Alessandro Maravalle

OECD

Aida Caldera Sánchez

OECD

Alberto González Pandiella

OECD

Alessandro Maravalle

OECD

Aida Caldera Sánchez

OECD

Alberto González Pandiella

OECD

Access to adequate housing remains challenging in Mexico as many low- and middle- income households cannot afford purchasing a house because of high housing prices and limited access to credit. An underdeveloped housing rental market and insufficient supply of social and affordable housing force many households to resort to self-build or to reside in informal settlements. Administrative fragmentation and lack of coordination across levels of government favours a disordered urban development that provokes residential segregation, with vulnerable groups often living in peripheral areas with limited access to jobs, transport and urban services. Housing policies have recently become more targeted towards low-income households, which is commendable. Expanding the range of housing subsidies and fostering the development of a social rental housing sector would be valuable additional steps to improve access to housing for low-income households. Reforming the fiscal and legal framework to encourage private investment into rental housing and promoting public-private partnerships could boost the supply of affordable housing. Tasking states with ensuring that municipalities comply with federal and state urban and housing legislation and improving coordination across, urban, housing and transport infrastructure could ease the implementation of national policies and reduce residential segregation.

The Mexican constitution recognizes since 2019 the right to a dignified house as a human right and over the past decades Mexico has successfully increased the supply of dwellings to face the increasing housing demand that came along with population growth and rising urbanisation. However, access to adequate housing remains challenging for many Mexicans. Housing supply remains insufficient to meet the demand. The quality of the housing stock has room for improvement, with a dwelling out of four being inadequate. Most low- and middle-income households cannot afford purchasing a house because of high housing prices and limited access to credit. An underdeveloped housing rental market and insufficient supply of social and affordable housing force many households to resort to self-build or to reside in informal settlements.

The design and implementation of the national housing policy is hindered by coordination issues across different agencies and level of governments, with administrative fragmentation preventing local policies from aligning with national targets. Lack of coordination between housing policy and transport and urban development planning has negative repercussions on housing location and provokes a disordered urban development that fuels spatial segregation. This has a negative impact on the well-being of millions of Mexicans, with vulnerable groups often living in peripheral areas with limited access to jobs, transport and urban services. Unfavourable living conditions in marginalised areas cause widespread house vacancy.

Public authorities recognise the importance of these challenges in shaping a new approach to housing policy in the National Housing Programme 2019-24, which sets important objectives such as improving the quality of the housing stock, assisting the production of social housing, extending finance mechanisms and promoting coordination across all levels of governments. However, Mexico should scale up its efforts to guarantee adequate housing also by promoting a more inclusive, compact, connected and sustainable urban development.

This chapter describes the main challenges that Mexico faces to increase the quality and efficiency of the housing market, strengthen the supply of social and affordable housing, ensure a better coordination of housing policy with urban development and transport policy, and discusses policy options to tackle them. It covers alternatives for amplifying the supply of social and affordable housing to address the needs of low-income households without requiring large direct public spending and involving the private sector. A housing taxation reform is discussed that might help increase the supply of private rental housing, ease access to housing finance and increase local resources for financing public investment in urban infrastructure. The chapter argues for tasking states with ensuring that municipalities comply with federal and state urban and housing law to prevent irregularities and favour the achievement of national housing policy targets. Promoting coordination between urban development and transport infrastructure planning at the metropolitan level could reduce transport infrastructure cost, and facilitate the transition towards an affordable, efficient and sustainable public transportation system.

Access to good-quality and affordable housing remains challenging for many Mexicans and too many households, especially among vulnerable groups, live in inadequate dwellings that require improvements, including in energy efficiency standards. Affordability is limited by high housing prices and restricted access to credit. In addition, the housing rental market is underdeveloped and the supply of social and affordable housing is insufficient. Against this background, in the past many families have been forced to resort to build their own homes (self-build), often without receiving technical assistance, or to reside in informal settlements. Lack of coordination among housing, urban development and transport policy leads to disordered, sprawling cities that generate socioeconomic segregation, with vulnerable groups living in settlements located in disconnected peripheral areas without access to affordable public transport.

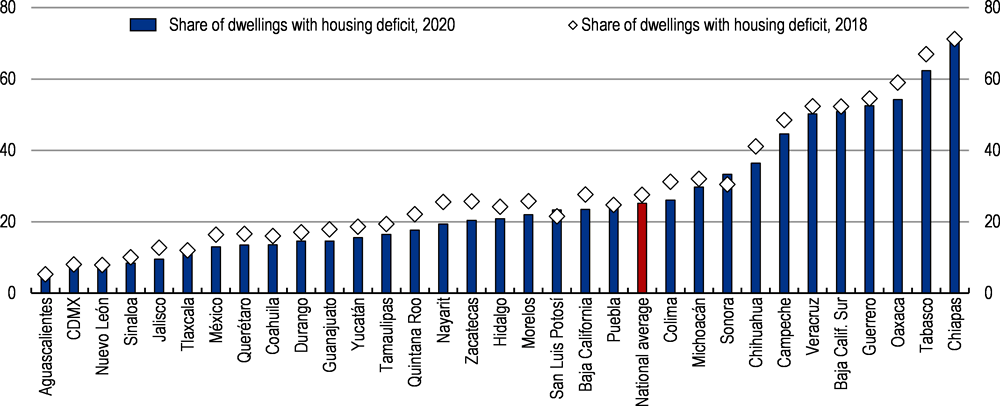

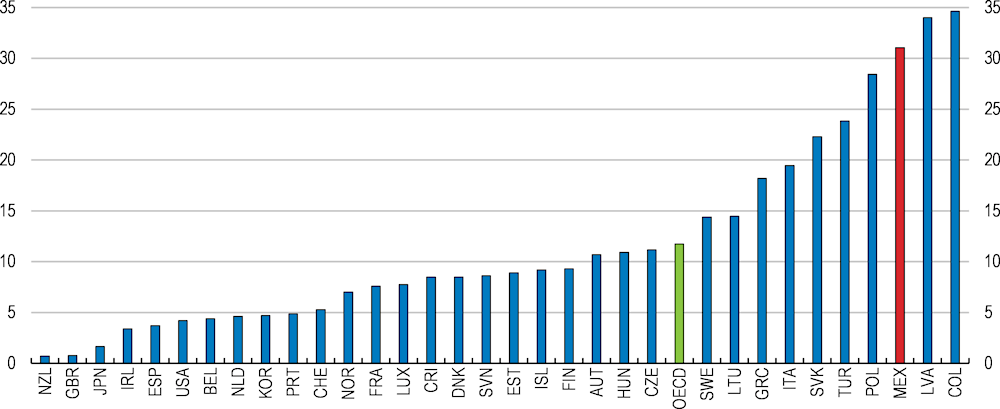

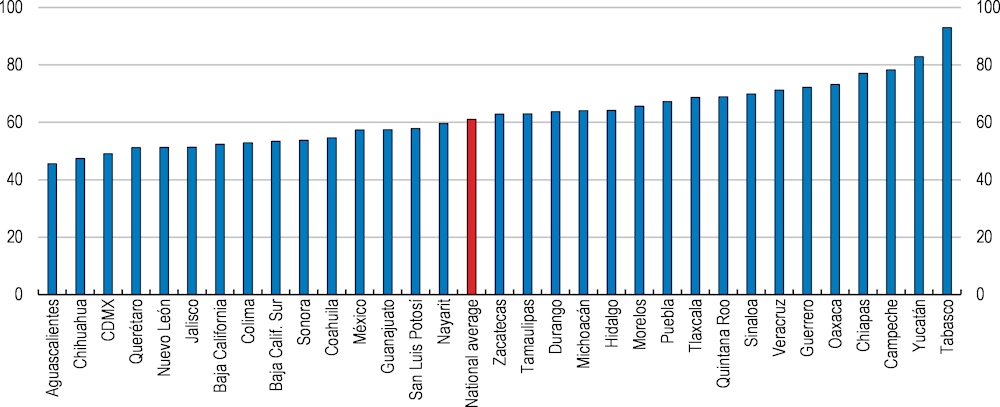

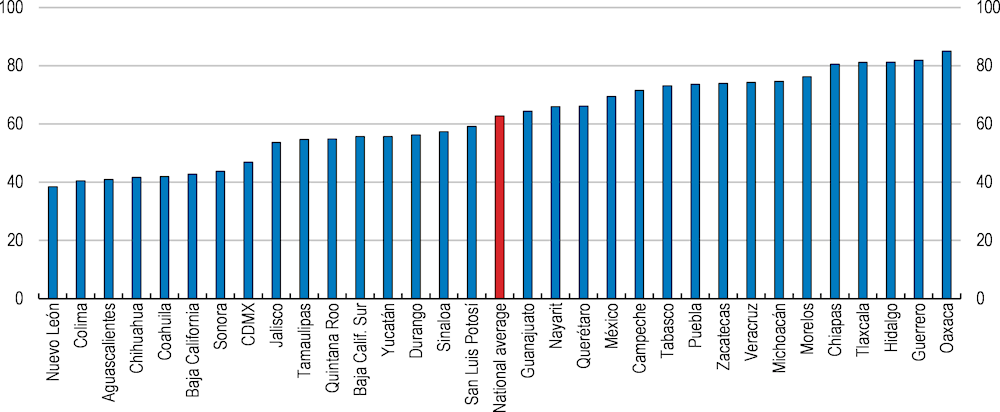

A significant part of the housing stock in Mexico is inadequate because substandard (rezago habitacional). Around one dwelling out of four has poor construction material (roof, walls or floor), is overcrowded or lacks basic facilities. In the three poorest states of the country (Chiapas, Guerrero and Oaxaca) more than half of private housing units is substandard (Figure 5.1). Mexico continues to have one of the highest rates of housing overcrowding among OECD countries (Figure 5.2), and around 40% of private dwellings have structural issues and would need home improvements (INEGI, 2020[1]) (Figure 5.3).

Inadequate housing affects disproportionally vulnerable groups (women, young, low-income, immigrant and indigenous groups) living in rural and peripheral areas (Box 5.1). In cities, around half of the population lives in areas with inadequate urban infrastructure, because of insufficient street lighting (40%) or paved road (51%) (SEDATU, 2019[2]). One sixth of the families searching for a new house are motivated by lack of urban infrastructure and inadequate characteristics of the dwelling (INEGI, 2020[1]).

Share of private dwellings with housing deficit, by state, %, 2018 and 2020

Note: Housing deficit include dwellings with no durable material for floors, walls or roof; overcrowded (more than 2.5 people per room); or lacking basic facilities (no access to running water or sanitation). “México” refers to the state of México and not to the whole country.

Source: CONAVI.

% of households, 2020 or last year available

Note: A household is considered as living in overcrowded conditions if less than one room is available in each household: for each couple in the household; for each single person aged 18 or more; for each pair of people of the same gender between 12 and 17; for each single person between 12 and 17 not included in the previous category; and for each pair of children under age 12. Rooms refer to bedrooms, living and dining rooms and, in non-European countries, also kitchens.

Source: OECD (2023), Housing overcrowding (indicator).

Share of regional private housing stock with structural problems, %, 2020

Note: Structural problems include at least one of the following issues: cracks in the walls or ceiling; deformation in door or window frames; soil subsidence; cracks or deformation in beams or pillars; water leaks or deteriorated water and drainage pipes. “México” refers to the state of México and not to the whole country.

Source: ENVI 2020.

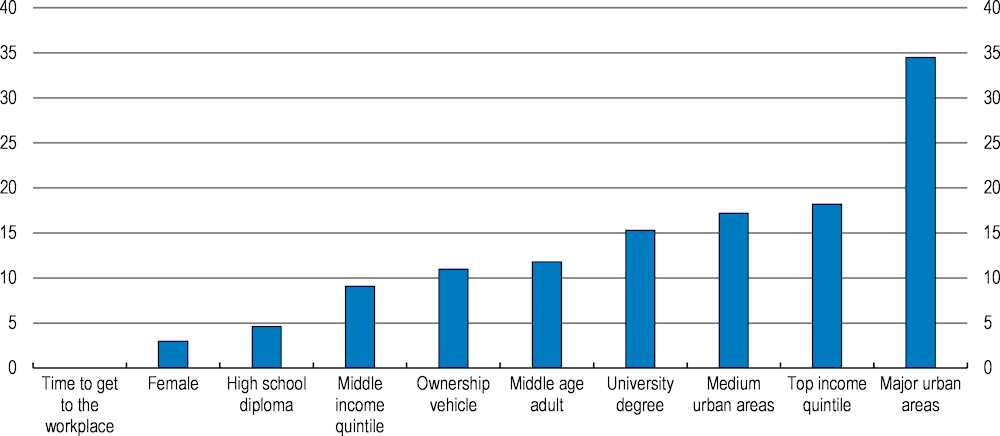

Using micro data from the Census of Population and Housing 2020 (Censo Nacional de Población y Vivienda 2020) Maravalle and Gonzalez Pandiella (forthcoming) estimate a Probit model to assess the main socio-economic characteristics shaping the probability of a worker to live in an adequate house. By focusing on workers, it is possible to take into account access to jobs as a relevant aspect of housing. by considering how long it takes for a worker to get to the workplace.

Average marginal effect on the probability of living in an adequate house, %

Note: The average marginal probability measures the average change in the probability of living in an adequate house for an individual who belongs to a category of a socio-economic variable different from the benchmark category. The benchmark categories of the variables reported in the chart are: living in a rural area (less than 2500 inhabitants); Bottom income quintile (income variable); having completed primary education (education attainment variable); male (gender variable); young adults (15-24 years old). The category “Middle age adults” refers to adults between 55 and 65 years of age. Medium urban areas have between 15 and 50 thousand inhabitants and major urban areas have more than 100 thousand inhabitants. A house is categorised as adequate according to the criteria set by the National Housing Commission (CONAVI) to identify substandard dwellings (rezago habitacional).

Source: Maravalle and Gonzalez Pandiella (forthcoming).

Mexican workers living in major urban areas (more than 100 thousand inhabitants) have a higher probability of living in an adequate house that is 35 percentage points higher than a worker living in rural areas. Other factors that are positively associated with the probability of living in an adequate house are a high level of education, the age and the income level. A middle-aged worker (55-64 year old) has a probability of living in an adequate house that is 10 percentage points higher than a young worker. Earning an income in the top quintile of the income distribution increases the probability of living in an adequate house by 15 percentage points with respect to a earning an income in the bottom quintile. These results highlight the extent to which inadequate housing disproportionately impacts youth, individuals with low incomes and those residing in rural and peripheral areas.

Purchasing a house is a challenge especially for low- to middle-income households. Low supply and high demand for housing have pushed up real housing prices by 31% between 2005 and 2020, in line with the average OECD country but less than in some regional peers (Figure 5.6). House prices have increased 1.5 times faster than the average income over the same period. It would take around 30 years’ worth of salary for a poor household (1st income decile) and 9 years’ worth of salary of a middle-income household (5th income decile) to purchase an average dwelling (INEGI, 2022[3]).

Index, 2005 = 100

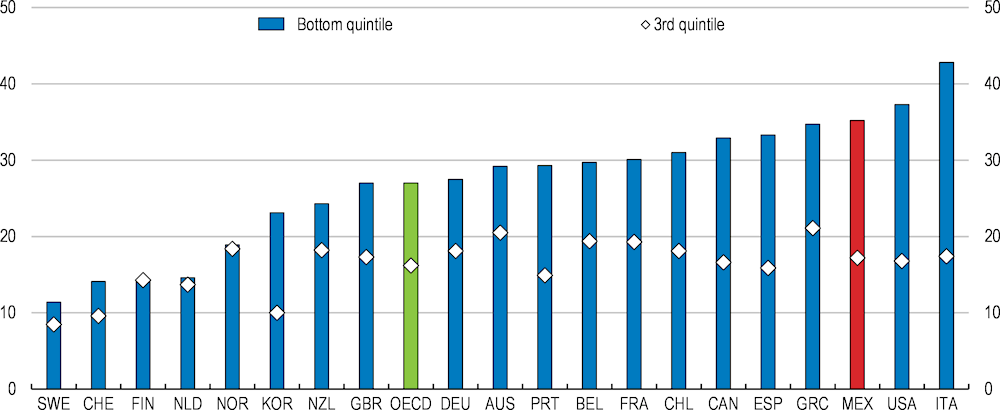

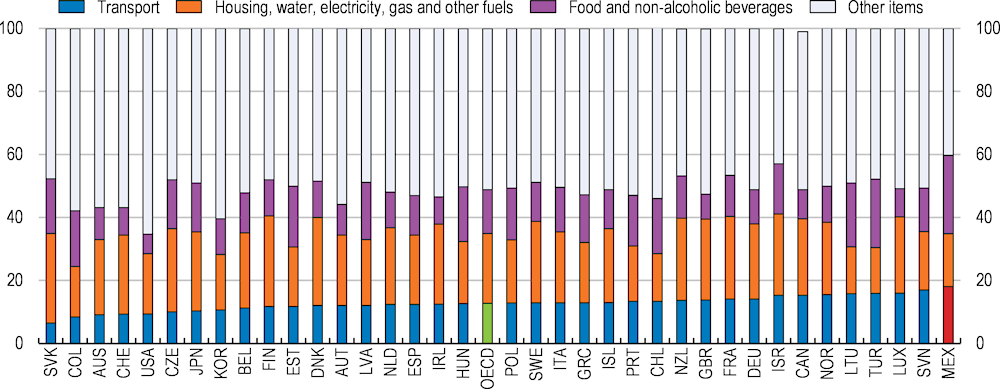

Housing costs (rent or mortgage) represent around 17% of the average income, in line with OECD countries. However, housing costs are far higher for low-income households (Figure 5.6), and can reach around 60% of the gross income of households in the lowest income decile when utilities costs are included (SEDATU, 2019[2]). Mexico is the third country with highest housing costs.

Median of mortgage burden (principal repayment and interest payments) as a share of disposable income in the bottom and the third quintiles of the income distribution, %, 2020 or latest year available

Note: In Chile, Mexico, Korea and the United States gross income instead of disposable income is used due to data limitations.

Source: OECD Affordable Housing Database.

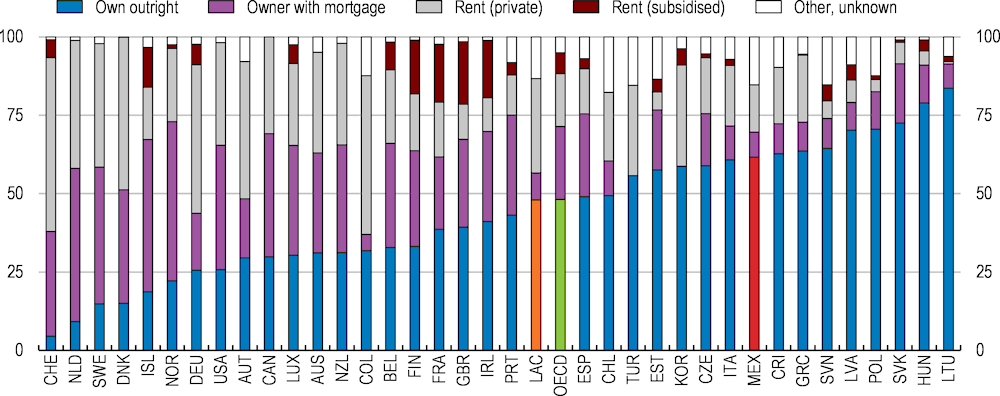

The size of the housing rental market in Mexico is too small to provide an alternative to homeownership for low- and middle-income households, even if rental prices have increased far less than housing prices (Figure 5.7). Only around 16% of the housing stock is used for rental, though it is higher in urban areas where it reaches a maximum of around 30% in the metropolitan area of the Mexico Valley, which is nonetheless far below the 50% recorded in some large OECD metropolitan areas (Los Angeles, New York and Paris). A strong preference for homeownership over renting and a housing policy biased towards housing acquisition have contributed, among other factors, to the limited development of the rental market in Mexico in the past (Figure 5.8) (INFONAVIT and ONU-Habitat, 2018[4]; OECD, 2015[5]).

The rental market is also characterized by widespread informality (40%) (SEDATU, 2019[2]), which often concerns properties under foreclosure. Around 67% of the tenants, mostly low-income, allocate more than 30% of their income to pay the rent (CONEVAL, 2018[6]).

Price to rent ratio, index, 2015 = 100

Share of households in different tenure types, %, 2020 or latest year available

Note: LAC is a simple average of Chile, Colombia, and Costa Rica.

Source: OECD Affordable Housing Database.

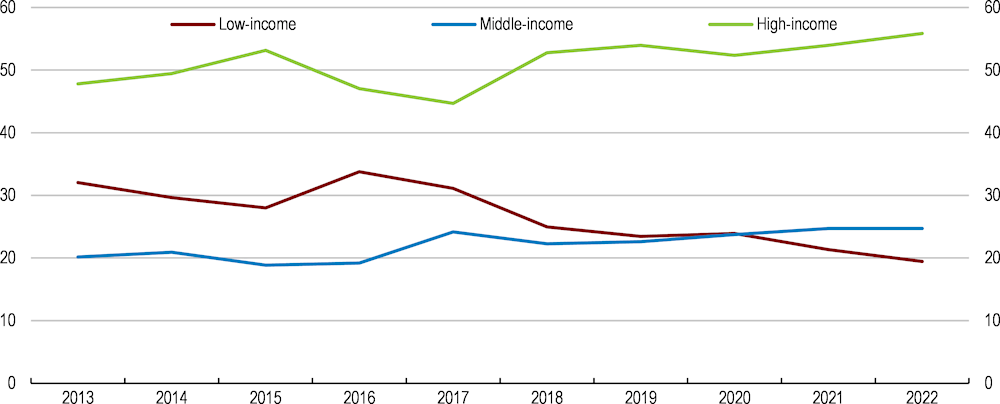

Access to housing credit is limited, particularly for low- and middle-income households, and most homeowners must rely on own-resources to purchase their house, especially in poor regions. More than half of all housing credit (56%) goes to the top 20% high-income households, with middle-income and low-income households, representing 80% of all households, receiving, respectively, one fourth and less than a fifth of all housing credit (Figure 5.9). Housing credit is also concentrated in states with a high GDP per capita, such as Baja California, Baja California Sur, Nuevo León or Ciudad de Mexico, and is scarce in poor states, such as Chiapas, Oaxaca, Tlaxcala and Guerrero,

The share of credit to low-income households has also been diminishing in recent years despite the increase in the volume of housing credit (2.1% y-o-y). This dynamic is related to two factors: the increasing weight of commercial banks in the mortgage market, which provide financial services mostly to high-income households. Second, a lower weight of low-income households in the credit portfolio of the Institute of the National Fund for Workers' Housing (INFONAVIT), which traditionally provides mortgages to low- and middle-income formal workers and charges below market interest rates. The share of INFONAVIT’s credit portfolio for low-income households has fallen from 52% in 2013 to 29% in 2022. INFONAVIT’s non-performing loan rate (18.6% in March 2023) remains high with respect to commercial banks (2.6%).

Distribution of housing credit flow by household income level, %

Note: High-income households have monthly earnings above 9 UMA and are 20% of all households; middle-income households have monthly earnings between 4 and 9 UMA and are 40% of all households; low-income households have monthly earnings below 4 UMA and are 40% of all households.

Source: SNIIV and OECD calculation.

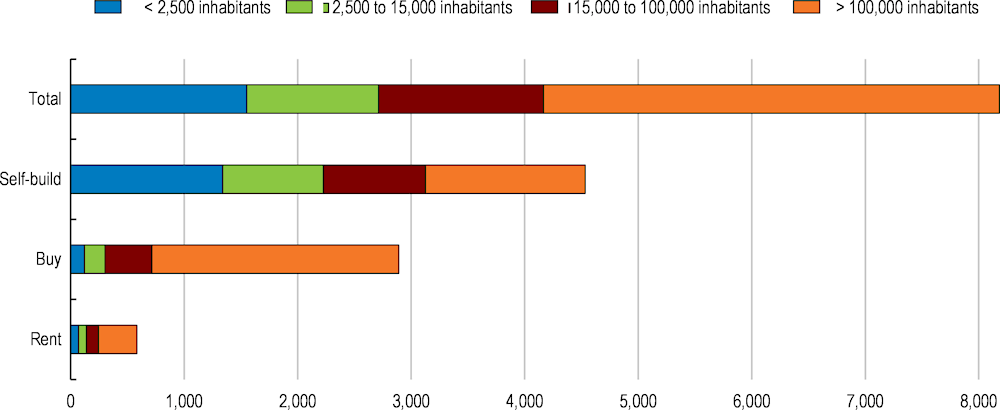

Demand for housing is high and amounts to around 8 million dwellings (Figure 5.10), or one fifth of the current supply of private housing units (35 million), and is projected to increase. Even if the rate of population growth is expected to decline, at least 5 million additional dwellings will be required by 2050 if the average household size is the same as in 2020. However, if the household size keeps falling, say as much as it did between 2000 and 2020, the demand for new houses could increase up to 13 million by 2050.

Total number of households that need to rent, buy or build a home independent of the one they live in, thousands, 2020

Note: Rural areas are those with less than 1500 inhabitants. The demand for housing is based on households’ self-reported needs for a new dwelling.

Source: Encuesta Nacional de Vivienda 2020.

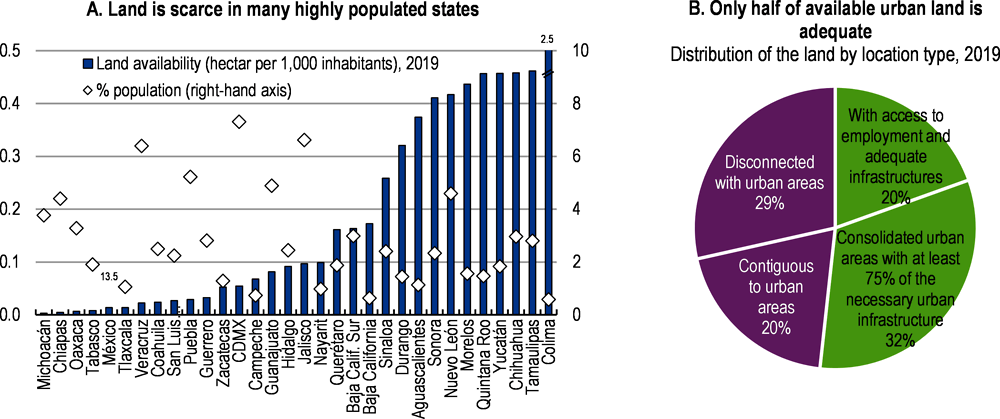

Note: Adequate lands are classified as U1 and U2. U1 lands are located in areas with access to employment and adequate infrastructures. U2 lands are located in consolidated urban areas with at least 75% of the necessary urban infrastructure; U3 lands are located in areas contiguous to the urban area; FC lands are located in areas disconnected with the urban areas. “México” refers to the state of México and not to the whole country. Probabilities in panel B may not sum to total due to rounding.

Source: SNIIV.

Land for urban development is scarce especially in highly populated states in the Centre and in the South (e.g., the state of México, Chiapas, Veracruz) (Figure 5.11, panel A) and decreased by 6.5% between 2014 and 2019 (RENARET, National Registry of Land). Moreover, only around 20% of the land reserved for future developments has good access to infrastructure and job opportunities (Figure 5.11, panel B) and could be considered as adequate (in terms of location, geology and water availability) according to requirements set in the National Urban Development Program and Land Use Policy (SEDATU, 2019[2]).

Many households, especially in the South and in the Centre, struggle to access essential urban services (Figure 5.12) because of unfavourable housing locations. For example, in case of a health emergency it takes on average 40 minutes to get to a hospital in Mexico, but it takes almost an hour in Guerrero, Chiapas and Oaxaca (INEGI, 2022[3]). Housing location is a key feature of good housing, affecting access to jobs, education and health, as well as recreational and cultural services, thus contributing directly to the well-being of people and to shaping equality of opportunities.

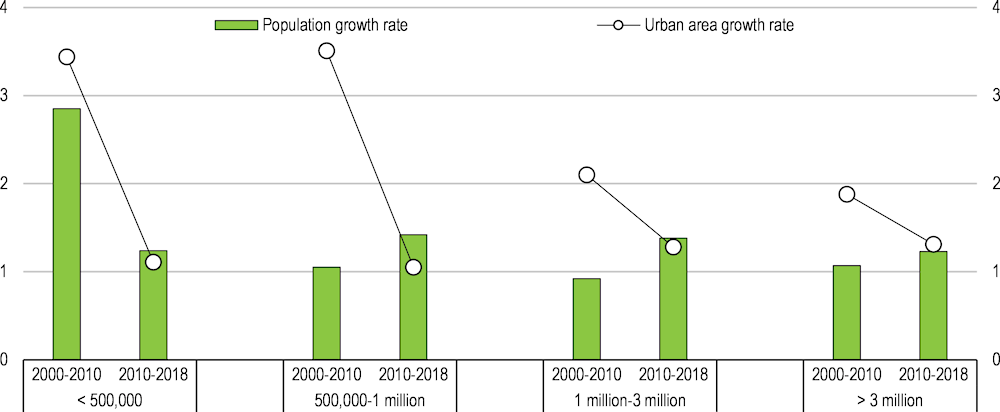

A key determinant of poor housing location in Mexico is the disconnection among housing, urban and transport policy that has favoured urban sprawl (INFONAVIT and ONU-Habitat, 2018[4]). Between 1980 and 2017, the growth rate of urban built-up areas was more than twice (5.4% yearly) that of the urban population (2.4% yearly) (INFONAVIT and ONU-Habitat, 2018[7]), causing a significant fall in population density (from 272 to 100 inhabitants per hectare against an optimal standard of 150 inhabitants per hectare) (INFONAVIT and ONU-Habitat, 2018[7]). Low-density urban areas lead to disconnection between central and peripheral areas, higher cost for the provision of public services and higher criminality and poverty.

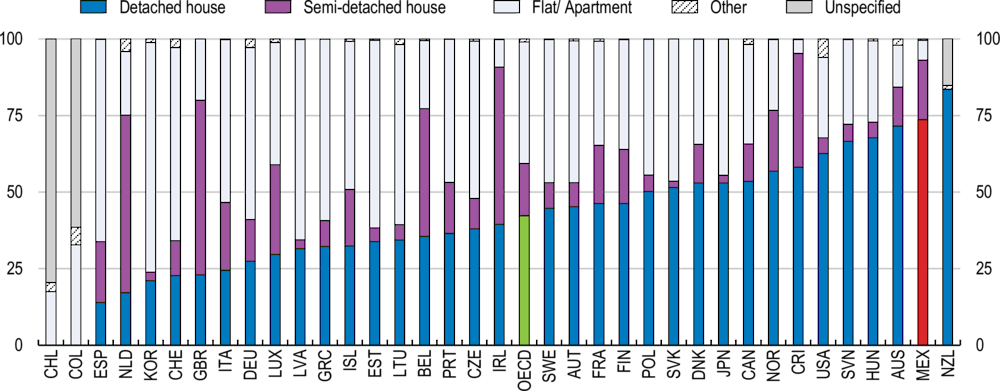

Share of households unsatisfied with the time-distance required to access a service, %

Urban sprawl continued between 2010-18, mostly through a fast increase in built-up area in rural localities within metropolitan areas (Zubicaray et al., 2021[8]) supporting the hypothesis that new housing continued developing in low-density areas disconnected from the urban centres (Figure 5.13). As a consequence, Mexico is currently characterised by low-density residential-only areas, with prevalence of single-family dwellings (Figure 5.14), and increased reliance on private vehicle for transportation (Montejano et al., 2023[9]). Mixed land use, which can host residential dwellings, industrial units and public equipment, is not widespread (8.5% at the national level) (Table 5.1).

Composition of use of land by type in metropolitan and rural areas

|

Type of land use |

Metropolitan areas |

Rural areas |

National |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Residential use, high density (%) |

1.1 |

0.1 |

0.6 |

|

|

Residential use, medium density (%) |

2.6 |

0.1 |

1.6 |

|

|

Residential use, low density (%) |

72.2 |

86.6 |

77.1 |

|

|

Mixed use, high density (%) |

3.8 |

0.9 |

2.9 |

|

|

Mixed use, medium density (%) |

5.2 |

5.4 |

5.6 |

|

|

Mixed specialized (%) |

1.0 |

0.2 |

0.7 |

|

|

Services and commercial (%) |

2.2 |

0.3 |

1.6 |

|

|

Urban Equipment (%) |

7.6 |

5.9 |

7.0 |

|

|

Industrial (%) |

3.2 |

0.2 |

2.0 |

|

|

Green and recreational areas (%) |

1.1 |

0.4 |

0.8 |

Note: “Residential use, high density“ have more than 150 dwelling per hectare; “Residential use, medium density“ have between 100 and 150 dwelling per hectare; “Residential use, low density“ have less than 100 dwellings per hectare; “mixed use, high density“ have a ratio of economic units (industry, commerce and services) to residential dwellings higher than 2; “mixed use, medium density“ have a ratio of economic units (industry, commerce and services) to residential dwellings below 2; “mixed specialised“ is land with economic units and urban equipment; “Services and commercial” is land with only commercial and services; “Urban Equipment” is land with urban equipment (schools, hospital, public square, urban infrastructure, transport infrastructure, etc.); “Industrial” is land with industrial economic units.

Source: Monteano et al. (2022).

Growth rate of urban area and population, by urban area population, average 2000-2009 and 2010-2018, %

Note: Over 2000-10 (130 cities) and 2010-18 (133 cities).

Source: Zubicaray, G., et al. (2021).

Urban sprawl, by increasing administrative fragmentation, reduces the productivity benefits from urban agglomeration. In Mexico, a city with twice the number of municipalities within its functional boundaries is on average 3.4% less productive (Ahrend et al., 2014[10]). Urban sprawl limits social mobility that has a positive impact on labour productivity and innovations (Heeckt and Huerta Melchor, 2021[11]). Urban sprawl is associated with increasing socioeconomic segregation, with usually low- and middle- income households living in settlements located in disconnected peripheral areas, while high-income households concentrate in closed-shape urbanizations (urbanizaciones cerradas) in central areas (INFONAVIT and ONU-Habitat, 2018[7]). By raising the number of households unfavorably located, urban sprawl increases the cost of developing transport infrastructure, water and electricity distribution systems, and wastewater treatment plants (Rojas and Medellin, 2011[12]).

Occupied residential dwelling types, % of the total occupied residential dwelling stock, 2020 or latest available year

Note: The classification and terminology on types of dwelling may differ slightly from country to country. In general, detached houses refer to dwellings having no common walls with another unit. Semi-detached houses refer to dwellings sharing at least one wall or a row of (more than two) joined-up dwellings. Flats/apartments refer to dwelling units in a building sharing some internal space or maintenance and other services with other units in the building. Other refers to mobile homes, such as caravans and house-boats.

Source: OECD Regions and Cities at a Glance 2022; OECD Affordable Housing Database.

The government recently reformed the national housing policy and its governance to facilitate access to adequate housing to all Mexicans (Box 5.2). The National Housing Programme 2019-24, and the National Housing Programme 2021-24, set a series of ambitious objectives including improving the quality of the housing stock, extending finance to low-income households and informal workers and enhancing policy coordination. The new housing policy includes a larger support for home improvements and the purchase of existing homes, abandoned home recovery and a focus on assisted self-build to provide housing to low-income households. The goal is also to coordinate infrastructure investment at the metropolitan level and reforming zoning policies to encourage mixed land use, including housing and public services. The General Law of Human Settlement stipulates that governments at any level must provide tools to generate land for housing for low-income and vulnerable groups.

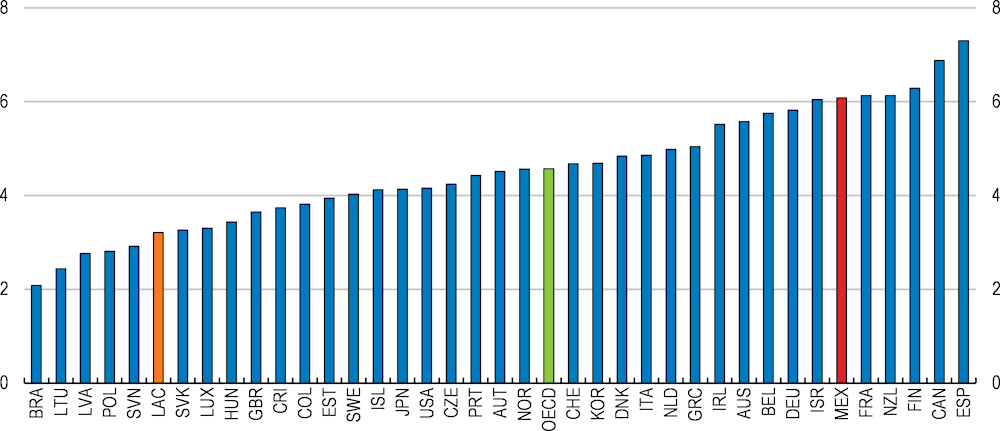

The new policy puts a stronger emphasis on providing support to low-income households than past ones via means testing. This is a welcome change of direction, as in the past the main strategy to increase access to housing was to facilitate mortgage lending to formal workers, mostly in the highest income deciles, via federal institutes. This strategy, successfully increased residential investment (Figure 5.15), also including a significant part of self-built housing, but failed to grant access to housing to low-income households and contributed to large developments in cheap lands in peripheral areas disconnected from jobs and urban services (OECD, 2015[5]). Expanding the range of housing subsidies for low-income households and supporting the creation of a social rental housing sector would be valuable additional steps to improve access to quality housing. Tasking states with ensuring that municipalities comply with higher level legislation would help the implementation of national housing and urban development policy. Setting quality standards and promoting an integrated transport system in metropolitan areas would contribute to make public transport more efficient and affordable especially for vulnerable people living in peripheral disconnected areas. All these policies are analysed in detail in the rest of this chapter.

Investment in dwelling, % of GDP, 2000-2021 average

Note: LAC is a simple average of Colombia, Costa Rica, and Brazil.

Source: OECD Economic Outlook, Investment by asset (indicator).

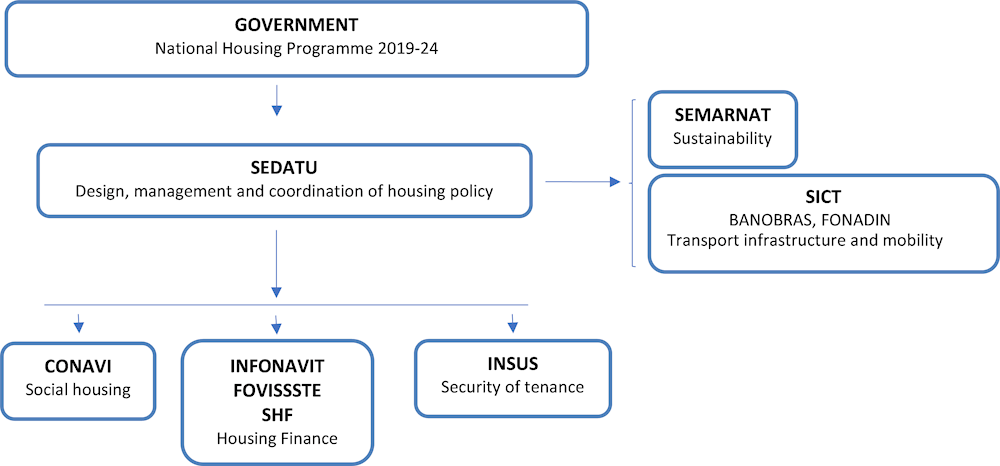

The bodies and agencies that hold responsibilities for the design, funding and implementation of the housing policy in Mexico (Figure 5.16) are:

The Ministry for Agrarian, Territorial and Urban Development (Secretaria de Desarrolo Agrario, Territorial y Urbano, SEDATU) is since 2019 charged with leading and coordinating housing, transport and land use policy and overseeing all aspects of urban development. SEDATU is responsible for drafting and implementing the National Housing Programme and contributes to draft the National Land Policy and The National Strategy of Territorial Planning.

The National Housing Commission (Comisión Nacional de Vivienda, CONAVI) is the Federal Agency charged with the implementation of the social housing policy. CONAVI provides subsidies for house improvements or enlargement, land purchase or self-build, giving priority to vulnerable households with housing deficits.

The National Institute for Sustainable Land (Instituto Nacional de Suelo Sostentable, INSUS) since 2019 focuses on security of tenancy, the regularization of informal settlements and the generation of affordable land.

The Institute of the National Fund for Workers' Housing (INFONAVIT) is the Mexican federal institute for private sector worker's housing that provides its affiliates (private sector workers) with housing-related mortgage products for buying, remodeling or building a home. The Housing Fund of the Social Security and Services Institute for Public-Sector Workers (FOVISSSTE) provides housing-related mortgage products to public sector workers.

The Federal Mortgage Society (Sociedad Hipotecaria Federal, SHF) is state-owned development bank that grants loans and guarantees to mortgage intermediaries in Mexico and acts as market maker in the mortgage market.

The Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources (Secretaria de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales, SEMARNAT) issues environmental regulation for urban development and assesses the environmental impact of urban development projects.

The Secretariat of Communications and Transportation (Secretaria de Infraestructura, Comunicaciones y Transportes, SICT) is responsible for transport and mobility infrastructure.

The National Bank of Public Works and Services (Banco Nacional de Obras y Servicios Públicos, BANOBRAS) is a state-owned development bank that finances public and private investment in infrastructure and public services. BANOBRAS operates the National Infrastructure Fund (Fundo Nacional de Infraestructura, FONADIN) which provides credit, loans and guarantees for planning, designing and implementing infrastructure projects with public and private participation in cities with more than half a million inhabitants in transport, communication, water, environment and tourism. FONADIN promotes investment in public transport and sustainable mobility through the Federal Support Program for Massive Transport Infrastructure (Programa Federal de Apoyo al Transporte Masivo, PROTRAM).

The National Housing Policy Framework currently consists of four programmes that are aligned with the National Development Plan 2019-24. Among its objectives it aims to reduce the number of substandard dwellings by 2.2 million units by 2024 (from 9.4 million to 7.2 million) and to promote more compact, connected and sustainable cities.

The National Housing Programme (Programa Nacional de Vivienda, NHP) aims to provide affordable high-quality houses to all Mexican through a mix of policies including improving the quality of existing housing units, promoting the rental market and housing cooperatives, extending finance mechanisms to people not eligible for a credit via INFONAVIT and FOVISSTE, and providing assistance to self-build in marginalised areas. The NHP also aims to simplify and harmonise the housing policy framework and promote coordination across all levels of government and between them and the private and social sector.

The Urban Improvement Programme (Programa de Mejoramiento Urbano, UIP), coordinated by SEDATU, aims to enhance access to urban services and urban infrastructure in the peripheral areas of 100 Mexican cities. The UIP covers a large set of interventions including the rehabilitation of public spaces, the enhancement of existing infrastructure or the construction of new ones, the promotion of social production of housing, the provision of security of tenure and property rights, the promotion of urban planning and land use policy at the metropolitan level.

The National Reconstruction Program (Progama Nacional de Reconstrucción, PNR), operated by SEDATU and CONAVI together with the Ministries of Health, Education and Culture, provides the population affected by earthquakes in 2017 and 2018 with a subsidy for housing reconstruction or relocation.

Many low- and middle-income households cannot afford purchasing a house because of the high price of houses and land, the difficulty in mobilising developable land, the limited access to credit as well as the resistance of existing neighbors against densification (INFONAVIT and Fundación-IDEA, 2018[13]). A rental market insufficiently developed is another factor that fails to provide alternative housing solutions. Against this background, many households, mostly from vulnerable groups, have been left with the only option of self-build given the inability of public policies to directly provide affordable housing (Kunz-Bolaños and Espinosa-Flores, 2017[14]) (Figure 5.17).

Self-build homes, % of total private housing stock

Note: Only households who own the dwelling they live in are considered. Self-build includes dwellings built by the owner or by others hired by the owners and excludes purchases of already built dwellings or inheritance. “México” refers to the state of México and not to the whole country.

Source: Encuesta Nacional de Ingresos y Gastos de los Hogares (ENIGH) 2022.

The new housing policy focuses on providing housing subsidies to the low-income population with substandard housing (rezago habitacional) (Box 5.2). The task is immense. The target population is one fifth of Mexican households (7.4 million low-income households or around 25.8 million people) that needs either a new home (three hundred thousand households) or housing improvements (around 7.1 million households) (CONAVI, 2021[15]). However, the National Housing Commission (CONAVI) has limited staff (around 400 people, 348 with a temporary position) and financial resources (0.024% of GDP in 2022) to reach this target. Between 2019 and 2022, it only reached 300 thousand households. At this pace it would take 97 years to reach the entire target population. In addition to being too small, the budget allocation is subject to large shifts across social housing programs.

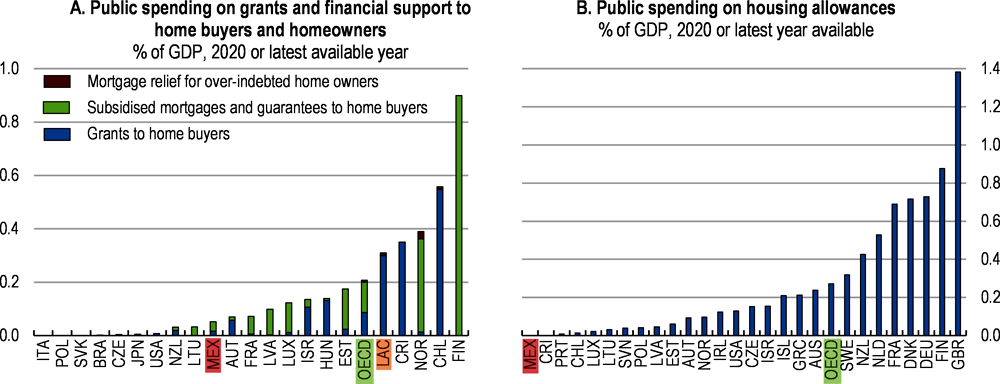

Public spending on housing support is low in international comparison (Figure 5.18, panel A), and aimed at supporting the purchase of a home or housing improvements, but not other housing-costs such as rents or utilities, as in other countries where such housing allowances are significant (Figure 5.18, panel B).

Note: Panel A: for Finland, Israel, Mexico, New Zealand, and the United States, information is missing on one programme, and the reported amount is therefore a lower-bound estimate. Panel: B: Housing allowances are a form of demand-side support generally provided to low-income households who meet the relevant eligibility criteria to help meet rental and other housing costs, temporarily or on a long-term basis.

Source: OECD Affordable Housing database.

The main housing subsidy scheme (Social Housing Program) suffers from several shortcomings. A welcome development is that it has become more targeted and favours subsidies for dwellings located in dense urban areas with minimum infrastructure standards. However, the scheme does not take sufficiently into account the difference in the price of land or housing across different metropolitan areas and between central, which are typically more expensive, and semicentral areas (INFONAVIT and ONU-Habitat, 2018[4]). Another issue, is that it favours the purchase of low-value new dwellings or self-build over the purchase of existing dwellings, by giving lower subsidies for the purchase of older dwellings, or renting. The government should expand the range of housing subsidies for low-income households to include renting and recurrent costs, such as utility bills, and align incentives between buying (new or old) and self-build. Subsidies provided via co-financing that benefit households with access to credit that are typically better-off should continue being reduced, as they divert limited funds from poor towards better-off households.

The National Housing Commission (CONAVI) provides housing subsidies mainly through the Social Housing Program (Programa de Vivienda Social, PVS) and the Emerging Housing Project (Proyecto Emergente de Vivienda, PEV).

The Social Housing Program targets low-income households (with incomes up to around 15 768 MXC pesos in 2023 or around 900 USD) living in substandard housing (rezago habitacional) identified through households survey data and Census. Priority is given to households living in highly marginalized areas, in risk areas, and vulnerable groups (e.g. indigenous groups, very low income or female headed households). Subsidies may be used to purchase a dwelling (old or new) or for self-build (new construction, enlargement or improvement of existing dwelling), relocation (e.g., located in risk area or in areas interested by priority federal infrastructure projects), reconstruction (after natural disaster), sustainable integral improvement (including energy efficiency measures such as solar panels, biodigestors, water collectors) or adaptation of an existing dwelling. Subsidies for self-build are provided via the Assistance to Social Self-Build Process (Proceso de Producción Social de Vivienda Asistida) that includes both financial and technical assistance. Households not necessarily build the house by themselves but receive technical support via certified professionals who operate locally to guarantee the adequacy of building standards. The subsidy is only disbursed conditional on CONAVI’s approval of the final project. The amount of the subsidy varies depending on whether the beneficiary receives a credit (co-financing modality) or not (100% CONAVI modality), the cost of the project, and the characteristics of the project. The support depends on housing location (it is higher in an urban consolidation zone, in areas close to urban services and public transport, and in high density areas) and its environmental standards. Eligibility also requires each project to respect local urban planning regulation and not to be in risk areas. Subsidies for home improvement interventions (enlargements, rehabilitation) appear sufficient to cover the totality of the costs and are in line with the average cost for housing interventions (ENVI 2020).

The Emerging Housing Project started in 2020 as a reaction of the COVID-19 pandemic and targets low-income population living in marginalized areas in priority municipalities and provides subsidies only for enlargement or improvement of an existing dwelling. Between 2020 and 2022 CONAVI provided 165 thousand subsidies.

CONAVI provides housing subsidies also via other programs of smaller size, including the National Reconstruction Program (Programa Nacional de Reconstrucción) targeting the 180 thousand dwellings damaged by the 2017 and 2018 earthquakes; subsidy programs promoting the resettlements of local communities living in high-risk areas or the relocation of residents from areas affected by major infrastructure projects (e.g., Tren Maya); and social housing projects involving indigenous people (e.g. Yaqui population).

Source: REGLAS de Operación del Programa de Vivienda Social para el ejercicio fiscal 2023; CONAVI.

A significant part of support in the housing subsidy scheme promotes self-build through the Assistance to the Social Self-Build Program, which represented around two thirds of CONAVI budget in 2022. Despite strong efforts, the strategy has some limitations. Firstly, single households do not benefit from economies to scale in the construction process. Secondly, individual self-build projects are mostly low-density buildings, such as single-family houses, thus hardly a solution against urban sprawl. The self-build program should be thoroughly evaluated to assess its effectiveness in improving access to quality housing and public services among vulnerable populations, including its impact on urban sprawl and densification.

An alternative could be to encourage self-build housing cooperatives where a group of people join forces to buy land to build housing. As cooperatives are more likely to access credit, the cost might be lower than for individual self-build. Additionally, a cooperative is more likely to opt for large-scale vertical construction, limiting urban sprawl. A successful self-build housing cooperative requires legal and organisational skills (Oviedo-Gonzalez, 2014[16]) as its members participate in many activities and decision-making processes including selecting the land where to build, designing and approving the development project, applying for a credit or a building permit. CONAVI could provide financial, technical, legal and organisational support for cooperatives as legal and organisational skills might not be widespread among its members. Support could be provided both directly or via certified professionals or non-profit organisations. Mexico could also follow the example of Chile where groups of vulnerable households may receive housing subsidies for a collective self-build project via the Fondo Solidario de Elección de Vivienda.

The National Housing Program sets the goal of increasing the volume of credit to low-income households and informal workers but does not provide clear guidelines on how to achieve it. Informal workers have almost no access to credit as a formal job is a key requirement to access credit in Mexico (Cassimon et al., 2022[17]). Moreover, affiliation to the social security remains a key requirement to receive a credit from the federal institutes INFONAVIT or FOVISSTE, even if recent products have started to extend credit to people who don’t have a formal job but did so in the past (e.g. MejOraSí).

The federal Institute (INFONAVIT) could contribute to improve access to credit for low-income households and informal workers. To do that, INFONAVIT could improve its assessment of the creditworthiness of informal and low-income workers by, for instance, using alternative information such as regular payment of utilities or mobile phone bills, which are increasingly used in several countries to assess the creditworthiness of informal workers (Maravalle and González Pandiella, 2022[18]). The Federal Mortgage Society is planning the securitization of mortgages issued by fintechs that use innovative credit scoring techniques to provide housing finance to customers that are not served by commercial banks or are not affiliated to social security. This very welcome initiative might be scaled up.

The Federal Mortgage Society is planning to provide direct mortgages on a small scale (around 2000 credits per year) through a new financial product (hipoteca digital). This initiative would target households with incomes from formal and informal jobs, though prevalently from a formal source, to help them purchase houses below 1.5 million Mexican pesos. This financial product targets a segment of the population estimated at around 2 million households that is currently uncovered by other federal agencies or commercial banks.

INFONAVIT could also further contribute to improve housing quality. Despite recent increases, it only allocates a marginal share of its credit portfolio (around 2.4% of the amount of credit issued over 2019-2022) to housing improvements. Even a small increase in the share of the credit amount dedicated to housing improvements would translate into a substantial increase in the number of credits, as the average amount of credit for housing improvements is far smaller than that for purchasing a dwelling.

Mexico could reintroduce public mortgage guarantee schemes to facilitate access to credit to low-income informal workers. Between 2012 and 2021 the National Fund for Social Housing Guarantees (Fondo Nacional de Garantías para la Vivienda Popular, FONAGAVIP) provided public guarantees that allowed around 10 thousand low-income households with informal jobs to receive mortgages from commercial banks at favourable conditions. Public guarantees were rarely invoked (0.4% of the cases). The elimination of FONAGAVIP in 2021 further reduced access to credit for informal workers.

Mexico could also promote the development of green mortgage financial instruments to support access to energy-efficient housing. The Federal Mortgage Society provided credit and technical assistance to adopt ecotechnology to only 70 thousand dwellings between 2013 and 2020 (program Ecocasa). The new sustainable taxonomy (see chapter 2) has large potential to facilitate that the public and private sector define investment strategies conducive to more energy-efficient housing solutions. This is exemplified by the recent launch of green mortgages by two private banks. Through a green mortgage, homebuyers who are purchasing energy-efficient homes or making energy-efficient upgrades to existing homes can access a lower rate on their mortgage, facilitating access to more affordable and environmentally-friendly housing.

Mexico could increase the supply of rental housing through three main channels. A reform of housing taxation and landlord-tenant regulation could help expand the supply of private houses for rent and support the formalisation of rental contracts. Fiscal and administrative incentives could be provided to further promote the involvement of the private sector in increasing the supply of rental affordable housing targeting middle-income households. Last, developing a social rental housing sector would particularly benefit low-income households.

In Mexico the legal process of lease dispute resolution is lengthy and costly. Tight rent controls and high tenure security reduce rental supply by lowering the expected return from rent (OECD, 2023[19]) and favours informal rental contracts. The regulatory framework for rental housing could be reformed to strike a better balance between tenancy protection and the interest of the landlords. This could be achieved by allowing for reasonably short-term lease duration and clear termination rights and standardised regulation across states. Alternative out-of-court dispute resolution mechanisms could be introduced to facilitate the resolution of conflicts between landlords and tenants regarding the lease agreement (INFONAVIT and ONU-Habitat, 2018[4]). Following the example of Mexico City, specialised tribunals could be extended to the whole country to expedite the resolution of lease dispute.

A public guarantee of timely rental payment could be provided to landlords (INFONAVIT and ONU-Habitat, 2018[4]) (e.g., dispositif visale in France) in favour of vulnerable groups (youth, seniors, immigrants, only mothers) who are often discriminated (INFONAVIT, 2022[20]). A past housing policy initiative aimed to improve formal rental market (Arrendavit) did not prove effective also for not offering sufficient guarantees against non-rent payment (OECD, 2015[5]). The National Workers' Housing Fund Institute (INFONAVIT) should allow workers with an INFONAVIT account to use it as a guarantee for rental payment. This would be a valuable initiative worth putting into place swiftly, as it would help to expand the size of the rental market and reduce the number of informal rental contracts. It would particularly benefit young workers and workers transitioning between formality and informality periodically.

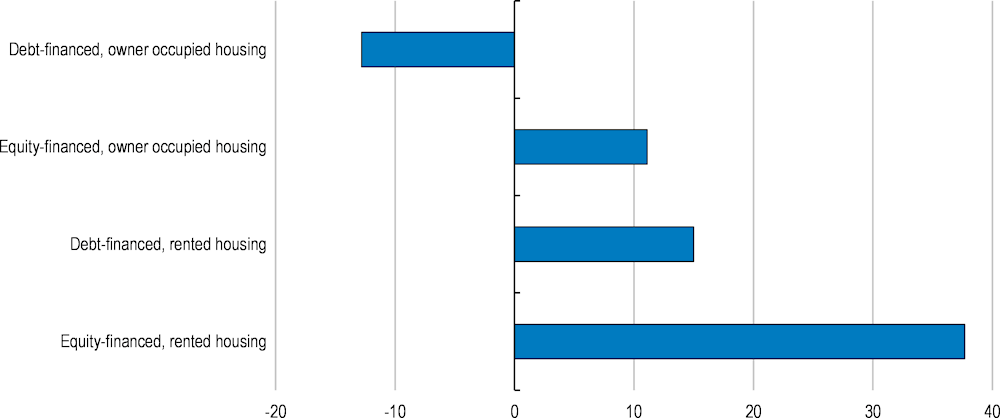

Housing taxation in Mexico encourages homeownership, especially if debt-financed, over investing for rental housing, especially if equity-financed. This occurs mostly because of a preferential tax treatment of debt-financed homeownership via mortgage interest relief. The marginal effective tax rate, which measures the tax incentive to housing investment across tenure types (owner-occupied or rental property) and financing sources (debt or equity), shows that the minimum return to make investing in debt-financed owner-occupied housing worthwhile is actually negative (-13%), while it is 11% for an equity-financed owner occupied housing investment (Figure 5.19) (Millar-Powell et al., 2022[21]).

Marginal Effective Tax Rates by investment scenario, 100% average wage taxpayer, %, 2016

Note: Results assume inflation at the OECD average level; with a 20-year holding period; and the returns stemming 50% from capital gains and 50% from rent or imputed rent.

Source: Millar-Powell, B. et al. (2022).

Phasing out mortgage interest relief would reduce the disincentive to invest in rental housing and imply further advantages, such as producing a fiscal gain (0.1% of GDP) and reducing inequality, as mortgage interest relief benefits relatively more high-income households. Reducing it gradually would avoid financial difficulties for households repaying their loans and limit its potential impact on housing prices (OECD, 2022[22]). To maintain the benefit for low-income households its eligibility could be restricted via a threshold on household’s personal income or the property value. Alternatively, a cap could be introduced on the total interest deduction to be claimed as a tax credit. Mortgage interest relief could be permitted on secondary residences that are rented, for example by taxing the rental income net of mortgage interests. As an alternative, Mexico could introduce a tax relief on paid rent for tenants (such as in Hungary and Ireland), also in exchange for rental contracts at below market level and longer duration (e.g. contratti convenzionati in Italy) (Salvi del Pero et al., 2016[23]), though this should be accompanied by measures that disincentivise the use of informal rental contracts and make emerge rental income. Reducing mortgage interest relief could also moderate house price growth in markets where housing supply is constrained and where tax subsidies tend to be fully capitalised in housing prices.

Moreover, Mexico could follow the example of several OECD countries that shifted from transaction taxes to recurrent taxes on real estate as taxing the income produced by an asset is more efficient than taxing their purchase or sale. Transaction taxes on housing purchases (Impuesto sobre adquisición de inmuebles y derecho de registro) in Mexico range between 2% and 6% of the transaction price, depending on the state and the purchase price. They reduce housing market efficiency by discouraging housing transactions, and hinder worker mobility via higher transaction costs for owner-occupants than renters. Shifting housing taxation away from transaction to recurrent taxes should be done gradually (e.g., as in Australia) to increase its public acceptability (OECD, 2023[19]). This reform could increase access to credit, especially for low-income people, by reducing the initial amount necessary to purchase a dwelling.

Incentives could be provided to further promote the involvement of the private sector in increasing the supply of rental affordable housing. Policy tools may include public-private partnerships (Box 5.4) or well-designed tax regimes, such as a tax credit for developers (e.g., the Low Income Housing Tax Credit in the Unites States). However, these incentives need to be well designed to be effective. In France, the Loi Pinel sets a maximum rent per square meter at the regional level for affordable rental housing, but in regions with a tight housing market it is only marginally below market price in the absence of rent control. Another problem with these initiatives is that they encourage building new flats where rental prices are low, typically in places where there is little demand resulting in empty dwellings and little effect on rents in places where rents are high. As an alternative, refundable tax credits or direct subsidies for developers tend to be more effective but imply higher fiscal costs (OECD, 2022[22]). Other options include a preferential administrative regime to promote affordable housing provision, such as a reduction in the number of authorizations and/or the time necessary to obtain them or a density bonus. Developers could also be required to build affordable housing as a share of new constructions. This could be achieved through the use of cross-subsidies, which allow developers to earn profits from selling or renting housing units at market-rates to subsidise the costs of building affordable housing.

Italy established a model of affordable housing based on public private partnership via a system of real estate funds established in 2009. This system of funds aims to increase the supply of affordable housing for a specific segment of households, mostly low- and middle-income households who are not poor enough to access standard social housing but are unable to meet the market price. The system of real estate funds is composed of a large national fund, funded by the Cassa Depositi and Prestiti (49.8%), the Ministry of Infrastructure and Sustainable Mobility (6.9%) and private capital (43.8%), that participates into a series of smaller local funds to finance affordable housing projects. The system incorporates an incentive mechanism to promote the quality of affordable housing. Each housing project is subject to a quality assessment that is performed twice, before and after the buildings have been handed over to the tenants, and covers aspects such as environmental sustainability, accessibility, green areas and quality of the dwelling. According to the result of the assessment, a social performance fee may be paid to the asset management company running the project.

France created the “affordable housing” status in 2014 halfway between social housing and the private market. Affordable housing are defined as accommodation for households that are too well-off for social housing but are unable to pay private-market prices. To attract capital from institutional investors the government created a specific financial framework and set a favourable taxation regime (a reduced VAT rate of 10% and an exemption to property taxes on developed land for a maximum of 20 years), in exchange for a minimum rental commitment of 15 years with rents 20% lower than market prices. To qualify as affordable housing, projects must be located in a “challenged” area defined by law, target middle-income occupants under a revenue threshold, and have a capped price or rent.

Source: (AVANZI, 2021[24]).

Social rental housing is an important alternative to the private rental sector in many OECD countries, accounting for around 7% of the housing stock on average, and reaching 21% in Denmark, 24% in Austria and 34% in the Netherlands (OECD, 2023[25]). There are also positive experiences among emerging countries, such as in Chile and South Africa, where the provision of rental housing for low- and middle-income households is related to urban regeneration policies (OECD, 2022[26]). In Mexico, instead, social rental housing is marginal, consisting of a small-scale pilot project targeting low-income workers in the army (Vivienda en Renta) and running discontinuously since 2014, and some state initiatives (e.g., the Instituto de Vivienda de la Ciudad de México provides a partial support to rents ranging between 1500 and 4000 Mexican pesos).

Due to limited public resources, social rental housing also represents a better option than housing subsidies for Mexico. Moreover, most evidence from OECD countries shows that subsidies, to homeownership or renting, end up inflating house prices and rents when housing supply is tight, which is often the case in most Mexican metropolitan areas.

To encourage the development of a social rental housing sector, Mexico could support private non-profit or limited-profit organisations to supply social housing, such as Community Land trust in the United States (Box 5.5) or social rental housing associations in Europe (Heeckt and Huerta Melchor, 2021[11]; Salvi del Pero et al., 2016[23]; INFONAVIT and ONU-Habitat, 2018[4]). For-profit providers can also participate, as in Germany where the social housing stock is predominantly private and the public sector provides housing allowances to social tenants (OECD, 2023[25]).

Encouraging the involvement of non-profit or limited profit private housing associations would have several advantages. It could promote vertical buildings and multifamily dwellings and help reduce urban sprawl and make a more efficient use of lands, especially in urban areas. It could reduce economic costs thanks to economies of scale related to a larger scale of social housing projects than individual self-build. Due to their established relationship with tenants, some social housing providers could also deliver additional services such as community development, employment generation, training and youth projects (such as in Austria). A fourth advantage is that a social rental housing sector does not necessarily imply a high fiscal cost. The level of public support to social rental housing is usually below 0.1% of GDP (Salvi del Pero et al., 2016[23]), and in most cases is represented by indirect subsidies (tax reliefs and state guarantees) rather than direct spending (CECODHAS, 2009[27]). The possibility of relying on indirect subsidies would suit Mexico, whose fiscal stance is characterised by a constrained spending capacity and a limited ability to ensure stable long-term direct public spending.

Community land trusts (CLT) in the United States, are community-based non-profit organizations that provide permanently affordable housing for lower-income households through resale restrictions. Members of a CLT are housing and human service providers, community activists and citizens who engage with lawmakers and city planners to preserve and expand the supply of affordable housing. CLTs are enabled to receive funds for property acquisition, rehabilitation, and the sale or rental of housing units. By statute a CLT determines the use of the land to pursue community needs. CLTs retain ownership of the underlying land and the resale restriction forces CLTs homebuyers to resell their homes at a price calculated to keep homes affordable for future generations of income-eligible buyers. CLTs’ funding for land and property purchases is usually provided either via taxation (increase in property transaction tax in Ohio), issuance of general obligation bond or land value capture instrument (the Tax Increment Redevelopment Zones in Houston).

Collaboration between land banks and CLTs may strengthen the supply of affordable housing over the long-term with land banks holding land and properties to recirculate into use and CLTs needing them for increasing the supply of affordable housing. The collaboration between land banks and CLT often is instrumental to the implementation of city’s or county’s housing plans. Experience highlights that widespread and protracted political support and adequate public funding are key elements for CLT-Land Bank collaborations to successfully address the need for affordable housing, especially in urban areas where demand for housing is structurally higher than supply. In the absence of public funding, land banks typically would sell their properties to privates, with the market driving their end-use, which reduces their ability to achieve more equitable outcomes in the housing market that are consistent with community needs.

In Houston, CLT homebuyers could afford a $180,000 house for $75,000 against traditional affordable housing units selling for approximately $140,000.

Mexico would need to elaborate a financing strategy to underpin the development of the social rental sector and its ability to effectively pursue its social goal. The experience of European countries provides interesting options as in the past decades they shifted towards a market-oriented social housing policy and started relying on private finance to maintain the existing stock and continue the production of new social housing (Box 5.6). Social rental housing providers may raise funds via special financial institutions (e.g., Housing Bank in Norway, Caisse d’Epargne in France) that raise capital through the issuance of specific and standardised financial instruments, such as social housing bonds (Box 5.7), self-sustaining financing-mechanisms (Austria and the Netherlands), including revolving funds (e.g., Denmark and Slovenia) or directly accessing financial markets relying on their equity as collateral (United Kingdom and Finland). In Mexico a federal institute (e.g., INFONAVIT), could play the role of special financial intermediary that supports the financing of the social housing sector. Over time, as the social housing sector grows, equity contributions from selling assets (land, dwelling stock) or from their tenants (e.g., in Austria social tenants provide an initial deposit) and the rent paid by social tenants might become available funding options.

The funding of the social rental sector encompasses a variety of sources that include public funding (direct and indirect subsidies, public loans), debt finance, equity contributions and rents paid by social tenants. Public support may include direct provision of social rental housing (transfers to the local authorities that own the stock) and subsidies to non-government social rental housing providers (supply-side subsidies in the form of grants, public loans from special public credit institutions and government-backed guarantees).

France created a dedicated circuit of investment and savings to promote social housing investment, the “Livret A” fund, which represents around 70% of social housing funding. The “Livret A” is a special savings deposit that can be opened in any commercial bank and pays a tax-free interest rate. These short-term savings deposits are pooled and converted into low-interest long-term loans for social housing by the state-owned financial intermediary (Caisse des Dépôts et Consignations) in exchange for a fee remunerating the banks for collecting the funds and paying the interest.

The system of home loan savings (Bausparen) is a saving scheme widespread in Austria and Germany addressing housing investment. It consists of a savings contract with a specialised credit institution, in which the customers accumulate savings up to reach a given amount, usually around 40% of the housing project, before qualifying for a loan on prearranged terms (maturity and interest rate). The Bausapern system is a closed credit system that transforms saving deposits into long-term loans, and is funded only by savings and amortisation payments. This saving scheme is attractive for customers because it benefits from a state contribution to the interest rate.

In the Netherlands a strong security structure facilitates the financing of the social housing sector by reducing credit risk for banks. This mechanism grants financial independence to the Dutch social housing system where housing associations are private, non-profit enterprises who receive no direct public subsidies. Housing associations access bank loans at a favourable interest rate thanks to the guarantee provided by the Fund for Social Housing, whose capital acts as collateral. This Fund is established by housing associations that contribute to its capital via regular payments (the guarantee fee). The Fund grants guarantees to housing associations after an assessment of its creditworthiness, thus affecting its borrowing ability. A supervisory body monitoring governance, integrity and financial management of housing associations (Housing Association Authority) represents the second level of security, and Dutch State and municipalities are the guarantor of last resort.

Denmark provides a successful example of a two-pillar financing mechanism for the social housing sector. The first pillar are State guarantees that allow housing association to access bank credit. State-guarantee commercial bank loans account for almost 90% of the financing for new social housing investment. The second pillar is the National Building Fund, which provides housing association with the financing for renovation, development and investment in existing residential stocks. The National Building Fund is an independent institution that operates outside the state budget as a private fund. It is financed by a share of the rents of social housing tenants and operates as a revolving fund, serving as a savings account for the entire social housing sector.

In South Africa financial sustainability of social rental housing projects is based on cross-subsidisation (higher-income tenants subsidise the rents of lower-income tenants) and government grants, but rents paid by tenants play a larger role. Potential beneficiaries of social rental housing must demonstrate regular income.

Housing Banks in Austria are an example of housing bond financing. They raise private capital through the sale of Housing Construction Convertible Bonds. These bonds are a specific financial tool whose sale is entirely allocated for social rental housing investment. The sale of these bonds provides around 45% of the financing requirements of housing associations for new housing and refurbishment. These bonds bear an interest rate that is 1 percentage point lower than capital market bonds, which reduces costs for housing providers. Despite the lower interest rate, they are an attractive long-term low-risk investment due to a favourable tax treatment, which includes waiving the capital income tax for the first 4 per cent of the coupon rates and a tax deductibility of the purchasing price (Deutsch and Lawson, 2012[29]). It has been estimated that for every euro of foregone tax revenue these bonds generate around 20 euros of investment in affordable housing production (OECD, 2023[25]).

Another example of financial intermediary is the Bond Issuing Cooperative for Limited Profit Housing in Switzerland that raises capital by issuing state-guaranteed bonds. This capital is used to provide cheap loans for non-profit housing construction. Loans from the revolving fund contribute up to 70 percent of the cost of the total project.

The Australian Affordable Housing Bond Aggregator (AHBA) is a financial intermediary that facilitates the financing of affordable housing through the issuance of housing bonds in Australia. The AHBA provides long-term loans on favourable terms to Australian community housing providers (CHPs) by issuing housing bonds. CHPs can use the loans to build and purchase new dwellings, maintenance of existing housing stock and the refinancing of outstanding debt. Loans from the AHBA helped CHPs increase the stock of affordable housing by around 13000 dwelling units between 2018 and 2021.

This financing model also may benefit from issuing social bond. On February 2020, Cassa Depositi e Prestiti S.p.A. (“CDP”) issued its first Social Housing Bond worth 750 million of euro that were allocated to 235 social housing projects that will produce 4226 social housing units for around 11 thousand beneficiaries. A potential issue with this model is that might not suit objective of social housing for the very poor, nor it is clear if the level of rent in these social housing is sufficiently below the market level as to provide an effective alternative.

A social housing sector requires a strict regulatory framework for housing providers and a tight monitoring of the sector, in exchange of the advantages it receives (different type of subsidisation) in recognition of its social function. The regulatory framework should ensure operational efficiency and financial prudence of social housing associations, thus contributing to build up high levels of confidence to all stakeholders. Adequate financial supervision is key to help avoid financial and operational mismanagement and excessive financial risk, especially if housing associations are allowed to invest in activities beyond social housing, which should be avoided. Ensuring prudent financial management is especially important to build up credibility in financing mechanism relying on access to financial markets or commercial bank loans (OECD, 2023[25]; CECODHAS, 2009[27]).

Supervisory authorities could be established at the federal level to control governance, integrity and financial management of the whole sector (housing associations, financial intermediaries), and should be provided with sanctioning powers (financial penalties, appointment of a supervisor). Special financial institutions could also be charged with controlling the financial health of housing associations (e.g., the Fund for Social Housing in the Netherlands). Housing associations might be subject to self-monitoring rules and administrative review that is periodically verified by an auditor set by the housing organisation (e.g., Denmark), thus introducing a first internal layer of monitoring, or produce an annual report in which determine the value of their property on the basis of market value to facilitate greater transparency.

The regulatory framework should ensure that social housing associations provide good-quality housing for the most disadvantaged households. In this respect, the level of the rent paid by social tenants should be based on effective construction costs (e.g., Austria, Denmark, Finland or Switzerland) rather than on tenants‘ income (Australia, Ireland, New Zealand, Japan) or dwelling characteristics and location (the Netherlands and Estonia). Financial and fiscal incentives as well as administrative facilities that reduce the costs of rental housing projects would help lower the level of rent. Setting a fixed term tenancy with renewal subject to reassessment of eligibility, would avoid that tenants whose situation improved might have no incentives to find a different housing solution. In alternative, tenants whose situation had improved and did not fulfill anymore eligibility requirements could remain and pay market rent. Increasing equity in access to social rental housing needs to be weighed against the advantages of social diversity, disincentives effect for economic advancement in case of insecurity of tenure, administrative costs linked to periodic reviews of tenancies.

The lack of affordable and social housing is the main cause of irregular settlements, that are widespread in Mexico. Irregular settlements are illegal if they occupy specific areas (risk areas, areas with a right of way, natural protected areas), irregular if they do not comply with urban regulation and informal if there is no property title. In Mexico around 25% of the population lives in informal dwellings, of which there are between 4 and 7 millions (IMCO, 2011[30]; OECD, 2015[5]).

The regularization of informal settlements has been one of the main strategies to provide land to low-income households, together with subsidies and the purchase of land for urban development (reservas territoriales) (CONEVAL, 2018[6]). However, this strategy has a high cost for inhabitants and the public administration. Inhabitants face insecurity of tenure (vulnerable to eviction and expropriation), lack access to public services and can be located in areas that are unsafe or exposed to natural risks. Municipalities do not always enforce construction standards in informal settlements and while they may tolerate informal settlements out of political interest they may be prone to corruption during the process for their regularisation. Providing services to informal settlements is estimated to cost between 3 to 8 times more than infrastructure provision to a planned development (Aristizabal and Ortiz, 2002[31]). Informal settlements do not pay property taxes.

Mexico should reinforce title formalisation. The National Institute for Sustainable Land (Instituto Nacional de Suelo Sustentable, INSUS) provides a subsidy for the regularization of land tenure and the property registration. Around 42 thousand property regularisations were achieved between 2019 and 2022, against a target population of at least 4 million. A large majority of the population reports problems in the housing registry process (83%) (CONEVAL, 2018[6]).

The city of Bogotá set up a land bank in 1999 (Metrovivienda) to reduce the price of land and boost the supply of affordable housing for low-income families, thus preventing the spread of informal settlements. The land bank would ensure a low land price by buying cheap land in unserviced areas before zoning changes (change in the use of land) or granting planning permission. The land would then be resold to private developers, thus recovering the initial cost of buying and servicing the land. The demand for the new affordable housing was ensured by housing subsidies and credit facilities.

MetroVivienda faced several challenges that slowed its action and partially reduced its effectiveness. The inability of public utilities of quickly servicing the land, lengthy disputes over legal ownership of some plots of land, and hesitation of private developers contributed to delay its action thus lengthening the period of time between purchasing, servicing and reselling the land from the initial estimate of two years to eight years.

The use of housing subsidies led landowners to increase the price of land anticipating the development project, thus preventing from selling cheap urbanised plots to builders, who in turn could not provide affordable housing to the very poorest. To partially address these barriers some changes occurred over time, including a major emphasis on vertical construction to increase densification, the freezing of the price of land at the level of the moment the development project was approved and the involvement of housing associations other than private builders. Over time Metrovivienda stopped acting as a bank land and limited its action to establishing projects in association with local landowners.

Metrovivienda successfully provided high quality infrastructure in its serviced lands and promoted a more widespread densification. However, it failed to provide good and affordable housing for all and reduced but did not stop the spread of informal settlements. External factors heavily hampered its activity, including different political alignment between the city and the national government, structural problems that made it difficult the distributions of housing subsidies, extremely legalistic judicial and planning systems that lengthened the time for its operation and hostility from the construction sector reluctant to develop social housing projects within the city possibly to avoid more intense controls and higher taxes than in less well organised municipalities outside.

Source: (Gilbert, 2009[32]).

Mexico could follow the experience of several OECD countries and use land banks to improve access to cheap land for affordable housing, especially in urban areas, promote a well-ordered urban development and prevent new informal settlements. A land bank usually buys rural land before it is transformed into urban land to secure a part of the increase in value that otherwise would be seized by private landowners and building developers. Thus, land banks are less effective in increasing land supply in central urban areas where the price of land is already high. The example of the city of Bogotá in Colombia (Box 5.8) could be especially relevant for Mexico.

With around 80% of the Mexican population living in urban areas, a share that is projected to increase in the future (Zubicaray et al., 2021[8]), housing and urban policies need to be aligned. However, in Mexico, housing policy is often defined in isolation from transport infrastructure and urban planning. This contributes to urban sprawl that fuels spatial segregation, with vulnerable groups often living in peripheral areas with limited access to jobs, transport and urban services. Unfavourable living conditions in these marginalised areas, in turn, cause widespread house vacancy.

Horizontal and vertical coordination across institutions remains problematic, also because relevant federal agencies bear different visions of urban development (Zubicaray et al., 2020[33]), complicating the task of translating national urban and housing policy into concrete actions. Urban policy is fragmented across levels of government. By law local policies should align with national targets but there is currently no mechanism to actually enforce it. When a new administration takes over (federal, state and municipal), it should produce a new urban development plan that integrates higher-level legislation, but it is not obliged to do so. In addition, environmental and urban planning regulation do not share homogeneous criteria, which leads to further inefficiencies in land management. To obtain a building permit only the environmental or urban planning regulation needs to be met, not both.

Recent changes in governance have positively streamlined the institutional landscape. Since 2018 the Ministry for Agrarian, Territorial and Urban development (SEDATU) has been given authority to lead and coordinate all public agencies involved with housing, transport and urban development and is responsible for achieving the targets set by national housing and urban development policies. Adopting a national common code for urban development, zoning and housing would also help to promote an ordered development. However, to carry out these tasks and its increasing responsibilities SEDATU may need additional funding. Its budget dropped by around one third in real terms between 2019 and 2023.

Municipalities often lack the technical capacity to meet the complex challenges implied by urban development. A key factor explaining the structural weakness of housing and urban planning governance resides in the disparity between resources and responsibilities of municipalities. Municipalities by constitution are responsible for land administration within their jurisdiction and decide on land use (secondary zoning), oversee the cadastral management, set property taxes, and provide public services and infrastructure. However, financial, technical and staff resources available to most municipalities are insufficient to cope with these responsibilities. A large majority of municipalities does not have an urban development plan (INFONAVIT and Fundación-IDEA, 2018[13]) or a modern cadastral system. This implies that, when issuing a building permit, they may be unable to quantify obligations (e.g., conditions, impact fees) imposed upon the developers to offset the extra pressure on urban infrastructure and services.

Municipalities undermine the implementation of national policies as typically they forego updating regulation to integrate higher level government guidelines. For example, few municipalities have integrated environmental criteria in urban planning despite national legislation requiring it. However, federal and state bodies have little control over it. A development project that violates federal or state regulation cannot be prosecuted if the federal/state regulation has not been integrated into municipal legislation on urban planning.

The distribution of urban planning powers across levels of government could be reformulated to prevent irregularities and enforce intergovernmental cooperation. This could be achieved via a new legal framework that clearly defines competence allocation at each level of government. For example, states could be tasked with ensuring that municipalities comply with federal and state urban and housing law. Municipalities could retain the power of proposing secondary zonification that should however be validated by states. This might require a constitutional reform. Alternatively, establishing a federal agency with sanctioning power could help prevent municipalities from violating federal and state legislation when issuing building permits or changing the use of land. Such an agency could follow the model of the Federal Attorney Office for Environmental Protection (Procuraduria Federal de Protección al Ambiente). SEDATU should complete a revision of urban planning legislation across levels of government to identify and resolve contradictions.