Jonas Wilcks

OECD Development Co-operation Directorate

Néstor Pelechà Aigües

OECD Development Co-operation Directorate

Emily Bosch

OECD Development Co-operation Directorate

Jonas Wilcks

OECD Development Co-operation Directorate

Néstor Pelechà Aigües

OECD Development Co-operation Directorate

Emily Bosch

OECD Development Co-operation Directorate

With contributions from Marisa Berbegal Ibáñez, Harsh Desai, Abdoulaye Fabregas, Jenny Hedman, Tomas Hos, Ida Mc Donnell and Valentina Orrù, OECD Development Co-operation Directorate.

The OECD is a global hub for development finance statistics with OECD and other countries, multilateral organisations, and private philanthropic providers like the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the Wellcome Trust reporting annually on their development statistics. Drawing on an analysis of the individual profiles in this publication, this chapter tells a story about the collective trends, showing how providers concentrate their funding – through bilateral, multilateral, or other delivery channels like civil society, universities and other private actors – and to which countries, sectors and critical cross-cutting priorities, like gender equality and the environment.

The analysis is based on the complete, detailed and validated official development assistance (ODA) statistics for 2019 as well as preliminary 2020 data for overall ODA. It includes flows from members of the OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC); other official development co-operation providers such as Chile, Mexico and Turkey and private foundations. The OECD also prepares estimates on how the OECD key partners China, India, Indonesia, Brazil and South Africa contribute to development and South-South co‑operation.

The chapter draws on data from 93 providers: all 30 OECD-DAC members, a further 29 countries that provide development finance data, and 34 private foundations reporting data development finance statistics to the OECD.

For further information please see the methodological notes.

Total ODA provided by DAC countries increased by 3.5% to reach USD 161.2 billion in 2020. This is equivalent to 0.32% of gross national income (GNI).1 The United States continued to be the largest provider of ODA (USD 35.5 billion), followed by Germany (USD 28.4 billion), the United Kingdom (USD 18.6 billion), Japan (USD 16.3 billion) and France (USD 14.1 billion). ODA rose in 16 DAC member countries, with some substantially increasing their budgets to help developing countries face the COVID-19 pandemic. Large increases were noted in Canada (+7.7%), Finland (+8.1%), France (+10.9%), Germany (+13.7%), Hungary (+35.8%), Iceland (+7.8%), Norway (+8.4%), the Slovak Republic (+16.3%), Sweden (+17.1%) and Switzerland (+8.8%). ODA fell in 13 countries, with the largest drops in Australia (-10.6%), Greece (‑36.2%), Italy (-7.9%), Korea (-8.6%), Luxembourg (-9.2%), Portugal (-10.6%) and the United Kingdom (‑10.0%).

In addition, total ODA for 16 other official development co-operation providers reached USD 13.15 billion in 2020. Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates – the three largest official providers among this group – accounted for USD 11.2 billion (85.1%) of this total. The significant decrease by the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia are partly explained by particularly high levels in previous years, notably due to exceptional humanitarian support provided to neighbouring countries such as the Syrian Arab Republic (hereafter “Syria”) and Yemen. According to OECD estimates, foreign assistance budgets of other major providers such as the People’s Republic of China (hereafter “China”) and India have increased by 23% over the last six years, reaching USD 6.9 billion in 2019. China (estimated USD 4.8 billion) and India (estimated USD 1.6 billion) account for the bulk of this assistance in 20192.

Note: OECD estimates for 2020 official development assistance amounts for Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kuwait, Liechtenstein and Thailand.

Note: The chart includes OECD estimates for 2020 ODA of Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kuwait, Liechtenstein and Thailand. The chart does not include other official development co-operation providers that provided less than USD 60 million in 2020 – i.e. Azerbaijan (USD 28 million), Cyprus (USD 46 million), Estonia (USD 43 million), Kazakhstan (USD 40 million), Latvia (USD 35 million), Liechtenstein (USD 26 million), Malta (USD 40 million).

Private philanthropic foundations that report their development flows to the OECD provided USD 9 billion in 2019, which was a 3% increase compared to 2018. Approximately 84% was extended in the form of grants, while the remaining 16% related to foundations’ lending activities and equity investments. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation continues to be the largest philanthropic foundation, disbursing USD 4.1 billion in 2019, 50% of the total for private philanthropic foundations that report to the OECD. The five largest foundations in terms of spend, that report to the OECD are: the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the BBVA Microfinance Foundation, the United Postcode Lotteries, the Wellcome Trust, and the Mastercard Foundation.

Seven OECD member countries – Denmark, Germany, Luxembourg, Norway, Sweden, Turkey and the United Kingdom – met the United Nations’ collective target of 0.7% of GNI to ODA in 2020, as per SDG 17 and the international commitments set out in the Addis Ababa Action Agenda. Turkey disbursed the equivalent of 1.12% of its GNI as ODA in 2020.

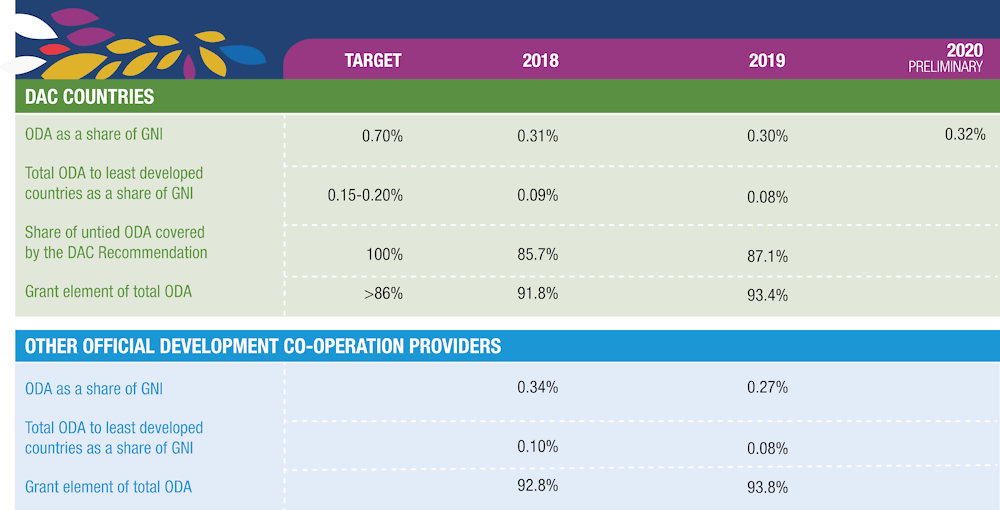

OECD-DAC members are accountable for several international commitments as outlined in Table 1. With the exception of exceeding an ODA grant element greater than 86%, collectively DAC countries are not meeting their other targets. The share of GNI provided as ODA for the 23 DAC countries not meeting the 0.7% ODA/GNI target was 0.24% in 2020. Had all DAC countries met the 0.7% target in 2020, ODA would have been USD 349.8 billion– USD 188.6 billion more than was provided.

Notes: DAC: Development Assistance Committee. ODA: official development assistance. GNI: gross national income. See the methodological notes for further details on untying ODA and the grant element of ODA

In 2017, DAC countries reported the second-highest level ever of the share of ODA covered by the Untied ODA DAC Recommendation, at 91.2%,3 but this share fell to 87.1% in 2019. Australia, Finland, Ireland, Luxembourg, Norway, Switzerland and the United Kingdom delivered fully on their untying commitments in 2019. Austria, Denmark, France, Iceland, Italy, Japan, New Zealand, Slovenia, Spain and the United States all saw an increase in the share of their tied bilateral ODA between 2018 and 2019. Nevertheless, Belgium, Canada, the Czech Republic, Finland, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Korea, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal and the Slovak Republic made progress in reducing the share of tied aid.

A high share of ODA is managed and allocated through bilateral channels. In 2019, DAC countries provided USD 117.6 billion (75.5% of total ODA) as gross bilateral ODA (including earmarked contributions to multilateral organisations). While this was just a 0.1% decrease from 2018, there was a significant decrease of 23% in real terms in bilateral spending by other official providers (which was USD 16.1 billion, or 91.0% of total ODA) over the same period. The largest decreases occurred in Kuwait (-63.4%), Saudi Arabia (-54.5%) and the United Arab Emirates (-36.1%). The decline in bilateral ODA in these countries is partly explained by the economic downturn of the Gulf countries in the last years and the decrease in the exceptional humanitarian support to their neighbouring countries.

There are also significant differences in trends across countries, which also relates to the structure of their ODA budgets. For example:

Half of DAC member countries (15 out of 29) increased their bilateral ODA in 2019, with Greece (+286.5%), Finland (+26.3%), Hungary (+27.0%), Korea (+14.2%) and Norway (+11.4%) seeing the largest increases, while the largest decreases came from Italy (-33.4%), the Slovak Republic (-31.75%), Belgium (-11.8%), Iceland (-9.0%) and Poland (-8.7%).

Countries whose share of bilateral ODA is higher than the DAC average of 75.5% are the United States (87.6%), Iceland (83.6%), New Zealand (82.1%), Germany (79.1%), Japan (77.6%), Norway (77.3%), Australia (77.2%), Luxembourg (77.0%) and Korea (76.5%).

The bilateral component of the ODA budget of many European Union (EU) member states tends to be lower than that of non-EU countries which is explained by contributions to the EU development budget. The EU institutions and the 27 EU member states, now without the United Kingdom, collectively provided USD 76.1 billion in 2020.

In 2019, DAC members provided USD 20.7 billion of gross bilateral ODA for civil society organisations (CSOs). The share of bilateral ODA allocated to and through CSOs remained stable for DAC members at 15%. Despite a small increase, developing country-based CSOs continued to receive the lowest share of support among all categories of CSOs (6.1% in 2019 up from 5.4% in 2018). CSOs receiving the largest share of ODA are those that are based in countries providing the assistance, which usually partner with local organisations.

Looking more closely at country-level performance, the United States accounted for over one-third of the total (USD 6.7 billion). EU institutions increased their share of bilateral ODA to and through CSOs (from 10.6% of bilateral ODA in 2018 to 11.5% in 2019), reaching USD 2.0 billion. Among other official development co-operation providers, the United Arab Emirates accounted for over two-thirds of gross allocations for CSOs in 2019 (USD 344.3 million in total). Ireland (21%) provided the highest share of core contributions to CSOs, followed by Belgium (18%), Switzerland (11%), Italy (9%) and Norway (7%). Core support is most conducive to meeting the objective of strengthening an independent and pluralist civil society in partner countries.

The share of bilateral ODA for CSOs declined in eight countries (Finland, Iceland, Ireland, Japan, Luxembourg, Poland, Switzerland and the United Kingdom). Learn more about ODA allocations to and through CSOs and civil society engagement in development co-operation.

In 2019, the top 5 ODA recipients, from a total of 165 eligible recipients for DAC countries collectively, were India, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Syria and Jordan. These five countries received over 10% of total bilateral ODA, with India receiving 3.6%. Five countries of the top 10 ODA recipients for DAC countries are least developed countries (LDCs). Out of the top 10 ODA recipients for DAC countries, five are middle-income countries (India, Bangladesh, Jordan, Iraq and Kenya). Syria, Yemen, Egypt, Sudan, and the West Bank and Gaza Strip were the top 5 recipients for other official development co-operation providers. Syria alone received over 45% of total bilateral ODA from these providers. In 2019, Turkey disbursed more than USD 7 billion to Syria (98.9% of total). The top 5 recipients for the Gates Foundation, the largest of the private foundations covered, were Peru, India, Colombia, Nigeria and Kenya.

In 2019, DAC countries’ bilateral ODA focused primarily on Africa (USD 32.7 billion), followed by Asia (USD 24.4 billion) and the Middle East (USD 10.5 billion). Japan and Germany were the top DAC provider countries in Asia (providing USD 9.1 billion and USD 3.7 billion respectively), while the United States accounted for close to one-third of all DAC countries’ bilateral ODA to Africa, at USD 10.0 billion. The United States was also the largest provider to the Middle East (USD 3.2 billion), followed by Germany (USD 2.8 billion) and the United Kingdom (USD 1.2 billion). In relation to their overall bilateral portfolio, Japan disbursed the highest share of its gross bilateral ODA to Asia (62%), while Portugal allocated the highest share of its bilateral portfolio to Africa (70.1%). Thirty-two per cent of DAC countries’ gross bilateral ODA was unspecified by region in 2019.

In 2019, bilateral ODA from other official development co-operation providers focused mainly on the Middle East (USD 10.1 billion), with Turkey providing over 75% of this amount. The United Arab Emirates accounted for almost half of the gross bilateral ODA to Africa from other official providers. ODA from other official development co-operation providers that are members of the EU primarily focused on the ODA‑eligible countries in Europe (USD 89.4 million), with Romania providing 63.6% and Croatia 16.7% of this amount.

Small island developing states have been hit hard economically by the pandemic. As they struggle to recover with a contracting ocean economy, and looming climate change dangers, a blue recovery becomes a necessity. DAC countries allocated 2.6% of gross bilateral ODA to small island developing states (USD 2.5 billion), with Australia allocating the highest volume and New Zealand the highest share of gross bilateral ODA. Other official development co-operation providers allocated 3.1% of their gross bilateral ODA to small island developing states in 2019 (USD 491 million).

In 2019, the highest share of multilateral contributions went to United Nations (UN) organisations, followed by EU institutions, and the World Bank Group for DAC countries. For other official development co-operation providers, the highest share of multilateral contributions also went to UN organisations, followed by regional development banks, with the EU institutions receiving the third highest share. The UN system as a whole received 37.8% of total multilateral contributions (USD 27 billion), primarily via earmarked contributions. In 2019, the United Nations Development Programme was the top recipient for nine DAC countries, while the World Food Programme was the leading UN recipient for seven DAC countries. The World Bank Group was the third most important beneficiary of multilateral allocations for DAC countries. For 15 DAC countries and 8 other official providers – all members of the EU – the largest share of multilateral spend was allocated to the EU institutions. Learn more about multilateral development finance.

Core multilateral contributions represented 24.5% of total ODA for DAC countries and this decreased by 1% in 2019. DAC countries provided USD 72.8 billion of gross ODA to the multilateral system (USD 44 billion as core multilateral ODA and USD 28.7 billion as earmarked contributions for a specific country, region, theme or purpose), an increase of 0.5% in real terms from 2018. Other official development co-operation providers provided USD 2.9 billion of gross ODA to the multilateral system (USD 1.6 billion as core multilateral ODA and the rest as earmarked contributions), an increase of 1% in real terms from 2018, following a large increase in 2018 from 2017.

Twenty countries provided a higher share of bilateral ODA, whereas 9 countries (all EU member states) provided a higher share of multilateral ODA. Other official development co-operation providers disbursed 9% of their ODA multilaterally. However, this low share is not representative of the entire group: eight countries provided over half of their development finance as multilateral ODA, the seven EU member states among them mainly as part of their contribution to the EU.

Of DAC countries’ non-core contributions, 76% was earmarked for pooled funds and specific‑purpose programmes and funds while the remaining 24% was earmarked to specific projects. For other official development co-operation providers 92% of non-core contributions supported pooled funds and specific programmes and funds, while 8% was earmarked to specific projects.

In 2019, on average, DAC countries committed 37.1% of bilateral ODA (USD 54.7 billion) to social infrastructure and services, with a high degree of variation. For example Austria, Hungary, Poland, Portugal, the Slovak Republic and Slovenia allocated at least 50% of their bilateral ODA to social infrastructure and services. Within this broad sector, DAC countries focused mostly on support to government and civil society (USD 19.9 billion) and health and population policies (USD 13.5 billion). Japan (52.1%), Korea (33.8%) and France (22.8%) committed a substantial share of their bilateral ODA to economic infrastructure and services, while Japan (13.8%) and New Zealand (13.0%) stand out as committing more of their bilateral ODA to production sectors than other DAC countries. Within economic infrastructure and services, the energy sector receives the most funding (USD 10.6 billion), whereas production financing goes mainly to agriculture (USD 6.6 billion).

In 2019, other official development co-operation providers collectively committed most of their bilateral ODA to humanitarian aid (USD 9 billion), with an emphasis on emergency response, notably driven by Turkey (USD 7.6 billion) and followed by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. General budget support (USD 2.0 billion) was largely supported by the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia and Qatar. Other official development co-operation providers’ earmarked contributions to multilateral organisations also focused on humanitarian aid.

DAC countries’ bilateral humanitarian aid amounted to USD 20.2 billion (13.7% of bilateral ODA), with Denmark, Ireland, the United Kingdom and the United States committing the largest shares to humanitarian aid. DAC countries’ earmarked contributions to multilateral organisations focused primarily on humanitarian aid and on social sectors and governance.

Private foundations allocated USD 4 billion (44% of bilateral commitments) to the health and population sectors, with the Gates Foundation accounting for 74% of the commitments to this sector. Beyond those two sectors, development priorities of private foundations were dispersed over a multitude of sectors, such as agriculture, government and civil society, education, banking and business services, and general environmental protection. Moreover, 27% of foundations’ bilateral allocable development finance had gender equality and women’s empowerment as a primary or secondary objective.

In 2019, ODA in support of the environment and climate change increased slightly. DAC countries committed 35.3% of their bilateral allocable aid (USD 37.3 billion) in support of the environment as either a principal or significant objective (a small increase from 2018), while 9.7% focused on environmental issues as a principal objective only. Twenty-seven per cent of bilateral allocable ODA (USD 28.6 billion) focused on climate change as either a principal or significant objective, a small increase from 26% in 2018. Japan (45.8%), France (43.5%), Germany (42.0%), Iceland (40.8%) and the Netherlands (35.5%) are the top 5 DAC providers to climate change. Compared to 2018, 2019 commitments to climate change as a share of their bilateral allocable ODA declined the most (by more than 5 percentage point) in Canada (from 24.4% to 15.8%), Japan (from 52.5% to 45.8%), Poland (from 36.9% to 7.6%), Slovenia (from 43.9% to 27.2%), Spain (from 26.3% to 15.8%) and Sweden (from 40.4% to 32.7%). DAC countries focused more on mitigation (19.5% in 2019) than on adaptation (14.6%). Learn more about climate-related development finance and see box The new OECD guidance on strengthening climate resilience on OECD guidance on strengthening climate resilience.

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the need to build for multi-sector resilience. For climate change, it will be important to take into account the lessons of the pandemic such as the value of early warning systems and alertness/preparedness, and to prepare for what is a well-known climate risk. Recent OECD guidance on Strengthening Climate Resilience provides governments and providers of development co-operation with guidance for strengthening the resilience of human and natural systems to the impacts of climate change. It highlights key mechanisms and enablers such as the integration of climate risks into financial management and technologies in support of climate resilience to foster country-led, inclusive and environmentally sustainable action towards a climate-resilient future.

In 2019 support to fragile contexts, which are the 57 countries and territories identified in States of Fragility 2020, accounted for 33.3% of DAC countries’ gross bilateral ODA (USD 39.2 billion) and 72.3% of gross bilateral ODA (USD 11.6 billion) of other official development co-operation providers. Support from multilateral organisations, including the EU, amounted to an additional USD 32.0 billion. Extremely fragile contexts are prominent recipients of ODA: in 2019, those 13 contexts received 37.8% of DAC countries’ and 82.6% of other official development co-operation providers’ total ODA to fragile contexts. The vast majority (73%) of other official development co-operation providers’ bilateral ODA to extremely fragile contexts was humanitarian, while DAC member countries allocated 26.7% of their bilateral ODA to the humanitarian pillar. Syria, Afghanistan, Yemen, Bangladesh and Ethiopia (in descending order) were the top recipients in 2019, together accounting for 40.8% of the total support to fragile contexts from DAC countries and other official providers.

Given the clear links between development and peace, most official providers of development co-operation are focusing their ODA in fragile contexts, where violent conflict, forced displacement and other issues are concentrated. The implementation of the 2019 DAC Recommendation on the Humanitarian-Development-Peace (HDP) nexus is helping to strengthen dialogue among these providers. Additionally, programme design and instruments are being adapted to ensure the early engagement of ODA in crisis settings beyond humanitarian assistance, which increased by 57% from 2010 (USD 6.7 billion) to 2019 (USD 10.5 billion) in fragile contexts. ODA investments in peace are especially important in this regard, although they declined from 16% in 2010 (USD 6.4 billion) to 13% in 2019 (USD 5.0 billion). In fragile contexts, DAC countries gave 26.7% of their gross bilateral ODA to the humanitarian pillar of the HDP nexus, 60.6% to development and 12.7% to peace. As part of peace ODA, ODA to conflict prevention totalled USD 1.5 billion in 2019, or 3.9% of DAC countries’ gross bilateral ODA to fragile contexts. The low share of ODA to conflict prevention is striking given the well-known returns on investment to preventing violent conflict and fragility. Implementing the HDP nexus and addressing the drivers of fragility means embracing an approach of prevention always, development wherever possible and humanitarian action where necessary.

Moreover, USD 1.9 billion was mobilised from the private sector for fragile contexts by DAC countries’ development finance interventions. Over half of this amount related to projects in Nigeria, Pakistan, Cote d’Ivoire and Bangladesh. In addition, private philanthropic foundations provided USD 1.4 billion for fragile contexts in 2019, accounting for 17% of their gross bilateral development finance. Nigeria, Kenya and Ethiopia together received 44% of foundations’ total finance for fragile contexts, largely driven by commitments from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Learn more about support to fragile contexts on the States of Fragility platform.

Notes: HDP: humanitarian-development-peace. The chart represents only gross bilateral official development assistance that is allocated by country.

In 2019, DAC countries committed 41.6% of bilateral allocable aid (USD 43.0 billion) to gender equality and women’s empowerment as either a principal (dedicated) or significant objective (integrated/mainstreamed), down slightly from 42.1% (USD 41.9 billion) in 2018.4 Only 5.5% of DAC commitments had gender equality as a principal objective, up from 4% in 2018. The top 5 DAC supporters of gender equality and women’s empowerment as a principal objective are Canada (27.6%), Sweden (21.0%), Spain (18.7%), Iceland (17.1%) and Ireland (14.1%). The proportion of bilateral allocable aid for gender as a principal and significant objective decreased the most between 2018 and 2019 in: Australia (from 44.0% to 37.9%), Japan (from 65.7% to 33.0%), the Slovak Republic (from 51.0% to 36.4%), Spain (from 61.8% to 41.2%) and Sweden (from 86.8% to 79.0%).

Funding for gender equality remains particularly high within social sectors (66.9%) and education (59.7%), particularly for DAC countries. However, for other sectors, particularly economic infrastructure, the focus on gender remains lower, at 30.7%. Many countries buck the trend for all three of these less prominent sectors in gender focus. For economic infrastructure, Belgium, Canada and the Netherlands stand out as focusing 90% of their funding within this sector on gender. See more on OECD work on gender and development co-operation in box Coming up in 2021: New DAC guidance on gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls in development co-operation.

In 2019, three other official development co-operation providers (Lithuania, Romania and the United Arab Emirates) reported against the gender marker and committed on average 70.4% of bilateral allocable aid (USD 924.3 million) to gender equality and women’s empowerment as either a principal or significant objective (up from 17.1% in 2018). Of bilateral allocable aid, 39.3% was committed to gender equality and women’s empowerment as a principal objective. The United Arab Emirates provided the highest volume and share among other official development co-operation providers. The share of the United Arab Emirates (41.3%) was also higher than any DAC provider, and largely contributed to the increase, with the United Arab Emirates reporting better on gender markers.

Moreover, private philanthropic foundations committed USD 2.4 billion for gender equality and women’s empowerment (27% of bilateral allocable commitments) in 2019, mostly integrated as part of their finance for the health and population, agriculture, government and civil society, and education sectors. Two-thirds of finance provided for gender equality and women’s empowerment by private philanthropic foundations were provided by the BBVA Microfinance Foundation, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the MasterCard Foundation.

The 2030 Agenda aims for a world in which every woman and girl enjoys full gender equality and all legal, social and economic barriers to their empowerment have been removed. Evidence points to the fact that doing so will accelerate progress on all the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and support a sustainable recovery following the COVID-19 crisis. The OECD policy brief ”Response, recovery and prevention in the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in developing countries: Women and girls on the frontlines” focuses on how to ensure a gender lens is well-integrated through response and recovery, and prevention efforts to COVID-19 in development co-operation. To support development partners’ efforts, the DAC is also preparing new guidance on gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls in development co-operation. Learn more about the DAC Network on Gender Equality and its different areas of work including development finance for gender equality, gender equality in fragile contexts; women’s economic empowerment and ending sexual exploitation, abuse, and harassment in development and humanitarian assistance.

Only 12.2% of finance mobilised by DAC countries from the private sector in 2018-19 that is channelled/earmarked to specific countries targeted the LDCs and other LICs, while 87.8% targeted middle‑income countries. Eight DAC countries (Finland, Ireland, Korea, Luxembourg, Norway, Portugal, the Slovak Republic and Sweden) found ways to manage higher risk thresholds and use other incentives to mobilise over one-third of this finance from the private sector for the LDCs. Four of these countries rely on simple co-financing arrangements as their primary leveraging mechanism (Ireland, Korea, Luxembourg and the Slovak Republic), and two (Finland and Portugal) primarily rely on direct investment in companies and special purpose vehicles. Transparency on these activities is key to build private investors’ confidence and stimulate the mobilisation effect of development finance interventions in countries the most in need.

In 2019, development finance institutions, development agencies and other institutions working with the private sector from DAC countries mobilised USD 13.8 billion of private finance mainly through guarantees, direct investment in companies or project finance special purpose vehicles, simple co-financing, credit lines, shares in collective investment vehicles and syndicated loans. This is a substantial increase from 2018 (USD 10.3 billion), driven mostly by a growth in guarantees. Guarantees leverage the most private finance (USD 6.1 billion). There is variation in the leverage mechanism that DAC countries use, with several countries (the Czech Republic, Ireland, Korea, Luxembourg, the Slovak Republic and Slovenia) mobilising 100% of their private finance through simple co-financing arrangements, such as public-private partnerships.

In 2019, private finance mobilised by DAC countries related mainly to activities in the banking and business services (46%); energy (21%); industry, mining and construction (14%); agriculture, forestry and fishing (4%) and transport and storage (4%). Learn more about the amounts mobilised from the private sector for development.

← 1. ODA was stable on a flow basis. The video OECD ODA Statistics: Introducing the grant equivalent explains the difference between the two measures.

← 2. These estimates are based on official government reports, complemented by contributions to UN agencies (excluding local resources) compiled by the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs and web-based research (mainly on contributions to multilateral organisations) in an internationally-comparable manner, and are as such not necessarily comparable with ODA figures.

← 3. The coverage of the DAC Recommendation on Unying Official Development Assistance was expanded to include other low-income countries and IDA-only countries and territories, which added a further 10 countries, bringing the total up to 65 countries covered.

← 4. The use of the recommended minimum criteria for the marker by some members in recent years can result in lower levels of aid reported as being focused on gender equality.