This chapter analyses and assesses the governance and institutional frameworks for digital government currently in place in Brazil. It reviews the current Digital Governance Strategy meant to set the country’s path towards the digitalisation of the public sector. It then focuses on the configuration and institutional set-up of the unit in charge of leading and co-ordinating digital government in Brazil. Finally, it discusses the existing co‑ordination mechanisms meant to ensure the necessary alignment across sectors and levels of government, so as to ensure the coherent and sustainable development of digital government in Brazil.

Digital Government Review of Brazil

Chapter 2. Strengthening the governance framework for digital government in Brazil

Abstract

Introduction

Economies and societies worldwide are going digital. People and businesses are changing not only how they interact, but how they access services and consume information, forcing governments to rethink and change the ways in which they serve their constituencies.

Governments today must demonstrate that they are up to the digital transformation underway. They need to prioritise mobilising digital technologies to link strategic goals (e.g. efficiency, inclusiveness, openness, sustainability) across different sectors and levels of their administrations, and to ensure policy coherence and long-term sustainability. Institutional set-ups need to be reconsidered and adjusted to support a whole-of‑government transformation able to better deliver results, responding to citizen’s increasing expectations (OECD, forthcoming[1]). Improved governance frameworks, based on clear mandates and political support, are required for a coherent and strategic digital government to succeed. The design, development, implementation and monitoring of policies supporting digital transformation require sound co-ordination among the ecosystem of stakeholders to deliver the expected policy results.

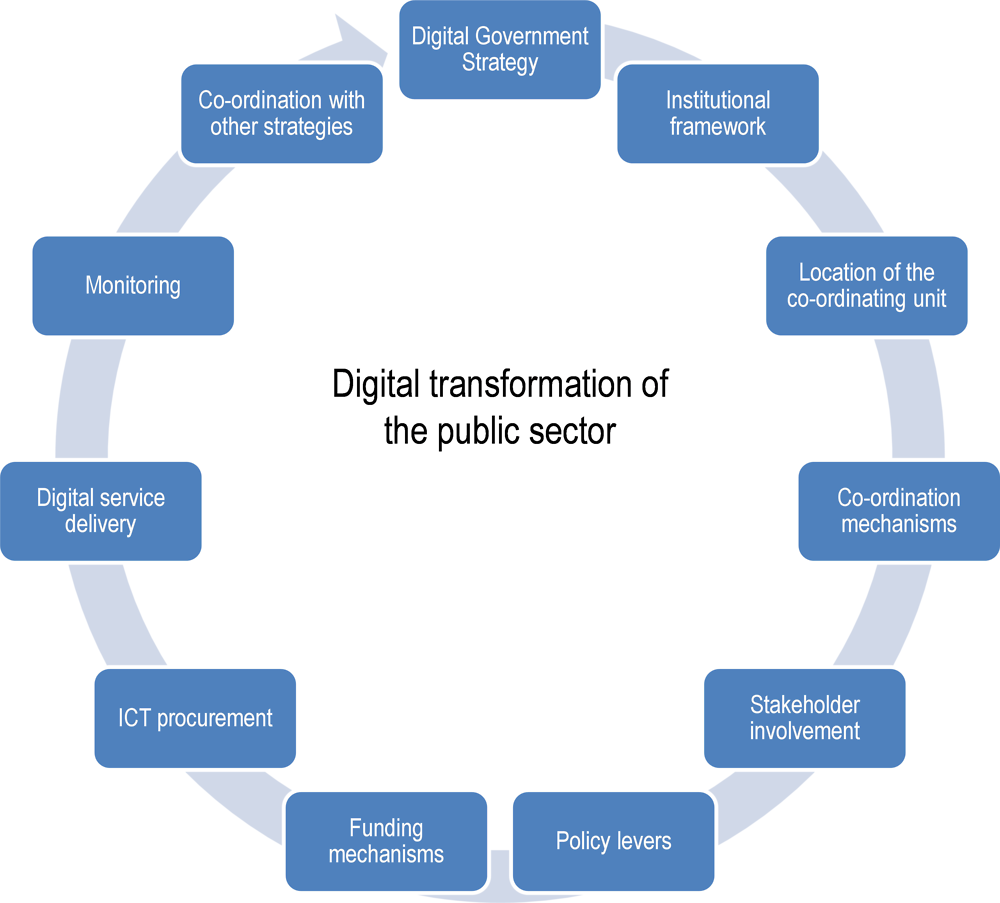

Considering that there is no one-size-fits-all approach applicable to all contexts, the OECD Recommendation on Digital Government Strategies (OECD, 2014[2]) highlights several dimensions that can contribute to a sound governance ecosystem. Some of the variables that contribute to the analytical framework underlying this Digital Government Review include collaboration and the mobilisation of stakeholders, co-ordination mechanisms in place, policy levers required to push strategic goals and synchronisation with other reforms of public sector agendas (see Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1. Governing the digital transformation of the public sector: Dimensions of analysis

Source: Author, based on OECD (2016[3]), Digital Government in Chile: Strengthening the Institutional and Governance Framework, OECD Digital Government Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264258013-en.

A comprehensive policy framework

Strategies to lead the digital change in the public sector

A digital government strategy is a critical policy mechanism used to define and align objectives, priorities and lines of action across sectors and levels of government. The strategy should embody the views of the ecosystem of stakeholders, so as to count on their collective willingness to support the digital change across the whole administration. The governance that supports the implementation of the strategy, i.e. the institutional set‑up, leadership, co-ordination mechanisms, policy levers and monitoring tools, are critical elements to consider when analysing experiences in other countries.

The openness and inclusiveness of the design, implementation and monitoring of the strategy are also relevant dimensions of analysis. Involving and collaborating with stakeholders from the public and private sectors, academia and civil society can help build consensus and develop joint ownership and shared responsibility for the successes or failures in the implementation of the strategy.

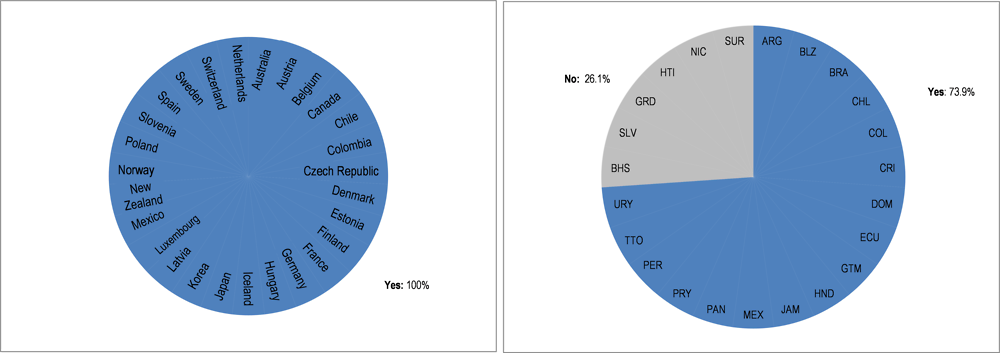

The existence of a digital government strategy is a common policy pattern in both OECD countries and the Latin America and the Caribbean region (LAC). By 2014, all OECD countries that completed the OECD Digital Government Performance Survey (OECD, 2014[4]) reported having a digital government strategy. Furthermore, results from the 2017 OECD Government at a Glance survey show that 17 out of 23 countries (73%) in the Latin America and the Caribbean region (LAC) (including Brazil) have developed a digital government strategy (Figure 2.2).

Figure 2.2. Existence of a national digital government strategy in OECD countries and the Latin America and the Caribbean region

Source: OECD (2014[4]), “Survey on Digital Government Performance”, https://qdd.oecd.org/subject.aspx?Subject=6C3F11AF-875E-4469-9C9E-AF93EE384796; OECD (2016[5]), Government at a Glance: Latin America and the Caribbean 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264265554-en.

Brazil started treading a more consistent path towards digital government in 2000 (Casa Civil, 2000[6]) when it approved an E-government Policy Proposal for the Federal Government (Proposta de Política de Governo Eletrônico para o Poder Executivo Federal), foreseeing cross-sector synergies on information technology (IT) infrastructures, rationalisation of information and communication technology (ICT) expenditures, promotion of online availability of services and implementation of digital inclusion measures (Grupo de Trabalho Novas Formas Eletrônicas de Interação, 2000[7]). The Executive Committee for Electronic Government (Comitê Executivo do Governo Eletrônico, CEGE) was also created in 2000. Chaired by the Civil House of the Presidency of the Republic, it brings together representatives from several ministries to formulate new policies, establish guidelines and co-ordinate actions for the implementation of e-government (Casa Civil, 2000[8]).

In 2004, new guidelines were defined to realign the E-government Policy with priorities such as the promotion of public participation and engagement of citizens through ICT, digital inclusion, open source software, knowledge management and integrated governance. In 2005, the Interoperability Standards of E-government (Padrões de Interoperabilidade de Governo Eletrônico, e-PING) were approved, reflecting the Brazilian government’s commitment to improving the connectivity between the information systems of the different sectors of government (Secretário de Logística e Tecnologia da Informacão, 2005[9]).

In 2008, the government of Brazil approved the first version of the General Strategy for ICT (Estratégia Geral de TIC), focused on setting goals for the improved management of public ICT resources in 2009. From 2010 to 2015, the General Strategy was consecutively updated, setting new goals for periods of one, two or three years around topics such as ICT management, better human resources, improved ICT procurement, adoption of standards, promotion of information security, better governance of ICT in the public sector and the alignment of the IT development plan of each public sector organisation (Ministério do Planejamento, Desenvolvimento e Gestão, 2018[10]).

The consecutive versions of the General Strategy for ICT led the way to several exemplary projects. For instance, in 2008 the public sector prioritised digital service delivery with the approval of the Web Standards on E-government (e-PWG), including clear recommendations on usability, online communication and the information architecture of public websites. In 2012, the Brazilian Open Data Portal was launched, reflecting the government’s efforts to promote the access to, and reuse of, public sector data for the purposes of transparency and economic value creation. In 2013, the launch of the Digital Cities Programme underlined the country’s efforts to promote digital government, a digital society and a digital economy at regional and local levels. In 2014, with the http://Participa.br portal, a website dedicated to online public consultations, the federal government demonstrated its commitment to mobilising digital technologies for improved public sector collaboration with citizens.

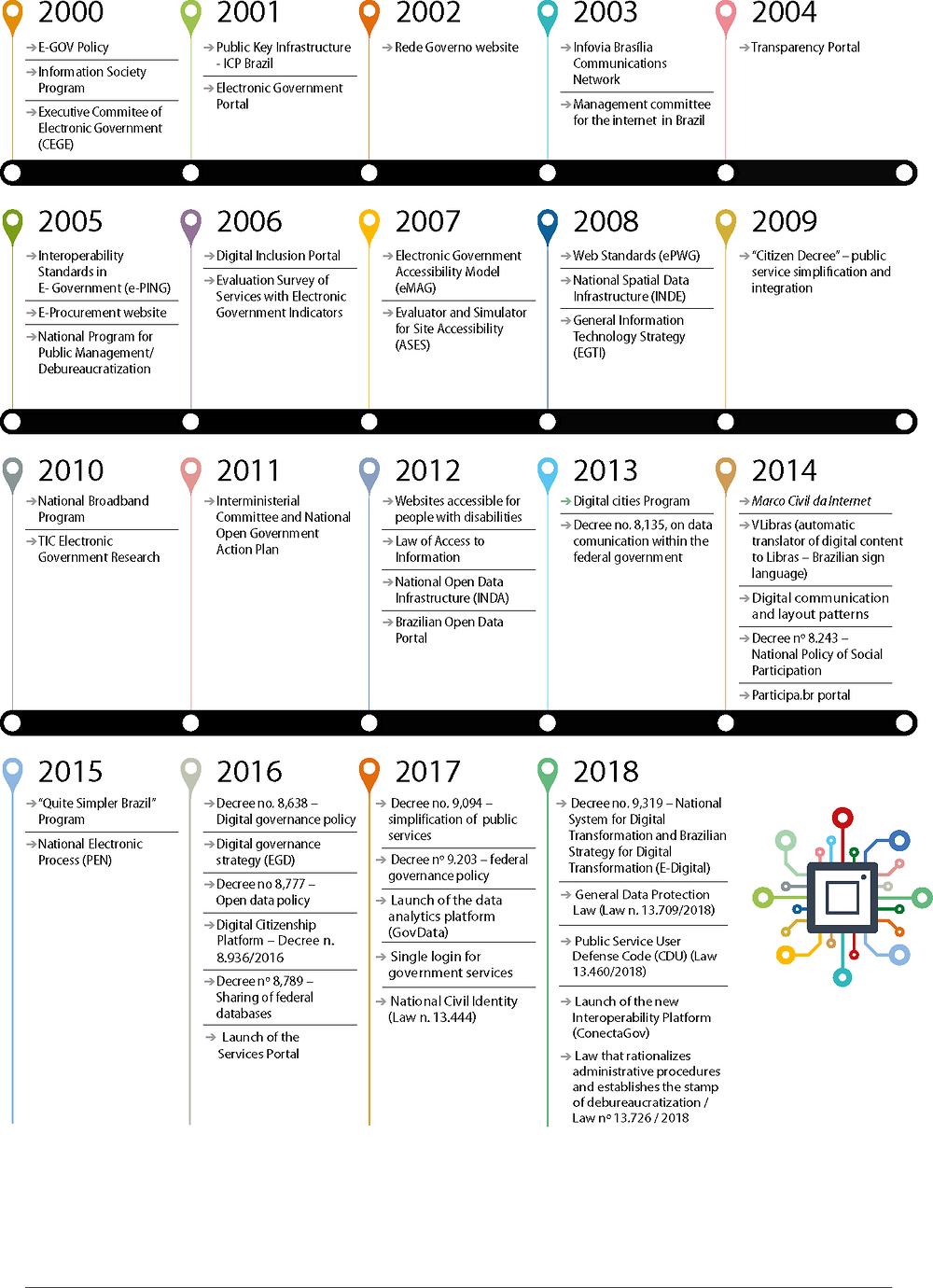

The Brazilian programmes on e-government and digital government (see Figure 2.3) reflect the country’s path, its main priorities and goals in different periods, and most of all, it shows Brazil’s progressive policy consolidation and growing maturity in addressing key issues associated with the digitalisation of the public sector. Figure 2.4 illustrates the main strategies currently underway that frame the policy action for the development of digital government in Brazil.

Figure 2.3. Brazil’s evolution towards e-government and digital government

Source: Adapted from Ministério do Planejamento, Desenvolvimento e Gestão (2018[11]), “Estratégia de Governança Digital (EGD) — Versão Revisitada”, https://www.governodigital.gov.br/EGD.

Figure 2.4. The programmatic context for digital government in Brazil

Source: Author.

Brazil’s Digital Governance Strategy (2016-19)

Brazil’s current Digital Governance Strategy (Estratégia de Governança Digital, EGD) was approved in 2016 (Portaria no. 68, of 7 March, following Decree no. 8,638, of 15 January) and is the result of a wide consultation and engagement process across the public sector. Covering the timeframe 2016-19, the goal of the strategy is to be more than an ICT strategy for the public sector. In line with the OECD Recommendation on Digital Government Strategies (OECD, 2014[2]):

“The purpose of EGD is to guide and integrate transformation initiatives of agencies and entities of the Federal Executive Branch, contributing to increasing the effectiveness of benefits generation for Brazilian society through the expansion of access to government information, improvement of digital public services and increased social participation.” (Ministério do Planejamento, Desenvolvimento e Gestão, 2018[11])

A first version was in place for two years to steer policy actions on digital government (Ministério do Planejamento, Orçamento e Gestão, 2016[12]). A revised version of the Digital Governance Strategy was presented in May 2018; its main objective is to simplify the strategy and reinforce the focus on the digital transformation of the public sector throughout 2019. The new version considers:

the principles, directives, guidelines and governance structures defined in Decree no. 9,203 of 22 November 2017 that provides general rules for governance in the public federal administration (Casa Civil, 2018[13])

the establishment of the Efficient Brazil Programme in March 2017

the launch of the Brazilian Digital Transformation Strategy, publicly presented in March 2018

the key findings of the OECD Digital Government Review of Brazil shared in advance with the Brazilian government and publicly presented in May 2018 (Ministério do Planejamento, Desenvolvimento e Gestão, 2018[11]).

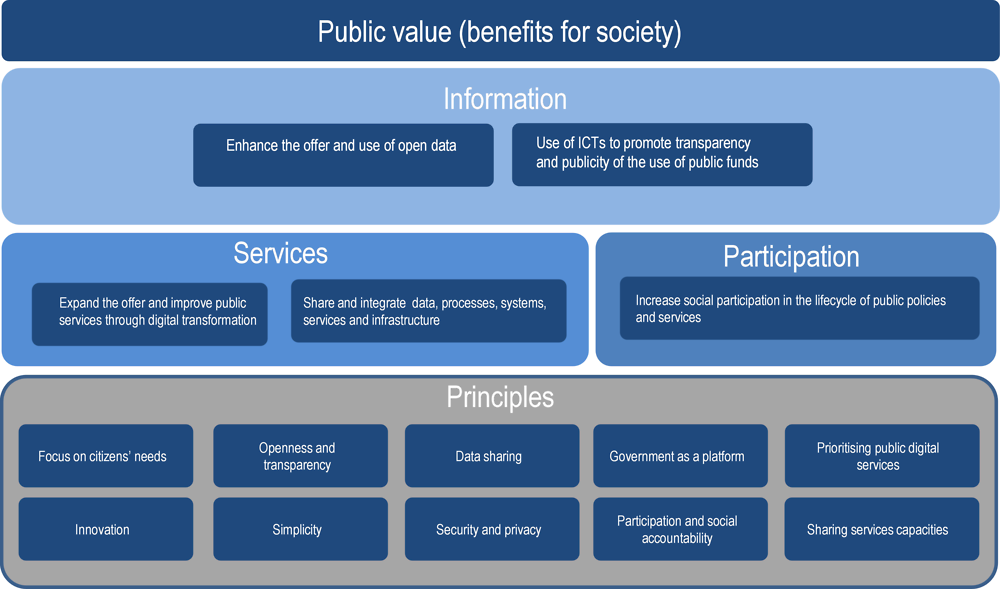

Grouped around three main pillars (access to information, service delivery and social participation), the revised Digital Governance Strategy defines five strategic objectives, namely: 1) promoting open government data availability; 2) promoting transparency through the use of ICT; 3) expanding and innovating the delivery of digital services; 4) sharing and integrating data, processes, systems, services and infrastructure; and 5) improving social participation in the lifecycle of public policies and services. The strategy assumes nine cross-cutting principles that guide the implementation of each strategic objective. Government as a platform, focus on citizen needs, simplicity and innovation are examples of these principles (see Figure 2.5).

Figure 2.5. Brazil’s revised Digital Governance Strategy (2018)

Source: Ministério do Planejamento, Desenvolvimento e Gestão (2018[11]), “Estratégia de Governança Digital (EGD) — Versão Revisitada”, https://www.governodigital.gov.br/EGD.

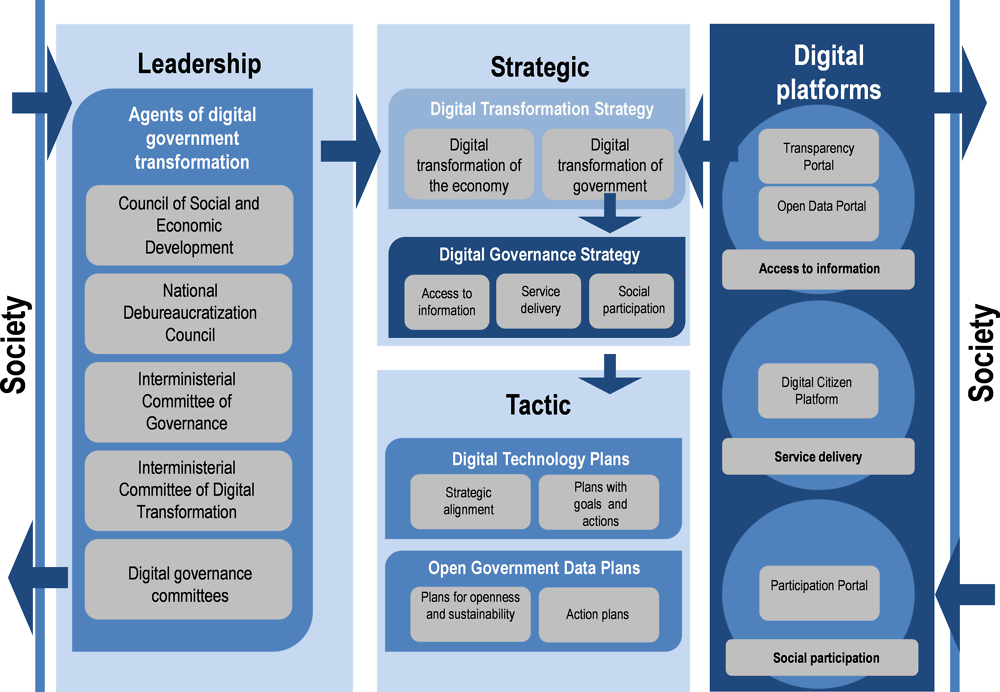

Each one of the three axes of the Digital Governance Strategy is more specifically connected with a government stakeholder and has a dominant digital platform:

The axis Access to Information has the General Comptroller of the Union (Controladoria Geral da União) as its main stakeholder. The federal open data portal (dados.gov.br) and the federal transparency portal (transparencia.gov.br) are the main platforms identified in this axis.

The axis Delivery of Services falls under the responsibility of the Ministry of Planning, Development and Management and is supported by the Digital Citizenship Platform (Plataforma de Cidadania Digital, PCD), including the services portal (https://www.servicos.gov.br) and the Kit for the Transformation Public Services.

The axis Social Participation has the Government Secretariat of the Presidency of the Republic as its main public stakeholder and the federal public participation and consultation portal (participa.br) as its central digital platform.

In order to facilitate the impact assessment and the transparency of the implementation of the Digital Governance Strategy, the five strategic objectives are attached to concrete goals to be achieved between 2016 and 2019, monitored and measured through specific indicators evaluated on a yearly basis. The level of detail dedicated to the monitoring mechanisms of the strategy shows the Brazilian government’s commitment to transparency and shared accountability by providing support for horizontality and cross-cutting implementation. This joint and shared commitment is critical to the long-term sustainability of the digital government strategy and its results.

The Brazilian Digital Transformation Strategy

The Brazilian Digital Transformation Strategy (Estratégia Brasileira para a Transformação Digital, “E-Digital”) is another relevant policy instrument that demonstrates the willingness of the federal government to benefit from digital change in order to promote economic and social development in the country (Grupo de Trabalho Interministerial, 2017[14]). Led by the Ministry of Science, Technology, Communications and Innovations and officially presented in March 2018, the strategy results from the work of several inter-ministerial working groups and sub-groups dedicated to specific topics and focused on sharing knowledge and the development of synergies among public initiatives targeting digitalisation. Representatives of the private sector and civil society were also consulted through a digital public consultation process conducted during August 2017.

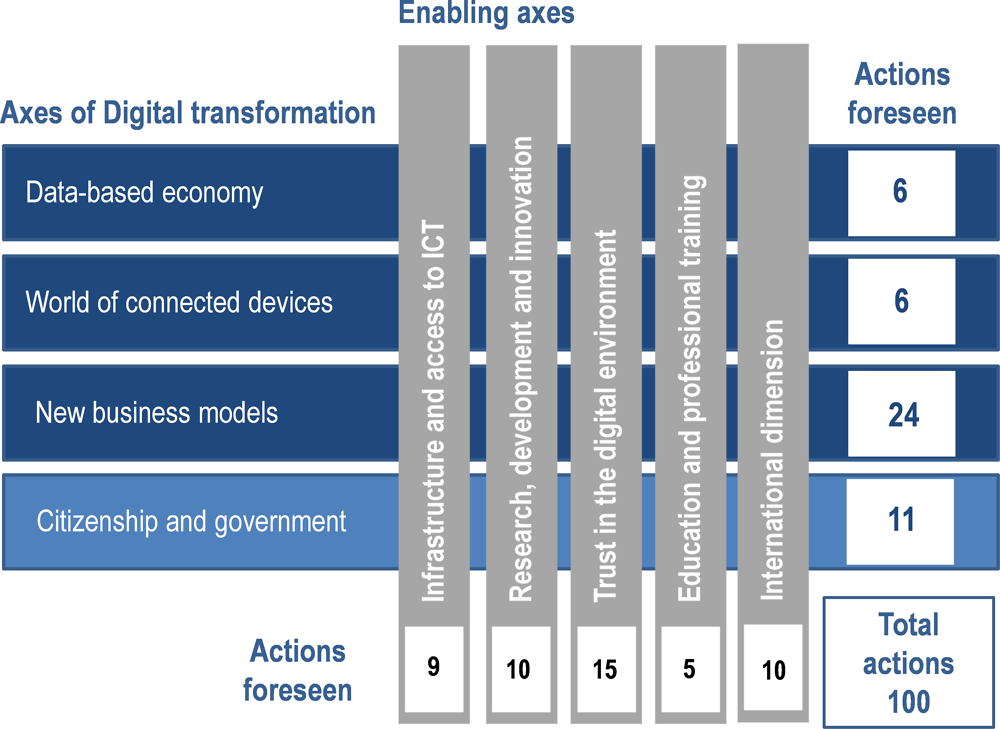

The strategy defines the following axes of intervention: infrastructure and access to ICT; research, development and innovation; trust in the digital environment; education and professional training; international dimension; data-based economy; world of connected devices; citizenship and government (see Figure 2.6).

The axis “citizenship and government” results from a joint effort between the Ministry of Planning, Development and Management and the Ministry of Science, Technology, Communications and Innovations, synthesising the main initiatives of the Digital Governance Strategy.

An important result of the E-Digital strategy was the creation of the National System for Digital Transformation and the Interministerial Committee of Digital Transformation (CITDigital) by Decree no. 9,319 of 21 March 2018. The decree establishes the E-Digital as a guide for the co-ordination of digital policies inside the federal government, and the CITDigital as the branch of the Casa Civil responsible for supervising the implementation of these policies. Initiatives such as the Digital Governance Strategy are debated and shared with the CITDigital (see the next section).

Figure 2.6. Main axes of the Brazilian Digital Transformation Strategy

Source: Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia, Inovações e Comunicações (2018[15]), “Estratégia Brasileira para a Transformacão Digital”, http://www.mctic.gov.br/mctic/export/sites/institucional/estrategiadigital.pdf.

Other relevant strategies for the transformation of government

The Efficient Brazil programme (Brasil Eficiente) promotes administrative simplification, modernising management and improving the delivery of services to businesses, citizens and civil society. Created in 2017 and co-ordinated by the National Debureaucratization Council, the Efficient Brazil programme aggregates measures of all federal public service agencies, including ministries and the presidency.

The federal government established relevant priorities within the framework of the Efficient Brazil programme in areas related to digital government, such as the integration and connection of public registers with the purpose of reducing fraud, and providing more efficient and convenient public services to citizens and businesses. For instance, Decree no. 9,094 of 17 July 2017 states that public entities from the federal government should not request documents or information from citizens that are already in federal public administration databases (the “once-only” principle). With this in mind, the Simplify initiative (Simplifique!) was implemented, which entails citizens filling out an online form to request a service simplification (Casa Civil, 2017[16]).

Some of Efficient Brazil’s measures are linked to the Digital Governance Strategy. One of the responsibilities of the Debureaucratization Council is to recommend to the Ministry of Planning, Development and Management the “adoption of priorities and targets in the updating and elaboration of future versions of the Digital Governance Strategy” (Casa Civil, 2017[17]). This demonstrates the Brazilian federal government’s commitment to ensuring proper co-ordination between the digital governance strategic objectives and Efficient Brazil, which reflects the awareness of the need to link and create synergies between administrative simplification and digital government.

The Brazilian Action Plan for Open Government can also be considered a strategic institutional instrument, conceived to promote the use of digital technologies to improve communication and develop collaborative approaches between the government and civil society. Based on the co-ordination of the Interministerial Committee for Open Government since 2011, Brazil is currently elaborating the fourth edition of its Open Government Action Plan, developing it in a collaborative way through workshops (oficinas de cocriação) involving public officers and civil society representatives (Controladoria-Geral da União, 2018[18]).

Furthermore, the Cyber-defence Strategy, published in 2015, provides guidelines for the strategic planning of information and communications security, and cybersecurity. These guidelines apply to agencies and entities at the federal level. Brazil also has an Information Security Policy (Política de Segurança da Informação) that regulates and establishes institutional mechanisms to guarantee the security of data and information managed by the federal public administration (Casa Civil, 2000[19]). The Department of Communications and Information Security of the Institutional Security Cabinet of the Presidency of the Republic is the federal institution responsible for the Information Security Policy.

Perceptions of the digital government policy framework across government institutions

Beyond the existence and configuration of a national/federal digital government strategy, the perceptions of government institutions are critical to understanding if and how the strategy is being used as a policy lever to effectively guide its implementation across the administration. A strategy can only be considered relevant if the ecosystem of stakeholders acknowledges its existence, importance and shares ownership and responsibility for its implementation.

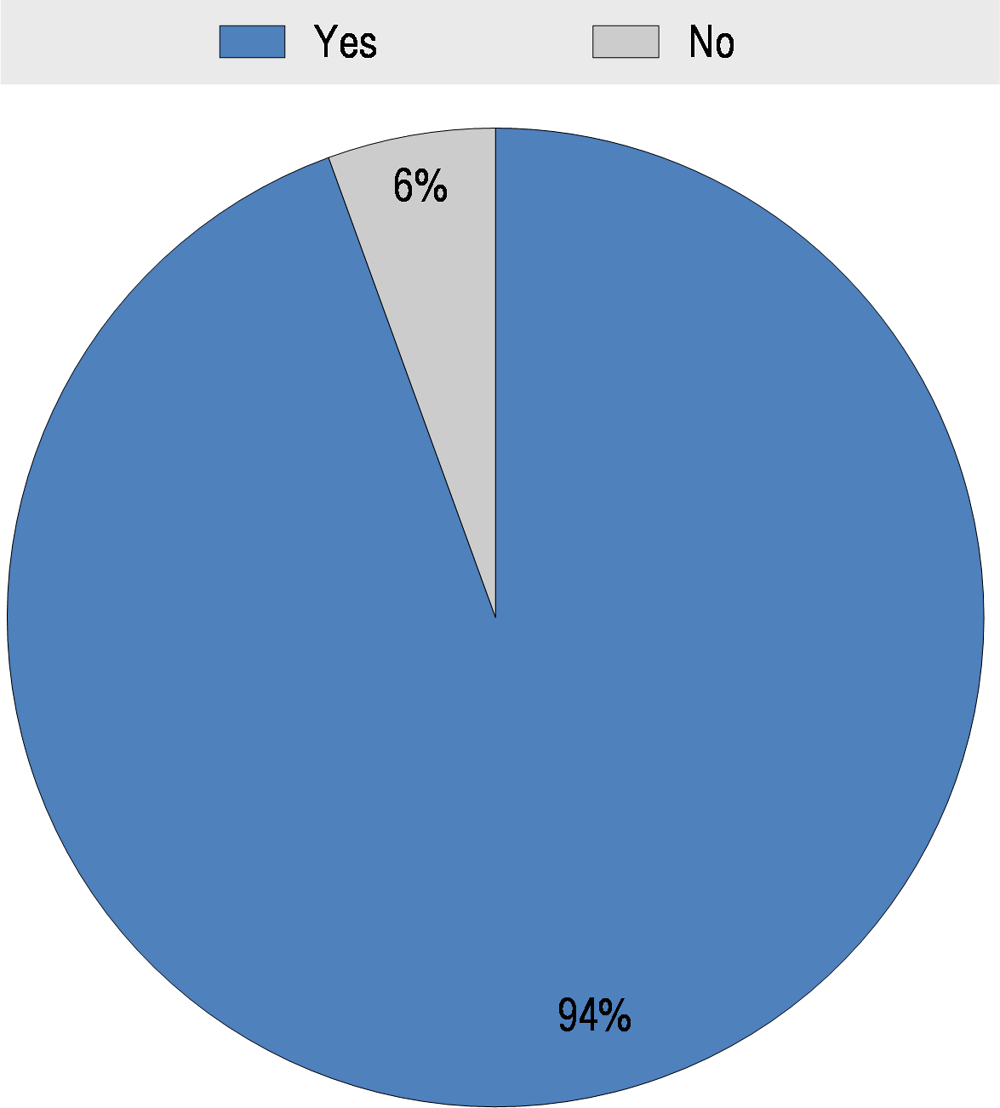

In line with the perceptions recorded during the OECD peer review mission to Brasilia in July 2017, 94% of the Brazilian public sector organisations that answered the Digital Government Survey of Brazil recognised the existence of the Digital Governance Strategy (see Figure 2.7). This high percentage of recognition reflects the good work of the Brazilian government in communicating about the strategy and keeping the stakeholders involved in its implementation.

Figure 2.7. Recognition of the existence of a digital government strategy among Brazilian public sector organisations

Note: The figure shows the percentage of participating public sector organisations that responded yes or no to the question, “Do you know if there is a national/federal digital government strategy in place developed and implemented by the federal government?”

Source: OECD (2018[20]), “Digital Government Survey of Brazil”, Public sector organisations version, unpublished.

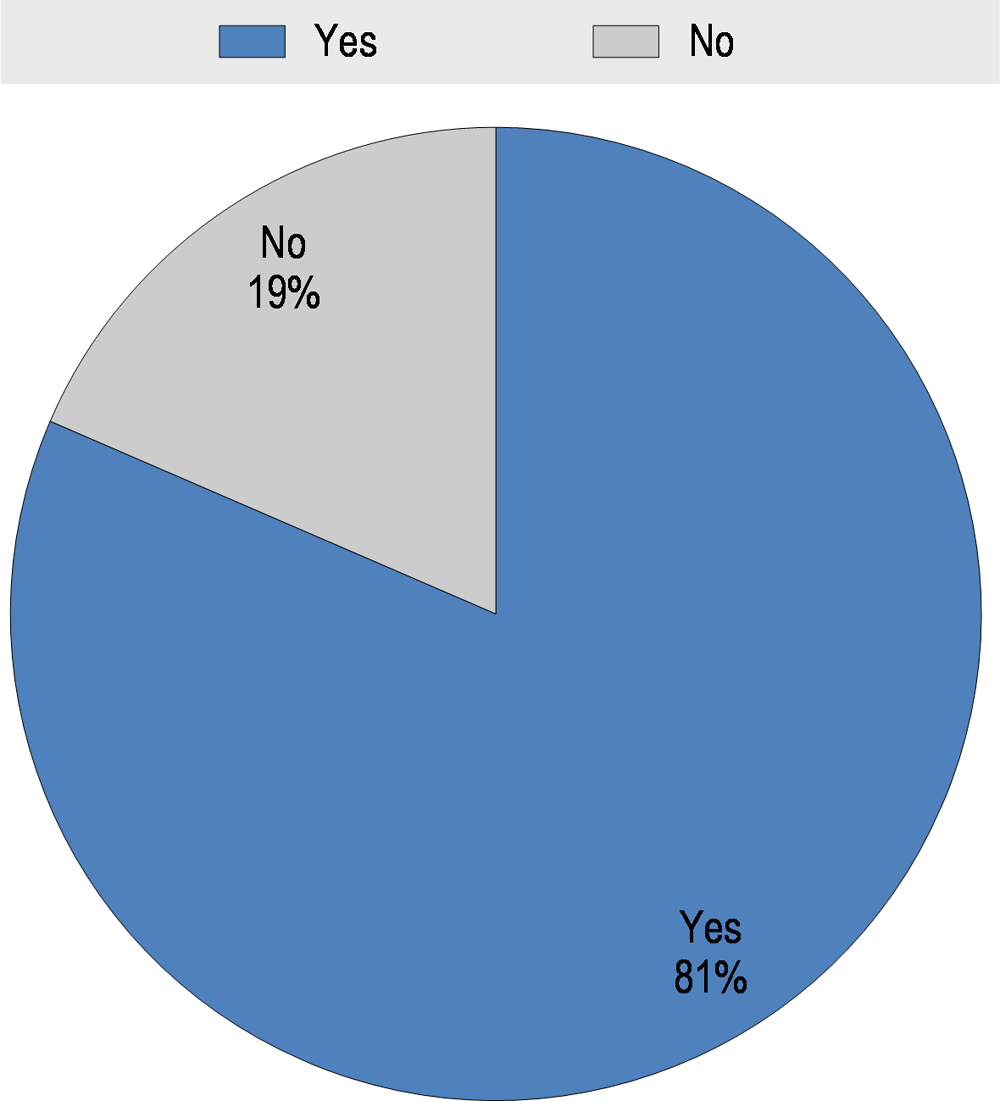

Furthermore, 81% of the public sector organisations that answered the survey confirmed that the strategy was developed as a result of a co-ordinated process across sectors of government (see Figure 2.8). The original version of the strategy (2016-17) benefited from preparatory meetings involving public sector officials, a seminar with the participation of more than 250 people and three thematic workshops that allowed for the integration of more than 1 000 suggestions (Ministério do Planejamento, Orçamento e Gestão, 2016[12]). The updated version of the strategy followed the same pattern of collaborative development.

The capacity to involve stakeholders in the development of a digital government strategy is critical to ensuring its recognition among the ecosystem of stakeholders, as well as its strong alignment with the various expectations and different needs existing within the public administration. This engagement culture is also fundamental to strengthening perceptions about the importance of the strategy for the activities of public sector organisations.

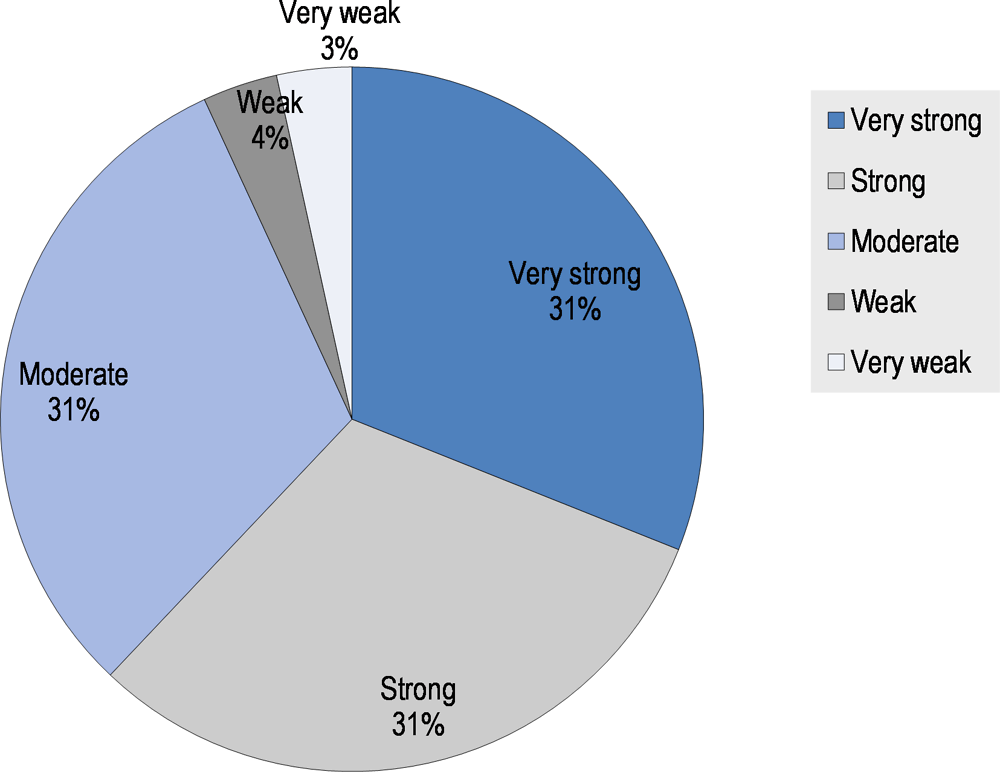

According to the results from the Digital Government Survey of Brazil (OECD, 2018[20]), 62% of public sector organisations consider the relevance of the Digital Governance Strategy (EGD) as “very strong” or “strong”, 31% consider it “moderate” and 7% indicated that it is “weak or “very weak” (see Figure 2.9). These positive results underscore the fact that the EGD is considered a relevant policy instrument, and demonstrates its influence across different sectors of government, a crucial requirement for the development of a co-ordinated digital government.

Figure 2.8. Co-ordinated development of the digital government strategy/policy with Brazilian public sector organisations

Note: The figure shows the percentage of participating public sector organisations that responded yes or no to the question, “Was the current federal strategy/policy developed as a co-ordinated process between public sector institutions, e.g. ministries?”

Source: OECD (2018[20]), “Digital Government Survey of Brazil”, Public sector organisations version, unpublished.

Figure 2.9. Relevance of the digital government strategy for Brazilian public sector organisations

Source: OECD (2018[20]), “Digital Government Survey of Brazil”, Public sector organisations version, unpublished.

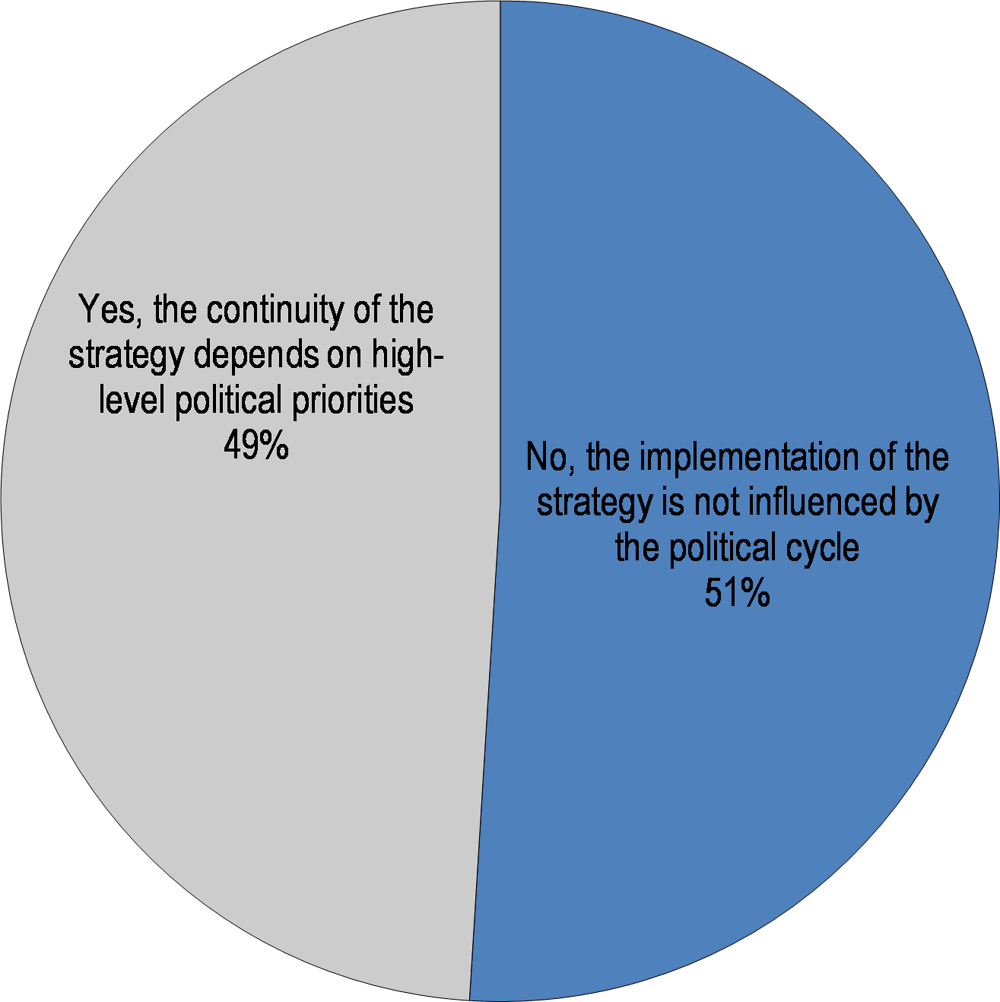

The influence of political cycles on the development of a digital government strategy is also considered a relevant dimension of analysis as most senior officials in OECD countries generally recognise the negative impacts of changes in government for the continuity of projects and initiatives. Political elections often result in a sudden change of political priorities, which may negatively affect efforts underway and can even lead to the abrupt abandonment of projects. Nevertheless, on the positive side, changes in government can also determine the acceptance and creation of updated priorities and policy topics, necessary to complement the work developed by previous administrations.

The stakeholders that answered the Digital Government Survey of Brazil were highly divided regarding the influence of political cycles on the Digital Governance Strategy (see Figure 2.10). This reflects a hybrid context, where changes in the administration affect the efforts underway in some sectors of the government, but in others do not seem to have negative impacts on the projects and initiatives underway. This can also be explained by the fact that, although some alignment can be observed between the launch/update of the digital government strategy and some changes in the administration, there is also considerable government effort to ensure some continuity in the policy goals.1

Figure 2.10. The influence of policy cycles on the digital government strategy according to Brazilian public sector organisations

Source: OECD (2018[20]), “Digital Government Survey of Brazil”, Public sector organisations version, unpublished.

Streamlining policy guidance

Digital government has considerable policy relevance in Brazil, demonstrated not only by the specific strategy in place dedicated to this policy area – the Digital Governance Strategy (EGD) – but observable also by the fact that several other policy instruments highlight and refer to digital government goals, initiatives and projects (e.g. the Strategy for the Digital Transformation, Efficient Brazil). The fact that these policy instruments are well disseminated and recognised by stakeholders reflects the communication and collaboration efforts in place across different sectors of government.

Nevertheless, during the OECD peer review mission in Brasilia on July 2018, several stakeholders showed some difficulty in accurately identifying the central digital government policy strategy in place. Some pointed to the EGD, but others referred to the Strategy for the Digital Transformation or the Efficient Brazil programme.

Given this, the Brazilian government should consider improving efforts to better communicate the different scopes of the three strategies/programmes underway, the role each plays, and how they connect and co-ordinate with each other. The clarification of the scope of each of the strategies can help support improved alignment for the ecosystem of stakeholders, which will be required for sound and sustainable policy implementation.

Leadership and institutional set-ups

Governance for the digital transformation of the public sector

A clear definition of roles and responsibilities is a critical institutional requirement for sound, digital government governance. The OECD (2014[2]) Recommendation on Digital Government Strategies underscores the importance of “identifying clear responsibilities to ensure overall co-ordination of the implementation of the digital government strategy.” A clear governance framework has strategical value to steer actions to ensure synergies, guarantee coherence and avoid overlaps on government efforts to digitally transform the public sector.

Considering its cross-cutting nature and the horizontal involvement required for successful implementation, a government’s priorities to digitally transform its public sector require the existence of an institution with a clear mandate to lead and co-ordinate policy design, implementation, delivery and monitoring across different sectors and levels of government. This institution, which should rely on necessary political support thanks to its organisational set-up, is required to ensure leadership, promote co-operation and enable a shift from an agency-driven mindset centred on government priorities and ways of working to a systems-thinking culture able to develop citizen-driven approaches.

Institutional leadership of digital government

The Secretariat of Information and Communication Technologies (Secretaria de Tecnologia da Informação e Comunicação, SETIC) of the Ministry of Planning, Development and Management leads the co-ordination efforts to develop digital government in Brazil. Its main responsibility is to define “public policies related to the use, management and governance of technology in the federal public administration.”2 (Ministério do Planejamento, Desenvolvimento e Gestão, 2018[21]).

In line with the above, SETIC is the public body of the Brazilian federal administration responsible for leading the Digital Governance Strategy:3

“The Secretariat of Information Technology of the Ministry of Planning, Budget and Management is responsible for coordinating the formulation, monitoring, evaluation and review of the Digital Governance Strategy, with the participation of the other units that act as the central body of the structural systems of the Federal Executive Branch.” (Ministério do Planejamento, Orçamento e Gestão, 2016[22])

In addition to the Digital Governance Strategy, SETIC is responsible for several projects and initiatives in place that structure the Brazilian digital government policy framework, namely the:

1. Digital Citizenship Platform (Plataforma de Cidadania Digital), committed to promoting the Portal of Services of the Federal Government (servicos.gov.br) as the main and integrated channel for public digital service delivery.

2. Platform of Data Analysis of the Federal Government (GovData) (Plataforma de Análise de Dados do Governo Federal) that allows access to different databases within the public sector for data analytics and data-driven policy making and analysis.

3. Platform Conecta.GOV, which provides a catalogue of the federal government application programming interfaces (APIs) in order to promote data sharing, integration and interoperability for improved government processes and services (see Chapter 4).

4. System of Administration of Information Technologies Resources (SISP), the structure within the federal government responsible for the planning, co‑ordination, management and control of ICT resources across sectors and levels of government (see the section above).

Brazil’s federal government model comprises a federal district, 26 states, and 5,570 municipalities. Local governments benefit from large, political, administrative and financial autonomy, therefore leading to multi-level governance challenges in terms of cross-level co-ordination of digital government policies. Yet, SETIC’s policy definition and co-ordination role were clearly acknowledged by all stakeholders met during the OECD peer review mission to Brasilia. The importance attributed to the digital transformation of the public sector and the willingness found across the ecosystem of stakeholders to support public sector change through digital technologies are important pillars that can sustain effective and action-oriented digital government policies going forward.

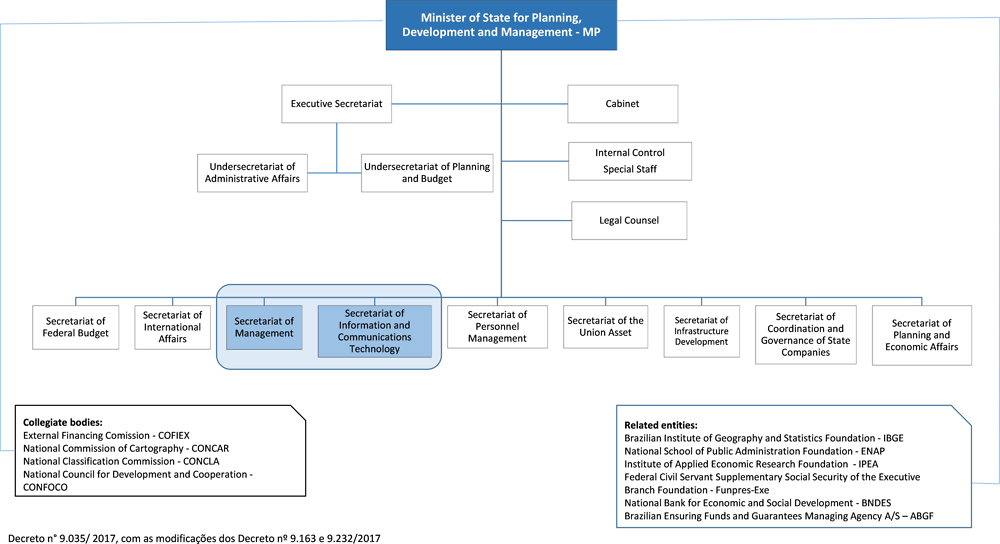

The Secretariat of Management (Secretaria de Gestão, SEGES), a body within the Ministry of Planning, Development and Management (see Figure 2.11), also has significant relevance in the federal steering of the digital government policy in Brazil. SEGES is the unit that:

“…proposes, coordinates and supports the implementation of strategic plans, programs, projects and actions for innovation, modernization and improvement of public management, promotes knowledge management and cooperation in public management, coordinates, manages and provides technical support to special projects of modernization of the public management related to themes and strategic areas of government.” (Ministério do Planejamento, Desenvolvimento e Gestão, 2018[23])

Although SEGES has a mandate significantly different from that of SETIC, it has significant responsibilities in the development of digital services. Through its Department of Modernization of Public Management, SEGES pursues the simplification and full digitisation of public services. These efforts are implemented in co-ordination with SETIC, demonstrating the joint complementarity of these two secretariats of the Ministry of Planning, Development and Management.

In addition to the two above-mentioned bodies within the Ministry of Planning, Development and Management, the Civil House of the President of the Republic of Brazil also has a central role in sponsoring the development of digital government in the federal government, at a political level. The Sub-branch of Analysis and Monitoring of Government Policies (Subchefia de Análise e Acompanhamento de Política Governamentais, SAG) is responsible for supervising strategic federal government cross-sectoral policies in the areas of public management. The Sub-branch of Articulation and Monitoring (Subchefia de Articulação e Monitoramento) is responsible for overseeing and co-ordinating government activities, namely providing high-level sponsorship for the country’s digital transformation. To this end, there is strong co-ordination with the Ministry of Planning, Development and Management in order to support the implementation of digital government policies across the sectors of government.

Figure 2.11. Organigram of the Brazilian Ministry of Planning, Development and Management

Source: Ministério do Planejamento, Desenvolvimento e Gestão (2018[24]), “Estrutura Organizacional — Ministério do Planejamento, Desenvolvimento e Gestão”, http://www.planejamento.gov.br/acesso-a-informacao/institucional/estrutura-organizacional.

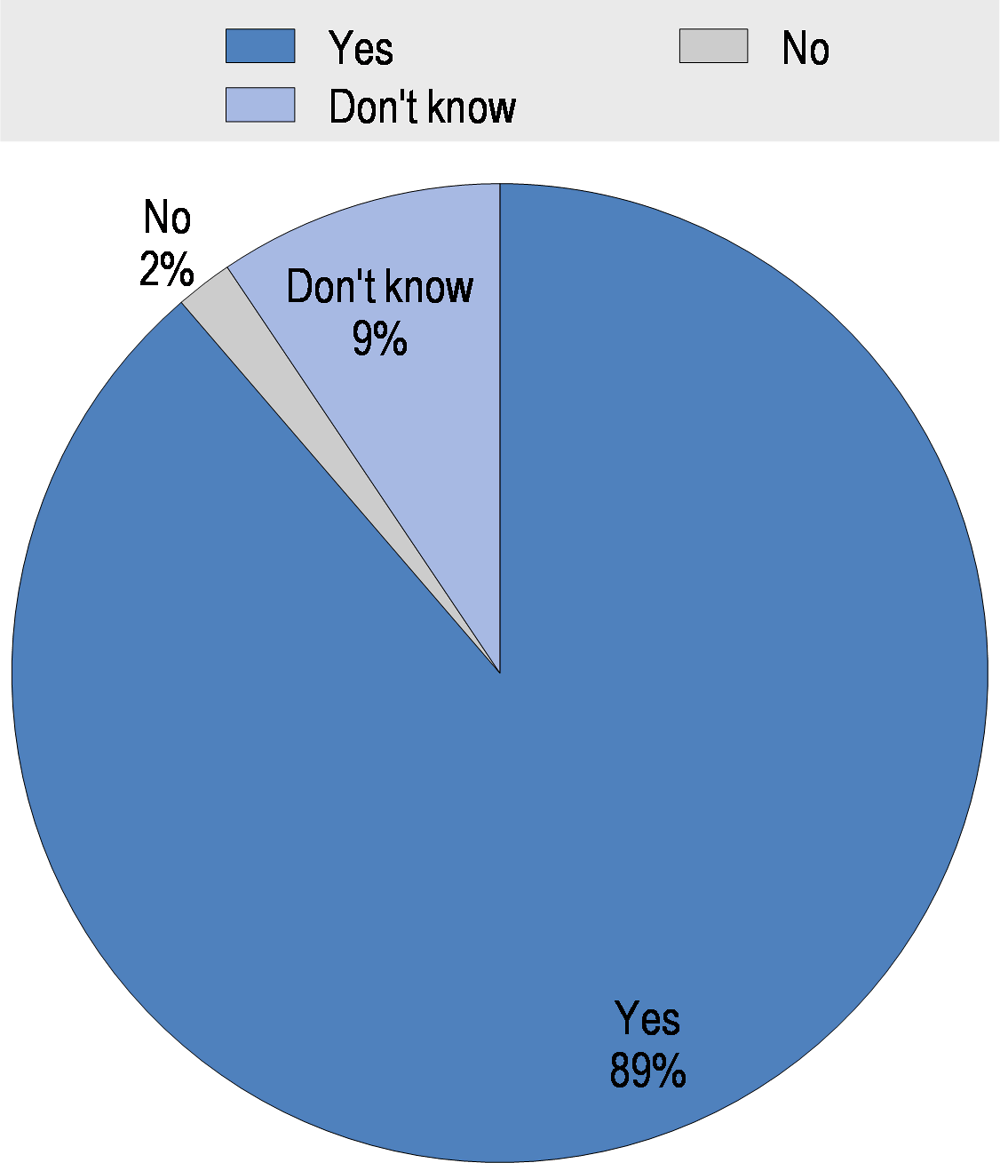

Perceptions regarding the co-ordinating body responsible for Brazil’s digital government policy

Public stakeholders’ perceptions regarding the co-ordination of digital government are critical to understanding the context and institutional environment for the digital transformation of the public sector. Of the Brazilian public institutions that participated in the Digital Government Survey of Brazil, 89% responded positively when asked if there were a public sector organisation responsible for the co-ordination of the Digital Governance Strategy (EGD) and for leading the country’s digital government policy (see Figure 2.12). Respondents identified the Ministry of Planning, Development and Management, or more specifically the Secretariat of Information and Communication Technologies (SETIC), as the public sector organisation responsible for the digital government policy.

Figure 2.12. Recognition of the existence of a co-ordinating body responsible for Brazil’s digital government policy

Note: The figure shows the percentage of participating public sector organisations that responded yes or no to the question, “Is there a leading public sector institution at the federal government level responsible for designing and setting the federal digital strategy and leading and co-ordinating the decisions on the strategic use of IT in the federal government?”

Source: OECD (2018[20]), “Digital Government Survey of Brazil”, Public sector organisations version, unpublished.

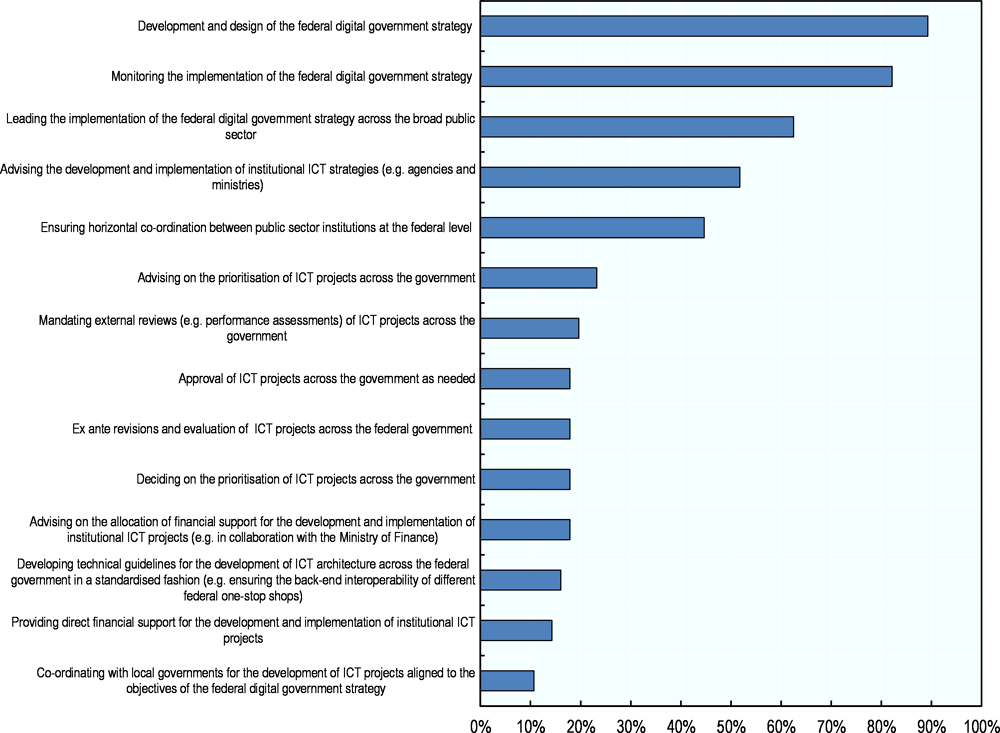

When inquired about the main responsibilities of the public sector organisation responsible for the digital government policy, the development (89%) and monitoring (82%) of the digital government strategy were the main functions attributed to SETIC and to the Ministry of Planning, Development and Management (see Figure 2.13). A not so large, but significant, percentage of the participating public institutions also attributed the responsibility of leading the implementation of the strategy (62%), advising the implementation of the institutions’ level strategies (52%) and ensuring the horizontal co‑ordination between public sector institutions at federal level (45%). The remaining possible responsibilities presented in the survey that would require a stronger political and institutional mandate – mandating external reviews, evaluation of ICT projects or advice on the allocation of financial support for the development of ICT projects – were very remotely attributed to the SETIC. Even the responsibility for the development of technical guidelines for the development of a common ICT architecture in the public sector was only recognised by a minority of institutions as a responsibility attributed to SETIC and the Ministry of Planning, Development and Management.

The public organisations that participated in the Digital Government Survey of Brazil clearly attribute the role of developing, leading and monitoring the implementation of the Digital Government Strategy to the co-ordinating body. Nevertheless, there is a clear understanding that SETIC and the Ministry of Planning, Development and Management do not have enforcement policy tools that can drive a strong and streamlined co‑ordination of digital government development in Brazil. In fact, this perception is aligned with SETIC’s own perspective regarding the limitations of its mandate and how it determines some lack of institutional co-ordination in the development of digital government in Brazil (OECD, 2018[25]).

Figure 2.13. Main responsibilities attributed to the co-ordinating body responsible for Brazil’s digital government policy

Source: OECD (2018[20]), “Digital Government Survey of Brazil”, Public sector organisations version, unpublished.

Improving governance for better co-ordination and more effective implementation

The institutional set-up for the governance of digital government in Brazil has significant potential. SETIC’s responsibilities for defining the policies to use digital technologies in the federal public administration are complemented by an interesting cross-cutting mandate assigned to SEGES for modernising the public sector. SEGES’ mandate has the fundamental political support of the Civil House (Casa Civil) of the Presidency of the Republic. The number of strategic cross-cutting projects, initiatives and lines of action promoted by the two secretariats of the Ministry of Planning, Development and Management, with the important support of the Casa Civil, also demonstrates the Brazilian government’s current willingness to drive the digital transformation of the public sector.

Nevertheless, there are some central challenges for better governance that should be considered. The existence of different public sector organisations with leading or co‑ordinating responsibilities can cloud a clear leadership for the implementation of common and cross-cutting policy goals. The launch of the updated version of the Digital Governance Strategy and the renewed leadership role attributed to SETIC can further contribute to streamlining governance.

Yet, one of the biggest challenges for improved governance of digital government in Brazil is the lack of institutional resources and capacities attributed to SETIC. In this sense, policy levers such as the responsibility to pre-evaluate ICT expenses, lead the ICT procurement strategy, fund or manage the funding of digital government projects across the administration, could have a determinant effect on SETIC’s capacity to effectively lead and co-ordinate the federal digital government policy (see Chapter 3 and Box 2.1).

Box 2.1. Examples of digital government leadership in OECD countries

Norway

The co-ordination of digital government policies and public sector reform in Norway is a responsibility of the Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation (KMD), namely the Department of ICT Policy and Public Sector Reform. The KMD exerts its digital government co-ordination role namely through a digitalisation memorandum that provides a set of strategic actions to be implemented by ministries during a 12-month period in line with the objectives of the national digital government policy.

Responding to KMD, the Agency for Public Management and eGovernment (Difi) is the Norwegian public sector agency responsible for the executive management and implementation of the digital government policies. Created in 2008 and with more than 250 staff members, the agency has the following areas of focus:

1. management development, organisation, management, innovation and skills development

2. digitisation of public services and work processes

3. development and management of common solutions

4. public procurement

5. preventive ICT security

6. universal design of ICT solutions.

The development of common guidelines and assuring the horizontal co-ordination are among the main responsibilities attributed to Difi.

United Kingdom

The Government Digital Service (GDS) was founded in December 2011. It is part of Cabinet Office, the United Kingdom’s centre of government, and works across the whole of the UK government to help departments meet user needs and transform end-to-end services.

GDS’ responsibilities are to:

1. provide best practice guidance and advice for consistent, coherent, high-quality services

2. set and enforce standards for digital services

3. build and support common platforms, services, components and tools

4. help government choose the right technology, favouring shorter, more flexible relationships with a wider variety of suppliers

5. lead the digital, data and technology function for government

6. support increased use of emerging technologies by the public sector.

GDS builds and maintains several cross-government platforms and tools, including GOV.UK, GOV.UK Verify, GOV.UK Pay, GOV.UK Notify, and the Digital Marketplace. It also administers a number of standards, including the Digital Service Standard, the Technology Code of Practice and Cabinet Office spend controls for digital and technology.

In 2013, less than two years after its launch, GDS had over 200 staff. Today GDS has more than 500 staff.

Source: OECD (2017[26]), Digital Government Review of Norway: Boosting the Digital Transformation of the Public Sector, OECD Digital Government Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264279742-en; Government Digital Service (2018[27]), “About us”, Gov.uk, https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/government-digital-service/about.

Brazil could also benefit from the institutionalisation of a role with a mandate to lead the digital transformation of the public sector (e.g. a government Chief Digital Transformation Officer [CDTO]) that should be able to count on the right political support. The institutionalisation of the new role should be considered as part of a broader institutional effort to provide clear and sound leadership for the digitalisation of the public sector. For instance, a real change in this policy area will depend on the capacity of this role to conciliate a high-level supported mandate with the ability to involve the ecosystem of digital government stakeholders. This new institutional role should have the capacity to mobilise and build consensus, namely among the chief information officers (CIOs) of all ministries. These consensuses, aligned with the proper policy levers (see Chapter 3) and key enablers (see Chapter 4), could bring significant positive changes to the dynamics of digital government development in Brazil.

Developing co-ordination and a culture of co-operation

Institutional co-ordination is one of the critical challenges countries face to ensuring the coherent and sustainable development of digital government. The digital transformation of the public sector requires a shift from an agency-driven to a systems-thinking mindset, where synergies across sectors and levels of government, the private sector and civil society are understood as critical for efficient, inclusive and mature digital government policies. Policy co-ordination mechanisms are required to ensure regular exchange of data and information and consensus on policy priorities that can enable co-ownership and co-responsibility for the implementation of a digital government strategy (OECD, 2016[3]).

Policy co-ordination mechanisms also favour better monitoring capacities, allowing policy makers to more easily have an overview of projects and initiatives being implemented across the administration. The regular exchange of knowledge and data on policy implementation and the co-operative environment sustained by regular meetings among stakeholders can also promote improved accountability on policy action, allowing governments to put transparency mechanisms in place to improve citizen trust.

In Brazil, two important policy instruments contribute across the federal government to improved co-ordination among public stakeholders. The Digital Governance Strategy (EGD) results from a wide consultation and engagement process across the public sector and provides guidance for coherent, cross-cutting digitalisation efforts in the public sector. Formulated between 2017 and 2018, the Brazilian Strategy for Digital Transformation ‑ E-Digital – gathered different public organisms and civil society stakeholders with the purpose of identifying current challenges and opportunities for digital transformation in the government and the economy at large.

The System for the Administration of Information Technologies Resources (Sistema de Administração dos Recursos de Tecnologia da Informação, SISP) is the main institutional co-ordination mechanism in place promoting the necessary alignment among the federal-level public sector organisations concerning digital government policies and practices. The SISP is co-ordinated by SETIC and brings together over 200 representatives of public bodies from the federal government. The system has a transversal convening role, but limited enforcing capacities. The SISP’s objectives are to:

1. promote the “integration and co-ordination among government programs, projects and activities, envisaging the definition of policies, directives and norms for the management of information technologies resources”

2. encourage the “development, standardisation, integration, interoperability, normalisation of services of production and dissemination of information”

3. define the strategic policy for the management of ICT of the federal government (Casa Civil, 2011[28]).

The SISP also contributes to knowledge exchange, peer-to-peer learning and promoting innovation among its members. Through a virtual community, SISP members are invited to interact and share knowledge. SISP expert groups also bring together some of its members to discuss and agree common actions on: 1) strategic human resource management; 2) IT procurement; 3) information and communication security; and 4) electronic services and accessibility.

The Economic and Social Development Council (Conselho de Desenvolvimento Econômico e Social, known as Conselhão, CDES), created in 2003, is composed of civil society representatives that directly advise the President of the Republic. The Council should:

“… advise the President of the Republic on the formulation of specific policies and guidelines for economic and social development, produce normative indications, political proposals and procedural agreements that aim at economic and social development; and consider proposals for public policies and structural reforms and economic and social development submitted to by the President of the Republic, with a view to articulating government relations with representatives of organized civil society.” (Casa Civil, 2017[29])

CDES is one of the main governing bodies of the Federal Executive, whose diverse themes also include digital government and digitalisation, contextualised by a broad perspective of social development.

The Interministerial Committee of Digital Transformation (Comitê Interministerial para a Transformação Digital, CITDigital) was created in March 2018 and is co-ordinated by the Ministry of Science, Technology, Communications and Innovations (MCTIC) to oversee the implementation of the Strategy for the Digital Transformation. The CITDigital leads the Brazilian digital transformation policy of the economy and society, where the public sector plays a fundamental role. The committee is chaired by the Civil House of the President of the Republic and brings together representatives from the Ministry of Finance; Ministry of Education; Ministry of Industry, Trade and Services; Ministry of Planning, Development and Management; and the Ministry of Science, Technology, Communications and Innovations (Casa Civil, 2018[30]).

Yet, the institutional governance of digital government in Brazil builds on several other bodies with roles relevant to the co-ordination of digital government. These include:

1. National Debureaucratization Council (Conselho Nacional para a Desburocratização), accompanying the work to modernise the public administration. As a result of a recommendation issued by the Economic and Social Development Council, the National Debureaucratization Council was created with the objective to advise the President of the Republic in the “… development of policies aimed at sustainable development, to promote administrative simplification, modernization of public management and improvement of the provision of public services to businesses, citizens and civil society” (Casa Civil, 2017[31]). The council holds trimestral meetings that bring together the Minister of the Civil House of the Presidency; the Minister of Finance; the Minister of Planning, Development and Management; the Minister of Science, Technology, Innovations and Communications; the Minister of Transparency and Control; and the Minister of the Government Secretariat. The Executive Committee of the Council joins senior representatives of the mentioned ministries and also includes representatives of civil society (Casa Civil, 2017[17]).

2. Interministerial Committee of Governance (Comitê Interministerial de Governança, CIG) advises the President of the Republic in driving the governance policy of the federal public administration according to principles of responsiveness, integrity, reliability, regulatory improvement, accountability and transparency. Created in 2017, the committee brings together the Minister of the Civil House of the Presidency of the Republic (who co-ordinates); the Minister of Finance; the Minister of Planning, Development and Management; the Minister of State for Transparency; and the Comptroller General of the Union. The committee is responsible for suggesting measures and practises, approving manuals and guidelines and issuing recommendations that contribute to the principles set by the policy of governance of the Brazilian public administration. (Casa Civil, 2018[13]).

3. Digital governance committees of the federal public administration bodies, established in 2016 bring together top senior officials from the management and digital technology branches of each institution to manage and monitor the Direction Plans for Information and Communication Technologies (Plano Diretor de Tecnologia da Informação e Comunicação) (Casa Civil, 2018[32]).

Figure 2.14. The general structure of digital governance in Brazil

Source: Ministério do Planejamento, Desenvolvimento e Gestão (2018[11]), “Estratégia de Governança Digital (EGD) — Versão Revisitada”, https://www.governodigital.gov.br/EGD.

As Figure 2.14 shows, Brazil benefits from a wide number of governance bodies that contribute to the management of the digital government policy. The leadership is spread among several committees or councils with complementary responsibilities, each with different goals and varied composition. Although this diversity of collegial bodies with an oversight role is not a problem in itself, it can contribute to a lack of clarity, gaps and overlaps. In fact, during the OECD peer review mission in Brasilia in July 2017, several public stakeholders had difficulty indicating the collective body responsible for overseeing the implementation of the digital government policy.

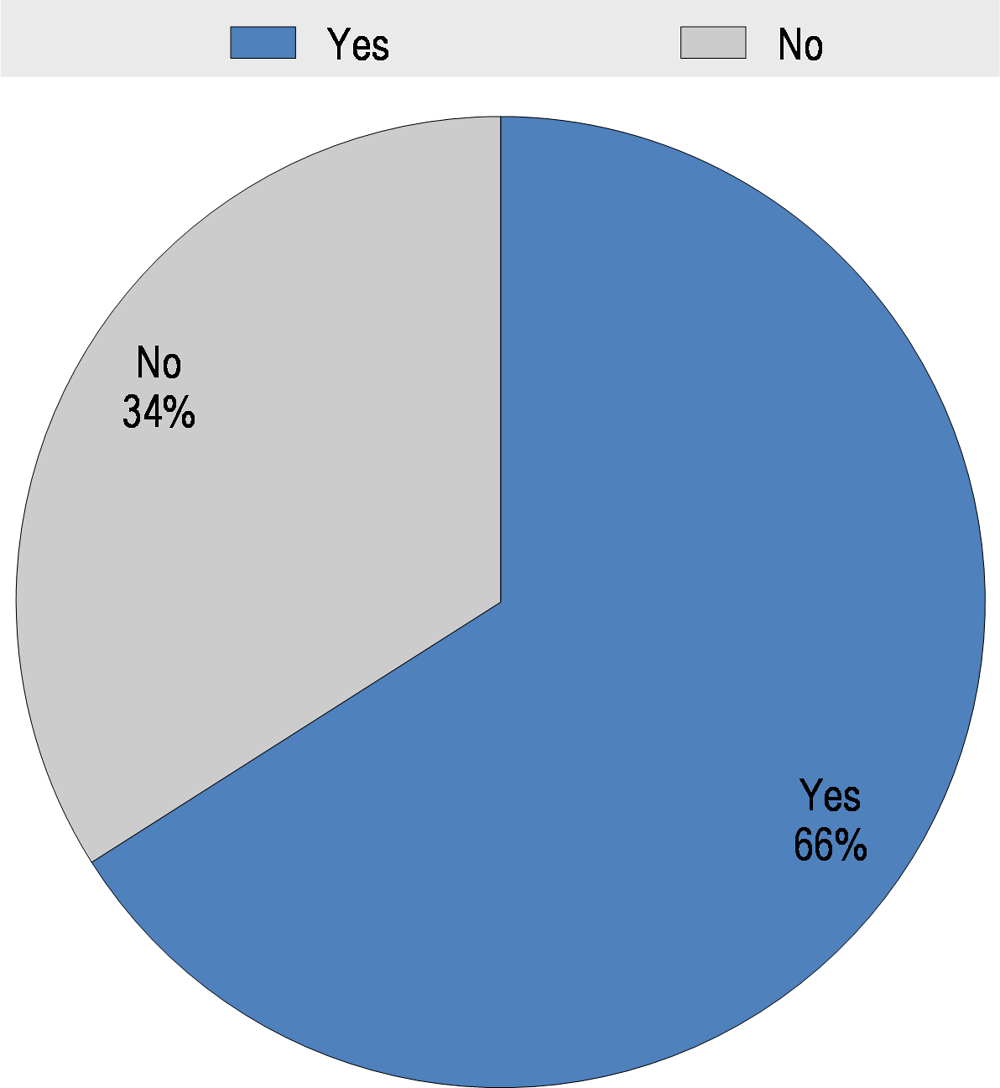

Additionally, lack of clarity regarding the governance structure can create a serious obstacle to building the necessary culture for co-operation and collaboration among sectors and levels of government, jeopardising the necessary co-ordination among public sector organisations and the co-ordinating body leading the digital government policy (see Figure 2.15).

Figure 2.15. Regular co-ordination with the co-ordinating body responsible for Brazil’s digital government policy

Note: The figure shows the percentage of participating public sector organisations that responded yes or no to the question, “Does your institution regularly co-ordinate with the federal unit or agency responsible for leading and implementing the decisions on the use of IT in the federal government?”

Source: OECD (2018[20]), “Digital Government Survey of Brazil”, Public sector organisations version, unpublished.

Considering the context presented above, the Brazilian government could consider prioritising the reinforcement of the co-ordination processes among sectors and levels of government, namely evaluating the possibility of reinforcing the role and attributions of SISP. An update of its functions and its clear connection to the digital governance committees should be promoted. The government should also consider subdividing this body into a high-level mechanism able to bring together ministers or senior officials, hand in hand with an operational and technical co-ordination mechanism (see Box 2.2. for examples of other co-ordination mechanisms in OECD countries). These two complementary levels of co-ordination could represent a very positive contribution to the coherence and sustainability of Brazil’s digital government efforts (OECD, 2016[3]).

Box 2.2. Examples of co-ordination mechanisms in OECD countries

Australia

In Australia, there is a strategic-level committee, the Digital Transformation Committee of Cabinet, which sits under the Cabinet and is chaired by the Prime Minister.

The Service Delivery Leaders is a steering committee comprised of senior public servants from major government departments. The Service Delivery Leaders is an early consultation point for Digital Transformation Office activities with a whole-of-government impact, including advice on strategy and co-ordinated service delivery activities across government. The Service Delivery Leaders may also create subordinate boards, working groups or other bodies to undertake specific work.

Spain

The ICT Strategy Commission (CETIC), an inter-ministerial body at the highest political level comprising senior officials from all ministries, defines the strategy that once approved goes to the Council of Ministries. The CETIC also defines the services to be shared and determines the priorities for the investments, reports on draft laws, regulations and other general standards with the purpose of regulating ICT matters for the general state administration. Furthermore, the CETIC promotes collaboration with the autonomous regions and local authorities for the implementation of integrated inter-administrative services.

The Committee of the Directorate for Information Technologies and Communication includes 25 chief information officers of the different ministries (13) and agencies (12), and the deputy directors for ICTs of all ministries and units. This committee leads the co-ordination of the implementation of ICT projects.

Source: OECD (2016[3]), Digital Government in Chile: Strengthening the Institutional and Governance Framework, OECD Digital Government Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264258013-en.

References

[13] Casa Civil (2018), Decreto n. 9.203, de 22 de Novembro de 2017 - Dispõe sobre a política de governança da administração pública federal direta, autárquica e fundacional., http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2015-2018/2017/decreto/D9203.htm (accessed on 16 July 2018).

[30] Casa Civil (2018), Decreto n. 9.319 de 21 de Marco de 2018 - Institui o Sistema Nacional para a Transformação Digital e estabelece a estrutura de governança para a implantação da Estratégia Brasileira para a Transformação Digital, http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2015-2018/2018/decreto/D9319.htm (accessed on 17 July 2018).

[34] Casa Civil (2018), Decreto n. 9.319 de 21 de Marco de 2018 - Institui o Sistema Nacional para a Transformação Digital e estabelece a estrutura de governança para a implantação da Estratégia Brasileira para a Transformação Digital, http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2015-2018/2018/decreto/D9319.htm (accessed on 17 July 2018).

[32] Casa Civil (2018), Decreto nº 8.638 de 15 de Janeiro de 2016 - Institui a Política de Governança Digital no âmbito dos órgãos e das entidades da administração pública federal direta, autárquica e fundacional, http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2015-2018/2016/decreto/d8638.htm (accessed on 16 July 2018).

[31] Casa Civil (2017), Decreto de 7 de Março de 2017 - Cria o Conselho Nacional de Desburocratização – Brasil Eficiente e dá outras providências, https://www.anoreg.org.br/site/2017/03/08/decreto-cria-o-conselho-nacional-para-a-desburocratizacao/ (accessed on 15 July 2018).

[16] Casa Civil (2017), Decreto n. 9.094, de 17 de Julho de 2017 - Dispõe sobre a simplificação do atendimento prestado aos usuários dos serviços públicos, ratifica a dispensa do reconhecimento de firma e da autenticação em documentos produzidos no País e institui a Carta de Serviços ao Usuário., http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2015-2018/2017/Decreto/D9094.htm (accessed on 17 July 2018).

[17] Casa Civil (2017), Governo instala Conselho Nacional para a Desburocratização — Casa Civil, http://www.casacivil.gov.br/central-de-conteudos/noticias/2017/junho/governo-instala-conselho-nacional-de-deburocratizacao/view (accessed on 15 July 2018).

[29] Casa Civil (2017), Lei n. 13.502, de 1 de Novembro de 2017 - Estabelece a organização básica dos órgãos da Presidência da República e dos Ministérios; altera a Lei no 13.334, de 13 de setembro de 2016; e revoga a Lei no 10.683, de 28 de maio de 2003, e a Medida Provisória no 768, de 2 de fevereiro de 2017., http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2015-2018/2017/lei/L13502.htm (accessed on 15 July 2018).

[33] Casa Civil (2016), Lei n. 13.341, de 29 de Setembro de 2016 - Altera as Leis nos 10.683, de 28 de maio de 2003, que dispõe sobre a organização da Presidência da República e dos Ministérios, e 11.890, de 24 de dezembro de 2008, e revoga a Medida Provisória no 717, de 16 de março de 2016., https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2015-2018/2016/lei/l13341.htm (accessed on 16 July 2018).

[28] Casa Civil (2011), Decreto nº 7579, de 11 de Outubro de 2011 - Dispõe sobre o Sistema de Administração dos Recursos de Tecnologia da Informação - SISP, do Poder Executivo federal., http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2011-2014/2011/decreto/d7579.htm (accessed on 15 July 2018).

[8] Casa Civil (2000), Decreto de 18 de Outubro de 2000 - Cria, no âmbito do Conselho de Governo, o Comitê Executivo do Governo Eletrônico, e dá outras providências, http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/DNN/DNN9067.htmimpressao.htm (accessed on 16 July 2018).

[6] Casa Civil (2000), Decreto de 3 de Abril de 2000 - Institui Grupo de Trabalho Interministerial para examinar e propor políticas, diretrizes e normas relacionadas com as novas formas eletrônicas de interação., http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/DNN/2000/Dnn8917.htm (accessed on 16 July 2018).

[19] Casa Civil (2000), Decreto n. 3505, de 13 de Junho de 2000 - Institui a Política de Segurança da Informação nos órgãos e entidades da Administração Pública Federal., http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/decreto/d3505.htm (accessed on 16 July 2018).

[18] Controladoria-Geral da União (2018), Parceria para Governo Aberto - Brasil — OGP Parceria para Governo Aberto, http://www.governoaberto.cgu.gov.br/ (accessed on 17 July 2018).

[27] Government Digital Service (2018), Government Digital Service - GOV.UK - About us, https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/government-digital-service/about (accessed on 16 July 2018).

[14] Grupo de Trabalho Interministerial (2017), Estratégia Brasileira para a Transformação Digittal - Documento Base para Discussão Pública, http://convergecom.com.br/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/EDB_Relatorio_Consulta.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2018).

[7] Grupo de Trabalho Novas Formas Eletrônicas de Interação (2000), Proposta de Política de Governo Eletrônico para o Poder Executivo Federal, https://www.governodigital.gov.br/documentos-e-arquivos/E15_90proposta_de_politica_de_governo_eletronico.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2018).

[15] Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia, I. (2018), Estratégia Brasileira para a Transformacão Digital, http://www.mctic.gov.br/mctic/export/sites/institucional/estrategiadigital.pdf (accessed on 13 July 2018).

[11] Ministério do Planejamento, Desenvolvimento e Gestão (2018), Estratégia de Governança Digital (EGD) — Versão Revisitada, https://www.governodigital.gov.br/EGD (accessed on 15 July 2018).

[10] Ministério do Planejamento, Desenvolvimento e Gestão (2018), Estratégia Geral de TIC — Governo Digital, https://www.governodigital.gov.br/EGD/historico-1/estrategia-geral-de-tic (accessed on 16 July 2018).

[23] Ministério do Planejamento, Desenvolvimento e Gestão (2018), Secretaria de Gestão (SEGES) — Ministério do Planejamento, Desenvolvimento e Gestão, http://www.planejamento.gov.br/acesso-a-informacao/institucional/unidades/secretaria_de_gestao (accessed on 13 July 2018).

[21] Ministério do Planejamento, Desenvolvimento e Gestão (2018), SETIC — Secretaria de Tecnologia da Informação e Comunicação, http://www.planejamento.gov.br/acesso-a-informacao/institucional/unidades/setic (accessed on 12 July 2018).

[12] Ministério do Planejamento, Orçamento e Gestão (2016), Estratégia de Governança Digital (EGD), http://www.planejamento.gov.br/EGDSecretaria (accessed on 16 July 2018).

[22] Ministério do Planejamento, Orçamento e Gestão (2016), Portaria nº 68, de 7 de Março de 2016 - Aprova a Estratégia de Governança Digital da Administração Pública Federal para o período 2016-2019 e atribui à Secretaria de Tecnologia da Informação a competência que especifica., https://www.governodigital.gov.br/documentos-e-arquivos/Portaria%2068%20-%20EGD.pdf/view (accessed on 16 July 2018).

[24] Ministério do Planejamento, D. (2018), Estrutura Organizacional — Ministério do Planejamento, Desenvolvimento e Gestão, http://www.planejamento.gov.br/acesso-a-informacao/institucional/estrutura-organizacional (accessed on 13 July 2018).

[25] OECD (2018), Digital Government Survey of Brazil, Central version.

[20] OECD (2018), Digital Government Survey of Brazil, Public sector organisations version.

[26] OECD (2017), Digital Government Review of Norway: Boosting the Digital Transformation of the Public Sector, OECD Digital Government Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264279742-en.

[3] OECD (2016), Digital Government in Chile: Strengthening the Institutional and Governance Framework, OECD Digital Government Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264258013-en.

[5] OECD (2016), Government at a Glance: Latin America and the Caribbean 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264265554-en.

[2] OECD (2014), Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies, OECD, http://www.oecd.org/gov/digital-government/Recommendation-digital-government-strategies.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2018).

[4] OECD (2014), Survey on Digital Government Performance, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://qdd.oecd.org/subject.aspx?Subject=6C3F11AF-875E-4469-9C9E-AF93EE384796 (accessed on 16 July 2018).

[1] OECD (forthcoming), Creating a Citizen-Driven Environment through Good ICT Governance – The Digital Transformation of the Public Sector: Helping Governments Respond to the Needs of Networked Societies, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[9] Secretário de Logística e Tecnologia da Informacão (2005), Portaria Normativa n. 5, de 14 de Julho de 2005 - Institucionaliza os Padrões de Interoperabilidade de Governo Eletrônico - e-PING, no âmbito do Sistema de Administração dos Recursos de Informação e Informática – SISP, cria sua Coordenação, definindo a competência de seus integrantes e a forma de atualização das versões do Documento, https://www.governodigital.gov.br/documentos-e-arquivos/legislacao/Portaria_e-PING_-14_07_2005.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2018).

Notes

← 1. For instance, the Digital Governance Strategy (EGD) was launched in the beginning of 2016, during the second mandate of President Dilma Rousseff. The Secretary of Information Technology in the Ministry of Planning, Budget and Management was Mr. Cristiano Heckert. The updated version of EGD was launched in May 2018, during the mandate of President Michel Temer. The current Secretary of Information Technology is Mr. Luís Felipe Salin Monteiro.

← 2. SETIC results from an integration process involving the former Information Technology Secretariat (STI) with the Information Technology Directorate (DTI) (Ministério do Planejamento, Desenvolvimento e Gestão, 2018[21]).

← 3. Law no. 13,341 of 29 September 2016 transforms the Ministry of Planning, Budget and Management into the Ministry of Planning, Development and Management (Casa Civil, 2016[33]).