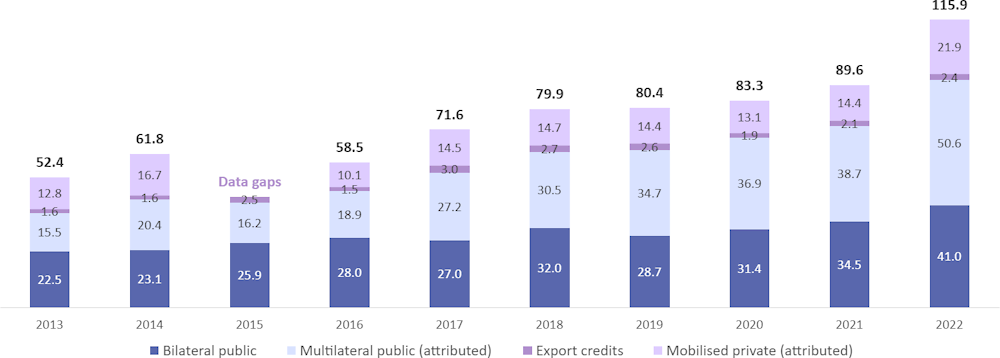

In 2022, developed countries provided and mobilised a total of USD 115.9 billion in climate finance for developing countries (Figure 1 and Table 1), thereby reaching their collective annual goal of mobilising USD 100 billion for climate action in developing countries for the first time. This achievement occurs two years later than the original 2020 target year, but one year earlier than in projections produced by the OECD prior to COP26, which were based on forward-looking commitments and estimates from bilateral and multilateral public climate finance providers. Owing to the very significant and largest year-on-year increase observed to date (up by USD 26.3 billion and 30% compared to 2021), the total for 2022 reached a level that OECD projections had indicated might be achieved by 2025 (OECD, 2021[2]).

Climate Finance Provided and Mobilised by Developed Countries in 2013-2022

Aggregate trends

Developed countries exceeded the USD 100 billion annual goal for the first time in 2022

Figure 1. Climate finance provided and mobilised in 2013-2022 (USD billion)

Note: The sum of components may not add up to totals due to rounding. The gap in time series in 2015 for mobilised private finance results from the implementation of enhanced measurement methods. As a result, grand totals in 2016-22 and in 2013-14 are not directly comparable.

Source: Based on Biennial Reports to the UNFCCC, OECD DAC and Export Credit Group statistics, complementary reporting to the OECD.

Looking at trends for the different components over the available period:

Public climate finance (bilateral and multilateral attributable to developed countries) accounted for close to 80% of the total in 2022 and increased from USD 38 billion in 2013 to USD 91.6 billion in 2022. The increase between 2021 and 2022 was the most significant observed in a given year to date, both in absolute (a USD 18.5 billion rise) and relative terms (25%).

Within public climate finance, multilateral public climate finance grew the most between 2013 and 2022, with a USD 35 billion (226%) increase driven by multilateral development banks (MDBs). Bilateral public climate finance grew by USD 18.5 billion (82%) over the same period.

Private finance mobilised by public climate finance, for which comparable data are only available from 2016, grew from USD 14.4 billion in 2021 to 21.9 billion in 2022 (a USD 7.5 billion or 52% increase), following several years of relative stagnation.

Climate-related export credits remain small and volatile in volumes and, as a result, their share in the total was small throughout the observed period.

Table 1. Climate finance provided and mobilised in 2013-2022 per component and sub-component

|

(Amounts in USD billion) |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Bilateral public climate finance (1) |

22.5 |

23.1 |

25.9 |

28.0 |

27.0 |

32.0 |

28.7 |

31.4 |

34.5 |

41.0 |

|

Multilateral public climate finance attributed to developed countries (2) |

15.5 |

20.4 |

16.2 |

18.9 |

27.1 |

30.5 |

34.7 |

36.9 |

38.7 |

50.6 |

|

Multilateral development banks |

13.0 |

18.0 |

14.4 |

15.7 |

23.8 |

26.7 |

30.5 |

33.2 |

34.3 |

46.9 |

|

Multilateral climate funds |

2.2 |

2.0 |

1.4 |

2.6 |

2.9 |

3.5 |

3.8 |

3.5 |

4.2 |

3.4 |

|

Inflows to multilateral institutions (where outflows are unavailable) |

0.3 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

0.6 |

0.5 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

|

Subtotal (1+2) |

37.9 |

43.5 |

42.1 |

46.9 |

54.1 |

62.5 |

63.4 |

68.4 |

73.1 |

91.6 |

|

Climate-related officially supported export credits (3) |

1.6 |

1.6 |

2.5 |

1.5 |

3.0 |

2.7 |

2.6 |

1.9 |

2.1 |

2.4 |

|

Subtotal (1+2+3) |

39.5 |

45.1 |

44.6 |

48.5 |

57.1 |

65.2 |

66 |

70.2 |

75.2 |

94.1 |

|

Mobilised private climate finance (4) |

12.8 |

16.7 |

N/A |

10.1 |

14.5 |

14.7 |

14.4 |

13.1 |

14.4 |

21.9 |

|

By bilateral public climate finance |

6.5 |

8.1 |

N/A |

5.2 |

4.0 |

3.8 |

5.8 |

5.1 |

5.6 |

9.2 |

|

By multilateral public climate finance attributed to developed countries |

6.2 |

8.6 |

N/A |

4.9 |

10.5 |

11.0 |

8.6 |

8.0 |

8.8 |

12.7 |

|

Grand Total (1+2+3+4) |

52.4 |

61.8 |

N/A |

58.5 |

71.6 |

79.9 |

80.4 |

83.3 |

89.6 |

115.9 |

Note: The sum of components may not add up to totals due to rounding. The gap in time series in 2015 for mobilised private finance results from the implementation of enhanced measurement methods. As a result, grand totals in 2016-22 and in 2013-14 are not directly comparable.

Source: Based on Biennial Reports to the UNFCCC, OECD DAC and Export Credit Group statistics, complementary reporting to the OECD.

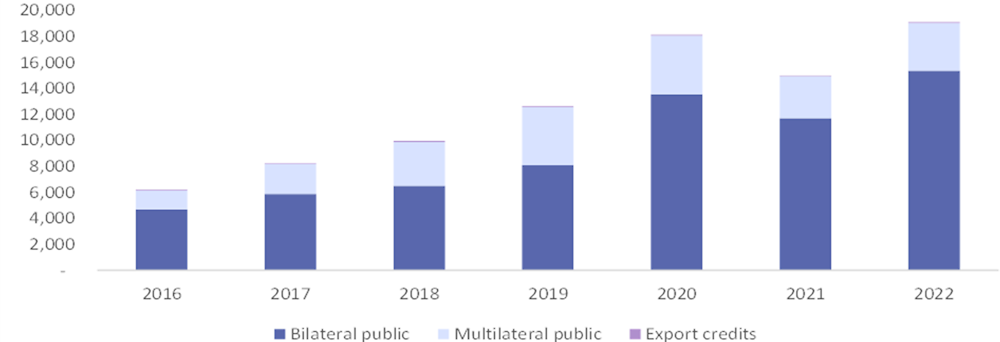

The number of climate finance activities reported by bilateral public finance providers has increased significantly over the years, greatly exceeding the number of activities reported by multilateral public providers, which typically finance a smaller number of much larger projects (Figure 2). The relatively stable number of activities reported by multilateral providers in 2022, compared to the previous three years, indicates a substantial increase in the average size of climate finance projects they track. Subsequent sections of the report, including those on public finance instruments and climate themes, provide further context for these insights on the reported number of activities.

Figure 2. Public climate finance provided in 2016-2022 per number of activities reported

Source: Based on Biennial Reports to the UNFCCC, OECD DAC and Export Credit Group statistics, complementary reporting to the OECD.

Progress towards doubling adaptation finance by 2025 has been made and needs to be maintained

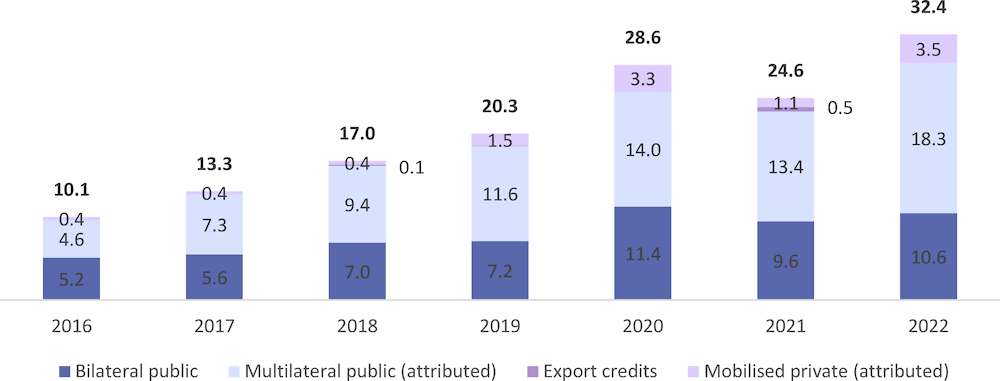

Total adaptation finance provided and mobilised by developed countries increased, despite a small drop in 2021, reaching USD 32.4 billion in 2022 compared to USD 10.1 billion in 2016 (Figure 3). This total amount includes USD 28.9 billion from bilateral and multilateral public sources. Climate finance mobilised from the private sector for adaptation, also grew from USD 0.4 billion in 2016 to USD 3.5 billion in 2022. It is important to note, however, that the significant jumps of private adaptation finance mobilised in 2020 and 2022 are attributable to a small number of large-scale projects.

The 2021 Glasgow Climate Pact called on developed countries to at least double their collective provision of adaptation finance to developing countries from 2019 levels by 2025 (UNFCCC, 2021[3]). Work conducted under the UNFCCC Standing Committee on Finance (UNFCCC SCF) in a 2023 “Report on the doubling of adaptation finance”, addressed issues relating to the baseline for the doubling, methodological challenges and available evidence up to 2020 (UNFCCC SCF, 2023[4]). The outcomes of the first Global Stocktake of the Paris Agreement in December 2023 reiterated the doubling call and urged developed countries to prepare a report in 2024 to assess progress (UNFCCC, 2023[5]).

The amount of adaptation finance tracked by the OECD in 2019 based on data reported by bilateral and multilateral providers was USD 18.8 billion. If OECD public finance figures are taken as the baseline, in 2022, midway between 2019 and 2025, developed countries were about halfway towards meeting the call to double the provision of adaptation finance. Moreover, between 2019 and 2022, adaptation finance mobilised from the private sector more than doubled, from USD 1.5 billion to USD 3.5 billion.

There are in practice a range of challenges and opportunities for international providers to contribute to scaling up adaptation finance in developing countries. These are addressed in a dedicated OECD report on Scaling Up Adaptation Finance in Developing Countries: Challenges and Opportunities for International Providers, which also provides insights for the broader objective of supporting developing countries’ ability to adapt to the adverse impacts of climate change (see Box 1 and (OECD, 2023[6])).

Figure 3. Adaptation finance provided and mobilised in 2016-2022 per component (USD billion)

Note: The sum of components may not add up to totals due to rounding.

Source: Based on Biennial Reports to the UNFCCC, OECD DAC and Export Credit Group statistics, complementary reporting to the OECD.

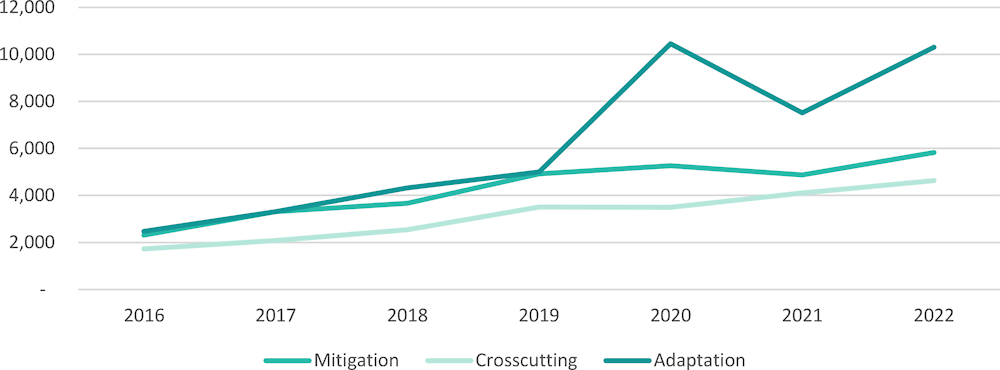

Looking at the overall thematic split of total climate finance provided and mobilised by developed countries (Figure 4), the share of adaptation has progressively increased over the period, from 17% in 2016 and 25% in 2019, to 28% in 2022, owing to a USD 22.3 billion increase over 2016-2022. Nevertheless, mitigation finance, which grew by USD 27.7 between 2016 and 2022, continued to represent the majority in 2022 accounting for 60% (USD 69.9 billion) of the total. Cross-cutting activities that address both mitigation and adaptation also grew, from USD 6.2 billion in 2016 to USD 13.6 billion in 2022, representing a relatively stable 7% to 13% share of the total throughout the period.

Figure 4. Climate finance provided and mobilised in 2016-2022 per climate theme (USD billion)

Note: The sum of individual theme components may not add up to totals due to rounding.

Source: Based on Biennial Reports to the UNFCCC, OECD DAC and Export Credit Group statistics, complementary reporting to the OECD.

It is, however, important to bear in mind that year-on-year variations in the thematic split of climate finance can be influenced by both large individual projects (notably infrastructure) as well as methodologies used by providers to identify the climate theme of activities and determine their climate-specific amount. In this context, Figure 5 illustrates a very rapid growth, since 2019, of the number of activities reported as adaptation finance, except for a dip in 2021. In contrast, total number of activities reports as mitigation finance (as well as cross-cutting) have increased at a much slower but relatively steady pace.

Figure 5. Public climate finance provided in 2016-2022 by climate theme, per number of activities

Source: Based on Biennial Reports to the UNFCCC, OECD DAC and Export Credit Group statistics, complementary reporting to the OECD.

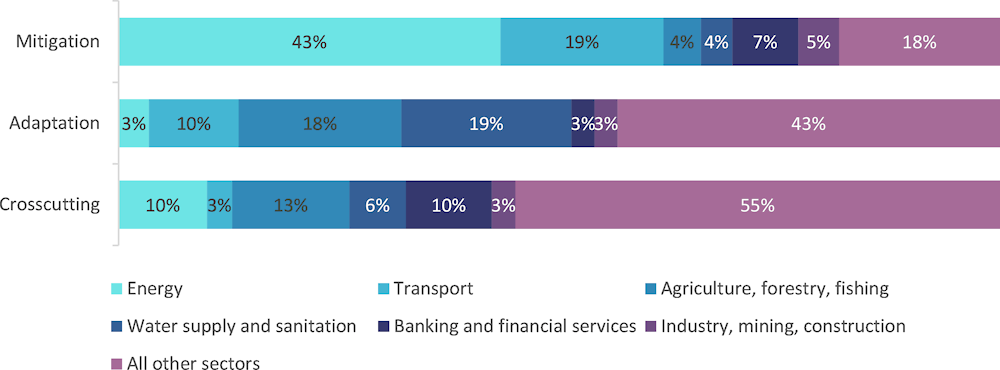

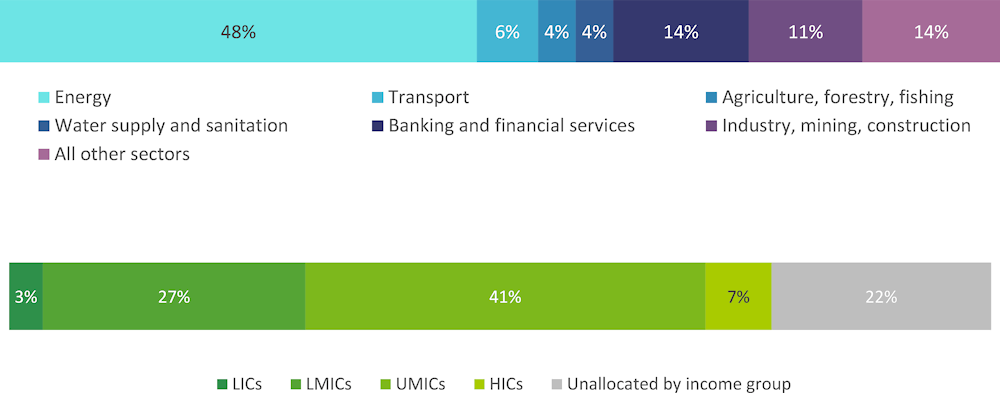

In terms of sectoral distribution (Figure 6), trends remained largely unchanged since 2016. Most mitigation finance focused on activities in the energy and transport sectors. Between 2016 and 2022, these two sectors accounted for more than half (62%) of the total mitigation finance provided and mobilised. In contrast, adaptation finance was more evenly distributed across a larger number of sectors, with the water supply and sanitation sector, along with agriculture, forestry, and fishing, accounting for the largest shares with 19% and 18% of total adaptation finance provided and mobilised respectively.

Figure 6. Sectoral distribution of climate finance provided and mobilised in 2016-2022

Note: “All other sectors” mainly includes activities targeting multisector, general environment protection, government and civil society, social infrastructure and services, and disaster preparedness

Source: Based on Biennial Reports to the UNFCCC, OECD DAC and Export Credit Group statistics, complementary reporting to the OECD.

Box 1. Scaling Up Adaptation Finance in Developing Countries: Challenges and Opportunities for International Providers

There are challenges to financing adaptation action in developing countries, including (i) economic and financial challenges such as limited tax bases, borrowing capacity, rising debt levels, and lack of incentives for private investors due to difficulties in quantifying the impact of climate events and non-financial societal benefits; (ii) technical and knowledge-based challenges, including lack of clear project pipelines, national strategies for adaptation, and difficulty accessing accurate and up-to-date climate data; (iii) institutional and governance challenges such as the increasing fragmentation of the international adaptation finance architecture, diverse eligibility criteria, lengthy review processes for project proposals, and challenges in accrediting national entities to manage funds from multilateral sources.

The 2023 OECD report Scaling Up Adaptation Finance in Developing Countries: Challenges and Opportunities for International providers outlines five action areas to scale-up the provision of adaptation finance, strategically leverage it to attract finance from the private sector, as well as enhance access. These action areas invite international providers of adaptation finance to:

1. Assess the consistency of their forward spending plans with the call to collectively double climate finance for adaptation by 2025, including in coordination with other international providers.

2. Support developing countries’ efforts to strengthen their capacities, policies, and enabling environments for adaptation finance. This involves supporting the improvement of institutional capacity to manage financial resources efficiently and develop sound project pipelines, especially at the local level. A key element relates to supporting the development of policy and regulatory frameworks and tailored financial instruments to incentivise adaptation investment.

3. Strengthen current development practices to improve the delivery of finance for adaptation and support the mainstreaming of adaptation into development assistance. This may include setting internal quantitative targets for adaptation finance or considering windows or minimum levels of funding for the most vulnerable countries. It can also be helpful to move from project-based support to programmatic approaches involving several projects aligned with national priorities. Another important factor involves seeking to streamline and improve interoperability of processes for applications and disbursement of climate finance for adaptation.

4. Deploy blended finance instruments strategically to mobilise private finance for adaptation. This can include using grants to provide early-stage capital to improve the risk-return profile of adaptation investments. Intermediary organisations like DFIs and climate fund managers can help connect commercial investors to adaptation projects using instruments like green bonds.

5. Explore and tap into alternative financing sources and mobilisation instruments for adaptation. Some examples may include exploiting the potential of IMF Special Drawing Rights to scale up adaptation and considering the relevance of debt for nature swaps, including to help address the issue of debt sustainability in developing countries. It is also possible to build on international carbon markets seeking to allocate their proceeds for adaptation activities.

Source: (OECD, 2023[6])

The growth of public climate finance was accompanied by a rise in private finance mobilised

The private sector has a crucial role to play in financing climate action in developing countries. This is especially the case for bridging the investment gap in areas such as clean energy, agriculture, and resilience. In this context, public finance can be utilised strategically to mobilise private finance, notably by employing de-risking mechanisms. The OECD report on Scaling Up the Mobilisation of Private Finance for Climate Action in Developing Countries outlined key opportunities for international providers to support them in these efforts, while also providing insights related to scaling up private finance for climate action in developing countries more broadly (see Box 2 and (OECD, 2023[7])).

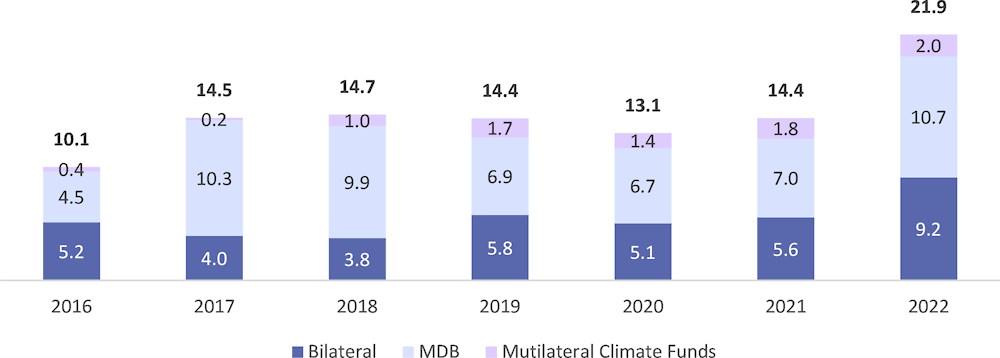

After several years of stagnation, private finance mobilised by public climate finance increased significantly in both relative and absolute terms, reaching USD 21.9 billion in 2022. This represented a 52% (or USD 7.4 billion) increase compared to 2021. The increase was observed across all three categories of public finance providers (Figure 7).

While it is not possible, at an aggregate level, to single out specific explanatory factors, this annual jump is likely to reflect both the strong growth of public climate finance between 2021 and 2022 (which grew by USD 18.3 billion or 25%), as well as some improvements in the effectiveness of such public finance in mobilising private finance. To put this increase into perspective, total mobilised finance for development by bilateral and multilateral providers also grew significantly in 2022 by 27%, from USD 48 billion in 2021 to 61 billion.

Figure 7. Private finance mobilised in 2016-2022 per categories of public climate finance providers (USD billion)

Note: The sum of individual provider group components may not add up to totals due to rounding.

Source: Based on OECD DAC statistics and complementary reporting to the OECD.

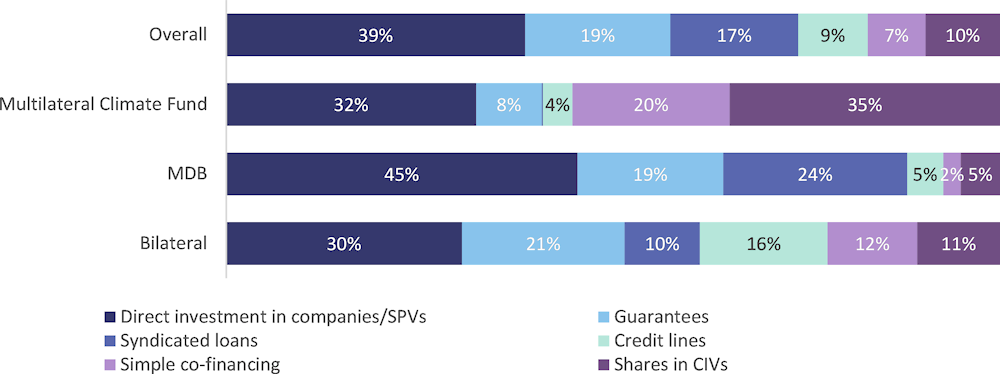

In terms of leveraging mechanisms used by bilateral and multilateral providers for climate change activities, most private climate finance was mobilised through investments in companies and special purpose vehicles, guarantees, and syndicated loans (Figure 8). Different types of public finance providers, however, tend to rely on different mechanisms, reflecting different mandates as well as the need to adapt the choice and use of such mechanisms in different country and sector contexts.

Figure 8. Private finance mobilised in 2016-2022 per leveraging mechanism

Source: Based on OECD DAC statistics and complementary reporting to the OECD.

The sector that benefited the most from the growth in private finance mobilised in 2022 was energy, which, between 2016 and 2022, represented nearly half of total private climate finance mobilised. Similarly, a majority share of private finance continued to be mobilised in middle income countries (Figure 9). More generally, volumes of climate finance mobilised were relatively concentrated in a limited number of developing countries. Between 2016 and 2022, the top 5 recipient countries benefitted from 28% of total climate finance mobilised. This share reaches 41% if considering the top 10 countries and 57% if considering the top 20 countries. This trend results in part from important volume of private finance being mobilised for a limited number of large infrastructure projects.

Figure 9. Private climate finance mobilised in 2016-2022 per sectors and income groups

Note: All other sectors” mainly includes activities targeting general environment protection, multisector, social infrastructure, and services

Source: Based on OECD DAC statistics and complementary reporting to the OECD.

Box 2. Scaling Up the Mobilisation of Private Finance for Climate Action in Developing Countries: Challenges and Opportunities for International Providers

A number of challenges can affect the potential for mobilising private climate finance in developing countries. These include overall enabling conditions for investment in beneficiary countries (e.g., macroeconomic stability, political risk, and regulatory environments, availability of technical expertise, cost of due diligence and monitoring), as well as commercial dynamics in some climate action areas that lack sufficiently appealing risk-return profiles to attract large-scale private investment. Additionally, individual projects are often too small to secure significant commercial funding. Further, objectives, mandates, and operating models of development actors deploying international public climate finance tend to be dominated by public sector exposures, limited private sector engagement, and capital-intensive loan-focused models that limit the potential to mobilise private finance.

The 2023 OECD report Scaling Up the Mobilisation of Private Finance for Climate Action in Developing Countries: Challenges and Opportunities for International Providers outlines three key action areas that can help international providers enhance their role in private finance mobilisation:

1. Tailor project- and country-level interventions to de-risk projects and markets. This can include emphasising blended finance and mobilisation in mature sectors such as renewable energy. International providers can reorient loans towards mobilising private finance within these sectors and scale up guarantee usage, while, at the same time, providing capacity-building for improved investment conditions and project pipeline development. A key point is to gradually exit projects as they become commercially viable to allocate resources to new climate priorities.

2. Scale up the use of cross border financing mechanisms and improve co-ordination to channel global finance. This involves strengthening co-ordination and collaboration between bilateral and multilateral climate finance providers, domestic actors, and the private sector. To facilitate investments, international providers could also enhance their efforts in developing secondary assets that aggregate smaller constituent projects in developing countries into larger, rateable, tradeable assets.

3. Enhance international institutions to maximise the mobilisation potential of public climate finance. This may involve requesting clearly defined institutional private finance mobilisation targets from MDBs, developing risk transfer mechanisms and providing local currency financing, along with co-lending approaches and syndication platforms. Additionally, there is a need to further improve data disclosure and transparency on accounting methodologies relating to public climate finance and the private finance it mobilises.

Source: (OECD, 2023[7]).

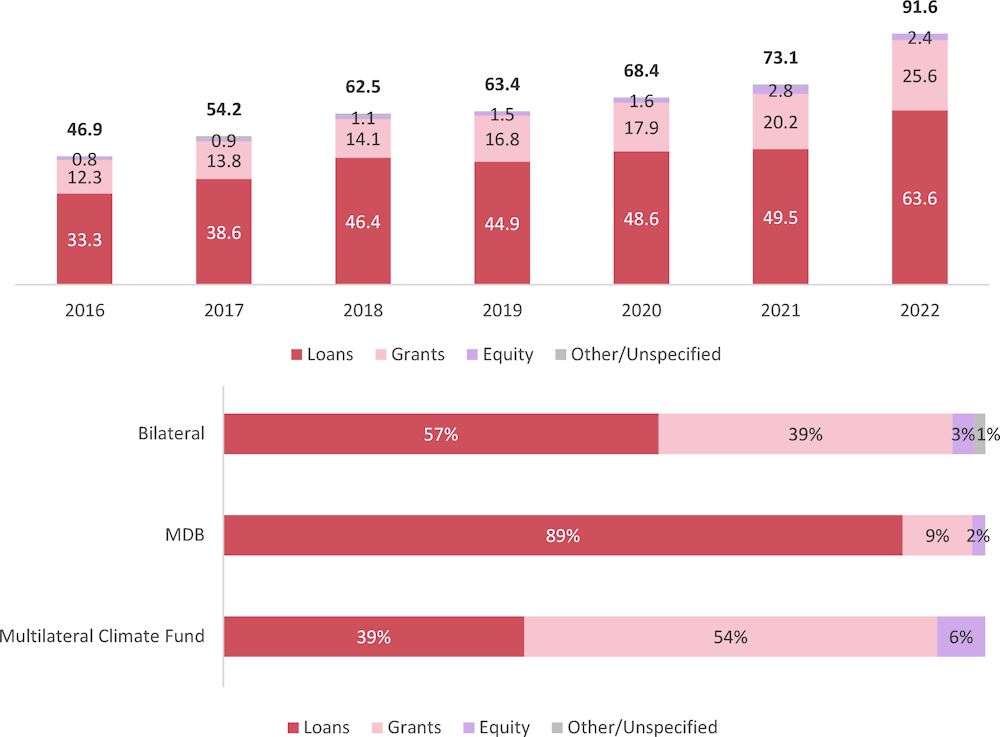

Loans represented the lion’s share of public climate finance, but grants were prioritised in lower-income countries

In 2022, as in previous years, developed countries’ public climate finance provided bilaterally and through multilateral channels mainly took the form of loans (69% or USD 63.6 billion) and, to a lesser extent, grants (28% or USD 25.6 billion), while volumes of equity investments (whether in companies, projects, or funds) remained small (Figure 10). Between 2016 and 2022, the annual level of grants increased by USD 13.4 billion, more than doubling with a 109% growth, outpacing the 91% grown in public loans, which increased by USD 30.3 billion.

The instrument mix between types of providers varied, reflecting different and complementary mandates of providers and, as a result, different types of activities within their portfolios. Over the period 2016-2022, close to 90% of financing provided by MDBs took the form of loans (with relatively large individual project size as illustrated in Figure 10). In contrast, the mix was comparatively more balanced for multilateral climate funds (39% loans, 54% grants) and bilateral providers (57% loans, 39% grants), both of which tend to fund a relatively larger and more diverse range of activities and projects (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Public climate finance provided in 2016-2022 per financial instruments (USD billion)

Note: The sum of individual instrument components may not add up to totals due to rounding.

Source: Based on Biennial Reports to the UNFCCC and OECD DAC statistics, complementary reporting to the OECD.

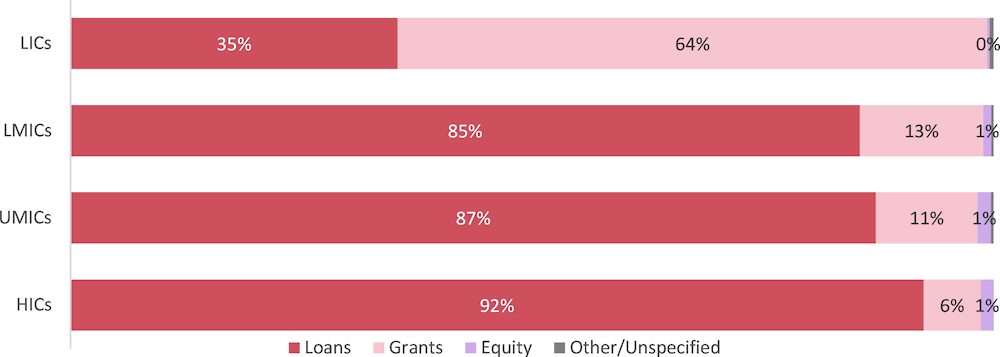

As per Figure 11, the relative use of different public finance instruments showed small variations between developing countries that are high-income countries (HIC), upper-middle countries (UMIC) or lower-middle-income countries (LMIC), with loans representing respectively 92%, 87% and 85% of public climate finance provided over 2016-2022. On the other hand, grant financing was significantly higher in lower-income countries (LIC), where it accounted for 64% of total public climate finance provided, owing to specific needs (e.g., adaptation, capacity building) as well as circumstances (more risky and fewer projects with the ability to pay back debt). Indeed, over 2016-2022, a larger share of adaptation (38%) and cross-cutting (55%) public finance was provided through grants, compared to mitigation, where only 15% was grant-funded.

Figure 11. Public climate finance provided and mobilised in 2016-2022 per developing country income group and financial instrument

Source: Based on Biennial Reports to the UNFCCC and OECD DAC statistics, complementary reporting to the OECD.

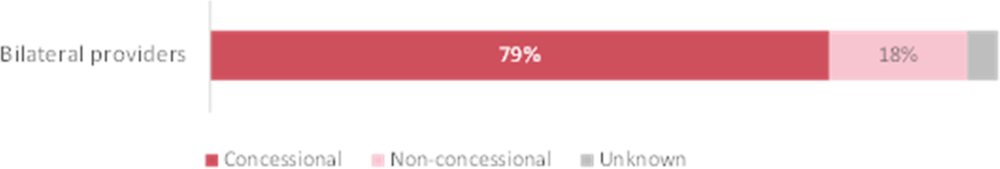

Box 3. Concessional and non-concessional loans

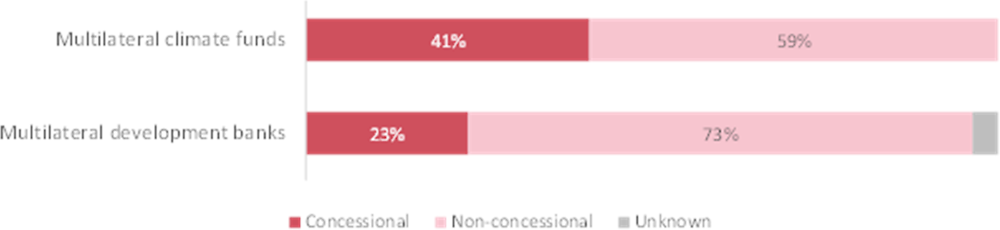

A concessional loan is extended to a borrower on more preferential terms than those available on the market, including below-market interest rates, extended grace periods, or a combination of both. Between 2016-2022, 79% of loans extended by bilateral providers were concessional (Figure 12). In contrast 41% and 23% of loans extended by multilateral climate funds and MDBs respectively were concessional (Figure 13). However, due to definitional differences, these percentages are not comparable to the percentages for bilateral providers. Indeed, the reporting of concessional and non-concessional loans is underpinned by different definitions for DAC members on the one hand and for multilateral institutions on the other.

For DAC members, concessionality is a key ODA-eligibility criterion; only concessional loans are currently included in ODA. For sovereign loans to be concessional, their grant element (calculated based on interest rate, grace period, maturity, repayment schedule, and discount rate) needs to be at least 45% for LDCs and other LICs, 15% for LMICs, and 10% for UMICs and multilateral institutions. Currently, loans to the private sector need to convey a grant element of at least 25% to be concessional. Furthermore, the terms and conditions of ODA loans have to be consistent with the IMF Debt Limits Policy or the World Bank’s Non-Concessional Borrowing Policy.

Figure 12. Bilateral climate finance loans in 2016-2022 by type of concessionality

Source: Based on Biennial Reports to the UNFCCC and OECD DAC statistics, complementary reporting to the OECD.

For lending by the MDBs and multilateral climate funds, concessionality relates to their ability to offer credit on financially sustainable terms, based on their own financing costs. Multilateral institutions require external grant resources to extend concessional loans. Conversely, non-concessional loans are sustainable based on the institutions' low funding costs and preferred creditor status, allowing them to offer better terms than the market. The use of concessional or non-concessional loans by multilateral organisations depends on the recipient country’s income level as well as considerations for its creditworthiness and debt sustainability.

Figure 13. Multilateral climate finance loans in 2016-2022 by type of concessionality

Source: Based on Biennial Reports to the UNFCCC and OECD DAC statistics, complementary reporting to the OECD.

Climate finance grew across all developing country groupings, with distinct patterns in SIDS and LDCs

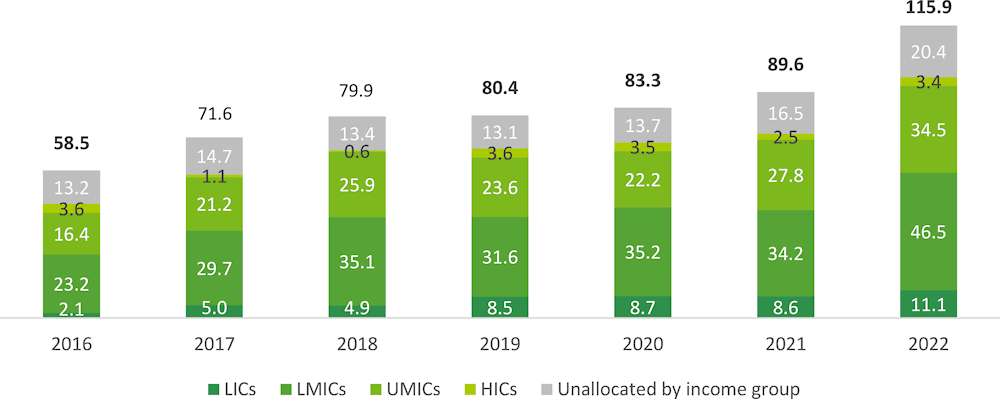

In terms of income groups, LMICs were the main beneficiaries, accounting for 40% (USD 46.5 billion) of total climate finance provided and mobilised in 2022, increasing from USD 23.2 billion in 2016 accounting for a similar share (Figure 14). The share represented by UMICs was similarly stable (30% in 2022, 28% in 2016). The share of finance provided and mobilised for LICs represented 10% in 2022. However, in absolute terms, finance for LICs showed a five-fold (USD 9 billion) increase since 2016. As much as 18% of climate finance provided and mobilised by developed countries could not be allocated to a specific income group, owning primarily to activities with a regional or multi-country scope at the point of reporting.

Figure 14. Climate finance provided and mobilised in 2016-2022 per developing country income grouping (USD billion)

Note: The sum of individual income group components may not add up to totals due to rounding.

Source: Based on Biennial Reports to the UNFCCC, OECD DAC and Export Credit Group statistics, complementary reporting to the OECD.

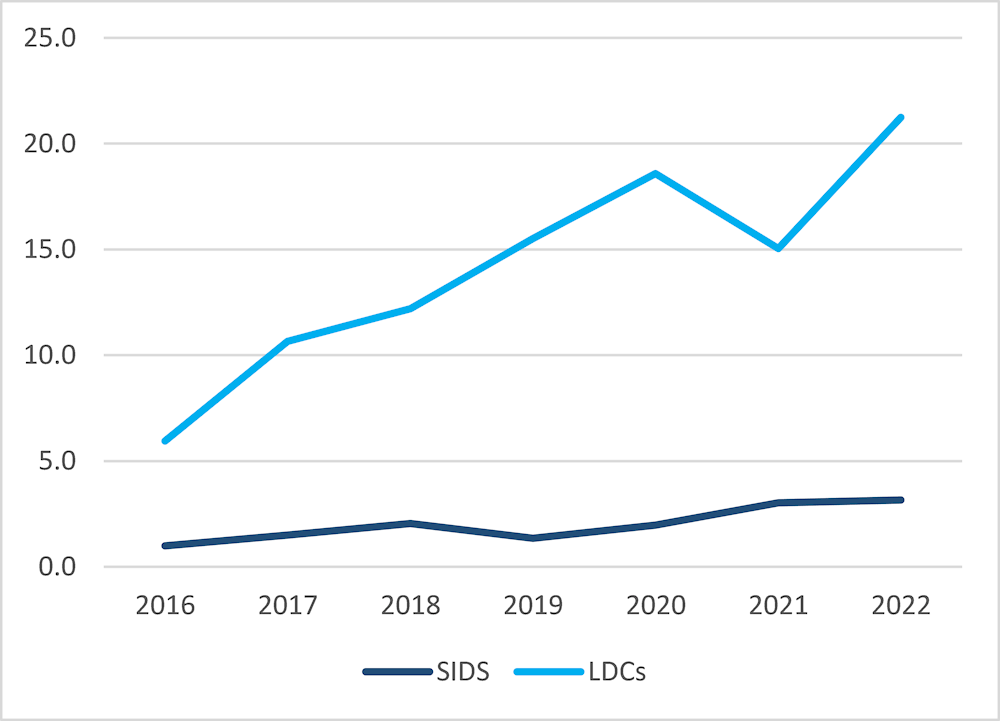

Over the observed years, there was almost continuous growth in volume for both Least Developed Countries (LDCs) and Small Island Developing States (SIDS). Climate finance for LDCs surpassed the USD 20 billion mark for the first time in 2022, reaching USD 21.2 billion. Climate finance for SIDS multiplied more than three folds since 2016, reaching USD 3.2 billion in 2022. Between 2016 and 2022, LDCs and SIDS benefitted, respectively, from an annual average of USD 14.2 billion (17% of total climate finance provided and mobilised), and USD 2 billion (2%) (Figure 15). In terms of per capita amounts, on average during the observed timeframe, SIDS benefitted from USD 96 and LDCs benefitted from USD 16. In contrast, over the same timeframe, all developing countries benefitted from USD 25 per person annually.

Figure 15. Climate finance provided and mobilised in 2016-2022 in SIDS and LDCs (USD billion)

Source: Based on Biennial Reports to the UNFCCC, OECD DAC and Export Credit Group statistics, complementary reporting to the OECD.

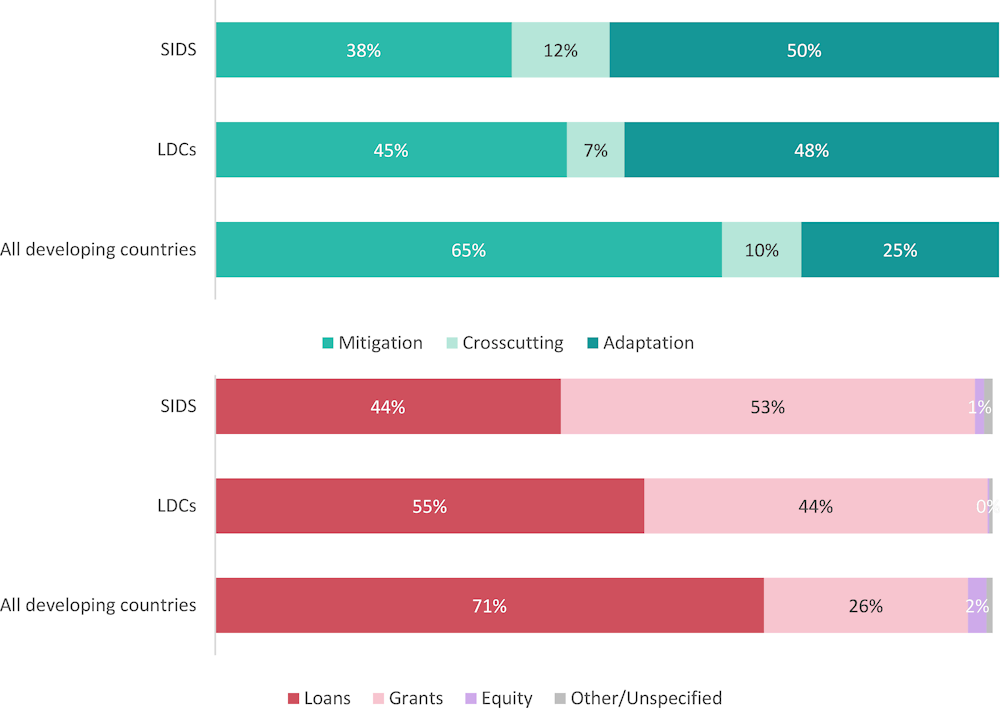

Importantly, over the period 2016-2022, both LDCs and SIDS adaptation represented a higher share of climate finance (close to half) in comparison with all developing countries (a quarter) (Figure 16). The share represented by private mobilised finance was significantly lower for LDCs (7%) and SIDS (9%) compared to an average of 18% across all developing countries. This underscores the challenges faced by these countries in attracting private investment for climate action and the need for tailored efforts to help address these challenges (OECD, 2023[7]). Similarly, both SIDS and, to a lesser extent, LDCs, received overall a higher share of grants compared to all other developing countries. The majority (53%) of public finance provided to SIDS was in the form of grants, while slightly less than half (44%) of the public finance provided to LDCs was in grant-based.

Figure 16. Thematic and instrument split of climate finance provided and mobilised in 2016-2022 in SIDS and LDCs

Source: Based on Biennial Reports to the UNFCCC, OECD DAC and Export Credit Group statistics, complementary reporting to the OECD.

Multilateral climate finance providers are playing an increasingly important role in the provision and mobilisation of climate finance

Figure 1 and Table 1 at the start of this report highlight that multilateral providers represented a very significant and growing proportion of total climate finance accounted for as provided and mobilised by developed countries. Within this component, it is important to distinguish between MDBs and climate funds as these two sub-categories tend to operate differently in terms of resources, mandates, and operations.

Table 7, found in the Data and Methods chapter, provides a full list of institutions covered in this report (noting the addition, for 2022 data, of the IMF’s Resilience and Sustainability Trust (RST)) and the institution-specific percentages used to attribute to developed countries a share of the climate finance they provide and mobilise. Such attribution percentages range from 4.8% to 100% depending on the institution, and as illustrated in Box 4, implying that the remaining share of climate finance provided and mobilised by multilateral institutions is attributable to developing countries.

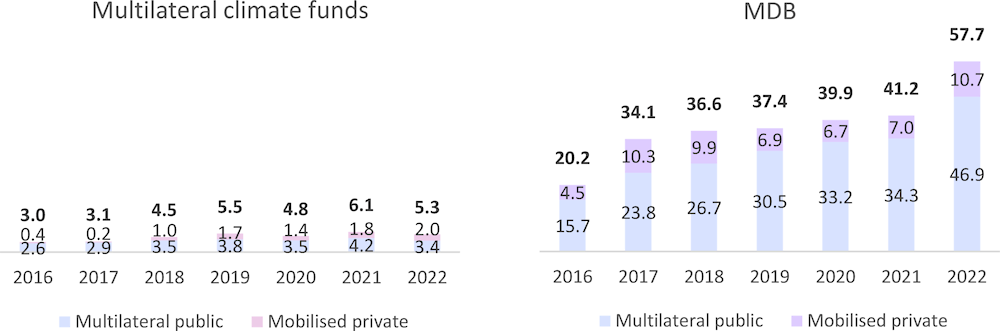

As per Figure 17, total climate finance provided and mobilised by MDBs (attributed to developed countries), has grown continuously since 2016 and played a critical role in contributing to the USD 100 billion goal being reached in 2022, notably through the provision of loans. In contrast, volumes of climate finance recorded for multilateral climate funds (for which the developed countries attribution share is close to 100% in almost all cases) remain relatively more modest and have tended to vary year-on-year since 2019, after a period of regular growth between 2016 and 2019.

Figure 17. Climate finance provided and mobilised by multilateral development banks and climate funds per components in 2016-2022 (USD billion)

Note: The sum of individual components may not add up to totals due to rounding

Source: Based on OECD DAC statistics

Looking specifically at volumes of private finance mobilised, it is important to note that some multilateral institutions are explicitly mandated to finance areas that generally attract little or no private finance investment, such as lending to government. Data limitations do not allow a transaction-level analysis in this area.

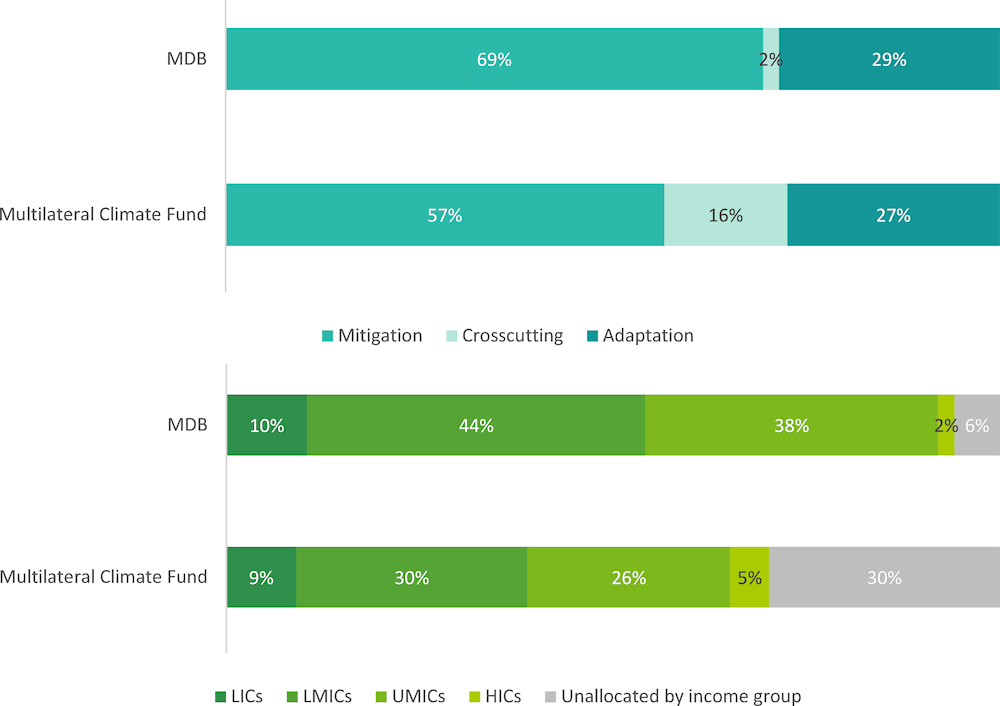

The comparative distribution per climate theme and recipient income group of climate finance provided and mobilised by MDBs and climate funds over 2016-2022 provides two aggregate-level insights (Figure 18). First, the share of adaptation finance was similar across the two provider groups, despite differences in climate finance tracking methodologies (e.g., climate funds often categorise adaptation finance as cross-cutting, a category rarely used by MDBs), and in project characteristics (MDBs fund very large projects, whereby a significant amount of adaptation finance will be recorded if a high climate-specific component is applied). Second, a very significant portion of climate finance provided and mobilised by climate funds could not be allocated to a specific income group at the point of reporting. Notwithstanding this issue, the income group distribution appears relatively similar, with LMICs representing the largest share, followed closely by UMICs and, with significantly lower shares, LICs and developing country HICs.

Figure 18. Climate finance provided and mobilised by multilateral development banks and climate funds in 2016-2022 by climate theme and recipient income group

Source: Based on OECD DAC statistics.

Box 4. Multilateral public climate finance attribution to developed and developing countries

The scope of the USD 100 billion goal refers only to climate finance provided and mobilised by developed countries, including through multilateral channels. The Data and Methods chapter of the report details, for each multilateral development bank and climate fund, the calculated share of its outflows (as well as of the private finance mobilised by such outflows) attributable to developed countries included in this report.

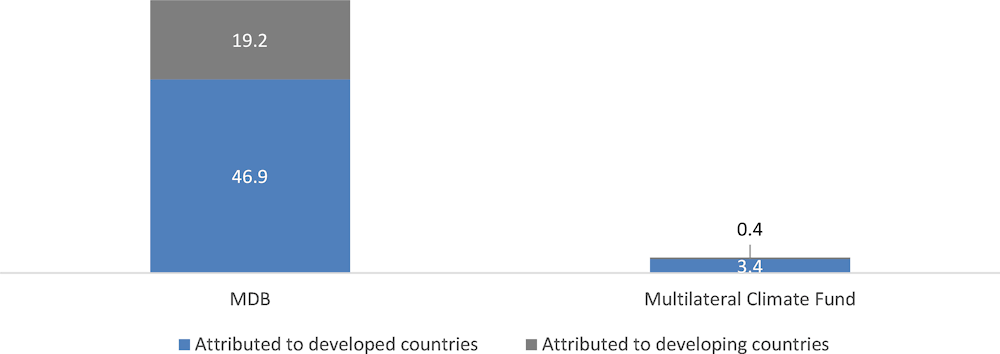

Figure 19 presents, for 2022, the resulting volume of multilateral public climate finance outflows attributed to developed countries, i.e., USD 46.9 billion for MDBs and USD 3.4 billion for climate funds, which are accounted for in the USD 100 billion accounting framework. However, this figure also shows to the volumes attributable to developing countries, i.e., USD 19.2 billion for MDBs and USD 0.4 billion for climate funds. Indeed, many developing countries are shareholders of MDBs and some, more rarely, contribute to multilateral climate funds.

Figure 19. Total public climate finance provided by multilateral development banks and climate funds in 2022 attributed to developed and developing countries

Note: While this report provides a full list of countries categorised as providers or beneficiaries of climate finance respectively in the context of OECD work to track progress towards the USD 100 billion goal, it is without prejudice to the definition of developed countries. In this box, the use of “developed” and “developing” countries reflects the list of countries used for the rest of the analysis presented in this report and detailed in the Data and Methods chapter.

Source: Based on OECD DAC statistics and attribution percentages as detailed in Table 7.