Sandrine Cazes, Sebastien Martin and Andrea Salvatori

OECD Employment Outlook 2024: The Net-Zero Transition and the Labour Market

1. Steady as we go: Treading the tightrope of wage recovery as labour markets remain resilient

Abstract

This chapter provides an overview of recent labour market developments, with a focus on wage dynamics. The resilience of OECD labour markets is analysed, focussing especially on the evolution of labour market tightness and gender gaps. Real wage growth, including at the minimum wage, is also examined and compared with the dynamics of profits, to investigate whether the latter have started to buffer some of the increases in labour costs as wages recover their purchasing power. Beyond wages, the chapter also provides an update of the three key indicators of the OECD job quality framework across countries.

In Brief

Labour markets have proven resilient in the wake of adverse shocks and continued to perform strongly, with many countries seeing historically high levels of employment and low levels of unemployment. Amidst tight labour market conditions and a decline in inflation, real wages are now growing on an annual basis in many countries, although they are below their 2019 levels in about half of them.

The latest available evidence at the time of writing suggests:

Employment growth has flattened, and unemployment remains at historically low levels in most countries. In May 2024, total employment was 3.8% higher than before the COVID‑19 crisis, while the OECD unemployment rate was at 4.9%, after a record low of 4.8% in September 2023. Global GDP growth is projected to remain unchanged in 2024 from 2023 and strengthen modestly only in 2025, with inflation returning to target in most countries by the end of 2025. The OECD-wide unemployment rate is projected to rise marginally over 2024‑25, with employment growth expected to slow over the same period.

Labour force participation rates continued to increase in the OECD and reached a record high. In Q1 2024, participation rates were 1.3 percentage points higher than at the end of 2019 on average across the OECD, with more than half of that increase occurring since early 2022.The increase affected all age groups, with older workers (aged 55 to 64) experiencing the highest increase. The OECD labour force participation rate reached 73.9% in Q1 2024 – the highest level since the series began in 2005. Record levels were reached for both men and women.

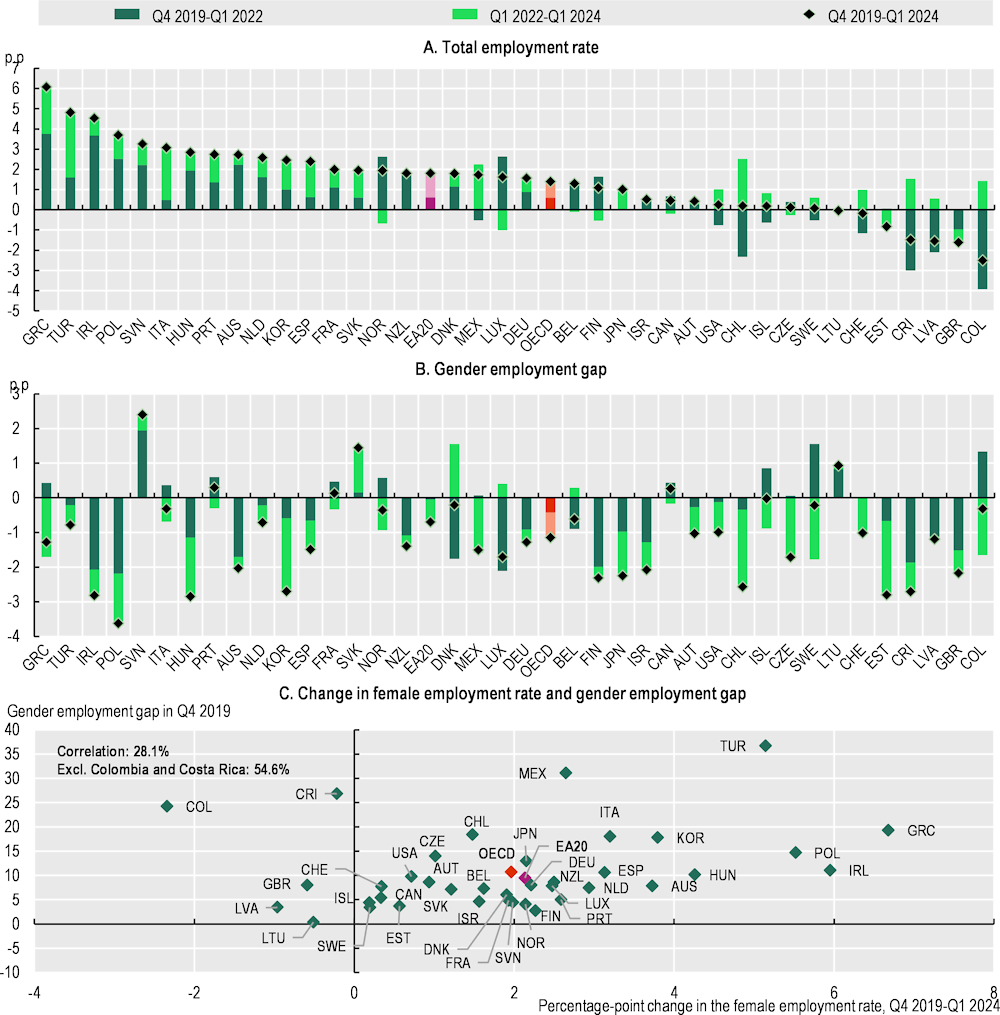

Gender gaps in employment rates and labour force participation are narrowing in many OECD countries since 2019. In most OECD countries, the rise in the female employment rate in the four years to Q1 2024 outperformed that of men. Gender differences in the change in unemployment rates were generally small over the same period.

Labour market tightness is easing but remains generally high. In Q4 2023, vacancy-to‑unemployed ratios were below their peak in all countries where they increased significantly in the wake of the COVID‑19 crisis. While low-pay industries played a significant role in driving the growth of overall imbalances in the past, latest data suggest that this no longer the case. Tensions remain however particularly high in the health sector.

Real wages are now growing on an annual basis in many OECD countries but remain below 2019 levels in about half of them. In Q1 2024, yearly real wage growth was positive in 29 of the 35 countries for which data are available, with an average change across all countries of +3.5%. However, in Q1 2024, real wages were still below their Q4 2019 level in 16 of the 35 countries.

Statutory minimum wages are above their 2019 level in real terms in virtually all countries. In May 2024, thanks to significant nominal increases in statutory minimum wages to support the lowest paid during the cost-of-living crisis, the real minimum wage was 12.8% higher than in May 2019 on average across the 30 OECD countries that have a national statutory minimum wage. The median increase, which is used because the average figure is affected by the particularly large increases in some countries, was at 8.3%. Both figures are quite significant compared to the increase in average/median wages.

Wages of low-pay workers have performed relatively better in many countries. In 17 of the 33 countries with available data, real wages performed relatively better in low-pay industries than in both mid- and high-pay industries between 2019 and 2023. Results by education and occupation from selected countries also point to better performance of wages for the lower-paid groups.

While wages are recovering, unit profits growth has slowed down and turned negative in some countries. After growing considerably and making unusually large contributions to domestic price pressures in 2021 and 2022, unit profits decreased in 14 of the 29 countries with available data over the last year – an indication that they have started to absorb some of the inflationary impact of increasing unit labour costs. In most countries, there is further room for profits to provide some buffering, given their significant growth over the past three years.

A special emphasis is placed in this chapter on job quality in OECD countries, as other aspects of jobs, beyond wages, need to be monitored to assess what has happened to workers’ overall well-being following the COVID‑19 pandemic and the recent cost-of-living crisis.

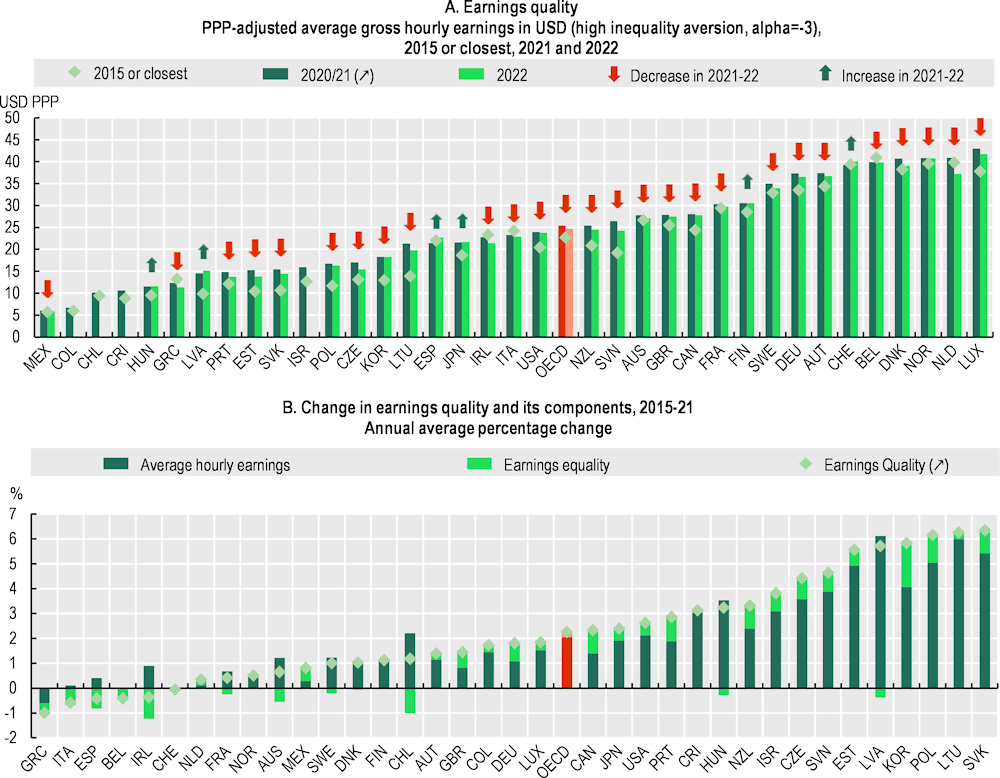

Earnings quality, one of the three key indicators of the OECD Job Quality framework, was generally better across the OECD in 2022 than in 2015. Yet, data for 2022 show that, because of the acceleration in inflation and slow wage adjustment, earnings quality decreased between 2021 and 2022 in 26 of the 32 countries for which data are available. Earnings quality measures the extent to which the earnings received by workers contribute to their well-being, by taking account of the average level of earnings and the way earnings are distributed across the workforce.

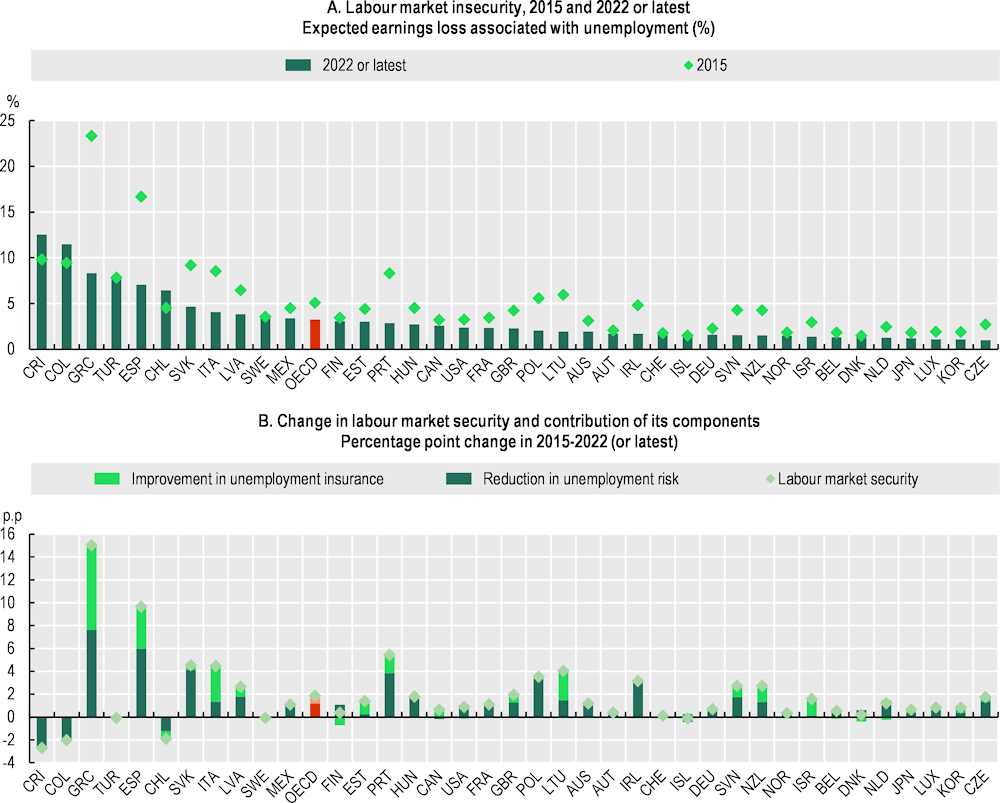

Labour market security (which measures the extent to which public income support for the unemployed mitigates the expected earnings loss associated with unemployment) generally improved across the OECD between 2015 and 2022. This positive pattern was driven by a decline in unemployment rates and improvements in unemployment insurance since 2015.

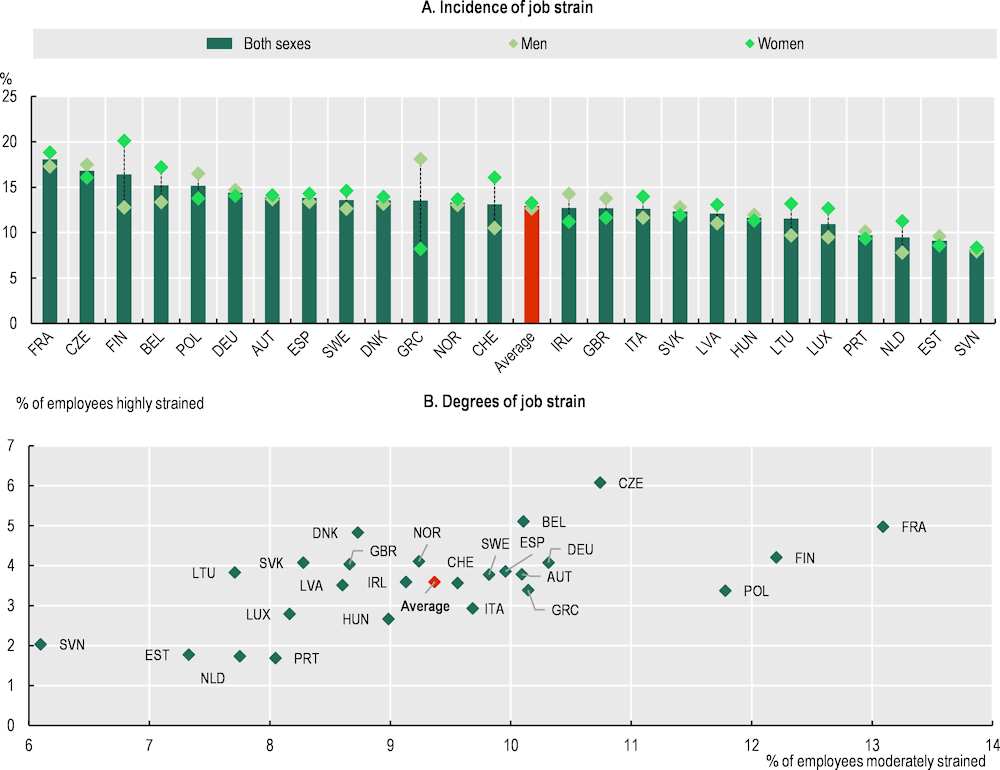

The quality of the working environment, the third key indicator of job quality, is measured by job strain, a situation where workers have insufficient job resources to meet job demands. Results are only available for 2021, when some 13% of workers experienced job strain on average for the 25 OECD European countries for which data are available.

Looking ahead, it will continue to be important to strike a balance between allowing wages to make up some of the ground they have lost in terms of purchasing power and limiting further inflationary pressures. The most recent data are reassuring as they do not show signs of further acceleration in nominal wage growth, with some indicators even suggesting that it has slowed down. Some firms will find it more difficult to absorb further wage increases than others, with small and medium-sized firms likely to face greater constraints than large companies. Collective bargaining and social dialogue, when well-designed and implemented, can help identify solutions tailored to sectors and firms’ different abilities to sustain further increase in wages and to promote policies and practices to enhance the growth in productivity needed to sustain real wage gains in the longer term.

Introduction

The last few years have been tumultuous, with significant negative shocks hitting the global economy in the aftermath of the COVID‑19 crisis. Yet, labour markets in OECD countries have proven resilient, even when living standards came under intense pressure as inflation reached levels not seen in decades in many countries. This chapter reports on the latest developments in labour market indicators across the OECD and provides an update on the impact of the cost-of-living crisis on wages, leveraging a range of diverse national data sources.

Non-wage aspects of jobs also need to be monitored to understand trends in job quality in the wake of the COVID‑19 pandemic and the recent cost-of-living crisis. Drawing on the conceptual framework developed by the OECD (Cazes, Hijzen and Saint-Martin, 2015[1]; OECD, 2014[2]) and then adopted by the G20 (G20, 2015[3]), the chapter also provides an update on the three key indicators of job quality across countries – earnings quality, labour market security and quality of the working environment.

The chapter is organised as follows: Section 1.1 reviews recent labour market developments across the OECD countries; Section 1.2 reports on recent wage developments, including an update on statutory minimum wages and negotiated wages; and finally, Section 1.3 presents the latest OECD job quality indicators and analyses trends in these indicators since 2015. Section 1.4 concludes with policy recommendations.

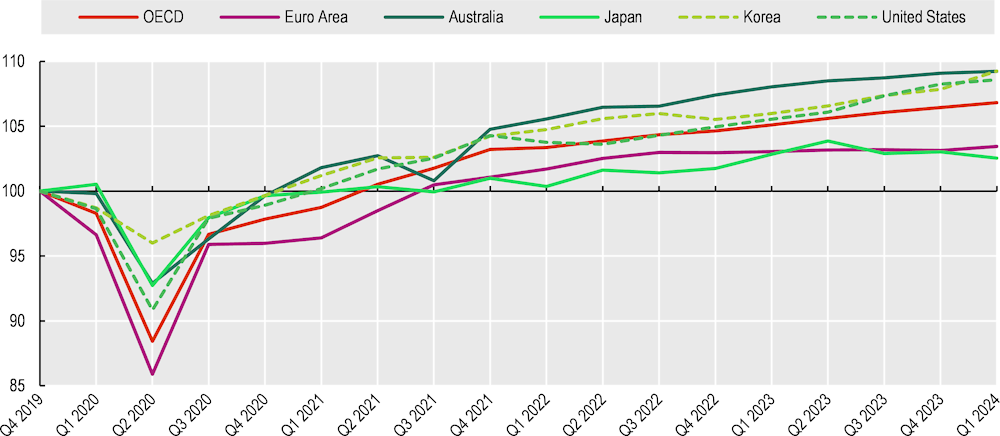

1.1. Labour markets have proven resilient in the wake of adverse shocks

Global GDP growth has been moderate, but relatively resilient in 2023 despite the negative shocks from Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine and the sharp tightening of monetary policy to tackle high inflation. Growth was particularly strong in the United States and many emerging-market economies but saw a slowdown in most European countries (Figure 1.1). The attacks on ships in the Red Sea that started in Fall 2023, have raised shipping costs sharply and lengthened delivery times, disrupting production schedules and raising price pressures. According to the latest indicators, global GDP growth is projected to continue growing at a modest pace of 3.1% in 2024, the same growth as the 3.1% in 2023, followed by a slight pick-up to 3.2% in 2025 as financial conditions ease (OECD, 2024[4]).

Figure 1.1. GDP growth has been moderate with significant divergence between countries

Real GDP indexed to 100 in Q4 2019 in selected OECD countries, seasonally adjusted data

Note: Euro Area refers to the 20 Eurozone countries.

Source: OECD (2024), “Quarterly National Accounts”, OECD National Accounts Statistics (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/data-00017-en (accessed on 12 June 2024).

1.1.1. Employment growth has flattened and unemployment remains at historically low levels in most countries

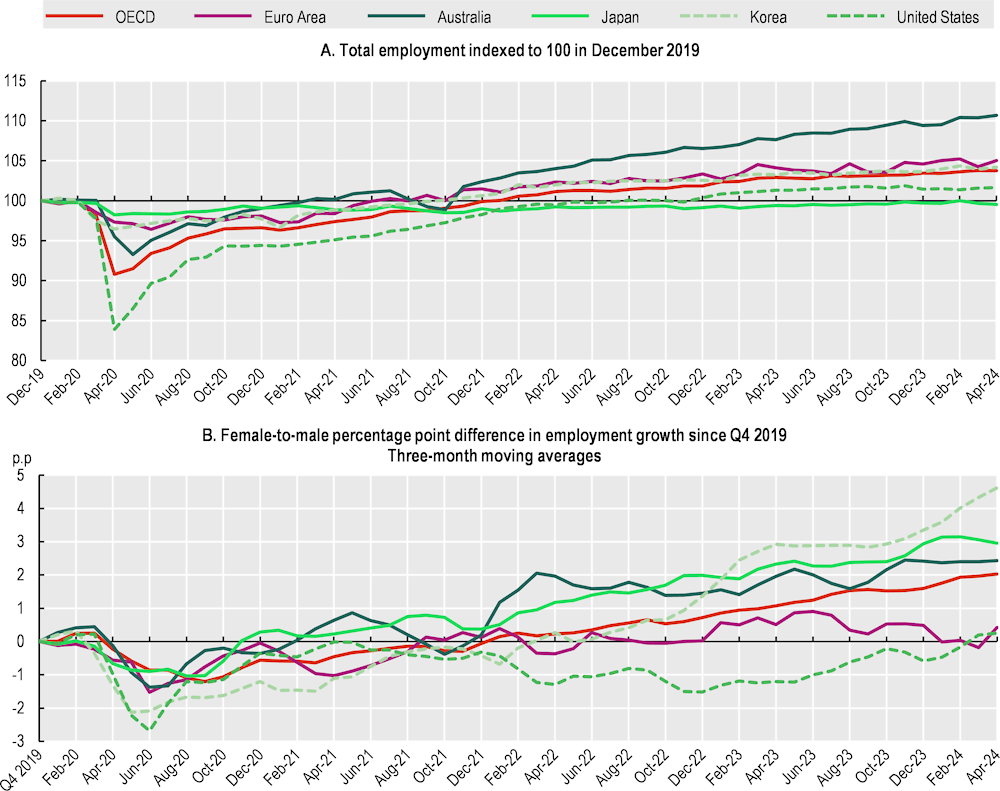

Employment growth for the OECD area flattened over the course of 2023 and early months of 2024, with total employment reaching a level 3.8% higher than before the COVID‑19 crisis by May 2024 (Panel A of Figure 1.2). While remaining positive year on year, total employment growth slowed down in all major OECD economies in recent months. Across the OECD, employment grew more for women than for men continuing a trend seen throughout the recovery from the COVID‑19 crisis. By May 2024, on average across the OECD, women’s total employment had grown about 2 percentage point more than men’s, reaching 5.3% above its pre‑crisis level. Women’s employment performed particularly well in Australia, Japan, and Korea (Panel B of Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2. Total employment stabilised in 2023 in the OECD

Series seasonally adjusted data, selected OECD countries

Reading: Panel B shows the difference in the growth rate of total employment between men and women since Q4 2019. By May 2024, on average across the OECD, women’s total employment had grown about 2 percentage points more than men’s, reaching 5.3% above its pre‑crisis level.

Note: Euro Area refers to the 20 Eurozone countries. The OECD average and the Euro Area are derived from the OECD Monthly Unemployment Statistics estimated as the unemployment level times one minus the unemployment rate and rescaled on the LFS-based quarterly employment figures.

Source: OECD (2024), “Labour: Labour market statistics”, Main Economic Indicators (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/data-00046-en (accessed on 9 July 2024).

As for employment rates, they progressed more for women than for men in most OECD countries compared to pre‑pandemic level, indicating that gender gaps in employment rates are narrowing in many OECD countries. Interestingly, data suggest that the higher the employment gender gap in Q4 2019, the greater was the growth in women’s employment rate between Q4 2019 and Q1 2024 (Annex Figure 1.A.1).

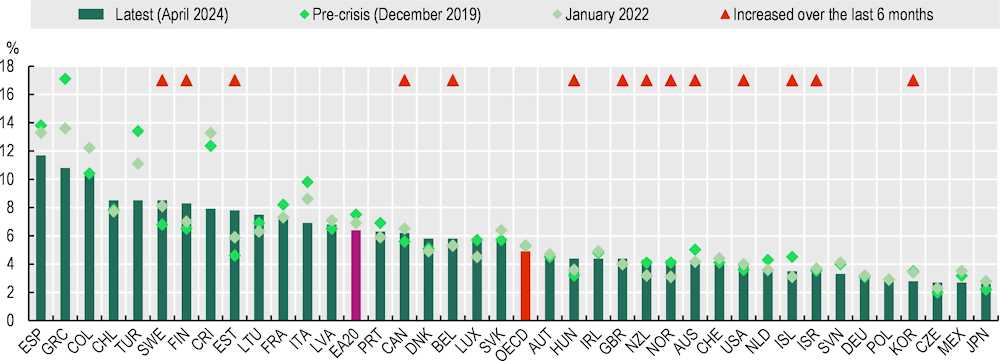

Unemployment rates remain at historically low levels in many OECD countries (Figure 1.3). The unemployment rate for the OECD was already at its pre‑COVID‑19 level in January 2022 – before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Since then, the unemployment rate declined by a further 0.4 percentage points and stood at 4.9% in May 2024 after a record low of 4.8% in September 2023. Unemployment rates are below their levels of January 2022 in 17 OECD countries, and above that level by more than 0.5 percentage points in 10 countries.

The most recent data also suggest stable unemployment rates across countries, with only 13 OECD countries having experienced an increase of more than a quarter of a percentage point over the past six months. Gender differences in the changes in unemployment rates between December 2019 and May 2024 are generally small: while not shown here, the gender gap in unemployment rates was rather stable on average for the OECD area except for Colombia, Costa Rica and Greece where it decreased by more than 2 percentage points.

Figure 1.3. Unemployment rates remain at historically low levels in many countries

Unemployment rate (percentage of labour force), seasonally adjusted data

Note: The labour force population includes all those aged 15 or more. Euro Area refers to the 20 Eurozone countries. The labour force population includes all those aged 15 or more. The latest month refers to Q1 2024 for New Zealand and Switzerland; February 2024 for Iceland, March 2024 for the United Kingdom; April 2024 for Chile, Costa Rica and Türkiye; and June 2024 for Canada and the United States.

Source: OECD (2024), “Unemployment rate” (indicator), https://doi.org/10.1787/52570002-en (accessed on 9 July 2024).

1.1.2. Labour force participation rates continue to increase while average hours worked are slightly below their pre‑COVID‑19 levels in several countries

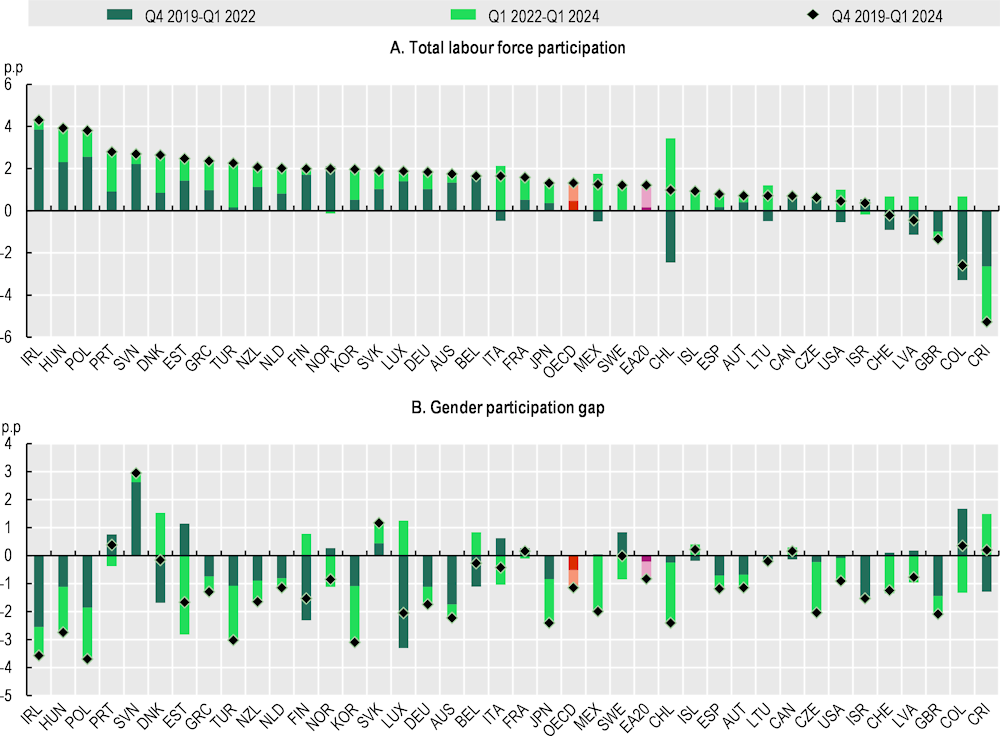

Labour force participation rates among the working age population have continued to increase in most of the OECD countries over the past year or so1 (Figure 1.4, Panel A). In Q1 2024, labour force participation rates were 1.3 percentage points higher than at the end of 2019 on average across the OECD. More than half of that increase occurred since the first quarter of 2022 as 32 of the 38 OECD countries continued to see their participation rates increase. Colombia, Costa Rica and the United Kingdom are the only three OECD countries where the labour force participation rate is below its pre‑COVID‑19 level by more than a percentage point. Within the working age population (aged 15‑64), labour force participation rates have increased for all age groups, with older workers (aged 55 to 64) experiencing the largest increase on average across the OECD (1.9 percentage points since early 2022, for a total of 3.5 percentage points since the start of the COVID‑19 crisis).2

Similarly to employment rates, labour force participation rates progressed more for women than for men compared to pre‑pandemic level, so the gender gaps in participation rates narrowed in almost all OECD countries by 1.1 percentage point between Q4 2019 and Q1 2024 for the OECD area (Figure 1.4, Panel B).

Figure 1.4. Labour force participation rates have continued to increase over the past year

Percentage point change in labour force participation rates (persons aged 15‑64), seasonally adjusted data

Note: The gender participation gap is defined as the male‑to-female difference in the labour force participation rates. OECD is the unweighted average of the 38 OECD countries shown in this chart. Euro Area refers to the 20 Eurozone countries. p.p: percentage point. Countries are ordered by descending order of the percentage point change in labour force participation rates in Q4 2019‑Q1 2024 (Panel A).

Source: OECD (2024), “Labour: Labour market statistics”, Main Economic Indicators (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/data-00046-en (accessed on 25 June 2024).

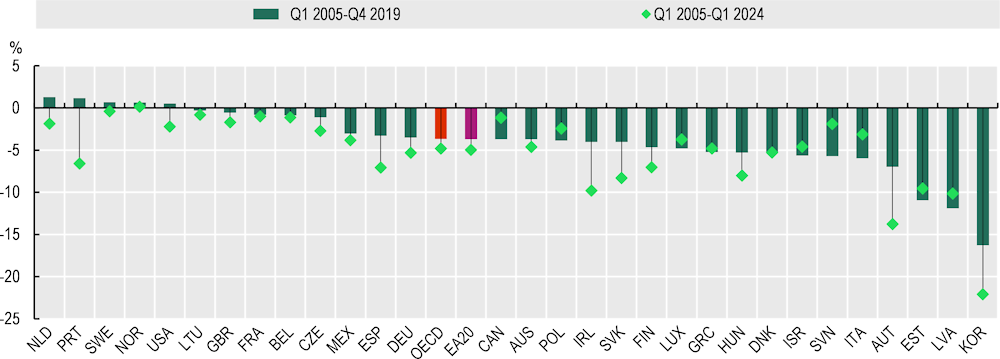

In Q1 2024, hours worked per employed person were below their pre‑COVID‑19 levels in 20 of the 31 countries with recent data available (Figure 1.5). The average decline in hours worked since Q4 2019 across all countries with available data is rather small – just above 1%.3 In most countries, this decline follows a trend that pre‑dates the COVID‑19 crisis, though with some notable accelerations in Austria, Finland, Hungary, Ireland, Korea, the Slovak Republic and Spain. Among the five countries where hours worked had been increasing before the COVID‑19 crisis, only the Netherlands, Portugal and the United States, saw a decline of more than 1% in the aftermath of the pandemic.

Evidence for Europe indicates that the decline in hours worked over the past 20 years is largely driven by an increase in part-time and a reduction in hours within jobs (as opposed to a compositional shift to jobs typically requiring fewer hours) (Astinova et al., 2024[5]; ECB, 2021[6]). However, the decline in average hours worked since the COVID‑19 crisis has not been associated with widespread up-ticks in part-time employment. On the contrary, annual data for 2022 point to a slight decrease in the incidence of part-time in most OECD countries relative to 2019.4

Overall, the cross-country comparison does not lend support to the hypothesis of a generalised post-COVID change in preferences over work-life balance that might have reduced willingness to work, but more evidence is needed to understand patterns observed in specific countries.

Figure 1.5. The post-pandemic decline in average hours worked per worker is generally consistent with long-term trends

Percentage change, seasonally adjusted data

Note: Average hours worked per worker is defined as the total hours worked divided by total employment, except for Belgium where it refers to the average hours worked of employees, Korea, where it refers to the average usual weekly hours worked per employed, New Zealand, where it is defined as the total paid hours divided by filled jobs, and the United States where it refers to the average usual weekly hours worked per wage and salary workers. Statistics are not seasonally adjusted for Canada and Mexico and periods reported for those countries refer to Q4 2004‑Q4 2019 and Q4 2004‑Q4 2023, and Q4 2005‑Q4 2019 and Q4 2005‑Q4 2023, respectively. The latest quarter available refers to Q3 2023 for Israel, and to Q4 2023 for Belgium and the United Kingdom. OECD is an unweighted average of the 31 OECD countries shown in this Chart (not including Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Iceland, Japan, Switzerland and Türkiye). Euro Area refers to the 20 Eurozone countries.

Source: OECD (2024), “Quarterly National Accounts”, OECD National Accounts Statistics (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/data-00017-en (accessed on 21 June 2024) for all countries except Australia, Korea, New Zealand, and the United States; Australian Labour Account (Australian Bureau of Statistics) for Australia, Economically Active Population Survey (Statistics Korea) for Korea, Quarterly Employment Survey (QES – Tables QEM034AA and QEM025AA, Stats NZ) for New Zealand, and Current Population Survey (CPS, Bureau of Labor Statistics) for the United States.

For the United States, evidence suggests that people’s willingness to work did decline significantly during the pandemic, as potential hours worked (i.e. a measure of hours people are willing to work) declined much more than the overall participation rate – an anomaly relative to other recessions. However, by mid‑2022 potential hours worked began to increase more quickly than labour force participation suggesting that the impact of the pandemic – while prolonged – might have only been temporary (Bognar et al., 2023[7]). Similarly, it is too early to establish whether the increase in sick leave that took place in Europe after the pandemic can be seen as a permanent change (Arce et al., 2023[8]). On the demand side, labour hoarding by firms might have contributed to keeping average hours down in the last year or so as, faced with a slowdown in activity in some countries, firms might have preferred reducing hours to laying-off workers due to the expected difficulties in re‑hiring workers (see Section 1.1.3).

1.1.3. Labour market tightness is easing but remains generally elevated

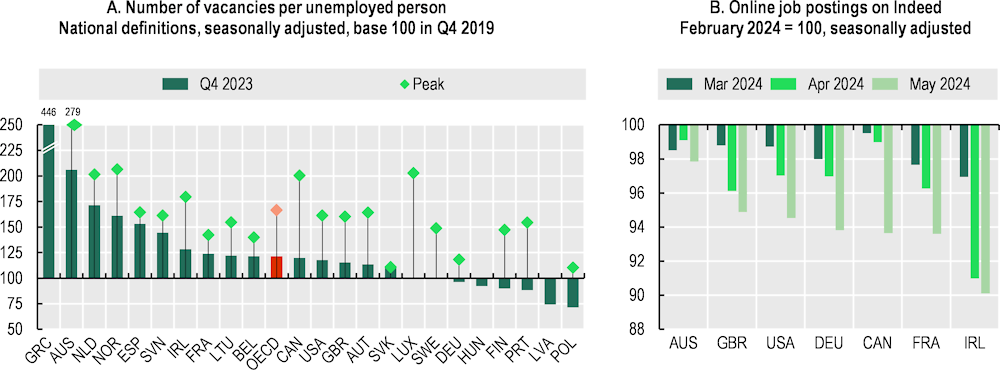

Amid the general slowdown in economic growth, labour market tightness (i.e. the number of vacancies per unemployed person) has eased in recent quarters but remains above pre‑COVID‑19 levels in many countries (Figure 1.6, Panel A). In Q4 2023, among the countries with available data, vacancy-to‑unemployed ratios were below their peak in all countries where they had increased considerably after the COVID‑19 crisis.

This picture drawing on vacancy-to‑unemployment ratios5 is completed with data on job postings to get information on the latest developments of labour demand: data on the online platform Indeed confirm a continued easing over the last months (Figure 1.6, Panel B). In May 2024, online job postings were below their February 2024 level in all seven countries with data available.

Imbalances between demand and supply have been widespread across industries. While low-pay industries played a significant role in driving the growth of overall imbalances in the past (OECD, 2023[9]), the latest data suggest that this is no longer the case. The visualisation, for 26 OECD countries with available data, of the increase in vacancy rates in each industry relative to the change at the country level shows indeed that the distribution of the red squares (i.e. sectors with high increases in vacancy rates relative to the country average) are not concentrated among low-pay industries anymore (Annex Figure 1.A.2). Tensions remain however particularly high in the health sector – which is the only one with higher-than-average increases in vacancy rates in over two thirds of the countries with data available (as shown in the far right column in Annex Figure 1.A.2).

Tight labour markets can push employers to offer better job packages, such as stable jobs or with a set of benefits (OECD, 2023[9]), but also to adjust wages, as evidenced by the pick-up in nominal wage growth over the past year or so (Section 1.2). They can also stimulate the participation of groups with lower labour market attachment. Moreover, lasting labour shortages may create incentives for firms to invest in technology and automation, which can have positive effects on productivity and wages. At the same time, labour shortages can also lower production and its quality, hinder innovation, and adoption of advanced technologies – at least if they concern high skill workers – and provide incentives for outsourcing and offshoring that are hard to reverse.

Figure 1.6. Labour markets remain tight in many countries even as pressure is easing

Note: OECD is the unweighted average of the 23 OECD countries shown in Panel A of this chart (not including Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, Iceland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Korea, Mexico, New Zealand, Switzerland and Türkiye). The peak (Panel A) refers to the maximum value of the number of vacancies per unemployed reached in Q4 2019‑Q4 2023. For Hungary and Latvia, the number of vacancies per unemployed remains always below its Q4 2019 level and consequently there is no peak during the period considered. For Greece, the peak refers to Q4 2023.

In Panel A, statistics refer to the number of vacancies (see description below) divided by the number of unemployed (ILO definition). The definition of vacancies is not harmonised across countries. For European countries (except Austria, France, Germany, Hungary and Portugal – see below), a vacancy is defined as a paid post that is newly created, unoccupied, or about to become vacant for which the employer is taking active steps and is prepared to take further steps to find a suitable candidate from outside the enterprise concerned; and which the employer intends to fill either immediately or within a specific period. For Australia, a vacancy is defined as a job available for immediate filling and for which recruitment action has been taken by the employer. For Austria, a vacancy is defined as a job notified by firms to employment agencies which remain unfilled at the end of the month. For Canada, a vacancy is defined as a job meeting the following conditions: it is vacant on the reference date (first day of the month) or will become vacant during the month; there are tasks to be carried out during the month for the job in question; and the employer is actively seeking a worker outside the organisation to fill the job. The jobs could be full-time, part-time, permanent, temporary, casual, or seasonal. Jobs reserved for subcontractors, external consultants, or other workers who are not considered employees, are excluded. For France, a vacancy is defined as the monthly number of vacancies posted by companies in France Travail. For Germany, a vacancy is defined as a job of seven days’ duration or more reported by employers to employment agencies to be filled within 3 months and remaining unfilled at the end of the month. For Hungary, a vacancy is defined as the number of vacancies notified to local labour offices as part of the central government territorial administrative unites. For Portugal, a vacancy is defined as the number of vacancies reported by employers to be still vacant at the last month of the quarter. For the United Kingdom, a vacancy is defined as a position for which employers are actively seeking recruits from outside their business or organisation (excluding agriculture, forestry, and fishing) based on the estimates from the Vacancy Survey. For the United States, a vacancy is defined as a job that is not filled on the last business day of the month and a job is considered open if a specific position exists and there is work available for it, the job can be started within 30 days, and there is active recruiting for the position.

In Panel B, online job postings on Indeed are indexed to 100 in January 2024.

Source: OECD (2024), “Labour: Registered unemployed and job vacancies (Edition 2023)”, Main Economic Indicators (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/cee89a15-en (accessed on 29 May 2024) for Australia, Austria, Germany, Hungary, Portugal and the United Kingdom; Eurostat, Job vacancy statistics by NACE Rev.2 activity (Table jvs_q_nace2) for Belgium, Finland, Greece, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain and Sweden, Job vacancies, payroll employees, and job vacancy rate (Statistics Canada) for Canada, Les demandeurs d’emploi inscrits à France Travail (DARES) for France; Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (Bureau of Labor Statistics, retrieved from FRED) for the United States; Indeed, Online Job Posting Tracker, https://github.com/hiring-lab/job_postings_tracker (accessed on 12 June 2024).

Hence, addressing labour shortages requires unpacking the many and interconnected factors behind them − and whether they differ from pre‑COVID labour markets. For instance, the working conditions in some segments of the health sector – such as the long-term care one – have received considerable attention in the wake of the pandemic with a renewed interest in policy solutions to improve the quality of jobs that are already facing significant recruitment difficulties and are expecting further growth in demand as a result of population ageing (OECD, 2023[9]). Box 1.1 presents some possible factors behind labour shortages.

Overall, a comprehensive multifaceted policy approach is needed to address labour shortages and the complex and interrelated factors driving them, stimulating labour supply among groups with lower participation rates, improving the working conditions of certain sectors and the skill and geographical match between labour demand and supply, as well as the efficiency of the matching process when there are workers with the right skills in the right place.

Box 1.1. Labour shortages in the post-COVID‑19 era: Are they different?

Labour shortages have been a distinctive feature of post-COVID labour markets. While shortages initially appeared in sectors that were more heavily affected by the pandemic, they seem to have since spread to broad swathes of the labour force. Labour shortages are driven by a number of structural and cyclical interrelated factors. In several sectors (mostly high-skill ones) and countries, labour shortages had been steadily increasing well before the COVID‑19 pandemic − at least since the Global Financial Crisis.

Factors driving shortages in the long term include demographic trends shaping the size and composition of the labour force; geographical and skill mismatches between labour demand and supply which can be exacerbated by the diffusion of AI and the digital and green transitions (see also Chapter 2); changes in workers’ preferences concerning job quality and working conditions; and the efficiency of the matching process between labour demand and supply.

The significant increase in labour shortages in the post-COVID labour markets – especially in the low skilled, low pay sectors in the first years – appeared to be linked mostly to the surge in labour demand to catch-up after the COVID‑19 crisis. While there is no indication of new significant mismatches induced by the recent crisis (Duval et al., 2022[10]), the rapid increase in labour market tightness might have contributed to a self-reinforcing mechanism whereby a strong labour market encourages workers to quit their jobs and leads to further vacancies being opened (Bognar et al., 2023[7]).

By contrast, there is little indication on the impact of labour supply changes on the rise of labour shortages: as reported in Section 1.1.2, labour force participation rates have increased for all age groups and the overall size of the labour force generally continues to grow. It is however possible that there might be changes in workers’ preferences over different types of jobs, as well as changes in the composition of the workforce, with young workers not necessarily being willing to perform some of the jobs left by those who have retired.

The OECD webinar “Labour Shortages, today and tomorrow” organised on 18 March 2024 discussed labour shortages patterns across OECD countries. One important insight was the significant differences in the short-term patterns across the United States, the United Kingdom and Germany 1. In the first two countries, workers seemed to have moved away from certain sectors with low pay and strenuous conditions, such as retail trade, food and hospitality and manufacturing, which led to important workers’ turnover. Further indication for the United Kingdom suggests indeed that workers might have directed their search away from sectors that were badly hit during the COVID‑19 crisis 2. In Germany, such reallocation did not occur. As labour market tightness remains elevated in many OECD countries, more evidence will be needed about these patterns: further research will be typically important to understand the nature of ongoing workers turnover and identify the factors influencing mobility across jobs, notably those that might hinder flows towards occupations and sectors facing labour shortages.

1. This draws on the panel discussion of the first session of the OECD webinar “Workers, wherefore art thou? Labour shortages, today and tomorrow”, organised on 18 March 2024, as part of the Working Party on Employment Webinar Series, with the respective presentations by Nick Bunker, Director of North American Economic Research, Indeed, “Labour Demand and posted wage growth in the United States”, Carlos Carillo-Tudela, Professor of economics at the University of Essex in the United Kingdom, “Job search and sectoral shortages in the United Kingdom” and Bernd Fitzenberger, Director of the IAB and Professor of Quantitative Labor Economics at Friedrich-Alexander -Universität-Erlangen-Nurnberg in Germany “Labour shortages in Germany”.

1.1.4. Economic growth in the OECD is expected to remain unchanged in 2024 and strengthens modestly in 2025, with marginal increase in unemployment and slowdown of employment growth

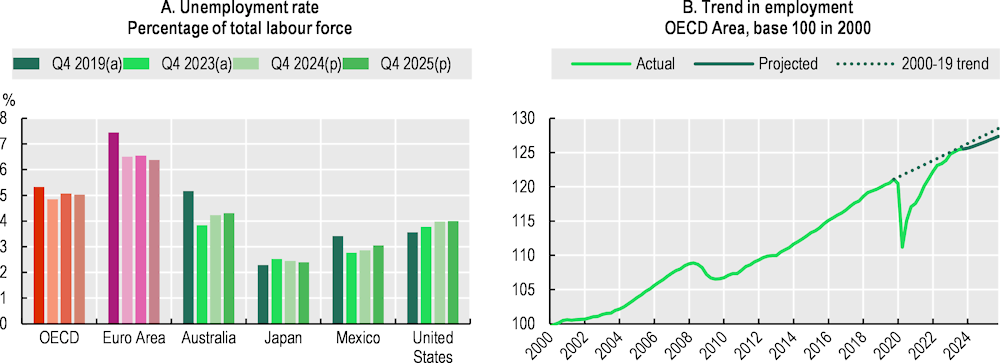

Global growth, which slowed in the second half of 2023, is expected to stabilise and then pick up slightly through 2024‑25. In part, this reflects better momentum than expected in the United States and some emerging-market economies. Annual OECD GDP growth is projected to be at 1.7% in 2024 and edge up to 1.8% in 2025 (OECD, 2024[4]).

The OECD-wide average unemployment rate is projected to rise marginally over 2024‑25 to 5% in the fourth quarter of 2025 (Figure 1.7). The OECD-wide employment growth is expected to slow from 1.7% in 2023 to around 0.7% per annum on average over 2024‑25, below its 2000‑19 trend (Figure 1.7).

Figure 1.7. Employment in the OECD is projected to continue to grow in 2024 and 2025, with the unemployment rate also inching up slightly

Note: (a) Actual value. (p) OECD projection. Euro Area refers to the 17 EU member states using the euro as their currency which are also OECD Member States. The 2000‑19 trend refers to the average quarterly employment growth rate prevailing in Q1 2000 to Q4 2019.

Source: OECD (2024[4]), OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2024 Issue 1: Preliminary version, https://doi.org/10.1787/69a0c310-en.

Significant uncertainty remains, however. Inflation may stay higher for longer, resulting in slower-than- expected reductions in interest rates and leading to further financial vulnerabilities. Growth could be disappointing in China, due to the persistent weakness of property markets or smaller than-anticipated fiscal support over the next two years. Another key downside risk to the outlook relates to the high geopolitical tensions, notably the uncertain course of Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, the evolving conflict in the Middle East, and the associated risks of renewed disruptions in global energy and food markets. On the upside, demand growth could prove stronger than expected, if households and firms were to draw more fully on the savings accumulated during COVID‑19 (OECD, 2024[4]).

1.2. Real wages are now growing in a number of countries but often remain below 2019 levels

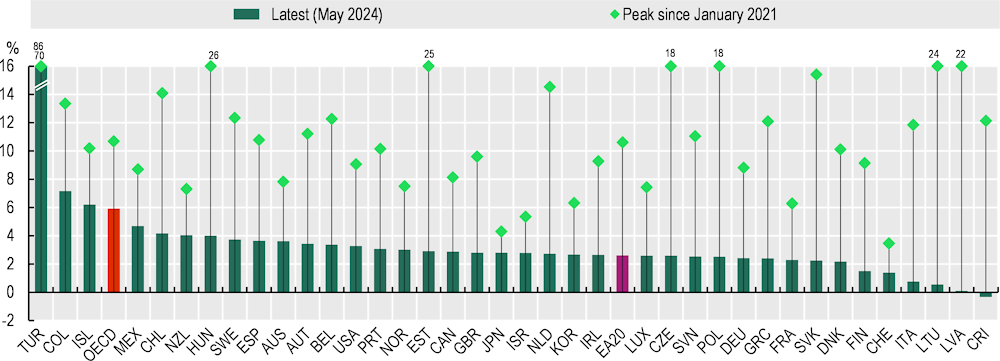

Headline inflation has fallen virtually everywhere primarily because of the partial reversal of the very large rise in energy prices over the previous two years and is expected to further ease.6 After peaking at over 10.7% in October 2022, OECD inflation almost halved reaching 5.9% in May 2024. However, inflation remained above the 2% target of central bank for 31 OECD countries – above 8% in Türkiye, and above 4% in five other OECD countries (Figure 1.8).

Figure 1.8. Inflation remains high but has declined significantly since the peak of 2022

Inflation defined as annual percentage change in the consumer price index (CPI), May 2024

Note: For Australia and New Zealand, statistics refer to year-on-year changes in Q1 2024. Values on top refer to peaks of inflation above 16%. Euro Area refers to the 20 Eurozone countries.

Source: OECD (2024), “Prices: Consumer prices”, Main Economic Indicators (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/0f2e8000-en (accessed on 02 July 2024).

1.2.1. Real wages are now growing year-on-year, but they remain below 2019 levels in many countries

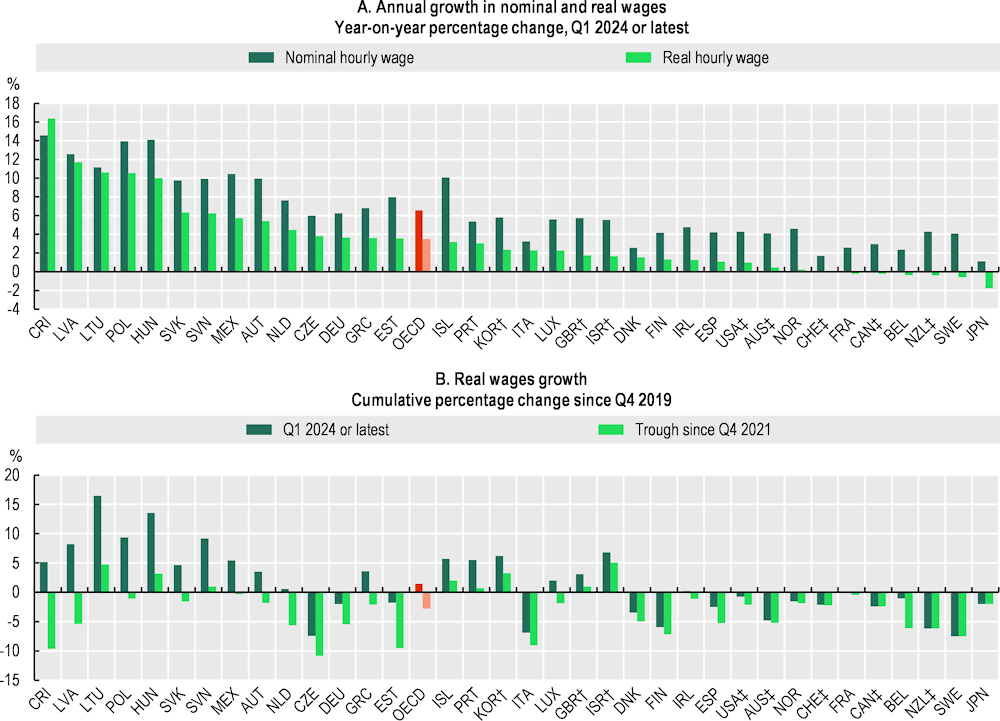

Year-on-year real wage growth turned positive in an increasing number of countries over the last year, as inflation declined and nominal wage growth picked up.7 According to the latest data for Q1 2024, yearly real wage growth was positive in 29 of the 35 countries with available data, with an average change across all countries of +3.5%. In Belgium, Canada, France, Japan, New Zealand and Sweden, the annual real wage growth was still negative in Q4 2024 but relatively moderate – with real wages decreasing less than 1% over the year except for Japan8 (Figure 1.9, Panel A).

Data on selected countries for different wage indicators and posted wages in online vacancies suggest that real wage growth has continued to improve in the first months of 2024. This is generally the result of moderating inflation while nominal wage growth has remained stable with some indication of a possible deceleration in posted wages (Box 1.2).

Several factors contributed to the general improvement in annual real wage growth over the last year, including tight labour markets (Section 1.1.3), increases in statutory minimum wages (see Section 1.2.2), and the adjustment of negotiated wages (catch-up process and new collective agreements being renegotiated – Box 1.3).

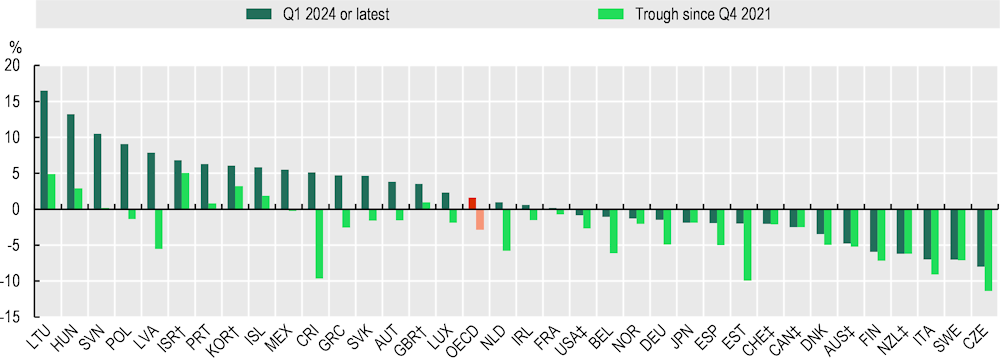

Figure 1.9. While real wage growth has turned positive in 2023, it remains below 2019 levels in several countries

Note: Otherwise indicated, nominal hourly wages refer to a constant-industry-structure “wages and salaries” component of the labour cost index. Statistics refer to the private sector only for Costa Rica, Japan, Korea, Mexico and the United States. Nominal wage series are seasonally adjusted for all countries except for Canada, Costa Rica, Israel, Japan, Korea, Mexico, New Zealand and Switzerland. Nominal hourly wage presents a significant amount of unreported income for Mexico.

†: Nominal hourly wage refers to the actual wage i.e. without any adjustment for sources of compositional shifts for Costa Rica, Israel, Korea, Mexico and the United Kingdom, and thus comparing these results with the other countries requires caution. Moreover, nominal hourly wage refers to the average monthly wages per employee job for Israel, and to the average weekly earnings for the United Kingdom.

‡: Nominal hourly wage controls for additional sources of compositional shifts, such as regions for Australia, Canada and New Zealand, job characteristics and workers’ characteristics for Australia and New Zealand, gender for Switzerland, and occupations for the United States. For Switzerland, the quarterly estimates refer to the annual Swiss wage index.

Real hourly wage is estimated by deflating the nominal hourly wage by the consumer price index (CPI-all items) which is adjusted, for the purpose of this analysis, using the X‑13ARIMA-SEATS Seasonal Adjustment Method. Cumulative percentage changes in real wages since Q4 2019 (Panel B) obtained with these adjustments do not differ substantively from those obtained without any adjustments as reported in the Annex Figure 1.A.3.

Countries are ordered by descending order of the year-on-year change in real hourly wages (Panel A). OECD is the unweighted average of the 35 OECD countries shown in this chart (not including Chile, Colombia and Türkiye). The trough (Panel B) refers to the quarter where real hourly wages were at their lowest value for the indicated country since Q4 2021. The annual growth in nominal and real wages (Panel A) refers to Q3 2023 for Israel, and Q4 2023 for Canada, Costa Rica, Japan, Korea, Mexico and New Zealand, and the cumulative percentage change (Panel B) refers to Q3 2019‑Q3 2023 for Israel and Q4 2019‑Q4 2023 for Canada, Costa Rica, Japan, Korea, Mexico and New Zealand.

Source: OECD calculations based on the Wage Price Index (Australian Bureau of Statistics) for Australia; the Fixed weighted index of average hourly earnings for all employees (Statistics Canada) for Canada; the Encuesta Continua de Empleo (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos) for Costa Rica; the Labour cost index by NACE Rev. 2 activity (Eurostat) for the European countries except the United Kingdom; the Wages and Employment Monthly Statistics (Central Bureau of Statistics) for Israel; the Monthly Labour Survey (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare) for Japan; the Labour Force Survey at Establishments (Ministry of Employment and Labour) for Korea; the Encuesta Nacional de Ocupación y Empleo y Encuesta Nacional de Ocupación y Empleo Nueva Edición (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía) for Mexico; the Labour Cost Index (Stats NZ) for New Zealand; the Swiss Wage Index (Federal Statistical Office) for Switzerland; the Monthly Wages and Salaries Survey (Office for National Statistics) for the United Kingdom; and Employment Cost Index (Bureau of Labor Statistics, retrieved from FRED) for the United States. OECD (2024), “Prices: Consumer prices”, Main Economic Indicators (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/0f2e8000-en (accessed on 18 June 2024).

Despite the recent pick-up in their year-on-year growth, real wages remain below their pre‑COVID‑19 levels in most countries, even though the average change across all 35 countries with available data is positive (Figure 1.9, Panel B).9 By Q1 2024, real wages had recovered at least some of the lost ground in 23 of the 27 countries in which they fell in the aftermath of the COVID‑19 crisis – rising above pre‑pandemic levels in 11 of them. However, real wages remained well below their pre‑pandemic levels in virtually all countries where they fell the most. Overall, in Q1 2024, real wages were still below their Q4 2019 level in 16 of the 35 countries with available data.

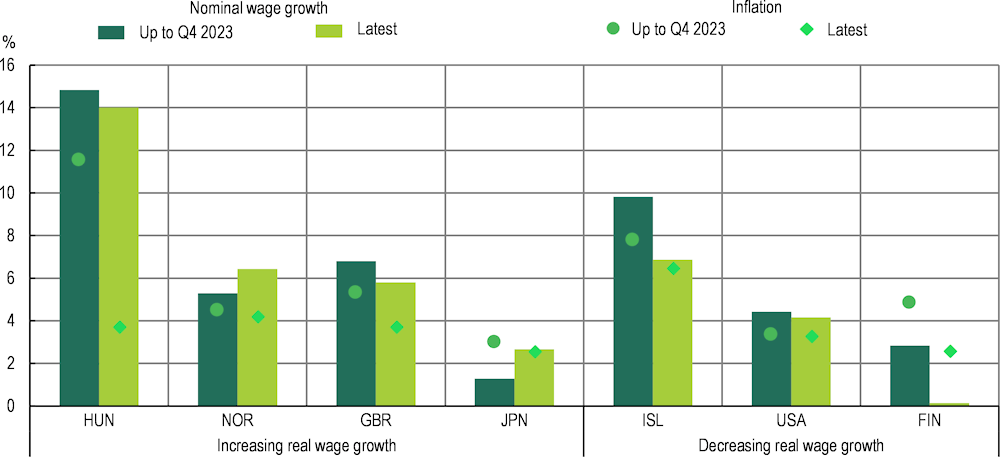

Box 1.2. Data for selected countries point to continued improvement in real wage growth in recent months generally driven by declining inflation

For a limited number of countries, it is possible to gain insights on very recent wage developments using monthly data. This analysis is subject to the caveat that the underlying measures differ between countries (and from those used in the main analysis in Figure 1.10) and are generally not seasonally adjusted.

Figure 1.10. Monthly data point to continued improvement in real wage growth

Year-on-year percentage change

Note: Up to Q4 2023 refers to the average of the monthly observations of the six months ending to December 2023. Latest refer to the average of all monthly observations available after December 2023. The last available data point is April 2024 for Finland, Hungary, Japan, Norway and the United Kingdom; and May 2024 for Iceland and the United States. For Norway, earnings observed in April 2024 corresponds to the preliminary value. Real wage growth is “increasing” (“decreasing”) where the year-on-year percentage change in the average real wage over January to April 2024 is higher (lower) than the year-on-year percentage change in the average real wage over July to December 2023.

Source: OECD calculations based on the Wage and salary indices by industry (Statistics Finland) for Finland; the Main earnings data (Central Statistics Office) for Hungary; the Wage indices by sector and month (Statistics Iceland) for Iceland; the Monthly Labour Survey (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare) for Japan; the Number of employment and earnings (Statistics Norway) for Norway;; the Monthly Wages and Salaries Survey (Office for National Statistics) for the United Kingdom; and the Current Employment Statistics (Bureau of Labor Statistics, retrieved from FRED) for the United States; OECD (2024), “Prices: Consumer prices”, Main Economic Indicators (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/0f2e8000-en (accessed on 26 June 2024).

That being said, the data for the months since the end of Q4 2023 point to an improvement in annual real wage growth in four of the seven countries with available data. This is generally driven by a decline in inflation rather than an increase in nominal wage growth.

Data from wages advertised in job postings on the online platform Indeed show improving or stable real wage growth in all countries with available data, except Spain and the United States (Figure 1.11). Consistently with the results above, where real wage growth is increasing, this is mainly driven by a fall in inflation rather than a significant up-tick in nominal wage growth. In fact, these data point to a decrease in nominal wage growth in five of the eight countries with available data (Canada, France, Germany, Spain, and the United States).

Figure 1.11. Posted wages point to a recent slowdown in nominal wage growth

Year-on-year percentage change, three‑month moving averages, from December 2023 to May 2024

Note: The posted wages are the average year-on-year percentage changes in wages and salaries advertised by job postings on Indeed.

Source: Indeed Wage Tracker (https://github.com/hiring-lab/indeed-wage-tracker); OECD (2024), “Prices: Consumer prices”, Main Economic Indicators (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/0f2e8000-en (accessed on 25 June 2024).

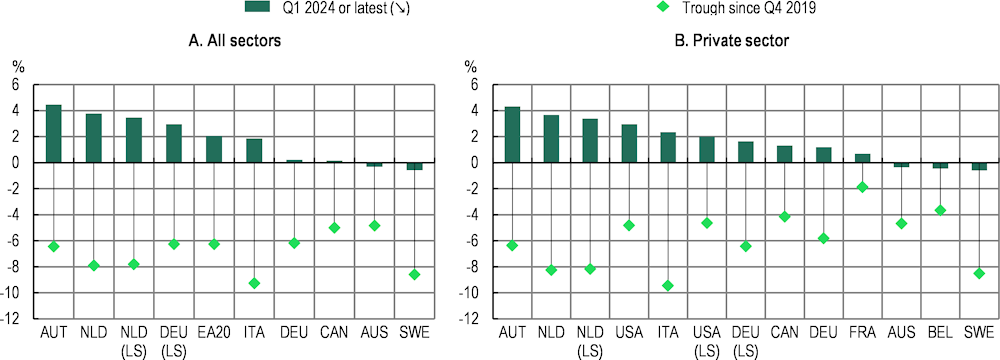

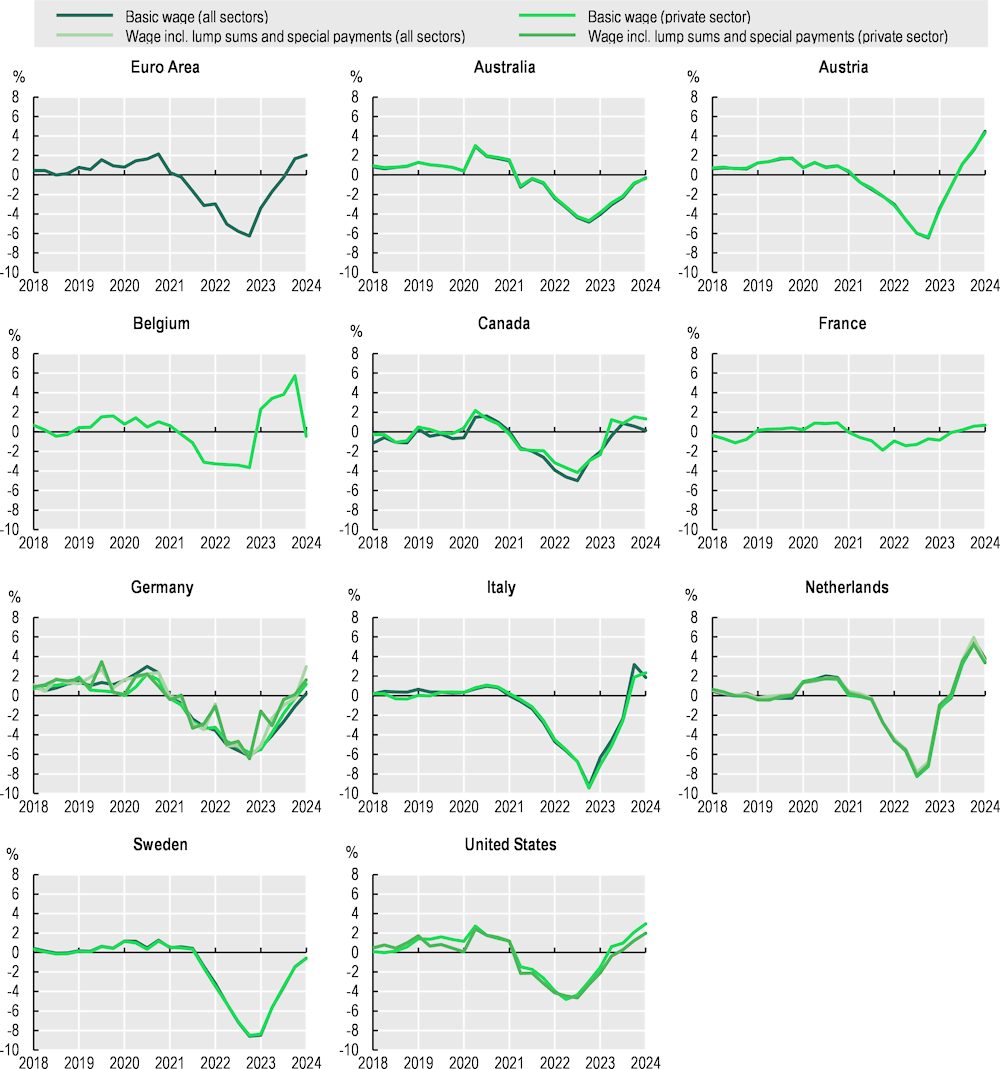

Box 1.3. Year-on-year growth in real negotiated wages has improved and remained negative only in a few countries in early 2024

Real growth in negotiated wages has improved over the course of 2023 and remained negative only in a few countries (Figure 1.12). In Q1 2024, negotiated wages were increasing in real terms on an annual basis in Austria, Canada, the Euro Area, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and the United States but continued to slightly decline in Australia and Sweden and stabilised, after one year of steady growth, in Belgium (Annex Figure 1.C.2). These developments reflect a combination of factors, including the staggered and infrequent nature of collective bargaining, the delay between the date of completion of negotiations and the effective revisions of pay, the infrequent use of automatic indexation to inflation, and the strength of workers’ bargaining power (Araki et al., 2023[11])). Overall, as more rounds of negotiation take place affecting an increasing number of workers, real growth in negotiated wages turns positive in more countries for some time, recovering some of the lost ground.

For Europe, the European Central Bank (ECB) indicator of future wage growth embedded in agreements reached in the latest quarter points to continuing growth in nominal wages, without signs of acceleration (Lane, 2024[12]). In fact, the latest release saw an increase in negotiated wage growth in the first quarter of 2024 to 4.7% – after it slightly moderated from 4.7% in the third quarter 2023 to 4.5% in the fourth quarter of 2023. Further agreements are expected to be renewed in 2024 which might have a significant impact on the dynamics of negotiated wages in the coming quarters.

Figure 1.12. Real negotiated wages in selected OECD countries

Year-on-year percentage change in real negotiated wages (i.e. resulting from collective agreements)

Note: International comparability of data on negotiated wages is affected by differences in definitions and measurement. Statistics are representative of all employees covered by a collective wage agreement for Austria, Belgium, the Euro Area (20), France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Sweden, and the United States. In Canada, statistics refer to collective bargaining settlements of all bargaining units covering 500 or more employees (units of 100 or more employees for the Federal Jurisdiction). For Australia and Canada, statistics refer only to employees affected by an increase of the negotiated wage at date. Wage increases in Austria, Belgium, the Euro Area (20), Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Sweden, and the United States refers to the average increase in negotiated wages (wages of union workers for the United States) weighted by the employment composition for a reference year (Laspeyres index). The reference year of the employment composition used is 2009 for Sweden, 2010 for Belgium and the Netherlands, January 2015 for the Euro Area (20), 2015 for Germany and Italy, 2016 for Austria, and 2021 for the United States. For Australia, Canada and France, wage increases refer to the average increase in negotiated wages weighted by the number of employees affected in the period considered. In Panel B, private sector for Germany refers to all industries excluding agriculture, public administration, education, health, and other personal services (Sections B to N of the NACE rev. 2).

LS: wages including lump sums and/or special payments. The trough refers to the quarter where the year-on-year percentage change in real negotiated wages was at its lowest value for the indicated country and series (basic wage or wage including lump sums) since Q4 2019.

Source: OECD calculations based on national data on negotiated wages, see Annex Table 1.C.3.in (Araki et al., 2023[11]) for further details; and OECD (2024), “Prices: Consumer prices”, Main Economic Indicators (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/0f2e8000-en (accessed on 28 June 2024).

1.2.2. Wages of low pay workers have performed relatively better in many countries

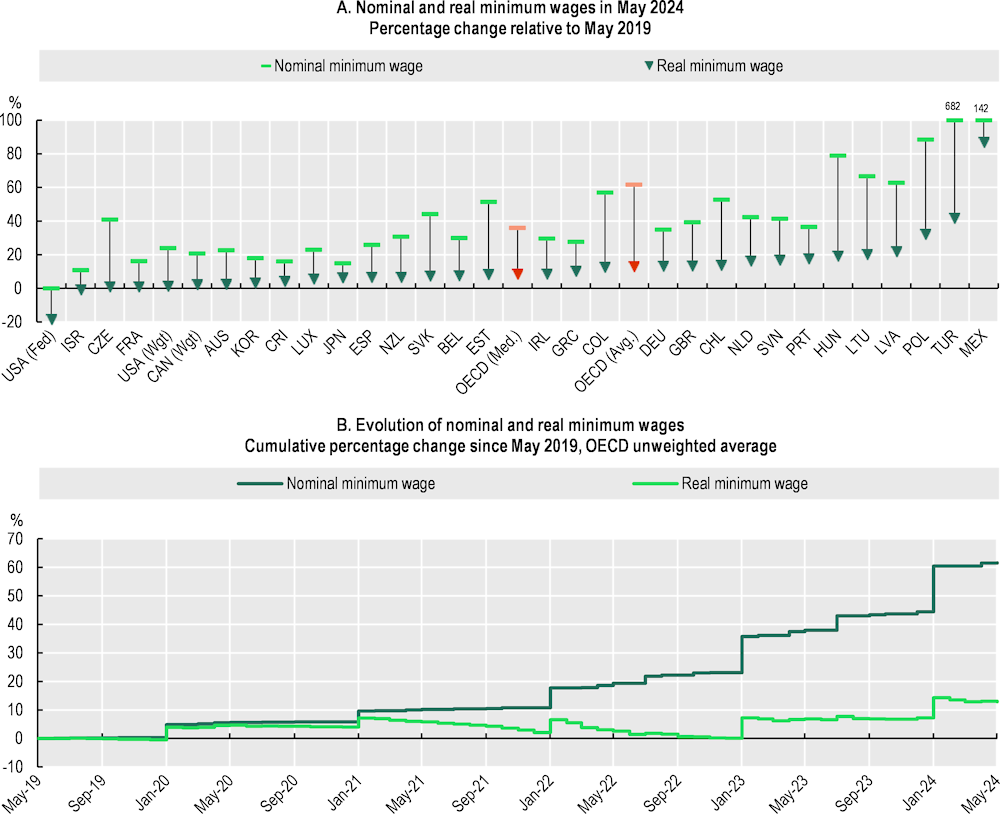

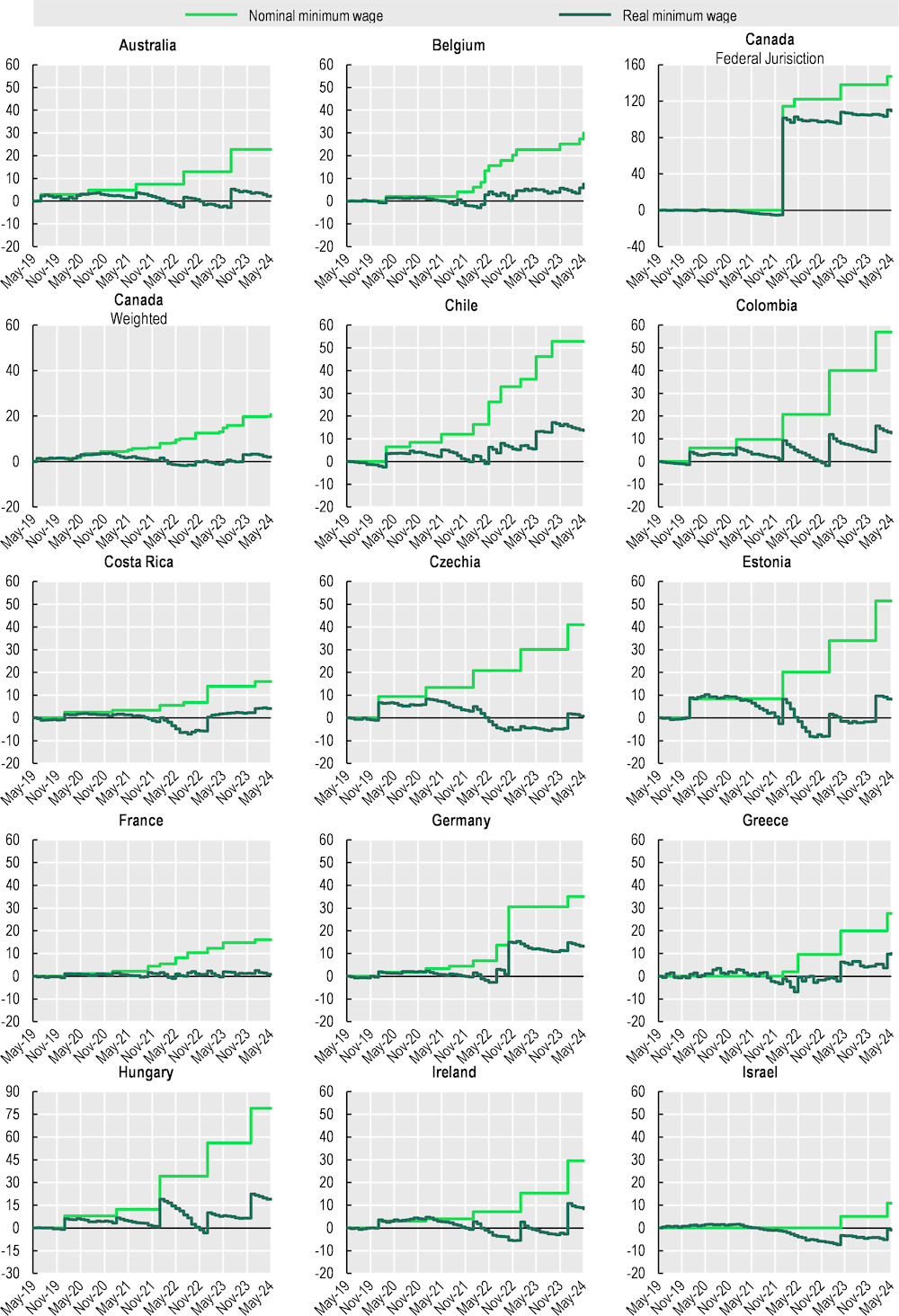

Statutory minimum wages in real terms are above their 2019 level in virtually all countries

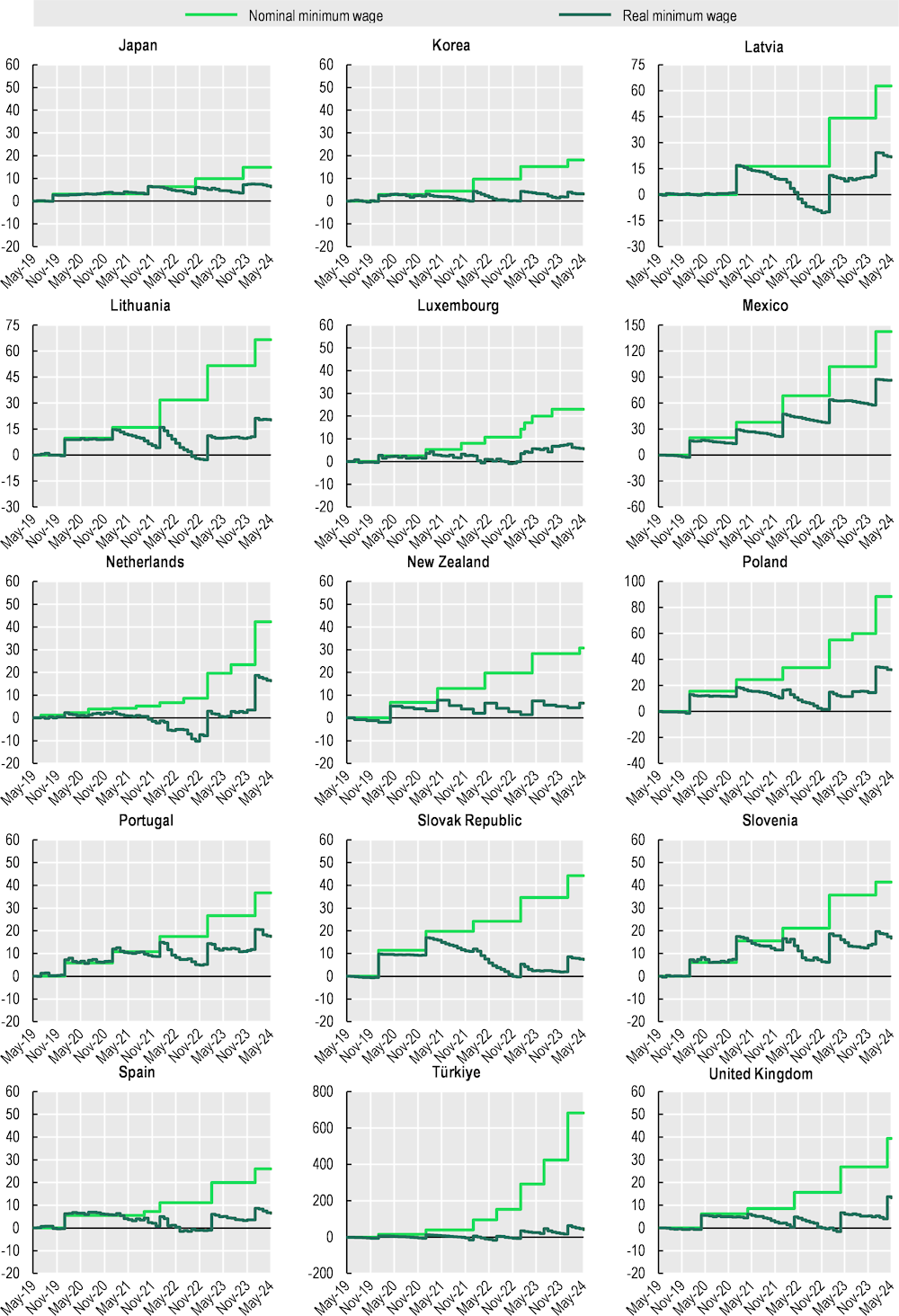

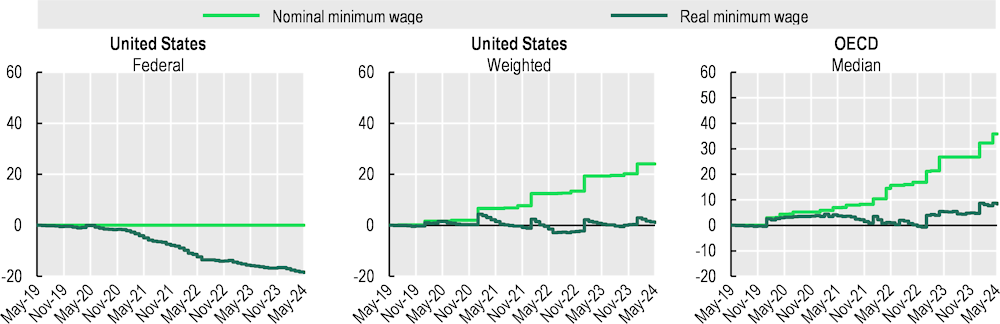

In May 2024, thanks to significant nominal increases of statutory minimum wages to support the lowest paid during the cost-of-living crisis, the real minimum wage was 12.8% higher than in May 2019 on average across the 30 OECD countries that have a national statutory minimum wage in place. This average figure is heavily influenced by the increases of more than 20% in Latvia, Lithuania, Mexico, Poland and Türkiye. However, the median increase, which is unaffected by outliers, was 8.3%, which is still quite significant compared to the increase in median wages.

The real value of the statutory minimum wage was below its level of 2019 in two countries – Israel and the United States. In the United States the federal minimum wage has not changed since 2009, but state‑level minimum wages have often increased in recent times raising the employment-weighted average real value of the minimum wage (Figure 1.13, Panel A).

Figure 1.13. Real minimum wages are above 2019 levels in virtually all countries

Note: “OECD (Avg.)” is the unweighted average of 30 OECD countries with a statutory minimum wage shown in this chart, except the United States (weighted); “OECD (Med.) is the median values across the same countries. Canada (weighted) is a Laspeyres index based on minimum wage of provinces and territories (excluding the Federal Jurisdiction) weighted by the share of employees of provinces and territories in 2019. United States (weighted) is a Laspeyres index based on minimum wage of states (not including territories like Puerto Rico or Guam) weighted by the share of nonfarm private employees by state in 2019. Change in real minimum wage for New Zealand (Panel A) is estimated by assuming that the CPI in May 2024 is the same as in Q1 2024. For further details on the minimum wage series used in this chart, current and planned minimum wage uprating in 2024, and the evolution of nominal and real minimum wages since May 2019 by country, see Annex 1.C.

Source: OECD Employment database, www.oecd.org/employment/emp/onlineoecdemploymentdatabase.htm, OECD (2024), “Prices: Consumer prices”, Main Economic Indicators (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/0f2e8000-en (accessed on 02 July 2024), and Australian Bureau of Statistics (May 2024), Monthly Consumer Price Index Indicator, ABS Website, accessed on 02 July 2024) for Australia.

Minimum wages have been able to keep up with inflation thanks to either automatic or discretionary increases introduced by countries (Araki et al., 2023[11]). Over the course of 2021 and 2022, the real gains from these adjustments quickly vanished on average across countries as inflation continued to increase (Figure 1.13, Panel B). In early 2023, many countries implemented significant nominal increases in the minimum wage that brought its average real value around 8% above its 2019 level. As inflation moderated, these real gains generally persisted over 2023 and were then strengthened by the new wave of nominal adjustments of January 2024.

There are indications of an increase in wage compression at the bottom of the wage distribution as proxied by industry and education

Since data on individual wages become available only with a significant lag for most countries, it is not yet possible to assess comprehensively how the recent wage crisis has affected wage inequality across countries. To provide some preliminary insights on how workers of different pay levels have fared, it is however possible to look at the evolution of wages by industry for most OECD countries and by , education, and percentiles of the wage distribution for five countries with data already available.

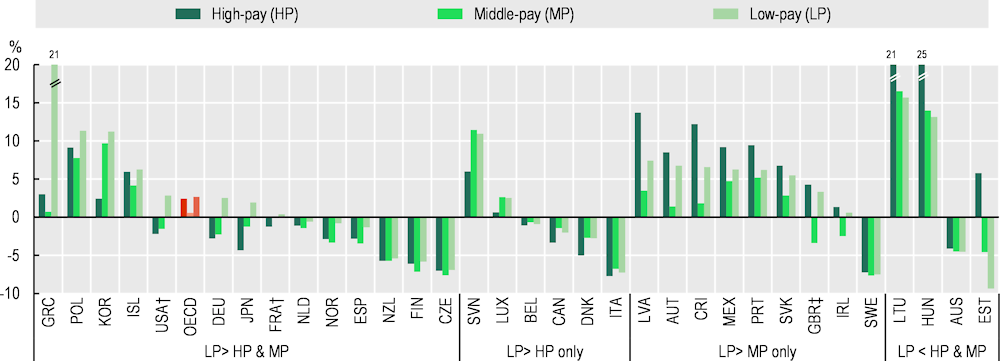

To offer an overview of wage developments by industry between Q4 2019 and Q1 2024, Figure 1.14 reports changes in real wages by industries aggregated in three broad groups: low-pay industries (accommodation and food services, administrative and support services, arts, entertainment and recreation, wholesale and retail trade); mid-pay industries (transportation and storage, manufacturing, other services, real estate activities, and construction); and high-pay industries (human health and social work, education, professional activities, information and communication, and finance and insurance). Industries are weighted by employment shares within each group.

Across the OECD, there is a pattern of compression of wages across workers of different pay levels, as proxied by industry wages, particularly at the bottom of the distribution. In 17 of the 33 countries with available data, real wages performed relatively better in low-pay industries than in both mid- and high-pay industries – either because they grew more or fell less. In nine other countries, real wages in low-pay industries outperformed mid-pay industries but not high-pay ones. Low-pay industries had the worst wage performance only in four countries, losing more than 1 percentage point relative to both mid- and high-pay industries only in Estonia.

Figure 1.14. Real wages in low-pay industries have performed relatively better in most countries

Percentage change in real hourly wages between Q4 2019 and Q1 2024

Note: Real wages are obtained by deflating nominal wages by consumer price inflation (all items) which are adjusted, for the purpose of this analysis, using the X‑13ARIMA-SEATS Seasonal Adjustment Method. Industries are ranked by the median wage in 2019 in the European Structure of Earnings Survey (SES). The ranking of industries is broadly consistent when 2019 data on median wages from the Current Population Survey of the United States are used. Low-pay industries (LP) include Accommodation and food service, Administrative and support service, Arts, entertainment and recreation and Wholesale and retail trade. Middle‑pay industries (MP) include Transportation and storage, Manufacturing, Other service, Real estate activities and Construction. High-pay industries (HP) include Human health and social work, Education, Professional activities, Information and communication and Finance and insurance. Average employment shares by industry over the four quarters of 2019 are used for aggregation and thus small inconsistencies between changes in wages by industry and changes in average wages are possible. Statistics refer to the percentage change in real hourly wages between Q4 2019 and Q4 2023 for Australia, Canada, Costa Rica, Japan, Korea, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States. OECD is the unweighted average of the 33 OECD countries shown in this chart (not including Chile, Colombia, Israel, Switzerland and Türkiye).

†: There are missing industries: Arts, entertainment and recreation is not included for the United States; Human health and social work and Education are not included for France.

‡: Average weekly earnings are used for the United Kingdom. Moreover, wages in the public sector are excluded for Costa Rica, Japan, Korea, Mexico, the United Kingdom and the United States.

Source: OECD calculations based on the Wage Price Index (Australian Bureau of Statistics) for Australia; Fixed weighted index of average hourly earnings for all employees (Statistics Canada) for Canada; Encuesta Continua de Empleo (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos, Costa Rica) for Costa Rica; the wages and salaries component of labour cost index by NACE Rev. 2 activity (Eurostat) for European countries; Monthly Labour Survey (Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare) for Japan; Labour Force Survey at Establishments (Korean Ministry of Employment and Labour) for Korea; Nacional de Ocupación y Empleo, Encuesta Telefónica de Ocupación y Empleo, Encuesta Nacional de Ocupación y Empleo Nueva Edición (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, Mexico) for Mexico; Labour Cost Index (Statistics New Zealand) for New Zealand; Swiss Wage Index (Swiss Federal Statistical Office) for Switzerland, Monthly Wages and Salaries Survey (UK Office for National Statistics) for the United Kingdom; and Employment Cost Index (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, retrieved from FRED) for the United States; OECD (2024), “Prices: Consumer prices”, Main Economic Indicators (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/0f2e8000-en (accessed on 18 June 2024).

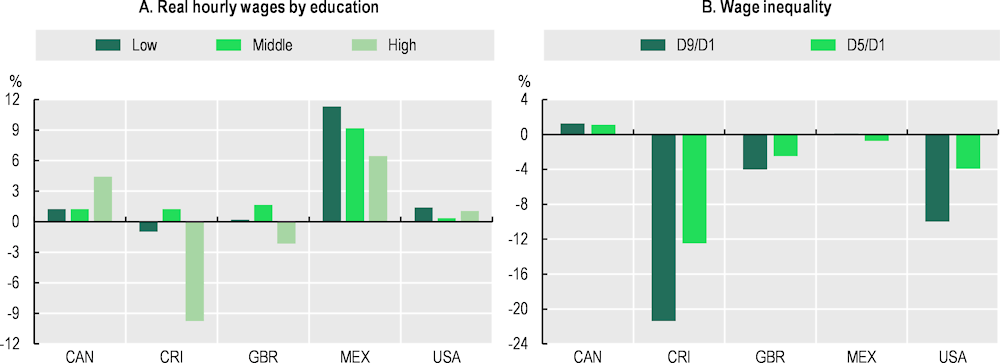

Results by education for the five countries with available data also provide additional support for a general pattern of wage compression, especially at the bottom of the distribution (Figure 1.15). Between 2019 and 2023, real wage growth was stronger for the low- and mid-pay groups by education in four of the five countries (Costa Rica, Mexico, the United Kingdom, and the United States). Canada was the only country among those with available data where real wages grew more for the highest educated.

Figure 1.15. Changes in real wages by education and wage inequality

Percentage change between Q4 2019 and Q4 2023

Note: The level of education is classified according to the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED 2011) as follows: “Low” (ISCED 0‑2: early childhood education, primary education, and lower secondary education); “Middle” (ISCED 3‑4: upper secondary education and post-secondary non-tertiary education); “High” (ISCED 5‑8: short-cycle tertiary education, bachelor’s or equivalent level, master’s or equivalent level, and doctoral or equivalent level). D9/D1: ratio of the top (9th decile) and the bottom of the earnings distribution (1st decile). D5/D1: ratio of the median (5th decile) and the bottom of the earnings distribution (1st decile).

Source: OECD estimations based on the Labour Force Survey (Statistics Canada) for Canada, the Encuesta Continua de Empleo (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos) for Costa Rica, the Encuesta Nacional de Ocupación y Empleo, Encuesta Telefónica de Ocupación y Empleo, Encuesta Nacional de Ocupación y Empleo Nueva Edición (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía) for Mexico, the Labour Force Survey (Office for National Statistics) for the United Kingdom, and the Current Population Survey (Bureau of Labor Statistics) for the United States. OECD (2024), “Prices: Consumer prices”, Main Economic Indicators (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/0f2e8000-en (accessed on 15 May 2024).

Among the same five countries, there is some indication that overall wage inequality might have decreased since 2019 in Costa Rica, the United Kingdom, and the United States, but not in Canada and Mexico (Figure 1.15, Panel B). The largest reductions in inequality occurred in the two countries with the highest initial level of inequality – Costa Rica and the United States.

More granular data on wages are necessary to provide a comprehensive assessment of changes in wage inequality and their determinants. Wage dynamics could vary across the wage distribution due to several factors, including developments in labour demand and supply, minimum wage laws, collective bargaining, and employer monopsony power. Cross-country analysis attempting to explain differences in wage dynamics across industries over the past two years has been inconclusive and is hindered by limited sample sizes and the presence of many confounding factors (Araki et al., 2023[11]).

To date, the only detailed country-specific study is that by Autor et al. (2023[13]) on the United States who document a significant reduction in wage inequality in line with the results presented above. In fact, they report a reduction in the college premium and a remarkable compression of the wage distribution which counteracted almost 40% of the four‑decade increase in aggregate inequality between the 10th and 90th percentile. They find that the pandemic increased the elasticity of labour supply to firms in the low-wage labour market, reducing employer market power and spurring rapid wage growth at the bottom. Among the possible drivers, the authors mention a decrease in work-firm attachment spurred by the large number of separations that occurred during the pandemic. By contrast, they find that the fall in inequality is not explained by (state‑level) changes in minimum wages.

Lower wage inequality can lead to a mix of social and economic benefits and challenges. On the positive side, lower wage disparities tend to reduce overall income inequality which can increase social cohesion, reduce social tensions, and enhance economic growth by allowing more people to develop their human capital (OECD, 2015[14]; OECD, 2018[15]). However, high wage compression can pose efficiency challenges if wages do not reflect productivity or the demand for specific skills (OECD, 2018[15]; OECD, 2018[16]).

It is nevertheless critical to bear in mind the specific context in which the recent wage developments have taken place. Most notably, the recent increases in minimum wages relative to average wages were generally aimed at providing some protection for the most vulnerable workers against the cost-of-living crisis, spreading the cost of inflation equitably between firms and workers, but also among workers of different pay levels. In several countries, significant increases in tightness in low-pay sectors have also likely contributed to upward wage pressures for workers in the lower part of the wage distribution. Looking forward, with inflation expected to decline, labour market conditions stabilising and labour market tightness easing especially in low-pay industries, wages are likely to continue to adjust along the distribution as they recover the purchasing power lost in the past two years. Hence, whether the recent signs of an increase in wage compression will lead to a persistent reduction in wage inequality remains an open question.

1.2.3. As real wages recover, unit profit growth has slowed down and even turned negative in some countries

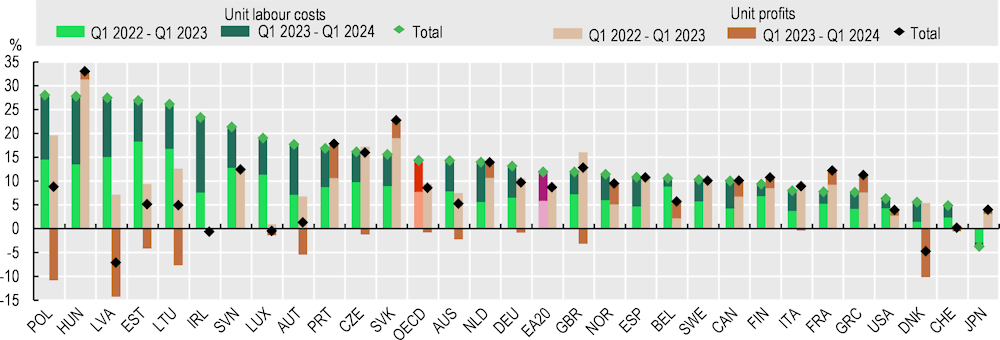

In the aftermath of the COVID‑19 crisis, unit labour costs10 increased in most OECD countries as growth in nominal wages exceeded productivity growth. Unit profits also generally increased, indicating that firms were able to increase prices beyond the increase in the cost of labour and other inputs. In fact, between 2019 and 2022, unit profits increased more than unit labour costs in many countries and sectors, making an unusually large contribution to domestic price pressures and driving down the labour share of income (Araki et al., 2023[11]).

The most recent data point to a change in the relative dynamics of unit profits and unit labour costs in several countries. Between the beginning of 2022 and Q1 2024, unit labour costs grew more than unit profits in about two‑thirds of the countries with data available (19 out of 29) (Figure 1.16). This pattern has become more pronounced in 2023, when unit labour costs increased more than unit profits in 25 countries. In fact, in 14 countries, unit profits even declined in 2023, an indication that they have started to buffer some of the inflationary impact of rising labour costs (ECB, 2023[17]).

Figure 1.16. Profits are beginning to buffer some of the increase in labour costs

Cumulative percentage change since Q4 2021, seasonally adjusted data

Note: OECD is the unweighted average of the 29 OECD countries shown in this chart (not including Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Iceland, Israel, Korea, Mexico, New Zealand and Türkiye). Euro Area represents the 20 Eurozone countries. For Norway, the data are based on mainland Norway. Unit labour costs and unit profits are calculated by dividing compensation of employees and gross operating surplus respectively, by real GDP. For Japan and Norway, gross operating surplus is approximated by deducting compensation of employees from nominal GDP – and hence also include unit net taxes.

Source: OECD (2024), “Quarterly National Accounts”, OECD National Accounts Statistics (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/data-00017-en (accessed on 21 June 2024), Cabinet Office, Government of Japan, Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI) Quarterly Estimates of GDP, www.esri.cao.go.jp/en/sna/sokuhou/sokuhou_top.html, for Japan, and Statistics Norway, Quarterly National Accounts, www.ssb.no/en/nasjonalregnskap-og-konjunkturer/nasjonalregnskap, for Norway.

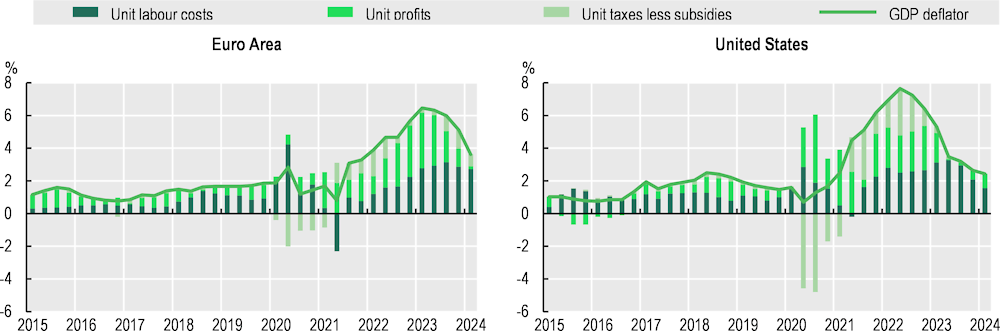

As a result of the recent changes in the relative dynamics of unit labour costs and unit profits, the contribution of unit profits to domestic price pressures has decreased, but remaining higher than prior to the pandemic in the Euro Area (Figure 1.17) – see also (OECD, 2023[18]). In addition, these results imply a reduction in the profit share of income after its growth between 2019 and 2022 (Araki et al., 2023[11]).

These developments were largely expected as they reflect the ongoing recovery of purchasing power by wages described above, rather than a warning sign of wage‑price spirals (Araki et al., 2023[11]). Indeed, the contribution of unit labour costs to domestic price pressures is likely to remain sustained for some time as this catch-up process continues, unless labour productivity growth picks up. Reassuringly, however, there are currently no signs of further acceleration in nominal wage growth (Box 1.2). Moreover, in many countries, the growth in unit profits over the last three years allows for more buffering against the inflationary pressures stemming from the recovery of real wages (Lane, 2024[12]).11 In the medium term, however, labour productivity growth is essential to ensure sustainable increases in wages that do not generate increases in unit labour costs and further inflationary pressures.

Figure 1.17. The contribution of labour costs to domestic price pressures has been increasing

Contribution to the GDP deflator, year-on-year percentage changes, seasonally adjusted data

Note: Euro Area refers to the 20 Eurozone countries. Unit labour costs, unit profits and unit taxes less subsidies are calculated by dividing compensation of employees, gross operating surplus and taxes less subsidies on productions and imports, respectively, by real GDP. For the United States, statistical errors are removed. Compensation of employees, gross operating surplus, taxes less subsidies on productions and imports, gross domestic products and deflators are denominated in local currencies. For the United States, changes in the GDP deflator are reported net of statistical discrepancies.

Source: OECD (2024), “Quarterly National Accounts”, OECD National Accounts Statistics (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/data-00017-en (accessed on 21 June 2024).

1.3. An update on job quality

As other aspects of jobs, beyond wages, need to be monitored to assess what has happened to workers’ overall well-being following the COVID‑19 pandemic and the recent cost-of-living crisis, this section provides an update on job quality drawing on the conceptual framework developed by the OECD, which was then adopted by the G20. Job quality is defined along three main complementary dimensions that have been shown to be particularly relevant for workers’ well-being in the existing literature on economics, sociology and occupational health (OECD, 2014[2]; Cazes, Hijzen and Saint-Martin, 2015[1]):

Earnings quality. This measures the extent to which the earnings received by workers contribute to their well-being by taking account of the average real level of earnings and the way earnings are distributed across the workforce.12

Labour market (in)security. This is defined in terms of the unemployment risk13 and unemployment insurance; it measures the expected monetary loss associated with becoming and staying unemployed as a share of previous earnings by taking account of the mitigating role of public unemployment insurance (in terms of coverage of the benefits and their generosity).

The quality of working environment. This captures non-monetary aspects of job quality, such as the nature and content of work performed, working-time arrangements and workplace relationships; it measures the incidence of workers experiencing job strain, a situation where workers have insufficient resources in the workplace to meet job demands.

Job quality indicators are updated with the latest available data (2022 or 2021). They are also compared to 2015 values – the last time that the OECD job quality framework was updated − except for the third dimension, the quality of the working environment, due to significant methodological changes, which makes job strain indicators not comparable over time (see below).

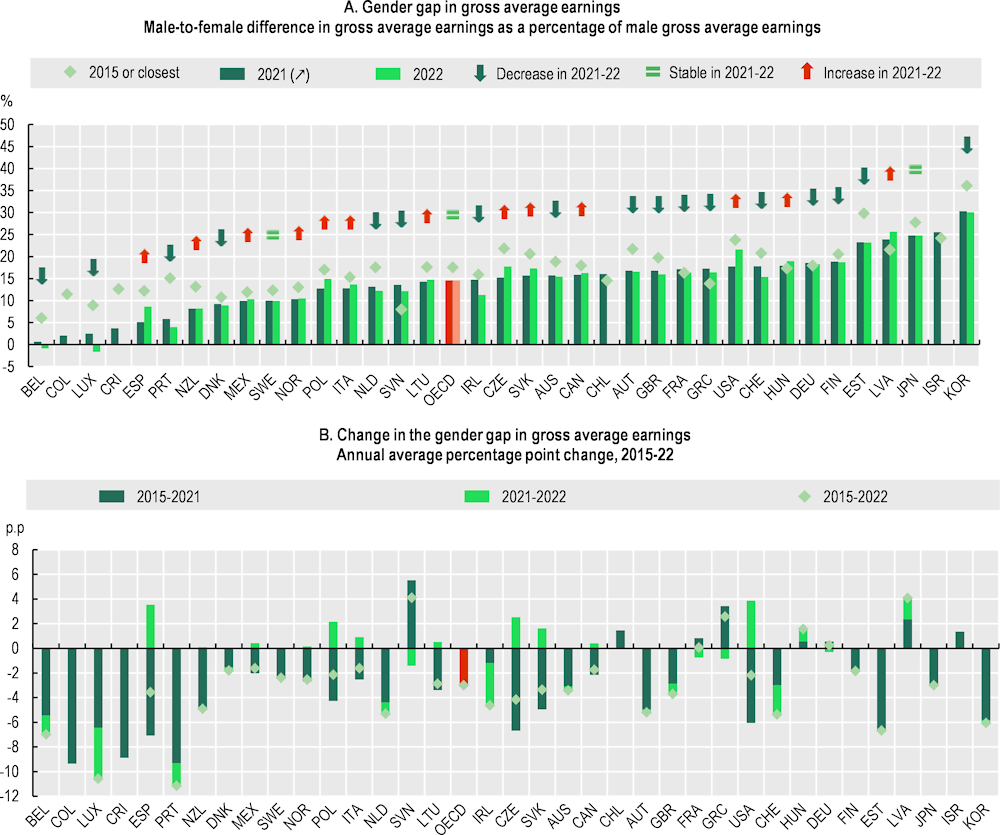

Both earnings quality and labour market security generally improved across the OECD. Between 2015 and 2021,14 earnings quality indicators show generally positive patterns across the 36 OECD countries for which data are available:15 gross hourly earnings expressed in 2022 USD purchasing power parity (PPP) adjusted by inequality16 increased from USD 22.7 to USD 24.7 between 2015 and 2021 for the OECD average (Figure 1.18, Panel A). The increase in earnings quality was largely driven by higher average earnings. Yet, higher equality of earnings also played a role − notably in countries which had the highest increase in the overall earnings quality (above 3 annual average percentage change), such as Czechia, Estonia, Israel, Korea, Lithuania, New Zealand, Poland, Slovenia and the Slovak Republic, but also in other countries, such as Canada, Germany, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States (Figure 1.18, Panel B). Finally, in the few countries where earnings quality was stable or slightly decreased between 2015 and 2021 (Belgium, Ireland, Italy, Spain and Switzerland) the pattern was mainly due to a slight increase in wage inequality that was not offset by the rise in average earnings, except for Greece where lower average earnings between 2015 and 2021 drove the decrease in earnings quality.

Figure 1.18. Earnings quality in OECD countries, 2015, 2021 and 2022

Note: Calculations based on the OECD Earnings Distribution Database and the average hourly earnings per full-time equivalent employee at constant prices and 2022 USD PPPs derived from the OECD Annual National Accounts Database. 2015 refers to 2014 for Estonia, France, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain and Switzerland. 2021 refers to 2020 for Poland. No data in 2022 for Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica and Israel. OECD is the unweighted of the 32 OECD countries with data available in 2022 shown in this chart (not including Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Iceland, Israel and Türkiye).

Source: OECD calculations based on the OECD Earnings distribution database, www.oecd.org/employment/emp/onlineoecdemploymentdatabase.htm and the OECD Annual National Accounts Database.

However, updates for 2022 show that earnings quality decreased between 2021 and 2022 in 26 of the 32 countries for which data are available (Figure 1.18, Panel A). This deterioration reflects the significant impact of inflation on real wages and wage distribution discussed in Araki et al. (2023[11]) and Section 1.2. These declines in earnings quality are generally driven by a reduction in average real earnings – even if higher earnings inequality also played a role in Estonia, Ireland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands,17 New Zealand and Portugal. Conversely, in Hungary, Latvia and Spain, earnings quality increased due to a significant decrease in earnings inequality,18 which counterbalanced the decline of average earnings.

Finally, the comparison of the gender gaps in average earnings show a general improvement across the OECD of women’s earnings quality relative to men’s one19 between 2015 and 2022 (Annex Figure 1.B.1).

Labour market security generally improved across the OECD between 2015 and 2022: in most of the 31 OECD countries20 for which 2022 indicators are available, labour market security increased since 2015 (Figure 1.19, Panel A). This positive pattern was driven by both lower unemployment rates and higher unemployment insurance: on average, the expected monetary loss associated with unemployment decreased by 1.9 percentage points between 2015 and 2022 for the OECD area. This reflects the combined impact of lower unemployment inflows in most OECD countries, as well as the widespread use of job and income support measures as a response to the COVID‑19 pandemic across the OECD (OECD, 2021[19]; 2022[20]).21 The sharpest drop in labour market insecurity (above 8 percentage points) occurred in Greece22 and Spain, due to the significant declines of unemployment rates and generous income protection measures during the COVID‑19.23 It also reflected the effect of more structural measures, such as the 2021 labour market reform in Spain and the introduction of the Guaranteed Minimum Income in Greece. In contrast, the increase in labour market insecurity observed in Chile, Colombia and Costa Rica was driven by higher unemployment risk and no unemployment benefit schemes to mitigate the monetary loss associated to it in the two latter countries. In other OECD countries, the improvement in labour market security indicators was rather modest except for Italy, Lithuania, Portugal and the Slovak Republic where it was above 4 percentage points (Figure 1.19, Panel B).

As for labour market security by gender, data show little change between 2015 and 2022 in the differences in unemployment risk24 between men and women except for a few countries (Annex Figure 1.B.2).

Figure 1.19. Labour market (in)security in OECD countries, 2015 and 2022

Note: Unemployment risk refers to the annual unemployment rate. Unemployment insurance refers to the coverage rate of unemployment insurance (UI) times its average net replacement rate among UI recipients plus the coverage rate of unemployment assistance (UA) times its net average replacement rate among UA recipients plus the share of those not covered by unemployment benefits [or the ratio of the number of social assistance (SA) recipients to the number of unemployed if this is lower] times the SA replacement rate. The average replacement rates for recipients of UI and UA take account of family benefits and social assistance if eligible. Labour market insecurity is estimated as the unemployment risk times one minus unemployment insurance, which may be interpreted as the uninsured average expected earnings loss associated with unemployment as a share of previous earnings. OECD is the unweighted average of the 38 OECD countries shown in this Chart. Countries are ordered by descending order of the labour market insecurity in 2022 (Panel A). The latest year refers to 2021 for Canada, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Israel, Italy, and Slovenia. p.p: percentage point.

Source: OECD calculations based on the OECD Labour Market Statistics (database), http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/data-00322-en, the OECD Benefit Recipients (database), the OECD Labour Market Programmes (database), http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/data-00312-en and the OECD Taxes and Benefits (database), http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/data-00201-en.

Comparable measures of the quality of the working environment are limited by the diversity of countries’ approaches to collecting information and the general paucity of available data on working conditions.25 Still, comparable data are available for 25 OECD European countries in the European Working Conditions Telephone Surveys (EWCTS) carried out by Eurofound in 2021. As defined in the OECD conceptual framework,26 the quality of the working environment is measured by the incidence of workers experiencing job strain – i.e. a situation where the job demands (those aspects of jobs which require sustained physical and psychological efforts, and may negatively affect workers’ well-being) exceed the job resources (those attributes of jobs that may induce a motivational process) that workers have at their disposal (see Annex 1.B). The key features of the job strain indicators are sketched in Table 1.1. Unlike the two other job quality dimensions, only 2021 results are discussed for the quality of the working environment due to important methodological changes introduced in the 2021 EWCTS edition.27

Table 1.1. Job demands, job resources and job strain

|

Job strain, as the result of… |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

… too many job demands |

… and too few job resources |

||

|

Physical risk |

|

Social support at work |

|

|

Physical demands |

|

Task discretion and autonomy |

|

|

Work intensity |

|

Learning opportunities |

|

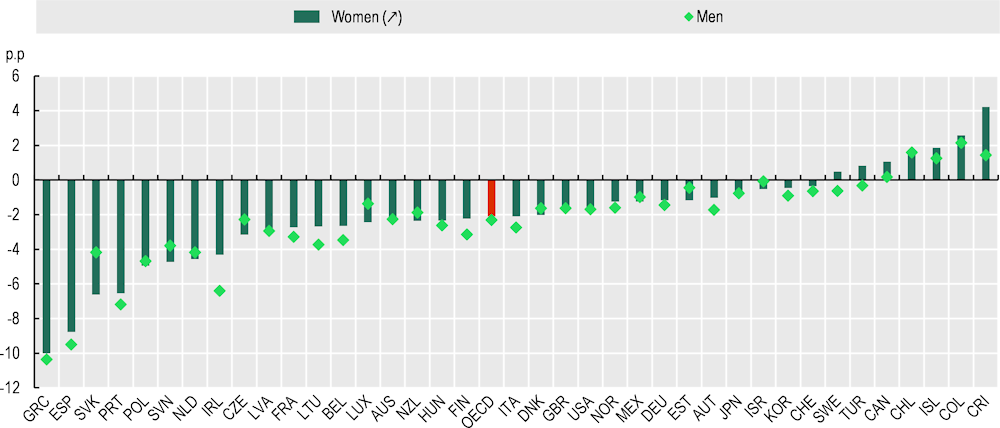

On average for the 25 OECD European countries for which data are available, 13% of workers experienced job strain in 2021 (Figure 1.20, Panel A). More women than men experienced job strain, but the differences are small (13.3% on average for women against 12.7% for men), except for a few countries where further analysis would be necessary to explore the factors driving the gap, notably composition effects (see below). Broken down further by degree of strain, the results show that 3.6% of workers experienced high strain (i.e. where the number of job demands exceeds by at least two the number of job resources), while 9.4% of them experienced moderate strain (i.e. where the number of job demands exceeds by one the number of job resources) (Figure 1.20, Panel B). While a few countries clearly performed better than others, in three‑quarters of the countries reviewed, the share of strained workers ranged between 11% and 15%. Yet, it was below 10% in Estonia, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Slovenia and around 17% in Czechia and Finland, and up to 18% in France. Overall, work intensity was the most common job stressor, with 73% of workers reporting they had to cope with this type of constraint at work. Turning to job resources, the lack of social support at work appeared to be the main area of concerns in 2021, as being reported by workers as insufficiently provided to them.28

Figure 1.20. Job strain in OECD European countries, 2021

Percentage of employees aged 16‑64 in OECD European countries, 2021