Between 2012 and 2015, of the USD 81 billion in private finance mobilised for development, some 7% benefited the least developed countries (LDCs). This chapter looks at the latest situation, extending the analysis to include OECD data covering 2016 and 2017, as well as data on new leverage mechanisms, to explore trends over a six-year timeframe. It describes who the main mobilisers of private finance in LDCs are; the top sources of private finance mobilised; how blended finance is deployed across sectors; and how LDCs fare in comparison to other developing countries.

Blended Finance in the Least Developed Countries 2019

1. What are the latest trends in blended finance for least developed countries?

Abstract

1.1. Introduction

The outlook for development finance is troubling, especially for least developed countries. Foreign direct investment (FDI) to LDCs fell by 17% over the two years of 2016-17 to USD 750 billion, while official development assistance (ODA) remains the largest source of external financing (UNCTAD, 2018[1]).

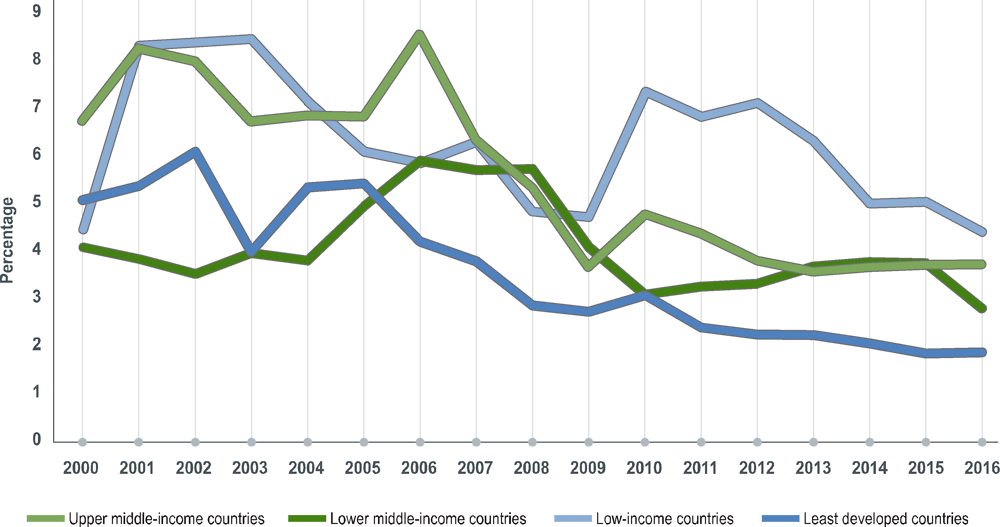

As Figure 1.1 shows, the importance of private investment flows1 has declined across all income groups (OECD, 2018[2]). At their peak in the early 2000s, private investment inflows represented approximately 6% of LDCs’ gross domestic product. Despite yearly fluctuations, the share of private investment in GDP steadily declined throughout the ensuing decade. This is particularly true for LDCs, where private investment inflows have been below 3% of GDP since 2010, falling each year to reach approximately 2% in 2016.

Moreover, preliminary data show that, in 2018, less ODA went to least developed and African countries. The new cash-flow basis methodology2 suggests that bilateral ODA to the least developed countries fell by 3% in real terms from 2017, aid to Africa fell by 4%, and humanitarian aid fell by 8%. This is of particular concern given ODA’s important role in helping LDCs meet their development goals.

Figure 1.1. Private investment inflows in developing countries (2000-2016)

Source: (OECD, 2018[2]), Global Outlook on Financing for Sustainable Development 2019, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264307995-en

Overall, the financing for development architecture is not channelling resources to LDCs effectively or at the scale and speed needed to leave no one behind. This is why there is increasing focus on how limited public resources can be used to put in place the right incentives and regulations to mobilise private finance for the SDGs.

In this context, blended finance (Box 1.1) is receiving increasing attention for its potential to maximise the catalytic impact of development finance by sharing risks or lowering costs to adjust risk-return profiles for private investors. Blended approaches can help mobilise much-needed additional capital for least developed countries. But they need to be considered carefully and should be applied as part of a broader SDG financing strategy.

Box 1.1. What is blended finance?

There are different definitions of blended finance. The Addis Ababa Action Agenda refers to blended finance as combining concessional public finance with non-concessional private finance. The OECD employs a broader definition that extends beyond concessional finance, as follows: “The strategic use of development finance for the mobilization of additional finance towards the SDGs in developing countries”, where “additional finance” refers primarily to commercial finance that does not have an explicit development purpose. “Development finance” is taken to include both concessional and non-concessional resources. The data presented in this report are consistent with the OECD’s definition. The OECD data on private finance mobilised by official development finance is, today, the best proxy available to understand how the blended finance market is evolving and where it still needs to go.

Note: For more background, see (OECD, 2018[3]), "Blended finance Definitions and concepts", in Making Blended Finance Work for the Sustainable Development Goals, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264288768-7-en

Source: (UNCDF, 2018[4]), Blended Finance in Least Developed Countries, https://www.uncdf.org/bfldcs/home

This report, the second in a series, reviews the emerging trends and issues in blending finance in the LDCs. It begins in Chapter 1 by reviewing the latest statistics: how much private sector finance is being mobilised for LDCs; is it increasing; where is it going – geographically and by sector; how is it being mobilised, etc.? Chapter 2 then brings in the voices of practitioners and experts at the blended finance coal face, who highlight important issues in the field. Chapter 3 concludes by summarising the emerging risks and opportunities, outlining key principles for all blended finance operations in LDCs, and raising some important questions to guide the next steps in this novel area. Many blended finance projects tend to fall into two categories: infrastructure projects and corporate investments. This report has maintained a particular focus on the “missing middle” segment of the corporate sector (Box 1.2).

Box 1.2. Minding the missing middle

There is a huge financing gap in the so-called missing middle. Smaller-sized projects can transform local communities but need much more technical assistance as well as financing to fulfil their potential.

Supporting missing-middle projects in LDCs requires patience and can be costly. In UNCDF’s experience, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in these geographies typically need financial support ranging from USD 50 000 to 1 million. This means they are too large for microfinance organisations, but too small or risky to access affordable or appropriate growth capital from conventional debt and equity investors.

While bank loans represent the main source of finance for SMEs, commercial banks have traditionally found lending to some SMEs challenging because of information asymmetries, lack of collateral, and the higher cost of serving smaller transactions and finding entrepreneurs with a solid business plan. Many international financial institutions (IFIs) or development finance institutions (DFIs) also do not routinely directly support smaller projects in LDCs, often because of the risks or transaction costs involved, although they do work through intermediaries or use instruments such as portfolio guarantees to encourage increased lending to SMEs.

But finance is only part of the issue. Many SMEs also need technical and advisory support – from helping them strengthen their financial practices to adhering to high environmental, social or governance standards. Ultimately, the lack of assistance for the transaction sizes required in LDCs means that SMEs are unable to grow and create jobs.

In this context, UNCDF supports smaller-sized projects with strong SDG impact throughout their lifecycle by bundling and combining capital investments with technical assistance. In addition to helping projects become bankable, often through a combination of grants and business advisory support, UNCDF also offers, through its recently established LDC Investment Platform, loans and guarantees which are intended as stepping stones for SMEs to access more commercial follow-on finance. In the case of its blended transactions, UNCDF’s support aims at mobilising private resources, notably from domestic banks, for projects they otherwise would not consider.

While each project has been assessed for its development and financial additionality, UNCDF is also intent on using its transactions to create powerful demonstration effects, narrow the gap between the perceived and actual risks of supporting the missing middle and with a view to opening up new markets for private investors.

1.2. Methodology

The OECD-DAC has been reporting on the amounts mobilised from the private sector by official development finance3 since 2017. Until 2018, the OECD-DAC collected this data through ad-hoc surveys which examined five instruments: guarantees, syndicated loans, shares in collective investment vehicles (CIVs; see Box 1.6), direct investment in companies, and credit lines.4 The data covered 2012-2015 and was collected retrospectively.

In 2018, the OECD-DAC agreed on a methodology to measure two additional leverage mechanisms:

1. Project finance: special purpose vehicles (SPVs) are included as part of a new category “direct investment in companies and SPVs”.

2. Simple co-financing, such as public-private partnerships (PPPs).

These data have also been retroactively incorporated in an analysis covering 2012-2017, thereby expanding and updating the dataset since the publication of the 2018 Blended Finance in Least Developed Countries report (UNCDF, 2018[4]). This methodological improvement and integrations to the historical dataset explain the differences in the figures presented in this report and the 2018 report. The private finance mobilised dataset is continuously being updated due to staggered reporting by development finance providers.5 This chapter presents the latest data as of 1 April 2019, but further revisions are possible.

The analysis is based on the United Nations’ classification of least developed countries (UN, 2018[5]) as applicable in 2017, the last year of reporting covered in the dataset. The group thus comprises 48 LDCs, and includes Equatorial Guinea, even though it graduated in 2018.

Finally, the report also presents quantitative analysis contributed by Convergence,6 providing an additional perspective on blended finance in LDCs. Whereas the OECD information draws from the annual reporting exercise undertaken as part of the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) statistics, Convergence collects information from other credible public sources (e.g. press releases, case studies, news articles), as well as through data-sharing agreements and validation exercises with its members. In order to be included in Convergence’s database, the transaction must use concessional capital (public or philanthropic), whereas the OECD’s scope extends to all development finance, independent of the terms of its deployment. In fact, the six leveraging mechanisms are mostly market-oriented instruments. Another important difference is that Convergence captures the total deal size (including the development finance deployed) while the OECD only accounts for the amount of private finance mobilised in each operation.

The Convergence and OECD databases contain many of the same transactions. Given the current state of information sharing, it is not possible for either of them to be fully comprehensive. While some deals may be captured in both sources, the information collected is complementary. At times, the datasets may convey similar or different trends given their respective focuses, but together they help paint a fuller picture of what is happening when it comes to blended finance in LDCs.

1.3. The proportion of private finance going to LDCs remains relatively small, but stable

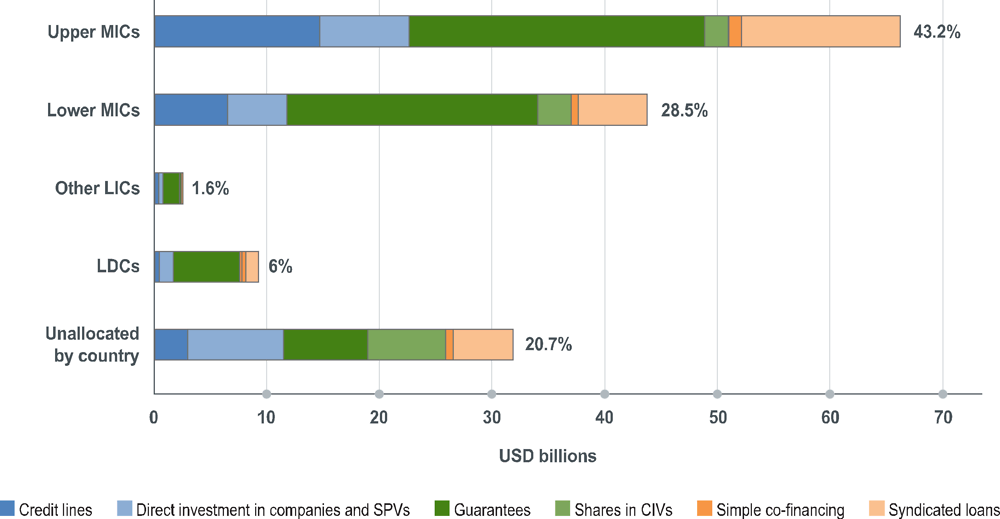

Of all private finance reported to the OECD as having been mobilised by official development finance interventions between 2012 and 2017, approximately USD 9.3 billion or 6% went to LDCs, whereas over 70% went to middle-income countries (Figure 1.2). Of the total USD 9.3 billion benefiting LDCs, USD 1.676 billion was mobilised in 2017.

Figure 1.2. Private capital mobilised by official development finance (2012-2017)

Note: LIC: low-income country; LMIC: lower middle-income country; UMIC: upper middle-income country; LDC: least developed country. The upper middle-income countries group includes Chile, Uruguay and the Seychelles, though they have since graduated from the DAC list of ODA recipients.

Source: (OECD, n.d.[6]), Statistics on amounts mobilised from the private sector by official development finance interventions as of 1st April 2019, http://www.oecd.org/development/stats/mobilisation.htm

Data gaps mean it is unclear whether this 6% is actually lower than the 7% of private finance mobilised for LDCs observed for 2012-2015. The data on the amounts mobilised by the International Finance Corporation (IFC) in 2016-2017 (USD10.3 billion) were not broken down by country for confidentiality reasons. In practice, all the amounts reported by IFC over the last two years are thus unallocated by income group.

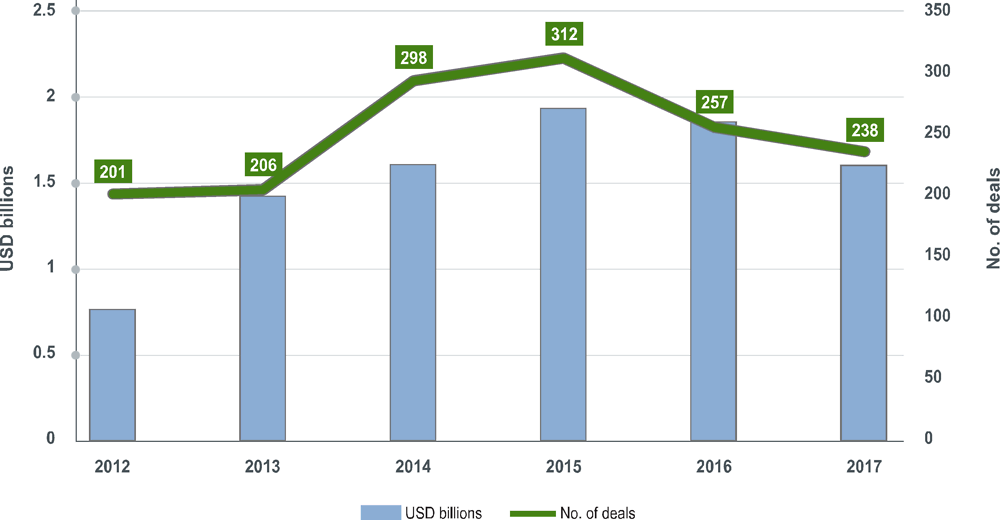

Figure 1.3 shows the six-year trend for private capital mobilisation in LDCs. As the IFC did not report country-level data for 2016-2017, it is still unclear whether the amount of private finance mobilised in LDCs is decreasing overall. Had IFC reporting been included, it is likely the aggregate trend would have been stable throughout the whole period.7 Box 1.3 presents trend data from the Convergence database which, as per the methodological note above, provide further useful insights into how blended finance transactions are touching down in LDCs.

Figure 1.3. Private finance mobilised in LDCs (2012-2017)

Note: As data from the new leverage mechanisms have been retroactively included in this analysis, the data for 2012-2015 differ from Figure 4 in (UNCDF, 2018[4]).

Source: (OECD, n.d.[6]), Statistics on amounts mobilised from the private sector by official development finance interventions as of 1st April 2019, http://www.oecd.org/development/stats/mobilisation.htm

Table 1.1 indicates the percentage of private finance mobilised in LDCs for each year, though the caveat on data availability for 2016-2017 makes it somewhat difficult to confirm any trends for these years.

Table 1.1. Private finance mobilised in LDCs and other developing countries

|

Year |

Private finance mobilised in LDCs USD billions |

Total private finance mobilised in all developing countries USD billions |

Private finance mobilised in LDCs as % of total |

|---|---|---|---|

|

2012 |

USD 0.752 |

USD 15.274 |

4.9% |

|

2013 |

USD 1.448 |

USD 19.363 |

7.5% |

|

2014 |

USD 1.677 |

USD 22.653 |

7.4% |

|

2015 |

USD 1.911 |

USD 27.674 |

6.9% |

|

2016 |

USD 1.803 |

USD 34.272 |

5.3% |

|

2017 |

USD 1.676 |

USD 34.685 |

4.8% |

Source: (OECD, n.d.[6]), Statistics on amounts mobilised from the private sector by official development finance interventions as of 1st April 2019, http://www.oecd.org/development/stats/mobilisation.htm

Box 1.3. The importance of concessionality for blending in least developed countries

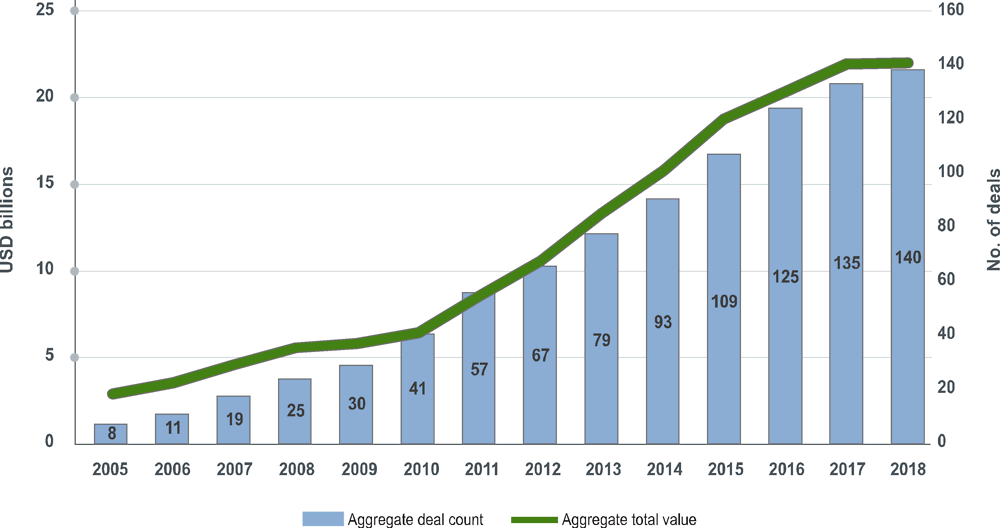

As of May 2019, the Convergence database captures 440 blended finance transactions that include the use of either public or philanthropic concessional funding to catalyse private sector investment in SDG-related investments in developing countries (see Section 1.2). According to this source, one in three concessional blended finance transactions, i.e. 140, targeted one or more least developed countries (LDCs). The majority of them (40%) exclusively focused on LDCs, with another 25% having a primary focus on LDCs.

Overall, Convergence estimates that, since 2005, up to USD 15.5 billion in capital has been earmarked for LDCs through blended finance. Blended finance transactions targeting one or more LDCs, either exclusively or in part, have accounted for only 12% of the aggregate volume to date, in part because these transactions have been smaller, on average, than all blended finance deals (USD 164 million versus USD 301 million across the entire database). Figure 1.4 illustrates that there has been accelerating growth in the cumulative number and aggregate value of blended finance transactions targeting one or more LDCs since 2010.

Blended finance solutions come in many shapes and sizes. The majority of these blended finance transactions targeting LDCs in part or full were funds (e.g. debt or equity funds, at 45%), followed by projects (e.g. infrastructure projects or health programmes, at 27%), and companies (e.g. social enterprises or alternative finance companies, at 18%).

Figure 1.4. Cumulative blended finance targeting least developed countries (Convergence)

Note: Convergence tracks country data by stated countries of focus at the time of financial close, not actual investment flows. Often, countries of eligibility are broader than those explicitly stated.

1.4. Blended finance approaches have expanded to additional least developed countries

Of the 48 countries categorised as LDCs, 43 benefited from private finance mobilised by official development finance at least once over 2012-2017 (Figure 1.6). Compared to the previous report, private finance mobilised was also reported in Equatorial Guinea, Vanuatu and Somalia during the last two years.9

The regional volumes of private capital mobilised continue to reflect the number of LDCs located within the region. The LDCs in the sub-Saharan Africa region collectively received the biggest share of private finance mobilised, at approximately 70% in 2012-2017. However, in 2016-2017, LDCs in sub-Saharan Africa received a lower share of private finance (58%), while Asian LDCs (predominantly South and Central Asia) represented 41%. Central America received under 1% of private finance mobilised, reflecting the fact that only one LDC (Haiti) is located in this region.

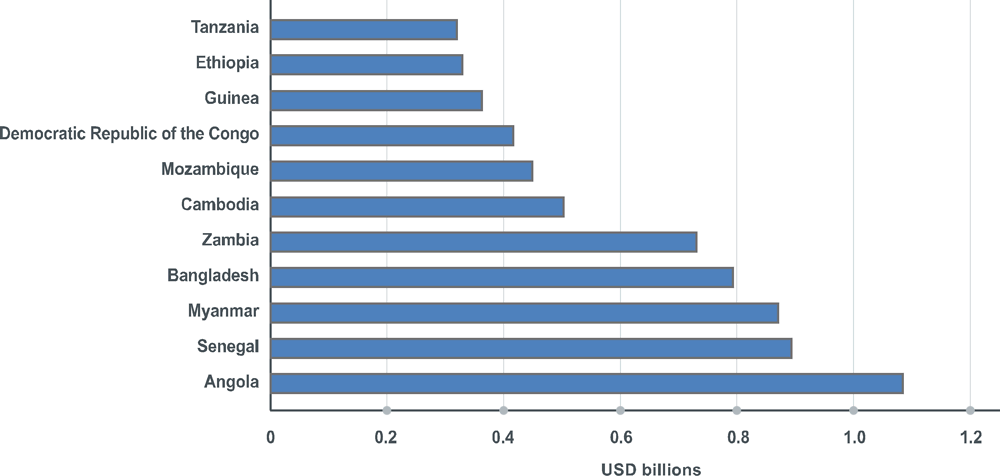

Figure 1.5 shows the top recipient countries for the time period 2012-2017. Angola remains the largest recipient of private finance mobilised for 2012-2017, mostly due to a few large transactions, and so this may not be a predictor of future trends (UNCDF, 2018[4]). Senegal, Bangladesh, Zambia, Cambodia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo – in descending order of volumes mobilised – also figure among the top 10 recipients for the whole time series. Myanmar more recently appeared as an important recipient of private finance mobilised, with two large deals in the telecommunications industry during the last two years. Overall, LDCs benefiting from the most private finance mobilised tend to be those with larger economies10 and/or those with large natural resource endowments.

Figure 1.5. Top 10 least developed country recipients of private finance mobilised (2012-2017)

Source: (OECD, n.d.[6]), Statistics on amounts mobilised from the private sector by official development finance interventions as of 1st April 2019, http://www.oecd.org/development/stats/mobilisation.htm

In 2012-2015, the eight LDCs with no private capital mobilised were mostly small islands and conflict-afflicted states. In 2016-2017, of the nine LDCs with no private capital,11 five were fragile contexts according to the OECD multidimensional fragility framework (OECD, 2018[8]): Central African Republic, Eritrea, South Sudan and Yemen, and Comoros was scored as severely fragile for its economic environment and security. Five countries received no private finance mobilised throughout the six-year period: Central African Republic, Comoros, Eritrea, Kiribati and Tuvalu. For further insights into making blended finance work in fragile contexts, see Guest Piece 2.6 by Izabella Toth (Cordaid) and Romy Miyashiro (Cordaid Investment Management BV).

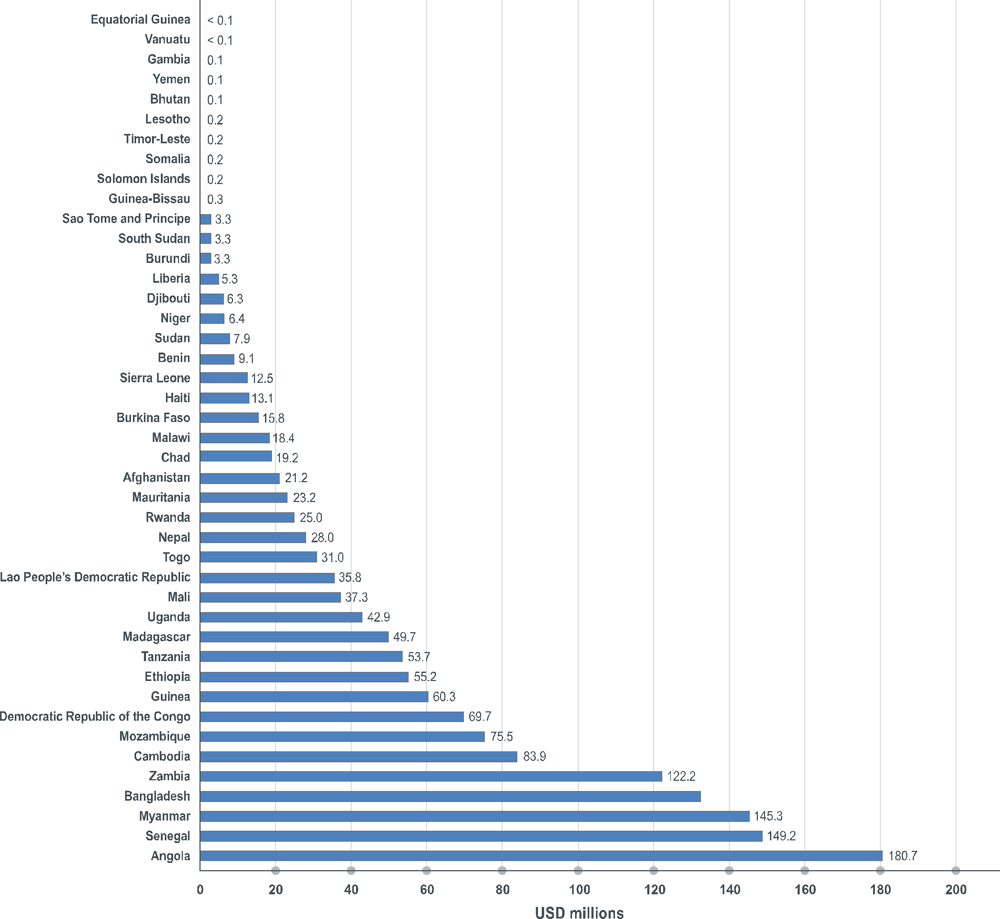

Figure 1.6 shows an overview of the average annual amounts mobilised in each LDC for the full period 2012-2017 (see also Box 1.4 on average deal size).

Figure 1.6. Average annual amount of private finance mobilised per least developed country (2012‑2017)

Source: (OECD, n.d.[6]), Statistics on amounts mobilised from the private sector by official development finance interventions as of 1st April 2019, http://www.oecd.org/development/stats/mobilisation.htm

Further analysis indicates that Angola, Mauritania and Guinea achieved the highest volumes of private finance mobilised on average per deal over the six years. Despite the limited number of transactions, Angola ranks first with USD 51.6 million mobilised on average per deal in 2012-2017. This was driven by two large operations in river basin development and public sector policy and administrative management. There were only four deals in Mauritania, which shows the second largest average amount of private finance mobilised per deal, USD 34.9 million. Guinea comes in third, with 24 deals, mobilising on average USD 15 million per deal.

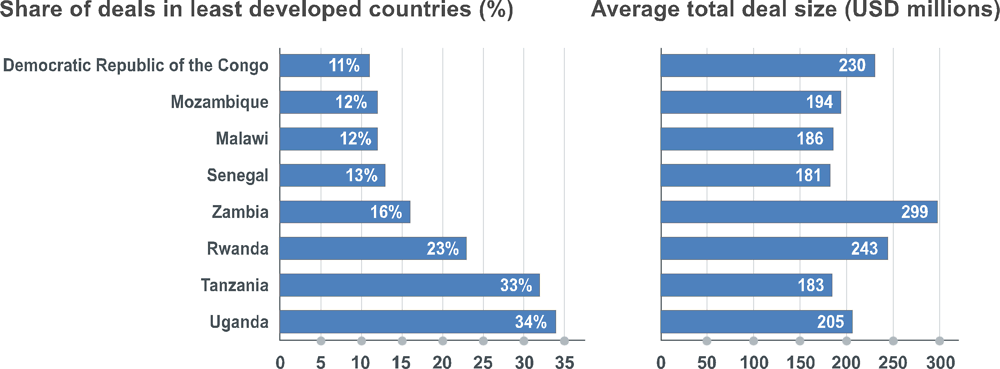

Box 1.4. Historical blended finance transactions targeting least developed countries are even more concentrated on sub-Saharan Africa

Blended finance transactions vary significantly in geographical scope, from a single-country infrastructure project to a global equity fund. According to Convergence data, the vast majority (88%) of blended finance transactions targeting one or more LDCs since 2005 focus on the sub-Saharan Africa region.

Within sub-Saharan Africa, the most frequently targeted LDCs have been Uganda, Tanzania, Rwanda, Zambia, Senegal, Malawi, Mozambique, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Figure 1.7). The first two – Uganda and Tanzania – are also among the top five developing countries globally most frequently targeted by blended finance deals.

Figure 1.7. Top least developed countries benefiting from concessional blended finance transactions (Convergence)

Note: Convergence tracks country data by stated countries of focus at the time of financial close, not actual investment flows. Often, countries of eligibility are broader than those explicitly stated. Totals in the “proportion of deals in LDCs” are more than 100% as deals can take place in more than one country.

While the top recipients in Figure 1.6 and Figure 1.7 are not identical, the two sources agree that Zambia, Senegal, Mozambique and the Democratic Republic of the Congo are among the top LDCs for blended finance. The differences in country ranking may be attributable to methodological differences, but also to the fact that Convergence data cover a longer timeframe, dating back to 2005.

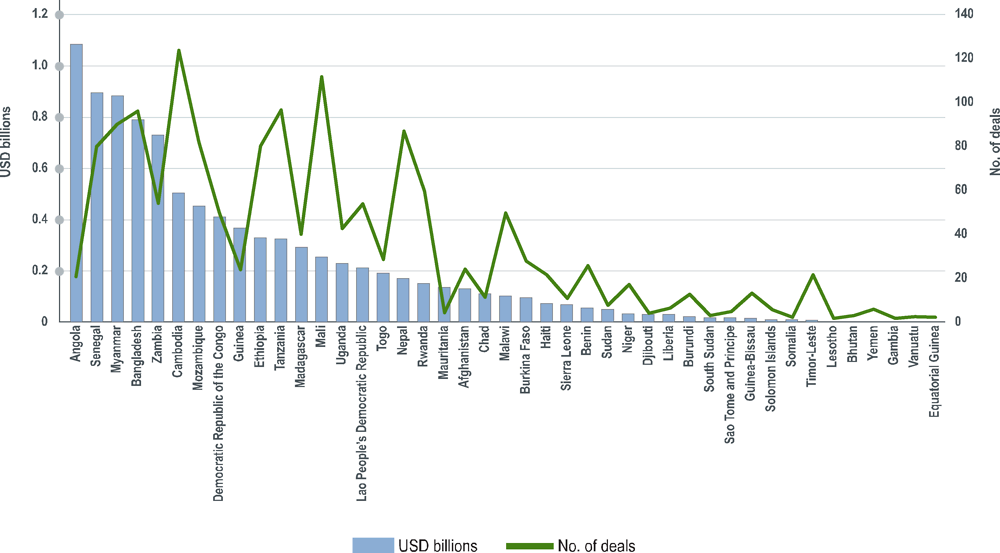

The OECD database also shows that the amount of private finance mobilised and number of deals varies significantly among LDCs (Figure 1.8). The top five recipients (Angola, Senegal, Myanmar, Bangladesh, and Zambia) in 2012-2017 together received approximately 44% of the total volume of private finance mobilised and almost 22.5% of all deals in the LDCs. Overall, the top 10 deals represented over 25% of all private finance mobilised in LDCs.

While the number of deals in Guinea was limited, two of them were big ticket items: a guarantee of USD 100 million for fossil fuel electric power plants with carbon capture storage and a USD 150 million guarantee for a nonferrous metals project. In addition, one deal in Myanmar (a guarantee valued at USD 450 million for telecommunications) represents over 12% of all private finance mobilised in LDCs. This suggests that blended finance transactions tend to be geographically concentrated and that some countries are able to attract larger investments than others.

Figure 1.8. Total amounts mobilised and number of deals by LDC (2012-2017)

Source: (OECD, n.d.[6]), Statistics on amounts mobilised from the private sector by official development finance interventions as of 1st April 2019, http://www.oecd.org/development/stats/mobilisation.htm

1.5. Deals vary across countries by number and size

The six-year dataset further suggests that larger volumes of mobilisation may be harder to achieve in LDCs than in middle-income countries, possibly due to the smaller size of private-sector transactions and/or the higher use of concessional finance per transaction. Over 2012-2017, the average amount of private finance mobilised per deal in LDCs was USD 6.1 million, compared to USD 27 million in lower middle‑income countries and over USD 60 million in upper middle-income countries (Table 1.2).

Table 1.2. Number of deals and average mobilisation by country income group (2012-2017)

|

|

Unallocated |

LDCs |

Other LICs |

LMICs |

UMICs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

No. of deals |

565 |

1 513 |

179 |

1 608 |

1 087 |

|

Average amount of private finance mobilised per deal (USD millions) |

56.5 |

6.1 |

13.9 |

27.3 |

61 |

|

Total private finance mobilised (USD billions) |

31.9 |

9.3 |

2.5 |

43.9 |

66.4 |

Note: LIC: low-income countries; LMIC: lower middle-income countries; UMIC: upper middle-income countries; LDC: least developed countries

Source: (OECD, n.d.[6]), Statistics on amounts mobilised from the private sector by official development finance interventions as of 1st April 2019, http://www.oecd.org/development/stats/mobilisation.htm

1.6. Blended finance and ODA seem linked, but ODA plays a unique role

The geographic breakdown of ODA recipients is broadly similar to that of private finance mobilisation, with sub-Saharan Africa and Asia (mostly South and Central) receiving 62% and 31% respectively of all ODA in 2012-2017. The highest ODA recipients partially overlap with those who receive the highest amount of mobilised private finance: 5 countries (namely Ethiopia, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Mozambique and the Democratic Republic of the Congo) feature in the top 10 of both ODA and private finance mobilised over 2012-2017.

In examining the relationship between ODA and private finance mobilised, the OECD found a weak but positive relationship. This relationship might be a result of an increased focus on the use of ODA to mobilise private finance for sustainable development. ODA is also going to those five LDCs where no private finance has been mobilised. This confirms the continuing and essential role of ODA for delivering on the promise of leaving no one behind. It also highlights the concern that, if blended finance becomes an increasingly important development co-operation approach, development partners will need to ensure this is not at the expense of support for LDCs and other vulnerable contexts, where blending is more challenging.

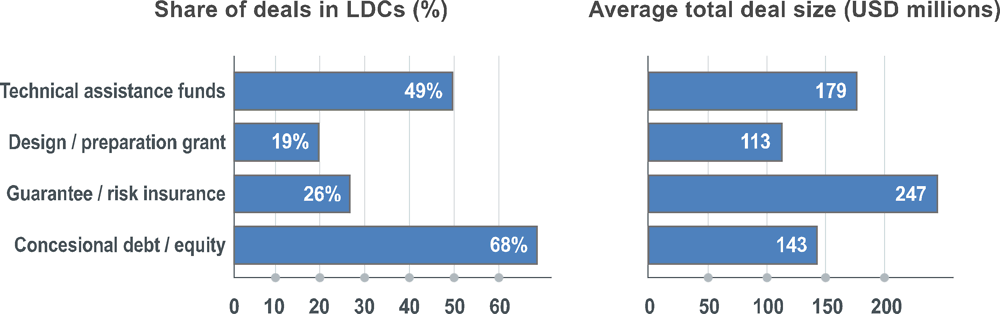

While the OECD definition - and hence also its data - extends blending to all development finance, independent of the terms of its deployment, the 2018 report highlighted the importance of concessional finance in making blended transactions work in LDCs. Convergence identifies four ways in which concessional capital can be deployed by public and/or philanthropic actors to mobilise additional financing for the SDGs in developing countries (i.e. through concessional debt or equity, guarantees or risk insurance, design/preparation grants, and technical assistance funds). Box 1.5 shows that technical assistance is more likely to be deployed and that concessional resources represent a larger share of the total transaction in LDCs compared to other developing countries.

Box 1.5. The use of concessional resources for blended finance transactions in LDCs

According to Convergence, nearly 70% of blended finance transactions targeting one or more LDCs have benefited from concessional debt or equity (e.g. investment-stage grant, first-loss capital) since 2005. Compared to blended finance transactions in other developing countries, transactions targeting one or more LDCs are more likely to deploy technical assistance alongside investment capital (49% versus 38% of all transactions). In LDCs as in other developing countries, guarantees are associated with larger average deal sizes.

Blended finance transactions targeting one or more LDCs have seen a larger share of concessional resources as a proportion of the total transaction size. Convergence reviewed the leverage ratio (i.e. total non-concessional capital mobilised divided by total concessional capital provided) for a sample of blended finance operations targeting one or more LDCs. Based on this estimate, transactions focused on LDCs show a lower average leverage ratio: for every one dollar of concessional financing only USD 2.80 of non‑concessional capital was mobilised, compared to the average of USD 4.00 across all operations included in Convergence’s 2018 Brief (Convergence, 2019[9]).

Figure 1.9. The type and size of concessional blended finance deals in least developed countries (Convergence)

Note: Convergence tracks country data by stated countries of focus at the time of financial close, not actual investment flows. Often, countries of eligibility are broader than those explicitly stated. Totals in the “proportion of deals in LDCs” are more than 100% as deals can take place in more than one country. Percentages based on all deals in the Convergence database targeting one or more LDC.

Source: (Convergence, 2019[9]), “Leverage of concessional capital”, https://www.convergence.finance/knowledge/ 35t8IVft5uYMOGOaQ42qgS/view

The findings from Box 1.5 are broadly consistent with those presented in Section 1.5 above and Table 1.3 below. They further suggest that guarantees have been associated with greater mobilisation and that it has been more difficult to mobilise private finance for LDCs, compared to middle income countries, through blended finance.

The identification of and support for bankable projects in LDCs can be challenging and time-consuming, but this work is essential to generate investable opportunities. The Guest Piece by Bettina Prato (Smallholder and Agri-SME Finance and Investment Network, IFAD) and Dagmawi Habte Selassie (IFAD) in Section 2.1 highlights the importance of technical assistance, including for strengthening investees’ capacity in areas like environmental, social and governance (ESG) compliance and improved operational efficiency.

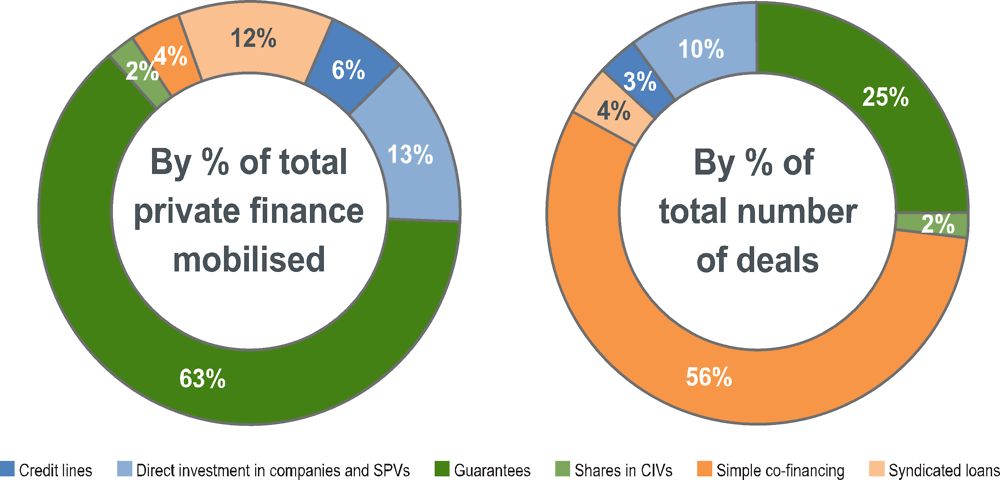

1.7. Guarantees are the most powerful leveraging mechanisms, but simple co‑financing agreements are the most used

Credit and risk guarantees continue to be the instruments that have mobilised the most private finance in absolute terms, at 63% of the total volume reported in 2012-2017 (Figure 1.10). Guarantees represent over 55% of all private finance mobilised in every year excluding 2017, when guarantees fell to 44% of private finance mobilised. This could point to an increased diversification of the blended finance mechanisms used in LDCs. Total amounts reported as mobilised from direct investments in companies registered a slight increase over the full time period, from representing 18% of private finance mobilised in 2012, to over 21% in 2017. The number of operations based on guarantees also decreased, representing 35% of deals in 2012 but only 15% in 2017, in favour of direct investment in companies and SPVs and simple co-financing. Guarantees were used in 35 LDCs to mobilise private finance. However, 5 countries - Angola, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Senegal and Zambia - received over half of all private finance mobilised through guarantees.

Simple co-financing arrangements represent the largest number of deals overall, but mobilised a relatively small share of private capital, i.e. 4% over 2012-2017. Acquiring shares in collective investment vehicles (CIVs) remains a minor leveraging mechanism in LDCs: it represents the fewest deals and the smallest volume of mobilised private capital over the whole time series. The use of CIVs is further explored by complementary OECD research, as described in Box 1.6.

Figure 1.10. Leverage mechanisms in least developed countries (2012–2017)

Source: (OECD, n.d.[6]), Statistics on amounts mobilised from the private sector by official development finance interventions as of 1st April 2019, http://www.oecd.org/development/stats/mobilisation.htm

Box 1.6. Insights from the OECD 2018 Blended Finance Funds and Facilities survey

Blended finance funds and facilities, also referred to as collective investment vehicles (CIVs), are an important channel for blending as well as a primary driver of innovation. The OECD distinguished between two different models of CIVs:

A fund is a pool of commercial, or both development and commercial, capital to collectively supply financial resources to projects or companies. Funds can be structured in two ways, either in a flat structure where risks and returns are allocated equally to all investors, or in a layered structure where risks and returns are allocated differently across investors. This category includes private equity funds, fixed income funds, some special purpose vehicles, and other fund-like structures.

A facility is an earmarked allocation of public development resources (sometimes including support from philanthropies), which can invest in development projects through a range of instruments, including by purchasing shares in collective vehicles such as funds.

While the OECD data on private finance mobilised aims to capture information on leverage at the operations level, the OECD work on blended finance funds and facilities provides complementary information by examining the composition of such vehicles at the capital level.

Based on the latest survey, blended finance vehicles invested USD 7.6 billion in LDCs in 2017, out of a total of USD 41 billion, where information by country was available. This amount comprises both development finance (concessional or not) and commercial capital – the latter amounting to USD 340 million. This amount corresponds to roughly 7.5% of the total USD 4.5 billion in commercial capital mobilised by flat and structured funds across all developing countries in 2017. This share is roughly consistent with that observed in the OECD private finance mobilised dataset over 2012-2017.

The 180 blended finance vehicles surveyed invest in a total of 25 LDCs, with Uganda, Zambia, Tanzania, Ethiopia and Cambodia capturing most of the investment volume. No investments were reported in Kiribati or Lesotho by the blended finance CIVs or by official donors as private finance mobilised. According to both sources, Bhutan, South Sudan and Comoros received very limited amounts.

Source: (Basile and Dutra, forthcoming[10]), OECD Blended Finance Funds and Facilities 2018 Survey results.

As mentioned earlier, the amount mobilised by each instrument over six years is significantly lower in LDCs than in upper and lower middle-income countries. Table 1.3 compares the average amount mobilised per instrument per deal in LDCs from 2012-2017 with all other developing countries. The average volume mobilised in LDCs is consistently lower for all leveraging mechanisms. Interestingly, in LDCs syndicated loans mobilised more private finance per deal on average than guarantees. This reflects the large variation in the amounts mobilised by guarantees, with 81 out of 380 deals mobilising under USD 1 million and the top 10 deals representing approximately 39% of all private finance mobilised by guarantees.

Table 1.3. Annual private finance mobilised per deal by leverage mechanism (2012-2017)

|

|

LDCs (USD millions) |

Other developing countries (USD millions) |

|---|---|---|

|

Credit lines |

10.3 |

92.9 |

|

Direct investment in companies and SPVs |

8.3 |

39.6 |

|

Guarantees |

15.4 |

73.6 |

|

Shares in CIVs |

7.2 |

28.9 |

|

Simple co-financing |

0.4 |

2.5 |

|

Syndicated loans |

17.7 |

63.3 |

Note: CIVs: collective investment vehicles; SPVs: special purpose vehicles.

Source: (OECD, n.d.[6]), Statistics on amounts mobilised from the private sector by official development finance interventions as of 1st April 2019, http://www.oecd.org/development/stats/mobilisation.htm

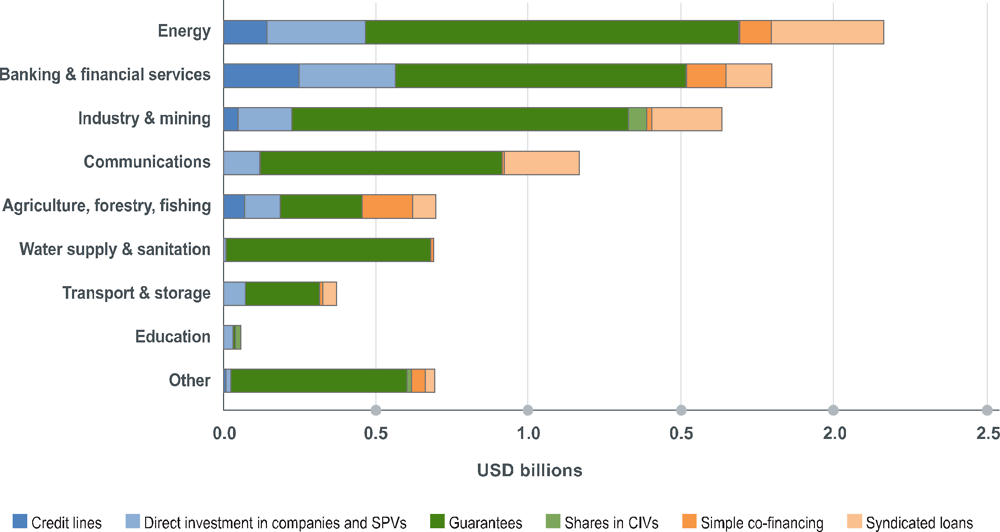

1.8. Energy, banking and financial services mobilise the most private finance

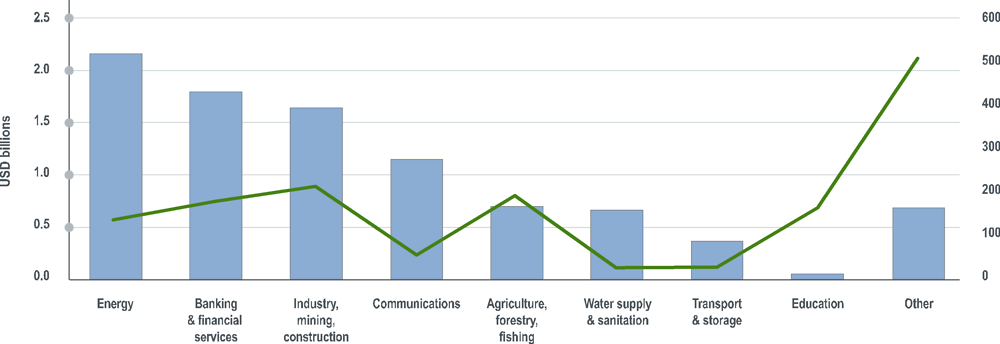

Over 2012-2017, the energy and banking and financial services sectors in LDCs are confirmed as the largest recipient sectors, representing 23% (USD 2.16 billion) and 19% (USD 1.8 billion) of all private finance mobilised respectively. In the last two years, these sectors received even greater focus, with energy representing 30% of the USD 3.48 billion in private finance mobilised in LDCs and banking and financial services sector 24%.

Industry and mining was the third largest sector over 2012-2017, representing 17.6% or USD 1.6 billion of all private finance mobilised in LDCs. Communications followed as the fourth largest sector, representing 12.6% or USD 1.16 billion of private finance mobilised.

As illustrated in Figure 1.11, trends over the six-year period show that guarantees are a prominent leveraging mechanism in almost every sector (excluding education), whereas direct investments and syndicated loans mobilise larger amounts in areas with clear revenue streams.

Figure 1.11. Private finance mobilised by sector in least developed countries (2012-2017)

Source: (OECD, n.d.[6]), Statistics on amounts mobilised from the private sector by official development finance interventions as of 1st April 2019, http://www.oecd.org/development/stats/mobilisation.htm

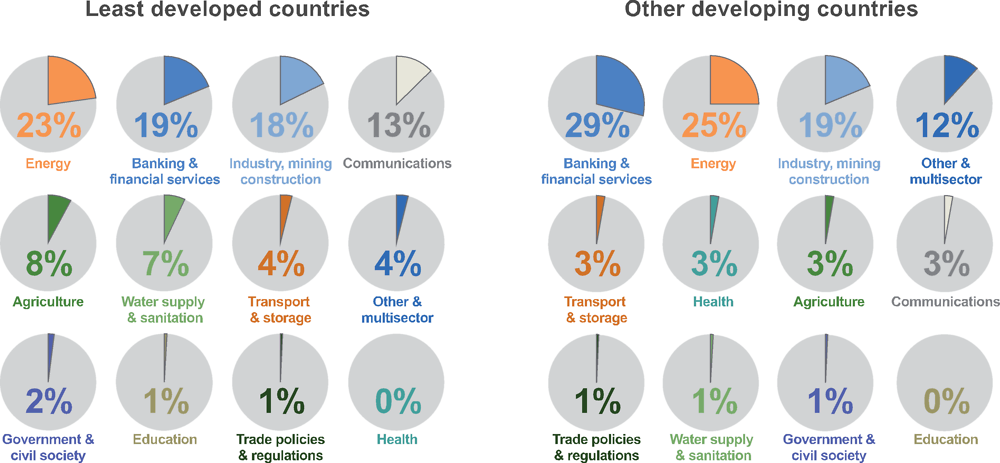

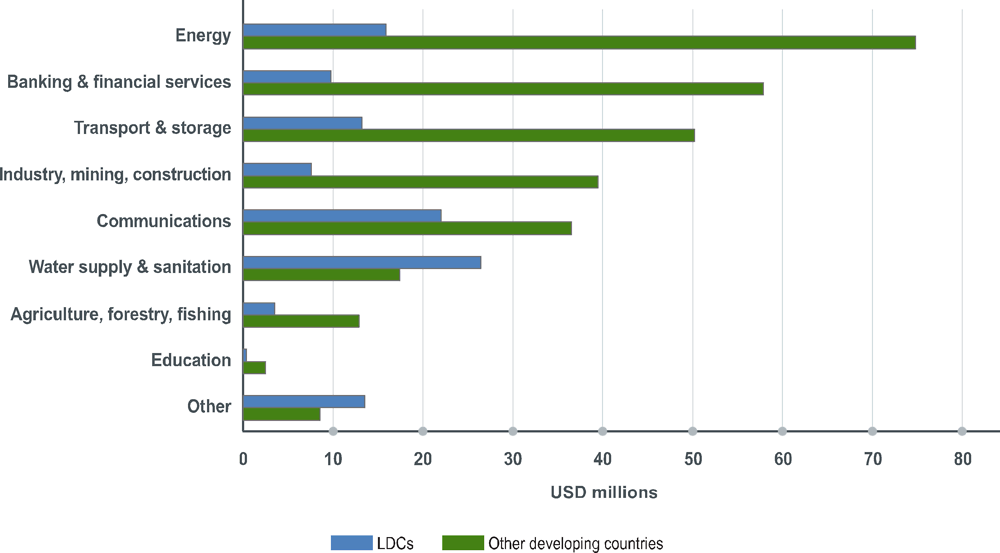

Figure 1.12 confirms the findings from the 2018 report that energy, banking and financial services are also the largest sectors for private finance mobilised in both LDCs and other developing countries (UNCDF, 2018[4]). Indeed, energy, banking and financial services are consistently amongst the top sectors of private finance mobilised for both groups of countries almost every year.12

Figure 1.12. Private finance mobilised by sector in least developed countries and other developing countries (2012‑2017)

Source: (OECD, n.d.[6]), Statistics on amounts mobilised from the private sector by official development finance interventions as of 1st April 2019, http://www.oecd.org/development/stats/mobilisation.htm

In terms of the energy sector breakdown, between 2012 and 2017, over 40% of private finance mobilised went to natural gas and oil-fired electric power plants. Another 10% went to fossil fuel electric power plants with carbon capture storage and other non-renewable sources. Renewable energy (hydroelectric power, solar, wind, geothermal, and multiple technologies) was more prominent in other developing countries than in LDCs (57% of private finance mobilised in energy compared to 42% in LDCs).

In the banking and financial services sector, 92% of private finance was mobilised for financial intermediaries in LDCs and 7% for financial policy and administrative assistance. SME development was the largest subsector and received 34% of all private finance mobilised to industry, mining and construction, followed by oil and gas (16%) and nonferrous metals (14%). Over 99% of the private finance mobilised in the communications sector over 2012-2017 was mobilised in the telecommunications industry, which includes telephone networks, telecommunication satellites, and earth stations.

From 2012-2017, the majority of the USD 58.79 million private finance mobilised in the education sector went to building education facilities and training (52%), followed by vocational training (19%) and education policy and administrative management (13%). Very little private finance was mobilised in the health sector, which represents under 0.5% of private finance mobilised in LDCs from 2012-2017 (categorised as other in Figure 1.11). For further insights into the potential of blended finance in the health sector, see the Guest Piece in Section 2.3 by Priya Sharma.

In terms of number of deals, industry, mining and construction received the most deals over the six-year period, but with a fairly low mobilisation (USD 7.6 million per deal on average). Water supply and sanitation reported the highest mobilisation per deal, USD 26.2 million, driven by the large transaction on river basin development in Angola.

Figure 1.13 breaks down the amounts mobilised by sector and number of deals for 2012-2017. The graph indicates that whilst communications, water supply and sanitation benefited from the fewest number of deals, they achieved higher levels of mobilisation on average than other sectors. The largest average amounts of private finance mobilised per transaction were in the communications sector at USD 36 million – again skewed by two large transactions – and transport at USD 25 million. In the energy sector the average amounts of private finance mobilised was USD 15.6 million, USD 11 million in the banking and financial services sector and USD 9.6 million in industry, mining and construction.

Figure 1.13. Private finance mobilised in LDCs by deal and sector (2012-2017)

Note: *the category “Other” combines amounts reported under multisector, business & other services, general environment protection and disaster prevention, population, other social infrastructure, government, health, water and sanitation, tourism and unallocated.

Source: (OECD, n.d.[6]), Statistics on amounts mobilised from the private sector by official development finance interventions as of 1st April 2019, http://www.oecd.org/development/stats/mobilisation.htm

Compared to other developing countries, the amount of private finance mobilised per deal is substantially smaller across all sectors in LDCs, except water supply and sanitation (Figure 1.14). For example, during 2012-2017, the average energy deal mobilised over four times as much private finance (USD 70 million) in other developing countries and nearly six times in banking and financial services (USD 57 million) compared to LDCs. The average deal size in LDCs for water and sanitation is skewed by one large transaction in Angola which represents over 98% of private finance mobilised in the sector and over 7% of all private finance mobilised in LDCs for the full time period.

Figure 1.14. Average amounts mobilised in least developed countries per deal by sector (2012‑2017)

Source: (OECD, n.d.[6]), Statistics on amounts mobilised from the private sector by official development finance interventions as of 1st April 2019, http://www.oecd.org/development/stats/mobilisation.htm

As important as it is to understand which sectors are being targeted by blended finance operations, it is also essential to understand the impact these deals are having on achieving the SDGs. Ensuring development additionality has been one of the main points of concern in blended projects. See the Guest Piece in Section 2.5 by Jean-Philippe de Schrevel (Bamboo Capital Partners) for a discussion of how important it is to improve impact measurement.

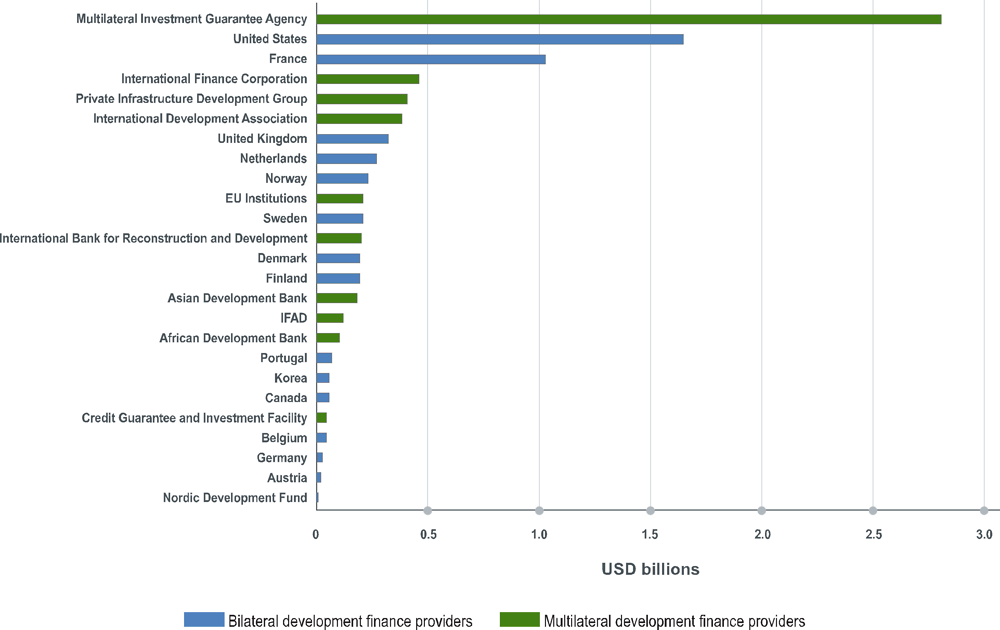

1.9. Bilateral providers are becoming more prominent in the LDC blended finance market

Once again, the largest amounts of private finance mobilised in LDCs were reported by multilateral donors (Figure 1.15). They mobilised USD 5.2 billion or 56% of all private finance from 2012-2017, compared to USD 4 billion or 43% mobilised by bilateral donors. However, bilateral channels are playing an important role in mobilising private capital in LDCs.

Figure 1.15. Average annual amount mobilised in least developed countries per provider (2012‑2017)

Note: Ireland, Luxembourg, Czech Republic, Switzerland, Slovak Republic, Australia reported less than USD 5 million in private finance mobilised. Other DAC members, not listed in the above, did not report on amounts mobilised from the private sector.

Source: (OECD, n.d.[6]), Statistics on amounts mobilised from the private sector by official development finance interventions as of 1st April 2019, http://www.oecd.org/development/stats/mobilisation.htm

The Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) is the largest mobiliser of private finance for LDCs over the six-year period. The IFC also plays a prominent role, ranking 4th overall for the full 2012-2017 period, despite claiming no mobilisation in LDCs for the first two years and despite the unavailability of country-level data for the last two years. For further insights into how the World Bank Group is working to catalyse private sector investment in the world’s poorest countries, see the Guest Piece in Section 2.7 by Federica Dal Bono and Barbara Lee.

The US and France are among the largest players for blending in LDCs. The UK, Finland, Denmark and the Netherlands mobilised significantly more private capital in LDCs in 2017 than in 2012. In addition, data from 2016-2017 indicate that Canada and Korea are emerging as new players in the field.

Figure 1.16 reveals the growing prominence of bilateral donors in mobilising private capital in LDCs. The annual average amount of private finance mobilised in LDCs but the United States, France, United Kingdom, Finland, Denmark, Netherlands and Sweden has increased between 2012 and 2017. The reduction in prominence of multilaterals could be because of IFC’s reporting gaps, however.

Figure 1.16. Bilateral and multilateral channels for blending in least developed countries (2012‑2017)

Note: Percentages refer to the proportion of private finance mobilised reported by each type of development finance provider over the total amounts reported as mobilised in LDCs.

Source: (OECD, n.d.[6]), Statistics on amounts mobilised from the private sector by official development finance interventions as of 1st April 2019, http://www.oecd.org/development/stats/mobilisation.htm

In terms of geographical concentration, 16 of the 48 LDCs13 each attracted blending operations by 10 or more donors in 2012-2017. As a consequence, these countries dominate the top ranking of recipients of private finance mobilised for LDCs. Five LDCs14 only benefited from deals from one donor, and this is reflected in the small amounts mobilised in those countries.

Looking at how much each donor succeeded in mobilising in LDCs compared to other developing countries may reveal the priority of LDCs in their blending strategies. From 2012-2017 Portugal was the country that saw the highest percentage of all the private finance it mobilised benefitting LDCs, at 76% (USD 72 million) of all mobilisation reported by Portugal across all developing countries. This was followed by IFAD at 59% (USD 118 million). Over half of the private finance mobilised by both Korea and Finland was in LDCs.

MIGA mobilised over USD 2.8 billion for LDCs in 2012-2017 (Figure 1.15), representing 14% of all the private finance it mobilised. The United States mobilised approximately USD 1.6 billion for LDCs over 2012-2017 (mostly focused on Guinea, Zambia, Cambodia and Senegal). This was the largest amount of all bilateral donors, and represented 6% of the private finance mobilised by the US overall. Almost half of the USD 1 billion mobilised bilaterally by France in 2012-2017 was for Madagascar, Senegal and Mali. The USD 324 million mobilised by the UK was mostly invested in Zambia, Bangladesh and Uganda. The Netherlands, Norway, Sweden all mobilised over USD 200 million for LDCs from 2012-2017. All the other bilateral development finance providers each mobilised less than USD 200 million of private finance in LDCs during the six years.

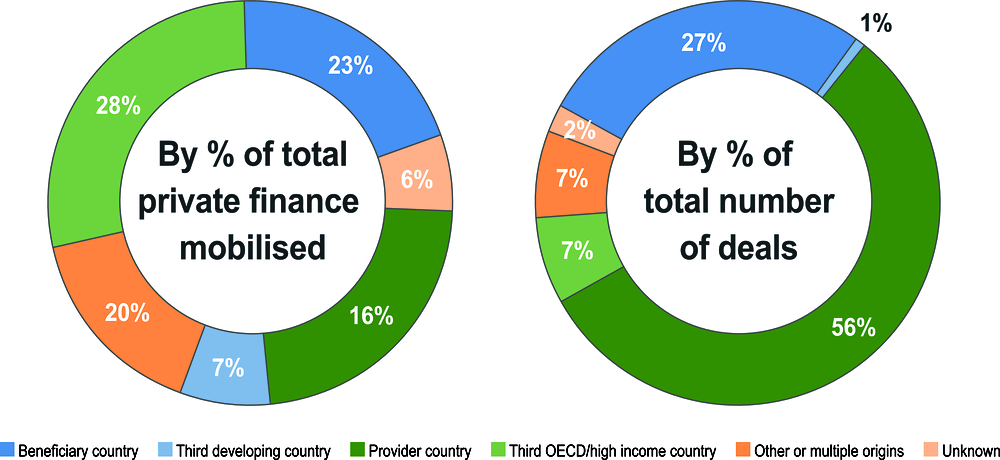

1.10. In LDCs, investors from high-income countries are being more mobilised than domestic ones

Over the six-year period, most blended finance operations reported in LDCs mobilised private capital from high-income countries. Yet, private finance mobilised domestically, i.e. within beneficiary LDCs, has decreased. The involvement of the domestic private sector can be especially important in deepening financial markets and supporting country ownership. For further insights into the question of ownership, see the Guest Piece in Section 2.2 by Andrea Ordóñez (Southern Voice).

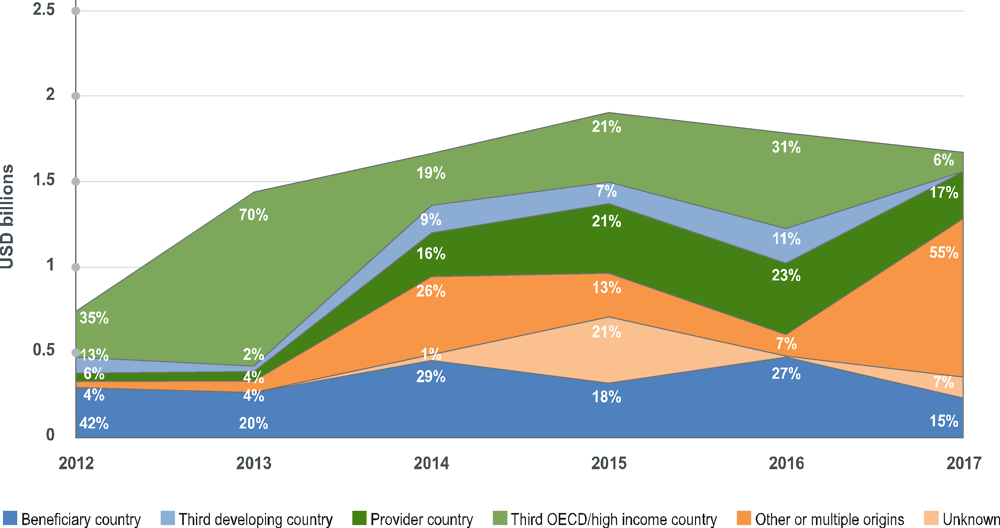

While beneficiary countries remain a significant source of additional capital, both in volume and number of transactions, their importance has diminished from 42% of finance mobilised in 2012 to 14% in 2017. Private financing sourced from third developing countries also remains low (Figure 1.17 and Figure 1.18).

Figure 1.17. Sources of private finance mobilised in least developed countries (2012-2017)

Note: The definition of the origins of the funds follows the Balance of Payments’ residence principle. Residence is not based on nationality or legal criteria, but on the transactor’s centre of economic interest: an institutional unit has a centre of economic interest and is a resident unit of a country when, from some location (dwelling, place of production, or other premises) within the economic territory of the country, the unit engages and intends to continue engaging (indefinitely or for a finite period) in economic activities and transactions on a significant scale.

Source: (OECD, n.d.[6]), Statistics on amounts mobilised from the private sector by official development finance interventions as of 1st April 2019, http://www.oecd.org/development/stats/mobilisation.htm

The LDCs most successful in mobilising domestic private investors were Senegal, Zambia, Madagascar, Mozambique and the United Republic of Tanzania (“Tanzania”), representing over 41% of the USD 2.16 billion in local capital mobilised by LDCs over the six years. However, the average mobilisation per deal from beneficiary countries appears to have increased. In fact, the average amount mobilised per transaction from domestic investors in LDCs increased from USD 4.5 million in 2012 to USD 5.8 million in 2017. France was the largest domestic finance mobiliser, representing 42% of all domestic finance mobilised from 2012-2017, followed by the United States (19%) and the EU (10%).

Over USD 4.1 billion or 44.5% of all private finance mobilised in LDCs from 2012-2017 originated from the provider or another high-income country. Because the OECD data do not include any information on the conditions that lead to the selection of the private partner, it is impossible to determine if these volumes are ascribable to tied aid.15

Figure 1.18 displays the trends for origin of finance mobilised over the six-year period. The figure indicates that finance from beneficiary and third high-income countries has fallen in recent years.

Figure 1.18. Trend in sources of private finance mobilised in least developed countries (2012-2017)

Note: Percentages refer to the proportion mobilised from each source of private finance over the total amounts reported as mobilised in LDCs.

Source: (OECD, n.d.[6]), Statistics on amounts mobilised from the private sector by official development finance interventions as of 1st April 2019, http://www.oecd.org/development/stats/mobilisation.htm

Regional analysis of the sources of private finance mobilised in LDCs indicates that 57% of private finance mobilised from third high-income countries over six years went to sub-Saharan Africa and the remaining went to Asia. Sub-Saharan Africa benefited from 83% of the amounts mobilised from beneficiary countries themselves. Moreover, provider countries represented a slightly higher source of private finance mobilised in LDCs (16%) than other developing countries (14%). Similarly, third high-income countries played a more important role in LDCs (providing 28% of total private finance mobilised in 2012-2017) than in other developing countries (at 18% of the total).

Seventy-five percent of foreign sources of finance mobilised (other or multiple origins, third developing country, provider country and third high-income country) benefited four sectors: energy (26.5%), industry, mining and construction (17%), communications (16.6%) and banking and financial services (14.5%).

Guarantees played a key role in mobilising private finance from every source over 2012-2017. Direct investments in companies and SPVs are also quite versatile, playing a significant role in mobilising private finance from provider countries and from the other or multiple origins category. Credit lines are typically extended to local financial institutions with the aim of improving access to finance, and hence directly target domestic private actors in beneficiary countries. Syndicated loans and shares in CIV are the most-widely deployed tool to mobilise finance from other or multiple origins, reflecting how these mechanisms are structured to pull in varied sources of capital and investor profiles.

Some sectors are more appealing to domestic investors in LDCs. Blending in agriculture, forestry and fishing mostly relied on private capital mobilised from the recipient country, while receiving very little investment from the provider country. This is systematically observed over the entire six-year period. Domestic investors are also active in the education sector, where the presence of capital from high-income countries remains strong. The majority of finance mobilised in the communications sector, instead, stemmed from third OECD/high-income countries, in LDCs and beyond.

Many LDCs have national development banks or other domestic financial institutions that are set up to help fund national development plans and could potentially play a much greater role in crowding in private investors. By blending concessional resources with their own, more expensive sources of finance from capital markets, national DFIs can potentially reduce the cost of capital for projects. For further insights into this topic, see the Guest Piece in Section 2.4 by Maniram Singh Mahat (Town Development Fund).

While opportunities for leveraging domestic investors may be limited in nascent financial markets with fewer local investors and intermediaries, their involvement can foster local development and ownership, a grounding principle of development effectiveness. This also raises the broader question of whether ODA would be more effectively used in supporting the development of an improved business climate or the local private sector in LDCs rather than (or in addition to) being used to directly mobilise private investments. Certainly, while some barriers to an enabling environment for private sector investment can only be fixed through public intervention, demonstration effects from blended projects (especially when they are of national importance) could inform government-led policy reforms. Supporting both project financing and country-led reforms at the same time should be possible and could potentially create virtuous circles. This further underlines the need for co-ordination among blended finance and other interventions aimed at supporting long-term private sector development.

References

[10] Basile, I. and J. Dutra (forthcoming), OECD Blended Finance Funds and Facilities 2018 Survey results forthcoming.

[11] Benn, J., C. Sangaré and T. Hos (2017), “Amounts Mobilised from the Private Sector by Official Development Finance Interventions Guarantees, syndicated loans, shares in collective investment vehicles, direct investment in companies and credit lines”, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/8135abde-en.pdf?expires=1532438903&id=id&accname=ocid84004878&checksum=543F0A0796619DF343210C316FCD453A (accessed on 24 July 2018).

[7] Convergence (2019), Convergence Deals Database, https://www.convergence.finance/ (accessed on 1 July 2019).

[9] Convergence (2019), Leverage of concessional capital, Convergence, https://www.convergence.finance/knowledge/35t8IVft5uYMOGOaQ42qgS/view.

[12] OECD (2019), Development aid drops in 2018, especially to neediest countries, OECD, http://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-data/ODA-2018-detailed-summary.pdf.

[3] OECD (2018), Blended finance Definitions and concepts, OECD, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264288768-7-en.

[2] OECD (2018), Global Outlook on Financing for Sustainable Development 2019: Time to Face the Challenge, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264307995-en.

[8] OECD (2018), States of Fragility 2018, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264302075-en.

[6] OECD (n.d.), Statistics on amounts mobilised from the private sector by official development finance interventions as of 1st April 2019, http://www.oecd.org/development/stats/mobilisation.htm.

[5] UN (2018), Least Developed Countries (LDCs), https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/least-developed-country-category.html (accessed on 28 May 2019).

[4] UNCDF (2018), Blended Finance in the Least Developed Countries, New York, https://www.uncdf.org/bfldcs/home (accessed on 28 May 2019).

[1] UNCTAD (2018), World Investment Report 2018 - Investment and New Industrial Policies, http://www.unctad.org/diae (accessed on 13 June 2019).

Notes

← 1. Private investment flows include FDI, portfolio investment and long-term debt. FDI makes up the largest share of private investment flows.

← 2. The 2018 ODA release marks the adoption of the “grant-equivalent” methodology, which the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) agreed in 2014 would provide a more realistic comparison between grants and loans (OECD, 2019[12]).

← 3. Official development finance includes: 1) bilateral official development assistance (ODA); 2) grants and concessional and non-concessional development lending by multilateral financial institutions; and 3) other official flows for development purposes (including refinancing loans) which have too low a grant element to qualify as ODA.

← 4. More information about that survey and its original findings can be found in (Benn, Sangaré and Hos, 2017[11]).

← 5. The official providers who report private finance mobilised to the OECD are: African Development Bank, Asian Development Bank, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Caribbean Development Bank, Council of Europe Development Bank, Credit Guarantee and Investment Facility, Czech Republic, Denmark, Development Bank of Latin America, EU Institutions, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, Finland, France, Germany, Global Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Fund, IDB Invest, IFAD, Inter-American Development Bank, International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, International Development Association, International Finance Corporation, Ireland, Korea, Luxembourg, Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency, Netherlands, Nordic Development Fund, Norway, Portugal, Private Infrastructure Development Group, Slovak Republic, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, United States.

← 6. Convergence is the global network for blended finance. It generates blended finance data, intelligence, and deal flows to increase private sector investment in developing countries and sustainable development. Convergence works to make the SDGs investable through transaction and market-building activities.

← 7. Analysis of the 2012-2015 IFC data indicates that 4.6% or just under USD 460 million of the USD 9.89 billion in private finance mobilised by the IFC was in LDCs. For the period 2016-2017 the IFC reported USD 10.3 billion of private finance mobilised. Assuming the same percentage allocation to LDCs, that would mean approximately USD 480 million was mobilised in LDCs for 2016-2017. These amounts added to the total mobilised in LDCs would in fact indicate a continued increase in private finance mobilised in LDCs to over USD 2 billion in 2016. However, they would still indicate a decrease in 2017, at USD 1.94 billion mobilised. However, the estimates based on historical IFC amounts mobilised may not be accurate for the actual amounts mobilised in LDCs.

← 8. Besides the different time frames, the higher proportion (12% versus 6%) exhibited by Convergence with respect to the OECD data can be explained by a number of factors: 1) Convergence only tracks operations that include a concessional element (of public or philanthropic origin), which is often essential to mobilise private investors in markets perceived as more risky; 2) the amounts tracked by Convergence may cover LDCs either exclusively or in part, whereas the OECD methodology would only account for the part of finance destined to LDCs; and 3) the information is captured by Convergence at announcement of the deal closure and hence refers to expected investment targets, while the OECD requires annual reporting on the actual invested flows deployed.

← 9. More precisely, the most recent OECD data reveal that 40 LDCs had private finance mobilised during 2012-2015 compared to 39 LDCs during 2016-2017. Bhutan, Lesotho, South Sudan and Yemen had received private finance mobilised in 2012-2015 but not in 2016-2017. Equatorial Guinea, Vanuatu and Somalia received private finance mobilised in 2016-2017 but not in the previous time period. This means a total of 43 LDCs benefited from private finance mobilised for the whole six-year time period (2012-2017).

← 10. Last year’s report found that private finance mobilised was positively correlated to gross national income (GNI) per capita, perhaps because it is easier to mobilise private finance in contexts where more capital exists, or perhaps because a higher GNI per capita signals either larger market opportunities or a stronger enabling environment.

← 11. Bhutan, Central African Republic, Comoros, Eritrea, Kiribati, Lesotho, Tuvalu, and fragile contexts South Sudan and Yemen.

← 12. Analysis of annual data indicates that energy and banking and financial services are consistently amongst the top two sectors for private finance mobilised in LDCs (except in 2012 and 2016). In other developing countries energy and banking and financial services are the top two sectors for private finance mobilised for the years 2012, 2013, 2014 and 2017, and in the top three for 2015 and 2016.

← 13. Angola (where 10 providers reported private finance mobilised in 2012-2017), Bangladesh (13), Burkina Faso (10), Cambodia (23), Democratic Republic of the Congo (13), Ethiopia (15), Lao PDR (10), Mali (12), Mozambique (17), Myanmar (14), Nepal (10), Rwanda (12), Senegal (12), Tanzania (16), Uganda (17), Zambia (19).

← 14. Vanuatu (Australia), Somalia (United Kingdom), Gambia (Netherlands), Chad (France) and Solomon Islands (Korea).

← 15. Aid is tied if it is offered on the condition that it be used to procure goods or services from the provider country. Further information can be found here: http://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-standards/untied-aid.htm