This final chapter provides a short conclusion to the report – drawing on the latest data presented in Chapter 1 and the expert views from the field in Chapter 2. It summarises the emerging issues, including ideas and guiding principles for handling the risks and maximising the opportunities of blended finance, especially for the “missing middle”. Finally, it asks what’s next for UNCDF’s action agenda, and for the blended finance community more generally, using a series of questions to help shape the next steps.

Blended Finance in the Least Developed Countries 2019

3. Key questions and next steps for how blended finance can best support least developed countries

Abstract

3.1. Making blended finance work for LDCs

While turning the “billions into trillions” is essential to bridge SDG financing gaps, there is a need also to focus on the quality of resources mobilized, how they reach those being left behind and to what extent they may actually contribute to achieving the SDGs. Data analysed for this report show that of all private finance mobilised by official development finance interventions between 2012 and 2017, approximately USD 9.3 billion, or 6%, went to LDCs, whereas over 70% went to middle-income countries. Owing to data gaps, it remains unclear whether this represents a relative drop compared to the 7% of private finance mobilised for LDCs observed for 2012-2015. This nonetheless implies that little is changing when it comes to using blended finance to encourage private investment in the most vulnerable countries.

Coupled with the recent decline in ODA to LDCs, this further suggests that the financing for development architecture is not yet providing LDCs the support they need to achieve the SDGs, something that risks hardening exclusions between and within countries, rather than overcoming them. Some donors are taking steps to increase their engagement in LDCs, but the data suggest that many providers still tend to overlook such markets when it comes to blending. This in turn implies the need for further risk taking and experimentation at both the balance sheet and project level to get more private finance invested in those LDCs where blended finance is an appropriate solution.

As the 2018 report found (Box 3.1), the difficulty of blending finance in LDCs may reflect objective challenges in attracting private capital to riskier, smaller and less-tested markets – even when concessional resources are deployed to mitigate risks. Some providers may also shy away from such markets for several reasons: they may have a low appetite for risk given the need to preserve their triple-A credit ratings; they may lack awareness of investable projects; institutional incentives may push them to close deals, leading to a focus on “easier” markets or projects; or their mandates may favour commercial returns.

Nevertheless, the experts and practitioners whose voices are heard in Chapter 2 reveal that an increasing number and variety of players – impact investors, NGOs, think tanks, domestic financial intermediaries – are entering this space and are interested in ensuring that blended finance transactions are effective and efficient and can work in even the most challenging contexts to allow LDCs to achieve their development goals. While the support required will vary by project type and sector, a flexible and hands-on approach is necessary in blended finance transactions in LDCs; such transactions typically also require greater levels of concessional support than in other developing countries.

The many and varied examples given in Chapter 2 suggests that blended approaches can help mobilise much-needed additional resources to help LDCs bridge SDG financing gaps – and create demonstration effects that narrow the gap between actual and perceived risks of investing in these markets. But such approaches need to be considered and deployed carefully, and risks associated with blended finance approaches will need to be addressed. Even in those blended transactions supported by concessional finance, a higher risk tolerance is typically necessary when entering LDCs. In crisis-affected contexts, where ODA plays an essential role, blended approaches must be particularly transparent and accountable, in addition to doing no harm by, say, widening disparities. In LDCs there is an especially large gap in the ability of SMEs in the "missing middle" to access the capital they need to grow, as neither commercial banks nor micro-finance institutions tend to have the capacity or products that match their requirements (Box 1.2, in Chapter 1). A local presence, be it an investor or a fund manager, can help build local capacity and understand risks and opportunities attached to each investment. Technical assistance can be essential to generate investable opportunities, including as it relates to strengthening investees’ capacity in areas like ESG compliance and improved operational efficiency. Blended finance transactions need to demonstrate clear sustainable development additionality, and there is a need for further research and efforts to strengthen SDG impact measurement.

While blended approaches seek to increase overall financing for the SDGs, without an increase in the overall level of aid, using more ODA for blending may reduce its availability for development sectors not usually suitable for blending, such as helping to fund basic infrastructure or social services in LDCs. Given concerns about LDC governments not being fully involved in decisions about the allocation of concessional resources, or blended finance being a back door to tied aid, concessional finance providers and donors should ensure that blended transactions align with national priorities and respect national ownership. LDCs may also need support to put in place the right capacities and institutions to identify, analyse and structure blended operations. In light of indebtedness concerns, LDC governments should institute sound fiscal risk management frameworks that account for contingent liabilities arising from blended finance projects.

Monitoring and evaluation and knowledge-sharing are very important to improve the evidence base of blended finance impact in LDCs, and contribute to the formation of best practices. More broadly, blended finance solutions should be applied as part of a broader national SDG financing strategy that takes into account domestic and international, public and private sources of finance.

3.2. Principles and a roadmap to guide blended finance in the least developed countries

There are long-standing principles of development effectiveness related to the use of ODA. Where ODA is involved, blended transactions should meet those same standards. To improve the effectiveness and efficiency of blended operations, and to address some of the risks mentioned above, specific principles for using blended finance have emerged in recent years. For instance, as part of the Addis Ababa Action Agenda (AAAA) of the Third International Conference on Financing for Development, United Nations Member States agreed on a set of overarching principles for blended finance and public-private partnerships (PPPs) (UN, 2015[1]). In October 2017, the OECD Development Assistance Committee approved a set of blended finance principles for unlocking commercial finance for the SDGs (Section 3.3). Also in October 2017, a working group of DFIs proposed five principles, enhanced with detailed guidelines, on blended concessional finance for private-sector projects.1

As the 2018 report found, these sets of principles share many common elements that are of relevance to the use of ODA in blended transactions in LDCs. Two critical principles it highlighted are:

Sustainable development additionality, meaning that the intervention has direct development impact, is aligned with the SDGs, and has the goal of leaving no one behind.

Financial additionality, meaning that the project will not be funded by commercial sources alone without concessional support. Ensuring the minimum amount of concessionality is critical to avoid oversubsidising the private sector while also not crowding out private investors or unduly distorting local markets. Still, determining the amount and structure of concessionality is difficult, especially in LDCs.

The 2018 report also underscored that providers of concessional finance should ensure that blended transactions:

support alignment with, and ownership of, the national development agenda

comply with high standards of transparency and accountability

promote the fair allocation of risks and rewards

apply rigorous environmental, social and governance (ESG) standards; promote local participation; do not widen disparities or inequalities – gender, income or regional – within a country; and ensure a focus on the empowerment of women.

3.3. How do the OECD Principles and Tri Hita Karana Roadmap apply to the least developed countries?

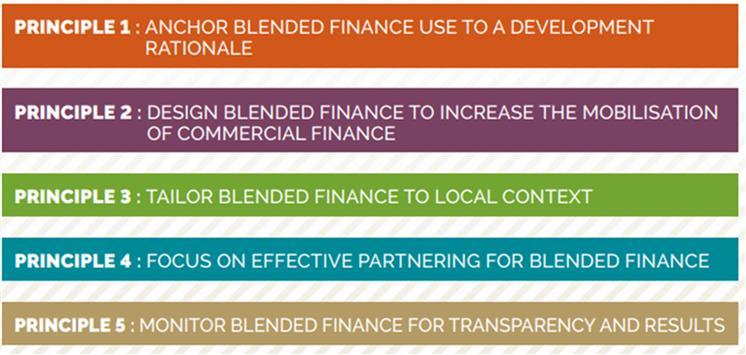

The OECD principles on blended finance provide a policy framework to ensure the sustainability of blended finance as one approach in the donors’ toolbox for development co-operation (Figure 3.1). The principles aim to ensure that blended finance is deployed in the most effective way to address the financing needs for sustainable development as set out in the AAAA, by mobilising additional commercial capital and enhancing impact. The principles have also been referred to in the G7 commitment on innovative financing for development agreed in Canada (G7, 2018[2]).

Figure 3.1. The OECD Development Assistance Committee Blended Finance Principles

Source: (OECD, 2018[3]) Making Blended Finance Work for the Sustainable Development Goals, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264288768-en

The OECD is currently working on more detailed guidance for donor governments to support the implementation of these principles. The guidance will provide best practice examples, support the development of effective policies and facilitate accountability, and will have important applications in LDCs, given that bilateral donors are increasingly prominent mobilisers in these countries (Section 1.9). More specifically, the policy guidance will work towards ensuring blended finance is designed to deliver development additionality where it is needed most, that it is tailored to specific contexts and helps build local financial markets which are often nascent in LDCs. In particular, Principle 4, which advocates a more targeted, balanced and sustainable allocation of risks between partners, will be important for blending in LDCs where actual or perceived risks are often higher (OECD, 2018[4]).

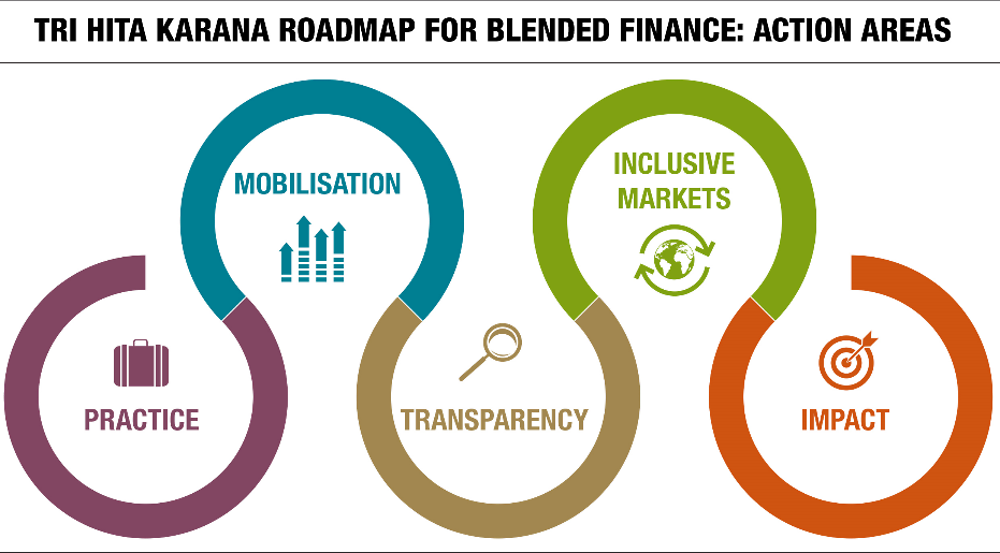

In recognition that blended finance is a multi-stakeholder concept, the OECD is also undertaking broader co-ordination work with others in the blended finance field. The Tri Hita Karana Roadmap (Figure 3.2) was launched on the side-lines of the IMF/World Bank Meeting in Bali, Indonesia in October 2018 (OECD, 2018[5]). The roadmap establishes a shared value system amongst a slew of international actors, including multilateral development banks; development finance institutions; governments, such as Indonesia, Canada and Sweden; private sector actors; civil society organisations; and think tanks. Guided by the roadmap, international actors are working to deliver on five action areas: practice, mobilisation, transparency, inclusive markets and impact.

Figure 3.2. The Tri Hita Karana Roadmap for blended finance: Action areas and working groups

Source: (OECD, 2018[5]), Tri Hita Karana Roadmap for Blended Finance, http://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-topics/tri-hita-karana-roadmap-for-blended-finance.htm

Heightened transparency will help better inform investors and grow blending opportunities in LDCs. Promoting the measuring and reporting of impact will help ensure that blended operations implemented in LDCs achieve their expected development results. The Tri Hita Karana working groups aim to ensure the promotion of good practice and common frameworks to ensure the potential of blended finance can be delivered in LDCs and beyond. The guidance developed through the OECD principles will feed into the working groups and vice versa.

3.4. What’s next for UNCDF’s action agenda on blended finance for least developed countries?

Since the launch of the 2018 report in November (Box 3.1), UNCDF has been working to build a coalition of partners – LDC governments; DFIs and multilateral development banks (MDBs), private investors, multilateral and bilateral development agencies, philanthropic foundations, civil society, and think tanks – to take forward the action agenda proposed in that report.

This has included convening a wide range of public and private stakeholders for launch events in London, Paris, Dakar, Ottawa, Bangkok, and Kampala, as well as convening or participating in widely-attended webinars and expert group meetings, including during the 2019 Financing for Development Forum. UNCDF has used these events to: share the findings and messages of the 2018 report; bring LDC governments, providers of concessional finance, investors, and civil society to the table; provide an open platform for sharing knowledge and experiences; and push for blended finance to work better for LDCs.

Anecdotally, partners have informed UNCDF that the 2018 report has helped bring to discussions on blended finance a focus on LDCs and leaving no one behind. Some providers of concessional finance have stated that they are using the findings of the 2018 report to develop or refine their investment strategies.

Box 3.1. Messages and action agenda from UNCDF’s 2018 blended finance report

The 2018 report “Blended Finance in the Least Developed Countries” (UNCDF, 2018[6]) examined the opportunities and challenges for deploying blended strategies in LDCs, and how to pursue them effectively. It noted that blended finance approaches can help mobilise much-needed additional capital for LDCs. In addition, blended finance in LDCs can create demonstration effects that support commercial replication over time, inform government-led policy improvements and potentially support the development of local markets.

Still, blended projects are not without their limitations and risks. They also need to be considered carefully and should be applied as part of a broader SDG financing strategy. Ultimately, project and country characteristics, macroeconomic conditions and national policy priorities should determine which financing model—public, private or blended—is best suited for which SDG investment.

UNCDF proposed a five-point action agenda to improve the practice of blended finance and help ensure that its application can support LDCs to achieve the SDGs:

Encourage risk taking and experimentation, as appropriate: Providers of concessional finance should engage with their boards, donors and LDC governments to find innovative ways to take more risks and experiment with new solutions, as part of broader efforts to get more private resources flowing to LDCs. Where blended approaches are the right ones, this could mean establishing and/ or sufficiently resourcing existing dedicated funds, facilities, entities or special purpose vehicles that will support blended projects in LDCs throughout their lifecycle.

Bring LDCs to the decision-making table: Global policymaking discussions on blended finance should purposefully engage LDCs and other developing countries as active participants. It would be important to convene these discussions in universal forums, such as the Financing for Development and Development Cooperation Forums held at the United Nations. To strengthen national capacities in LDCs, providers of concessional finance and donors should support national and local government officials and national development banks with targeted capacity-building and training.

Deploy blended strategies to support sustainable outcomes: It is essential that blended finance transactions have SDG impact, with the goal of leaving no one behind. Providers and other development partners in LDCs should, where appropriate, actively seek out suitable domestic investors and support blended transactions in local currencies. To respect ownership, providers should proactively engage at a strategic level with LDC governments so that they can determine which financing model is best suited for a given investment.

Improve impact measurement and transparency: Strengthening SDG impact measurement means that providers should ensure that ex-ante SDG impact assessments and ex-post evaluations are undertaken and made publicly available. To improve transparency, it is important that concessional providers also publicise such information as how much ODA is going into blended transactions.

Increase knowledge-sharing and evidence to inform blended finance best practice: Providers should work with all stakeholders to maximise the sharing and transfer of knowledge on blended finance in LDCs. All stakeholders should also continue generating additional evidence as to how blended finance can work in LDCs and riskier markets.

Source: (UNCDF, 2018[6]), Blended Finance in the Least Developed Countries

Internally, the 2018 report has helped to influence how UNCDF approaches its own growing portfolio of blended finance deals to support projects in the missing middle. After the launch of the report – and in line with its recommendation that there be more focus on taking blended finance to the LDCs where appropriate – UNCDF also announced a partnership with Bamboo Capital Partners. This partnership will seek to establish a blended finance impact investing vehicle to attract concessional and commercial growth finance to a pipeline of SMEs, financial service providers and local infrastructure projects supported through UNCDF’s programmes in LDCs.

More broadly, and in line with the findings of the 2018 report, the outcome document of the 2019 Financing for Development Forum (UN, 2019[7]) calls on providers of blended finance to engage strategically with host countries at the planning, design and implementation phases to ensure that priorities in their project portfolios align with national priorities. The same outcome document also requests the Inter-agency Task Force on Financing for Development, as part of its 2020 report, to assess the risks, opportunities and best practices in relation to different financing instruments, including blended finance, and how they can be best tailored to specific country contexts, including LDCs – something to which this edition of the report will be contributing.

Going forward, UNCDF will continue its outreach. This edition of the report adds to the now-growing evidence base of how best to make blended finance work for LDCs – and UNCDF is committed to sharing its findings widely and building momentum to ensure that more resources go to where they are most needed.

3.5. Questions to shape the next steps

Blended finance in LDCs is an evolving concept. This report therefore concludes with several suggested areas for further research based on the guest pieces and the issues and limitations revealed in the data analysis.

The data presented in Figure 1.2 and in Box 1.3, along with the findings of the 2018 report, suggest that blended finance transactions in LDCs mobilise smaller amounts of private finance than in middle-income countries. Given the need to mobilise larger amounts of finance to meet the SDGs, MDBs and DFIs are looking to make optimal use of their balance sheets and strengthen the catalytic role of their interventions. A question some stakeholders have raised is whether setting hard mobilisation targets is the best way to achieve this goal. While higher leverage ratios can play an important role in bridging SDG financing gaps, setting hard mobilisation targets for providers of concessional finance raises concerns. Careful analysis is necessary to consider the impact of mobilisation targets on development finance envelopes and allocations for LDCs and other vulnerable countries. More broadly, if blended finance continues to become an increasingly important modality of development co-operation, as this report suggests is the case, then development partners will need to ensure that this does not come at the expense of support for LDCs and other vulnerable countries – those where blending has been more challenging. Moreover, hard ratios can lead to a focus on meeting quantitative targets, as opposed to focusing on quality or the impact on sustainable development. It may be that there is a need to accept that the mobilisation agenda in LDCs will be different – but that those blended finance deals, where they are appropriate, are pursued because of their sustainable development additionality.

The data in Figure 1.19 show that the amount of private finance mobilised by investors in the beneficiary LDCs themselves has declined over the six-year period. This raises the question of whether blended finance transactions should focus on attracting domestic or foreign investors. Certainly, there can be instances where either domestic or foreign private capital might provide the best financing option for a particular deal. While FDI can also bring benefits in the form of know-how, technology and expertise to LDCs, proactively focusing on domestic investors can have positive side effects on local market development and ownership.

These issues could be the subject of further research, guided by the specific questions listed in Box 3.2.

Box 3.2. Suggestions for further research on blended finance in LDCs

Is external private finance crowding out domestic investors, and does the decrease in private finance mobilised from domestic investors have any links with tied aid – both questions raised by Figure 1.19?

How do blended finance approaches fit into integrated national financing frameworks, and how do these relate to questions of ownership?

How much blending is taking place thanks to concessional providers from the South, something not captured in the OECD data?

What is the role of philanthropy in blended finance transactions in LDCs?

Why is there a weak but positive correlation between ODA received and private finance mobilised (see Section 1.6)?

Does the difference in focus sectors between domestic and foreign investors reflect domestic versus foreign priorities?

What is the impact of increased blending and mobilisation ratios on development financing envelopes overall, and for LDCs in particular?

References

[8] DFI Working Group on Blended and Concessional Finance (2017), DFI Working Group on Blended Concessional Finance for Private Sector Projects: Summary Report, https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/30635fde-1c38-42af-97b9-2304e962fc85/DFI+Blended+Concessional+Finance+for+Private+Sector+Operations_Summary+R....pdf?MOD=AJPERES (accessed on 1 July 2019).

[2] G7 (2018), Charlevoix commitment on innovative financing for development, https://international.gc.ca/world-monde/international_relations-relations_internationales/g7/documents/2018-06-09-innovative_financing-financement_novateur.aspx?lang=eng (accessed on 28 May 2019).

[3] OECD (2018), Making Blended Finance Work for the Sustainable Development Goals, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264288768-en.

[4] OECD (2018), Principle 4 - OECD, http://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/blended-finance-principles/principle-4/ (accessed on 28 May 2019).

[5] OECD (2018), Tri Hita Karana Roadmap for Blended Finance and Achieving The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), OECD, Paris, https://g7.gc.ca/en/g7-presidency/themes/investing-growth-works-everyone/g7-ministerial-meeting/co- (accessed on 31 October 2018).

[7] UN (2019), E/FFDF/2019/L.1 - Economic and Social Council forum on financing for development follow-up, https://undocs.org/E/FFDF/2019/L.1 (accessed on 24 June 2019).

[1] UN (2015), The Addis Ababa Action Agenda, https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/2051AAAA_Outcome.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2018).

[6] UNCDF (2018), Blended Finance in the Least Developed Countries, New York, https://www.uncdf.org/bfldcs/home (accessed on 28 May 2019).

Note

← 1. The principles can be found in the working group’s Summary Report: (DFI Working Group on Blended and Concessional Finance, 2017[8]) www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/30635fde-1c38-42af-97b9-2304e962fc85/DFI+Blended+Concessional+Finance+for+Private+Sector+Operations_Summary+R....pdf?MOD=AJPERES