This chapter discusses constraints to policy implementation in the OECS region, and how the regional strategy scorecard developed by the OECD Development Centre, OECS Commission and national focal points in OECS member states can support effective policy implementation. In all areas of this report, policy implementation and regulation have surfaced as constraints. The regional strategy scorecard is a tool to support the effective implementation of the OECS Development Strategy (ODS), through a continuous assessment of progress in terms of concrete results. It aims to use measurable targets that OECS member states have committed to to foster commitment to the ambitions of the ODS, tracking progress towards these targets, and holding policy makers accountable for results.

Development Strategy Assessment of the Eastern Caribbean

5. Strengthening implementation

Abstract

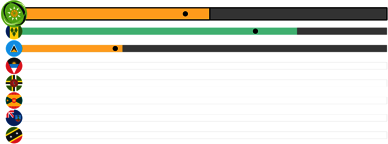

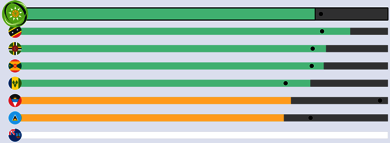

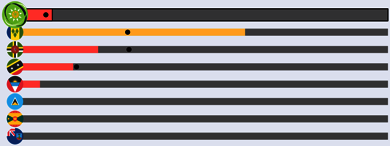

Effective policy implementation is the most challenging part of any strategy. Without it, any policy, law or regulation remains just a piece of paper, proving intentions. On the other hand, better regulation and regulatory processes can reduce impediments and strengthen policy implementation (OECD, 2021[1]). In all areas of this report, policy implementation and regulation have surfaced as constraints in the OECS region. This is reflected in OECS countries’ relatively poor performance on government effectiveness (Figure 5.1). At the same time, there are many unique opportunities to enhance the effectiveness of policy implementation and regulation, through regional co-operation. More effective public delivery and implementation, in a context of good governance, could create new opportunities for development, and could enable achievements across the range of the strategic priorities and opportunities set out in this report.

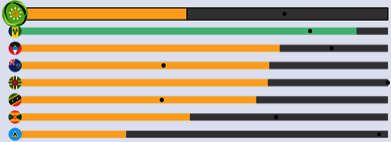

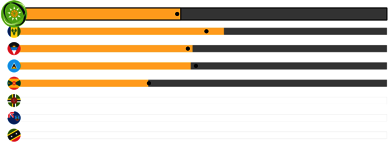

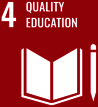

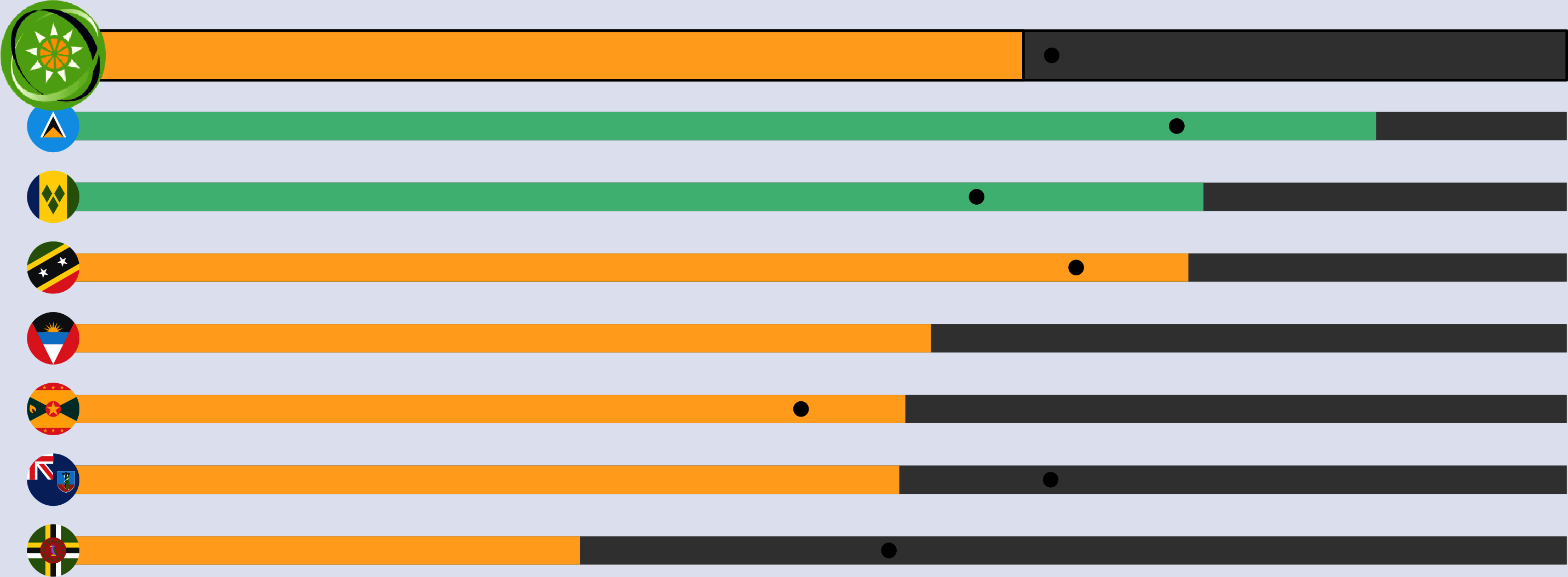

Figure 5.1. OECS countries do not perform very well in terms of government effectiveness and regulatory quality

Note: The index ranges from -2.5 (worst) to 2.5 (best). Different shadings and colours indicate OECS member states.

Source: World Bank (2022[2]), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators.

5.1. Effective policy implementation requires good data, strong, non-partisan institutions and constructive engagement with all concerned

The limited availability and quality of data in the OECS region pose a challenge to the effective monitoring and evaluation of policy implementation. With regard to the evaluation of policies and programmes, indicators that highlight the underlying problems that drive such policies, or that point to other areas of public concern, are an essential aid to policy makers (Coglianese, 2012[3]). As such, good government policies depend on sound statistics as a basis for evidenced-based decision making and accountability (OECD, 2015[4]). As a result of the small size of OECS countries, high-quality data is often scarce in the region. This is the case, for example, for employment data. Moreover, national statistics offices tend to be underfunded. Hence, there is an opportunity to generate more regular, high-quality statistics by taking advantage of the economies of scale that regional co-operation can bring. To improve monitoring and evaluation, in addition to improving data availability and quality in the region, there is also a need to think about ex-post evaluation of progress earlier in the process of designing and implementing policies.

The effective implementation of policy requires strong, non-partisan institutions, consistent reforms across policy areas, and engagement with the opponents of reforms. Reforms require strong institutions and leadership, with authoritative, non-partisan institutions that command trust across the political spectrum. Consistency of reforms across policy areas is also critical. In addition, securing buy-in and support from as wide a stakeholder base as possible, and engaging with the opponents of reform through an inclusive and consultative policy process, usually pays dividends over time, creating greater trust among the parties involved. In turn, these parties then become more willing to accept commitments on steps to mitigate the personal costs that result from the changes (OECD, 2010[5]).

5.2. The regional strategy scorecard developed by the OECD Development Centre, OECS Commission and member states is a tool to support the effective implementation of policy in the OECS region

Transparent and objective scorecards can improve the alignment of incentives for different actors, enhance the monitoring and evaluation of policy implementation, and strengthen rules-based governance. Public scorecards make it possible to monitor progress towards development objectives. Furthermore, they also constitute a mechanism of accountability for governments. It is important to ensure that indicators are easily and independently verifiable by all stakeholders.

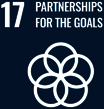

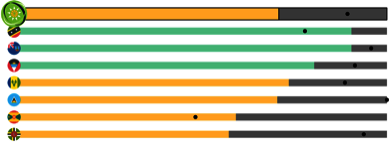

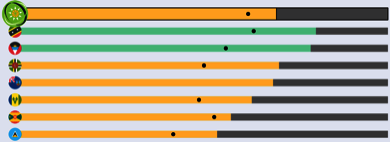

In order to support the effective implementation of policy in the region, the OECD Development Centre, the OECS Commission and focal points in member states have built a regional strategy scorecard for the OECS and its member states. The strategy scorecard is closely linked and aligned with the OECS Development Strategy 2019-28, the ODS. It constitutes a tool to support the implementation of this strategy, through a continuous assessment of progress in terms of concrete results. The scorecard is an interactive online tool, consisting of 40 indicators across the three pillars of the ODS (economy, social development, and environment), with concrete targets for 2030 for each OECS member state. All indicators are linked to one or several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The strategy scorecard aims to use measurable targets to foster concrete commitment to the ambitions of the ODS, tracking progress towards these targets, and holding policy makers accountable for results. Furthermore, it is a tool that allows policy makers to set priorities for implementation, based on measurable results and on a platform for comparing the performance of different member states and exchanging best practices and successful policies. The scorecard allows policy makers to link implementation to results, thereby evaluating and monitoring progress on the implementation of different policies, and to make adjustments when necessary. Concentrating efforts, monitoring implementation, and following up where progress is stalling, are the fundamental building blocks of successful implementation.

Indicators were selected based on the priorities laid out in the ODS, and on the availability of data. Furthermore, member states’ feedback on the choice of indicators was also taken into account whenever possible, and wherever sufficient data was available. The objective was to select a limited number of high-level indicators that would make it possible to track progress in priority areas. Economic indicators include broad indicators of income, productivity, trade, debt, digitalisation, and key economic sectors (tourism, agriculture, fisheries) (Annex Table 5.A.2. Scorecard indicators, Pillar 2: Promoting human and social well-being). Social indicators gauge the labour market, education, health and crime (Annex Table 5.A.2. Scorecard indicators, Pillar 2: Promoting human and social well-being). Key environmental indicators measure renewable energy and the sustainable ocean economy (Annex Table 5.A.3. Scorecard indicators, Pillar 3: Sustainable use of natural endowments).

The OECS member states validated all of the targets in a participatory process. National focal points for the joint project are from strategic ministries, such as the ministries of planning and economic development in OECS member states. They met on a regular basis throughout the process of designing the scorecard. In order to validate targets for the indicators in the scorecard, the OECD designed an interactive online survey for each OECS member state, which allowed the focal-point representatives to choose from different target options for each indicator.

Looking ahead, and in order to improve implementation, it will be essential to update the scorecard regularly, and to adjust policy priorities based on progress towards the targets in the scorecard. Regular updates of the scorecard will be made through the OECS Commission, with the technical support of the ECCB, and in close collaboration with OECS member states. The scorecard was officially launched at an Extraordinary Meeting of the OECS Economic Affairs Council (EAC) on 21 June 2022. Following this launch, the EAC will review the scorecard annually. This process will make it possible to adjust policy priorities for the region based on outcomes, as measured by the scorecard. It will also facilitate an exchange among the countries in the region on their progress in implementing policies. This will ensure that results are achieved in the region, and that objectives are met. In addition to the review process of the EAC, the OECS Commission will also aim at building a wider social partnership on the scorecard with labour unions, the private sector, academia and civil society.

The limited availability of data in the region has posed a significant challenge for designing and regularly updating the scorecard. For many environmental and social objectives, the necessary data for measuring results are not available. Without these data, it is impossible to engage in evidence-based policy making. To be sure, much administrative data does exist across a wide array of agencies in the OECS region, such as hospitals, registration offices, utilities, tax authorities, and social security boards. However, it is not collected and published in an accessible format, and it cannot easily be used. For the scorecard, the OECD used administrative data from social security boards on actively-insured people, in order to calculate proxy indicators for labour productivity (value-added per formal employee) and unemployment (the ratio of people in formal employment as a share of the overall population).

Filling gaps in the data, and indeed improving the availability of data across the region would be an important step forward. For some types of indicators, moreover, there are opportunities to collect and publish administrative data in an accessible format. For other indicators, such as poverty rates and employment statistics, more regular surveys are required.

References

[3] Coglianese, C. (2012), “Measuring Regulatory Performance: Evaluating the Impact of Regulation and Regulatory Policy”, OECD Expert Papers, No. 1, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/regreform/regulatory-policy/1_coglianese%20web.pdf.

[6] ECCB (2022), ECCB Statistics (database), Eastern Caribbean Central Bank, https://www.eccb-centralbank.org/statistics/dashboard-datas/.

[11] IRENA (2022), Data & Statistics, https://www.irena.org/statistics (accessed on 10 August 2022).

[1] OECD (2021), International Regulatory Co-operation, OECD Best Practice Principles for Regulatory Policy, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5b28b589-en.

[4] OECD (2015), Development Co-operation Report 2015: Making Partnerships Effective Coalitions for Action, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/dcr-2015-en.

[5] OECD (2010), Making Reform Happen: Lessons from OECD Countries, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264086296-en.

[10] PAHO (2022), ENLACE: Data Portal on Noncommunicable Diseases, Mental Health, and External Causes, Pan-American Health Organization, Washington, DC, https://www.paho.org/en/enlace (accessed on 10 July 2022).

[8] UN (2019), UN Comtrade database, https://comtrade.un.org/data/ (accessed on 3 May 2019).

[7] UNSD (2022), Statistics, https://unstats.un.org/UNSDWebsite/ (accessed on 10 August 2022).

[9] WHO (2022), The Global Health Observatory - Indicators, https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators (accessed on 11 July 2022).

[2] World Bank (2022), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators# (accessed on 11 July 2022).

Annex 5.A. Scorecard tables

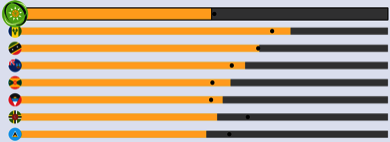

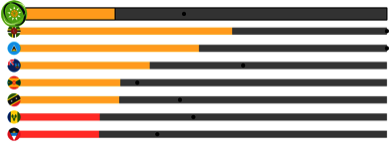

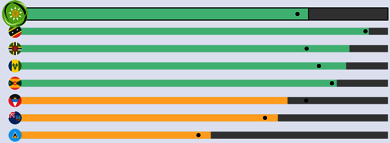

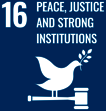

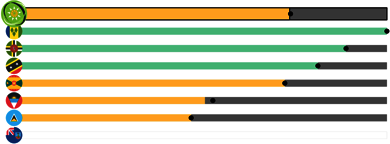

Annex Table 5.A.1. Scorecard indicators, Pillar 1: Generating economic growth

|

United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) |

Scorecard indicator |

Starting point (2020) |

Current value (2021) |

Regional target 2030 |

Regional progress |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

GDP in market prices (current XCD) (millions) |

2 249.43 |

2 373.60 |

4 265.55 |

|

|

|

GDP per capita (current XCD) |

32 178.25 |

34,020.05 |

49 056.45 |

|

|

|

Value-added per formal employee (XCD) |

61 981.90 |

- |

85 350.83 |

|

|

|

Foreign direct investment, net inflows (%of GDP) |

5.24 |

- |

13.11 |

|

|

|

Exports of goods (current USD) (millions) |

28.50 |

28.18 |

61.76 |

|

|

|

Exports of services (current USD) (millions) |

250.36 |

- |

922.34 |

|

|

|

Intra-regional exports of goods (current USD) (millions) |

7.36 |

- |

15.72 |

|

|

|

International tourism receipts (current USD) (millions) |

112.02 |

182.72 |

430.07 |

|

|

|

International tourism receipts per arrival (current USD) |

538.27 |

1 205.39 |

769.93 |

|

|

|

Agriculture, livestock and forestry, value-added (current USD) (millions) |

30.79 |

32.85 |

48.18 |

|

|

|

Fishing value-added (current USD) (millions) |

7.85 |

8.37 |

12.82 |

|

|

|

Public-sector debt to GDP (%) |

66.32 |

65.67 |

47.11 |

|

|

|

Individuals using the Internet (% of population) |

67.40 |

- |

96.21 |

|

|

|

Agriculture, forestry, and fishing, value-added per worker (constant 2015 USD) |

7 765.20*† |

- |

14 793.69 |

|

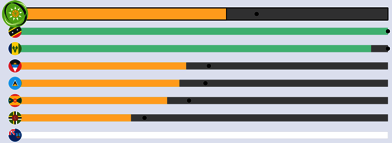

Note: The top bars represent the OECS average and each of the following bars represents one OECS country as indicated by countries’ flags. Black point in graph denotes value five years previous to the starting point. White bar indicates that there is no data for country. * denotes 2019, ** denotes 2016, † denotes value with less data: averages may not be representative.

Sources: ECCB (2022[6]), ECCB Statistics (database), https://www.eccb-centralbank.org/statistics/dashboard-datas/; World Bank (2022[2]), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators; UNSD (2022[7]), Statistics, https://unstats.un.org/UNSDWebsite/; National Social Security Boards of OECS countries; UN (2019[8]), UN Comtrade database, https://comtrade.un.org/data/.

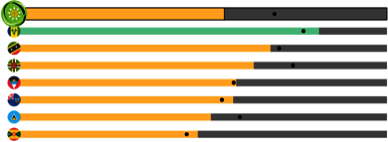

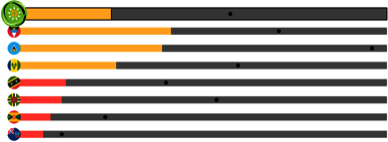

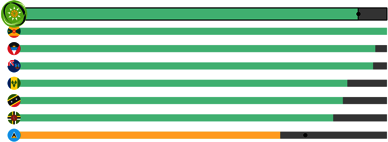

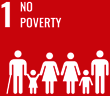

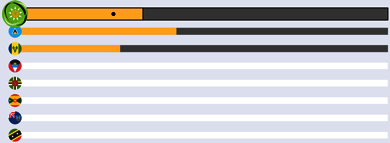

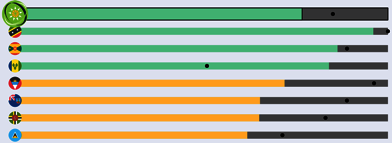

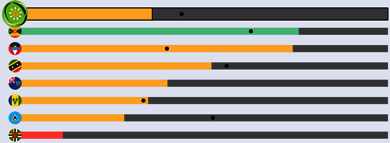

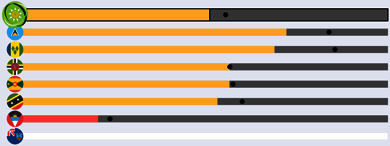

Annex Table 5.A.2. Scorecard indicators, Pillar 2: Promoting human and social well-being

|

SDG |

Scorecard indicator |

Starting point (2020) |

Current value (2021) |

Regional target 2030 |

Regional progress |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Labour market |

|||||

|

|

Formal employment-to-population ratio, ages 15+ (%) |

54.27 |

- |

68.94 |

|

|

|

Unemployment, total (% of total labour force) (national estimate) |

15.64† |

- |

10.13 |

|

|

|

Unemployment, female (% of female labour force) (national estimate) |

14.13† |

- |

10.45 |

|

|

|

Employment-to-population ratio, ages 15+, total (%) (national estimate) |

62.21† |

- |

67.36 |

|

|

|

Employment-to-population ratio, ages 15+, female (%) (national estimate) |

56.46† |

- |

64.52 |

|

|

Health |

|||||

|

|

Current health expenditure (% of GDP) |

4.89* |

- |

6.08 |

|

|

|

Out-of-pocket expenditure (% of current health expenditure) |

39.05* |

- |

28.20 |

|

|

|

Poverty headcount ratio at USD 5.50 a day (2011 purchasing power parity [PPP]) (% of population) |

25.95**† |

- |

8.9 |

|

|

|

Maternal mortality ratio (modeled estimate, per 100 000 live births) |

188.35 |

- |

54.46 |

|

|

|

Mortality rate, neonatal (per 1 000 live births) |

18.53 |

- |

5.72 |

|

|

|

Prevalence of obesity (Body mass index [BMI] > 30) (% of adults) |

22.40** |

- |

12.71 |

|

|

|

Prevalence of obesity in children/adolescents aged 10-19 years (% total) |

10.30 |

- |

7.77 |

|

|

|

Mortality from CVD, cancer, diabetes or CRD between exact ages 30 and 70 (%) |

19.8*† |

- |

8.86 |

|

|

|

Suicide mortality rate (age-adjusted per 100 000 population) |

2.2*† |

- |

1.14 |

|

|

Education |

|||||

|

|

Pre-primary enrolment (% gross) |

87.48 |

- |

113.68 |

|

|

|

Trained teachers in primary education (% of total teachers) |

67.64 |

- |

89.84 |

|

|

|

Trained teachers in secondary education (% of total teachers) |

52.72 |

- |

82.20 |

|

|

|

Government expenditure on education, total (% of GDP) |

4.56† |

- |

5.57 |

|

|

|

Tertiary enrolment (% gross) |

43.89† |

- |

69.83 |

|

|

Crime |

|||||

|

|

Intentional homicides (per 100 000 people) |

24.72 |

- |

9.10 |

|

|

|

Rates of police-recorded offenses (robbery) (per 100 000 population) |

95.19 |

- |

38.64 |

|

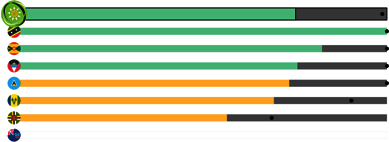

Note: Black point in graph denotes value five years prior to the starting point. White bar indicates that there is no data for country. * denotes 2019, ** denotes 2016, † denotes value with less data: averages may not be representative.

Sources: National Labour Force Surveys; National Social Security Boards of OECS countries; World Bank (2022[2]), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators; WHO (2022[9]), The Global Health Observatory - Indicators, https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators, PAHO (2022[10])ENLACE: Data Portal on Noncommunicable Diseases, Mental Health, and External Causes, Pan-American Health Organization, Washington, DC, https://www.paho.org/en/enlace.

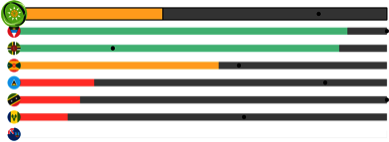

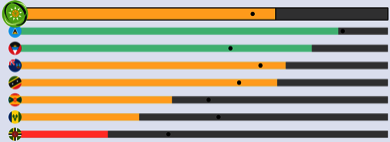

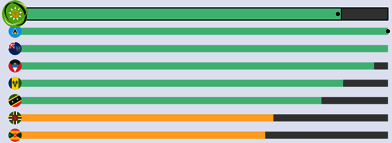

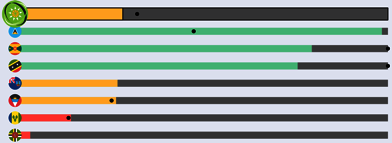

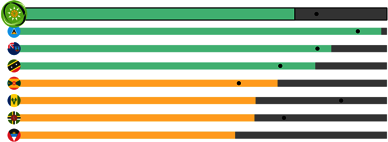

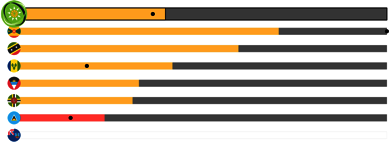

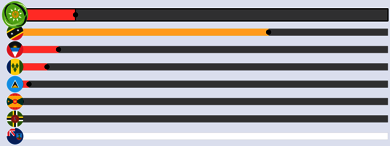

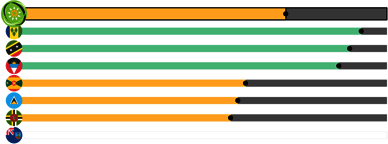

Annex Table 5.A.3. Scorecard indicators, Pillar 3: Sustainable use of natural endowments

|

SDG |

Scorecard indicator |

Starting point (2020) |

Current value (2021) |

Regional target 2030 |

Regional progress |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Marine protected area (% of territorial waters) |

0.81 |

0.81 |

4.98 |

|

|

|

Fish species, threatened |

30* |

- |

21.86 |

|

|

|

Renewable electricity output (% of total electricity output) |

6.87 |

- |

64.13 |

|

|

|

Forest area (% of land area) |

47.31 |

- |

63.98 |

|

|

|

Total greenhouse gas emissions (kilotonnes [kt] of carbon dioxide [CO2] equivalent) |

881.67 |

- |

460.28 |

|

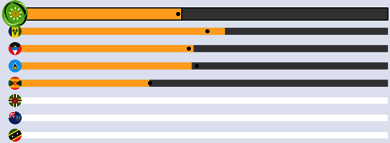

Note: Black point in graph denotes value five years prior to the starting point. White bar indicates that there is no data for country. * denotes 2019, ** denotes 2016, † denotes value with less data: averages may not be representative.

Source: World Bank (2022[2]), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators; IRENA (2022[11]), Data & Statistics, https://www.irena.org/statistics.