This chapter provides an overview of existing public sector capacities in Romania to effectively deliver the digital transformation of the government, namely through mechanisms to manage digital government investments and the attraction, promotion and development of digital talent and skills in the Romanian public sector.

Digital Government Review of Romania

3. Public sector capabilities for government digital transformation

Abstract

Introduction

As governments go digital, specific capacities are needed to embed digital transformation into the machinery of government. Effective models and strategies to digitally transform public sectors have incorporated specific mechanisms and procedures to secure that digital government strategies deliver expected benefits, secure value for money, and promote a coherent, integrated and co-ordinated implementation. Similarly, establishing organisational conditions to attract, develop and promote digital talent and skills in the public sector is a pillar for digital government strategies to build upon existing human resource capacities and policies for a successful and effective implementation.

This chapter looks at the panorama of public sector capacities for government digital transformation in Romania, building on existing OECD frameworks that help structure and guide findings and possible areas of improvement across the Romanian public sector.

Management of digital government investments

Introduction

Governments are increasing their expenditure on digital technologies to support the digitalisation of public administrations. Estimations indicate that government spending on IT will increase on average 5.5% during 2023 compared to 20221 in line with post COVID-19 trends that have given to digital government a more prominent role in governments’ recovery plans (OECD, 2020[1]). Romania is not the exception as observed in the EU Recovery and Resilience Plan (RRF), with 21% of the total budget allocated to the digitalisation of public administration totalling EUR 1.5B2. The digital government component of Romania’s RRF includes resources to digitalise key policy areas such as justice, social protection, public procurement, civil service management as well as to advance key digital public infrastructure such as the government cloud infrastructure by the Ministry of Research, Innovation and Digitalisation (MCID) and the Authority for Digitisation of Romania (ADR)3; or digital identity with the leading role the ADR and the key involvement of the Ministry of Internal Affairs as custodians of the national identity system and related base registries (European Commission, 2022[2]).

The vast financial resources devoted to digital government demands strong public sector capacities to plan, execute and monitor investments in ways that secure that expected results and outcomes are delivered. The OECD has been supporting member countries to strengthen their ability to manage and address the financial implications of government digital transformation efforts through the Framework on Digital Government Investments (OECD, forthcoming[3]). The Framework builds on specific provisions of the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies to guide governments for an agile and cost-effective implementation of digital transformation policies, as well as on previous work developed by the Secretariat on business cases, ICT procurement and commissioning, and measuring digital government (Government Digital Service, 2019[4]; Digital Transformation Agency, 2015[5]).

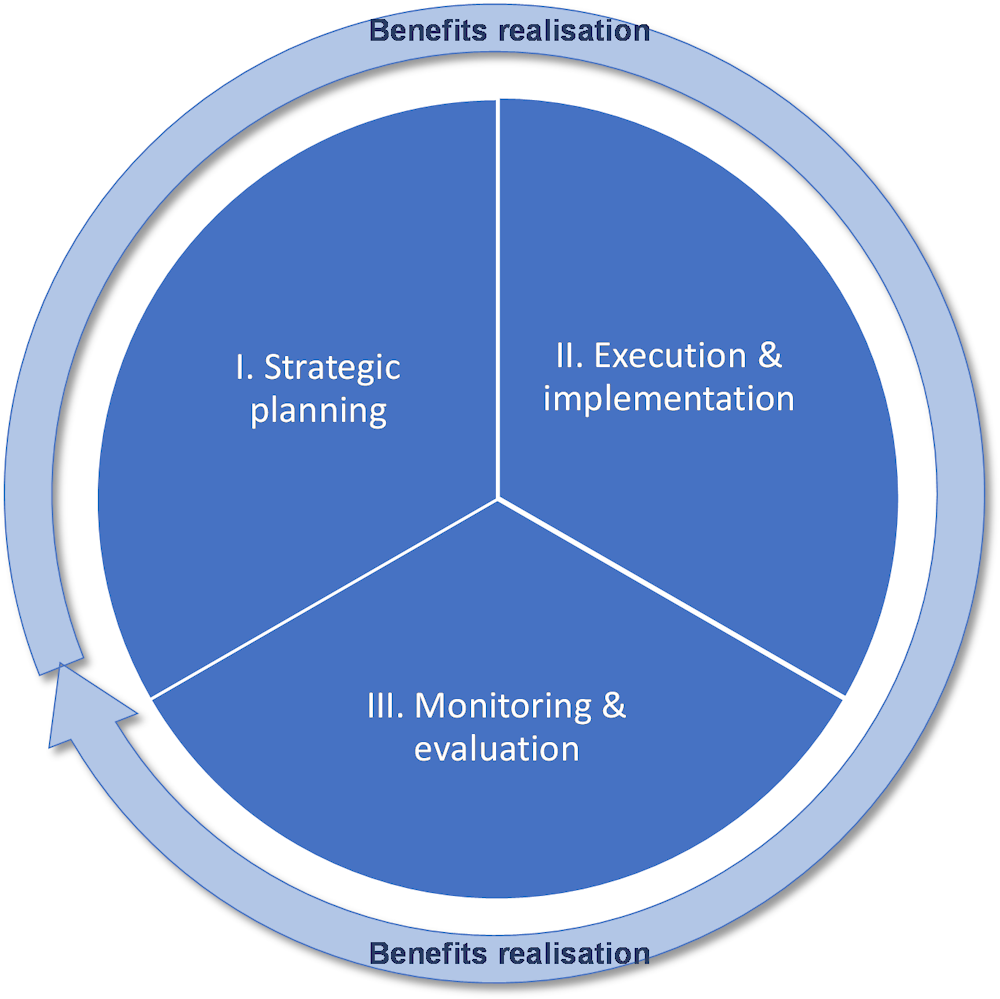

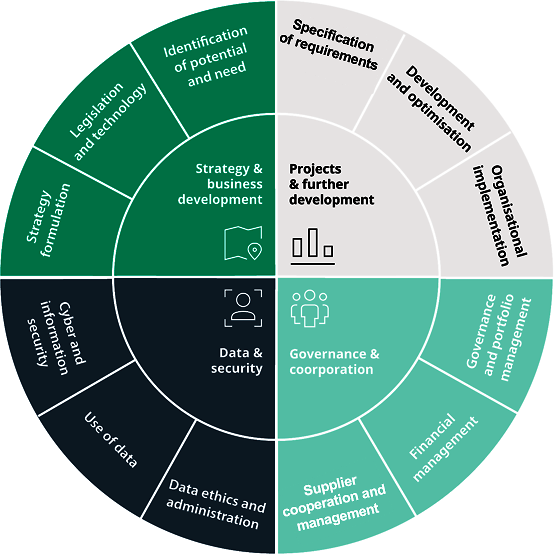

Building on the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government strategies to foster government capacities to be digital by design (OECD, 2014[6]), the OECD Framework for Digital Government Investments identifies three pillars and policy instruments needed for a coherent and systemic approach to take strategic decisions on investments and spend on digital government, which also inform the structure of this section (see Figure 3.1):

Strategic planning: public sector capacities for co-ordination and collaboration between relevant authorities, planning, value proposition, and risk management/mitigation mechanisms.

Execution and implementation: public sector capacities for investments’ management and prioritisation (including portfolio approach), funding sources and models, project management, public procurement mechanisms and practices, and govtech policies.

Monitoring and assessment: public sector capacities for investment accountability and progress monitoring; policy evaluation and return on investments; and end-user assessment.

Figure 3.1. The OECD Framework for Digital Government Investments

Strategic planning

In Romania, the planning for digital government is a shared task between the Committee for e-Governance and Red-Tape (Comitetului pentru e-guvernare și reducerea birocrației, CERB), as an inter-ministerial co-ordination entity under the Office of the Prime Minister and co-ordinated by the General Secretariat of the Government (GSG), and the Authority for Digitisation of Romania (ADR) at the MCID. However, as outlined in Chapter 2, the existing governance for digital government poses some challenges regarding the specific roles and clear co-ordination mechanisms for digital government in the country in terms of strategic and technical responsibilities for the implementation of the NDGS, which in turn have direct implications in the capacities the government has for co-ordinating and managing digital government investments in a coherent and whole-of-government way.

The responsibility for the strategic planning on government digital transformation is under the remit of the CERB4. The decision from the Office of the Prime Minister for the creation of the Committee in 2021 indicates that the functions and roles of the CERB include:

Establishing a co-ordination mechanism including all institutions responsible for the implementation, administration, and operation of digital public services.

Setting a framework for discussing main initiatives, measures, and projects regarding government digital transformation to ensure compliance with common technical standards and regulations.

Securing coherence in the co-ordination, monitoring and evaluation of the way of the government implements the digital government policy.

Prioritising and validating proposals regarding digital government and the operation of digital public services at the level of the institutions responsible for the implementation, administration, and operation of these services.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the CERB convened regularly to discuss key projects and prioritisation of digital government initiatives, including administrative simplification and government services agendas, which were paused during and after the pandemic. However, the CERB does not have a comprehensive mechanism or model in place to process, prioritise and follow-up on selected initiatives as indicated by several interviewees during the fact-finding mission. The CERB often operates as a show-and-tell space for the GSG and the ADR to provide updates on relevant initiatives and gather feedback from participant public sector institutions but does not have an organic functioning that enables decision-making and prioritisation on key initiatives.

On the other hand, the remit of the ADR is mostly technical covering initiatives on digital government as well as digital economy and society. The ADR originates at the Ministry for Communication and Information Society and was later transferred to the Office of the Prime Minister (funded with GSG’s budget). In 2020, digital government technical teams were transferred to the MCID to better align digital government with the national digital agenda, leaving the strategic co-ordination arm – CERB – at the CoG in the GSG given its acknowledged capacity to convene and enforce policy agendas. The mandate of the ADR includes approval of ICT digital projects prior to budget allocation and contracting procedures through the Technical-Economic Committee for the Information Society5 (Comitetul Tehnico-Economic pentru Societatea Informațională, CTE) (see Box 3.1). The CTE is a two-tier structure which includes a high-level management composed by authorities from different public sector institutions, as well as a technical evaluation team composed by technical experts from the ADR as well as from relevant public sector institutions. The CTE assesses the pertinence of project proposals and their adherence to national and EU priorities for their approval and further implementation. Only projects above the budget threshold of 2,000,000 LEI enter the project approval pipeline.

The existing governance for planning digital government investments shows limited coherence and consistency with a whole-of-government and cost-effective approach observed across OECD Member countries. The CTE does not operate in co-ordination with the CERB to define a common framework for project prioritisation, approval, funding and monitoring. The limited integration between the activities of the CERB and the ADR’s CTE results in two parallel agendas that are not necessarily aligned and do not secure coherence in managing digital government investments. This includes limited integration and co-ordination of cross-cutting projects and duplicated efforts, reducing the possibilities for horizontal collaboration between public sector institutions with common needs beyond informal trusted connection in specific institutions.

The existing system in place through the CTE does not address digital government investments from an end-to-end approach, limiting ADR’s existing capacity to secure return on investments and benefits realisation. Currently, the ADR does not have competencies nor mechanisms to enforce the adoption of digital investments tools and guidelines that promote a coherent planning and prioritisation of projects. In a context of limited enforcement, shadow IT costs and duplicated spending may expand in the Romanian public sector given the number of projects that are not assessed by the system, creating further legacy issues and limited integration that further deepen a silo-based approach for digitalisation of the public sector (e-government).

In this regard and in line with the recommendations to strengthen the governance for digital government, Romania could consider embedding clearly outlined mandates and responsibilities for the CERB and the CTE under a single and coherent process that integrates project value proposal, prioritisation and approval and that serves to collect and manage strategic information regarding investments on digital government. OECD countries are advancing in this regard, for instance Luxembourg that have created a two-layer governance model for digital government that includes clear mandate and responsibilities to co-ordinate investments on digital government (see Box 3.2).

Box 3.1. ADR’s Technical-Economic Committee

To oversee the development and monitoring of the Romanian Government's policy in information technology and its alignment with European policies, the Authority for the Digitalisation of Romania is supported by the Technical-Economic Committee for the Information Society, composed by

The president from the Authority for Digitalisation of Romania.

Four vice presidents with roles in information technology, including from the General Secretariat of the Government and one from the Ministry of Transport, Infrastructure, and Communications.

Permanent members from various ministries like Public Works, Finance, Education, European Funds, Internal Affairs, Health, and others, along with institutions like the Romanian Intelligence Service and the National Agency for Public Procurement.

Guest members from other public institutions.

For project approval, organisations submit documentation that includes detailed project information, value, funding type, existing infrastructure security, interoperability details, and justifications. The CTE’s opinion is considered related to feasibility studies and projects:

Before the initiation of public procurement contracts for projects exceeding 2,000,000 LEI (excluding VAT) financed from national funds.

Prior to submitting funding requests for projects exceeding 2,000,000 LEI financed from European funds.

Source: Authority for the Digitalisation of Romania (n.d.[7]), Technical-Economic Committee, https://www.adr.gov.ro/cte/ (accessed on 10 August 2023)

Box 3.2. Strategic and technical capacities to define the digital government policy in Luxembourg

Recent developments in the governance of digital government in Luxembourg have strengthened the public sector capacity to manage digital investments and to have a common and concerted policy framework to guide decisions on future investments.

After the creation of the Ministry for Digitalisation (MDIGI) in 2020, the Government of Luxembourg agreed to create a two-layered governance framework for digital government with the purpose of aligning both strategic and technical decisions regarding government priorities and policies for the digital transformation of ministries and administrations:

The High-Committee for Digital Transformation is the strategic governance instance. It was launched in September 2022 to bring together different ministers and societal actors to discuss about government priorities and actions to advance digital government and economy policies.

The Inter-Ministerial Committee for Digitalisation was established to co-ordinate ministries in the development and implementation of digital government initiatives. It aims to strengthen the co-ordination and coherence of actions within the government for the implementation of the Electronic Governance Strategy 2021-2025.

Source: OECD (2022[8]), Digital Government Review of Luxembourg, https://doi.org/10.1787/b623803d-en

Co-ordination and alignment with relevant budgetary and procurement processes is key for an investment framework that responds to the national political economy and to existing organisational culture, incentives and structures that influence investments’ decision making. In the case of Romania, evidence from the fact-finding mission and surveys sheds light on the limited collaborative approach for managing digital investments beyond compliance of existing national regulation and policy frameworks. Decisions taken either at CERB and CTE do not inform any specific budgetary or procurement process and are not linked to any broader policy framework beyond digital government. This includes existing processes in place to manage and co-ordinate EU funds allocated to digital transformation and which are managed by the Ministry of Investments and European Projects (Ministerul Investițiilor și Proiectelor Europene, MIEP), for example Romania’s Resilience and Recovery Funds (RRF)6 or Cohesion Policy Funds (CPF); or dedicated funds for research, development, and digitalisation such as EU’s Smart Growth, Digitisation and Financial Instruments Programme (Programul Creștere Inteligentă, Digitalizare și Instrumente Financiare, POCIDIF)7. In the context of the implementation of Romania’s RRF, the MCID recently created a dedicated Task Force for the Implementation and Monitoring of Reforms and Investments for Digital Transformation. The Task Force will oversee and manage the implementation of large IT projects under the responsibility of MCID that goes beyond digital government initiatives. In this regard, Romania could explore securing that decisions taken by the existing investment governance mechanisms (CERB and CTE) are binding to funding allocation and financial mechanisms in place, including those stemming out from Romania’s membership to the EU. Romania could consider piloting these capacities in the context of EU funds as observed recently in the case of Croatia, leveraging the value proposition mechanism in place (see Box 3.3)

Similarly, co-ordination with the National Agency for Public Procurement (Agenția Națională pentru Achiziții Publice, NAPP) seems limited. The ADR has the prerogative to strategically assist public sector institutions when conducting public procurement processes related to digital transformation, however this capacity has not been exerted yet due to the limited human resources at the ADR to address these issues and the limited availability of comprehensive soft instruments such as guidelines and standards to support public sector institutions when procuring goods and services related to digital technologies (for more details see next section Execution and Implementation).

Box 3.3. Informing decision-making on EU investments on digital government in Croatia

In Croatia, the Central State Office for the Development of Digital Society (CSODDS) is the government entity responsible for steering the implementation of the digital government strategy Digital Croatia 2032. As part of the renewed mandate for the CSODDS to effectively exert this mandate, recent developments in the allocation of EU funds for digital transformation have secured that CSODDS's value proposition and approval mechanisms are binding to allocate EU funds within the Institutional Framework 2021-2027. Such a policy lever has the potential to secure that EU funds dedicated to the digital transformation of the public sector are directly informed by the strategic priorities set for digital government in the country. Similarly, there is an expectation in Croatia that the decision-making responsibilities of CSODDS related to investments in digital government can be also applicable to national budget in the near future.

Source: OECD (2023[9]), Report for improved understanding of the quality of planning and implementation of public ICT/digital projects in Croatia and recommendations for improvement (unpublished)

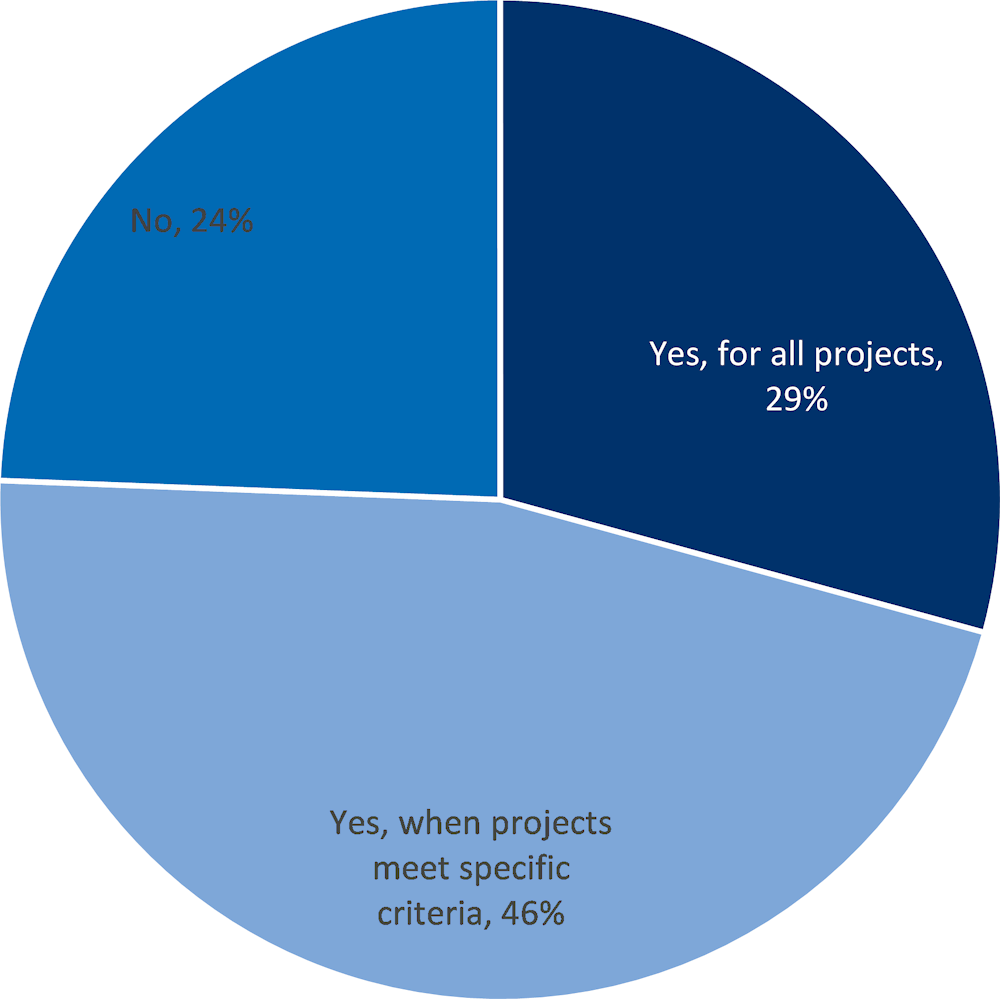

Within the OECD approach to digital government investments, value proposition mechanisms (also known as business cases) support strategic decision-making by assessing ICT/digital projects and products on their merits as well as promote adherence to national digital government standards and guiding principles (OECD, 2022[10]). As stated in the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies, countries are recommended to “develop business cases to sustain the funding and focused implementation of digital technologies projects, by i) articulating the value proposition for all projects above a certain budget threshold to identify expected economic, social and political benefits to justify public investments and to improve project management; ii) involving key stakeholders in the definition of the business case (including owners and users of final services, different levels of governments involved in or affected by the project, and private sector or non-for-profit service providers) to ensure buy in and distribution of realised benefits” (OECD, 2014[6]). As observed across OECD member countries, the adoption and use of value proposition mechanisms differ regarding the existence of such mechanism as well as the definition of thresholds to differentiate between investments (see Figure 3.2).

Figure 3.2. Availability of standardised models/methods to develop business cases

Note: Preliminary results of 41 member and accession countries that completed the survey

Source: OECD Survey on Digital Government 2.0

In Romania, the mechanism in place for value proposition is managed by the ADR through the CTE. Currently, the value proposition mechanism builds on a series of documents that constitute a dossier for each ICT/digital projects to be assessed by the CTE prior to budget allocation and contracting procedures. CTE is currently composed by technical experts from the ADR as well as from relevant public sector institutions to assess the pertinence of business cases and their adherence to national and EU priorities for their approval and further implementation. Only projects above the budget threshold of LEI 2M (equivalent to EUR 400K) enter the project approval pipeline. As previously stated, this value proposition mechanism does not inform any decision-making taken by the GSG’s CERB. Despite the formal mechanisms in place and high compliance across the public sector, government institutions in Romania seem not to be widely familiarised with the procedure; only 3 out of 16 surveyed institutions declaring knowing its existence8, in line with the perceptions captured during the fact-finding mission. In this regard, more efforts could be done by ADR to clearly communicate the purposes and added value of this mechanism.

When public sector institutions present their projects to the CTE, the list of forms and information to provide includes:

Basic details such as project name, relevant dates and project owner.

Value and breakdown in several funding sources.

Critical data related to measures taken to assure interoperability, security, non-duplication, and technology neutrality of spending on ICT/digital projects.

Appendices providing further evidence and details related to the two elements above.

The current mechanism in place in Romania to assess value proposition largely focuses on the technical qualities and merits of ICT/digital projects and do not pay attention to the multi-dimensional benefits such projects can deliver e.g., to achieve NDGS or other policy goals. As such, the existing procedure is a missed opportunity to leverage key information that can empower the ADR to take strategic decisions, influence budget decision-making or have a more granular monitoring of key initiatives from their conception to the realisation of their intended benefits. In this regard, Romania could consider revisiting the value proposition mechanism and its governance within the Romanian public sector to transit from a technical review to a strategic assessment system. This may include redesigning the proposition procedure, requesting more strategic information to project beneficiaries that includes expected benefits, CAPEX and OPEX indicators, risk assessment, alternative solutions, among others. A similar approach is taken in New Zealand, where the Treasury manages the investment approval process including the business case (see Box 3.4). Romania may consider the work done by the OECD and Australia through the Business Case Playbook to redesign the value proposition mechanism (see Box 3.5).

Box 3.4. Value proposition mechanism in New Zealand

New Zealand’s Better Business Cases is a methodology to enable smart investment decisions for public value. It involves the use of a business case to demonstrate that a proposed investment is strategically aligned, represents value for money and is achievable. It aims to allow decision-makers to analyse objectively with consistent information, make smart investment decisions for public value, and reduce the costs and time for developing business cases.

Source: New Zealand Treasury (2022[11]). Better Business Cases™, https://www.treasury.govt.nz/information-and-services/state-sector-leadership/investment-management/better-business-cases-bbc (accessed on 10 August 2023)

Box 3.5. OECD Business Case Playbook

This Playbook is designed to guide countries in defining persuasive business cases to underpin investment decisions in digital transformation and ICT, delineating successful strategies and common challenges. Led by Australia’s Digital Transformation Agency as part of the work of the OECD E-Leaders and draws insights from the experiences of member nations like Australia, Canada, Denmark, Estonia, and the United Kingdom. It delves into the essential elements of a business case needed to make a strong case for digital or ICT investments, with each section focusing on a critical aspect of business case formulation, enriched by resourceful links around 10 plays:

1. Set the foundations:

a. Define a dedicated team

b. Engage key stakeholders and senior officials

c. Scope the preliminary work

2. Discover the problem and options

a. Understand the problem

b. Engage stakeholders early and often

c. Explore options

3. Test possible alternatives

a. Define options

b. Select preferred solutions

4. Define the business case

a. Draft the business case

b. Review and refresh

Source: OECD and Digital Transformation Agency (2020[12]), Business Cases Playbook, https://www.dta.gov.au/resources/OECD-Business-Case-Playbook (accessed on 10 August 2023)

Given significant resources for government digital transformation come from EU funds, improved co-ordination and streamlining of value proposition processes with the MIEP could be considered by the ADR as well. Currently, the value proposition mechanism managed by the CTE only requests the project code provided by MIEP in case projects were first applied through the national EU funds (SMIS code)9. Given the formal requirement to apply to EU funds through MIEP, public sector institutions observe ADR’s value proposition mechanism and CTE as increased bureaucracy that brings limited added value for the implementation of this project. Romania could consider exploring the integration of application and value proposition processes, or at least leveraging the application process to EU funds in ways that public sector institutions benefit from strategic advisory prior to funding allocation through MIEP. In practice, this may require adjusting EU funds implementation or regulatory frameworks to incorporate a mandatory validation from CTE to approve digital transformation projects in the public sector, as per observed in other EU countries to structure the implementation of EU investments in digitalisation (see Box 3.3).

Execution and implementation

Strategic planning for ICT/digital projects in the public sector leads to execute financial resources, implement initiatives and, if needed, contracting solutions in the market to complement public sector institutions’ capacities for digital transformation. In the context of a whole-of-government approach to digital government investments, once value proposition of ICT/digital projects has been stated, governments should prioritise and approve initiatives to be implemented.

In Romania, project technical assessment and approval are managed by the CTE. As stated in the previous section, projects financed with EU funds are requested to go through two approval processes (MIEP and ADR). In this regard, ADR’s process acts as a technical validation before decisions are taken by MIEP, without having a strategic role in the prioritisation of EU funds for digital government in practice.

Project approval process happens in practice:

For national funds: before beneficiaries start the public procurement award process, in case of financing projects with a specific component on ICT with a nominal or cumulative value greater than LEI 2M.

For EU funds: before beneficiaries submit the funding request to the competent authorities, as well as before starting public procurement award process, in the case of funding projects with an ICT component with a nominal or cumulative value greater than LEI 2M.

Criteria for ICT/digital project prioritisation and approval remains unclear for most of interviewed public sector institutions. In fact, according to the ADR and CTE, almost all projects are approved, and the ones that are contested can be reformulated by the responsible authorities prior for the CTE to reconsider them. On the other hand, public sector institutions remain unclear about what are the criteria used to approve/contest initiatives, and Romania could consider further communicating what criteria is used, or to develop collaboratively guiding principles and policy goals to be achieved with the approval process, e.g., contributing to the achievement of the NDGS or other policy frameworks in place. Romania could consider establishing a prioritisation framework built together with relevant authorities such as MIEP, GSG and the recently created Task Force at the MCID, integrating different policy priorities and helping better connect the technical validation with funding approval. Currently the CTE’s process request information regarding cybersecurity and interoperability, but further efforts could be devoted to secure human-centric and integrated digital service delivery as seen in countries such as Australia and Ireland (see Box 3.6).

Box 3.6. Prioritisation frameworks for digital government investments in Australia and Ireland

Australia

The ICT Investment Approval Process (IIAP), part of the Digital and ICT Investments Oversight Framework , is used by the Digital Transformation project to validate all digital projects over AUD$ 30 million (app. €20 million). The IIAP aims to assist beneficiaries in the public sector in developing comprehensive business cases and secure the effective implementation of digital and ICT-enabled proposals, linking the value proposition with the project approval.

Ireland

The Office of the Government Chief Information Officer (CIO) at the Department for Public Expenditure and Reform, established a blind peer review process to approve ICT/digital projects . It brings together national government experts on digital government and define a procedure in which they provide technical and business assessment to validate the value proposition and enter the project into the approval pipeline.

Source: Digital Transformation Agency (2022[13]), Digital and ICT Investment Oversight Framework, https://www.dta.gov.au/help-and-advice/digital-and-ict-investments/digital-and-ict-investment-oversight-framework (accessed on 10 August 2023) and Department of Public Expenditure and Reform (2022[14]), Connecting Government 2030: A digital and ICT strategy for Ireland’s Public Service, https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/136b9-connecting-government-2030-a-digital-and-ict-strategy-for-irelands-pu (accessed on 10 August 2023)

Furthermore, the information gathered by the CTE and ADR is not managed in ways that delivers strategic information for decision-making and monitoring of digital government investments in the short, medium, or long term. Collected forms and applications submitted for the CTE and ADR to approve or contest projects is not strategically leveraged in the public sector, and do not serve for any further whole-of-government analysis regarding national and institutional priorities, possible synergies or government trends related to the investments on digital government. The limited capacity to strategically use this information promotes further lack of integration and co-ordination of projects, limiting collaboration between agencies for the implementation of ICT/digital projects. Similarly, the limited knowledge and use of this value proposition and project approval mechanism by public sector institutions in Romania (only 2 out of 16 public sector institutions declared going through the project approval process) implies that a significant fraction of investments may be creating shadow IT costs, duplicated efforts or large dependency on legacy systems that further deepen the e-government mindset and practice in Romania.

Looking ahead, Romania could consider integrating existing value proposition, project approval and prioritisation under an ICT project portfolio approach as most advanced OECD member countries have been developing for several years for a more strategic management of digital government investments. The purpose of an ICT portfolio approach is to collect, manage and produce strategic information that feeds government decision making on digital transformation policies. While several steps are related to the application and funding of initiatives, an ICT portfolio approach supports the production of information for monitoring and eventually assessing investments. Currently, the ADR and CERB have no information in practice to exert the mandate of co-ordination, alignment and collaboration when implementing digital government investments.

Any action by the ADR and GSG towards the consolidation of an investment framework for government digital transformation would require the close involvement of the Ministry of Finance (Ministerul Finanțelor, MF) and the MIEP given the implications with national and EU funds, as well as that the existing regulatory frameworks and policy instruments in place partially address some of these challenges, e.g., collecting, managing and producing information to monitor the implementation of investments in the context of EU regulation and compliance to standards.

The experience of OECD member countries can inspire Romania to find innovative and effective ways to consolidate existing fragmented policy levers into a single and streamlined process, aligned with EU funding requirements and standards. For instance, Denmark has developed their ICT portfolio management system that has become the neural point for decision making on digital government investments. A similar approach has been taken by Lithuania and the Ministry of Economy and Innovation to improve the coherence on government spending and to empower the leading digital government authority to exert its co-ordination mandate beyond technical validation and approval of ICT/digital initiatives (see Box 3.7).

Box 3.7. ICT portfolio management in Denmark

The Agency for Digitalisation develops and maintains the cross-governmental ICT project model and the ICT System Portfolio model. The project model contributes to a streamlined and homogenous planning, management, and implementation of ICT projects across government bodies while the system portfolio model supports a responsible and secure management of government ICT initiatives. By supporting governmental institutions through advice and assistance in standardised procedures, these models allow line ministries and agencies to take informed decision when developing digital solutions and secure alignment with strategic goals. These models aim at strengthening governmental ICT projects' planning, management, and implementation, promoting national standards alignment while decentralising decision-making.

Source: Agency for Digitalisation (2022[15]). The ICT Project Model and the ICT System Portfolio Model, https://en.digst.dk/digital-governance/government-ict-portfolio-management/the-ict-project-model-and-the-ict-system-portfolio-model/ (accessed on 10 August 2023)

Finally, investments decisions can materialise into in-house development or outsourcing to the private sector. In Romania, outsourced ICT/digital goods or services are framed under the existing public procurement policy and regulation10, which transposes the EU regulation on this matter. Public procurement policy is under the responsibility of the National Agency for Public Procurement (Agenția Națională pentru Achiziții Publice, NAPP). Evidence from the interviews and survey indicates that collaboration between the NAPP and ADR occurs only in the context of the mandate to the ADR to support digitalisation of specific public policy areas, including public procurement. As a result, the ADR is fully responsible to provide on demand services and assistance to NAPP for the management of the national e-procurement system. Regarding issues on public procurement of digital transformation in government, currently there are no specific or dedicated initiatives, support, guidance or instruments that equip public sector institutions to procure ICT/digital goods and services in the country. This poses significant challenges to public sector institutions in a context in which most digital transformation efforts have to be outsourced given the limited financial and organisational incentives to attract, retain and promote professional digital talent and skills in the Romanian public sector (see next section).

When looking at the specific practices of Romanian public sector institutions to contract ICT/digital goods and services, most surveyed institutions declared preferring open public tenders, framework agreements and direct purchasing (see Table 3.1). In contrast, procurement mechanisms that promote a more collaborative and co-creation environment for digital transformation, such as public-private partnerships (PPPs), challenge-based or innovation partnerships almost not considered as possible alternatives. Interviews shed light on the reasons: previous cases of corruption in public procurement have created a risk-averse culture in public procurement for which both NAPP and contracting authorities prefer to adhere to regular practices rather than exploring options included in the national regulation.

Table 3.1. Limited innovative procurement practice in digital government in Romania

|

Frequency |

Framework agreements (enabling repeated purchasing under predefined conditions) |

Open public tenders (including tenders with negotiation) |

Direct purchases (e.g. single source purchasing) |

Purchases below thresholds of formal tender procedures |

Public-private partnerships (project-financed schemes) |

Challenge-based and/or prize-based procurements |

Innovative public procurement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Always |

13% |

44% |

0% |

0% |

0% |

0% |

0% |

|

Often |

25% |

38% |

13% |

13% |

0% |

0% |

0% |

|

Sometimes |

25% |

13% |

44% |

19% |

19% |

6% |

6% |

|

Rarely |

6% |

6% |

38% |

38% |

13% |

6% |

0% |

|

Never |

31% |

0% |

6% |

31% |

69% |

88% |

94% |

Note: Results from 16 participant institutions at the central level

Source: OECD Survey on Digital Government in Romania (2022)

Romania’s public procurement law comprises a wide range of mechanisms and instruments that can support more agile and iterative developments beyond regular tendering processes or framework agreements - including dynamic purchasing systems, innovation partnerships, competitive dialogues and tendering for a solution project (OECD, 2015[16]). However, and as evidenced during the fact-finding mission, public sector authorities in Romania do not have the awareness, knowledge, and capacities for adopting more innovative ICT procurement mechanisms. Both the ADR and the National Agency for Public Procurement could play an important role in disseminating the benefits of these mechanisms given the existing lack of capacities in the public sector to conduct coherent and comprehensive ICT/digital project implementation from the formulation phase through procurement, monitoring, and assessment.

To fulfil ADR’s mission to support public sector institutions in their digital transformation journeys, Romania could consider establishing dedicated instruments to assist the procurement of ICT/digital goods and services drawing upon the existing regulatory framework for public procurement. Currently, NAPP has issued guidance on green criteria for procuring computers and laptops11, contract management12 and demo requests in the implementation of IT systems13. However, these do not constitute a comprehensive set of supporting instruments for public sector institutions to address ICT procurement.

Possible ways forward include developing dedicated guidelines for ICT procurement and commissioning in which public sector institutions can get inspired to test new mechanisms as well as can promote visibility and awareness about the added value such means could bring for the implementation of their digital transformation initiatives. Countries across the OECD are adopting dedicated practices and frameworks for procuring digital technologies in the public sector (see Table 3.2). Practices from OECD member countries can serve as inspiration for action-oriented measures that can contribute in this direction (see Box 3.8, Box 3.9 and Box 3.10). ADR could become a strategic partner for public sector institutions to address some of the challenges of public procurement, complementing their existing technical remit with more strategic and policy-oriented support. This would require strengthened co-ordination and collaboration with NAPP to better exploit the possibilities that the transposition of EU regulation can offer.

Table 3.2. Use of standardised policy levers at the central/federal government level

|

Business cases |

ICT procurement |

ICT project management |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Belgium |

□ |

■ |

■ |

|

Canada |

■ |

■ |

■ |

|

Chile |

■ |

■ |

□ |

|

Colombia |

□ |

■ |

■ |

|

Czech Republic |

■ |

■ |

□ |

|

Denmark |

■ |

■ |

■ |

|

Estonia |

■ |

□ |

□ |

|

Finland |

□ |

□ |

□ |

|

France |

■ |

■ |

■ |

|

Germany |

□ |

■ |

■ |

|

Greece |

□ |

□ |

■ |

|

Iceland |

□ |

□ |

■ |

|

Ireland |

□ |

■ |

■ |

|

Israel |

■ |

■ |

■ |

|

Italy |

□ |

■ |

□ |

|

Japan |

■ |

■ |

■ |

|

Korea |

■ |

■ |

■ |

|

Latvia |

□ |

□ |

□ |

|

Lithuania |

□ |

■ |

□ |

|

Luxembourg |

■ |

□ |

■ |

|

Netherlands |

□ |

■ |

■ |

|

New Zealand |

■ |

■ |

■ |

|

Norway |

■ |

■ |

■ |

|

Portugal |

■ |

■ |

■ |

|

Slovenia |

■ |

■ |

■ |

|

Spain |

■ |

■ |

■ |

|

Sweden |

■ |

■ |

□ |

|

United Kingdom |

■ |

■ |

■ |

|

OECD Total |

|||

|

Yes ■ |

17 |

22 |

20 |

|

No □ |

11 |

6 |

8 |

Note: Data are not available for Australia, Hungary, Mexico, Poland, the Slovak Republic, Switzerland, Türkiye and the United States.

Source: OECD (2020[17]), “Digital Government Index: 2019 results”, https://doi.org/10.1787/4de9f5bb-en.

Box 3.8. Digital marketplace in the United Kingdom

In 2014, Government Digital Service (GDS) launched the Digital Marketplace as an online service to facilitate the government’s ability to find and procure technology for the public sector. The Digital Marketplace aimed to be a more straightforward, faster and cost-effective method for the government to buy technology, redefining the government’s relationship with technology providers. In this line, it helped the UK government support market engagement and a multidisciplinary approach at the pre-procurement stage.

Source: Government Digital Service (n.d.[18]), Digital Marketplace, https://www.digitalmarketplace.service.gov.uk/ (accessed on 10 August 2023)

Box 3.9. Centralised procurement of digital technologies

Acknowledging the advantages of centralising ICT procurement, many OECD nations have established dedicated ICT Central Purchasing Bodies (CPBs). For example, in 2017, Germany set up the Central Office for IT Procurement within the Federal Procurement Office of the Federal Ministry of the Interior. This establishment serves as the primary hub for federal-level ICT procurement. In its early stages, its role was primarily advisory, assisting users throughout the procurement cycle, from the initial need identification to contract management for the entire duration of contracts. However, since its inception, it has transitioned to also managing tenders on behalf of the contracting bodies.

Similarly, Ireland adopted centralised ICT procurement to align with its Public Service ICT Strategy. This initiative is led by the Office of Government Procurement, Ireland's designated CPB. The Irish model prioritises government-wide IT applications used across multiple departments. This central approach is especially effective for streamlining universally used applications like payroll or messaging. However, when it comes to technology specific to a particular agency, decision-making authority remains decentralised, residing with the respective agency.

Source: OECD (2022[10]), Digital Transformation Projects in Greece’s Public Sector: Governance, Procurement and Implementation, https://doi.org/10.1787/33792fae-en.

Box 3.10. ICT procurement guidelines in Australia

In Australia, the Digital Transformation Agency (DTA) is responsible for public procurement of ICT/digital goods and services. As part of the BuyICT marketplace, the DTA offers comprehensive support to public sector institutions to guide them when sourcing digital technologies. This includes tools for planning sourcing, contract templates, pre-approved clauses to include in contracts, and support for early market research, among others.

Source: Digital Transformation Agency (n.d.[19]), BuyICT, https://www.buyict.gov.au/sp?id=sourcingguidance (accessed on 10 August 2023)

Within the public procurement policy area, Romania faces structural challenges to attract and promote digital talent and skills, while the IT industry benefits from a series of financial incentives that makes the public sector not capable to compete with the private sector to hire professional digital skills14. While this poses serious constraints for developing a competent digital workforce (see next section), it may create opportunities for Romania to explore the possibility to expand the pool of suppliers by better engaging with SMEs, entrepreneurs, start-ups and innovators to co-develop digital government solutions. Govtech policies, labs and exercises are gaining momentum within NDGS. Leveraging existing innovative procurement mechanisms, Romania and the ADR could consider developing a dedicated govtech initiative that connects the supply and demand side to experiment with emerging technologies, promote a culture of collaboration and innovation within the public sector, and increase the cost-effectiveness of solutions by testing, experimenting and scaling up digital transformation initiatives. OECD member and partner countries in Europe and Latin America are strategising with govtech to better deliver their NDGS, creating dedicated innovation funds, enforcing the implementation of govtech initiatives through national legislation, creating dedicated govtech labs and implementing innovation partnerships and design contests.

Box 3.11. Govtech initiatives in Scotland and Luxembourg

Scotland

CivTech is a Scottish Government programme that brings people from the public, private and third sectors together to address public challenges. The open challenge provides technical and financial support to build a Minimum Viable Product (MVP) in close collaboration with the beneficiary. The incremental and iterative approach offers an opportunity for innovators to collaborate between themselves and with public sector institutions to solve specific problems shared among different organisations. The programme has run several rounds, including a tailored sprint challenge, providing the public sector with proven solutions.

Luxembourg

The GovTech Lab was launched in 2021. Overseen by the MDIGI and CTIE, the GovTech Lab promotes a dynamic and flexible culture within ministries and administrative bodies, encouraging the creation of novel digital public service solutions. The Lab adopts an open innovation strategy, facilitating collaboration between internal governmental bodies and external participants via challenges defined based on the needs of the public sector.

At present, the Lab is leveraging innovation partnerships. These offer a platform for startups and entrepreneurs to showcase solutions that can scale up from a proof of concept to a fully realised solution procured and rolled out by the CTIE.

Source: Scottish Government (2022[20]), CivTech, https://www.civtech.scot/ (accessed on 10 August 2023) and OECD (2022[8]), Digital Government Review of Luxembourg, https://doi.org/10.1787/b623803d-en

Monitoring and evaluation

Increased budget and funding available for digital government also builds the case for public sectors to be more effective in monitoring progress and assessing final results and outcomes. Monitoring uses systematic collection of data on specified indicators to provide the management and the main stakeholders of an on-going intervention with indications of the extent of progress and achievement of objectives and progress in the use of allocated funds. The OECD Recommendation on Digital Government Strategies advises adherent countries to “reinforce institutional capacities to manage and monitor projects’ implementation, by:

adopting structured approaches systematically, also for the management of risks, that include increase in the amount of evidence and data captured in the course of project implementation and provision of incentives to augment data use to monitor projects performance;

ensuring the availability at any time of a comprehensive picture of on-going digital initiatives to avoid duplication of systems and datasets;

establishing evaluation and measurement frameworks for projects’ performance at all levels of government, and adopting and uniformly applying standards, guidelines, codes for procurement and compliance with interoperability frameworks, for regular reporting and conditional release of funding.” (OECD, 2014[6])

In Romania, evidence indicates that the public sector does not have a dedicated monitoring framework or system to track progress of the implementation of the NDGS or key initiatives under the remit or advisory support of the ADR. This contrasts with the existing legal mandate of the ADR as entity responsible for monitoring and evaluating digital government policies as indicated in the Law that regulates its organisational structure and competencies15. Despite the existence of the CTE and the project approval mechanism in place, the wealth of information collected by the ADR for this purpose is not managed in a way that can equip them with strategic information for monitoring of the strategy and related initiatives. The limited availability and use of strategic information from digital government investments hampers the capacity of the ADR to oversee projects from conception to delivery and maintenance. The absence of such an approach represents a missed opportunity for having a more transparent and accountable operation and monitoring of digital projects and funds to strategically empower ADR.

In the area of reporting and monitoring, the ADR publishes information online through its website about key projects completed and under development, as well as their milestones, involved entities including project beneficiaries and funding sources16. Similarly, ADR publishes every quarter regular digitalisation report to share key activities and news within its mandate17 - of which the last version dates from June 2022. While these actions are positive and contribute to the transparency and openness of ADR’s work, they do not constitute a comprehensive approach to monitor actions that help ADR, GSG and the broader public sector to track progress of investments on digital government. One of the reasons why such a framework is not in place may be explained by the technical mandate and nature of ADR’s activities.

Ongoing actions occur in the context of monitoring EU funds, under the responsibility of the MIEP. Since the reporting occurs between funding sources and beneficiary institutions, ADR is only involved in projects and resources under its immediate remit and not related initiatives implemented by other public sector institutions. This includes the platforms MySMIS18 and Fonduri-EU.RO19 which comprises monitoring and evaluation of EU programmes. Building on these existing platforms, Romania could consider developing a dedicated monitoring framework that, integrating with existing platforms and systems for EU funds, provides a detailed picture of ongoing projects and initiatives, helping achieve ADR’s responsibility for monitoring digital transformation initiatives in the public sector.

Such a comprehensive approach would require to collectively define key performance indicators (KPIs) as well as other relevant information that will serve to monitor digital investments. Alternatively, Romania could consider short-term actions, focusing monitoring activities on selected cross-organisational projects that involves significant resources, co-ordination and ownership between several public sector institutions. Efforts observed in France could serve as inspiration to advance with tangible actions in this field (see Box 3.12). In the medium- or long-term, Romania could consider expanding monitoring actions to all public sector institutions, including developing dedicated digital maturity indicators that goes beyond specific activities or project in order to inform priorities and actions in future digital government strategies (see Box 3.13).

Box 3.12. Project oversight in France

In France, the Digital Interministerial Directorate (DINUM) has set up a consistent mechanism to track strategic ICT/digital initiatives within the French government. The "Overview of the State's Major Digital Initiatives" supervises digital transition efforts that either have a budget exceeding 9M euros or hold considerable strategic relevance for the public sector, considering factors like impact on various users, associated risks, and more.

This overview gathers periodic updates regarding the ongoing status, advancements, projected expenses, and timelines of these projects. Based on this data, DINUM recommends adjustments to public entities and aids in ensuring the anticipated benefits are achieved.

Moreover, DINUM releases key performance metrics in accessible and visual means about progress of implementation, promoting greater responsibility and public scrutiny over government digital spending.

Source: Direction interministérielle du numérique (n.d.[21]), Panorama des grands projets numériques de l’État, https://www.numerique.gouv.fr/publications/panorama-grands-projets-si/, (accessed on 10 August 2023)

Box 3.13. Digital government indicators in Colombia

Ministry of Information Technologies and Communications (MINTIC) developed a Digital Government Index as a measurement tool to support the implementation of the digital government strategy. The measurement provides disaggregated data on the performance of national and territorial entities regarding digital government policy. MINTIC publishes the index results at a disaggregated level using an interactive platform, and the data is available on the open data platform of the Government of Colombia.

Source: MINTIC (2022[22]), Índice de Gobierno Digital, https://colombiatic.mintic.gov.co/679/w3-propertyvalue-36675.html (accessed on 10 August 2023)

Finally, ICT/digital projects are implemented to transform the experience of users in ways that public value can be delivered, to meet their needs and to increase their satisfaction with government digital services and processes. Users may include citizens, businesses, and civil servants if intended investments transform government processes. Romania does not have a consolidated, single satisfaction measurement methodology to assess the experience of users with digital government processes and services. OECD work also demonstrate the intrinsic relationship between user satisfaction with digital public processes and services with public trust in democracy and public sector institutions (OECD, 2022[23]).

There are ongoing practices in the Romanian administration to measure user satisfaction. For example, the National Agency for Fiscal Administration (Agenţiei Naţionale de Administrare Fiscală, NAFA). NAFA implements an annual satisfaction mechanism to adapt to new trends and requirements in the economic environment. In 2021, opinion polls were conducted to provide NAFA senior management with sensitive information regarding tax administration as well as the perception of the Agency (both its employees and users). The National Trade Registry Office(Oficiul National al Regsitrului Comertului, NTRO) adheres to change management practices according to ISO 9001 Quality Management System, including surveys and questions to capture relevant information from users. The Ministry of Internal Affairs (Ministerul Afacerilor Interne, MIA) includes user satisfaction tools in all services offered through https://hub.mai.gov.ro, where users are asked to give an overall rating to the service, specify whether the information provided is clear or not, and to make suggestions for improvement.

Looking ahead, Romania and the ADR could consider advancing towards frameworks that meaningfully capture the experience of users with digital public processes and services, building on the experience of OECD countries and the progress done by Romanian public sector institutions with more digital maturity (see Box 3.14). This would be particularly relevant in the context of implementing EU RRF, as most of the resources are devoted to digitalising government services; as well as existing core digital public infrastructure being developed by ADR such as digital identity. Securing a user-driven approach in government services and digital infrastructure is critical for an inclusive and responsive digital transformation agenda in the country.

Box 3.14. User satisfaction measurement in Australia and Ireland

Australia

The Australian Government measures user satisfaction through the Trust in Public Services Report. Since its creation in March 2019, the survey has included over 43,000 responses, primarily focusing on feedback concerning Australian public services. These services are also commonly referred to as Federal, National, or Commonwealth services. The feedback extends to all public services utilised within the past year. The results obtained are validated by the Australian Bureau of Statistics. Furthermore, the methodology underwent an independent review by the ANU Centre for Social Research in 2019 and was put to the test through two pilot studies. The survey adopts a people-centric perspective, inquiring about life events and the support offered by these services.

Ireland

Since 1997, the Irish government has conducted a survey to assess the satisfaction levels with services received from civil service departments and offices. The measurement also captures general perceptions of, and attitudes to, the civil service. The survey was undertaken by a private provider on behalf of the Public Service Transformation Delivery Unit in the Department of Public Expenditure and Reform, following an open tendering process.

Source: Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (2022[24]), Trust in Australian public services: 2022 Annual Report, https://www.pmc.gov.au/publications/trust-australian-public-services-2022-annual-report (accessed on 10 August 2023) and Department of Public Expenditure and Reform (2022[25]). Minister McGrath welcomed the Results of the 2022 Civil Service Business Customer Survey. https://www.gov.ie/en/press-release/6f52d-minister-mcgrath-welcomed-the-results-of-the-2022-civil-service-business-customer-survey (accessed on 10 August 2023)

Digital talent and skills in the public sector

Introduction

Digital transformation, including digital government, happens in the context of people, their capacities, and the organisational context for them to experience the digital age. Securing a competent and digital savvy workforce in the public sector is a fundamental pillar for governments that aim to transform public processes and services in meaningful ways beyond replicating analogue processes into digital means.

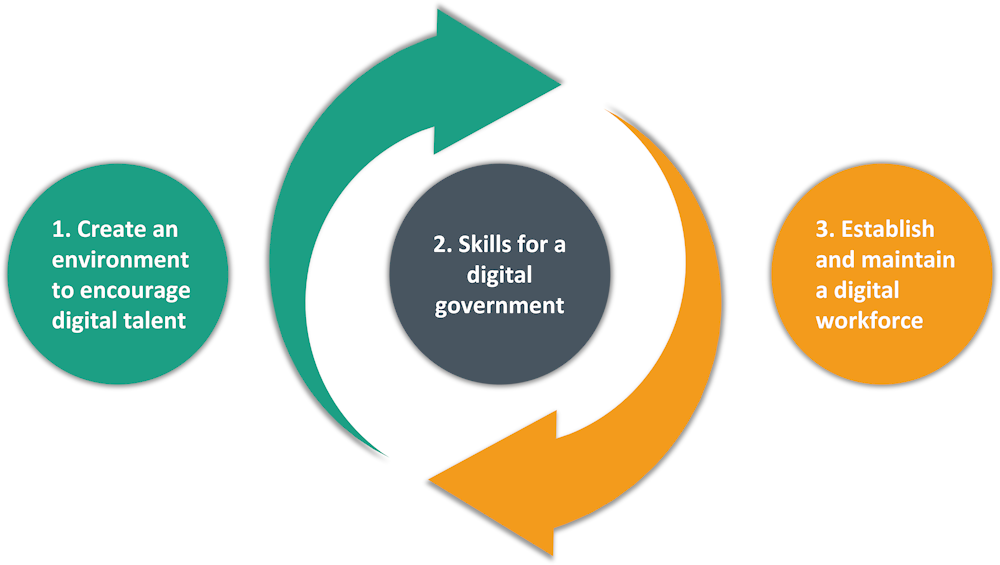

The OECD works with member and partner countries to build digital government competency and capacity to develop digital talent and skills in the public sector. This requires looking not only at the skills needed to support government digital transformation, but also at the organisational enabling conditions for a digital workforce in the public sector as well as actions towards attracting, promoting, and retaining the right digital talent and skills to support digitalisation efforts and the implementation of NDGS. The OECD Framework for Digital Talent and Skills in the Public Sector informs the analysis and recommendations to strengthen digital workforce policies in the Romanian public sector (OECD, 2021[26]). The framework is constituted by three pillars (see Figure 3.3):

Pillar 1 covers the importance of the context for those working on digital government and discusses the environment required to encourage digital transformation.

Pillar 2 addresses the skills to support digital government maturity, covering all public servants, particular professionals, and those in leadership roles.

Pillar 3 considers the practical steps and enabling activities required to establish and maintain a workforce that encompasses the skills to support digital government maturity.

Figure 3.3. The OECD Framework for Digital Talent and Skills in the Public Sector

Source: OECD (2021[26]), Framework for Digital Talent and Skills in the Public Sector, https://doi.org/10.1787/4e7c3f58-en.

The overview of digital talent and skills with be structured and focused on the organisational conditions for digital talent and skills in Romania (pillar 3), as well as specific activities and initiatives supporting the development of specific skills to support the digital transformation of the country (pillar 2).

Organisational conditions for digital talent and skills in the public sector

In Romania, the ADR has the legal prerogative to look after the development of digital talent and skills in the public sector. As stipulated in the overarching Law that structures ADR’s mandate and responsibilities, the institution should “elaborate the national plan for the development of digital skills within the public administration and ensure its implementation, in collaboration with other competent authorities, in accordance with the law”20. ADR’s responsibility to develop digital talent and skills in the Romanian public sector is encompassed by the legal role of the National Agency for Civil Servants (Agenţia Naţională a Funcţionarilor Publici, NACS)21 as overarching institution in charge of national civil service policy, recruitment, and talent development in the Romanian government. However, evidence from the fact-finding mission indicates that there is limited co-ordination between these two entities to adopt a comprehensive framework for digital talent and skills. The limited co-ordination observed to develop the national policy on digital talent and skills in the Romanian public sector brings unclarity regarding who is the authoritative institution to reach out to by public sector institutions in this field.

In this context, the peer review process identified that aspects related to attracting, promoting and retaining digital talent in the public sector are not clearly addressed, including an unclear active responsibility and mandate to foster digital talent and skills in the public sector. Observations from this evidence include the fact that there is not a clearly identified authoritative place where profiles and skills are defined and communicated to enable all to meet certain expected levels and standards on digital skills (e.g., IT director and management skills, agile approaches, user driven, data standards, roadmap building). In this regard, Romania does not have a clear strategic approach to address digital talent and skills in the public sector that articulates public sector institutions to equally develop digital skills across the Romanian government.

The absence of a clear strategic path for digital talent and skills becomes particularly critical to address considering how relevant this topic is for surveyed institutions in this review; 10 out of participant institutions indicated that digital talent and skills is considered a high or very high priority for their institutional digital transformation paths. Looking ahead, Romania could consider developing a dedicated digital skills framework for the public sector. This involves articulating efforts across the public sector, leveraging the mandate of the ADR with the overarching policy role of the NACS on civil service issues to jointly define a roadmap for the digital skills needed in the Romanian workforce as well as the upskilling and promoting actions needed in the medium and long term. OECD countries can serve as a source of inspiration for Romania to identify possible avenues for strengthening digital talent and skills in the public sector, in particular regarding the role of leading digital government units/agencies in setting up goals, actions and co-ordination across the public sector (Box 3.15 and Box 3.16). Efforts across OECD countries includes defining frameworks that structure the particular settings for a digital talent and skills approach in the public sector.

Box 3.15. Digital talent and skills in the public sector in Italy

The Digital Skills and Knowledge for Public Administration project (DSKPA) was designed to develop digital proficiency and literacy within the Italian public sector. Demonstrating its dedication to digital evolution, the Italian government incorporated the DSKPA project into its recently approved National Strategy Plan for Digitisation, endorsed by the Ministry for Technological Innovation and Digital Transition.

DSKPA's mission is twofold: to promote digital transformation initiatives and to improve the standard of public services. It offers public servants the opportunity to develop their digital expertise through tailored training programmes, which are set after a uniform assessment of training needs. Additionally, it endorses self-evaluation and skill identification within administrations.

For its implementation, DSKPA comprises three activities. First, it developed a shared and common ground of knowledge and skills within the public sector administrations, covering technological innovation and digitisation issues. Second, the project arranged a digital platform designed for any public administration to assess public servants’ gaps in digital competences. Third, the programme incentivised the reduction in these gaps by supporting the definition and implementation of ad hoc training paths.

Source: EIPA (n.d.[27]), Digital Skills and Knowledge for Public Administration in Italy, https://www.eipa.eu/epsa/digital-skills-and-knowledge-for-public-administration/ (accessed 10 August 2023)

Box 3.16. Digital talent and skills in the public sector in Australia

The Digital Transformation Agency (DTA) supports public sector institutions to develop digital talent and skills. For this purpose, the DTA is implementing a dedicated strategy that comprises a series of actions to attract, keep, and develop staff with specific skills; improve the digital literacy of senior leaders; and make sure existing staff have access to the tools and resources they need to deliver better digital services. Various initiatives have been implemented to meet these needs:

Online Help: Guides and tools are provided to help teams establish and manage digital services.

Digital Service Standard Training: Free training is provided to ensure teams comprehend and adhere to the Digital Service Standard.

Entry-level Programs: For individuals commencing their digital or technical careers in the APS, entry-level programs offer roles like apprenticeships, cadetships, and graduate positions.

Support for Women: Special coaching and mentoring programs, "Women in IT", aim to bolster women's leadership skills and representation in digital governmental roles.

Capability Building: Measures include the Capability Accelerator Program, Digital Marketplace, and other tailored programs to identify skill gaps and provide training.

Agency Partnerships: Collaborations with other agencies to enhance digital services are established, offering mentoring, coaching, and expertise in various areas.

Events and Workshops: Regular events at Canberra and Sydney offices aim to bolster in-house skills, with guest speakers and events focusing on specific areas.

Digital Communities of Practice: These communities connect government workers to discuss ideas, showcase work, and explore best practices in areas like service design and content design.

Source: Digital Transformation Agency (n.d.[28]), Building digital skills across government, https://www.dta.gov.au/our-projects/building-digital-skills-across-government (accessed on 10 August 2023)

OECD countries advancing the development of digital talent and skills in the public sector are also guiding policy decision making by assessing digital skills need across the public sector. Establishing the short-, medium-, and long-term digital skills needs is fundamental to effectively deploy national digital government priorities. National surveys and other similar methods can help define a baseline upon which to measure digital talent and skills progress and target specific actions in a context of limited organisational and financial resources to deploy a more comprehensive strategy (Box 3.18).

Romania is progressing towards assessing the digital skills needed in the public sector as part of the implementation of EU Recovery and Resilience Funds (RRF). Under the lead of the NACS, the study looks at assessing specific digital skills in the country in order to define training programmes for the Romanian public sector (ANFP, 2022[29]). The study assesses the level of digital professional skills in a number of topics including databases, web development, project management tools, and digital tools for teleworking. However, the set of skills assessed and the respective training programmes to be implemented look only at a fraction of the skills needed to support digital government maturity (see Box 3.17). Other skills within the same group that are critical for the implementation for a human-centric government digital transformation such as service design and user research, as well as other core skills on leadership, socio-emotional and user skills are not included in the study and as a result will not be included in training activities led by NACS as part of EU RRF investment.

In this regard, Romania could consider developing a government-wide measurement instrument to assess digital talent and skills needs in the public sector that complements ongoing efforts conducted by NACS by included other core skills group to enable the digital transformation of the Romanian public sector, including leadership, user and socio-emotional skills. This would be particularly relevant considering the expected transformation across different levels and sectors that goes beyond technical implementation of ICT/digital projects (see Box 3.17). The role of ADR and NACS can be relevant to articulate a measurement instrument that informs both digital government and civil service priorities and goals.

Box 3.17. Different skills needed to support digital government maturity

The OECD Framework for Digital Talent and Skills establishes four types of skills needed for governments to advance their digital maturity:

Digital government user skills: 5 areas of core skill needed for all public servants to support digital government maturity, including recognising the potential of digital for transformation, understanding users and their needs, collaborating openly for iterative delivery, trustworthy use of data and technology, and data-driven government.

Digital government socio-emotional skills: achieving digital government maturity involves championing and ensuring a blend of domain specific socio-emotional skills and their associated behaviours. Striking a balance between vision, analysis, diplomacy, agility and protection is essential to the design and delivery of trustworthy and proactive services that put users at their heart.

Digital government professional skills: The digital transformation has disrupted existing professions and created new ones. Digital government maturity is supported by building multi-disciplinary teams that draw from, invest in and acknowledge both digital and non-digital professions.

Digital government leadership skills: The leadership to establish a digitally enabled state draws on wider investment in the general quality of leadership. However, achieving digital government maturity requires leaders to visibly model digital government user skills and actively shape an environment that encourages digital transformation.

Source: OECD (2021[26]), Framework for Digital Talent and Skills in the Public Sector, https://doi.org/10.1787/4e7c3f58-en.

Box 3.18. Assessing digital skills needs in the United Kingdom

The Central Digital Data and Data Office (CDDO) envisions a digitally transformed UK government by 2025, as stated in their "Transforming for a Digital Future Strategy". The core strategy involves providing the necessary training and tools for all civil servants, not just those in digital, data, and technology (DDaT) roles.

CDDO implemented a survey in 2022 to better comprehend the digital skills within the civil service. The findings confirmed the belief among civil servants that digital skills and technology are vital for a modern government. The survey revealed that over 75% of civil servants desire more digital skills training. To address this, the government plans to upskill 90% of senior civil servants, deepen the skills of DDaT professionals, and enhance recruitment standards to align with the DDaT Capability Framework by 2025.

Various initiatives have been rolled out in response to the results of the survey, such as launching core capabilities, hosting digital learning events, partnering with recruitment services, and adjusting the pay framework for competitive salaries.

Source: Central Digital and Data Office (2022[30]), The Civil Service’s digital skills imperative, https://cddo.blog.gov.uk/2022/11/29/the-civil-services-digital-skills-imperative/ (accessed on 10 August 2023)

With the acceleration of the digital transformation across public sector institutions, the Romanian government faces other structural challenges to attract, skill and retain digital talent. Existing remuneration schemes for civil servants provide lower salaries compared to other governments in the EU as well as to the IT industry in the country. While this is a spread issue across OECD member and partner countries, Romania observes specific negative incentives that further constrain public sector capacity to attract professional digital talent and skills. Existing tax systems for the IT sector includes income tax exemption for IT employees from private sector companies22. As a result, most of the digital talent is rapidly absorbed by IT companies, and often recruitment processes for civil servants on digital/IT roles do not receive applicants, creating a serious constraint for the capacity of public sector institutions to implement IT/digital projects. Some of these barriers are overcome by the Civil Service Law23, which allows to provide economic incentives to civil servants working on EU-funded projects including ICT/digital projects.

In the context of a very restrictive organisational environment to attract, retain and promote digital talent from a pecuniary perspective, OECD countries are looking at complementary measures to experiment and overcome some structural challenges that impede developing a digital public workforce. Teleworking arrangements, flexible working hours, promotion schemes or microlearning are actions adopted by some OECD countries to advance their capacity to develop a digitally skilled public workforce which could be jointly explored and piloted by the ADR and NACS to create better conditions for digital talent in the Romanian public sector. Evidence from the fact-finding mission indicates a generalised hesitance to think out of the box and experiment alternative and innovative approaches to improve working conditions for digital professionals that, along with the e-government culture embedded into the Romanian public sector (see next section), do not favour positive talent acquisition and development given the pressing digital government skills needs observed in the country.

In any case, best practices across OECD countries indicates that advancing towards the next generation of digital professionals in the public sector requires clear strategic thinking about the future of the public workforce in the next 5 to 10 years, and building new arrangements in collaborative ways with civil servants to explore jointly needs and possible solutions, as well as piloting, testing, learning and adjusting policies to make sure they remain fit for purpose and are implemented in a feasible context (OECD, 2021[31]).

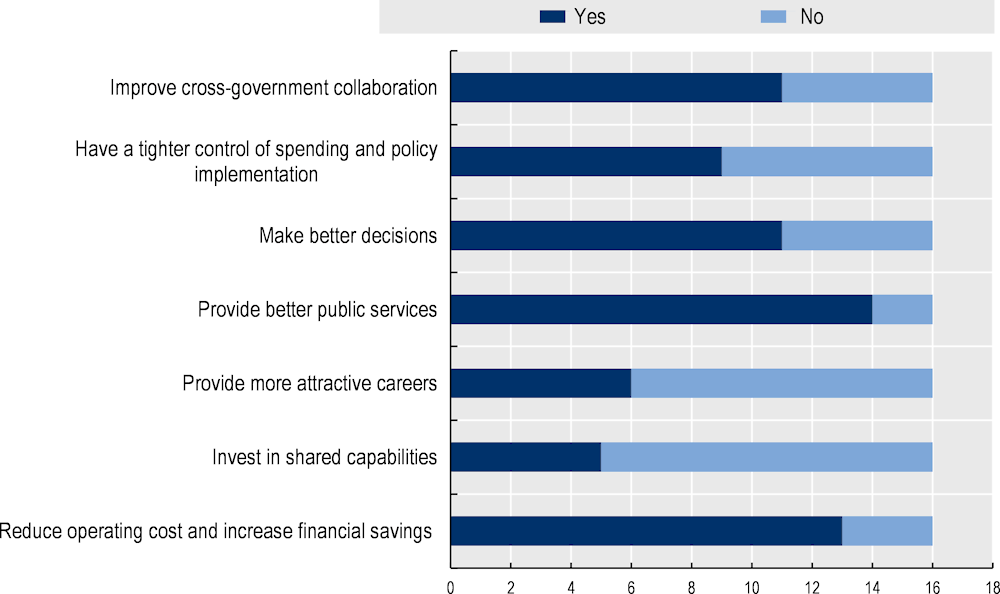

Development of digital talent and skills to support government digital transformation

Among 16 surveyed institutions for this study, 50% declared having at least one activity to support the development of digital talent and skills in the public sector. Similarly, institutions that participated in the survey identified that digital talent and competencies are largely focused to support improvement of government services and reducing operational costs, and to a lesser extent to promote shared capabilities, cross-organisational shared capabilities and collaboration (see Figure 3.4).

Figure 3.4. Goals to achieve with digital talent and skills in the public sector

Note: Graph based on the answer of 16 Romanian public sector institutions to the survey.

Source: OECD Survey of Digital Government in Romania 2022

Within the limited conditions upon which digital talent can be adequately managed in the Romanian government, interviews during the fact-finding mission revealed the need to urgently transform the way civil servants think of digital government and transformation processes in the country. The dominant legalistic culture in the Romanian government system is also reinforced by a technology-led approach when addressing ICT/digital transformation projects. As a consequence, there are cultural challenges in Romania to break down organisational siloes and promote further trust and collaboration across public sector institutions that foster a digital government thinking to integrate government operations and services around users and their needs.