This chapter presents the key findings and recommendations of the Development Strategy Assessment of the Eastern Caribbean. It starts with a brief history of the economic development of the OECS region, describes key trends affecting the member states of the OECS and provides an overview of the OECS Development Strategy. The chapter then presents key strategic priorities for the member states of the OECS. These priorities include investment in renewables, closing the skills gap in the region and enhancing the quality of education, resilience to natural disasters, a sustainable ocean economy hub, digital services, better policy implementation and regional integration.

Development Strategy Assessment of the Eastern Caribbean

1. Overview

Abstract

1.1. A brief history of development in the OECS region

The diverse member states of the OECS are endowed with rich natural endowments, and enjoy good levels of GDP per capita. The OECS has seven founding members, which enjoy full membership: Antigua and Barbuda, Dominica, Grenada, Montserrat, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Lucia and St. Vincent and the Grenadines. In addition, Anguilla, The British Virgin Islands, Martinique and Guadeloupe are associate members. The OECS full members together with Anguilla share a common currency through the Eastern Caribbean Currency Union (ECCU). OECS islands are of volcanic origin, and most of the OECS member states are endowed with considerable geothermal resources and fertile volcanic soils. In addition, OECS countries enjoy strong solar radiation and high wind speeds, which could be leveraged for the development of solar and wind energy. OECS countries’ location and rich ocean biodiversity open up opportunities in the sustainable ocean economy. Moreover, all OECS member states already enjoy relatively high levels of GDP per capita. They fall into the upper middle and high-income bands, ranging in this regard from about 7 000 US dollars (USD) per capita in the case of Dominica and St. Vincent and the Grenadines (at constant 2015 terms), to USD 18 000 per capita in St. Kitts and Nevis (also at constant 2015 terms).

Since becoming independent in the 1970s and early 1980s, OECS countries have made important progress in human and social development. Indeed, they perform well in delivering access to primary and secondary education. Rates of enrolment and completion for both primary and secondary schooling are high across the region, and enrolment in secondary education has almost doubled in the region since the 1970s. Moreover, there have been important improvements in antenatal care, and rates of maternal, infant and neo-natal mortality are relatively low. These rates have declined substantially in most countries in the region since the 1980s, but there is variation across member states, and scope for further improvements.

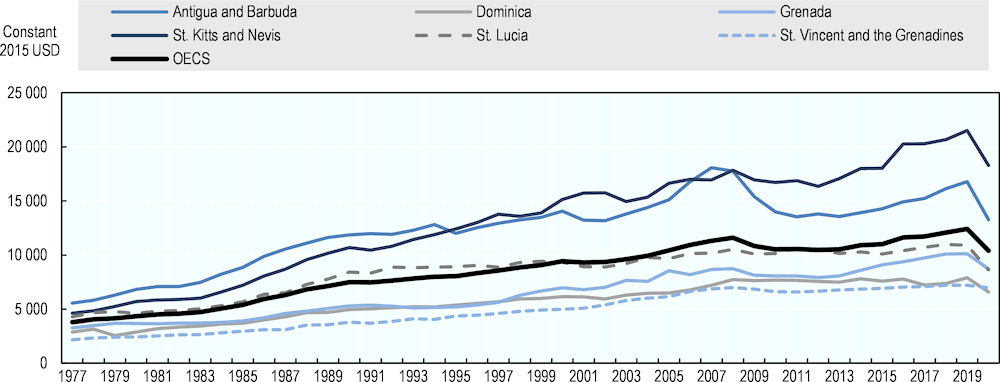

Figure 1.1. The OECS region has enjoyed good growth in incomes for much of the past 50 years, but has been facing a slowdown more recently.

Source: World Bank (2022[1]), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators.

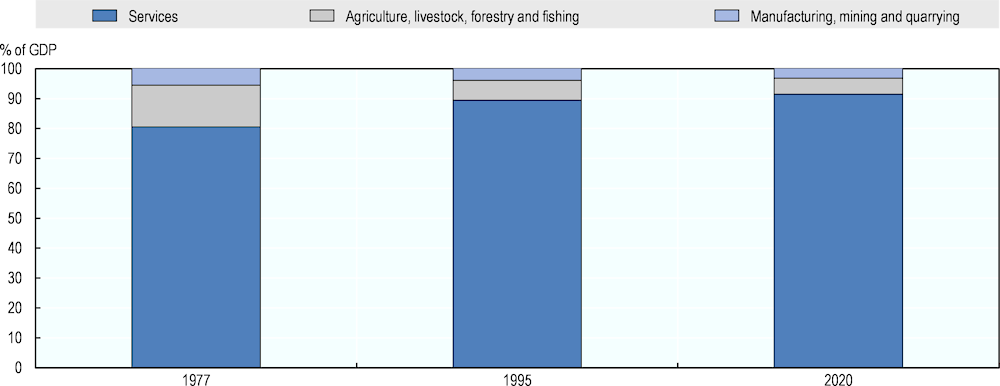

From the foundation of the OECS through to 2008, member states enjoyed high economic growth rates that saw them triple their GDP per capita, while adapting from cash crops to tourism as the main economic activity. Average GDP per capita in the OECS region increased from 3 803 in 1977 to 11 596 in 2008 (in constant 2015 terms, USD) (Figure 1.1). Growth had initially been driven by cash crops that enjoyed preferential access to European and US markets. With the creation of the WTO in 1995, however, this special access began to be phased out, with significant ramifications (Box 1.1). Following the resulting decline of agricultural exports from the OECS region, the tourism industry took over as the main engine of growth for most countries (Figure 1.2). As of today, tourism accounts on average for 45.6% of OECS countries’ GDP, and 57.5% of employment (WTTC, 2022[2]). Meanwhile, other sectors of the economy have remained relatively small in size.

Figure 1.2. There has been an expansion in services and a decline in agriculture in the OECS region.

Source: ECCB (2022[3]), ECCB Statistics Dashboard (database), https://www.eccb-centralbank.org/statistics/dashboard-datas/.

Box 1.1. Cash-crop production in OECS countries in the second half of the 20th century

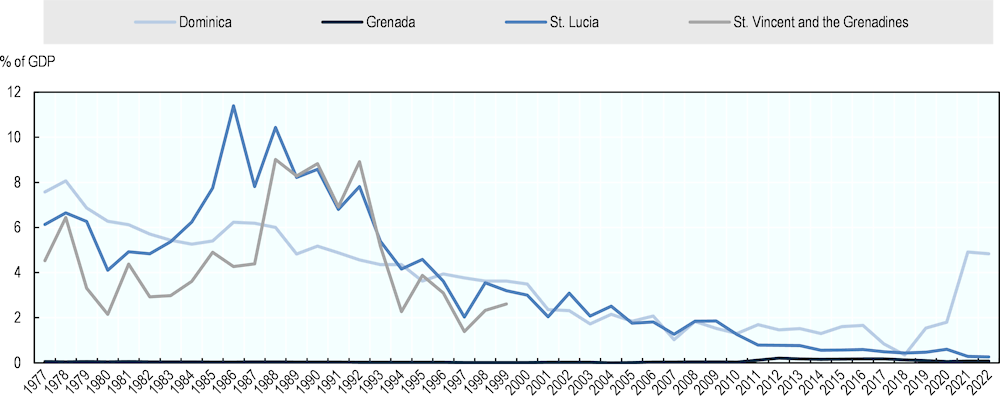

Fuelled by preferential export regimes offered by EU countries in the second half of the 20th century, the countries of the OECS developed large levels of cash-crop production, most importantly bananas. The banana-export industry started developing in the OECS member states in the early 20th century, expanding significantly in the 1950s in order to supply the United Kingdom market, and to replace sugar production, which had become unprofitable. At its peak in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the banana industry’s earnings amounted to 6-11% of GDP for St. Lucia, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, and Dominica (Figure 1.3). Grenada developed a large capacity for the production of nutmeg, which accounted for 4-5% of its GDP in the late 1970s and early 1980s. In St. Kitts and Nevis, meanwhile, the sugar industry survived longer than in other OECS countries, supported by preferential access to the EU and US markets. In the late 1970s, it still accounted for 5-8% of GDP in St. Kitts and Nevis. Before the introduction of the EU Single Market in 1992, each European country had its own banana-importing regime based on historical relationships with former colonies. Following the introduction of the EU Single Market, however, these regimes were reformed, and a single EU-wide banana-import regime was introduced, under which African, Caribbean and Pacific countries benefited from a duty-free export quota to the EU. Under this new regime, the price of bananas in the EU was approximately 80% above the world (free-market) price.

Figure 1.3. OECS countries’ banana sectors have been in decline since the early 1990s

Note: No data were available for St. Vincent and the Grenadines for 1999 to 2022.

Source: ECCB (2022[3]), ECCB Statistics Dashboard (database), https://www.eccb-centralbank.org/statistics/dashboard-datas/.

Following the dissolution of the EU’s preferential export regime, OECS countries’ agricultural exports plummeted, and their production of cash crops declined. The EU started to gradually reform and phase out the banana regime between 1999 and 2006, following the creation of the WTO in 1995, and also in the wake of trade disputes with Latin American countries and the United States. The first round of banana-regime reforms in the 1990s caused a dip in agriculture revenues and dampened rates of export growth. Without the EU’s preferential export regime, OECS countries’ banana industries were no longer profitable.

Due to the small size of banana farms in the Windward Islands, a topography that is characterised by steep hillsides and narrow valleys, and a less favourable set of climatic and labour conditions, yields per acre are significantly lower than in other Caribbean and Latin American banana-producing countries, while production costs are higher.

Source: IMF (2010[4]), Caribbean Bananas: The Macroeconomic Impact of Trade Preference Erosion, https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/journals/001/2010/059/article-A001-en.xml; World Bank (2005[5]), Sugar in the Caribbean: Adjusting to Eroding Preferences, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/pt/652531468229145599/pdf/wps3802.pdf; ECLAC (2008[6]), Impact of Changes in the European Union Import Regimes for Sugar, Banana and Rice on Selected CARICOM Countries, https://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/3173/LCcarL168_en.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y; Williams and Darius (1998[7]), Bananas, the WTO and adjustment initiatives in the Eastern Caribbean Central Bank area, ECLAC, https://www.academia.edu/57017471/Bananas_the_Wto_and_Adjustment_Initiatives_in_the_Eastern_Caribbean_Central_Bank_Area; ECCB (2022[3]), ECCB Statistics Dashboard (database), https://www.eccb-centralbank.org/statistics/dashboard-datas/.

However, the global financial crisis of 2008 and the COVID-19 pandemic both hit the OECS region hard, highlighting mounting volatility and over-dependence on single sectors. During both of these crises, the region experienced one of its strongest contractionary periods, as the demand for tourism fell. OECS countries were amongst those Caribbean nations, which were hardest hit by the COVID‑19 pandemic. They experienced contractions between 11% and 20% of GDP in 2020 (IMF, 2022[8]). These extreme events underscored the extent to which a reliance on single economic sectors makes OECS countries highly vulnerable to external economic shocks.

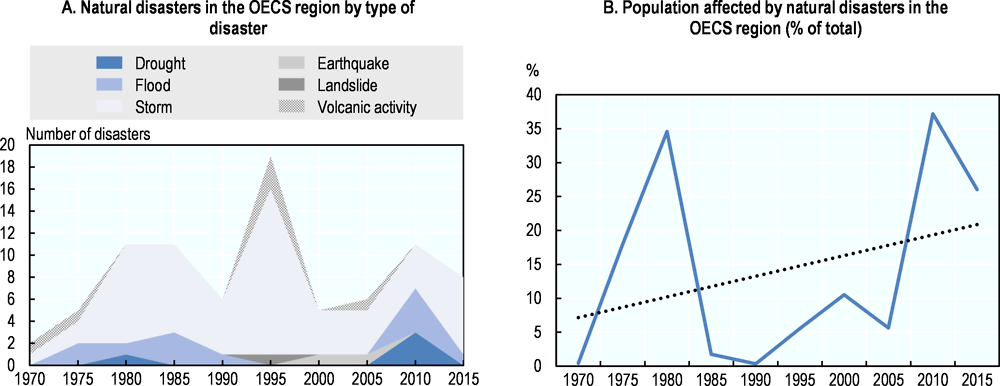

Frequent natural disasters create additional volatility and vulnerability. OECS countries are highly vulnerable to natural disasters due to their geography and their small size. Climate change is exacerbating their vulnerability to natural disasters by compounding both the number and the intensity of such disasters. Natural disasters are very costly for the region, negatively affecting tourist arrivals and economic growth. For example, Dominica experienced back-to-back hurricanes in 2015 and 2017 that destroyed almost 90% of the island’s infrastructure, and took a heavy toll on tourist numbers and economic and productivity growth (IMF, 2019[9]).

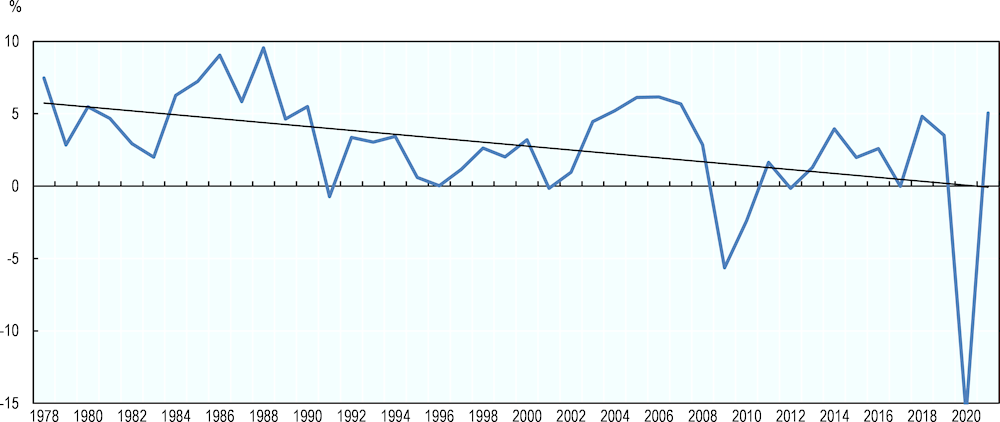

Figure 1.4. The OECS region enjoyed high growth rates in the second half of the 20th century, but more recently it has experienced a slowdown and an increase in volatility

Source: ECCB (2022[3]), ECCB Statistics Dashboard (database), https://www.eccb-centralbank.org/statistics/dashboard-datas/.

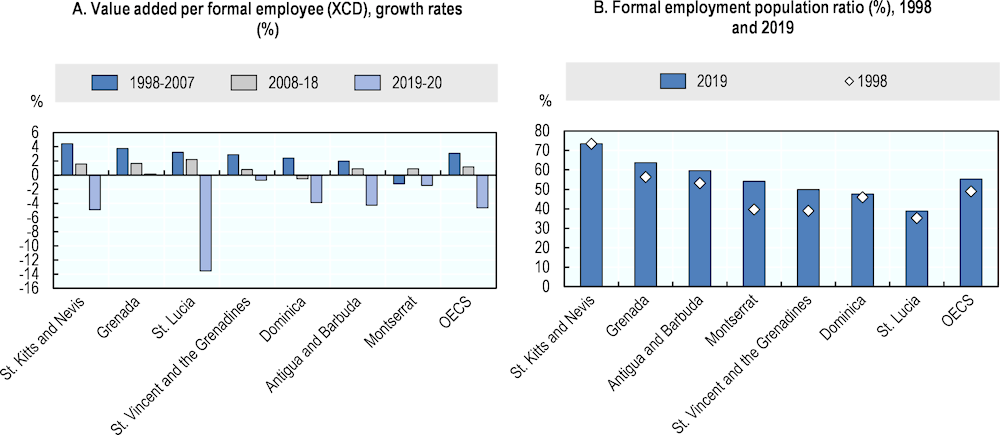

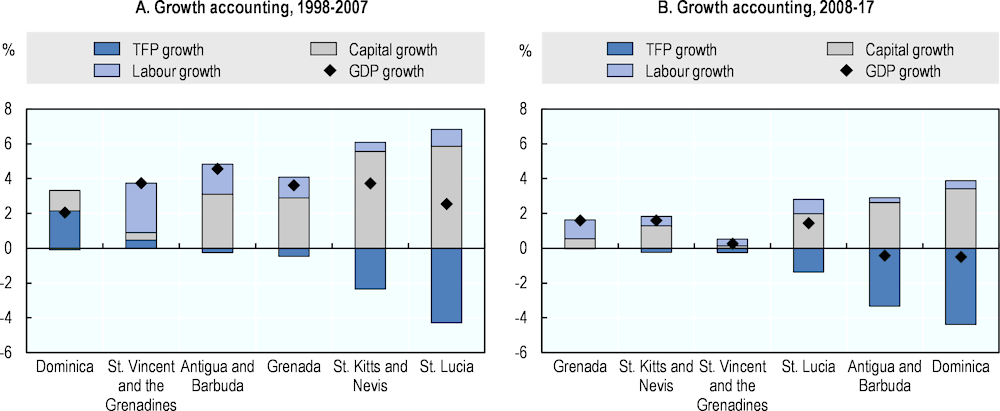

Looking ahead, new sources of productivity are necessary to overcome volatility and a declining trend in economic growth. The annual rate of GDP growth in the OECS region dropped across countries in the region from an average of 5.8% in the 1980s to 2.1% in the 1990s, before reaching a historical low of 1.7% in the 2010s (Figure 1.4) (ECCB, 2022[3]). Similarly, the growth in value-added per worker also declined (Figure 1.5, Panel A), even as the capacity of employment generation remained unchanged (Figure 1.5, Panel B). Moreover, wage growth has been outpacing labour productivity growth in most OECS countries, and this has added to the region’s employment challenges. A deeper analysis of productivity trends yields an even more concerning result, namely that growth in total factor productivity has been negative. The effect of this has been to reduce the possible gains that investments in capital and skills can yield (Figure 1.6). An analysis by the IMF, which adjusts the physical capital stock for the impact of hurricanes and other natural disasters, arrives at similar results (IMF, 2017[10]).

Figure 1.5. Formal labour productivity growth declined during the 2008 global financial crisis, and picked up recently

Note: Formal employment is a proxy for full employment figures. Instead of for 1998-2007, the data in panel A for Dominica are for 1999-2007, while for Montserrat they are for 2004-07.

Source: Authors’ own calculations based on data obtained from National Social Security Boards of OECS countries; ECCB (2022[3]), ECCB Statistics Dashboard (database), https://www.eccb-centralbank.org/statistics/dashboard-datas/; United Nations (2022[11]), “World Population Prospects 2022”, https://population.un.org/wpp/.

Figure 1.6. There has been little growth in total factor productivity in recent decades

Note: For Panel A, Dominica’s time period is 1999-2007 instead of 1998-2007. Calculations are based on a Cobb-Douglas production function and consider changes in growth rates of the capital stock, labour and GDP over time. The labour share is estimated using the number of formal employees from social security board data and wages taken from an online survey.

Source: Authors’ own calculations based on data obtained from National Social Security Boards of OECS countries; ECCB (2022[3]), ECCB Statistics Dashboard (database), https://www.eccb-centralbank.org/statistics/dashboard-datas/; Salary Explorer (2022[12]), Salary and Cost of Living Comparison, http://www.salaryexplorer.com/; IMF (2022[13]), Infrastructure Governance (database), https://infrastructuregovern.imf.org/.

In recent decades, declining economic growth rates and limited productivity growth have contributed to significant social challenges in the region. Declining growth rates, and the region’s limited economic diversification, have resulted in a lack of economic opportunities and quality jobs in the region. In turn, and in combination with structural challenges including rigidities in the labour market and a mismatch in skills, this has led to persistently high unemployment rates in recent decades (14.1% on average in the OECS region in 2020 or the latest available year), and in particular for the young (26.5% on average). Together with limited social safety nets, high unemployment has contributed to persistent levels of poverty and inequality. In turn, high youth unemployment rates and limited educational opportunities lead to crime and risk behaviour among young people. This includes criminal gangs, drug addiction, and drug trafficking.

Aside from innovation and the generation of new economic capabilities, investment in skills and reforms to governance, tax and cost structures are actions that can boost productivity. When it comes to skills, an inadequately educated workforce is indeed one of the main obstacles for private firms in the Eastern Caribbean. In particular, there is a shortage of soft and technical skills. Moreover, the quality of education continues to be a cause for concern. Furthermore, administrative procedures tend to be long and onerous in the OECS region, and business costs are considerable, particularly for energy and transport. Corporate taxes and import duties are both relatively high in the region, and many tax incentives are given out in an ad-hoc manner.

Looking to the future, regional co-operation, the development of renewable energy, improvements to human capital, and a greater resilience to natural disasters all have potential to boost growth and productivity in the region. Regional co-operation, for example, could help to enhance efficiency both in regulation and in the delivery of public services, thanks to economies of scale. This could take the form of a regional competition framework, and a region-wide regulation of the energy sector. Meanwhile, renewable energy represents an opportunity for reducing high energy prices in the OECS region, thereby enhancing its competitiveness and attractiveness for private investment. Furthermore, a larger and better offering in terms of tertiary, vocational and adult education, plus improved information on the skills that are in demand, could close the skills gap and strengthen human capital. Finally, building resilience to natural disasters could reduce the impact of negative shocks to the region’s growth and productivity.

Building a more competitive tourism sector, and diversifying into more innovative sectors such as digital services and the sustainable ocean economy, herald other important opportunities for the OECS region. The amount of value-added from tourism could be boosted through the sale of more local products to the tourism industry, and also by developing new segments of the tourism market. Moreover, reducing business costs could make the tourism sector more competitive. In the telecommunications sector, regulatory reform could facilitate the expansion of digital services. Furthermore, a regional sustainable ocean economy hub could promote education and research in a variety of fields.

1.2. Future trends

This section presents the key domestic and international trends that are likely to impact the OECS region in the near to medium term. Climate change, an ageing population, and a brain drain of skilled workers seeking opportunities overseas currently pose significant challenges for the OECS region, and these are likely to persist and intensify in the future. Thus, developing appropriate responses to those challenges is vitally important for fostering economic growth and development. In addition, digitalisation also offers new opportunities, but it requires an appropriate enabling framework.

1.2.1. Climate change and more frequent and intense natural disasters

OECS countries are highly vulnerable to climate change due to their location, geography, small size, and exposure to natural disasters. OECS member states lie in the Atlantic hurricane belt and, as is the case for other members of the Small Island Developing States (SIDS) grouping, are highly prone to natural disasters such as floods, storms and volcanic disruptions. The OECS countries’ small size, and their concentration of economic activity in a very limited area, means that losses and damages are high relative to GDP whenever a hurricanes strikes. Natural disasters – particularly hurricanes and floods – have been increasing in recent decades because of climate change, and they are likely to become even more frequent in the future (Figure 1.7). In turn, the economic shocks caused by more frequent and intense natural disasters could lead to greater volatility in economic growth. They could also further degrade public finances, which are already strained in some OECS countries because of the COVID-19 pandemic and past natural disasters (World Bank, 2022[1]; OECD/The World Bank, 2016[14]). As small island states, the OECS countries are also highly exposed to rising sea levels and ocean acidification (World Bank, 2018[15]).

In light of climate change, building resilience to natural disasters is more essential than ever. In this regard, developing disaster-resilient infrastructure is an important way to build up countries’ ex-ante resilience to natural disasters, and to reduce risks. Meanwhile, strengthening public finances is also important in order to make it possible for governments to provide counter-cyclical fiscal spending, relief measures, and rapid reconstruction when a natural disaster hits. Doing this includes reducing OECS countries’ levels of government debt, and ensuring the sound management of government revenues. As for ex-post resilience, this requires measures to facilitate a speedy recovery when natural disasters hit. Overall, the development and implementation of disaster-resilience strategies throughout the region, to ensure ex-ante, ex-post, and financial resilience, should be a policy priority.

Figure 1.7. As a consequence of climate change, natural disasters have been increasing in the OECS region

Source: EMDAT (2022[16]), The International Disaster Database (database), https://www.emdat.be/; United Nations (2022[11]), “World Population Prospects 2022”, https://population.un.org/wpp/.

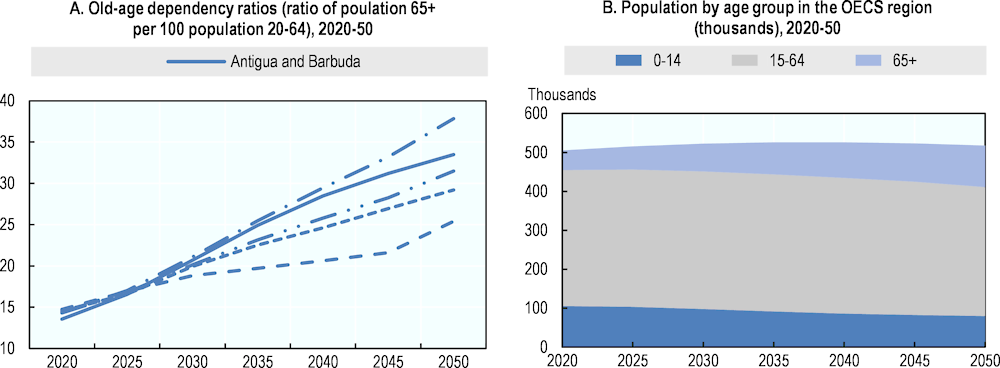

1.2.2. Rapid population ageing

OECS countries are experiencing a rapid process of demographic ageing. Driven by a rise in life expectancy and declining birth rates, there will be 35 people over 65 years old for every 100 people of working age by 2055, compared to just 14 today (Figure 1.8).

The labour market, health care and social protection will have to respond to this challenge. Efficient investments in human capital, to enhance the quality of education and close the skills gap in the region, will be essential to generate sufficient productivity growth, given the decline in the working-age population. A sustainable and universal system of social protection (including pensions, social assistance and universal health care) will also be crucial.

Figure 1.8. Demographic pressures are increasing in the OECS region

Note: OECS includes Antigua and Barbuda, Grenada, St. Lucia, St. Vincent and the Grenadines. No data available for Dominica, Montserrat and St. Kitts and Nevis. Old-age dependency ratios are defined as the population aged 65+ per population aged 15-64.

Source: United Nations (2022[11]), “World Population Prospects 2022”, https://population.un.org/wpp/.

1.2.3. Migration

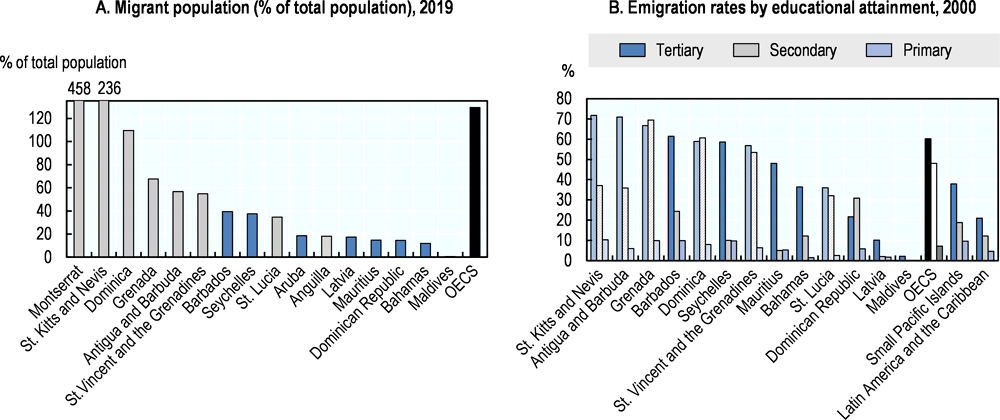

The OECS region has one of the highest emigration rates in the world, in particular for highly skilled workers with a post-secondary education (Figure 1.9, Panel B [see Box 1.2 for more information on the selection of benchmark countries]). Most OECS countries have large emigrant populations, and in Montserrat, St. Kitts and Nevis, and Dominica, the emigrant population exceeds the countries’ actual population. Emigration results in a substantial loss of human capital. Furthermore, it has a negative impact on innovation, the creation of new enterprises, and indeed on countries’ overall economic development and growth prospects. High unemployment, and the limited career prospects that stem from the conjunction of a lack of economic opportunities, natural disasters, and insecurity are the main reasons for the flight of human capital from the region (World Bank, 2008[17]; Blom and Hobbs, 2008[18]).

In order to encourage more young workers to stay in the OECS region, it will be necessary to generate more economic opportunities and to improve tertiary education. This requires both economic diversification and the generation of more value-added from tourism. At the same time, it will be essential to equip young people with the skills that are in demand in the labour market. In turn, this requires a better and larger tertiary education offering, and the collection and dissemination of information about the skills and qualifications that are in short supply in the region.

Despite its downsides, emigration does also create some opportunities through remittances and investment from the diaspora. In 2020, remittances in the OECS region ranged from 1.8% of GDP in Antigua and Barbuda to 10.4% of GDP in Dominica (World Bank, 2022[1]). They play an important role in reducing poverty and as social safety nets. Indeed, the most vulnerable and poorest segments of the population are more likely to receive remittances, and levels of poverty in the OECS region would be higher than they have been if it were not for remittances (World Bank, 2018[15]). Remittances also help to smooth out consumption in the context of shocks, and to provide indirect insurance against natural disasters, in whose aftermath they tend to increase steeply (IMF, 2017[19]). In addition, remittances can be used to finance investment, and opportunities exist in engaging the diaspora through reverse-investment schemes (World Bank, 2018[20]).

Figure 1.9. Emigration is high in the OECS region, in particular among skilled workers

Notes: OECS countries are shown in grey, the OECS average is shown in black and benchmark countries are shown in blue. See Box 1.2 for more information on the selection of benchmark countries.

Source: Docquier and Marfouk (2004[21]), Measuring the international mobility of skilled workers (1990-2000)-Release 1.0, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/14126/wps3381.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y; World Bank (2022[1]), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators.

Box 1.2. Benchmark countries

Whenever relevant and subject to data availability, the member states of the OECS are compared with three groups of benchmark countries: 1) other SIDS in Latin America and the Caribbean (Aruba, Barbados, Dominican Republic, the Bahamas); 2) SIDS in other regions of the world (Seychelles and Mauritius); and 3) Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries (Latvia). The selection of benchmark countries is based on a similarity measure. This measure provides an estimate of how similar other countries are to the OECS region comparing 13 structural and economic indicators: GDP, GDP per capita, total land area, agriculture land, total population, population density, agriculture value added (% of GDP), industry value added (% of GDP), services value added (% of GDP), trade (% of GDP), oil rents (% of GDP) and whether a country is part of the Small Island Developing State group or not. This broad set of benchmark countries can bring an additional perspective to the member states of the OECS and create valuable learning opportunities across policy dimensions.

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

1.2.4. Digitalisation

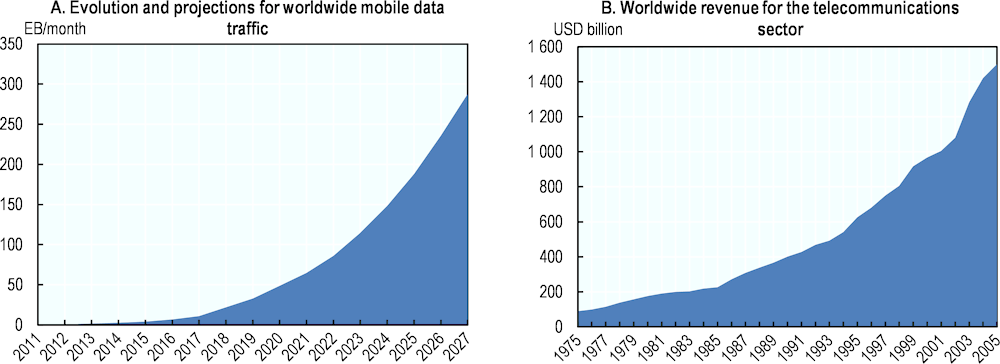

Digitalisation offers new opportunities for OECS countries. In recent decades, it has been expanding exponentially all around the world (Figure 1.10), with demand for digital services accelerating further in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic (OECD, 2020[22]; OECD et al., 2020[23]). There are opportunities to expand the digital services sector in the OECS region and digital services bring the significant advantage of eliminating transport costs, which are high in the OECS.

Figure 1.10. Digitalisation has been progressing rapidly worldwide over recent decades

Note: EB: extrabyte

Source: Ericsson; (2022[24]), Helping to shape a world of communication, https://www.ericsson.com/en; World Bank (2022[1]), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators.

To take advantage of the opportunities offered by digitalisation, OECS countries will need to improve the regulatory framework for telecommunications, invest in the skills of the workforce, and forge an appropriate digital infrastructure. The telecommunications sector presents tendencies towards a duopolistic structure across the entire OECS region. Reforms to the regulatory framework could facilitate other operators’ access to submarine fibre-optic cables and foster more competition in the sector. This would lower prices and improve the quality of service. There is also a need for improved cyber security and data protection across the region, and opportunities exist for regional co-operation. Another essential measure for seizing the full opportunities of digitalisation is to enhance digital skills among private firms and in the population as a whole, and notably to train more graduates with the technical and soft skills that are in demand from digitally-enabled industries (World Bank, 2020[25]). A reform of the regulatory framework for telecommunications is already ongoing in the Eastern Caribbean.

1.3. The OECS Development Strategy 2019-28

In response to the region’s development challenges, and to future opportunities and constraints, the OECS designed a joint ten-year development strategy for its member countries. This programme, the 2019-28 ODS, represents a systematic approach by the OECS to respond to the region’s most pressing developmental challenges at both regional and national levels. Article 13 of the Revised Treaty of Basseterre, which establishes the Eastern Caribbean Economic Union, recognises the ODS as an important framework for advancing action towards economic development through enhanced regional collaboration, and requires member states to set general and specific development objectives in line with the strategy (OECS Commission, 2018[26]).

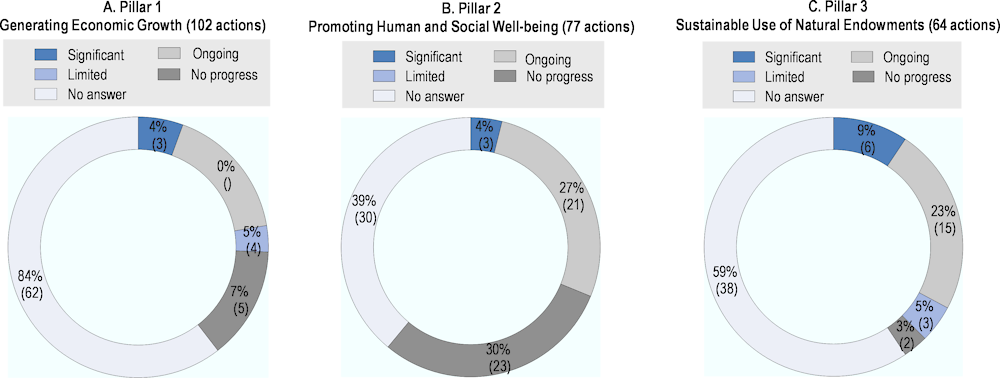

The 2019-28 ODS is based on three main pillars: Generating Economic Growth, Promoting Human and Social Well-being and the Sustainable Use of Natural Endowments. The first pillar targets an annual economic growth rate of 3-5% in order to cut unemployment by a quarter within ten years. The second pillar aims to improve quality of life in the OECS region through better access to high-quality social services, including healthcare, education, and social protection. The third pillar’s objective is maintaining environmental sustainability whilst also achieving economic growth and social development (OECS Commission, 2018[26]).

The regional strategy remains highly relevant in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. The COVID‑19 pandemic has exacerbated many of the economic and social challenges that the ODS identifies. Notably, international travel and tourist arrivals plummeted in the wake of the pandemic. As a result of OECS countries’ strong dependence on tourism and limited economic diversification, the impact of the sharp decline in tourism has been particularly severe in the region. Limited social protection, including the lack of unemployment insurance and universal healthcare, further aggravated the social impact of this economic shock, leaving vulnerable populations without income and protection. Given the effects of the pandemic, achieving the objectives of the ODS has become even more important but also more challenging.

However, the strategy lacks a clear prioritisation. Indeed, the ODS actually includes 15 strategic objectives and 91 specific objectives: 37 for the first pillar (Generating Economic Growth), 22 for the second (Promoting Human and Social Well-being), and 32 for the third (Sustainable Use of Natural Endowments). Furthermore, it includes more than 240 recommendations for policy interventions that are linked to these objectives. This large number of objectives and actions renders implementation challenging, but without the kind of clear prioritisation that would focus its practical execution.

To date, progress with implementation has remained limited. In an evaluation in autumn 2021 of progress in the implementation of policy interventions included in the ODS by the OECD, only 5% of the policy interventions in the ODS showed significant progress (3% of interventions in the first pillar, 4% in the second pillar and 9% in the third pillar). Meanwhile, 26% of interventions were ongoing (27% in the first and second pillars, and 23% in the third pillar) (Figure 1.11). The statistics also showed that 12% of interventions had made limited progress, with 3% of them registering no progress at all. Due to a lack of information, 53% of the policy interventions could not be evaluated.

The present assessment aims at filling this gap by identifying key priorities in terms of challenges and opportunities for policy action in the OECS region. Looking ahead, it would be beneficial to steer the implementation of policy towards these priorities. It is necessary, moreover, regularly to reassess and re-evaluate priorities for implementation. The regional strategy scorecard developed by the OECD provides an important tool for continuously monitoring progress towards the strategy’s implementation, and indeed for reassessing priorities for putting it into practice.

Figure 1.11. Progress in the implementation of the ODS remains limited

Note: The number of actions showing different levels of progress in implementation is shown in brackets. Information on progress in the implementation of policy interventions was provided by the OECS Commission and then evaluated by the OECD.

Source: Authors’ compilation based on an evaluation of progress in the implementation of the policy interventions included in the ODS.

1.4. Strategic priorities

This section presents a set of key priorities that OECS countries can consider as they seek to advance economic and social development. The opportunities and constraints outlined in this section can be used to set priorities in the process of implementing the OECS Development Strategy 2019-28. Making progress in these priority areas could help the OECS region to escape the traps of slow economic growth, slow or negative productivity growth, and the lack of economic and job opportunities.

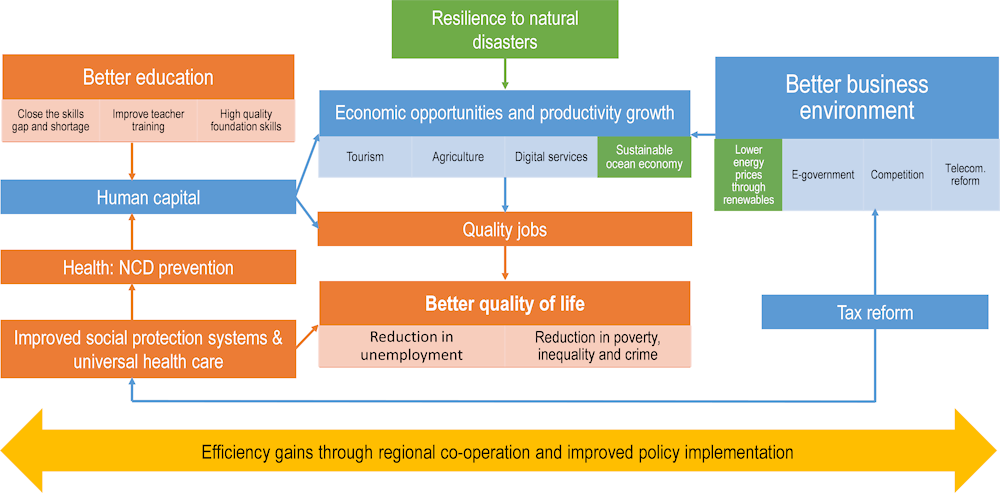

Development means improving the quality of life of citizens and generating opportunities for people in the OECS region, as well as mutual support between members of society and in the region. To improve the quality of life of citizens and generate opportunities, quality jobs and better social protection systems are both required. This would allow for reducing unemployment, poverty, inequality and related social challenges such as crime in the region. In order to create more quality jobs, in turn, countries in the region require more economic opportunities in dynamic sectors. Improving the business environment, resilience to natural disasters and enhancing human capital are key ingredients to generate more such opportunities and to stimulate productivity growth (Figure 1.12).

The COVID-19 crisis has had a substantial impact on the OECS region, but it also presents an opportunity for a strategic refocusing. Due notably to their strong dependence on tourism, OECS countries have been strongly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Indeed, international tourist arrivals plummeted in the context of the pandemic. Moreover, the social impact of the pandemic was aggravated still further by the limited social safety nets in OECS countries, which do not have universal health care or unemployment insurance. Against this backdrop, however, the pandemic does also represent an opportunity for a strategic refocusing on salient opportunities, on the implementation of reforms, and on removing identified constraints.

Figure 1.12. Improving the quality of life in the OECS region requires more quality jobs in dynamic sectors

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

1.4.1. Investment in renewables, telecommunications reform and e-government could foster productivity improvements

Renewable energy represents a key opportunity for reducing high energy prices in the OECS region. The OECS countries’ reliance on imported petroleum products for electricity generation results in high electricity prices. The low and falling worldwide costs for generating power from renewable technologies, plus the abundant renewable resources that the OECS countries possess, herald a multitude of opportunities. First of all, though, scaling up renewables in the OECS region requires a strong political will, credible long-term strategies and visions, and realistic targets for scaling up renewables. In addition, there is a need to develop financing strategies and energy-sector regulation that is conducive to private investment. Opportunities for regional collaboration exist in the development of geothermal energy and of a regulatory framework for the whole energy sector.

A regional competition framework could enhance consumer welfare and foster improvements to economic growth and productivity in the OECS region. At present, none of the OECS member states have a competition law, including a regulatory framework for controls on mergers and acquisitions (M&A). Well-designed competition law, effective enforcement, and competition-based economic reform have a critical role to play in promoting consumer welfare and economic growth, and they also make markets more flexible and innovative. A competition framework in the OECS region could foster more competition in telecommunications and other economic sectors, thereby reducing prices and increasing overall welfare. In order to take advantage of economies of scale and to pool costs, it could be beneficial for OECS countries to establish a joint regional competition framework and a joint institutional and regulatory framework for competition, energy and possibly also telecommunications. Nonetheless, such an approach requires further study and needs to be carefully assessed to determine the optimal institutional set-up for the OECS region.

Reforming the telecommunications sector could facilitate the expansion of digital services in the OECS region. The structure of OECS member states’ telecommunications sectors could pose a challenge to the expansion of digital services. This is because the telecommunications sector tends towards limited competition across the entire region. Existing regulation does not provide for regulated, affordable access to submarine cables other than by operators owning the infrastructure. Developing the regulatory framework in order to facilitate wider access to submarine fibre-optic cables represents an important opportunity. Indeed, this would foster more competition in the sector, leading to lower prices and a better quality of service, and increasing the competitiveness of the digital-services sector in the region. A reform of the regulatory framework for telecommunications is already ongoing in the Eastern Caribbean.

E-government and the digitalisation of public services present an opportunity to reduce red tape, simplify administrative procedures, and enhance transparency. Administrative procedures tend to be long and onerous in the OECS region, representing an obstacle for private companies. Customs and trade regulations tend to be particularly lengthy and costly. An at times inefficient public sector contributes to complex and onerous business procedures. At the same time, OECS countries perform moderately in terms of e-governance. In this context, the digitalisation of public services represents an opportunity to simplify business procedures and to reduce bureaucracy. Indeed, there may even be scope in some areas to build economies of scale through regional co-operation, for example by creating a shared e-government platform for all member countries. Reforms to enhance e-governance should go hand in hand with reform of the telecommunications sector.

1.4.2. Closing the skills gap, enhancing the quality of education, and better health outcomes through NCD prevention measures and universal healthcare could strengthen human capital in the OECS region

Training more skilled workers with the skills that are in demand is a key priority for stimulating private investment, reducing unemployment, and improving living conditions in the OECS region. Skilled workers tend to be better remunerated and to enjoy higher living standards. Furthermore, adequate human capital has a key role to play in the diversification of OECS economies, including in the expansion of digital services industries, and in modernising and upgrading technology in agriculture and fisheries. The availability of greater numbers of better-skilled workers in the region can also contribute to the creation of new business opportunities and jobs in skills-intensive niche industries. Furthermore, greater numbers of skilled workers would allow more businesses to invest in productivity-enhancing technological upgrades such as information and communications technology. Finally, the availability of the right skills in the OECS region could reduce upward pressure on wages, thereby reducing labour costs and enhancing competitiveness.

A larger and better offering of tertiary, vocational and adult education, plus improvements in disseminating information on the kinds of skills that are in demand, are necessary measures to pursue in order to close the skills gap in the OECS region. A skills mismatch resulting in an inadequate workforce and skills shortages present challenges for the private sector in several OECS countries. In particular, there is a shortage of technical and soft skills. The skills mismatch is the result of a limited tertiary education offering in the region, as well as of structural transformation, high emigration rates amongst young skilled workers, and cultural issues. Closing the skills gap requires an expansion and improvement of the tertiary education offering. In addition, there is a need for a better and larger offering of adult, technical and vocational education, and one that is better linked to the labour market. Better information on the skills that are in demand on the labour market, thanks to regular regional labour-market assessments and skills councils, is also essential for closing the skills gap in the region.

More and better-trained teachers, and the development of high-quality foundation skills, could enhance the quality of primary and secondary education in the OECS region, while also boosting students’ performance. The share of trained teachers in primary and secondary education is comparatively low across the OECS region. Incentives for untrained teachers to acquire qualifications faster, plus the introduction of mandatory pre-service teacher training, could raise the share of trained teachers in the region. Improving the image of the teaching profession, as well as teachers’ working conditions and salaries, could, moreover, encourage better-performing graduates to become teachers, and could also enhance teachers’ performance. Another essential measure is to ensure that primary and secondary education equips students in the region with high-quality foundation skills. This requires a better integration into school curricula of skills such as digital skills, problem-solving skills, co-operative teamwork skills, pro-activeness, and creativity. Focusing on competencies rather than exam preparation would be another important step in equipping students with high-quality foundation skills.

It would be important to prioritise policies for the prevention of non-communicable diseases (NCDs), including awareness raising, measures to encourage more physical activity, and appropriate legislation and regulation. A lower prevalence of NCDs could boost workers’ productivity and human capital. OECS countries have made important progress in antenatal and neonatal care and maternal health. However, the prevalence of NCDs is relatively high in the region. Contributing factors to the high prevalence of NCDs include an ageing population, as well as increasing levels of obesity as a result of dietary habits and insufficient physical activity, and relatively high alcohol consumption. Better prevention is key to reduce the prevalence of NCDs. Awareness rising at school, at the workplace and through mass media campaigns is an effective prevention measure. Developing and expanding existing regulation and legislation on tobacco, alcohol and food products could reduce alcohol and tobacco consumption and encourage healthier diets. Policies promoting active travel and walking could increase physical activity, thereby improving physical and mental health and reducing overweight and obesity.

In order to tackle poverty and inequality, and to boost human capital, OECS countries require better social protection systems. As a result of high unemployment rates and limited economic opportunities, levels of poverty and inequality in the OECS region are higher than in other countries with similar levels of income per capita. In addition to generating more economic opportunities and boosting human capital, the establishment of better social safety nets across the region, including universal access to healthcare and unemployment insurance schemes, would be an important step towards reducing poverty and inequalities. Furthermore, comprehensive social protection systems also have the potential to make OECS countries more resilient to natural disasters. Streamlining the multitude of social assistance programmes of the OECS region could lead to efficiency gains and cost savings. Expanding and improving access to social protection further necessitates a strategy for raising sufficient financial resources.

1.4.3. Resilience to natural disasters is a foundation of sustainable development in the OECS region

Building resilience to natural disasters is essential for reducing negative shocks to the region’s growth and productivity performance, and for advancing economic development. OECS countries are highly prone to natural disasters, and their cost for the region is high both in terms of loss of human life and economic losses due to damages. Moreover, natural disasters have a negative impact on both economic growth and productivity. Building resilience to natural disasters can help to mitigate the costs that they impose, and to reduce their negative impact both on populations and on the broader economy. In order to build this overall resilience, it is essential to ensure financial resilience, to build disaster-resilient infrastructure for ex-ante resilience, and to take measures for ex-post resilience in order to facilitate a speedy recovery after natural disasters hit. The development and implementation of disaster resilience strategies throughout the region should, therefore, be a policy priority.

1.4.4. Economic opportunities for OECS countries exist in tourism, digital services, the sustainable ocean economy and agriculture

The value-added that is generated through tourism in the OECS region could be boosted through the sale of more local products to the tourism industry, and a focus on new tourist segments. There are opportunities in selling more agricultural and fishery produce, as well as art products, both to cruise ships and the hotel sector. At present, however, spillovers and linkages between tourism and local agriculture and fisheries remain relatively limited. In addition, new tourist and traveller segments that could be targeted in the region include distance workers through digital nomad visas, medical tourism, eco-tourism, and educational tourism. Attracting a larger number of stay-over tourists would be another important way to add more value in the sector.

Digital services constitute an opportunity for diversification for OECS countries. As already noted, the demand for digital services has been growing rapidly all around the world as a result of the exponential growth of digitalisation and, more recently, in the context of the COVID‑19 pandemic. The advantage of digital services for OECS countries is the absence of transport costs, which are high in the region. Reforming telecommunications sectors in the region and establishing a competition framework are essential to render OECS countries more competitive for digital services industries.

A regional sustainable ocean economy hub could advance both education and research activities in different fields of the sustainable ocean economy. As small island nations, OECS countries have a comparative advantage for establishing such a hub, since they have abundant access to the ocean. Due to their location in the tropics, they are, moreover, endowed with a high degree of marine biodiversity, and they have extensive and valuable marine resources. In particular, marine biotechnologies are one area of the sustainable ocean economy in which opportunities abound, and there is potential in the OECS region to exploit this further. At the same time, there continues to be a shortage of qualified and skilled professionals in many sectors of the sustainable ocean economy. It appears that curricula in the field of the sustainable ocean economy such as marine sciences elicit substantial global demand from students, but academic capacity is limited. The OECS region could build on its experience of playing host to offshore medical schools in order to develop such curricula for local and international students in a regional hub.

Technological upgrades in agriculture and farmers’ organisations could open up new opportunities in food processing and sales to the tourism industry. Agricultural production in the OECS region has been decreasing over the past three decades, and agricultural productivity is relatively low in the region. The main barrier for the tourism sector in sourcing more agricultural products locally is the lack of uniformity, and the limited quality, of local products, and the lack of timely and continuous delivery. Similarly, a lack of sufficient processing facilities is an important reason why many processed (non-fresh) and semi-processed products (in particular, meat and fish) are subject to a high share of imports. Technological upgrades such as irrigation infrastructure, careful harvest planning, greenhouses, efficient irrigation systems, lab infrastructure and agro-processing facilities could enhance the productivity of the agricultural sector and the quality of agricultural produce, while also facilitating agro-processing and sales to the tourism sector. Furthermore, the organisation of smallholder farmers into groups or co-operatives, and the development of contract farming, could improve efficiency in the marketing of local produce, and may also facilitate exports. Encouraging more young people to become farmers or agro-entrepreneurs could also contribute to revitalising and transforming the region’s agricultural sectors.

Meanwhile, land reform could improve access to credit, and could also enhance private investment in agriculture. In several countries in the OECS region, unclear and uncertain land ownership rights restrict access to collateral for credit and investment in agriculture. Thus, reforming systems of land tenancy and land subdivision could improve both access to credit and efficiency. Furthermore, OECS countries require modern, compulsory systems of land registration, and they need to strengthen their institutional capacity for managing the land-registration systems that already exist. At present, the lack of such systems, and of sufficient institutional capacity, limit access to collateral for loans.

The production of higher quality fish products, fish processing, and the development of aquaculture could allow OECS countries to substitute part of their fish imports with local production. At present, the contribution of fisheries to GDP in the OECS region remains negligible. Fishing sectors play an important social role in most OECS countries, yet most of these states require considerable fish imports to complement local production and to meet local demand for fresh products. Little fish processing occurs in the region, and in most OECS countries there are no or few commercial facilities for processing fishery products. Investment in appropriate technology and infrastructure is required in order to facilitate fish processing, and to increase the quality of local fishery produce in order to then be able sell more local produce to the tourism sector. Investment in post-harvest and processing facilities such as drying equipment, ice plants, refrigeration, and cold storage facilities is particularly important. Aquaculture and sea products offer further opportunities for the OECS region. Aquaculture is seen as a sector with a large growth potential worldwide, and has expanded substantially in recent years.

1.4.5. Policy implementation and regional integration

Taking advantage of opportunities for economic and social development in the OECS region requires improvements in the implementation of policy. Indeed, effective implementation is everything. Without it, any policy, law or regulation remains just a piece of paper, and a mere proof of intentions. Implementation is also the most challenging part of any strategy. In all areas of this report, policy implementation and regulation surface as constraints in the OECS region. A short-term horizon, a large government apparatus, too much discretion in decision making, and the limited availability of data hinder the effective implementation of policy in the OECS region.

The regional strategy scorecard developed by the OECD could improve the effectiveness of policy implementation in the region. Transparent and objective scorecards can improve the alignment of incentives for different actors, as well as enhancing the monitoring and evaluation of policy implementation, and strengthening rules-based governance. In order to support the effective implementation of policy in the OECS region, the OECD has, therefore, built a regional strategy scorecard for OECS member states. This scorecard is closely aligned with the 2019-28 ODS, and consists of 40 high-level indicators, with country-specific targets for 2030 linked to the three pillars of the strategy. The scorecard aims to create commitment to ambitions through measurable targets, tracking progress towards these targets and holding policy makers accountable for results. Going forward, and in order to improve implementation, it will be essential regularly to update the scorecard, and to adjust policy priorities based on how much progress has been made towards the targets that the scorecard has set. Another important step would be to fill gaps in the data that is available, and to improve the availability of data across the region, since limitations in this regard have constituted an important challenge for designing and regularly updating the scorecard.

Due to economies of scale, regional co-operation heralds numerous opportunities for efficiency gains in regulation and implementation. The small size of the individual OECS economies results in a lack of scale for offering a large number of public services or establishing regulatory institutions. Moreover, regional collaboration can prevent so-called collective action problems. A consistent regulatory framework across the region could also potentially reduce the level of regulatory discretion. Examples of potential policy areas where regional collaboration could prove to be beneficial by generating economies of scale include laboratory infrastructure for the quality control of agriculture and food products, crop research, cyber security and data protection, competition regulation, e-governance, and a regional fast-ferry service. They also include tertiary educational curricula and the development of courses in different subject areas, as well as tackling crime, regulating the energy sector, and developing geothermal energy.

References

[18] Blom, A. and C. Hobbs (2008), “School and Work in the Eastern Caribbean - Does the Education System Adequately Prepare Youth for the Global Economy?”, World Bank Country Study, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/6375.

[21] Docquier, F. and A. Marfouk (2004), Measuring the international mobility of skilled workers (1990-2000)-Release 1.0, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/14126/wps3381.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 26 July 2022).

[3] ECCB (2022), ECCB Statistics Dashboard, Eastern Caribbean Central Bank, https://www.eccb-centralbank.org/statistics/dashboard-datas/ (accessed on 9 July 2022).

[6] ECLAC (2008), Impact of Changes in the European Union Import Regimes for Sugar, Banana and Rice on Selected CARICOM Countries, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, Port-of-Spain, Trinidad and Tobago, https://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/3173/LCcarL168_en.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

[16] EMDAT (2022), The International Disaster Database (database), EMDAT, https://www.emdat.be/.

[24] Ericsson (2022), Helping to shape a world of communication, https://www.ericsson.com/en (accessed on 8 August 2022).

[13] IMF (2022), Infrastructure Governance (database), https://infrastructuregovern.imf.org/ (accessed on 8 August 2022).

[8] IMF (2022), World Economic Outlook Database, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/SPROLLs/world-economic-outlook-databases#sort=%40imfdate%20descending.

[9] IMF (2019), East Caribbean Currency Union - Selected Issues, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Books/Issues/2018/02/26/Unleashing-Growth-and-Strengthening-Resilience-in-the-Caribbean-44910.

[10] IMF (2017), “Productivity and potential output in the ECCU”, https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/journals/002/2017/151/article-A001-en.xml (accessed on 1 May 2022).

[19] IMF (2017), Unleashing Growth and Strengthening Resilience in the Caribbean, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Books/Issues/2018/02/26/Unleashing-Growth-and-Strengthening-Resilience-in-the-Caribbean-44910.

[4] IMF (2010), Caribbean Bananas: The Macroeconomic Impact of Trade Preference Erosion, https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/journals/001/2010/059/article-A001-en.xml.

[5] Mitchell, D. (2005), “Sugar in the Caribbean: Adjusting to Eroding Preferences”, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 3802, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/pt/652531468229145599/pdf/wps3802.pdf.

[22] OECD (2020), “Digital Transformation in the Age of COVID-19: Building Resilience and Bridging Divides”, Digital Economy Outlook Supplement, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/digital/digital-economy-outlook-covid.pdf.

[23] OECD et al. (2020), Latin American Economic Outlook 2020: Digital Transformation for Building Back Better, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/e6e864fb-en.

[14] OECD/The World Bank (2016), Climate and Disaster Resilience Financing in Small Island Developing States, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264266919-en.

[26] OECS Commission (2018), OECS Development Strategy: Shaping Our Shared Prosperity, Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States, https://oecs.org/en/oecs-development-strategy (accessed on 10 July 2022).

[12] Salary Explorer (2022), Salary and Cost of Living Comparison, http://www.salaryexplorer.com/ (accessed on 26 July 2022).

[11] United Nations (2022), World Population Prospects 2019, webpage, Population Division, United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, New York, https://population.un.org/wpp/ (accessed on 20 May 2022).

[7] Williams, O. and R. Darius (1998), Bananas, the WTO and adjustment initiatives in the Eastern Caribbean Central Bank area, ECLAC, https://www.academia.edu/57017471/Bananas_the_Wto_and_Adjustment_Initiatives_in_the_Eastern_Caribbean_Central_Bank_Area.

[1] World Bank (2022), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators# (accessed on 11 July 2022).

[25] World Bank (2020), “International Development Association Project Appraisal Document on Proposed Credits and a Proposed Grant for a Caribbean Digital Transformation Project (“Digital Caribbean”)”, Report No: PAD3724, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/848701593136915061/pdf/Dominica-Grenada-St-Lucia-St-Vincent-and-the-Grenadines-and-the-Organization-of-Eastern-Caribbean-States-Caribbean-Digital-Transformation-Project-Digital-Caribbean.pdf.

[15] World Bank (2018), “Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States Systematic Country Diagnostic”, Report Number: 127046-LAC, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/30054/OECS-Systematic-Regional-Diagnostic-P165001-1-06292018.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

[20] World Bank (2018), Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States Systematic Regional Diagnostic, World Bank, Washington, DC, https://doi.org/10.1596/30054.

[17] World Bank (2008), Organization of Eastern Caribbean States Increasing Linkages of Tourism with the Agriculture, Manufacturing and Service Sectors, World Bank, Washington, DC, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/7922/440600ESW0P10610Box334086B01PUBLIC1.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

[2] WTTC (2022), Tourism Trends 2022, https://www.unwto-tourismacademy.ie.edu/2021/08/tourism-trends-2022 (accessed on 11 July 2022).