Yasmin Ahmad

OECD Development Co-operation Directorate

Eleanor Carey

OECD Development Co-operation Directorate

Yasmin Ahmad

OECD Development Co-operation Directorate

Eleanor Carey

OECD Development Co-operation Directorate

Overall official development assistance volumes increased to their highest level ever in 2020, even as global GDP fell dramatically. This chapter explores what drove the rise in official development assistance in 2020, the implications for development co-operation and trends to watch in 2021 including vaccines, climate and debt.

Please note that all data and calculations in this chapter are correct as of 09 June 2021. Any announcements of new funding commitments to vehicles such as the WHO’s ACT-A made after that date are not reflected in these data.

The authors are grateful to the following people for contributions and feedback: Aussama Bejraoui, Julia Benn, Marisa Berbegal Ibanez, Emily Bosch, John Egan, Valerie Gaveau, Mags Gaynor, Martin Kessler, Anita King, Rahul Malhotra, Ida Mc Donnell, Nestor Pelecha Aigues, Santhosh Persaud, and Haje Schutte.

Note: USD 11.7 trillion fiscal response measures to COVID-19 in DAC countries refers to “above the line measures” and “liquidity support” of DAC countries as reported by the IMF in January 2021. The total figure for fiscal measures in response to COVID-19 for all countries reported by the IMF in April 2021 was USD 16 trillion.

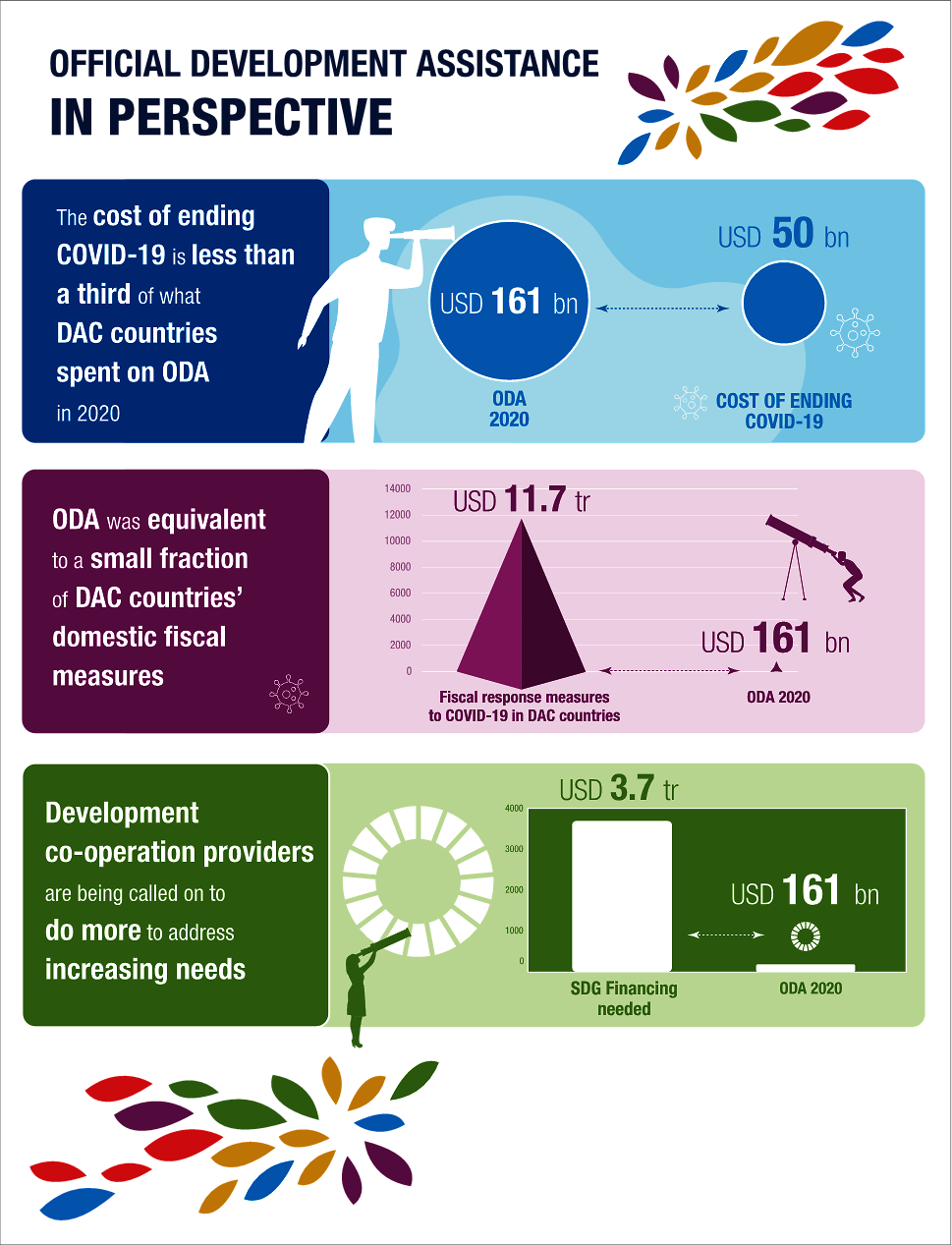

Official development assistance (ODA) increased to its highest level ever in 2020, reaching USD 161 billion.1 The increase was driven in part by OECD-DAC members’ response to the COVID-19 pandemic, even as global gross domestic product (GDP)2 and other financing fell. Beneath the top-line number, however, OECD-DAC data show growing gaps between the amount of ODA that members provided, the relative size of ODA compared to domestic fiscal responses to COVID-19 and the income groups of countries that benefit the most from current ODA support. These gaps are combined with widening disparity among countries in access to COVID-19 vaccines and other kinds of financial support. Looking ahead, all countries will grapple with immediate health, security and economic needs, as well as building global resilience to health and climate threats and working towards the universally agreed Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030.

Not all OECD-DAC members increased their ODA contributions in 2020. The rise in some countries’ contributions offset cuts to ODA from other members. The proportion of ODA provided as loans also increased, along with tougher lending terms. Preliminary 2020 figures suggest that ODA increases benefited middle-income countries the most. Development Assistance Committee (DAC) members are also facing an imperative to co-ordinate policies and financing for global public goods to boost health and climate resilience.

Among the things that could spur support for ODA contributions in 2021 are increasing demand for support for the health response and economic and social recovery from the crisis beyond OECD countries. Increased activity in some categories of spending to support the COVID-19 health response, particularly to support global vaccination, qualify as ODA, as will some debt-relief efforts and contributions to other new financial instruments. Several high-level moments on the international calendar centred on global climate and development goals may focus attention on the estimated USD 3.7 trillion funding gap to achieve the SDGs by 2030. While some OECD countries have signalled that their ODA budgets may decrease in 2021 as they grapple with their own pandemic and economic recovery efforts, innovative methods to smooth fluctuations could be deployed. Overall, DAC members and other official development co-operation providers are being called upon to do more to address the acute and compounding challenges facing the global community, and disproportionately impacting those left furthest behind.

ODA has risen in a year that saw all other major flows of external income for developing countries – such as foreign direct investment, trade and remittances – decline due to the COVID-19 pandemic, though some flows such as remittances have not fallen as dramatically as predicted (World Bank, 2021[1]). This is against the backdrop of rising debt risks, strained domestic resources, stagnating global growth, protracted conflicts and climate-related crises (OECD, 2021[2]). Over its 60-year history, ODA has been the most stable source of external finance for developing countries and is not necessarily tied to gross national income (GNI). An analysis of 60 years of ODA data found that 2000-10 was the most generous decade for ODA, driven by commitments surrounding the Millennium Development Goals and subsequent high-level meetings, rather than increases in GDP (Ahmad et al., 2020[3]). Annual average OECD GDP growth rates since the 1960s fell from over 5% to around 2%, hovering at this level since the early 2000s. By contrast, ODA growth increased until the 1990s, when it fell, only to rebound to its highest growth levels in the 2000s.

Despite a decline in growth for all OECD countries in 2020 (on average GDP fell by more than 5%), some countries protected and increased ODA budgets, and net ODA flows rose by 7%; other countries saw ODA growth fall dramatically (OECD, 2021[4]) (ODA is not dependent on GDP growth). There is not an automatic relationship between GDP and ODA levels. Initial estimates indicate that DAC countries disbursed USD 12 billion in 2020 for COVID-19 related activities.3 In total, USD 3.2 billion went to the health sector, indicating that the majority went to support other sectors of partner countries’ economies and societies.

Year-on-year ODA and GDP, % change, 2019-20

In 2020, total ODA volume rose in more than half of DAC member countries (16), with some substantially increasing their budgets to support developing countries to face the pandemic. Large increases in volume were noted in Canada, France, Germany, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland and the United States. Other providers that also increased their ODA volumes in 2020 included Bulgaria, Croatia, Latvia, Malta and Romania.

Year-on-year ODA volume changes in constant USD million, 2019-20

Although ODA rose in 16 DAC member countries, it fell in 13 others, with the largest drops in Australia, Italy, Korea and the United Kingdom (OECD, 2021[4]). Countries that increased their ODA represented three‑quarters of total ODA combined, thus offsetting drops in other countries. If ODA had remained stable in countries where it fell in 2020 (i.e. if they had maintained their 2019 ODA levels), then ODA could have increased by 5.7% in 2020, to reach USD 164 billion.

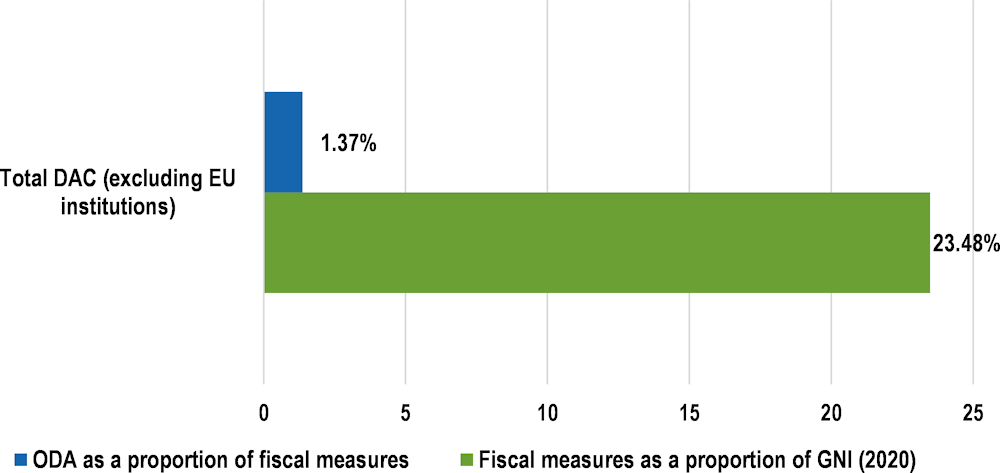

Financing the response and recovery to COVID-19 across the world has been widely unequal. The fiscal response to COVID-19 was, on average, seven times smaller in low-income countries than it was in advanced economies: in advanced economies, debt-to-GDP ratios were allowed to rise by 20‑30 percentage points of GDP (OECD, 2021[2]). From January 2020 to January 2021, governments globally had mobilised USD 13 859 billion in fiscal measures.4 DAC members’ stimulus spending accounted for 84.7% of the global total (USD 11.7 trillion) and was equivalent to 23.48% of their collective GNI (table DAC members’ fiscal measures, ODA as a proportion of GNI and fiscal measures, and ODA year-on-year growth rate in Annex. Further statistical tables and figure ODA was equivalent to a small fraction of DAC countries’ domestic fiscal measures). ODA from DAC member countries combined (excluding EU institutions) was equivalent to 1.37% of DAC countries’ fiscal measures (table DAC members’ fiscal measures, ODA as a proportion of GNI and fiscal measures, and ODA year-on-year growth rate in Annex. Further statistical tables and figure ODA was equivalent to a small fraction of DAC countries’ domestic fiscal measures). The development co‑operation community has been called on to increase the proportion of fiscal measures geared towards ODA (OECD, 2021[2]).

January 2020-January 2021

Notes: DAC: Development Assistance Committee. ODA: official development assistance. GNI: gross national income. For a breakdown by DAC country, see table DAC members’ fiscal measures, ODA as a proportion of GNI and fiscal measures, and ODA year-on-year growth rate in Annex. Further statistical tables.

Source: Author’s calculations based on IMF (2021[7]).

In terms of channels of spending, DAC members’ bilateral projects and programmes increased by 8% (with budget support increasing by 131%), multilateral channels increased by 9% (with contributions to organisations other than the United Nations, the World Bank and regional development banks increasing by 68%), and humanitarian aid increased by 6% from 2019 to 20205 (Components of ODA, 2000-20). These findings suggest that bilateral and multilateral spending both had an important role to play in addressing the crisis. The increase in urgent humanitarian appeals that were issued in 2020 were not met by a proportionate increase in commitments, and many went unfunded or underfunded (OECD, 2020[8]).

Constant 2019 USD billion

The DAC recognised the impact of the crisis on countries the most in need, including fragile contexts and conflict-affected states as well as least developed countries (LDCs)6, and reaffirmed the important contribution of ODA to the immediate health and economic crises and longer term sustainable development, particularly in the LDCs (OECD, 2020[9]). The context of a global crisis, in which all countries are affected and countries have varying capacities to respond depending on the nature of the crisis, has called into question previous categorisations of “eligibility” and “need” and the way in which they are applied. Some flexibility was shown in 2020. For example, the DAC agreed to exceptionally delay the graduation of Antigua and Barbuda, Palau, and Panama from the DAC List of ODA Recipients until 1 January 2022, ensuring that these countries remained eligible to receive ODA support (OECD, 2020[10]).

Preliminary data show that net bilateral aid flows from DAC members to the LDCs in 2020 increased by 1.8%, to USD 34 billion.7 However, low-income countries (LICs) experienced an overall drop in net bilateral ODA (-3.5%)8 while lower middle-income countries saw an increase of 6.9% and upper middle‑income countries saw an increase of 36.1%. ODA to sub-Saharan Africa decreased (‑1%).

While this analysis shows that bilateral support to the LICs dropped in 2020, analysis of net ODA receipts (including both bilateral and multilateral flows) of developing countries between 2015 and 2019 (Developing countries’ net ODA receipts) reveals an overall net ODA increase to the LICs of 29%. The main driver of this increase is multilateral organisations (from which ODA to the LICs increased by 28%) compared to bilateral flows (which increased by 7%). By contrast, net ODA fell in lower and upper middle-income countries (by 2% and 14% respectively). Again, the fall is driven by reduced flows from multilateral agencies as DAC providers increased their ODA (by 7% and 3% respectively). This analysis highlights that both bilateral and multilateral providers play an important role in the provision and channelling of ODA across income groups and that the dip in bilateral flows to the LICs in 2020 referred to above (-3.5%) should be considered as part of a longer term trend of rising resources to the LICs, with a shift in emphasis towards multilateral channels.

Percentage change between 2015 and 2019

|

|

All developing countries |

Low-income countries |

Lower middle-income countries |

Upper middle-income countries |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

All official providers |

8 |

29 |

-2 |

-14 |

|

of which DAC countries |

6 |

7 |

7 |

3 |

|

of which multilateral agencies |

3 |

28 |

-6 |

-46 |

Official development assistance (ODA) flows are provided by official agencies and are concessional (i.e. consisting of grants and soft loans) (OECD, 2021[11]). Starting in 2018, the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) began to count only the grant equivalent of loans as ODA. The more generous (or concessional) the loan, the higher the ODA value (OECD, n.d.[12]).

During the transition period to the grant-equivalent system, from 2015 to 2017 and beyond to 2019, DAC members did not, in aggregate, change the concessionality levels of their ODA loans (Average grant element of all ODA loans, 2015-19). However, though the average grant element rose by 1%, a number of members applied stricter lending terms over the period (Average grant element of all ODA loans, 2015-19). Loans provided by these countries account for 9% of the total ODA loans provided in 2019.

Interest rates and maturity periods (Characteristics of 2019 ODA loans by loan provider) of loans help explain the evolution of the grant element, with quite some fluctuation across DAC countries:

a. Interest rates: the DAC average increased throughout the transition period (from 1.0% in 2015 to 1.2% in 2017) then decreased in 2018 (1.1%). All members, with the exception of Germany, applied higher interest rates in 2018 than in 2015. However, in 2019, the average interest rate fell back to 1% for ODA loans, although five loan-giving countries charged rates above the DAC average.

b. Maturity periods: the DAC average slightly decreased during the transition period, from 26 years in 2015 to 25 years in 2017. However, in 2018, the average reached 28 years, but fell to 25 years in 2019; 6 countries were below the DAC average.

Taking a snapshot of the years 2015 and 2019 would give the appearance that the average grant element rose, interest rates held steady at 1% and maturity periods decreased by just one year, from 26 to 25 years. However, looking more closely at the data reveals fluctuations in the intervening years and among DAC members. These detailed trends are important to take into account, as small changes can have a significant impact on recipient countries.

Bilateral sovereign loans by DAC countries increased by 28.3% in 2020 from 2019 (including EU institutions, sovereign lending increased by 38.7%). As lending is calculated on a grant-equivalent basis, this would suggest that the face value of loans increased substantially. A little over half (i.e. 52%) of the increase in total ODA in 2020 is attributed to the increase in sovereign lending. Some of this increase is also due to the fact that some countries provided support for COVID-19 relief through loans as well. The countries that recorded the highest increases in 2020 in real terms of sovereign loans on a grant-equivalent basis were France (63%), Germany (69%), Italy (55%), Japan (11%) and Portugal (143%). Sovereign lending by EU institutions increased as well (136%) (OECD, 2021[4]).

Twenty-two per cent of gross bilateral ODA by DAC members was provided in the form of non-grants (loans and equity investments), up from a level which hovered around 17% in previous years. For some countries, the share of bilateral sovereign loans represented more than a quarter of their bilateral ODA: Italy (27%), Korea (40%) and the EU institutions (30%). For others it represented about a half or more: France (56%), Japan (68%) and the Slovak Republic (49%). Loans play a valuable role in development co‑operation. For example, Japan has a tradition of extending highly concessional loans compared to other creditors, offers preferential terms for priority sectors and takes great care to assess the debt sustainability of potential recipients (OECD, 2020[13]).

The rise in bilateral lending appears to be concentrated on middle-income countries in 2020. The increase in bilateral lending and trends for middle-income countries could imply that part of the increase in ODA in 2020 is for loans to middle-income countries. Between 2015 and 2019, gross bilateral lending to middle‑income countries rose by 11% in real terms. Given the significant decline of all private flows in 2020, concessional lending was an important counter-cyclical source of financing for countries. While remittances, foreign direct investment, portfolio investments and other investments did not fall as drastically as forecasts in 2020 suggested, the decline nevertheless created an urgent need for countries to access finance. Given the high debt levels that many countries entered the pandemic with (World Bank and IMF, 2021[14]), concessional borrowing emerged as an appropriate response, as the cost of market financing would have driven debt levels even higher.

Although the grant-equivalent system was expected to incentivise lending on highly concessional terms to the LDCs,9 on average, the terms of loans to the LDCs have hardened since 2015, indicating that this change has not had the incentivising effect intended, as others have highlighted (Ritchie, 2021[15]). The average grant element of ODA loans to the LDCs steadily decreased, from 78% in 2015 to 70% in 2019. This is explained by an increase in interest rates (from 0.34% in 2015 to 0.80% in 2019) and shorter maturity periods (from 35.7 years in 2015 to 28.3 years in 2019) (Characteristics of ODA loans to least developed countries). Between 2018 and 2019, several countries also provided less generous loan conditions (grant elements) to the LDCs: Germany (from 60% to 53%), Korea (89% to 86%), Poland (from 82% to 74%) and Portugal (from 51% to 49%).

|

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Average grant element (new) |

78% |

75% |

75% |

73% |

70% |

|

Average grant element (old) |

81% |

78% |

78% |

77% |

73% |

|

Maturity period (years) |

35.7 |

33.4 |

32.6 |

32.0 |

28.3 |

|

Interest rate |

0.34% |

0.49% |

0.59% |

0.67% |

0.80% |

Note: Calculated using a 10% discount rate (“old” cash-flow method) and discount rates differentiated by income group (9%, 7% and 6% – “new” grant-equivalent method).

Increasing non-concessionality (i.e. loans with higher interest rates or shorter maturity periods) has also been observed in the multilateral space. In recent years, outflows from multilateral institutions have been steadily increasing, largely driven by the activity of the main multilateral development banks, with non‑concessional flows outpacing concessional flows from multilaterals from 2016 to 2018 (OECD, 2020[16]). This is significant given the shift in emphasis towards multilaterals as a channel for financing to the LICs observed above.

The COVID-19 crisis has shown that investments in global resilience to address shared threats are of paramount importance. Health security and achieving a stable climate are currently high on the political agenda, but other looming issues also underline the need for more robust mechanisms for co-ordinating policies and financing for global public goods. Though DAC members have contributed in various ways to global public goods over the years (DAC members play an important role in providing and protecting global public goods), there is an outstanding need to clarify the role of public finance and find new ways to tackle shared threats (OECD, 2020[8]). Pioneering measurement frameworks and revised methods of working with and through the multilateral system may offer ways forward.

OECD-DAC peer reviews consistently show that Development Assistance Committee (DAC) members make substantial efforts to put key global public goods issues on the agenda, help craft and promote international commitments and agreements, and take action to promote their implementation. Strategies include:

Norm-setting and upholding international frameworks: OECD members co-facilitate and host key international processes, ensure the functioning of global frameworks of high relevance for developing countries and mobilise resources (official development assistance [ODA] and non‑ODA) to enable developing countries to take action in line with international frameworks. They have also strategically used presidencies and chairing roles in international groups and organisations strategically for progress towards sustainable development.

Championing collaborative action despite political frictions: When the United States’ previous administration temporarily withdrew from the Paris Agreement, Germany’s G20 presidency led to a clear statement of 19 leaders that the Paris Agreement is irreversible. Disagreement over migration led to significant tensions within the European Union (EU). However, the EU and most member states actively supported the Global Compact for Migration and the Global Compact on Refugees, and advanced international debate on migration in international fora.

Leveraging domestic experience: DAC members have shown leadership in various global public goods issues in line with their domestic experience and expertise. Sweden’s Strategy to Combat Antibiotic Resistance, for example, relies on the co-ordinated efforts of 25 government agencies and other organisations. It combines domestic action with international engagement across a broad range of multilateral institutions.

Global efforts are most effective when accompanied by coherent domestic policy. While DAC members have affirmed their commitment to take account of how their own domestic policies affect developing countries (OECD, 2019[17]), DAC peer reviews regularly identify domestic policies that do not adequately reflect the objectives of development co-operation. Strategies, processes and reporting requirements connected to the 2030 Agenda are helping to address some coherence issues. Action on issues such as a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, the protection of biodiversity, promoting responsible business conduct, enhancing tax regimes and fighting corruption, and controlling arms exports are also key steps forward. However, findings from evaluations and studies on coherence issues identified room for improvement, for example making line ministries responsible for the global effects of their policies and enabling regular meaningful debate among key stakeholders.

Source: OECD (n.d.[18]).

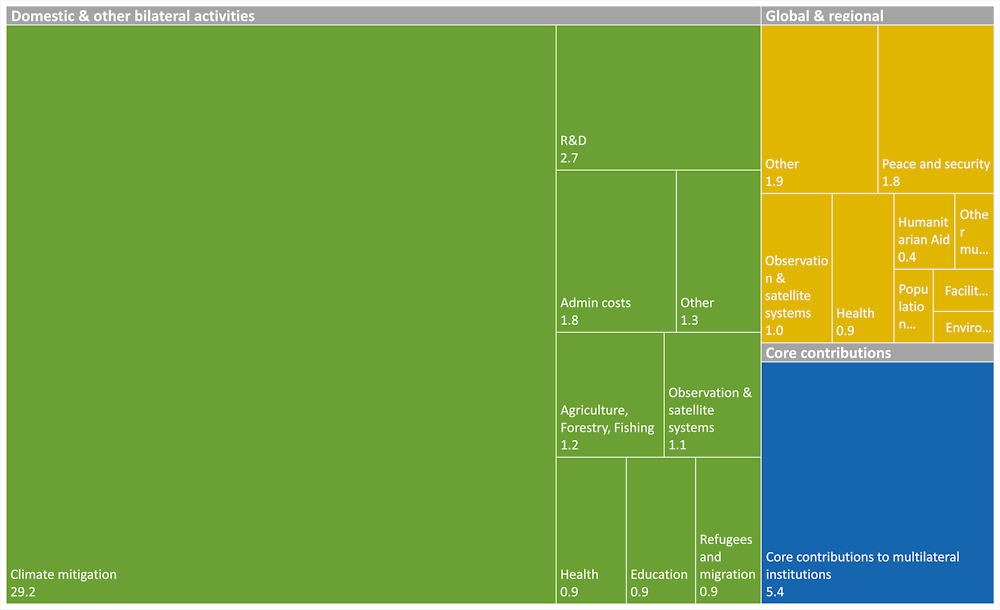

Recent evolutions in measurement frameworks can help to reveal areas of concentration, as well as gaps in funding for global resilience. 2020 saw the first official data collection from 90 providers for a new international statistical measure, Total Official Support for Sustainable Development (TOSSD). This measure provides a complete picture of all official resources and private finance mobilised by official interventions in support of sustainable development and the SDGs. Consisting of two pillars,10 data on 2019 flows estimated a total of USD 296 billion in official financing. Of this, USD 226 billion was classified as cross-border flows or Pillar I and USD 70 billion as Pillar II, contributions to international public goods. In addition, USD 47 billion of private finance mobilised by official interventions was captured (OECD, 2021[19]). Additional official financing captured under Pillar II11 focused on climate mitigation, core contributions to multilateral institutions, and research and development (Additional official financing for international public goods captured in the TOSSD Pillar II).

Disbursements, billion USD

Notes: Additional resources compared to OECD statistics on development finance. Includes USD 17 billion from the European Investment Bank on a commitment basis. Data should be regarded as an underestimate of the actual volume of official financing for international public goods, as only a limited number of providers were able to report on this. Truncated labels in global and regional section read (left to right): Observation and satellite systems (1.0); Health (0.9); Humanitarian aid (0.4); Other multilateral (0.3); Population Policies/Programmes & Reproductive Health (0.3); Facilitation of migration (0.2); Environmental Protection (0.2).

Source: Calculations performed by the TOSSD Secretariat, reproducible from OECD (2021[19]).

As demonstrated by Additional official financing for international public goods captured in the TOSSD Pillar II, the TOSSD Pillar II can shed light on financing to protect the environment by taking into account the domestic efforts of all countries as providers of international public goods, in addition to the cross-border financing in developing countries tracked in Pillar I. For example, Costa Rica, the OECD’s newest member country, is a global biodiversity hotspot where an estimated 6% of all known species can be found. Costa Rica builds global resilience by tackling one of the root causes of new zoonotic diseases: biodiversity loss and ecosystem degradation (WHO and CBD Secretariat, 2020[20]). According to TOSSD data, Costa Rica has committed USD 59 million of its domestic budget to protect biodiversity in conservation areas within the country.

Alongside environmental protection, delivering health security has become a top global priority. TOSSD contributions to the health sector in 2019 amounted to approximately USD 25 billion (just over 8% of total TOSSD contributions recorded for the year), with USD 3.4 billion coming from Pillar II contributions and USD 21.5 billion from Pillar I contributions. The majority of Pillar II financing went to medical research (35%), as well as health policy and infectious disease control at the level of multilateral institutions (38%). Pillar I financing targeted the control of infectious diseases in developing countries (45% including HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted diseases, malaria, tuberculosis, and other infectious diseases) and basic healthcare (14%). Given recent calls to scale up financing for pandemic preparedness and the global health security system to a level of USD 5-10 billion per year (Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness & Response, 2021[21]), the fuller picture of financing which TOSSD can provide will be advantageous to track the mobilisation and dispersion of funds in this area.

The increasing need to address global issues and the less-than-optimum performance of the international system to respond to the COVID-19 crisis has raised questions about needed reforms to mitigate and tackle shared threats, most notably climate change (OECD, 2020[8]). Multilateral organisations have played a key role in financing the immediate response to COVID-19 and reaching consensus on a range of issues. Moreover, in recent years, a rising share of ODA has been allocated through the multilateral system while at the same time the increase in the number of multilateral organisations and funding vehicles has led to some fragmentation and countries increasingly pursuing “à la carte” multilateralism (OECD, 2020[16]), with an associated rise in the practice of earmarking funds.12 For development co‑operation actors, and in particular for DAC members as the largest donors to the multilateral system, learning lessons from this experience to strengthen multilateral organisations and their engagement with these entities will be key to effectively tackling shared threats. While a single definition of good practice in relation to multilateral engagement is challenging given the diversity of multilateral institutions and the different systems, rationale and capacities of each development co-operation provider, some good practices include acting on reform commitments and prioritising the use of existing channels and structures. The forthcoming OECD Tools, Insights and Practices (TIPs) platform will provide a more comprehensive overview of good practices.

All global organisations (e.g. the OECD, the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, the United Nations) have indicated that shortening the lifespan of the pandemic is a critical issue and that prolonging it will damage all economies. Moreover, increased financing needs, coupled with a decline in resources, has widened the SDG financing gap in developing countries, which is estimated to have increased by at least 50% because of the pandemic, to USD 3.7 trillion in 2020 (OECD, 2021[2]). The development co-operation community is being called upon to do more against the backdrop of a growing need and an ongoing global crisis.

In April 2020 as the COVID crisis was unfolding, DAC members recognised that “poor people will be hardest hit where health systems, government structures and social safety nets are weak”, underscoring the importance of investment in country systems (OECD, 2020[22]). Further commitments to use ODA to “continue to protect health, water and sanitation, and social safety net programmes and to support investments in immunisation as a global public good” were made in November 2020 (OECD, 2020[9]). These statements recognise the central and unique role that ODA can play in the response and recovery effort and the importance of protecting and growing this concessional flow. Other groups have made similar commitments. For example, the Arab Co-ordination Group, the second-largest grouping of development co‑operation providers after the DAC, committed to allocate USD 10 billion to support developing countries in their immediate response and recovery efforts (Arab Coordination Group, 2020[23]).

As COVID-19 continues to spread (WHO, 2021[24]), vaccine access remains unequal (OECD, 2021[25]), countries experience differentiated health and economic recovery trajectories, and the demand for ODA and other supportive development flows is likely to increase. In May 2021 for example, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) proposed a USD 50 billion investment to vaccinate at least 40% of the global population by the end of 2021 and 60% by the first half of 2022 (Agarwal and Gopinath, 2021[26]). This proposal includes USD 22 billion to close the 2021 funding gap for the World Health Organization’s (WHO) ACT-Accelerator (ACT-A) (see Funding gaps and ODA eligibility for ACT-A pillars, apart from COVAX for a breakdown and ODA eligibility), and USD 13 billion in additional grant contributions, the remainder to be paid by national governments, potentially with the support of concessional financing from bilateral and multilateral agencies (Agarwal and Gopinath, 2021[26]). Other review processes have also advocated for expanded financing for the ACT-A.

The ACT-A, established in 2020 to accelerate the development, production and equitable access to COVID-19 tests, treatments and vaccines, has to date received pledges of USD 15.1 billion13 (WHO, 2021[27]). Across the four pillars of ACT-A (diagnostics, therapeutics, vaccines and health systems), the vaccines pillar has received the most pledges by far, USD 9.5 billion14 (WHO, 2021[27]). This pillar, otherwise known as COVAX, consists of the COVAX Facility, a mechanism for “self-financing” countries, and the COVAX Advance Market Commitment (AMC), which provides seed funding to support high-risk populations in the LICs and lower middle-income countries. Within the vaccines pillar, only contributions to the COVAX AMC are ODA-eligible, at a rate of 100%. Funding commitments for the AMC in 2021 include USD 2.5 billion committed by the United States (part of a total commitment of USD 4 billion over multiple years) for vaccine procurement and a pledge from Germany for an additional EUR 980 million (GAVI, 2021[28]). An event in April saw pledges of an additional USD 400 million (GAVI, 2020[29]) and in June, the Gavi COVAX Advance Market Commitment Summit hosted by Japan saw countries and companies pledge and additional USD 2.4 billion (USD 300 million of which pledged from private sector) (GAVI, 2021[30]).

In addition to funding for the COVAX AMC, countries are also beginning to commit to share doses of COVID-19 vaccines. New commitments were announced at the Global Health Summit in May 2021, including Team Europe’s aim to donate 100 million doses of vaccines to low- and middle-income countries until the end of 2021, in particular through COVAX (European Commission, 2021[31]). The United States has also indicated that it could share up to 80 million doses of vaccines in the coming months (Stolberg and Slotnik, 2021[32]). At the AMC Summit in June, five countries also pledged to donate more than 54 million vaccine doses to lower-income countries, including through COVAX (GAVI, 2021[30]). A calculation to value the ODA eligibility of vaccine doses will be discussed by the Working Party on Statistics (WPSTAT) later in 2021.

The Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness and Innovations (CEPI) is separately responsible for research and development and manufacturing under the vaccines pillar. Just over half (53%) of earmarked contributions to CEPI for COVID-19 related work were eligible to be counted as ODA for the year 2020 (OECD, 2021[33]).15 The total 2021 funding gap for CEPI is USD 890 million.

Contributions to the diagnostics and therapeutics pillars of ACT-A are 100% ODA eligible (OECD, 2021[33]). WHO estimates the 2021 funding gaps to be USD 8.7 billion and USD 3.2 billion, respectively. The ODA eligibility of contributions to the health systems connector is scheduled to be determined later in 2021.

|

2021 funding gap |

ODA eligibility |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Vaccines (CEPI) |

USD 0.89 billion |

53% |

|

Diagnostics |

USD 8.7 billion |

100% |

|

Therapeutics |

USD 3.2 billion |

100% |

|

Health Systems Connector |

USD 7.4 billion |

To be determined |

Note: CEPI: Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness and Innovations.

Source: For the funding gap: WHO (2021[34]); for ODA eligibility: OECD (2021[33]).

Key moments on the international calendar have the potential to drive new commitments around key issues, including health security and climate change. For example, the May 2021 meeting of the G7 Foreign and Development Minister’s Meeting committed to “keep working together, with partner countries and within the multilateral system, to shape a cleaner, freer, fairer and more secure future for the planet” (G7, 2021[35]). A G7 Leader’s Summit in June and a further G7 Foreign and Development Ministers’ meeting may provide opportunities to further commitments. In November, the United Kingdom will co-host the 26th UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP26) to accelerate action towards the goals of the PARIS Agreement and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UN, 2021[36]). Given the growing interlinkages between the climate agenda and the growth of ODA (Combating the climate crisis elevates official development assistance on the political agenda), this level of global attention on climate could have positive spillover effects for ODA in 2021. However, development finance and climate finance have distinct roles and aims. A complete conflation of these budgets and efforts would likely not succeed in achieving either of the critical climate or development agendas.

Combating the climate crisis is an area that clearly requires global action and high-level political commitment. If official development assistance (ODA) has proven to be the most stable source of external finance for developing countries driven by political will and global solidarity, it is safe to say that the high-level commitment to the climate agenda is at least partially responsible. Youth movements for action on climate change in recent years have highlighted the need for a new narrative on development co-operation as key to tackling interconnected, global issues (OECD, 2019[37]). The COVID-19 crisis has further underlined the importance of integrated programming to address the environmental pressures that exacerbate the likelihood of disease outbreaks and other adverse development outcomes (OECD, 2020[8]). As the feedback loops between these agendas become tighter, development co-operation also shines a light back on members’ domestic response to climate change and progress in meeting their own emissions targets.

While there is no clear way to determine whether climate investments have contributed to making ODA more resilient, a number of examples lend weight to the argument that increased attention on climate has kept ODA volumes from falling.

In Austria, where ODA increased by 0.6% in 2020, the government saw an opportunity to link the development co-operation and climate agendas by leaning on the Austrian society’s longstanding support for environmental sustainability to generate more support for development co-operation, including for the Green Climate Fund.

In 2020, ODA for climate-related objectives accounted for a significant portion of Canada’s 7.7% ODA increase. Canada designated environment and climate as one of six action areas in its Feminist International Assistance Policy, and committed CAD 2.65 billion to help developing countries transition to low-carbon, climate-resilient economies over the same period (OECD, 2018[38]).

Germany built on its strong political leadership for the Paris Agreement, providing insurance products on climate risk, supporting new climate funds and regularly committing a significant portion of its bilateral ODA (42% in 2019; USD 8.2 billion) for climate change focused activities. Since 2011, Germany’s ODA has progressively increased, becoming the second-largest DAC provider country in volume in 2016 and reaching USD 28.4 billion in 2020 (0.73% of gross national income) (OECD, 2015[39]).

Iceland’s own experience in natural resource management through land restoration and sustainable fisheries and in geothermal energy drives its international development co-operation, which increased by 7.8% in 2020. Through its training programmes in land restoration and energy and technical expertise offered to multilateral organisations in these areas, Iceland demonstrates how a small donor in terms of volume can have a significant impact (OECD, 2020[40]).

Throughout 2020 and into 2021, efforts were made to address debt sustainability concerns and to provide mechanisms to free up fiscal space, notably through the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI), which has provided USD 5.7 billion in relief to 43 eligible countries (World Bank and IMF, 2021[14]). Though the DSSI has been extended to June 2021, it was a short-term emergency measure, in which private creditors have not participated, nor does it provide a framework for countries to address overall debt levels (World Bank and IMF, 2021[14]). Alongside the extension, a Common Framework for Debt Treatments Beyond the DSSI was agreed (G20, 2021[42]). This framework facilitates treatment for debt in 73 DSSI-eligible countries beyond debt service suspension, such as debt restructuring, and importantly provides for co‑ordination among official bilateral creditors as well as a requirement on debtor countries to seek from private creditors a treatment at least as favourable (G20, 2021[42]). According to the IMF, in early 2021, there were 36 countries either “in debt distress” or at “high” risk of debt distress (IMF, 2021[43]). The Common Framework is initiated at the request of debtor countries. To date, Chad, Ethiopia and Zambia have requested treatment under the Common Framework (IMF, 2021[44]), all of which were classified at high risk of debt distress.

In mid-2020, the DAC agreed to change the methodology for reporting debt relief as ODA (switching from cash flow to grant equivalent basis) and preliminary 2020 figures show USD 541 million of debt relief. Under the new terms, development co-operation providers can report debt treatments in ODA based on a comparison of the original and new grant equivalent of the loan, post treatment with the amount reported capped to the nominal value of the original loan: this means that the value of a dollar of a loan and its subsequent debt treatment in OECD ODA statistics would never be equal to or more than the value of a dollar that had been granted (given rather than lent) (OECD, 2020[45]). Though the DSSI has been extended, debt suspension activities do not meet the criteria to be counted as ODA. However, activities under the Common Framework (discussed above) which go beyond suspension to debt treatment could contribute to ODA.

New instruments have also been launched to respond to COVID-19. The World Bank’s Health Emergency Preparedness and Response Multi-Donor Fund is one example (World Bank, 2020[46]). This new fund has to date provided approximately USD 50 million in financing to eligible countries (World Bank, 2021[47]) and has attracted contributions from DAC members, e.g. Germany has contributed about USD 12.1 million (World Bank, 2021[48]).

Calls persisted throughout 2020 for an extension or reallocation of IMF Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) to help countries respond to the pandemic (OECD, 2020[8]). SDRs are an international reserve asset created by the IMF, are only allocated to IMF members and are distributed across the membership in proportion to IMF quota shares: 42.2% corresponds to the share of emerging market and developing countries, of which 3.2% corresponds to low-income countries (IMF, n.d.[49]). Following informal discussion among IMF Executive Directors in March 2021, the IMF Managing Director stated that she intended to present a formal proposal to the Executive Board by June 2021 to consider a new allocation of USD 650 billion (IMF, 2021[50]). The US Treasury Department estimates that of this USD 650 billion, about USD 21 billion worth of SDRs would be provided to the LICs and USD 212 billion to other emerging market and developing countries (excluding the People’s Republic of China) based on existing quotas (US Treasury Department, 2021[51]). The United Nations is calling for the voluntary reallocation of SDRs from countries with sufficient international reserves to countries facing persistent external deficits (UN, 2020[52]), and a recent summit held in France is working towards reallocating USD 100 billion in SDRs from advanced economies to African states by October 2021 (French Presidency, 2021[53]). Some analysis has found that there may be significant obstacles to this approach (Andrews, 2021[54]). The reallocation of SDRs to developing countries will involve complex operations. The ODA accounting of such operations will be determined as soon as more detail becomes available.

In 2020, the DAC committed to strive to protect ODA budgets (OECD, 2020[22]), recognising the key role that this unique concessional flow can play in times of crisis. In response to a special survey in late 2020, many providers of development co-operation indicated that they had reoriented funds from existing 2020 development co-operation programmes for COVID-19 related activities; however, most indicated that they had not discontinued ongoing development programmes (OECD, 2021[4]). Concerns have been raised, however, about how to protect ODA going forward, and whether higher spending in 2020 may have implications for future budgets. If ODA/GNI ratios were to decrease to 2019 levels, the overall fall could be up to USD 14 billion.16 However, in general, as budgets are typically annual, higher spending in 2020 should not automatically result in lower budgets in subsequent years.

An additional issue raised has been possible future budget cuts to repay debt raised by advanced economies to fund their COVID-19 fiscal response measures, which could impact ODA. However, there are ongoing debates regarding government borrowing to fund pandemic response, with some economists arguing that current borrowing will be offset by revenues from growth when economies reopen (Letzing, 2020[55]). The OECD projects global GDP growth at 5.8% in 2021 and 4.4% in 2022, and world output is expected to reach pre-pandemic levels by mid-2021, although this will depend on the pace at which vaccines are administered and further lockdowns (OECD, 2021[56]).

Maintaining or improving ODA/GNI ratios will require increased volumes, sustained political will, and can be supported by employing specific mechanisms (DAC members’ mechanisms to protect official development assistance volumes and ODA/GNI ratios). ODA as a proportion of GNI in 2020 was 0.32%. In order to hold this proportion steady in line with OECD growth projections in 2021, ODA would need to increase from USD 161 billion to USD 165 billion.17 Looking to past crises, some countries have found that once ODA/GNI ratios drop, they can be difficult or take a long time to recover, even as economic growth picks up. Long-term planning can help to avoid a drop in ODA/GNI ratios. For example, Finland is expected to soon publish a Government White Paper for Development Policy which will extend over several governmental and parliamentary terms and include a target date of 2030 to reach the international goal to provide 0.7% of GNI as ODA.

In recent years, some development co-operation providers have put mechanisms in place to smooth budgets that could be employed to offset any impact of economic fluctuations.

Multi-annual allocations can help to avoid significant change from one year to the next. In the multilateral space, for example, Italy has very long-term (ten years and more) budget commitments for Gavi and the International Finance Facility for Immunisation. Ireland is making multiannual contributions also for humanitarian assistance. New Zealand sets its official development assistance (ODA) budget on a three-year basis.

Budget balancing mechanism (averaging ODA/GNI ratio over time): Denmark employs a mechanism taking a three-year average for its ODA target of 0.7% of gross national income (GNI), which corrects for previous years’ actual spend and GNI levels. The mechanism is carried out in three steps: 1) taking 0.7% of GNI as a baseline; 2) calculating the previous year’s difference; and 3) adding the budget-balancing amount. This usually results in additional budget, as underspends from the previous years are carried over. For instance, in the 2021 Finance Bill, the development aid budget was raised to DKK 17.1 billion by adding the DKK 380 million. This resulted in 0.72% of GNI allocated to development aid in 2021.

Borrowing from future years: The Netherlands has a mechanism that allows borrowing from future years to smooth fluctuations that may be caused by changes in GNI. In 2020, borrowings from previous years were cancelled, effectively increasing the overall budget, and additional budget was allocated for COVID-19 response. However, this mechanism can prove problematic when multiple shocks occur, as ODA is pegged to GNI, resulting in a reduction in the amount of ODA available at a moment of multiplying demands.

Looking ahead, development co-operation providers face significant challenges in meeting simultaneous and rapidly increasing demands. These include: the mobilisation of resources to support partner country responses to the current crisis, both through traditional budgeting for ODA and allocation of a larger share of overall spending on crisis response; accelerating actions across the SDGs, taking account of the increased financing need; and stepping up contributions to global resilience in key areas, including health and climate security. While it is clear that ODA alone cannot meet these rising demands, development co‑operation providers are being called upon to do more to respond to the unique challenges facing the world today.

ODA reached an historic high in 2020 despite deteriorating domestic economic situations, evidencing once again that ODA growth is not tied to GDP growth. But the trends and analyses presented in this chapter show that countries made unequal contributions to ODA, with large increases in some countries offsetting drops in others. Other trends depict an evolving and complex landscape. Taking a multi-year, holistic view of lending and grant activity revealed that bilateral and multilateral actors have been playing distinct roles across income groups. While bilateral ODA increases were concentrated in middle-income countries in 2020, overall ODA to the LICs has, in fact, been rising in recent years, driven by large increases from multilaterals. And while loans rose to the surface as a valuable instrument for middle-income countries, terms for lending to the LDCs have hardened.

In 2021, three factors that may drive ODA growth are vaccines, climate and debt. New and increased activities in ODA-eligible categories to combat COVID-19, high-level political moments connected to both health and climate, and new approaches and increased demand for debt treatment may all be pathways through which ODA budgets will be channelled. While these pressing concerns may dominate the agenda, development co-operation providers will need to balance responses with maintaining a long-term perspective on advancing across the multiple dimensions of sustainable development and keeping up momentum towards improved policy coherence across domestic and international portfolios.

[26] Agarwal, R. and G. Gopinath (2021), “A proposal to end the COVID-19 pandemic”, Staff Discussion Notes, No. 2021/004, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Staff-Discussion-Notes/Issues/2021/05/19/A-Proposal-to-End-the-COVID-19-Pandemic-460263 (accessed on 28 May 2021).

[3] Ahmad, Y. et al. (2020), “Six decades of ODA: Insights and outlook in the COVID-19 crisis”, in Development Co-operation Profiles 2020, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/5e331623-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/5e331623-en#chapter-d1e20 (accessed on 20 November 2020).

[54] Andrews, D. (2021), “Can special drawing rights be recycled to where they are needed at no budgetary cost?”, CGD Notes, Center for Global Development, Washington, DC, https://www.cgdev.org/publication/can-special-drawing-rights-be-recycled-where-they-are-needed-no-budgetary-cost (accessed on 10 May 2021).

[23] Arab Coordination Group (2020), Final Communiqué: Heads of Arab Coordination Group Institutions, Arab Coordination Group, http://www.arabfund.org/Data/site1/pdf/CG/Communique%20by%20Heads%20of%20ACG_2020%20En.pdf.

[31] European Commission (2021), “Global leaders adopt agenda to overcome COVID-19 crisis”, press release, European Commission, Brussels, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_21_2605 (accessed on 25 May 2021).

[53] French Presidency (2021), Summit on the Financing of African Economies, French Presidency, Paris, https://www.elysee.fr/admin/upload/default/0001/10/8cafcd2d4c6fbc57cd41f96c99f7aede6bd351f1.pdf.

[42] G20 (2021), Common Framework for Debt Treatments beyond the DSSI, G20, https://clubdeparis.org/sites/default/files/annex_common_framework_for_debt_treatments_beyond_the_dssi.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2021).

[35] G7 (2021), G7 Foreign and Development Ministers’ Meeting, May 2021: Communiqué, G7, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/g7-foreign-and-development-ministers-meeting-may-2021-communique (accessed on 10 May 2021).

[28] GAVI (2021), ONE WORLD PROTECTED The Gavi COVAX AMC Investment Opportunity, https://www.gavi.org/sites/default/files/covid/covax/Gavi-COVAX-AMC-Investment-Opportunity.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2021).

[30] GAVI (2021), “World leaders and private sector commit to protecting the vulnerable with COVID-19 vaccines | Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance”, https://www.gavi.org/vaccineswork/world-leaders-and-private-sector-commit-protecting-vulnerable-covid-19-vaccines (accessed on 4 June 2021).

[29] GAVI (2020), Global leaders rally to accelerate access to COVID-19 vaccines for lower-income countries | Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, Webpage, https://www.gavi.org/news/media-room/global-leaders-rally-accelerate-access-covid-19-vaccines-lower-income-countries (accessed on 12 May 2021).

[50] IMF (2021), “IMF Executive Directors discuss a new SDR allocation of US$650 billion to boost reserves, help global recovery from COVID-19”, press release, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC, https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2021/03/23/pr2177-imf-execdir-discuss-new-sdr-allocation-us-650b-boost-reserves-help-global-recovery-covid19 (accessed on 10 May 2021).

[7] IMF (2021), “January 2021 charts and maps”, Database of Country Fiscal Measures in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic, https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/imf-and-covid19/Fiscal-Policies-Database-in-Response-to-COVID-19 (accessed on 18 May 2021).

[43] IMF (2021), List of LIC DSAs for PRGT-Eligible Countries, As of February 28, 2021, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC.

[44] IMF (2021), “Questions and answers on sovereign debt issues”, web page, International Monetary Fund, Washingon, DC, https://www.imf.org/en/About/FAQ/sovereign-debt (accessed on 10 May 2021).

[49] IMF (n.d.), “Questions and answers on special drawing rights”, web page, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC, https://www.imf.org/en/About/FAQ/special-drawing-right#Q1.%20What%20is%20an%20SDR? (accessed on 10 May 2021).

[21] Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness & Response (2021), COVID-19: Make it the Last Pandemic, Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness & Response, Geneva, https://theindependentpanel.org/mainreport (accessed on 18 May 2021).

[55] Letzing, J. (2020), “Countries are piling on record amounts of debt amid COVID-19: Here’s what that means”, World Economic Forum, Geneva, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/11/covid-19-has-countries-borrowing-money-just-about-as-quickly-as-they-can-print-it (accessed on 10 May 2021).

[2] OECD (2021), “2020 official development assistance levels and trends release, 13 April 2021”, remarks by Angel Gurría, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/about/secretary-general/oecd-sg-remarks-to-launch-the-2020-oda-levels-and-trends-13-april-2021.htm (accessed on 4 May 2021).

[25] OECD (2021), “Coronavirus (COVID-19) vaccines for developing countries: An equal shot at recovery”, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/6b0771e6-en.

[4] OECD (2021), “COVID-19 spending helped to lift foreign aid to an all-time high in 2020: Detailed note”, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-data/ODA-2020-detailed-summary.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2021).

[33] OECD (2021), Frequently Asked Questions on the ODA Eligibility of COVID-19 Related Activities – Updated March 2021, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/ODA-eligibility_%20of_COVID-19_related_activities_final.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2021).

[60] OECD (2021), “GDP and spending: Real GDP long-term forecast”, OECD, Paris, https://data.oecd.org/gdp/real-gdp-long-term-forecast.htm#indicator-chart (accessed on 27 May 2021).

[11] OECD (2021), ODA Eligibility Database, http://oe.cd/oda-eligibility-database (accessed on 20 May 2021).

[5] OECD (2021), OECD Economic Outlook, Interim Report March 2021, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/34bfd999-en.

[56] OECD (2021), OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2021 Issue 1: Preliminary Version, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/edfbca02-en.

[57] OECD (2021), “Official development assistance (ODA)”, web page, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-standards/official-development-assistance.htm (accessed on 18 May 2021).

[19] OECD (2021), “Total Official Support for Sustainable Development (TOSSD)”, Visualisation Tool, OECD, Paris, https://tossd.online (accessed on 19 April 2021).

[22] OECD (2020), COVID-19 Global Pandemic: Joint Statement by the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/dac/development-assistance-committee/DAC-Joint-Statement-COVID-19.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2020).

[9] OECD (2020), DAC High Level Meeting Communiqué 2020, OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/dac/development-assistance-committee/dac-high-level-meeting-communique-2020.htm (accessed on 20 November 2020).

[10] OECD (2020), DAC List of ODA Recipients, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-standards/DAC-List-ODA-Recipients-for-reporting-2021-flows.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2021).

[40] OECD (2020), DAC Mid-term Review of Iceland, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/dac/peer-reviews/DAC-mid-term-Iceland-2020.pdf (accessed on 19 May 2021).

[8] OECD (2020), Development Co-operation Report 2020: Learning from Crises, Building Resilience, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/f6d42aa5-en.

[62] OECD (2020), “Earmarked funding to multilateral organisations: How is it used and what constitutes good practice?”, Brief – Multilateral Development Finance, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-topics/Multilateral-development-finance-brief-2020.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2021).

[16] OECD (2020), Multilateral Development Finance 2020, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/e61fdf00-en.

[41] OECD (2020), OECD Development Co-operation Peer Reviews: Austria 2020, OECD Development Co-operation Peer Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/03b626d5-en.

[13] OECD (2020), OECD Development Co-operation Peer Reviews: Japan 2020, OECD Development Co-operation Peer Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b2229106-en.

[45] OECD (2020), Reporting on Debt Relief in the Grant Equivalent System: Methodology for Reporting Debt Relief on a Grant Equivalent Basis, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-standards/Reporting-Debt-Relief-In-Grant-Equivalent-System.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2021).

[37] OECD (2019), Development Co-operation Report 2019: A Fairer, Greener, Safer Tomorrow, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9a58c83f-en.

[17] OECD (2019), OECD Recommendation on Policy Coherence for Sustainable Development, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/gov/pcsd/oecd-recommendation-on-policy-coherence-for-sustainable-development.htm (accessed on 7 May 2021).

[38] OECD (2018), OECD Development Co-operation Peer Reviews: Canada 2018, OECD Development Co-operation Peer Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264303560-en.

[39] OECD (2015), OECD Development Co-operation Peer Reviews: Germany 2015, OECD Development Co-operation Peer Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264246133-en.

[59] OECD (2014), DAC High Level Meeting: Final Communiqué, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/dac/OECD%20DAC%20HLM%20Communique.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2021).

[6] OECD (n.d.), “International development statistics (IDS) online databases”, web page, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-data/idsonline.htm (accessed on 20 May 2021).

[12] OECD (n.d.), “Modernisation of the DAC statistical system”, web page, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/modernisation-dac-statistical-system.htm (accessed on 12 May 2021).

[18] OECD (n.d.), OECD Development Co-operation Peer Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/23097132.

[15] Ritchie, E. (2021), “Do ODA loan rules incentivise lending to poorer countries?”, Center for Global Development blog, Center for Global Development, Washington, DC, https://www.cgdev.org/blog/do-oda-loan-rules-incentivise-lending-poorer-countries (accessed on 20 May 2021).

[32] Stolberg, S. and D. Slotnik (2021), “The U.S. plans to send 20 million vaccination doses to help world battle the virus”, The New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/17/world/covid-vaccine-global-doses.html (accessed on 18 May 2021).

[61] UK Parliament (2021), “Future of UK aid: Reductions to the aid budget”, UK Parliament, London, https://committees.parliament.uk/work/843/future-of-uk-aid-reductions-to-the-aid-budget/news (accessed on 12 May 2021).

[58] UN (2021), “Least developed countries category”, web page, Office of the High Representative for the Least Developed Countries, Landlocked Developing Countries and Small Island Developing States, https://www.un.org/ohrlls/content/ldc-category (accessed on 20 May 2021).

[36] UN (2021), “UN Climate Change Conference UK 2021 website”, https://ukcop26.org (accessed on 10 May 2021).

[52] UN (2020), “Debt and COVID-19: A global response in solidarity”, UN Executive Office of the Secretary-General (EOSG) Policy Briefs and Papers, No. 4, United Nations, New York, NY, https://doi.org/10.18356/5bd43e89-en.

[51] US Treasury Department (2021), “How an allocation of International Monetary Fund special drawing rights will support low-income countries, the global economy, and the United States”, press release, US Department of the Treasury, Washington, DC, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy0095 (accessed on 10 May 2021).

[34] WHO (2021), ACT-A Prioritized Strategy and Budget for 2021, World Health Organization, Geneva, https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/act-a-prioritized-strategy-and-budget-for-2021 (accessed on 12 May 2021).

[27] WHO (2021), “The ACT Accelerator interactive funding tracker”, web page, World Health Organization, Geneva, https://www.who.int/initiatives/act-accelerator/funding-tracker (accessed on 12 May 2021).

[24] WHO (2021), WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard with Vaccination Data, web page, World Health Organization, Geneva, https://covid19.who.int (accessed on 17 May 2021).

[20] WHO and CBD Secretariat (2020), Biodiversity & Infectious Diseases: Questions & Answers, World Health Organization, Geneva, https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/climate-change/qa-infectiousdiseases-who.pdf?sfvrsn=3a624917_3 (accessed on 10 May 2021).

[1] World Bank (2021), “Defying predictions, remittance flows remain strong during COVID-19 crisis”, press release, World Bank, Washington, DC, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2021/05/12/defying-predictions-remittance-flows-remain-strong-during-covid-19-crisis?cid=ECR_E_NewsletterWeekly_EN_EXT&deliveryName=DM104029 (accessed on 20 May 2021).

[48] World Bank (2021), “Germany contributes €10 million to WB Trust Fund for Disease Preparedness in Developing Countries”, web page, The World Bank, Washington, DC, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2021/02/02/germany-contributes-10-million-to-wb-trust-fund-for-disease-preparedness-in-developing-countries (accessed on 10 May 2021).

[47] World Bank (2021), “Health Emergency Preparedness and Response (HEPR) Umbrella Program”, web page, The World Bank, Washington, DC, https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/health/brief/health-emergency-preparedness-and-response-hepr-umbrella-program (accessed on 10 May 2021).

[46] World Bank (2020), “World Bank Group to launch new multi-donor trust fund to help countries prepare for disease outbreaks”, web page, The World Bank, Washington, DC, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/statement/2020/04/15/world-bank-group-to-launch-new-multi-donor-trust-fund-to-help-countries-prepare-for-disease-outbreaks (accessed on 10 May 2021).

[14] World Bank and IMF (2021), World Bank Group and International Monetary Fund Support for Debt Relief Under the Common Framework and Beyond, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Policy-Papers/Issues/2021/04/01/World-Bank-Group-And-International-Monetary-Fund-Support-For-Debt-Relief-Under-The-Common-50321 (accessed on 10 May 2021).

|

Country |

Fiscal measures as a % of GNI 2020 |

ODA as a % of GNI 2020 |

ODA as a % of fiscal measures |

ODA growth rate (%), year-on-year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Australia |

18.12 |

0.19 |

1.06 |

-10.6 |

|

Austria |

10.83 |

0.29 |

2.72 |

0.6 |

|

Belgium |

19.77 |

0.47 |

2.36 |

2.8 |

|

Canada |

18.85 |

0.31 |

1.64 |

7.7 |

|

Czech Republic |

21.72 |

0.13 |

0.60 |

-5.2 |

|

Denmark |

5.77 |

0.73 |

12.66 |

0.5 |

|

Finland |

9.68 |

0.47 |

4.81 |

8.1 |

|

France |

22.68 |

0.53 |

2.35 |

10.9 |

|

Germany |

37.69 |

0.73 |

1.93 |

13.7 |

|

Greece |

16.55 |

0.13 |

0.78 |

-36.2 |

|

Hungary |

8.19 |

0.27 |

3.26 |

35.8 |

|

Iceland |

8.48 |

0.29 |

3.41 |

7.8 |

|

Ireland |

9.06 |

0.31 |

3.41 |

-4.1 |

|

Italy |

41.48 |

0.22 |

0.53 |

-7.1 |

|

Japan |

42.11 |

0.31 |

0.74 |

1.2 |

|

Korea |

13.49 |

0.14 |

1.01 |

-8.6 |

|

Luxembourg |

16.60 |

1.02 |

6.17 |

-9.2 |

|

Netherlands |

12.66 |

0.59 |

4.68 |

-2.8 |

|

New Zealand |

23.19 |

0.27 |

1.16 |

-5.2 |

|

Norway |

7.16 |

1.11 |

15.50 |

8.4 |

|

Poland |

13.25 |

0.14 |

1.05 |

1.1 |

|

Portugal |

11.38 |

0.17 |

1.50 |

-10.6 |

|

Slovak Republic |

8.36 |

0.14 |

1.64 |

16.3 |

|

Slovenia |

12.04 |

0.17 |

1.43 |

-1.7 |

|

Spain |

18.69 |

0.24 |

1.26 |

-1.8 |

|

Sweden |

9.14 |

1.14 |

12.53 |

17.1 |

|

Switzerland |

11.41 |

0.48 |

4.22 |

8.8 |

|

United Kingdom |

32.98 |

0.70 |

2.12 |

-10.0 |

|

United States |

18.68 |

0.17 |

0.88 |

4.7 |

|

|

||||

|

DAC total |

23.48 |

1.37 |

Notes: GNI: gross national income. ODA: official development assistance. Fiscal measures are a combination of “above the line measures” and “liquidity support”. Calculations exclude European Union institutions. Totals refer to total volume of fiscal measures for DAC countries as a proportion of gross national income and total official development assistance volume as a proportion of total volume of fiscal measures.

Source: Fiscal measures: author’s calculations using data from IMF January 2021 Charts and Maps (2021[7]); GNI at market prices and ODA figures derived or calculated from OECD (2021[57]).

Calculated using a 10% discount rate (“old” method) and discount rates differentiated by income group (9%, 7% and 6% – “new” method)

|

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Old |

New |

Old |

New |

Old |

New |

New |

New |

|

|

Australia |

74% |

64% |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

|

Belgium |

87% |

85% |

88% |

84% |

93% |

90% |

67% |

83% |

|

Canada |

26% |

17% |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

|

EU institutions |

49% |

33% |

49% |

40% |

49% |

35% |

38% |

39% |

|

Finland |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

79% |

67% |

|

France |

54% |

40% |

54% |

40% |

53% |

40% |

44% |

45% |

|

Germany |

46% |

31% |

47% |

32% |

46% |

31% |

35% |

36% |

|

Italy |

93% |

88% |

95% |

89% |

85% |

77% |

81% |

68% |

|

Japan |

81% |

71% |

77% |

67% |

76% |

67% |

68% |

70% |

|

Korea |

88% |

82% |

87% |

81% |

88% |

81% |

80% |

77% |

|

Poland |

79% |

77% |

76% |

73% |

77% |

73% |

79% |

68% |

|

Portugal |

67% |

56% |

59% |

46% |

58% |

47% |

47% |

49% |

|

Spain |

– |

– |

– |

– |

51% |

35% |

41% |

34% |

|

United Kingdom |

– |

– |

61% |

40% |

72% |

52% |

31% |

40% |

|

Average |

65% |

53% |

64% |

52% |

64% |

52% |

55% |

54% |

Notes: The average grant element of loans to all developing countries declined slightly throughout the transition period (from 53% in 2015 to 52% in 2017). It rose to 55% in 2018 and fell back to 54% in 2019. A number of members applied harder lending terms throughout the period: Belgium (the grant element decreased from 85% to 83%), Italy (from 88% to 68%), Korea (from 82% to 77%) Poland (from 77% to 68%) and Portugal (from 56% to 49%).

|

Belgium |

EU institutions |

Finland |

France |

Germany |

Italy |

Japan |

Korea |

Poland |

Portugal |

Spain |

United Kingdom |

DAC average |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Average grant element |

83% |

39% |

67% |

45% |

36% |

68% |

70% |

77% |

68% |

49% |

34% |

40% |

54% |

|

Average interest rate |

0.0% |

1.4% |

0.1% |

1.2% |

1.4% |

0.5% |

0.6% |

0.3% |

0.3% |

1.9% |

2.9% |

0.0% |

1.0% |

|

Average maturity (years) |

34 |

18 |

40 |

18 |

16 |

26 |

34 |

38 |

33 |

22 |

20 |

8 |

25 |

← 1. By 3.5% in real terms on a grant-equivalent basis and 7% in terms of net ODA flows from 2019.

← 2. Average GDP growth in OECD countries was -5.48% in 2020.

← 3. Thirteen other official development co-operation providers also reported USD 544 million in 2020 on COVID-19 related activities, mostly from the United Arab Emirates (USD 274 million) and Saudi Arabia (USD 208 million).

← 4. Total of “Above the line measures” and “Liquidity support” according to IMF, January 2021 Charts and Maps (2021[7]).

← 5. By contrast, 2020 saw a decrease in in-donor refugee costs (-9.5%).

← 6. Forty-six countries that satisfy all criteria for the LDCs, including all LICs, as set out by the United Nations and qualify for exclusive international support measures (UN, 2021[58]).

← 7. Equal to 21% of total 2020 ODA, and an increase of 1.8% in real terms from 2019 figures.

← 8. From 2017 to 2019, ODA from DAC countries to the LICs dropped by 2%.

← 9. See OECD (2014[59]).

← 10. Pillar I: cross-border resources for SDG financing to developing countries, both from traditional and emerging providers, and Pillar II: the financing of international public goods, which include both regional and global public goods. It is not possible to disaggregate regional from global activities.

← 11. The financing captured under the TOSSD is additional to OECD statistics on development finance because it is not solely focused on developing countries.

← 12. Recent work has been done to suggest new categorisations of modalities of earmarked funds to aid in its analysis (OECD, 2020[62]).

← 13. Other official development co-operation providers have contributed to the ACT-A, including Saudi Arabia (USD 313 million), Kuwait (USD 40 million) and Qatar (USD 10 million). Saudi Arabia ranks among the top 10 most generous providers to the ACT worldwide. Overall, other official development co-operation providers reporting development co-operation data to the OECD have primarily contributed to Gavi (USD 173.7 million) and CEPI (USD 160.9 million).

← 14. Accessed on 09 June 2021.

← 15. A calculation for the year 2021 has not yet been made.

← 16. This calculation takes into account the United Kingdom’s announced reduction of ODA spending from 0.7% to 0.5% of GNI from 2021, reducing the aid budget by one-third compared to 2019 levels (UK Parliament, 2021[61]).

← 17. Author’s calculations based on long-term GDP forecast (OECD, 2021[60]).