This chapter looks in more detail at how development finance is allocated by bilateral Development Assistance Committee (DAC) donors. It discusses the main recipient country categories and regions, including the specific situation of small-island developing states (SIDS) and fragile contexts; trends in marine and terrestrial biodiversity investments; the main sectors targeted by interventions; cross-cutting issues, including climate change, desertification, gender equality and capacity development; as well as official development finance for illegal wildlife trade (IWT) and indigenous peoples and local communities (IPLCs). For each of these areas, the chapter provides information on bilateral DAC donor trends using full values, that is, using the donor data figures as these were reported to the OECD.

A Decade of Development Finance for Biodiversity

3. A deeper dive into key areas of development finance for biodiversity

Abstract

Middle-income countries with biodiversity hotspots receive the most biodiversity-related bilateral official development finance (ODF)

While the global decline of biodiversity affects all countries, biodiversity and pressures on biodiversity are unequally distributed around the world (Arlaud et al., 2018[1]). Many of the world’s biodiversity-rich areas are located in developing countries, whose economies tend to depend disproportionately on intact, viable ecosystems (IPBES, 2019[2]). These countries are not always able to prioritise biodiversity-related concerns in a context of other pressing development priorities (Arlaud et al., 2018[1]). Even within developing countries, however, biodiversity is not evenly spread: it appears that most mega-diverse countries are highly concentrated in middle-income countries (MICs) and SIDS. Hence, addressing global biodiversity loss does not only require meeting global funding needs, but also delivering this finance to biodiversity hotspots (Tobin-de la Puente and Mitchell, 2021[3]).

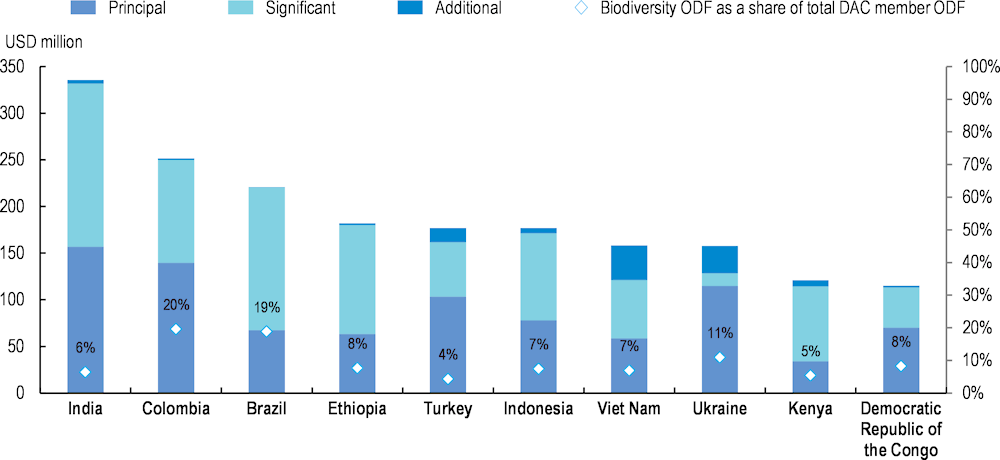

Looking at Figure 3.1, the top six recipients of bilateral biodiversity-related ODF are India, Colombia, Brazil, Indonesia, Ethiopia and Türkiye, which account for 23% of total biodiversity ODF. Among the top 10 recipients are countries that include biodiversity hotspots (Conservation International, n.d.[4]); have relatively high levels of dependence on nature (e.g. one-third of India and Indonesia’s GDP derives from sectors that are highly dependent on nature (Arlaud et al., 2018[1]); and are among the countries with highest global biodiversity decline scores, e.g. Indonesia, Malaysia, Papua New Guinea, China and India (Waldron et al., 2017[5]). Biodiversity-related interventions are particularly relevant in other countries, notably Saint Lucia, Democratic Republic of Congo and Guyana, where they represent 45%, 35%, and 30% of total ODF investments respectively.

Figure 3.1. Top recipients of Development Assistance Committee (DAC) members’ biodiversity-related development finance

Note: This analysis excludes unspecified and regional allocations which accounted for USD 2.7 billion or 35% of total bilateral biodiversity-related outflows.

Countries are expected to suffer acutely from the global decline of biodiversity and ecosystem services. For example, biodiversity loss is expected to reduce the GDP up to 10% by 2030, depending on the income level (World Bank Group, 2021[6]). The literature has noted that flows have generally been well-targeted to countries with greater conservation needs (Miller, Agrawal and Roberts, 2013[7]); (Drutschinin and Ockenden, 2015[8]). In fact, LMICs receive 39% of bilateral funds for biodiversity and 31% of multilateral funds, while UMICs receive 27% and 43% respectively. Nonetheless, development finance for biodiversity out of total ODF remains low, irrespective of the income levels (5-7%).

Meanwhile, Least Developed Countries and Low Income Countries, which have been prioritised by the CBD (CBD, 2020[9]) and which have fewer hotspots, have received 34% of bilateral funds and 25% of multilateral funds – this is slightly below overall bilateral (37%) and in line with multilateral (24%) ODF trends. Yet, these countries have a lot to lose from the collapse of biodiversity and their ecosystems (World Bank Group, 2021[6]). In addition, these countries are characterised by weak environmental regulations and capacity to benefit from their natural assets. Furthermore, they rely even more than MICs on resource-intensive sectors for development (Waldron et al., 2020[10]). They often exhibit high levels of fragility or are affected by conflict, while their physical, institutional and political coping capacities are often overwhelmed by the scale and complexity of the environmental challenges (OECD, 2022[11]; OECD, 2022[12]);. In these settings, it is estimated that ODF represents most of the biodiversity funding (Waldron et al., 2013[13]). While targeting biodiversity-related ODF to MICs is fully justified from a global public goods perspective (FAO, 2022[14]), donors cannot forget LDCs and LICs in their biodiversity portfolios as biodiversity provides the basis for their development and stability over time.

Africa and Asia are the regions benefitting most

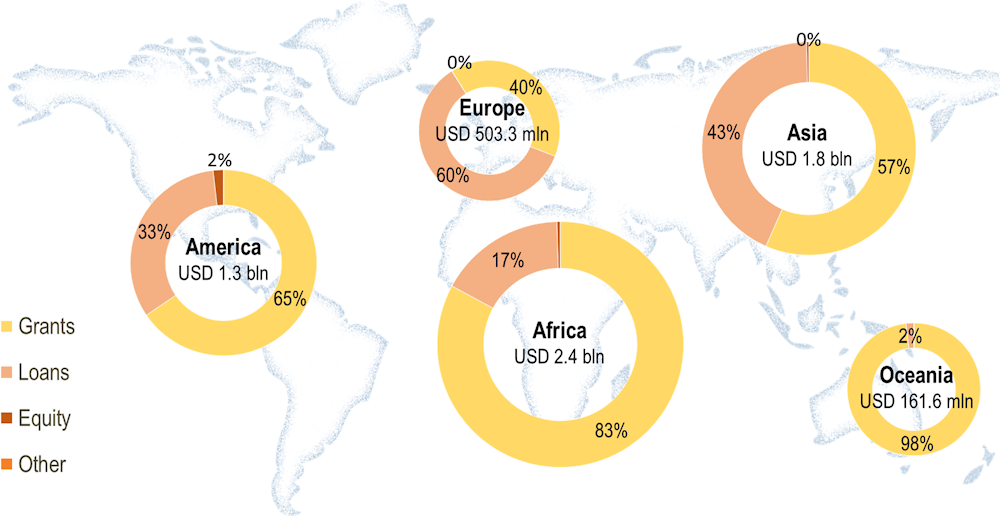

In terms of regions, Africa (at USD 2.4 billion, 39% of the total) and Asia (at USD 1.8 billion, 30% of the total) are the regions that received most biodiversity-related bilateral ODF over 2011-20 (Figure 3.2). While regional flows varied over the period, the overall trend in biodiversity-related ODF was one of increase: from USD 5 billion in 2011 to USD 7.6 billion in 2020 (with 2020 flows more than doubling 2013 values). America saw the largest increase with 128%. However, flows to Oceania and Africa decreased by 6% and 5% in 2020 compared to 2019. Africa was still the region with the highest share of biodiversity-related ODF in 2020 (USD 2.3 billion, 31%). While Oceania was the lowest (USD 297 million, 4%), it was the region experiencing the highest growth rate over 2011 to 2020 (274%). Further work is needed to understand how these trends play out in per capita or GDP per capita terms.

Figure 3.2. Africa and Asia receive most Development Assistance Committee (DAC) member biodiversity-related official development fiancé (ODF)

Note: About 21% or USD 1.6 billion of biodiversity-related ODF falls into the ‘unallocated’ category, i.e. it is not earmarked to a country or region, and so has not been included in this analysis.

In terms of financial instruments, the predominant channels used by bilateral providers are grants (68%), followed by loans (31%). Grants are predominantly used in LDCs and LICs (88% of bilateral flows), especially in Africa (83% of bilateral flows are in the form of grants) and Oceania (98% for bilateral donors). Europe is the region that receives most contributions in the form of loans (60%). In turn, while allocations to MICs tend to involve loans and grants more evenly (51% and 49%, respectively), in terms of volume, most loans are directed to MICs (84%).

Small Island Developing States (SIDS) receive more biodiversity-related official development finance (ODF) relative to overall ODF trends

SIDS have witnessed 95% of the world’s bird extinctions, 90% of reptile extinctions, 69% of mammal extinctions and 68% of plant extinctions (Arlaud et al., 2018[1]). SIDS are typically highly dependent on a single, nature-dependent economic structure to thrive, such as agriculture, tourism, and fishing, making them potentially more vulnerable to environmental degradation (Lee et al., 2022[15]). As such, SIDS are among those countries that are most directly exposed to the risk of a collapse in the ecosystem services provided by biodiversity (Nori et al., 2022[16]). This explains why the Preamble to the CBD explicitly acknowledges the special circumstances of SIDS, stating that they should be considered a priority for international biodiversity finance (CBD, 2014[17]). In turn, the SAMOA Pathway strongly supports “the efforts of SIDS to access financial and technical resources for the conservation and sustainable management of biodiversity” (United Nations, 2014[18]).

SIDS are particularly dependent on ODF, yet they experience more difficulties in accessing ODF, including for biodiversity, than other developing countries, especially grants. Among the reasons identified for this are their middle-income country status, or the need to mobilise high levels of co-financing required by existing granting mechanisms (OECD, 2018[19]). Indeed, most of ODF for SIDS takes the form of concessional loans, which are not always adapted to the needs of SIDS.

SIDS are also particularly affected by climate change and the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, while the cost of delivering assistance to SIDS is estimated to be 4.7 times higher than in other developing countries. This is due to a variety of reasons, including low human resources and data capacities, limited capacities to apply for and develop funding proposals, difficulty to understand complex fund approval systems, project management cost limitations that do not consider the relatively higher costs to operate in SIDS, difficulties to manage multiple donors and to implement and monitor projects, or low levels of private sector investment (OECD, 2018[19]). Other challenges include problems of co-ordination within government and with multilateral partners, many projects taking a project-based approach (and not creating the structural changes and capacities needed for biodiversity protection), or a regional approach (with limited local-level results) (UNDESA, 2022[20]). While many of these challenges are not unique to SIDS, they are felt more acutely in these countries and imply the need to take a strategic approach when delivering and investing ODF in SIDS (OECD, 2018[19]) – including for biodiversity.

Table 3.1 shows the top SIDS recipients of ODF from bilateral providers. As a group, SIDS received USD 275 million on average annually over 2011-20, which is 5% of biodiversity-related ODF from DAC members, and slightly above overall ODF trends to SIDS (at 4% over 2011-20). According to the OECD’s classification, SIDS that are LDCs received 37% of the total (and all in the form of grants), while LMICs received 26% (96% in the form of grants) and 37% went to UMICs (receiving 63% in the form of grants). Several SIDS countries received significant shares of biodiversity-related flows from DAC members: Saint Lucia (45% of all ODF received), Guyana (30%), Suriname (22%), Guinea-Bissau (16%), Cuba (15%), Mauritius (14%), Tuvalu (12%), Papua New Guinea (11%), and Palau (10%).

Table 3.1. Small island developing states (SIDS) are particularly dependent on official development finance (ODF)

2011-2020 annual average, commitments, USD million, 2020 prices, full values

|

Biodiversity-related ODF |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

SIDS |

USD million |

Biodiversity-related ODF as a share of ODF |

Biodiversity-related ODF as a share of total SIDS biodiversity-related ODF |

Biodiversity-related ODF as a share of total DAC member biodiversity-related ODF |

|

Papua New Guinea |

56.0 |

10.8% |

20.3% |

0.7% |

|

Haiti |

52.8 |

7.0% |

19.2% |

0.7% |

|

Mauritius |

17.7 |

13.6% |

6.4% |

0.2% |

|

Timor-Leste |

17.2 |

8.8% |

6.2% |

0.2% |

|

Dominican Republic |

16.4 |

6.1% |

6.0% |

0.2% |

|

Solomon Islands |

15.0 |

8.0% |

5.4% |

0.2% |

|

Guyana |

14.3 |

29.7% |

5.2% |

0.2% |

|

Cuba |

13.7 |

14.9% |

5.0% |

0.2% |

|

Saint Lucia |

10.3 |

45.5% |

3.8% |

0.1% |

|

Vanuatu |

9.5 |

9.3% |

3.4% |

0.1% |

Note: This figure showcases the top 10 SIDS recipients out of 33 ODA eligible SIDS recipients over 2011-20. SIDS recipients that have graduated from the DAC list of ODA Recipients have not been included in this classification (i.e. Seychelles, Saint Kitts and Nevis, and Cook Islands)

Source: (OECD, n.d.[21]).

Even though there are instances of biodiversity improving, including with the support of ODF – e.g. in Mauritius, Seychelles, Fiji, Samoa and Tonga (Waldron et al., 2017[5]) – the challenges SIDS are experiencing in accessing ODF, including for biodiversity, are hampering their ability to implement the Convention. For example, the GEF’s System of Transparent Allocation of Resources does not take into account the fact that SIDS have difficulty accessing other funds; and the GEF Biodiversity Focal Area approach may not fund activities that are pertinent to SIDS’ biodiversity goals (e.g. managing invasive alien species; managing plastic waste pollution) (UNDESA, 2022[20]). Nevertheless, as a result of GEF-8’s replenishment negotiations (GEF, 2022[22]), there has been an increasing recognition that more STAR funding should be provided to vulnerable countries (i.e. SIDS and LDCs). In other cases, reliance on concessional loans for biodiversity may exacerbate SIDS’ debt sustainability issues, with budgets already stretched due to climate-related impacts, even in high-income SIDS that no longer have access to ODA (OECD, 2021[23]). Work is being done to the methodology for updating the DAC List of ODA Recipients (e.g. reinstating countries or territories in case of catastrophic humanitarian crisis) (OECD, 2019[24]), which would ensure that certain SIDS can continue to receive biodiversity-related ODF (UNDESA, 2022[20]; IISD, 2020[25]).

Fragile contexts require more ODF to avoid the consequences of biodiversity collapse

Biodiversity hotspots and fragile contexts partially overlap – with most overlaps observable in East Africa, coastal areas of West and Southeast Africa, as well as Central America, the Himalayas and Southeast Asia (OECD, 2022[11]; OECD, 2022[26]). This overlap suggests that many fragile contexts are exposed to the multidimensional impacts of biodiversity loss and ecosystem collapse, since conflict-affected contexts suffer disproportionately from climate disruptions, environmental degradation and plundering. In turn, this overlap also suggests that many fragile contexts are key to maintaining several foundations of planetary health and security. The role they play in the fight against climate change and biodiversity loss should receive more attention, especially as nature plundering is often part and parcel of conflict and illicit economies. This relationship is equally important when understanding that fragile countries tend to attract unhealthy geopolitical interests in the race towards critical minerals necessary for the energy and digital transition, which also partially threaten the health of critical ecosystems.

Biodiversity loss fuels fragility, and in turn fragility makes it hard to adapt to the impacts of biodiversity loss (OECD, 2022[12]). Protecting biodiversity in fragile contexts will require support for complex regeneration efforts, ecosystems-based approaches, mediation and negotiation, while building resilience and addressing the root causes of fragility. Humanitarian, development and peace actors will need to draw on the right expertise to support sustainable outcomes contexts affected by environmental fragility (OECD, 2022[11]; OECD, 2022[26]).

The role of donors in this space is relevant. For example, reforestation programmes – including the Great Green Wall initiative – that engage local marginalised communities, e.g. to design law enforcement mechanisms and informal taxation (Raineri, 2020[27]), and ensure equitable resource access (Daouda Diallo, 2021[28]; CEOBS, 2021[29]) can ensure effective security and biodiversity outcomes. Similarly, peacekeeping missions or stabilisation programmes that incorporate environmental aspects, thus integrating the role of ecosystems and considering their own environmental footprint (OECD, 2022[11]); (OECD, 2022[26]), can lead to more sustainable and efficient intervention outcomes. Many DAC donors have therefore identified the importance of linking support to environmental regeneration and biodiversity conflict prevention, conflict resolution and peacebuilding (OECD, 2022[12]).

According to OECD data, USD 2 billion, or 38% of biodiversity-related ODF, targeted fragile contexts on average annually over 2019-20. This is lower than the overall ODF flowing to fragile settings (49% of total ODF targets fragile contexts). Looking at Table 3.2, DAC members mainly target with their biodiversity-related ODF contexts facing moderate environmental fragility, which is a key element of fragility, while overall ODF targets contexts that experience severe and moderate fragility, suggesting that environmental factors do not always drive ODF commitments to fragile contexts. Biodiversity-related ODF for contexts of severe environmental fragility principally went to Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mozambique and Tanzania (representing 12% of flows for environmentally fragile contexts overall) on average over 2019-20.

Table 3.2. The most environmentally fragile contexts are not always targeted by biodiversity-related official development finance (ODF)

2019-2020 annual average, bilateral commitments, 2020 prices, full values

|

Environmental fragility degree |

Biodiversity-related ODF shares |

ODF shares |

|---|---|---|

|

Severe environmental fragility |

28% |

33% |

|

High environmental fragility |

18% |

24% |

|

Moderate environmental fragility |

38% |

31% |

|

Low environmental fragility |

16% |

12% |

Note: Environmental fragility classification based on (OECD, 2020[30]); for more information on the methodology please see Annex A.

Given these trends, this report concludes that further efforts could be focused on biodiversity-related ODF for fragile settings, using the OECD’s multidimensional fragility framework to uncover risks linked to conflict and biodiversity, and building upon existing good practices, e.g. to build absorptive capacities and ensure optimal operational environments. One good example is the Fisheries Support Project (2016-24) in Mali, funded by the EU and implemented by Belgium’s ENABEL and France’s AFD. This aimed at promoting peace, including through natural resource and ecosystem management. AFD brought the conflict sensitivity component to the project to help identify the causes of conflicts linked to the governance of fishing resources, thus focusing the project on co-management of resources by a network of local fishery users (OECD, 2020[31]).

Terrestrial biodiversity is favoured over marine biodiversity

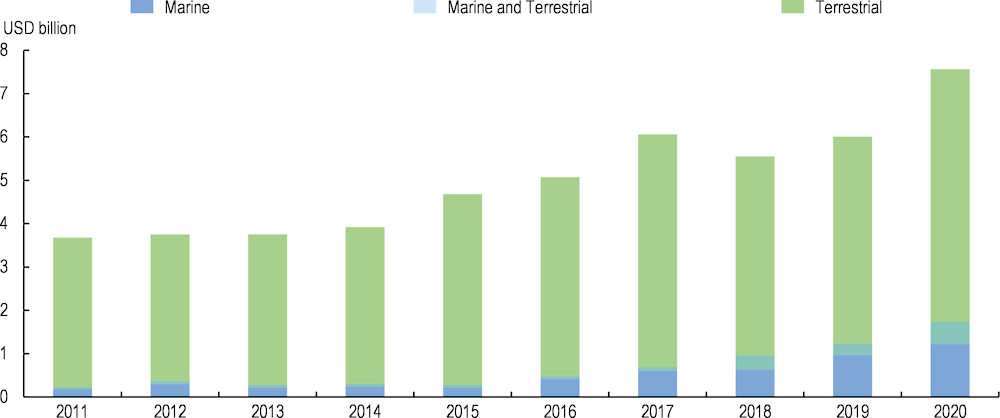

As data on ODF targeting terrestrial or marine biodiversity are not readily available through the OECD Creditor Reporting System, a specific methodology was devised for this report to understand DAC member flows to both marine and terrestrial biodiversity (Annex A). This methodology relies on a keyword search and is approximative: it only reassigns a portion of all biodiversity-related flows from DAC members into marine and terrestrial categories (65% of all flows over 2011-20). There is a pressing need for further information to track terrestrial, and, especially marine biodiversity-related ODF (Standing, 2021[32]),

The results indicate that 87% of reassigned bilateral ODF related to biodiversity is targeted at terrestrial biodiversity only (USD 4.5 billion on average over 2011-20; Figure 3.3), and mainly for agriculture and forestry. The share dedicated to marine biodiversity is small (10%, or USD 501 million on average over 2011-20), but slowly increasing, and mainly targets fisheries – as also noted by (OECD, 2020[33]). In addition, a minor share of ODF targets marine and terrestrial biodiversity together (3% or USD 160 million); this grew more than 10-fold over 2011-20. Together, marine only and marine and terrestrial ODF accounts for 13% of reassigned biodiversity related-ODF. This rise in biodiversity-related finance for marine sectors is a central component of the “sustainable ocean economy” concept (OECD, 2020[34]), and reflects the fact that many developing countries, particularly some LDCs and most SIDS, rely on ocean-based sectors, such as tourism, for income and jobs (OECD, 2020[34]). Mounting pressures on the ocean and its ecosystem services – from overfishing, pollution, and climate change, as well as new trends such as coastal darkening and the impact of wildfires on marine ecosystems – mean that developing countries are likely to face greater risks from rapidly deteriorating marine and coastal resources (Herbert-Read et al., 2022[35]). This, in turn, implies that more attention will need to be placed on ODF that can support marine biodiversity-related activities in the future.

Figure 3.3. Marine biodiversity receives a small but growing share of biodiversity-related official development finance (ODF)

Note: This figure reflects activities classified as marine, marine and terrestrial, and terrestrial, representing 65% of total biodiversity-related flows. From the remaining 35% (USD 2.9 billion), 27% was recognised as being “biodiversity-related unspecified”, and 9% could not be specified overall. Unclassified activities conform to sectors such as general budget support, education, social infrastructure and services, and tourism.

Biodiversity could be better mainstreamed into all official development finance (ODF)-dependent sectors

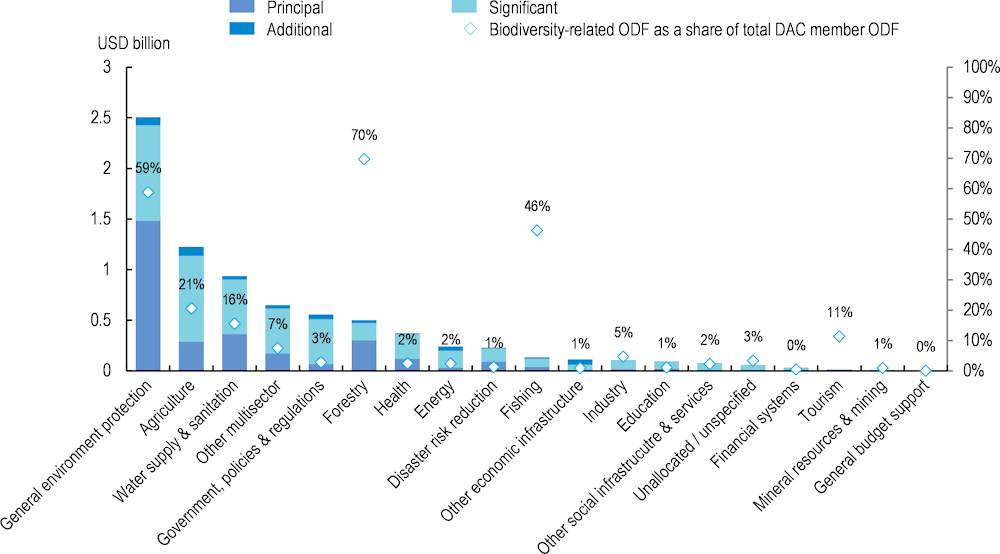

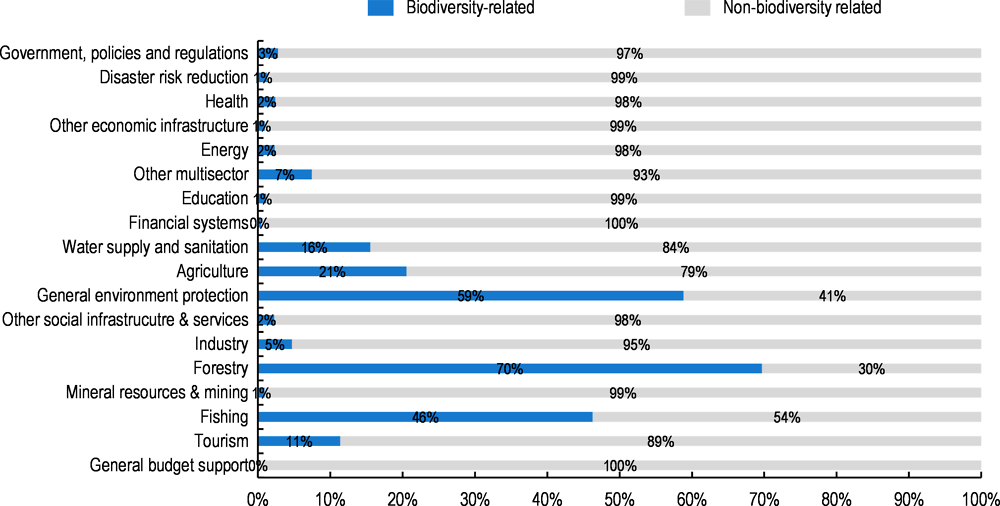

In volume terms, the main sectors targeted by bilateral biodiversity-related ODF are general environmental protection (59%, although 41% of which target the biodiversity sector itself), agriculture (21%) and water and sanitation (16%) (Figure 3.4). In most cases, activities have been mainstreamed (captured by the significant marker), except in the general environment protection and forestry sectors where they represent the core objective of the activities.

Figure 3.4. Most Development Assistance Committee (DAC) members biodiversity-related official development finance (ODF) goes to nature-dependent sectors

Note: About 1% or USD 54 million of biodiversity-related ODF falls into the “unallocated” category, i.e. it is not earmarked to a sector, and so has not been included in this analysis.

Fostering synergies between biodiversity and other cross-cutting themes is a cost-effective way of achieving sustainable development, given its multi-dimensional and integrated nature. Despite existing efforts, an urgent need remains to improve the knowledge base on the synergies among cross-cutting themes to maximise co-benefits in mainstreaming, bring biodiversity out of niche activities and have a significant impact (Milner-Gulland et al., 2021[36]). This enhanced understanding is particularly important in sectors that are dependent on nature and ecosystem services, either directly or through the supply chain, such as the agriculture, forestry, fisheries, construction and energy sectors. For example, agriculture and energy are among the largest sectors contributing to land-use change and water consumption. These sectors need to address biodiversity issues to curb possible negative biodiversity impacts (and trends) (Brörken et al., 2022[37]). However, according to the estimated figures in Figure 3.4, several nature-related sectors, such as agriculture and water supply and sanitation, have a low share of biodiversity-related representation.

Figure 3.5 shows that the sectors receiving most of the estimated bilateral ODF (including nature-dependent sectors) receive a small share of biodiversity-related ODF, pointing to the potential to further mainstream biodiversity in these areas, as well as the need for further future work to understand how that mainstreaming could be enabled. It is also important to know what is happening in these sectors, in case activities are detrimental to biodiversity objectives. This exercise would require an in-depth analysis of the entire ODF portfolio (including investments that have not been screened for biodiversity impacts, or screened but deemed not relevant to biodiversity, in the case of bilateral donors) and will not be easy to answer or depict.

Figure 3.5. Biodiversity could be far more mainstreamed into some important official development finance (ODF) sectors

Note: Sectors are organised by volume of total DAC member ODF, with sectors receiving the largest ODF contributions at the top and the lowest at the bottom. About 1% or USD 54 million of biodiversity-related ODF falls into the “unallocated” category, i.e. it is not earmarked to a sector, and so has not been included in this analysis.

The literature is increasingly framing finance through the lens of biodiversity-related or nature-related risks (Finance for Biodiversity Initiative, 2021[38]). Donors investing in some of the nature-dependent sectors could be exposed to risks of biodiversity and ecosystem collapse. If this occurred, investments would fail, and assets could end up stranded. This underlines the need to consider long-term biodiversity risks through all investments, in addition to ensuring net gain impacts in biodiversity as well as coherence between ODF allocated to other sectors and biodiversity – seeking to avoid unintentional damages to biodiversity. ODF can be used to demonstrate the value of investing in biodiversity-friendly sectors. For example, in the agriculture (IFAD, 2021[39]) or mining sector (Hoover El Rashidy, 2021[40]).

A final consideration is to ensure that biodiversity is included in assessments of policy coherence for sustainable development. Policy coherence refers to the integration of all dimensions of sustainable development (economic, social, environmental and governance) at all stages of domestic and international policymaking – which implies ensuring that domestic activities do not undermine global biodiversity. For example, in 2017, the 27 OECD countries that report data to OECD’s Fisheries Support Estimate database provided USD 700 million of direct support to individuals or companies in fisheries. About 40% of these transfers were directed at lowering the cost of inputs, e.g. through subsidies for vessel construction or modernisation, or through policies to lower the cost of fuel. OECD work has shown that such policies are among the most likely to provoke overfishing, overcapacity, and illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing. Re-directing support away from policies that incentivise more intensive fishing, towards activities that improve the sustainability of fishing operations, could have significant benefits for marine biodiversity, as well as for fishers’ livelihoods (OECD, 2020[34]).

Climate investments dominate biodiversity-related official development finance (ODF), highlighting scope for greater use of nature-based solutions

The interlinkages between climate change and biodiversity loss are complex, but the opportunities to generate financing co-benefits are starting to be better understood (Tobin-de la Puente and Mitchell, 2021[3]). Global climate regulation depends on healthy ecosystem services. Vegetation and soils, notably in forests, wetlands and peatlands, as well as coastal and marine ecosystems such as mangroves, tidal marshes and seagrass meadows, are important contributors to climate change mitigation through carbon sequestration (IUCN, n.d.[41]), and by participating in nutrient cycling – including carbon. Species-rich ecosystems are often carbon-rich ecosystems (Rainforest Foundation Norway, 2021[42]). Yet, climate change is now the third-largest driver of biodiversity loss (IPBES and IPCC, 2021[43]). Financial resources should increase benefits for both biodiversity and climate, and minimise trade-offs. Failure to do so may lead to projects targeting climate change mitigation, for example, that may be negative for biodiversity (e.g. pursuing carbon sequestration strategies that promote the expansion of fast-growing monoculture plantations in natural grasslands or tropical areas with primary forest systems, or fostering the construction of seawalls that damage coastal habitats and ecosystem services) (FAO, 2022[14]).

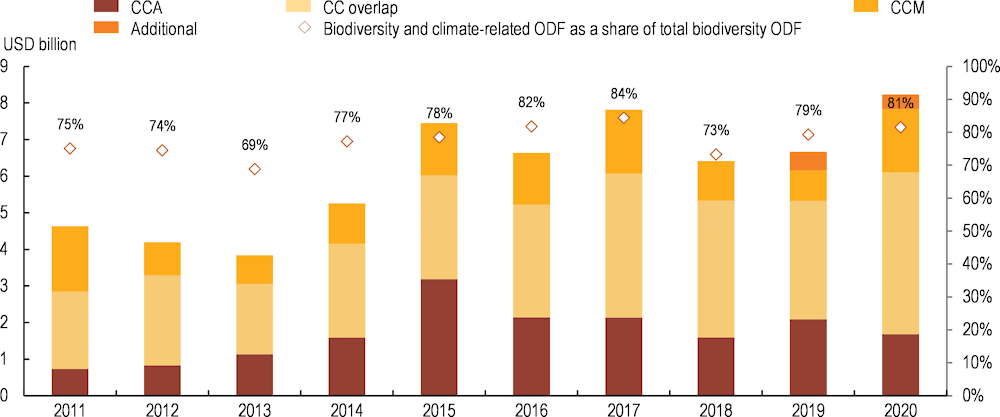

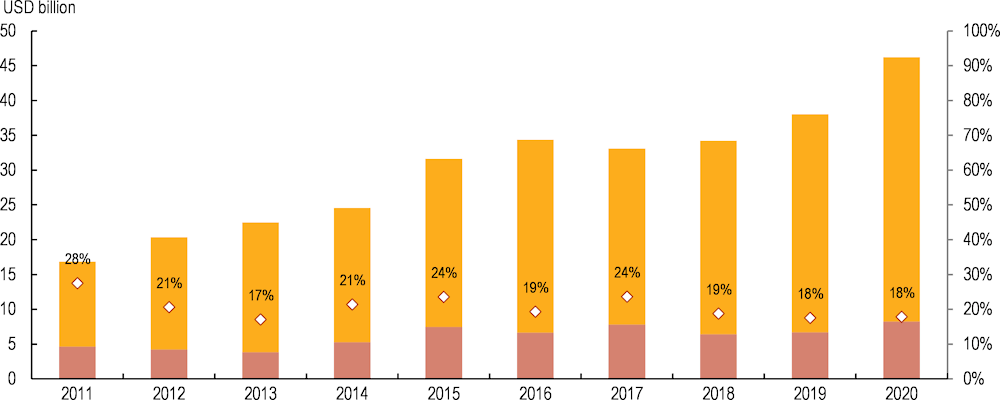

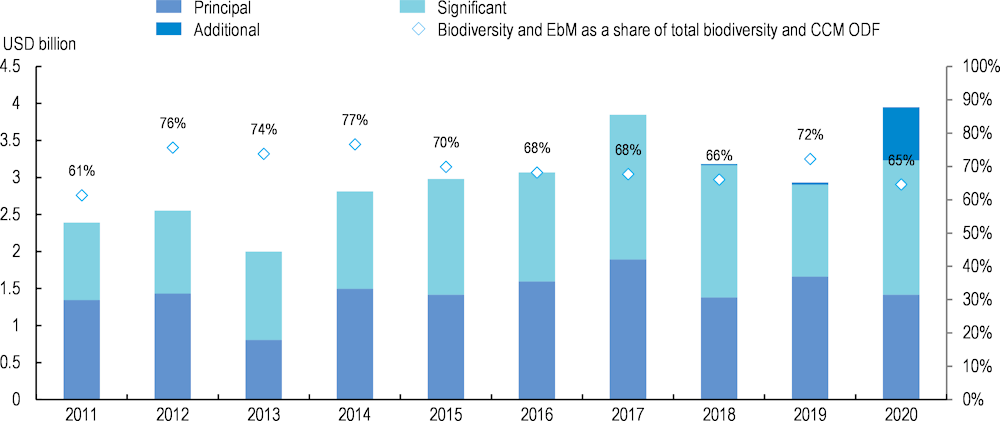

DAC donors’ investments in the area of biodiversity are mainly driven by concerns about climate change, a trend already noted by (Donner, Kandlikar and Webber, 2016[44]). Figure 3.6 shows that 78% of biodiversity-related DAC bilateral ODF also targets climate change on average over 2011-20. The value of ODF activities targeting both climate change adaptation and mitigation objectives simultaneously amounted to USD 6.1 billion annually on average over 2011-20. However, only 21% of climate-related development finance also targets biodiversity specifically on average over 2011-20 – and this share is declining from 28% in 2011 to 18% in 2020 (Figure 3.7). The rate of growth of climate integration into biodiversity-related ODF (78% growth rate over 2011-20) far outpaces the 38% growth rate for biodiversity activities being integrated into climate-related ODF. This reflects what some analysts call “climatising” nature, suggesting that activities are rarely designed to tap into climate-biodiversity co-benefits (Pettorelli et al., 2021[45]).

Figure 3.6. Climate change receives a huge share of total biodiversity-related official development finance (ODF)

Note: CCA=climate change adaptation; CCM=climate change mitigation; CC overlap=activities targeting both climate change adaptation and mitigation objectives simultaneously; additional=activities captured through SDGs 14 and/or 15 tags that could not be disaggregated by type of climate objective.

Figure 3.7. Biodiversity receives a small, and declining, share of total climate-related development finance

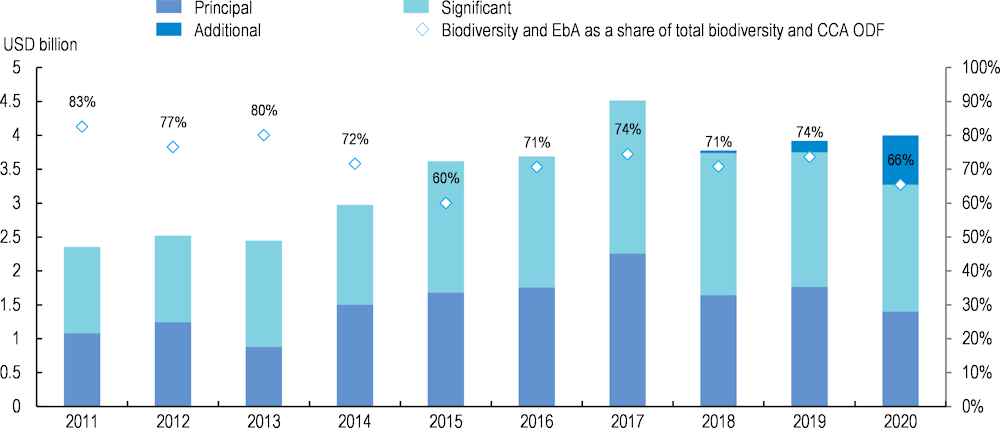

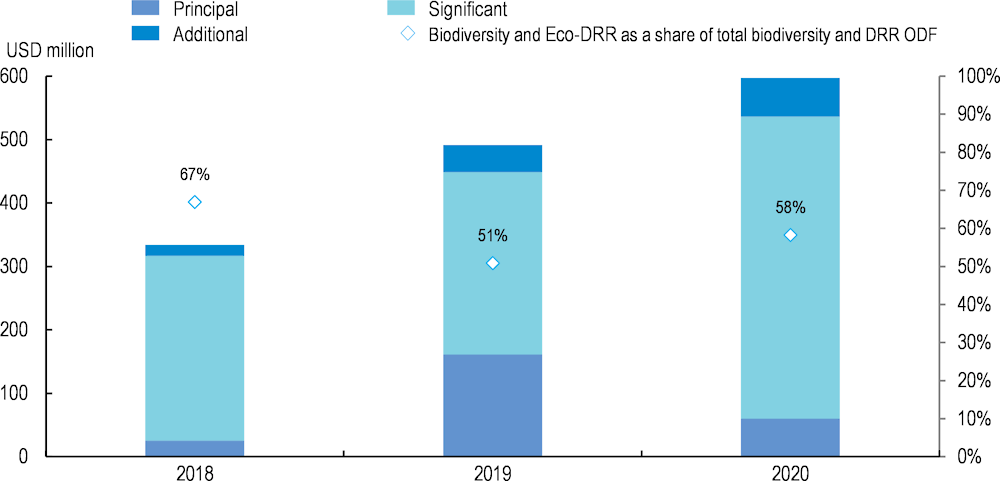

Financing nature-based solutions (Box 3.1) can support biodiversity goals (World Bank, 2008[46]; Parrotta et al., 2022[47]) and can deliver multiple benefits for human well-being (UNDP; Secretariat of the CBD; UNEP-WCMC, 2021[48]). Such solutions may be particularly relevant in lower income countries, given high dependency on local ecosystems for basic needs and livelihood strategies, and a lack of finance for technological or infrastructural approaches (Woroniecki et al., 2022[49]). Despite the growing interest in this area, there is relatively little knowledge or understanding of the flows directed to nature-based solutions (UNEP, 2021[50]), mainly due to constraints in tracking such financing (UNEP, 2021[50]; Deutz et al., 2020[51]). For this report, bilateral biodiversity-related ODF flows were classified according to their contribution to ecosystem-based adaptation, mitigation and eco-based disaster risk reduction (eco-DRR) (Figure 3.8, Figure 3.9, and Figure 3.10). These activities largely overlap with the activities that members reported using the markers system. In many cases, however, activities could not be classified as being nature-based solutions.

Box 3.1. Nature-based solutions are growing in popularity

According to the United Nations Environment Assembly, nature-based solutions (NbS) are actions that “protect, conserve, restore, sustainably use and manage natural or modified terrestrial, freshwater, coastal and marine ecosystems, which address social, economic and environmental challenges effectively and adaptively, such as climate change, while simultaneously providing human well-being, ecosystem services and resilience and biodiversity benefits” (UNEP, 2022[52]). Nature-based solutions are estimated to be 30% to 36% of the climate solution and are attracting an increasing number of investments (Griscom et al., 2017[53]), while 30% of the world’s cost-effective, near-team mitigation potential can be provided by the land-use sector by stopping deforestation, restoring ecosystems, and improving agricultural practices (FAO, 2022[14]). However, other research finds that it is likely that the available scientific literature overestimates the realistic potential of NbS for climate change mitigation (Förster, 2022[54]).

NbS for climate action can be seen as encompassing other concepts, such as ecosystem-based adaptation and mitigation (EbA, EbM), as well as ecosystem-based disaster risk reduction (eco-DRR), sharing important attributes and characteristics – namely the importance of the sustainable use of resources to ensure the integrity of natural processes and biodiversity (Terton, 2022[55]; CBD, 2014[17]; CBD, 2016[56]; Murti and Buyck, 2014[57]; Lo, 2016[58]; Luna Rodríguez and Villate Rivera, 2022[59]). While ecosystem-based adaptation refers to activities that harness biodiversity and ecosystem services to reduce vulnerability and build resilience to climate change; ecosystem-based mitigation activities use ecosystems and biodiversity to reduce greenhouse gas emissions; and finally eco-DRR approaches entail combining natural resources management approaches, or the sustainable management of ecosystems, with disaster risk reduction methods. As seen in Table 4.2, a growing number of DAC members also refer to the importance of NbS in their biodiversity-related development co-operation frameworks. Over 130 countries have included NbS in their Nationally Determined Contributions (Terton, 2022[55]; WWF, 2021[60]).

Ecosystem-based adaptation and ecosystem-based mitigation follow different paths over 2011-20, with EbA increasing in volume but decreasing in relative terms as a share of climate change adaptation and biodiversity ODF (Figure 3.8), while EbM also increased in volume but remained flat in relative terms (Figure 3.9). This is in line with previous analyses of EbA (Swann et al., 2021[61]; UNEP, 2021[50]). In turn, eco-DRR, which is the sustainable management, conservation and restoration of ecosystems to reduce disaster risk, is an emerging area for donors (UNDP; Secretariat of the CBD; UNEP-WCMC, 2021[48]); (Tyllianakisa, Martin-Ortega and Banwart, 2022[62]). The trends here show that while eco-DRR is increasing in volume, it is decreasing in relative terms, and that it is mainly targeted through mainstreaming rather than as a principal objective (Figure 3.10). Although this approach addresses climate-related events (ex. floods, droughts) and non-climate-related events (ex. earthquakes and tsunamis), it is widely used to prevent disasters caused by climate impacts (Luna Rodríguez and Villate Rivera, 2022[59]).

Figure 3.8. Biodiversity-related official development finance (ODF) for ecosystem-based adaptation has increased

Note: For further information on the methodology used to capture ecosystem-based adaptation activities, please refer to Annex A, Nature-based Solutions and Ecosystem-based Approaches.

Figure 3.9. The share of ecosystem-based mitigation in biodiversity-related official development finance (ODF) as stagnated

Note: For further information on the methodology used to capture ecosystem-based mitigation activities, please refer to Annex A, Nature-based Solutions and Ecosystem-based Approaches.

Figure 3.10. Biodiversity-related official development finance (ODF) for ecosystem-based disaster risk reduction is increasing

Note: For further information on the methodology used to capture ecosystem-based disaster risk reduction activities, please refer to Annex A, Nature-based Solutions and Ecosystem-based Approaches.

Overall, there is scope to enhance the integration of climate and biodiversity objectives across development co-operation activities. Indeed, UNEP considers that NbS are significantly under-financed: investments in NbS would need to triple in real terms by 2030 and to increase four-fold by 2050 if the twin biodiversity and climate change crises are to be tackled efficiently (UNEP, 2021[63]; UNEP, 2022[64]). To do so, donors would need to better understand the capacity and governance gaps of NbS, as well as how to integrate cross-cutting issues such as gender equality and indigenous peoples’ rights into NbS (UNFCCC, 2021[65]). They would also need to work further to implement NbS investments, in order to enhance synergies and avoid trade-offs (Terton et al., 2022[66]; Tsioumani, 2022[67]), notably through NBSAPs, NDCs and NAPs (Förster, 2022[54]). There is also scope to mobilise private sector investment (UNEP, 2021[50]; UNFCCC, 2021[65]). Some innovative solutions are already emerging, such as the UN Biodiversity Lab Maps of Hope (Box 3.2). Finally, they need to track these investments better (Nature Climate Change, 2022[68]). There is a recognised risk that NbS will not get the resources needed to deliver joined up action on climate and nature – and that countries may deprioritise these efforts as a result (WWF, 2021[60]).

Box 3.2. The UN Biodiversity Lab Maps of Hope

The UN Biodiversity Lab provides a platform where users can access global and national spatial datasets. UNDP and partners combined forces with selected countries (Cambodia, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Haiti, Kazakhstan, Nepal, Peru, South Africa and Uganda) to produce “maps of hope” that identify where NbS can safeguard essential life support areas to maintain key biodiversity and ecosystem services, including food and water security, sustainable livelihoods, DRR, and carbon sequestration. The result is a map that governments can use to harmonise nature and development policies and prioritise areas for protection, management, and restoration (UN Biodiversity Lab, n.d.[69]; UNDP, 2021[70]).

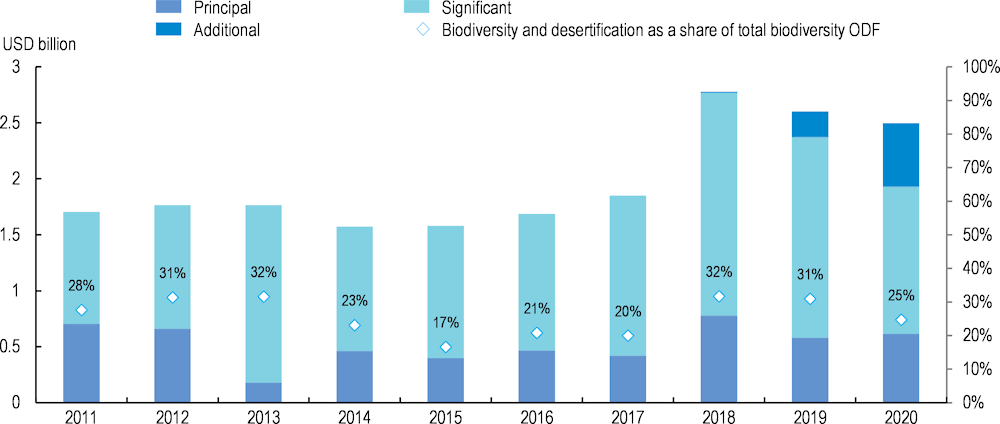

Desertification and biodiversity are increasingly targeted in interventions

Land is the operative link between biodiversity loss and climate change, and therefore is also a central element to tackle these intertwined crises (UNCCD, 2022[71]). For example, restoring degraded land and soil can halt the risk of widespread, abrupt, or irreversible environmental changes that contribute to biodiversity loss and climate change (UNCCD, 2022[71]). DAC members integrated both priorities into 25% of all biodiversity projects over 2011-20 (Figure 3.11). Funding for desertification and biodiversity-related objectives is concentrated in a few donors, with the EU (26%) and Germany (22%) providing half of the flows. Moreover, development finance for desertification and biodiversity-related purposes mostly flows to a few sectors: general environment protection (27%), agriculture (26%), other multisector (10%) and forestry (10%).

Figure 3.11. Biodiversity-related and desertification official development finance (ODF) are increasingly integrated

Note: The analysis draws on the biodiversity and desertification Rio Markers, as well as SDGs 14 and 15. For further information see Annex C.

Source: OECD (2022[72]), OECD DAC Creditor Reporting System Statistics, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=crs1.

While the overlap between biodiversity- and desertification-related ODF has been increasing over time – peaking in 2018 (USD 2.8 billion), it remains far smaller than for climate change. This is therefore an area where donors can increase their action in seeking co-benefits.

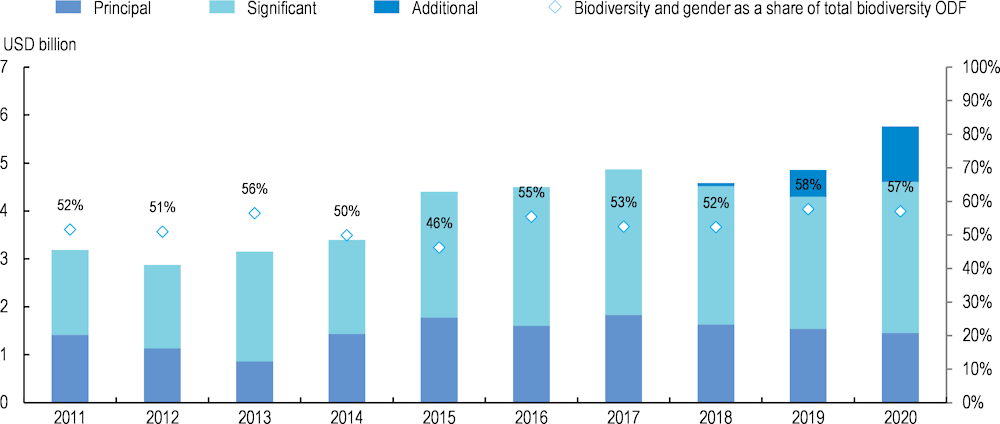

The gender equality and biodiversity nexus is an area of growing interest for Development Assistance Committee (DAC) members

Identifying and addressing gender issues in biodiversity-related ODF can add up to a multitude of benefits, such as improvements in forest management and access to water; increased capacity to carry out climate change vulnerability assessments and adaptation planning; reducing illegally caught fish; increased leadership roles for women in peace processes and environmental governance; as well as improved perceptions of women’s capacities and enhanced status, earnings and social benefits (CBD, 2022[73]). Funding that targets both gender equality and biodiversity has been increasing over time, both in absolute and relative terms (Figure 3.12). This has been primarily driven by greater uptake of gender considerations in climate activities that have biodiversity co-benefits (OECD, 2022[74]).

Figure 3.12. Biodiversity-related and gender mainstreaming is increasing in development finance

Note: The analysis draws on the biodiversity Rio Marker and the gender marker, as well as SDGs 5, 14 and 15. For further information see Annex C.

Source: OECD (2022[72]), OECD DAC Creditor Reporting System Statistics, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=crs1.

Iceland, Canada, Sweden, Luxembourg, Denmark and Ireland have mainstreamed gender considerations into over 80% of their biodiversity portfolio; and biodiversity-gender mainstreaming commitments are increasingly frequent. For example, Belgium, the EU, France, Germany, Korea, the Netherlands, Norway, and the UK recently raised their ambitions on gender mainstreaming across all programmes in their Central African Forest Initiative (CAFI, 2020[75]), while France, the EU, the GEF, Japan and the World Bank are behind the Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund, which has mainstreamed a gender dimension into its actions (CEPF, n.d.[76]). Multilateral institutions have also put forward gender equality measures to guide biodiversity-related activities, e.g. the GEF refreshed its Policy on Gender Equality in 2017 (GEF, 2017[77]; GEF, 2018[78]); the GCF approved an updated Gender Policy and Gender Action Plan (2020-23) (GCF, 2020[79]; GCF, 2019[80]); and UN-REDD intends to have gender fully mainstreamed in 50% of programme outputs by 2020 (UN-REDD, 2017[81]; UNDP-BIOFIN, 2017[82]).

DAC members could continue to look for ways to fund gender responsive national programmes, and grants specifically targeting women’s sustainable livelihoods. Innovative approaches include supporting crowdfunding by women environmental actors and making women’s participation a criterion for receiving and deciding on use of community funds. Other strategies include allocation of funds to deliver on gender actions in NBSAPs (CBD, 2022[73]). Examples of these include the project Promoting Gender-Responsive Approaches to Natural Resource Management for Peace (2016-18), supported by the Government of Finland and jointly managed and implemented by the Sudan country offices of UNDP, UNEP and UN Women (UNEP, 2019[83]); the Ghana Sustainable Fisheries Management Project (2014-21), supported by USAID, which shows that small grants can be mobilised specifically to promote innovative tools and approaches as well as gender equality and social inclusion (USAID, 2021[84]); and the Hariyo Ban Programme (2011-21) funded by USAID, which aims to increase ecological and community resilience in various biodiverse landscapes of Nepal and that, inter alia, improved gender responsive internal governance of forest groups, increased men’s and decision makers’ engagement in promoting women’s leadership, and reduced gender-based violence in natural resources management (WWF Nepal, 2017[85]).

Capacity development interventions for biodiversity are relatively small

Partner countries face the challenge of limited technical, institutional, and personnel capacity when implementing measures for reducing biodiversity loss (Stepping and Meijer, 2018[86]) and in accessing biodiversity-related development finance (CBD, 2020[87]). ODF can help cover these capacity gaps in developing countries, e.g. by supporting the compilation of natural capital accounts and applying natural capital accounts to decision making (Dasgupta, 2021[88]); developing frameworks to cease overfishing, and illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing (OECD, 2018[19]); developing national and/or sub-national strategies, safeguard systems and other pre-requisites to implement REDD+ (Parrotta et al., 2022[47]); supporting indigenous peoples and local communities to tap into and absorb more funding (Rainforest Foundation Norway, 2021[42]); or enabling forestry capacity development through partnerships with traditional knowledge-holders, training and education (FAO, 2022[14]). The literature also highlights the important needs of partner countries in training staff to collect data, develop data monitoring and management plans, and assess ecosystem services, as well as educational activities on the importance of biodiversity data (UNDP; Secretariat of the CBD; UNEP-WCMC, 2021[48]). Funding for national research bodies in developing countries that are rich in biodiversity is particularly scarce (Förster, 2022[54]).

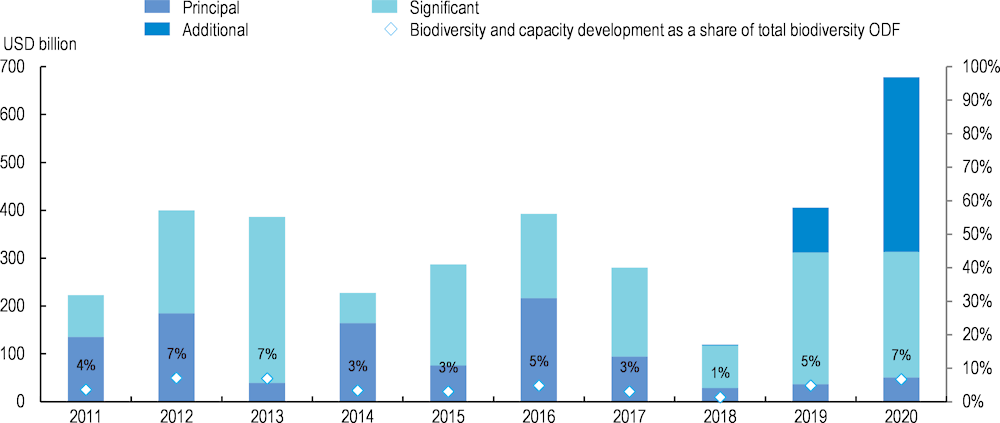

Biodiversity-related capacity development activities increased over 2011-20, both in volume and in relative terms (Figure 3.13). Capacity development for biodiversity-related activities primarily targets the provision of know-how in the form of training and research (47%), with more than half of the flows going to environmental and agricultural research in the fields of food security, soil and environmental conditions, sustainable management of ecosystems, accessing marine technical expertise and practical surveillance solutions, and sharing and improving environmental information. The next largest share goes to sector budget support (41%), with almost half the flows supporting environmental policy, administrative management and research to improve the governance and efficiency of public action in the environmental sector and support protected areas national systems. Most DAC members provide capacity development through grants (81%), with important increases in 2019-20 (67%), primarily driven by the EU, France, Australia, the Netherlands and Germany. In relative terms, Greece, New Zealand, the Netherlands and Iceland provided most of their biodiversity-related ODF through capacity development activities.

Figure 3.13. Capacity development finance for biodiversity-related objectives has increased

Note: A specific methodology was used to identify development finance targeting IWT. For further information see Annex C.

Beyond volumes spent on capacity development, ensuring that action and ambition is effective and sustainable remains a key donor challenge in development co-operation (Casado-Asensio, Blaquier and Sedemund, 2022[89]). Research shows that, in the area of biodiversity and development co-operation, donors ought to look into (a) the collaborative design of capacity development initiatives, (b) monitoring and evaluation of capacity development activities, (c) ensuring longer-term and flexible investments in this area, and (d) building strong relationships with recipients of ODF (Santy et al., 2022[90]).

Tackling illegal wildlife trade is a small, but growing, share of biodiversity-related ODF

Wildlife brings significant environmental, cultural and economic benefits to developing countries, where it can contribute to livelihoods in key sectors such as tourism. In Kenya and Tanzania, for example, wildlife-based tourism represents 12% of GDP, and makes up even larger shares of the economy in Madagascar (13.1%) and Namibia (14.9%) (World Bank, 2019[91]). Illegal wildlife trade (IWT), which is defined as the illegal cross-border trade in biological resources taken from the wild (European Commission, 2016[92]), puts pressure on several wildlife species. The global value of IWT is estimated at USD 48 to 216 billion a year, with estimated tax revenue losses of USD 7-12 billion and ecosystem services economic losses ranging from USD 881 million to USD 1.8 billion (World Bank, 2019[91]).

There is growing momentum in the international donor community to combat IWT (Djomo Nana et al., 2022[93]) and several donors plan to work in this area (Gamso, 2022[94]). A Wildlife Donor Roundtable has been in place, co-ordinated by the World Bank (World Bank, n.d.[95]), since the 2013 COP16 of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (Decision 16.5) (CITES, 2016[96]).

There is little systematic research to determine whether ODF deters IWT and IWT-related activities are difficult to identify within ODF for biodiversity. Indeed, donor engagement, including donor activities that alleviate poverty and unemployment (the two main drivers of IWT) through biodiversity-related ODF, have not always led to a reduction in IWT and appear to have had the greatest impact in countries with representative institutions (Gamso, 2022[94]). Yet, this formulation should also be noted alongside the demand/offer theory in which greater market demand also drives larger illegal trade in wildlife products (in other words, without such market, there would be no IWT).

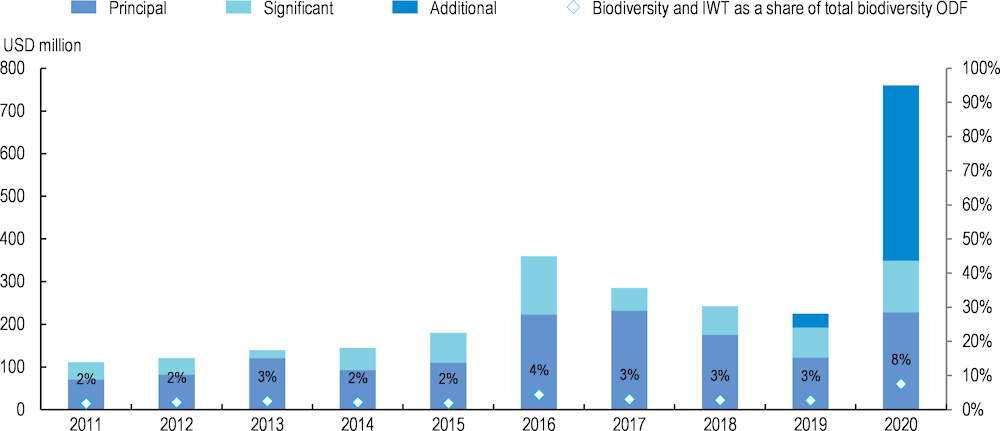

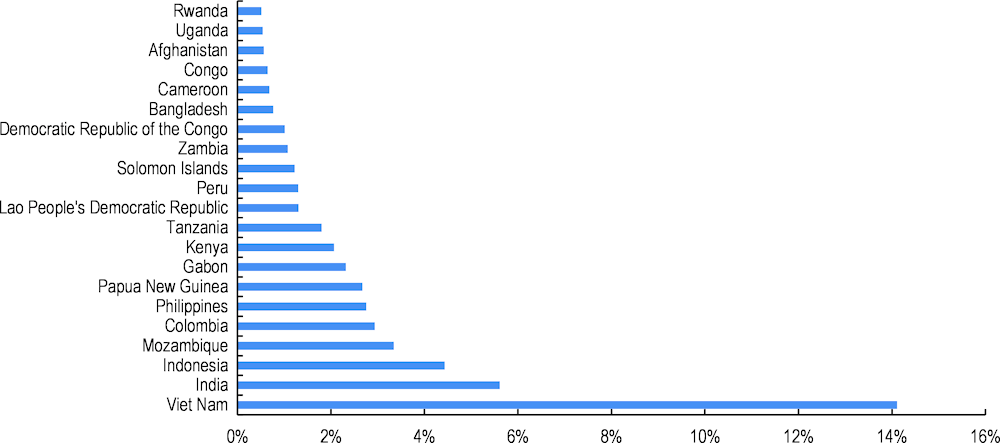

For the purpose of this report, a keyword search was applied to bilateral DAC activities identified as biodiversity-related ODF – see Annex C for further information. The findings show that support to combat IWT reached USD 257 million on average annually over 2011-20, representing 3% of biodiversity-related ODF (Figure 3.14). IWT received constant ODF investments over 2011-20 from DAC members, except in 2016 and 2020, when donors more than doubled and tripled respectively their investments, mainly driven by Japan’s investments in offshore surveillance, illegal fishing, and human-wildlife conflict. These figures are in line with those of the World Bank (World Bank, 2019[91]), which found that over 2010-18 a number of donors (including bilateral non-DAC members) committed over USD 2.35 billion to combat IWT in 67 African and Asian countries, equivalent to USD 261 million a year on average. Importantly, most activities (except in 2020) are marked as having a ‘principal’ objective under the biodiversity marker – suggesting that these activities are at the core of biodiversity-related interventions. IWT was targeted mainly by the USA (37%), Japan (20%) and the EU (14%), with flows mainly going to Viet Nam (14%), India (6%) and Indonesia (4%) (Figure 3.15).

Figure 3.14. Support to tackle illegal wildlife trade is on the rise

Note: A specific methodology was used to identify development finance targeting IWT. For further information see Annex C.

Despite notable global attention and ODF resources to combat IWT, there is scope to do more, especially in fragile settings, where IWT fuels fragility (OECD, 2022[26]; Gamso, 2022[94]). While Papua New Guinea, Mozambique, Kenya, Tanzania, Lao People’s Democratic Republic and the Solomon Islands – all of which are considered fragile (OECD, 2020[31]) – are among the top IWT-related ODF recipients, only 1% of IWT-related ODF targets fragile contexts. As discussed above, fragile settings are highly dependent on natural resources as a source of revenue and development opportunities, but often lack effective governance and law enforcement to manage these assets, which may undermine their conservation and sustainable use. Further, interventions in these contexts need to be carefully planned. For example, enhancing law enforcement efforts may deter IWT, but may also alienate local communities and exacerbate the poverty and inequality that drive poaching (e.g. through the militarisation of law enforcement) (Gamso, 2022[94]).

Figure 3.15. Viet Nam receives the lion’s share of official development finance (ODF) for combatting illegal wildlife trade (IWT)

Finally, ODF intended to support economic development may also impact and reduce IWT more than ODF specifically intended to support biodiversity and IWT. This is because ODF at large addresses the underlying factors that generate IWT such as poverty, food insecurity, illiteracy, and unemployment. Further research could investigate the broader impact and causal processes that link ODF on the underlying causes of IWT.

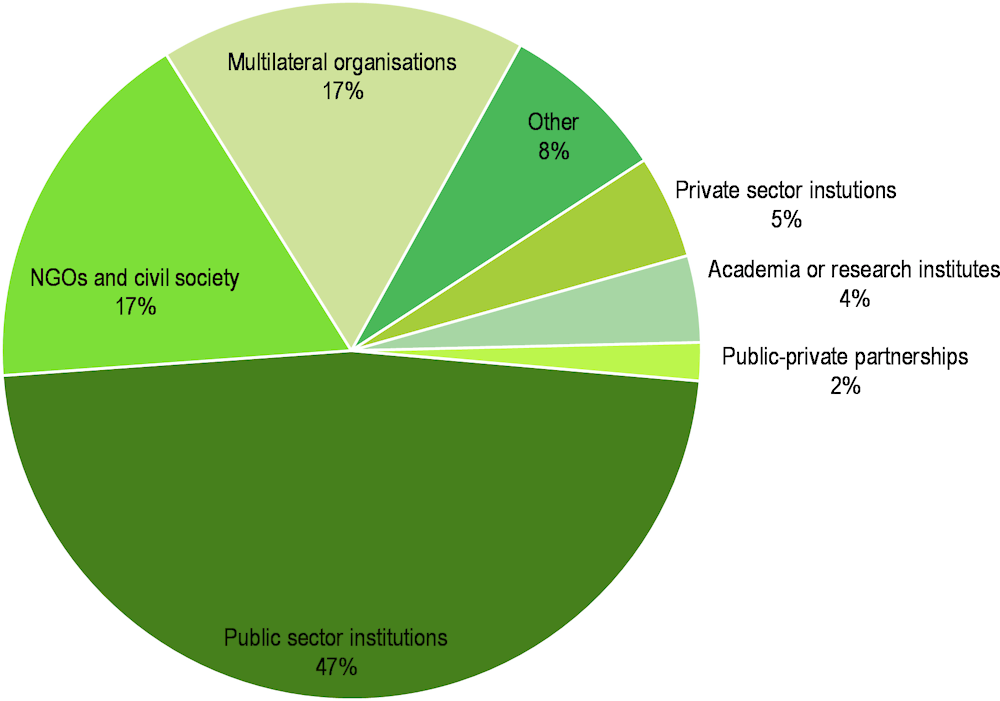

Biodiversity-related development finance is mainly channelled through the public sector

The DAC CRS includes data on delivery channels, which show that the majority of bilateral biodiversity-related ODF is channelled through public sector institutions (47%) and multilateral organisations (17%) (Figure 3.16). NGOs and civil society (17%) are also a main channel of delivery. Academia and the private sector account for 9% of these flows.

Figure 3.16. Public-sector institutions are the main delivery channel for biodiversity flows

Indigenous peoples receive little specific biodiversity-related ODF

Indigenous peoples and local communities (IPLCs) represent about 5% of the world’s population, but the land and territories indigenous people inhabit and are under their traditional stewardship contain much of the world’s biodiversity. Their stewardship of these assets and their knowledge can contribute to environmental preservation and biodiversity, notably in key biodiversity areas (WWF et al., 2021[97]; OECD, 2019[98]; Annan-Aggrey et al., 2022[99]; Estrada et al., 2022[100]). They can also help in preventing pandemics (IPBES, 2020[101]; Tsioumani, 2022[102]), and provide benefits in a range of other areas (Oliveira, 2021[103]; Loury, 2020[104]). For example, where the rights of indigenous peoples’ to manage forestlands are legally recognised, deforestation rates are lower than on land not under their management (Blackman and Veit, 2018[105]; Arnal, 2021[106]). Carbon emissions emanating from these territories are lower than those from protected areas that are not managed by IPLCs (Walker et al., 2020[107]). Further, 91% of indigenous and community lands are still in good or moderate ecological condition (FAO, 2022[14]). In fact, the collective actions of IPLCs to conserve and sustainably use biodiversity make a substantial non-financial contribution towards the goals of the CBD (Forest Peoples Programme et al., 2020[108]). Yet, IPLCs are often side-lined in biodiversity-related interventions (Parrotta et al., 2022[47]), often with dire consequences for biodiversity (Erbaugh, 2022[109]; Parrotta et al., 2022[47]).

Funding for their actions needs to be commensurate with the scale of their contributions, while safeguarding measures need to strengthen to reduce negative impacts of biodiversity-related ODF on IPLCs (Forest Peoples Programme et al., 2020[108]) and in particular to secure IPLCs in Pacific island countries. There are calls to reinforce their inclusion (WWF et al., 2021[97]), to preserve their traditions, knowledge and customs (Djomo Nana et al., 2022[93]) and, generally, to make the funding fit for purpose (Rights and Resources and Rainforest Foundation Norway, 2022[110]). Doing so can deliver great biodiversity, climate change and sustainable development results, as exemplified by Burkina Faso’s first Great Green Wall action plan, which was based on plots and species chosen in conjunction with local communities and scientific research. The potential for land restoration using this approach is estimated at over 10 000 square kilometres, which – if successful – would restore ecosystems and make the country self-sufficient in food (UNCCD, 2022[71]). Other examples can be found in (Integrated Sustainability Solutions, 2020[111]).

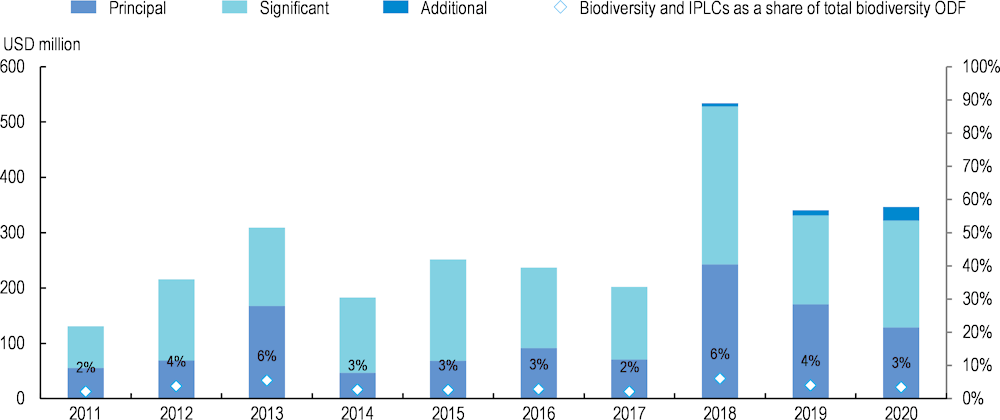

Identifying biodiversity-related ODF targeting IPLCs is not easy using the DAC Creditor Reporting System. Hence, for this report a keyword search was used to identify biodiversity-related activities (see Annex C). This found that IPLC-related projects received little ODF for biodiversity over 2011-2020, namely USD 275 million on average per year, representing 4% of DAC members’ total biodiversity-related ODF (Figure 3.17). Although not directly comparable, these amounts are in the same order of magnitude to other estimates (Rainforest Foundation Norway, 2021[42]), which found that projects supporting IPLC tenure and forest management received approximately USD 2.7 billion in total over 2011-2020 from bilateral and multilateral donors and private philanthropies (or 270 million per year on average over that period), which suggests the total might be higher than presented here.

Figure 3.17. Indigenous peoples receive a very small share of bilateral biodiversity-related official development finance (ODF)

Note: A specific methodology was used to identify development finance targeting IPLCs. For further information see Annex C.

Biodiversity ODF for IPLCs was targeted mainly to India (6%), Afghanistan (5%), Peru (4%), Indonesia (4%), Brazil (4%) and Ethiopia (4%). Belgium and Finland targeted the largest overall share of their ODF to IPLCs and biodiversity, while Germany, the United States, and Norway were the largest contributors in absolute terms. Other major donors included the EU, Sweden and Belgium. Most of these activities targeted the strengthening of tenure rights, governance and policy support, as well as broader capacity development activities. These findings are in line with those of the Rainforest Foundation (Rainforest Foundation Norway, 2021[42]). Further research would be needed to explore the effectiveness of these donor approaches in targeting IPLCs – as well as to share lessons and experiences with other providers, such as the GEF, which implemented a Small Grants Programme and Inclusive Conservation Initiative (Forest Peoples Programme et al., 2020[108]).

While a share of the funds channelled through public sector and multilateral organisations may target IPLCs (see , there are transaction costs at each step of an activity, and thus only a fraction of the funds are invested locally or are managed by IPLCs (Rainforest Foundation Norway, 2021[42]). Providing more direct funding to IPLCs could help step up action and ambition on biodiversity. However, such funding also needs to develop IPLCs’ capacity to access and absorb finance, not least to meet criteria for due diligence, monitoring and transparency, which are fundamental to the accountability of development finance – and donors themselves have limited capacities to interact with several IPLCs. Some promising initiatives have been developed, such as the World Bank’s EnABLE programme or the Forest Investment Programme’s Dedicated Grant Mechanism; or the IUCN’s GEF-funded Inclusive Conservation Initiative, which aims to deploy USD 22 million to support IPLCs to secure and enhance their stewardship over an estimated area of at least 3.6 million hectares of territories with high biodiversity and irreplaceable ecosystems.

A similar set of conclusions can be drawn for the limited amount of biodiversity-related ODF targeting civil society organisations, which have been found to lack core and flexible funding that aligns with their own strategic plans and priorities. The prevalence of short-term project funding – accompanied by difficult reporting requirements, the high cost of securing funding, and restrictions on funding eligibility – are seen as barriers for African civil society organisations in particular (Paul et al., 2022[112]); even though conservation fostered by these bottom-up or grassroots organisations tends to lead to greater compliance and project effectiveness (Quintana et al., 2020[113]).

References

[99] Annan-Aggrey, E. et al. (2022), “Mobilizing ‘communities of practice’ for local development and accleration of the Sustainable Development Goals”, Local Economy: The Journal of the Local Economy Policy Unit, Vol. 37/3, https://doi.org/10.1177%2F02690942221101532.

[106] Arnal, H. (2021), Lessons Learned to Inform Reinvestment in the Tropical Andes Hotspot, https://www.cepf.net/sites/default/files/tropical-andes-lessons-learned-2021.pdf.

[105] Blackman, A. and P. Veit (2018), “Titled Amazon Indigenous Communities Cut Forest Carbon Emissions”, Ecological Economics, Vol. 153, pp. 56-67.

[37] Brörken, C. et al. (2022), “Monitoring biodiversity mainstreaming in development cooperation post-2020: Exploring ways forward”, Environmental Science and Policy, Vol. 136, pp. 114-126, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2022.05.017.

[75] CAFI (2020), Gender Mainstreaming: New Commitments, https://www.cafi.org/news-centre/gender-mainstreaming-new-commitments.

[89] Casado-Asensio, J., D. Blaquier and J. Sedemund (2022), Strengthening capacity for climate action in developing countries. Overview and recommendations., OECD Publishing, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/development/strengthening-capacity-for-climate-action-in-developing-countries_0481c16a-en.

[73] CBD (2022), Best practices in gender and biodiversity. Pathways for multiple benefits, https://www.cbd.int/gender/publications/CBD-Best-practices-Gender-Biodiversity-en.pdf.

[87] CBD (2020), Contribution to a draft resource mobilization component of the post-2020 biodiversity framework as a follow-up to the current strategy for resource mobilization. Third report of the panel of experts on resource mobilization., https://www.cbd.int/doc/c/5c03/865b/7332bd747198f8256e9e555b/sbi-03-05-add3-en.pdf.

[9] CBD (2020), Evaluation and review of the Strategy for Resource Mobilization and Aichi Biodiversity Target 20. Summary of the first report of the Panel of Experts on Resource Mobilization., https://www.cbd.int/doc/c/4c88/dbb1/e264eaae72b86747416e0d8c/sbi-03-05-add1-en.pdf.

[56] CBD (2016), Decision COP XIII/20, https://www.cbd.int/decisions/cop/13/20.

[17] CBD (2014), Decision adopted by the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity. XII/3. Resource Mobilization, https://www.cbd.int/doc/decisions/cop-12/cop-12-dec-03-en.pdf.

[29] CEOBS (2021), Report: Groundwater depletion clouds Yemen’s solar energy revolution, CEOBS, https://ceobs.org/groundwater-depletion-clouds-yemens-solar-energy-revolution/ (accessed on 11 May 2022).

[76] CEPF (n.d.), CEPF and Gender, https://www.cepf.net/grants/before-you-apply/cepf-gender#:~:text=In%202017%2C%20CEPF%20created%20a,and%20end%20of%20their%20projects.

[96] CITES (2016), Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species COP17 Doc. 7.5. Administrative anf financial matters. Administration, finance and budget of the Secretariat and of meetings of the Conference of the Parties. Access to Finance, including GEF Funding, https://cites.org/sites/default/files/eng/cop/17/WorkingDocs/E-CoP17-07-05.pdf.

[4] Conservation International (n.d.), Biodiversity Hotspots. Targeted investment in nature’s most important places., https://www.conservation.org/priorities/biodiversity-hotspots.

[28] Daouda Diallo, B. (2021), Niger’s Kandadji Dam project: conflict concerns, Climate Diplomacy, https://climate-diplomacy.org/magazine/environment/nigers-kandadji-dam-project-conflict-concerns (accessed on 11 May 2022).

[88] Dasgupta, P. (2021), The Economics of Biodiversity. The Dasgupta Review.

[51] Deutz, A. et al. (2020), Financing Nature: Closing the global biodiversity financing gap, https://www.paulsoninstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/FINANCING-NATURE_Full-Report_Final-with-endorsements_101420.pdf.

[93] Djomo Nana, E. et al. (2022), “Putting conservation efforts in Central Africa on the right track for interventions that last”, Conservation Letters, https://conbio.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/conl.12913.

[44] Donner, S., M. Kandlikar and S. Webber (2016), “Measuring and tracking the flow of climate change adaptation aid to the developing world”, Environmental Research Letters, Vol. 11.

[8] Drutschinin, A. and S. Ockenden (2015), Financing for Development in Support of Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, http://oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/5js03h0nwxmq-en.pdf?expires=1638122323&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=88ACD466E11E82205B78808A347A2EDF.

[109] Erbaugh, J. (2022), “Impermanence and failure: the legacy of conservation-based payments in Sumatra, Indonesia”, Environmental Research Letters, Vol. 17/5, https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/ac6437.

[100] Estrada, A. et al. (2022), “Global importance of Indigenous Peoples, their lands, and knowledge systems for saving the world’s primates from extinction”, Science Advances, Vol. 8/32, https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.abn2927.

[92] European Commission (2016), The EU Action Plan against Wildlife Trafficking, https://ec.europa.eu/environment/cites/trafficking_en.htm.

[14] FAO (2022), The State of the World’s Forests 2022. Forest pathways for green recovery and building inclusive, resilient and sustainable economies, https://doi.org/10.4060/cb9360en.

[38] Finance for Biodiversity Initiative (2021), Aligning Development Finance with Nature’s Needs. Estimating the Nature-related Risks of Development Bank Investments, https://www.f4b-initiative.net/publications-1/aligning-development-finance-with-nature%E2%80%99s-needs%3A-estimating-the-nature-related-risks-of-development-bank-investments.

[108] Forest Peoples Programme et al. (2020), Local Biodiversity Outlooks 2: The contributions of indigenous peoples and local communities to the implementation of the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011-2020 and to renewing nature and cultures. A complement to the 5th Global Biodiversity Outlook, http://www.localbiodiversityoutlooks.net.

[54] Förster, J. (2022), Linkages Between Biodiversity and Climate Change and the Role of Science-Policy Practice Interfaces for Ensuring Coherent Policies and Actions, https://www.adaptationcommunity.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/02-thematic-paper-linkages-biodiv-climate-science-policy-practice-giz-iisd-ufz.pdf.

[94] Gamso, J. (2022), “Aiding Animals: Does Foreign Aid Reduce Wildlife Crime?”, The Journal of Environment and Development, https://doi.org/10.1177/1070496522113482.

[79] GCF (2020), FP135: Ecosystem-based Adaptation in the Indian Ocean - EBA IO, https://www.greenclimate.fund/sites/default/files/document/fp135-gender-action-plan.pdf.

[80] GCF (2019), Updated Gender Policy and Gender Action Plan 2019-2023, https://www.greenclimate.fund/sites/default/files/document/gcf-b24-15.pdf.

[22] GEF (2022), GEF-8 Replenishment Policy Recommendations, https://www.thegef.org/sites/default/files/documents/2022-01/GEF_R.08_16_GEF-8_Policy_Recommendations.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2023).

[78] GEF (2018), Guidance to Advance Gender Equality in GEF Projects and Programs, https://www.thegef.org/sites/default/files/publications/GEF_GenderGuidelines_June2018_r5.pdf.

[77] GEF (2017), A new Policy on Gender Equality for the GEF, https://www.thegef.org/newsroom/news/new-policy-gender-equality-gef.

[53] Griscom, B. et al. (2017), “Natural Climate Solutions”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciencess, Vol. 114/44, pp. 11645-50.

[35] Herbert-Read, J. et al. (2022), “A global horizon scan of issues impacting marine and coastal biodiversity conservation”, Nature Ecology and Evolution, Vol. 6, pp. 1262-1270, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41559-022-01812-0?utm_source=natecolevol_etoc&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=toc_41559_6_9&utm_content=20220903.

[40] Hoover El Rashidy, N. (2021), International Funding for Amazon Conservation and Sustainable Management. A Continued Analysis of Grant Funding across the Basin, https://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/515541615843979595/International-Funding-for-Amazon-Conservation-and-Sustainable-Management-A-Continued-Analysis-of-Grant-Funding-Across-the-Basin.pdf.

[39] IFAD (2021), The Biodiversity Advantage. Thriving with nature: biodiversity for sustainable livelihoods and food systems, https://www.ifad.org/documents/38714170/43873939/biodiversity_advantage_2021.pdf/73876231-652f-f55e-3286-eda9f89dcae1?t=1633526569762.

[25] IISD (2020), Papua New Guinea works to improve management of protected areas, http://sdg.iisd.org/commentary/policy-briefs/papua-new-guinea-works-to-improve-management-of-protected-areas.

[111] Integrated Sustainability Solutions (2020), Evaluation of Lessons Learned to Inform Reinvestment in the Eastern Afromontane, Indo-Burma and Wallacea Biodiversity Hotspots, https://www.cepf.net/sites/default/files/tririt-evaluation-report-4-20.pdf.

[101] IPBES (2020), Workshop Report on Biodiversity and Pandemics, https://ipbes.net/sites/default/files/2020-12/IPBES%20Workshop%20on%20Biodiversity%20and%20Pandemics%20Report_0.pdf.

[2] IPBES (2019), Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, https://www.ipbes.net/global-assessment.

[43] IPBES and IPCC (2021), IPBES-IPCC co-sponsored workshop report on biodiversity and climate change, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5101133.

[41] IUCN (n.d.), Blue Carbon Issues Brief, https://www.iucn.org/resources/issues-briefs/blue-carbon.

[1] Leal Filho, W. et al. (eds.) (2018), The Biodiversity Finance Initiative: An Approach to Identify and Implement Biodiversity-Centered Finance Solutions for Sustainable Development, Springer, https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-73028-8_5.

[15] Lee, C. et al. (2022), “The contribution of climate finance toward environmental sustainability: New global evidence”, Energy Economics, Vol. 111, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2022.106072.

[104] Loury, E. (2020), Establishing and Managing Freshwater Fish Conservation Zones with Communities. A guide based on lessons learned from Critical Ecosystems Partnership Fund grantees in the Indo-Burma Hotspot, https://www.cepf.net/sites/default/files/fish-conservation-zone-guidebook.pdf.

[58] Lo, V. (2016), Synthesis Report on Experiences with Ecosystem-based Approaches to Climate Change Adaptation and Disaster Risk Reduction, https://www.cbd.int/doc/publications/cbd-ts-85-en.pdf.

[59] Luna Rodríguez, M. and R. Villate Rivera (2022), Nature-based solutions in the NDCs of Latin American and Caribbean countries: classification of commitments for climate action, https://doi.org/10.2841/236987 (accessed on 16 January 2023).

[7] Miller, D., A. Agrawal and J. Roberts (2013), “Biodiversity, Governance and the Allocation of International Aid for Conservation”, Conservation Letters, Vol. 6/1, pp. 12-20, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-263X.2012.00270.x.

[36] Milner-Gulland, E. et al. (2021), “Four steps for the Earth: mainstreaming the post-2020 global biodiversity framework”, One Earth, Vol. 4/1, pp. 75-87, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2020.12.011.

[57] Murti, R. and C. Buyck (2014), Safe Havens. Protected Areas for Disaster Risk Reduction and Climate Change Adaptation, https://www.iucn.org/sites/dev/files/2014-038.pdf.

[68] Nature Climate Change (2022), “The eco–climate nexus”, Nature Climate Change, Vol. 12/595, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-022-01418-1.

[16] Nori, J. et al. (2022), “Insufficient protection and intense human pressure threaten islands worldwide”, Perspectives in Ecology and Conservation, Vol. 20/3, pp. 223-230, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2530064422000396?dgcid=raven_sd_via_email.

[74] OECD (2022), Climate-related ODA and Biodiversity ODA with Gender Objectives: A Snapshot, https://www.oecd.org/dac/ODA_for_climate_biodiversity_and_gender_equality.pdf.

[26] OECD (2022), Environmental Fragility in the Sahel, https://www.oecd.org/dac/Environmental_fragility_in_the_Sahel_perspective.pdf.

[11] OECD (2022), Natural resource governance and fragility in the Sahel, https://www.oecd.org/dac/2022_Natural_resource_governance_fragility_Sahel.pdf.

[72] OECD (2022), OECD DAC Creditor Reporting System Statistics, OECD.Stat, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=crs1.

[114] OECD (2022), OECD DAC Creditor Reporting System Statistics, OECD.Stat, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=crs1.

[12] OECD (2022), States of Fragility 2022, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/c7fedf5e-en.

[23] OECD (2021), Managing Climate Risks, Facing up to Losses and Damages, https://www.oecd.org/publications/managing-climate-risks-facing-up-to-losses-and-damages-55ea1cc9-en.htm.

[33] OECD (2020), A Comprehensive Overview of Global Biodiversity Finance, https://www.oecd.org/environment/resources/biodiversity/report-a-comprehensive-overview-of-global-biodiversity-finance.pdf.

[30] OECD (2020), States of Fragility, https://www3.compareyourcountry.org/states-of-fragility/about/0/.

[31] OECD (2020), States of Fragility 2020 platform - Fragile context profiles, OECD, https://www3.compareyourcountry.org/states-of-fragility/countries/0/ (accessed on 24 May 2022).

[34] OECD (2020), Sustainable Ocean for All: Harnessing the Benefits of Sustainable Ocean Economies for Developing Countries, https://www.oecd.org/environment/sustainable-ocean-for-all-bede6513-en.htm.

[98] OECD (2019), Linking Indigenous Communities with Regional Development, https://doi.org/10.1787/3203c082-en.

[24] OECD (2019), What is ODA? (brochure), https://www.oecd.org/development/stats/What-is-ODA.pdf.

[19] OECD (2018), Making Development Co-operation Work for Small Island Developing States, http://oecd.org/dac/making-development-co-operation-work-for-small-island-developing-states-9789264287648-en.htm.

[21] OECD (n.d.), History of DAC Lists of aid recipient countries, https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-standards/historyofdaclistsofaidrecipientcountries.htm.

[103] Oliveira, K. (2021), Povos e comunidades tradicionais: metodologias de autoidentificao e reconhecimento, https://www.cepf.net/sites/default/files/guia_de_mapeamento_-_sm.pdf.

[47] Parrotta, J. et al. (2022), Forests, Climate, Biodiversity and People: Assessing a Decade of REDD+, https://www.iufro.org/fileadmin/material/publications/iufro-series/ws40/ws40.pdf.

[112] Paul, R. et al. (2022), Greening the Grassroots: Rethinking African Conservation Funding, http://maliasili.org/greeningthegrassroots.

[45] Pettorelli, N. et al. (2021), “Time to Integrate Global Climate Change and Biodiversity Science-Policy Agendas”, Journal of Applied Ecology, Vol. 58/11, https://besjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1365-2664.13985.

[113] Quintana, A. et al. (2020), “Political Making of More-Than-Fishers Through Their Involvement in Ecological Monitoring of Protected Areas”, Biodiversity Conservation, Vol. 29, pp. 3899-3923, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-020-02055-w.

[27] Raineri, L. (2020), “Sahel climate conflicts? When (fighting) climate change fuels terrorism”, EUISS Conflict Series.

[42] Rainforest Foundation Norway (2021), Falling Short. Donor funding for Indigenous Peoples and local communities to secure tenure rights and manage forests in tropical countries (2011–2020), https://d5i6is0eze552.cloudfront.net/documents/Publikasjoner/Andre-rapporter/RFN_Falling_short_2021.pdf?mtime=20210412123104.

[110] Rights and Resources and Rainforest Foundation Norway (2022), Funding with Purpose: A Study to Inform Donor Support for Indigenous and Local Community Rights, Climate, and Conservation, https://rightsandresources.org/wp-content/uploads/FundingWithPurpose_v7_compressed.pdf.

[90] Santy, A. et al. (2022), “Donor perspectives on strengthening capacity development for conservation”, Oryx: The International Journal of Conservation, Vol. 56/5, pp. 740-743, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605322000746.

[32] Standing, A. (2021), Financialisation and the blue economy #1. Understanding the conservation finance industry., https://www.cffacape.org/publications-blog/understanding-the-conservation-finance-industry.

[86] Stepping, K. and K. Meijer (2018), “The Challenges of Assessing the Effectiveness of Biodiversity-Related Development Aid”, Tropical Conservation Science, Vol. 11, pp. 1-11, https://doi.org/10.1177/1940082918770995.

[61] Swann, S. et al. (2021), Public International Funding of Nature-based Solutions for Adaptation: A Landscape Assessment, https://doi.org/10.46830/wriwp.20.00065.

[55] Terton, A. (2022), Thematic Paper 3. Nature-Based Solutions: An Approach for Joint Implementation of Climate and Biodiversity Commitments, https://www.adaptationcommunity.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/03-thematic-paper-NbS-biodiv-climate-implementation-giz-iisd-ufz.pdf.

[66] Terton, A. et al. (2022), Synergies between biodiversity- and climate-relevant policy frameworks and their implementation.

[3] Tobin-de la Puente, J. and A. Mitchell (2021), The Little Book of Investing in Nature, https://www.biofin.org/sites/default/files/content/knowledge_products/LBIN_2020_RGB_ENG.pdf.

[102] Tsioumani, E. (2022), Thematic Paper 1. Linkages and Synergies Between International Instruments on Biodiversity and Climate Change, https://www.adaptationcommunity.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/01-thematic-paper-synergies-biodiv-climate-instruments-giz-iisd-ufz.pdf.

[67] Tsioumani, E. (2022), Thematic Paper 4. Good Governance for Integrated Climate and Biodiversity Policy-Making, https://www.adaptationcommunity.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/04-thematic-paper-good-governance_biodiv-climate-policymaking-giz-iisd-ufz.pdf.

[62] Tyllianakisa, E., J. Martin-Ortega and S. Banwart (2022), “An approach to assess the world’s potential for disaster risk reduction through nature-based solutions”, Environmental Science and Policy, Vol. 136, pp. 599-608, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1462901122002301?dgcid=raven_sd_via_email.

[69] UN Biodiversity Lab (n.d.), UN Biodiversity Lab, https://unbiodiversitylab.org/.

[71] UNCCD (2022), Global Land Outlook. Second Edition. Land Restoration for Recovery and Resilience, https://www.unccd.int/sites/default/files/2022-04/UNCCD_GLO2_low-res_2.pdf.

[20] UNDESA (2022), Small Island Developing States. Gaps, Challenges and Constraints in Means of Implementing Biodiversity Objectives, https://sdgs.un.org/publications/gap-assessment-report-challenges-and-constraints-means-implementing-biodiversity.

[70] UNDP (2021), Mapping Nature for People and Planet, https://unbiodiversitylab.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/ELSA-Brochure-English_final.pdf.

[48] UNDP; Secretariat of the CBD; UNEP-WCMC (2021), Creating a Nature-Positive Future: The contribution of protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures, https://www.cbd.int/pa/doc/creating-a-nature-positive-future-en.pdf.

[82] UNDP-BIOFIN (2017), Gender perspectives in biodiversity finance, https://www.biofin.org/news-and-media/gender-perspectives-biodiversity-finance.

[52] UNEP (2022), Resolution adopted by the United Nations Environment Assembly on 2 March 2022. 5/5. Nature-based solutions for supporting sustainable development, https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/39864/NATURE-BASED%20SOLUTIONS%20FOR%20SUPPORTING%20SUSTAINABLE%20DEVELOPMENT.%20English.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

[64] UNEP (2022), State of Finance for Nature. Time to act: Doubling investment by 2025 and eliminating nature-negative finance flows, https://wedocs.unep.org/20.500.11822/41333.

[63] UNEP (2021), Making Peace with Nature: A scientific blueprint to tackle the climate, biodiversity and pollution emergencies, https://www.unep.org/resources/making-peace-nature.

[50] UNEP (2021), State of Finance for Nature 2021, https://www.unep.org/resources/state-finance-nature.

[83] UNEP (2019), Promoting Gender-Responsive Approaches to Natural Resource Management for Peace in North Kordofan, Sudan (2019), https://www.unep.org/resources/report/promoting-gender-responsive-approaches-natural-resource-management-peace-north.