This chapter summarises the main findings and recommendations of the Performance Assessment Framework for Economic Regulators (PAFER) review of Brazil’s national water and basic sanitation agency (Agência Nacional de Águas e Saneamento Básico – ANA). The recommendations aim to strengthen the regulator’s organisational performance and governance structures.

Driving Performance at Brazil’s National Agency for Water and Basic Sanitation

1. Assessment and recommendations

Abstract

This chapter assesses the main issues that Brazil’s national water and sanitation agency (Agência Nacional de Águas e Saneamento Básico, ANA) faces in terms of its governance and performance, and outlines areas of recommendation – ways in which ANA could continue good practice, address changing needs and challenges, or react to areas of opportunity. Relevant case study examples submitted by peers from the OECD’s Network for Economic Regulators (NER)1 are included to help illustrate potential ways forward or indicate enabling tools for ANA to consider.

Introduction

ANA has been central to the implementation of the National Water Resources Policy (PNRH) – the key legal instrument governing the country’s water resource management (WRM) since the agency’s founding in 2000. In delivering its duties in WRM, ANA has shown leadership and the capability to engage stakeholders and build capacity within a complex sector structure to implement policy and improve compliance. In addition, since 2010, ANA has been involved in the regulation of dam safety, in line with the National Dam Safety Policy. This additional task requires specific skills and significant co-ordination, which, in combination with ANA’s duties regarding reservoir operations, will become even more important as water availability, demand, and usage changes.

The agency is now at an important juncture. In 2020, ANA’s mandate was extended to include functions in the water supply and sanitation (WSS) sector. Here ANA is tasked with developing national reference standards and support and monitor their adoption by subnational regulatory agencies (Law No. 14.026, 2020[1]), stepping into a role akin to “the regulator of the regulators”. These reference standards cover issues of governance, universal access, service quality and technical matters, such as tariff-setting, for each of the four WSS service areas: drinking water supply; the collection and treatment of sewage; urban cleaning and solid waste management; and urban rainwater management and drainage (see Chapter 3). The adoption of effective reference standards, which is fundamentally the responsibility of subnational regulatory agencies and municipalities, is an essential stepping-stone on Brazil’s path to meet national goals for universal water supply and sewage collection and treatment. Today, 44% of Brazil’s population are not covered by sewage collection and treatment services and 16% of the population are not supplied with drinking water, with stark differences between urban and rural areas (see Chapter 2).

The agency is adapting to its new role and delivering its duties in a complex context. The WRM and WSS sectors, which are inevitably connected, face significant challenges, including the uneven distribution of Brazil’s water wealth, the impacts of climate change and other external shocks, and a complex multi-layered governance system (OECD, 2022[2]).

The following sections of this chapter assess six issues and areas of recommendation identified as part of the review process, relating to: clarifying ANA’s role and addressing misalignment between ANA’s mandate, mission and regulatory powers; building analytical capabilities in the economics of water and sanitation; designing and organisation that supports accountability and the efficient delivery of outcomes for citizens; operating within financial and human resource constraints; promoting a culture of independence and integrity during institutional change management; and, lastly, boosting transparency and access through data and digital transformation.

First, ANA, as the federal regulatory agency, takes responsibility for setting national standards in WSS and implementing policies in WRM with the final aim to improve regulatory outcomes in the relevant sectors and for citizens. ANA holds a wide variety of important functions, however, ANA’s regulatory powers in WSS are not aligned with policy goals, which constrains the agency’s ability to influence final outcomes (Issue 1). Furthermore, in WRM, ANA may depend on other actors, particularly at the state level, to help manage challenges or effectively and efficiently achieve its stated objectives for Brazil. To mitigate reputational risks, support policy ambitions and help achieve the regulator’s mission, ANA can seek to clarify its role with stakeholders and identify ways to address structural weaknesses in its regulatory toolkit.

Second, decision makers at the subnational level in both WRM and WSS, where institutions vary in capacity and capabilities, will require guidance and an independently developed evidence base to support their deliberation processes. ANA, as a well-respected institution with experience in an advisory and capacity-building role in WRM, is well-placed to fulfil this need, but, as the responsibilities of the institution transform, the skills the agency requires will have to transform as well (Issue 2). ANA may look to increase its capacity and capability in the economics of water and sanitation as a priority in this regard, having already developed a good reputation and expertise in hydrology and many other scientific and technical areas relating to water resource management.

Organisational change, in the form of a new mandate, new leadership and new ways of working, presents both opportunities and risks. Two risks relating to regulatory governance identified in this review concern lines of accountability (Issue 3) and promoting a culture of independence and integrity (Issue 5). Since ANA’s reorganisation in 2022, ANA’s organisational structure continues to be adapted to reflect new requirements and challenges. This organic growth in the organisation risks sight of ANA’s mandate and core deliverables being lost and lines of accountability disrupted – essentially, ANA’s mandate spans three sub-sectors (water resource use regulation and water resource management, dam safety, and water supply and sanitation). Changes have proceeded at a fast pace, impacting staff, and creating a challenging environment for the design of new units and governance processes that function in an inclusive and effective manner, whilst promoting a culture of integrity.

It is important to recognise that ANA is operating within constraints, impacting the agency’s financial autonomy and ability to manage human resources (Issue 4), which has partly shaped the organisation’s choices on how to structure itself and adapt to its new mandate. These constraints have already been acknowledged in independent reporting conducted by the Federal Court of Accounts (Tribunal de Contas da União, TCU) (see Chapter 3) (TCU, 2021[3]) but remain applicable at the time of this review, since addressing these constraints requires revision of the legislative and governance framework and therefore significant political co-ordination and willingness to reform.

Finally, ANA plays a leading role for the water sector in terms of data collection and dissemination, knowledge sharing and reporting. However, not all information, reporting and data resources are easily accessible and tailored to stakeholders’ needs (Issue 6). Digital tools, data and technology, and their governance, can enable new ways of working, and underpin ANA’s ability to meet the information and interaction needs of regulated entities and citizens in an inefficient and effective way. As these areas continue to evolve at a fast pace, ANA must ensure digital and data governance remains fit-for-purpose and forward-looking. At the same time, ANA can engage with other institutions to ensure data-related tasks are not being duplicated and ANA may choose to continue its leading role and co-ordinate data management activities, so as to reduce resource-use inefficiencies for all involved.

Clarifying ANA’s role and addressing misalignment between ANA’s mandate, mission, and regulatory powers

Issue 1: ANA’s wide-ranging activities reflect national policy ambitions to strengthen water resource management and improve water supply and sanitation across the country. However, the powers to directly regulate providers of water supply and sanitation services or take final decisions relating to water management are not always held by ANA as the federal regulator. In WSS, regulatory powers lie primarily with subnational authorities whilst ANA takes responsibility for setting non-binding national standards. Whilst ANA is well-placed and trusted to lead on standard-setting, a mismatch between roles and regulatory powers may impact its ability to improve policy outcomes in WSS and present reputational risks for the regulator if ANA’s role is not well understood and expectations are not effectively managed. In WRM, whilst ANA holds direct powers within the Union’s domain on certain issues, the agency is required to co-ordinate decisions with multiple stakeholders to progress outcomes for the sector and does not take regulatory decisions outside of the Union’s domain.

Assessment

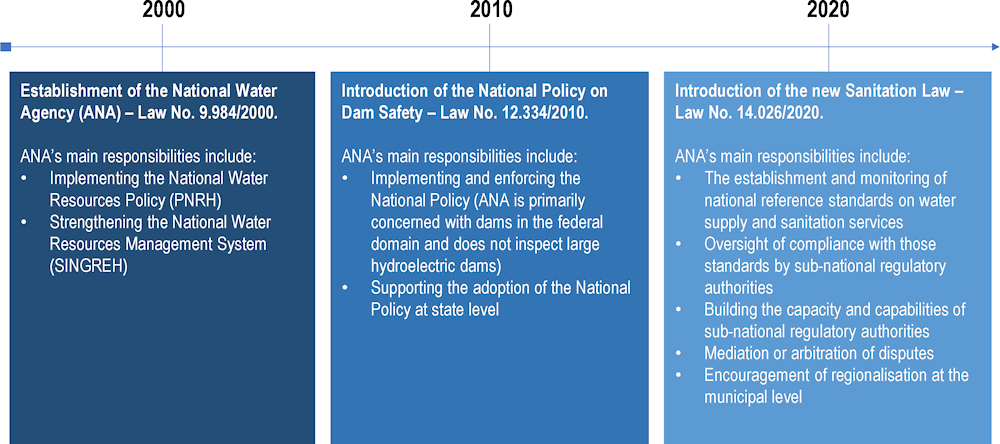

ANA has experienced two significant expansions to its mandate since its founding, reflecting the trust and good reputation the agency has built as a technically competent and responsive agency. After operating as the National Water Agency for more than a decade since its founding in 2000, tasked with water resource management, ANA’s mandate expanded first in 2010, with the introduction of a new role under the National Policy for Dam Safety (Law No. 12.334, 2010[4]). More recently in 2020, the new Sanitation Law (Law No. 14.026, 2020[1]) expanded the regulator’s mandate into water supply and sanitation services, where ANA is tasked with developing national reference standards and supporting and monitoring their adoption by subnational regulatory agencies (see Chapter 3).

Figure 1.1. Evolution of ANA's mandate

ANA holds a wide variety of important functions, some of which go beyond traditional economic regulatory functions. ANA holds direct regulatory powers in relation to a number of its roles, for example in its duties to regulate bulk water supply and water-use concessions for irrigation, or to inspect and enforce compliance with operational and safety rules for certain types of reservoir and dams. There are also many instances when ANA’s role is closer to that of capacity-builder, facilitator, co-ordinator, or expert advisor. ANA has chosen to adopt “softer” tactics to influence sector outcomes in cases where subnational regulatory authorities have not taken the initiative. ANA shows effectiveness in relation to areas where it holds direct regulatory powers and has made great efforts in its engagement and role as co-ordinator and advisor in other areas. Looking forward, ANA’s reputation of effectiveness may need to be leveraged during engagement with stakeholders, together with new evidence as it becomes available, to achieve greater influence and impact.

ANA’s stakeholders, and ANA itself, hold high expectations for the agency’s contribution to delivering ambitious policy goals in a challenging context. For example, Brazil’s policy aims to achieve the universalisation of water supply and sanitation services by 2033. Reaching this goal will require significant investment and the co-ordination of multiple actors across Brazil’s multi-layered political system, but also beyond the public sector with private providers, investors, and sector experts. ANA is looked-to to provide leadership via the development of national reference standards and has set itself similarly challenging objectives by incorporating progress on policy objectives in its strategic planning. The new sanitation framework was envisaged to encourage the participation of private sector investment, and this remains a priority and expectation for many stakeholders, though ANA’s reference standards do not necessarily need to address the means, or structures of ownership, through which outcomes are delivered.

Considering the scale of the challenge and importance of ANA’s work to develop national reference standards in WSS, ANA’s regulatory powers are not aligned with policy goals, which constrains the agency’s ability to influence final outcomes. The direct regulation of water supply and sanitation service providers remains the responsibility of state and municipal regulatory authorities. While ANA develops the national reference standards for WSS, it has no powers to enforce them. Subnational regulatory agencies may adopt ANA’s reference standards on a voluntary basis. Service providers at the municipal level may avoid requirements to comply with ANA’s standards by altering the regulatory agency to whom they are accountable – under Brazil’s framework, providers do not need to be regulated by their state agency but may choose an agency in another state or municipality, as long as at the appropriate level.

The necessary resources and incentives to support the adoption of ANA’s WSS reference standards by subnational authorities are currently lacking or apply unevenly. The current incentive structure is based on conditional federal funding, which municipalities will receive when they are regulated by subnational regulators complying with the national standards. However, access to federal funding is unlikely to guarantee adoption in cases where local political will is governed by narratives of sovereignty and control – the regionalisation of service provision (the creation of municipal blocks) is key to improving access, especially for rural areas, by delivering necessary economies of scale and enabling cross-subsidisation. ANA does not have any powers to impose regionalisation, which must be implemented by municipal authorities working in co-operation. Sanitation may not be identified as a priority at the local municipal level, which could be addressed through collaboration with subnational regulatory agencies and discussion of the evidence (discussed under Issue 2). Addressing the issue of incentives and strengthening measures to mitigate non-compliance are key to making change happen and building momentum at the local level.

In WRM too, whilst ANA’s holds greater regulatory powers, there are certain situations where ANA depends on other actors to help manage challenges or to achieve its stated objectives. In water resource management, ANA’s direct regulatory powers apply within the Union’s domain2 and, given the scale of this domain, this translates to a significant set of powers: to directly regulate bulk water supply and water-use concessions for public irrigation, define allocation rules and priority resource uses, and set overarching regulatory frameworks for resource management. However, at the state level, regarding the management of state rivers and bodies of water, ANA lacks direct regulatory powers, and is required to co-ordinate closely with state water management agencies and basin committees to strengthen the National Water Resources Management System (SINGREH) and deliver the PNRH. Whilst ANA provides financial support, technical expertise, guidance and capacity building, most decisions on water management are made by the relevant basin committee or state water management agency. For the country to make informed, integrated decisions to ensure water resources are sustainably managed, resilient, and sufficient to meet changing needs and pressures, ANA will be required to continue to influence the sector through its coordination and engagement with state water management agencies and river basin committees. This effort becomes even more important in the face of trends such as climate change, population growth and urbanisation (see Institutional and Sector Context for a more detailed discussion).

An ingredient in ANA’s success so far has been its ability to build capacity across the sector and develop positive working relationships. ANA has developed different, proportionate modes of engagement to achieve different objectives, reflecting instances when ANA holds a capacity-building or administrative rather than regulatory role. At the same time, ANA has successfully co-ordinated the national hydrometeorological monitoring network (RHN) and managed the National Water Resource Information System (SNIRH), which together provide the sector with operational data and builds transparency. ANA has shown itself to be open and proactive, organising long-term co-operation agreements and research programmes with key stakeholders to receive external perspectives on current issues or develop horizon scanning work. There may be further opportunities to formalise a more inclusive, multi-stakeholder advisory group for similar purposes and to develop two-way engagement.

Role clarity and expectation management

At a time when stakeholders’ understanding of ANA’s role is low, expectations and policy ambitions are high, and the powers of the regulator are limited, there is increased reputational risk. ANA has a strong reputation, one of the reasons why its mandate was expanded in 2020. However, a lack of understanding of ANA’s role and responsibilities has been shown from a range of stakeholders, from public officials to consumers. This is evidenced by feedback received by the agency during its public consultation on strategic planning, submissions made during congressional debate, as well as the large volume of consumer information requests and complaints directed to ANA, despite concerning the responsibilities of service providers and subnational regulatory agencies. ANA’s work is expected to support a highly ambitious national policy agenda to improve access to water supply and sanitation services, which, despite recent legislative efforts, remains some distance from national goals set for 2033 (see Chapter 2). The recognised need for urgent action creates significant pressure on all institutions involved in delivery. This creates additional pressure and expectations for ANA, as the agency responsible for establishing national reference standards for the regulation of WSS services. The precise role of ANA and the limitations the institution faces, due to the misalignment of its powers and mandate, as well as other external constraints, need to be well understood by ANA’s different stakeholders to ensure expectations are realistic. The reputational risk may subside as understanding of the recent reforms increases, but this understanding may require ANA’s intervention to develop and remain accurate.

ANA’s current strategic plan reflects the high level of policy ambition and may reinforce rather than mitigate the reputational risk linked to its new mandate. ANA’s strategic plan is ambitious in several ways: the volume of regulation and progress set-out to be delivered versus tight timelines; the scale of individual objectives and targets; and the assumed level of direct impact ANA’s actions may have on sector-wide outcomes. ANA’s current strategic plan sets-out 20 strategic objectives and multiple associated targets (see Box 1.1) which reach beyond ANA’s core responsibilities and relate more to final outcomes for the sector than to intermediate outcomes which ANA may directly influence through its own work and regulatory actions. Whilst some objectives and targets appear to reach beyond the responsibilities of the regulator, others require additional detail to be effectively interpreted and implemented as intended. For example, the use of phrases such as “number of contracts signed” or “number of initiatives proposed”, if not defined in relation to the expected outcome of those contracts or initiatives, may not result in the most effective actions being taken to achieve policy objectives. Overall, these factors create a risk that ANA’s role is misunderstood by stakeholders and expectations of ANA become intertwined with the success of the wider policy programme.

ANA has already begun to consider how it can operate within the existing regulatory framework and adapt to constraints. For example, ANA has identified and seized opportunities to partner and engage, and created an open environment for debate with stakeholders, including subnational entities, in both WRM and WSS – engagement on the development of the 2023 National Pact for Water Governance and co-operation agreements with the TCU are good examples of this consideration. With regards to the development of incentives, discussed above, ANA has begun to explore new ways to encourage compliance but must work swiftly to ensure these mitigation measures are in place. Building co-operation with prosecutors and the judiciary, as proxy enforcers of federal law, may help mitigate the impact of some constraints, following the experience of the European Commission (Box 1.2). This type of action is required due to the legislative framework, consisting the constitution and other primary legislation, which cannot easily be amended to address the balancing of powers, mandate and expectations, which is the source of this reputational risk.

Securing role clarity and managing expectations will continue to be a challenge given the complex and dynamic political and policy context and ANA’s extensive network of stakeholders. ANA is navigating a political context that is in flux, with Brazil’s recent elections having created uncertainty around the assignment of ministerial responsibilities. ANA’s full stakeholder map is complex and spans entities from small river basin communities to the National Congress. One consequence of this political and institutional landscape is the requirement for ANA, especially its leadership, to invest significant time and effort in stakeholder engagement. The recent election in Brazil provides further impetus for ANA to engage – ensuring newly elected and appointed decision-makers are aware of ANA’s regulatory roles, technical expertise, and availability to input into policy development.

Box 1.1. ANA’s strategic objective-setting and regulatory agenda

Following good practice, to develop the strategic plan, objectives and targets, ANA implemented a participative design process involving all ANA staff, its board of directors, as well as external stakeholders. The planning process for the 2023-26 strategy lasted approximately two months, starting with an organisational diagnostic, then moving through a series of validation meetings and workshops before the final strategy was drawn-up by Directors and Superintendents and signed-off of by the collegiate board.

ANA’s regulatory agenda for 2022-24 contains 43 items across 9 themes, of which 63% are on track and have been delivered, or are expected to be delivered, on time.1 In its separate strategic plan, ANA has defined 20 wide-reaching strategic objectives accompanied by 43 quantitative indicators, with annual targets defined for each indicator out to 2026 (full schedule available in Chapter 3).

Table 1.1. ANA’s strategic objectives

|

Output area |

Theme |

Strategic objective |

|---|---|---|

|

Results for society |

Critical event management |

1. Prevent and minimise the impacts of droughts and floods and promote the adaptation to climate change |

|

Dam safety |

2. Foster a dam safety culture through regulation, co-ordination, and articulation with other inspectors/enforcement institutions |

|

|

Water resources |

3. Ensure the availability of water in quantity and quality for their multiple uses with efficient and integrated management |

|

|

Basic sanitation |

4. Promote universal access to sanitation services |

|

|

Internal processes |

Information and communication |

5. Improve availability, quality and integration of data and information |

|

6. Strengthen ANA's institutional image by generating trust and credibility |

||

|

Innovation |

7. Improve user experience, facilitating and expanding access to services offered through a digital channel |

|

|

8. Make ANA’s day-to-day modus operandi more efficient |

||

|

9. Promote a regulatory environment favourable to development and innovation |

||

|

Integrated management |

10. Seek integrated and participatory management of water resources in priority areas |

|

|

11. Contribute to the financial sustainability of water infrastructure |

||

|

12. Strengthen SINGREH considering regional diversities |

||

|

Regulation |

13. Improve the regulation model with a view to the quality and safety of services |

|

|

14. Promote management and regulation of water resources, dam safety and regulatory harmonization for the sanitation sector |

||

|

Learning and growth |

Governance |

15. Improve the governance system, seeking effective benefits to society |

|

16. Foster a risk management culture with integrity, information security and data protection |

||

|

Corporate infrastructure |

17. Provide high-performance technological infrastructure and logistical support |

|

|

18. Efficiently execute action-oriented institutional resources and priorities |

||

|

People |

19. Promote continuous improvement in the organizational environment |

|

|

20. Implement strategic people management |

Whilst some objectives and indicators are defined at a more conservative level, with targets which relate directly to ANA’s mandate and scope of work, other objectives and indicators appear one or more steps removed from ANA’s control, and depend on other institutions, operators, or service providers to achieve. For example, progress on ANA’s strategic objective OE-7, “improve the experience of users, facilitating and expanding access to public services offered to society through a digital channel”, is indicated by the “number of services digitised in an integrated digital channel (mobile application ‘ANA Digital’)”, which is an area that ANA can internally control and influence. In contrast, progress on ANA’s strategic objective OE-4, “promote the universalisation of access to basic sanitation services by the Brazilian population”, is indicated by improvements in the attendance index of the total population with water network access, with a target increase of 4 percentage points by 2026 (i.e., securing coverage for an additional 9 million people).

1Please refer to ANA’s monitoring panel for its Regulatory Agenda 2022-2024, available at: Regulatory Agenda — National Water and Basic Sanitation Agency (ANA) (www.gov.br).

Source: ANA Strategic Plan 2023-2026 (ANA, 2023[5]); ANA Regulatory Agenda 2022-2024 (ANA, 2022[6]).

Recommendations

Identify and leverage alternative approaches and channels to increase ANA’s impact and encourage compliance with the national WSS reference standards set by the regulator, within the constraints of the existing institutional and legislative framework. This might involve:

more institutional co-operation and joined-up approaches with subnational entities that do have enforcement powers, such as the judiciary, or that can raise issues of non-compliance for deliberation, such as state prosecutors (Box 1.2). Given ANA’s inability, due to the legislative framework, to enforce the adoption of reference standards and compliance directly, it may need to work more closely with subnational entities to increase incentives for the universalisation of services to the benefit of Brazilian citizens. ANA’s reputation for effectiveness together with providing the evidence base can be leveraged in discussions with stakeholders to drive impact, such that ANA’s assistance and involvement may in itself present some incentive to stakeholders to engage on adoption;

a strengthened focus on capacity building and engagement with subnational regulatory agencies of WSS, including the development of inclusive fora for gathering and disseminating inputs, for example through expert panels. ANA would likely need to make a concerted effort to proactively engage with those regulatory agencies with relatively weaker capacity. As above, ANA’s reputation for effectiveness together with new supporting evidence can be leveraged in discussions with stakeholders to drive impact;

the development of new engagement methods, such as representative advisory boards, in addition to existing open call consultation processes, may provide a targeted method to invite input and guarantee relevant stakeholders (including harder to reach groups) input to the development of reference standards, and that, as legislation requires, local and regional conditions are considered. Different engagement methods may also help ANA by reducing burden, though public consultation is of course still a vital process and should not be removed – during the review process, ANA reported a high level of interest by stakeholders in reference standard development, but the key tool for gathering input, due to capacity constraints, remains the public consultation process, rather than supplementary stakeholder engagement channels. As is the case for all public institutions with such responsibilities, it will remain important for ANA to continuously assess whether engagement occurs at an appropriate frequency and remains purposeful, accessible, and inclusive; and

the use of sunshine regulation, benchmarking, or formal recognition of good performance by subnational regulatory agencies of WSS. This could include creating an ANA-approved regulatory network oriented around the promotion and implementation of reference standards, in combination with requirements or incentives (included in reference standards) for municipalities to work with subnational regulators that meet the necessary standards. ANA could also consider working with regional regulators to establish a taxonomy of effective regulation (with regard to regulatory outcomes) at a local level and collaboration and co-operation with the federal level. Such best practices could be effective to build capacity, set a clear direction, and increase pressure on entities resistant to change or who remain non-compliant.

each of the above points may be reflected in ANA’s strategic management outputs, as a part of high-level planning for how strategic objectives, focused on ANA’s engagement with national and subnational entities to deliver greater impact, can be achieved.

Manage expectations around the results that ANA can deliver and when, given the scope of agency’s role and powers, as well as its level of resources and capacity. This will serve to maintain stakeholder trust in the regulator, including the trust of the government in the regulator, trust in government more broadly, and boost understanding and mitigate reputational risks. ANA may identify and select a range of different management and mitigation strategies, but each will involve clearly communicating the scope of ANA’s role and limitation relating to powers, by:

assessing the feasibility of ANA’s regulatory agenda, strategic objectives, and related targets, and a review of what ambitions are being set and communicated externally. Objectives and targets should remain feasible and aligned with the organisation’s core functions and powers as an independent regulator to mitigate two areas of risk: first, stakeholder expectations not being met, and second, ANA going beyond its mandate in order to meet ill-defined or out-of-reach targets. There is an opportunity for ANA to refine outputs and strategic objectives within the regulator’s strategic plan to focus on outcomes closer to ANA’s sphere of influence, while still monitoring broader sector outcomes as “watchtower” indicators. This could help to communicate the regulator’s impact more clearly, and to put this in context with powers and responsibilities of other sector actors;

developing supporting communication channels and bespoke strategies to protect ANA from reputational risks, including those originating from mis- and dis-information, and enable ANA to effectively manage the expectations of its various stakeholder groups using public and plain language communication; and

engaging with external bodies involved in scrutinising and controlling ANA’s actions, including government (e.g., CGU) and independent (e.g., TCU) entities to ensure an alignment of understanding and expectations, especially during periods of public scrutiny and during the process of assessment. This extends to newly elected or appointed decision-makers in government and the regulated sector, who require, but may initially lack, a good understanding of ANA’s regulatory roles, technical expertise, or availability to aid policy development.

Box 1.2. Implementing the EU Urban Wastewater Treatment Directive

In 1991 the European Union adopted a Council Directive concerning “Urban Waste Water Treatment”. In the EU, treatment of urban wastewater is essential for ensuring enough good quality water for human and economic use and for nature and biodiversity. The Directive, which complemented any national legislation already adopted by EU Member States, set out EU-wide legal obligations to establish collection systems, apply treatment standards for discharges of urban wastewater from population agglomerations and to report on implementation. The Directive set out a differentiated 14-year implementation timetable, from 1991 to 2005, with a requirement for Member States to transpose the Directive into national legislation by 1993 and begin to apply the relevant treatment standards accordingly. Ensuring compliance is the responsibility of the Member States under this legislation.

Despite significant grant support from EU Cohesion and Regional funds for the necessary infrastructure investments (up to 85%), the Directive was far from fully implemented at the end of the 2005 implementation deadline. In 2018, 27 years after the adoption of the Directive, 15 years after the original deadline, the European Commission has estimated that compliance rates were above 90% for discharges to areas classified as sensitive in 9 out of the 12 States, with compliance rates of only between 44% and 84% for the remaining 3 States. For other areas, 8 out of the 12 States had compliance rates above 90%, while 4 States had compliance rates between 24% and 83%.

Non-compliance can be attributed to governance failures and/or lack of will to implement the Directive in the competent authorities of the Member States, which are in many cases regional or local. The fact that there was still a significant backlog almost 30 years after the adoption of the legislation illustrates the challenge of implementing standards when the co-ordination of a multi-layered and complex governance system is required.

In Europe, many environmental and public health issues such as treatment standards for urban wastewater and their application were considered subjects that were best dealt with by technical and scientific specialists and disputes in this respect were often dealt with and resolved by quasi-judicial technical bodies or agencies. Courts of justice were only rarely involved in resolution of such disputes. There was therefore not a tradition in the judiciary of the Member States for dealing with such issues.

With the adoption of a significant body of environmental EU legislation, the judiciary became an important player in implementation, including for the legislation on urban wastewater. The main enforcement instrument available to the European Commission is bringing cases to the European Court of Justice (ECJ) against Member States for failure to correctly implement the Directive. In such cases the ECJ rules about whether a member State is complying with its obligations. If a Member State despite a ruling from the ECJ continues not complying with its obligations, there is a possibility for the ECJ to inflict substantial financial penalties on that Member State. Some Member States, including founding EU Member States are still paying significant fines for implementation delays.

There is no doubt that the involvement of the judiciary and the numerous rulings by the ECJ have provided an important impetus and contributed significantly to implementation.

In recent years, the courts of the Member States have increasingly played a role in enforcement of EU environmental legislation and the European Commission has encouraged compliance proceedings to take place at the national level, provided that there are appropriate mechanisms in place, including judicial ones. In this context it is important that the ECJ has ruled that not only individuals negatively affected by bad application of EU legislation, but also environmental non-governmental organisations have legal standing and can bring such cases to national courts. In order to support effective implementation and enforcement in the Member States, the Commission supports the Member States’ IMPEL network (European Union Network for the Implementation and Enforcement of Environmental Law) of environmental regulators at national and subnational level and co-operates closely with European Union Forum of Judges for the Environment (EFJE) and the Academy of European Law (ERA) targeting specifically public prosecutors and the judiciary in the Member States with a view to strengthening the training and the role of the national judiciary in the enforcement of environmental law. Bringing disputes about implementation of EU environmental legislation has brought significant benefits in the form of faster resolution of disputes closer to the affected citizens. In such cases, courts have benefited from the possibility to request preliminary rulings from the ECJ, providing authoritative interpretations of EU legislative provisions in cases of doubt in the absence of jurisprudence.

Bringing implementation disputes to the national courts can bring significant benefits for enforcement by increasing overall judicial capacity to deal with disputes and ensuring faster resolution of disputes closer to the affected citizens with a better appreciation of local conditions.

Note: References to implementation in this paragraph refer to the 12 EU Member States who were EU members at the time of adoption of the Directive. Member States who joined later had different deadlines.

Source: Official Journal of the European Communities, No. L 135, pp. 140-152 (30.5.1991); European Commission, 11th Technical assessment on UWWTD implementation (2022) (https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/f9acae5a-ed21-11ec-a534-01aa75ed71a1 accessed on 1023-10-07); https://impel.eu; https://www.eufje.org/index.php?lang=en; https://www.era.int/environmental_law.

Building analytical capabilities in the economics of water and sanitation

Issue 2: ANA has developed a strong reputation and expertise in hydrology and other technical areas relating to water resource management, but, as the responsibilities of the institution transform, the skills the agency requires will have to transform as well. As the regulator takes on more responsibilities relating to economic regulation, it faces the challenge to build capabilities and capacity in the economics of water and sanitation. This capability will need to underpin ANA’s regulatory decision-making, as well as their advisory and capacity-building activity as the regulated sector tackles emerging challenges. At the same time, ANA’s access to a large amount of data could be further utilised to build analytical capacity and support regulatory quality.

Assessment

ANA is well recognised for the technical competence of its staff and for sharing its knowledge and expertise with sector actors. Specifically, ANA is known for its expertise and competency in areas such as hydrology, engineering, and water sciences. ANA offers formal training and qualifications in water-related disciplines for thousands of stakeholders within the sector and its own staff. A portion of its budget is earmarked for research and external training for water resource managers across the country, and short to medium-term, in-person and remote training initiatives have been completed by more than 260 000 people during the last 20 years. Furthermore, as part of its work to strengthen the national water resources management system, ANA helps design and sponsors formal education initiatives, such as the ProfCiamb and ProfÁgua post-graduate qualifications in Brazil. Its technical competence is one of ANA’s main assets that should be preserved and built upon.

ANA’s capacity and capability for economic analysis is relatively underdeveloped, reflecting the recent addition of many economic regulatory functions. Economists represent 4.6% of the workforce, whilst more than 30% of the workforce hold professional qualifications in civil engineering and the biological sciences. ANA established the Superintendency for Water and Economic Studies (SHE) in 2020, which could co-ordinate the insights from analytical and evaluation work to inform decision making, but its capacity is currently allocated to the construction of databases and the delivery of high-level studies, such as updates on Brazil’s progress relative to the Sustainable Development Goal and indicators relating to water and sanitation (SDG6) (ANA, 2019[7]). Furthermore, regulatory impact assessment tends to be qualitative rather than quantitative, although this is an area that the agency has identified for enhancement and is taking steps to improve. A range of economic analyses will be required to inform decision-making, from an ex-ante, shorter-term perspective (insights relating to what policy and regulation is achieving today and what is required to meet current needs), as well as a longer-term “stewardship” perspective (insights on what is being done to meet future needs and challenges) (Box 1.4).

ANA will need to rise to the task of creating an evidence base to support the implementation of new standards and reform. The insights provided by economic analysis or other relevant data analysis will be required to set realistic expectations and inform regulatory decision-making at the subnational level. Areas which could benefit from robust economic analysis include the financial implications of reference norms, water management and the universalisation and regionalisation initiatives. Stakeholders have voiced the need for evidence and tools to understand and assess the complex economic trade-offs inherent in sector regulation and financial management. Furthermore, evidence-based economic evaluation may help to convince certain stakeholders of the benefit of acting today for the benefit of future consumers and businesses, for example, in the case of water charging, by considering the consequences of inaction and issues of water quality and water security in terms of financial costs and lost revenue. A comprehensive evidence base, accessible and tailorable to all relevant stakeholders, which includes data on populations, costs, the asset base, service levels, risks and issues, and reporting on the maintenance and improvement of infrastructure, is currently lacking.

The demand for evidence and insights applies equally to ANA’s work in WRM and WSS, though in WSS there is more urgency. In WSS, subnational regulatory authorities will look to adopt reference standards in the coming years, whilst the regulated sector will be required to make changes to their business, including changes to financial planning, contracts, and investments. A clear understanding amongst policymakers, regulators, and regulated sector actors on the costs of meeting national reference standards will aid better decision making. In WRM, insights are required to bring awareness of emerging challenges, such as climate change, and the validity of considering these longer-term challenges into the decision-making process today, in addition to insights which can support shorter-term operational decision relating to, for example, the use of alternative water resources and the allocation of scarce water between competing uses.

Developing empirical economic analysis and a strong quantitative evidence base to deliver on new economic functions could bring additional benefits in terms of protecting against undue influence. A robust evidence base that is used to inform internal decision making will be useful for protecting against undue influence and misinformation targeting ANA, by helping to position the agency as apolitical and evidence-based. In the OECD’s work on the governance and independence of regulators, one of the factors identified to help prevent undue influence and maintain trust is for regulatory decisions to be founded on empirical evidence or research, post-implementation evaluation, and stakeholder input (OECD, 2014[8]).

ANA’s access to a large amount of data could be further utilised to build analytical capacity and support regulatory quality. Developing an evidence-base and conducting more sophisticated economic analyses requires good quality and timely data. For WRM, ANA is the custodian of a large amount of data: the regulator makes an important contribution to transparency by coordinating the national hydrometeorological monitoring network (RHN) and managing the National Water Resource Information System (SNIRH) and National Dam Safety Information System (SNISB). This data, whilst being publicly disseminated, may not be being fully exploited internally for the purposes of regulatory decision-making. Good data will be vital to support ANA’s stated ambition to develop the quantitative aspect of its regulatory management tools such as regulatory impact analyses and ex-post reviews.

However, the quantity and quality of data is not consistent across all areas of its mandate. In this regard, ANA faces particular challenges in water supply and sanitation since key data is owned by municipal and state-level entities and currently consolidated by central government ministries, for example data for WSS which is compiled by the Ministry of Cities responsible for the SNIS (Table 1.2). ANA is a data consumer in this sector, and thus may face delays in receiving requested data and cannot assure or control data quality – data at the municipal level in particular can be of very poor quality. With regard to ANA’s stated ambitions to develop impact analysis and reviews, the collection and use of data on fixed and variable costs, and an understanding of cost schedules and how they differ for different classes of asset, will be vital, in addition to finding ways to value other economic and social costs in the WRM and WSS environment.

Table 1.2. ANA's involvement in sector data flows

|

Water resources management |

Water supply and sanitation |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Data ownership and initial collection |

National Hydrometeorological Network (RHN) |

Municipalities / States |

|

Data consolidation and verification |

ANA (e.g., for delivery of SNIRH) (use of AI for verifications) |

Central government ministries (MCIDADES; MIDR) (e.g., for delivery of SNIS) |

|

Data use / analytics / reporting |

ANA (e.g., evaluation studies); Basin Committees; Water Resource Councils |

ANA |

|

Data process review |

ANA (e.g., systemised review of collection and data gaps) |

Central government ministries (process unknown) |

Source: OECD analysis based on ANA input.

Recommendations

Prioritise the hiring of staff at both junior and senior levels to increase ANA’s capacity and capabilities in line with the requirements of a professional economics function that supports ANA’s decision-making and advisory work across both WRM and WSS:

ANA might use the civil service hiring process approved in 2023, the first process to take place since 2008, to recruit new talent in this area. However, given the demand for staff across the organisation, this process will likely not be enough on its own. ANA requires not only entry-level staff, but also experienced senior experts who can consult decision-makers and bring in expertise on setting-up best practice processes and methodologies.

If current hiring constraints (see Issue 4 below) prevent ANA from taking immediate action, ANA may seek alternative routes to build capacity and capability. For example, by partnering with experts or institutions and designing appropriate channels to gather their input, leveraging the rotation opportunities within the civil service or other secondment or staff loaning options (considering regulatory agencies in Brazil or international programmes and arrangements with regulators outside of Brazil), training selected existing staff, or directing funds on a temporary basis to secure external support, but only if outsourcing can be designed in a way that supports the development of a sustainable economic capability for the agency.

Redefine the attributes of senior-level positions at ANA, including at the board level, to include economic expertise when relevant, and in a proportional manner.

Where additional hiring for capacity and capability may be limited, ANA may consider redefining the expected attributions of “free provision” positions, such as Superintendent or Board positions, at the next available opportunity, without interfering with the appointment and nomination process. A redefined set of attributions could include economic expertise as criteria and could be defined in relation to specific superintendent roles and for board members.

Direct ANA’s current and future analytical capacity toward developing the evidence base that supports stakeholders’ and ANA’s understanding of the economics and financial costs and benefits of national reference standard adoption in WSS, and engage to disseminate and promote the use of this new evidence base:

Alongside the definition and delivery of the national reference standards themselves, there is an urgent need for an objective evidence base, a “source of truth”, to aid decision making in the WSS sector – ANA may seek examples of analytical approaches and good practice from other regulators (Box 1.3) and develop a toolkit for subnational regulators.

To develop this evidence base, ANA can co-ordinate with Ministry of Cities to ensure data on sanitation is made available that meets ANA’s analytical requirements and the requirements of the sector, and advocate for any necessary changes to data collection methodology.

Once this evidence-base has been prioritised and developed, ANA should act to promote its use and stakeholder awareness, presenting an opportunity for ANA to clarify its role, and manage stakeholder expectations (see Issue 1).

ANA will need to also develop the internal processes, including data processes, to support the economic analysis indicated above and enable insights to feed into the Board’s decision-making, whilst continuing to engage with external stakeholders to develop processes or partnerships that enable ANA to access relevant information and provide feedback to data owners (Box 1.4; Box 1.5).

Box 1.3. WICS analysis on the future costs of drainage in Aberdeen

Aberdeen is a substantial city on the North East coast of Scotland. It is the third largest in Scotland and has a current population of around 230 000. It was the hub of the oil industry in the North Sea.

Being on the east coast, it has become used to much less rainfall than the western side of the country. Scottish Water worked with Aberdeen City Council to understand how future projected rainfall in the area could be managed. They used rainfall pattern ranges estimated by modelling of the impacts of global temperature increases.

The conclusion of the work between Scottish Water and Aberdeen City Council was that there were several initiatives that could allow for more effective management of the surface water that would result from the projected increase in rainfall. These initiatives would involve may parties and would require a considerable degree of collaboration and consensus building. They were consistent with pursuing a “Green/ Blue” strategy for the management of the water environment in the city.

The cost of these interventions was estimated to be between £400 million and £500 Million over the next 50 years. Scottish Water was clear that these collaborative approaches were likely to be much more cost effective than grey infrastructure solutions such as up sizing the sewer network and building increased storage. One of the key assumptions was that Scottish Water would maintain the capacity and effectiveness of its sewer system at no less than current levels throughout the transition period (the fifty years) and beyond.

WICS worked with Scottish Water to assess the economic impact of this necessary response to climate change. This involved understanding the replacement cost of the sewer network, its on-going maintenance and operational costs. This analysis was quite different to the aggregated assessment of current costs and the need for investment that would normally be the substance of a price setting exercise for a regulatory control period. This analysis was taking a specific bottom-up example for a discrete area and seeking to understand how much it may cost in future relative to the costs incurred at the current time.

WICS considered different asset lives for the sewer network and concluded that around 20% would likely have had to be substantially refurbished or replaced in the next fifty years. This suggested a transition cost requirement of 20% of the identified modern equivalent asset value of the sewer system serving Aberdeen. In addition, the £400-£500 million of new initiatives would have to be funded. The conclusion was that current expenditure on providing drainage services would have to increase by a factor of (at least) three. Drainage would become a larger component of costs than the collection and treatment of foul sewerage.

Separately, the Scottish Government had been considering splitting wate water charges into a waste and a drainage component. This analysis confirmed that it may be useful to establish clear charging arrangements for drainage in order that incentives could be created to limit flows of water from property drainage entering the sewerage system.

Source: Case study provided by WICS (Water Industry Commission for Scotland | WICS).

Box 1.4. Data collection methods to inform economic analysis – WICS example

WICS adopted the information framework that had been refined by Ofwat during the 1990s from an original set of templates used by HM Treasury for its scrutiny of the England and Wales water industry before privatisation. This annual information framework covers assets, costs, service and compliance levels, costs, and investment projections. The submission responds to detailed guidance issued with the templates by the regulator. The actual submission includes a detailed commentary explaining how the source of the information, assumptions that have been made and how it may be different to previous reports. There is a system of confidence grade that allow for the accuracy level and the quality of the information source to be made clear.

Following submission of the information, WICS engages in a query process (usually two rounds of queries are required to ensure a complete understanding has been developed) through which it works with Scottish Water to ensure that the information provided is as good and as consistent as it can be.

This information allows for the analysis of performance and for future price setting to be as robustly evidenced as possible. It allows any subsequent questions that may be raised by Government, customers or other stakeholders to be explained fully. This information framework is fundamental to the regulatory framework and helps to ensure that decisions are properly evidenced. It also helps safeguard the independence of the regulatory process.

Source: Case study provided by WICS (Water Industry Commission for Scotland | WICS).

Box 1.5. How New Zealand’s Commerce Commission gathers and disseminates information relating to the economic and financial performance of the regulated sector

New Zealand’s Commerce Commission is a multi-sector economic regulator. As well as price reviews, it has significant powers to require the public disclosure of information to reveal whether the objective of regulation is being met, “to promote the long-term benefit of consumers in [regulated] markets by promoting outcomes that are consistent with outcomes produced in competitive markets”. Sectors covered include electricity, gas, airports, telecommunications, fuel, and potentially in the future water.

The Commerce Commission publishes several visualisation tools based on the data collected. This includes the use of “dashboards” combining information from different regulated entities in the same sector to reveal comparisons, and a Performance Accessibility Tool (PAT). The Commission uses “Tableau” software to present the information and has developed internal capability in data handling and performance analysis.

The Performance Accessibility Tool for electricity distribution businesses, for example, allows anyone with an interest to compare performance between entities or focus on one particular entity. There are different metrics such as financial data, asset age and condition, system demand, network length, and network reliability. Financial data cover profits and ROI, regulatory asset base valuation, and itemised breakdowns of expenditure (capital and operating expenditure).

The Commission occasionally publishes analysis based on the information disclosed. The information in the PAT and the published reports helps third parties draw conclusions and engage with industry on questions of wider concern, including investment for decarbonisation and resilience to climate-related events.

Note: The PAT is accessible here: https://public.tableau.com/app/profile/commerce.commission/viz/Performanceaccessibilitytool-NewZealandelectricitydistributors-Dataandmetrics/Homepage. Additional examples of the types of analysis and reporting produced by the Commerce Commission are available here: https://comcom.govt.nz/regulated-industries/gas-pipelines/gas-pipelines-performance-and-data/trends-in-gas-pipeline-business-performance; https://comcom.govt.nz/regulated-industries/gas-pipelines/gas-pipelines-performance-and-data/performance-summaries-for-gas-distributors

Source: Information submitted by the Commerce Commission, 2024.

Designing an organisation that supports accountability and the efficient delivery of outcomes for citizens

Issue 3: ANA’s mandate spans three sub-sectors (water resource management, water supply and sanitation, and dam safety), each with distinct regulatory objectives and outcomes, sector and institutional contexts, stakeholders, and management challenges. However, neither ANA’s current organisational structure, nor its governance framework, operates along the same lines. A lack of clear accountability and whole-of-organisation approach to the delivery of results under each sub-sector potentially undermines the efficient management of resources.

Assessment

ANA’s mandate spans three discrete areas, each with distinct regulatory objectives and different needs in terms of processes and resources. ANA’s activities relate to three fundamental areas – water resources management (including water-use regulation), water supply and sanitation services, and dam safety. In each of these areas, ANA has distinct objectives and ways of working, faces different institutional and sector contexts, interacts with different stakeholders, and must manage different risks and resourcing challenges (Table 1.3).

Table 1.3. ANA’s core business areas

|

|

Water resource use regulation and water resource management |

Dam Safety |

Water supply and sanitation services regulation |

|---|---|---|---|

|

ANA’s function |

|

|

|

|

ANA’s main tasks |

|

|

|

|

ANA’s stakeholders |

|

|

|

|

Legislative framework1 |

|

|

|

|

Business line “ways of working” or “functional focus” |

|

|

|

1. Please refer to Chapter 2 – Sector Reform – for a full discussion of the legislative framework.

The current organisational structure and governance framework does not clearly map onto these three areas. ANA’s organisational structure was reorganised in 2022 into its current form, which includes 11 superintendencies, 5 special advisory bodies, 5 decision support units, and the internal governance committee, all reporting to a collegiate board (comprising five members, including the Director-President). In addition, an internal Ethics Commission was created, which may escalate issues outside of ANA to the higher Ethics Commission of the Presidency of Brazil. This reorganisation did not provide a fundamental restructuring of the agency around common inputs, process and goals, but rather the addition of units and layers of governance, and the reallocation of resources: the restructure was prompted by legislative requirements to introduce certain functions, such as the ombudsmen and a governance committee, as well as the need to consolidate advisory capabilities in governance and reallocate resources into new areas, such as basic sanitation. It is possible that this organic growth in the organisational structure means that ANA’s current structure does not facilitate an efficient, or the most effective, division of tasks and resources between superintendencies, or even within superintendencies.

The current organisational structure does not enable clear lines of accountability for the delivery of the three areas of its mandate between superintendencies and the Board. The collegiate board, as a collective, is technically accountable for all regulatory and administrative decisions, though the Director-President remains the legal representative of ANA. In practice, agenda items for board deliberation are almost fully developed at the level of the superintendency, accompanied by the supervising Board member (Director), the supervising Director’s cabinet, and relevant decision and management support units (such as SGE, ASGOV and ASREG), before reaching the board. The process of formulating a proposal, which is an important stage in developing the final decision due to the procedural nature of board deliberative meetings, therefore involves multiple parties, and may involve multiple superintendents. This process may improve transparency and the quality of final proposals but not necessarily accountability, specifically accountability for the decisions on regulatory developments which connect directly to ANA’s strategic objectives in each business area.

There is scope for ANA’s strategic plan and management reporting to better support lines of accountability and increase the focus around the three business areas. As already highlighted above (see Issue 1), ANA’s strategic planning process is an example of good practice in the way it promotes participation and its consideration of shared values and cross-cutting issues. The strategic plan and annual management plan are both sophisticated products that provide a comprehensive overview of ANA’s ambitions and transparency on ANA’s activities. However, the strategic plan as an output, in addition to being a tool to set and manage stakeholder expectations, is also a tool to help organise internal teams, provide focus in the regulator’s work and set common objectives and ways of working. ANA’s strategic and annual management plans could more clearly identify common objectives and co-ordinate areas of responsibility for the three areas of the regulator’s mandate, identifying accountability mechanisms at a higher level. There is also scope for more information to be provided on how ANA will work to achieve its stated objectives and targets, and for a view to be developed of how resources are currently allocated between the three business areas and how they are being utilised to achieve ANA’s primary objectives.

ANA’s roles and responsibilities in water resource management are far more developed and resource intensive today than those in dam safety or water supply and sanitation, and this will likely remain the case in the future. ANA’s roles and responsibilities across the three business areas are not equal in terms of the resources required to fulfil the regulators core functions and ANA’s structure does not need to aim for an equal distribution of resources between business areas. However, there is room to develop the current organisational structure and governance framework in order to promote accountability and the efficient use of resources.

Recommendations

Develop a view of how resources are currently being allocated and used across ANA’s three business areas at an aggregate level to deliver regulatory objectives and use this process as an opportunity to identify any issues and opportunities, for example relating to under-resourcing or opportunities for joined-up working. This process would not pre-determine an allocation of resources between business areas, it is a process meant to explore synergies and opportunities to improve ANA’s delivery of its functions from the perspective of efficiency, whilst maintaining clear governance and accountability.

Assess the feasibility of adjusting ANA’s organisational structure or governance framework to better align with its three core business areas – water resource management (including water resource use regulation), dam safety, and water supply and sanitation services – to enable clearer lines of accountability. ANA will need to assess how such an adjustment can be delivered whilst respecting the constraints on organisational design and resourcing provided by legislation, as well as civil service norms.

Consider a divisional or new hierarchical structure based on the three business areas to enable the drawing of clearer lines of accountability and oversight, by identifying lines of responsibility for expected outputs and outcomes in each of the three areas. A divisional structure can help provide clarity, strengthen interlinkages between superintendencies working in the same area, pool capacity and capabilities, and may free-up capacity at senior and junior levels to allow the development of required talent, for example in economic analysis (see Issue 2).

Consider the articulation of a governance framework based on matrix management principles, as an alternative, or complementary action, to formal restructuring, which would enable the co-ordination and integration of the various activities and resources and allow for a simplification of the accountability structure based on the three business areas. ANA would need to assess how this might be operationalised within ANA’s existing structure and governance arrangements, considering any mandatory requirements and limitations.

Explore possibilities to delegate certain decision-making powers to the responsible superintendency, to create clearer lines of accountability and enable the Board to focus on strategic decisions and oversight and performance monitoring.

Put in place an ongoing review process to confirm whether the organisational structure remains fit for purpose and address the following concerns:

overlaps in specialisation and function are avoided;

siloed working on similar topics is not apparent within or across superintendencies; and

the structure enables the efficient development of capacity and capabilities which can be directed toward ANA’s distinct business areas.

Structure future strategic and management outputs, including the strategic and annual management plans, around the three business areas:

Utilise the strategic plan and annual management reporting to (for each business area) identify common objectives, allocate areas of responsibility, and re-state lines of accountability, whilst motivating staff by clearly identifying how ANA will achieve its stated objectives and address identified risks and issues within each business area.

Incorporate a view of the allocation of resources (human capacity and capability or financial resources), by business area, into the management outputs to provide transparency on how resources are being used to achieve ANA’s main objectives, and clarify the opportunities and needs for adjustment, including any issues related to the external governance of human and financial resources.

Operating within financial and human resource constraints

Issue 4: ANA faces constraints relating to its human and financial resources and the ways in which these resources can be used and managed. These constraints create some concerns around the delivery of ANA’s new duties under the 2020 Sanitation Law, the regulator’s ability to react to new and emerging challenges and ensure an efficient use of resources in those areas where it can achieve the highest impact, as well as its ability to act independently in the future.

Assessment

Brazil’s legislative framework and current external governance processes create constraints and challenges around resource management which ANA must navigate. Specifically, due to current fiscal management processes and legislative arrangements on the collection and use of revenues which impact ANA as a federal regulator, ANA faces significant revenue uncertainty and budgetary control. Additionally, ANA does not have full control over its hiring practices: ANA must seek approval from government to hire permanent civil servants, lacks the ability to directly assess candidates during the hiring process, and lacks the tools to manage performance following civil servant appointments.

Financial resources and management

ANA’s new mandate in WSS has not been accompanied by sustainable arrangements which satisfactorily guarantee the revenues to enable ANA to deliver on its mandate in the long-term. The funding of ANA’s new duties in WSS, under which the development of reference standards and monitoring of their adoption is mandatory, must ordinarily be taken from ANA’s national budget allocation. ANA has successfully negotiated a budget adjustment with Congress to increase the amount of its discretionary funding, amounting to 0.75% of the value of the charges levied on hydroelectric power generation, to supplement the national budget allocation (see Chapter 3). This arrangement is temporary and requires approval on an annual basis, resulting in resource uncertainty. Whilst this temporary arrangement currently facilitates ANA’s role in WSS, it does not represent an adequate solution for ANA’s role in WSS, which represents a long-term endeavour. It is unclear how ANA can deal with future increases in workload, for example when reference standards are in place and ANA must commence monitoring and capacity-building initiatives. The agency has already noted the importance of outsourced consultant resource and the development of training initiatives for supporting reference standard adoption by subnational agencies. A change in legislation would be required to guarantee the availability of revenues from current “earmarked” sources over the longer-term (i.e., open-up earmarked resourced for new uses) or to design appropriate new earmarked funding arrangements for WSS, both of which would provide greater financial stability for ANA and reduce risk of non-delivery.

A long-term budgetary solution which enables ANA to fulfill its duties in WSS becomes more important when considering ANA’s limited pool of discretionary resources. Revenues from industry fees associated with hydropower production and water charging are earmarked under primary legislation, with revenues flowing through ANA into specific projects, such as the implementation of the PNRH and management of the RHN or, in the case of revenues for water charging, flow directly to river basin committees. Assessing actual revenues from 2020 to 2022, on average, fees from hydropower production represented 57% of ANA’s annual revenue, a further 7% was contributed from the federal budget, and the remaining 36% came from water charges levied at the basin level (see Chapter 3 - Governance). Ignoring those revenues from water charging which flow directly back to basins, of the remaining revenue which ANA is responsible for allocating (federal budget plus fees levied on hydropower operators), approximately 11% of ANA’s revenues are truly discretionary, but 89% are earmarked. Earmarking arrangements provide stability and follow best practice, however, in combination with a comparatively low discretionary budget, the regulator’s autonomy, and ability to adapt to changing circumstances is reduced. Combined with a limited unearmarked budget, this may undermine the implementation of the regulator’s work in the WSS sector. ANA, as other government departments and federal agencies, also faces pressure to cut administrative spending and the threat of a reduction to its federal budget allocation, though this has so far not materialised.

Finally, although funding levels are currently sufficient to enable ANA to fulfil its duties, there are risks that ANA may face revenue uncertainty during the financial year. Federal government processes of fiscal consolidation and rebalancing throughout the year may result in changes to the expected levels of income as approved in the budget. Additional uncertainty in the annual discretionary budget is created by the threat of fiscal constraints, which are assessed and may be applied at the start of the financial year by government.

Human resources and management

Regarding human resources, ANA faces several constraints which carry different risks, starting with an overarching constraint on its ability to hire new permanent civil servants. ANA wishes to hire more permanent civil servants to join its career paths and carry out specific administrative and specialist roles. The level of permanent civil servants at ANA is currently below the legislated cap, however, new permanent positions, and the civil service examinations required to recruit for these positions, must be approved by the Ministry of Management and Innovation in Public Services. This Ministry has recently approved hiring for 40 of the 110 available positions at ANA, the first approval of its kind since 2008, however, this remains below the requested volume. One of the consequences of this constraint on ANA’s hiring is a lack of permanent civil servants in specific roles and a growing reliance on temporary civil servants or outsourced staff, which is significant since some regulatory duties can only be completed by permanent civil servants. In some areas, such as IT, ANA is also facing a general challenge to compete with the market, if it is unable to offer job stability – the distinctive benefit of a role at ANA, versus private sector companies who tend to offer higher salaries but less job security.

Additionally, ANA’s autonomy in civil servant selection and performance management is limited, which impacts organisational efficiency and effectiveness. Once approval for civil servant hiring has been granted, ANA defines the desired candidate profiles and basic requirements, such as educational background, technical qualifications and experience, for which candidates may gain credit, but ANA is not directly involved in the assessment of candidates. This process is consistent across Brazil’s civil service and is the case for all other federal regulatory agencies. Furthermore, candidates are not subject to any competency-based assessment or in-person interview, which, although aimed at removing a bias in the quantitative scoring, prevents ANA from assessing whether candidates will be a suitable fit within ANA’s workforce given the specific nature of its work as a regulator. Once civil servants are confirmed, a rigid performance management process applies, defined under legislation, which covers only an assessment of the minimum requirements for civil servants to progress in salary and title. It is effectively impossible for ANA to dismiss permanent civil servants, except in cases of misconduct.

Both the hiring of new civil servants and outsourcing of work, whichever resourcing option is taken, present human resource management challenges for ANA. Newly qualified civil servants enter ANA at junior staff levels, at which point there is a significant effort required of ANA to onboard and develop civil servants. It is also necessary for ANA to invest to develop staff competencies, for example trainings in management for staff stepping-up from technical to managerial roles, rather than hiring expertise and competence externally at the appropriate level. A separate consequence of an increase in temporary or outsourced staff within ANA’s workforce, as an alternative to permanent civil servant hiring, is that a greater number of staff are not subject to the formal arrangements for performance assessment and career progression, training, or other administrative arrangements that apply only to permanent civil servants, nor do these staff receive the same level of remuneration and benefits. In 2023, ANA’s workforce totals 559 people, including 373 civil servants, the majority (76%) of which are permanent civil servants, and 186 outsourced staff – approximately one third of ANA’s total workforce. This is broadly in line with the average for other water regulators internationally (Box 1.6) Over the longer-term, a growing reliance on temporary and outsourced staff combined with staff turnover, such that it alters the make-up of ANA’s workforce, may impact institutional knowledge as well as ANA’s working culture and the morale and dedication of its staff.

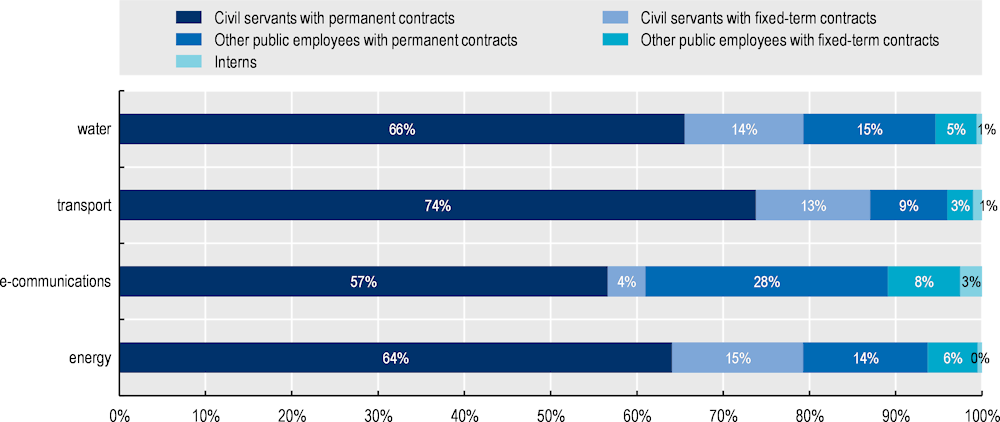

Box 1.6. Comparing economic regulators’ workforce arrangements

In 2022, as part of a report on Equipping Agile and Autonomous Regulators (OECD, 2022[9]), the OECD published the results of a survey investigating how economic regulators receive and manage their human resources. The underlying “Survey on the Resourcing Arrangements of Economic Regulators” was conducted in 2021 and involved 57 economic regulators across 31 countries.