Services encompass a wide array of economic activities, including information and communication services, financial services, transportation and logistics services, and professional services. Oversight of these sectors is distributed among various government bodies and professional organisations, each empowered with regulatory authority to oversee licensing, competition, and overall professional conduct in these fields. The complexity and diversity within and across services pose challenges for trade policy makers and negotiators. They must engage with domestic regulatory bodies and balance the interests of businesses and consumers. Domestic regulations on services often precede international trade agreements, resulting in significant disparities between countries even when aiming for similar objectives. This section presents the latest trends and evidence on services trade policies drawing on the OECD STRI database and indices.

Revitalising Services Trade for Global Growth

2. Global regulatory developments on services trade between 2014 and 2023

2.1. Services trade barriers are high and asymmetric

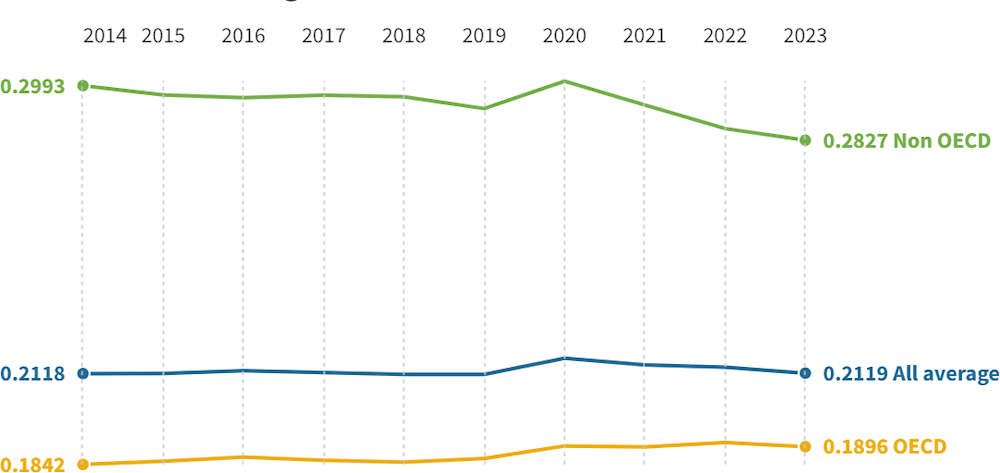

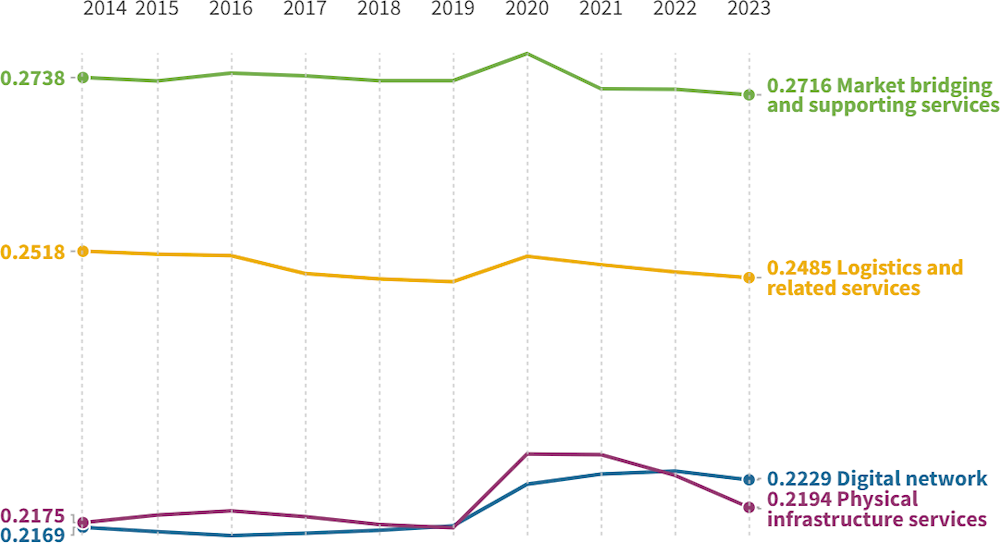

The STRI shows that global services trade restrictions remained high on a global scale over the past decade with no significant change in the average level of restrictions over time (Figure 1.2). While OECD countries have a more open regulatory environment to services trade than non-OECD countries, the average STRIs have moderately increased over time. In the case of non-OECD countries, despite the relatively high overall levels of restrictiveness, the post-pandemic years saw an acceleration of more trade liberalisation policies. Indeed, in 2014, the average level of restrictiveness in non-OECD countries was 1.4 times (or 40%) higher than in OECD countries. By 2023, this shrunk to less than 1.3 times (or 33%).

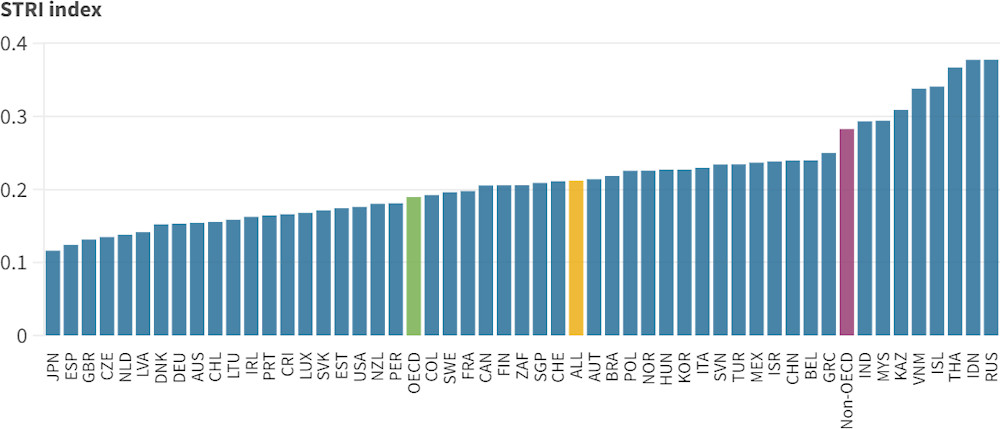

Figure 2.2 presents the average STRIs across all countries covered. It shows that in 2023, there is a broad diversity on the level of restrictiveness across countries, with 22 countries above and 28 below the sample average. Japan, Spain, and the United Kingdom are the countries with the lowest average STRI, indicating the most open regulatory framework. The Russian Federation, Indonesia, and Thailand have, on average, the highest STRI scores.

Figure 2.1. Regulatory developments in services trade restrictions since 2014

Levels of STRI averages, 2014 to 2023

Note: Average across all sectors covered by the STRI. "All average" covers the 38 OECD countries, and the non-OECD countries covered by the STRI: Brazil, the People’s Republic of China, India, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, Peru, Russian Federation, Singapore, South Africa, Thailand, and Viet Nam. Access the interactive version of the graph: https://public.flourish.studio/visualisation/17788501/.

Source: OECD STRI database (2024)

Figure 2.2. Services trade policies across countries, 2023

Note: The STRI indices take values between zero and one, one being the most restrictive. The STRI database records measures on a Most Favoured Nation basis. Air transport and road freight cover only commercial establishment (with accompanying movement of people). The indices are based on laws and regulations in force on 31 October 2023. The STRI regulatory database covers the 38 OECD countries, Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, Peru, Russian Federation, Singapore, South Africa, Thailand, and Viet Nam. The “ALL” average reflect the average based on the STRI country sample. The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law. Access the interactive version of the graph: https://public.flourish.studio/visualisation/18225821/.

Source: OECD STRI database (2024).

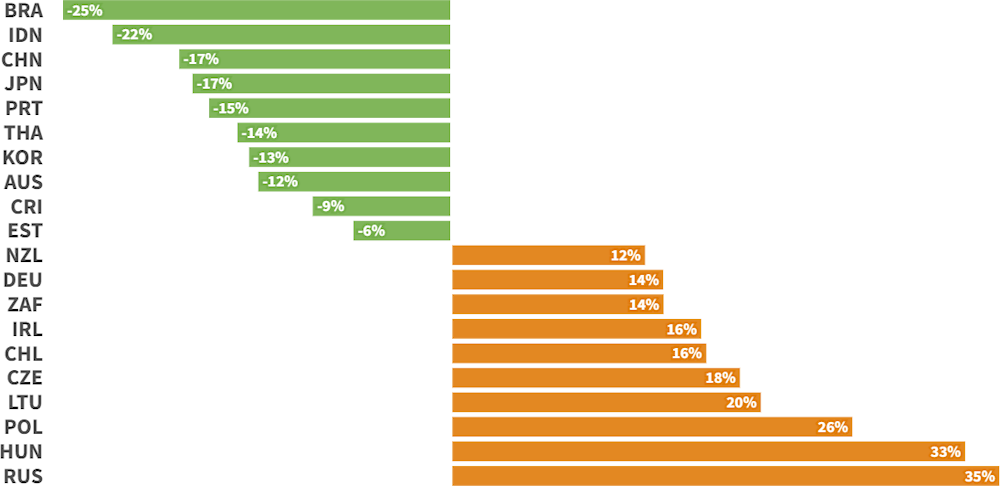

Several countries undertook significant efforts to liberalise their policies over the period 2014-2023 (Figure 2.3). Brazil, for instance, saw its average STRI for all sectors drop by 25%, Indonesia by 22%, and the People’s Republic of China (hereafter China) by 17% (Box 2.1). Other countries undertaking significant reforms include Japan, Portugal, Thailand, Korea, Australia, Costa Rica, and Estonia.

Countries where STRIs have increased the most include the Russian Federation, some European countries, South Africa, Chile, and New Zealand.

Several countries have shown a fluctuating policy environment. Viet Nam, for example, had been on a path towards progressive liberalisation between 2014 and 2018, but introduced some restrictive measures between 2019 and 2021, in part due to the COVID-19 pandemic. While most of these measures were subsequently lifted in 2022, new economy-wide policies relating to data flow contributed to another increase in the level of restrictiveness by 2023. Other countries with fluctuating average indices are China and Türkiye.

Figure 2.3. Top 10 countries with most changes in the STRI scores

In percentage, between 2014 and 2023

Note: Decrease in the STRI averages are due to liberalising policies, while increases are due to the introduction of more trade restrictive policies. Access the interactive version of the graph: https://public.flourish.studio/visualisation/18239951/.

Source: OECD STRI database (2024).

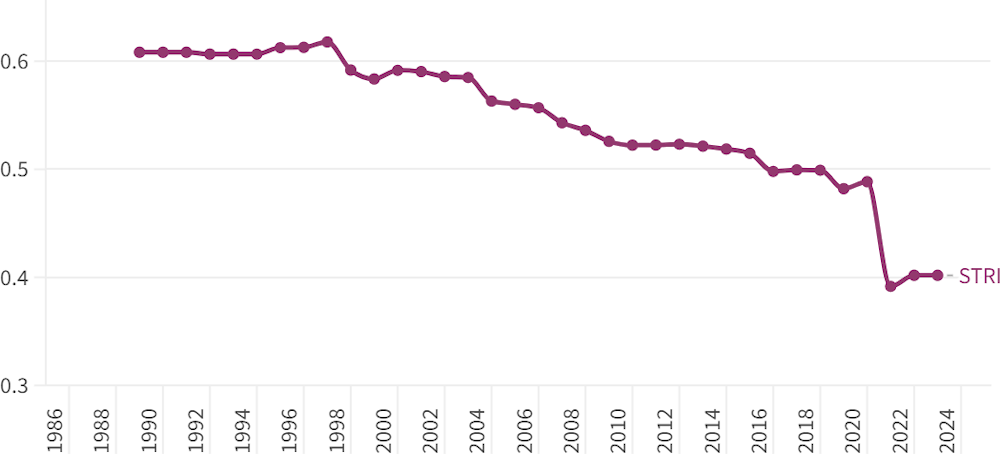

Box 2.1. Services trade reforms in Indonesia since 1989: Progress over the past 35 years

The regulatory environment in Indonesia has changed significantly since 1989. Annual information in the STRI database helps identify the relevant regulatory changes for services trade across all sectors covered and to better understand Indonesia’s long term regulatory developments.

As shown in Figure 2.4, Indonesia has undertaken significant reforms over the past decades, gradually opening up to international services trade and improving its domestic regulatory environment. Compared to the 1989 benchmark, Indonesia’s average STRI had dropped by around 35% by 2023.

While the pace of reform was uneven between 1989 and 2023, it has since accelerated substantially, particularly since 2021 when a new investment regime came into force. Foreign investment in Indonesia is regulated under Law No. 25 of 2007, which mandates the government to define the sectors open to foreign investment and under what conditions. In March 2021, Presidential Regulation No. 10 of 2021 (as updated by Presidential Decree 49/2021) was enacted, replacing Presidential Regulation No. 44 of 2016. A key reform was to liberalise all sectors to foreign investment with the exception of those listed in the instrument as closed or restricted to foreign investment; the current list is composed of 69 business sectors closed to foreign investment and 26 business sectors as partially restricted. Under the previous Presidential Regulation 44/2016, there were over 160 sectors closed to foreign investment and over 200 sectors partially restricted.

Figure 2.4. Services trade liberalisation in Indonesia between 1989 and 2023

STRI weighted sector averages, 1989-2023

Note: Averages based on 22 services sectors covered in the STRI. Weights based on the OECD TiVA. The STRI takes value between 0 and 1, where 1 indicates the most restrictive regulatory environment for services trade. Lower averages indicate a more open regulatory environment. Access the interactive version of the graph: https://public.flourish.studio/visualisation/18235553/.

Source: OECD (2024[8]).

While the scope of liberalisation is substantial, in some cases such as air transport services the new PR 10/2021 introduced more stringent conditions, such as lowering foreign equity limits to 49% after they had been raised to 67% in PR 44/2016.

PR 10/2021 is one of the implementing measures introduced as a result of Law No. 11 of 2020 on Job Creation (as amended by Law No. 6 of 2023), also called the Omnibus Law, and which introduced a broad mandate for the government to ease foreign investment restrictions and to foster job creation for Indonesians.

Continued efforts to liberalise services trade, including digital trade, is essential for Indonesia to leverage the gains from open and more competitive services industries, especially as this concerns smaller firms.

Source: OECD (2024[8]).

2.1.1. Regulatory divergence grew in digital network services, but dropped in other sectors

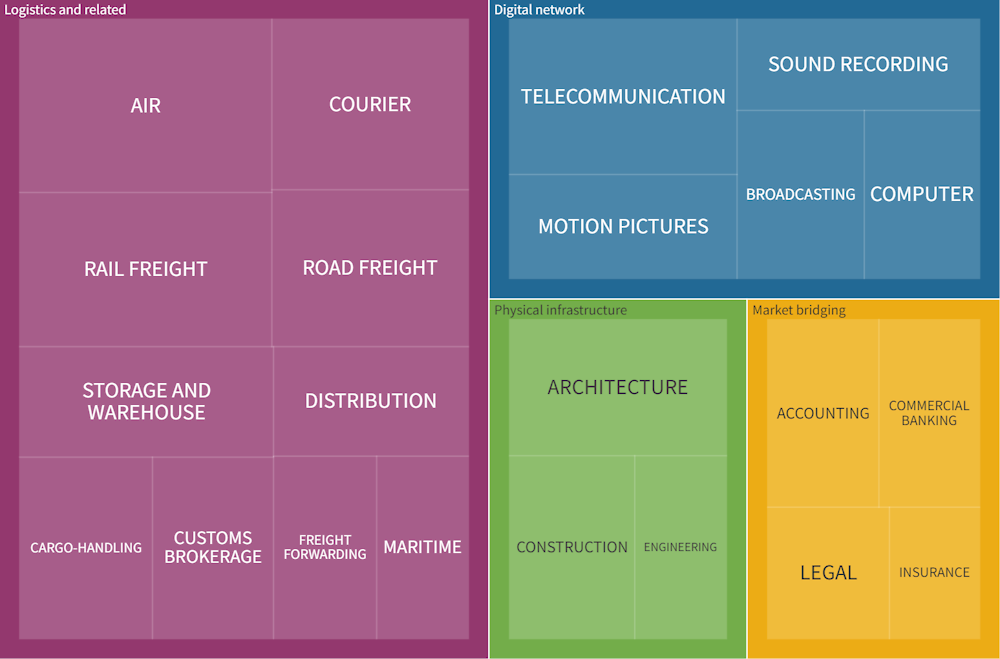

The OECD STRI covers 22 services sectors which can be broadly organised under four main clusters based on similarities in the functions that these services fulfil in the economy (Box 2.2). While not aligned with industry classification schemes, such clustering has the benefit of providing insights into the breadth and variety of sector-specific trade policy measures and shows that trade restrictive policy measures in one sector may have an impact on other sectors along services value chains.

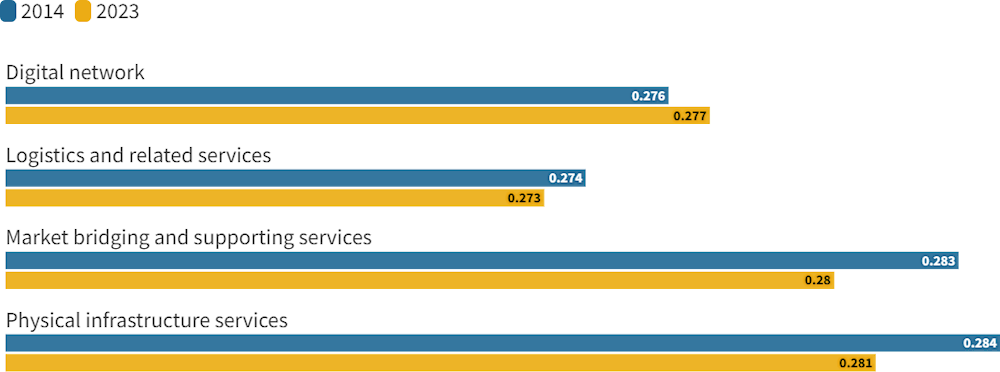

Regulatory disparities across countries can present barriers, impeding the fluidity of international trade in services. They breed uncertainty and stifle the growth potential of businesses eager to expand beyond their borders. Heterogenous regulatory frameworks increase compliance costs and administrative burdens, deterring companies from venturing into new markets. Over the past decade, regulatory differences affecting digital trade and related sectors have increased across countries (Figure 2.5).

In other sectors, market bridging services have seen greater convergence across countries largely due to the implementation of international financial and prudential standards. Construction services, engineering and architecture, which form the physical infrastructure cluster have also seen more convergence over the past years. In logistics and related sectors, there has been moderate convergence in aviation and maritime transport, but slower progress in other transport and logistics sectors.

Box 2.2. Services clusters in the STRI

1. Digital network services (telecommunications, computer services, broadcasting, motion pictures and sound recording): Telecommunications and broadcasting provide the networks over which content is delivered, and computer and information services offer a host of services including information storage and processing, network management systems and over-the-top services complementing telecommunications and broadcasting services. Content and content-related services are also increasingly digitized and delivered on digital networks.

2. Logistics and related services (logistics, transport, courier, and distribution services): Transport and logistics services are key inputs at the heart of global value chains. Distribution, postal and courier services are essential for bringing goods from the producer to the consumer and handle an ever-growing demand for parcel deliveries.

3. Market bridging and support services cluster (commercial banking, insurance, legal, and accounting services): Economic activity in general and international transactions in particular rely heavily on access to credit, payment systems and insurance. Legal services are supporting business operations and the enforcement of contracts is one of the most important pillars of a market economy. Trustworthy, transparent and easy to understand accounting information is needed in order to assess the credit worthiness of strangers. With the growing complexity of international business, these services are essential for entrepreneurs to develop and commercialise their ideas, for the functioning of value chains, and for investors to contribute to growth and innovation.

4. Physical infrastructure services cluster (construction, architecture and engineering): Construction services have historically been considered strategic for providing the infrastructure for other industries. Architects undertake the design of buildings whereas engineers participate in the construction of key infrastructure such as buildings, roads and bridges. Often engineering and architectural activities are combined in projects offered by one company and are sometimes subsumed in the construction sector.

Source: OECD (2017[9]).

Figure 2.5. Regulatory divergence grew in digital network services, but dropped in other sectors

Average STRI heterogeneity indices in 2014 and 2023

Note: The sectors covered in the STRI can be broadly organised around four clusters: 1. Digital network services (telecommunications, computer services, broadcasting, motion pictures and sound recording); 2. Logistics and related services (transport, courier, logistics and distribution services); 3. Market bridging and support services cluster (commercial banking, insurance, accounting and legal services); and 4. Physical infrastructure services cluster (construction, architecture and engineering). For more details, see Box 2.2. The OECD STRI heterogeneity indices complement the existing STRI's and presents indices of regulatory heterogeneity based on the rich information in the STRI regulatory database. The indices are built from assessing – for each country pair and each measure – whether or not the countries have the same regulation. For each country pair and each sector, the indices reflect the (weighted) share of measures for which the two countries have different regulation. Access the interactive version of the graph: https://public.flourish.studio/visualisation/18222772/.

Source: OECD STRI database (2024) and methodology based on Nordås, (2016[10]).

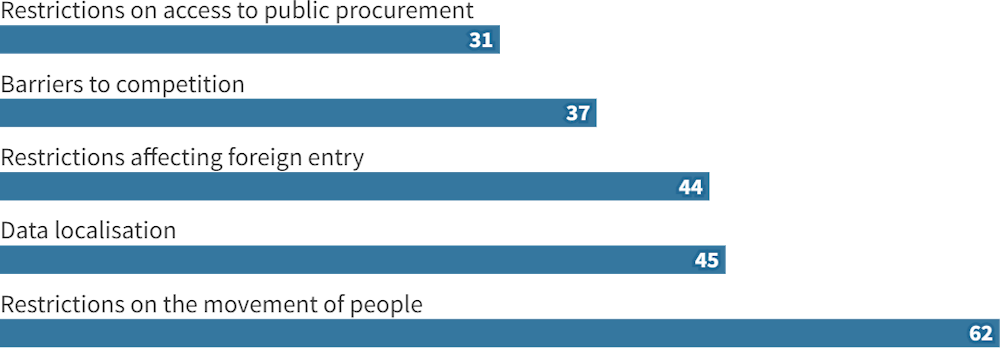

2.1.2. New policy barriers restrict the movement of people and impose data localisation requirements

The STRI captures different types of restrictions, some of which have become increasingly common over the past ten years. Over 60 new restrictions that affect the movement of services providers across borders were identified over the period 2014 to 2023 (Figure 2.6). These do not include temporary restrictions introduced during the COVID-19 pandemic, most of which had been lifted by 2023. Rather, they generally cover tightening policies on market entry for foreign nationals, including via stricter labour market testing, imposing quotas, or limiting the duration of stays. In addition, requirements related to data localisation have been increasing, with 45 such requirements identified during the 2014-2023 period in the countries covered by the STRI (Del Giovane, Ferencz and López González, 2023[11]).1 Restrictions on foreign entry, barriers to competition and restrictions on foreign access to public procurement markets have also been on the rise in recent years.

The STRI shows that many countries have implemented or amended foreign investment screening mechanisms over the past ten years, particularly in key services sectors such as air transport, telecommunications, and broadcasting services (Figure 2.7). Moreover, regulatory frameworks governing foreign investment screening have become more complex (OECD, 2024[12]).

Figure 2.6. Most common new restrictions in the STRI between 2014 and 2023

Number of new restrictions identified between 2014 and 2023

Note: Access the interactive version of the graph: https://public.flourish.studio/visualisation/18236601/.

Source: OECD STRI (2024).

Figure 2.7. Investment screening mechanisms in services sectors

Number of new FDI screening mechanisms introduced during 2014-23, per sector

Note: Access the interactive version of the graph: https://public.flourish.studio/visualisation/18240359/.

Source: OECD STRI (2024).

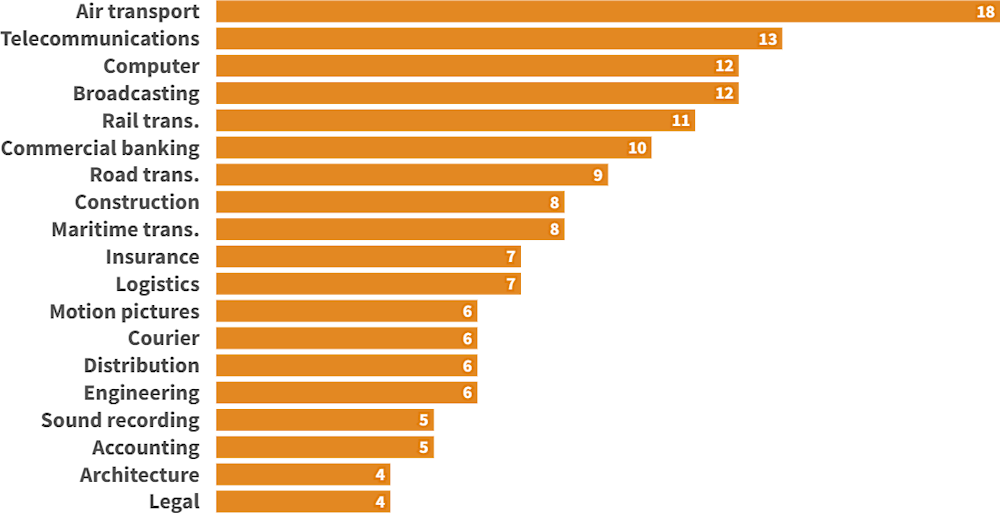

2.1.3. Market bridging services such as financial and professional services haved remained the most restrictive over the past ten years

Market bridging and support services such as financial and professional services have been the most affected by trade impediments over the past ten years, representing close to 30% of all restrictions in the STRI in 2023. This is followed by logistics and related services (around 25%), digital network services, and physical infrastructure-related services (around 22% each) (Figure 2.8). Both market bridging and logistics and related services have seen moderate liberalisation over the years, which has continued despite temporary increases in restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although the STRI averages in digital network services remain relatively low, developments over time show a clear trend towards more restrictions with an increase of 5.3% in the cluster average during 2014-2023. The same is true for physical infrastructure services, although after the peak levels during the pandemic years, the STRI shows a gradual return to pre-2020 levels.

Figure 2.8. Policy trends and developments across major services sector clusters, 2014-2023

Levels of STRI sector clusters, 2014 to 2023

Note: Calculated based the STRI sample of 38 OECD countries and Brazil, the People’s Republic of China, India, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, Peru, Singapore, South Africa, Thailand, and Viet Nam. The sectors covered in the STRI can be broadly organised around four clusters: 1. Digital network services (telecommunications, computer services, broadcasting, motion pictures and sound recording); 2. Logistics and related services (transport, courier, logistics and distribution services); 3. Market bridging and support services cluster (commercial banking, insurance, accounting and legal services); and 4. Physical infrastructure services cluster (construction, architecture and engineering). For more details, see Box 2.2. Access the interactive version of the graph: https://public.flourish.studio/visualisation/17488794/.

Source: OECD STRI (2024).

2.2. Services market access: Unfinished business

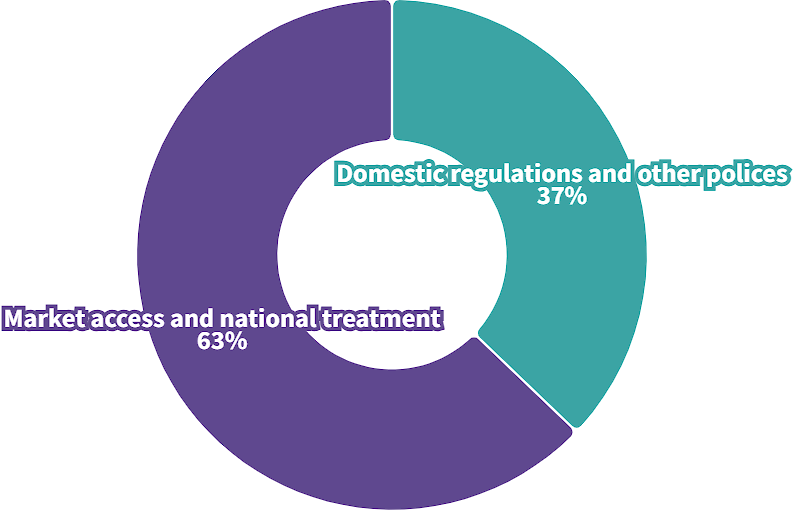

Effective services trade is conditional on the ability of firms to access new markets and on the elimination of discriminatory measures against foreign services and services suppliers. Close to two-thirds of all services trade barriers identified in the STRI affect market access conditions or national treatment of foreign services and services suppliers (Figure 2.9). The most common restrictions related to market access include limiting the maximum amount of foreign equity in local services’ firms, conditions on legal form, and the application of quotas or labour market tests for licensing and the movement of key services suppliers. The main barriers that affect national treatment include nationality or residency requirements for services providers, especially in professional services, and restrictions on the purchase of land and real estate.

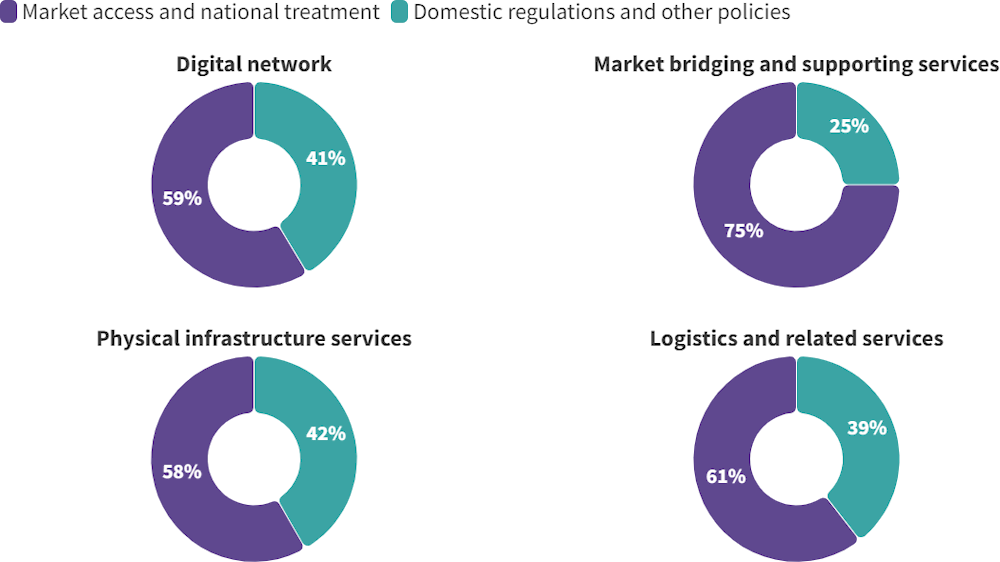

Barriers to market access and national treatment affect mostly market bridging and supporting services with 75% of all barriers recorded in the STRI (Figure 2.10). Market access barriers contribute close to 60% in the other three services clusters as well.

While global liberalisation efforts on services market access and national treatment have been slow, several countries have undertaken ambitious reforms over the past years, often making significant progress on opening services markets to foreign suppliers (see Box 2.1 on Indonesia and Box 2.3 on Brazil for examples).

Figure 2.9. Barriers to services market entry and behind the border

Proportion of services trade barriers affecting market access and national treatment, and domestic regulations and other policies as recorded in the STRI, 2023

Note: Access the interactive version of the graph: https://public.flourish.studio/visualisation/18244527/.

Source: OECD STRI (2024).

Figure 2.10. Barriers to services market entry and behind the border by cluster of services, 2023

Note : The sectors covered in the STRI can be broadly organised around four clusters: 1. Digital network services (telecommunications, computer services, broadcasting, motion pictures and sound recording); 2. Logistics and related services (transport, courier, logistics and distribution services); 3. Market bridging and support services cluster (commercial banking, insurance, accounting and legal services); and 4. Physical infrastructure services cluster (construction, architecture and engineering). For more details, see Box 2.2. Access the interactive version of the graph: https://public.flourish.studio/visualisation/18244880/.

Source: OECD STRI (2024).

Despite the levels of applied restrictions on market access and national treatment, the current services trade policies are more open than what countries committed to in the WTO GATS Schedules of Commitments (Miroudot and Pertel, 2015[13]). Indeed, market access and national treatment commitments listed in the GATS Schedules are modest both in terms of the number of sectors included in the schedules and the quality of bindings in relevant modes of supplies (WTO, 2001[14]). WTO Members are free to grant higher levels of market access and national treatment than are specified in their schedules, and many do so on a most-favoured-nation basis.

This means that considerations on future multilateral liberalisation on services trade could first look at the possibility of binding the degree of market access that presently exists. This would give services trade and investors a degree of security and predictability. While this would be more challenging for some sectors than others, there may be low hanging fruits especially where GATS commitments are unbound but in practice markets are relatively open.

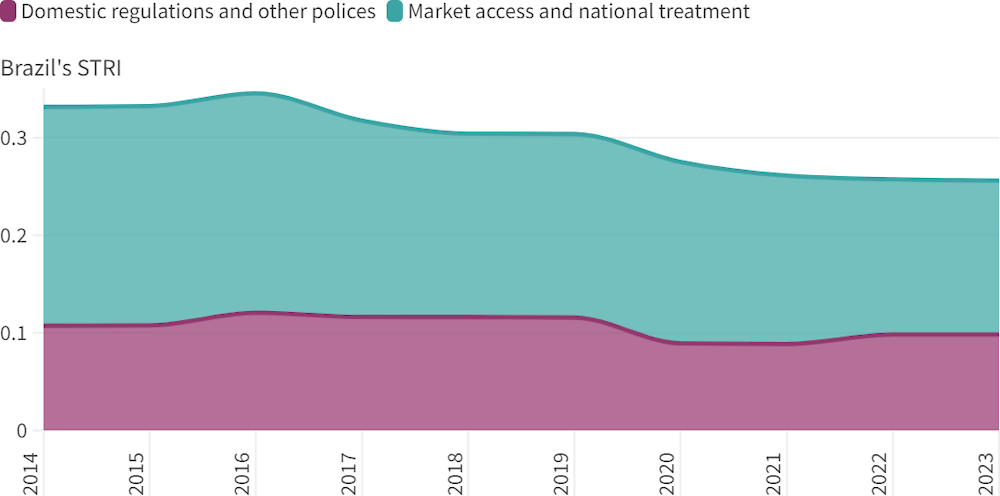

Box 2.3. Brazil and services trade reforms from 2014 to 2023

Brazil has undertaken important reforms over the past years that have contributed to lowering its STRIs both in terms of market access measures and domestic regulations. Examples include the following.

In 2023, Brazil introduced a de minimis regime. Goods included in postal or international air parcels of value below USD 50 can benefit from a zero per cent tax if they are intended for natural persons and the sender company meets the requirements of the compliance programme Programa Remessa Conforme, which aims to facilitate e-commerce transactions and companies that can voluntarily adhere to it. In 2023, a new resolution from the Agency of Civil Aviation suppressed the requirement to respect historic slots when these are allocated to new entrants; however, the Agency maintained the priority to continue the attribution of slots from the previous season. Brazil also reversed a policy change introduced in 2022 that required 65% of the statutory or contractual bodies of supervised entities in the insurance sector, as well as insurance brokers, to be residents.

In 2022, Lei No. 14.286, de 29 de dezembro de 2021 which concerns the foreign exchange market entered into force, recognising equal treatment of foreign and national capital. It suppressed the previous limitation for the National Treasury and other official public credit entities to guarantee or provide loans, credits, or financing to companies obtaining credit abroad and whose majority of the capital with voting rights belongs to non-residents. This law also eliminates restrictions on the possibility of banks headquartered in countries where Brazilian banks cannot fully operate to acquire more than 30% of voting rights within Brazilian banks.

Law 14195/2021 introduced important reforms, including the elimination of residency requirements for managers in most sectors (except legal and accounting services). Managers are no longer required to reside in the country, although they need to appoint a representative in the country for legal purposes. In the same year, Brazil introduced an important reform on the organisation of the Banco Central do Brasil (Brazil Banking Supervisory Authority) which eliminated the residency requirement for members of the board of directors or managers of the Brazilian Post and Telegraph Corporation (Empresa Brasileira de Correios e Telégrafos).

The rule establishing screen quotas in movie theatres expired in 2021, ending an important restriction in the motion pictures sector.

In February 2021 a new law reformed the governance structure of the Banco Central do Brasil. This reform included recognising bank’s independency and financial autonomy, as well as its full authority to license and enforce prudential measures. The reform includes a term limitation of its governing body.

In 2020, Brazil eased the licensing conditions for foreign banks and insurance providers, levelling the playing field compared to domestic financial services providers.

A new General Data Protection Law (Lei Geral de Proteção de Dados Pessoais) entered into force in September 2020. It provides the possibility to transfer personal data abroad if certain private sector safeguards are in place.

Figure 2.11. Brazil introduced important services trade reforms over the past decade

Changes in Brazil’s average STRI between 2014-23

Note: Access the interactive version of the graph: https://public.flourish.studio/visualisation/18245093/.

Source: OECD STRI database (2024).

2.3. Discussions on domestic regulations could be broadened

The STRI collects information on applied domestic regulations, including in areas such as barriers to competition, independence of the regulator, regulatory transparency in the rule-making process, administrative and procedural hurdles related to registering companies, as well as licensing and authorisation requirements across different sectors.

Close to half of domestic regulatory barriers affect services essential for supply chains, notably key transport sectors such as transport, courier, logistics, and distribution services (Figure 2.12). In other clusters, telecommunications services stand out as most affected given the high importance of measures affecting competition in that sector. Additionally, architecture services under the physical infrastructure services cluster are also more affected by domestic regulatory barriers. The most common barriers affecting some these sectors are summarised in Table 2.1.

Figure 2.12. Barriers in domestic regulations across STRI sectors, 2023

Note: Access the interactive version of the graph: https://public.flourish.studio/visualisation/18315808/.

Source: OECD STRI database (2024).

Table 2.1. Domestic barriers to services trade in selected sectors

Top restrictions presented as share of total countries covered in the STRI, 2023

|

|

Measure |

Share of countries having a restriction |

|---|---|---|

|

Common barriers across regulated sectors |

Lack of a legal obligation to communicate regulations to the public within a reasonable time prior to entry into force |

66% |

|

Lack of an adequate public comment procedure open to interested persons, including foreign suppliers |

18% |

|

|

No obligation to inform applicants about the final decision |

28% |

|

|

No maximum time set for the regulator for decisions on applications |

20% |

|

|

Restrictions related to the duration and renewal of licenses |

12% |

|

|

Applications in electronic format are not accepted |

42% |

|

|

Air transport |

State ownership in major airline |

40% |

|

No commercially exchange of airport slots |

52% |

|

|

Exemption of air carrier alliances from competition law |

62% |

|

|

Rail freight |

State ownership in major rail freight provider |

76% |

|

Lack of independence of the regulator |

40% |

|

|

Transfer or trading of infrastructure capacity is prohibited |

60% |

|

|

Telecommunications |

State ownership in major telecommunications provider |

54% |

|

Lack of independence of the regulator |

38% |

|

|

Lack of transparent and non-discriminatory rates on interconnection for foreign operators |

52% |

|

|

Architecture |

Government regulated fees |

18% |

|

Lack of independence of the licensing authority from the government or private sector |

32% |

|

|

Restrictions on advertising |

20% |

Note: The STRI covers 50 countries. Percentages are presented as share of countries having a restriction of this total.

Source: OECD STRI (2024).

Addressing these barriers can bring substantial benefits. Over 70 WTO Members – representing over 90% of global services trade – participate in the Joint Initiative on Services Domestic Regulation with the aim to incorporate new disciplines on good regulatory practices on services in their schedules of commitments after these officially entered into force on 27 February 2024, on the margins of the 13th WTO Ministerial Conference in Abu Dhabi. This was a landmark achievement for advancing the facilitation of services supplies globally and it is expected to lower trade costs up to USD 150 billion annually (OECD-WTO, 2021[15]) (WTO, 2024[16]). Moreover, estimates show that benefits would be particularly high for lower- and upper-middle-income economies and that these would have spill-over effects to non-participating economies. Timely and effective implementation is key for these benefits to materialise.

Beyond disciplines related to licensing and regulatory transparency, further policy reforms are needed to address the remaining challenges that affect domestic services markets. Table 2.1 shows three potential areas for reforms: reducing state participation in markets through state-owned enterprises; promoting the independence of regulatory bodies; and applying market-based competition rules.

Government presence in state-owned or state-controlled enterprises remains a challenge, especially in strategic sectors like transport and telecommunications. Moreover, such intervention can undermine the independence of regulatory authorities which affects key sectors such as rail freight transport, telecommunications, and architecture services. Market-based competition rules entail the elimination of unnecessary exemptions provided for anti-competitive agreements between competitors, lifting price regulations, and allowing the commercial transfer of capacity among services providers.

2.4. Digitally-enabled services face great barriers and growing fragmentation

Digitalisation is having a profound impact on trade, substantially re-shaping the way in which services are traded across borders (OECD, 2023[6]) (IMF, 2023[17]). By 2020, digital trade represented 25% of global trade, or just under USD 5 trillion, driven to a large extent by increases in trade in digitally deliverable services (OECD, 2023[6]). Leveraging the benefits of digital transformation requires well-regulated services that enable fast, reliable, and affordable connections across digital networks. For instance, telecommunications services are essential for networks to connect, while computer services and information and communication technology (ICT) services enable end-to-end communication. Content-related services, notably audio-visual services, have been particularly affected by rapid digitalisation as movies, music and other content can be more easily shared or streamed through digital platforms.

Across these sectors, regulatory barriers may impact different policy areas (Figure 2.13). For instance, in broadcasting services, the STRI shows that about 70% of all recorded barriers affect the entry of foreign broadcasting providers into domestic markets. In the case of telecommunications services, barriers to competition have the greatest impact (36%), followed by barriers to foreign entry (34%). In computer services, restrictions on the movement of computer professionals make up 35% of the impediments identified. In motion pictures and sound recording services, discriminatory measures have a higher impact on foreign content providers (e.g. through subsidies, local content, or post-production requirements).

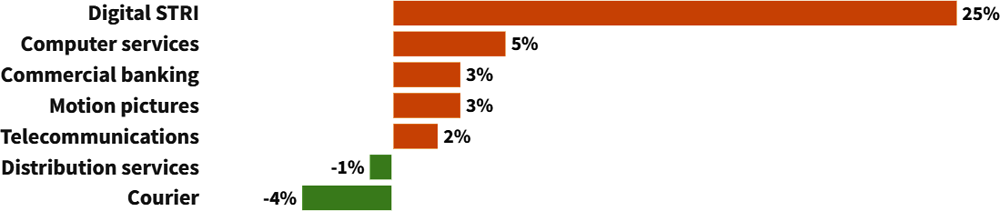

These findings are supported by those from the Digital STRI that covers cross-cutting barriers affecting digitally enabled services in more than 100 countries.2 On a global level, such barriers increased by 25% between 2014 and 2023 (Figure 2.14), driven by an increasing number of measures affecting communication infrastructure and connectivity, including in the context of cross-border data flows, data localisation requirements, and lack of pro-competitive regulations on interconnections across communication networks. Rising trade barriers have also affected other digital sectors, including computer services (5%), motion pictures (3%), and telecommunications (2%).

Figure 2.13. Composition of barriers across digital network services

Composition of STRI by proportion of policy area, 2023

Note: Access the interactive version of the graph: https://public.flourish.studio/visualisation/17852120/.

Source: OECD STRI database (2024).

Figure 2.14. Barriers to digital trade have increased in recent years

Change in average Digital STRI and the STRI sectors for digital networks, 2014-23

Note: The STRI and Digital STRI indices take values between zero and one, one being the most restrictive. Digital STRI coverage here is only for the 50 countries covered by the STRI, so as to match coverage for the other sectors. Access to interactive version of the graph: https://public.flourish.studio/visualisation/18244338/.

Source: OECD STRI database and Digital STRI database (2024).

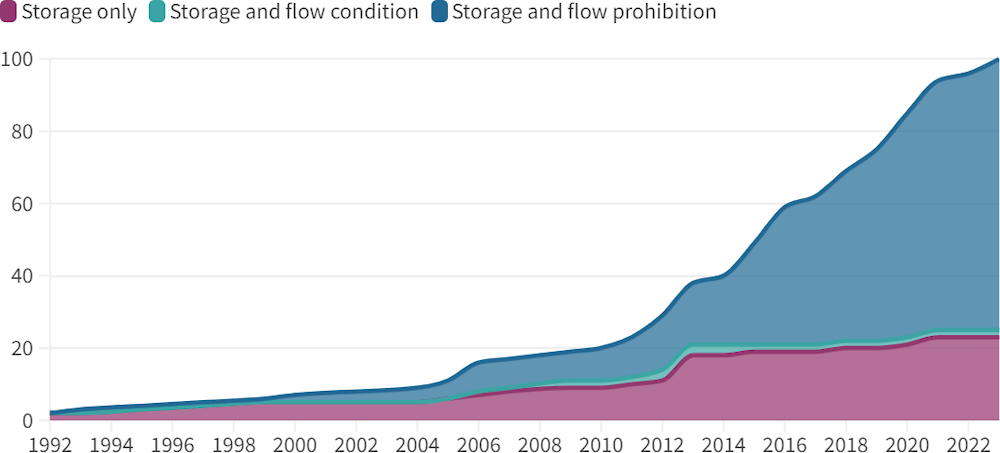

A key business and policy challenge in digital trade today is the rising volume of data localisation requirements affecting business operations, production, and consumption (Figure 2.15). By early 2023, close to 100 data localisation measures were in force across 40 countries (Del Giovane, Ferencz and López González, 2023[11]), with more than half of these emerging in the past decade. 45 such measures are also recorded in the STRI (see Figure 2.6). Such measures are also becoming increasingly restrictive. By 2023, more than two-thirds that were in place imposed a local storage and processing requirement without the possibility for data to flow outside the country, which is the most restrictive form of data localisation identified. More sensitive data, including health, financial and public sector data, are associated with more restrictive data localisation measures.

Figure 2.15. Data localisation is growing and becoming more restrictive

Note: Data localisation measures are defined as explicit requirements that data be stored or processed domestically. Access the interactive version of the graph: https://public.flourish.studio/visualisation/18243107/.

Source: Del Giovane, Ferencz and Lopez Gonzalez (2023[11]).

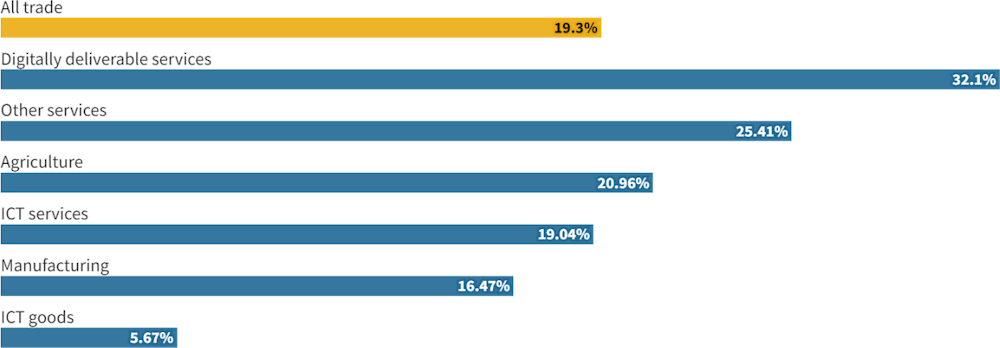

Growing restrictions on digital trade highlight the importance of strengthening international co-operation to address these challenges, in particular through multilateral efforts at the WTO (Box 2.4). Making regulations less restrictive can bring significant payoffs. A 0.1-point reduction in the domestic DSTRI score, which captures an important domestic regulatory reform, is associated with a decrease in export costs of 19.3% (Figure 2.16) (López González, Sorescu and Kaynak, 2023[5]). The effect is highest for digitally-deliverable services (-32.1%) and ‘other services’ exports (-25.4%). The benefits of reform are not limited to services. An equivalent reduction in the domestic DSTRI score is associated with a 21% decrease in export costs in agriculture and food sectors, and a 16.5% decrease in export costs in manufacturing sectors.

Figure 2.16. Domestic regulatory reforms can have an important effect on exports

Ad valorem equivalent of reducing the DSTRI by 0.1 points on the costs of export

Note: The figure shows by how much export costs increase as a result of a 0.1-point increase in the Digital STRI. Ad valorem equivalent can be calculated following Benz and Jaax (2020[18]) as exp(-(-0.1*DSTRI coefficient)/(elasticity-1))-1. Using the DSTRI coefficients from Lopez-Gonzalez, Sorescu and Kaynak (2023[19]) and the elasticities from Egger et al. (2021[20]). Access the interactive version of the graph: https://public.flourish.studio/visualisation/18245656/.

Source: López González, Sorescu and Kaynak (2023[5]).

Box 2.4. The e-commerce moratorium post-MC13: Ensuring discussions are evidence based

At the 13th WTO Ministerial Conference1, WTO Members agreed to “maintain the current practice of not imposing customs duties on electronic transmissions until the 14th Session of the Ministerial Conference or 31 March 2026, whichever is earlier.”1 This was largely recognised as a key achievement of the Ministerial despite it stating that “the moratorium and the Work Programme will expire on that date.”

The MC13 Ministerial Decision also came with a call to “hold further discussions and examine additional empirical evidence on the scope, definition, and the impact that a moratorium on customs duties on electronic transmissions might have on development, and how to level the playing field for developing and least-developed country Members to advance their digital industrialisation.”

Evidence shows that the potential fiscal implications of the moratorium are small, representing on average around 0.1% of total government revenue or 0.68% of total customs revenue (Andrenelli and Lopez Gonzalez, 2023[21]) (IMF, 2023[17]). Foregone customs revenue is likely to be offset by rising GST/VAT revenue on digital services imports. At the same time, lifting the moratorium would imply losses in competitiveness and increased trade costs that will hit developing countries and smaller actors, including SMEs and women owned firms, the most.

1. The WTO Ministerial took place in Abu Dhabi in February-March 2024.

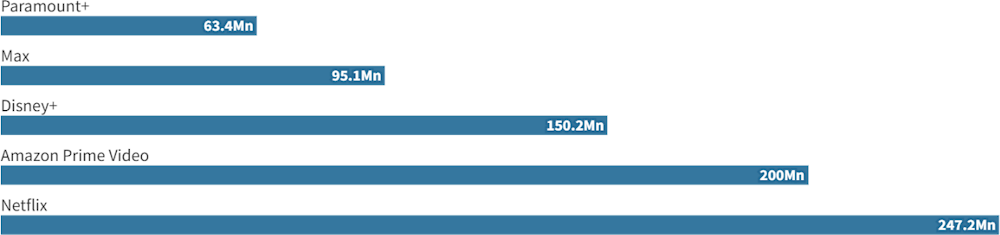

Sector in focus: Motion pictures

The sector of motion pictures has benefitted from rapid digitalisation and increased technological developments that facilitate the streaming of media content over the Internet. The rise of streaming services and digital distribution platforms has transformed how audiences consume films, leading to shifts in distribution models and revenue streams. Netflix, Amazon Prime Video, and Disney+ with close to a combined 600 million subscribers globally are leading the global market (Figure 2.17). Adapting to these changing consumption patterns requires flexibility and innovation from filmmakers and distributors. As movies on platforms are increasingly released simultaneously across multiple countries, barriers to trade in motion pictures become more relevant as regulatory divergence can add additional costs and delays.

Figure 2.17. Streaming services are becoming an increasingly important channel for movie distribution

Streaming services with the most subscribers globally as of 31 December 2023, in millions

Source: Forbes and Digital Trends, 2024.

Drawing on the STRI data, some key challenges can be identified that affect international trade in motion pictures services, particularly streaming platforms (Figure 2.18):

Barriers affecting the distribution of new content: The global film market is highly competitive, with a vast array of content available to audiences through traditional cinemas, streaming platforms, and other distribution channels. Breaking through the clutter to reach international audiences requires effective marketing strategies and strong distribution networks. Moreover, various countries have strict regulations and censorship laws governing the import and distribution of foreign films. Navigating these regulations can be complex and time-consuming for filmmakers and distributors. Over 30% of the countries covered in the STRI impose restrictions on streaming and downloading platforms, while over 15% impose requirements for on-demand providers to promote local works, including through the application of quotas which can be more limiting when the repository of available foreign films is very large but the domestic one is more limited. In 20% of the countries, quotas for local motion pictures apply also in television or theatres.

Localisation requirements for content production: While dubbing or subtitles are generally considered effective means to overcome language barriers in films, mandating that such measures take place locally or using local production companies can limit efficiencies. Dubbing is currently regulated in close to 30% of the countries covered. Additionally, in 14% of the countries, movie productions are subject to sourcing part of the cast and crew locally. This can be further exacerbated by the lack of visa exemptions or dedicated visa for cast and crew that can make temporary entry for production purposes faster and easier. Currently, only seven of the 50 countries covered have visa exemptions or special visa categories for foreign film crew.

Competition in the market: In many countries, film industries receive government support to promote local culture and creativity. While this is an important measure to protect cultural values, it can become a challenge if applied discriminatively in favour of domestic content producers. Over half of the countries employ some forms of discriminatory treatment on eligibility to subsidies. Market competition can also be affected by strong government involvement in the sector. In 26% of the countries, the government owns or controls a major company operating in the production or distribution of movies.

Rising copyright infringement and lack of effective enforcement: Most market transactions in the film industry are done through the transfer of property rights from a seller to a buyer at an agreed price or allowing the right to use somebody’s property for a fee. Most countries have incorporated international standards on copyright protection in their legislation, but differences remain on the scope of exceptions and how copyright infringements are handled. Digital piracy remains a significant challenge for the film industry, impacting revenues and discouraging international distribution. Pirated copies of films can be easily distributed across borders, undermining legitimate sales and licensing agreements.

Figure 2.18. Key trade barriers affecting motion picture services

Composition of key sector-specific trade barriers in motion picture services across all countries covered, 2023

Note: Access the interactive version of the graph: https://public.flourish.studio/visualisation/18319471/ .

Source: OECD STRI (2024).

2.5. Lowering services barriers is a gateway to strengthening the resilience of supply chains and environmental sustainability

2.5.1. Logistics, transport and other services supporting supply chains

Services play a crucial role in supporting global supply chains by enhancing efficiency, reducing costs, and ensuring timely delivery of goods. Transport services and logistics services, such as cargo-handling or warehousing, are fundamental to the seamless movement of products from manufacturers to consumers. Advanced technology services - including real-time tracking, data analytics, and automation - enable companies to monitor and optimise their supply chains, making them more responsive and resilient. These services are also relevant in the context of growing digital trade which results in a growing volume of trade in parcels (López González and Sorescu, 2021[22]).

In addition to operational benefits, services are integral to enhancing environmental sustainability within supply chains. Green logistics practices, such as the use of fuel-efficient transportation modes, route optimisation, and sustainable packaging, significantly reduce the carbon footprint of supply chain activities. Tailored services, e.g. consulting services, can help develop and implement strategies that minimise waste, improve energy efficiency, and comply with environmental regulations. Moreover, services such as reverse logistics support the recycling and reuse of materials, contributing to a circular economy. By leveraging these services, companies can meet regulatory requirements, as well as fulfil corporate social responsibility goals, enhancing their brand reputation and competitiveness in a market increasingly concerned with sustainability.

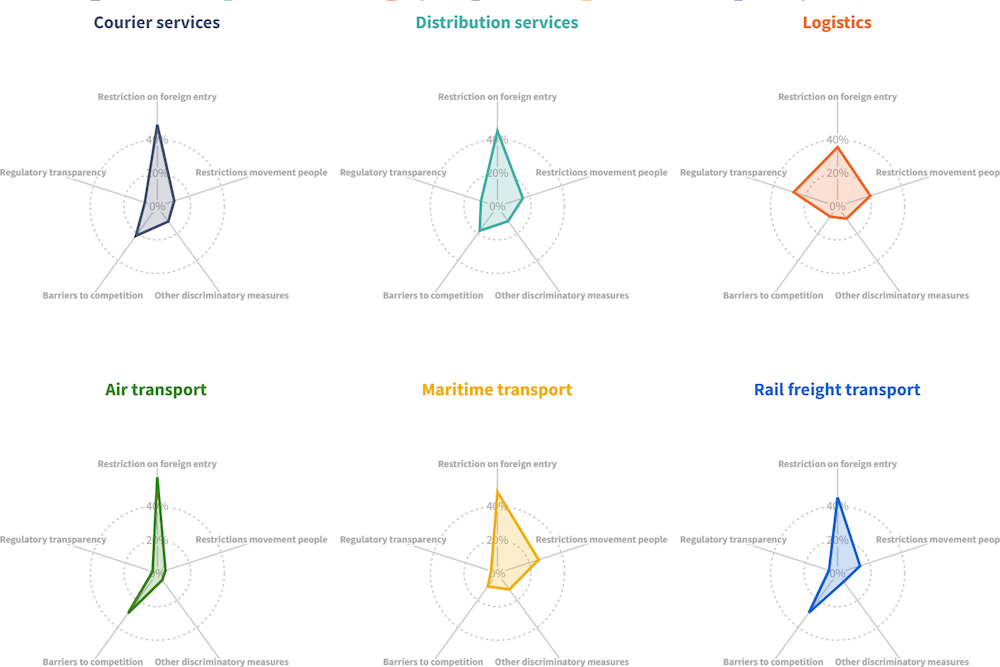

The STRI covers several services sectors that are relevant enablers of supply chains, including four transport services (air, maritime, rail, and road freight transport), four logistics services (cargo handling, storage and warehousing, freight forwarding, and customs brokerage), as well as distribution services and courier services.

Figure 2.19 depicts the STRI composition of logistics, courier, and distribution services. It highlights that barriers in logistics services to foreign entry account for a substantial share of all barriers (e.g. 45% in customs brokerage and close to 40% in cargo-handling). Barriers to regulatory transparency, including transparency of selected processes at the border, are also relatively high in the logistics sectors, accounting for 35% of barriers in freight forwarding and around 30% in both storage services and customs brokerage. In courier services, barriers to foreign entry represent half of all barriers due to the conditions affecting foreign investment, particularly in postal services. Courier and express delivery services tend to be more open and liberalised, but postal services remain subject to high levels of restrictions. Lastly, barriers affecting foreign entry in distribution services are also dominant (45%), followed by barriers to competition (20%), and restrictions on the movement of people (15%).

Figure 2.19. Logistics, transport and other services supporting supply chains

Composition of STRI by proportion of policy area, 2023

Note: Access the interactive version of the graph: https://public.flourish.studio/visualisation/18073420/.

Source: OECD STRI database (2024).

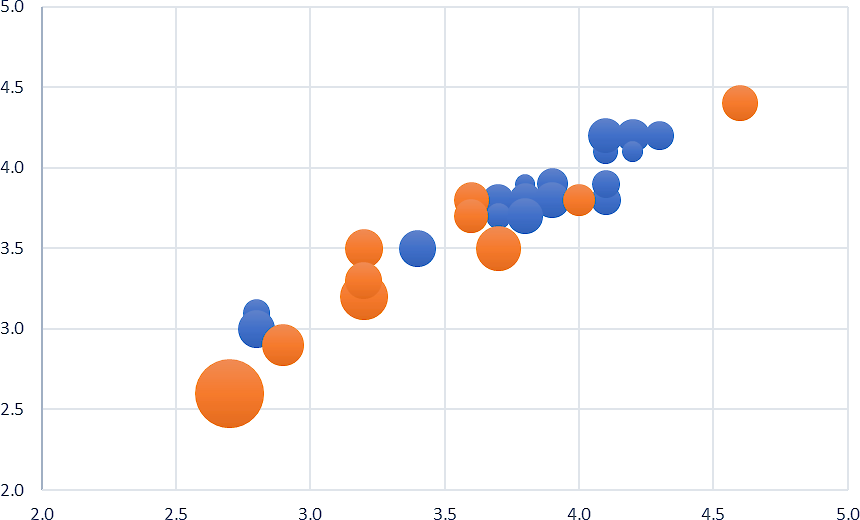

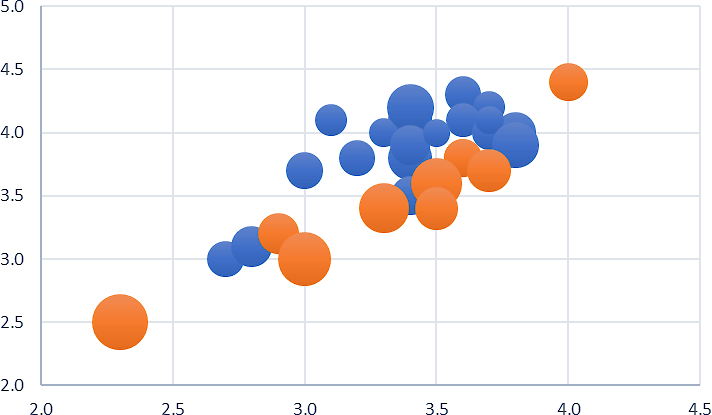

Moreover, there appears to be a consistent negative correlation between the restrictiveness of both logistics and maritime transport services and various logistic performance indicators (LPI) (World Bank, 2023). Figure 2.20 highlights correlations between the STRI for these two sectors and relevant World Bbank LPI scores for logistics infrastructure, competence and quality, international shipments, and tracking and tracing. Countries with lower trade restrictiveness in these areas tend to score higher across all these indicators, meaning better overall logistics performance. This is relevant for non-OECD countries where the level of restrictiveness in logistics and transport sectors tends to be higher.

Figure 2.20. Open transport and logistics markets matter for global supply chain networks

Relation between STRIs for logistics services (left) and maritime transport (right) and components of the WB Logistics Performance Index across OECD countries (blue) and non-OECD countries (orange), 2023

Note: The size of the bubble shows the STRI value where a bigger bubble depicts a higher STRI value. The left panel plots the LPI infrastructure score and logistics competence and quality score against the STRI for logistics services in selected OECD and non-OECD economies for 2023. The right panel plots the LPI international shipments scores and tracking and tracing scores against the STRI for maritime transport services in selected OECD and non-OECD economies for 2023.

Source: World Bank Logistics Performance Index 2023 and OECD STRI 2024.

Sector in focus: Maritime transport services

Maritime transport is a key sector for the efficient connection across supply chains. It is estimated that more than 80% of merchandise trade by volume and over 70% of global trade by value are carried by sea (UNCTAD, 2022[23]). The market is highly concentrated with the top five ship-owning countries accounting for nearly a half of world’s tonnage fleet in 2022.

Geopolitical tensions, unrest, and protectionist measures can disrupt international trade flows and affect maritime transport routes and operations. Uncertainty surrounding trade policies and trade barriers can also deter investment and potential efficiency gains from streamlining operations. The maritime industry is facing growing pressure to reduce its environmental footprint, particularly concerning air and water pollution, and greenhouse gas emissions.

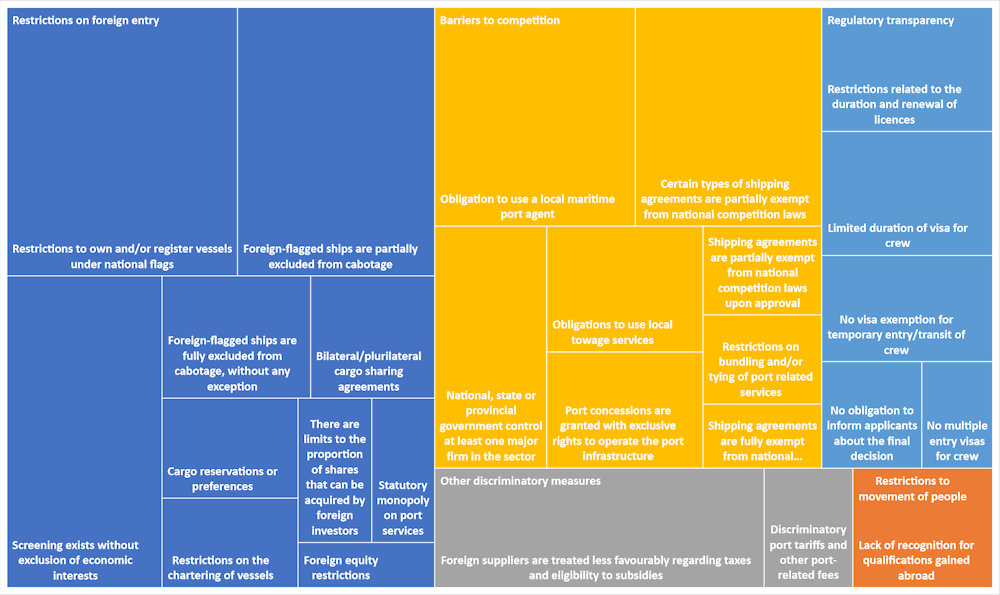

Drawing on STRI data, some key challenges can be identified that affect international trade in maritime transport services (Figure 2.21).

Restricted access to certain market segments and cabotage operations: Conditions on flying the national flag are not considered a trade restriction per se, but in cases where flying the flag is linked to accessing certain segments of the market, discrimination related to registering under the national flag creates restrictions on foreign entry. More than 80% of the countries in the STRI impose various conditions to registering vessels in their national registry, thereby limiting the provision of maritime cabotage. Close to 70% of countries in the STRI prohibit certain cabotage operations for foreign-flagged vessels, while a quarter prohibit all cabotage for foreign operators. Cargo-sharing agreements and cargo reservations for specific types or shares of their domestic cargoes to the national fleet have become fewer in recent years but continue to exist in 20% of the countries covered. Such measures, together with strict cabotage policies, considerably limit foreign vessel operations domestically even when this is essential to improving efficiency in cargo distribution, alleviating capacity constraints on domestic vessels, and providing incentives for investments in port infrastructures.

Constraints at ports: Ports are often publicly owned, while port services are usually provided by private companies operating under concessions. However, 12% of the countries in the STRI continue to maintain restrictions to the provision of such services, including statutory monopolies that preclude the entry of other port operators. Moreover, concessions for port services granted with exclusive rights to operate exist in 24% of these countries, thus limiting the scope of other services providers at ports. Discriminatory tariffs for port services exist in major ports across 15% of the countries and obligations to use only local auxiliary services, such as towage or maritime port agents, exist in the majority of the countries covered.

State ownership and market competition: Government ownership or control in major domestic maritime transport operators exist in close to 40% of the countries covered, highlighting the high degree of government involvement in this sector. Over half of the countries covered exempt certain shipping agreements from competition law and 10% provide full exemption to all shipping agreements from national competition law. In addition, more than half of the countries have tax relief measures or other incentives for domestic shipping companies to increase the competitiveness of the national fleet.

Figure 2.21. Key trade barriers affecting maritime transport services

Composition of key sector specific trade barriers in maritime transport across all countries covered, 2023

Note: Access the interactive version of the graph: https://public.flourish.studio/visualisation/18319471/ .

Source: OECD STRI (2024).

2.5.2. Physical infrastructure services

Architecture, construction, and engineering services are essential for infrastructure development. They also contribute to advancing industrial development and essential infrastructure such as roads, bridges, and buildings. Construction services have historically been considered strategic and are often closely linked to procurement and allocation of fiscal resources. Architects and engineers are key professionals contributing to the design and technical feasibility of constructions projects. These service areas are highly complementary and often provided by the same company. They also account for a significant share of gross domestic product (GDP) and employment in most countries. Public works, such as roads and public buildings, account for about half of the market for construction services.

These sectors are also highly relevant to achieve environmental sustainability goals. Engineering services are crucial inputs for the development of innovations to enhance environmental sustainability across the board, and for their adoption as industrial and commercial applications. Architecture and construction services are crucial inputs to pursue energy efficiency as well as to design and install necessary infrastructure for the green transition.

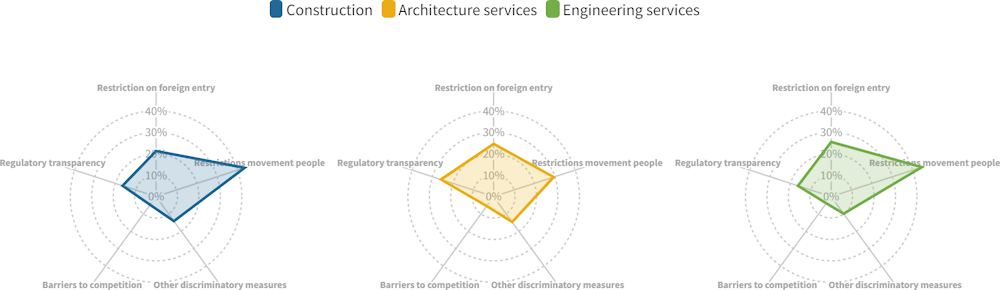

Figure 2.22 shows the composition of the STRI for these three sectors. Across all three, barriers to the movement of people predominate, accounting for over 40% of all barriers in construction and engineering services and 30% in architecture services. This creates hurdles in these sectors given the importance of cross-border movement of professionals. Barriers to foreign entry contribute between 20% and 25% of all barriers, while the category of “other discriminatory measures”, which includes public procurement, accounts for between 10% and 15%.

Figure 2.22. Physical infrastructure related services

Composition of STRI by proportion of policy area, 2023

Note: Access to interactive version of the graph: https://public.flourish.studio/visualisation/17852453/.

Source: OECD STRI (2024).

Sector in focus: Construction services

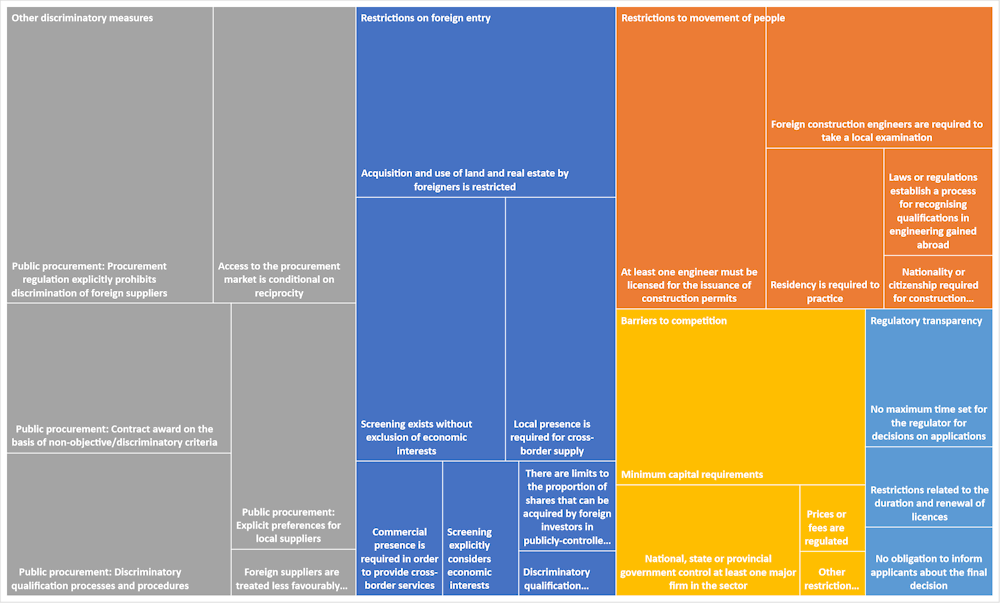

Drawing on the STRI data, some key challenges can be identified that affect international trade in construction services (Figure 2.23).

Access to public procurement markets for foreign providers of construction services: In light of the importance of government demand for these services, restrictions in public procurement can have a significant bearing on the construction sector. In 40% of the countries covered by the STRI, non-discriminatory access for foreigners to public procurement is limited to nationals from countries participating in the WTO Government Procurement Agreement (GPA) or countries that are parties to a preferential trade agreement. Sixteen of the 50 countries covered in the STRI are not parties to the WTO GPA. Moreover, in close to 30 countries, access to the procurement market outside the WTO GPA can be granted only on condition of reciprocity. Even when market access is allowed to foreign providers, explicit preferences (e.g. price rebates) may be granted to local tenderers. This is currently the case in 42% of the countries in the STRI.

Limited foreign acquisitions of land or real estate: Restrictions on land and real estate acquisitions may limit the ability of foreign construction firms to enter certain markets or acquire strategically located properties. In regions where foreign ownership of land is restricted or subject to additional taxes or fees, foreign construction firms may face higher costs associated with leasing land or acquiring real estate through alternative means. In close to 70% of the countries covered in the STRI, acquisition or use of land and real estate is subject to certain restrictions or limitations for foreigners.

Limits on the movement of capital and foreign labour: Construction services are a relatively labour-intensive sector (both skilled and un-skilled), which is typically reflected in a higher share in employment than in GDP for most countries. In light of the nature of construction activities, the potential for mechanisation and automation also remains more limited than in other sectors. Consequently, restrictions on labour mobility and differences in workforce skills and qualifications can affect the recruitment, training, and deployment of workers for international construction projects. All the countries in the database limit market access for natural persons providing services on a temporary basis as intra-corporate transferees, contractual services suppliers or independent services suppliers. Most prominent restrictions are labour market tests and limited durations of stay (less than three years) exist in over 70% of the countries covered. The movement of qualified construction personnel may be affected by licensing and related issues. These include nationality or residency requirements for construction engineers, which exist in over a third of the countries as well as requirements for foreign engineers to take a local examination to obtain qualifications which exists in 44% of the countries. In 60% of the countries, at least one engineer must be licensed for the issuance of construction permits. Lastly, performance requirements mandating minimum quotas on the shares of local workforce to be employed in companies operating domestically exist in a quarter of the countries covered.

Regulatory fragmentation: Varying regulations and legal frameworks across countries can pose significant challenges to international construction firms. Different licensing requirements, building codes, and standards can create barriers to entry as well as hinder seamless operations. These can be exacerbated by other trade restrictions on construction materials and equipment, making international projects more expensive and less competitive.

Figure 2.23. Key trade barriers affecting construction services

Composition of key sector specific trade barriers in construction services across all countries covered, 2023

Note: Access the interactive version of the graph: https://public.flourish.studio/visualisation/18319471/.

Source: OECD STRI (2024).

2.6. Lowering barriers on financial and professional services is key to enabling other economic activities

With the growing complexity of international business models, market bridging and support services are essential for firms supplying services across multiple markets. For example, financial services ensure access to credit, payment systems, and insurance to scale up production and sales. Trustworthy, transparent, and easy to understand accounting information is needed to assess creditworthiness and to ensure compliance with financial regulations. Legal services are necessary to support operations at home and affiliates abroad, to ensure compliance with regulations, and to support the enforcement of contracts.

Banking and insurance services support production and exchange in virtually all economic activities. As such, this sector is an important engine for economic growth, but also a potential source of systemic risk.3

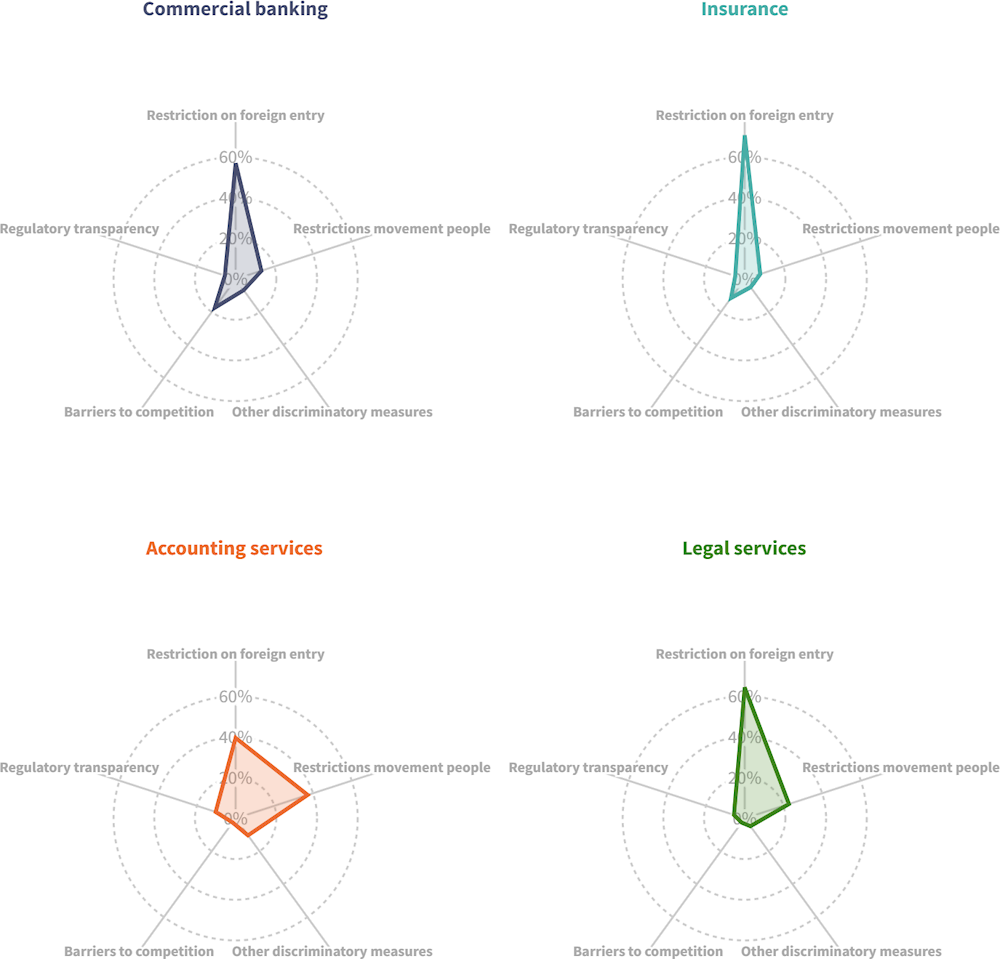

Figure 2.24 shows the composition of the STRI by policy areas across market bridging and support services. It shows that market entry barriers are high across all sectors, especially in financial services and legal services. For instance, restrictions on foreign entry account for 70% in insurance services, 64% in legal services and 57% in commercial banking. In accounting services, both market entry barriers and barriers to the movement of people contribute to approximately 40% of all barriers.

Figure 2.24. Market bridging and supporting services

Composition of STRI by proportion of policy area, 2023

Note: Access the interactive version of the graph: https://public.flourish.studio/visualisation/17852516/.

Source: OECD STRI (2024).

Sector in focus: Commercial banking services

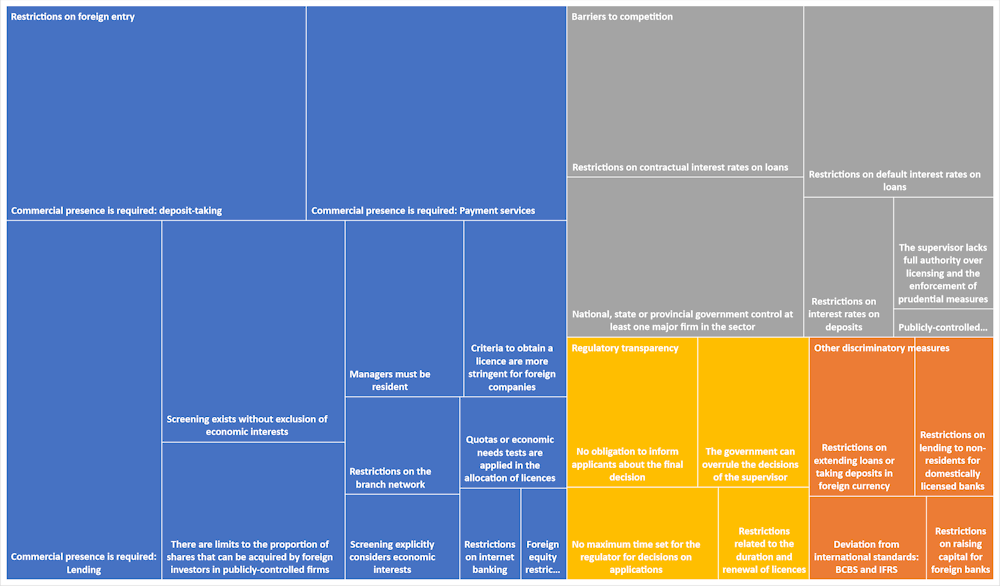

Drawing on the STRI data, some key challenges can be identified that affect international trade in commercial banking services (Figure 2.25).

High barriers on cross-border trade: Restrictions on market access and ownership in foreign markets hinder the expansion of financial service providers. Requirements for a local presence, such as establishing physical branches, can be burdensome. The STRI results are mainly driven by restrictions on foreign entry, where significant impediments remain: the requirement for a physical commercial presence; on foreign equity limits: on restrictions on legal form; on localisation requirements for foreign bank managers: discriminatory licensing criteria; and restrictions on cross-border transactions. Setting up a local affiliate or a branch is the primary mode of entry into foreign markets for commercial banks and insurance carriers, although the rise of electronic distribution channels has expanded the potential for cross-border trade in financial services. About 80% of the countries covered in the STRI impose a commercial presence requirement for some types of banking services and virtually all countries impose this for deposit activities. These requirements, along with barriers concerning internet-only banking, limitations on branch networks, and strict requirements on local storage or processing of financial data, can effectively hinder the potential expansion of online financial services. Some of the challenges related to cross-border trade in financial services could be overcome by mutual recognition of domestic laws and regulations. An innovative approach – a possible model for others – is the Berne Financial Services Agreement concluded by the United Kingdom and Switzerland, and signed in December 2023 (Box 2.5).

Barriers to competition and state control: Barriers to competition significantly impact the indices. These encompass regulations on products and prices, as well as preferential treatment granted to state-owned financial institutions. Some countries implement protectionist measures to shield domestic financial institutions from foreign competition, including preferential treatment, subsidies, or regulatory bias. State control of financial institutions remains widespread; the majority of countries have a state-controlled bank amongst their five largest banks, and respectively 36%, 32%, and 28% of countries have a state-controlled life insurer, non-life insurer, or reinsurer among the top five institutions in their country.

Lack of independence of the regulatory authority: A common issue affecting a quarter of the covered countries is the lack of independence of the regulatory and supervisory authorities whose decisions may be overridden by the government. While strict price controls, pre-approval requirements for financial products, and restrictions on lending or capital raising have largely been abolished in OECD countries, they persist elsewhere.

Licensing and judicial enforcement mechanisms: Licensing and authorisations are standard requirements in commercial banking, but the process may be discriminatory or less transparent for foreign financial institutions. In 26% of the countries covered in the STRI the conditions to obtain a license for banking services are more stringent for foreign applicants. Applicants for a license need not be informed of the reasons for denial of a license in close to a quarter of the countries covered, while in 20% there is no maximum time set for the regulator to decide on applications. Differences in legal systems and lack of enforcement mechanisms can also impede the resolution of cross-border disputes and enforcement of contracts, reducing confidence in international financial transactions.

Regulatory fragmentation: Varying regulatory frameworks across countries pose a significant challenge. Compliance with diverse regulations regarding licensing, capital requirements, and administrative compliance can be complex and costly for financial institutions. While adoption of international standards, including on capital risk weighting under the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, international financial reporting or anti-money laundering are more prevalent in recent years, not all countries have adopted these standards. In addition, volatility in currency exchange rates and restrictions on currency convertibility can complicate financial transactions and increase risks for market participants.

Technological disruption: While electronic distribution channels have expanded opportunities for cross-border trade, they also introduce cybersecurity risks and regulatory concerns, particularly regarding data privacy and local data storage requirements.

Figure 2.25. Key trade barriers affecting financial services

Composition of key sector specific trade barriers in commercial banking across all countries covered, 2023

Note: Access the interactive version of the graph: https://public.flourish.studio/visualisation/18319471/.

Source: OECD STRI (2024).

Box 2.5. Enabling greater cross-border trade in financial services: The Berne Financial Services Agreement

In December 2023, the United Kingdom and Switzerland – two of the largest exporters of financial services – signed a new agreement on Mutual Recognition in Financial Services aimed at improving the supply of financial services between the two countries through outcomes based mutual recognition of the domestic regulatory and supervisory frameworks.

The agreement sets a new and innovative model of mutual regulatory recognition, fosters greater market access, and regulatory certainty. Moreover, it reduces regulatory barriers and establishes an institutional framework for improving regulatory and supervisory co-operation.

A key provision of the agreement provides that each party considers that domestic regulatory and supervisory frameworks of the other party achieve equivalent outcomes regarding financial stability, market integrity, and the protection of investors and consumers within the scope of the agreement and its sectoral annexes. This entails moving away from traditional line-by-line equivalence assessments, and employing a more flexible and pragmatic approach to international financial regulation. It also means that businesses avoid having to navigate complex and potentially different regulatory requirements in both countries.

The agreement provides for greater market access for a range of wholesale financial services, e.g. on non-life insurance for renewable energy, directors' and officers' liability, sellers' and buyers' warranty, indemnity, and cyber insurance. Other insurance agreements tend to be largely limited to maritime, aviation, and transport risks. Bilateral market access also extends to the supply of services auxiliary to insurance, such as consultancy, actuarial, risk assessment and claims services.

2.7. Ways to deliver services are changing

The STRI measures can be broken down along three of the four modes of services supplies defined by the WTO (modes 1, 3, and 4)4 reflecting the core impact that regulatory measures would have on services supplied through one of these modes. Where measures affect more than one mode of supply it is labelled as affecting all modes. Such measures include regulations that affect competition in the market and measures related to regulatory transparency.

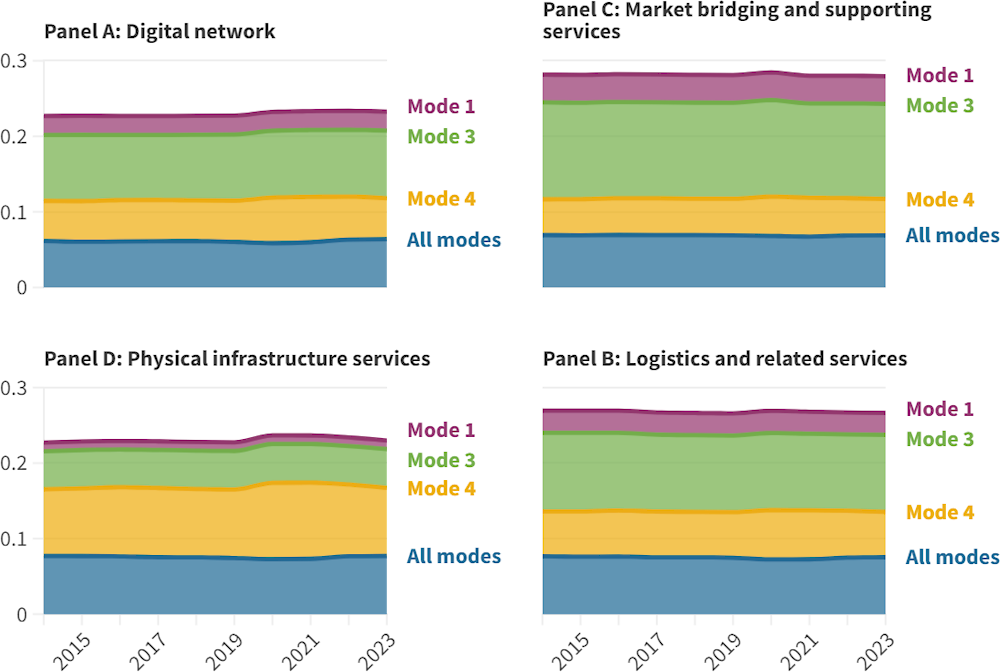

The STRIs by modes of supply are shown in Figure 2.26, aggregated across the four main services clusters and showing developments observed for the period between 2014 and 2023. Measured across all 22 sectors, barriers to mode 3 are the highest, accounting for close to 40% of all restrictions identified. Such barriers are particularly prominent in market bridging services such as financial services. This is also the case for some professional services included in this cluster (legal and auditing services), although for these services, barriers to mode 4 are generally an important contributor. Moreover, in digital network services, mode 3 barriers are more than three times higher than mode 1 barriers and have increased moderately over the years. This highlights that firms providing digitally enabled services can face headwinds when attempting to access new markets by establishing a commercial presence.

Figure 2.26. Barriers to services supplied through commercial presence (mode 3) are contributing the most to global services trade restrictiveness

Average of the STRI broken down by modes of supply across different clusters of services, 2014-2023

Note: The sectors covered in the STRI can be broadly organised around four clusters: 1. Digital network services (telecommunications, computer services, broadcasting, motion pictures and sound recording); 2. Logistics and related services (transport, courier, logistics and distribution services); 3. Market bridging and support services cluster (commercial banking, insurance, accounting and legal services); and 4. Physical infrastructure services cluster (construction, architecture and engineering). For more details, see Box 2.2. Access the interactive version of the graph: https://public.flourish.studio/visualisation/18246099/

Source: OECD STRI (2024).

Barriers to mode 4 supplies tend to be higher in sectors where services are mostly provided by regulated professionals. In physical infrastructure services, foreign engineers and architects are generally subject to tighter licensing conditions and fewer recognition of foreign qualifications, making services deliveries more difficult. In terms of trends across sectors, barriers to mode 4 generally increased in 2020 due to government responses to the COVID-19 pandemic but were rebalanced by 2023. Substantial liberalisation across countries is far from a reality, however, making mode 4 supplies difficult across countries.

Notes

← 1. Note that globally there are over 100 data localisation measures in force in 2023. See Del Giovane, Ferencz and López González (2023[11]).

← 2. In addition to OECD countries, the Digital STRI covers 23 African countries (with additional countries currently in the process of being added), 22 Asia-Pacific countries, 14 Latin American countries, and 6 South-East European countries.

← 3. Prudential regulation of financial services is necessary to maintain the stability and soundness of the financial system. The STRI is not designed to determine which measures are considered prudential or necessary, but to objectively in a comparable manner the legal and regulatory impediments faced by foreign financial services suppliers.

← 4. For the WTO definitions of the different modes of services supply, see https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/serv_e/cbt_course_e/c1s3p1_e.htm