This chapter examines the capacities of the centre of government (CoG) to monitor and evaluate the performance of key policy priorities and programmes and to use this information to improve policy making and service delivery. It provides an in-depth assessment of the institutional framework for monitoring and evaluation (M&E). The chapter also analyses the quality of M&E and the use of M&E results.

Centre of Government Review of Brazil

4. Monitoring and evaluating priorities from the centre in Brazil

Abstract

Introduction

This chapter will focus on the CoG’s capacities to monitor and evaluate the performance of key policy priorities and programmes by collecting and using information and evidence in the policy-making process. To this end, the chapter provides an assessment and recommendations on:

The institutional framework for monitoring and evaluation (M&E) in Brazil, through an analysis of the CoG’s practice, policy frameworks and guidelines, and the main actors involved, with a focus on strengthening the M&E of cross-cutting programmes.

The quality of M&E, including quality assurance and control mechanisms, the definition of key national indicators, guidelines and practices to develop skills and capacities on M&E, and stakeholders’ engagement mechanisms, with a focus on spreading and systematically using mechanisms.

The use of M&E results, in particular the CoG’s capacity to strategically integrate and manage performance information, with a focus on promoting access to high-quality data.

A robust M&E system is essential to achieve short-, mid- and long-term objectives, as mentioned in Chapter 2. When M&E reports information is fed back to policy makers and decision-makers, it can provide the necessary data and information to guide strategic planning, design and implement programmes and projects, and allocate and re-allocate resources in better ways (OECD, 2021[1]). Additionally, real-time monitoring provides a continuous stream of relevant and current data from which administrators can immediately identify serious problems and adjust policies in mid-course. Sound M&E can help identify barriers to policy implementation and ways to address them (OECD, 2019[2]). Moreover, M&E allows actors to learn from each other’s experiences by providing tools to follow the development of others’ activities. In addition to policy learning (i.e. increased understanding that occurs when policy makers compare one set of policy problems to others), M&E can also foster transparency and accountability by providing performance information to citizens on progress in achieving government objectives (Vági and Rimkute, 2018[3]). Though interconnected, M&E are distinct practices (as outlined in Table 4.1) and this is why it is important to distinguish between them (OECD, 2020[4]).

In Brazil, M&E definitions can be found in the Guia Prático de Avaliação Ex Post and the Guia Prático de Análise Ex Ante. Evaluation is also defined in a bill for the new Public Finance Law (currently Law No. 4.320/1964), which has been on the agenda of the CoG. Adopting a comprehensive definition of M&E in law would help define their objectives and actions to be taken to achieve them.

Table 4.1. Comparing policy monitoring and policy evaluation

|

Policy monitoring |

Policy evaluation |

|---|---|

|

Ongoing (leading to operational decision-making) |

Episodic (leading to strategic decision-making) |

|

Monitoring systems are generally suitable for the broad issues/ questions that were anticipated in the policy design |

Issue-specific |

|

Measures are developed and data are usually gathered through routinised processes |

Measures are usually customised for each policy evaluation |

|

Attribution is generally assumed |

Attribution of observed outcomes is usually a key question |

|

Because it is ongoing, resources are usually a part of the programme or organisational infrastructure |

Targeted resources are needed for each policy evaluation |

|

The use of the information can evolve over time to reflect changing information needs and priorities |

The intended purposes of a policy evaluation are usually negotiated upfront |

Source: Adapted from McDavid, J. and L. Hawthorn (2006[5]), Program Evaluation and Performance Measurement: An Introduction to Practice, Sage Publications, Inc., in OECD (2019[2]), Open Government in Biscay, OECD Public Governance Reviews, https://doi.org/10.1787/e4e1a40c-en.

As described in Chapter 1, monitoring is a key CoG function in Brazil and OECD countries. OECD data show that, in half of the surveyed countries (55%), CoGs are responsible for monitoring the implementation of government policy (OECD, 2018[6]). The OECD survey on policy evaluation (2018[7]) also finds that the CoG plays a crucial role in embedding a whole-of-government approach to policy evaluation (OECD, 2020[4]). For example, in 16 OECD countries (18 countries in total), the CoG’s mandate includes the definition and update of the evaluation, while in 15 countries, it includes providing incentives for carrying out policy evaluation. The CoG serves the executive and plays a crucial role in ensuring that the government makes evidence-informed decisions, which a robust M&E system can help with. M&E is especially key for effective strategic planning, prioritisation and sequencing purposes for the CoG (Chapter 2). The success of any government programme partially depends on the ability of the CoG to oversee the quality of the policy‑making process, from developing a policy to monitoring and evaluating its outcome (OECD, 2018[6]).

According to respondents to the OECD questionnaire, in Brazil, the main objectives of monitoring are: i) improving transparency; ii) verifying that policies are achieving the expected objectives and are in line with the needs and demands of the Brazilian people; iii) promoting organisational learning; and iv) enhancing the use of evaluation among federal units and agencies in order to provide better public services to society, with more efficiency and better compliance as well as best resource allocation.

As regards policy evaluation, one of the main objectives for conducting them is to assess public policies financed by direct spending or government subsidies, to measure the benefit generated for the citizen and to collect input to redirect or improve the design of public policies (Law No. 13.971/2019). In Brazil, policy evaluation is a principle of public administration (Article 37 of the constitutional amendment).

The chapter analyses the Brazilian institutional setup, identifies key challenges and suggests ways to improve the overall quality of the M&E mechanisms at the CoG.

Building a sound institutional framework for monitoring and evaluating policy priorities

A sound M&E system means that: both practices, monitoring and evaluation, are part and parcel of the policy cycle; they are carried out systematically and rigorously; and decision-makers use their results (Lázaro, 2015[8]). An M&E system entails:

A solid institutional framework, based on the right legal, policy and organisational measures to support the performance of public policies.

Mechanisms to promote the use of evidence and policy M&E by investing in public sector skills, policy-making processes and supporting stakeholder engagement.

Mechanisms to promote the quality of policy M&E, for instance through developing guidelines, investing in capacity building and ex post review and control mechanisms (OECD, 2019[2]).

The Pluriannual Plan: A well-developed reporting system not used for real-time monitoring and decision-making

The Brazilian monitoring system has its main institutional anchorage in the Pluriannual Plan (Plano Plurianual da União, PPA), which establishes the mechanisms and practices for the majority of monitoring actions in Brazil. The PPA is a government planning instrument that defines the guidelines, objectives and goals of the federal public administration. As explained in Chapters 2 and 3, the PPA contains macroeconomic forecasts and fiscal objectives for a four-year period, which the government prepares within its first year of taking office and submits to Congress for approval. The four-year period of the plan means that the final year extends into the first year of the next governmental term, for the purpose of providing continuity across electoral cycles. The PPA 2020-2023 contains 19 guidelines, 15 themes, 70 programmes, objectives, targets and indicators, and 328 intermediate results.

The monitoring process of the PPA 2020-2023 is co‑ordinated by the Ministry of Economy, in particular the Secretariat for Evaluation, Planning, Energy and Lottery (Secretaria de Avaliacao, Planejamento, Energia e Loteria, SECAP), which provides methodology, guidance and technical support to achieve the objectives and targets stated in the plan. The plan contains the following type of programmes (Ministerio da Economia, 2020[9]):

Finalistic Programmes are the main programmes to be monitored in the PPA. They portray the government’s agenda, organised by selected public policies that guide governmental action.

Management Programmes, used by all ministries, reflect the operational expenses of the agencies, in particular personnel expenses and administrative operational costs.

One Multi-Sectoral Agenda, to promote cross-government co-ordination. In the case of the PPA 2020-2023, the one transversal agenda item is early childhood, which is co‑ordinated through a specific working group.

The bodies responsible for the implementation of a programme (line ministries, agencies) must report twice per year on the implementation of the goals, intermediate results and Priority Pluriannual Investments associated with their respective programmes. In the case of multi-sectoral programmes, the responsible agency shall collect information on the objectives and goals of the other agencies. The monitoring report on the fiscal programmes, their attributes and the Priority Multiannual Investments are expected to be consolidated on an annual basis, submitted to the National Congress and made available on the Ministry of Economy’s website (www.economia.gov.br). Therefore, the government of Brazil has established a structured and permanent process for monitoring the PPA, centred on the priority objectives of the federal government and its ministries (Ministerio da Economia, 2020[9]).

The definition of which intermediate results will be subject to reporting is the result of joint work by the line ministries and SECAP. According to Law No. 13.971/2019 (Article 22), the Institutional Strategic Plan (PEI) should be aligned with the PPA and national, sectoral and regional plans. The line ministry sends SECAP an indication of which attributes of the PEI – i.e. the institutional planning instrument that sets out a strategic vision and establishes priorities, objectives, goals and resource requirements of public sector bodies and agencies – present intermediate results for reaching the PPA goal and, together with SECAP, selects among them.

The agreed-upon results must be compatible with the ministry’s operational capacity and budgetary and financial availability. There are three reporting events each year, whose deadlines, objectives and processes are outlined in Table 4.2.

With the aim of guiding the PPA monitoring process, the Monitoring Plan (Plano de Monitoramento) works as a guide for SECAP to address the main issues with line ministries. Its purpose is to record the main intermediate results that contribute to the achievement of the target in each programme, the main restrictions that need to be overcome and the measures needed to achieve each result and how SECAP will contribute to this process in co‑ordination with ministries.

The explicit relationship between the Federal Development Strategy 2020-2031 (Estratégia Federal de Desenvolvimento 2020-2031, EFD 2020-2031) and the PPA takes place through the five axes, which are common to both plans. The results of the PPA programmes contribute to the achievement of the EFD’s objectives but there is no systematic relationship between them. Thus, there is no monitoring of the evolution of the EFD’s objectives based on the M&E of the PPA’s programmes. The strategic dimension reflects the government agenda that the head of the executive branch, through their ministers, intends to implement. These are the priorities defined by the government summit and represent a translation of the commitments of the president-elect for the country. In the PPA 2020-2023, the strategic dimension was unfolded in two categories: guidelines and themes. From a conceptual point of view, the guidelines represent the demands of the population taken over by the elected government and guide the construction of the PPA programmes. In turn, the themes, related to the new institutional structure of the federal government, correspond to the main sectoral areas to be mobilised to achieve the objectives included in the guidelines. In the PPA 2020-2023, the guidelines and themes are broken down into programmes, which have objectives and goals. It should be noted that the PPA 2020-2023 methodology does not provide the definition of goals and indicators for the guidelines and themes. This is because the guidelines express trajectories to be pursued, while themes express large areas, which constitute broad sectoral aggregations.

Table 4.2. Reporting events

|

Deadline |

Objective |

Process |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Definition of the intermediate results |

Within 30 days after the publication of the 1st Decree of Budgetary and Financial Programming of the year. |

|

After the bodies in charge of PPA’s Finalistic Programmes have made compatible the PEI and the PPA, they will send information related to the annex of the Decree No. 10.321 of 15 April 2020 to SECAP, with the list of the main intermediate results. From this list and with the knowledge of the budget and financial availability of the agency, there will be a meeting to agree on the results and their attributes between SECAP and the sectoral body. The product of this meeting will be the Monitoring Plan. Once the plan is finalised, the Integrated Planning and Budgeting System (SIOP) will be opened to the organ for completion/actualisation of intermediate results and their attributes. |

|

Progress tracking |

6 months after the first event |

|

Monitoring meeting between the agency and SECAP. |

|

Progress recording |

60 days after the end of the financial year |

Record the progress of the indicators and targets of the programme as well as the intermediate results and achievement of the programme objective. This information will be consolidated into the monitoring report to be sent to National Congress on an annual basis. |

Monitoring meeting between the agency and SECAP and the agency fills out SIOP with the results obtained during the year. |

Source: Author’s own elaboration based on Ministerio da Economia (2020[9]), Manual Técnico do PPA 2020-2023.

The PPA represents one of Brazil’s latest attempts at linking planning and budgeting by implementing medium- and long-term government planning, co‑ordinating government actions, and setting guidelines, objectives and goals for the public administration to guide the allocation of public resources. Regarding priority multiyear investments, the PPA is the main source of information for the CoG, making it possible to track the progress of all 30 priority investments. The PPA is being improved with tools to make it more useful for decision-making, for example, according to the Constitutional Amendment No. 109 of 2021, Article 165 of the federal constitution now states that the PPA, Budget Guidelines Law (Lei de Diretrizes Orçamentárias, LDO) and Annual Budget Law (Lei Orçamentária Annual, LOA) shall observe, when appropriate, the results of the M&E of public policies. Additionally, PPA monitoring bulletins are sent to ministries (executive secretaries) and contain an analysis of the main monitoring results, seeking to encourage reflection on the areas to adopt measures aimed at achieving goals and improving public policies, for example:

reallocation of budget resources between policies

relocation of staff

adjustments to the organisational structure

change in the institutional arrangement of public policy (design and legal framework)

ways to improve implementation

review of the plan.

Nevertheless, in practice, the PPA works as a compliance and reporting tool and does not allow for the discussion of performance and/or how to overcome implementation barriers. As will be analysed below, there is no clear link between the PPA and the Civil Cabinet of the Presidency’s (Casa Civil) monitoring of policy priorities. While the PPA has proven to be a useful tool for tracking public expenditure and informing on the achievement of programmes, further work can be done to link programme monitoring with outcome-oriented decision-making at the CoG.

Multiple actors with responsibility for monitoring and no clear alignment between them

In parallel with the monitoring system linked to the PPA, Casa Civil leads in the monitoring of presidential priorities. It has two special bodies with responsibilities for monitoring policy priorities:

The Undersecretariat for Articulation and Monitoring (Subchefia de Articulação e Monitoramento, SAM) monitors the government’s programmes and actions considered a priority by the president of the republic.

The Undersecretariat for Analysis and Monitoring of Government Policies (Subchefia de Análise e Acompanhamento de Políticas Governamentais, SAG) selects public policies to carry out ex ante and ex post analysis with the responsible ministries in order to review and update them.

Casa Civil’s instrument for the monitoring of projects is called Governa. The Governa system is software developed by Casa Civil with the objective to digitalise project management at the federal level. It mainly works as an internal management tool, though some users outside Casa Civil have access to some of the functionalities of the system. Within Governa, line ministries need to provide data on different projects under implementation, which includes all priority projects of the federal government and all PPA projects. Senior managers from Casa Civil validate this information. Every three months, ministers receive feedback regarding the advancement of every priority project and discussions take place. This system was affected by the COVID-19 pandemic so Governa is being adapted as a result. This was not surprising as the president’s portfolio needs to be constantly revised, especially after a pandemic.

Governa is a management information system that integrates and displays different federal projects (including PPA) on a single platform. However, the system is not linked with any performance framework and impact information that supports prioritisation at the CoG and, therefore, does not provide the basis for a structured monitoring and performance dialogue around cross-cutting policy priorities. In addition, as discussed in the previous chapters, the policy priorities defined by the presidency and supported by SAM and SAG are in several cases not translated into the PPA. This is explained, to some extent, by the nature and design of the PPA and by the budget rigidity explained in the previous chapters: the incoming government does not have the capacity to align the planning and budgetary system to their own priorities, resulting in the creation of new planning and monitoring structures. Another explanation can be found in the structure of the PPA. While it is a useful monitoring tool for tracking expenditure and some intermediate results can be shared by multiple ministries, for instance in the case of the Oceans, Coastal Zone and Antarctica project (Oceanos, Zona Costeira e Antártica) and also in the Prevention and Control of Deforestation and Fires in Biomes project (Prevenção e Controle do Desmatamento e dos Incêndios nos Biomas), the plan mainly focuses on sectoral initiatives. These intermediate results represent an interesting example of integrated policy goals and common reporting but they do not necessarily provide the framework for active collaboration and a performance dialogue among different government agencies on a very limited set of cross-cutting policy priorities to be steered or managed by the CoG.

The complexity of the planning and prioritisation system has led to overlapping monitoring units

As explained in Chapter 2 on planning, Brazil has a long-standing planning culture. Nevertheless, as Chapter 2 also underscores, this has also created some challenges related to the multiplication of planning and monitoring structures in government. There was a general consensus among stakeholders on the lack of clarity of who is in charge of monitoring policy priorities: for some SAM in Casa Civil, others mentioned SAG while others made reference to the Ministry of Economy, in particular SECAP and the Delivery Unit, which was created to monitor the priorities of the Ministry of Economy and ultimately the priorities related to the management of the pandemic (described in Chapter 2).

This overlap between Casa Civil and the Ministry of Economy’s functions occurs in other countries too. In these circumstances, line ministries usually tend to focus more on the Ministry of Economy’s process for economic reasons. As the Ministry of Economy – or similar – usually manages finances, line ministries tend to focus their efforts on aligning their actions to their planning and requests. Such an overlap generates a multiplication of reporting systems, causing efficiency loss and fragmentation. As mentioned in Chapter 1, co‑ordination is key for a well-functioning Brazilian CoG due to its high institutional fragmentation which can lead in some cases to mandate overlaps or duplications. The Brazilian CoG could consider refining co‑ordination mechanisms of monitoring systems within the CoG as well as between the CoG and external actors to avoid overlaps and waste of resources. More specifically, they might consider establishing greater clarity in the definition of the roles and tasks that Casa Civil and the Ministry of Economy have in monitoring, as mentioned in Chapter 2. Additionally, Brazil can consider co‑ordination of cross-cutting priorities. The United States (US) performance framework (led by the Office of Management and Budget within the Executive Office of the President) includes, among its Cross-Agency Priority (CAP) Goals, “mission-support” goals which represent a good example of the co-ordination of cross-cutting priorities aimed at improving agencies performance and promoting active collaboration among multiple agencies (Box 4.1).

Box 4.1. United States: Mission-support goals under Performance.gov

Performance.gov is a window into federal agencies’ efforts to deliver a smarter, leaner and more effective government. This site fulfils the statutory requirements for an online centralised performance reporting portal required by the Government Performance and Results Act (GPRA) Modernization Act of 2010. The site provides the public, agencies, members of Congress and the media a view into the progress underway to cut waste, streamline government and improve performance.

Performance.gov communicates the goals and objectives the federal government is working to accomplish, how it seeks to accomplish those goals and why these efforts are important. All cabinet departments and other major agencies have pages on Performance.gov. Each agency’s page provides an overview of the agency, its mission, priority goals to be achieved, the public officials and civil servants responsible for their implementation and links to its strategic and performance plans and reports.

The federal government sets both priority goals – cross-agency and within agencies – that are near-term, implementation-focused priorities of leadership as well as strategic objectives that are comprehensive of agencies’ missions.

Long-term in nature, Cross-Agency Priority (CAP) Goals are a tool used by leadership to accelerate progress on a limited number of presidential priority areas where implementation requires active collaboration among multiple agencies. CAP Goals drive cross-government collaboration to tackle government-wide management challenges affecting most agencies. As a subset of presidential priorities, these goals are used to implement the president’s Management Agenda and are complemented by other cross-agency co‑ordination and goal-setting efforts. CAP Goals are required to be set every four years but can address goals requiring longer timeframes. Performance targets will be reviewed and considered for updates at least annually with the President’s Budget. When CAP Goals have achieved a level of maturity and implementation that enables those teams to demonstrate and scale the impact and institutionalise these reforms, it becomes appropriate to refocus their activities from planning toward demonstrating results. As such, these goals will continue to be tracked on Performance.gov but reporting will shift from detailed milestones and action planning to report on implementation outcomes. The re-categorisation of these goals will be noted on each CAP goal page.

CAP Goals include outcome-oriented goals that cover a limited number of cross-cutting policy areas as well as “mission-support” goals addressing areas such as those related to improving agency performance. Previous mission-support goals included:

Effectiveness: Deliver smarter, better, faster service to citizens (customer service; smarter information technology [IT] delivery).

Efficiency: Maximise the value of federal spending (category management; shared services; benchmark and improve mission-support operations).

Economic growth: Support innovation, economic growth, and job creation (open data; lab-to-market).

People and culture: Deploy a world-class workforce and create a culture of excellence.

Source: US Government (n.d.[10]), Performance.gov, https://www.performance.gov (accessed on 12 May 2022).

The creation of the Public Policy Monitoring and Evaluation Council (CMAP) represents a step forward in the creation of an evaluation system

In the area of policy evaluation, Brazil’s evaluation system is the result of more than 30 years of governance reforms. They were established in Brazil in the 1990s and the adoption of these procedures was embedded in the 1988 Constitution’s provisions (Articles 165, 74, 37), which establish that the executive, legislative and judiciary’s internal control systems must aim “to evaluate the fulfilment of the goals foreseen in the multiannual plan, the implementation of government programmes and Union budgets”. The internal control system is also responsible for conducting evaluations of government programmes (Article 88). According to the government of Brazil, the main challenges faced in promoting an evaluation culture are:

the limited availability of data related to some public policies

the general confusion between M&Es

the underdeveloped culture of evaluation inside line ministries

the misalignment of the CoG and line ministries regarding the evaluation process

the limited availability of human resources

the insufficient training in policy evaluation tools.

To tackle these challenges, Brazil created in 2019 (by Decree No. 9.834) the Public Policy Monitoring and Evaluation Council (CMAP), a governing body of policy evaluation responsible for evaluating public policies financed by direct expenditures and government subsidies (selected annually from the PPA Finalistic Programmes). CMAP also monitors the recommendations resulting from these evaluations and is made up of the executive secretaries of the Ministry of Economy, which co‑ordinates it, Casa Civil and the Office of Comptroller General. As CMAP involves key central government entities, its establishment is a step forward in systematising M&E across government. Until the establishment of CMAP, a single entity with the sole responsibility for evaluating cross-cutting goals did not exist but, there were separate bodies responsible for evaluating the PPA, such as the Planning and Investment Secretariat of the former Ministry of Planning and the Federal Budget Secretariat. Box 4.2 explains in detail how CMAP functions.

On top of the newly created CMAP, the main actors responsible for evaluation are:

The Special Secretariat for Treasury and Budget (SETO) within the Ministry of Economy, responsible for, among other competencies, the evaluation of the socio-economic impacts of federal government policies and programmes and the preparation of specific studies for the formulation of policies.

The Secretariat for Evaluation, Planning, Energy and Lottery (SECAP) of the Ministry of Economy, responsible for supervising the evaluation process carried out by members or supporters of CMAP, or externally.

The General Secretariat (SG) is responsible for acting in the formulation of proposals and the definition, evaluation and supervision of the actions of the state’s modernisation programmes.

The Office of the Comptroller General (Controladoria General da União, CGU), through its Federal Secretariat for Internal Control, the central body of the Federal Internal Audit System in the executive branch of the federal government. The CGU performs assessment and consulting services focused on public policies and aimed at supporting the evaluation of the achievement of the goals established in the Pluriannual Plan (PPA), the execution of government programmes and the office’s budget, among other objectives.

The National School of Public Administration (ENAP), the Institute of Applied Economic Research (IPEA) and the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) are bodies that support, within the scope of their competencies, the development of evaluation and research activities of CMAS and CMAG.

Box 4.2. The functioning of CMAP

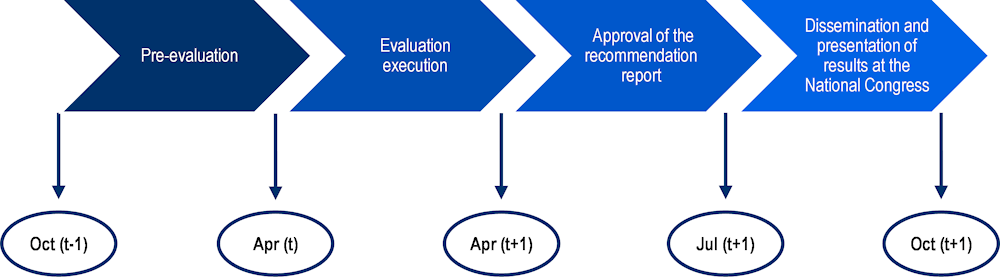

1. This council approves the criteria for the selection of public policies to be evaluated, observing the aspects of materiality, criticality and relevance, among others, and approves the annual list of public policies to be evaluated and their changes, as well as the evaluation annual plan. Each ex post evaluation cycle has 4 phases that last 24 months overall. Thus, the cycle of the reference year (t) begins in October of the previous year (t-1) and ends in September of the following year (t+1) (Ministerio da Economia, 2020[9]).

2. Evaluations and assessments are presented to managers who, in turn, are required to submit an action plan. This is meant to make assessment effective in transforming policies but is often disregarded by managers. There is a need to create incentives for managers to implement recommendations.

3. The council meets on an ordinary basis every six months and on an extraordinary basis whenever called by the co‑ordinator. The structure of CMAP comprises:

The Direct Spending Monitoring and Evaluation Committee (CMAG), with the purpose of providing technical support to the attributions of CMAP with regard to public policies financed by direct spending.

The Committee for Monitoring and Evaluation of Government Grants (CMAS), with the purpose of providing technical support to the duties of CMAP with regard to public policies financed by union subsidies (subsidios da uniao).

4. CMAP committees prepare and submit to CMAP for approval:

The criteria for the selection of public policies to be evaluated.

The annual list of public policies to be evaluated, according to the established criteria, and the evaluation schedule.

Benchmarks for public policy evaluation methodologies.

The recommendations of technical criteria for the preparation of feasibility studies for public policy proposals to the management bodies.

The proposed changes to the evaluated public policies.

5. Additionally, they evaluate the selected public policies, with the collaboration of the management bodies of these policies or in partnership with public or private entities and monitor the implementation of the evaluation’s recommendations (task executed by the Office of the Comptroller General). They also request information on public policies from line ministries, in particular those selected for evaluation by CMAP. Last, they ensure the active transparency of its actions and disclose to the managing bodies the methodological references and the criteria approved by the council and edit the acts necessary for its exercise of power.

6. Figure 4.1 describes the Brazilian process and timeline for policy evaluation.

Figure 4.1. Evaluation timeline in Brazil

The presence of well-defined policy evaluation mandates does not imply per se the successful development of an evaluation system across government. Factors such as the political system, public administration cultures and the rationale for evaluation shape the development and characteristics of evaluation cultures (OECD, 2020[4]). A successful evaluation system, in which evaluations are systematically used to improve public governance practices, policy making and service delivery, requires a framework actively promoting the quality of evaluations and the use of their results in decision-making processes. This entails modifying factors outside the sphere of evaluation, such as the availability of data, the co‑ordination instruments across government and the mechanisms for stakeholder engagement, among others (OECD, 2020[11]).

Improving the quality of M&E

A sound legal framework for M&E is not enough. There should be mechanisms in place to control and improve the quality of M&E practices. High-quality M&E generates robust and credible results that can be used with confidence, enabling policies to be improved. Quality M&E also has the potential to increase policy accountability as it can provide trustworthy evidence on how resources were spent, what benefits were achieved and what the returns were. Conversely, poor-quality M&E carries the risk of providing unfit evidence, or evidence that is subject to bias and undue influence. Poor-quality M&E also implies that a policy that is ineffective, or even harmful, might either be implemented or continue to be. Finally, opportunities to use public funds more effectively may be missed (OECD, 2020[4]).

Quality of monitoring: Lack of quality assurance mechanisms beyond the PPA and challenges in the interoperability of data

Some countries have created mechanisms to ensure that monitoring is properly conducted, that is to say that the process of collecting and analysing respects certain quality criteria. In order to do so, countries have developed quality assurance and quality control mechanisms. Box 4.3 explores in more detail the difference between both.

Box 4.3. Quality assurance and quality control in monitoring

Quality assurance mechanisms ensure that monitoring is properly conducted. To achieve this, countries have developed quality standards for monitoring. These standards and guidelines serve to impose a certain uniformity in the monitoring process across government (Picciotto, 2007[12]).

While some governments may choose to create one standard, others may consider it more appropriate to adopt different approaches depending on the different purposes of data use (Van Ooijen, Ubaldi and Welby, 2019[13]). Data cleaning activities or the automating of data collection processes can also be considered quality assurance mechanisms. Some countries have invested in the use of artificial intelligence and machine learning to help identify data that deviate from established levels of quality (Van Ooijen, Ubaldi and Welby, 2019[13]).

In various countries, quality control mechanisms have also been developed. Mechanisms for quality control ensure that the data collection and analysis have been properly conducted to meet the predetermined quality criteria. While quality assurance mechanisms seek to ensure credibility in how the evaluation is conducted (the process), quality control tools ensure that the end product of monitoring (the performance data) meets a certain standard for quality. Both are key elements to ensuring the robustness of a monitoring system (HM Treasury, 2011[14]). Quality control mechanisms can take the form of audits. Approaches that seek to communicate performance data or make them available to public scrutiny can also be included in quality control efforts in that multiple eyes are examining the data and potentially confirming the quality (Van Ooijen, Ubaldi and Welby, 2019[13]).

Source: OECD (2021[1]), Monitoring and Evaluating the Strategic Plan of Nuevo León 2015-2030: Using Evidence to Achieve Sustainable Development, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/8ba79961-en; Picciotto, S. (2007[12]), “Constructing compliance: Game playing, tax law, and the regulatory state”, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9930.2007.00243.x; Van Ooijen, C., B. Ubaldi and B. Welby (2019[13]), “A data-driven public sector: Enabling the strategic use of data for productive, inclusive and trustworthy governance”, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/09ab162c-en; HM Treasury (2011[14]), Magenta Book: Central Government Guidance on Evaluation, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/879438/HMT_Magenta_Book.pdf.

PPA monitoring benefits from a number of systematic quality assurance and control mechanisms. Among these:

The PPA Technical Manual gives guidance towards carrying out quality monitoring processes. It establishes specific criteria and objectives for monitoring the PPA. It is worth noting that the PPA Technical Manual includes guidance relating to the Monitoring Plan and a model of the plan in the annex, which can help foster quality monitoring processes for the PPA.

The Integrated Planning and Budgeting System (SIOP) is a tool that gathers information about the implementation of the PPA programmes, with their respective objectives, goals, indicators and intermediate results. It involves all government entities responsible for these respective attributes (Ministerio da Economia, 2020[9]). This goes for Brazil’s PPA – the baseline for government planning and budgeting – which is available transparently in open data format. That includes data about its structure, goals and initiatives, as well as the indicators used for its assessments.1

Beyond the scope of the PPA, there are no quality assurance mechanisms in place for monitoring (OECD, 2017[15]), potentially leading to low-quality monitoring outside of the PPA. Quality assurance is key to ensuring the robustness of evaluations so the Brazilian government should also consider developing quality assurance mechanisms for monitoring systems outside of the PPA (OECD, 2020[4]).

One element affecting the quality of monitoring is the variety of data management systems within the Brazilian government and the resulting challenges related to interoperability. Information sharing and joint data collection of the different units and institutions were reported to be challenging for the CoG’s functioning. Ideally, existing data provided to the CoG creates “one version of the truth” and is effectively used to improve performance. Stakeholders interviewed during this project suggested Brazil has a large volume of data and registers but access to these platforms for monitoring and evaluation is challenging as they were largely developed by each agency for a specific purpose. In addition to data provided by public institutions, various CoG institutions started to obtain data from IPEA.

For example, IPEA has a private data-sharing platform where researchers can access a variety of data. Additionally, it established a system through which, to have access to data, in the pre-assessment meetings, entities need to indicate which data they need and make formal requests to different ministries. The CGU also tried to build a similar platform internally. Nevertheless, there is no communication mechanism to avoid the formation of information silos across different institutions.

This happens despite the existence of open data policies that make open access compulsory for evaluation and decision-making processes. Decree No. 8.777 (2016) makes it mandatory for every government body to publish an Open Data Plan, to improve the availability of the government’s datasets in open data standards. The other main instruments that govern the Open Data Policy are Decree No. 9.903 of 2019 and Resolution No. 3 of the INDA Steering Committee (Comite Gestor da INDA, CGINDA).

Some initiatives have nevertheless been put in place to integrate these various data management systems. Among these, the Integrated Planning-Budget System (SIOP) gathers monitoring information and the Institutional Strategic Planning will be published on the website, so data will be transparent for all stakeholders. SIOP is a tool that gathers information on the implementation of the programmes, with their respective objective, target, indicator and intermediate results, and involves all of the government entities responsible for these attributes.

Additionally, aware of the need to improve the coherence of digital services provision across the federal administration, the Brazilian government launched the Digital Citizenship Platform (Plataforma de Cidadania Digital) in December 2016. The cross-cutting initiative is focused on transforming the delivery of public services online through the improvement of the Services Portal (Portal de Serviços), the development of a unique digital authentication system and an increase in the number of fully transactional services. This will better allow the evaluation of citizens’ satisfaction with digital services and improve the global monitoring of digital service delivery (OECD, 2018[16]).

Evidence from the fact-finding mission suggests that the Brazilian CoG could consider strengthening its capacity to integrate and manage performance information through the creation of dialogue platforms, i.e. mechanisms that enable policy and decision-makers to engage on a regular basis across institutions, where integration among different public bodies can happen, to avoid the existing silos effect. Building centralised access to data could help achieve a clear M&E mechanism that works across institutions. By creating better access to data, the use of data-driven reviews could be incremented (Box 4.4).

Box 4.4. Data-driven reviews

Data-driven reviews assess data on progress, typically against priority goals, and can be a powerful tool at the CoG. Using data to regularly track progress allows for a continued focus on priorities that does not fade after major policy announcements. Additionally, the use of data-driven reviews can create a learning culture that aims at improving knowledge of what works and how to improve the implementation of programmes.

Successful data-driven reviews require a clear focus on progress towards the goals and clearly defined priority goals, as well as data and sophisticated analytical skills to interpret data and present solutions for adjusting the identified issues. One of the major obstacles to data-driven reviews are limits of access, availability, sharing and quality of data across governments. Thus, it is important to identify the range of existing data that could be leveraged for data-driven reviews without having to create a new burden. Additionally, some line ministries could perceive negatively scrutiny from the CoG on implementation. Thus, for data-driven reviews to be successful, the CoG should persuade line ministries that data-driven reviews’ goal is to assist with better implementation rather than just creating stronger forms of accountability.

Source: Brown, D., J. Kohli and S. Mignotte (2021[17]), “Tools at the centre of government: Research and practitioners’ insight”.

Producing quality indicators is still a challenge for Brazil

In general, indicators act as feedback mechanisms for governments to know what is working and what needs to be improved and they connect activities to objectives, strategic goals and ultimately the mission (OECD, 2017[15]). Producing quality indicators is still a challenge for Brazil, mainly due to a lack of data interoperability, competencies and guidance on assessing the quality of indicators, and time lag of available data (it is common for the information made available through indicators to be outdated).

Specifically, there is a lack of clarity regarding key performance indicators (KPIs) and/or key national indicators (KNIs). KPIs are those performance indicators that aim at measuring the progress towards meeting the highest-level goals. KPIs that focus on a broad and balanced perspective of the organisation can offer great insight into its functioning and be a helpful tool for performance management (EC, 2020[18]). While in some countries considered as KPIs, KNIs being part of a strategic planning system and referring to government activity, in others, KNIs are based on traditional macroeconomic indicators, developed by national statistical services (INTOSAI, 2013[19]).

As part of its EFD, IPEA has defined in 2020 a set of KNIs based on broad socio-economic goals. Some of them are for instance the Human Development Index or the World Economic Forum (WEF) Global Competitiveness Index. While these types of indicators can provide a broad understanding of how Brazil is performing in socio-economic areas, they do not help to measure government performance or, more specifically, how government policies are contributing to improved outcomes. There is no clarity on how these indicators are going to be used to improve policy performance in Brazil.

In addition, key stakeholders from the government of Brazil had contrasting views about the existence or not of KPIs and KNIs, which shows that there is limited ownership and socialisation of the current KNIs and a lack of clarity about their potential use to assess government performance. There was no consensus about which would be the body in Brazil in charge of developing KPIs and, most importantly, who should be in charge of monitoring them. While some actors have expressed that the PPA’s indicators are the KPIs that the government uses to measure success in the implementation of public policies, other bodies have mentioned KNIs developed in the framework of the EFD. Overall, the main challenge identified by the government of Brazil is to select a few indicators that are recognised, have a reliable statistical base and data that can be compared with indicators used by other countries.

As discussed in the previous chapters, the development of a performance framework at the CoG would facilitate a better organisation of CoG efforts around a limited set of priorities and indicators. Without a clear systematic framework which allows discussion on performance, the development of KPIs might be a futile endeavour, as no mechanisms will exist to effectively identify success factors, implementation barriers and promote organisational learning oriented to outcomes. The National Performance Framework of Scotland (Box 4.5) constitutes a good example of integrating KPIs into a broader performance framework.

Additionally, as mentioned in Chapter 3, Brazil does not carry out performance budgeting as a general practice. Consequently, the KPIs will not be able to measure spending performance, nor can they be used to link spending performance to the achievement of strategic planning objectives. This is in line with the general siloed approach in this area, which often results in limitations on the effectiveness of the M&E system overall. Brazil would like to consider developing integrated efforts to link, in the future, performance budgeting to a set of KPIs.

Box 4.5. The National Performance Framework of Scotland

The National Performance Framework of Scotland offers a goal for the Scottish society to achieve. To help achieve this purpose, the framework sets National Outcomes that reflect the values and aspirations of the people of Scotland, which are aligned with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals and help to track progress in reducing inequality. These outcomes include:

“We have a globally competitive, entrepreneurial, inclusive and sustainable economy”, in regard to the Scottish economy.

“We are healthy and active”, in regard to health.

“We respect, protect and fulfil human rights and live free from discrimination”, in regard to human rights.

Each National Outcome has a set of 81 outcome-level indicators updated on a regular basis to inform the government on how their administration is performing concerning the framework. A data dashboard where citizens can access data on these indicators is available on the Scottish Government Equality Evidence Finder website.

Source: Government of Scotland (2020[20]), National Performance Framework.

Finally, while involving a technical body such as IPEA in the definition of indicators is aligned with OECD good practice, the lack of clarity about the existence or not of KPIs among key CoG stakeholders is an indication of their lack of socialisation/ownership within and outside the administration. Increasing stakeholder engagement in the development of KPIs can increase their legitimacy as well as their quality, as stakeholders may sometimes be better placed in order to identify which dimensions of change should constitute the focus of attention (DG NEAR, 2016[21]).

Concerning the quality of indicators, a number of guidelines on producing quality indicators exist in Brazil, but they are not systematically used. These include:

The Federal Court of Accounts – Brazil (Tribunal de Contas da União, TCU) 2010 Performance Audit Manual elaborates on challenges managers may face in creating performance information, including inadequate or unreliable information systems as well as the difficulty in linking outcomes to specific policies or actions (TCU, 2010[22]). The manual offers general considerations for assessing the quality of indicators (OECD, 2017[15]).

The Guide for Strategic Management (Guia técnico de Gestão Estratégica), elaborated by the Special Secretariat for Debureaucratisation, Management and Digital Government (Secretaria Especial de Desburocratização, Gestão e Governo Digital) within the Ministry of Economy, which provides recommendations for the formulation of indicators, especially for Institutional Strategic Plans (PEIs).

The Secretariat for Evaluation, Planning, Energy and Lottery (SECAP) Guidelines of Indicators of the PPA 2020-2023. These guidelines have the following objectives:

Present a theoretical-conceptual review of indicators.

Assist line ministries and agencies in choosing the most appropriate indicators for the M&E of its PPA 2020-2023 programmes.

Encourage and induce the use of indicators to improve programme governance and actions, considering the aspects of efficiency and, above all, effectiveness.

Despite the existence of these guidelines, one of the main barriers has to do with the lack of competencies in government institutions for the definition and analysis of KPIs. The Office of Comptroller General (CGU), for example, is trying to establish indicators but is encountering difficulties in doing so. The Public Policy Monitoring and Evaluation Council (CMAP) is working to establish a set of indicators based on the results of some evaluations but also as a way to generate evidence that can support decision-making in the budget cycle. Thus, institutions sometimes reach for support in the design of indicators from external institutions such as the National School of Public Administration (ENAP).

Last, some entities are publishing their indicators. The Minister of Economy, for example, will soon publish its indicators on its website. Nevertheless, even when indicators are publicly available, this does not ensure effective communication to the larger public.

Quality of evaluations: Guidelines on policy evaluation and other mechanisms to promote quality

Like the majority of countries (20 out of 31 countries, of which 17 are members of OECD) (OECD, 2020[4]) Brazil has developed guidelines that seek to address both the technical quality and good governance of evaluations. Guidelines developed by countries address a wide variety of specific topics including: the design of evaluation approaches, the course of action for commissioning evaluations, planning out evaluations, designing data collection methods, evaluation methodologies or the ethical conduct of evaluators. Table 4.3 gives an overview of the different quality standards, in terms of governance and quality that OECD and non-OECD member countries have included in their guidelines.

Guidelines on policy evaluation and other mechanisms to promote quality are available to the Brazilian CoG:

The Practical Guide for Ex Ante Analysis (Guia Prático de Análise Ex Ante) (Ipea, 2018[23]) includes useful guidance on the following matters:

When an ex ante analysis should be carried out and who has the competencies to execute it. It also includes a checklist and practical examples for ex ante analysis.

Technical information related to logical models, creation of indicators and SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats) analysis.

Information on the objectives of budgetary and financial analyses, implementation strategies, strategies to build confidence and support, general strategies on monitoring, evaluation and control, and measurement of economic and social return. Although this information is all useful to the design of a policy, including its evaluation, it does not provide practical guidance regarding the execution of quality ex ante evaluation processes.

The Practical Guide for Ex Post Analysis (Guia Prático de Análise Ex Post) (Ipea, 2018[24]) is intended to be a reference for the CMAG (for budgetary policies that it evaluates) and the CMAS (for public policies financed by the union’s subsidies). This guide provides:

A definition of public policy evaluation, public policies and monitoring. It also clearly states the importance to distinguish monitoring from evaluation practices.

Examples of M&E systems in other countries.

A figure detailing a chronologic and co‑ordinated evaluation process: selection of public policies to be evaluated, execution of evaluation, presentation of results and propositions for improvements, pact for improvements to be made in public policy, implementation of improvements and finally the improvement of the public policy.

A description of a federal government information and data system, such as the Govdata platform,2 and its legal framework.

A list of steps to manage information for the integration of policy evaluation.

Information on different types of evaluation (evaluation of results, impact, efficiency, etc.) and their objectives.

Information on the link between evaluation and budgetary management and requirements.

Technical information for carrying out evaluations, such as a step-by-step guide to realise executive evaluations, evaluations of design, implementation, governance of public policies, results, impact and economic and social return evaluations (with examples).

The Brazilian Regulatory Impact Analysis Guidelines (Guia de Análise de Impacto Regulatório) (SEAE, 2020[25]) is an example of a useful document for driving quality evaluations. In June 2008, the Brazilian government issued its first Regulatory Impact Analysis (RIA) Guidelines (published as RIA Guidebook). It is co‑ordinated by the Undersecretariat for Analysis and Assessment of Government Policies (SAG) (Guimaraes, 2020[26]). In the scope of the RIA Guidebook, SAG has also worked with the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Planning (which both merged under the Ministry of Economy in 2019).

With regards to stakeholder engagement, the guidelines stress the importance of public consultations during the RIA process and provide recommendations on when these should occur (Guimaraes, 2020[26]). Stakeholder engagement has been one of the key concerns of SAG and several other regulatory bodies, which recommend occurrence during two moments of the RIA process: before the new rule is drafted or amended and after the RIA report is agreed upon.

They refer to the Magenta Book3 to describe different types of evaluation (i.e. process, impact and economic evaluations) and how stakeholders should be engaged in each (Guimaraes, 2020[26]).

They also make a clear distinction between ex ante and ex post M&E (Guimaraes, 2020[26]).

They draw attention to Regulatory Outcome Evaluation (ROE), which they define as “the systematic evaluation process of an intervention to determine whether its objectives have been achieved” (SEAE, 2020[25]) and describe as a form of ex post evaluation. They oppose it to RIA, a “form of ex ante policy analysis” and stress that ROE should not be confused with RIA’s inspection of the monitoring process. As for ROE, or ex post RIA, the guidelines also state when an ROE should be conducted, i.e. the different cases in which they should be conducted and the timing for their conduction.

Table 4.3. Quality standards included in evaluation guidelines

|

Technical quality of evaluations |

Good governance of evaluations |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Identification and design of evaluation approaches |

Course of action for commissioning evaluations |

Establishment of a calendar for policy evaluation |

Identification of human and financial resources |

Design of data collection methods |

Quality standards of evaluations |

Independence of the evaluations |

Ethical conduct of evaluations |

None of the above |

|

|

Australia |

○ |

○ |

○ |

● |

○ |

○ |

○ |

○ |

○ |

|

Austria |

○ |

○ |

○ |

● |

● |

○ |

○ |

○ |

○ |

|

Canada |

● |

○ |

○ |

○ |

● |

● |

● |

● |

○ |

|

Colombia |

● |

● |

○ |

○ |

○ |

○ |

● |

● |

○ |

|

Costa Rica |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

○ |

|

Czech Republic |

● |

○ |

○ |

○ |

● |

● |

● |

● |

○ |

|

Estonia |

● |

● |

○ |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

○ |

|

Finland |

○ |

● |

● |

○ |

○ |

● |

● |

● |

○ |

|

France |

● |

○ |

○ |

○ |

○ |

○ |

○ |

○ |

○ |

|

Germany |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

○ |

|

Great Britain |

● |

○ |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

○ |

|

Greece |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

○ |

○ |

|

Ireland |

● |

○ |

○ |

○ |

● |

● |

● |

○ |

○ |

|

Italy |

○ |

● |

○ |

● |

○ |

○ |

● |

○ |

○ |

|

Japan |

● |

○ |

● |

○ |

● |

● |

○ |

○ |

○ |

|

Korea |

● |

○ |

● |

○ |

● |

● |

○ |

○ |

○ |

|

Latvia |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

○ |

○ |

○ |

|

Lithuania |

● |

○ |

○ |

● |

● |

○ |

● |

○ |

○ |

|

Mexico |

● |

● |

● |

○ |

○ |

● |

● |

● |

○ |

|

Netherlands |

○ |

○ |

○ |

○ |

○ |

● |

○ |

○ |

○ |

|

New Zealand |

● |

● |

○ |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

○ |

|

Norway |

● |

○ |

○ |

● |

● |

○ |

○ |

○ |

○ |

|

Poland |

○ |

○ |

● |

○ |

● |

● |

● |

○ |

○ |

|

Portugal |

○ |

● |

○ |

○ |

○ |

○ |

○ |

○ |

○ |

|

Slovak Republic |

● |

○ |

○ |

○ |

○ |

● |

● |

○ |

○ |

|

Spain |

● |

● |

○ |

● |

○ |

● |

● |

● |

○ |

|

Switzerland |

○ |

○ |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

○ |

|

United States |

● |

○ |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

○ |

|

OECD total |

|||||||||

|

● Yes |

20 |

12 |

12 |

15 |

18 |

20 |

19 |

13 |

0 |

|

○ No |

8 |

16 |

16 |

13 |

10 |

8 |

9 |

15 |

27 |

|

Argentina |

○ |

● |

● |

○ |

● |

○ |

○ |

○ |

○ |

|

Brazil |

● |

● |

○ |

● |

● |

● |

● |

○ |

○ |

|

Kazakhstan |

○ |

○ |

● |

○ |

○ |

○ |

○ |

○ |

○ |

Note: n=31 (28 OECD member countries). Eleven countries (9 OECD member countries) answered that they do not have guidelines to support the implementation of policy evaluation across governments. Answers reflect responses to the question: “Do the guidelines contain specific guidance related to the: [see column headings] (Check all that apply)”.

Source: OECD (2020[4]), Improving Governance with Policy Evaluation: Lessons From Country Experiences, https://doi.org/10.1787/89b1577d-en.

The Practical Guide for Ex Ante Analysis (Ipea, 2018[23])and the Practical Guide for Ex Post Analysis (Ipea, 2018[24])are provided by Casa Civil, with the collaboration of the Institute of Applied Economic Research (IPEA), the Ministry of Economy, the Office of the Comptroller General (CGU) and other line ministries, and have been approved by the Inter-ministerial Governance Committee (CIG). They can be used by other actors than CMAP (CMAG/CMAS). It should be noted that all evaluations submitted to CMAP must follow the guidelines of the Practical Guide for Ex Ante Analysis and/or the Practical Guide for Ex Post Analysis for the evaluation of public policies.

The CGU performs consulting assessment services, within the scope of its role of internal audit, in accordance with the Technical Reference (Normative Instruction SFC/CGU No. 3, of 9 June 2017). The Technical Reference, together with the manual of technical guidelines for the governmental internal audit activity of the Federal Executive Branch (Normative Instruction SFC/CGU No. 8, of 6 December 2017), provide a framework for assessments of various objectives evaluated within the scope of internal audit activities, as well as serving as a subsidy to the assessment work conducted by its teams within the scope of CMAP.

Additionally, during the last cycle, CMAP has improved evaluation networks and strengthened the roster of evaluators. Evaluators have different backgrounds, such as research institutes, universities, non-profit organisations and international organisations.

Finally, the CGU has developed guidelines based on international best practices for the internal audit activity for planning and carrying out evaluations based on risks and supported by evidence, with targets for increasing its level of technical maturity according to the internal audit capacity model. The experience and improvement of audit teams acquired by conducting public policy evaluations, as well as their physical presence throughout the national territory, allows them to obtain evidence in different ways, whether through the use of big data techniques or often by collecting the necessary evidence directly from the policy’s beneficiaries.

Skills and capacities for M&E are heterogeneous across institutions in Brazil

Relevant competencies and capacity for M&E are important as individuals with the right skillset are more likely to produce high-quality and utilisation-focused evaluations and assessments (McGuire and Zorzi, 2005[27]). The right competencies imply having the appropriate skills, knowledge, experience and abilities. In Brazil, the Ministry of Economy promotes training to develop skills, competencies and/or qualifications of evaluators. The government runs this training through its schools of government – such as the National School of Public Administration (ENAP) – and has the technical assistance of IPEA. This is in line with other OECD countries, the majority of which have recognised the important role of competencies in promoting quality evaluations. In fact, survey data show that the majority of countries (17 main respondents, of which 13 OECD countries) use mechanisms to support evaluators’ competencies development (OECD, 2020[4]).

Despite the existence of well-developed capacities, in Brazil, there is a lack of experts trained to carry out evaluations. The number of existing experts does not sustain the need for assessments, especially in times of emergency. Sectoral organs are encouraged to make assessments in their own body but this can be challenging as they rarely have a large enough workforce to sustain their needs. Therefore, capacity building and training could be helpful in Brazil. Moreover, this could create a multiplying effect and lead to a significant increase in the number of professionals able to carry out evaluations.

Some actors closely related to the CoG, such as ENAP, IPEA and the IBGE have the capacities and competencies to ensure that quality evaluation activities are conducted. The secretariats of the Ministry of Economy (National Treasury Secretariat - STN, Federal Budget Secretariat - SOF, SECAP) and the CGU are also capable of co‑ordinating and executing different types of evaluations.

IPEA, for instance, can itself carry out evaluations and has contributed to the co‑ordination and execution of evaluations, besides supporting CMAP in a project to develop an Inventory of Federal Public Policies. They also have a programme to foster research through scholarships and bring evaluators from academia to help with assessments.

The IBGE can help with the provision of data and information bases.

ENAP can provide training to policy makers in charge of the evaluation. The school has an increasing role in disseminating good practices or guidelines to foster quality processes and results. ENAP offers training, especially practical courses on both ex ante and ex post assessment of public policies and technical advice on public policy evaluations.

The CGU can assist in evaluation activities by offering consultancy. This is possible because of its capillarity in the national territory and because audits, including those aimed at evaluating public policies, are processes conducted in a systematic and disciplined manner, including with the existence of a quality assurance programme. The expertise CGU gained over the years can serve as a reference for sectoral bodies when carrying out their own public policy assessments.

These bodies may also exercise the function of co‑ordinator or executor of the evaluations carried out within the scope of CMAP. The co‑ordinator is responsible for preparing the work plan, ensuring the execution of the evaluation, assessing the risks that may impact the results, presenting the intermediate products to the committee, the final evaluation report and the recommendations report.

Another interesting initiative for the promotion of capacity building is the collaboration between ENAP and the CLEAR Initiative, which is part of the World Bank Independent Evaluation Group (IEG). They hold seminars and workshops on M&E for civil servants, in addition to the co‑operation for capacity development in evaluation through ENAP’s Evaluation Advisory Services.

Although ENAP has been contributing to building the capacity of evaluation in the line ministries independently and also as an important supporter for CMAP, the way that line ministries carry out evaluations is heterogeneous in the federal government. Some ministries have excellent capacities but this is not true for others. Also, within ministries, there can be specific sectors that are more advanced than others in terms of capacities and skills for M&E. Brazil should make sure that there are basic analytical skills for M&E in all ministries, a critical mass of evaluation skills within each ministry in order to make sure that they can conduct evaluations and skills to commission and supervise evaluations at the senior civil service level.

A first step in strengthening the analytical capacities of the Brazilian public sector would be to assess the capacities and needs of the Brazilian government in terms of M&E skills. Such an exercise could be undertaken by IPEA or ENAP and inspired by the United Kingdom (UK) example of developing a Framework for Digital Professionals (Box 4.6).

Box 4.6. The UK Framework of Digital Professionals

In 2015, the UK Government Digital Services (GDS) started conducting a broad mapping of digital skills in the government to evaluate the capacities and needs of the UK government, to promote a modern and agile digitally driven civil service. This mapping looked at digital professionals as well as product manager, user researcher and delivery manager roles – all of which are indispensable for well-functioning digital services. This mapping exercise has shown that employees with such digital skills had different job titles, functions and salaries within the British public sector.

Based on this mapping, the GDS developed the Digital, Data and Technology Capability Framework that includes 37 jobs and identifies the skills needed for each of them, as well as the competencies needed to advance to a higher-level title within each job. This framework has helped the UK civil service address the issue of digital professionals’ recruitment and career advancement, identify capacity gaps to design training and facilitated the creation of a community of practice.

Source: OECD (2021[28]), “The future of the public service: Preparing the workforce for change in a context of uncertainty”, https://doi.org/10.1787/1a9499ff-en.

Also, according to the interviews carried out during the fact-finding missions, the allocation of capacities, i.e. how capacities are distributed among entities’ departments and/or teams, represents an issue. As a matter of fact, capacity allocation within entities can be dictated by inertia from past allocations and not adapted to the internal changes in capacity needs and thus, with a risk of resulting in a misallocation of the existing capacities and an under-exploitation of the existing human resources. A possible solution to this issue lies in co‑ordination but this resulted in being problematic due to the high heterogeneity of actors.

Last, investment in analytical capacities for M&E usually happens at the individual level. Instead, it would be advisable to put in place analytical structures for investment in analytical capacities within line ministries at the institutional level rather than at the individual level. This requires the elaboration of a government-wide strategy to attract and retain highly qualified analytical staff members. The Brazilian public sector could create an analytical track within the civil service framework, which could provide training in policy analysis and evaluation methods, appraisal methods, data and advanced quantitative methods, and applied economics. The graduates from this analytical track would be hired centrally and, then, dispersed to the analytical units within various ministries. These analysts could be offered relatively higher salaries, well-defined career trajectories and secondment opportunities, to increase the attractiveness of this professional stream. Several other OECD countries have created dedicated policy analysis tracks within the civil service (Box 4.7).

Box 4.7. Policy analysis tracks in France, Ireland and the UK

In Ireland, the Irish Government Economic and Evaluation Service (IGEES) has a role as an economic and analytical resource co‑ordinator across government. The IGEES manages a network of analytical staff who are hired centrally and later posted in line departments. IGEES staff conduct economic analysis and evaluations, and more generally contribute to better policy making in the line departments. The IGEES was launched in 2012 in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, initially aimed at ensuring the quality-for-money of public policies in response to budgetary pressures.

On average, 20 recent graduates are hired through this scheme every year, which brings the total number of analysts hired by the IGEES to over 150 across the government. The IGEES also supports network building and knowledge sharing by providing its staff with incentives for mobility: after an initial two‑year period, staff will move either within the department or to another department. A Learning and Development Framework has also been established whereby IGEES staff receive training in the following areas: policy analysis and evaluation methods, appraisal methods, data and advanced quantitative methods, and applied economics.

In the UK, there are around 15 000 “policy professionals” that work as analysts across the different government departments. The term regroups several professional tracks such as the government economic service, the government statistical service and the government social research service. The policy profession framework includes a two-year apprenticeship programme, as well as a three-year graduate scheme. There is also a common framework for all policy professionals, which includes a shared skillset (18 competencies in 3 areas: analysis and use of evidence, politics and democracy, policy delivery), 3 levels of expertise, as well as a clear training and career progression framework.

In France, the National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies (INSEE) has an inbuilt tertiary educational system, which trains a set of specialists in economic, statistical and econometric analysis through the ENSAE school, and statisticians and data scientists at the ENSAI school. A share of the graduates from these schools are to be enrolled in the civil service and receive a stipend during their studies in exchange for working in the civil service for a minimum period of eight years. Within the civil service, graduates from ENSAE/ENSAI serve in the analytical offices in each ministry, as well as a variety of public institutions such as France Stratégie or the Central Bank. At entry level, this pool of graduates is co‑ordinated centrally by INSEE, thus creating a shared marketplace for analytical and statistical skills across the public sector. In addition, the national institute also has an important role in fostering and developing analytical competencies across government, by providing professional training aimed at all civil servants, organising seminars to foster knowledge sharing and encouraging mobility of analytical staff between line ministries. The scheme, which has been operating since the inception of INSEE in 1946, was part of a set of key reforms aimed at modernising the civil service in the after-war recovery period to ensure that the French state apparatus would be well equipped to deal with modern challenges.

Source: OECD (2021[29]), Mobilising Evidence at the Centre of Government in Lithuania: Strengthening Decision Making and Policy Evaluation for Long-term Development, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/323e3500-en.

Promoting the use of M&E results

Using a system to measure the results in terms of performance and delivery is the main purpose of building an M&E setup. In other words, producing M&E results serves no purpose if this information does not get to the appropriate users in a timely fashion so that the performance feedback can be used to improve policies. Effective use of M&E results is key to embed them in policy-making processes and generate incentives for the dissemination of M&E practices. It is a critical source of feedback for generating new policies and developing a rationale for government interventions. If M&E results are not used, gaps will remain between what is known to be effective as suggested by evidence and policy, and decision-making in practice. Simply put, M&E results that are not used represent missed opportunities for learning and accountability (OECD, 2020[4]).

M&E information is shared and made public through different channels, depending on the issuing institution and the data involved

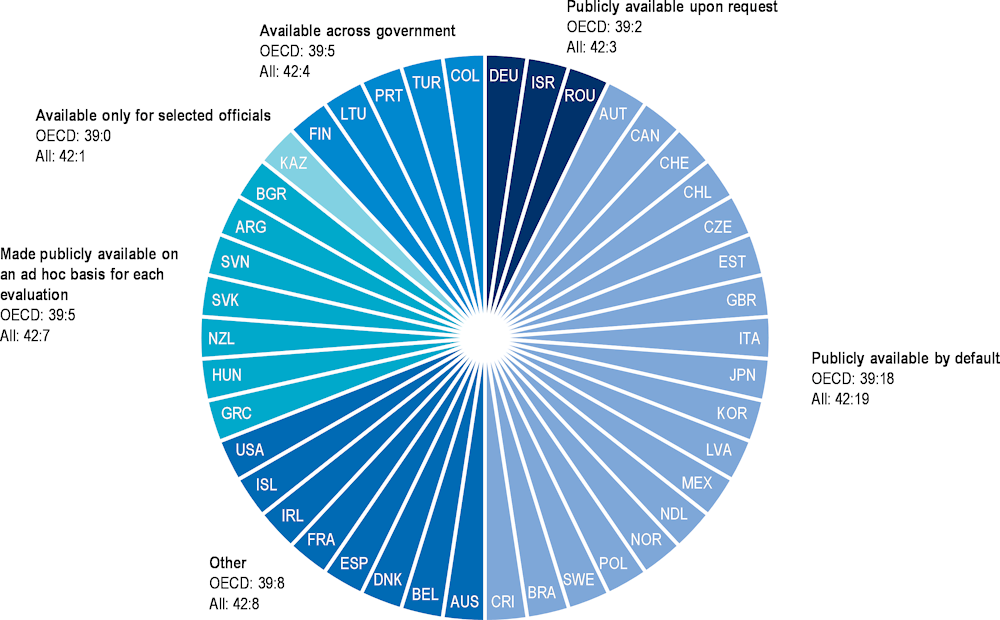

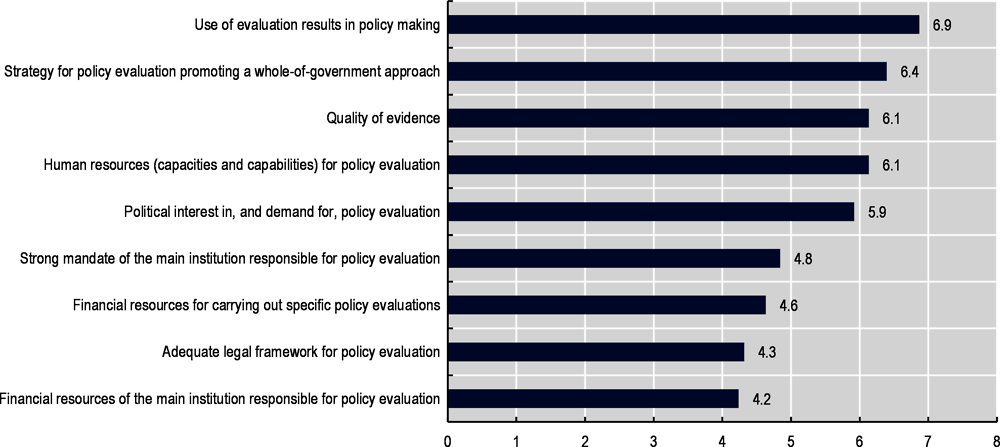

Making results public is an important element to ensure impact and thus increase the use of evaluations. Public access is an important factor in data use, as analysts may not otherwise be aware of existing data sets or may not have access to them. Evaluation results are increasingly made public by countries, through increased openness and transparency. As shown in Figure 4.2, the majority of countries make evaluation findings and recommendations available to the general public by default, for example by publishing the reports on the commissioning institution’s website. Such availability is important to promote use as, if citizens are aware of the results and implications, it may also build pressure on the policy makers to pay attention to the results and ensure that they feed into policy making (OECD, 2020[4]).

In Brazil, the sharing mechanisms for M&E information vary according to the issuing institution and the types of data involved. Some examples are:

The annual Pluriannual Plan (PPA) monitoring report provided for in Article 16 of Law No. 13.971, from 2019, forwarded to the National Congress, from 2021, until August of each year, and made available on the Ministry of Economy website4 (Ministerio da Economia, 2020[9]). A report with the results of the evaluations is also sent to the National Congress annually, starting from the 2020 Evaluation Cycle. Final evaluation reports and recommendation reports are available to the public, managers and public officials on the CMAP website.5