This chapter discusses four main ways that can be used to strengthen regional-level decision-making: i) deconcentration of central government service delivery, ii) intermunicipal co-operation, iii) regional decentralisation and iv) establishing regions with elected self-government and fiscal autonomy. The chapter also describes reforms that have been carried out in European Union (EU) countries. A more detailed description is provided for regional reforms that have been carried out Finland, France and Poland. These countries provide interesting examples of different solutions to similar challenges.

Decentralisation and Regionalisation in Portugal

2. Regionalisation in the context of decentralisation reforms

Abstract

The regional level of government has become more important in both centralised and decentralised countries. While there is no single explanation for this development, the motive for regionalisation in decentralised countries has often been the desire to utilise a bigger scale in public service provision, while still securing the benefits of decentralised decision-making. These reforms have typically transferred powers from the local to regional level, although the reforms usually include some powers transferred also from the central government to regions. In centralised countries, regionalisation has often happened as part of a wider decentralisation reform, for example as a response to growing dissatisfaction on the centralised public service delivery in regions. In these cases, both spending and revenue powers have been transferred from the centre to regions.

This section discusses the main types of regional reforms. The first subsection identifies four main ways that have been used to strengthen regional-level decision-making. The weakest form is to deconcentrate central government service delivery and the strongest form is to establish regions with elected self-government and fiscal autonomy. In between these two extreme policies, the regional-level governance is arranged by intermunicipal co-operation or by regional decentralisation. In the first subchapter, these policies are discussed from both benefit and challenge aspects. The second subchapter describes and discusses the regional reforms that have been carried out in European Union (EU) countries. The third subchapter takes a deeper look at the regional reforms carried out Finland, France and Poland. While these countries differ a lot in their degree of decentralisation, they nevertheless provide interesting examples of different solutions to similar policy questions.

Strengthening regions in a multilevel governance framework

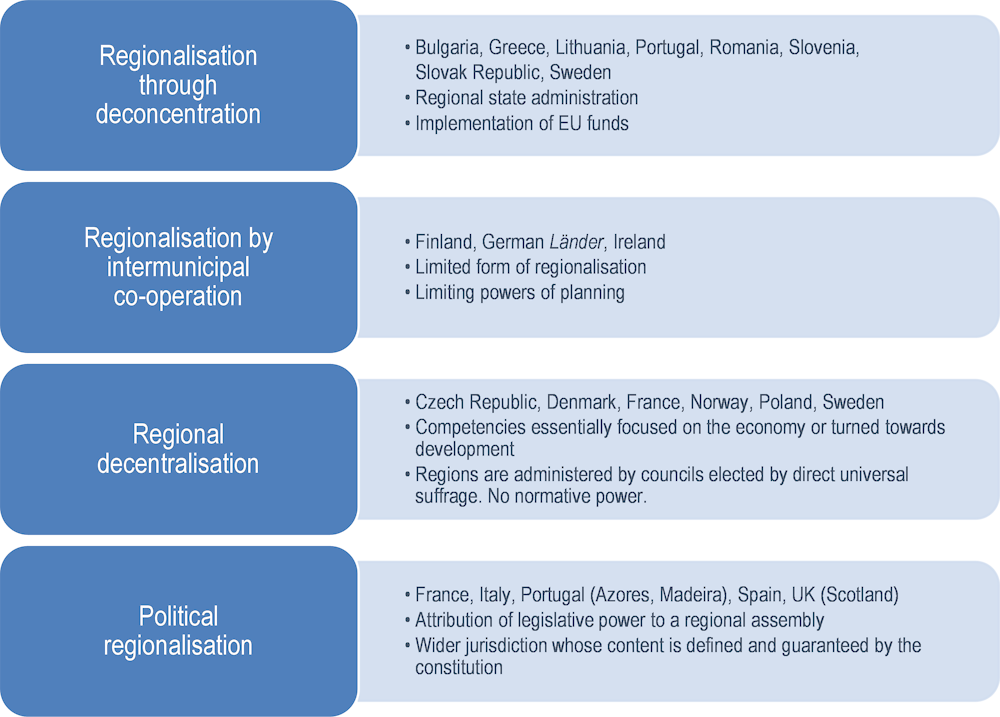

Four main types of regionalisation can be distinguished: i) regionalisation through deconcentration; ii) regionalisation by existing local authorities (intermunicipal co-operation); iii) regional decentralisation; and iv) political regionalisation (or regional autonomy). Before going further in describing each group, some prior explanation is provided below.

First, federalism is not in itself a form of regionalisation. On the contrary, a federal state is a means of state organisation whose structures and operation can be affected by regionalisation in its different forms. Regionalisation of federal units is one of these but it can itself be attached to different types of regionalisation. For this reason, it is very important not to take the federal state as such an expression of regionalisation or regionalism.

Second, regionalisation is not always homogenous. One country can, therefore, feature several forms of regionalisation depending on the problems faced by the state and the particular situations that need to be considered, or perhaps due to competition between different types of institutions to carry out regionalisation-specific operations. For instance, in the United Kingdom, no less than three different types of regionalisation currently exist.

Third, it is important to avoid having a static vision of regionalisation and institutional evolutionism. Obviously, situations can change and, depending on the reforms implemented, a state can successively feature different types of regionalisation. For example, France implemented a purely administrative regionalisation from the 1960s before the current regional decentralisation was introduced at the beginning of the 1980s. Some countries in Central and Eastern Europe could undergo a similar development. However, it is equally important not to consider the different types of regionalisation as the rungs of a virtuous ladder that states need to climb to reach the ideal model of regionalisation, i.e. the greatest regional autonomy. On the one hand, the forms that regionalisation takes in a state do not just depend on the problems that explain its generalisation, which are above all socio-economic; they also depend on numerous other country-specific factors, such as the extent of national integration, the conception of the state accepted by society and political elites, and, of course, the political situation. In addition, regionalisation includes limitations and risks that vary depending on the state and that can be appreciated in different ways.

Table 2.1. Types of regionalisation

|

Sources of legitimacy |

Nature of the action |

Nature of the identification |

Countries |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Regionalisation through deconcentration |

Effectiveness of public policy |

Deconcentrated state administration at the regional level |

Mainly national |

Bulgaria, Denmark, Greece, Lithuania, Norway, Portugal, Romania, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Sweden |

|

Regionalisation by intermunicipal co‑operation |

Effectiveness of public policy |

Limited powers of planning |

Mainly national |

Finland, German Länders, Ireland |

|

Regional decentralisation |

Effectiveness and local democracy |

Decentralisation at the regional level |

Mainly national (and sometimes subnational) |

Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Poland, Norway, Sweden |

|

Political regionalisation |

Cultural identity and local democracy |

Political autonomy at the regional level |

National and subnational (either complementary or conflictual) |

France (overseas territories), Italy, Portugal (Azores, Madeira), Spain, UK |

Source: Author’s modification of Pasquier, R. (2019[1]), “Decentralisation and regionalisation in Portugal: Lessons from international experience and recommendations”, Unpublished manuscript.

Regionalisation through deconcentration

By regionalisation through deconcentration, we mean the administrative reorganisation of central government authorities. In that case, the deconcentrated authorities are subordinate to the central government or of organisations that, although endowed with a degree of legal autonomy, constitute instruments of its action placed under its control, and whose functions, or at least some of them, aim to promote regional economic development, and are to this end based on mobilising local authorities and economic organisations. One example is Luxembourg, whose government has defined four land planning regions, but the country’s very small size does not make it necessary to endow them with their own institutions.

In France, regionalisation was initially based on deconcentration. In 1964, the establishment of regional prefects as part of the regional action districts followed the creation of DATAR (Délégation interministérielle à l'aménagement du territoire et à l'attractivité régionale, Interministerial Delegation of Land Planning and Regional Attractiveness) in 1963. This introduced a new devolved level more appropriate than the smaller département to implement territorial land-planning policies and the national plan. Local authorities and economic and social interests were represented in an advisory committee working under the regional prefect; in some regions, economic development bodies were set up associated with representatives of the region’s economic interests (private associations known as “expansion committees”). The underlying rationale remained centralisation and the economic development was led by the state.

The case of Portugal is particularly interesting in this respect because the creation of local authorities at the regional level on the mainland has always been met with wariness from municipalities, which are relatively large in size and small in number; these municipalities may fear that regional authorities will make them less autonomous, despite guarantees set out in the constitution.

In central and oriental Europe, regionalisation based on deconcentration is the dominant form. In some cases, the small size of the country explains this choice, although it is not necessarily the only reason.

In Estonia, the regional development policy has not led to a change in the country’s territorial organisation. In 1995, two central bodies were created: the Council of Regional Policy, for interministerial co‑ordination of policies concerning regional development, and the Estonian Regional Development Agency. State policy is implemented at the level of the 15 counties by a governor. In 2018, mergers of municipal authorities have replaced the old counties in the implementation of the EU cohesion policy.

A similar system operates in Lithuania, where the implementation of spatial planning and regional development policy is carried out by the governor at the level of higher administrative units (i.e. province/county); two regional development agencies were created in 1998 for Kaunas and Klaipeda respectively.

In Slovenia, regionalisation goes through centralised bodies (the regional development council, under the government and regional development agency) and the definition of regions of intervention.

Bulgaria and the Slovak Republic have divided their territories into regions. However, these regions remain districts of state administrative authorities that are in particular responsible for implementing state regional development policy. Bulgaria was divided into nine major economic regions from 1987, but in 1998 returned to 28 small regions (nevertheless considered as regions – “oblasts”), which is, in fact, the traditional administrative division of Bulgaria. However, this reform was spurred by economic arguments, such as communication networks and the country’s weak economic integration. The 1999 Act on regional development establishes a regional development council under a regional governor comprising municipal representatives, which advises on regional development issues. In the Slovak Republic, the 1996 reform divided the country into 8 regions, taking the number of administrative districts from 26 to 79. Although the constitution establishes territorial authorities at the higher level, for the moment the law only organises devolution at the regional level. However, it is worth noting that the regional administration offices are organised in the same way as the district administration offices, which themselves correspond to much older forms of administrative organisation that date back to the Austrian empire. The regional administration office is responsible for co‑ordinating local development missions common to state administration bodies and local authorities.

These observations lead to several general remarks. First, regionalisation through deconcentration does not necessarily correspond to situations in which local authorities (municipalities or counties) are weak. On the contrary, in obviously very different contexts, municipalities and local authorities in Bulgaria, England (United Kingdom) and Portugal are large and, proportionately dispose of quite significant means of action as in England. Second, regionalisation through deconcentration is centred on regional development, possibly associated with the deconcentration of other administrative functions. Third, deconcentration includes institutions or mechanisms that, to different degrees, involve local authorities in regional development policies, which nevertheless remain closely controlled by central government. Lastly, administrative regionalisation is in all cases (except in England and Sweden) a response to the implementation requirements of the EU.

Regionalisation through intermunicipal co-operation

Regionalisation can take place through existing local authorities when the functions that require developing are managed by local authorities that were initially established with other aims. This involves either extending their attributions and scope of action, or their co‑operation within a wider framework. This type of regionalisation is different from deconcentrated regionalisation in that the regionalisation takes place through decentralised institutions acting with their own powers. This case is actually very common in the European context. This type of regionalisation is notably typical in five European Union Member States, i.e. Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany and Ireland.

In Germany, regionalisation takes the form of co-operation between local authorities in the Länder. The first indication of local authorities’ regional expression is the regional associations of municipalities that can be found in five of the Länder. They generally cover a bigger territory than a Land’s government districts (although they coincide in Bavaria); they originate in historic co‑operation and operate in the domains of regional culture, health and social services. The regional federation of Palatinate (in Rhineland-Palatinate) is one of the most active. The second form of this regional expression is related to regional planning, which is totally or partially decentralised to local authorities in some Länder. In Baden-Wüttemberg, Bavaria, Lower Saxony and Rhineland-Palatinate, regional planning is entrusted to decentralised structures under the Land’s authority, i.e. the regional planning federation (districts [“Kreise”]) and towns with district status [“kreisfreie Städte”], the federation’s council being elected directly) or the district itself (Lower Saxony). However, beyond these relatively traditional institutions, local authorities and their representative organisations affirm, at both the federal and Land levels, their vocation to interconnect and represent regional interests, based on: i) their proximity to citizens; ii) the fact that a Land is a state in the federal system and that it does not, therefore, have a vocation to represent regional interests; iii) the fact that even in the EU’s Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics, Länder correspond to the NUTS 1 level, whereas regions correspond to NUTS 2.

The cases of Finland and Ireland correspond to regionalisation organised at the scale of the entire country based on co‑operation between local authorities. In Ireland, eight regional authorities were created in 1994; however, other functions related to regional development are still carried out by specialised agencies. Regional authorities cover the entire territory and are administrated by a council whose members are elected by counties and county boroughs. They co‑ordinate the planning programmes of local authorities and play a growing role in carrying out community programmes. In Finland, 20 regional councils have been established, over the entire territory, in application of the Act of 1994 on regional development. They are federations of municipalities created by the unanimous agreement of the municipalities that they comprise, and not a new local authority; the members of regional councils are elected by the municipal councils.

In the Netherlands, Portugal and Sweden, this type of regionalisation only concerns some parts of the territory. In Sweden, the 1995 Act, adopted following various reports and debates on the number and organisation of counties, organises regional co‑operation between the four counties of western Sweden; this co‑operation is administered by a council composed of representatives of municipal councils and county councils. In Portugal, two metropolitan areas, Lisbon and Porto, were created by the 1991 Act; they are local authorities in the sense set out in the constitution (Art. 236). The metropolitan area of Lisbon covers the perimeter of the region that was to have been created around Lisbon, except for two municipalities. The council of the metropolitan area is a product of the municipal councils of the regrouped towns; a liaison with the regional co‑ordination commission is ensured, mainly due to the participation of its chairperson and representatives from major public services concerned on the metropolitan area’s advisory committee. Lastly, in the Netherlands, the term region is traditionally used to designate an infra-provincial territorial frame, to organise devolved state services or intercommunal co‑operation services. In 1994, a law established the creation of seven urban regions based on the seven biggest urban areas in the country, capable of carrying through European-level development strategies.

The comparison of these different experiences leads us to make several observations. First, the most frequent case is when regionalisation is based on the creation of institutions that are common with local authorities; this illustrates the fact that the pre-existing constituencies of local authorities, at second and first levels, do not fully correspond to the scale of the regionalisation. Second, we can see that towns and intermunicipal co‑operation can also assume the functions of regionalisation and that cities, in particular, can find themselves at the centre of the regionalisation process, as seen in Germany, Hungary, the Netherlands and Portugal. Third, all institutions in which regionalisation is expressed through existing local authorities tend to preserve the rights and authority of the local authorities that they group together: their bodies result from them, their resources come from associated authorities and are relatively low, and their competencies are limited, in particular when the institutions of regionalisation are a form of intercommunal co‑operation (this is particularly the case in the metropolitan areas of Portugal, where the council only has a function of co‑ordinating municipalities in the urban area). To a certain extent, regionalisation through existing local authorities is a limited form of regionalisation, unless urban areas are endowed with strong institutions and sufficiently broad jurisdictions.

Regional decentralisation

Regional decentralisation designates the creation or substitution of a new elected authority at a higher level than that of existing local authorities and qualified as a region. The direct election of the regional councils is a key criterion of regional decentralisation. The region then takes on a specific institutional aspect, characterised by the application of the local authorities’ general regime. It thus forms a new category of elected territorial authority, with the same legal nature, but with a broader constituency that includes the existing local authorities and with competencies that are essentially focused on the economy or turned towards development. Although this type of region modifies the territorial organisation, it comes under the constitutional order of the unitary state.

France is the only EU member state that has fully implemented this regional concept. In application of the Act of 2 March 1982 and since the regional elections of 1986, France features 25 regions, 4 of them in its overseas territories. They benefit from the principle of free administration by local authorities, which was initially consecrated by the constitution for municipalities, departments and overseas territories. The principle of free administration is not in itself a regulatory power, except in the case of express legislation; nor does it involve the exercise of any legislative power. In fact, due to their jurisdictions, the regions wield less normative power than municipalities and départements, and in particular mayors. The regions cannot exercise or arrogate any authority over other local authorities on their territory.

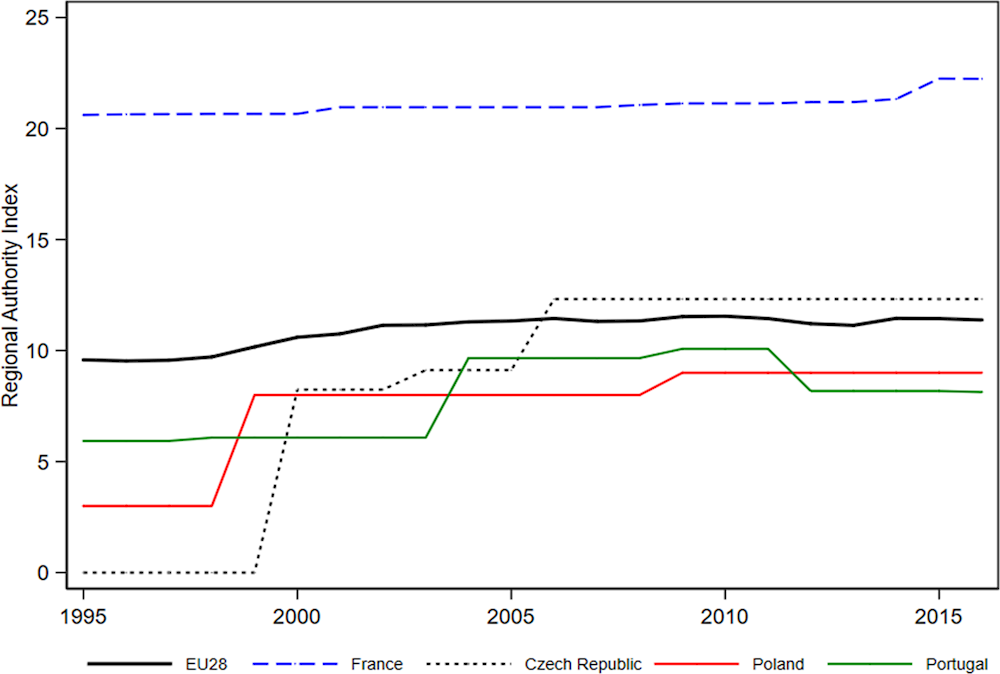

In Eastern Europe, two countries, the Czech Republic and Poland, have moved towards regional decentralisation (Figure 2.1). For the moment, only the Polish reform is in force, since autumn 1998; the Czech reform will not come into force until 2020 with regional council elections being scheduled for November. These two states introduce territorial authorities in the framework of unitary constitutions. Along with the re-establishment of the formerly abolished districts (powiat), Poland now has 16 voivodeships, instead of the 49 that had existed since 1975. Voivodeships are a type of territorial authority whose creation is permitted by the constitution, which nevertheless establishes jurisdiction to the benefit of municipalities. The state’s territorial administration is also organised at the level of the voivodeship under the authority of the voivode, who controls the territorial authorities. In the Czech Republic, the Constitutional Act of 1997 establishes the creation of “high-level territorial authorities” provided for in the constitution, in the form of 13 regions and the capital, Prague, placed at the same level. A devolved state administration could be maintained in the regions, but the district offices would be abolished.

All of the examples of regional decentralisation described above share numerous common traits, despite the heterogeneity of institutional contexts. The regions are always administered by councils elected by direct universal suffrage. In the case of France, the regional elections are held in direct universal suffrage using proportional representation lists. The election is held over two rounds, with majority bonus (25% of seats for the leading list). The lists must be gender-balanced by alternatively having a male candidate and a female candidate from the top to the bottom of the list. Only lists with as many candidates as available seats in every département of the region may compete. In the case of Sweden, the county/regional elections use proportional representation lists. In Sweden, they also use the proportional representation but the county/region election is held over one round. Seats are allocated amongst the Swedish political parties proportionally using a modified form of the Sainte-Laguë method. This modification creates a systematic preference in the mathematics behind seat distribution, favouring larger and medium-sized parties over smaller parties. At the core of it, the system remains intensely proportional, and thus a party which wins approximately 25% of the vote should win approximately 25% of the seats.

Figure 2.1. Regional Authority Index in the Czech Republic, France, Poland, Portugal and EU28

Sources: OECD elaboration based on Schakel, A. (2019[2]), Regional Authority Index (RAI), https://www.arjanschakel.nl/index.php/regional-authority-index (accessed on 15 May 2019); Marks, G. (2019[3]), Regional Authority, http://garymarks.web.unc.edu/data/regional-authority/ (accessed on 15 May 2019).

In practice, the regions in the decentralisation model have no normative power. They have extensive administrative jurisdictions related to key domains of economic and social life, but the law directs their policies towards regional development; this is most clearly apparent in the French and Polish laws. Regional decentralisation includes measures to protect the autonomy of existing local authorities: territorial authorities are prohibited from having control over each other in France; Poland features municipal competency in principle for affairs related to free territorial administration. The financial capacity of regions is clearly limited, compared to the political regionalisation or federal systems.

In many cases, a dual model prevails where the deconcentrated central government and regional decentralisation co-exist. However, depending on the country, the balance of power varies. In the French case, regional councils are gradually gaining power. In France, the deconcentration tends to focus on sovereign functions of the state (security, financial and legal controls) whereas in the Polish case, regional deconcentration remains much more influential in the implementation of territorial policies and strategies.

Political regionalisation (institutional regionalism)

This type of regionalisation is often put forward as a model due to the regional autonomy that it features and is often idealised. From a legal point of view, in comparison with regional decentralisation, the political regionalisation is characterised by several distinguishing aspects. These include the attribution of legislative power to a regional assembly, wider jurisdiction whose content is defined and guaranteed by the constitution, or at least by a constitutional-type text (note that in the United Kingdom, parliament’s sovereignty prevails) and, to exercise this jurisdiction, by an executive with the characteristics of a regional government. Unlike regional decentralisation, political regionalisation affects the structure of the state and modifies its constitution. Political regionalisation dominates the entire territorial organisation of the state in Belgium, Italy and Spain, although the first established a formally federal constitution in 1993. In other countries, such as Portugal and the United Kingdom, this type of regionalisation is partially applied. Nevertheless, political regionalisation is different from the federal state in several aspects, i.e. regions are not states, and the constitution in principle remains that of a unitary state; in Spain, some even fear that the conjunction of federalism and regionalism may threaten the integrity of the state.

Unlike federated states, political regionalisation does not result in a double constituent power: regions are overseen by a statute subject to a vote by the national parliament, although drawn up by the regional assembly and not by a constitution like federal states. While multiple forms of institutional co‑operation between states and regions exist, the latter do not participate in the exercise of national legislative power through their own representation. This asymmetry reflects the fact that political regionalisation results from recognition of specific ethnic, cultural and linguistic factors, in the name of which wider autonomy is granted to the regions in question and these specific features define their identity. In this aspect, political regionalisation is institutional regionalism. It can also produce an effect of dissemination or contagion that is likely to lead to a generalisation of regional organisation based on the same principles, usually with narrower autonomy. This is what occurred in Spain, where the autonomy regime was initially aimed at satisfying the demands of “historic” nationalities.

Insofar as political regionalisation affects the structure of the state, it is legitimate to see in it the source of a new type of state, different from both federated states and classic unitary states. This has sometimes been called also an “autonomic state”, defined by the absence of co-determination of everything by parties, and central control of the power of devolution (Pasquier, 2019[1]). According to this definition, unlike confederations, autonomic and federal states have in common the autonomy of parties but differ in their handling of relations with the centre. Historically, the “failed state control” of Belgium, Italy and Spain seems to correspond to resistance from the sidelines, which participated in different degrees in the Europe of City-States.

Regionalisation reforms in the EU countries: An overview

In the above discussion, regionalisation was defined as the process of an institutional handling of specific interests related to promoting a territory in a socio-economic perspective, but also taking on cultural and/or political dimensions and bringing about a change in the operations of intermediate institutions that formerly merely relayed the authority of central power. When understood in this way, regionalisation is a general trend in Europe, mainly related to economic developments, although less significant in some countries for reasons related to their size and history.

Regionalisation and regional institutions

Contrary to what we might expect, the most widespread type of regionalisation operates through existing local authorities. In the European Union, federalism and quasi-federalism are only fully in place in four states, i.e. Austria, Belgium, Germany and Spain, although in different forms. Regional autonomy is spurred by centrifugal trends in Belgium and Spain, but not in the Austrian and German Länder. In Italy, regionalism has inspired a political movement without reaching institutions. Two other countries feature political regionalisation on part of their territory, i.e. Portugal (its islands) and the United Kingdom (Scotland and Wales). Regional decentralisation, typical of France, is applied in Sweden; regionalisation through deconcentration is characteristic of Greece, Portugal, Sweden and the United Kingdom (England). In Sweden, though, deconcentrated central government regional units and regional governments with elected self-government and fiscal autonomy operate side by side.

In contrast, in eastern EU member states, regionalisation by federal units and political regionalisation are absent and deconcentrated regionalisation characterises six states in ten. Only two states have so far embarked on the path of regional decentralisation (the Czech Republic and Poland). Others have tried to do so but the reform was blocked after a failed referendum (Slovenia). Regionalisation by existing local authorities takes place in Romania and partially in Hungary. Others can be expected to move towards regional decentralisation or to increase the participation of existing local authorities in the regionalisation process, but the institutional regionalism path appears to be excluded.

EU cohesion policy has been a driving factor behind regionalisation reforms in the European Union. Countries have opted for reforms which affect their administrative organisation the least. Most often, the reforms are of two types: regionalisation through deconcentration (Greece until the creation of 13 regions in 2011, Portugal, Sweden), and regionalisation through existing local authorities (Denmark, Finland, Ireland, Sweden)

In Portugal, the abolition of districts is set out in the constitution but municipalities have always been against setting up “administrative regions” (which would have been territorial authorities), which they perceive as a threat to their autonomy (Nunes Silva, 2016[4]). In contrast, municipalities seem to have adjusted to their relations with state territorial departments and have developed co‑operation with them. The countries in which the jurisdiction and autonomy of local authorities are the most extensive (i.e. Denmark, Finland, the Netherlands and Sweden) either possess regional institutions that are reliable or dependent on local authorities, or simply have not created any.

Figure 2.2. Four main types of regionalisation implemented in the EU: From deconcentrated state administration to autonomous regions

Sources: OECD elaboration based on Pasquier, R. (2019[1]), “Decentralisation and regionalisation in Portugal: Lessons from international experience and recommendations”, Unpublished manuscript.

More generally, the impacts of regionalisation on existing local authorities have played a key role in the ultimate choices made. In most cases, solutions that might negatively affect the autonomy of authorities were not considered. Two reasons can be advanced. The first one is political. Local political leaders at the municipal or county levels are often opposed to the regionalisation process. The second one is constitutional. Local government’s status is traditionally protected by constitutions. The most typical cases are those of Portugal, Poland and Hungary. Even in France, this trend is illustrated not just by the maintenance of the départements, but by measures written into the law providing that no territorial authority can exercise control over another, or use any financial aid granted to this end. In the Netherlands, opposition from the inhabitants of Amsterdam and Rotterdam led to the failure of the 1994 reform aimed at instituting urban regions.

In countries with autonomous regions (political regionalisation), the constitution or national law confers the regions with a more or less extensive partial jurisdiction towards the local authorities on their territories, which includes at least some control of local authorities; in Scotland, devolution is almost total in this sense.

Regionalisation and identities

It is often maintained that the advantages of institutional systems with strong regions are that they are more likely than any other form of organisation to sustain cultural diversity and the expression of regional identities, to which individuals appear more attached as a backlash to the standardised lifestyles resulting from globalised markets and economies. According to Keating (2008[5]), industrialisation, national integration and cultural homogenisation are closely interdependent; with the loss of the nation-state’s legitimacy, the cultural, linguistic and ethnic differences that it reduced are being revived; the attraction of regionalism is more about culture than economics.

The identity aspect only characterises regionalisation in a small number of cases. Specific regional and linguistic features can be protected without establishing regions founded on this basis. When regionalisation operates only on ethnic bases, it may threaten the integrity of states. The results of regionalisation in such cases depend much on the implementation of regionalisation and the severity of conflicts.

These specific features, or these identities, are only at the foundations of regional institutions in a few cases. They are dominant in Belgium, but Flemish nationalism was the main driver of the constitutional evolution that took place in the country. Specific features are what shaped Spain’s “state of autonomies”, but they only concern three autonomous communities. In Italy, the situation is very different: the creation of regions was not a response to mobilisation from the sidelines; no regional languages exist apart from Francophone and Germanophone minorities in the north; the Italian regional state model is therefore very different from Spain’s “autonomic state”. Specific regional features led to the devolution of power to Scotland and Wales in the United Kingdom, but only in Wales does a significant share of the population speak a regional language. In Portugal, they only concern the Azores and Madeira Islands.

Opportunities and risks of regionalisation

Regions, and local authorities in general, clearly participate increasingly in the European integration process. EU policies themselves have contributed to this trend, insofar as the growth of structural funds and cohesion funds for beneficiary states has mobilised territorial authorities around the programming of funds and encouraged potential public and private beneficiaries to make their region-focused applications (Tömmel, 2011[6]; Loughlin, Hendriks and Lidström, 2010[7]). However, the diversity of institutions through which the expression of the trend for regionalisation evolves, makes it difficult to speak of regions in abstract terms for Europe as a whole.

Despite the above, debates on regions and regionalisation in Europe often adopt a normative position. Regionalisation is identified with regional autonomy, in the shape of federalism, political regionalisation or at least, and in its minimal form, regional decentralisation. It is credited with at least four merits: it fosters economic development, decentralisation, grassroots democracy and the respect for regional and local identities. Taking these different aspects, an evaluation of regionalisation calls for a more nuanced judgement.

Regionalisation can have very different implications for decentralisation: it can represent a form of decentralisation with respect to central government, but it can also generate centralisation at the regional level with respect to local authorities; this situation is particularly common in the case of political regionalisation and in federal states. For example, in the case of France, the local authorities (municipalities and départements) regularly denounce the risk of “regional centralisation” if the regional councils gain more powers. Rather than postulating that regionalisation encourages decentralisation, it is preferable to consider the protection of local authorities’ free administration rights in the definition of regional institutions. In several countries (Sweden but also France) the strong constitutional protection of local governments has led to weak regions compared to other “big” European states.

Concerning democracy, the question is probably misguided: transferring management or decision-making powers to the local level (town, municipality, neighbourhood) can encourage citizens’ participation and control due to the easier access of proximity; yet from a citizen’s point of view, the relationship with regional government is unlikely to be any different from his or her usual relationship with central government. Once they take on a certain importance, the nature of jurisdictions and the administrative means at play bring them closer. On the contrary, when it is considered necessary to exercise certain jurisdictions at a regional level because they need to interconnect with a regional interest in the making, regional institutions should be established with an elected representatives In other words, it is regionalisation that calls for democracy, not democracy that needs regionalisation for its development.

As for regional and local identities, although regionalisation has the means to satisfy them, this requires several qualifications. First, specific cultural and linguistic features could be respected without resorting to their territorialisation. It should not be forgotten that, although identities are volatile and hard to delimitate, institutions also contribute to building them.

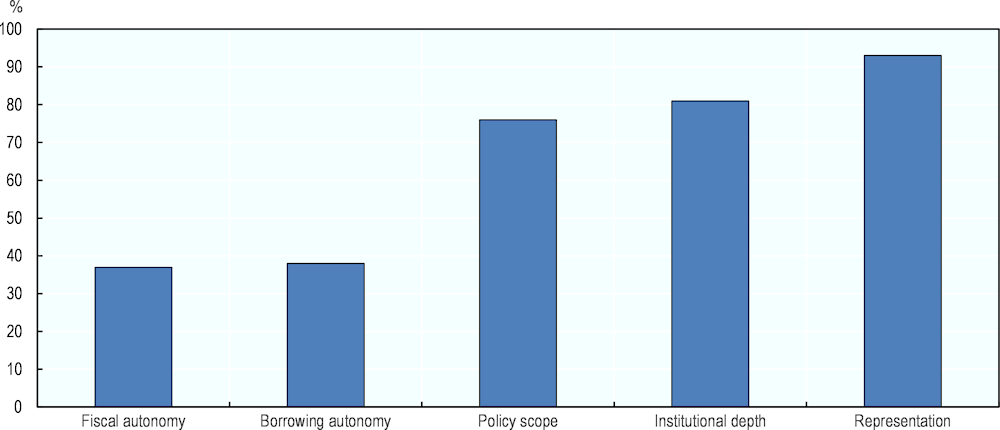

Figure 2.3. Summary of different policy measures that have strengthened regional self-rule in 81 countries

Source: Schakel, A. (2019[2]), Regional Authority Index (RAI), https://www.arjanschakel.nl/index.php/regional-authority-index (accessed on 15 May 2019).

Put another way, regionalisation cannot on its own produce any of the benefits mentioned above without making the effort to identify the conditions for regional and local development. This means in particular that needs related to economic development, spatial planning and the respect for regional identities require ad hoc solutions.

Regional reforms in Finland, France and Poland

This section focuses on regionalisation reforms in Finland, France and Poland as these three countries can provide some inspiration for Portugal. The French model could be of interest because both the Portuguese and French administrations are based on the so-called Napoleonic model. Moreover, during the past 30 years, France has carried out several regionalisation reforms, which can provide valuable information for Portugal. Poland provides a slightly different example. While the original motivation for decentralisation in Poland was largely political – and here Poland differs from France, Finland and Portugal – the process and the implementation of Polish decentralisation is very interesting for Portugal, especially the sequenced implementation of decentralisation and regionalisation reforms. Finnish experiences in regionalisation can be useful in the Portuguese context because, like Portugal, Finland has discussed establishing regions for many decades and the Finnish constitution now allows it. The previous Finnish government prepared the reform intensively between 2015 and 2019, and the current government, formed in May 2019, is determined to continue the work in order to create 18 regional councils.

One- or two-tier subnational government? The Finnish experience

While there is currently no regional government tier with elected self-government in Finland, the Finnish constitution does allow regional self-government. Article 121 of the constitution provides for self-government in an area larger than a municipality. The provision written in the law is vague and its reasoning is limited. The provision states only that such self-government “may be regulated by law”. The explanatory memorandum for Finnish Constitution states that the provision expresses “the possibility of organising larger municipalities, such as counties, in accordance with the principles of self-government”. The constitutional guarantees of regional self-government are however not as strong as for municipal self-government. It is also noteworthy that according to the law, regional self-government cannot be established by lower-level legislation or by intermunicipal agreements.

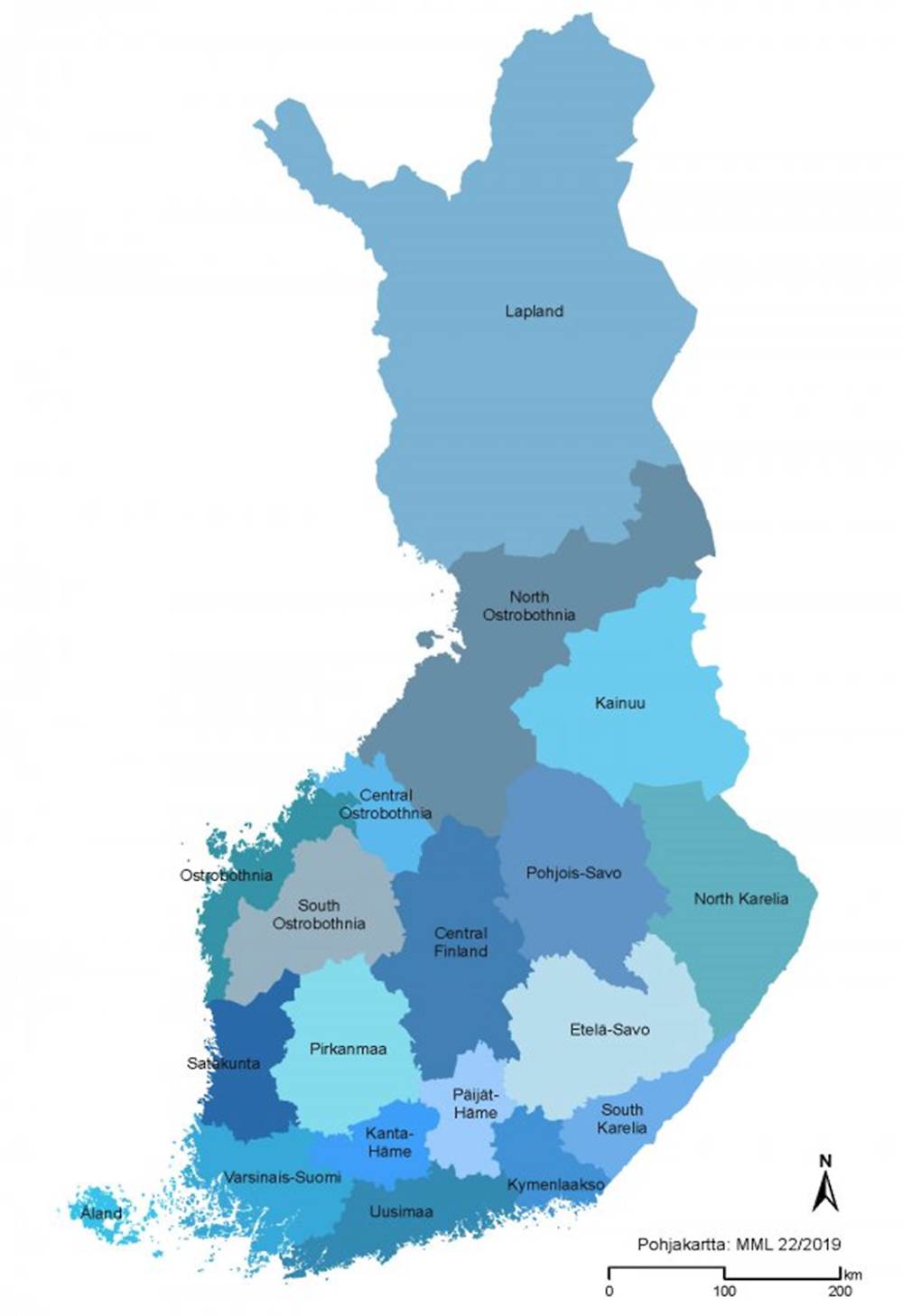

Currently, the political structure of Finland is officially two-folded, consisting of the national and local levels of government (Pesonen and Riihinen, 2018[8]). Regions, however, play a role in the Finnish politico-administrative system: they refer to geographical entities with a long historical background. Second, there are regional councils with specific tasks, but which lack independence as they are formed as joint municipal authorities (intermunicipal co-operation) and part of local governance.

The basic local government units are municipalities, currently numbering 311. They differ in size but have the same tasks. Municipalities are responsible for a wide range of services and intermunicipal co‑operation is therefore common especially among the smallest municipalities that would be too weak to arrange all services alone. Joint municipal efforts are numerous and may cover a large area. Intermunicipal co‑operation is voluntary except in specialised healthcare (hospitals) and regional development. In these services, municipalities are obliged to be members of co-operative units.

Regions as geographic units have a strong historical presence and, as objects of identification, including dialects, are parts of everyday narratives. In this sense, we can talk of nine regions, which are based on historical regions. The spread of Finnish language dialects approximately follows their borders. These historical regions are the following: Finland Proper, Laponia, Karelia, Ostrobothnia, Satakunta, Savonia, Tavastia, Uusimaa and Åland.

Figure 2.4. The Finnish regions (Maakunta)

Source: Regional Council of Southwest Finland (2019[9]), Regions of Finland, https://www.varsinais-suomi.fi/en/southwest-finland/regions-of-finland (accessed on 23 May 2019).

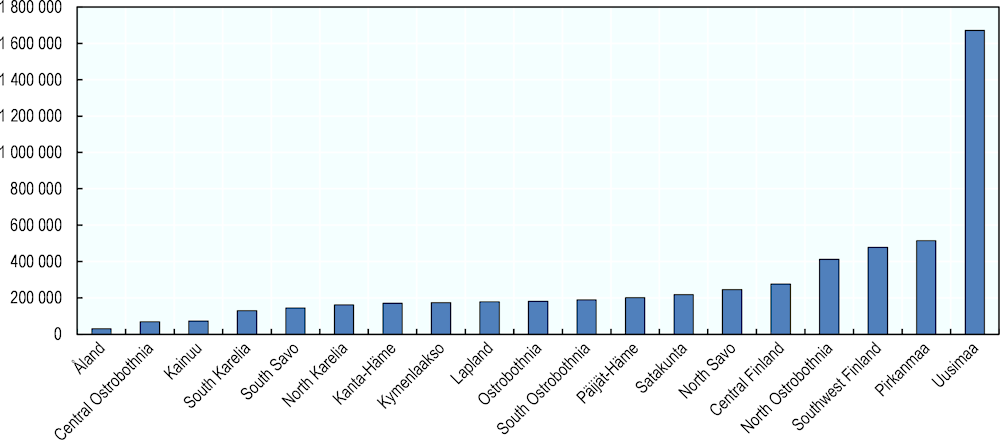

Figure 2.5. Population size of Finnish regions

Note: Population as of 1st January 2019.

Source: Statistics Finland (2019[10]), Population Statistics Finland, https://www.tilastokeskus.fi/tup/suoluk/suoluk_vaesto.html (accessed on 29 May 2019).

Before Finland joined the EU, the region-level territorial division was made of provinces (lääni, län) which were part of central government administration (deconcentrated central government functions). The provinces mainly implemented supervisory tasks of the ministries and regional policy was led by central government. The emergence of regional councils took place later on, with the advent of European Union membership (from 1995), when the regional councils were established in 1993 by merger of smaller intermunicipal organisations (Law on regional administration no. 1135/1993). This meant that the earlier municipal co‑operative organs, which mainly dealt with land-use planning, were combined with voluntary regional associations. As a result, the regional councils emerged. The regional councils are, as said, intermunicipal co-operative units.

There have been some changes in the number of regional councils, 19 at present. In other words, compared to the historical regions, the number is higher as some regions have been divided and new ones (i.e. Keski-Suomi) founded.

The Finnish regional councils are municipal co‑operative organs with rather limited tasks. A regional council is the region’s statutory joint municipal authority and every local authority must be a member of a regional council. The councils have two main functions laid down by law: i) regional development; and ii) regional land-use planning. The councils are the regions’ key international actors and are largely responsible for the EU Structural Funds programmes and their implementation.

The regional councils are a part of municipal governance. Each council (excluding Åland) has an assembly and a cabinet. The members of the assemblies are selected in connection to municipal general elections, held every fourth year, and the newly elected municipal councils select a number of councillors to the regional assembly. Hence the political colour of the regional assemblies reflects the municipal election results. The number of municipal representatives in a regional assembly depends on the size of the member municipalities and they meet only twice a year. In other words, the regional cabinet is more involved in the daily routines of the council and running its activities.

The councils work as statutory regional development and as regional land-use planning authorities, playing a key role in regional planning and in promoting the region’s interests. In order to organise co‑operation between regional councils, the country is divided into regional council partnership areas to facilitate the handling of major issues across regional boundaries. In other words, the regional councils resemble other intermunicipal organisations and are only indirectly accountable for the citizens.

The main tasks of the regional councils deal with land-use planning and co‑ordination of regional funds, especially EU funds. The tasks of economic development are not specifically defined. It is in fact more of a contextually determined task affected by the type of region, its economic structure and the interplay with municipalities, as they may also promote interests of their own in this area. This is basically a question of advocating the region’s well-being. One target of this activity is to ascertain that the national government acknowledges the region when planning, say, infrastructure investments, such as highways, airports and shopping malls. Co‑ordination is a central question in the Finnish regional policy. As with any organisation, regions also have to find the best ways to advance their goals, economic development, good land-use planning or implementation of EU funds.

Land-use planning in regional councils is part of the planning structure, in which line ministries, regional councils and local governments interact. Each of the 19 regions have a regional land-use plan. These fairly general plans set out medium- and long-term objectives for regional land-use patterns concerning issues that affect land-use planning in many municipalities. Regional land-use plans cover developments and issues that affect many municipalities where effective planning solutions cannot be developed at the local level only. Such developments include: new main roads, rail and energy developments, developments serving wider areas, such as popular recreational facilities or major water supply schemes, and development issues involving competition between municipalities. Since the beginning of 2016, the Finnish Ministry of Environment no longer approves regional land-use plans. This change was made to strengthen the regional councils’ autonomy in this respect. More broadly, the planning process of regional land-use plans involves close dialogue not only with ministries and municipalities but also with other stakeholders. Before being accepted, regional councils must open up their proposal for discussion and many statements are usually sent to the regional land-use plans by central government agencies, municipalities, pressure groups and private citizens.

As noted before, Finnish regional councils are not directly elected. Municipalities select the members of the assembly and the executive body. Regional councils represent the local voice and there have been some debates on how they can – in their current form – represent local views against the power of national regional agencies. Regional councils are not dealing with the everyday welfare services that are important to citizens. However, their visibility depends on the extent to which they manage to bring together the various regional actors and stakeholders and help bring forward regional interest. Successful policymaking requires a good ability to co‑operate with the local governments, other regions and the state agencies. Land-use planning, for example, is an area in which local government interests can contradict themselves. The national government also has an impact on decisions.

Out of the 19 regions, 2 differ from the rest. First, Kainuu, in the northwest, has reformed its entire welfare service system; however, this pilot was finished in 2012. Second, the autonomous county of the Åland Islands has a special status in the Finnish system.

Between 2005 and 2012, the Kainuu Region was applying a pilot model of regional governance. The aim of the self-government experiment was to gain experience of the effects of regional self-government on regional development work, basic services, citizen activity, as well as the relationship between the regional, central and municipal government. The act was valid from 1 June 2003 to 31 December 2012. During this experiment, the highest decision-making of the region was centralised into one organ, the joint authority of Kainuu Region. The distribution of tasks between region and municipality were reorganised. The joint authority of Kainuu Region was responsible for arranging practically all social and healthcare services, for example, together with upper secondary and vocational education. Within the joint authority, the highest decision-making body was the regional council, elected by the citizens of Kainuu.

According to the evaluations of the experiment (Jäntti, Airaksinen and Haveri, 2010[11]), the pilot project did not live up to expectations. The objective of the audit was to examine the implementation of the Kainuu regional self-government experiment and the impacts of the Kainuu development appropriation on the development of the region. The main question in the audit was whether the Kainuu regional self-government experiment had strengthened Kainuu’s economic and social development. Based on the results of the audit, the experiment had had only a minor impact on the development of the region and the objective of increasing the regional council’s role in regional development had not been fully implemented. The law for the experiment was accepted on the condition that, after the first phase of the experiment, municipalities had to unanimously support continuation. It seems that the results from the evaluation studies, which showed only modest positive impacts of the experiment, and the frustration of some municipalities in the region regarding their limited role in decision-making, resulted in a situation where it was no longer possible to get full support for the experiment. Therefore, in 2012, the Kainuu regional experiment was ended. After the experiment, tasks concerning regional development were transferred to the joint municipal authority, as were social and health services. Vocational education and upper secondary education, which had been provided by the regional government during the experiment, were transferred back to municipalities. While the model tested in Kainuu Region did not fulfil expectations, the experiences from this reform provided inspiration for subsequent regionalisation reform plans and efforts in Finland.

Finland is an example of regionalisation by existing local authorities (intermunicipal co-operation). Finnish regional councils are dealing with technical issues of land-use planning and administering EU Structural Fund appropriations. On the other hand, they represent the municipalities and more or less co‑ordinate economic and social development in the regions. They represent the regional voice in discussions with central government and the EU.

For the past four years, Finland has been preparing a reform to transform the current co-operative regional councils into regions with their own directly elected regional assembly. In Finland, the regionalisation has been mainly motivated by the healthcare and social services reform, which aimed to transfer health and social services from the current 295 mainland municipalities and 190 intermunicipal co-operative organisations to 18 counties. In addition to health and social services, the plan was to transfer 23 other tasks altogether to the established counties. This plan was however abandoned in April 2019, due to political disputes and led to the resignation of the government. While the previous government’s proposal to create 18 self-governing regions was not successful, the current government, formed in May 2019, has decided to continue the regionalisation reform, albeit with a slightly less ambitious approach. The plan is now to create 18 regional councils, with elected decision-makers and own budgets, mainly to provide health and social services in their areas.

French experiences on regionalisation

Based on vigorous cultural and political policies, the Jacobin ideal of the “nation-state”, according to which the nation is a product of the (democratic) state, has been seriously challenged these last decades (Pasquier, 2015[12]). The French state, like other European nation-states, has been confronted for some years with the dual pressure of European integration and the growing desire for autonomy on the part of subnational political communities. As a result of the decentralisation laws of 1982-83, the evolution of EU policies and, more generally, the increasing globalisation of the overall economic context, the central administrative organs of the French state have lost their monopoly on political initiative.

In the last few years, there have been important evolutions in the model of local government and central-local relations in France. These have included: the creation of the 15 or so metropolitan councils (métropoles) in France’s largest cities; a reform of the territorial map of the regions with the merger of regions; and enhanced central control over the financial autonomy of local authorities. There is a general consensus that the crisis of public finances, and the policies of administrative reform, which have attempted to address this crisis, have pushed French governments to attempt to reform the “mille-feuille” territorial structure. France has three levels of sub-national authority (communes, departments, régions). France has also developed strong intermunicipal co-operative mechanisms. The existence of some 34,900 small communes (40% of all such local government units in the whole EU) has come to symbolise the fragmentation of the French local government system.

Table 2.2. Subnational authorities in France, 2019

|

Type |

Number |

Functions |

|---|---|---|

|

Communes |

34 938 |

Varying services, including local plans, building permits, building and maintenance of primary schools, waste disposal, first port of administrative call, some welfare services |

|

Intercommunal public corporations (EPCI)* |

1 258 |

Permanent organisations in charge of intercommunal services such as fire-fighting, waste disposal, transport, economic development, some housing |

|

Departmental councils |

101 |

Social affairs, some secondary education (collèges), road building and maintenance, minimum income (RSA) |

|

Regional councils |

18 |

Economic development, some transport, infrastructures, state-region plans, some secondary education (lycées), training, research, some health |

* Établissement public de coopération intercommunale. It is noteworthy that the EPCI have tax-raising powers.

Source: Ministère de l’intérieur, Paris, 2019.

The financial crisis of 2008 and the new obligations it generated provided a new structure of opportunities for supporters of a reform of France’s territorial structures. Successive governments have used this context to announce “structural reforms”. However, it is difficult to modify the balance of power within the complex pattern of territorial administration, especially the relations between regions and départements (Pasquier, 2015[12]).

Though it is accused of being dysfunctional, the core features of the system established in the 1982-83 decentralisation reforms have resisted pressures for change. One core principle of the model is that of the “blocs de compétences”; the attribution of specific functions to different levels of local and regional government. In theory, this approach is coherent and logical: issues of proximity are, in theory, the policy province of the communes, welfare functions are largely reserved for the departmental councils, while economic development, transport and strategic planning are the responsibility of the regions, acting in co‑operation with the French state and the European Union. This French-style garden, of a neatly organised distribution of functions, has not withstood the reality of public policymaking in France’s localities and regions, however, where policy problems spill across levels. Moreover, the approach, which bears some resonance with the EU doctrine of subsidiarity, has run against the legally entrenched principle of the “free administration”, whereby local authorities can develop policies in any area they deem to be in the general interest.

Three decades of decentralisation have seemed to confirm Maurice Hauriou’s prophecy (Hauriou, 1927[13]; Pasquier, 2019[1]): “…with centralisation, the administrative garden was laid out in the French style, the rows neatly aligned and the trees planted and trimmed in an ordered manner. With decentralisation, it must be expected that this perfect construction be destroyed by the spontaneity of life”. If local authorities are in principle specialised in their functions, concentrating on particular areas of public policy, in reality they each intervene across the spectrum of public policy, because they each can claim a general type of democratic legitimacy and, until the 2015 “Nouvelle Organisation Territoriale de la République” (NOTRE) law, each had a “general administrative competency” that allowed them to intervene in any issue of territorial interest. Moreover, decentralisation conceives of the role of local and regional authorities as one of policy implementation; they have very few legislative or regulatory capacities.

In 2009-10, the government launched a major territorial reform which created the first metropolitan governments (in Nice, notably). The “Modernisation de l’action publique et affirmation des métropoles (MAPTAM)” law of 27 January 2014 re-established the general administrative competency clause that had been suppressed in the 2010 law; this allows local and regional authorities to develop policies in relation to any area deemed to be in the general interest. The MAPTAM law also conferred a new legal status on the French metropolitan councils in large cities, close in practice to the provisions of the Law of 16 December 2010 but with a more extensive outreach.

During the parliamentary debates of 2015, the government even abandoned the idea of transferring the responsibility for roads or lower secondary education from the departments to the regions. Certainly, the NOTRE Law enacted on 7 August 2015 strengthened the role of the regions in four main areas: the management of EU structural funds, transport (especially concerning schools and as interurban transfers), economic development and spatial planning. In these latter two fields, the regions henceforth are responsible for formulating five-year plans that, in theory at least, have to be respected by all other local authorities. They are recognised with a leadership role in the field of territorial economic development and planning. Not surprisingly, departmental and communal interests represent a major obstacle for regional and metropolitan reforms in France.

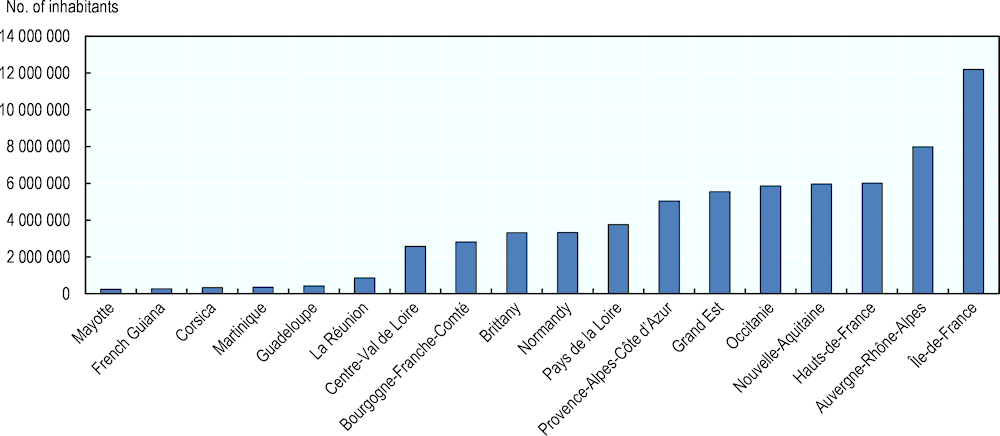

The third major reform of the Hollande presidency was the reform of the regional map. In the Law of 16 June 2015, a new map of the regions was produced, reducing their number from 26 to 17 (of which 12 in mainland France and Corsica and 4 overseas regions). Several regions were unchanged: Bretagne, Centre-Val de Loire, Corse, Pays de la Loire, Ile-de-France and Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur (PACA). All other regions were merged to create larger entities.

Figure 2.6. The new map of French regions (Law of 16 June 2015)

Source: INSEE.

Figure 2.7. Population size of French regions, 2017

Source: OECD (2017[14]), Regional Demography, Population (Large Regions TL2), https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=REGION_DEMOGR#.

Scalar forms of justification were to the fore in the territorial reform of 2015, which reduced the number of mainland (including Corsica) regions to 13 (in alignment with the European “norm” represented by the 16 German Länder). The redrawing of the regional map was justified in terms of size (the optimum size to succeed in a competitive European and world environment) and economy (economies of scale, avoiding duplication, rationalising back-office functions). In one interview carried out as part of the Trust and Transparency project, a Parti Socialiste (PS) deputy in the Ardèche department summed up the prevailing sentiment about the reform of the territorial map: “this was a political decision, motivated by a – contested – belief that size would allow economies of scale, as well as arming French regions with the necessary size to compete at the European level”. Size itself is misleading: the new Hauts-de-France region (the merged region of Nord/Pas-de-Calais and Picardy) has a population superior to that of Denmark and a landmass equivalent to that of Belgium, yet it has minor regulatory and no legislative powers and a limited budget. Arguments based on size were more prominent than those of restoring historical regions, as in the case of the UK (with Scotland and Wales) and Spain (Catalonia, the Basque Country, Galicia).

As part of a major cross-national project on trust and transparency in multilevel governance, a nationwide survey was carried out into attitudes to the French regions in general and the reform of the territorial map in particular (Cole and Pasquier, 2018[15]). The survey demonstrated quite clearly that French citizens show greater trust in two levels of government over the proposed alternatives: the city (for most routine matters of public policy) and the national government (for welfare provision, equality of treatment and national planning). Support for the intermediary levels of subnational government (13 regions and 96 departments) was sector and place-specific. Measures of trust in France’s regions varied according to place. If there is some sympathy for the region, this is more clearly affirmed in the case of the traditional region (Brittany) than in the merged regions of Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes (a fusion of two regions) or in the geographically vast New Aquitaine (a merger of three previously existing regions).

Regionalisation and decentralisation in Poland

Independence and democracy were restored in Poland in 1989. Even though the country borders were so often changed during the recent last two centuries, the notion of “territory” is deeply anchored in the national memory. This high value conferred to the central state, seen as a guarantee of the homogeneity of the national territory, explains the difficulties experienced by decentralisation.

In Eastern Europe, the policy of regionalisation became a clear political programme when, in 1997, the European Commission imposed the implementation of the “Acquis Communautaire” upon candidate countries (Da̧browski, 2008[16]). From this moment onward, it has been positioned as an unavoidable (necessary) condition for joining the EU. The so-called “Copenhagen criteria” formalised in 1993 have been the first step paving the way to accession by stressing the necessity to adopt democratic rules, market economy and respect of the rights of minorities.

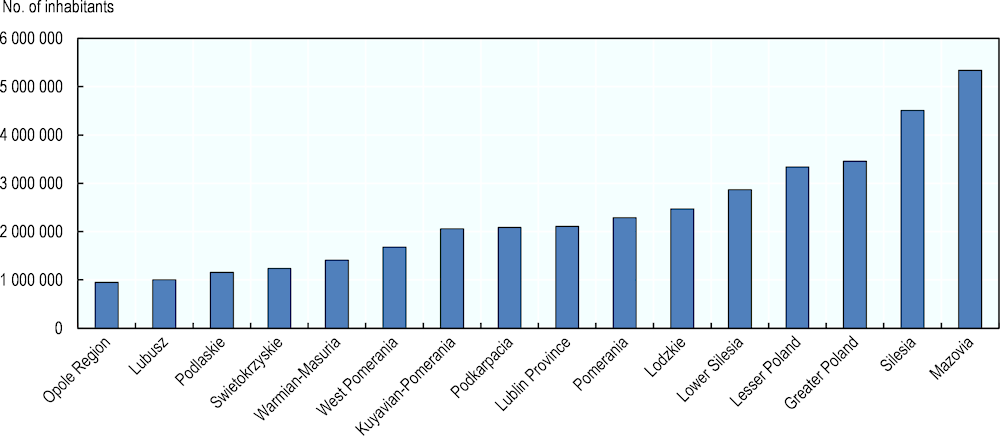

For these reasons, the projects aiming at modifying the “territorialisation” of public policy have been sensitive, provoking strong debates. The important law on local prerogatives, adopted in March 1990, was achieved by restoring the former subregional units destroyed by the communists. Such a law delivered more strategic capacities to the local municipalities, even though this dynamic was not accompanied by a transfer of funds. Important public discussion occurred and the core debate was about the number of regions. Most stakeholders understood the necessity of reducing the size of the regions to better restore the historical intermediary level, the “powiat” (county). Finally, when the law was passed in July 1998, 16 regions (voivodships) were created.

Currently, the Polish system of subnational government consists of three tiers. In addition to the 16 regions, there are also 380 counties (powiats) and 2 478 municipalities (gminas). The regions form the largest territorial division of administration in the country. Thirteen of them reshape more or less the former pre‑war “designs”, based on clear regional identities. Two other regions present a twin city. The smallest region by population, the region of Opole, was created mostly because of the presence of a German minority.

Figure 2.8. Population size of Polish regions (vojvodships), 2017

Source: OECD (2017[14]), Regional Demography, Population (Large Regions TL2), https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=REGION_DEMOGR#.

The administrative model has been inspired by the French one: in the face of the representative of the state (the voivode, i.e. prefect, in charge of the ex post control of the public funds), one finds the most important political figure, the marshal (the president of the region), elected by the regional assembly, whose deputies are elected by all the citizens of the region. The marshal organises the tasks and directs the ongoing matters of the voivodship and represents it externally. The Marshall’s Office, a self-governing organisation in the voivodship, is a body assisting the execution of tasks designated by the marshall and the voivodship’s elected members.

At the subregional level, one finds the “powiat”, led by the starosta (an old word for “chief”), elected by the local assembly, and which is more or less the district. The starosta takes decisions on individual matters in the field of local public administration. Powiats are allocated to towns with populations in excess of 100 000 residents, together with the towns that have ceased being capitals in the reformed voivodships. There are 380 powiats in Poland, that can be either land counties (314 units) or towns with powiat rights, i.e. urban powiats (66 units).

Under this level but independent from the two upper levels, one finds the gmina (municipality), which benefits from a free statute to develop its own plan of development. The gmina is responsible for all public matters of local importance. Its executive organs are the gmina council and the “wójt” (the mayor or town president). Poland counts 2 479 gminas, that can be urban (305 units), rural (1 566 units) or urban-rural (608 units).

What is remarkable in this new architecture is the capacity left to all the levels to be independent from the other. Such a feature complies to the very historical legacy of freedom of the administrative levels in this country but has been very often blamed for fostering paralysis and blockage. Indeed, the fact that the regional authority (the regional assembly and the marshall) cannot constrain its subregional levels has often impeded regional development. The poor situation of the transport system can be explained by this. On the other hand, for purposes of economic efficiency has forced the different subregional units (and particularly the gmina) to create some intercommunal links for some common projects.

Poland has been exemplary in the way it conducted its multilevel governance reforms for two main reasons. First, because of the public discussions held before the adoption of the law. These discussions have been an important period of deep democratic debate. All the participants have been invited to discuss and the arguments used have often been drawn from the national and local past. On this occasion, it was most interesting to see how the local people had a clear idea of their own regional interest and a clear memory of past regional administrative divisions. Second, because the law was passed expediently in July 1998, it triggered no definite disputes. This dynamic has reflected the maturity and the clear consciousness of the public authorities.

The argument of weakness at the Polish regional level is something of a self-fulfilling prophecy because the legislator has still not given decentralised regional levels the means for political and financial self-government. The particularly tight budgets of regional institutions and districts make it difficult to imagine that they will be able to co-finance structural funds, given the dependency of these institutions on financial support from the state. A general analysis of the budgets and margins for financial autonomy of Polish supra-national institutions (Bafoil, 2010[17]) shows that the 1998 administrative and territorial reform is, in the current state of affairs, only a smokescreen for decentralisation.

The central government has conferred significant jurisdictions to regions without, however, granting them the corresponding financial capacity: their level of own resources is low both in value (15 to 20 times lower than their homologues in the West) and volume (around 13% on average), and their tax margins are very low (1.5% of the income tax of physical entities, 0.5% of corporate tax). The majority of their funds comes from mostly pre-allocated central state endowments, while most of their expenditure is quasi-obligatory (health and education).

Summary of the country examples

While public expenditure is mostly centralised in France, local and regional authorities are very important actors in public investments (being responsible for about 57% of public investments). The French model of multilevel governance has seen several important changes during the past decades. These reforms include the creation of metropolitan councils (métropoles) in France’s largest cities, a merger reform of the regions and enhanced central fiscal control of local authorities. From the Portuguese aspect, the French case is an example of step-by-step process of regionalisation. The French experiences illustrate well the challenges to reform the existing multilevel governance, especially in a situation where there are two types of intermediate government, i.e. the départements and regions.

Poland restored its independence and democracy in 1989. Since then, Poland has implemented several decentralisation reforms. As a result, the current system of subnational government consists of three tiers: 16 regions (vojvodships), 380 counties (powiats) and 2 478 municipalities (gminas). Each level operates independently in the sense that each has its own assignments and levels of government are not in a hierarchical position with each other. This situation has forced the different subnational units and levels of subnational government to create intercommunal links for common projects such as major infrastructure investments with regionwide effects.

Although Poland adopted the laws on decentralisation fairly quickly in the early 1990s, reforms were based on intensive public discussions. The fact that everyone was encouraged to participate in the public debate on decentralisation promoted inclusiveness and feeling of ownership of the reforms among citizens. Subsequently, the reform plans were accepted and the implementation of the reforms sequenced, which fostered learning-by-doing and enabled revising plans if needed. Building capacity of the subnational governments to assume the new tasks has been a top priority in Poland. In this process, training and information activities, often organised using nongovernmental organisations, have had a key role in the reform implementation. Portugal could be inspired by the Polish experiences in the implementation of decentralisation and regionalisation reforms.

Finland has a single-tier subnational government, composed of 295 municipalities. There are also more than 300 joint municipal authorities, delivering services in health, education and social sectors. The responsibility for regional development and managing EU funds is also organised through intermunicipal co-operation. Municipalities are obliged by law to be members of 1 of the 18 regional joint municipal authorities. Municipalities nominate the regional council members and are responsible for funding of the regional councils. In addition to the regional councils, municipalities are obliged to belong to a joint municipal authority for specialised health services (so-called hospital districts). While obligatory co‑operation forms an important part of municipal service delivery, intermunicipal co-operation is organised mostly on a voluntary basis in Finland. Especially municipalities with small population and weak own-revenue bases have engaged in co-operative arrangements. Finnish experiences from intermunicipal co‑operation, in particular at the regional level, could provide an interesting example for Portugal.

The recent regional reform proposals by the Finnish government could provide another set of interesting experiences for Portugal. In order to better utilise scale economies and to prepare for increasing demand for public services due to an ageing population, the previous Finnish government (in office from mid 2015 until early 2019) began an ambitious process to establish a regional level government with extensive tasks. The government’s plan was to create 18 regional councils with elected decision-makers. According to the proposal, more than 20 tasks would have been transferred to regional councils from municipalities and central government, including all health and social services as well as tasks concerning regional development. The plan was also to abandon the deconcentrated central government offices and transfer their tasks to the regions or to a new central government agency. While the Bill put forth by the government suggested in the beginning that the regions should be financed with central government transfers and user fees, an inquiry into assigning taxation powers to regional councils was scheduled to follow.

The reform prepared in Finland was not only about regionalisation, however. An important component of the reform package was the privatisation of basic healthcare. This added to the complexity of the reform, especially from legal and administrative aspects. Due to various problems in tackling the various legal issues, the four-year term of the government turned out to be too short for passing the reform. Eventually, abandoning the reform plan led to resignation of government just before the end of the government’s term. The lessons from the Finnish reform process are numerous and we list here a few main observations. First, it seems clear that bundling several issues with the reform package was a mistake, as it led to serious legal problems, making it impossible to pass the reform proposal during one parliamentary term. Second, it seems that instead of being just the government’s project, the preparation of such a major reform would have benefitted from greater political preparation, by a parliamentary committee for example. Third, the reform should have been prepared more as a step-by-step process, instead of a “big bang” reform. This would have enabled experimentation and piloting before entering in full-scale reform.

The new government, nominated in May 2019, has announced that it will continue the regional reform and that 18 regional governments with elected councils will be formed. According to the government’s programme, the new regions will be in charge of health and social services, as well as fire and rescue services. At this stage, the regional development services will not be transferred from intermunicipal associations to regions. The deconcentrated central government services will not be abandoned either.

References

[17] Bafoil, F. (2010), Regionalization and Decentralization in a Comparative Perspective: Eastern Europe and Poland.

[15] Cole, A. and R. Pasquier (2018), “La fabrique des espaces régionaux en France. L’Etat contre les territoires?”, Berger-Levrault.

[16] Da̧browski, M. (2008), “Structural funds as a driver for institutional change in Poland”, Europe-Asia Studies, Vol. 60/2, pp. 227-248, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09668130701820101.

[13] Hauriou, M. (1927), Précis de droit administratif, Sirey, Paris.

[11] Jäntti, A., J. Airaksinen and A. Haveri (2010), Reveries – from free-falling to controlled adaptation (In Finnish, English abstract)..

[5] Keating, M. (2008), “Thirty years of territorial politics”, West European Politics, Vol. 31/1-2, pp. 60-81, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01402380701833723.

[7] Loughlin, J., F. Hendriks and A. Lidström (2010), The Oxford Handbook of Local and Regional Democracy in Europe.

[3] Marks, G. (2019), Regional Authority, http://garymarks.web.unc.edu/data/regional-authority/ (accessed on 15 May 2019).

[4] Nunes Silva, C. (2016), “The economic adjustment program impact on local government reform in Portugal”, in Numes Silva, C. and J. Buček (eds.), Fiscal Austerity and Innovation in Local Governance in Europe.

[14] OECD (2017), Regional Demography, Population (Large Regions TL2), OECD, Paris, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=REGION_DEMOGR#.

[1] Pasquier, R. (2019), “Decentralisation and regionalisation in Portugal: Lessons from international experience and recommendations”, Unpublished manuscript.

[12] Pasquier, R. (2015), Regional Governance and Power in France: The Dynamics of Political Space, Palgrave.

[8] Pesonen, P. and O. Riihinen (2018), Dynamic Finland: The Political System and the Welfare State, SKS Finnish Literature Society, http://dx.doi.org/10.21435/sfh.3.