The potential of digital technologies to spur more open and collaborative processes was always assumed to be one of the greatest assets of the digital revolution in Brazil. This chapter seeks to explore what can provide a transformative catalyst to digital service delivery beyond technology. The chapter focuses on the digital transformation of public service delivery in Brazil, discussing topics such as the relevance of digital-by-design approaches, the use of emerging technologies and the future development of cross-border services in the Latin America and Caribbean (LAC) region.

Digital Government Review of Brazil

Chapter 5. Towards transformative, citizen-driven digital service delivery in Brazil

Abstract

Introduction

As governments modernise public operations and processes, they are required to consider how citizens and businesses are increasingly accessing goods and services digitally. In OECD countries and partner economies, the digitalisation of economies and societies is rapidly changing citizens’ consumption habits and expectations for service delivery. As analogue processes moved on line, user experiences such as banking on line, making travel arrangements or conducting research on line changed the ways in which services were delivered. More recently, there has been a transformation of the user experience in how goods and services from private sector providers such as Airbnb, Amazon or Uber are delivered. Today’s digital economies and societies demand digital governments (OECD, forthcoming[1]). Governments are required to understand the impact that digital has had on their economies and societies in order to understand how to use it to help serve their citizens better.

The use of technology is not the driver of the changes that citizens and businesses are currently experiencing. Digital transformation reflects indeed a broader phenomenon related to how individuals interact and engage with one another, how they access services, how they search, find and use information. Ultimately, economies, societies and governments are experiencing a disruption of how they function.

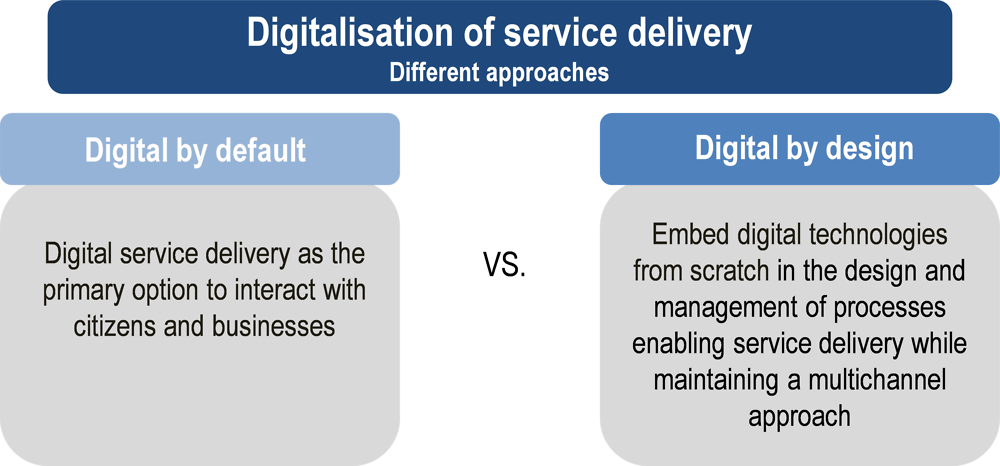

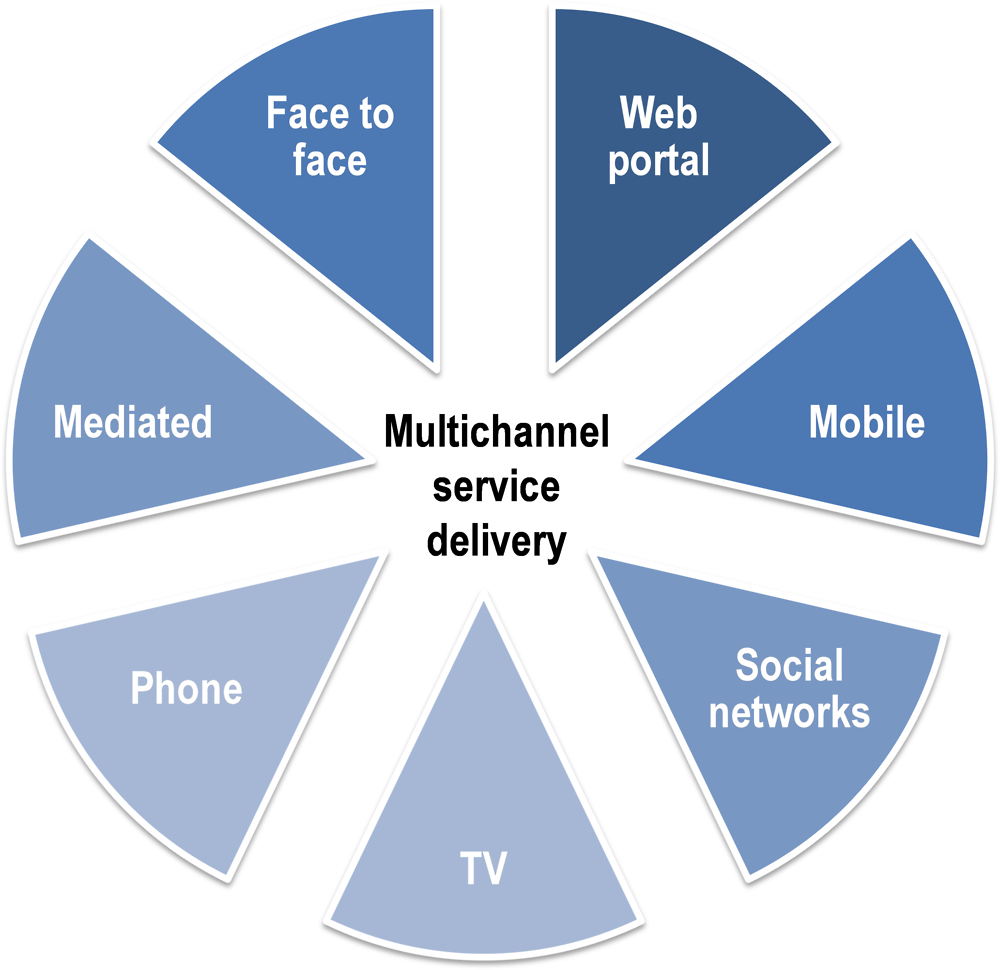

While citizens are increasingly using digital services to fulfil their diverse needs, alternative service deliveries such as telephone, face to face and mail (i.e. paper) remain very relevant for several segments of the population in the majority of the economic and social sectors of OECD countries and partner economies. A policy spurring a digital-by-design approach requires building on the full potential of digital technologies, from the start, for improved efficiency and effectiveness of public service delivery to increase citizen satisfaction, while securing the availability of a multichannel approach for service delivery. While digital-by-default policies foresee digital as the privileged or unique channel of service delivery – at the risk of engendering new forms of exclusion ‑ in a digital-by-design approach, the focus is not on the digital delivery channel. It is rather on securing equal efficiency and effectiveness of service delivery regardless of the channel used to access the service, through use of technology as only an option to run the internal processes, while digital remains just one of the delivery channels (e.g. face-to-face or digitally assisted service delivery (see Figure 5.1).

Strengthening a digital-by-design approach will require governments to also consider the following priorities:

1. understanding emerging opportunities to enhance citizens’ well-being and quality of life

2. mapping the level of digital literacy across societies to leverage the benefits of technology to deliver equitable and inclusive benefits.

Digital service delivery provides governments with the opportunity to simplify and transform the way services have been traditionally delivered. Effective use of digital technologies should become more about learning to find ways to understand and support citizens and less about how to streamline internal government business processes. In fact, a service designed effectively to incorporate citizen needs, by streamlining services and enabling data interoperability between government institutions, will be more effective given the holistic view and system-thinking approach that supported its development. Citizen-driven approaches then push the boundaries of what digital technologies are capable of to bring citizens and governments closer together. Combining the two concepts of “government as a platform” and “citizen-driven” favours a coherent use of technologies across policy areas and all levels of government, thus drawing the public sector closer to citizens and allowing for the co-creation of public value.

Figure 5.1. Digital by default vs. digital by design

Source: Author.

This chapter seeks to understand the concepts of citizen-driven service delivery along with the key enablers that can help government break down silos and improve the implementation of current digital transformation strategies in Brazil.

Integrated digital service delivery: Focusing on citizens’ needs

In Brazil, public services are mostly provided by the states and the municipalities. Indeed, the amount of services provided by the federal government is not substantial when compared with the other levels of government. Though most public services that citizens receive will be from states and municipalities, and policy directions from the federal level do not always filter down easily to the local level, this should not mean that any less consideration should be made for the delivery of services. The effort to understand citizens in terms of what they need and what provides value to them or what makes their lives better is key at all levels. The need to seamlessly integrate services for the benefit of the user is all the more important and is faced not only by Brazil but by most countries with federated systems.

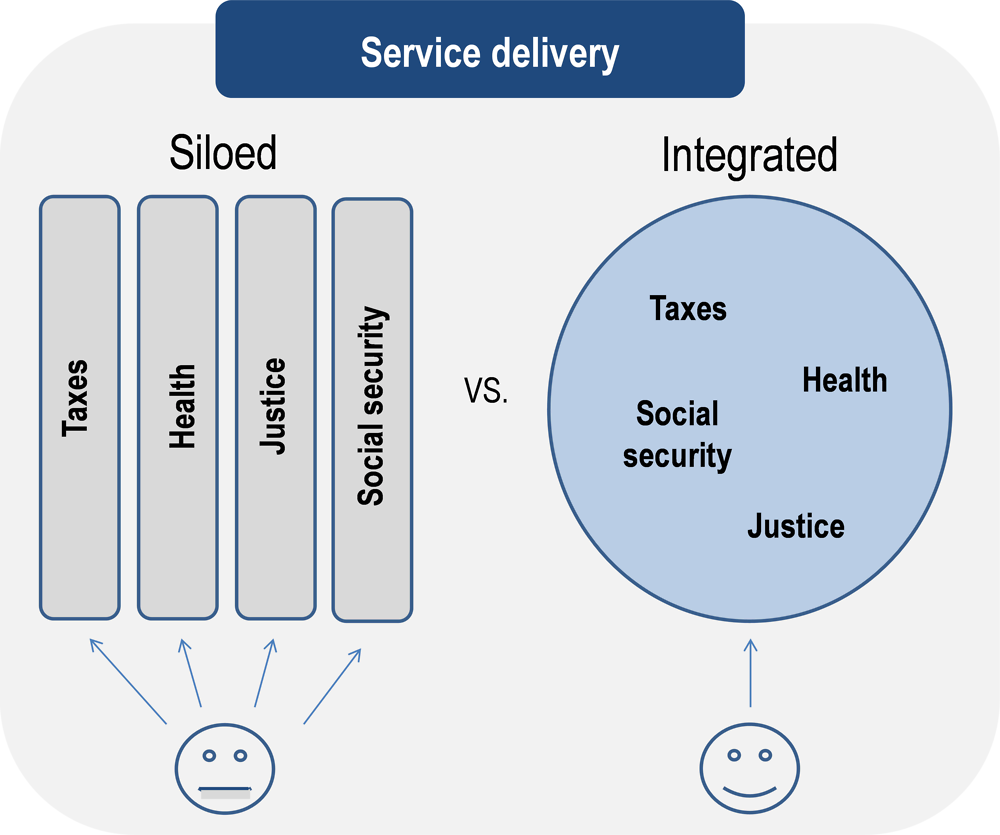

Progress towards digital government, including reinforcing data interoperability, process-flow mapping and integrated service delivery, is an opportunity for the public sector to improve citizens’ experiences of services. Potential gains include improving procedures, avoiding gaps, reducing overlaps and reinforcing simplicity in service delivery. Figure 5.2 illustrates integrated service delivery, where the user experience is put at the centre of service delivery design.

Nevertheless, integrated service delivery in the back end should be embraced together with a multichannel approach in the front end to add convenience and inclusion to benefits offered to citizens through public services (see Figure 5.3).

Figure 5.2. Siloed vs. integrated service delivery

Source: Author.

Figure 5.3. Multichannel service delivery approach

Source: Author.

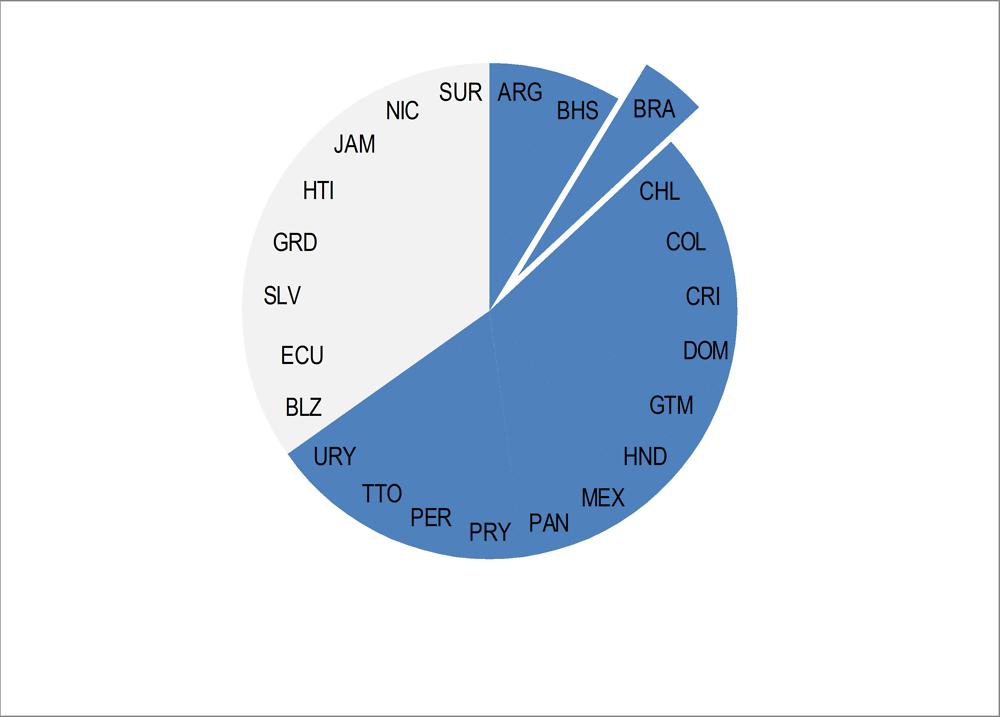

As is the case in over half of Latin America and Caribbean (LAC) countries, Brazil has a national citizens’ portal (see Figure 5.4).With its 700 services, the centralised Services Portal (Portal de Serviços) (www.servicos.gov.br) is the main online one-stop shop for government services in Brazil. The availability of services in an integrated way provides the citizen with a simplified method for finding and accessing available services. With the Platform of Digital Citizenship (Plataforma de Cidadania Digital) (Casa Civil, 2016[3]), the Brazilian government incorporated a unique digital authentication system into the Services Portal and increased the number of fully transactional services to allow for the evaluation of citizens’ satisfaction with digital services and improve the global monitoring of digital service delivery. The cross-cutting initiative is focused on transforming the delivery of public services on line through the improvement of the Services Portal.

Figure 5.4. Existence of a national citizens’ portal for government services in LAC countries

Source: OECD (2014[4]), “Survey on Digital Government Performance”, https://qdd.oecd.org/subject.aspx?Subject=6C3F11AF-875E-4469-9C9E-AF93EE384796 (accessed on 16 July 2018).

To build on the momentum of a single authentication system for users, coherent decisions on the digital service policy for the government are recommended to ensure the cohesive integration of digital with service delivery with user research. This should be integrated into the Digital Governance Strategy. At the crossroads of interaction with each one of these integral pieces to digital service delivery sits the Information Communications Technology Secretariat (Secretaria de Tecnologia da Informação e Comunicação, SETIC) in Brazil. SETIC is responsible for defining the public policies related to the use of technology in the federal public administration (see Chapter 2). Already the Secretariat holds the pieces that would help create a strong digital service policy with consideration for the existing digital governance policy (Ministério do Planejamento, 2018[5]).

Although the country has several good examples of digital openness and collaboration in the public sector, a cross-cutting digital service approach as a core policy component of the Digital Governance Strategy would help promote collaboration between different sectors and levels of government, foster co-creation of public value with civil society, a cultures of sharing and reuse of government data, and lead to more inclusive and accessible mechanisms for the entire ecosystem of users.

Harnessing mobile technologies and the potential of social media

Both mobile and social media technologies provide governments with opportunities to get closer to citizens and collaborate with them directly. Moving from e-government to digital government approaches broadens and expands the notion of how digital technologies can help transform people’s interactions with governments and improve their access to goods and services (OECD, forthcoming[1]).

Social media can make communications more effective and provide networked societies with a reach that without compare in the unplugged world. Governments are recognising the power of social media to move beyond communications, to more effectively engage and collaborate with internal and external partners in the digital ecosystem (Mickoleit, 2014[6]).

In line with OECD trends, Brazil has recognised the power that social media can grant a government to connect with its people. It is important to note that Brazil gives thought to the digital rights of its citizens in the Digital Transformation Strategy (Estratégia Brasileira para a Tranformação Digital) by making mention that though the technology is an engaging and collaboration asset, enabling a better understanding of citizens’ needs, there is also a need to protect the fundamental rights of citizens.

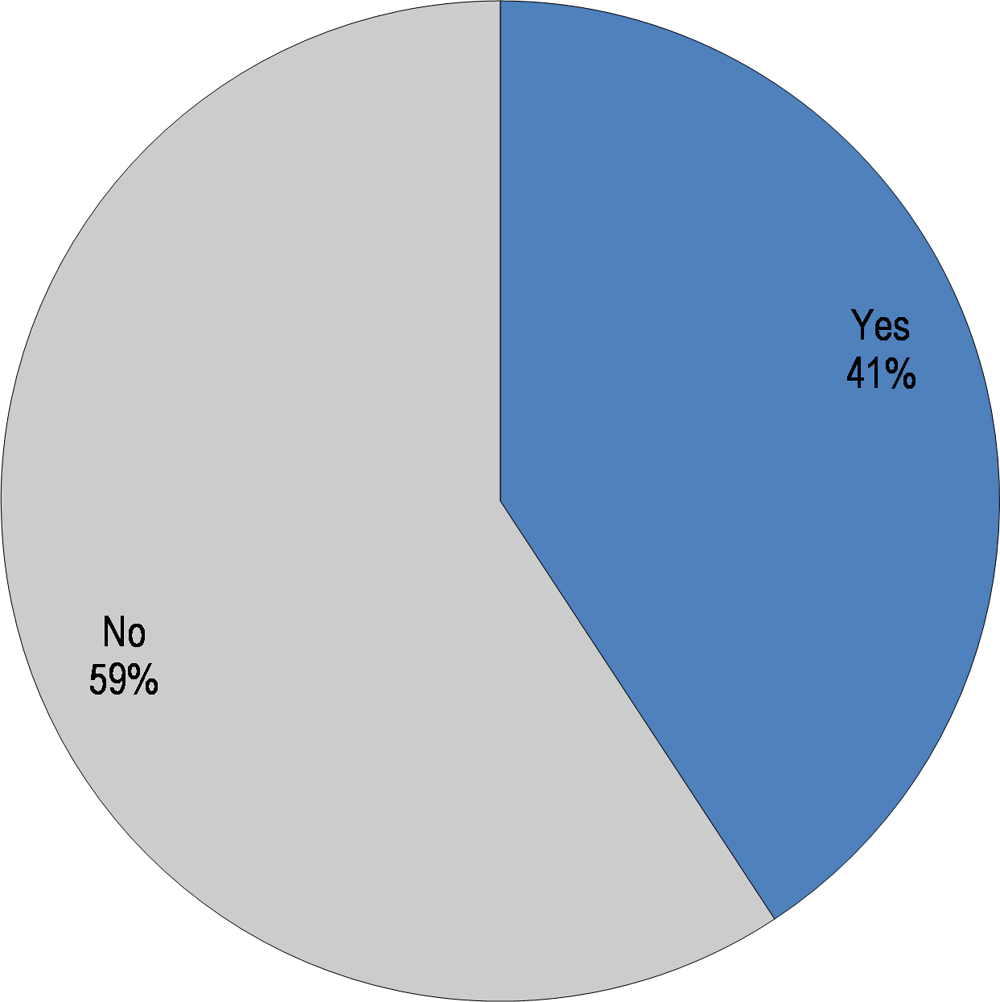

Of the federal government institutions that answered the Digital Government Survey of Brazil, 41% stated that they use social media to communicate with citizens about their institutional strategy/initiatives, reflecting a culture of progressive use of digital technologies to improve relations between the public sector and the ecosystem of digital government stakeholders (see Figure 5.5).

Figure 5.5. Social media use in the Brazilian federal government

Source: OECD (2018[7]), “Digital Government Survey of Brazil”, Public sector organisations version, unpublished.

The power and reach of mobile technologies, too, cannot be overlooked as their role in the current digital transformation of economies, societies and governments is substantial (OECD/ITU, 2011[8]). Mobile communications devices have been able to reach large parts of populations faster than fixed Internet broadband has been able to. Indeed, they have reached territories that may never have the infrastructure required for fixed Internet or wired phone service. And so by virtue of their ubiquity, mobile communications have offered the opportunity to governments to bring public services in all its machinations closer to citizens, adding mobile to its delivery channels.

As mentioned in Chapter 1, Brazil is a large and geographically diverse country. Fixed broadband access is present in 40% of households, and growth is slow due to regions that are difficult to access, which makes laying the infrastructure for fixed broadband problematic (Government of Brazil, 2018[9]). However, mobile technology is able to leapfrog this infrastructure issue of fixed broadband. For example, in 2014, 76% of users accessed the Internet through mobile, compared to 80% via computer. By 2015, mobile Internet use rose to 89%, while computer access fell to 65% (Comitê Gestor da Internet no Brasil, 2016[10]).

Digital inclusion has improved greatly due to mobile technologies. However, the government will need to consider the spectrum of access when thinking about digital service delivery. To ensure that a digital divide is not created, multichannel access to services will need to include a range of mobile access – from SMS texting to 4G access.

In using new technologies to rethink and re-engineer business processes, simplify procedures and open new channels of communication and engagement with civil society, the government can reinforce user-driven approaches. This will allow Brazil to realise the potential for digital technologies to empower citizens while enabling public authorities to bring citizens’ voices and needs to the fore, and use technologies to respond to these needs.

A digital rights culture

For as many potential opportunities and efficiencies that can be realised from digital technologies, important ethical decisions with regard to citizens’ well-being need to be at the forefront of governments’ efforts to foster the digital transformation of the public sector. Trust in institutions requires that these are competent and effective in delivering on their mandates and that they operate consistently with a set of values that reflect citizens’ expectations of integrity and fairness (OECD, 2017[11]). The use of data and algorithms to support the public administration should be framed by highly ethical and transparency requirements, avoiding any doubt in possible biased results arising from opaque policy procedures and services. Consent models, allowing the citizens to have the final word on the use of data and the use of emerging technologies for the production of decisions or the delivery of services, should be in place to build citizen trust in digital change. The involvement of civil society to promote accountability in the use of emerging technologies and investment in transparency procedures and initiatives should be considered by governments as requirements for a digitally transformed public sector. This section will outline how the Brazilian government can build citizen trust more readily through public engagement and incorporating civil society’s inputs throughout the transformation process.

Pillar 1 of the OECD Recommendation on Digital Government Strategies (OECD, 2014[12]) highlights the relevance of digital technologies for more open, inclusive, engaging and collaborative government as a means to better support the growth of the economy and improve citizen well-being.

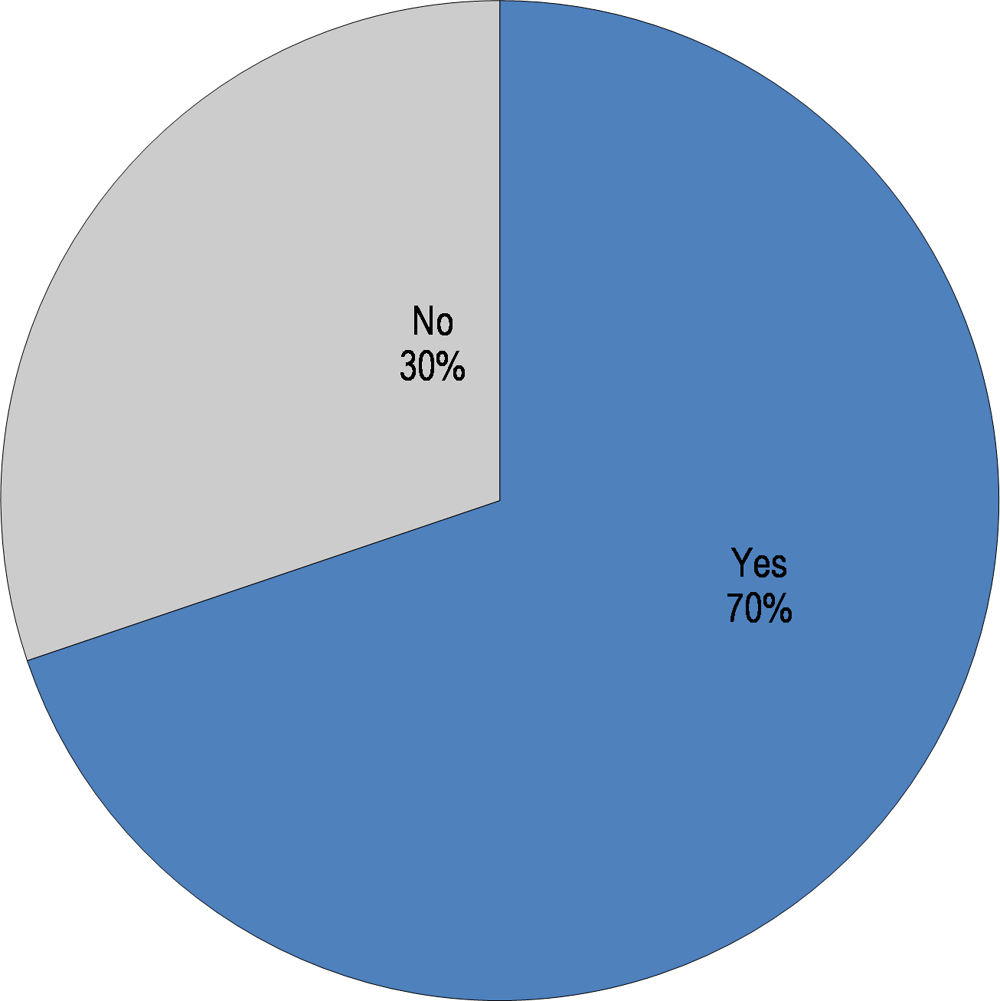

Brazil is in many ways a good example of cultivating this engagement with citizens by having conducted extensive consultation and engagement with civil society, including undertaking a digital public consultation process when developing the Brazilian Strategy for Digital Transformation (see Chapter 2). As reflected in Figure 5.6, 70% of institutions surveyed in the Brazilian federal government for this review have used digital platforms to engage with citizens.

Figure 5.6. Institutional use of digital platforms to engage with citizens in decision-making processes

Source: OECD (2018[7]), “Digital Government Survey of Brazil”, Public sector organisations version, unpublished.

In addition, several projects take into account the rights of the citizen in a digital world. For instance, the Participa.br platform was developed as a portal for public discussion and consultation on policy issues. The platform has been used by different public sector institutions at the federal level to crowdsource input from citizens on initiatives relevant to digitalisation such as the Internet of Things plan, the Digital Governance Strategy (see Chapter 2) and open data initiatives.

The Brazilian Civil Rights Framework for the Internet (Marco Civil da Internet) was passed into law in 2014 (Casa Civil, 2014[13]), following a process that began six years prior. The framework institutionalises a set of public policies with a focus on the citizen, covering privacy, record keeping, and net neutrality. As society and businesses in Brazil increasingly operate in the digital sphere, determining the rights of the citizen became a central priority for the government. At the very heart of the law is the promise that Internet access is a requirement for civil rights, reflecting the government’s very proactive approach to promoting digital inclusion (see Box 5.1) and protecting citizens’ rights as the digital transformation progresses.

Box 5.1. Challenges for digital inclusion in Brazil

The challenges for digital inclusion in Brazil were the subject of a report by the Federal Audit Office (TCU) entitled, Public Policy on Digital Inclusion (2015). Contemplating the actions of the last 15 years, the report highlights the creation of the Electronic Government - Citizen Assistance Service (GESAC) Programme in 2002, under the responsibility of several ministries, with the aim of providing connections to the Internet, mostly via satellite, to telecentres, schools, and public agencies located in remote and border regions. Other projects are also mentioned in this report, such as the Digital Inclusion Programme, the Connected Citizen Project, the One Computer Per Student (UCA) Project and the Telecentros.br Programme. Of particular note are the following projects: Broadband Programme in Schools (PBLE), the National Broadband Programme (PNBL), and the Special Taxation Scheme of the National Broadband Programme for the Implementation of Telecommunications Networks (REPNBL).

The programme for launching the Geostationary Defence Satellite Strategic Communications - SGDC is mentioned as the most relevant action of the PNBL in financial terms. In addition, it also makes reference to the international negotiation for the construction of the new submarine cable connecting Brazil and Europe, in order to increase the capacity of traffic between the two continents, to reduce costs of transmission and to provide more security to the data transported.

In addition, the TCU report points to the lack of digital literacy of the population as an obstacle to the full digital inclusion of Brazilian society, as well as the lack of formal literacy on the part of the population. Finally, the TCU report diagnoses the management of public policy, highlighting the difficulty of co-ordination and articulation in different government environments: between federal government agencies that act in some way in digital inclusion, and also between central government and state and municipal agencies.

Source: Government of Brazil (2018[9]), Estratégia Brasileira para a Transformação Digital E-Digital, Government of Brazil, Brasilia..

In 2011 Brazil became one of the founding partners of the Open Government Partnership (OGP). This landmark partnership heralded a new public service culture of openness and transparency, demonstrating Brazil’s public administration willingness to be not only more open and transparent but also more responsive to its constituents. The Open Government Partnership requires members to publish action plans that are developed with public consultation. These plans must be renewed and updated every two years, providing governments with the opportunity to become closer with their citizens. The Brazilian action plans are published on a centralised portal for open government (http://governoaberto.cgu.gov.br/).

Following adherence with the OGP, Brazil published its first access to information law one month later (Casa Civil, 2011[14]). The law applies to federal, state and municipal levels of government and represented an important move of the government towards openness. Nevertheless, recent assessments of its implementation have raised some critical issues among the ecosystem of digital government stakeholders (Michener, Contreras and Niskier, 2018[15]). The general public does not seem to be aware of the law, nor how citizens can access information. Lack of awareness of laws is a common challenge faced by many governments. However, in the case of access to information, capacity within the government to administer the law could be increased to address requests by citizens for information through digital-by-design means.

Recently, a bill was passed into law (Lei no. 13,709/2018) on data protection, specifically for the protection of individual citizens’ personal data. It is an important landmark bill that covers a wide array of situations. The bill defines personal data as “the information related to a person who is ‘identified’ or ‘identifiable’”. The bill also states that given some information on its own does not reveal to whom it would be related (an address, for example), if processed along with other information, could indicate the identity of a person (address combined with age, for example). Children are covered in the bill by identifying parameters for processing information about them. The bill extends to the collection, handling in digital media of personal registration data and the processing of personal data rules for private sector companies as well. International cross-border data collection is also included. With regard to protecting citizens’ rights, the key points of the bill are:

A special register of “sensitive” data covering a citizen’s race, political opinions, beliefs, health status and genetic characteristics should be established.

Use of this special register of “sensitive” data is restricted since it carries risks of discrimination and other damages to the person.

Authorisation to collect and process data must be requested clearly, in a specific clause, and not in a generic way.

In case of any security incident that may cause damage to the owner of the information, the company is obliged to communicate to the person and to the competent body.

An inspection and/or regulatory body should be established for oversight.

When determining how technologies can provide value, governments need to not only determine what efficiencies can be provided internally to create a more efficient bureaucracy but also what value it brings to citizens. The “once-only principle” is one example that provides benefits to both governments and citizens. Essentially, the principle means that the citizens should only have to provide personal data to the public sector once, with governments bearing the burden of establishing the necessary system interoperability that enables the different public sector organisations to access and share citizens’ data as needed, so citizens should no longer have the administrative burden of re-submitting personal data for every service needed.

This personal data can be stored in authoritative databases known as base registries. As the authentic sources of data for public administrations, base registries are one of the foundational elements that make the once-only principle a reality. It requires system-thinking and whole-of-government approaches rather than agency-based ones to enable the public sector to make use of the data it already holds. This was the case with the UK Digital Transformation Strategy, which sought to develop the infrastructure of base registries. Norway established four base registries to maximise user-centred services and create a data-driven public sector (OECD, 2017[16]).

The Brazilian government could consider investing in transparency mechanisms and in establishing an ethical framework for the implementation of ethical requirements, building on the recently approved law on data protection (Casa Civil, 2018[17]). This may spur the responsible and accountable adoption of emerging technologies, assisting public sector organisations (see the section above, “Harnessing mobile technologies and the potential of social media”) in reinforcing citizen trust, a critical requirement for the success of decisions on the expanded use of emerging technologies.

It is important to establish legal frameworks and policies to ensure that the government has thoroughly considered the digital rights of its citizens while undergoing a digital transformation (see also Chapter 4). This thoroughness is strengthened in the lengths that Brazil has gone to consulting with citizens and businesses on digital rights. Though setting the foundations for good governance is essential, the Brazilian government will need to ensure that it can demonstrate respect of digital rights so as to ensure that citizens and businesses feel a “return on investment” for their time spent in engagement and consultation with the government. For example, the government should be able to demonstrate that data in a base registry should be auditable and provide assurances to citizens regarding what their personal data is used for. Collaboration and communication are key areas to concentrate on to improve the implementation and enactment of policies and laws.

Open government data for improved service delivery

Digital governments enable policy design to occur in a more coherent and integrated way by using technology to foster collaboration, not only within public institutions but also more broadly with citizens. Governance over public sector (government) data and information and how these can be used is critical. The ability to collect, produce and process massive amounts of data to draw insights and identify trends is a core characteristic of new digital organisations and business models. It is only by leveraging data from traditional and alternative sources that the public administration can proactively gain a better understanding of users’ needs, continuously improve its performance and engage external stakeholders in public value creation.

This evolution can be seen in moving from access to information to open data. In 2011, Brazil adopted an access to information law, Lei de Acesso à Informação Pública (Casa Civil, 2011[14]). Even though this important step, taken a month after Brazil became a founding member of the Open Government Partnership, is extremely important (OECD, 2018[18]), the experience across OECD countries and other economies shows that a strong focus on access to information may lead to reactive behaviours more focused on complying with citizens’ requests as per the law, rather than proactively providing data and information.

Public bodies produce and commission massive quantities of data and information. By sharing these data in ways that are easily accessible, usable and understandable by citizens and businesses, governments improve access to valuable information with the potential to transform public services. Exposing the data can lead to uses never considered before and therefore spur innovation and support economic and social development. Furthermore, open data opens the government up to scrutiny and grants citizens access to information that effectively allows the public to evaluate the government. This transparency brings government closer to the citizens it serves. Open government data (OGD) refers to data produced or commissioned by government or government controlled entities, and that can be freely used, reused and redistributed by anyone (Ubaldi, 2013[19]).

There is significant overlap among access to information (ATI) and open government data (OGD) movements, since both aim to increase the transparency of government so that all members of society can enjoy the inherent social and economic value of information that has been generated and collected with public funds. Nevertheless, there are also differences in the approaches and strategies employed by ATI and OGD. One of the main differences is that ATI advocates place emphasis on access to qualitative as well as quantitative information, which is often stored in the form of documents, whereas OGD advocates focus on data that is held in government databases, focused on both the technical and legal issues related to the access, use and reuse of these datasets.

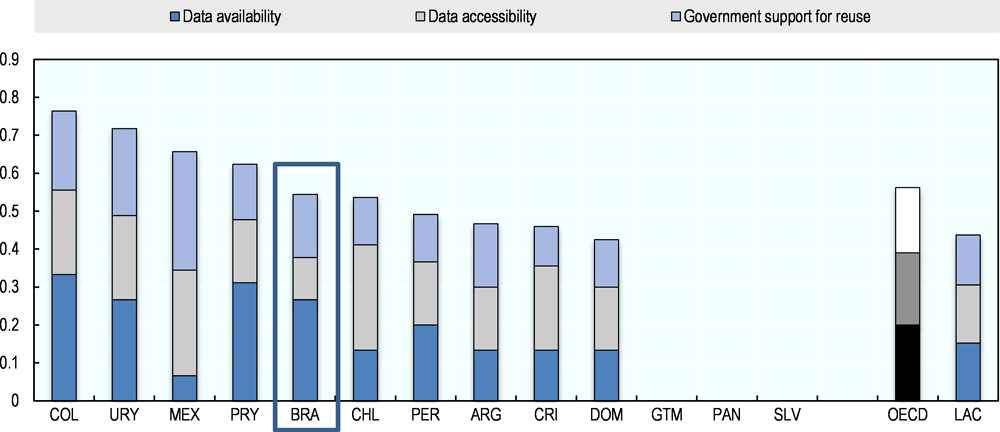

As Figure 5.7 illustrates, Brazil compares favourably with other Latin American countries in establishing open, accessible and reusable data.

Figure 5.7. OURdata Index: Open, Useful, Reusable Government Data, 2016

Note: Guatemala, Panama and El Salvador do not have a one-stop-shop portal. Data for Chile, Colombia and Mexico refer to 2014 rather than 2016.

Source: OECD (2016[20]), Government at a Glance: Latin America and the Caribbean 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264265554-en.

As the OGD movement matures, public sectors seek policy improvements that can be made, namely upon the existing portals and efforts to release data. A leader in the OGD movement, Mexico recently undertook a review of the country’s policies and initiatives (OECD, 2018[21]). One key finding was that in order for open government data to be sustainable in the long term, building capacities would be required within the public sector and across the ecosystem of OGD stakeholders. Institutions need to be provided with the incentives and the capabilities to exploit the potential of data at the institutional and sectoral level. In line with this, Brazil’s federal government will need to emphasise the critical importance of data reuse for value co-creation by institutions and the open data ecosystem at large.

Brazil has many pockets of innovative work on OGD. For example, there is the Global Data Model (Modelo Global de Dados, MGD). In mid-2009, the Interministerial Committee of the Macroprocess of Planning, Budget and Finance (MPOF) was created, formed by the Ministry of Planning, Budget and Management (MP), the Ministry of Finance (MF) and the public information and communication technology (ICT) company, SERPRO. This arose from the need to identify and integrate data between the information systems of the federal government. The elaboration of an integrated and dynamic map of data was formed by the various information systems that make up the Administrative Management Systems (EMS). These are responsible for a governmental management process such as: monitoring government programmes and actions, financial and accounting administration, procurement and contracting, budget preparation and monitoring, among others. The MGM is a significant form of data governance.

Brazil currently operates two open platforms that reflect the recognition of data as a strategic asset for the digitalisation of the public sector in Brazil:

Portal Brasileiro de dados abertos (dados.gov.br): A single national portal for OGD at the federal level

GovData (govdata.gov.br): A platform to cross-check information and produce strategic information, relaunched in 2018.

In 2015, the Association of Audit Courts of Brazil (Associação dos Membros dos Tribunais de Contas do Brasil) ran a hackathon inviting app developers, civil society organisations (CSOs) and members of Brazil’s local supreme audit institutions (SAIs) to discuss how open data could specifically contribute to the work of the SAIs, in order to develop more efficient institutional open data strategies that build on the identification of a critical mass of users and demand-driven data disclosure based on users’ needs and the context of the national open data ecosystem (OECD, 2016[22]).

Furthering the efforts on OGD and ATI, the Presidential Decree no. 8,777 of 11 May 2016, established the Brazilian national open data policy (Casa Civil, 2016[23]). Among other provisions, the decree identified a set of public sector information categories to be prioritised for publication in open and machine-readable formats, in an effort to fight corruption in the country (OECD, 2016[22]), including:

the names of civil servants in managerial and directive positions in state-owned enterprises and subsidiaries

data from the Integrated Financial Management System (SIAFI)

information on the corporate structure and ownership of companies collected by the National Register of Legal Entities

public procurement information collected through the Integrated General Services Administration (Sistema Integrado de Administração de Serviços Gerais, SIASG)

cadaster and registration information related to the control of the execution of parliamentary amendments.

The Brazilian experience clearly demonstrates that data is an asset and needs to be governed as such. Data governance is imperative to ensure a successful digital transformation from different angles: data discovery, common understanding, collaboration, interoperability and an ethical point of view. For example, though open government data recognises data as an asset, the data will not be useful if it cannot be found. If the OGD ecosystem of stakeholders does not have a common understanding of the data through metadata and common vocabularies, and data visualisation techniques are not developed to increase accessibility, the data will not be useful either. Without systems’ interoperability, full data interoperability cannot be achieved, and the value of data is not fully exploited (see Chapter 4).

Whereas Brazil has made great strides in trying to cultivate an open environment through changes to laws and introducing bills for open government data, as well as demonstrating the government’s will to innovate change via hackathons or platforms for data analysis, there remains the need for a formal strategy to educate public officials and the general ecosystem about open government data, so as to normalise the innovations that Brazil has put in place.

Emerging technologies for digital service delivery

Emerging technologies (ETs) – also known as disruptive technologies ‑ such as artificial intelligence (AI) and blockchain technology, are progressively penetrating economies and societies, with significant potential for disruption. Governments are not exempt from this digital transformation trend that could reinvent the relationship between public administrations and their constituents. ETs have the potential to generate more informed policy-making processes, creating improved capacities to monitor, manage and forecast to better serve the needs of citizens and businesses. Following the practices of top private service providers such as Google, Amazon or Netflix, which citizens are increasingly used to, public administrations can build on advanced emerging technology tools to develop convenient, tailored and proactive service approaches (OECD, forthcoming[1]). Governments now face the challenge of adapting their governance and institutional frameworks to the digital transformation underway, reinforcing capabilities, prioritising the development of technical and leadership skills and securing the necessary adjustments to legal frameworks. Governments are also required to open new channels of collaboration capable of absorbing the inputs of the ecosystem of digital government stakeholders. Public value can be generated if the opportunities of collaboration and partnerships with stakeholders on the use of AI are seized for improved service design and delivery, benefiting for instance from synergies with academia and the private sector.

Public data is one of the critical assets that ETs, namely artificial intelligence, is required to benefit from. The proper use of data analytics enables the public sector to shift from top-down and government-centred design of public services to the development of user-driven service design, responding to targeted citizens and businesses’ needs, bringing the delivery of public services to a new level of sophistication and responsiveness. Integrated cross-cutting services can be designed based on the proper combination of data produced or collected by different sectors of the public administration, enhancing policy effectiveness, reducing the burden on citizens through simplification of procedures and upscaling the efficiency of the use of public resources.

Emerging technologies based on quality public data can also lead to a shift from a reactive service delivery approach where the citizen is always required to start a service to accomplish a public duty or access a public benefit, to a proactive service delivery paradigm where the public administration is capable of anticipating citizens’ needs and progress on the provision of a specific service. For the development of this paradigm, public services are required to use ICT to improve understanding citizens and businesses, anticipating citizens’ services requests through the proper use of emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence (OECD, forthcoming[25]).

Furthermore, in a data-driven public sector, citizens can influence and contribute directly to the design and development of public service, as their data helps governments to understand their life situations and needs better, allowing for the development of more responsive, inclusive and profile-based services. Through proper data processing and analytics, the usage of digital services by citizens and businesses can also be better understood, allowing for the development of automated feedback loops that can progressively improve the usability of public services.

Given the inevitability of emerging technologies use (namely AI) in the public sector and its impact on service delivery approaches, OECD countries are progressively developing policies to address the change underway better. For instance, the government of Canada is developing a Pan-Canadian Artificial Intelligence Strategy, envisaging an increase in the number of researchers working on this technology and promoting global thinking of the leadership on the economic, ethical, policy and legal implications of advances in AI. In Finland, a steering group promoted by the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment launched a report highlighting several conditions for the country to nurture the benefits of AI. The group also developed a report on the impact of AI on the future of work. In Italy, the Artificial Intelligence Task Force led by the Agency for Digital Italy (AGID), a government agency responsible for the implementation of the Italian Digital Agenda produced a white paper on the opportunities offered by AI to improve the quality of public services. In Portugal, a research and development (R&D) programme of EUR 10 million was launched to fund the development of artificial intelligence solutions for the public sector (OECD, forthcoming[1]).

In Brazil, important policies being developed by the federal government seem to be creating the foundations and the demand for the use of emerging technologies for improved service delivery, using public data as a critical asset. Examples include:

1. Sharing of public databases

In June 2016, the Brazilian federal government decreed that the owners of public entities or those responsible for the management of official public databases should make data accessible to other public sector organisations. The main purpose of the policy is to improve the delivery of services (Casa Civil, 2016[26]).

2. The Conecta.gov platform

The recently launched interoperability platform of the federal government, Conecta.gov (www.conecta.gov.br), contains a catalogue of application programming interfaces (APIs) to promote the integration of public services and the exchange of information within the administration. The progressive integration and exchange of information among public sector entities set an adequate context for the progressive introduction of technologies such as data analytics and artificial intelligence to better monitor and forecast citizens’ needs, and to develop citizen-driven public services.

3. Simplification of service delivery

In July 2017, the federal government approved a strategic policy for the simplification of service delivery based on the once-only principle, challenging the public sector to rapidly improve its connectivity, exchange of information and management of data to maximise citizens’ convenience when interacting with the public sector.

4. Internet of Things

Considering the increasing importance of the topic of Internet of Things in the current digital transformation context, a diagnosis and a suggestion for an action plan were developed in 2017-18. The project commissioned by the National Development Bank (BNDES) and the Ministry of Science and Technology foresees three mobilising projects for the action plan, a governance structure and a monitoring framework (Banco Nacional do Desenvolvimento, 2018[27]).

Considering the foundations already in place for the improved exchange and better management of data, the current political commitment to improve service delivery, as well as some advanced examples of the use of emerging technologies in the public sector (see Box 5.2), the Brazilian government should consider building on the current momentum to promote the use of emerging technologies for improved efficiency and effectiveness, enhanced public sector intelligence and reinforced convenience for citizens and businesses.

The development of an action plan on the use of emerging technologies, for example, AI, could be considered as a complementary programmatic document of the current Digital Governance Strategy. The development of the action plan could be co-ordinated by the System for the Administration of Information Technologies Resources (Sistema de Administração dos Recursos de Tecnologia da Informação, SISP) (see Chapter 2) and executively led by the Secretariat of Information and Communication Technologies (SETIC) of the Ministry of Planning, Development and Management. Since the capacity of countries to lead the transformation through emerging technologies also depends on their ability to support R&D on this topic, the allocation of funding resources for the development of innovative service delivery solutions for public sector should also be considered.

Box 5.2. Examples of the use of emerging technologies in the Brazilian public sector

Improved economic competition

The Administrative Council of Economic Defence (Conselho Administrativo de Defesa Econômica, CADE) uses artificial intelligence to identify competition dysfunctions in critical areas of the market. Responding to the Ministry of Justice, CADE has developed improved techniques to spot cartel practices in areas such as the prices of gas.

Reinforced integrity in the public sector

The Ministry of Transparency and Comptroller General of the Union (CGU) uses artificial intelligence to find evidence of deviations in the performance of public servants. The tool supports the auditor looking at public officials’ profiles based on data such as previous irregularities, affiliation in political parties or commercial interests.

Better monitoring of public procurement

The Court of Accounts of the Union (Tribunal de Contas da União, TCU) uses artificial intelligence to analyse the procurement processes of the federal administration better. Based on the information published on the portal of public procurement, Comprasnet, the system analyses the costs of tenders and compares the information with other databases. Based on the information obtained, the system is able to identify risks and send alerts to the auditors.

Chatbot in the Services Portal

As an example of the progressive adoption of emerging technologies in the Brazilian public sector, the Services Portal (Portal de Serviços) makes available a chatbot that answers questions and provides information on several available services (e.g. passports, university allowances, tax exemptions). Although not very sophisticated and entirely dependent on quantity and quality of the information and data that supports its functioning, the chatbot called Beta is a good example of the value of using emerging technologies for service delivery.

Source: Convergência Digital (2018[28]), CADE adota inteligência artificial para agilizar combate aos cartéis - Convergência Digital - Inovação, http://www.convergenciadigital.com.br/cgi/cgilua.exe/sys/start.htm?UserActiveTemplate=site&infoid=48613&sid=3 (accessed on 08 October 2018); Government of Brazil (2018[29]), Portal de Serviços, https://www.servicos.gov.br/ (accessed on 08 October 2018); Agência Brasil (2018[30]), Órgãos públicos usam inteligência artificial para combater corrupção, http://agenciabrasil.ebc.com.br/geral/noticia/2018-08/orgaos-publicos-usam-inteligencia-artificial-para-combater-corrupcao (accessed on 08 October 2018).

Towards cross-border service delivery in the LAC region

In a progressively digitalised world, national borders are progressively ignored by people who consume content and services independently of their geographic location. The OECD Recommendation on Digital Government Strategies (OECD, 2014[12]), in its Key Recommendation 8, highlights the potential of international co-operation for knowledge sharing, development of synergies beyond national borders and joint efforts for the definition of common goals among countries’ public sectors.

In line with the trends observed in several sectors of the digital economy, the digital transformation of public service delivery is opening new perspectives for the provision of services beyond national borders. Users’ expectations based on experiences with top service providers (e.g. Google, Netflix or Uber) increasingly push governments towards a new paradigm of access and delivery of public services. Digital public platforms from different countries can also be connected, aiding in the sharing of data and information and the common recognition of digital certificates.

The European Union presents one of the most integrated efforts worldwide for the development of cross-border services, focused on the development of a European digital single market that can add value to the sum of the 28 member state national markets. Public administrations across the European Union are progressively developing cross-border services (e.g. opening a company, studying abroad, obtaining a patient summary abroad) that can bring greater convenience to users.

Building on similar efforts for the progressive integration of digital technologies in public sector activities, Latin America and Caribbean countries have strengthened their co-operation on digital government in recent years, progressively sharing knowledge and exploring synergies. Given mutual knowledge, trust and willingness to co-operate have developed with the support of networks such as the e-Government Network of Latin America and Caribbean (Red de Gobierno Electrónico de América Latina y el Caribe, Red GEALC) (Red GEALC, 2018[31]) and organisations such the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) and the Organisation of American States (OAS) the governments of LAC countries should start exploring more consistently the development of digital cross-border services in the region.

In December 2017, the Ministers of Foreign Affairs of the Mercosul States meeting in Brasilia announced the creation of a Digital Agenda Group. The group is responsible for elaborating a draft action plan with policy proposals and joint initiatives, with goals and deadlines. The draft action plan should cover areas such as the digital economy, digital government and Internet governance (MERCOSUL, 2017[32]). The creation of the Digital Agenda Group reflects the important role attributed to digital services to enhance the economic co-operation of the countries of the region.

Although presenting different levels of digital development, digital cross-border services could contribute to strengthening the economy of the region and reinforce the movement of citizens across its different countries for working, studying or touristic purposes.

Driven by the needs of citizens and businesses, the development of cross-border services should start by prioritising the following critical dimensions:

alignment of legal frameworks

adoption of common data and architecture standards

interoperability of digital identity mechanisms

mutual recognition of digital certificates.

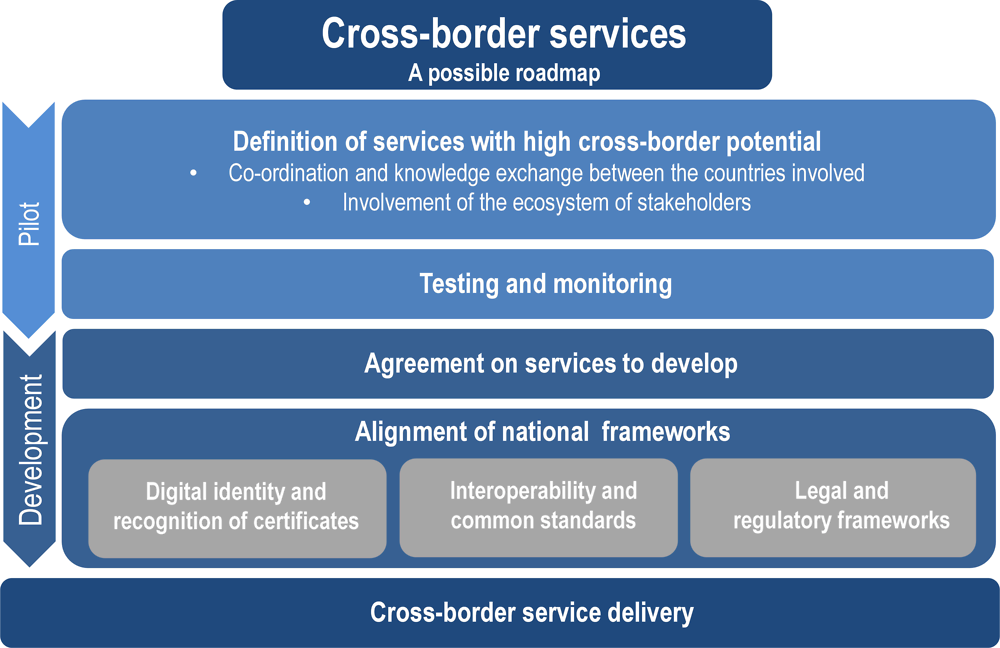

In this sense, LAC governments should explore the development of a roadmap with major steps to ensure a realistic and credible path for the integration of relevant digital services in the region (a sample roadmap is pictured in Figure 5.8). Piloting exercises should also be considered fundamental for this common regional co-operation effort.

Figure 5.8. A possible roadmap for digital service delivery in the LAC region

Source: Author.

Given the political and economic relevance in the region, the government of Brazil should consider leading and actively supporting LAC efforts on cross-border service delivery. The effort and commitment of the Brazilian government would be determinant for the success of such a regional policy priority. The country’s experience in developing interoperability across different federation levels – federal, states, municipalities – could be leveraged to tackle the challenges of connecting different systems for cross-border service delivery. Brazil’s determinant role in the Mercosul context, as well as the active role it played in the approval of the Digital Agenda Group, should also be considered. Brazil has already developed some of the critical digital government key enablers (or they are about to be implemented), such as an interoperability framework, digital identity, open source. These key enablers might be leveraged for improved co-operation in the region.

The development of cross-border services is a medium- to long-term challenge. It requires strong political will as well as significant human and financial resources able to take the necessary actions – definition of services, testing and monitoring, alignment of national frameworks – towards final cross-border services delivery. The adoption of this challenge by the LAC countries would require the governments to recognise that it is not a short-term objective. However, building on this challenge, the ambition of developing cross-border services could function as an important incentive for concrete co-operation, able to mobilise broad political support across the region.

Given the different levels of digital development in the countries of the region, and different priorities for investment in this area, the creation of cross-border services could involve in a first stage only a small part of the countries of the region, enabling other countries to focus on further priorities. For instance, more prepared or interested countries on specific cross-border services should be able to arrange pilots to analyse the viability of the services, the effective demand, the business case or the user experience. Other countries should be able to join this common effort later, whenever they feel prepared to.

The common agreement on services to be developed with a cross-border approach is a critical stage of this suggested multilateral co-operation. The current level of development in each one of the countries and its economic and social impact are some of the variables to be considered. In this sense, some examples of cross-border services might include:

creating a company abroad

working abroad

studying abroad

having a medical consultation abroad.

Considering all the efforts of economic integration already underway among LAC countries, the development of cross-border services in the region would represent taking co-operation on digital government to the next level, contributing to the mobilisation of the ecosystem of stakeholders towards a practical and tangible objective.

References

[30] Agência Brasil (2018), Órgãos públicos usam inteligência artificial para combater corrupção | Agência Brasil, http://agenciabrasil.ebc.com.br/geral/noticia/2018-08/orgaos-publicos-usam-inteligencia-artificial-para-combater-corrupcao (accessed on 08 October 2018).

[27] Banco Nacional do Desenvolvimento (2018), Estudo “Internet das Coisas: um plano de ação para o Brasil” - BNDES, https://www.bndes.gov.br/wps/portal/site/home/conhecimento/pesquisaedados/estudos/estudo-internet-das-coisas-iot/estudo-internet-das-coisas-um-plano-de-acao-para-o-brasil/!ut/p/z1/zVNLj9owEP4re8nReMib3iJgw5ZQRAsFckGOYxKviB1sA91_X0N3pYpqU7WHqj7Z4_F4vsfgHG9 (accessed on 08 October 2018).

[17] Casa Civil (2018), Lei n. 13.709, de 14 de Agosto de 2018 - Dispõe sobre a proteção de dados pessoais e altera a Lei nº 12.965, de 23 de abril de 2014 (Marco Civil da Internet)., http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2015-2018/2018/Lei/L13709.htm (accessed on 11 September 2018).

[3] Casa Civil (2016), Decreto 8.936, de 19 de Dezembro de 2016, Institui a Plataforma de Cidadania Digital e dispõe sobre a oferta dos serviços públicos digitais, no âmbito dos órgãos e das entidades da administração pública federal direta, autárquica e fundacional., http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2015-2018/2016/Decreto/D8936.htm (accessed on 14 September 2018).

[26] Casa Civil (2016), Decreto nº 8.789, de 29 de Junho de 2016 - Dispõe sobre o compartilhamento de bases de dados na administração pública federal., http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2015-2018/2016/Decreto/D8789.htm (accessed on 11 September 2018).

[23] Casa Civil (2016), Decreto nº 8777, de 11 de Maio de 2016, institui a Política de Dados Abertos do Poder Executivo federal., http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2015-2018/2016/Decreto/D8777.htm.

[13] Casa Civil (2014), Lei nº 12.965, de 23 de Abril de 2014, Estabelece princípios, garantias, direitos e deveres para o uso da Internet no Brasil, http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2011-2014/2014/lei/l12965.htm (accessed on 14 September 2018).

[14] Casa Civil (2011), Lei nº 12.527, de 18 de Novembro de 2011, Regula o acesso a informações, http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2011-2014/2011/lei/l12527.htm (accessed on 14 September 2018).

[10] Comitê Gestor da Internet no Brasil (2016), TIC DOMICÍLIOS Survey on the Use of Information and Communication Technologies in Brazilian Households, https://cgi.br/media/docs/publicacoes/2/TIC_DOM_2016_LivroEletronico.pdf (accessed on 03 September 2018).

[28] Convergência Digital (2018), CADE adota inteligência artificial para agilizar combate aos cartéis - Convergência Digital - Inovação, http://www.convergenciadigital.com.br/cgi/cgilua.exe/sys/start.htm?UserActiveTemplate=site&infoid=48613&sid=3 (accessed on 08 October 2018).

[9] Government of Brazil (2018), Estratégia Brasileira para a Transformação Digital E-Digital, Government of Brazil, Brasília, http://www.mctic.gov.br/mctic/export/sites/institucional/estrategiadigital.pdf.

[29] Government of Brazil (2018), Portal de Serviços, https://www.servicos.gov.br/ (accessed on 08 October 2018).

[32] MERCOSUL (2017), Acordos no MERCOSUL, http://www.mercosur.int/innovaportal/v/8586/12/innova.front/acordos-no-mercosul (accessed on 08 October 2018).

[15] Michener, G., E. Contreras and I. Niskier (2018), “From opacity to transparency? Evaluating access to information in Brazil five years later”, Revista de administração pública, Vol. 52/4, http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0034-761220170289.

[6] Mickoleit, A. (2014), “Social Media Use by Governments: A Policy Primer to Discuss Trends, Identify Policy Opportunities and Guide Decision Makers”, OECD Working Papers on Public Governance, No. 26, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5jxrcmghmk0s-en.

[5] Ministério do Planejamento, D. (2018), SETIC — Secretaria de Tecnologia da Informação e Comunicação, http://www.planejamento.gov.br/acesso-a-informacao/institucional/unidades/setic (accessed on 12 July 2018).

[24] OECD (2018), “A data-driven public sector for sustainable and inclusive governance”.

[7] OECD (2018), Digital Government Survey of Brazil, public sector organisations version.

[21] OECD (2018), Open Government Data in Mexico: The Way Forward, OECD Digital Government Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264297944-en.

[18] OECD (2018), Open Government Data Report: Enhancing Policy Maturity for Sustainable Impact, OECD Digital Government Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264305847-en.

[33] OECD (2018), Promoting the Digital Transformation of the African Portuguese Speaking Countries and Timor-Leste.

[16] OECD (2017), Digital Government Review of Norway: Boosting the Digital Transformation of the Public Sector, OECD Digital Government Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264279742-en.

[2] OECD (2017), “Digital Transformation of the Public Sector: Helping governments respond to the needs of networked societies”.

[11] OECD (2017), OECD Guidelines on Measuring Trust, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264278219-en.

[20] OECD (2016), Government at a Glance: Latin America and the Caribbean 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264265554-en.

[22] OECD (2016), Open Government Data Review of Mexico: Data Reuse for Public Sector Impact and Innovation, OECD Digital Government Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264259270-en.

[12] OECD (2014), Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/gov/digital-government/Recommendation-digital-government-strategies.pdf (accessed on 17 August 2018).

[4] OECD (2014), Survey on Digital Government Performance, https://qdd.oecd.org/subject.aspx?Subject=6C3F11AF-875E-4469-9C9E-AF93EE384796 (accessed on 16 July 2018).

[1] OECD (forthcoming), Creating a Citizen-Driven Environment through Good ICT Governance – The Digital Transformation of the Public Sector: Helping Governments Respond to the Needs of Networked Societies, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[25] OECD (forthcoming), Digital Government Framework, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[8] OECD/ITU (2011), M-Government: Mobile Technologies for Responsive Governments and Connected Societies, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264118706-en.

[31] Red GEALC (2018), Qué es la Red Gealc, http://www2.redgealc.org/sobre-red-gealc/que-es-la-red-gealc/ (accessed on 10 September 2018).

[19] Ubaldi, B. (2013), “Open Government Data: Towards Empirical Analysis of Open Government Data Initiatives”, OECD Working Papers on Public Governance, No. 22, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5k46bj4f03s7-en.