This chapter discusses the results from a pilot in four regions of Italy of a new disability assessment tool that would add the perspective of functioning to the current medically based assessment of disability status in Italy, the WHO Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS). The analysis includes observations from 3 242 individuals participating in the pilot in late 2022 and early 2023 (of which 1 327 in Lombardy region, 1 223 in Campania region, 510 in the Autonomous Province of Trento and 182 in the Autonomous Region Sardinia). Using a statistical approach, the chapter evaluates the performance of the WHODAS questionnaire and concludes that the tool delivers valid, reliable, and scientifically robust distributions of WHODAS scores in all four pilot regions and that social workers in Italy are well place to conduct WHODAS interviews effectively. The report also compares the WHODAS scores of the pilot sample with the corresponding civil invalidity percentages, as pilot participants had been assessed in both ways, and presents options on how the WHODAS questionnaire could be integrated into the current way of assessing civil invalidity in Italy.

Disability, Work and Inclusion in Italy

5. Piloting a new disability assessment in four regions of Italy

Abstract

The assessment of civil invalidity in Italy which determines a person’s rights and entitlements to benefits and services is outdated and incomplete as it is limited to the identification of a medical condition, or impairment, which determines the percentage of civil invalidity without consideration of the person’s actual disability experience and the context in which the person lives. With the passage of the Enabling Act in 2021 (Law 227/2021), Italy has taken a first step towards a reform of its disability policies. The implementing decrees of the Enabling Act, which are currently being drafted and which will also benefit from the contribution of the project presented in this report, go in the direction of providing that the assessment of the disability condition and the revision of its basic assessment processes will be carried out in accordance with the provisions of the Convention of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, also through the adoption of the WHO Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS) – the focus of the pilot project carried out in Italy – within the new basic assessment system provided for by the law.

To prepare the ground for reform, the WHODAS tool was piloted in four regions of Italy – Campania, Lombardy, the Autonomous Region Sardinia (henceforth, Sardinia), and the Autonomous Province of Trento (henceforth, Trentino) – testing the feasibility of the inclusion of functioning information into the current assessment of civil invalidity. WHODAS was developed by the WHO as a tool to identify the kind and nature of problems people are facing in their lives, in alignment with the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). WHODAS has been tested successfully in many countries and different contexts. While Italy can draw on the experiences in other countries, it was also important to test the validity and reliability of the tool in Italy, and the ability of social workers to implement this tool. This chapter summarises the findings of the pilot that took place from October 2022 to April 2023.

5.1. Pilot sample and WHODAS responses and distributions

In the ICF framework, information about categories of Activities and Participation can be collected either from the perspective of capacity (reflecting exclusively the expected ability of a person to perform activities considering their health conditions and impairments) or the perspective of performance (reflecting the actual performance of activities in the real-world environmental circumstances in which a person lives). Information about capacity typically represents the results of a clinical inference or judgment based on medical information, while performance is a true description of what occurs in a person’s life. The two perspectives are therefore very different, although capacity constitutes a determinant of performance.

The ICF understands “disability” to be any level of difficulty in functioning in some domain, from the perspective of performance. The WHO has developed, tested, and recommended WHODAS as a tool that can capture the performance of activities by an individual in his or her daily life and actual environment. The “actual environment” is represented in the ICF in terms of environmental factors that act either as facilitators (e.g. assistive devices, supports, home modifications) or as barriers (e.g. inaccessible houses, streets and public buildings, stigma, and discrimination). The WHODAS questionnaire is structured around six basic functioning domains: cognition, mobility, self-care, getting along with people, life activities, and participation.

The “clinical” version of the WHODAS questionnaire collects information about problems in functioning – i.e. disability – by means of a face‑to-face interview conducted by a trained interviewer who asks a set of standardised questions and, if necessary, follow-up probe questions. WHODAS uses a 5‑level response scale (1 = None, 2 = Mild, 3 = Moderate, 4 = Severe, 5 = Extreme or Cannot do) to rate each question. In extraordinary circumstances (e.g. COVID‑19 lockdown), WHODAS can be administered in a telephone or video interview by the trained professional. Respondents are informed that their answers about each domain of functioning should adopt the perspective of performance, i.e. that they should describe what they do considering the experiences in their daily life and the environmental barriers and facilitators they experience. For the pilot, the 36‑item version of WHODAS was chosen to create a full picture of the disability experienced by the respondent in their everyday life.

5.1.1. Sample characteristics

A total of 3 307 individuals participated in the pilot. The data for 65 individuals were not included in the analysis because of high missing values in their responses. The socio-demographic characteristics of the remaining N = 3 242 individuals are shown in Table 5.1, region by region. The proportion of male participants was below 50% for all four regions. Mean ages differed significantly across regions, with 52.2 years in Campania, 49.8 years in Lombardy, 50.7 years in Sardinia, and 48.8 years in Trentino. An average of about 11 years of education was reported for all regions. Most participants indicated their marital status as being married and most respondents were living independently in the community. The percentage of individuals living in assisted living was highest in Trentino.

Table 5.1. Pilot sample – descriptive statistics for each of the four participating regions

Distribution of the four regional samples across selected socio-demographic characteristics

|

Campania |

Lombardy |

Sardinia |

Trentino |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

N |

1 223 |

1 327 |

182 |

510 |

|

Gender = male (%) |

543 (44.5) |

580 (43.7) |

86 (47.3) |

251 (49.2) |

|

Age – mean (SD) |

52.24 (10.89) |

49.81 (12.25) |

50.71 (13.08) |

48.84 (12.48) |

|

Years of education – mean (SD) |

11.38 (3.81) |

11.26 (3.59) |

11.32 (3.99) |

11.46 (3.29) |

|

Marital status (%) |

||||

|

Never married |

260 (21.3) |

356 (26.8) |

66 (36.3) |

172 (33.7) |

|

Currently married |

745 (61.0) |

630 (47.5) |

76 (41.8) |

222 (43.5) |

|

Separated |

81 (6.6) |

79 (6.0) |

14 (7.7) |

31 (6.1) |

|

Divorced |

64 (5.2) |

124 (9.3) |

12 (6.6) |

39 (7.6) |

|

Widowed |

46 (3.8) |

48 (3.6) |

6 (3.3) |

14 (2.7) |

|

Cohabiting |

26 (2.1) |

90 (6.8) |

8 (4.4) |

32 (6.3) |

|

Living condition (%) |

||||

|

Independent in community |

1 166 (96.6) |

1 206 (90.9) |

182 (100.0) |

425 (83.3) |

|

Assisted living |

41 (3.4) |

120 (9.0) |

0 (0.0) |

80 (15.7) |

|

Hospitalised |

0 (0.0) |

1 (0.1) |

0 (0.0) |

5 (1.0) |

|

Work status (%) |

||||

|

Paid work |

358 (29.3) |

633 (47.7) |

50 (27.5) |

246 (48.2) |

|

Self-employed |

94 (7.7) |

65 (4.9) |

7 (3.8) |

20 (3.9) |

|

Non-paid work |

2 (0.2) |

4 (0.3) |

0 (0.0) |

3 (0.6) |

|

Student |

25 (2.0) |

57 (4.3) |

11 (6.0) |

14 (2.7) |

|

Keeping house |

139 (11.4) |

65 (4.9) |

18 (9.9) |

19 (3.7) |

|

Retired |

64 (5.2) |

76 (5.7) |

14 (7.7) |

23 (4.5) |

|

Unemployed (health reasons) |

209 (17.1) |

299 (22.5) |

60 (33.0) |

131 (25.7) |

|

Unemployed (other reasons) |

324 (26.5) |

123 (9.3) |

21 (11.5) |

38 (7.5) |

|

Other |

7 (0.6) |

4 (0.3) |

1 (0.5) |

16 (3.1) |

Note: The table shows the number of people in the sample in each group while the values in parentheses shows either the corresponding percentage (%) or the corresponding standard deviation (SD).

Source: OECD calculations based on the pilot data.

The data on employment was collected in different manners so that for some of the data collected in Campania detailed information is missing, i.e. it was not possible to determine if unemployment was health-related or not or if the work activity was for an employer or self-employed. Overall, participants indicated having paid work (39.7%) or being unemployed for either health reasons (21.6%) or other reasons (15.6%). The share in paid work was especially high in Lombardy (47.7%) and Trentino (48.2%).

Table 5.2 presents the frequency and percentages of observed ICD‑11 diagnostic chapters, with the caveat that the data on health conditions were collected differently in the four regions. Health condition codes were linked to the closest ICD‑11 chapter; the latest version of WHO’s International Classification of Diseases (ICD‑11). Many people in the data set have more than one diagnosis. If several diagnoses would link to just one ICD chapter, the chapter was reported only once. The situation is different for people with more than one condition from different ICD chapters. Information regarding the priority of different diagnoses was unavailable for most data. It was therefore decided to include in the analyses by health condition all ICD-chapter diagnoses recorded for a person. Such, the total number of conditions presented in Table 5.2 is larger than the total sample as a person with two different conditions would be counted twice. This should not affect the findings by health condition.

Table 5.2. Prevalence of diagnoses by ICD‑11 chapter: Total sample and the participating regions

|

Total sample |

Campania |

Lombardy |

Sardinia |

Trentino |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

ICD-Chapter |

N |

% |

N |

% |

N |

% |

N |

% |

N |

% |

|

1 Infectious diseases |

14 |

0.4 |

1 |

0.09 |

5 |

0.36 |

3 |

1.39 |

5 |

0.6 |

|

2 Neoplasms |

558 |

15.93 |

234 |

22.1 |

229 |

16.4 |

14 |

6.48 |

81 |

9.72 |

|

3 Diseases of the blood |

6 |

0.17 |

2 |

0.19 |

2 |

0.14 |

2 |

0.93 |

0 |

0 |

|

4 Diseases of the immune system |

36 |

1.03 |

4 |

0.38 |

30 |

2.15 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0.24 |

|

5 Endocrine and nutritional diseases |

155 |

4.42 |

59 |

5.58 |

44 |

3.15 |

24 |

11.11 |

28 |

3.36 |

|

6 Mental or behavioural disorders |

535 |

15.27 |

201 |

19 |

162 |

11.6 |

23 |

10.65 |

149 |

17.89 |

|

8 Diseases of the nervous system |

281 |

8.02 |

38 |

3.59 |

139 |

9.96 |

18 |

8.33 |

86 |

10.32 |

|

9 Diseases of the visual system |

87 |

2.48 |

16 |

1.51 |

34 |

2.44 |

5 |

2.31 |

32 |

3.84 |

|

10 Diseases of the ear |

115 |

3.28 |

25 |

2.36 |

57 |

4.08 |

3 |

1.39 |

30 |

3.6 |

|

11 Diseases of the circulatory system |

564 |

16.1 |

188 |

17.77 |

184 |

13.18 |

31 |

14.35 |

161 |

19.33 |

|

12 Diseases of the respiratory system |

150 |

4.28 |

19 |

1.8 |

94 |

6.73 |

2 |

0.93 |

35 |

4.2 |

|

13 Diseases of the digestive system |

138 |

3.94 |

26 |

2.46 |

68 |

4.87 |

12 |

5.56 |

32 |

3.84 |

|

14 Diseases of the skin |

2 |

0.06 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0.93 |

0 |

0 |

|

15 Musculoskeletal diseases |

578 |

16.5 |

191 |

18.05 |

217 |

15.54 |

58 |

26.85 |

112 |

13.45 |

|

16 Genitourinary diseases |

50 |

1.43 |

12 |

1.13 |

21 |

1.5 |

7 |

3.24 |

10 |

1.2 |

|

20 Development anomalies |

14 |

0.4 |

3 |

0.28 |

6 |

0.43 |

2 |

0.93 |

3 |

0.36 |

|

21 Symptoms not elsewhere classified |

51 |

1.46 |

10 |

0.95 |

23 |

1.65 |

6 |

2.78 |

12 |

1.44 |

|

22 Injuries or poisoning |

22 |

0.63 |

4 |

0.38 |

13 |

0.93 |

1 |

0.46 |

4 |

0.48 |

|

24 Factors influencing health status |

147 |

4.2 |

25 |

2.36 |

68 |

4.87 |

3 |

1.39 |

51 |

6.12 |

|

All diseases |

3 503 |

100 |

1 058 |

100 |

1 396 |

100 |

216 |

100 |

833 |

100 |

Note: WHO’s International Classification of Diseases (ICD‑11).

Source: OECD calculations based on the pilot data.

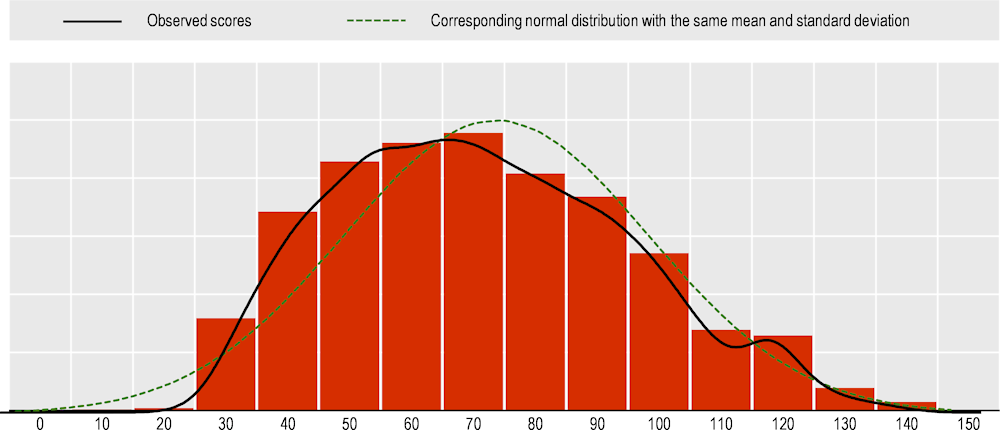

5.1.2. WHODAS response frequencies

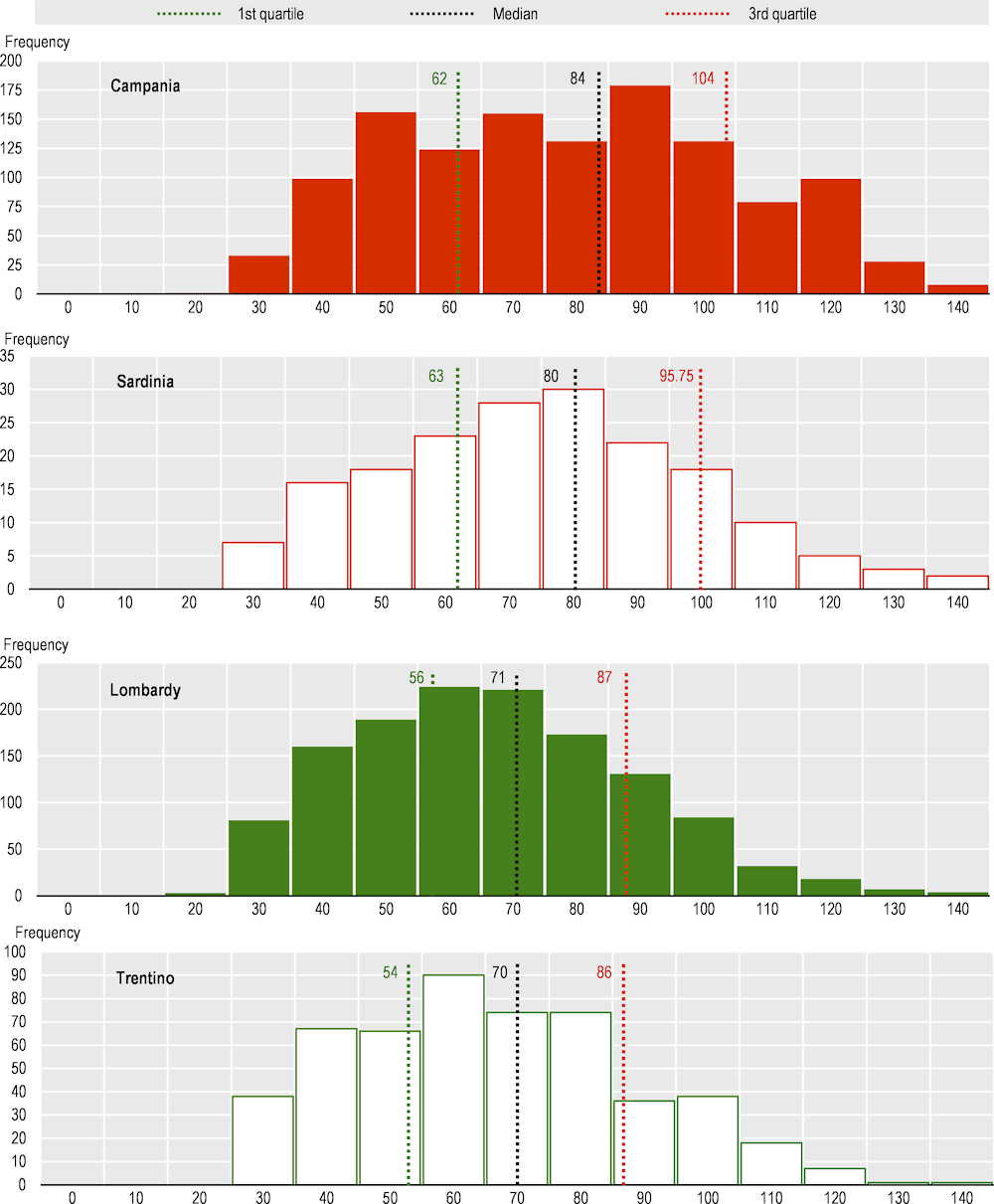

Figure 5.1 visualises how the 36 items of the WHODAS questionnaire have been rated. The percentage of missing values was highest, i.e. about 50%, for items D5.5 to D5.8 that assess difficulties at work (or in school). These four questions have been removed from the construction of the WHODAS score because of the high share of missing values. More than 30% of missing values were also found for two other questions, D5.1 (Taking care of household responsibilities) and D5.2 (Doing most important household tasks), as these two questions were not consistently assessed across all the regions at the start of the pilot.

Figure 5.1. Percentage of ratings by degree of civil disability for each WHODAS item

Note: WHODAS: WHO Disability Assessment Schedule.

Source: OECD calculations based on the pilot data.

5.1.3. WHODAS score distribution

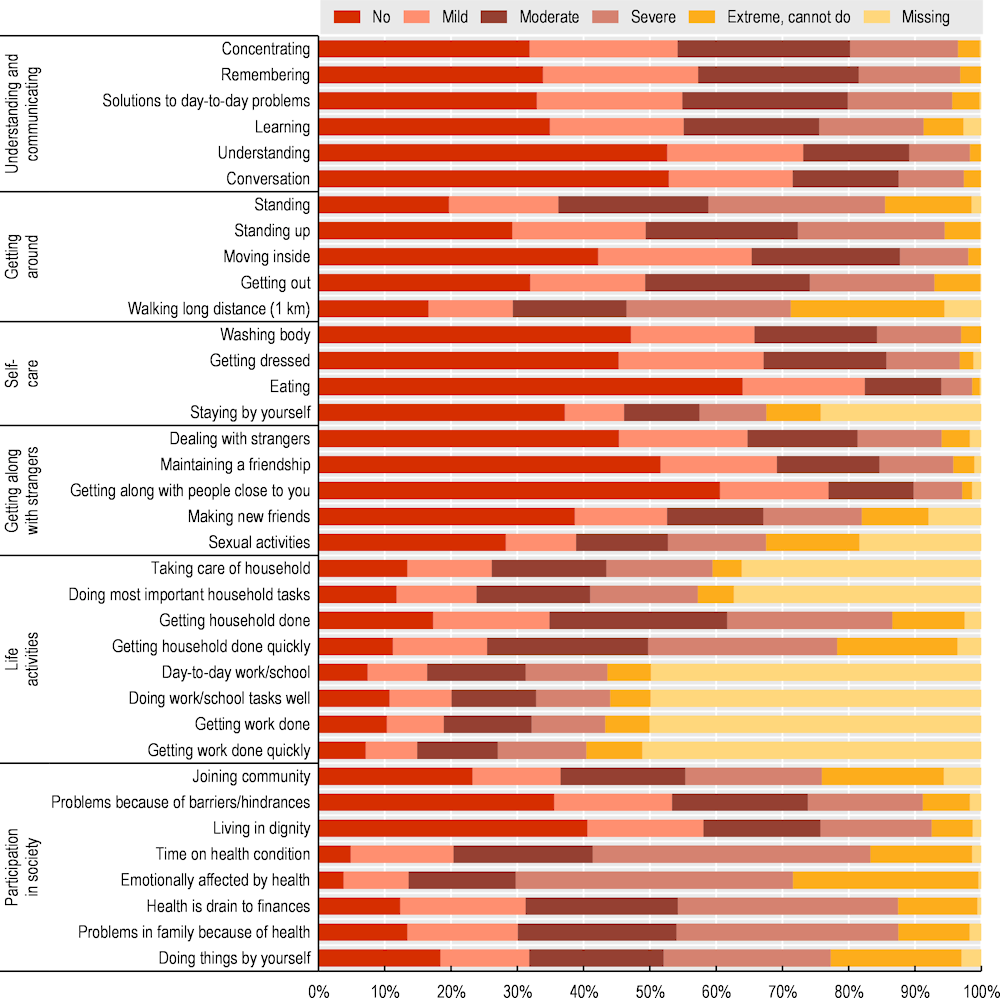

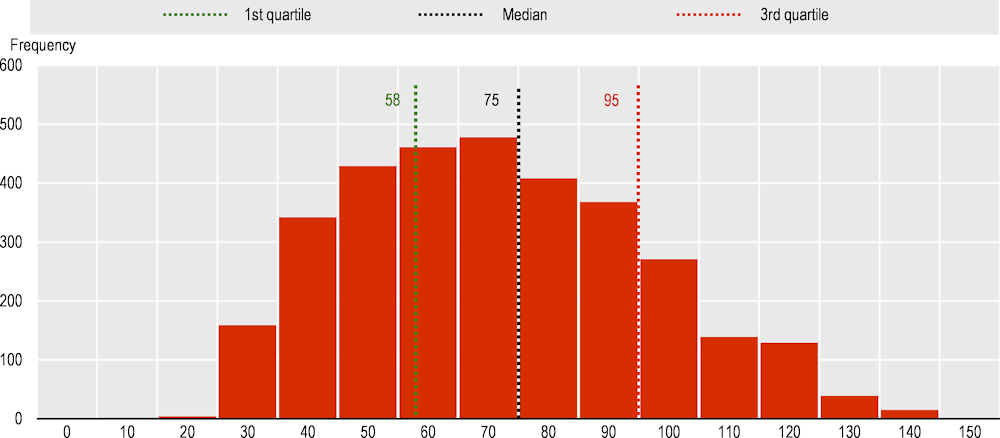

Figure 5.2 shows the distribution of the total raw scores obtained when adding up the 32 items of WHODAS. The total raw WHODAS score ranges from 32 to 160, although a few total scores below 32 are possible as the scores are computed on the raw data with some missing values (less than 20%). Coloured segments in Figure 5.2 indicate the position and value of the , , and quartiles, with a median score ( quartile) of 75. The density lines in Figure 5.3 show the density of the observed scores (black line) and the corresponding normal distribution with the same mean and standard deviation (dotted line). Scores in this sample for Italy are distributed relatively normally, which was a common finding also in other countries where WHODAS was pilot tested (including Bulgaria, Greece, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Seychelles).

Figure 5.2. Raw score distribution of the WHODAS

Note: WHODAS: WHO Disability Assessment Schedule. Items D5.5 to D5.8 are excluded due to number of missing values.

Source: OECD calculations based on the pilot data.

Figure 5.3. Score density: Observed density and random normal density

Note: WHODAS: WHO Disability Assessment Schedule. Items D5.5 to D5.8 are excluded due to number of missing values.

Source: OECD calculations based on the pilot data.

The distributions of the WHODAS raw scores in the four regions that participated in the pilot present some but small differences (Figure 5.4). The highest median WHODAS score (blue dotted line) is found for Campania (Q2 = 84) and the lowest median score in Trentino (Q2 = 70). Higher WHODAS raw scores indicate higher levels of disability among those going through a disability assessment. Otherwise, however, the figures show rather normally distributed WHODAS raw scores for all four participating regions.

Figure 5.4. Raw score distributions of the WHODAS in the four regions

5.2. Psychometric properties of WHODAS applied in Italy

One objective of the assessment pilot was to assess the validity and reliability of the WHODAS instrument in Italy. This is done through Rasch analysis, a statistical method from the field of probabilistic measurement first introduced by the Danish mathematician George Rasch (Rasch, 1960[1]). Rasch analysis is essentially testing several measurement assumptions (Bond, 2015[2]; Tennant and Conaghan, 2007[3]): (1) the targeting of a scale, (2) the model reliability, (3) the ordering of the items’ response options, (4) the absence of correlation between items (so-called Local Item Dependencies, or LID), (5) the fit of the items to the Rasch model, (6) the absence of effects of person factors such as gender and age on item responses (so-called Differential Item Functioning, or DIF), and (7) the unidimensionality of the questionnaire. If these measurement assumptions can be met, a questionnaire can be considered psychometrically sound and derived total scores therefore be considered interval-scaled and operative for measurement.

For a well-performing questionnaire, it is expected that the difficulty of the items is matched to the level of ability of the measured population, i.e, the questionnaire should not be too easy or too difficult. Statistically, good targeting (assumption #1) is achieved if the mean item difficulty and mean person ability are approximating zero. A Person Separation Index (PSI) above 0.8 speaks for a good reliability of the scale and values above 0.9 for very good reliability (assumption #2). The PSI indicates how well the scale can discriminate levels of functioning in the population. The Cronbach , which is typically also reported, is a classical measure of the internal consistency of the data, i.e. how well the items work to describe one construct (Nunnally and Bernstein, 1994[4]). In the presence of disordered response options (assumption #3), an analysis of response probability curves allows to determine which response options cause problems and decide on strategies to aggregate disordered response options. For example, if for an item the response options 2 and 1 appear reversed and indicate that an increase of difficulty cannot be discriminated, the item responses can be recoded so that these options represent only one level of response. LID often occur when items are redundant and measure approximately the same aspect of a construct (assumption #4). The most widely reported statistic for the item dependencies is the correlation matrix of the Rasch residuals (Yen, 1984[5]). Residual correlations above 0.2 are considered as not acceptable and a way to address these local item dependencies, without deleting items, is to aggregate (i.e. to sum up) the correlating items into so-called testlets (Yen, 1993[6]). In item testlets, the ordering of the thresholds is not expected anymore. For good item fit (assumption #5), infit and outfit values are expected to be below 1.2 (Smith, Schumacker and Bush, 1998[7]). The outfit statistic is more sensitive to outliers as the infit statistic. Ideally, items of a questionnaire should be fair and not favour sample subgroups. The analysis of DIF allows to flag exogenous variables, or DIF variables (assumption #6), which conduct to a lack of invariance of the item difficulty (Holland and Wainer, 1993[8]). It is worthwhile to note that a DIF analysis is not always indicating a metric bias but can also simply represent subgroups with unequal underlying ability (Boone, Staver and Yale, 2014[9]). DIF analysis was conducted for age and gender, to determine the items which are sensitive to those external covariates. Finally, a questionnaire should measure only one construct. If a questionnaire shows to have several separate dimensions, the validity of one summary total score is not supported. Unidimensionality (assumption #7) was assessed with a principal component analysis of the Rasch residuals (Smith, 2002[10]). Typically, a first eigenvalue lower than 1.8 is deemed indicative of unidimensionality. Based on simulation analyses, Smith and Miao (1994[11]) suggested considering the size of the second component instead, with values below 1.4 indicative of unidimensionality.

The Rasch analysis for the Italian dataset showed that the scale is multidimensional, with a strong tendency of the items to load (i.e. to correlate with other variables) within WHODAS domains. Only a few items loaded across domains and, similarly, only a few items were free of dependencies. To solve the issues of multidimensionality and local-item dependencies, correlating items were aggregated by accounting for the domain structure of the WHODAS questionnaire. Findings can be summarised as follows:

1. The population included in this analysis presented a very good targeting to the scale.

2. The item reliability was high but also inflated at the beginning of the analysis because of item dependencies (, Cronbach ). Reliability was still found to be good also after the adjustments were made (, Cronbach ).

3. The response thresholds of 23/32 items of the WHODAS questionnaire presented disordering. Locally dependent items can be an explanation for the disordering, as well as a lack of discrimination between the two first response options, i.e. answer categories “None” and “Mild”.

4. The analysis of the residual dependencies showed strong local dependencies among most items of the WHODAS questionnaire, with a tendency of questionnaire items from the same domain to associate. To address these dependencies, items were aggregated considering the domain structure of the tool. The thresholds of the testlets are not expected to be ordered.

5. The item fit is good if the infit and outfit values are below 1.2. Three out of the 32 items showed misfit with infit or outfit above the cut-off: D1.5 (Generally understanding what people say), D6.4 (How much time did you spend on your health condition or its consequences), and D6.6 (How much has your health been a drain on the financial resources of you or your family). After aggregation of the items by domain, all testlets showed good infit and outfit values, below 1.2.

6. The DIF analysis indicated that all WHODAS domains are sensitive to age. Responses to domain 1 (Cognition – Understanding and communicating) and domain 5(1) (Life activities – Taking care of the household) are also affected by the gender of the respondent.

7. The principal component analysis indicated that the items cluster by domains which results in multidimensionality, with a very high eigenvalue of and a eigenvalue of . After adjustments, i.e. aggregation of items by WHODAS domains, the eigenvalue dropped to and the eigenvalue to , indicating unidimensionality according to the defined criteria.

In conclusion, statistical psychometric testing confirmed the validity and reliability of the WHODAS tool in the Italian context. Statistical analysis of the psychometric properties of WHODAS with the data piloted in Italy shows that functioning data collected with WHODAS display robust psychometric properties. It is important to keep in mind that the WHO developed WHODAS explicitly to statistically capture the construct of functioning from the perspective of performance – i.e. the experience of performing activities by a person with an underlying health problem in their everyday life environment. Based on satisfactory psychometric properties, one can confidently conclude that information collected with the WHODAS questionnaire is robust, viable, and relevant and that it validly represents the construct of disability as understood in the ICF and the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD). Including the WHODAS questionnaire into disability status assessment in Italy would therefore (i) significantly strengthen the method of assessment currently in use (which is a medical assessment based on the existence of impairments) and align it with Italy’s general approach to disability; (ii) bring it closer to the ICF and UNCRPD understanding of disability; and (iii) harmonise the approach to assessment with the ICF functioning-based approach used in subsequent individual needs assessments.

5.3. Comparing WHODAS scores and civil invalidity ratings

5.3.1. Meaningful cut-off points

There are no agreed and published cut-offs available for the WHODAS score that would be applicable to a population with diverse health conditions to categorise the severity of their disability. Having established cut-offs would allow to detect individuals with significant disabilities and to reflect and, eventually, reconsider attributed civil invalidity percentages. Some studies report the 90th or 95th percentile of the WHODAS score distribution as being the best cut-off to diagnose severe disability or dysfunctionality in some specific groups, such as post-partum women (Mayrink et al., 2018[12]) or the elderly population (Ferrer et al., 2019[13]). A minimal clinically important difference in scores for the WHODAS has not been established yet (Federici et al., 2016[14]). However, based on several previous and comparable pilot projects conducted by the World Bank using the WHODAS questionnaire, in Greece, Latvia, Lithuania, and Bulgaria, meaningful WHODAS disability cut-off points for the Rasch-based 0‑100 score are suggested as follows:

Score 0‑25: No functioning restrictions (i.e. no difficulties in performance/disability)

Score 26‑40: Moderate functioning restrictions (i.e. moderate difficulties in performance/disability)

Score 41‑60: Severe functioning restrictions (i.e. severe difficulties in performance/disability)

Score 61‑100: Very severe functioning restrictions (i.e. very severe difficulties in performance/disability)

A score of 40 would thus be a central cut-off for determining the presence of a disability and, thus, eligibility for services. In total, the sample presented N = 74 (2.3%) of individuals having no functioning restrictions, N = 972 (30.0%) of individuals with moderate functioning restrictions, N = 2 120 (65.4%) of individuals with severe functioning restrictions, and N = 76 (2.3%) of individuals with very severe functioning restrictions.

Later in this chapter, additional cut-offs are introduced to split the two middle groups in which most people are concentrated – thereby distinguishing lower and higher moderate functioning restrictions (with WHODAS scores of 26‑34 and 35‑40, respectively) as well as lower and higher severe functioning restrictions (with WHODAS scores of 41‑48 and 49‑60, respectively).

The civil invalidity percentages attributed to persons with health problems in Italy, following the assessment, can be divided into different categories in various ways. While there are no cut-off points for a discretionary assessment, entitlement for various benefits and supports suggest the following as a meaningful split:

0‑33%: no invalidity

34‑66%: moderate invalidity, of which

34‑45%: lower moderate invalidity

46‑66%: higher moderate invalidity

67‑99%: severe invalidity, of which

67‑73%: lower severe invalidity

74‑99%: higher severe invalidity

100%: very severe invalidity

In total, the pilot sample presented N = 81 (2.8%) of individuals with no civil invalidity, N = 1 129 (38.8%) of individuals with moderate civil invalidity, N = 1 076 (37%) with severe civil invalidity, and N = 623 (21.4%) of individuals with very severe civil invalidity rated as 100%. There were N = 333 (10.3%) individuals in the data set with no reported civil invalidity percentage. The different levels of invalidity are key to obtaining supports from Italy’s social protection system. For example, with a civil invalidity percentage above 46% individuals can request employment support, with more than 67% prostheses are provided free of charge, and with more than 74% people can receive a non-contributory disability allowance.

5.3.2. Sample characteristics according to cut-off points

Table 5.3 presents the socio-demographic characteristics of the sample disaggregated by level of disability based on the WHODAS score. With 68.9%, the percentage of men was higher in the group with no disability and close to or below 50% otherwise. There is a statistically significant increase in mean age (p-value < 0.001) across disability levels from 45.7 years with no disability to 53.5 years with very severe disability. The average number of years of education decreases significantly with increasing disability status (p-value < 0.001) from about 12 years with no disability to about 11 years with very severe disability. With regard to the living situation, 77.3% of participants with very severe disability lived independently in the community, with shares above 90% for all other groups. The percentage of persons in paid work decreased from 56.8% in the group with no disability to 21.1% for those with very severe disability.

Table 5.3. Sample descriptive statistics by disability severity based on the WHODAS questionnaire

|

No |

Moderate |

Severe |

Very severe |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

N |

74 |

972 |

2 120 |

76 |

|

Gender = male (%) |

51 (68.9) |

491 (50.5) |

884 (41.8) |

34 (44.7) |

|

Age – mean (SD) |

45.74 (15.98) |

49.32 (12.35) |

51.29 (11.52) |

53.45 (9.53) |

|

Years of education – mean (SD) |

12.05 (3.54) |

11.75 (3.67) |

11.14 (3.64) |

10.96 (3.42) |

|

Living condition (%) |

||||

|

Independent in the community |

73 (98.6) |

936 (96.6) |

1912 (90.7) |

58 (77.3) |

|

Assisted living |

1 (1.4) |

33 (3.4) |

190 (9.0) |

17 (22.7) |

|

Hospitalised |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

6 (0.3) |

0 (0.0) |

|

Marital status (%) |

||||

|

Never married |

31 (41.9) |

273 (28.1) |

531 (25.0) |

19 (25.0) |

|

Currently married |

33 (44.6) |

506 (52.1) |

1 094 (51.6) |

40 (52.6) |

|

Separated |

4 (5.4) |

54 (5.6) |

142 (6.7) |

5 (6.6) |

|

Divorced |

3 (4.1) |

58 (6.0) |

170 (8.0) |

8 (10.5) |

|

Widowed |

0 (0.0) |

27 (2.8) |

86 (4.1) |

1 (1.3) |

|

Cohabiting |

3 (4.1) |

53 (5.5) |

97 (4.6) |

3 (3.9) |

|

Work status (%) |

||||

|

Paid work |

42 (56.8) |

474 (48.8) |

755 (35.6) |

16 (21.1) |

|

Self-employed |

7 (9.5) |

71 (7.3) |

107 (5.1) |

1 (1.3) |

|

Non-paid work |

0 (0.0) |

3 (0.3) |

6 (0.3) |

0 (0.0) |

|

Student |

5 (6.8) |

46 (4.7) |

56 (2.6) |

0 (0.0) |

|

Keeping house |

1 (1.4) |

68 (7.0) |

167 (7.9) |

5 (6.6) |

|

Retired |

8 (10.8) |

38 (3.9) |

119 (5.6) |

12 (15.8) |

|

Unemployed (health reasons) |

4 (5.4) |

122 (12.6) |

540 (25.5) |

33 (43.4) |

|

Unemployed (other reasons) |

7 (9.5) |

142 (14.6) |

349 (16.5) |

8 (10.5) |

|

Other |

0 (0.0) |

8 (0.8) |

19 (0.9) |

1 (1.3) |

Note: WHODAS: WHO Disability Assessment Schedule.

Source: OECD calculations based on the pilot data.

Table 5.4 presents the socio-demographic characteristics of the sample disaggregated by the level of civil invalidity, following the above‑proposed cut-off categories. The percentage of men is higher and above 50% only in the group of persons with no civil invalidity. Again, there is a statistically significant increase in the mean age (p-value < 0.001) across degrees of civil invalidity, from 45.2 years in the group with no invalidity to 52.9 years in the group with very severe civil invalidity. The average number of years of education is slightly above 11 years across all invalidity levels. The share of people living independently in the community is about 85.2% among those with very severe invalidity and above 90% for the other groups. Finally, the percentage of persons in paid work decreases from about 44.4% in the group of persons with no or moderate civil invalidity to 32.4% in the group of persons with very severe disability.

Table 5.4. Sample descriptive statistics by impairment severity based on assessment of civil invalidity

|

No |

Moderate |

Severe |

Very severe |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

N |

81 |

1 129 |

1 076 |

623 |

|

Gender = male (%) |

44 (54.3) |

498 (44.1) |

507 (47.2) |

271 (43.6) |

|

Age – mean (SD) |

45.16 (14.20) |

48.94 (12.38) |

51.69 (11.59) |

52.87 (10.72) |

|

Years of education – mean (SD) |

11.41 (3.22) |

11.37 (3.61) |

11.27 (3.78) |

11.52 (3.64) |

|

Living Condition (%) |

||||

|

Independent in the community |

76 (93.8) |

1 074 (95.8) |

996 (93.1) |

529 (85.2) |

|

Assisted living |

5 (6.2) |

45 (4.0) |

73 (6.8) |

89 (14.3) |

|

Hospitalised |

0 (0.0) |

2 (0.2) |

1 (0.1) |

3 (0.5) |

|

Marital Status (%) |

||||

|

Never married |

28 (34.6) |

301 (26.7) |

277 (25.7) |

156 (25.0) |

|

Currently married |

35 (43.2) |

583 (51.7) |

557 (51.8) |

326 (52.3) |

|

Separated |

2 (2.5) |

79 (7.0) |

73 (6.8) |

39 (6.3) |

|

Divorced |

9 (11.1) |

79 (7.0) |

72 (6.7) |

47 (7.5) |

|

Widowed |

1 (1.2) |

32 (2.8) |

47 (4.4) |

24 (3.9) |

|

Cohabiting |

6 (7.4) |

54 (4.8) |

50 (4.6) |

31 (5.0) |

|

Work Status (%) |

||||

|

Paid work |

36 (44.4) |

509 (45.1) |

397 (36.9) |

202 (32.4) |

|

Self-employed |

6 (7.4) |

69 (6.1) |

58 (5.4) |

37 (5.9) |

|

Non-paid work |

1 (1.2) |

5 (0.4) |

3 (0.3) |

0 (0.0) |

|

Student |

7 (8.6) |

50 (4.4) |

24 (2.2) |

15 (2.4) |

|

Keeping house |

5 (6.2) |

87 (7.7) |

78 (7.3) |

44 (7.1) |

|

Retired |

2 (2.5) |

23 (2.0) |

67 (6.2) |

67 (10.8) |

|

Unemployed (health reasons) |

14 (17.3) |

204 (18.1) |

238 (22.1) |

163 (26.2) |

|

Unemployed (other reasons) |

10 (12.3) |

171 (15.1) |

200 (18.6) |

88 (14.1) |

|

Other |

0 (0.0) |

11 (1.0) |

10 (0.9) |

7 (1.1) |

Source: OECD calculations based on the pilot data.

5.3.3. Pathologies, WHODAS scores and civil invalidity ratings

Table 5.5 presents the mean WHODAS score, on the 0‑100 scale, disaggregated by health condition, and the distribution of the population across ICD‑11 chapters. Individuals with “Symptoms, signs or clinical findings not classified elsewhere” presented the highest mean WHODAS score of 46.66. The least disabling conditions as measured by WHODAS are development anomalies with a mean score of 40.8. Among the four most frequent pathologies, the category “mental, behavioural or neurodevelopmental disorders” has the highest mean WHODAS score (44.95) while the other three main impairments (neoplasms, circulatory system diseases, and musculoskeletal system diseases) all have mean scores around 43.

Table 5.5. Frequency of ICD chapters and mean of the corresponding WHODAS score

|

N |

Mean (SD) |

|

|---|---|---|

|

1 Certain infectious or parasitic diseases |

14 (0.4%) |

43.4 (9.75) |

|

2 Neoplasms |

558 (15.93%) |

43.44 (8.08) |

|

3 Diseases of the blood or blood-forming organs |

6 (0.17%) |

48.47 (8.07) |

|

4 Diseases of the immune system |

36 (1.03%) |

45.13 (7.77) |

|

5 Endocrine, nutritional or metabolic diseases |

155 (4.42%) |

43.85 (7.67) |

|

6 Mental, behavioural or neurodevelopmental disorders |

535 (15.27%) |

44.95 (7.99) |

|

8 Diseases of the nervous system |

281 (8.02%) |

45.09 (8.34) |

|

9 Diseases of the visual system |

87 (2.48%) |

41.49 (8.56) |

|

10 Diseases of the ear or mastoid process |

115 (3.28%) |

42.02 (8.07) |

|

11 Diseases of the circulatory system |

564 (16.1%) |

42.65 (7.94) |

|

12 Diseases of the respiratory system |

150 (4.28%) |

41.38 (9.07) |

|

13 Diseases of the digestive system |

138 (3.94%) |

43.16 (7.22) |

|

14 Diseases of the skin |

2 (0.06%) |

43.12 (10.7) |

|

15 Diseases of the musculoskeletal system and diseases of connective tissue |

578 (16.5%) |

43.51 (7.13) |

|

16 Diseases of the genitourinary system |

50 (1.43%) |

41.64 (8.66) |

|

20 Development anomalies |

14 (0.4%) |

40.80 (8.00) |

|

21 Symptoms, signs or clinical findings, not elsewhere classified |

51 (1.46%) |

46.66 (11.39) |

|

22 Injury, poisoning, or other consequences of external causes |

22 (0.63%) |

42.87 (5.99) |

Note: WHO’s International Classification of Diseases (ICD‑11). WHODAS: WHO Disability Assessment Schedule.

Source: OECD calculations based on the pilot data.

Table 5.6 disaggregates the sample by pathology and degree of civil invalidity. By and large, the results show that mean WHODAS scores tend to increase with the invalidity degree for most pathologies although the results must be interpreted with caution, due to the small number of cases in the group with no invalidity (N = 81). It is not the same condition that consistently receives the highest WHODAS rating across the different civil invalidity degree groups. Looking at the four main pathologies only, for which the sample size is large enough to draw reliable conclusions, the following can be observed:

Diseases of the musculoskeletal system are the dominant pathology among people with a moderate level of civil invalidity (25.5% of those with degrees 34‑66%). For those diseases, mean WHODAS scores clearly and gradually increase with the invalidity degree, from around 38.1 to 49.8.

Neoplasms are the dominant pathology among people with very severe levels of invalidity (38.5% of those with a degree of 100%). Mean WHODAS scores are lower than for the other main diseases, at all invalidity levels with degrees above 33%.

Diseases of the circulatory system are particularly frequent in the two middle invalidity categories, moderate and severe disability (i.e. degree 34‑99%). Mean WHODAS scores generally lie between those for neoplasms and for diseases of the musculoskeletal system.

The percentage of mental, behavioural, or neurodevelopmental disorders increases slightly with an increasing invalidity degree, with a high WHODAS mean compared to the other main diseases.

The mean WHODAS scores increase with the invalidity degree for all four main pathologies.

Table 5.6. Frequency of ICD chapters by civil invalidity degree and mean of the corresponding WHODAS score

|

No invalidity (0‑33%) |

Moderate invalidity (34‑66%) |

Severe invalidity (67‑99%) |

Very severe invalidity (100%) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

N |

mean (SD) |

N |

Mean (SD) |

N |

Mean (SD) |

N |

Mean (SD) |

|

|

1 Certain infectious or parasitic diseases |

1 (1.25%) |

43.67 ( –) |

5 (0.4%) |

39.87 (13.52) |

6 (0.43%) |

43.87 (6.99) |

2 (0.27%) |

50.65 (9.53) |

|

2 Neoplasms |

5 (6.25%) |

42.09 (18.48) |

74 (5.86%) |

38.7 (7.75) |

190 (13.58%) |

41.61 (7.35) |

285 (38.46%) |

45.91 (7.56) |

|

3 Diseases of the blood or blood-forming organs |

1 (0.08%) |

44.41 ( –) |

2 (0.14%) |

42.64 (1.8) |

2 (0.27%) |

50.53 (9.7) |

||

|

4 Diseases of the immune system |

1 (1.25%) |

51.6 ( –) |

14 (1.11%) |

41.74 (7.58) |

16 (1.14%) |

44.69 (4.91) |

5 (0.67%) |

54.73 (9.18) |

|

5 Endocrine, nutritional or metabolic diseases |

2 (2.5%) |

32.31 (11.66) |

44 (3.48%) |

40.49 (8.85) |

77 (5.5%) |

44.33 (6.67) |

30 (4.05%) |

48.38 (5.19) |

|

6 Mental, behavioural or neurodevelopmental disorders |

8 (10%) |

37.72 (11.26) |

169 (13.38%) |

42.79 (7.06) |

258 (18.44%) |

44.92 (7.98) |

99 (13.36%) |

49.34 (7.37) |

|

8 Diseases of the nervous system |

7 (8.75%) |

39.03 (9.9) |

87 (6.89%) |

40.59 (7.48) |

101 (7.22%) |

45.03 (7.52) |

85 (11.47%) |

50.27 (7) |

|

9 Diseases of the visual system |

5 (6.25%) |

32.28 (14.01) |

35 (2.77%) |

40.73 (8.42) |

37(2.64%) |

43.69 (7.66) |

10 (1.35%) |

40.62 (6.31) |

|

10 Diseases of the ear or mastoid process |

9 (11.25%) |

40.8 (7.17) |

64 (5.07%) |

41.1 (7.94) |

34 (2.43%) |

43.97 (8.14) |

8 (1.08%) |

42.48 (9.6) |

|

11 Diseases of the circulatory system |

6 (7.5%) |

42.14 (6.63) |

220 (17.42%) |

40.81 (7.42) |

269 (19.23%) |

42.98 (7.76) |

65 (8.77%) |

47.04 (8.48) |

|

12 Diseases of the respiratory system |

2 (2.5%) |

39.82 (1.03) |

86 (6.81%) |

39.61 (10.05) |

53 (3.79%) |

43.31 (7.19) |

9 (1.21%) |

47.24 (4.91) |

|

13 Diseases of the digestive system |

2 (2.5%) |

49.76 (2.59) |

43 (3.4%) |

40.73 (6.43) |

68 (4.86%) |

42.32 (6.88) |

25 (3.37%) |

49.1 (6.32) |

|

14 Diseases of the skin |

1 (0.07%) |

50.69 ( –) |

1 (0.13%) |

35.55 ( –) |

||||

|

15 Diseases of the musculoskeletal system |

20 (25%) |

38.05 (5.72) |

322 (25.49%) |

42.3 (7.07) |

183 (13.08%) |

44.57 (6.45) |

47 (6.34%) |

49.75 (6.16) |

|

16 Diseases of the genitourinary system |

1 (1.25%) |

35.97 ( –) |

14 (1.11%) |

39.7 (5.58) |

19 (1.36%) |

38.79 (7.86) |

16 (2.16%) |

47.08 (9.82) |

|

20 Development anomalies |

5 (0.4%) |

37.69 (6.71) |

6 (0.43%) |

39.95 (6.4) |

3 (0.4%) |

47.66 (11.25) |

||

|

21 Symptoms not elsewhere classified |

3 (3.75%) |

27.98 (11.49) |

9 (0.71%) |

38.74 (7.04) |

19 (1.36%) |

45.95 (7.46) |

20 (2.7%) |

53.69 (10.79) |

|

22 Injury, poisoning or other external causes |

2 (2.5%) |

42.87 (2.88) |

9 (0.71%) |

44.01 (6.94) |

7 (0.5%) |

38.72 (4.65) |

3 (0.4%) |

47.1 (1.88) |

Note: WHO’s International Classification of Diseases (ICD‑11). WHODAS: WHO Disability Assessment Schedule.

Source: OECD calculations based on the pilot data.

Table 5.7 looks at the mean WHODAS score and the mean civil invalidity percentage per ICD chapter, comparing the situation when the linked health condition chapter appeared as standalone diagnostical information versus when it was reported in addition to other health condition chapters; thereby comparing cases of single morbidity with cases of comorbidity. The average WHODAS score per ICD chapter hardly changes whether it is a single diagnosis or part of multiple diagnoses. In contrast, the average civil invalidity percentage is in many cases higher when a person is diagnosed with multiple conditions. In other words, the WHODAS score per ICD chapter varies significantly less than the civil invalidity percentage: it appears that co-morbidity has an influence on the civil invalidity percentage but not on the WHODAS score. The data do not allow an interpretation of this finding but the discretionary freedom in the civil invalidity assessment could play a role, i.e. assessors perceiving people with co-morbidity as having a more severe disability – a finding that is not corroborated by the corresponding WHODAS scores.

Table 5.7. Mean and standard deviation of the WHODAS score and the civil invalidity percentage per ICD chapter: comparing results for single diagnoses with cases of co-morbidity

|

Number ICD chapter linked = 1 (i.e. single diagnosis) |

Number ICD chapter linked > 1 (i.e. multiple diagnoses) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

N |

WHODAS score mean (SD) |

Civil invalidity percentage mean (SD) |

N |

WHODAS score mean (SD) |

Civil invalidity percentage mean (SD) |

|

|

1 Certain infectious or parasitic diseases |

3 |

44.49 (0.76) |

30 (27.84) |

6 |

37.16 (11.01) |

70.17 (8.68) |

|

2 Neoplasms |

430 |

43.78 (8.09) |

86.38 (18.93) |

58 |

41.51 (8.31) |

72.26 (20.05) |

|

3 Diseases of the blood and its organs |

3 |

48.57 (7.64) |

71 (27.22) |

2 |

51.88 (11.62) |

100 (NA) |

|

4 Diseases of the immune system |

12 |

40.85 (9.04) |

60.33 (17.17) |

15 |

47.37 (6.97) |

74.53 (17.83) |

|

5 Endocrine or nutritional diseases |

67 |

42.91 (7.85) |

67.38 (19.89) |

52 |

44.93 (6.97) |

76.15 (15.95) |

|

6 Mental or behavioural disorders |

316 |

44.47 (8.09) |

68.61 (19.68) |

97 |

45.22 (7.61) |

70.94 (21.06) |

|

8 Diseases of the nervous system |

117 |

44.36 (9.43) |

71.62 (27.01) |

71 |

46.76 (7.67) |

74.06 (20.83) |

|

9 Diseases of the visual system |

30 |

42.28 (10.32) |

51.1 (26.68) |

48 |

40.63 (7.94) |

70.08 (22.25) |

|

10 Diseases of the ear or mastoid process |

30 |

40.73 (8.54) |

34.6 (23.2) |

65 |

43.13 (7) |

65.14 (19.31) |

|

11 Diseases of the circulatory system |

236 |

41.71 (8.45) |

63.13 (17.57) |

186 |

43.56 (7.17) |

72.55 (18.4) |

|

12 Diseases of the respiratory system |

55 |

39.81 (11.37) |

48.15 (17.74) |

57 |

43.11 (7.69) |

66.91 (14.56) |

|

13 Diseases of the digestive system |

57 |

42.61 (7.67) |

66.81 (20.39) |

46 |

43.39 (6.62) |

74.11 (22.28) |

|

15 Diseases of the musculoskeletal system |

299 |

43.08 (7.61) |

54.37 (20.82) |

177 |

44.42 (6.56) |

68.04 (19.26) |

|

16 Diseases of the genitourinary system |

23 |

40.96 (9.74) |

72.3 (26.43) |

19 |

44.02 (6.73) |

75.05 (22.96) |

|

20 Development anomalies |

4 |

40.33 (5.34) |

58 (7.26) |

4 |

41.26 (5.55) |

59.75 (16.56) |

|

21 Symptoms not elsewhere classified |

21 |

47.78 (12.92) |

68.05 (34.27) |

19 |

46.35 (11.1) |

77.63 (16.56) |

|

22 Injury, poisoning, other external causes |

7 |

42.79 (8.29) |

49.86 (36.97) |

13 |

42.41 (5.14) |

68.5 (18.6) |

|

24 Factors influencing health status or contact with health services |

58 |

42.4 (6.58) |

57.05 (23.5) |

51 |

44.44 (8.31) |

71 (23.61) |

Note: WHO’s International Classification of Diseases (ICD‑11). WHODAS: WHO Disability Assessment Schedule.

Source: OECD calculations based on the pilot data.

5.3.4. Comparing WHODAS scores and civil invalidity ratings

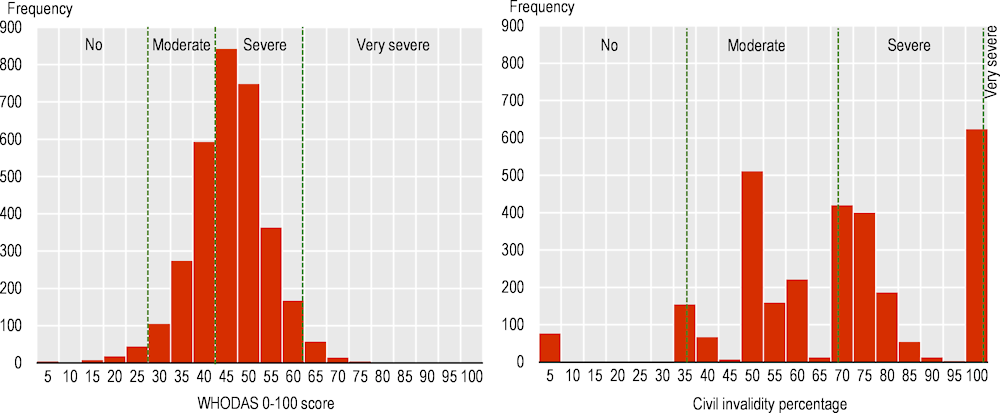

The following figures pursue the comparison between the disability score based on the WHODAS questionnaire and the result of the civil invalidity assessment. Figure 5.5 looks at the distribution of WHODAS scores against the distribution of civil invalidity percentages. While WHODAS disability scores are distributed normally around a mean of 43.2, with a standard deviation of 8.5, civil invalidity percentages seem to be distributed erratically, with higher frequencies at distinct locations on the continuum linked with critical cut-offs for eligibility for specific social benefits and services. The discretionary method of assigning invalidity percentages with limited guidelines and standards might explain the concentration at the cut-offs. In practice, this turns the invalidity scale into an ordinal scale with just a few possible outcomes.

Figure 5.5. The pilot reveals large differences between assessing disability experience (WHODAS score) and impairment (civil invalidity percentage)

Note: WHODAS: WHO Disability Assessment Schedule.

Source: OECD calculations based on the pilot data.

Table 5.8 shows the four civil invalidity groups disaggregated by WHODAS disability groups. In interpreting these findings, it is important to keep in mind that a moderate civil invalidity level should not necessarily be understood to be equal to a moderate disability level. These are two different perspectives, correlated only modestly: WHODAS measures lived experience of disability in the person’s everyday environment; civil invalidity assesses disability based on the person’s impairment (medical approach). The table shows that the number of individuals that fall in opposite severity groups is negligible: there is only one person with a very severe WHODAS disability but no civil invalidity and no one with very severe civil invalidity and no WHODAS disability. However, less extreme seemingly contradictory cases are more frequent: there are, for example, 94 persons with very severe civil invalidity and only moderate WHODAS disability. Likewise, the data include 40 persons with severe WHODAS disability but no civil invalidity.

Table 5.8. Frequencies of civil invalidity degree groups by WHODAS disability group

|

Civil invalidity degree groups |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

No |

Moderate |

Severe |

Very severe |

Missing data |

||

|

WHODAS disability groups |

No |

10 (0.31%) |

39 (1.2%) |

14 (0.43%) |

0 (0%) |

11 (0.34%) |

|

Moderate |

30 (0.93%) |

434 (13.39%) |

298 (9.19%) |

94 (2.9%) |

116 (3.58%) |

|

|

Severe |

40 (1.23%) |

646 (19.93%) |

754 (23.26%) |

481 (14.84%) |

199 (6.14%) |

|

|

Very severe |

1 (0.03%) |

10 (0.31%) |

10 (0.31%) |

48 (1.48%) |

7 (0.22%) |

|

|

Missing data |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

|

Note: WHODAS: WHO Disability Assessment Schedule.

Source: OECD calculations based on the pilot data.

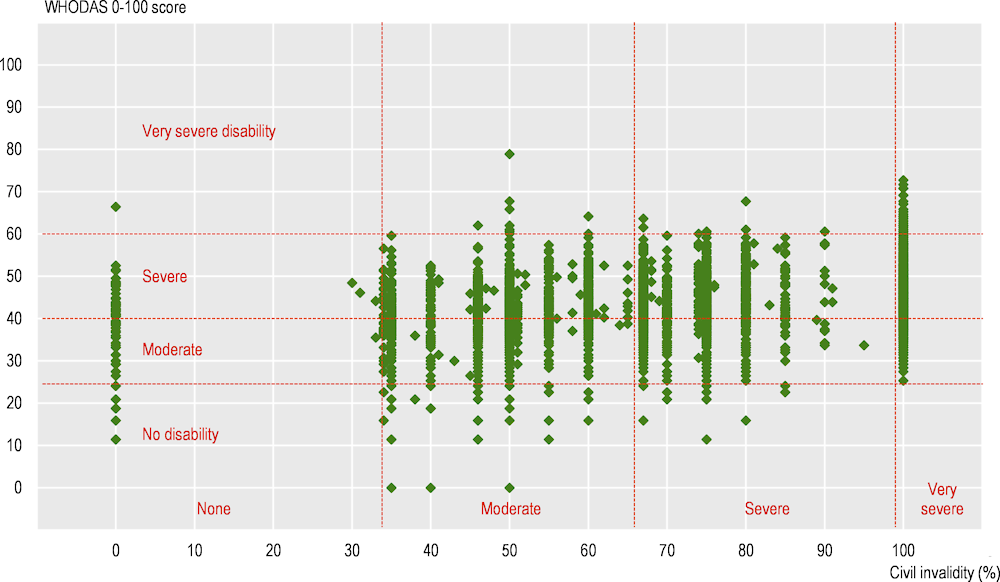

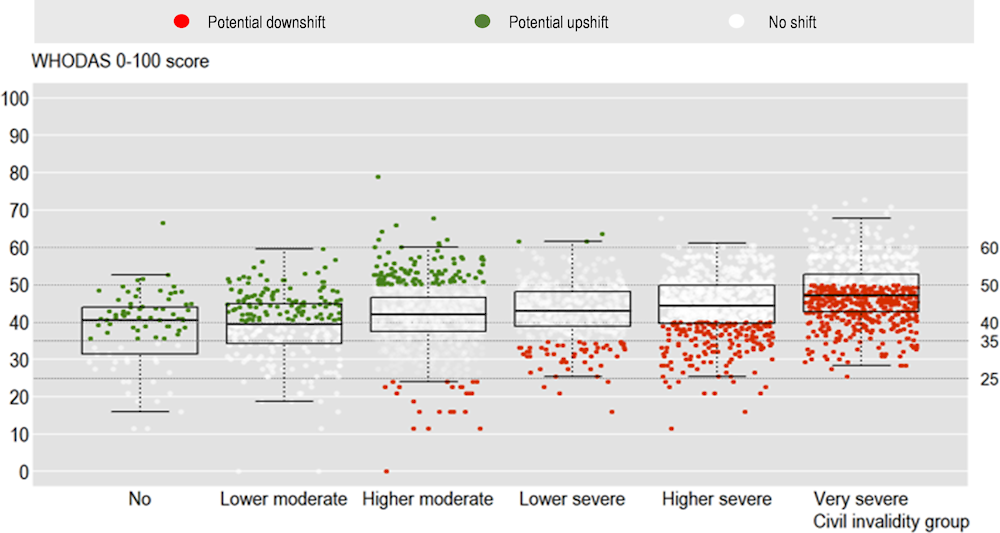

Figure 5.6 also compares the distribution of individual civil invalidity percentages and WHODAS scores. The figure shows the full distribution of data points for the WHODAS score (y-axis) and the civil invalidity percentage (x-axis). Horizontal lines represent the cut-offs for the WHODAS score, from no disability to moderate, severe, and very severe disability, and vertical lines represent the cut-offs for the civil invalidity percentage (again, no, moderate, severe, and very severe). The two scores show a positive correlation but only at a very moderate level (R = 0.33). This is expected because disability cannot be inferred from medical conditions or impairment only: two individuals with the same medical diagnosis will be assigned the same percentage of disability based on medical criteria for the assessment. However, they may experience different levels of disability (functioning limitation and participation restrictions or performance in the ICF disability understanding) depending on their environment.

Figure 5.6. WHODAS score distributions at respective civil invalidity cut-off

Note: WHODAS: WHO Disability Assessment Schedule.

Source: OECD calculations based on the pilot data.

Some notable exceptions can be observed on the plot, such as individuals having 0% of civil invalidity while reporting moderate to very severe disability according to the WHODAS questionnaire looking at their functioning levels across different life domains. Similarly, some individuals with a civil invalidity percentage above 66% (i.e. with severe or very severe invalidity) are found not to have any disability based on their WHODAS score.

5.4. Including functioning elements into the assessment of civil invalidity

5.4.1. General considerations on the inclusion of functioning

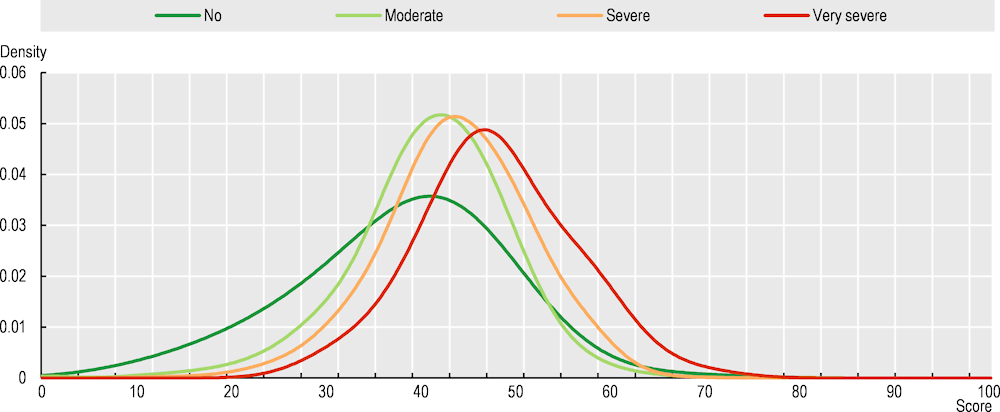

WHODAS functioning scores by current levels of civil invalidity demonstrate that medical assessment alone does not differentiate well between different levels of disability, also suggesting rather low reliability and precision of the civil invalidity ratings in Italy today. Figure 5.7 shows the density lines for the WHODAS scores for the four levels of civil invalidity. While WHODAS scores for very severe functioning restrictions stand out at least a bit (red line), the difference between severe and moderate level of civil invalidity (orange and light green line, respectively) appears to be very small. These density lines suggest the presence of both false positives (cases with high invalidity percentage and low WHODAS score) and false negatives (cases with low invalidity percentage and high WHODAS score). Also, a more accurate assessment would show the density line of the group with no or very low level of civil invalidity (dark green line) positioned more towards the left-hand side of the figure. Again, this suggests that the medical information alone may misrepresent the true extent of individual disability experienced in daily life.

Figure 5.7. WHODAS-score density lines by percentage of civil invalidity (four categories)

Note: WHODAS: WHO Disability Assessment Schedule.

Source: OECD calculations based on the pilot data.

The results in Figure 5.7 come as no surprise as WHODAS was designed explicitly to assess so-called whole‑person disability, while the medical approach to assessing disability used in Italy does not directly assess disability but infers disability based on the underlying health condition or impairment. Sometimes there is a close correlation between the severity of health conditions and the severity of resulting disability; but sometimes there is no such correlation. The latter is best seen in the case of mental health problems where the impact of the person’s environment may greatly increase the impact of the experience of, say, depression. This is the basic validity problem with medically based disability assessment. As pointed out above, although the presence of a health condition and associated impairment is a precondition for disability, inferring the level of disability from the presence of the underlying health condition is scientifically problematic. The level of disability that an individual experiences, as the ICF argues, is determined by the interaction between the person’s health condition and associated impairments and the environment in which the person lives. WHODAS was designed to directly capture this disability experience while assessment of disability based solely on medical grounds cannot do so validly or reliably.

5.4.2. Options for including functioning into civil invalidity assessment in Italy

The WHODAS pilot in Italy has shown that it performs well in capturing the actual experience of disability. The question is how best to include the functioning information captured by WHODAS in the system of disability status assessment in Italy. Medical information will remain relevant to disability assessment; the ICF makes it clear that without an underlying health condition and associated impairments, disability does not exist. Information about health status provides the basis for identifying specific physical and mental dimensions of activities and areas of participation vulnerable to disability, which can then be directly confirmed by the findings received from the WHODAS questionnaire. Medical information provides essential guidance on the medium and long-term trajectory of disability that the individual will experience, including whether the person faces a progressive decline in health capacity resulting in more and more disability, or the reverse, a progressive improvement. While medical information remains an essential component of disability assessment, the medical review must also change with better standardisation and methodological guidelines and possibly using the ICF body functions and body structures.

As medical information is essential, this section of the report discusses possible options for combining medical and functioning information in the assessment of disability in Italy – rather than replacing the current medical approach altogether by the WHODAS questionnaire. Several methods were tested on the pilot dataset to address this question. These methods can be grouped here into three principal strategies: (1) averaging the medical assessment percentage with the WHODAS score to arrive at a final disability assessment score, (2) flagging persons whose WHODAS score and disability severity are different from the severity group based on the percentage determined by medical information alone, and (3) scaling the civil invalidity percentage by a certain coefficient ‘x’ when the WHODAS-score exceeds or falls below a certain threshold or reference value. It is important to add that as WHODAS is used in Italy, more data are collected. This data can be analysed using the techniques from this report to continually update and recalibrate parameters and cut-off points. In more detail, the three approaches work as follows:

1. Averaging – averaging in some predetermined way the attributed civil invalidity percentage and the WHODAS score. This approach is based on the theory that, together, medical information and functioning scores contribute, to different degrees, to a realistic and valid assessment of disability.

2. Flagging – identifying persons whose WHODAS score differs from the medically determined civil invalidity percentage and flagging these individuals to request from them additional information or even a full reassessment. When an individual has a WHODAS score over or below some cut-off value, this suggests that the medical score alone does not adequately capture the experience of disability and a second-level assessment should be conducted.

3. Scaling – the civil invalidity percentage can be altered (i.e. raised or lowered) to reflect the WHODAS score by means of a score‑based coefficient. This approach assumes that at the core of disability and civil invalidity assessment is the medical problem that the individual experiences, but at the same time, that the performance is modified (to some extent) by environmental factors that need to be understood to augment or diminish the medical score.

Averaging, flagging, and scaling are three of several potential approaches to bringing together two scores that measure different phenomena but which, together, constitute our best assessment of disability. Each approach is grounded in the ICF’s understanding of disability as the outcome of an interaction between a person’s underlying health condition and impairment on the one hand and the physical, human-built, interpersonal, attitudinal, social, economic, and political environment in which the person lives on the other hand. The three approaches differ, however, in how they weigh the impact of the respective medical and environmental determinants of disability. The next section describes the results of applying strategies that were tested using different weighting combinations.

5.5. The impact of different policy options including functioning elements

This section presents in more detail the three options to include functioning into disability assessment in Italy. Each option follows the ICF in recommending a combination of medical and functioning assessment (with the latter provided by WHODAS). Option A is the situation in which WHODAS scores are considered, or disregarded, in a purely discretionary manner. Options B (averaging strategies), C (flagging strategies) and D (scaling strategies) are quantitative. Each option has advantages and disadvantages.

The framework for evaluating the pros and cons of every approach draws on key scientific principles that determine the credibility of any disability assessment process: validity (the extent to which the option relies on a true assessment of disability); reliability (the ability of the option to arrive at the same assessment of the same case by different assessors); transparency (the degree to which the assessment process and outcomes can be described and understood by all stakeholders); and standardisation (the extent to which the process resists distortion or alteration over time and across locations).

Option A is the option in which an individual or committee reviews medical scores and the WHODAS scores and makes a judgment about the extent of disability as the individual or committee sees fit. This is a purely discretionary option, surprisingly common in practice. This approach is subject to manipulation, lacks validity and reliability, and is utterly non-transparent. The option is given here as a contrast to the remaining options B, C, and D, but also, in fairness, because some countries continue to rely on this option for disability assessment (strategy #1). The authors of this report do not recommend this option. Numerous interactions with officers involved in disability assessment in different countries suggest that medical professionals involved in the assessment of disability are confident they can consider functioning and the experience of disability as part of the medical description of the applicant’s situation. One often hears medical assessors claim that they take functioning fully into account when examining medical records. One implicit result from the pilot is, however, that this assumption is not grounded in evidence.

Averaging, flagging, and scaling are quantitatively driven options, very different from Option A. In different ways and for different reasons, they satisfy not only the basic psychometric assumptions of validity and reliability but each, to different degrees, strives to achieve transparency and standardisation.

5.5.1. Using an averaging algorithm

In the Italian pilot WHODAS data set, there is a relatively small percentage of persons indicating no functioning problems at all (only 2.3%), among which the majority had a moderate or severe degree of civil invalidity. Weighting the civil invalidity percentage with the WHODAS score would adjust levels of invalidity by accounting to some degree for the observed and experienced disability level assessed by the WHODAS questionnaire. To get a full sense of the range of possible approaches under Option B, four weighting schemes are shown: (i) 75% civil invalidity percentage and 25% WHODAS score; (ii) 50% each; (iii) 25% civil invalidity percentage and 75% WHODAS score; and (iv) 0% civil invalidity percentage and 100% WHODAS score (represented by strategies #2 to #5). Option #5 shows the result of WHODAS alone.

Advantages of averaging: (i) An assessment of the level of functioning plays a significant role in the determination of eligibility for disability benefits so that the eligibility for benefits is not solely based on purely medical criteria. (ii) The averaging approach minimises the impact of the inherent psychometric problems with the civil invalidity percentage based on the Barema-based medical assessment. (iii) The assessment of the level of functioning is empirically and statistically verified. (iv) This option yields high levels of validity and reliability. (v) Merging the results of two assessments scaled by means of “weighted averages” is fully objective, transparent, and non-discretionary. (vi) The method is not sample‑dependent.

Disadvantages of averaging: (i) There are, potentially, an infinite number of combinations of weighting schemes (i.e. “strategies”), each of which affects the set of eligible applicants differently and has different budgetary and political consequences. This is an unavoidable fact about the nature of disability as a continuum and the fact that there are not yet scientifically verified or objective cut-offs for severity on a 0‑100 continuum. (ii) Any strategy selected will be objectionable to individuals who, under that strategy, will not be certified as having a disability and thus not eligible for any benefits. This signals the need for clear and transparent information dissemination and a solid grievance redress system that may include using tools for clinical testing and determination of functioning.

5.5.2. Using a flagging algorithm

Six different flagging strategies are represented by strategies #6 to #11. The idea of this strategy is to highlight individuals whose civil invalidity percentage is unexpected in view of the WHODAS score. A conservative approach would be to flag individuals with scores in the upper (or lower) extremes of the WHODAS score distribution of the sample, who have a very small (or large) civil invalidity percentage (#6). The next four approaches do not use the sample distribution but the distribution of scores within civil invalidity degree groups to increase or decrease the invalidity percentage. The approach #11 combines strategies #7‑10 and considers all cases that fall into one of these groups.

Advantages of flagging: (i) Scientifically robust and based on actual data. (ii) Shows that the purely medical approach to disability assessment may not accurately assess disability in many cases – in which, as reported in the WHODAS score, a person is experiencing more, or fewer, functioning problems in their lives than what the health condition is thought to imply. (iii) High levels of validity and reliability.

Disadvantages of flagging: (i) WHODAS cut-offs for different degrees of functioning problems are based on the experiences from past pilots and some evidence from the scientific literature. Sensitivity analyses are not available to this point. More precise cut-off values specific to Italy may be introduced at later time points when more information on functioning is collected (assuming WHODAS will be introduced into the existing system). (ii) Technically robust methodological and procedural instructions will have to be developed to guide the reassessment process to ensure transparency.

Even with the caveat on the cut-off points for disability severity, the flagging method may be introduced through a specifically designed two‑step administrative procedure.

5.5.3. Using a scaling algorithm

The scaling approach, represented by strategies #12 and #13, reproduces an approach that is in some form used in some countries (e.g. Lithuania) though generally in a rather opaque way, namely, modifying the civil invalidity percentage assigned by a disability assessment committee by means of a coefficient representing functioning information (e.g. generated by a WHODAS score). The idea behind this approach is to avoid relying on a medical determination of disability exclusively, as such an approach undervalues the actual impact of health conditions on a person’s life and functioning performance.

Two strategies to illustrate the scaling approach are used (there are, in theory, many other possibilities). The first strategy would look for individuals with high disability, according to their WHODAS score, above the WHODAS cut-offs of 40 and 60 to augment their civil invalidity percentage, either by a coefficient of 1.25 (with WHODAS scores above 40) or 1.5 (with WHODAS scores above 60). Reversely, in the second strategy used, individuals with a very low disability according to their WHODAS score, below the WHODAS cut-offs of 40 and 25, are selected to reduce their civil invalidity percentage either by a coefficient of 0.95 (with WHODAS scores below 40) or 0.9 (with WHODAS scores below 25). The choice of coefficients here is to some extent driven by the objective to achieve similar impact in both directions.

Advantages of scaling: (i) Using a coefficient value generated statistically is a common and widely used approach. (ii) A coefficient approach (increasing or reducing the medically-determined civil invalidity percentage considering the corresponding functioning score) is the most intuitive way to combine the scores of very different assessments – medical and functioning – into a single score. (iii) This option incorporates the insight that a medical determination alone can often miss instances where people have only moderate or very high disability needs. (iv) This option, because of the psychometric properties of WHODAS, would have high levels of validity and reliability.

Disadvantages of scaling: (i) As with other options, there are many possible variations of approach D with different outcomes – in this report only two possibilities are presented, as an illustrative example. Although the scaling approach itself is intuitively understandable and can be made transparent to the public, the scientific and statistical justification for Option D is therefore somewhat technical and may not be easily understandable by a lay public.

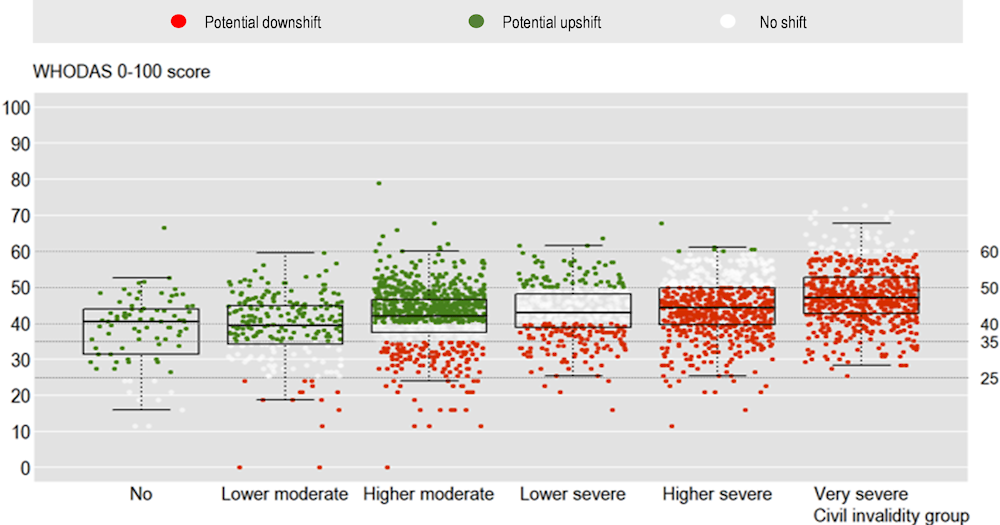

Table 5.9 provides an overview of the testing strategies that were considered and gives the number of individuals who would have a moderate, severe, or very severe disability after adjusting for the WHODAS score. Further, and maybe most importantly, the table also shows the number of individuals who would have their civil invalidity severity ranking changed towards a higher degree (total upshifts) or a lower degree (total downshifts). In brief, the results are as follows:

The four averaging strategies show that the use of WHODAS generally generates more upshifts to higher invalidity degrees than downshifts. Giving WHODAS a weight of 25% (strategy #2) changes little, as it affects only 2.5% of the sample and of those, most would see a downshift – these are people just above one of the invalidity thresholds who seem to function well, maybe because the environment is supportive, and their needs are addressed. The more weight WHODAS receives, the more people are affected and the more upshifts occur. With a 50% weight to both WHODAS and civil invalidity (strategy #3), 8.5% of the sample would be affected, with an equal number of upshifts and downshifts. With WHODAS only (strategy #5), 42% of the sample would see a change in the invalidity severity, with two‑thirds seeing an upshift. Most upshifts are a shift from moderate to severe invalidity, potentially generating more eligibility for a disability allowance. On the contrary, the number of people with very severe invalidity considered to be non-self-sufficient and, thus, in need of constant care would fall drastically, from over 20% to only 2% of the sample. This suggests that current medically based disability assessment may be overestimating the degree of disability and policies may be setting the wrong priorities, and incentives.

The six flagging strategies show that very few people currently receive an invalidity rating that is drastically different from their actual disability experience, as measured by WHODAS. Only 2% of the sample have extremely low or extremely high WHODAS scores (strategy #6) and only 5.5% of the sample would be flagged as having an invalidity rating very different from their WHODAS score (strategy #11). Among those 5.5%, two‑thirds would potentially see a downshift in their current severity rating depending on the result of the indicated second assessment and most of them would be people classified with 100% civil invalidity although experiencing much less disability. (For supplementary flagging variants, see section 6.3).

The coefficients chosen for the two scaling strategies generate a situation in which over 8% of the sample would see their invalidity rating increased because of (very) severe disability according to WHODAS (strategy #12) and, similarly, close to 8% would see their invalidity rating lowered because of no or only moderate disability experience according to WHODAS (strategy #13). The large difference in the size of the coefficients is a result of the current invalidity assessment and rating, with so many people found just above the next invalidity threshold. A clear disadvantage of strategy #12 is that it increases the already large number with a very severe invalidity rating. Combining strategy 12 and strategy 13 would imply that 16% see their rating changed.

Table 5.9. Overview of strategies and changes in group sizes based on the selected approaches

|

|

# |

Description |

No civil invalidity |

Moderate civil invalidity |

Severe civil invalidity |

Very severe civil invalidity |

Total upshift |

Total downshift |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

A. Discretionary |

#1 |

Civil Invalidity cut-offs |

81 |

1 129 |

1 076 |

623 |

0 |

0 |

|

B. Averaging |

#2 |

Civil Invalidity 75%, WHODAS 25% |

82 |

1 157 |

1 047 |

623 |

21 |

51 |

|

#3 |

Civil Invalidity 50%, WHODAS 50% |

87 |

1 131 |

1 068 |

623 |

116 |

130 |

|

|

#4 |

Civil Invalidity 25%, WHODAS 75% |

52 |

1 059 |

1 176 |

622 |

337 |

209 |

|

|

#5 |

Civil Invalidity 0%, WHODAS 100%1 |

63 |

856 |

1 921 |

69 |

768 |

459 |

|

|

C. Flagging |

#6 |

Extreme WHODAS scores: < 24 or > 63 |

118 |

1 102 |

1 064 |

625 |

7 |

53 |

|

#7 |

WHODAS score > 40, Civil Invalidity < 33% |

40 |

1 170 |

1 076 |

623 |

41 |

0 |

|

|

#8 |

WHODAS score > 60, Civil Invalidity < 66% |

80 |

1 120 |

1 086 |

623 |

10 |

0 |

|

|

#9 |

WHODAS score < 25, Civil Invalidity > 66% |

81 |

1 143 |

1 062 |

623 |

0 |

14 |

|

|

|

#10 |

WHODAS score < 40, Civil Invalidity 100% |

81 |

1 129 |

1 170 |

529 |

0 |

94 |

|

|

#11 |

Sum of approaches #7‑#10 |

40 |

1 174 |

1 166 |

529 |

51 |

108 |

|

D. Scaling |

#12 |

if WHODAS indicates Severe disability then Civil Invalidity x 1.25 Very severe disability then Civil Invalidity x 1.5 |

78 |

889 |

1 125 |

817 |

243 |

0 |

|

|

#13 |

if WHODAS indicates Moderate disability then Civil Invalidity x 0.95 No disability then Civil Invalidity x 0.9 |

105 |

1 205 |

1 070 |

529 |

0 |

218 |

Note: This approach uses the WHO Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS) cut-offs: WHODAS scores < 25 indicate no disability, 20 to 40 moderate disability, 40 to 60 severe disability, and > 60 very severe disability.

Source: OECD calculations based on the pilot data.

5.6. Reflections and conclusions

The pilot evaluation suggests that the current disability assessment system in Italy would benefit from the inclusion of functioning information into the assessment method in at least three ways:

the assessment of disability would be more precise and accurate, reflecting the real-life experience of disability and identifying some people who are not well identified by a purely medical approach;

the assessment would be in line with today’s interdisciplinary understanding of disability to which Italy has committed already 14 years ago when it ratified the UN Convention; and