This chapter reviews Indonesia’s investment and competition framework in the context of clean energy. It examines the country’s efforts to level the playing field between the national power utility and independent power producers, as well as to create a fair, efficient and transparent procurement process for renewables. It assesses Indonesia’s foreign direct investment regime, highlighting possible avenues to make it more attractive to foreign investors in the clean energy sector. The chapter also explores other important avenues to improve the framework for clean energy investment, including how to facilitate land access and acquisition and reduce the costs of clean energy equipment (local content requirements) as well as how to better harness public-private partnerships for clean energy.

Clean Energy Finance and Investment Policy Review of Indonesia

4. Investment and competition policy

Abstract

In light of its clean energy investment needs and limited public resources, Indonesia will need to attract increasing amount of private investments, including from foreign sources, if it is to realise its clean energy goals by 2025. Luckily, Indonesia’s tremendous clean energy potential makes it a naturally attractive destination for Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) for clean energy, which is confirmed by the upward trends observed in the share of renewables in FDI (albeit from a low level) over the last decade. However, FDI in clean energy is still far from where it could be and continues to be dwarfed by FDI in fossil fuels.

Reversing this trend will necessitate a strong investment and competition framework that can level the playing field between foreign and domestic, state-owned and private investments as well as allow for a transparent, clear and predictable investment process. At the same time, Indonesia urgently needs to continue greening its economy and enable corporate access to clean energy or it faces the risk of missing out on investment opportunities from global investors who are increasingly aware and committed to sustainability. Aware of these challenges, Indonesia has already taken a number of actions to reverse these trends. Most notably, Indonesia passed the Omnibus Law on Job Creation in October 2020, which is expected to usher in far-reaching improvements in Indonesia’s investment and competition framework, although its impact will ultimately depend on follow-on regulations.

Assessment and recommendations

There is a need to improve the transparency and fairness of PLN’s (the state electricity company) power procurement process

PLN’s dominant position in power procurement is a challenge for many independent power producers (IPPs), particularly under Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources (MEMR) Regulation No. 50 of 2017 on the utilisation of renewable energy, which makes procurement complex, long and opaque. This is particularly the case for direct selection under PLN, which has led to few pre-qualifications over the last two years, with long delays in the process. Similarly, getting projects listed in the Electricity Business Plan (RUPTL) has been particularly challenging for developers, given the lack of legal basis for developers’ partnerships with PLN’s subsidiaries (a way to avoid listing in the RUPTL), resulting in few financial institutions willing to provide financing for those projects. The implementation of Ministerial Regulation No. 04/2020 as well as on-going preparations of a Renewable Energy Law should help to improve the transparency and competition aspects of the procurement process, although subsequent implementation and consistency of those regulations will be critical to scale up private investment for renewable energy.

Indonesia’s FDI regime for clean energy remains restrictive although reforms are under way

Indonesia has taken positive steps to improve the attractiveness of its FDI regime for clean energy. Most notably through the replacement of the 2016 “negative” investment list regulation with Presidential Regulation No. 10/2021 on Investment Business Lines (often called the “positive” investment list) in a bid to liberalise the country’s FDI regime. The list notably allows foreign investment (up to 100%) in a large number of power business fields, including 1-10 MW projects that used to be restricted to 49% foreign ownership. Such effort is particularly important as the level of FDI inflows in Indonesia (including in clean energy) lags behind that of many neighbouring countries. Nevertheless, Indonesia continues to impose limits on employment of foreign personnel at key management positions as well as minimum capital requirements (IDR 10 billion – around USD 700,000) that are 200 times higher than what is required from domestic companies. As a result, Indonesia’s FDI regime tends to create higher entry barriers for foreign clean energy developers that have an important role to play in clean energy deployment, especially in eastern and smaller islands (where projects are often below 10 MW), given capacity issues of smaller local developers.

Local content requirements (LCRs) remain high and weigh on project investment cost

LCRs can be a key roadblock for renewable IPPs. Indonesia applies LCRs to the power sector, including some renewable energy technologies (solar, geothermal and hydro power) in a bid to grow the country’s manufacturing base and thereby contribute to wider industrial development and job creation goals. For solar photovoltaics (PV), minimum LCRs have been increased from 40% in 2012 to 60% in 2019. Given the typical small size of local manufacturers and lack of competitiveness in the market, these requirements mean developers can struggle to get projects off the ground. Higher prices of locally produced and assembled components also means that LCRs can significantly weigh on project investment costs. While Indonesia’s goals to promote industrial expansion and job creation are laudable, global evidence shows that LCRs for wind and solar have overall had mixed (if not negative) effects on industrial development, job and value creation. Consequently, the gradual removal of LCRs, in tandem with support measures to increase local manufacturers’ capacity and competitiveness, can reduce renewable electricity costs while supporting intended job creation and industrial expansion.

Indonesia is making efforts to improve land access

Land acquisition remains one of the longest lead items in renewable power project development, due to lack of clarity in Indonesia’s land registry and borders. Inconsistent and often overlapping sectoral spatial plans, alongside fragmented land administration, add to this lack of clarity and risks overlap across multiple project land rights. Indonesia has made commendable efforts to clarify land tenure and spatial plans, for instance under its ONE Map Policy and by creating a legal framework (e.g. the 2012 Land Acquisition Law). Further measures on land acquisition (e.g. Presidential Regulation No. 04/2016 on the Acceleration of Power Development and Presidential Regulation No. 38/2015 on PPPs) have also facilitated this process. The Omnibus Law should also help streamline and facilitate land access, although it remains to be seen how this will be ultimately implemented.

More can be done to harness public-private partnerships (PPPs) for clean energy

Indonesia has created a comprehensive legal framework for PPPs, including specific measures allowing government contracting agencies to use PPPs for clean energy projects. In recent years, Indonesia has taken steps to reverse this and implemented a number of clean energy projects. In the energy efficiency sector, there are three on-going street lighting projects being conducted under PPP arrangement (e.g. the Surakarta Street Lighting project). In the power sector, some waste-to-energy PPP projects are being conducted in five municipalities, which could prove particularly useful to achieve ambitions such as the presidential target to have 12 municipal waste-to-energy power plants in operation by 2022. Yet, in spite of these efforts, the use of PPP contractual arrangements for clean energy remain overall very limited. To harness the considerable potential for PPPs, effort is needed to address barriers such as limited capacity of government contracting agencies to implement such arrangements and restrictions for government institutions to enter into multi-year contracts.

Box 4.1. Main policy recommendations on investment and competition

Gradually move towards a competitive auction system for the procurement of renewable power across all technologies, build upon past and international experiences in holding competitive tenders for geothermal projects. Consider embedding such procurement requirements in the Renewable Energy Law (now under preparation), which would shelter developers from possible regulatory changes due to political cycles. Develop clear implementing regulations and guidelines for PLN in order to guarantee transparency, predictability and competition in the procurement process

Building on current reforms, consider conducting regular and comprehensive clean‑energy‑sector assessments of the FDI regime to ensure alignment with and support of clean energy objectives. In particular, consider evaluating current limits for foreign equity for projects below 1 MW and other FDI restrictions such as minimum capital requirements and restrictions on foreign personnel, which remain higher than that of the OECD as well as Thailand and Viet Nam. In the process, Indonesia should ensure current rules are justified (particularly in light of domestic firms’ capacity and resources) and do not impinge on clean energy and energy affordability objectives, involving relevant stakeholders and ensuring their input is thoughtfully considered.

Evaluate LCRs and ensure current regulations reduce project costs, as this will contribute to growth in sector employment, including demand for manufactured equipment. To promote local manufacturing capacity and competitiveness, provide support to the local industry through targeted research and development programmes, knowledge and technology transfer as well as training and capacity building activities.

Accelerate efforts under the One Map Policy to reduce land access uncertainties and reduce market barriers, which weigh on clean energy project costs. As is already the case for PPP projects, endeavour to secure tracts of land prior to project tenders as this has proved to be a key success factor in recent solar auctions held in Cambodia and India. In this regard, consider more actively submitting project proposals to LMAN (Lembaga Manajemen Aset Negara or State Asset Management Agency) to benefit from land acquisition funding under the Land Funding Scheme.

Continue to improve understanding and capacity of government contracting agencies, including local governments and PLN, to originate, develop and monitor implementation of PPP agreements for clean energy projects. In particular, Indonesia should review public procurement regulations to address barriers to government institutions entering into contracts with developers.

Creating a level playing field between public and private investors in clean energy infrastructure

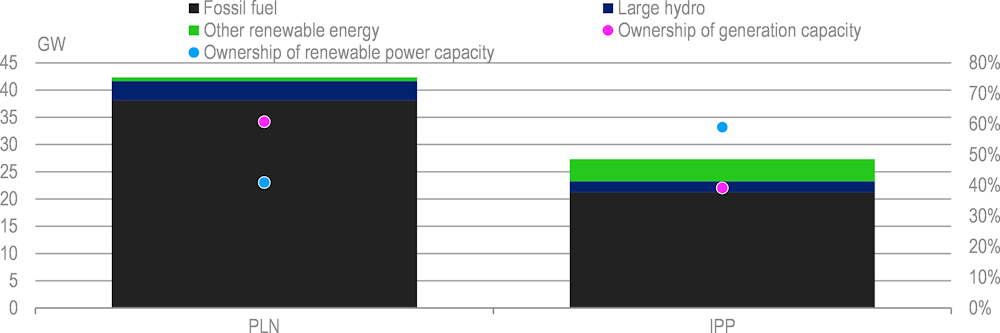

PLN dominates all segments of Indonesia’s power market, acting as a quasi-monopoly (see Chapter 2). IPPs are allowed to own and operate power generation assets but have so far played a limited role as most of the country’s fossil-fuel dominated capacity is owned by PLN. However, IPPs own and operate the majority of non-large hydro renewable energy generation assets (see Figure 4.1). While IPPs are legally allowed to directly sell power to consumers (including corporates and households) within a specific business area (also known as a Private Power Utility), most of the power they generate is sold to PLN. Equally, PLN is the sole owner and operator of the transmission and distribution infrastructure, which is closed to private investments (despite rare exceptions) (see Chapter 2).

Figure 4.1. Ownership of Indonesia’s power generation assets, 2019

Note: Large hydropower refers to hydro projects with a capacity >10 Mega Watts. GW=Giga Watt.

Source: MEMR and PLN statistics.

More efforts are needed to level the playing field between IPPs and PLN

Numerous IPPs have reported difficulties in dealing with PLN. In a stakeholder consultation held in 2019, some IPPs voiced concerns around the patchy and arbitrary application of regulations at the regional level, making it difficult to develop projects; this also reflects potential vertical coordination issues between PLN’s central and regional offices. Risk of curtailments of renewables has also been a major concern for investors (Dutt, Chawla and Kuldeep, 2019[1]). Lack of transparency and clarity in PLN’s power procurement rules and criteria (from getting projects listed in the RUPTL to tender participation) has also been pointed out as a barrier for renewable energy developers (see next section).

The absence of a powerful, well-resourced and independent electricity market competition authority has made it difficult to address these issues in a fair and transparent way. Indeed, while MEMR (through the Directorate General of Electricity) acts as the de facto power regulator, it effectively holds little authority over PLN’s operations and management (its performance being supervised by the Ministry of State-Owned Enterprises) as well as on competition-related matters; it also lacks political independence adding to investors’ concerns. Instead, competition matters (including for public tenders) fall under the responsibility of the Indonesian Competition Authority, which in practice has played a very limited role in the power sector. To tackle these concerns, Indonesia established a Grid Management Committee for the Java‑Bali‑Madura grid in 2007, chaired by a number of relevant stakeholders (including PLN and IPPs) which reviews grid rules and their implementation, publishes interpretations and guidelines on grid rules and makes recommendations for changes to grid rules. Then again, the committee has lacked the authority to effectively address competition issues between PLN and private developers.

There is a need to create a more transparent, clear and predictable procurement process

PLN’s procurement process, conducted by direct appointment and direct selection (see Chapter 3), follows the generation capacity plans in the RUPTL (see Chapter 2). Notably, MEMR Regulation No. 50/2017 on the Utilisation of New and Renewable Energy (amended by MEMR Regulation No. 4/2020) allows PLN to award the development of geothermal and waste-to-energy power projects (as well as most fossil fuel technologies) to IPPs. While this direct appointment can be organised in the form of a public tender, as has been the case for a number of geothermal projects over the last decade, there is virtually no obligation for PLN to do so. In the case where developers submit project proposals on an unsolicited basis (to then be appointed via direct appointment), PLN is responsible for reviewing, approving and ultimately listing approved proposals in the RUPTL. However, IPPs submitting unsolicited project proposals under direct appointment have sometimes faced challenges in getting their projects listed in the RUPTL.

For all other renewable energy technologies, direct selection allows PLN to tender projects out to a limited number of eligible project developers based on technology capacity quotas (defined in the RUPTL). To be eligible, developers must participate in a prequalification process in order to be shortlisted (or pre-qualify) against a set of pre-defined criteria (see Chapter 3). Yet, while this process aims at filtering out developers with poor financial credentials and limited experience, pre-qualification processes have been held on an irregular basis over the years and their criteria varied year on year (PwC, 2018[2]). Direct selection also allows PLN to arbitrarily invite eligible developers to bid for projects, whereas unsolicited project proposals are not allowed under direct selection.

PLN’s power procurement mechanisms under MEMR Regulation No. 50/2017 are complex, long and opaque. Very few pre-qualifications have been held over the last two years under direct selection and, when this is the case, results were announced with a long delay in the process (e.g. one year for the 2017 pre-qualification) (Burke et al., 2019[3]). Pre-qualification criteria have also been unclear and inconsistent across prequalification processes, with questionable impact: in 2017, around 27 clean energy power purchase agreements (PPAs) did not reach financial close, partly because winning IPPs lacked creditworthiness as well as the ability to develop credible feasibility studies (IESR, 2019[4]; PwC, 2019[5]). The result is that some developers have opted for partnering with PLN’s subsidiaries (as this does not require listing in the RUPTL). Yet, with no legal basis in place for such partnerships, few financial institutions or development finance institutions are willing to provide financing for these projects.

On a positive note, Indonesia has taken steps to simplify PLN’s procurement process through MEMR Regulation No. 04/2020. The regulation notably reinstates the possibility to procure all renewables through direct appointment under specific conditions, e.g. if there is only one bidding IPP. This is welcome, although further steps will need to be taken to simplify procurement, in particular, systematically adopting open competitive tenders to procure renewables. Aside from geothermal, Indonesia had already designed a competitive tender programme for solar projects in 2013 (MEMR Regulation No. 17/2013) but the regulation was later rescinded due to pressure from PLN and local manufacturing associations (Kennedy, 2018[6]). Building from that experience, Indonesia should gradually move towards a competitive auction system for the procurement of all renewables, particularly as recent auctions held in India (under the National Solar Mission) or Denmark (for wind power) proved successful in pushing down the cost of renewables (see Chapter 5).

Promoting equal treatment of foreign and domestic investors in clean energy

Indonesia’s dynamic economy and large domestic market makes it a key destination for FDI, which has been on an upward trend over much of the last decade and a half, despite a recent slowdown. While manufacturing and services have been the largest FDI recipients, the energy sector – including clean energy – has also been a coveted sector due to the country’s tremendous potential. Yet, FDI inflows have slowed as of late and remain below the level of neighbouring countries such as Viet Nam and Cambodia, which have been accounting for growing shares of FDI inflows in ASEAN countries, in the backdrop of US‑China trade tensions, and has been integrating at a much faster pace in global value chains than Indonesia. This also holds true in the clean energy sector, where the share of greenfield FDI flows in renewables of countries such as Cambodia, Laos or Viet Nam, have far exceeded that of Indonesia over the last decade and a half (The Jakarta Post, 2019[7]; OECD, 2020[8]).

In the face of these issues, the Indonesian President, Joko Widodo, reiterated commitment to accelerate inwards FDI in Indonesia and improve the ease of doing business in the country. Acting on such commitment and in the context of the COVID-19 crisis, Indonesia passed the Omnibus Law on Job Creation in October 2020 in a bid to repeal a number of overlapping regulations, ease restrictions on FDI (including in the negative investment list) as well as centralise and streamline business licensing and land acquisition procedures. While this is a welcome step (albeit one faced with strong labour and civil society opposition), the impact of the law on the business environment for clean energy will eventually depend on ensuing implementing regulations. Importantly, these reforms should not undermine environmental safeguards for projects (including public consultation) and should support Indonesia’s efforts to green its economy and widen corporate access to clean energy. These efforts are paramount to ensure Indonesia is not left behind as global investors are increasingly aware and committed to sustainability. For example, following the passing of the Omnibus Law and upcoming implementing regulations, a group of 36 investors with around USD 4.1 trillion in assets under management urged the government to “support the conservation of forests and peatlands; uphold human rights and customary land rights of indigenous peoples; hold proper consultations with environmental and civil society groups and investors on the Law and its implementation; and take a long-term approach to recovery from the pandemic” (OECD, 2020[8]).

Indonesia is making considerable efforts to liberalise its FDI regime for clean energy

Prior to 2021, Indonesia had a large number of FDI restrictions in place, most of which were set out in the negative investment list. As mandated by the 2007 Investment Law, the negative investment list (lastly revised in 2016) listed a number of power business fields closed to private (both foreign and domestic) investment as well as open under certain restrictions (including foreign ownership restrictions)(see Table 4.1). The list sometimes granted more favourable treatment to ASEAN investors (in the form of higher equity ownership limit), although this did not apply in the aforementioned sectors.

With the passing of the Omnibus Law in 2020, the negative investment list was re-conceptualised into a “positive investment list” as set out in Presidential Regulation No. 10/2021 on Investment Business Lines, thereby liberalising numerous business fields to foreign investment. The general principle of the positive investment list is that a business field is open to 100% foreign ownership unless otherwise specified. The new list categorises business sectors into three broad categories: 1) priority sectors (defined based on a set of criteria), benefitting from a number of fiscal and non-fiscal incentives (245 business fields); 2) business fields allocated to or reserved for partnership with, local cooperatives and micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs); and 3) business fields open to foreign investment but subject to certain limitations or requirements. Under this list, most power business fields are now classified as “priority sectors” (see Table 4.1). Most notably, this means that foreign IPPs are now eligible for certain fiscal incentives (including tax allowance and tax holiday) as well as non-fiscal incentives (e.g. ease of obtaining business permits, provision of supporting infrastructure, guarantees on availability of raw materials, immigration and others) (see Chapter 5).

Nevertheless, power projects below 1 MW remain closed to foreign investment and so do certain electric power installations and construction services. While Indonesia’s rationale to impose such restrictions to promote the development of domestic small-scale IPPs is understandable, it should nonetheless account for local capacity and resource constraints in the clean energy sector. This is particularly key given that in recent years, numerous domestic, small-scale IPPs have faced considerable capacity and creditworthiness issues (especially in developing mini and micro hydro projects) (IESR, 2019[4])

Table 4.1. Foreign equity restrictions apply to a range of renewable energy-related areas

|

Business sectors |

Foreign equity limitations |

|

|---|---|---|

|

2016 negative investment list |

2021 positive investment list |

|

|

Geothermal drilling services |

95% |

Up to 100% |

|

Geothermal operating and maintenance services |

90% |

Up to 100% |

|

Power generation below 1 MW |

Closed to foreign ownership |

Closed to foreign ownership reserved for cooperatives and MSMEs |

|

Power plant between 1-10 MW |

49% |

Up to 100% |

|

Geothermal power plant up to 10 MW |

67% |

Up to 100% Closed if below 1 MW |

|

Power plant beyond 10 MW |

95% (100% if as part of PPP during concession period) |

Up to 100% |

|

Geothermal surveying services |

95% |

Up to 100% |

|

Construction and installation of electric power: Installation of electric power supply |

95% |

Up to 100% (if high voltage) Closed if low/medium voltage |

Source: Presidential Regulation No. 44/2016 ”Negative Investment List”. Presidential Regulation no. 10/2021. PPP=Public Private Partnerships.

While the loosening of foreign equity limits is a commendable effort, there remains other significant restrictions to FDI in place (also applying to the clean energy sector). Among other restrictions are limits on the employment of foreign personnel in key management positions as well as minimum capital requirements for foreign-invested companies (set at IDR 10 billion or around USD 700 000 excluding land and buildings, 25% of which should be paid-up in full before starting a business). Such capital requirements are 200 times what is required from local companies, which is rather exceptional given few countries impose requirements at such a high-level worldwide (and these are rarely discriminatory) (OECD, 2020[8]). There can be certain exemptions in Special Economic Zones, however. Minimum capital requirements could represent a significant barrier for foreign small-scale IPPs and clean energy small and medium enterprises, despite the high innovative potential that many of these small-scale investors can bring (OECD, 2015[9]).

LCRs drive up projects’ investment costs

Indonesia continues to impose stringent local content rules for a number of clean energy projects. In a bid to support national industrial development and job creation, the Ministry of Industry has set out minimum LCRs for solar, geothermal and hydro power projects (as well as most fossil fuels and network infrastructure), which are considered as part of renewable power procurement. Most notably, MEMR Regulation No. 05/2017 (amending MEMR Regulation No. 53/2012 on LCR for Power Infrastructure and based on Ministry of Industry Regulation No. 54/M-IND/Per/3/2012) imposed a 40% minimum LCR target for solar PV projects in 2017 that was later increased to 60% in 2019. Given the limited capacity of the local manufacturing base for solar components, project developers struggle to comply with the target, with current local content of solar projects hovering around 43% in 2020.

Table 4.2. Indonesia imposes a number of LCRs for geothermal, hydro and solar technologies.

|

MW |

LCR (Goods and Services combined) |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Solar PV |

- |

60% (set at 43.85% over 2012-19) |

|

Geothermal |

<5 |

42% |

|

5-10 |

40.45% |

|

|

10-60 |

33.24% |

|

|

60-110 |

29.21% |

|

|

>110 |

28.95% |

|

|

Hydro (excl. pump storage) |

<15 |

70.76% |

|

15-50 |

51.60% |

|

|

50-150 |

49% |

|

|

>150 |

47.6% |

Source: MEMR regulation no. 05/2017 and MEMR regulation no. 53/2012 based Minister of Industry regulation 54/M-IND/Per/3/2012.

There is wide evidence that LCRs significantly increase project costs, especially when local manufacturers produce at higher costs than international competitors, thereby making the cost of intermediate input more expensive. This is the case of Indonesia’s solar PV industry where locally-produced module prices average USD 0.47/Wp (Watt peak) compared to imported module prices ranging from USD 0.25 - 0.37/Wp. This, in turn, has contributed to slowing solar PV market expansion, making downstream investment more expensive (IESR, 2019[4]). In this regard, IESR estimates that accessing module price at the international market price would lower the solar Levelised Cost of Electricity (LCOE) by up to 50% (IESR, 2019[10]).

While Indonesia’s job creation and industrial development goals are commendable, global evidence shows that LCRs are not the most effective tool to realise these. Experience from India’s National Solar Mission Programme since 2010, for instance, shows that projects tied to LCRs registered a significant cost increase (e.g. a USD 68-88 million top-up per installed GW over 2014-17) while having overall mixed (short-term) effects on manufacturing of solar PV (particularly crystalline-silicon) over 2010-17 (Probst et al., 2020[11]). This can be explained by the fact that the manufacturing segment of solar PV and wind production, generates relatively less value and employment than downstream activities (i.e. project development, construction, installation, operation and maintenance). Indeed, evidence from the solar PV production value chain in the US shows that more than half of the value generated from solar production lies downstream of module production, with that segment also accounting for the bulk of employment (70% for silicon-crystalline solar PV). Therefore LCRs could also have a negative impact on downstream job creation through affecting demand. They could also further slow Indonesia’s integration in global value chains (OECD, 2015[12]).

Facilitating land access for renewable energy projects

Project developers are responsible for securing land for a project’s site as well as associated network infrastructure to connect the project to the nearest substation (which can be 20 to 40 kilometres long). Before accessing land, developers must obtain a location permit, granted upon compliance with power infrastructure and other regional spatial plans (referring to national plans) as well as approval from the Ministry of Environment and Forestry (MoEF) in case the project is established in the state forest (which accounts for two thirds of Indonesia’s land area; see (OECD, 2019[13]) for more detailed information on state forest). The Land Agency Office is the sole body responsible for granting location permits as well as issuing land rights for power projects. In practice, however, developers are left to directly negotiate with land owners to agree on a purchase price or rent for the land (of not more than five hectares). Additionally, foreigners are not allowed to own land and thus usually rely on a local partner.

Unclear land registry and spatial planning have created uncertainty over land tenure and caused numerous land disputes locally. With a land registry only covering 35% of the country’s land – mostly in urban areas – numerous Indonesians continue to hold informal land rights (or exert de facto control over it) making it a challenge for developers to access land (OECD, 2020[8]). For instance, the country’s second large-scale on-shore wind project had to deal with no less than 500 landowners and 100 sharecroppers (spread across 8 villages and 4 districts) in order to access land (Kennedy, 2020[14]). Compounding this issue, inconsistent and often overlapping sectoral spatial plans, alongside fragmented land administration, have caused numerous infrastructure projects to be granted land rights over the same tracts of land, leading to land disputes (OECD, 2019[13]; Dutt, Chawla and Kuldeep, 2019[1]). This, in turn, has made land acquisition one of the longest lead items in renewable energy project development.

In the face of these issues, Indonesia has been taking important steps to improve land tenure and facilitate land access. Important land reforms were started in 2019 through the One Map Policy, which aims to improve consistency across spatial plans using a centralised geospatial data repository (e.g. land tenure and use, and topography) which should help avoid overlapping land right issues (see Chapter 2; (OECD, 2019[13])). Efforts to register land are also being accelerated under the Minister of Agrarian and Spatial Planning Regulation No. 12/2017 on Complete Systematic Land Registration Acceleration. These measures are welcome but will take time to implement given current land registration capacity (OECD, 2020[8]). In the same spirit, the MoEF, in 2015, allowed the establishment of geothermal concessions in protected areas as more than half of the country’s geothermal resources lie in such areas (MEMR, 2017[15]). While the environmental impact of geothermal power plants is usually minor, these could still cause some disturbances to local ecosystems, particularly if not complemented by robust environmental management systems (Dhar et al., 2020[16]).

In addition, the government has been implementing a number of regulations to facilitate land acquisition. These notably include Law No. 2/2012 on Land Acquisition1, which formalises legal procedures for land acquisition and limits its duration to 583 days; Presidential Regulation No. 04/2016 on the Acceleration of Power Infrastructure Development, which further clarifies and formalises land acquisition for power infrastructure projects; as well as Presidential Regulation No.38/2015 on Public Private Partnerships (PPPs), that notably obligates government contracting agencies to secure land prior to the tendering of PPP projects.

As more land is required to attain clean energy targets – e.g. around 8000 km2 is needed to develop 1.5 GW of solar PV – Indonesia needs to step up efforts to facilitate land access under the implementation of the Omnibus Law (Kennedy, 2020[14]). Securing tracts of land prior to project tenders will be critical to reduce project lead time and accelerate investment. Experience in facilitating land access for toll road projects through the LMAN (Lembaga Manajemen Aset Negara or State Asset Management Agency) and under India’s Solar Park Schemes could provide useful lessons for Indonesia’s renewable sector, in this regards (see Box 4.2).

Box 4.2. Experiences in facilitating land acquisition for renewable energy projects

Indonesia’s Land Funding Scheme for national strategic projects

In the face of land acquisition issues for toll road projects and other large-scale infrastructure projects, Indonesia’s Minister of Finance launched the Land Funding Scheme in 2016 to help fund land acquisition for infrastructure projects. The scheme is managed and operated by the State Assets Management Agency (LMAN), which was established in 2015 to manage state assets to generate and improve financial and nonfinancial benefits as well as, since 2016, act as a de facto national land bank (The Jakarta Post, 2017[17]).

Land funding under the scheme can be provided in two ways: direct disbursement, whereby LMAN directly indemnifies land owners for the land to be acquired; and an indirect disbursement, whereby project developers get a refund for their land acquisition expenses. To be eligible for the Land Funding Scheme, projects must be categorised as “national strategic projects” as specified in Presidential Regulation No. 66/2020 on Funding of Land Acquisition in Public Interest for Purposes of Executing national strategic projects (amending Presidential Regulation No. 102/2016). To be categorised as national strategic projects, projects must fulfil a certain set of criteria including, but not limited to, having a strategic role (including for the economy, social welfare, the environment and employment) and having an investment value above IDR 100 billion (around USD 7 million). In the case of power projects, those listed in the RUPTL are all classified as national strategic projects as set out in Presidential Regulation No. 04/2016 on the Acceleration of Power Infrastructure Development. To obtain LMAN support, project proposals can only be submitted by a state entity to the Committee for Acceleration of Priority Infrastructure Delivery (Komite Percepatan Penyediaan Infrastruktur Prioritas or KPPIP), which is responsible for supporting and approving eligibility of national strategic projects for LMAN.

Since the inception of the Land Funding Scheme, LMAN supported 27 toll road projects as well as 26 dams across the country. As of 2021, however, no clean energy projects benefited from LMAN support as neither MEMR nor PLN have yet submitted RUPTL-listed projects to the KPPIP. Given the invaluable financial support LMAN could provide to land-based clean energy projects (and hence help lower their investment costs), MEMR and PLN should seek to play a more active role in championing strategic clean energy projects and obtain LMAN’s support.

India’s Solar Park Scheme

Power evacuation and land acquisition represent significant risks for power project development in India. To lower these risks, the Indian government implemented the Solar Park Scheme in 2015, consisting in securing land and power evacuation infrastructure prior to competitive tenders for large-scale solar parks. While the scheme exclusively addressed solar PV over 2015-19, the government expanded the scope of the scheme to other renewables in 2019 (Economic Times, 2019[18]).

Following a ‘plug-and-play’ model, the Solar Park Scheme transfers the land acquisition and power evacuation risks on to India’s Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (and since 2019, to the Ministry’s SOE, the Solar Energy Corporation of India) thereby making the SOE responsible for acquiring land and developing evacuation infrastructure prior to tendering out solar parks through competitive auctions. This is done in exchange for a usage fee, which in practice has represented a significant price premium for solar-park vs. non-solar park projects, sparking concerns among certain developers. Nevertheless, the Solar Park Scheme helped achieve considerable economies of scale given the large size of projects established in solar parks and contributed to a significant decline in power tariffs, with the lowest prices for the entire solar PV sector registered in solar park capacity auctions.

All in all, India’s solar park scheme has been instrumental in accelerating solar market development in the country, with the share of solar park projects rising from over 38% in 2015 to around 55% of total capacity awarded in 2017 (almost a 3 GW increase). The scheme has helped attract international IPPs (which made up 45% of solar parks against 17% in other renewable projects in 2017) as well as large local IPPs, with the wherewithal to bear the premium and develop large-scale projects. Nevertheless, over 2017-19, India struggled to maintain the high pace of solar park development under the scheme as acquiring the tremendous amount of land needed to develop large-scale projects proved challenging. This caused the share of solar park projects to drop to 7% in 2019.

Despite this challenge, India’s Solar Park Scheme still provides useful lessons to help facilitate land access. First, India’s experience shows that transferring land acquisition and power evacuation risk to the state (beyond funding aspects) can go a long way to accelerate clean power investment. Second, it also shows that land acquisition facilitation alone does not suffice and should be pursued in tandem with efforts to improve land management in order to be effective.

Harnessing public-private partnerships (PPPs) for clean energy

Indonesia has so far made very limited use of PPPs in the clean energy sector

Indonesia has been making efforts to revamp its legal and institutional framework for PPPs in a bid to scale up private investments in infrastructure development under PPP arrangements, so far dominated by SOEs. To that end, Indonesia created a number of institutions (e.g. IIGF, PT SMI, LMAN) as well as developed a comprehensive and unified regulatory framework for PPPs in 2015 through Presidential Regulation No. 38/2015 on cooperation between the government and businesses, appointing Bappenas as the lead coordinating ministry for PPPs. The presidential regulation notably formalises the PPP implementation stages (from the preliminary study stage through to financial closure) and sets out a number of eligible sectors for PPPs, including energy conservation and power generation. The regulation allows private project proponents to submit proposals on a solicited or unsolicited basis. In all instances, however, the selection process must be conducted through an open, competitive tender, preceded by a value for money evaluation (using a Public Sector Comparator2 method) (APEC, 2019[21]). In 2016, the PPP Joint Office was established to coordinate and assist line ministries, government contracting agencies and investors, and to serve as a de-facto one-stop shop for PPP-related issues.

The regulation also introduced a number of instruments to support PPP projects. Most notably, projects can benefit from government guarantees (through the IIGF; see Chapter 6); a Viability Gap Fund, to improve the financial viability of projects (important as only 10% of PPP projects are fully financially feasible) through contributing up to 49% of the construction, equipment and installation costs; a Project Development Facility to assist projects in the preparation phase; as well as partial construction support. Additionally, the regulation makes land acquisition an obligation of the government contracting agency and allows projects categorised as a national strategic project to benefit from the Land Funding Scheme (see Box 4.2; (APEC, 2019[21])).

While there is an increasing number of infrastructure projects developed under PPP arrangements, there have been very few in the clean energy sector. There have so far been a few waste-to-energy projects developed in five cities, which could have a great demonstration effect and help realise the President’s target to develop and operate 12 waste-to-energy power plants in 12 municipalities by 2022 (which, combined, should create up to 234 megawatts of electricity using 16,000 tonnes of waste a day). In the energy conservation sector, there are three on-going street lighting projects in Madiun, West Lombok and Surakarta city (see Box 4.3). While limited in number, these projects are promising examples of PPP energy saving models that could be replicated in other cities and help familiarise government institutions with such projects.

Overall, a number of elements explain why few clean energy projects have taken off under PPP arrangements. First, PPP contracts are often very complex and require extensive co-ordination across a range of stakeholders, making their implementation particularly challenging. Second, government contracting agencies continue to lack both familiarity with clean energy projects as well as the skills and experience to undertake PPPs. Equally, the fact that current PPP documents and procedures are still geared towards traditional, large-scale infrastructure projects and lack standardisation has made it difficult to develop energy efficiency projects through PPP models (see Chapters 3 and 5).

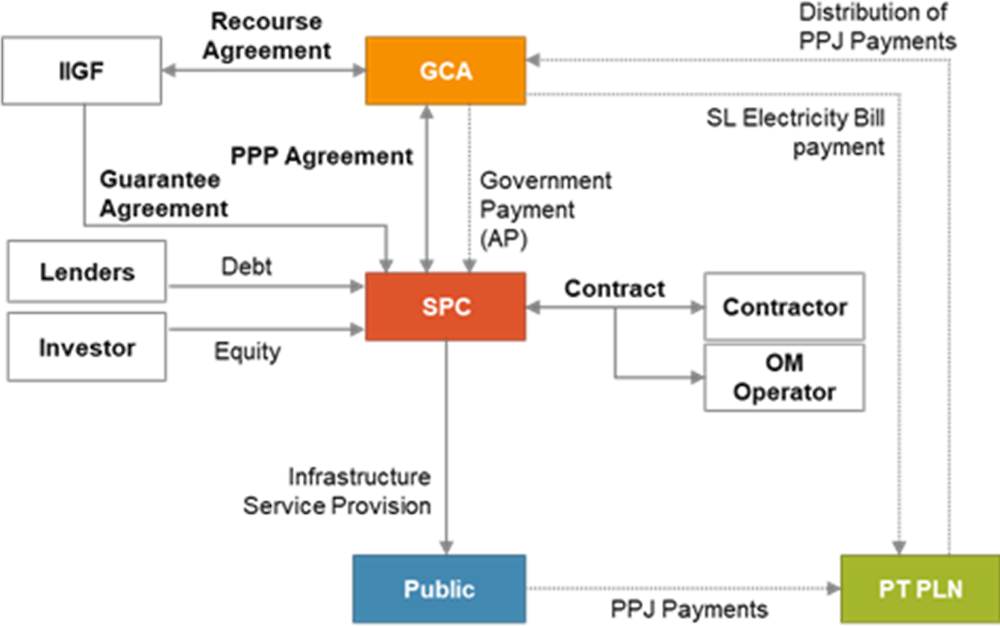

Box 4.3. The Surakarta Street Lighting project

The Surakarta’s street lighting project was initiated by the municipality of Surakarta in 2018 in a bid to revamp and extend previous public street lighting infrastructure covering around 976 km (of which, 335 km are strategic roads). The project was undertaken following a 2016 survey showing both qualitative and quantitative shortcomings of previous public lighting infrastructure. On the one hand, the survey showed that numerous lamps and poles were non-compliant with national standards and that significant savings could be achieved through replacing existing lamps with more energy-efficient LED lamps. On the other hand, the survey highlighted that previous lighting infrastructure did not satisfy actual needs estimated at around 31,890 lamp points (against 21,222 in 2016).

The project is being prepared under PPP arrangements (following Presidential Regulation No. 38/2015) with the municipality of Surakarta as the government contracting agency. The municipality completed and submitted a final business case to prospective developers in mid-2020. Following a pre-qualification process held at the end of 2020, three consortia of local and international companies are expected to bid for the 17-year concession. The winning bidder will be responsible for building, financing, operating and maintaining Surakarta’s public street lighting. The project’s forecasted internal rate of return was estimated at 13.24% over 17 years, which is lower than rates observed for energy efficiency in Singapore and the Philippines, often in the upper teens. The project’s indicative financial information is summarised in the table below:

Table 4.3. Surakarta public lighting project financial information

|

Estimated project cost |

USD 25.7 million (17 years) |

|---|---|

|

Debt level |

70% |

|

Equity level |

30% |

|

Project IRR |

13.24% |

|

Equity IRR |

15% |

Note: IRR= Internal Rate of Return*. The internal rate of return is a financial metric used to estimate the profitability of potential investments. It represents the discount rate that makes the net present value of a project’s cash flows equal to zero in a discounted cash flow analysis.

The project will benefit from the Ministry of Finance’s assistance under its Project Development Facility and is expected to reach financial close in 2022. The project will also benefit from a government payment guarantee administered by the IIGF to guarantee availability payment by the Municipality.

Figure 4.2. Financing structure of the Surakarta public street lighting project

*AP=Availability Payments. GCA=Government Contracting Agency. OM= Operation and Maintenance. PPJ= Pajak Penerangan Jalan or Street Lighting Tax.SL= Street Lighting. SPC=Special Purpose Company.

Source: Bappenas and PT SMI.

Other investment-related issues

Other issues relating to intellectual property, contract enforcement and investment treaties play an important role in creating a healthier regulatory climate for investment. The OECD Investment Policy Review of Indonesia 2020 discusses Indonesia’s progress on these issues in more detail and identifies potential areas for improvement. While the report’s messages are not specific to clean energy, they have important implications. The following list highlights selected messages from the Investment Policy Review on aforementioned issues with implications for clean energy:

The 2007 Investment Law guarantees “to provide the same treatment to any domestic and foreign investors, by continuously considering the national interest” and to provide “equitable treatment to all investors of any countries that carry out investment activities in Indonesia in accordance with provisions of laws and regulations.” (Article 6). As explained in this chapter, however, these non-discrimination guarantees are not always enforced in practice in the clean energy sector, although on-going reforms are a step in the right direction.

Indonesia’s dispute resolution mechanisms have a good track record overall, although there have been concerns over the court system’s transparency and fair treatment as well as the effectiveness of contract enforcement. Concerning contract enforcement, the process often appears lengthier and costlier than in some neighbouring countries. The World Bank, for example, ranks Indonesia 139th out of 196 countries in terms of “contract enforcement”3 as part of its Ease of Doing Business index. While efforts are underway, continuing to improve the access and efficiency of local courts is critical in order to ensure predictability in commercial relationships as well as ensure an effective and clear contract enforcement process. This is particularly important for clean energy investment, given the high number and often complex contractual arrangements involved in project development.

Indonesia has 36 investment treaties in force today, covering around 41% of its inward FDI (almost half of that share being covered by the ASEAN Comprehensive Investment Agreement treaty). Yet, a significant number of these treaties contain vague investment protections that may create unintended consequences. As in many countries, Indonesia has thus started to modernise and renegotiate some of these treaties (e.g. 23 treaties were terminated over 2014-16) and is about to enter into new ones. Nevertheless, while investment treaties can provide much-needed investor protection and contribute to a friendlier business environment, these should not replace efforts to improve the current investment framework (e.g. FDI regime, LCR, court system, intellectual property etc.) which, as nascent evidence shows, could be more effective at accelerating FDI (including in the clean energy sector).

Indonesia’s intellectual property legal framework is overall solid, regularly amended and in line with international standards. However, more efforts are needed to improve intellectual property rights protection and enforcement, as the implementation and enforcement of existing laws remain overall weak. Cutting down currently lengthy Intellectual Property application processing times is also needed to incentivise innovation. These efforts are paramount to boost clean energy innovation, which ultimately will contribute to slash project costs – as has been the case in India where solar PV patenting has increased dramatically under its National Solar Mission Programme – as well as improve Indonesian manufacturers’ competitiveness.

References

[21] APEC (2019), Peer Review and Capacity Building on APEC Infrastructure Development and Investment: Indonesia, Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation, https://www.apec.org/Publications/2019/11/Peer-Review-and-Capacity-Building-on-APEC-Infrastructure-Development-and-Investment-Indonesia (accessed on 23 December 2020).

[3] Burke, P. et al. (2019), Overcoming barriers to solar and wind energy adoption in two Asian giants: India and Indonesia.

[19] Chawla, K. et al. (2018), Clean Energy Investment Trends: Evolving Landscape for Grid-Connected Renewable Energy Projects in India, CEEW and OECD/IEA, New Delhi.

[16] Dhar, A. et al. (2020), “Geothermal energy resources: potential environmental impact and land reclamation”, Environmental Reviews, pp. 1-13, http://dx.doi.org/10.1139/er-2019-0069.

[1] Dutt, A., K. Chawla and N. Kuldeep (2019), Accelerating Investments in Renewables in Indonesia Drivers, Risks, and Opportunities, Council on Energy, Environment and Water.

[18] Economic Times (2019), Govt modifies solar park scheme to ease land, evacuation constraints, https://energy.economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/renewable/govt-modifies-solar-park-scheme-to-ease-land-evacuation-constraints/68374675 (accessed on 17 December 2020).

[4] IESR (2019), Indonesia Clean Energy Outlook - Tracking Progress and Review of Clean Energy Development in Indonesia, Institute for Essential Services Reform , Jakarta, http://www.iesr.or.id (accessed on 16 November 2020).

[10] IESR (2019), Levelized Cost of Electricity in Indonesia - Understanding The Levelized Cost of Electricity Generation, http://www.iesr.or.id (accessed on 6 April 2020).

[14] Kennedy, S. (2020), Research: land use challenges for Indonesia’s transition to renewable energy, The Conversation, https://theconversation.com/research-land-use-challenges-for-indonesias-transition-to-renewable-energy-131767 (accessed on 6 November 2020).

[6] Kennedy, S. (2018), “Indonesia’s energy transition and its contradictions: Emerging geographies of energy and finance”, Energy Research and Social Science, Vol. 41, pp. 230-237, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2018.04.023.

[15] MEMR (2017), Lampu Hijau Untuk Geothermal Di Kawasan Konservasi (Green Light for Geothermal in Conservation Areas), https://ebtke.esdm.go.id/post/2017/03/16/1592/lampu.hijau.untuk.geothermal.di.kawasan.konservasi (accessed on 4 March 2021).

[20] MoF (2020), National Strategic Project as Regional Public Goods in Indonesia, https://www.djkn.kemenkeu.go.id/kanwil-sulseltrabar/baca-artikel/13173/National-Strategic-Project-as-Regional-Public-Goods-in-Indonesia.html (accessed on 21 December 2020).

[8] OECD (2020), OECD Investment Policy Reviews: Indonesia 2020, OECD Investment Policy Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/b56512da-en.

[13] OECD (2019), OECD Green Growth Policy Review of Indonesia 2019, OECD Environmental Performance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/1eee39bc-en.

[12] OECD (2015), Overcoming Barriers to International Investment in Clean Energy, Green Finance and Investment, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264227064-en.

[9] OECD (2015), Policy Guidance for Investment in Clean Energy Infrastructure: Expanding Access to Clean Energy for Green Growth and Development, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264212664-en.

[11] Probst, B. et al. (2020), “The short-term costs of local content requirements in the Indian solar auctions”, Nature Energy, Vol. 5/11, http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41560-020-0677-7.

[5] PwC (2019), As many as 21 PPAs for new and renewable energy power plants planned to be signed this year, https://www.pwc.com/id/en/media-centre/infrastructure-news/april-2019/planned-to-be-signed-this-year.html (accessed on 9 November 2020).

[2] PwC (2018), Power In Indonesia - Investment and Taxation Guide, http://www.pwc.com/id (accessed on 19 July 2019).

[7] The Jakarta Post (2019), Foreign investments flow to neighbors instead of Indonesia: World Bank, https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2019/09/10/foreign-investments-flow-to-neighbors-instead-of-indonesia-world-bank.html (accessed on 20 November 2020).

[17] The Jakarta Post (2017), LMAN gets down to business on promised land, https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2017/04/06/lman-gets-down-business-promised-land.html (accessed on 21 December 2020).

Notes

← 1. Later amended by Presidential Regulation no. 148/2015.

← 2. As part of a value-for-money assessment of a potential PPP project (against traditional procurement or fully-private development) , a ‘public sector comparator’ (PSC) is a common method used to estimate the hypothetical risk-adjusted cost of that project was it to be financed, owned and implemented by the Government.

← 3. The cost dimension of the indicator on contract enforcement refers to average cost of court fees, attorney fees (where the use of attorneys is mandatory or common) and enforcement fees expressed as a percentage of the claim value. The time it takes to resolve a dispute is counted from the moment the plaintiff decides to file the lawsuit in court until payment, and covers both the days when actions take place and the waiting periods in between.