The Assessment and recommendations present the main findings of the OECD Green Growth Review of Egypt and identify 40 recommendations to help Egypt make further progress towards greening its economy. The OECD Working Party on Environmental Performance reviewed and approved the Assessment and recommendations on 28 May 2024.

OECD Green Growth Policy Review of Egypt 2024

Assessment and recommendations

Abstract

1. Key environmental trends

Addressing key environmental challenges

Egypt is a rapidly growing emerging economy and a demographic heavyweight on the African continent. Located at the crossroads between Africa, Europe and Asia, the country is a natural bridge between people and goods around the world, notably through the Suez Canal.

Egypt is among the best economic performers in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, with a five-year average real growth rate of 4.8% between 2018 and 2022, compared to 1.7% in OECD countries (OECD, 2024[1]). The unemployment rate has nearly halved since 2014, reaching 7.2% in 2022. However, female labour participation is weak, below the average of MENA countries (Government of Egypt, 2021[2]). The Decent Life, or Haya Karima presidential initiative, greatly contributed to improving livelihoods of most vulnerable people but more needs to be done to reduce the number of people living below the national poverty line.

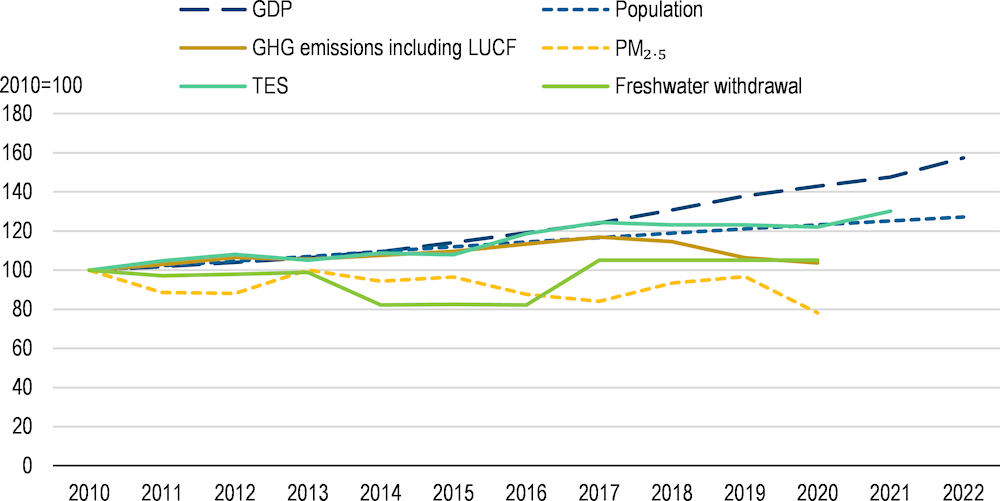

High population growth is increasing pressure on Egypt’s natural environment, especially on its rich biodiversity (Government of Egypt, 2016[3]). Given the country’s vast deserts, people are concentrated along the Nile River and its Delta. Urbanisation is advancing rapidly, which has led to urban sprawl in the past decades despite efforts to build new urban communities in desert areas (Section 3). The government has taken several measures to improve air quality (Figure 1), including the Greater Cairo Air Pollution Management and Climate Change Project. The country has also begun to tackle waste but a larger population will require more sustainable use of natural resources to advance towards a circular economy.

The country has recorded a gradual decline in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions since 2017 (Figure 1). It managed to partially decouple GHG emissions from economic and population growth, thanks notably to efficiency gains in energy industries and support for renewable energy projects. However, Egypt remains one of Africa’s leading oil and gas producing countries. Scaling up use of renewable energy could further advance decoupling trends, given the country’s large potential.

The Ministry of Environment (MoE) aims to develop a new Environment Law to cover climate action, biodiversity and pollution management. This proposed update from the 1994 edition of the law provides an excellent opportunity to set a unifying legal framework for environmental protection and climate action to support the achievement of Egypt’s national and international commitments, alongside private sector investment. The process, to take place within the next three years, will gain from involving relevant sectoral ministries at an early stage to build consensus and foster a whole-of-government approach to environmental issues.

Figure 1. Egypt has made some progress in decoupling environmental pressures from economic growth

Note: GDP: gross domestic product (constant prices); GHG: greenhouse gases; LUCF: land-use change and forestry; PM2.5: particulate matter of 2.5 μm size; TES: total energy supply.

Source: EC (2022), Emission Database for Global Atmospheric Research (EDGAR) v6.1, https://edgar.jrc.ec.europa.eu/dataset_ap61; FAO (2024), FAOSTAT (database), www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data; AQUASTAT (database); World Bank (2024), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators; World Resources Institute (2022), Climate Watch Historical GHG Emissions, www.climatewatchdata.org/ghg-emissions.

Addressing climate change requires strengthening institutional capacity

The National Climate Change Strategy 2050, launched in 2022, provides a comprehensive framework for Egypt’s climate mitigation and adaptation priorities. It articulates links between its main goals and the climate change goals in Egypt’s Vision 2030 (Government of Egypt, 2022[4]).

Egypt has started operationalising the National Climate Change Strategy 2050. However, it is facing implementation challenges related to financial resources to expand capacity at all levels of government. The launch of the domestic measurement, reporting and verification system is conditional on funding. At this stage, selected action plans are being developed and capacity building workshops at sectoral and governorate level conducted. For instance, an action plan for improving climate action governance is under development. Activities of the Centre of Excellence for Research and Applied Studies of Climate Change and Sustainable Development at the National Research Centre have been strengthened.

The National Council for Climate Change (NCCC), headed by Egypt’s Prime Minister, is well positioned to facilitate inter-ministerial co‑ordination. The NCCC should better communicate on its activities, decisions and outcomes. A co‑ordination mechanism for subnational governments could help create opportunities for mutual learning across governorates. Drawing on the experience of other countries, an independent scientific body of climate experts could monitor progress and advise the NCCC.

Egypt last submitted official GHG emissions data to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in 2015. At the time of writing, it was about to finalise its fourth communication to the UNFCCC, including updated GHG emissions data. In line with the commitments under the Paris Agreement’s Enhanced Transparency Framework, more regular GHG emissions updates are needed to help analyse the impacts of mitigation and adaptation measures. Achieving this requires strengthening capacity of the Egyptian Environmental Affairs Agency (EEAA) and Egypt’s Central Agency for Public Mobilisation and Statistics (CAPMAS). Efforts to incorporate a Climate Change GHG Unit within CAPMAS go in the right direction.

Egypt needs to step up its climate ambition, as the global 1.5 °C goal is falling out of reach

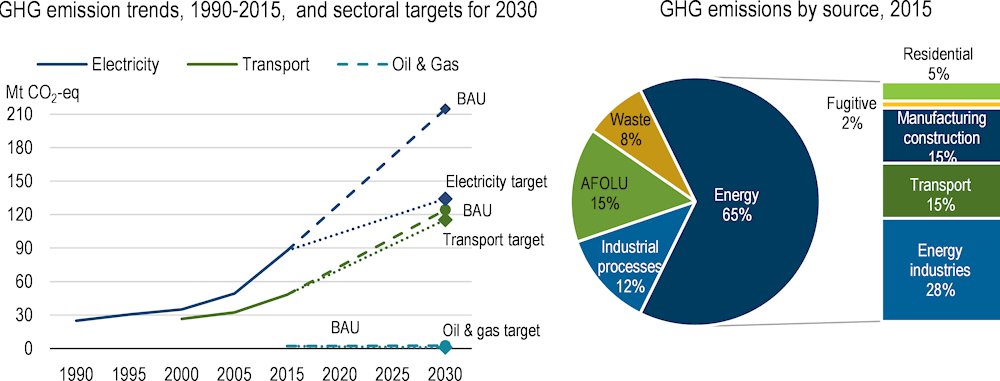

Egypt's total GHG emissions increased at a much faster rate than the world average. In 2015, the energy sector was responsible for 65% of total emissions (Figure 2). Egypt’s emissions per capita were estimated at 2.8 tonnes in 2020. This was less than half the global average of 6.3 tonnes and more than three times below the OECD average of 10.5 tonnes in 2021 (OECD, 2024[5]).

Figure 2. Egypt set three sector-specific targets to reduce emissions

Note: AFOLU: agriculture, forestry and other land use; BAU: business-as-usual; GHG emissions and targets for electricity, oil and gas, and transport sectors are provided in Egypt’s first and second updated Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC). Official data are available up to 2015 from Egypt's UNFCCC Biennial Update Report. Oil and gas data are available for 2015 only. Data are shown in solid lines, while linear projections are represented by dotted lines.

Sources: Government of Egypt (2023), Egypt's second updated NDC; Government of Egypt (2019), Egypt Biennial Update Report.

Over the past decade, Egypt has considerably increased its national and international climate commitments. As host of the 27th Conference of Parties (COP27) to the UNFCCC, Egypt’s climate commitment gained international attention. COP27 also raised awareness within Egypt, catalysing its domestic climate agenda. Many new initiatives have been launched with the support of development partners (e.g. Nexus of Water, Food and Energy Platform) (NWFE, 2022[6]). Egypt should continue to capitalise on this political momentum by updating policies, revising sectoral strategies and upgrading programmes through a climate lens while strengthening subnational capacity.

The first updated Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC), published ahead of COP27 in 2022, was a major step forward. For the first time, the government set tangible national GHG emissions reduction targets for three sectors: -33% for electricity, -7% for transport and -65% for oil and gas1 by 2030 compared to business-as-usual, conditional on more international financial support (Figure 2), (Government of Egypt, 2022[7]). The electricity target was tightened to -37% in the second updated NDC in 2023. These three sectors cover less than half of Egypt’s GHG emissions. As in many emerging economies, Egypt’s climate targets are not legally binding.

Egypt could progressively introduce more ambitious targets and broaden the scope of its emission reductions targets to cover other sectors. Setting a projected peak year for GHG emissions, along with intermediate targets, would inform long-term planning and send strong price signals in favour of low-carbon investment. This would prevent further investment in stranded high carbon assets and help reduce dependence on fossil fuel.

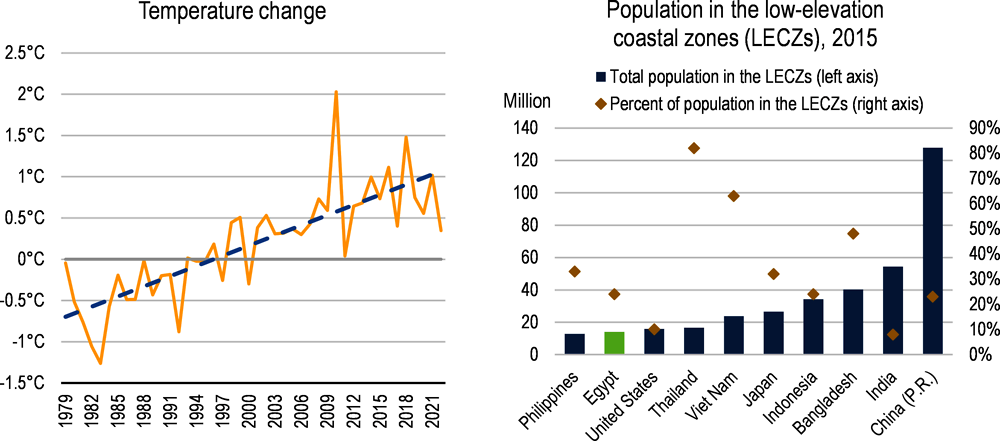

Egypt has stepped up action on adaptation

People are increasingly exposed to longer periods of extreme temperatures, and they will likely worsen this century (Figure 3). If climate change is not mitigated, a large proportion of the northern part of the Nile Delta and Sinai will likely be lost due to rising sea levels, which will affect a large share of Egypt’s coastal population. Extreme weather events such as heatwaves, flash floods, and sand and dust storms, exacerbate the impacts of an already arid climate. A national plan to tackle extreme weather events was adopted in 2021. A joint working group led by the Ministry of Water Resources and Irrigation aims at actions preventing damage and addressing the impacts of extreme weather events on Egypt’s north coast. Several projects have been implemented to build climate resilience in coastal areas (Section 3).

Figure 3. Egypt is significantly affected by climate change and projected sea level rise

Note: Low elevation coastal zones (LECZs) are areas below 10-metres.

Sources: Left panel, IEA/OECD calculations using ERA5 Reanalysis data (Copernicus Climate Data Store) and methodology from Maes et al. (2022), “Monitoring exposure to climate-related hazards: Indicator methodology and key results”, OECD Environment Working Papers, No. 201. Right panel, OECD/European Commission (2020), Cities in the World: A New Perspective on Urbanisation, OECD Urban Studies.

Egypt is planning to complete its National Adaptation Plan in early 2025. The cost of adaptation programmes is estimated at USD 113 billion, with a funding gap of USD 94.7 billion (Government of Egypt, 2022[4]). The second updated NDC indicates USD 50 billion as conditional financing requirements for adaptation measures until 2030 (Government of Egypt, 2023[8]). The NDC does not indicate either the share of government funding for adaptation or the estimated cost of loss and damage related to climate change impacts. Adaptation projects are usually less attractive to private investors than mitigation projects (Green Climate Fund and Government of Egypt, 2022[9]). However, climate adaptation measures ultimately cost less than responding to loss and damage from extreme weather events (OECD, 2023[10]). Therefore, the government should continue to mainstream adaptation concerns into all sectors, while building capacity to tap into international climate finance.

The adverse effects of climate change increasingly affect all of Egypt’s economic sectors, in particular agriculture. Saline water intrusion already affects soil fertility in the Nile Delta (El-Kiki, 2018[11]). More evaporation will place additional pressure on scarce water resources. Rising energy demand for cooling during the summer will also affect the resilience of the energy sector (Section 3). Egypt recognises the need to mainstream climate change adaptation into all policy sectors, but implementation remains at an early stage. Mainstreaming adaptation is particularly relevant for new infrastructure projects and local development plans. Poor people generally have fewer resources for adaptation and require targeted support measures.

Air pollution is a serious health concern

In the context of Egypt’s growing population, increasing industrial activities, road traffic and congestion, emissions of nearly all air pollutants are high. Egypt met its 2020 target of reducing PM10 emissions by 15% compared to 2015 levels in the Greater Cairo area and exceeded the target in the Delta region (CAPMAS, 2023[12]). The Greater Cairo area remains an air pollution hotspot. The country still has a way to go towards achieving its goal of halving PM10 emissions by 2030 (Government of Egypt, 2023[13]). According to national statistics, annual average concentration of PM2.5 has decreased over the past decade and dropped below Egypt’s national limit value of 50 µg/m3 in 2022.

The government launched the six-year Greater Cairo Air Pollution Management and Climate Change Project in 2021. Key objectives include the modernisation of Egypt’s air quality management system, the construction of integrated waste management facilities and the rollout of electric buses (World Bank, 2022[14]). Over the past decade, the government has taken several other measures to improve air quality by regulating industrial emissions, improving solid waste management, upscaling public transport and, more recently, introducing electric buses. The government also helped establish a collection system for rice straws, preventing the burning of agricultural waste that leads to toxic emissions (black clouds) while creating new economic opportunities for farmers.

Developing an integrated air pollution reduction strategy, including timebound targets for major air pollutants, would be an important next step. The maximum limits of outdoor air pollutants, defined in Egypt’s Environmental Law no. 4 of 1994, would need to become more stringent to approach international standards (Government of Egypt, 1994[15]). The government started expanding its network of air quality monitoring stations (Government of Egypt, 2023[16]) and some stations have real-time monitoring capacity. Other stations require upgrades so they can monitor all types of pollutants. Information on air quality and related health risks will need to become more easily accessible for citizens on relevant websites or apps.

Accelerating the clean energy transition

Egypt has great potential to accelerate its clean energy transition

Fossil fuels continue to dominate Egypt’s energy mix. Oil and gas accounted for 92% of total primary energy supply in 2021, while coal represented less than 2% (IEA, 2023[17]). Renewable energy sources made up 6% (IEA, 2023[17]). Egypt has significant untapped potential for expanding renewable energy from solar, wind and hydrogen. In 2021, renewables accounted for about 12% in electricity production (IEA, 2024[18]), The share of renewables is set to grow substantially (IEA, 2023[19]). By 2030, the government aims to generate 42% of its electricity with renewable energy sources (five years earlier than initially planned). This will require modernising and upgrading transmission and distribution networks to better absorb renewables, invest in digital technology and storage infrastructure.

To further diversify its energy mix, Egypt plans to complete its first nuclear power plant in 2030 (in El Daaba, 250 km west of Alexandria). The plant aims to cover about 3% of projected power generation. Egypt joined several international initiatives to help reduce emissions related to oil and gas production (e.g. Zero Routine Flaring Initiative, Global Methane Pledge). Within COP27, Egypt’s Ministry of Petroleum and Mineral Resources organised the first “Decarbonisation Day” to highlight success stories in the decarbonisation of the oil and gas sector.2

Efforts to improve energy efficiency are under way

The Integrated Sustainable Energy Strategy 2035 sets a national goal of reducing energy demand by 18% by 2035. It counts on greater efficiency from both upgraded generation and transmission infrastructure, and new technologies. Egypt is developing its third National Energy Efficiency Action Plan. The petroleum sector developed an Energy Efficiency Strategy 2022-35 (Government of Egypt, 2023[20]) that focuses on major energy consumers. The government has started establishing energy efficiency units in ministries and plans to develop a digitalised, sector-wide monitoring system. The transport sector has untapped potential to improve energy efficiency by setting minimum fuel efficiency standards and energy labelling schemes for vehicles. Tightening energy efficiency standards of housing will help save more energy (Section 3).

Promoting sustainable mobility

Egypt needs to prevent car dependency and make its vehicle fleet cleaner

Egypt has an immense opportunity to leapfrog towards a low-carbon transport system. All new urban settlements could be developed in a more compact, transport-oriented way that guarantees easy access to transport links, including a network of safe walking and cycling routes to prevent car dependency (Section 3). However, multiple government bodies plan infrastructure, which are resulting in complex governance. Rather than focusing on individual outcomes, government entities should work together to develop an integrated nationwide sustainable mobility strategy.

As elsewhere, transport-related emissions have been growing quickly over the past decade. This growth reflects a larger population and urban sprawl that has triggered rapidly increasing demand for mobility. The sector’s CO2-eq. emissions are projected to more than double to reach between 115‑124 million tonnes by 2030 (Government of Egypt, 2023[8]). The government should consider tightening its target for reducing emissions in the transport sector, while pursuing efforts to scale up affordable, inclusive and secure public transport options.

Egypt’s vehicle stock remains comparatively small, with Cairo and Giza recording 5.2 million cars in 2022, representing nearly half of all licensed vehicles. This situation leads to traffic congestion with adverse effects on air quality, public health, climate and economic activity. Despite high urban density, walking and cycling remain marginal. Investment in active transport modes is limited in urban planning (Mousa, 2022[21]).

Egypt has taken some steps to accelerate its fleet renewal. In 2021, the country initiated a programme to encourage use of dual-fuel vehicles, which run on both petrol and compressed natural gas (CNG). This initiative features scrapping schemes designed to retire old vehicles from the road, along with incentives to facilitate conversion of vehicles to dual-fuel systems.3 By 2023, Egypt recorded 540 000 CNG vehicles and about 1 000 CNG fuelling stations (Government of Egypt, 2023[20]).

In line with the cities-first approach, the government should consider measures to enforce diesel fuel standards in Greater Cairo and other densely populated cities (Ahmed El-Dorghamy, 2021[22]). The introduction of low-emission zones in densely populated urban areas would help reduce air pollution. This would require further measures to increase the number of low-emission vehicles in the vehicle fleet.

In the absence of vehicle deregistration, one-quarter of all circulating vehicles are likely more than 30 years old (Harun et al., 2023[23]). Egypt has banned the import of second-hand passenger vehicles older than one year and implemented several nationwide vehicle scrapping programmes (World Bank, 2021[24]). However, capacity to recycle end-of-life vehicles in a safe and environmentally sound manner is insufficient and needs to be strengthened.

Electric mobility is in its infancy

The EV industry faces many challenges related to the country’s foreign currency crunch, as new EVs are offered only in US dollars. Affordability and the absence of adequate charging infrastructure represent other major barriers for promoting electric mobility. The government’s 2019 e-mobility strategy aims to increase the share of private EVs to 50% by 2040 (World Bank, 2022[25]). It launched the first domestically produced EV in February 2023, and plans to ban new sales of internal combustion engine vehicles by 2040. As in other emerging economies, use of electric two-three wheelers and a coherent network of urban buses would be more cost effective (OECD, 2023[26]).

Transitioning to a resource-efficient economy

Waste infrastructure and services need to be strengthened to address rising waste flows

Egypt produced about 251 kg of municipal waste per capita in 2021 (Government of Egypt, 2021[27]), which is less than half of the OECD average (OECD, 2023[28]).4 The waste sector contributed to 8% of total GHG emissions in 2015 (Government of Egypt, 2018[29]), above the OECD average of 3%. As in many emerging economies, significant portions of waste are not yet properly managed. Most waste goes to landfills or illegal dumping sites. Collection rates vary widely across governorates from less than 40% to nearly 100% (CAPMAS, 2023[30]).

Egypt achieved an important milestone with ratification of the Waste Management Law in 2020, which mainstreams regulations previously scattered across many laws and decrees. The law introduces measures to reduce single-use plastic bags, a dedicated fund for municipal waste collection in each governorate, a “Green Label” certification to reduce industrial waste and extended responsibility for producers. A new Waste Management Regulatory Authority under the auspices of the MoE covers a wide range of responsibilities. Master plans at governorate level will complement a national master plan for municipal waste management.

Egypt’s updated Vision 2030 aims to enhance waste management efficiency and promotes an economy-wide shift towards circularity (Government of Egypt, 2023[13]). In the second updated NDC, the government aims to reduce waste directed to landfills to 20% by upgrading its solid waste management infrastructure, increase the amount of collected waste from 55% in 2022 to 95% by 2025, and expand recycling and energy recovery rates (Government of Egypt, 2023[8]). The government also intends to turn 20% of collected waste into energy by 2026.

To achieve these ambitious targets, the government will need to increase public financial resources considerably and incentivise private investment. Beyond goal setting, the government will need to further strengthen its regulatory framework and enforce implementation. This requires better information and waste data to monitor progress towards targets. Standardised waste profiles at governorate level would be useful. Meanwhile, a digital platform could provide access to key information and promote mutual learning among municipalities.

Agriculture needs to become more sustainable, especially through reduced fertiliser use

Agricultural productivity has increased significantly over the past decade. The sector faces increasing pressure to feed a larger number of people given limited areas of arable land. Fertile agricultural land is confined to the Nile Valley and its Delta (“old land”), as well as a few oases and some arable land in Sinai. Egypt depends heavily on food imports, mainly wheat. This makes the country vulnerable to international trade disruptions as witnessed by the impacts of the war of aggression against Ukraine by the Russian Federation.

The Agriculture, Forestry, and other Land Use (AFOLU) sector represented about 15% of national GHG emissions in 2015, resulting from enteric fermentation, manure management, field residuals burning, agriculture soil and rice cultivation (Government of Egypt, 2018[29]). The updated NDCs do not include any climate mitigation measures for the agricultural sector (Government of Egypt, 2023[8]). Many governorates do not monitor key indicators from diffuse pollution from agriculture (e.g. nitrogen and phosphorus concentration).

Egypt has one of the world’s highest rates of nitrogen fertiliser use per hectare of crop. In 2021, it used on average 310 kg per ha (FAO, 2022[31]). This has major negative impacts on soil and water quality. The government foresees cutting back on use of mineral/chemical fertilisers and expanding use of organic and biological fertilisers. Rather than subsidising the use of fertilisers, policies would better focus on improving the knowledge and skills that could help farmers optimise use of fertilisers, including through extension services.

With nearly 85% of farms averaging no more than 0.6 ha per unit, land fragmentation remains an obstacle to the rollout of climate-smart technologies (Santos Rocha, 2023[32]). While much agricultural support is spent on large-scale projects, better targeting support could accelerate the transition to more sustainable and productive agriculture. Smallholders usually struggle to access financing for investments in climate resilience. Like newly created associations that benefit water users, independent associations for small-scale farmers could provide advice, mutualise investment costs and create new economic opportunities along supply chains. Awareness of quality seed and new varieties, as well as access to climate-resilient varieties, needs to be improved and promoted, for instance, through mobile applications.

Managing the natural asset base

A stronger use of economic instruments could help address Egypt’s water scarcity

Egypt is among the world’s most water-scarce countries. In the context of rapid population growth and limited availability of freshwater resources, the per capita share of water has been declining. The country is moving towards absolute water scarcity with less than 500 m3 per capita of annual water supply (FAO, 2021[33]). Current water demand largely exceeds Egypt’s available freshwater supply and is estimated to reach nearly double the available water resources by 2050 (Government of Egypt, 2021[34]). While agriculture makes up the bulk of water consumption with about three-quarters of total water use (CAPMAS, 2023[12]), the share of household water consumption is increasing rapidly.

Currently, Egyptian farmers only bear the on-farm irrigation costs and do not pay for water used in their farms (Enas Moh, 2018[35]). Economic incentives are needed to rationalise water use in agriculture, alongside measures to increase use of agricultural drainage water, rainwater harvesting and treated wastewater in agriculture (ReWaterMENA, 2021[36]). Old lands continue to apply traditional irrigation methods. Current efforts to upgrade and rehabilitate canals in the Delta regions go in the right direction. The government also pursues efforts to encourage farmers to switch to modern irrigation systems, including smart irrigation systems, which consider the degree of soil moisture, the level of salinity and temperature when calculating water requirements. Agricultural water allocation reform could help incentivise adoption of climate-smart technologies (World Bank, 2022[25]).

The 2050 Water Strategy, supported by the National Water Resources Plan 2017-2037, sets out the main goals and frameworks for water management. The Water Resources and Irrigation Law, ratified in 2021, is a major step forward to unify attempts to improve water use and protect the quality of water bodies. It includes provisions for water user associations and climate change adaptation. As in many other countries, various government entities address water issues. Much water-related data and information remain scattered across government bodies, making them difficult for the public to access.

Water quality could be further enhanced by applying the polluter pays principle

Water quality indicators for the Nile River met most of the national limits in 2021 (CAPMAS, 2023[12]). However, many governorates still lack values for nitrogen and phosphorus concentration. Access to safe drinking water has greatly improved thanks to the Haya Karima Initiative.

Over the past decade, pollution in the Nile River has decreased, thanks notably to increased control of industrial wastewater and growing wastewater management capacity. The government is reinforcing the polluter pays principle by tightening the penalty for factories whose waste discharge, whether liquid or solid, leads to pollution of waterways (Government of Egypt, 2021[34]). This would require enhanced compliance monitoring and enforcement. Egypt aims to ensure compliance with the Law of Environment for 85% of surface water subsystems by 2037 (Government of Egypt, 2021[34]).

The share of treated wastewater grew from 50% to 74% between 2015-22 (UN Water, 2023[37]). This is better than many other countries in MENA. Egypt invested in a series of mega projects to enhance its water treatment and reuse capacity (e.g. Bahr EI-Baqar treatment plant, West Delta El Dabaa plant, Elmahsama plant). At the same time, Egypt will need to speed up completion of wastewater treatment solutions in villages (Government of Egypt, 2021[34]).5

Water and sanitation services need to better reflect the full financial cost

Egypt achieved nearly universal access to safe drinking water over a decade ago and is working to ensure the sustainability of drinking water in accordance with national laws and regulations. It is also one of the rare African countries on track to achieve universal basic sanitation by 2030 (UN, 2023[38]). Much of these achievements are related to the Haya Karima Initiative. Disparities between urban and rural areas have been reduced.

The government appointed authorities to operate and manage drinking water and sewage treatment plants. This triggered several reforms to raise water tariffs for water and sanitation services (WSS) and make the sector more financially viable. A progressive water tariff system guarantees a low tariff rate to cover essential household water needs. High-use consumers pay nearly five times more on their water bills, cross-subsidising the reduced-rate bracket. Water tariffs are also adjusted to different sectors (e.g. commercial, industry, tourism).

Despite these increases, WSS tariffs do not reflect the full financial cost of services and continue to be subsidised by the government. Experience in OECD countries shows that tariffs are best designed if they manage to secure sustainable financing for service provision; complementary social measures can target vulnerable groups (Leflaive and Hjort, 2020[39]). Greater predictability and transparency of tariff increases could make them more socially acceptable (Alternative Policy Solutions, 2019[40]). Government efforts to increase cost recovery should also be informed by long-term strategic financial planning for water infrastructure investment, including climate adaptation. Raising citizens’ awareness of the value of water must also remain a priority.

Pressures on Egypt’s rich biodiversity are growing

The Red Sea is one of the world’s most important repositories of marine biodiversity, and the coastline also offers a variety of habitats. Population growth, land-use change related to urban and agricultural expansion, pollution, desertification and climate change are among the major drivers of biodiversity loss. The conversion of natural land area along coastal areas has had a large impact on coastal and marine species and habitats. Houthi attacks on cargo ships represent a new risk for oil spills and other leaks in the Red Sea as witnessed in early 2024 (Goodman, 2024[41]).

According to national estimates, over 40 species are under pressure in Egyptian coastal and marine environment, including marine mammals (17 species), marine turtles (4 species), sharks (more than 50 species), sea cucumber, special bivalves, coral reefs, mangrove trees and many birds (Government of Egypt, 2016[3]). Many fish species are in decline, mainly due to unsustainable use of marine resources and coastal pollution (e.g. marine litter). Restoration activities will be required to recover certain economically important fish species (Government of Egypt, 2016[3]). Enforcement of regulations for wildlife protection and prevention of overfishing needs to be stepped up.

While several national lists on different species exist, Egyptian scientific institutions and IUCN have not jointly adopted an official national Red List of species. Over the past decade, knowledge about the health of species and ecosystems has improved overall. Several research programmes aim to assess the status of species in terms of density and prevalence rate across Egypt’s natural habitats. Among others, monitoring activities focus on Egyptian gazelles, crocodiles, waterfowls, coral reefs, sharks and desert plants. A solid evidence-based analysis is necessary to help set priorities for conservation action plans for protection of species and ecosystems. A monitoring system to regularly update assessment criteria can further support the decision-making process.

Egypt has been committed to protecting biodiversity, but better implementation is needed across all sectors

Egypt launched its first National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan in 1998 (Government of Egypt, 1997[42]), and developed an updated strategy and action plan in 2016 covering 2015-30 (Government of Egypt, 2016[3]). The government has started another update to reflect the new commitments under the Convention on Biological Diversity’s (CBD) Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. Egypt is a party to the CBD and signed many international conventions (e.g. Ramsar Convention on Wetlands, Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals and the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, Convention for the Protection of the Mediterranean Sea Against Pollution (Barcelona Convention), African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbird Agreement and the Gulf of Aden Environment “Jeddah Convention”).

However, implementation of commitments still faces some challenges in many areas due to limited financial and human resources. Local expertise needs to be further strengthened to ensure sustainability of actions and better consider local contexts. Plans to update the legal and institutional frameworks go in the right direction. This could help create an enabling environment for implementation of the national strategy and related biodiversity conservation, sustainable use and restoration activities. In addition, economic incentives for biodiversity conservation and its sustainable use could help better protect terrestrial, marine and aquatic ecosystems on which species depend, and address the pressures on biodiversity loss.

There is an urgent need to mainstream biodiversity into all sectors. This would also help mobilise additional investment in biodiversity conservation and sustainable use measures. Efforts to accelerate its clean energy transition should be pursued without compromising biodiversity (OECD, 2024[43]). Environmental impact assessment (EIA) of renewable energy projects considers bird migration routes. The government implemented several projects to promote radar-assisted shutdown on demand of wind farms and developed new green job opportunities for female bird watchers. The government has also started working towards the expansion of ecotourism through a nationwide campaign, called ECO EGYPT. However, other sectors have struggled to integrate biodiversity concerns. For example, the agricultural sector has so far paid little attention to agrobiodiversity (Government of Egypt, 2020[44]). Therefore, Egypt should continue to raise awareness and strengthen capacity of relevant governmental agencies. It should provide economic incentives for key stakeholders to adopt ecologically sustainable management practices.

Egypt increased financial resources for protected areas and has plans to further expand marine protected areas

Egypt counts 30 protected areas, covering about 14% of its total land area, which is close to the 2020 Aichi Target of 17%. This is a higher share than in many other MENA countries. The government intends to declare the entire coral reef habitat of the Red Sea stretching over 1 800 km as protected areas through a prime ministerial degree in summer 2024. This will be a milestone given the global importance of coral reefs in the Red Sea area by raising the share of protected marine areas, currently at 5%.

For a long time, the performance of protected areas has been hampered by weak operational, administrative and management capacity, as well as by lack of trained staff and financial resources. In 2015, less than half of protected areas had proper management plans, and many were outdated (Government of Egypt, 2016[3]). However, the government revised the fee system for protected areas, especially in the Red Sea, which attracts up to 10 million tourists per year. This contributed to increasing considerably the revenue collected from entry fees of protected areas, reaching about EGP 500 million in 2023. About 25% of the total revenues of protected areas is dedicated to their management; the remainder is used for other environmental protection programmes. These additional resources allowed increasing the number of scientific staff and experts who support the management of protected areas.

At COP28, Egypt announced it will join the Blue Partnership Agreement, which supports multilateral co-operation for the development of a sustainable blue economy in the Mediterranean region. Egypt will have additional opportunities to strengthen its national commitments as host of the COP24 for the Protection of the Marine Environment in 2025. The government of Egypt has developed a marine litter management plan and aims to prevent and reduce marine litter pollution in the Mediterranean. Several voluntary initiatives are under way; local stakeholders generally drive action.

Recommendations to address key environmental challenges

Climate mitigation

Work progressively towards setting more ambitious emissions reduction targets across various sectors and raise Egypt’s contribution to face the adverse impact of climate change; further mainstream climate into various sectors using a policy mix and associated tools such as budgetary planning, and market and non-market based instruments.

Improve GHG monitoring and reporting capacity and develop a consolidated nationwide environmental and climate monitoring system; expand the capacity of CAPMAS, EEAA and other relevant institutions; develop sectoral monitoring tools; consider the establishment of an independent scientific body of climate experts.

Climate adaptation

Develop localised climate risk assessments and consider adaptation priorities in local planning systems and development plans; promote capacity building to increase implementation capacity at subnational level and strengthen local ownership.

Mainstream adaptation in sectoral strategies and action plans, including dedicated budgets for adaptation priorities; build administrative capacity to better tap into international climate and development finance, including at subnational level.

Air pollution

Formulate an integrated nationwide air pollution reduction strategy, including timebound targets for major air pollutants across governorates; raise awareness of air quality and related health impacts, and develop alert systems for citizens.

Energy

Pursue development of a robust regulatory framework and financing mechanisms with clear incentives to catalyse private investment for deployment of renewable energy sources; decommission inefficient thermal plants and pursue decarbonisation of the oil and gas sector and hard-to-abate industries, according to a planned timeline.

Make energy audits mandatory for major consumers of electricity, gas and petroleum products and develop a sector-wide standardised monitoring and reporting system; set Minimum Energy Performance Standards for industrial equipment with appropriate labelling schemes.

Sustainable mobility

Develop an integrated national mobility strategy, including intermediary targets at subnational levels (e.g. share of active transport modes and related investment levels); regularly assess nationwide progress through an annual sustainable mobility report covering key priorities (e.g. increased use of public transport and active transport modes, and related investments).

Introduce enforceable solid fuel quality requirements and vehicle emission standards; conduct pilot projects to experiment with low-emission zones in densely populated urban areas; upgrade the vehicle registration system, collect climate-relevant information (e.g. fuel efficiency, CO2/km, air quality certificates) more systematically, mandate deregistration of scrapped or unused vehicles and progressively introduce an age limit for vehicles in circulation to phase out most polluting vehicles within the next decade.

Waste

Pursue efforts to establish a nationwide waste collection system, including waste sorting at source; close unmanaged open dumps; upgrade waste management infrastructure through a stronger use of economic instruments (e.g. pay-as-you-throw and deposit-refund schemes); develop a National Information and Data Management System with accurate statistics on different waste streams and waste treatment modes to monitor progress (in line with provisions of the Waste Management Law no. 202).

Agriculture

Better target support to farmers, including economic incentives for investment in climate-smart and nature-based solutions; leverage scalable solutions in support of sustainable agriculture; reconsider input subsidies and rationalise use of fertilisers and pesticides; update the seed policy periodically and raise awareness of climate-resilient varieties.

Water

Set clear principles for water allocation to ensure sustainable use of available water resources and encourage water is allocated to higher value uses; reform agricultural water allocation and pursue efforts to modernise irrigation systems in old lands; implement effective cost-recovery mechanisms for WSS, combined with targeted measures for vulnerable groups.

Make information on water quality more easily available to water users; reduce point source effluent emissions from local communities and industry through enhanced compliance monitoring and enforcement; pursue efforts to expedite the expansion of WSS in rural areas.

Biodiversity

Expand coverage of terrestrial and marine protected areas to reflect the more ambitious targets agreed upon in the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework under the UN Convention on Biological Diversity; follow through with plans to protect the Red Sea’s coral reefs and surrounding coastal ecosystem, and monitor and assess the impact of protection measures; set up a standardised national monitoring system to improve efficacity of protected areas through better management practices.

Enhance contribution of tourism to biodiversity management and related conservation measures (e.g. tourism tax, increased entry fees for protected areas for foreigners); enforce existing laws and regulations to minimise the negative impacts of tourism on biodiversity; monitor the impact of recreational activities on fragile ecosystems, especially in coastal areas.

2. Towards green growth

Strengthening environmental governance and management

Green growth and sustainable development are high on Egypt’s political agenda

Advancing towards a green economy has received significant traction as part of Egypt’s commitment to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In 2016, the country launched its first national Sustainable Development Strategy: Egypt’s Vision 2030, which aligns national priorities with the SDGs. Several other initiatives – such as the 2016 national strategy for a green economy, sovereign green bonds, the Nexus of Water and the Food and Energy Platform – aim to advance Egypt’s green transition as a driver of investments, innovation and, in turn, new economic opportunities. Under Egypt’s green financing framework, half of public investment should be green by 2025.

To monitor progress towards implementing the SDGs, the government prepared three voluntary national reviews in 2016, 2018 and 2021, as well as localised assessment reports at governorate level. It has started mainstreaming the SDGs into sectoral action plans. The government has also established a dedicated national monitoring and evaluation system and set up a centralised co‑ordination body under the auspices of the Prime Minister’s Office. SDG focal points ensure co‑ordination at sectoral level and within the 27 governorates at subnational level.

Enforcement and co-ordination of environmental policy remain challenging

Egypt has a long-standing environmental policy and comprehensive legal framework addressing various aspects of environmental protection and natural resource management. The right to a “sound healthy environment” is enshrined in Egypt’s Constitution of 2014. The Constitution also sets for each citizen the “right to healthy and sufficient food and clean water” (Article 45). Article 46 stipulates that “the State shall take necessary measures to protect and ensure not to harm the environment, ensure a rational use of natural resources so as to achieve sustainable development; and guarantee the right of future generations thereto”. Specific provisions are set to guarantee every citizen “The right to enjoy the River Nile” (Article 44). The country will need to further strengthen capacity to enforce provisions of the environmental law and its executive regulations.

Egypt's highly centralised governance system extends to environmental policy. The country has made progress in adapting a whole-of-government approach to environmental management and sustainable development. To date, environmental considerations are increasingly integrated into many sectoral policies and implemented by different government bodies (e.g. Ministry of International Co‑operation, Ministry of Trade and Industry, Ministry of Tourism, Ministry of Agriculture and Land Reclamation, Ministry of Water Resources and Irrigation). This, however, creates growing co‑ordination challenges. The institutional framework needs to be further strengthened; policy coherence needs to be improved by better aligning environmental and sectoral policies.

Environmental impact assessment could be further improved

Although EIA was introduced 30 years ago, its effectiveness is constrained by weak technical and financial capacity, limited consideration of cumulative effects or alternatives, insufficient enforcement and lack of public participation. Environmental expertise needs to be further built through training and capacity building at all levels (e.g. structures and roles, research, staff and facilities, skills, tools). The Environmental Law no. 4 of 1994 makes a full EIA mandatory for high-risk projects as identified during a screening process. The administrative process for EIA approval has been streamlined, which considerably shortened review periods.

Strategic environmental assessment (SEA) could help Egypt better address cumulative environmental impacts and connect major projects to high-level decision making (Hossam and Hegazy, 2015[45]). However, Egypt does not have any legal provisions for SEA and has rather limited experience in this area (MER, 2019[46]). In 2019, the government used SEA as a tool to improve tourism planning and development in relation to biodiversity conservation in the Red Sea area. It is equally important to monitor estimated environmental impacts and compare them with actual outcomes over time with a view to adjusting mitigation measures.

Public participation in the EIA review process needs to be enhanced. Public hearings are only mandatory for projects with highly adverse environmental impacts (MER, 2019[46]), and should be expanded to other relevant categories. In 2024, EEAA has started publishing online executive summaries of EIA reports for highly polluting projects opening up opportunities for citizens to provide comments (EEAA, 2024[47]). These efforts to increase transparency go in the right direction and should be pursued.

Speedier permitting procedures should not undermine the quality of the review process

In 2022, the government added new measures to accelerate the issuance of licences for industrial facilities. It transferred responsibility for issuing new licences from relevant administrative units at governorate level to the Industrial Development Authority (IDA). EEAA remains responsible for issuing an environmental opinion and related environmental permits, which are mandatory within the licensing procedure. The review process was shortened to 20 business days for licences that require prior approvals (15% of total industrial activities). It dropped to seven business days for licences obtained through the notification system (85%), which is applied to industries with limited hazards to the environment. The new measures contributed greatly to accelerating the start-up phase of new businesses.6

As elsewhere, much shorter timeframes risk undermining the quality of the environmental permitting process, especially for high-risk industrial facilities. Administrative capacity and technical expertise of the permitting authorities need to be enhanced. This requires training and upskilling of staff to improve understanding of new technologies and their sustainability impact, among other priorities.

The government introduced measures to legalise unlicensed factories and facilities, also called informal economic projects. Law no. 19 of 2023 mandates IDA to grant one-year provisional operation permits to unlicensed factories. The move intends to legalise unlicensed factories to better control their environmental impacts. This example shows the need to enhance regulatory enforcement through regular inspections before infringements occur. Regularisation measures need to remain exceptional and be combined with tighter controls to enforce accountability.

Non-compliance calls for proactive inspections and stronger enforcement

The EEAA plays a key role in environmental monitoring and enforcement. The agency has a central department for environmental inspections and compliance and 17 regional branches for inspections across the territory. Regular performance assessment would help judge the effectiveness of compliance assurance activities and ultimately improve environmental outcomes. An annual assessment, for example, could report inspection outcomes, including the number of inspections, compliance rates, pollution incidents, measures of recidivism and duration. In case of violations, the environmental law forces the polluters to remedy violations and submit a time-bound environmental compliance action plan. In addition, the polluter remains legally liable for its action.

Non-compliance with environmental legislation (e.g. open burning of waste, illegal wastewater discharges in the Delta) calls for proactive inspections and stronger enforcement mechanisms. The government set up an integrated digital platform that allows citizens to submit complaints electronically. Citizens submitted more than 2 700 complaints by the end of 2023, including close to 800 environmental complaints (Government of Egypt, 2023[48]). Further digitalisation will play a key role in enhancing the compliance monitoring and enforcement system and could also help improve transparency.

Public participation in environmental decision making needs to be enhanced

Civil society played a key advocacy role in the foundation of the Egyptian environmental policy and legal framework in the early 1980s at a time when environmental concepts were largely unknown by most people in Egypt. However, civil society organisations (CSOs) play an active role in the implementation of many local projects. Local action is supported by the Small Grants Programme of the Global Environment Facility (GEF), which provides financial and technical support to civil society and community-based organisations. The MoE played a role in defending the level of this contribution to support local action.

The government has implemented several awareness-raising campaigns. These include “Live Green” to encourage environmentally friendly behaviour, ECO Egypt to promote sustainable tourism, e‑Tadweer to encourage the recycling of electronic waste or the “Return Nature to its Natural State” initiative to raise public awareness of climate change and its consequences. The government has also updated its school curriculum and prepared comprehensive educational packages for teachers in various environmental areas. These efforts can help fill the gap of environmental expertise and create a new generation of Egyptian environmental and climate experts, reducing reliance on international consultants.

Although Egypt’s Constitution guarantees civic associations the “right to practise their activities freely” (Article 75), NGOs face many obstacles, notably lack of funding and administrative hurdles. The NGO Law of 2019 shortened the review period for external funding to 60 days and abolished sanctions of incarceration. A central unit has been established within the Ministry of Solidarity to monitor NGO matters.

Environmental information and data have improved, but significant gaps remain

The monitoring capacity for air, water and soil has expanded but still requires efforts to align with international standards. Nearly half of SDG indicators are available, making Egypt one of Africa’s top performers in terms of SDG data provision. The MoE has published annual reports of the state of the environment since 2004. The Annual Bulletin on Environmental Statistics, produced by CAPMAS, includes useful environmental data and information. However, more work is needed to expand the scope of data and indicators to better support policy analysis and evaluation. It would be equally important to implement the System of Environmental-Economic Accounting. This would provide a robust basis to inform Egypt’s plans to greening its national accounts.

Environmental data and information remain scattered across various ministries. It is critical to improve data sharing between national entities, as well as between Egypt and development partners. This will require substantial upscaling of human, financial and technical resources for data management. Moreover, data and key documents such as sectoral strategies, action plans and policies should be systematically published on line.

Greening the system of taxes and charges

Egypt should prioritise a comprehensive green fiscal reform

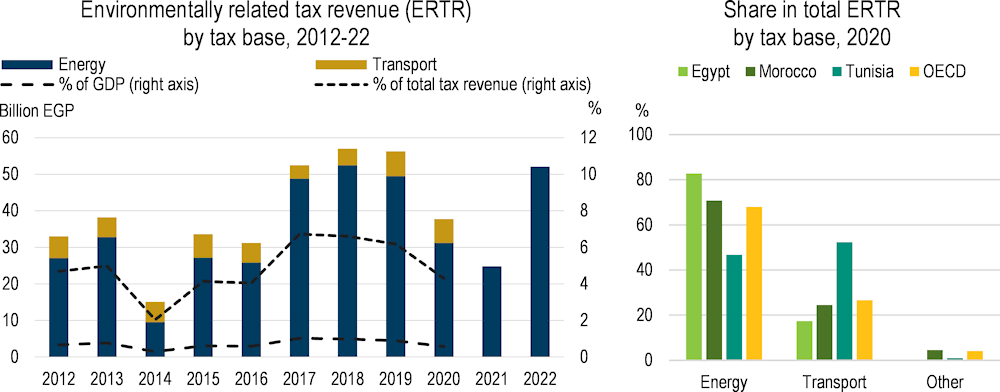

Considering Egypt’s overall low tax base, the role of environmentally related taxation in public revenues is limited, representing 0.6% of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2020 (Figure 4). As in many countries, the bulk of environmentally related tax revenue comes from energy products (83% in 2020), mainly excises on petroleum products used for transport. The remainder stems from vehicle-related taxes. Egypt has neither implemented taxes on pollution and resources nor an explicit carbon tax to directly address GHG emissions.

Figure 4. Environmentally related tax revenue has increased, but its share in GDP remains low

Note: Billion EGP (2021, real prices). For 2021 and 2022, information on transport-related tax revenue was not available as of April 2024; data points for energy-related tax revenue stem from Egypt’s Ministry of Finance.

Source: OECD (2022), “Environmental policy: Environmentally related tax revenue”, OECD Environmental Statistics (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/df563d69-en; Egyptian Ministry of Finance.

The absence of explicit carbon pricing means that fuel excise taxes are the sole mechanism, providing a direct price signal to encourage reducing fuel use and, in turn, emissions. The resulting Effective Carbon Rate amounts to 46 EGP/tCO2e, covering half of combustion-related GHG emissions, well below a conservative benchmark for a net zero-aligned carbon price of 60 EUR/CO2 (OECD, 2023[49]). Emissions that were priced mainly originated from the road transport sector, yet low rates have stalled progress in limiting the increase in CO2 emissions from road transport. Emissions from electricity production and industry sectors remain largely unpriced. Other GHG emissions (e.g. CH4, N2O, F-gases) are not priced either.

Egypt’s current fuel taxation system offers an opportunity for better alignment with climate objectives by connecting tax rates to the carbon content of the fuels. Such an approach would increase taxes on higher carbon-emitting fuels (e.g. diesel) to discourage their use, thereby applying the polluter pays principle.

Egypt has made substantial improvements in its tax policy in recent years, including far-reaching reforms of its value-added tax (VAT) and energy subsidy schemes. The government can build on these experiences to further develop its framework of environmental taxation. In addition, broadening the tax base could create new revenue streams that, in turn, could be used to unlock and accelerate green growth. For instance, Egypt could consider expanding its VAT system to cover relevant energy carriers such as petroleum products, natural gas or electricity.

Egypt has also considerable scope for expanding taxes on resources and pollution (Figure 4). Undesired distributional outcomes from increase in the cost of fuels could be offset through expansion of targeted support for vulnerable groups (e.g. increased coverage and effectiveness of the Takaful and Karama Cash Transfer programmes) (World Bank, 2023[50]). This can help support green fiscal reform and ensure its public acceptability while contributing towards the provision of reliable and affordable energy.

Efforts to reduce energy consumption subsidies need to be pursued

In MENA countries, energy support for fossil fuel consumption and production, especially for households, has been common practice for decades. This support has been offered primarily by providing businesses and households with energy products below market value. The approach has been integral to industrialisation strategies and to social policies that aim to make basic energy accessible to all and shield domestic consumers from fluctuating energy prices.

Subsidies emanating from underpricing of fossil fuels encourage excessive demand for such fuels, as well as electricity. They are also untargeted and disproportionally benefit wealthier individuals and impose significant fiscal pressures. Spending on energy support regularly exceeded revenues from energy taxes and represented a significant share of GDP. Therefore, this is not a cost-effective tool to alleviate poverty.

Fiscal costs related to these subsidies led Egypt to undertake a wide-ranging reform of its support system in 2014, which significantly reduced public spending on energy subsidies in the following years. In 2019, the government introduced a fuel price adjustment mechanism. Petroleum product prices undergo quarterly adjustments based on a pre-set and communicated formula, which incorporates the impact of international oil prices and exchange rates, ensuring transparency and predictability for consumers and businesses alike. To mitigate abrupt fluctuations, a smoothing mechanism is implemented, capping the magnitude of quarterly adjustments at 10%. This approach aims to strike a balance between reflecting changes in global market conditions and providing stability in local fuel prices.

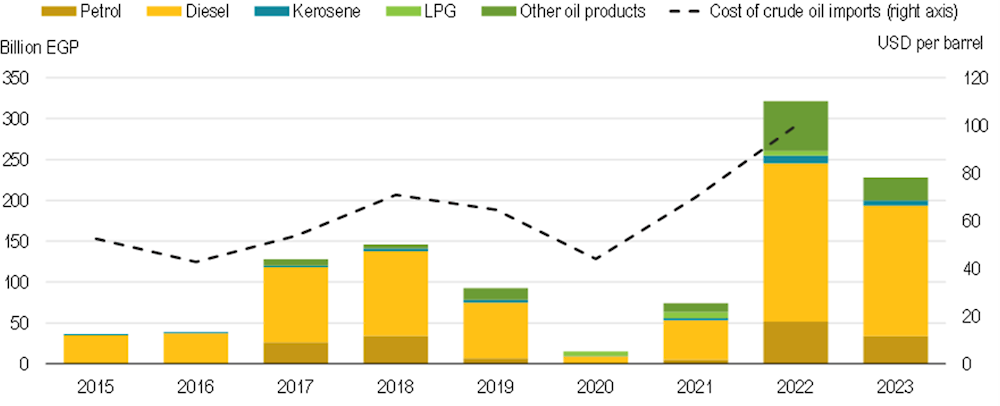

Figure 5. Egypt’s petroleum subsidy expenditure fluctuates with global oil prices

Note: Billion EGP (2021, constant prices); LPG: liquified petroleum gas; cost of crude oil imports is calculated as the unweighted average of average annual cost of total crude imports across 26 exporting countries.

Source: IMF (2023), IMF Fossil Fuel Subsidies Data: 2023 Update; IEA (2024), “Crude oil import costs and index”, IEA Energy Prices and Taxes Statistics (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/eneprice-data-en.

Despite these efforts, Egypt’s petroleum subsidy expenditure fluctuates with global energy price. Subsidies decreased substantially in 2020 as a result of lower international oil prices and a lower consumption level to 0.3% of GDP. However, they surged again driven by a strong increase in petroleum prices on international markets and a rebound in domestic oil consumption, reaching 5.7% of GDP in 2022 (Figure 5). Diesel consistently accounts for the largest share in petroleum subsidies (70% in 2023).

Egypt needs to implement cost-reflective energy pricing

Egypt's increasing electricity demand underscores the urgent need for fully cost-reflective energy pricing. Between 2014 and 2019, Egypt comprehensively reformed the power sector to restructure electricity price-setting mechanisms and responsibilities. This enhanced the role of the country’s independent power sector regulator, which recommends tariffs based on a newly developed “Cost of Service” methodology. However, the regulator’s recommendations are not binding. Despite these efforts at restructuring the pricing system and increases in electricity prices, Egypt did not meet its target of full cost recovery by 2023.7 Adopting a more cost-reflective pricing model would promote more efficient use of electricity, addressing wasteful consumption, as well as reducing the fiscal costs for the government.

In 2019, Egypt established a ministerial committee to review gas prices for different industrial activities every six months. It suggests price adjustments to Cabinet based on global price changes and economic and social variables. In early 2024, applicable gas prices for the industrial sector had not been updated for at least a year (Gas Regulatory Authority, 2024[51]).

Shifting to an energy pricing system that accurately reflects costs of electricity and natural gas production and supply is crucial for Egypt’s environmental performance, energy security and long-term economic growth. In light of recent spikes in electricity demand, transitioning towards full cost recovery becomes ever more pressing.8 Ensuring a reliable and affordable energy supply for all citizens should remain a priority. Therefore, Egypt could consider options to expand and increase the efficiency of social protection measures for vulnerable consumers.

Egypt is advancing a voluntary carbon market

Egypt’s involvement in voluntary carbon markets, demonstrated by the establishment of a carbon trading platform within the Egyptian Stock Exchange, represents a positive step towards engaging the private business sector in climate action. This initiative aims to facilitate the trading of carbon emissions reduction certificates, encouraging Egyptian companies to invest in GHG mitigation projects. The potential of Egypt’s voluntary carbon credit market is highlighted by its active promotion of GHG mitigation projects and establishment of the EgyCOP investment fund in 2022. Egypt is fostering a domestic market for carbon offsets. The Egyptian Financial Regulatory Authority has issued carbon credit verification and certification standards for issuing voluntary carbon certificates. Ensuring the environmental integrity and high-quality of offsets in voluntary carbon markets more generally remains a great challenge and can undermine the viability of such an approach for reducing emissions.

Vehicle taxation should be better aligned with the polluter pays principle

Egypt has significant scope for expanding vehicle-related taxation for environmental purposes. In the fiscal year 2019/20, revenue generated from vehicle-related taxes and fees, excluding VAT, import tariffs and schedule tax, reached about USD 367 million. This represents approximately 0.75% of Egypt's total tax revenues, less than levels observed in Morocco or Tunisia (Figure 4). Vehicle taxation in Egypt is complex, encompassing various taxes and fees on different types of vehicles throughout their lifecycle (from import to annual use). These taxes primarily aim to raise government revenue, but they can also encourage adoption of environmentally friendly vehicles. Beyond import taxes, vehicles face schedule taxes, which are specific rates based on vehicle type, age and engine capacity.9

As in many countries, transport-related and fuel taxes do not fully account for the societal costs associated with environmental harm due to road usage, GHG emissions, air pollution, traffic congestion, and road wear and tear. Therefore, Egypt’s transport-related taxes would benefit from a thorough review and adjustment to better consider externalities linked to road use and pollution. For example, Egypt could consider introducing a climate component in vehicle taxation. Through a feebate system, vehicles with high CO2 emissions or poor fuel efficiency (low fuel economy) pay a fee. Meanwhile, those with low CO2 emissions or better fuel efficiency (high fuel economy) receive a rebate. Such a system can be revenue-neutral to avoid adding a burden to public finances.

Egypt could also further increase the use of road pricing to make drivers pay more directly according to use and environmental damage. Road tolls are relatively well developed, but no congestion pricing is in place. Some urban tolls have been introduced, mainly in new cities. As the central government in Egypt collects nearly all taxes, this leaves little opportunity for local authorities to collect transport-related taxes and charges at subnational levels.

Promoting green investment

Egypt has an ambitious green financing framework and climate investment plan

The government is committed to creating an investment-friendly climate to support a green transition.10 Egypt has become the first MENA country to issue a sovereign green bond in 2020 with a value of USD 750 million in 2021 (Government of Egypt, 2021[52]).11 Under its green financing framework, the government defined sustainability criteria to prioritise green investment. It aims to allocate 50% of public investments to green projects in the fiscal year 2024/25 and to achieve 100% by 2030 (Government of Egypt, 2023[53]). Efforts could be further supported by setting climate-specific objectives for state-owned enterprises to ensure that public assets and investments comply with climate change requirements, including disaster and risk assessments. Corporate social responsibility reports should be enhanced.

Egypt’s Climate Investment Plan outlines priorities for low emissions and climate-resilient development (GCF, 2022[54]). The government also established the Renewable Energy Financing Framework to unlock Egypt’s renewable energy potential (GCF, 2017[55]). Between 2015 and 2022, Egypt attracted over USD 40 billion in international finance for renewable energy ranking among the top ten development economies. This makes it the second most popular host country for renewable energy projects on the African continent, after South Africa (UNCTAD, 2023[56]).

Green investment could be better prioritised when providing corporate income tax incentives

Corporate income tax (CIT) incentives aim to reduce business investment costs and shape investment choices, including for the innovation and adoption of green technologies. However, they may lead to significant forgone tax revenues and economic distortions. This may generate limited investment and be largely redundant (subsidising investments that would have taken place without support), especially if poorly designed.

In 2018, Egypt introduced a Special Incentive, which allows deductions of 30% or 50% of investment costs. The Special Incentive targets expenditures rather than income, which is a positive feature. Expenditure-based incentives reduce investment costs more directly and are thus considered more effective at incentivising investment than income-based incentives. Renewable energy and green manufacturing sectors, including machinery producers, can use the Special Incentive. In March 2022, the Special Incentive was expanded to include projects of strategic interest, namely green hydrogen and green ammonia, waste management, e-mobility and alternatives to single use plastic.

The Special Incentive is also available for non-green projects, so it may not specifically encourage green investment. Providing incentives to both green and non-green segments in the same market may weaken the preference for green investments.

Egypt should define criteria for Special Incentive approval more precisely. Currently, a committee decides on a case-by-case basis, involving discretion. A rules-based system, potentially using a points-based evaluation may enhance transparency, despite added administrative costs. Focusing CIT incentives on green and energy-efficient technologies could better align investment decisions with Egypt's climate goals and limit revenue forgone. This would also increase the competitiveness of energy efficiency initiatives.

Renewable hydrogen offers new opportunities

Egypt aims to become one of the largest exporters of low-carbon hydrogen. Its National Strategy for Low Carbon Hydrogen, approved by the Supreme Energy Council in February 2024, aims to reach a tradable share of 5-8% in the global hydrogen market, a reduction of 40 million tonnes of CO2-eq. emissions per year and an estimated GDP increase of USD 10-18 billion by 2040. At the same, it seeks to create more than 100 000 jobs along the supply chain (Ahmed, 2023[57]). Egypt will need to strike the right balance between low-carbon hydrogen exports and domestic demand to advance local decarbonisation priorities.

Egypt has attractive regulations for investing in low-carbon hydrogen production.12 The National Council for Green Hydrogen and its Derivatives aims at fostering a competitive, investment-friendly business climate (Government of Egypt, 2023[58]). By mid-2023, Egypt had signed 8 framework agreements and nearly 30 memoranda of understanding for a project pipeline estimated at USD 83 billion (Parkes, 2023[59]). As elsewhere, most planned projects have not yet reached final investment decision.

While Egypt has a competitive advantage in producing and transporting low-carbon hydrogen, scaling up production faces several challenges related to affordable financing, technological expertise, infrastructure development and stable policy. To gain investor confidence, Egypt will need to define a transparent certification process for low-carbon hydrogen13 and its derivatives. Securing demand is among the most critical factors to support the early stage of low-carbon development projects. Therefore, a clear signal from major import markets such as the EU, would help unlock private sector investment.

Environmental and safety concerns need to be carefully considered in EIAs. Hydrogen export projects should not place additional strain on already scarce resources such as water, energy and habitable land (Dagnachew et al., 2023[60]). In this regard, seawater electrolysis could be an interesting option. However, this technology is not yet mature and may require more energy-intensive processes (Dargin, 2023[61]). It will also be important to further develop local expertise.

Recommendations on green growth

Improving environmental governance and management

Pursue efforts to enhance administrative capacity and technical expertise of the permitting authorities; strengthen capacity of EEAA and of competent administrative authorities with executive powers in the EIA process; enhance linkages with environmental enforcement agencies; require meaningful public participation in all EIAs.

Make the use of SEA mandatorily to integrate environmental considerations into policies, plans and programmes, evaluate the interlinkages with economic and social considerations, and analyse cumulative environmental impacts.

Increase financial resources to promote compliance focusing on small businesses; introduce annual reports of inspection outcomes (including the number of inspections, compliance rates, pollution incidents, measures of recidivism and duration) and make inspection reports publicly available; accelerate digital transformation and open public access to EIA reports and other compliance-related information.

Work towards strengthening Egypt’s Environmental-Economic Accounting using international standards (System of Environmental Economic Accounting); consolidate public sources of environmental information and data; make access to data more user-friendly; engage citizens more actively in environmental decisions at local levels.

Greening the system of taxes and charges

Advance the just transition from fossil fuels in energy systems through robust and transparent automatic fuel price adjustment mechanisms for petroleum products and pursue efforts to reach full cost recovery of energy production and supply. In parallel, continue to pursue the expansion, and increase the efficiency, of social protection programmes.

Ensure the environmental integrity of the voluntary carbon market and assess the pros and cons of introducing a compulsory carbon market.

Consider the introduction of pollution taxes and charges; conduct a comprehensive reform of the transport-related tax system to make it environmentally and fiscally sustainable; introduce a climate component in vehicle taxation; increase the use of road pricing (e.g. nationwide toll system, urban toll rings; parking fees in urban areas).

Promoting green investment

Monitor information on the share of green investment in public investment plans to track progress towards national targets; set climate-specific objectives and align investment of state-owned enterprises with Egypt’s climate agenda.

Align corporate income tax incentives with environmental outcomes; prioritise green investment and energy-efficient technologies under the Special Incentive to increase the comparative advantage for clean technologies; clarify approval criteria of the Special Incentive and evaluate its impact on the uptake of clean technologies.

Enforce mitigation measures for low-carbon hydrogen export projects based on EIAs and make sure that energy and water requirements are met without compromising domestic use; prevent the depletion of natural resources; invest in developing local expertise along the hydrogen supply chain.

3. Building climate-smart, resilient and inclusive cities

Enhancing urban governance

Cities can play a pivotal role in supporting Egypt’s green transition but face multiple challenges

Cities are the engines of Egypt’s growth and among the largest contributors to the country’s GDP, estimated at 75% (UN-Habitat, 2024[62]).14 They can support Egypt’s green transition by stimulating urban economic activity, green innovation, jobs, skills and more inclusive development. About 80% of employment occurs in Egyptian cities (UN-Habitat, 2024[62]). At the same time, cities are also major sources of pollution. They need to contribute more strongly to national climate mitigation efforts. Moreover, the effects of climate change in urban areas are increasingly visible. Egyptian cities are exposed to multiple climate-related hazards, especially heatwaves, flash floods, dust storms and sea level rise for coastal cities (Goyal and Sharma, 2023[63]). It is vital for Egyptian cities to strengthen climate resilience and protect the most vulnerable populations.

In the face of multiple opportunities and challenges, the government has set a new ambition to build climate-smart, resilient and inclusive cities in line with Egypt’s Vision 2030. These three dimensions are overlapping and mutually reinforcing. For example, green spaces contribute at the same time to climate mitigation and adaptation efforts while making cities more liveable for citizens.

Egypt’s fast-growing population is projected to reach 160 million people in 2050, doubling its population compared to 2010 levels (UN, 2022[64]). Specifically, the Greater Cairo area and Alexandria have been growing at a fast pace. Most of the Egyptian population is concentrated in urban areas on about 10% of the territory, mainly along the Nile Valley and its Delta, and to a lesser degree around the Suez Canal. Given the limited availability of habitable land, some agglomerations are among the world’s densest with more than 20 000 inhabitants/km². Greater Cairo hosts with about 23 million inhabitants nearly one-quarter of Egypt’s population, making it one of the world’s largest metropolitan areas (OECD/European Commission, 2020[65]). Every year, the population increases by at least 1.6 million people (CAPMAS, 2020[66]), placing additional strain on already scarce natural resources, housing and public services.

Current urban policies have been unable to keep pace with population pressures, which has led to uncontrolled urban expansion, environmental degradation and precarious living conditions. Informal and unplanned expansion absorbed most of the demand for affordable housing close to city centres. Meanwhile, many new urban communities (NUCs), built on desert land adjacent to existing cities designed to accommodate the increasing urban population, struggle to attract new residents (Zaazaa, 2022[67]). Addressing Egypt’s chronic shortage of affordable housing remains a key challenge. Egyptian cities also face increasing challenges with waste management, air pollution and wastewater discharge.

In 2023, the government adopted a National Urban Policy (NUP), which aims to promote positive transformative change in cities.15 The NUP could play an important role to better manage urban growth and make cities more competitive and liveable. It proposes a new urban system based on six clusters of cities acknowledging different paces of urbanisation (UN-Habitat, 2024[62]). It will be key to integrate sustainability aspects in all NUP measures and establish sustainability criteria to monitor progress. It is equally important to rapidly develop action plans, accompanied with adequate finance and institutional mechanisms, to ensure effective implementation of the NUP.

Administrative reforms are needed to better consider the rural-urban continuum