Korea operates an unemployment insurance benefit (Employment Insurance), an unemployment assistance programme (National Employment Support Programme) for low-income families who do not receive insurance benefits, as well as a minimum-income benefit (Basic Livelihood Security System) targeted to income‑poor households. Korean firms provide severance pay in the form of “retirement benefits” to workers leaving a job (voluntarily or involuntarily) that lasted at least 12 months.1 Some employers, especially larger firms, also provide additional redundancy payments as part of collective or workplace agreements.

Benefit Reforms for Inclusive Societies in Korea

3. Unemployment benefits in Korea

3.1. Origins, key characteristics and past reforms

3.1.1. Employment Insurance

Prior to the mid‑1990s, Korea did not operate an unemployment benefit (UB). The introduction of the Employment Insurance System (EIS), in 1995, came later than in most OECD countries. It also came later than other social protection initiatives in Korea, such as the Industrial Accidents Compensation Insurance (IACI), which was introduced 30 years earlier, and successive measures to establish or extend coverage of old-age pensions and health insurance (OECD, 2018[2]; Yoo, 2011[15]). Prior to the EIS initiative, high growth rates of GDP and employment meant that unemployment was not widely seen as a pressing issue. But policy priorities changed during the 1990s, as job security declined, time‑limited (“fixed-term”) employment contracts became more common, and wage inequality deteriorated. Efforts to establish unemployment benefits nevertheless faced considerable headwinds, with negative public opinion linked to concerns about work disincentives, and about the impact of insurance premia on labour costs and take‑home pay. Consequently, EIS launched with low replacement rates and strict entitlement conditions. For instance, UBs were restricted to firms with at least 30 employees, and active labour market programmes (ALMPs) to firms with at least 70 employees, resulting in low coverage overall.

The EIS consists of two main parts: (i) the Unemployment Benefit and Maternity Protection Programme, and (ii) the Employment Security and Vocational Skills Development Programme (ALMPs, such as employment services, training, wage subsidies and job retention schemes). The funding system reflects this structure (see Table 3.1). Overall contribution rates for the benefits account were 0.6% in 1995, rising successively to 1.3% in July 2013 and to 1.8% as of July 2022. Contributions to the benefits account are shared equally between employer and employee, i.e. 0.9% each as of July 2022. By contrast, contributions to the Employment Security and Vocational Training account are fully covered by employers and rates were broadly stable over time: 0.3~0.7% (depending on firm size) in 1995, and 0.25~0.85% in 2022. The maternity protection programme, introduced in 2001 and not discussed further in this report, is managed under the same account as UB. This funding arrangement, along with the comparatively low contribution burdens, has constrained the financial space for expanding UB coverage and generosity.

Moreover, contributions were heavily subsidised and much lower than the standard rate for a large number of low-paid workers in smaller firms. The Duru-Nuri Social Insurance Subsidy Programme was launched in early 2012 to encourage participation of low-paid workers in small firms in the (mandatory) EI and National Pension schemes. The programme initially subsidised up to 50% of employer and employee contributions. Subsidies subsequently distinguished between new and existing subscribers, with higher support rates for new subscribers. From January 2021, the subsidies stopped for existing members, but it continues for new subscribers, with support covering 80% of contribution burdens for up to 36 months (http://www.insurancesupport.or.kr/durunuri/history.php). Duru-Nuri subsidies are now also available for artists, dependent contractors and for platform workers engaged by small businesses. Past evaluations have pointed to very high deadweight costs, with very high expenditures per additional enrolment (around 3 times the average annual wage, (Kim, 2016[16]; OECD, 2018[2])), and to the contradictory nature of incentivising participation in mandated schemes, as if it was a choice.

Table 3.1. Employment Insurance: Evolution of expenditures

|

Total |

Employment Security |

Skills Development |

Unemployment Benefit |

Maternity Protection |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

% of GDP |

% of social expenditure |

% of total EIS spending |

||||

|

1996 |

0.01 |

0.2 |

34.3 |

27.2 |

38.5 |

- |

|

2000 |

0.17 |

3.4 |

11.6 |

44.3 |

44.1 |

- |

|

2005 |

0.31 |

4.8 |

9.4 |

25.7 |

65.0 |

|

|

2010 |

0.45 |

5.4 |

12.6 |

18.2 |

62.1 |

7.2 |

|

2018 |

0.61 |

5.2 |

19.3 |

12.0 |

58.3 |

9.4 |

|

2019 |

0.72 |

- |

19.8 |

9.2 |

60.7 |

9.5 |

|

2020 |

1.06 |

- |

27.2 |

4.9 |

60.2 |

7.6 |

Source: (MOEL, 2021[17]), 2020 Employment Insurance Fund Settlement Report ; OECD Social Expenditure Database (http://oe.cd/socx).

Earlier adopters of unemployment insurance in the OECD area tended to strongly emphasise the income protection element. Unlike in other countries, the Korean EIS was specifically conceived as a response to displacement following business closures or mass layoffs. As such, it featured an explicit focus on ALMPs and promoting re‑entry into the labour market from the beginning, and these roles were seen equally important as the provision of relief measures (ILO, 2021[18]; Korean Economy Compilation Committee, 2011[19]). This partly reflected low re‑employment rates of displaced workers in Korea. Re‑employment rates remained, however, comparatively low despite the EIS early focus on labour-market re‑entry.2 One notable consequence of the early policy debate’s focus on re‑employment was that expanding coverage and benefit generosity initially proceeded cautiously and both remained modest at first. An early set of extensions was enacted following the 1997 financial crisis, when unemployment in Korea nearly tripled between 1997 and 1998. Restrictions on coverage (such as the firm-size requirement) were eased and benefit durations extended, resulting in a more universal application of the EI membership mandate and increasing benefit coverage. Other access conditions, such as contribution requirements were also reformed but they remained comparatively strict, effectively excluding those with more volatile employment histories.

At the height of the labour market crisis in 1998, UB reached only 10% of the unemployed. In spite of the early reforms, coverage remained below 20% of the unemployed until the mid‑2000s.3 From 2000, the required contribution period was cut in half (to 180 days), and the maximum benefit duration was gradually extended from 210 to 270 days. The programme also began to embrace some groups of non-standard employees, including part-time, daily and self-employed workers. For instance, from 2012 onwards, the self-employed and employers with up to 50 employees could voluntarily contribute to EI, contributing a total of 2.25% of a self-chosen remuneration level, and qualifying for unemployment benefits if their business closed involuntarily due to a reason beyond their control (MOEL, 2021[20]).4 The government also introduced measures to counter incentives for avoiding EIS membership, or for opting out legally. This included lowering contribution rates for low-income earners and for employees who become EIS members for the first time (both from 2012, see description of the Duru-Nuri subsidy programme above). There were also initiatives to simplify EI registration and applications and make them less costly and time‑consuming. For instance, the collection of contributions across the four major branches of social insurance was integrated into a single process (from 2009) and employers have received additional administrative support when registering employees. Regulations concerning employers’ registration obligations were strengthened (e.g. through the imposition of fines), though effective enforcement has remained a major challenge (see section 4 and (OECD, 2018[2]; Lee, 2017[21])).

For a good understanding of the reach of income support in practice, and the effects of policy changes, it is important to consider different concepts of benefit coverage.

By 2020, EIS membership among dependent employees stood at around 70% (Statistics Korea, 2020[22]). Compliance therefore remains incomplete. For instance in 2018, half of dependent employees who were not members of EI did not join despite being required to do so (Kim, 2020[23]). EIS membership (the “application rate”) among all workers, including the self-employed and dependent contractors, remained below 50%.

Administrative statistics point to a notable increase in recent years in the share of benefit recipients among registered unemployed, from around 37% in 2018 to 71% in 2022.

However, as in other countries, not all jobseekers register as unemployed, and registration is less likely among those not entitled to benefits. In addition, a significant share of benefit payments can – intentionally or not – go to individuals who do not meet the common definition of unemployment. The share of benefit recipients among all unemployed individuals (whether registered or not) was therefore much lower: in 2019, it ranked among the lowest in the OECD when comparing benefit receipt among the unemployed using available survey data (see section 4.1.1).These patterns are consistent with significant unemployment risks among those who do not qualify for UB, or who avoid EI membership altogether.

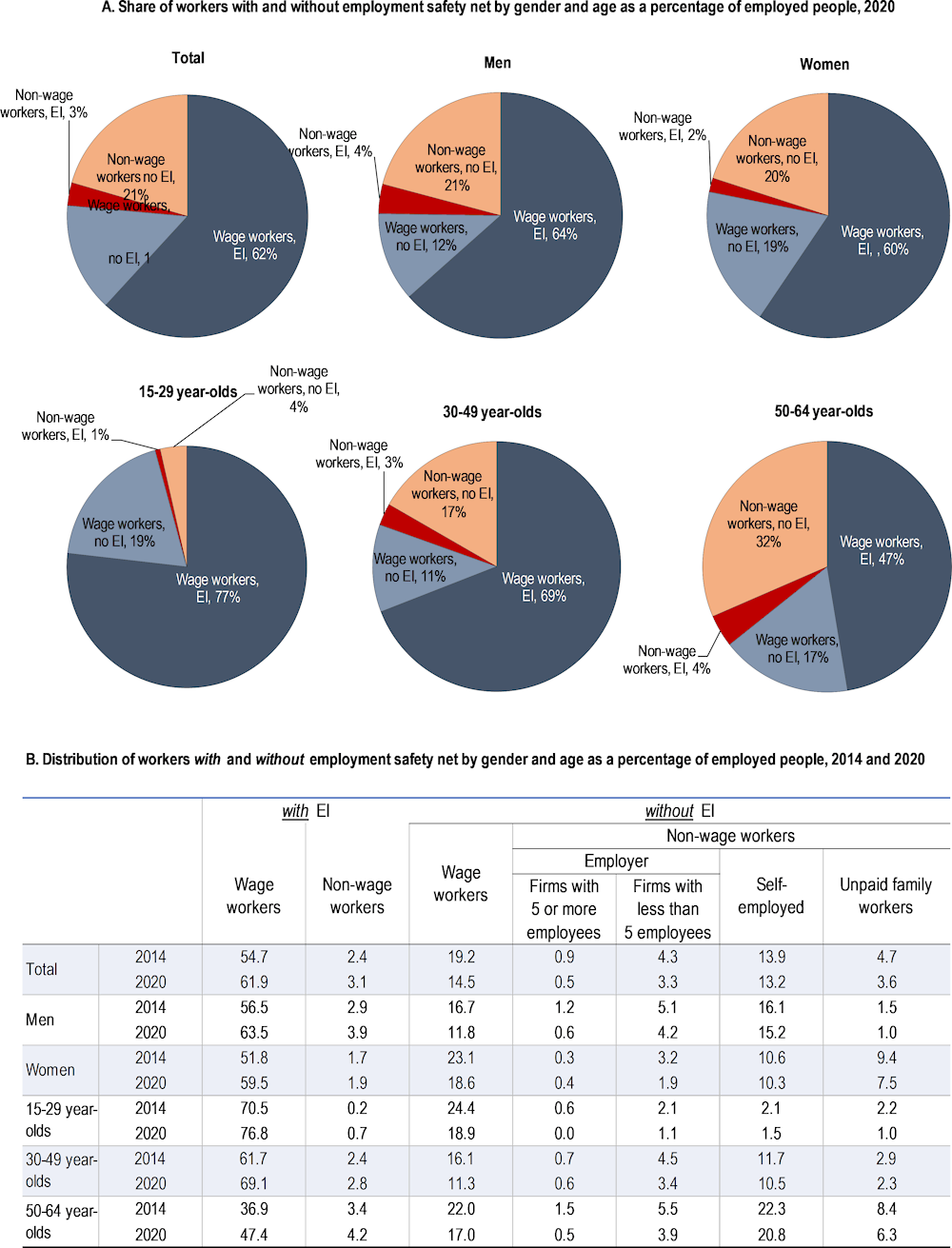

For non-standard workers, there has been some progress in expanding statutory coverage during the years prior to the COVID‑19 crisis. Nevertheless, “blind spots” remained sizeable in 2020 and most of the large number of non-standard workers were not EIS members (Figure 3.1). The application rate among non-standard dependent employees (part-time, temporary and atypical workers, such as dependent contractors and freelancers) was only half that of full-time standard employees (46% versus 90%, (Statistics Korea, 2020[22])). A similar picture emerges from a breakdown of survey data, shown in Figure 3.1. As in other countries with voluntary insurance membership, non-standard workers, and their employers or clients, remained reluctant to cover the cost of insurance premiums. Unresolved administrative issues, such as the accurate assessment of employment status and incomes further hindered efforts to make out-of-work support broadly accessible to those who need it. Recent and ongoing reforms have sought to tackle blind spots by addressing several of these aspects (see section 3.2 and Box 3.1).

Figure 3.1. Large blind spots in Korea’s Employment Insurance membership

Note: Adapts and updates a similar figure published in (OECD, 2018[2]) and (Yoo, 2013[24]).

Wage workers: Employed by other people or companies and work with remuneration (wage) (company, part-time job etc.).

Non-wage workers: Self-employed/employer (private business, freelancer, running a shop, a chief workman of construction site, agriculture, forestry and fishery industry, peddler and street vendor etc.).

Family worker: Helping family members (relatives) for more than 18 hours a week without pay.

Source: OECD calculations using the Korea Labour and Income Panel Study (KLIPS).

When EIS was first introduced, benefit payments replaced 50% of jobseekers’ previous wages, with minimum and maximum payment levels set at around 20% and 80% of the average wage, respectively. Over time, this margin has narrowed dramatically, as the floor was linked to the minimum wage, while the ceiling was raised much less quickly, on a discretionary basis. As a result, EI turned virtually into a flat-rate payment, significantly altering the nature of the benefit programme, and effectively removing the earning link (Box 3.1). Partly in response, reforms in 2019 raised the benefit cap, while the floor was set at 80% of the minimum wage, down from the 90% before. Nonetheless, the structural reasons for the convergence of benefit floor and cap remained, and on 1 January 2022, they stood, respectively, at KRW 60 120 and KRW 66 000 (for somebody working 8 hours or more). In addition, the 2019 reform also raised the formula replacement rate from 50% to 60% of usual earnings and extended the benefit duration to 120‑270 days (before: 90‑240 days), depending on the previous employment period and age. The extremely close proximity of benefit floor and benefit cap means that, for most benefit claimants, changes in the formula replacement rate have no notable effect on entitlements.

3.1.2. Unemployment assistance

In 2009, in the context of the global financial crisis, Korea introduced the tax-financed “Employment Success Package Programme” for low-income jobseekers with working ability, who are not covered by either EI or BLSS. ESPP was a form of employability support with a non-contributory benefit component. Unemployment assistance programmes in other OECD countries have a strong focus on income support, which tends to vary with income. ESPP differs in two respects. First, it was strongly geared towards promoting employability and employment retention, offering customised job-search assistance and, if necessary, training.5 Second, the income support component for eligible individuals is flat rate, rather than varying with income. Income transfers aimed to provide livelihood support and strengthen employment incentives. They included a small lump-sum benefit, a monthly training participation incentive, and an employment success allowance for those who are employed for 3 months after the end of programme, with additional payments for those who are employed after 6 months or 12 months (Kim and Lee, 2018[25]).

ESPP sought to occupy and address the large gap between EI and BLSP and included a large group of potential beneficiaries from the start. Eligibility was subject to a means test, except for young people under the age of 34 and a broad range of “vulnerable” groups, who had access regardless of income since 2011.6 The income limit was raised in 2012, and eligibility was extended to the elderly (ages 65‑69) in 2017. Recipient numbers increased from 64 000 in 2011 to 295 000 in 2015, and 360 000 in 2020. As an employment-support measure, ESPP worked well and efficiently (i.e. at relatively low fiscal cost), raising employment among participants and strengthening job retention (Kim and Lee, 2018[25]; OECD, 2018[2]). ESPP also filled some blind spots left by EIS and BLSS in terms of income security. But it was insufficient as an income safety net for jobseekers, as income support levels were low (about 10‑15% of the median wage, less than half the BLSS payment rate) and the small cash benefits expenses linked to the job search process provided no stable income.

In 2019, the government initiated a reform process towards the “National Employment Support System” (NESP), which extended to previous ESPP and started being rolled out in January 2021 (see below and Box 3.1).

3.1.3. Supplementary income assistance programmes

As last-resort benefits, the roles of minimum-income programmes in OECD countries depend on the reach and structure of “upstream” income transfers, including unemployment benefits. In Korea, means-tested support programmes targeted at the poor were, in part, introduced and expanded in the context of persistent accessibility gaps in the EI programme. From the early 2000s, and in response to the Asian foreign currency crisis in 1998 and the associated rapid increase in poverty, the “Basic Livelihood Security System” (BLSS) sought to guarantee a minimum standard of living and promote self-sufficiency. As labour market dualism in Korea intensified, with an increasing number of low-paid precarious jobs, demand for social assistance stretched well beyond the core aims of tackling poverty among children and the elderly and became increasingly relevant as income support for the unemployed and “working poor” (Kim, 2020[26]).

Prior to the COVID‑19 pandemic, the number of individuals benefiting from the BLSS livelihood programme was in the same order of magnitude as the number of EI payments.7 The combined recipient numbers of livelihood, housing, health, and education benefits provided under the BLSS programme, is 1.9 million, 3.6% the total population (MOHW, 2020[27]). The government has taken initiatives to reduce “blind spots” in the BLSS, e.g. by simplifying entitlement criteria related to income and wealth, and by reforming/co‑ordinating related safety net benefits, such as for housing, education, and medical care. In the past, and consistent with Asian cultural norms regarding family support, the BLSS means-test included a support obligation for parents and children of claimants even if they did not live in the same household, resulting in low recipient numbers (Shon, 2019[28]). This familial support obligation was abolished in October 2021 (Joint Ministries, 2020[29]).8 However, benefit recipient numbers have changed little since 2015 and blind spots continue to exist due to relatively demanding eligibility conditions (OECD, 2022[12]). BLSS support levels tend to be modest, with a payment rate of about 30% of a median wage. Empirical estimates of actual minimum-income support payments received by low-income households point to benefit levels that are below those of other OECD countries, and much lower than commonly used relative poverty thresholds (Hyee et al., 2020[30]).

Box 3.1. Unemployment benefits in Korea: Main entitlement rules, 2022

Unemployment insurance

There are two categories of unemployment benefits in the Employment Insurance (EI) programme. The Job Seeking Allowance provides cash payments to maintain workers’ standards of living and to facilitate their re‑employment. In addition, Employment Promotion Allowances supports a quick re‑employment of beneficiaries through various support measures. This includes an Early Re‑employment Allowance, which is available to recipients of the Job Seeking Allowance, who are re‑employed in a steady job and retain the employment for more than 12 months, and who would have more than 1/2 of their Job Seeking Allowance entitlements left. The Early Re‑employment Allowance is paid as a lump sum and, after a series of reforms, now amounts to 50% of the otherwise remaining Job Seeking Allowance.

EI covers employees working at least 60 hours per month (15 hours per week) on a mandatory basis. To be eligible, workers must have been insured for at least 180 days over 18 months prior to becoming unemployed (9 months during the past 24 months for artists and 12 months during the past 24 months for dependent contractors). Claimants most be unemployed involuntarily and through no fault of their own. However, like other countries requiring involuntary unemployment as an entitlement condition criterion, Korea has provisions that effectively extend EI access to several categories of voluntary quits that are acknowledged as inevitable or otherwise legitimate, such as job separations related to workplace bullying or discrimination, health limitations, unreasonable commuting times, and certain care responsibilities. Quits regarded as voluntary quits do not entitle to any EI benefits and neither does dismissal for reasons such as gross worker misconduct or lack of competence. Claimants must be willing and able to work and engage in active job-search during benefit receipt.

Those aged 65 or older are not covered, unless they are continuing in a job they have held before turning 65. Family workers are also not covered. Unincorporated small workplaces (no more than four employees, including seasonal workers) in the agriculture/forest/fishery sectors are not subject to mandatory EI. They can enrol if a majority of workers agree, though de facto EI membership rates are low.

Benefit payments can start following a waiting period of 7 days after job loss. The daily basic allowance is 60% of the daily wage and is calculated based on the average wage paid during the three months prior unemployment (12 months for artists and for dependent contractors, referred to “special employment type worker” in Korea). Payment is usually made on a monthly basis. The benefit floor amounts to 80% of the minimum wage (KRW 60 120 per day, for at least 8 hours of work), and is reduced proportionally for part-time workers. The minimum for artists and dependent contractors is KRW 16 000 and KRW 26 000 per day, respectively. The benefit is capped at KRW 66 000 per day for all beneficiary categories.

Table 3.2. Maximum benefit durations increase with age and contributions, and ranges from 4 to 9 months

|

Age (years) |

Maximum duration of Job Seeking Allowance (days) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Period of contribution to the EIS (years) |

||||||

|

Under 1 |

1 to 3 |

3 to 5 |

5 to 10 |

10 or more |

||

|

Under 50 |

120 |

150 |

180 |

210 |

240 |

|

|

Over 50 or disabled |

120 |

180 |

210 |

240 |

270 |

|

The Job Seeking Allowance also comprises the following additional transfers:

Individual Extended Benefits are offered to jobseekers who were unsuccessfully referred to job vacancies three or more times by a Job Centre. Extended benefits are available following expiry of the regular Job Seeking allowance and provide 70% of previous benefits for an additional 60 days. Special Extended Benefits have the same value and duration and can be paid if the authorities declare that the labour market situation is particularly bad (this mechanism has not been used since the 1998 financial crisis);

Benefits for extended training are offered to jobseekers who cannot find work due to a lack of skills and who undertake training. They provide 100% of previous benefits for up to two years.

Unemployment assistance

In January 2021, the “National Employment Support Programme” was introduced, as a modified extension of the earlier “Employment Support Package Programme” (ESPP). Like ESPP, this Korean-style unemployment assistance provides employment services and livelihood support to vulnerable groups in employment, including low-income job seekers, unemployed youth, and those looking to return to work following career breaks, particularly women;

Type‑I support consists of a job-search promotion cash benefit, employment support services, including an employment success allowance;

Type‑II provides employment support services, including the employment success allowance.

Eligibility:

Type‑I support:

Active jobseeker aged between 15 and 69 years old, with household income at or below 60% of the median. Requires work experience of at least 100 days in the last 2 years;

Or: Job-seeking youth aged between 18 and 34 years old, with income at or below 120% of the median. Work experience is not a requirement for youth;

Type‑I support is not available for recipients of EI, Basic Livelihood Security (BLSS) benefits, local government youth benefits, and for participants in direct job creation programmes in the previous six months;

Household assets must be below KRW 400 million (KRW 500 million for young jobseekers aged 18‑34).

Type‑II support:

Individuals aged 15‑69, with household income below 100% of the median;

Young people (18‑34), who do not qualify for Type‑I support (regardless of their income);

There is no asset test for Type‑II support.

Benefit amounts and duration:

Type‑I support: The aim of the subsidy is to support the livelihood of active jobseekers. A “job-search promotion subsidy” of 500 000 KRW per month for up to 6 months. From 2023, an additional amount of 100 000 KRW per month is paid for young or elderly dependants (for up to 4 dependents).

Type‑II support: Support to cover expenses incurred in job-search activities and participating in vocational training.

Both Type‑I and Type‑II: An “Employment Success Allowances” of up to KRW 1.5 million to programme participants with household income below 60% of the median, and who successfully take up employment. The amount depends on the duration of the employment contract (a lump-sum payment of KRW 500 000 for continuous employment of 6 months, plus a lump-sum of KRW 1 million for continuous employment of 12 months).

Source: OECD tax-benefit models and policy database, http://oe.cd/TaxBEN

3.2. Recent and ongoing reforms

Recent and ongoing reform efforts take place in the context of the recent COVID‑19 pandemic, and its social and economic fallout, including in the labour market. Although the employment impacts from the pandemic were muted by swift and comparatively strict quarantine measures, the number of unemployed and economically inactive people increased by 500 000, lowering Korea’s employment rate by 0.9 percentage points. Despite a solid recovery in 2021, the employment situation differs by sector and group. In particular, the employment recovery has lagged behind for temporary workers, daily workers and the self-employed especially in the wholesale/retail and catering and lodging industries (Lee, 2021[31]). Informal workers who were not covered in the EI programme, such as atypical workers, freelancers, platform workers, and small-scale self-employed, were disproportionately affected by unemployment and income decline during this period (Lee, 2020[32]). At a cost of KRW 32.5 trillion over a two‑year period, the government implemented the Emergency Employment Security Subsidy temporary income support programme for them, e.g. providing 500 000 KRW per month for 3 months to dependent contractors and freelancers whose income fell by more than 25% during the pandemic period. As in some other OECD countries, the exceptional income support that Korea provided during the pandemic may also have altered worker expectations about income protection following a job or earnings loss. But the measures were temporary and did not address the structural gaps in Korea’s unemployment support system (Park and Youn, 2021[33]).

A first step to strengthen the income safety net more permanently was the expansion of the existing Korean-style unemployment assistance system (ESPP). The new NESP programme rolled out from January 2021, building on the experience of 12 years of ESPP operation. Relative to the previous programme, a key difference is the entitlement condition (active job search, as opposed to participation in vocational training under the previous ESPP), and the higher subsidy level (KRW 500 000 per month, as opposed to KRW 400 000 under ESPP, from 2023 an additional amount of KRW 100 000 per month is available for each young and elderly dependent, for a maximum of four dependents). Furthermore, unlike ESPP, NESP is backed by a firm legal framework that stipulates entitlements by law, making the programme more predictable and less dependent on specific budget allocations (Lee, 2021[31]). Currently, future reform plans for NESP include enhancing the job-search promotion benefit and linking entitlements more closely to job-search efforts (Lee, 2021[31]).

Another major reform initiative is the plan to gradually expand EI coverage to all workers, notably including those in non-standard dependent or independent employment. Announcing a roadmap for EI reform in 2020, the government committed to gradually expanding coverage from the current employee‑centred one, into a system for “all workers”. The 2020 reform roadmap consists of three pillars (MOEL, 2020[34]):

Promotion of EI membership for low-wage, non-standard workers;

Tackling of de jure “blind spots” of employment insurance, including for dependent contractors, platform workers, freelancers, and artists;

Gradually expanding EI coverage for the self-employed through social consensus, with scope, pace and reform parameters yet to be agreed.

An initial step in resolving statutory blind spots was the extension of mandatory EI coverage to artists and 12 occupations of “own account workers” with relatively strong dependence on specific employers (henceforth “dependent contractors”).9 EIS application and UB payment for these groups are now operated in a framework similar to the one that applies to wage employees. In particular, employers or clients of artists and independent contractors bear half the contribution burden (and may benefit from the Duru-Nuri premium subsidy). However, rules differ from wage employees in some ways reflecting the specific circumstances of these workers. Firstly, EI is applied to those who receive monthly remuneration of KRW 800 000 or more (for independent contractors) or KRW 500 000 (for artists). For wage employees, by contrast, the relevant requirement is to have worked 15 hours or more a week. Second, entitlement requires contributions for at least 12 (independent contractors) or 9 (artists) out of 24 months prior to joblessness. For wage employees, the requirement is 7 out of 18 months. At of the end of 2021, six months after the extension of statutory membership, more than 100 000 artists and 560 000 dependent contractors had signed up for EIS.

From 2022, Korea expanded mandatory employment insurance to selected groups of platform workers, starting with delivery riders and surrogate drivers who provide labour mediated by platforms, and commit to actively looking for suitable work (Lee, 2020[35]). Depending on whether the worker’s contract is directly with the client, or with the platform provider, either the client or the platform company is required to bear the (equivalent of the) employer’s share of EI contributions.

Other groups of self-employed and freelancers work and generate income more independently. Extending coverage for them is therefore more challenging or requires a different and tailored approach (see section 4. For instance, all relevant insurance premia would need to be covered by the independent worker, and it is also far more difficult than for employees to reliably establish their labour market status and exact income. In view of these challenges, the Korean EI has been open to the self-employed on a voluntary basis, rather than by mandate. The government has indicated that more comprehensive income protection for the self-employed is desirable but that reforms will be gradual and distinguish between the needs and circumstances of different self-employed groups. The process is to be informed by careful stakeholder discussions that have begun in 2022 and are presently continuing.

As a key technical/institutional precondition for making coverage less dependent on employment type, and in parallel with the expansion of coverage for non-standard workers, the government has been promoting a policy to convert the workplace‑oriented EIS into an individual income‑based one. Partly similar to a 2017 reform in Denmark, EI entitlement criteria for non-standard workers were de‑linked from working hours and, instead, formulated in relation to individual income, which is more easily aggregated across jobs with different employer/clients and/or in different periods.10 Linkages were also established/strengthened between the National Tax Service and social insurance assessments in order to facilitate the periodic and consistent determination of incomes/earnings, including through a shortened income declaration cycle for applicable income tax filings. Furthermore, for an accurate assessment of incomes of dependent contractors and platform workers, reporting obligations were strengthened for businesses who contracted with them, as well as for labour matching platforms (Lee, 2020[35]).

Notes

← 1. The retirement benefit system, under the Employee Retirement Benefit Security Act, has been in place in some form since the 1950s. It stems from a time when no social insurance programmes were in place, and it served a dual role of providing income support during unemployment and upon retirement. More recently, its role evolved towards a supplement of the national pension system and a mechanism for encouraging workers to save for retirement. In practice, it nevertheless still provides a form of severance pay to workers changing jobs. Workers can also draw on their balances prior to leaving a job in certain circumstances (e.g. when purchasing a house).

← 2. For instance, around the mid‑2000s, only around 40% of displaced workers were re‑employed within a year, half the rate of the best-performing OECD members, such as some Nordic countries (OECD, 2013[4]).

← 3. Effective coverage has been low even for displaced workers, who have been the primary focus of the EI programme from the start when it was introduced, and who meet the “involuntary job loss” requirement by definition. An early study of displaced workers found that as many as half of them did not receive benefits through any of the available out-of-work income support programmes. For displaced daily workers (83%) and those with fixed-term contracts (72%), non-coverage rates were higher still (OECD, 2013[4]).

← 4. In addition, self-employed people who have been contributing to EI and move into a job as an employee without claiming benefits were able to cumulate those periods with the subsequent contribution periods as an employee.

← 5. Intervention was structured in three phases lasting a total of 9‑12 months and unsuccessful jobseekers could re‑apply after 3‑30 months.

← 6. “Vulnerable” groups included persons with a disability, low-income self-employed, low-income non-regular workers, female heads of households, unmarried mothers, lone parents; former soldiers with technical skills, individuals who have been declared bankrupt, ex-prisoners, homeless people, international migrants by marriage, as well as defectors from the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.

← 7. For January 2020, the OECD SOCR database (http://oe.cd/socr) shows 1.24 million individuals living in households supported by National Basic Livelihood Security, compared to 0.5 million individual EI payments (i.e. counting payments only, not the individuals in recipient households).

← 8. The so-called “obligatory provider” criterion was abolished as an eligibility requirement of Basic Livelihood Security Programme in 2015 for education benefits, in 2018 for housing benefits, and in 2021 for livelihood benefits. As of today, the “Obligatory Provider” criterion only applies to medical benefits.

← 9. Insurance solicitor, visiting lecturer for study book, visiting lecturer for educational school, delivery driver, loan solicitor, credit card member solicitor, door-to-door salesperson, rental product visiting inspector, home appliance delivery and installation technician, after-school instructor (elementary and secondary school), construction machine pilot, trucker.

← 10. In Denmark, the minimum working-hours entitlement condition was changed into an earnings criterion corresponding to at least 12 months of employment up to a certain earnings limit, see detailed country information for Denmark on http://oe.cd/TaxBEN.