other types of mortgages at the time of application. FCAC concluded that this specific product, although attractive in a low interest rate setting, offers poor value to consumers when interest rates start rising rapidly. To address this growing concern and the increase of financial hardship consumers are facing, FCAC published industry guidelines in 2023 on its expectations for how banks should handle existing consumer mortgage loans in exceptional circumstances (Financial Consumer Agency of Canada, 2023[4]).

In Luxembourg, 40% of outstanding mortgage loans have variable interest rates, meaning that consumers who hold these mortgages in their jurisdictions are at increased risk of vulnerability with interest rate hikes. The Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier (CSSF) therefore has requested banks to perform an interest rate sensitivity analysis at loan origination to improve consumer protection in the future. Similarly in Slovak Republic, lenders are required to “stress test” applications in line with the National Bank of the Slovak Republic’s regulatory limit on the debt-to-income ratio of loan applicants. Portugal approved in 2022 a set of temporary rules to mitigate the impact of the increase of interest rates in mortgage credit contracts with variable interest rates and to assist borrowers at risk of default due to increased rates. Under these measures, lenders are bound to carry out an assessment of the borrower’s capacity. In case the borrower's debt service-to-income ratio is significantly affected by the increase of interest rate, lenders must propose various solutions including the consolidation of several credit agreements or a new credit agreement to refinance the debt, an extension of the repayment period, the application of a grace period, the deferral of part of the capital or a temporary reduction in the interest rate. Portuguese authorities also approved the temporary suspension of the early repayment fee for variable rate mortgage credit regardless of the amount of the outstanding debt. Additional temporary measures were introduced in October 2023 through which certain homeowners can request that their bank reduce the loan’s underlying benchmark (six-month Euribor) by 30% over two years, deferring principal to a later stage.

The United States also noted that interest rate hikes coupled with price increases in the auto sector led to a rapid increase in the size of auto loans, changes that put pressure on many consumers’ budgets.

A number of jurisdictions noted that Buy Now Pay Later (BNPL) schemes risk over-indebtedness for consumers, who may not always understand the risks they may incur when using this service. More information about BNPL schemes is provided in Box 5.1.

Box 5.1. Buy Now Pay Later

Buy Now Pay Later has emerged in recent years as a popular method of making purchases and paying in instalments. In some ways it is simply a modern iteration of the type of consumer lending that has existed for years, growing notably in the 19th century when it helped bring relatively expensive consumer goods (e.g. furniture, farm equipment, and sewing machines) within reach of people on limited incomes (Harvard Business School, n.d.[5]). More recently, however, BNPL has emerged as a distinct financial product, driven in part by increased digitalisation. Today, BNPL is a global phenomenon, a widely used and easily accessible financial service for consumers offered by specialised entities such as Afterpay, Klarna and Affirm as well as BigTechs including Apple (via MasterCard and Goldman Sachs) and Amazon (via Affirm). Uptake of the product increased dramatically in recent years in many jurisdictions. In the United States, the volume of BNPL loans increased twelvefold between 2019 and 2021 (Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, 2022[6]). In the United Kingdom, the value of transactions using BNPL nearly quadrupled between January and December 2020 (Financial Conduct Authority, 2021[7]), with a 2023 survey revealing that 27% of UK adults had used such products in the prior six months (Financial Conduct Authority, 2023[8]). Globally, the BNPL market is estimated to continue growing at a compound annual growth rate of 26.1% from 2023 to 2030, when it is expected to reach nearly USD 40 billion (Grand View Research, 2022[9]).

While BNPL products are clearly popular with consumers and appear to be filling a need in the market, policymakers, regulators and supervisors around the world are increasingly concerned about the potential consumer harms arising from BNPL products and the limitations of existing policy frameworks to adequately protect consumers from over-commitment in terms of their repayment obligations.

Indeed, of the 43 jurisdictions participating in the 2023 OECD Consumer Finance Risk Monitor, nearly one in three mentioned BNPL as an area of concern or of future regulatory action.

Jurisdictions are particularly concerned about the increasing use of BNPL among consumers who may already be struggling financially due to rising inflation, depressed incomes and increasing interest rates, therefore increasing the risk of over-indebtedness. The Central Bank of Malaysia, for example, expressed concerns that consumers may be more susceptible to unfair treatment and accumulation of excessive debt due to the proliferation of credit providers who sometimes fall outside the regulator’s reach. In the current economic context, the relative ease of access to BNPL facilities can place users at a higher risk of spending beyond their means, without considering their ability to repay the full amount. The Netherlands shared this concern, noting that while the risk does not pertain to most users engaging with the product, the most significant danger posed by BNPL is its potential contribution to over-indebtedness for consumers in an already vulnerable financial situation. According to research from the United States, BNPL users have lower credit scores and are more likely to be in financial distress than other consumers.

Authorities are also concerned about the lack of transparency regarding fees and charges, particularly for late payments. The Central Bank of Malaysia, citing anecdotal evidence among selected larger BNPL players in the market, noted an increasing trend in missed repayments, suggesting that such risks may be rising. Authorities from Germany and Ireland expressed concerns about consumers, especially youth, not understanding the underlying construct and potential repercussions of using BNPL products. Beyond the lack of transparency and disclosure of information to consumers, authorities from Italy, the Netherlands and Portugal further cited poor creditworthiness assessments as an additional risk, as well as aggressive marketing that promotes impulse buying. In addition to the lack of robust creditworthiness assessments, the use of BNPL products does not appear on credit reports in the United States, raising potential systemic risk concerns.

BNPL facilities are not always regulated or subject to the same rules as other forms of credit due to certain features of the product (e.g. amount borrowed, number of instalments, lack of interest charges). In some jurisdictions, the regulatory framework for credit – and the associated protections – only applies in certain cases, depending on the specific design of the service. Notwithstanding the legal status of BNPL vis-à-vis jurisdictional definitions of credit, the risks posed to consumers are much the same.

To respond to the growth of BNPL and the related risks, policymakers and supervisory authorities have launched a range of actions and initiatives, including consumer research, awareness campaigns, self-regulation, and the introduction of new legislation and regulation.

In May 2023, the Minister for Financial Services of Australia announced intentions to regulate BNPL as a form of credit under the National Consumer Credit Protection Act 2009 (Credit Act). This regulation would include new requirements for BNPL providers, including product disclosures, affordability assessments, fee caps, credit records and licensing obligations among others.

In 2023, Finland amended its Consumer Protection Act which, among other things, introduced stipulations regarding the presentation of available payment methods online. The amendments prohibit online retailers from setting any payment method as a default choice. Further, the amended Act requires retailers to order the presentation of payment methods with payments-in-full first (i.e. immediate debits), followed by card payments and mobile payments second, and lastly any methods that involve deferrals, instalments or applying for credit (which would include BNPL).

Consumer research by the Competition and Consumer Protection Commission in Ireland found that ‘not borrowing for daily expenses’ is one of the two key behaviours that directly affects financial well-being. Given BNPL’s availability, how convenient it is and how tempting it is for consumers, Irish authorities are concerned that this will have a negative impact on consumers financial well-being. BNPL is regulated by the Central Bank, but agreements under EUR 500 (Euro area euros) and certain agreements over EUR 500, where interest is not charged, are not reported into the Central Credit Register, which means that other lenders may not have a full picture of the debt a consumer has when they assess their creditworthiness and could lead to over-indebtedness. The Competition and Consumer Protection Commission of Ireland launched a BNPL campaign targeting younger consumers aged 18 to 35. It created two videos, one which explained BNPL to consumers and another focused on the potential for hidden costs with this type of credit arrangement. It used the main social media platforms to promote the videos, with the addition of Snapchat and TikTok, to reach the target audience.

The Bank of Italy undertook an in-depth evaluation on BNPL schemes, noting that a common BNPL scheme in Italy is one where the deferment is formally granted by the seller, who immediately after (or even at the same time as the transaction) assigns the credit to a specialised intermediary, based on former agreements. Bank of Italy subsequently issued a public warning to increase overall awareness among consumers on the risks they may incur in relation to such credit facilities (e.g. exposure to over-indebtedness due to poor creditworthiness assessment procedures). The communication drew consumers' attention to potential risks and to the safeguards provided by the regulatory framework protecting bank customers.

In the Netherlands, the Autoriteit Financiele Markten (AFM) published a large study on BNPL in 2022, noting that while the product may provide flexibility for consumers and increase sales for online shops, it also posed risks for financially vulnerable consumers and contribute to debt accumulation. Further, it could lead to debt habituation, which they defined as the normalisation of buying on credit. The study emphasised that BNPL providers were not obligated to perform robust creditworthiness checks. In conclusion, the AFM voiced its support for proposals to revise the European Consumer Credit Directive, which would introduce various requirements for BNPL providers and allow AFM to supervise the provision of such products.

The Banco de Portugal reported closely monitoring the expansion of BNPL products in the consumer credit sector, anticipating over-indebtedness and default. Portugal also noted that while consumer credit under EUR 200 was not subject to regulatory requirements, the revision of the EU Consumer Credit Directive will bring BNPL products within the scope of the Directive, which will be reflected in the Portuguese framework.

The Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) determined that an industry code (as opposed to regulations) would be a risk-proportionate response to BNPL-related developments, which remains a very small segment compared to other means of consumer payments. The code, launched in November 2022, seeks to protect consumers’ interests by formalising safeguards such as no compounding interest, a cap on late fees, clear disclosures and fair marketing, suspension of account upon customer delinquency and a requirement for BNPL firms to conduct additional creditworthiness assessments before exceeding a stipulated credit cap with the provider. MAS noted that they would continue to monitor the industry’s implementation of the safeguards set out in the Code and continue to work with the industry to mitigate the risk of consumer over-indebtedness.

In February 2021, the United Kingdom government announced its intention to regulate interest-free BNPL products. The government consulted on policy options to deliver a proportionate approach to regulation in October 2021, followed by a consultation response in June 2022. The government subsequently consulted on a proposed draft legislation that would bring BNPL into Financial Conduct Authority regulation.

The policy and regulatory challenges raised by BNPL will feed into and be reflected in the upcoming assessment of the OECD Recommendation on Consumer Protection in the field of Consumer Credit [OECD/LEGAL/0453], which is the only global standard on consumer credit. The Recommendation, first adopted in 1977 and updated in 2019, sets out high-level recommendations for Adherents to take measures relating to the protection of consumers in the context of consumer credit transactions. The G20/OECD Task Force on Financial Consumer Protection has responsibility for overseeing the implementation of the Recommendation and ensuring that it remains up to date. Given the importance of BNPL on the policy agenda of regulators globally, the review of the Recommendation will necessarily include a close assessment of any modifications that the BNPL trend may require.

5.3. Insurance

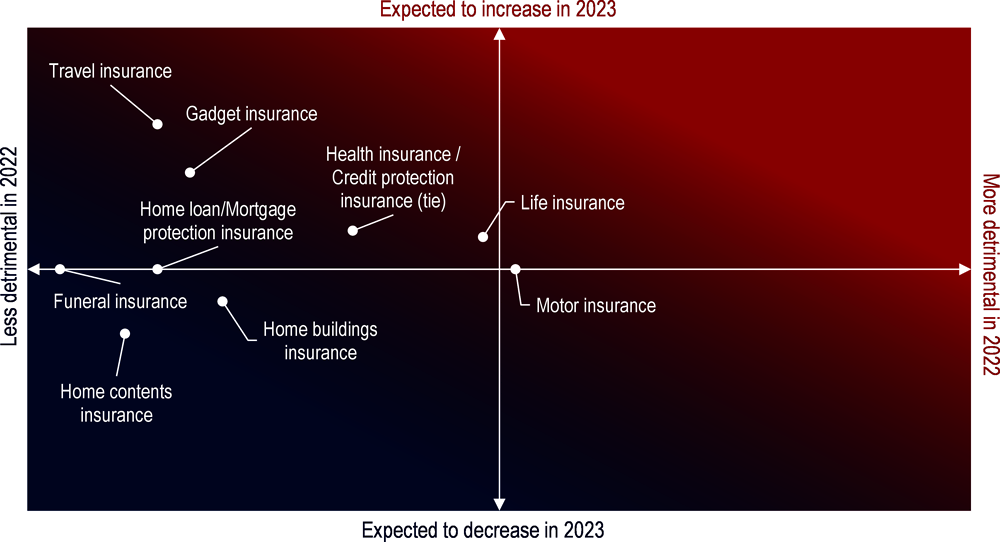

Figure 5.4 presents insurance products and services according to the consumer detriment they caused in 2022 and jurisdictions’ expectations for 2023.

Selected by over half of respondents, motor and life insurance gave rise to the greatest consumer detriment in the insurance sector in 2022.3

Credit protection and health insurance were also cited by 36% of respondents.

The detriment arising from life, credit protection and health insurance was expected to increase over the course of 2023, while harms from motor insurance were expected to remain the same.

Relatively few jurisdictions ranked travel and gadget insurance among the top products causing detriment in 2022; however, jurisdictions anticipated that the harm arising from travel and gadget insurance would increase in 2023.

Figure 5.4. Products and services giving rise to consumer detriment in the insurance sector

Note: The x-axis (horizontal) presents responses to questions asking for the top three products and services that gave rise to consumer detriment in the sector in 2022. The y-axis (vertical) presents responses to a follow-up question asking whether jurisdictions anticipate the detriment arising from the selected product would increase, stay the same or decrease in 2023.

Source: OECD Consumer Finance Risk Monitor Reporting Template 2023.

Additionally, jurisdictions mentioned certain business practices, such as bundling or tying products, which in certain instances risk causing consumer detriment in the insurance sector. Austria, Luxembourg, and Romania noted that the business models for the sale of insurance products can often be the main cause of consumer detriment. Such business models may be designed to generate revenue in the form of commission payments for the party distributing these products, which can result in products being sold that offer limited value to the consumer. In addition, as noted by South Africa, products are often bundled or linked with other products which may lead to confusion or misunderstanding among consumers if there are not effective disclosures and transparency about the products.

In an example from the United Kingdom, Guaranteed Asset Protection (GAP) insurance is an add-on insurance product sold by non-regulated entities alongside the purchase of another product (generally motor vehicles). In its research into the sector, the Financial Conduct Authority found that it was characterised by high levels of commissions paid to the distributors, alongside extremely low claims frequencies. In France, affinity or add-on insurance products have given rise to numerous complaints from consumers. In response, the Financial Sector Advisory Committee unanimously adopted an opinion to strengthen consumer protection relating to this product. The opinion addresses the collection of the policyholder’s consent, provision of annual information and clarification that the consumer is signing an insurance contract and not a legal or commercial warranty.

Unit-linked products can lead to much confusion or misinterpretation, for instance consumers who purchase investment-linked policies (ILPs) may not adequately understand the product features. Additionally, credit protection insurance (CPI) may cause consumer detriment when the cost of bundled CPI is higher than what the actual loss ratio would suggest. Consumers are also sometimes unaware that they have purchased CPI. In Europe, tying (where banks require borrowers to purchase a CPI when taking out a loan) is generally prohibited under the Mortgage Credit Directive, but a thematic review conducted by EIOPA revealed that such practices remain widespread (EIOPA, 2022[10]). In Peru, financial institutions are similarly forbidden to force clients to purchase credit life insurance offered by them, and insurance companies are forbidden to bundle credit life insurance with additional coverage. However, in the digital environment, new concerning practices have emerged, particularly with regard to credit or debit card insurance (CCI), where insurance providers consider the fraud coverage in digital/online environments as an additional coverage with an extra charge; a product design that the SBS notes is not aligned with the current trend of increasing digital transactions. In Chile, the practice of bundling credit protection insurance products with consumer credit is widespread. While not always an unfair practice, it can often cause consumer detriment, especially if consumers purchase insurance that they do not want or need. In 2021, the Chilean Consumer Protection Authority (SERNAC) entered into a settlement with several insurance companies regarding mis-selling of insurance with retail store credit cards that consumers were not aware of purchasing.

Jurisdictions also mentioned that for many of these products, there is uncertainty or confusion around what is covered and what is not, especially with regards to gadget insurance and travel insurance. Jurisdictions also noted high levels of dissatisfaction among consumers generally regarding claims compensations and claims handling and that delays in compensation could be particularly pronounced with motor insurance. In the Netherlands, consumer detriment also arises from uninsurable losses due to climate change and natural hazards (see Box 2.1 in Chapter 2 for more information on natural hazards).

5.4. Investments

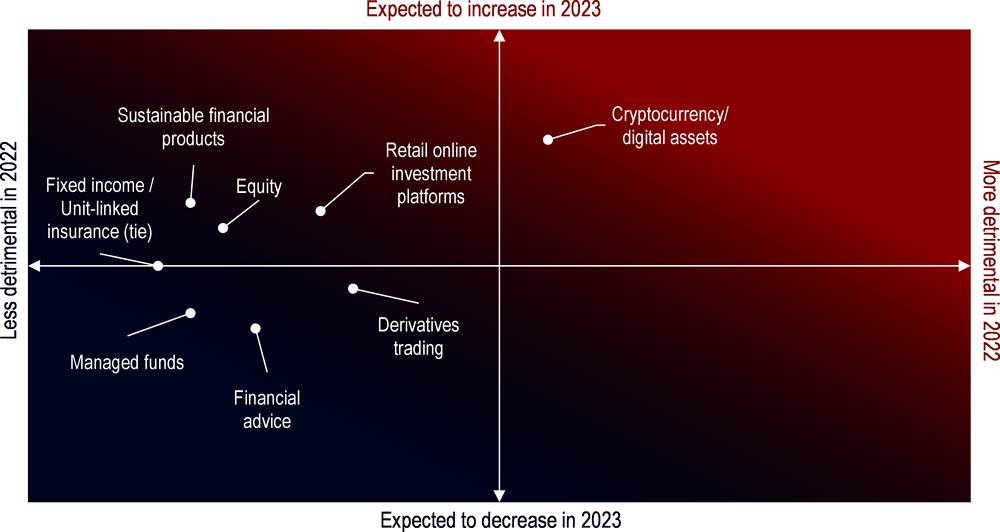

The reporting template presented a range of products and services under the category of investments. Examples include managed funds, equity, fixed income products, derivatives trading, financial advice, sustainable finance, and retail/self-direct online investment platforms. Digital assets, including crypto-assets, were included as a type of investment product, even though they may not be treated as regulated investments in many jurisdictions. Figure 5.5 presents investments products and services according to the consumer detriment they caused in 2022 and jurisdictions’ expectations for 2023:

More than half of respondents selected cryptocurrencies and digital assets as giving rise to the greatest consumer detriment in the investments sector in 2022, whereas the next most frequently selected product and service (derivatives trading) was only selected by around a third of respondents.4

Overall, jurisdictions expected that the harm from cryptocurrencies and digital assets would increase in 2023 along with detriment from retail/self-directed online investments, equity and sustainable financial products.

Detriment from fixed income and unit-linked insurance was expected to remain the same in 2023.

Consumer detriment arising from derivatives trading, financial advisory services and managed funds was expected to decrease in 2023.

Figure 5.5. Products and services giving rise to consumer detriment in the investments sector

Note: The x-axis (horizontal) presents responses to questions asking for the top three products and services that gave rise to consumer detriment in the sector in 2022. The y-axis (vertical) presents responses to a follow-up question asking whether jurisdictions anticipate the detriment arising from the selected product would increase, stay the same or decrease in 2023.

Source: OECD Consumer Finance Risk Monitor Reporting Template 2023.

Jurisdictions indicated that digital assets, including crypto-assets, give rise to consumer detriment given their highly volatile nature. In some jurisdictions, crypto-asset activities are unregulated, though this is changing (see Box 5.2 below for more detail); in other jurisdictions, crypto-asset activities are conducted in non-compliance with applicable domestic regulations (OECD, 2022[11]; OECD, 2022[12]). Research in the Netherlands shows that 1 in 10 crypto-asset users engage with high-risk leveraged strategies involving crypto-assets. In Ontario, Canada, retail investor participation in capital markets rapidly grew during the pandemic; for some self-directed investors, a desire for returns in the face of challenging and uncertain macro-economic conditions may have led to more speculative investments in crypto-assets. Furthermore, retail investors face risks connected with trading decisions based on informal recommendations via social networks and unregulated online platforms from outside Canada, which may provide misleading information or information without proper risk warnings.

Box 5.2. Recent developments in regulating crypto-assets

In the last several years, jurisdictions around the world have clarified, strengthened or introduced regulations pertaining to crypto-assets. Four examples are set out below.

Japan: Three successive legal reforms

Japan first began reforming their crypto-asset regulatory framework in 2016, when a registration system was introduced for crypto-asset exchange service providers. The system requires identity verification upon account openings and uses a framework for user protection including minimum capital requirements, disclosure and segregation of assets. In 2019, the Payment Services Act and the Financial Instruments and Exchange Act were amended to include crypto-asset derivative transactions in the scope of regulation and to strengthen user protection requirements, including advertising. In 2022, the third legal reform amended the Banking Act, the Payment Services Act and the Trust Business Act to introduce a regulatory framework with banks, fund transfer service providers and trust companies as issuers of stablecoins. The reforms also introduced a registration system for stablecoin intermediaries (Financial Services Agency, 2022[13]).

South Africa: Declaration of a Crypto-Asset as a Financial Product

In October 2022, the Financial Sector Conduct Authority of South Africa published in the Government Gazette and on its website a Declaration of a Crypto-Asset as a Financial Product (Declaration) under the Financial Advisory and Intermediary Services Act, 2002 (Act No. 37 of 2002) (FAIS Act) (Financial Sector Conduct Authority, 2022[14]). The FSCA also released a Policy Document providing clarity on the effect of the Declaration, including transitional provisions, and the approach the FSCA would take in establishing a regulatory and licensing framework that would be applicable to Financial Services Providers (FSPs) that provide financial services in relation to crypto-assets. The declaration brought providers of financial services in relation to crypto-assets within the FSCA’s regulatory jurisdiction.

European Union: Markets in Crypto-assets (MiCA) Regulation

The Markets in Crypto-Assets Regulation (MiCA) introduced market rules for crypto-assets in the European Union. The regulation, which entered into force in June 2023 and will be applicable from 30 December 2024 onwards, covers crypto-assets that were not regulated by existing financial services legislation. Key provisions for those issuing and trading crypto-assets address transparency, disclosure, authorisation and supervision of transactions. The new legal framework will support market integrity and financial stability by regulating public offers of crypto-assets and by ensuring consumers are better informed about their associated risks (European Parliament and Council of the European Union, 2023[15]).

Financial Stability Board (FSB) Global Regulatory Framework for Crypto-asset Activities and Global Stablecoins

In July of 2023 the FSB published its Global Regulatory Framework for Crypto-asset Activities to promote consistency and co-ordination of regulatory and supervisory approaches regarding crypto-assets. This Framework comprises two sets of recommendations. The first consists of high-level recommendations for the regulation, supervision and oversight of crypto-asset activities, and the second concerns recommendations for the regulation, supervision and oversight of global stablecoin arrangements. These recommendations are based on the principle of “same activity, same risk, same regulation” to promote high-level, flexible and technology-neutral recommendations to ensure crypto-asset activities and stablecoins are subject to consistent and comprehensive regulation corresponding to the risks they pose, while also supporting innovation from technological advances.

In addition to crypto-assets, Italy noted that potential detriment arises from the complexity and riskiness of derivatives trading that consumers may not easily understand. In terms of financial advice, countries and jurisdictions point to the average consumer getting investment “advice” from social media and not professional financial advisors. Indeed, a survey of investors in Brazil (average age of 32) revealed that around 75% of respondents began investing based on information from YouTube channels and influencers (Comissão de Valores Mobiliários, 2023[16]). Slovak Republic noted that this risk may be exacerbated among consumers with low levels of financial literacy.

Portugal noted that investors seemed to be making their own investments via self-directed platforms, often boosted by advice from digital influencers (who sometimes lack proper financial literacy). Simultaneously, the so-called zero commission platforms generate a lot of interest, especially with new investors who do not fully realise that “there are no free lunches”, and therefore are paying commissions indirectly with the additional risk of derailing their investment objectives.

Australia, Chile, Italy, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia and Spain also mentioned that as consumer demand for sustainable finance grows, there is a potential greenwashing risk as marketing of these new products can be misleading to potential investors.

5.5. Pensions

Figure 5.6 presents pensions products and services according to the consumer detriment they caused in 2022 and jurisdictions’ expectations for 2023.

Benefits payments and management of assets gave rise to the greatest consumer detriment in the pensions sector in 2022.

The harm arising from issues related to benefits payments, however, was expected to decrease in 2023.

On the contrary, jurisdictions expected that harms related to financial advice and the provision of information would stay the same or increase in 2023.

Figure 5.6. Products and services giving rise to consumer detriment in the pensions sector

Note: The x-axis (horizontal) presents responses to questions asking for the top three products and services that gave rise to consumer detriment in the sector in 2022. The y-axis (vertical) presents responses to a follow-up question asking whether jurisdictions anticipate the detriment arising from the selected product would increase, stay the same or decrease in 2023.

Source: OECD Consumer Finance Risk Monitor Reporting Template 2023.

Regarding benefits payments, many jurisdictions cited delays in payments and concerns that payments from Defined Benefit schemes would be low unless adjusted for inflation. In terms of management of assets, Hong Kong (China) and Rwanda noted that some consumers feel they do not have adequate knowledge or experience on pension funds management; furthermore, consumers who do not have much investment knowledge or experience may not be able to choose products that best match their outcome expectations and risk appetites (OECD, 2020[17]). Sweden described how commission structures may also create incentives for the distributor to persuade consumers to purchase a product with a high commission, even if the product is not suitable for that customer.

Jurisdictions also noted how increased market volatility had led some pension funds to underperform; people were also permitted to make early withdrawals, which then could cause problems later when they retire. In Hungary, the annual returns in 2022 fell short of the defined Reference Yields. Assets earmarked for retirement fell in most OECD countries in 2022, with the value of these plans falling by 14% compared to 2021 (OECD, 2023[18]) – the largest decrease since the 2008 global financial crisis. Outside of the OECD, pension assets rose in 27 of 40 jurisdictions reporting data to the OECD, with an aggregate growth of 3.8%.

References

[1] Albertazzi, U., F. Fringuellotti and S. Ongena (2019), “Fixed rate versus adjustable rate mortgages: evidence from euro area banks”, No. 2322, European Central Bank, https://doi.org/10.2866/895495.

[16] Comissão de Valores Mobiliários (2023), CVM divulga estudo sobre possível regulamentação envolvendo influenciadores digitais e o mercado de capitais — Comissão de Valores Mobiliários, https://www.gov.br/cvm/pt-br/assuntos/noticias/cvm-divulga-estudo-sobre-possivel-regulamentacao-envolvendo-influenciadores-digitais-e-o-mercado-de-capitais (accessed on 10 August 2023).

[6] Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (2022), Buy Now, Pay Later: Market trends and consumer impacts, https://s3.amazonaws.com/files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_buy-now-pay-later-market-trends-consumer-impacts_report_2022-09.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2023).

[10] EIOPA (2022), Thematic Review on Credit Protection Insurance (CPI) sold via banks, https://www.eiopa.europa.eu/publications/thematic-review-credit-protection-insurance-cpi-sold-banks_en (accessed on 20 September 2023).

[15] European Parliament and Council of the European Union (2023), Regulation (EU) 2023/1114 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 31 May 2023 on markets in crypto-assets, and amending Regulations (EU) No 1093/2010 and (EU) No 1095/2010 and Directives 2013/36/EU and (EU) 2019/1937, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32023R1114&pk_campaign=todays_OJ&pk_source=EURLEX&pk_medium=TW&pk_keyword=Crypto%20assets&pk_content=Regulation&pk_cid=EURLEX_todaysOJ (accessed on 25 August 2023).

[8] Financial Conduct Authority (2023), Financial Lives January 2023, https://www.fca.org.uk/publications/financial-lives/financial-lives-january-2023-consumer-experience (accessed on 8 November 2023).

[7] Financial Conduct Authority (2021), The Woolard Review: A review of change and innovation in the unsecured credit market, https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/corporate/woolard-review-report.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2023).

[4] Financial Consumer Agency of Canada (2023), Guideline on Existing Consumer Mortgage Loans in Exceptional Circumstances, https://www.canada.ca/en/financial-consumer-agency/services/industry/commissioner-guidance/mortgage-loans-exceptional-circumstances.html (accessed on 27 September 2023).

[14] Financial Sector Conduct Authority (2022), “Declaration of a Crypto Asset as a Financial Product under the Financial Advisory and Intermediary Services Act, 2002”, https://www.fsca.co.za/Regulatory%20Frameworks/Temp/Policy%20Document%20supporting%20the%20Declaration%20of%20crypto%20assets%20as%20a%20financial%20product.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2023).

[13] Financial Services Agency (2022), Regulating the crypto assets landscape in Japan, https://www.fsa.go.jp/en/news/2022/20221207/01.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2023).

[9] Grand View Research (2022), Buy Now Pay Later Market Size & Share Report, 2030, https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/buy-now-pay-later-market-report (accessed on 25 August 2023).

[5] Harvard Business School (n.d.), Buy Now, Pay Later: A History of Personal Credit, Baker Library Historical Collections, https://www.library.hbs.edu/hc/credit/credit1a.html (accessed on 10 August 2023).

[18] OECD (2023), Pension Markets in Focus 2023, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/28970baf-en.

[12] OECD (2022), “Lessons from the crypto winter: DeFi versus CeFi”, OECD Business and Finance Policy Papers, No. 18, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/199edf4f-en.

[3] OECD (2022), OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2022 Issue 2, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/f6da2159-en.

[11] OECD (2022), Why Decentralised Finance (DeFi) Matters and the Policy Implications, OECD, Paris.

[17] OECD (2020), OECD Pensions Outlook 2020, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/67ede41b-en.

[2] van Hoenselaar, F. et al. (2021), “Mortgage finance across OECD countries”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1693, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/f97d7fe0-en.

Notes

← 1. Percentages are calculated based on the number of respondents who provided answers to this question (N=31).

← 2. Percentages are calculated based on the number of respondents who provided answers to this question (N=33).

← 3. Percentages are calculated based on the number of respondents who provided answers to this question (N=28)

← 4. Percentage is calculated based on the number of respondents who provided answers to this question (N=29).