This country note provides an overview of the labour market situation in Spain drawing on data from OECD Employment Outlook 2024. It also looks at how the transition to net-zero emissions by 2050 will affect the labour market and workers’ jobs.

OECD Employment Outlook 2024 - Country Notes: Spain

Labour markets have been resilient and remain tight

Labour markets continued to perform strongly, with many countries seeing historically high levels of employment and low levels of unemployment. By May 2024, the OECD unemployment rate was at 4.9%. In most countries, employment rates improved more for women than for men, compared to pre‑pandemic levels. Labour market tightness keeps easing but remains generally elevated.

The Spanish labour market continued to show strong dynamism over the last year, but unemployment remains high relative to the OECD average. The employment rate has reached record levels in over a decade, with 65.7% of working-age adults in employment in the first quarter of 2024. Similarly, labour force participation continued to rise last year, reaching 74.6% in the same period, 1 percentage point above pre‑COVID levels. Although unemployment has reached a record low since the Global Financial Crisis, Spain’s unemployment rate remains the highest across all OECD economies, standing at 11.7% in May, almost 7 percentage points higher than the average (Figure 1).

Spain’s GDP is projected to continue expanding, but at a slower rate compared to previous years. GDP growth is expected to moderate to 1.8% in 2024 and 2% in 2025, following robust growth rates in 2023 and 2022. The unemployment rate is projected to continue declining, but at a slower pace than in previous years, as lower economic growth is likely to moderate job creation: current projections indicate that it could reach 11.5% by the end of the year and 11.1% in the last quarter of 2025.

Since March 2023, new demographic groups have been designated as priority targets for employment policy. The 2023 employment law requires the adoption of employment programmes targeting specifically these groups, including people from the LGTBI community, people affected by drug dependence and other addictions, and people from ethnic and religious minorities, among others. Further evaluation is needed to assess the effectiveness of this legislative change in fostering employment for these groups.

Figure 1. Unemployment rates remain at historically low levels in many countries

Unemployment rate (percentage of labour force), seasonally adjusted data

Note: The latest data refer to March 2024 for the United Kingdom, and June 2024 for Canada and the United States.

Source: OECD Employment Outlook 2024, Chapter 1.

Real wages are now growing but there is still ground to be recovered

Real wages are now growing year-on-year in most OECD countries, in the context of declining inflation. They are, however, still below their 2019 level in many countries. As real wages are recovering some of the lost ground, profits are beginning to buffer some of the increase in labour costs. In many countries, there is room for profits to absorb further wage increases, especially as there are no signs of a price‑wage spiral.

Despite the positive trends in labour market indicators, Spain is among the OECD countries where real wages have declined the most since the beginning of the pandemic. Although nominal wages have risen above inflation in 2023 and early 2024, real wages were still 2.5% lower in Q1 2024 relative to Q4 2019. In contrast, nearly half of OECD countries, including neighbouring Portugal and France, have successfully regained pre‑crisis real wage levels or surpassed them. Spain faces higher year-on-year inflation compared to the Eurozone area – 3.8% and 2.6%, respectively, as of May –, which poses a persistent challenge to real wage growth.

Statutory minimum wages in real terms are above their 2019 level in virtually all countries

In May 2024, the real minimum wage was 12.8% higher than in May 2019 on average across the 30 OECD countries that have a national statutory minimum wage. The average figure is driven in part by strong increases in some countries (Mexico and Türkiye), but the median increase was also quite significant, at 8.3%.

Contrary to other wages, the minimum wage in Spain has risen above inflation. Spain has carried out annual statutory minimum wage increases, leading to a cumulative 26% rise in the nominal level since 2019. This translates into a 6.5% real increase, slightly below the OECD median. The increase in the minimum wage has not posed a significant challenge to employment growth, which has been robust throughout the period.

The Spanish Government determines the statutory minimum wage annually through consultations with major trade unions and employers’ associations, though these consultations are non-binding. The Spanish coalition government had as an objective to raise the minimum wage until reaching 60% of the median wage, a milestone achieved in 2023. Hence, future increases in the minimum wage will likely be more moderate.

Climate change mitigation will lead to substantial job reallocation

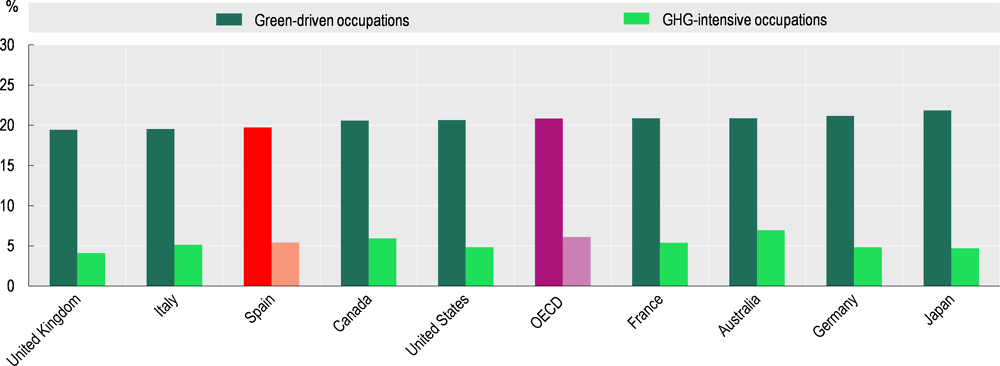

The ambitious net-zero transitions currently undergoing in OECD countries are expected to have only a modest effect on aggregate employment. However, some jobs will disappear, new opportunities will emerge, and many existing jobs will be transformed. Across the OECD, 20% of the workforce is employed in green-driven occupations, including jobs that do not directly contribute to emission reductions but are likely to be in demand because they support green activities. Conversely, about 7% is in greenhouse gas (GHG)-intensive occupations.

Almost one‑in-five Spanish workers is employed in green-driven occupations, in line with the OECD average (Figure 2). However, only 11.5% of workers in this group are actually employed in “new and emerging green occupations”, significantly below the OECD average (14.5%), whereas the rest are employed in jobs that are not new but that are linked to the green transition. Conversely, only 5.4% of the workforce is employed in GHG-intensive occupations, slightly below the OECD average.

In Spain, men are more likely to be employed in green-driven occupations (around 25% versus 12.5%), but the gender gap is among the smallest across the OECD. Workers that have not completed upper secondary education are also more likely to be employed in GHG-intensive occupations.

The highest share of green-driven occupations can be found in Aragón, while the highest share of GHG-intensive occupations can be found in Galicia.

In terms of job quality, low-skill green-driven jobs in Spain tend to have significantly lower wages and labour market security than other low-skill jobs. This suggests that, in the absence of policy measures, low-skill green-driven occupations may be a relatively unattractive option for low-skill workers.

Many high-skilled emission-intensive and green-driven jobs are very similar in their skill requirements, meaning that high-skilled workers can move from emission-intensive to climate‑friendly industries with relatively little retraining. However, this is not the case for low-skilled workers, who will require more retraining to move out of emission-intensive occupations.

Spain has been particularly active in promoting training for the green transition. The country provides funding for new training and apprenticeship programmes related to the green transition and is one of few OECD reporting to have career guidance initiatives to facilitate transition into green jobs.

The projected changes associated with the net-zero transitions should be contrasted with the employment costs of inaction on addressing climate changes.

Indeed, 25% of workers in Spain suffer from significant heat discomfort, typically workers in outdoor occupations and workers in process and heavy industries, with potential negative effects on their health and productivity. This share is much larger than that across OECD countries, which stands at 13%.

Figure 2. One out of five workers is employed in green-driven occupations

Percentages, average 2015‑19

Source: OECD Employment Outlook 2024, Chapter 2.

Job loss in high emission sectors carries larger costs than in other sectors

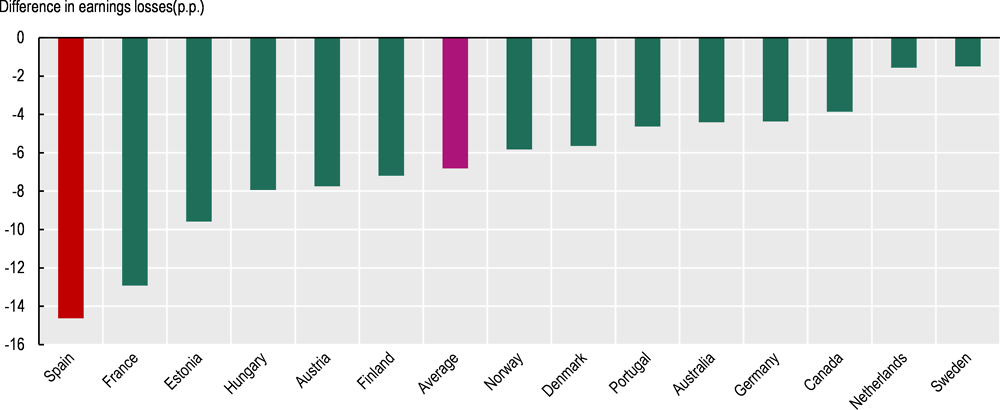

The net-zero transition induces a contraction of high emission sectors, which account for 80% of GHG emissions but only 7% of employment across the OECD. Workers in these sectors face greater earnings losses after job displacement, averaging a 36% decrease over six years after job loss compared to 29% in other sectors. Policies that support incomes and facilitate job transitions are essential to mitigate these losses and ensure support for the net-zero transition.

In Spain, the differences in earnings losses over six years after job displacement between workers in high and low emission sectors are the largest among OECD countries for which data is available, standing close to 14 percentage points on average (Figure 3). This significant disparity is explained by strong differences in the composition of workers and firms between high emission and other sectors. In Spain, displaced workers in high emission sectors are considerably older and have more tenure. Meanwhile, firms in high emission sectors offer higher wage premia and are more often found in industries where earning losses tend to be particularly high, such as emission-intensive industrial sectors.

Figure 3. Workers in high emission sectors face larger job displacement costs than in other sectors

Brief description: The figure shows the difference in average earnings losses for workers displaced in high and low emission sectors over six years after job loss across 14 OECD countries.

Source: OECD Employment Outlook 2024, Chapter 3.

Contact

Stefano SCARPETTA (✉ stefano.scarpetta@oecd.org)

Javier TERRERO (✉ javier.terrero@oecd.org)

This work is published under the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of the Member countries of the OECD.

This document, as well as any data and map included herein, are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area.