Unemployment benefits and associated employment support measures help individuals and families to manage labour market risks. Income support plays a key stabilising role, especially so in the current context of heightened economic uncertainties, and the acceleration of hires and layoffs that is likely to accompany the green transition and the adoption of new production technologies. By pooling earnings and employment risks across different groups, social protection lowers the costs associated with job reallocation. It also makes economic or social disadvantage less concentrated on specific regions or groups, and less damaging for people’s longer-term prospects. From an economy-wide perspective, risk pooling, income smoothing, redistribution and enabling support foster resilience against systemic uncertainties, including those related to the speed and magnitude of future labour market transformations.1

A strong focus on labour market flexibility has contributed to Korea’s remarkable economic development, benefiting larger companies and export-oriented industries in particular. However, income inequality among working-age Koreans remains higher than in most countries included in the OECD Income Distribution Database (http://oe.cd/idd). Indeed, the economic gains of decades of strong economic growth have been uneven. Low earnings and precarious employment remain widespread among the large number of workers in small and micro-businesses, and for some groups of self-employed. Indeed, labour regulations and agreements in Korea have been geared towards protecting permanent jobs but often fail to provide for those in less regular employment situations. Social benefits have been less effective at reducing income disparities in Korea than in other OECD countries (OECD, 2015[9]). Korea spends far less on cash benefits for working-age individuals and children than the average OECD country (1.3% versus 3.7% of GDP in 2019, see http://oe.cd/SOCX). In addition, a relatively low share of total transfers reach those with the greatest need for support – in fact, past studies have shown that high-income households receive similar or slightly bigger government transfers on average than low-income households (OECD, 2017[10]; OECD, 2022[11]).

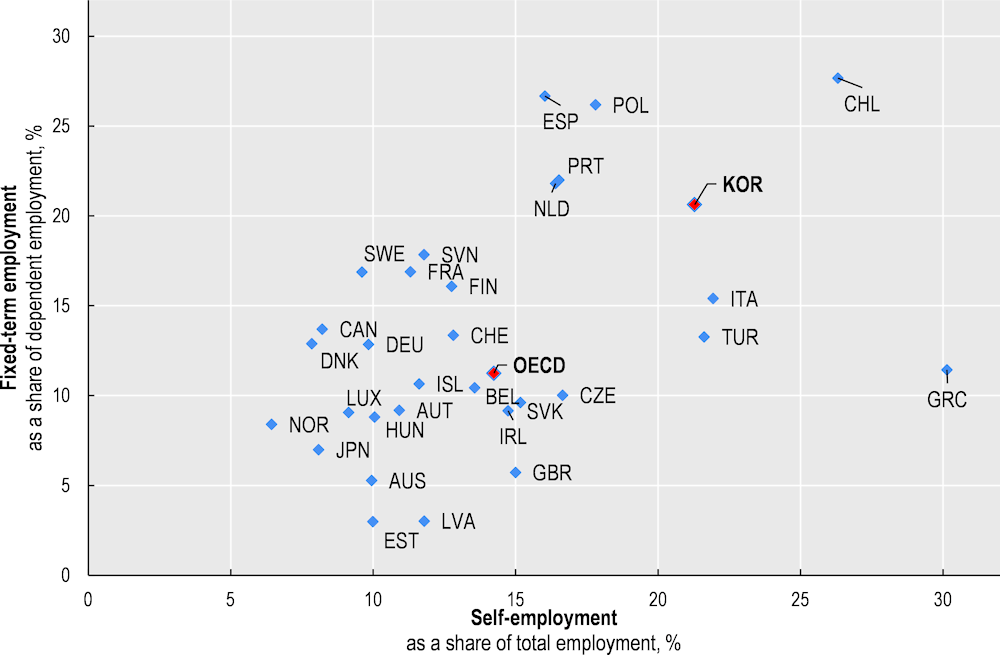

A large share of Korea’s population stand to gain from the income security and employment services afforded by more accessible unemployment support. First, in the context of Korea’s dual labour market, unstable or intermittent jobs and earnings are very common (Figure 2.1, Table 2.1). Non-regular employment, which includes temporary, part-time and atypical jobs (e.g. daily workers, contractors, temporary agency), accounts for about a third of salaried employment, with substantially higher shares among youth, older workers and women. Historically, the growing incidence of short contract durations can be linked to economic downturns, employers seeking to keep labour costs flexible and to reduce them quickly when needed. Currently, non-salaried workers (self-employed and unpaid family workers) make up about a quarter of the employed population in Korea, well above the OECD average of about 15%. The high prevalence of non-regular employment, self-employment and micro-businesses is associated with poor job quality, including low pay and short job durations. Indeed, poor-quality jobs in lower-productivity sectors are commonly outsourced to SMEs, and the life span of small businesses themselves is often very short too, for instance in 2018 and 2019, around 70% of small businesses in operation were less than five years old (OECD, 2022[12]). Overall employment stability is low, with median job tenure (time in current job) at just over 5 years. This is markedly lower than the OECD average, which stood at just over 8 years (Figure 2.2).

Second, prior to the pandemic, more than one in four working-age Koreans (28%) were not in employment, education or training. This is among the biggest shares of jobless people across OECD countries, with particularly high inactivity rates among youth and women (Fernandez et al., 2020[13]). Keeping displaced workers and other out-of-work individuals in the labour force, mobilising the inactive, and increasing their chances of finding suitable employment, are central functions of unemployment benefits – especially in the context of Korea’s rapidly ageing population, and risks of significant worker and skills shortages in some sectors.

Both equity and efficiency arguments therefore point to accessible unemployment benefits as a policy priority in Korea. As in other countries, the design of unemployment benefits needs to account for the specific labour-market and social context in order to be effective. This requires drawing a careful balance between incentivising employment, providing a degree of income security, and promoting the efficient allocation of labour and skills. Although Korea has among the lowest rates of long-term unemployment in the OECD, overly generous out-of-work benefits may entrench long-term unemployment. At the same time, inaccessible or very modest income support risks cementing existing labour-market inequalities and lowering productivity through skills mismatch. Without adequate support, jobseekers may be unable to afford a careful search for suitable work. To make ends meet, they can then be compelled to accept employment that may provide a poor match for their skills and aspirations. The same holds for those looking to transition from one job to another. In fact, a prevalent business culture of very long working hours and presenteeism arguably makes successful job search particularly difficult for working Koreans.2 Skills mismatch in Korea is indeed substantial. “Over-skilling” has been especially prevalent among those in non-regular employment (Adalet McGowan and Andrews, 2015[14]), who are also less likely to qualify for unemployment support. Such an association can be a result of insufficient job search among jobseekers who are not entitled to unemployment support. As in several other OECD countries, non-standard workers in Korea were indeed less likely to receive income support following job loss (Figure 1.1).