In line with Pillar 2 and 3 of the OECD Recommendation on Digital Government Strategies (OECD, 2014[1]), Chapter 2 analyses the governance of digital government in Romania, examining the contextual factors and institutional models that support the digital transformation of the public sector. The chapter is divided into six sections: the first section reviews the country’s overall political and administrative culture, the second section examines the socio-economic factors and technological context, the third section analyses the macro-structure and leading organisation of the public sector, and the fourth section focuses on existing co-ordination and compliance arrangements to ensure the sustainability of the digital transformation. Additionally, the chapter also discusses Romania’s digital government strategy and its relevance across the public sector.

Digital Government Review of Romania

2. Governance for digital government

Abstract

Introduction

In the face of unforeseeable risks, the importance of resilience, responsiveness and agility in government cannot be overstated in today’s world. Governments around the world have recognised the need to prioritise the strategic use of digital technologies and data to mitigate potential risks and turn challenges into opportunities. The digital transformation of the public sector has been a key driver of innovation and socio-economic growth in many countries around the world. Nevertheless, to ensure that this digital transformation is effective and sustainable, it is essential to have robust governance for digital government in place.

Effective governance is a critical factor in driving coherent and sustainable change across the public sector. It promotes an inclusive and collaborative digital ecosystem that involves all relevant stakeholders, while also driving a cultural shift from siloed thinking to a strategic systems approach. Such governance is necessary for the design and delivery of citizen-driven policies and services. Additionally, robust governance helps governments address risks and challenges associated with digital government, such as ensuring ethical use of digital technologies and data, building a digitally competent workforce, and mitigating cybersecurity threats.

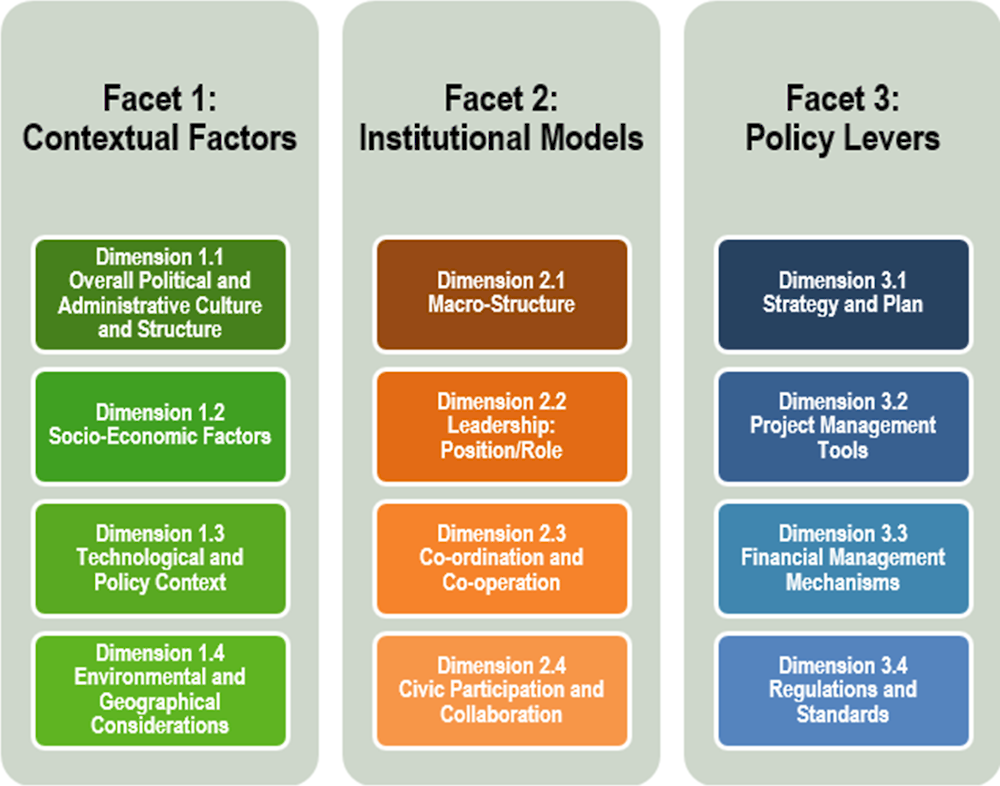

According to the OECD Digital Government Index 2019 (OECD, 2020[2]), strong governance is crucial for the development of digital government. This governance framework supports the necessary cultural shift from a siloed mindset to a strategic, systems-thinking approach, and it establishes the institutional foundations required for designing and delivering citizen-centric policies and services. The E-Leaders Handbook on the Governance of Digital Government (OECD, 2021[3]), which is based on the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies (OECD, 2014[1]), provides a framework that enables governments to improve their digital governance by asking key policy questions. The handbook draws on the experiences of OECD member and non-member countries to assist policymakers in developing and implementing digital government strategies, resulting in a mature and digitally enabled state (Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1. The OECD Framework on the Governance of Digital Government

Source: OECD, (2021[3]), The E-Leaders Handbook on the Governance of Digital Government, https://doi.org/10.1787/ac7f2531-en

The OECD Framework on the Governance of Digital Government consists of three crucial components (applied to the Romanian context and analysed in Chapter 2 and 3):

Contextual Factors which refer to country-specific characteristics such as political, administrative, socio-economic, technological, policy and geographical factors that should be considered when designing policies for an inclusive and sustainable digital transformation of the public sector.

Institutional Models which consist of various institutional structures, approaches, and mechanisms in the public sector and digital ecosystem that help guide the design and implementation of digital government policies in a sustainable manner.

Policy Levers which enable governments to ensure a coherent and effective digital transformation of the public sector.

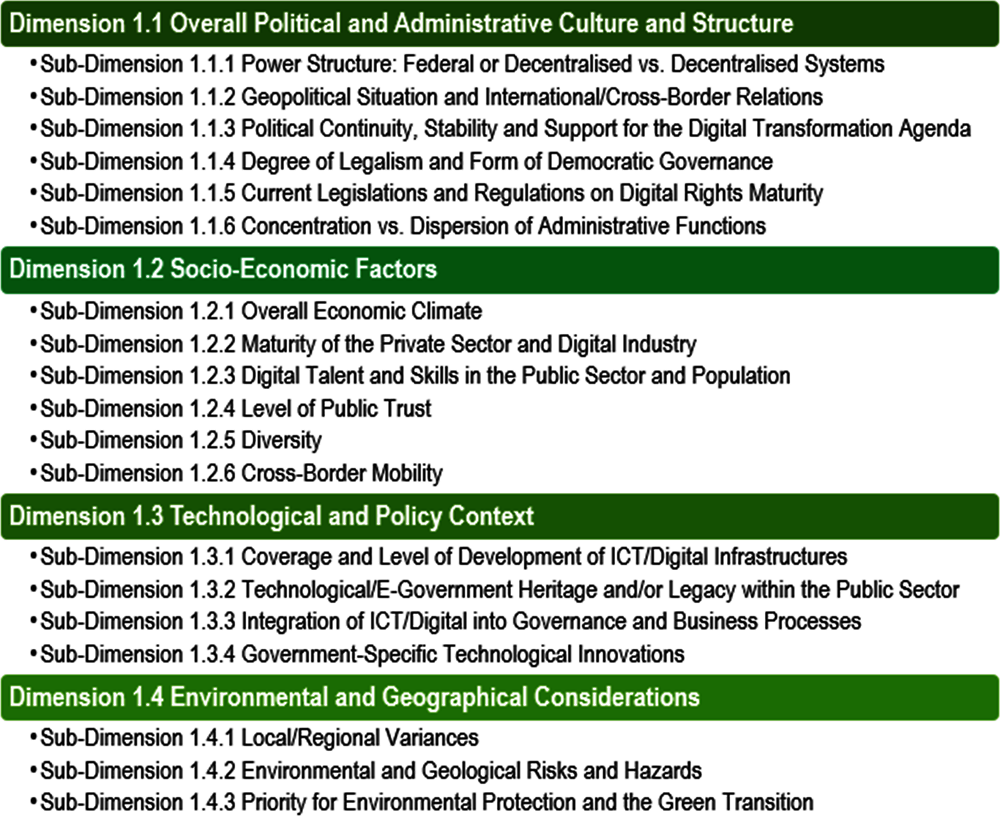

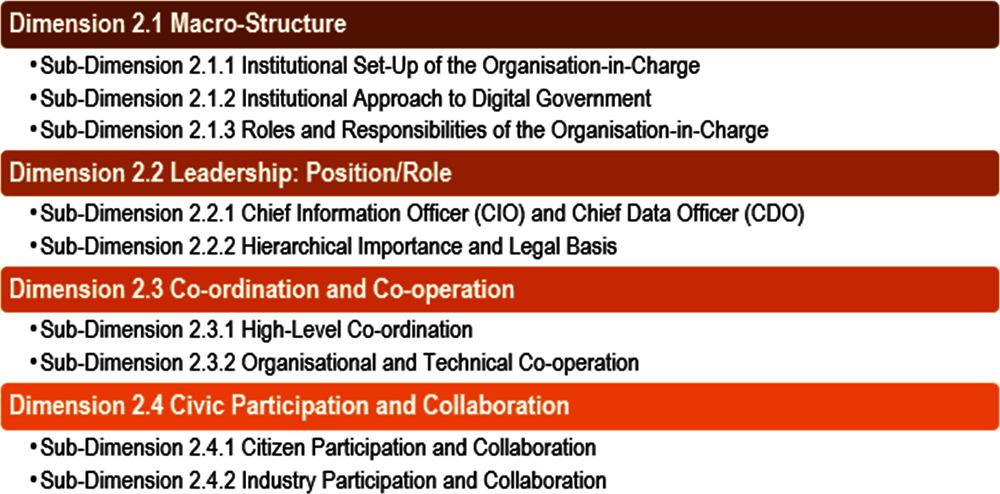

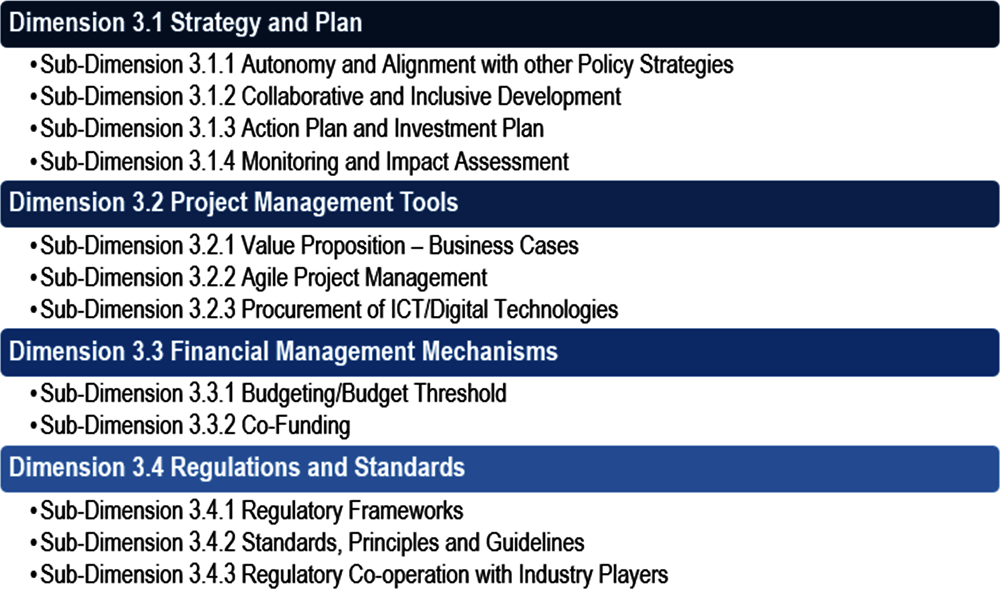

This chapter will examine the governance of Romania’s digital government in five main sections, according to the three facets of the Governance Framework (see Figure 2.2, Figure 2.3 and Figure 2.4). The initial part analyses the overall political and administrative culture, encompassing aspects like the country's power structure, political stability, and support for the digital transformation agenda. The subsequent section delves into socio-economic factors and the technological landscape of the country, encompassing elements such as digitalisation levels among the population and the overall maturity of digital government. The third section evaluates the macro-structure and the leading organisation within Romania's public sector. Following that, the fourth section concentrates on existing co-ordination and collaboration mechanisms that ensure coherence and sustainability in the digital transformation of the public sector. The final part examines Romania's digital government strategy and its significance throughout the public sector.

Figure 2.2. The OECD Framework on the Governance of Digital Government - Contextual Factors

Source: OECD, (2021[3]), The E-Leaders Handbook on the Governance of Digital Government, https://doi.org/10.1787/ac7f2531-en

Figure 2.3. The OECD Framework on the Governance of Digital Government - Institutional Models

Source: (OECD, 2021[3]), The E-Leaders Handbook on the Governance of Digital Government, https://doi.org/10.1787/ac7f2531-en

Figure 2.4. The OECD Framework on the Governance of Digital Government – Policy levers

Source: OECD, (2021[3]), E-Leaders Handbook on the Governance of Digital Government, https://doi.org/10.1787/ac7f2531-en

Overall political and administrative culture

The political and administrative culture of a country plays a significant role in shaping how digital government is governed. Governments need to consider these unique characteristics when developing a governance framework that aligns with their specific national context. These characteristics bring both opportunities and challenges for governments when formulating and executing national strategies for digital government.

Romania is a constitutional republic with a democratic, multiparty parliamentary system with a resident population of approximately 19 million (National Institute of Statistics, 2022[4]). Romania follows a semi-presidential model where power is shared between the President, who serves as the head of state, and the Prime Minister, who is the head of government. The legislative branch consists of the Parliament, which is a bicameral institution comprising the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies.

According to the Constitution, Romania is a unitary state with a two-tier system of subnational governments. It is administratively divided into communes, towns and counties. With the enactment of the 2006 decentralisation law, Romania has taken significant actions towards administrative and fiscal decentralisation. Nevertheless, the government remains centralised in terms of fiscal control, and the central ministries and agencies still hold de facto power over subnational governments, despite them having responsibilities based on the decentralisation principles. As the extent of local decision-making autonomy is contingent upon the financial and human resource capabilities, many smaller administrative-territorial units face financial constraints due to ongoing expenses and staffing costs. The lack of unified co-ordination has created barriers in fully realising this long-standing process of decentralisation (European Commission, 2021[5]).

In addition to the decentralisation effort, wide administrative reforms have been implemented to increase the effectiveness of the country’s public administration. Nevertheless, the progress has been slow. According to the Worldwide Governance Indicators, Romania’s public administration is substantially below the average effectiveness of its 27 European peers ( (World Bank, 2021[6]). The frequent changes in the organisational structure and leadership positions have impeded institutional stability, the development of administrative capabilities, and sustainability of government initiatives, thus the expected outcome of the long-term reform agenda. In Romania, since the introduction of “emergency ordinances” in 2005, the government has frequently relied on them for policy- and decision-making to bypass the formalities and delays. This practice contributed to the culture of implementing policies without a solid analytical foundation, inclusive consultations and impact assessments. In addition, the excessive fragmentation of responsibilities and resources remains a significant obstacle to the effective design and delivery of government services (European Commission, 2022[7]). During the review process for the Digital Government Review of Romania, a few interviewees have echoed this assessment based on their ongoing challenges.

In general, Romania’s current political and administrative culture poses some significant challenges for the government to drive the digital transformation of the public sector in a coherent and sustainable manner. The slow administrative reform including the administrative and fiscal decentralisation of the subnational governments has created barriers for the government to create consensus, alignment and co-ordination to develop digital government maturity across the public sector. Frequent changes in organisational structure have weakened the digital leadership in the government to co-ordinate and align policies and actions on digital government across the country. In addition, high reliance on emergency ordinances have led to policies and decisions with minimal impact. The Romanian recovery and resilience plan (RRP) includes ambitious plans and investments to address these challenges. It is recommended to assess and monitor the implementation of the wider public administration reform agenda to better address its potential impacts on building the governance needed to drive the digital transformation across the public sector.

Socio-economic factors and technological context

When governing the digital transformation of the public sector, a comprehensive understanding of the socio-economic and technological context would result in further contribution to economic and social development. Effective governance should consider factors such as the general economic conditions, the existing level of digital advancement within society, the demographic makeup of the population, and the country's historical, current, and future technological advancements. By taking these factors into account, governments can better align digital transformation efforts with the specific needs and opportunities of the country.

Over the past two decades, Romania has made remarkable progress in enhancing its economic performance and prosperity. In 2022, Romania experienced robust economic growth of 4.8 percent, driven by strong private consumption and increased investment. However, the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine have further exposed its structural vulnerabilities such as persistent poverty and disparities in economic opportunities, substantial gender gaps in workforce participation and employment, and significant institutional constraints that hinder the efficient use of resources (World Bank, 2023[8]). The 2022 Country Report of Romania of the European Commission also highlights high regional disparities as a key vulnerability for its society and economy. Gaps between the capital and the rest of regions on labour productivity, investment and employment have caused regional disparities to rise (European Commission, 2022[7]).

Romania’s population has declined over the recent decade, from 21.6 million in 2002 to 19.0 million in 2022. The second biggest cause, following the high mortality rate, of the population decline is the phenomenon of emigration. In 2021, the balance of international migration was negative with marking 16,000 migrants more than the number of immigrants. Romania has a large population who resides abroad. In the recent data published by the Romanian government, as of 2021, approximately 5.7 million Romanians reside abroad (The Government of Romania, 2022[9]). The population has also aged, with the population aged 0-14 remained unchanged at 15.8%, whereas the proportion of individuals aged 65 and older rose to 19.5% (National Institute of Statistics, 2022[4]).

The Romanian government has taken several steps to strengthen its telecommunication infrastructure. The country is the sixth in the fastest-growing countries for fixed broadband. Since 2019, Romania’s National Authority for Management and Regulation in Communications (ANCOM) has operated a mobile unit to increase the internet connectivity across the nation. Nevertheless, Romania still faces a challenge of narrowing the digital gap between the capital and rural areas (International Telecommunication Union, 2022[10]).

At the European level, Romania is still lagging in many aspects compared to its peers. According to the European Commission’s Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) 2022, Romania ranked 27th of the 27 EU member states, with its relative annual growth rate lower than the other 26 countries. Romania underperformed in all four dimensions: Human Capital, Connectivity, Integration of Digital Technology and Digital Public Services. Specially, the government faces considerable difficulties in delivering digital services. The DESI indicators show that both the availability of digital public services for citizens and businesses are quite low compared to the EU average. Moreover, the level of digital interaction between public authorities and the general public remains very low, with only 17% of internet users accessing services digitally (see Table 2.1) (European Commission, 2022[11]). The findings of the UN e-Government Survey 2022 align with the DESI results. Romania ranked 57th among 193 countries, scoring under the regional average on all indices. While the country scored above the sub-regional average on the Telecommunication Infrastructure Index, it was placed well under sub-regional average on the Online Services Index and Human Capital Index (see Table 2.2) (United Nations, 2022[12]).

Table 2.1. Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) 2022: Romania’s performance

|

Human Capital (Digital Skills) |

Connectivity |

Integration of Digital Technology |

Digital Public Services |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Avg. of 27 EU countries |

45.7 |

59.9 |

36.1 |

67.3 |

|

Romania |

30.9 (27) |

55.2 (15) |

15.2 (27) |

21 (27) |

Source: European Commission, (2022[11]), Digital Economy and Society Index 2022 Romania country profile, https://ec.europa.eu/newsroom/dae/redirection/document/88717

Table 2.2. UN E-Government Survey 2022: Romania’s performance

|

Rank |

E-Government Development Index (EGDI) |

Telecommunication Infrastructure Index (TII) |

Online Services Index (OSI) |

Human Capital Index (HCI) |

E-Participation Index (EPI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Romania |

57 |

0.76190 |

0.79540 |

0.68140 |

0.80900 |

0.62500 |

Source: United Nations, (2022[12]) UN E-Government Survey 2022, https://desapublications.un.org/sites/default/files/publications/2022-09/Web%20version%20E-Government%202022.pdf

The prospect seems brighter for the private sector, especially the start-up community in the country. Romania’s start-up landscape is gaining recognition as one of the most dynamic innovation hubs in Central and Eastern Europe. Fuelled by a rapidly growing IT workforce, the country shows great potential for start-up success. The COVID-19 pandemic has acted as a catalyst, driving a heightened focus on digital technologies among business leaders and investors, creating a favourable environment for the Romanian start-ups in the international arena.

Romania faces several challenges in its socio-economic context for effective digital transformation of the public sector, such as regional disparities, gender gaps, declining population and digital divide. Addressing these challenges would provide Romania a solid foundation for the governance for the digital government. The government can consider developing a whole-of-government strategical initiative to support raising awareness on digital inclusion, upskilling of digital competences and targeted training programmes for certain demographics. It is highly recommended that the government gives a special attention on rural areas to close the gap with the capital. The consolidated approach would help the government better leverage the investments in the RRP allocated to “Increasing digital competence for public service and digital education throughout like for citizens”. In regard to the technological context, although Romania has made good progress on the telecommunication infrastructure and connectivity, several challenges remain in transforming towards a mature digital government. Especially, the government needs to concentrate its efforts in building digital competencies of the public sector, embedding a digital mindset across the public sector. This would enable the public sector to appreciate the value of designing and delivering services that put users’ needs at the core. There is also an opportunity to tap into the potential of the private sector, including the local start-ups, to design and deliver innovative and agile services to users through fostering a healthy govtech ecosystem.

Macro-structure and leading public sector organisation

A sustainable and effective digital transformation in the public sector relies on a well-defined institutional model. This enables governments to adopt a comprehensive and co-ordinated approach to digital transformation. The formal and informal institutional arrangements play a crucial role in establishing a strategic vision, providing necessary leadership, and fostering co-ordination and collaboration within the digital government ecosystem. Additionally, these arrangements help governments clarify and systematise institutional and personal leadership roles (e.g. Chief Information Officer, Chief Data Officer) (OECD, 2021[3]).

To fully advance towards digital government maturity, it is essential to have a designated "organisation-in-charge" responsible for leading and co-ordinating the digital transformation agenda across the public sector. This organisation should have clearly defined roles and responsibilities that are recognized and agreed upon by all key stakeholders of the public sector. Considering the different contextual factors, including the country's political and institutional culture, this leading organisation needs to be strategically positioned within the government and equipped with adequate financial and human resources. It should have the authority to garner political support, integrate a digital government strategy into a broader national reform agenda, and gain legitimacy within the public sector (OECD, 2021[3]).

The organisation-in-charge should have decision-making, co-ordination, and advisory responsibilities. It needs to be entrusted to make critical decisions and be accountable for them across the government. Furthermore, it should co-ordinate with other public sector institutions, ensuring alignment between sectoral digital government projects and the national digital government strategy. Lastly, it should provide guidance and advice to other public sector institutions on the development, implementation, and monitoring of digital government strategies (see Box 2.1) (OECD, 2021[3]).

Box 2.1. Roles and Responsibilities of the Organisation-in-Charge

Coordination responsibilities include the horizontal and vertical co-ordination of the development of the national digital government strategy, with other public sector organisations on its implementation and with local governments to align the development of digital government projects with the objectives of the national digital government strategy.

Advisory responsibilities include the provision of counsel and guidance on the development of the national digital government strategy; the monitoring of its implementation; the support of the development and implementation of digital government strategies at an organisational level; the development of technical guidelines for ICT/digital architecture; and horizontal co-ordination among public sector organisations.

Decision-making responsibilities include the powers and duties to make important decisions with considerable accountability across the government, including the prioritisation and approval of ICT/digital government project investments; ex-ante revisions, evaluation and external reviews of ICT/digital government projects; provision of financial support for the development and implementation of ICT/digital government projects.

Source: (OECD, 2021[3]), The E-Leaders Handbook on the Governance of Digital Government, https://doi.org/10.1787/ac7f2531-en

According to the OECD Digital Government Index (DGI) 2019, all 33 participating countries have designated a central-level organisation to lead and co-ordinate decisions regarding digital government. However, the specific institutional structures vary from country to country. Some position this leading organisation within the Centre of Government (CoG) (e.g., Chile, France, and the United Kingdom), while others place it within a specific line ministry (e.g., Estonia, Greece, and Luxembourg) or under a co-ordinating ministry such as finance or public administration (e.g., Denmark, Korea, Portugal, and Sweden) (see Box 2.2).

Box 2.2. Digital Government leadership – Examples from the OECD Member countries

La direction interministérielle du numérique (DINUM) of France

Created in October 2019, DINUM is the inter-ministerial digital directorate that in charge of the digital transformation of the French public sector. It is placed under the authority of the Minister of Transformation and the Public Service under the Prime Minister’s Office. The directorate supports the line ministries in their digital transformation and develops shared services and resources such as the national inter-ministerial network (RIE), FranceConnect (digital identity service), data.gouv.fr or api.gouv.fr. DINUM also leads the TECH.GOUV program to accelerate digital transformation of the public services in coordination with all line ministries.

Note: This information has been translated from French to English.

Source: (La direction interministérielle du numérique (DINUM), 2023[13]), https://www.numerique.gouv.fr/dinum/

The Ministry for Digitalisation of Luxembourg

The Ministry for Digitalisation was established in December 2018 with a strong political mandate under the government led by Prime Minister Xavier Bettel. It is currently headed by the prime minister. As a line ministry, the MDIGI’s role encompasses promoting and implementing ICT and digital strategies within the public sector and at the national level. This is done through collaboration and consultation with other ministries and government agencies. For instance, the MDIGI works closely with the Ministry of the Economy and the Department of Media, Connectivity and Digital Policy (SMC) of the Ministry of State (ME) on various initiatives such as Digital Luxembourg. Together, they oversee activities related to monitoring and promoting the ICT sector, developing digital infrastructure, and formulating strategies for emerging technologies like AI and 5G.

In addition to these shared responsibilities, the MDIGI has exclusive jurisdiction over strategic tasks specifically related to the digital advancement of the public sector. This includes areas such as administrative procedures, digital inclusion, information exchange, high-level coordination, and the Government IT Centre (CTIE).

Source: (OECD, 2022[14]), Digital Government Review of Luxembourg, https://doi.org/10.1787/b623803d-en

The Administrative Modernisation Agency of Portugal

Portugal's digital transformation agency, the Administrative Modernisation Agency (AMA), was created in 2007 and sits within the Presidency of the Council of Ministers. It exercises the powers of the Ministry of State Modernisation and Public Administration in modernisation, administrative simplification and digital government, and is under the supervision of the Secretary of State for Innovation and Administrative Modernisation. The agency has a top role in the development, promotion and support of the public administration in several technological fields and is in continuous contact with focal points at institutions relevant for the implementation of digital government projects. It is responsible for the approval of ICT and digital projects over EUR 10,000 and chairs the Council for ICT in the public administration.

Source: OECD, (2021[3]) The E-Leaders Handbook on the Governance of Digital Government, https://doi.org/10.1787/ac7f2531-en

Authority for Digitisation of Romania

In recent years, Romania has experienced challenges in maintaining a consistent and sustainable approach to the digital transformation within the public sector due to frequent changes in government decisions and practices. The responsibility for leading the digital transformation efforts has shifted among various government organisations, leading to a lack of continuity and weakening the overall agenda for digital government. This fluidity in decision-making has hindered the progress and effectiveness of digital initiatives.

Currently, the Authority for Digitisation of Romania (ADR) under the Ministry of Research, Innovation and Digitisation (MCID) has taken up the role of the organisation-in-charge for digital government. Pursuant to the government decision, the ADR has a mandate to strategically plan and ensure the development and implementation of policies of digital transformation across the public sector (Box 2.3) in close collaboration with the General Secretariat of the Government (GSG).

Box 2.3. Objectives and functions of the Authority for Digitisation of Romania

Objectives

1. Contribution to the digital transformation of the Romanian economy and society.

2. Achievement of electronic government in public administration through standardization, technical and semantic interoperability of information systems, and adherence to the principles of the Tallinn Ministerial Declaration on electronic government.

3. Support for the fulfillment of Romania's objectives under the financial assistance programs of the European Union in its area of competence.

Functions

1. Strategy: the ADR strategically plans and ensures the development and implementation of policies related to digital transformation and the information society.

2. Regulatory: the ADR regulates and participates in the development of the normative and institutional framework for digital transformation, including ensuring interoperability of IT systems in public institutions.

3. Approval: the ADR has an approval function within its jurisdiction.

4. Representation: the ADR represents the government in national, regional, European, and international bodies and organizations, acting as a state authority in its field of activity.

5. State authority: the ADR monitors and ensures compliance with regulations within its area of competence.

6. Administration and management: the ADR handles administrative and managerial tasks.

7. Promotion, coordination, monitoring, control, and evaluation: the ADR promotes, coordinates, monitors, controls, and evaluates the implementation of policies in its field, including the national interoperability framework.

8. Communication: the ADR facilitates communication between public sector structures, private sector, and civil society.

9. Implementation and management of projects: the ADR implements and manages projects funded from European and national sources.

10. Intermediate body: the ADR acts as an intermediate body for the implementation of measures under specific programs, such as the Sectoral Operational Program for "Increasing Economic Competitiveness" and the Operational Program "Competitiveness."

Source: (Authority for Digitisation of Romania, 2023[15]), Decision regarding the organisation and operation of the Authority for Digitisation of Romania

The ADR was created in 2020 with the aim to accelerate the country’s digital transformation and promote the development of the information society. Its primary role has been co-ordinating and managing information systems that facilitate the provision of e-government services such as the eGovernment Portal and the Electronic System for Public Procurement. Another significant task of the ADR is streamlining administrative procedures for service providers and achieving interoperability at both national and European levels.

As a relatively new organisation, the ADR struggles to gain legitimacy and authority from public sector institutions with little interest from the highest leadership. Despite its mandate set in the government decision, its current roles and responsibilities are primarily focused on providing technical support to other government entities with their digital initiatives, rather than being seen as the leading organisation driving transformative changes across the public sector. Consequently, during the fact-finding interviews for this review, many institutions perceived the ADR as more of a supporting institution rather than a central driving force for digital government.

The OECD peer review team also found that the ADR lacks many aspects of the decision-making and co-ordination roles and responsibilities. The ADR has insufficient power to create horizontal co-ordination with the public sector institutions and alignment with the subnational governments. This has resulted in fragmented efforts and duplication of initiatives, as well as a disconnect among the national, institutional and subnational priorities. In addition, the ADR’s limited decision-making power across the government has contributed to weakened oversight and accountability, potentially leading to the misallocation of resources and the persistence of underperforming initiatives.

Romania needs to establish robust governance for digital government to drive the digital transformation across the public sector and to converge towards its European peers. The foremost challenge would be empowering the organisation-in-charge to have the strategic leadership and co-ordination of the digital government agenda. In this regard, it is highly recommended that the government consider positioning the ADR within the GSG where it can receive stronger political support and gain legitimacy to set a shared whole-of-government vision. In addition, this would create more synergies on the cross-cutting policy areas such as open government and de-bureaucratisation, which are under the responsibilities of the GSG.

Additionally, as the ADR takes the lead on the National Interoperability Law, there is a valuable opportunity for it to become a digital leader and strategic partner to the Romanian public sector institutions. Collaborating with the GSG, the ADR needs to establish the holistic vision for digital government supported by public institutions. This vision can be accompanied by a central digital government strategy that defines clear objectives, roles, and responsibilities for key stakeholders.

Co-ordination and co-operation

Effective co-ordination and collaboration are vital for achieving coherency, consistency, and effectiveness in the digital transformation of the public sector. By adopting a holistic approach and moving away from siloed thinking within individual institutions, governments can ensure sustainable impact on society. All stakeholders must work together, setting and agreeing on common objectives and action plans, in order to fully harness the benefits of digital transformation. A collaborative and cooperative culture across the public sector promotes coherent policy design, development, implementation, and monitoring, while preventing potential policy gaps and fostering an inclusive policy ecosystem. Furthermore, it facilitates the exchange of knowledge, experience, and lessons learned, thereby encouraging innovative practices in the public sector.

The OECD Framework on the governance of digital government, aligned with the second pillar of the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies, identifies co-ordination and co-operation as key dimensions in building sound governance for digital government (OECD, 2014[1]) (OECD, 2021[3]). The framework examines further into two layers of co-ordination: High-Level Co-ordination, which emphasizes institutional co-ordination at a high political and administrative level, and Organisational and Technical Co-operation, which focuses on co-operation at a more technical level.

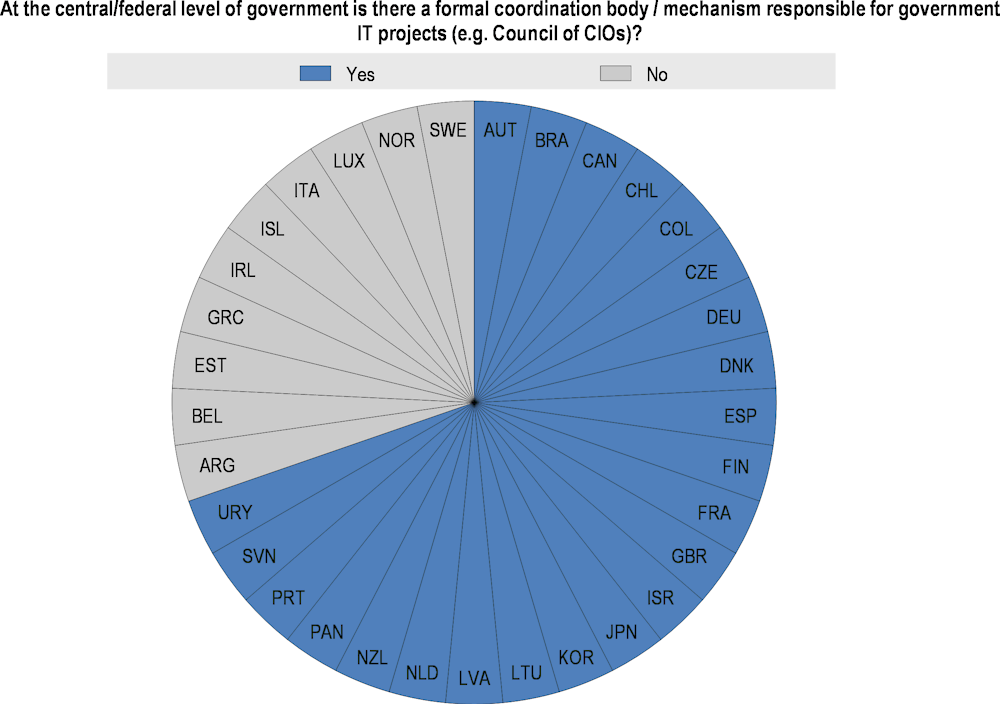

The OECD Digital Government Index 2019 (DGI) emphasises the significance of establishing a digital government co-ordination unit within institutional models. Such a unit ensures leadership, co-ordination, necessary resources, and legitimacy to translate policies into actionable and tangible public services (OECD, 2020[2]). According to the DGI 2019, the majority of top-performing countries, accounting for nearly 70%, reported having a formal co-ordinating body or mechanism responsible for government IT projects, such as a Council of CIOs (Chief Information Officers) (see Figure 2.5).

Figure 2.5. Existence of a public sector organisation leading and co-ordinating digital government in OECD countries

Note: The OECD countries that did not take part in the Digital Government Index are: Australia, Hungary, Mexico, Poland, Slovakia, Switzerland, Türkiye and the United States. A total of 29 OECD countries and 19 European Union countries participated in the Digital Government Index.

Source: OECD, (2020[2]), Digital Government Index: 2019 results, Question 59 “Is there a public sector organisation (e.g. Division, Unit, Agency) responsible for leading and co-ordinating decisions on digital government at the central /federal level of government?”, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/4de9f5bb-en.

In Romania, the Committee for e-governance and red tape reduction (CERB) co-ordinates the implementation of digital transformation of the public sector with the support from the GSG. The Committee led by the prime minister is composed of high-level representatives from 27 public institutions. The Committee is mandated to ensure coherence in the implementation, co-ordination, monitoring and evaluation of “e-government” policies; to facilitate inter-ministerial co-ordination for implementing, administering and operating electronic public services; and to provide a compliance framework for common technical standards and regulations in this domain. The Committee meets every six months to discuss the agenda items prepared by the GSG based on proposals from the members. The Committee is expected to report periodically to the prime minister on its activities and progress.

The CTE, led by the president of the ADR, serves as a technical committee that offers support in the development and monitoring of the national policy for digital government transformation. Established in 2002, the primary objective of the CTE is to ensure information system interoperability and eliminate duplication of funding and functional overlaps across projects. This technical committee reviews the technical aspects of ICT/digital project proposals submitted by central government institutions, providing recommendations for approval to the higher committee.

Based on the interviews conducted by the OECD peer review team, it is evident that the two committees, namely the Committee for e-governance and red tape reduction and the CTE are widely acknowledged by almost all public sector institutions. Nevertheless, despite their high visibility, doubts regarding their effectiveness persist among many institutions, especially for the Committee for e-governance and red tape reduction. Multiple interviewees expressed concerns that the inter-ministerial co-ordination mechanism has not been effective in facilitating communication and co-ordination among various stakeholders. This has led to a lack of alignment and coherency which are crucial for the successful digital transformation of the public sector. Consequently, the diminished influence of the committee has resulted in disengaged participation from their members.

Overall, Romania has laid a good foundation for co-ordination and co-operation in digital transformation through establishing the high-level inter-ministerial committee and the technical committee. To fully leverage the potential of this co-ordination mechanism, it would be valuable for the government to take concrete measures that solidify co-ordination processes, ensuring coherence and sustainability of the digital transformation agenda across the public sector. It would be vital for fostering a more inclusive and impactful digital government agenda.

The Romanian government should prioritise fostering a collaborative mindset among stakeholders by facilitating collaboration and communication among practitioners at a technical level. This approach can promote knowledge sharing, institutional learning, and build trust among organisations. By breaking down silos and encouraging information exchange, barriers to achieving a coherent and sustainable implementation of the digital government agenda can be overcome. To support this, it is recommended to establish platforms that enable effective collaboration and sharing of best practices across the public sector (Box 2.4). In addition, the ADR can consider strengthening its monitoring and impact assessment functions to ensure the effective implementation of the digital government strategy. By actively tracking and measuring the outcomes and impact of digital initiatives, the ADR can provide valuable insights and adjustments to enhance their effectiveness.

Box 2.4. Communities of practice of the OECD countries

Digital.gov Communities of Practice of the United States of America

The U.S. General Services Administration operates communities of practice across government for practitioners to collaborate and share resources to build better digital experience for users. There are seven official and 21 unofficial communities on thematic areas from user experience, the use of plain language to artificial intelligence.

Source: The U.S. General Services Administration, (The U.S. General Services Administration, 2023[16]), Communities of practice

Communities of practice in the Australian government

Organised by the Digital Transformation Agency, communities of practices bring together practitioners working in the same field to share ideas, share experiences and solve problems. Currently, there are ten communities active.

Source: The Australian Government (Digital Transformation Agency of Australia, 2023[17]), Communities of practice

During the review process, the OECD peer review team found limited evidence of effective co-ordination and collaboration between the central and subnational government institutions, resulting in missed opportunities for collaboration (OECD, 2022[18]). To address this, the government can enhance its co-ordination efforts by implementing structured and regular co-ordination meetings with subnational digital leaders. This can be achieved through collaboration between the ADR and the Ministry of Internal Affairs, which provides shared services, tools for the subnational governments, and leads the county council meetings. The regular meetings would enable Romania to steer a more cohesive and inclusive digital transformation agenda, extending its impact to the subnational level. These meetings would also provide a platform to identify the specific needs of subnational governments and foster collaboration among them. For instance, taking inspiration from Korea's Framework Act on Intelligent Informatization, which established a co-ordination council composed of central administrative bodies and local governments, Romania can establish a similar mechanism for effective co-ordination and collaboration (see Box 2.5).

Box 2.5. Korea’s Consultative Council of Intelligent Informatization Officers

Framework Act on Intelligent Informatization

Article 9 (Consultative Council of Intelligent Informatization Officers)

(1) The heads of central administrative agencies and the heads of local governments (referring to the Special Metropolitan City Mayor, Metropolitan City Mayors, Special Self-Governing City Mayors, Do Governors, Special Self-Governing Province Governor) shall establish and operate the Consultative Council of Intelligent Informatization Officers (hereafter in this Article referred to as the “Consultative Council”) comprised of the Minister of Science and ICT, the Minister of the Interior and Safety and intelligent informatization officers for such purposes as efficiently promoting policy measures for the intelligent information society and intelligent informatization projects, exchanging necessary information, and consulting on relevant policy measures.

(2) The Consultative Council shall be co-chaired by the Minister of Science and ICT and the Minister of the Interior and Safety.

(3) Matters necessary concerning consultation and operation of the Consultative Council shall be prescribed by Presidential Decree.

Source: Government of the Republic of Korea, (2020[19]), Framework Act on Intelligent Informatization – Chapter II

Strategy and plan

To achieve a comprehensive and sustainable digital government transformation across all levels of government, it is crucial to establish a well-defined digital government strategy. This strategy should encompass a strategic vision, clear objectives, and priorities, accompanied by a structured framework and detailed action plans for implementation and monitoring. Furthermore, the strategy should align with broader national agendas or policy priorities (e.g. administrative reform, sustainable development, climate change and environment, education, science and technology). It should also reflect the specific needs and priorities of different sectors of the government.

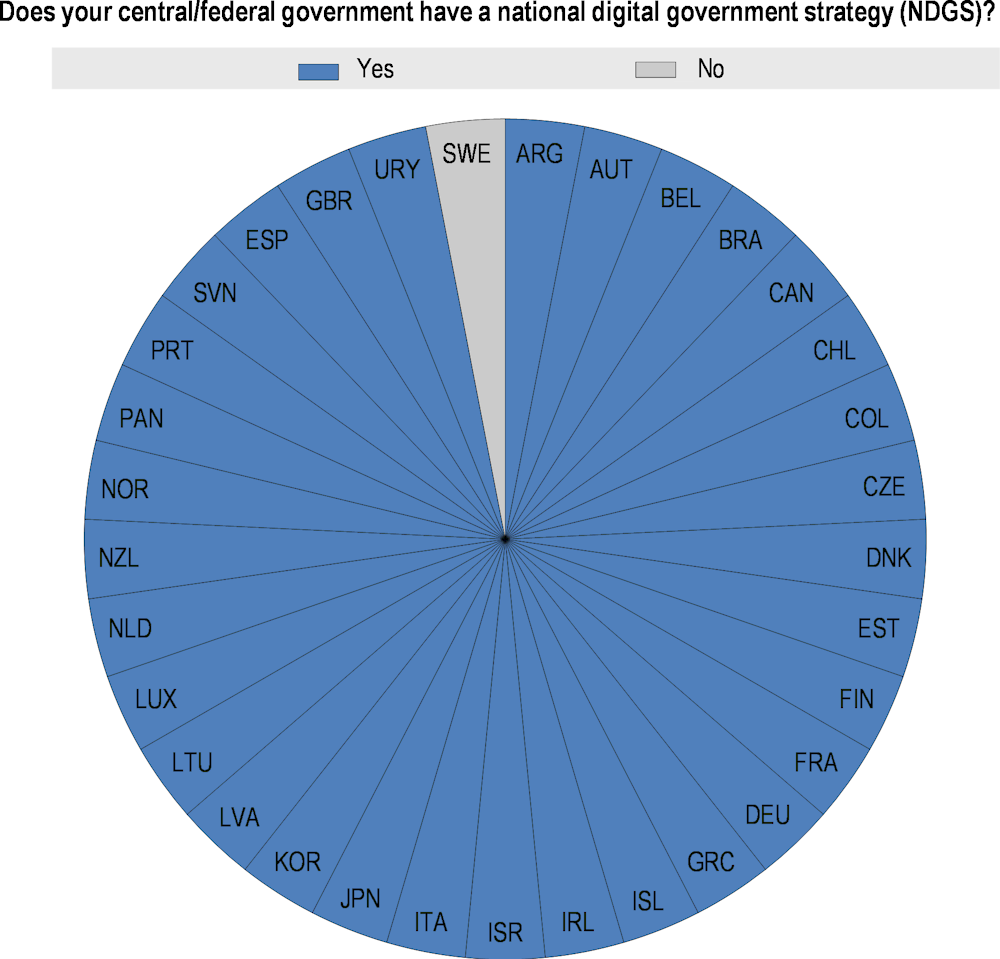

The OECD Digital Government Index 2019 revealed that nearly all OECD member countries have recognised the significance of a digital government strategy in driving public sector digital transformation (Figure 2.6). While the specific names and formats of these strategies may vary among governments, they serve as guiding documents that outline policy objectives for digital government initiatives. Some governments choose to present their strategies as stand-alone documents, while others integrate them into broader national agendas. The key takeaway is that OECD countries acknowledge the importance of having a well-defined strategy to facilitate progress towards achieving digital government maturity.

Figure 2.6. Existence of a national digital government strategy in OECD countries

Note: The OECD countries that did not take part in the Digital Government Index are: Australia, Hungary, Mexico, Poland, Slovakia, Switzerland, Türkiye and the United States. A total of 29 OECD countries and 19 European Union countries participated in the Digital Government Index.

Source: OECD, (2020[2]), Digital Government Index: 2019 results, Question 1 “Does your central/federal government have a national digital government strategy?”, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/4de9f5bb-en.

In 2020, the GSG and the ADR developed a public policy proposal in the field of e-government, the Public Policy in the field of eGovernment. Adopted by the government in June 2021, the purpose of the policy is to increase the number of e-government services and enhance the capacity of Romanian public institutions in developing and implementing e-government services. The main issue addressed by this public policy is the limited availability of electronic services that go beyond basic interactions with citizens. This policy centres around 36 key life events that encompass significant public services affecting the lives of citizens and businesses. The document identifies the challenges that Romania faces in the provision of e-government services and lists specific actions to increase the number of electronic services and strengthen the general digital skills of public servants by 2030. It is also complemented by a plan to monitor the implementation of the public policy (Government of Romania, 2020[20]).

Funded by the European Union, the Romanian government is obliged to develop the indicators and monitor the progress on the specific activities under the Public Policy in the field of eGovernment. During the meeting of the Committee for e-governance and red tape in April 2022, the ADR presented the findings of initial monitoring of the level of digitisation of life events services outlined in the document. The organisation also shared the plan to conduct this exercise on yearly basis to track the progress of each institution (Authority for Digitization of Romania, 2022[21]).

Although the policy provides a detailed roadmap for Romania to advance towards building more e-government services for users, there are significant gaps for this strategic document to be a digital government strategy that can steer the digital transformation across the public sector. The development of a comprehensive digital government strategy requires a shared vision among all stakeholders. This vision needs to be established through an inclusive process, ensuring the participation of diverse actors and perspectives. Once the shared whole-of-government vision is set, the future digital government strategy should align with other sectoral and thematic strategies to ensure coherence and support from the wider public sector. Additionally, it is crucial to develop an accompanying long-term investment plan and detailed action plan to ensure continuity, effectiveness, and efficiency in strategy implementation. The detailed action plan needs to clearly outline objectives and responsible bodies, a timeline for expected results, and key performance indicators (KPIs), thereby strengthening implementation efforts and measuring impact. Importantly, all relevant stakeholders need be engaged in this process to ensure their vision and needs contribute to the national digital government strategy.

The absence of such digital government strategy that sets the broader strategic vision beyond e-government services and facilitate the transition from e-government to digital government is a pressing challenge in Romania. Together with the GSG, the ADR can leverage the Committee for e-governance and red tape and the CTE to establish an ambitious vision and clear priorities that are also responsive to specific institutional needs. By ensuring ongoing co-ordination after the development of the strategy, the ADR can continue to track and monitor the progress made by all relevant stakeholders. This approach would ensure that the strategy remains relevant and on track. The recommendations provided in this review can serve as supportive input for this process, as well as the involvement of public institutions in the review process, including their participation in the upcoming workshops would allow for their concerns and priorities to be heard.

References

[15] Authority for Digitisation of Romania (2023), Decision regarding the organization and operation of the Authority for Digitisation of Romania, https://www.adr.gov.ro/atributii/.

[21] Authority for Digitization of Romania (2022), Authority for Digitization of Romania, https://www.adr.gov.ro/gradul-de-digitalizare-a-statului-roman-se-afla-la-21-inca-din-anul-2020/?_gl=1*42lzr5*_up*MQ..*_ga*MTE2NzE5OTg5MC4xNjcxMDI2NDY3*_ga_5PB3SY563L*MTY3MTAyNjQ2Ni4xLjEuMTY3MTAyNjQ5NS4wLjAuMA..

[17] Digital Transformation Agency of Australia (2023), Communities of practice, https://www.dta.gov.au/help-and-advice/communities-practice (accessed on October 2023).

[7] European Commission (2022), 2022 European Semester: Country Report - Romania, European Commission, https://commission.europa.eu/document/download/cfb7b4a4-eb31-4463-a643-e4d4b3d58efc_en?filename=2022-european-semester-country-report-romania_en.pdf.

[11] European Commission (2022), Digital Economy and Society Index 2022 - Romania country profile, European Commission, https://ec.europa.eu/newsroom/dae/redirection/document/88717.

[5] European Commission (2021), Public administration and governance: Romania, European Union, https://commission.europa.eu/system/files/2021-10/romania-ht0921318enn.en_.pdf.

[20] Government of Romania (2020), eRomania Policy, Government of Romania, https://www.adr.gov.ro/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Propunere-de-politica-publica-in-domeniul-e-guvernarii-adoptata-3-iun-2021.pdf.

[19] Government of the Republic of Korea (2020), Framework Act on Intelligent Informatization, https://elaw.klri.re.kr/kor_service/lawView.do?hseq=54720&lang=ENG.

[10] International Telecommunication Union (2022), Mapping Romania’s digital expansion, https://www.itu.int/hub/2022/09/mapping-romanias-digital-expansion/ (accessed on May 2023).

[13] La direction interministérielle du numérique (DINUM) (2023), https://www.numerique.gouv.fr/dinum/.

[4] National Institute of Statistics (2022), , https://insse.ro/cms/sites/default/files/com_presa/com_pdf/poprez_ian2022e.pdf.

[14] OECD (2022), Digital Government Review of Luxembourg: Towards More Digital, Innovative and Inclusive Public Services, OECD Digital Government Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b623803d-en.

[18] OECD (2022), Digital Government Survey of Romania.

[3] OECD (2021), The E-Leaders Handbook on the Governance of Digital Government, OECD Digital Government Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/ac7f2531-en.

[2] OECD (2020), “Digital Government Index: 2019 results”, OECD Public Governance Policy Papers, No. 03, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/4de9f5bb-en.

[1] OECD (2014), Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies, OECD/LEGAL/0406, OECD, Paris, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0406.

[9] The Government of Romania (2022), National Strategy for Romanians Abroad 2023-2026, https://dprp.gov.ro/web/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Proiect-Strategia-Nationala-pentru-Romanii-de-Pretutindeni-08.12.2022.pdf#page16.

[16] The U.S. General Services Administration (2023), Digital.gov Communities of Practice, https://digital.gov/communities/ (accessed on October 2023).

[12] United Nations (2022), E-Government Survey 2022, United Nations, https://desapublications.un.org/sites/default/files/publications/2022-09/Web%20version%20E-Government%202022.pdf.

[8] World Bank (2023), The World Bank in Romania, https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/romania/overview#1.

[22] World Bank (2023), World Bank Data, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.TLF.TOTL.FE.ZS?end=2022&locations=EU-RO&start=2000 (accessed on May 2023).

[6] World Bank (2021), Worldwide Governance Indicators, https://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/Home/Reports (accessed on 2023).