This chapter analyses the environmental factors contributing to child vulnerability. These factors operate at both the family and community level. Family factors include material deprivation, parents’ health and health behaviours, parents’ level of education, intimate partner violence and family stress. Community factors include schools and neighbourhoods. The analysis shows the strong inter-generational aspect of vulnerability and the concentration of vulnerable children within certain families and communities.

Changing the Odds for Vulnerable Children

3. Environmental factors that contribute to child vulnerability

Abstract

Introduction

This chapter provides an overview on the transmission of vulnerabilities in OECD countries through environmental factors. Environmental factors with a bearing on vulnerability operate at both the family and community levels. Contributory factors include material deprivation, poor parental health, low parental education, family stress, exposure to intimate partner violence, neighbourhood deprivation, and poor school environment. Although this list is not exhaustive, it does outline the inter-generational aspect of child vulnerability and the concentration of vulnerable children within certain families and communities.

Vulnerable children grow up in harsh environments where they are exposed to multiple adversities, greater hardships, and hazards. These environments provide fewer opportunities and protective factors. Intervening to improve outcomes for vulnerable children requires understanding fully the environment in which they live and the different factors that may hinder development and those that could enhance resilience.

Family Factors

Material deprivation

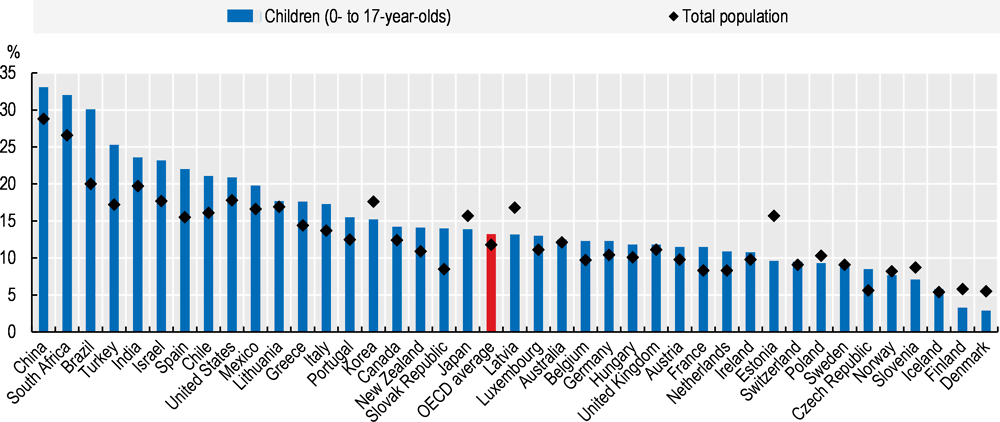

In OECD countries, children are overrepresented in income poor households: on average, one in seven children live in income poverty (Figure 3.1). Child poverty has been on the rise in about two-thirds of OECD countries since the 2008 financial crisis, partly due to the negative impact on employment for the most vulnerable populations (Thévenon et al., 2018[1]; OECD, 2018[2]). Overall, families with no working parent are six times more likely to be poor than those with at least one working parent. The poverty risk for single‑parent families is three times higher and is strongly dependent on the parent’s employment status. The level of deprivation for these families is often more intense. Moreover, the standard of living of poor families with children, particularly those with very low income, has declined in several countries.

Article 27 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) recognises the right of children to a standard of living “adequate to their physical, mental, spiritual, moral and social development” and the responsibility of parents and governments in fulfilling this right. Child material deprivation reflects the degree of difficulty faced by families in providing children with the minimum material conditions for an adequate standard of living. Broadly, the OECD defines material deprivation as the inability of individuals or households to afford consumption goods and activities that are typical in a society at a given point in time. Specific to children, the OECD measures material deprivation across seven dimensions1: nutrition, clothing, educational materials, housing conditions, social environment, leisure opportunities and social opportunities.

Figure 3.1. Nearly 1 in 7 children live in income poverty in the OECD

Note: Data are based on equivalised household disposable income, i.e. income after taxes and transfers adjusted for household size. The poverty threshold is set at 50% of median disposable income in each country. Data for China and India refer to 2011, for Brazil to 2013, for Hungary and New Zealand to 2014, and for Chile, Denmark, Iceland, Ireland, Japan, Switzerland, Turkey and South Africa to 2015.

Source: OECD Income Distribution Database, https://www.oecd.org/social/income-distribution-database.htm.

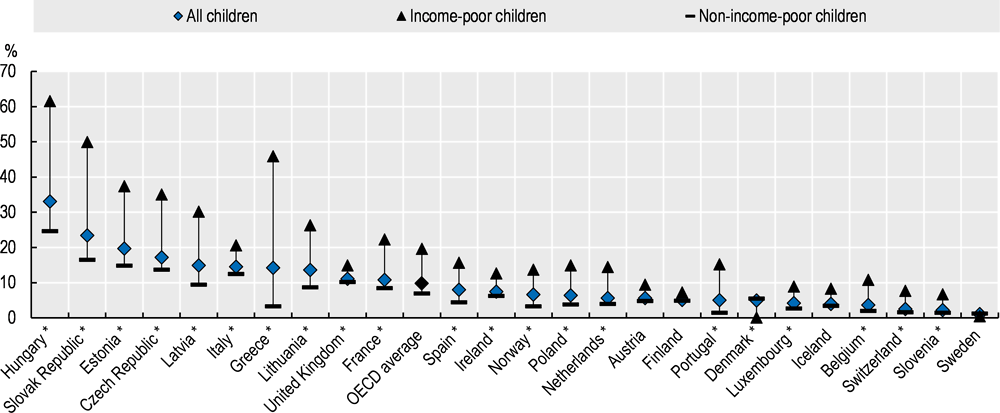

There is a strong link between material deprivation and income poverty. Nonetheless, non-income poor children can also experience material deprivation (Thevenon, Clarke and de Franclieu, forthcoming[3]). For instance, 20% of income poor children in European OECD countries experience food poverty, as do 7% of non‑income poor children. Overall, one in ten children do not have access to fresh fruit and vegetables and/or one meal including meat, chicken, fish or a vegetarian equivalent at least once a day (Figure 3.2). Poor nutrition negatively affects child development and health and interferes with children’s ability to perform well at school.

Along with family food budgets, access to cooking and food storage facilities and locally available food options determine children’s diets. For example, the diet of children in homeless families can deteriorate drastically during homeless episodes due to limited access to cooking and storage facilities, and restrictive budgets and meal times (Kourgialis; et al., 2001[4]; Share and Hennessy, 2017[5]). Schools and after-school clubs can play an important role in supplementing the diets of vulnerable children.

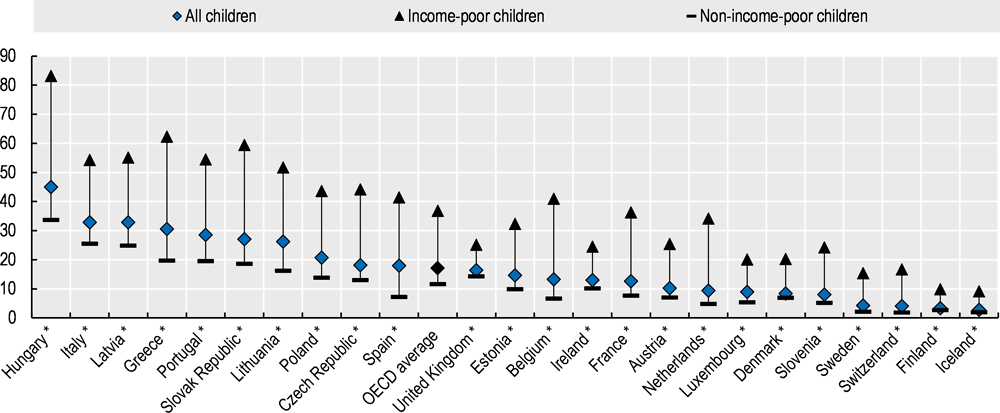

Figure 3.2. One in 10 school-age children experience food poverty or lack access to basic nutrition

Note: Percentage of children in households where at least one child does not eat “fruits and vegetables once a day” and/or “one meal with meat, chicken or fish (or vegetarian equivalent) at least once a day”. Countries are ranked according to deprivation among all children. In countries marked with an *, the difference between income-poor and non-income-poor children is statistically significant at p<0.05.

Source: OECD calculations based on the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) survey 2014; OECD Child well-being data Porta, www.oecd.org/els/family/child-well-being/data/.

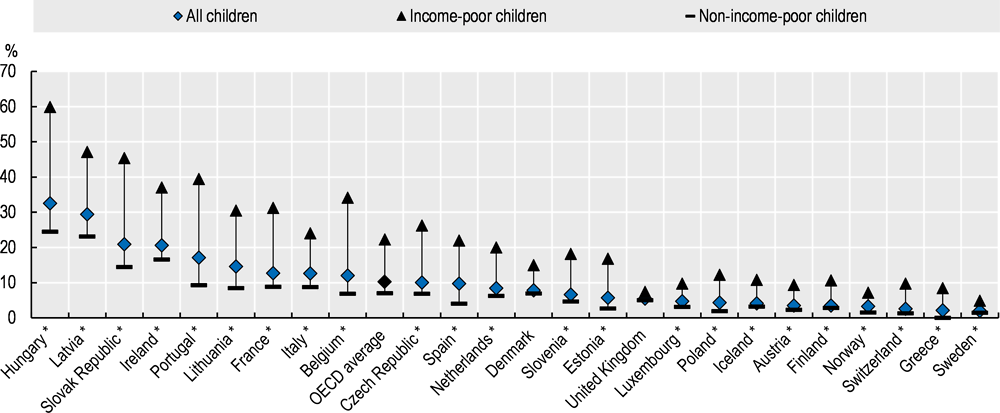

On average, one in ten children in European OECD countries lacks access to basic clothing (Figure 3.3), defined as the inability of parents to afford to replace worn-out clothes with new (not second-hand) clothes and to purchase two pairs of properly fitting shoes, including one pair of all-weather shoes. In just a few countries (Iceland, Luxemburg, Sweden and Switzerland), deprivation of food and clothing is relatively rare (less than 1 in 20 children) and the risk only slightly higher for poor children. However, in countries where it is more common for poor children to lack these basic items (e.g. Hungary, Latvia and Slovak Republic), children from non-income poor families are also more likely to be also affected.

Figure 3.3. One in ten school-age children live in households where at least one child lack access to basic clothing

Note: Percentage of children in households where at least one child does not have access to “some new (not second-hand) clothes” and/or “two pairs of properly fitting shoes (including a pair of all-weather shoes)”. Countries are ranked according to deprivation among all children. In countries marked with an *, the difference between income-poor and non-income-poor children is statistically significant at p<0.05.

Source: OECD calculations based on the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) survey 2014.

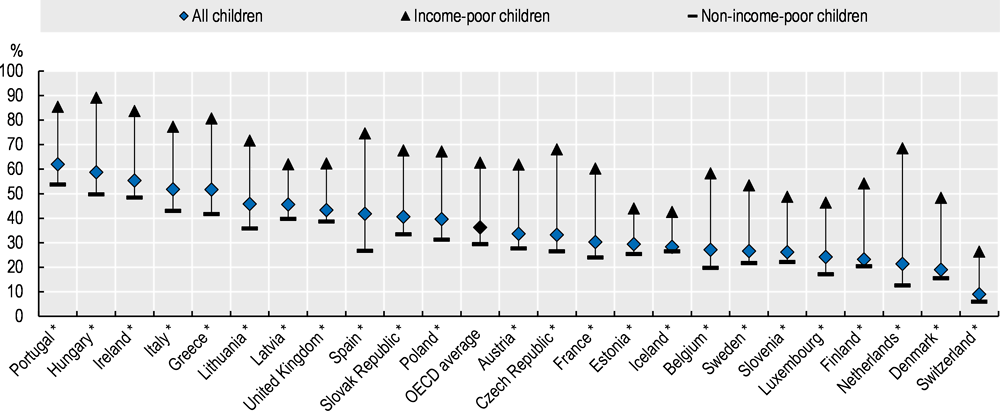

Participation in regular leisure activities helps children develop social skills, friendships, and positive subjective well-being, and is associated with improved educational outcomes. Leisure activities are especially important for vulnerable children, as they provide natural and consistent opportunities to interact with supportive adults and mentors, as well as time away from stressful home environments. One‑third of children in European OECD countries experience deprivation in leisure activities that incur a financial cost, such as weekly sports or music instruction or a yearly one-week holiday. In Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, and Portugal, more than half of children are deprived (Figure 3.4). On average, children from income poor families are more than twice as likely to be deprived of leisure activities.

Figure 3.4. One-third of school-age children experience deprivation of leisure activities

Note: Percentage of children in households where at least one child does not participate in a “regular leisure activity” and/or "go on holiday away from home at least one week per year”. Countries are ranked according to deprivation among all children. In countries marked with an *, the difference between income-poor and non-income-poor children is statistically significant at p<0.05.

Source: OECD calculations based on the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) survey 2014; OECD Child well-being data Porta, www.oecd.org/els/family/child-well-being/data.

Material deprivation is considered severe if children are deprived in at least four of seven dimensions (nutrition, clothing, educational materials, housing conditions, social environment, leisure opportunities and social opportunities). One in six children in European OECD countries is subject to severe material deprivation, although with a large variance across countries (Figure 3.5). The risk of severe deprivation is highly associated with income poverty: on average, 36% of children living in income poor households experience severe material deprivation, three times more than children who are not income poor. Further analysis of a number of European countries highlights that sub-groups of poor children are deprived in all dimensions: for instance, almost 20% in France and Spain, and 12% in the United Kingdom (Thevenon, Clarke and de Franclieu, forthcoming[3]). Severe material deprivation is more common among very low‑income families, and households where both parents are unemployed or headed by a single parent.

Figure 3.5. One in six children in European OECD countries experience severe deprivation

Note: Percentage of children deprived on at least four measures. Countries are ranked according to severe deprivation among all children. In countries marked with an *, the difference between income-poor and non-income-poor children is statistically significant at p<0.05.

Source: OECD calculations based on the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC); OECD Child well-being data Porta, www.oecd.org/els/family/child-well-being/data/.

The United States uses different criteria to assess children's material deprivation, but the resulting data suggests an even stronger link between material deprivation and income poverty.2 Between 2013 and 2017, almost 16% of children aged 6-17 experienced more than two types of deprivation. Forty-six percent of children living in poor households (i.e. with income below 100% of the federal poverty threshold) experienced multiple deprivations. This number decreases significantly as household income increases. Race and parental education correlate with child material deprivation: children from Hispanic or Native American backgrounds are more likely to experience multiple deprivations than children from white, Asian and Pacific Islander populations. Children of parents who did not complete secondary school experience material deprivation at almost twice the rate of children of parents who did. Similar to European countries, at least one unemployed parent in the household almost doubles the risk of multiple deprivations (Erickson et al., 2019[6]).

Homelessness

Homelessness is an extreme form of material deprivation that has serious implications for child development and well-being, and later adult outcomes (Radcliff et al., 2019[7]; Cobb-Clark and Zhu, 2015[8]; Buckner, 2008[9]).

Overall numbers of homeless children and young people are low, but the problem is growing in several OECD countries, and by significant levels in some. Homelessness among families with children almost quadrupled in Ireland between 2014 and 2018, from 407 to over 1 600 households. New Zealand recorded an increase of 44% between 2006 and 2013, representing more than 21 700 individuals in 2013. England recorded an increase of 42% between 2010 and 2017, representing 44 000 homeless families with children in 2017 (OECD, forthcoming[10]). In the United States, families with children represented one-third of the homeless population in 2018 (over 180 000 people in more than 56 300 families). Some areas saw a significant rise in family homelessness: between 2007 and 2018, both Massachusetts and Washington, DC had an increase in homelessness among families with children of more than 90%, while New York (state) saw a rise of 51% over the same period (HUD, 2018[11]).

Some OECD countries are experiencing a concerning rise in youth homelessness. Among countries with available data, youth homelessness has increased in Australia, Ireland, New Zealand and Portugal, among others. Ireland (15-29 years) recorded the largest increase, with a jump of 82% over just a four-year period from 2014 to 2018. Youth homelessness grew by 20% between 2011 and 2016 in Australia (15-29 years) and by 23% between 2006 and 2013 in New Zealand (15-29 years). In Australia and New Zealand, youth homelessness grew faster than that of the overall homeless population. Other OECD countries have recorded a decline in youth homelessness: Denmark (18-29 years) reported a decline between 2017‑2019, ending an uptrend that started in 2011, and England (16-24 years) a decline of 20% between 2010 and 2017 (OECD, forthcoming[10]).

The factors leading to family homelessness are complex and can result from an accumulation of family‑level and structural risk factors (EOH, 2017[12]; Fertig and Reingold, 2008[13]). Family-level factors include female-headed households, unemployment, relationship breakdowns, intimate partner violence, parental substance misuse and mental health difficulties, lack of social support, or exhausted support networks. As such, children are likely to have experienced trauma and other poverty-related adversities prior to becoming homeless. Structural factors – i.e. those beyond parents’ control – include lack of affordable housing, a weak labour market, inadequate social welfare provision, and limited availability of social housing and homeless accommodation. In Europe, the typical profile of a homeless family is one headed by a woman with a history of intimate partner violence, with one or more children in her care (EOH, 2017[12]).

Children in homeless families are much more likely to suffer from poor well-being. Broadly speaking, they are exposed to three levels of risk: risks specific to being homeless (e.g. living in a stressful shelter environment), risks linked to low-income households (e.g. community violence), and risks shared by children regardless of income level (e.g. biological and family-related factors) (Buckner, 2008[9]).

Family homelessness represents great difficulties for children over and above poverty alone (Cutuli et al., 2013[14]; Samuels et al., 2010[15]). It imposes a difficult set of stressors and adversities including poor diet and missing meals, increased anxiety, loss of independence, overcrowding and lack of privacy, repeated accommodation moves, loss of parental care if accommodated separately, loss of contact and support from family and friends, school placement disruption, and stigmatisation.

Homelessness is traumatic for children. It contributes to the isolation of already vulnerable families and puts high strain on established family and formal support networks, undermining resources available to assist recovery. A study on the distribution of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) among adults who experienced childhood homelessness compared with adults who did not found higher exposure to all 11 ACEs3 (Radcliff et al., 2019[7]). Being homeless is often heavily socially stigmatised; not only are children vulnerable to being bullied, but identity issues and mental health can be made much worse (Kilmer et al., 2012[16]).

Research has established correlations between homelessness and poor educational outcomes (Cutuli et al., 2013[14]; Obradović et al., 2009[17]). Homelessness generates school absenteeism, long school commutes and deprives children of home-based educational inputs, for example a place to study and parental time. A study on one large urban school district in the United States compared the academic progress and achievements in mathematics and reading of homeless or highly mobile (HHM) children from third to eighth grade (8-13 years old) with two other groups of low-income children (receipt of federal programme no-cost school meals or reduced-cost school meals) and the general student population. HHM children recorded significantly lower educational achievement with weaker signs of improvement over time compared with the general student population. In fact, children who were identified as HHM at any time during the five-year period recorded lower academic achievement compared to peers with stable accommodation, regardless of household income. The study revealed a risk gradient wherein the low‑income students progressively performed poorly, but HHM students exposed to the most risk performed the worst. No evidence indicated that this gap narrows over time (Cutuli et al., 2013[14]).

However, in the same study, 45% of HHM children showed academic resilience, scoring between and above the average range. The researchers suggest that this resilience, while linked to typical indicators for academic achievement such as school attendance and qualifying for academic support, was more significantly influenced by factors outside of those routinely assessed in schools. These include socio‑emotional regulation, the quality of peer relationships, achievement motivation, teacher quality and effective parenting (Cutuli et al., 2013[14]).

Research on the impact of family homelessness on other areas of child development and well-being is less developed. Nevertheless, available studies highlight that homelessness has a negative impact on child and adolescent physical and mental health when compared to outcomes for housing-secure peers (Edidin et al., 2012[18]; Weinreb et al., 1998[19]) and more frequent and severe adolescent mental health difficulties (Perlman et al., 2014[20]). A study on the mental health and resilience of homeless youth correlated positive relationships between parents and adolescents (parent connectedness) with higher social competencies and positive self-identity (Kessler et al., 2018[21]). This suggests that strengthening relationships with parents and other adults (e.g. school teachers and mentors) can help homeless youth cope with the disruption of homelessness and to navigate normal developmental tasks.

Housing insecurity (housing unaffordability and frequent accommodation moves and homelessness) contributes to child maltreatment, independent from poverty and economic hardships (Warren, 2015[22]). Lack of access to affordable and adequate housing compromises parents’ ability to meet children’s basic needs (neglect) through material deprivation. Moreover, housing insecurity is associated with physical and emotional abuse by reason of increased parental stress. Parenting responses can be linked with different types of stress: for example, overcrowding with increased punitive parenting styles and physical abuse, and housing instability with maternal distress and emotional abuse.

Parenting during periods of homelessness is extremely demanding. Parents encounter large difficulties in adequately meeting children’s needs while having little control over environmental circumstances. For young children, the quality of parent-child relationship is important in determining child outcomes but also parental competencies, such as problem solving skills (David, Gelberg and Suchman, 2012[23]). More needs to be learnt about parents who manage these pressures well, and how to better support those who struggle. Some families live in supported homeless accommodation and/or have formal support on transitioning out of homelessness, which present opportunities to build on parenting competencies.

Parents’ health and health behaviours

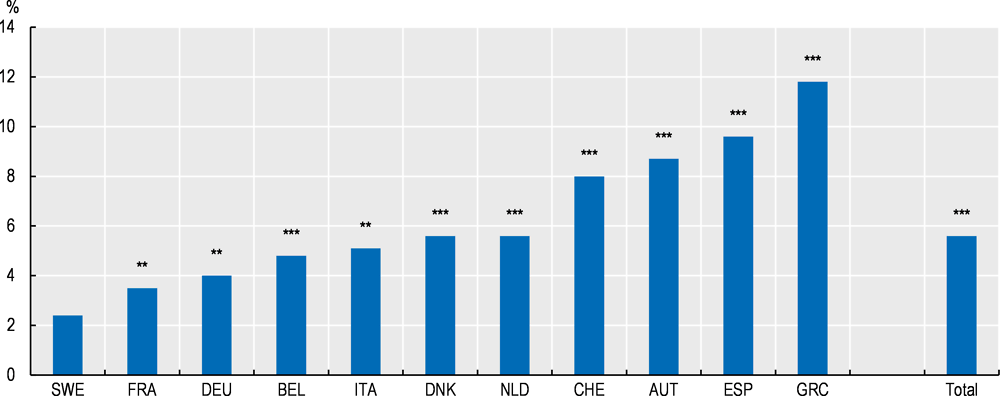

Childhood conditions can have a lifetime impact on health. On average, adults over 50 are 6% more likely to report poor health if they had a chronic disease at 10 years of age (after controlling for adult socio‑demographic characteristics such as education, employment status, marital status, age and wealth quintile) (Figure 3.6). The impact of early childhood conditions on health varies across European OECD countries: it is lower in France but the highest in southern European countries such as Greece and Spain. Sweden is the only country where no significant association between childhood conditions and adulthood has been found.

Figure 3.6. Relationship between poor childhood health and adult poor or fair self-assessed health

Note: The results show the percentage of poor or fair self-assessed health at current adult age attributable to self-reported chronic conditions at age 10. Any childhood health refers to chronic conditions which include diabetes or high blood sugar, heart trouble, severe headaches or migraines, epilepsy, fits or seizures, emotional, nervous or psychiatric problems, neoplastic diseases and other serious health conditions. Estimates are from a limited probability model. For further details, see Annex Table 5.A1.1 in OECD (2018), A Broken Social Elevator? How to Promote Social Mobility. ***, **, *: statistically significant at 1% and 5% levels, respectively.

Source: OECD (2018), "The impact of early childhood health on poor adult self-assessed health status", in A Broken Social Elevator? How to Promote Social Mobility, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264301085-graph79-en.

Childhood conditions with a bearing on adult health are multi-faceted and partly stem from risk factors that parents transmit to children, including biological factors and parental health behaviours. Biological determinants are important channels for the transmission of disadvantages from one generation to the next. Nonetheless, recent developments in epigenetics highlight that stressful early life experiences and exposure to environmental toxins can affect gene expression and influence long-term outcomes, including adult disease risk (Child, 2010[24]). Certain epigenetic changes can be transmitted across generations, compounding socio-economic disadvantage (Scorza et al., 2019[25]).

High socio-economic status during childhood moderates the genetic risk for smoking in adulthood (Bierut et al., 2018[26]). Genetically at-risk adult smokers from high socio-economic backgrounds tend to smoke roughly as many cigarettes at the peak (about 8% more) compared to non-genetic at risk adults from similar backgrounds, whereas there is a larger difference (about 28% more) for adults from low socio-economic backgrounds.

Genetic factors also interact strongly with childhood socioeconomic status and educational outcomes. Recent research suggests that specific gene variants predict educational attainment (Papageorge and Thom, 2018[27]). Yet, college graduation rates are stronger among children growing up in higher socio‑economic backgrounds, indicating that children in poor families encounter adversities that hold them back. This raises concerns about wasted potential among low-income children.

Parent’s health behaviours affect children’ health. Beginning in the pre-natal period and early childhood years, parents’ health behaviours have a persistent influence on subsequent child and later adult outcomes. Pre-term births and/or low birth weight are associated with poor maternal conditions (inadequate maternal nutrition, alcohol consumption, smoking, quality of prenatal care, and exposure to toxins during pregnancy). Pre-term birth and low birth weight can have adverse repercussions on later child health and education outcomes. Better educated families are more able overcome these early health disadvantages (Almond, Currie and Duque, 2018[28]; Currie, 2008[29]; Anderson, Doyle and Victorian Infant Collaborative Study Group, 2003[30]; Hack, Klein and Taylor, 1995[31]). A Chilean study found persistent effects of birth weight on educational achievements; a 10% increase in birth weight is associated with nearly a 0.05 standard deviations higher performance in math throughout first to eighth grade (Bharadwaj, Eberhard and Neilson, 2018a[32]). A Swedish study found that birth weight positively affects permanent income and income across large parts of the life-cycle (Bharadwaj, Lundborg and Rooth, 2018[33]).

Disparities in poor health at birth would have limited consequences if parents were able to offset them through specific investments, such as in access to high-quality healthcare and therapies, and a good diet. In reality, vulnerabilities inherited very early in life tend to become more pronounced over time, due to deepening socio-economic inequalities at the different stages of childhood and beyond. Longitudinal studies indicate that pre-natal and post-natal parental investments add up exponentially, but post-natal investments are less effective below a certain birthweight (Aizer and Currie, 2014[34])

Parents' health behaviours influence children’s own health behaviours in the early years and throughout the life-cycle. For example, overweight and obesity have a well-documented genetic component, but also depend on the shared lifestyle of family members, particularly nutrition and physical activity. Previous OECD work on adult overweight and obesity trends highlights that one-sixth to one-fourth of the overall variation in the probability of being obese is determined by differences among households rather than differences among individuals. The proportion was higher, up to 50% (similar to what is observed in smoking), for health-related behaviours such as consumption of fruit and vegetables and physical activity, and was about one-third for fat consumption (Sassi et al., 2009[35]).

Genetics alone cannot account for the rise in overweight and obesity in all OECD countries over the past 20 to 30 years. Obesogenic environments appear to encourage individuals, especially when culturally and socially vulnerable, to make less healthy lifestyle choices, and those genetically predisposed tend to become overweight or obese as a result.4 A strong indication emerges that actions targeting individuals outside the social context in which they lead their lives are unlikely to be very effective due to the “social multiplier effect” (Sassi et al., 2009[35]).5

Tackling childhood obesity is a priority for society and the economy as a whole, as obesity from a young age can affect academic performance and educational attainment later in life. OECD analysis shows that healthy-weight 11-15 year-olds are 13% more like to report good performance at school than those who are obese. The strength of this relationship varies across countries and gender: for instance in Belgium and France girls with a healthy weight are 27% more likely to report good school performance than girls with obesity and in Germany and Latvia boys with a health weight are 24% and 23% more likely to report good school performance. Lower life satisfaction and self-esteem, higher propensity to being bullied, and higher school absenteeism are factors (OECD, 2019[36]).

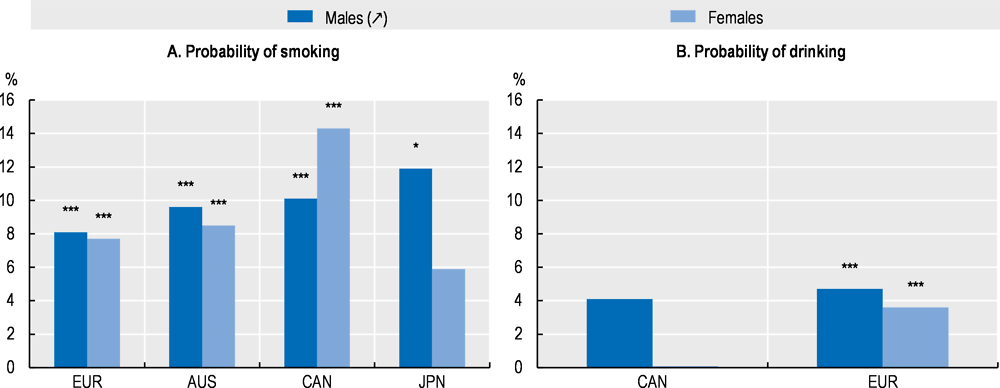

The medical and psychological literatures evidence that children’s smoking and drinking patterns are positively correlated with parental smoking/drinking or parental attitudes towards smoking/drinking (Jayne and Valentine, 2017[37]; Vuolo and Staff, 2013[38]; Mares et al., 2015[39]). The association between the probability of drinking or smoking at age 14 and parental consumption of alcohol or tobacco varies across OECD countries (Figure 3.7). In European countries, regular smoking is 8% higher for both men and women if either parent smoked. For men, parental smoking is the most important predictor, greater than belonging to the lowest wealth quintile. For women, parental smoking has a similar impact on increased smoking probability, as does having a higher education. Not having completed secondary schooling correlates with an increased risk of smoking for women (and for men in Europe and Canada).

In the case of drinking alcohol, parental influence is much smaller (for Canada it is insignificant). For European countries, parental drinking during the childhood years is associated with an almost 5% higher chance of later adult drinking for men and just under 4% for women. Being unemployed is another important driver for men, but not for women. In Europe, unemployment is associated with a 5.5% higher probability of drinking for men (OECD, 2018[40]). As is the case with smoking, in Europe higher education tends to increase the probability of drinking for women, but to a lesser degree than having a parent who drank.

Figure 3.7. Inter-generational health behaviour correlations

Note: Europe refers to 11 countries: Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden and Switzerland. For further details, see Annex table 5.A1.4. ***, *: statistically significant at 1% and 10% levels, respectively.

Source: OECD estimates based on SHARE waves 1 to 5 for the European countries. For Canada estimates based on NLSCY cycles 5 to 8 and children aged 0 to 15 years old. For Australia, estimates based on HILDA wave 9 and 13. For Japan, estimates based on JHPS waves 2009, 2011 and 2012; from OECD (2018), "Intergenerational health behaviour correlations", in A Broken Social Elevator? How to Promote Social Mobility, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264301085-graph84-en.

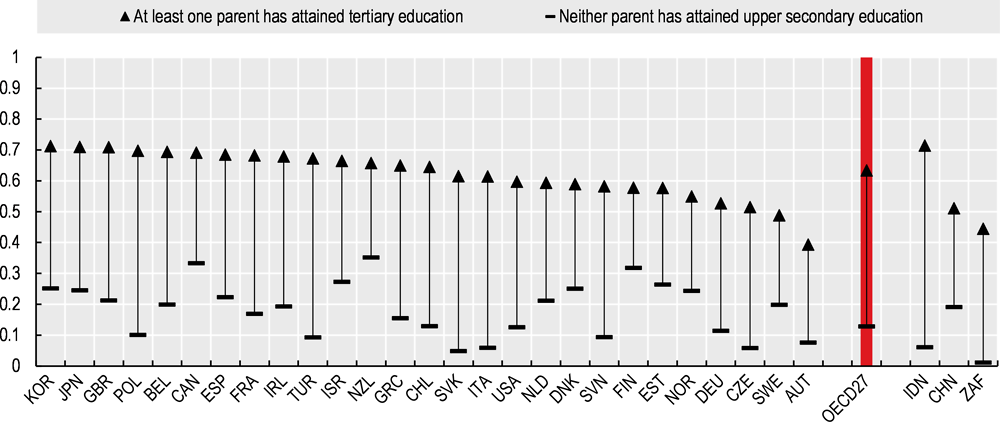

Parents’ level of education

Parents' level of education has a strong influence on the educational achievements of their children. For instance, across the OECD the likelihood of a child attaining tertiary education is over 60% if at least one parent had tertiary education (Figure 3.8). The likelihood of a child attaining the same level of education as parents is 41% in the case of upper secondary education and 42% for below upper secondary. Overall, children from more educated families seem protected from leaving school at lower secondary level or earlier. Such children are six times less likely to drop out at this early stage, compared with students whose parents have a lower educational background (OECD, 2018[40]).

Prospects for upward mobility depend very much on the level of parent’s education. The children of lower educated parents have much more limited chances of achieving tertiary education than peers, indicating the existence of a “sticky floor”. While the children of parents without upper secondary education have only a 13% chance of attaining tertiary education, they would have been four times more likely to go to university if at least one parent had attained tertiary education (OECD, 2018[40]). “Sticky floors” are observable in most countries where data is available.

There are wide differences across countries in the educational attainment of children with the same parental background. For example, in Italy and Turkey a child whose parents has not attained upper secondary will be ten times more likely to have the same outcome than to reach tertiary education. In Canada, similar children are more likely to attain tertiary education than remain at the same level as their parents.

Figure 3.8. Likelihood of achieving tertiary education, by educational attainment of parents, 2015

Source: OECD calculations using PIAAC 2012 and 2015, based on LIS for China, IFLS for Indonesia and NIDS for South Africa; from OECD (2018), "Sticky floor at the bottom and sticky ceiling at the top", in A Broken Social Elevator? How to Promote Social Mobility, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264301085-graph88-en.

Parents' levels of education and income help children succeed, regardless of their abilities and skills. A study from the United Kingdom found that affluent parents hoard opportunities for their children to succeed in education and later in their careers. Children from low-income families and of less skilled parents might have scored well at IQ tests at age 5, but their outcomes at age 42 years shows that they were much less successful at converting their high potential into career success (higher earnings and top job status). By contrast, children from wealthier families and of highly-educated parents who scored poorly on IQ tests at five years of age were more likely to perform better at age ten, and later to have more career success than would have been expected (McKnight, 2015[41]).

Affluent children benefit from many opportunities to overcome shortcomings: higher parental education; easier access to high quality education (private grammar and secondary schools); more parental and educational support to get into university. Families with greater means at their disposal, financial and otherwise, assist their children in accumulating skills, particularly those that are highly valued in the labour market.

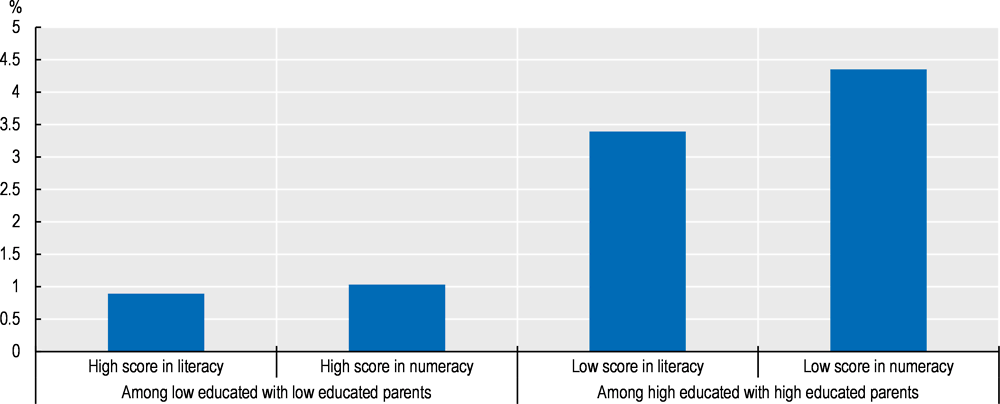

Results from the OECD’s Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) survey highlight similar trends across OECD countries as a whole (Figure 3.9). On average, individuals of highly educated parents have better skills scores than those whose parents have low educational achievement; 25% of adults whose parents had less than upper secondary education achieve the lowest literacy scores, whereas only 5% of those whose parents had achieved tertiary education did. The impact of parental education on test scores is more marked for numeracy; 30% of those at the bottom numeracy scores have a parent with low education. At the same time, those from advantaged family backgrounds are found to be more likely to be highly educated than the cognitive skill assessments would suggest. About 4.5% of individuals with low numeracy test scores and 3.5% with low literacy test scores attained tertiary education like their parents confirming that children in affluent households receive multiple advantages that help them secure a high education and income later in life.

Figure 3.9. Percentage of individuals attaining tertiary education, by PIACC scores and parental education, OECD average, 2015

Source: OECD (2018), "Percent of individuals attaining tertiary education, by PIAAC scores and parental education", in A Broken Social Elevator? How to Promote Social Mobility, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264301085-graph90-en.

Parental level of digital literacy informs the digital mediation strategy adopted to children’s use of digital media. Parents who are relatively digitally skilled are more likely to adopt an enabling mediation approach to maximise children’s online opportunities, while parents who are lower digital skilled parents are more likely to employ a restrictive mediation approach to keep children safe. The PIACC survey shows that in OECD countries only 31% of adults have adequate problem-solving skills (levels 2 and 3) for technology‑rich environments. Enabling mediation reflects favourable parental judgement of children’s digital skills and understanding of risk. Research suggests that enabling mediation is associated with more child-initiated requests for support minimising – or avoiding – the likelihood of encountering harm online. Restrictive mediation is preferable when parents or children have lower digital skills as it is associated with fewer online risks, but at the cost of opportunities (Livingstone et al., 2017[42]). Furthermore, being vulnerable offline can translate into exposure to more risks and harms online that have a greater impact. Online safety education needs to be more nuanced to particular risks across different age groups. Reducing offline risks has the potential of reducing online risks (El Asam and Katz, 2018[43]).

Exposure to intimate partner violence

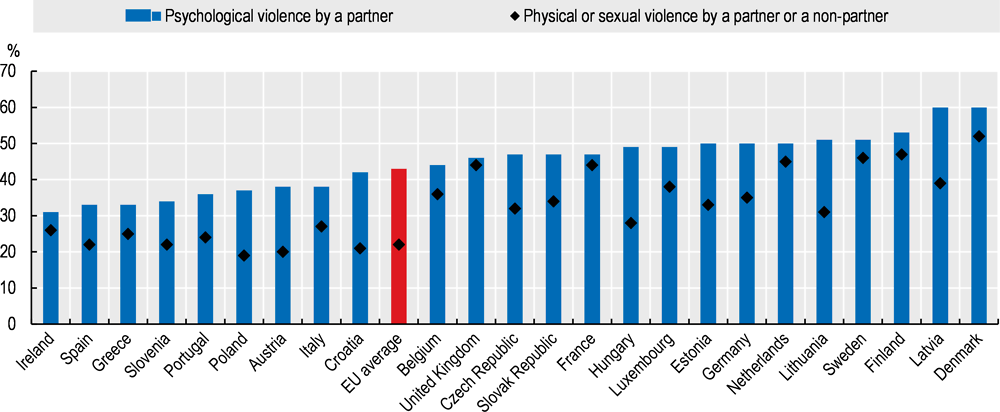

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is increasingly recognised as a serious problem in OECD countries. IPV is not gender neutral: in the majority of cases, victims are women who are also mothers. Globally, 30% of women report physical and/or sexual violence by their current or previous partner (WHO, 2013[44]). At the European Union level, 22% of women report physical and/or sexual assault by their current or previous partner, and 43% disclosed psychological abuse including intimidation, belittling and restriction of freedom (Figure 3.10) (FRA, 2014[45]).6 Results of the 2016 OECD Gender Equality Questionnaire highlight that violence against women is one of the key gender equality issues for urgent action in OECD member countries.

Figure 3.10. Percentage of women reporting psychological abuse and physical and/or sexual violence by current or previous partner, since the age of 15, 2012

Source: FRA - European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (2012), "Physical, sexual and psychological violence", Survey on Violence Against Women in EU (2012), https://fra.europa.eu/en/publications-and-resources/data-and-maps/survey-data-explorer-violence-against-women-survey.

Although there is no OECD-wide data available, national surveys on children’s exposure to violence and self-reports by parents indicate that significant numbers of children are exposed to IPV, either through current or previous parental relationships. In the United States, the National Survey of Children’s Exposure to Violence II recorded that 17% of children were direct witnesses to a parent assaulting another parent or parental partner. The lifetime exposure rate is 28%, if only responses of 14-17 years olds are regarded (Finkelhor et al., 2015[46]). In Sweden, 14% of 14-17 year olds report witnessing IPV (Jernbro and Janson, 2017[47]). Self-reports by parents, primarily mothers, point to the majority of children in households with IPV being directly exposed to violence: Australia at least 50% (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare., 2018[48]); France 84% (Thélot, 2016[49]); and Spain 64% (Delegación del Gobierno para la Violencia de Género, 2015[50]). Furthermore, households with IPV are twice as likely to contain children, particularly children under years of age (Fantuzzo and Mohr, 1999[51]). At the European Union level, 73% of women reporting IPV are caregivers of children who also witness the abuse (FRA, 2014[45]). In New Zealand, children are present about half of the time when police respond to incidents of IPV (Murphy et al., 2013[52]).

IPV in the home undermines developing children’s need have for safety and predictability in their surroundings. In general, IPV is an episodic experience, though sometimes mothers exit and re-enter violent relationships. Children are often the direct witnesses of violent physical and sexual assault, and psychological abuse, even if they are not directly harmed by it (Jasinski and Williams, 1998[53]). Children are observers to the aftermath of violent incidents, including signs of physical injuries, parental distress and the destruction of personal property (Swanston, Bowyer and Vetere, 2014[54]). Furthermore, as children become older, the likelihood of them intervening to protect a parent increases (Hester, Pearson and Harwin, 2007[55]).

Overall, research indicates that childhood exposure to IPV significantly influences child well-being at different developmental stages across an array dimensions and indicators: being overweight or obese (Jun et al., 2012[56]); childhood depression and aggressive behaviours (Johnsona et al., 2002[57]); conduct disorders (Meltzer et al., 2009[58]); poorer school performance (Akter and Chindarkar, 2019[59]; Kiesel, Piescher and Edleson, 2016[60]); and bullying and victimisation behaviours (Knous-Westfall et al., 2012[61]). Also notable is the strong co-occurrence in households of IPV and child maltreatment (Hamby et al., 2010[62]).

The timing and duration of exposure to IPV is relevant to understanding the impact on children’s well-being and development. Children can be exposed to IPV from very early on into their lives. While the research has not concluded if pregnancy is a risk factor for IPV, expectant mothers with demographic characteristics such as young maternal age, low socio-economic status, minority status and being unmarried, are at elevated risk. For children, IPV during pregnancy is associated and with low birth weight and pre-term delivery, even after controlling for background and other relevant factors (Bailey, 2010[63]), and poorer mother-infant attachment in the early years (Levendosky et al., 2011[64]).

Early childhood exposure to IPV can have long-term consequences on children’s social and emotional development (Schnurr and Lohman, 2013[65]; Levendosky et al., 2011[64]). As an age cohort, young children are the most exposed to IPV, as most of their time is spent in the direct home environment. In addition, young children are particularly susceptible to the stress of IPV due to the rapid pace of early brain development and their underdeveloped coping skills. IPV is associated with the establishment of insecure infant-parent attachment. However, IPV can also later disrupt parent-child attachments that were of a high quality. Young children exposed to IPV are more likely to have internalised and externalised behavioural problems, lower verbal skills, poor physical health, and difficulties in forming peer relationships. These difficulties are likely to follow young children into their schooling. IPV affects the quality of parenting and the ability of both parents to meet children’s needs (Pels, van Rooij and Distelbrink, 2015[66]; Guille, 2004[67]).

Parenting in the context of IPV is demanding. It is associated with the primary caregiver or protective parent employing restrictive parenting practices and harsher disciplinary methods to prevent rising tensions. IPV usually goes hand-in-hand with the absence of supportive co-parenting practices. Fathers who perpetrate IPV are less likely to be involved in children’s day-to-day care and also serve as poor role models for relationship modelling and conflict resolutions. Furthermore, families experiencing IPV tend to be more socially isolated and have smaller informal support networks.

The scope of these difficulties underlines the seriousness of IPV for children and the need for interventions to promote children’s well-being. In some OECD countries, exposure to IPV is considered a form of child maltreatment (Nixon et al., 2007[68]).This implies an expectation on child protection services (CPS) to intervene to assess the risk of harm. However, research suggests that the response from CPS to these set of risks can vary greatly, sometimes placing children at elevated risk of harm and other times overlooking opportunities to positively intervene (Nixon et al., 2007[68]). Often CPS are satisfied to close IPV referrals on the undertaking from the protective parent that children will not be directly exposed to further violent incidents. A study by (Kiesel, Piescher and Edleson, 2016[60]) highlights that children exposed to only IPV can fare worse across educational outcomes than children exposed to maltreatment, or to co-occurring IPV and maltreatment. The disparity in outcomes may be attributable, in part, to these children not consistently receiving an intervention of any kind to promote their well-being. Children living in households with IPV benefit not only from the risk of exposure to IPV being reduced and/or eliminated, but also from interventions to strengthen parent-child relationships.

Family stress

The co-occurring factors that contribute to child vulnerability – e.g. low household income, persistent material deprivation, poor work-family life balance, poor parental mental health, parental substance misuse, intimate partner violence, unsafe neighbourhoods and social isolation – also generate chronic family stress, which in itself has an impact on child development and well-being.

Research on children’s developing biological systems suggests that chronic family stress, particularly in early childhood, can have immediate and long-term impacts on healthy development (National Center on the Developing Child, 2016[69]; Thompson, 2014[70]; Hostinar and Gunnar, 2013[71]). Chronic family stress from low household income or economic hardships is associated with increased internalised and externalised problems in early childhood and adolescence, poorer child physical health and lower preschool literacy, as well as inconsistent and harsher parenting practices (Masarik and Conger, 2017[72]). Parents with good problem‑solving skills and strong support networks are more likely to use positive parenting practices.

Childhood exposure to chronic family stress can reinforce the link between parental mental illness and child and adolescent mental health difficulties. A study by (Plass-Christl et al., 2017[73]) used data from the German National Health Interview and Examination Survey to examine the link between poor parental mental health, child and adolescent mental health difficulties and chronic stress. The study highlighted that although poor parental mental health is a risk factor, exposure to two or more stressful events is more significant. Events considered stressful included a recent bereavement, recent parental separation or divorce, financial stress, and accident or severe illness affecting the child.

Children’s stress responses reflect individual traits, the risks and protective factors in the family and community environments. Children with timid dispositions are more likely to develop anxiety or depression than those who are more self-assured. Parents and other supportive adults play a fundamental role by providing reassurance and buffering stress. They assist children in developing capabilities to deal with stress. However, parents themselves are often overwhelmed by the same set of stressors, and in some cases are the source of stress when substance misuse and poor mental health makes their behaviour inconsistent, insensitive, or aggressive.

Good stress helps children master healthy stress responses, including positive coping skills and self‑regulation. Bad stress, on the other hand, is severe, chronic and unpredictable (Box 3.1). Although children’s stress responses vary, in almost all case too much bad stress causes health and developmental problems.

In early childhood, the foundations of executive function, self-regulation, and mental and physical health are laid down. In summary, chronic stress contributes to the following disruptions:

Weakens the foundation of the brain architecture. Early experiences – positive and negative –determine which neural circuits are reinforced and which are pruned (National Center on the Developing Child, 2016[69]),

Causes epigenetic adaptions. Gene expression is influenced by positive and negative life experiences and environmental toxins. Highly stressful early experiences can authorise genetic instructions that disrupt the development of the systems that manage responses to stressful life situations. These epigenetic changes can be short-term or enduring, and can be passed onto future generations (National Center on the Developing Child, 2016[69]; Thompson, 2014[70]),

Disrupts the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical (HPA). The sensitivity of the HPA axis, a regulatory stress-response system integrating the nervous and endocrines systems, can be disrupted by chronic stress with long-term cognitive, and social and emotional consequences (Ballard et al., 2015[74]; Thompson, 2014[70]),

Compromises the immune system. Toxic stress undermines immune system functioning by reducing the ability to fight infections and embedding pro-inflammatory tendencies (Thompson, 2014[70]).

Children’s capabilities continue to develop into adolescence and early adulthood. Nevertheless, it is easier and more effective to help vulnerable children if strong foundations have been laid. Policy makers should promote policies that reduce family and community level stress and strengthen vulnerable children’s ability to cope with adversity and threats (National Center on the Developing Child, 2016[69]).

Box 3.1. Three Types of Stress Responses

The National Scientific Council on the Developing Child (2016) distinguishes among three different types of stress responses: positive, tolerable and toxic.

Positive stress response is a normal and essential part of healthy development, characterised by brief increases in heart rate and blood pressure, and mild or brief elevations in stress hormone levels. Situations that might trigger a positive stress response are a child’s first day with a new caregiver or receiving an injection at the doctor’s office.

Tolerable stress response activates the body’s alert systems to a greater degree as a result of a more severe or longer-lasting threat, such as the loss of a loved one, a natural disaster or a frightening injury. If the activation is time-limited and buffered by relationships with supportive adults who help the child adapt, the brain and other organs recover from what might otherwise be damaging effects.

Toxic stress response can occur when a child experiences major, frequent, and/or prolonged adversity –such as recurrent physical or emotional abuse, chronic neglect, caregiver substance abuse or mental illness, repeated exposure to violence, and/or the accumulated burdens of family economic hardship – without adequate adult support, or worse, when the adult is the source of both support and fear. Excessive and/or prolonged activation of the stress response systems can disrupt the development of brain architecture and other developing organs. This cumulative toll increases the risk for stress-related disease and cognitive impairment, including heart disease, diabetes, substance abuse, and depression, well into the adult years. Research also indicates that supportive, responsive relationships with caring adults as early in life as possible can prevent or reverse the damaging effects of a toxic stress response.

Source: National Scientific Council on the Developing Child (2016)

Community Factors

Schools

Early Childhood Care and Education (ECEC)

Access to early learning has considerable positive implications for the well-being of individuals and for societies as a whole. Evidence shows that early learning has a positive impact on the educational attainment of children later in life, but also on a wide range of other characteristics such as physical and mental health. The brain develops faster and has a higher plasticity during early childhood than at any other point in life; children are therefore particularly responsive to the interactions they experience over this period (Meltzoff and Kuhl, 2016[75]). The benefits of early learning go well beyond academic achievement.

Early intervention makes it easier for children to acquire knowledge and skills in the future (OECD, 2015[76]). For instance, children’s ability to comply with demands from adults will shape their relationships with caregivers, which can in turn influence opportunities for developing cognitive skills, such the ability to engage in language-rich exchanges.

PISA 2015 shows that, on average across OECD countries, 15 year-old students who attended early childhood education and care (ECEC) for two years or more score a significant 26 score-points higher on the PISA test assessing sciences performance than their counterparts who attended ECEC for less than two years (Figure 3.11). The significant difference in sciences performance according to the duration of attendance in ECEC remains after controlling for the socioeconomic profile of students and schools, as 15-year-old students who attended ECEC for two years or more still score 15 score-points higher than their peers who attended ECEC for a shorter duration. This suggests that the beneficial effects of attending early childhood settings on academic results are valid for all children.

Figure 3.11. The beneficial effects of ECEC attendance on science performance (PISA 2015)

Note: Score-point differences that are statistically significant are marked in a darker tone. Countries and economies are ranked in descending order of the score-point difference in science performance between 15-year-olds who reported that they had attended early childhood education (ISCED 0) for two years or more and others, after accounting for socio-economic status.

Source: OECD (2017), "Graph 5.3 - Score-point difference in science performance between 15-year-old students who attended early childhood education (ISCED 0) for two years or more and those who attended for less than two years (PISA 2015)", in Starting Strong 2017: Key OECD Indicators on Early Childhood Education and Care, Starting Strong, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264276116-graph41-en.

The positive outcomes of early learning extend beyond the scope of school and academic achievement. The early learning environment provides opportunities to ensure that children understand the importance of good nutrition and physical activities, and that they can familiarise themselves with both. Studies show that target interventions on the youngest can be effective in changing behaviours, and decrease the odds of issues such as being overweight during adolescence (Sassi, 2010[77]; OECD, 2011[78]).Early childhood education also provides children with opportunities to master self-regulation. Children who develop good self-regulation during childhood achieve higher income and socioeconomic status in their 30s, and are less likely to develop substance dependence or to be convicted of a crime (Moffitt et al., 2011[79]). They are also comparatively less likely to live in social housing or have poor health by age 42 (Shuey and Kankaraš, 2018[80]).

The positive effects of early learning are particularly strong for vulnerable children. For instance, a number of correlational studies suggest that children from lower socioeconomic status families experience particular benefits in the areas of cognitive and social skills development compared to peers from higher socioeconomic backgrounds (Sylva et al., 2014[81]; Burger, 2010[82]). The benefits of ECEC for this group of children can in fact be stronger and may not fade over time (van Huizen and Plantenga, 2018[83]).The positive effect for children from minority backgrounds is more mixed, however (Ladd, 2017[84]).

The wide benefits that early learning produces for individuals, governments and societies translate in the fact that investments at this stage of children’s education generates high returns. Estimates suggest that economic returns of investment in early learning, including higher income, better health and lower crime, are between 2% and 13% (García et al., 2016[85]; Karoly, 2016[86]), and that they are comparable for investments in emotional and cognitive domains (Paull and Xu, 2017[87]). These high rates of return in early learning justify public investments in this field.

Despite early learning benefiting children from vulnerable backgrounds the most, concerning inequities of access to ECEC persist. These differences arise, at least in part, because in many countries ECEC programmes incur fees that higher-income families are more able to afford. Higher income families also tend to provide more stimulating and responsive interactions in the home environment (Burchinal et al., 2015[88]; Sylva et al., 2004[89]).

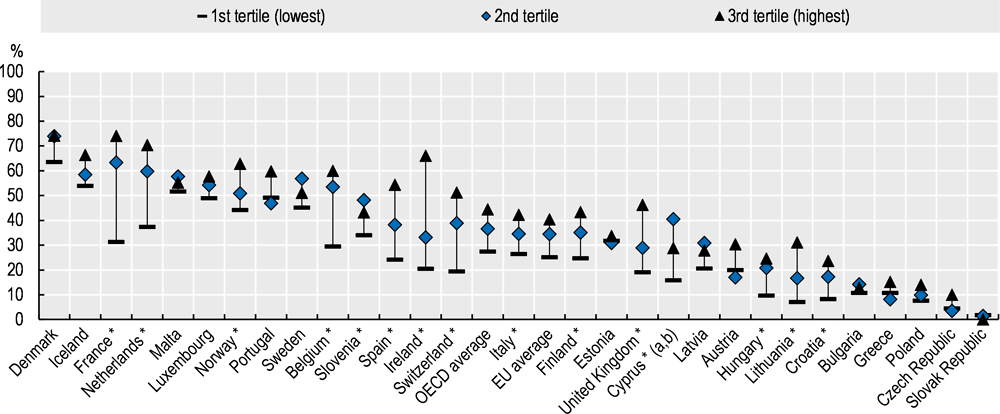

On average, just over one-third of children under three years old participate in formal ECEC. This percentage varies widely across countries, from almost 3% in Mexico to as high as 62% in Denmark. In addition, in many countries the ECEC participation of children from low-income households is significantly lower, up to half (Figure 3.12). Evidence from Germany suggests however that participation in ECEC can influence parents to engage more frequently in cognitively stimulating and less passive activities with their children, helping to close the gap between disadvantaged children and children from non-disadvantaged families (Felfe and Lalive, 2010[90]).

Figure 3.12. Children’s participation in formal education and care services is substantially lower for low-income families

Note: Data for Switzerland and Malta refer to 2014, and for Iceland to 2015. Data are OECD estimates based on information from EU-SILC. Data refer to children using centre-based services (e.g. nurseries or day care centres and pre-schools, both public and private), organised family day care, and care services provided by (paid) professional childminders, regardless of whether or not the service is registered or ISCED-recognised. Equivalised disposable income tertiles are calculated using the disposable (post tax and transfer) income of the household in which the child lives – equivalised using the square root scale, to account for the effect of family size on the household’s standard of living – and are based on the equivalised disposable incomes of children aged less than or equal to 12. In countries marked with an *, differences across groups are statistically significant at p<0.05.

Source: OECD (2018), “PF3.2: Enrolment in childcare and pre-school”, OECD Family database, Indicator 3. Public policies for families and children (PF), www.oecd.org/els/family/database.htm.

Participation in ECEC may also be particularly beneficial for children from families where the language spoken at home is different from the language of schooling (Burchinal et al., 2015[88]), or in families from immigrant backgrounds. PISA results show that the gains in science proficiency at age 3 versus age 5 are greater for children from immigrant families than with children of non-immigrants. In countries where the proportion of 15-year-old students with an immigrant background (first and second generation) is above 6%, immigrant students who reported that they attended ECEC for at least one year scored 36 score‑points higher in the PISA science assessment than those who attended ECEC for less than a year or not at all. When accounting for student’s socioeconomic status, the difference in PISA scores of students with an immigrant background and different lengths of enrolment in ECEC is still significant at 25 score-points (i.e. 10 months of formal schooling) (OECD, 2017[91]). The benefits of ECEC for children who speak a different language at home or come from immigrant backgrounds are broadly related to language and integration, which are beneficial for children irrespective of the socio-economic status of their families.

Although research suggests that vulnerable children benefit more from early learning, participation in ECEC does not necessarily close the gap in later outcomes between children from low and high socioeconomic status (Schoon, Cheng and Jones, 2013[92]). Results from PISA notably underscore the importance of accounting for children’s family and home environment to understand potential implications of ECEC attendance, meaning that the positive effects associated with ECEC attendance are partly dependent on families’ socio-economic status (OECD, 2017[91]).

Primary and secondary school

Disadvantaged students usually have to overcome specific obstacles if they are to succeed in their education and later on in their careers. 7 These obstacles include not benefiting from the same parental support as students of more educated parents or attending a disadvantaged school with fewer financial resources and well-qualified teachers. Achieving equity in education would mean that students of different socio-economic status, gender and family backgrounds attain similar levels of academic performance in key cognitive domains, for example reading, mathematics and science, and similar levels of social and emotional well-being during their school years. However, results from PISA 2015 show that disadvantaged students perform worse than advantaged students across all of these dimensions.

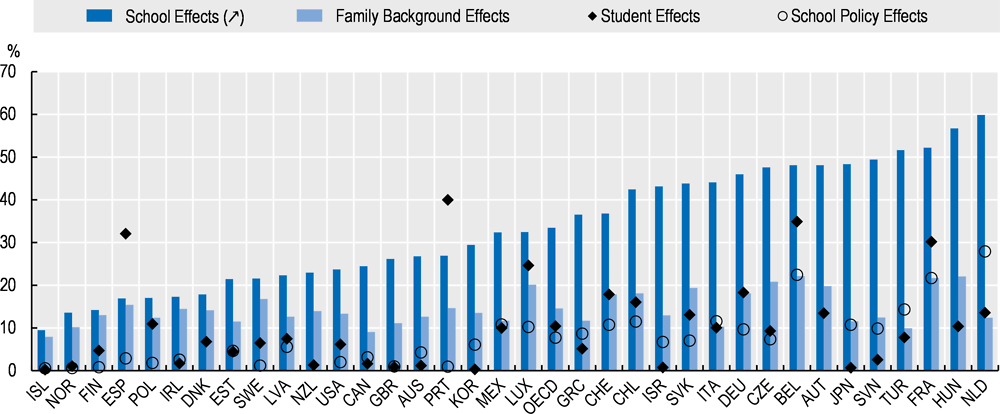

Schools play a role in reducing or accentuating the impact of family background and individual characteristics on children’s educational outcomes. Based on PISA 2015, school effects, which reflects the impact of going to different schools, are the most important explanatory factor in the variation of student test scores in mathematics in 21 of 35 OECD countries. On average, across OECD countries, school effects explain 33% of the variation while students’ family background explains 14% and students’ own characteristics (gender, age and grade) 11% and school policy effects 8% (Figure 3.13). Similar results are observed in other PISA assessment domains. There are some exceptions for example Spain and Portugal where student and family effects are much stronger predictors of variations in PISA test scores. School effects tend to be strongest in countries that have early tracking, for example Germany and the Netherlands but it is also high in countries where there is no early tracking (OECD, 2018[40]).

Figure 3.13. Variance decomposition of PISA mathematic tests scores, aged 15 years

Note: This represents the share of PISA mathematics test score variation explained following a regression of test scores as a function of family background, student-level and school-level controls. Student effects refer to gender, age and grade. Family background refers to the PISA ESCS, immigration status, language spoken at home, whether living with two parents. School effects represent specific dummy for each school. School policy refers to the quality of Educational Resources, creative extracurricular Activities, Student/Teacher Ratio and Index of ability grouping between mathematics classes.

Source: OECD (2018), "Variance decomposition of test scores", in A Broken Social Elevator? How to Promote Social Mobility, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264301085-graph94-en.

There are two pathways by which students’ PISA test scores vary by the school that they attend. The first is through the sorting of students of similar ability or background into the same schools due to national policies on academic tracking, school admission policies and parent/student or teacher behaviour. The second is through school-level educational policies that affect student achievement with “good schools” raising the test scores more than “poor schools” (OECD, 2018[40]). On average, across the OECD, 48% of disadvantaged students attend disadvantaged schools.8 In some OECD countries, there is a concentration of disadvantaged students in schools without high achieving students (defined in PISA as students who score higher than the top quartile of performance), for example Chile, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Mexico and Slovenia. However, in some countries disadvantaged students are evenly distributed across schools, including in schools enrolling high-achieving students, for example Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Ireland, Norway and Sweden. In all countries, however, there is a clear advantage in attending a school where students, on average, come from more advantaged backgrounds (Causa and Chapuis, 2010[93]).

Student performance is strongly associated with student socio-economic status. PISA consistently finds that disadvantaged students perform worse than advantaged, although the strength of this relationship varies across countries. On average across the OECD, a one-unit change in the family wealth index represents a 10 point increase in a student’s science score, before accounting for parents’ education, and an increase of 4 points after accounting for parents’ education. Similarly, students in high-income families perform better at science than students in low-income families (OECD, 2017[94]). Furthermore, OECD analysis shows a strong relationship between the variation in science performance related to family wealth and the overall income inequality in countries measured by the GINI index. This association suggest that the inequalities observed more broadly in a country are reflected in student performance. In other words, in all countries, affluent parents may use their wealth to provide a better education for children and in more in equal societies these advantages can be greater (OECD, 2017[94]).

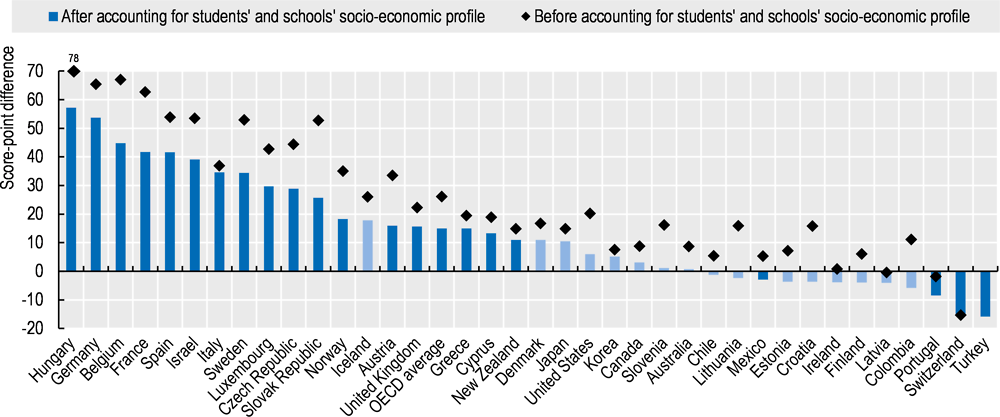

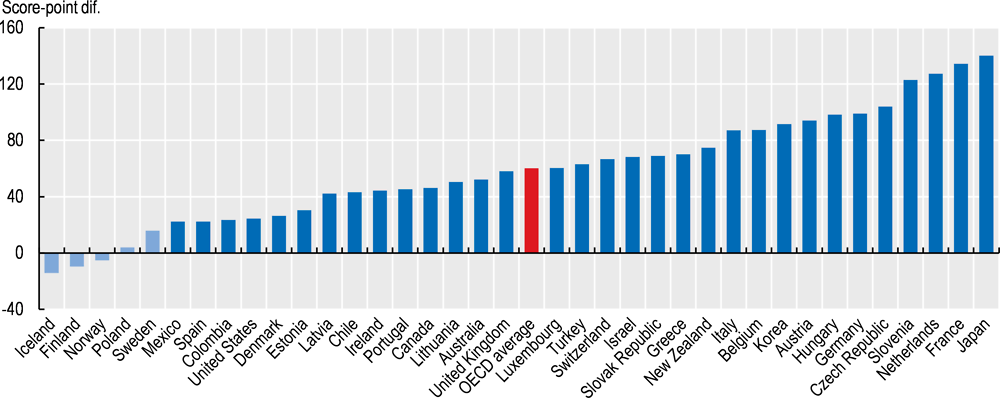

Student performance is also strongly associated with the school socio-economic profile defined as the average socio-economic status of enrolled students (Figure 3.14). School socio-economic profile is shaped by social segregation and the sorting of students across schools. Sorting can result in academic segregation of students by placing higher preforming students into a limited number of schools or by designating the lowest achieving students to disadvantaged schools. The sorting of students through early tracking and ability grouping are often very costly and ineffective at raising educational outcomes, particularly for disadvantaged students. Furthermore, disadvantaged students are much more likely than advantaged students to be sorted into non-academic tracks. On average, across disadvantaged students in OECD countries, a one-unit increase in school socio-economic profile is associated with a 60 score‑point improvement in student performance, even after accounting for student socio-economic status. In the Czech Republic, France, Japan, the Netherlands and Slovenia, each additional unit of school-level socio‑economic status is associated with a more than 100 score-point improvement in performance among disadvantaged students (OECD, 2018[95]).

Figure 3.14. Change in disadvantaged student performance associated with school socio‑economic profile

Note: Statistically significant score-point differences are shown in a darker tone.

Countries and economies are ranked in ascending order of the change in performance associated with school socio-economic profile.

Source: OECD (2018), "Change in student performance associated with school socio-economic profile: Score-point difference in science among disadvantaged students associated with a one-unit increase in school socio-economic profile, after accounting for student socio-economic status", in Equity in Education: Breaking Down Barriers to Social Mobility, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264073234-graph33-en.

Attending the same schools as advantaged students may help raise disadvantaged students’ aspirations and self-expectations. Students’ aspirations for further education and their career later on are shaped by family wealth, social status and neighbourhood characteristics (Stewart, Stewart and Simons, 2007[96]). On average across OECD countries, 29% of children of blue collar workers9 and 55% of the children of white collar workers10 report that they expect to complete a university education. Children of blue collar workers were much less likely to expect to work as managers or professionals than children of white collar workers, with an average difference of 21 percentage points across OECD countries. However, children of blue‑collar workers who attend schools where students have parents with white-collar occupations were around twice as likely to expect to earn a university degree and work in a management or professional occupation than children of blue-collar workers who perform similarly but who attend other schools. In other words, the education and occupation expectations of disadvantaged students are related to the socio‑economic profile and composition of their school (OECD, 2017[94]).

The clustering of poor students in poor schools might dampen students’ expectations and beliefs in themselves. Disadvantaged students are less likely to develop high motivation and aspirations for themselves when they are around students with similarly low motivation and aspirations. Yet on the other hand, being in a school with a diverse student body can make a student at the bottom of the socio-economic hierarchy feel less satisfied with their life than those from a more advantaged background. PISA 2015 data show that there are large differences across countries in the strength of the relationship between socioeconomic advantage and students’ well-being outcomes, suggesting that policies and school practices can help level (OECD, 2017[94]).

Neighbourhoods

Neighbourhoods affect the social, cultural, and demographic conditions that contribute to child well-being. A growing body of research argues that neighbourhoods have a causal effect on child and later adult outcomes, distinct from family factors (Chetty and Hendren, 2018[97]; Deutscher, 2018[98]). Neighbourhoods vary in the opportunities available for children to do well; some have supportive mechanisms in place that enhance child development, while others have too many stressors and not enough protective factors. Neighbourhoods increase the difficulties experienced by families through concentrated poverty11, social isolation (particularly from mainstream institutions), and joblessness (Wilson, 2013[99]).

Several non-experimental studies have linked poor child and adolescent outcomes to the neighbourhood level. These include externalised behavioural problems and lower cognitive abilities (Donnelly et al., 2017[100]); anti-social behaviours (Odgers et al., 2012[101]); risky sexual behaviours (Leventhal, Dupéré and Brooks-Gunn, 2009[102]); higher incarceration and teenage births rates (Chetty et al., 2018[103]); and lower adult earnings, college enrolment and marriage rates (Chetty and Hendren, 2018[97]). Moreover, growing up in a toxic environment (i.e. neighbourhoods with concentrations of violence, incarcerations and lead exposure) independently predicted poorer adult outcomes for low-income children, after accounting for demographic factors.12 However, the associated neighbourhood effects are different by race and gender: lower social mobility among white children; adult incarceration and lower income rank relative to parents’ earnings among black boys; and teenage births among black girls (Manduca and Sampson, 2019[104]).

In OECD countries, there is evidence that income inequality has taken on clear spatial dimensions. In urban areas, affluent and low-income households often live in clearly separate neighbourhoods. Neighbourhoods in European cities are, on average, less spatially segregated by income than those in North America. Nonetheless, patterns in spatial segregation differ across countries. In Denmark and the Netherlands, on average lower income households experience the highest levels of segregation, whereas in Canada, France and the United States the most affluent households concentrate in specific areas of cities (OECD, 2016[105]).

Research on neighbourhood effects within OECD countries has been mainly based on the United States and to a lesser extent Australia, Denmark and Germany. Evidence of neighbourhood effects are strongest in the United States and Australia and weaker in Denmark and Germany. In the United States, the Moving to Opportunity (MTO) experiment randomly assigned housing vouchers to low-income families; some on the condition of families moving to lower-poverty neighbourhood. Over the long run, MTO has shown that the integration low-income families into mixed-income neighbourhoods can help reduce persistent poverty and increase inter-generational mobility. Moving to a low-poverty neighbourhood during childhood (below the age of 13) had a positive effect on inter-generational mobility, but gains fell with age underlining that the longer exposure to a better environment the more improved adult outcomes are. The disruption of moving neighbourhood after age 13 may even have a negative effect on adult outcomes (Chetty et al., 2016[106]). In Australia, the opposite effect was shown on moves undertaken during adolescences; one year in a better environment is more valuable in adolescence than in early childhood because of the long-lasting peer effects and the probability as a young worker of entering the local labour market (Deutscher, 2018[98]). In Denmark, the neighbourhood effect on adult earnings becomes negligible after the age of 30 when family background becomes more relevant (Eriksen, 2018[107]; Bingley, Cappellari and Tatsiramos, 2016[108]). In Germany, centralised institutional services might cushion the neighbourhood effect and allow more even of access to resources for support across different neighbourhoods (Howell, 2019[109]).

Recent studies have gone a step further by evidencing that for low-income children neighbourhoods can be high-opportunity or low-opportunity places to grow up in (Chetty and Hendren, 2018[110]) (Donnelly et al., 2017[100]).High-opportunity neighbourhoods influence the chances for low-income children’s inter-generational mobility by transmitting advantages that favour human capital development. Broadly speaking, high-opportunity neighbourhoods have better preforming schools, lower levels of income inequality, more adults in employment, lower spatial segregation and crime, and a greater share of two-parent households. These neighbourhoods have higher social capital13 and collective efficacy14, better institutional resources and fewer physical hazards.

Low-income parents in high-opportunity neighbourhoods allocate more time to the care of children and to engaging with institutions. A study by (Wikle, 2018[111]) examined the breakdown of low-income parents’ time, controlling for education, employment, race and gender. Low-income parents in high-opportunity neighbourhoods spend more time with children, in particular on developmental care, and spend less time alone. Furthermore, parents in high-opportunity neighbourhoods access government services at a higher rate. This suggests that adult public programmes have positive spillover effects for parenting, indicating that investing in adults in low-opportunity neighbourhoods, including in unemployment services and parenting programmes, benefits children.

The high collective efficacy of high-opportunity neighbourhoods mediates the impact of limited neighbourhood resources, poor social organisation and low density of social ties on rates of neighbourhood violence and individual well-being (Sampson, 2012[112]). High collective efficacy represents stronger social cohesion and a shared willingness to intervene for the common good. Neighbourhoods with high collective efficacy have less crime- now and holding true into the future-, a greater number healthy birth weights, lower infant mortality and fewer teenage pregnancies. This suggests a link between overall health and community well-being that is independent from social composition (Sampson, 2012[112]).

High collective efficacy may be a more valuable resource for vulnerable children. A study by (Odgers et al., 2009[113]) found that at age five, collective efficacy can act as a protective factor against anti-social behaviour i.e. delinquent and aggressive behaviours. Moreover, high collective efficacy also reduces incidence of child maltreatment. Research suggests that it can reduce reports of substantiated of child physical abuse, sexual abuse and neglect to child protection services, controlling for background factors (Molnar et al., 2016[114]).

Several studies have looked at the benefits of moving to a high-opportunity neighbourhoods by measuring the gains for child development and later adult outcomes. The most extensive work measuring has been undertaken by Chetty and colleagues, most notably the Opportunity Atlas (Box 3.2). This work points to positive place exposure effects that are cumulative and linear; there is no point in childhood in which the positive returns from moving to a high-opportunity neighbourhood become negligible. Another study by (Donnelly et al., 2017[100]) focusing on early childhood and middle childhood only capture gains in children’s cognitive skills that are associated with access to high-quality schools. For children’s socio-emotional skills, the benefits of high-opportunity neighbourhoods appear by age three years and neither grow nor decline over time.

Box 3.2. The Opportunity Atlas: Mapping the Roots of Childhood Social Mobility

Where should families seeking to improve their children’s outcomes live? This is one of the questions that Raj Chetty and colleagues set out to answer when they developed the Opportunity Atlas, a United States wide database linking children’s outcomes in adulthood back to the neighbourhood in which they grew up.

The Opportunity Atlas shows that neighbourhoods influence social mobility at a very granular level, down to a few block radius. Places that produced good outcomes for children in the past generally continue to do so, even a decade later. Moving to a high-opportunity neighbourhood earlier in childhood is associated with higher lifetime earnings on average of USD $200,000, and lower likelihood of incarceration and teenage births. However, an important take away is that neighbourhoods produce good outcomes for one sub-set of children and may not replicate the same success for others i.e. across racial groups and genders.

The Opportunity Atlas reveals that historical data on children’s outcomes is a powerful indicator of children’s chances of upward social mobility. Families should look at moving to areas that are opportunity bargains: affordable neighbourhoods that produce good outcomes for children. Policymakers should support families in making this move, but also target policies in low-opportunity areas at particular sub-sets of children who fare the worst.

Source: Chetty et al (2018) The Opportunity Atlas: Mapping the Childhood Roots of Social Mobility

References

[34] Aizer, A. and J. Currie (2014), “The intergenerational transmission of inequality: Maternal disadvantage and health at birth”, Science, Vol. 344/6186, pp. 856-861, http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1251872.

[59] Akter, S. and N. Chindarkar (2019), “The link between mothers’ vulnerability to intimate partner violence and Children’s human capital”, Social Science Research, Vol. 78, pp. 187-202, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/J.SSRESEARCH.2018.12.015.

[28] Almond, D., J. Currie and V. Duque (2018), “Childhood circumstances and adult outcomes: Act II”, Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. 56, pp. 1360-1446, http://dx.doi.org/10.1257/jel.20171164.

[119] Almond, D., J. Currie and V. Duque (2018), “Childhood Circumstances and Adult Outcomes: Act II”, Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. 56/4, pp. 1360-1446, http://dx.doi.org/10.1257/jel.20171164.

[116] Anderson, P., L. Doyle and A. Group (2003), “Neurobehavioral Outcomes of School-age Children Born Extremely Low Birth Weight or Very Preterm in the 1990s”, JAMA, Vol. 289/24, p. 3264, http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.289.24.3264.

[30] Anderson, P., L. Doyle and Victorian Infant Collaborative Study Group (2003), “Neurobehavioral outcomes of school-age children born extremely low birth weight or very preterm in the 1990s.”, JAMA, Vol. 289/24, pp. 3264-72, http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.289.24.3264.