This chapter provides an overview of Brazil’s public institutions and describes the main features of the electricity sector as well as the legislative framework that determines the functions of Brazil’s national electricity regulator (Agência Nacional de Energia Elétrica – ANEEL).

Driving Performance at Brazil’s Electricity Regulatory Agency

1. Sector context

Abstract

Sector reforms

The Brazilian electricity sector has gone through profound transformations over the past decades. Prior to 1995, vertically-integrated energy companies, mostly state controlled, characterised the sector. The market struggled to keep up with an increase in demand for electricity, which worsened during the 1990s. This situation ultimately led to two waves of sector reforms, in the 1990s and 2004. The reforms aimed to increase the supply and affordability of electricity, by promoting private investment and competition as well as introducing efficiency incentives.

First wave of reforms: 1990s

The government implemented a series of reforms to open the Brazilian electricity market to competition and increase private investment in the 1990s, inspired by reforms in many European countries such as the United Kingdom. As a consequence, the biggest state-owned entity in the market, Centrais Elétricas Brasileiras S.A. (Eletrobras), was split into 6 holding companies and 14 generation and transmission companies (Vagliasindi and Besant-Jones, 2013[1]) and many state companies changed into private hands (OECD, 2008[2]). Large consumers (with a capacity above 10 MW) obtained the right to contract their own electricity through a wholesale market. The legislative framework established a third-party access regime, granting independent power producers (IPPs) access to the transmission and distribution networks (Lei Nº 9.074, de 7 de Julho de 1995, 1995[3]). Finally, the reforms in the 1990s led to a tariff framework for distribution companies based on the required cost to operate, given the company’s circumstances (number of consumers, size of network, etc.) (Lei nº 8.631, de 4 de Março de 1993, 1993[4]). Before the 1990s reforms, the applicable tariff for electricity consumption was uniform across the country, while the return for companies was fixed, providing little incentive to companies to operate efficiently.

The reforms came with a new oversight framework, which included the creation of the national electricity regulator (Agência Nacional de Energia Elétrica – ANEEL). ANEEL regulates the generation, transmission, distribution and commercialisation of electricity across Brazil (Lei Nº 9.427, de 26 de Dezembro de 1996., 1996[5]). A new committee, the National Energy Policy Council (Conselho Nacional de Política Energética – CNPE), was set up to advise the President of the Federative Republic of Brazil on energy policy (Lei nº 9.478, de 6 de Agosto de 1997, 1997[6]). The CNPE includes representatives from the Ministry of Mines and Energy (Ministério de Minas e Energia – MME), who is the chair, as well as a range of other ministries1 and representatives of the state and federal district, civil society and universities. In parallel, additional legislation in 1998 and 2002 created a national system operator (Operador Nacional do Sistema Elétrico – ONS) and a market manager (Mercado Atacadista de Energia Elétrica – MAE) (Lei nº 9.648, de 27 de Maio de 1998, 1998[7]), (Lei nº 10.848, de 15 de Março de 2004., 2004[8]).2

2001 supply crisis

The first wave of reforms could not prevent a supply crisis in 2001. While installed generation capacity increased by 28% during the 1990s, demand grew by 45% in the same period, in part because private investment in the sector did not take off as expected. Flawed pricing regulation was one reason, and generation companies claimed that the regulatory price cap did not allow them to earn back the cost of new generation capacity (OECD, 2008[2]). Moreover, the new wholesale market led to many disputes around the contracts between buyers and sellers of electricity. MAE was unable to successfully arbitrate on the disputed contracts, partly because the many stakeholders involved were unable to agree on the market rules. This led to a loss in credibility in the functioning of the market (Melo, Neves and Da Costa, 2009[9]).

Unsuccessful in attracting significant investment in thermal generation, most new investment was still in hydro generation.3 The high share of hydro generation in Brazil makes the electricity supply vulnerable to drought. In the year prior to the supply crisis, wholesale prices increased to unprecedented levels, as a drought led to reduced water levels at hydro dams. The government launched a programme to stimulate investment in gas-fired plants, but investors were reluctant to step in. This was in part because of the high price of gas as charged by Petróleo Brasileiro S.A. (Petrobras), the state-owned oil and gas company, and in part due to concerns about the stability of the regulatory regime and government policies. To combat the supply shortage, the government created a special commission (Câmara de Gestão da Crise de Energia Elétrica – CGE) with special powers to implement a package of measures to decrease electricity consumption. Measures included mandatory energy saving targets for all consumer classes and a public awareness campaign. Consumers that did not meet their targets faced supply interruptions, as well as higher tariffs. Consumers reducing their consumption by more than their target received a bonus (IEA, 2005[10]). Although in this way the government was able to manage the crisis by reducing electricity consumption quite drastically by 20% in majority of the country (Vagliasindi and Besant-Jones, 2013[1]), the electricity system was in need of further reforms.

The 2001 supply crisis brought energy efficiency and management, as well as the need for a body that could provide strategic planning, back to the political agenda. Moreover, governance problems, most notably at the MAE, were impeding a well-functioning electricity market. Clear guidance and strategic planning, which the MME took care of before the 1990s reforms, were lacking in the new market structure (OECD, 2008[2]).

Second wave of reforms: 2004

In 2004, the Brazilian government adopted new legislation restructuring the electricity market (Lei nº 10.848, de 15 de Março de 2004., 2004[8]). The reform aimed to increase the security of supply in the electricity market by attracting investment at a low cost, and to keep tariffs for consumers at a reasonable level (OECD, 2008[2]). This was to be achieved through several objectives:

to create a hybrid between a regulated market and a free market,

to improve the institutional structure of the market,

to improve the functioning of the wholesale market, and

to further increase private investment in new generation.

The privatisation of state companies stalled, as the goal was no longer to privatise all companies (Vagliasindi and Besant-Jones, 2013[1]). The “new model” divided consumers into a regulated market and a competitive market based on their level of consumption. Most consumers remained captive consumers subject to a regulated market (Ambiente de Contratação Regulada – ACR), supplied by distribution companies that must contract the required electricity with generation companies through auctions (see Box 1.1). Competition is possible in the free market (Ambiente de Contratação Livre – ACL) for consumers with an electricity load above 2 MW4 (mostly large industrial or commercial consumers)5, who can contract their electricity directly with generation companies, and through the auctions for generation, transmission and distribution. Finally, a new entity, the Electric Power Trading Chamber (Câmara de Commercialização de Energia Elétrica – CCEE) absorbed the MAE, and is responsible as a market manager for settlements between the regulated and free market, as well as certain practical aspects of the auctions. ANEEL supervises the operations of the CCEE and the ONS, which are not-for-profit private enterprises. ANEEL approves the budget of ONS, which is financed mainly through a charge included in the transmission fee, while CCEE is paid by its members6 (ANEEL, 2016[11]) (Lei nº 10.848, de 15 de Março de 2004., 2004[8]).

Table 1.1. Electricity market structure after 2004

|

|

Regulated market (ACR) |

Free market (ACL) |

|---|---|---|

|

Type of consumers |

Consumers with a capacity below 2 000 kW |

Consumers with a capacity starting from 2 000 kW* |

|

Consumers can buy their electricity from |

Distribution companies |

Generation companies, traders, self-producers and distribution companies |

|

Market mechanism |

Regulated auctions with long-term contracts |

Bilateral contracts |

|

Price level |

Electricity price based on average in regulated auctions, plus cost component for transmission and distribution network |

Freely negotiated price for electricity, plus cost component for transmission and distribution network |

* Consumers with a capacity starting from 2 000 kW have the possibility to opt-out of the free market, thereby returning to the regulated tariffs applicable in the ACR.

Source: Information provided by ANEEL, laws no. 9.074/1995 and 10.848/2004 and ordinances no. 514/2018 and 465/2019 (Lei Nº 9.074, de 7 de Julho de 1995, 1995[3]) (Lei nº 10.848, de 15 de Março de 2004., 2004[8]) (Portaria nº 514, de 27 de Dezembro de 2018, 2018[12]) (Portaria nº 465, de 12 de Dezembro de 2019., 2019[13]).

Box 1.1. Auctions and concessions

The auctions for generated electricity are an essential element of the Brazilian market structure. ANEEL organises these annual auctions, at the request of MME. Auctions exist for three categories: electricity from existing plants, electricity from new plants and renewable energy. Nuclear energy generation is excluded from auctions, as this activity cannot be delegated to private companies. As part of the auction process, distribution companies (who also act as suppliers to the captive consumers) need to contract their estimated demand for the coming three to five years. These estimates provide input for the MME and EPE in their planning of the required supply capacity. Investors bid to supply the capacity; those offering to sell the electricity at the lowest price win the concessions, and the length of the concession depends on the type of electricity produced (hydro concessions last longer than thermal concessions). ANEEL and the CCEE can promote adjustment auctions for electricity to be delivered the next year. Both national and foreign firms can participate in the auctions, however foreign firms must assign a local representative and need to set up a Special Purpose Company for any concession won.

The price buyers pay for the electricity is equal to the average of total generation costs for the regulated market, and is therefore the same across all distribution companies. Moreover, since the distribution companies contract the projected demand in advance in long-term contracts, this reduces the risk for generation companies. The free market (ACL) provides a market clearing function, as when the contracted electricity by distribution companies exceeds demand, they can sell the excess electricity on the free market. Similarly, if realised demand exceeds the level that the companies contracted, they can buy from the free market.

Whether a generation company requires a concession, authorisation, or registration to construct and operate generation facilities depends on the capacity and nature of the facility, as well as on whether it is active on the regulated or free market. Hydro and thermal generation with a capacity above 50 000 intended for the regulated market is granted through concessions. Independent Power Producers (PIEs) that sell their electricity exclusively on the free market, or use it for own consumption, hold an authorisation. Self-producers generating power of any source can request a self-generation license from ANEEL. For hydro generators there are a number of extra requirements, most notably the requirement of a hydro power inventory study. Generators with an installed capacity below 5 000 kW do not need a concession or authorisation, but simply require a registration with ANEEL.

Next to the auctions for electricity generation, works on the transmission lines are awarded through both authorisations and auctions. For existing transmission lines, ONS draws up plans for maintenance and improvement, in collaboration with MME and EPE. ANEEL authorises existing concession holders to execute these projects, and grants them additional revenue to do so. For new transmission lines, EPE designs the required new lines. After approval of these new transmission lines by MME, ANEEL organises a bidding process. The lowest bidder wins the concession, and is tasked to develop, operate and maintain the project for a period of 30 years.

Electricity distribution qualifies as a public service, as defined in the constitution, and therefore is the responsibility of the Brazilian government. However, the executive may grant concessions to private parties for a period of 30 years, through an auction process. At present, 53 distribution concessions exist, of which ten are under state control (state or municipal). As is the case with generation and transmission concessions, concession holders can be foreign as long as they set up a Special Purpose Company for the execution of their tasks.

Source: (OECD, 2008[2]), OECD Reviews of Regulatory Reform: Brazil 2008: Strengthening Governance for Growth, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264042940-en; Lei Nº 9.074, de 7 de Julho de 1995 (1995), Presidência da República, http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l9074compilada.htm.

Under the 2004 legislation, energy policy is set by the President of Brazil who is assisted by the CNPE. The framework provides a new central planning body, the Energy Research Enterprise (Empresa de Pesquisa Energética – EPE), filling a vacuum after the first waves of reforms. The EPE is a subordinate body to the MME and draws up the strategy for the energy sector, as well as its long-term goals. To do so, it analyses long-term developments in future demand and formulates strategy studies for 10 and 25 year horizons. MME subsequently uses this input to construct a power portfolio, in which it determines the share in total generation for the different energy sources. The aim is to find a ‘desirable’ mix of sources, with a balance between different technologies and between cost and energy security. The EPE draws up a list of potential projects, which need approval from the MME and the CNPE, after which the certified projects will be part of the auctions for generated electricity (OECD, 2008[2]). Next to the long-term planning by EPE, Electricity Industry Monitoring Committee (Comitê de Monitoramento do Setor Elétrico – CMSE) monitors and evaluates the security of supply in the electricity market. The CMSE consists of representatives of the MME, ANEEL, CCEE, EPE, ONS and the National Agency of Petroleum, Natural Gas and Biofuels (Agência Nacional do Petróleo, Gás Natural e Biocombustíveis – ANP), thereby combining the knowledge and insights of many key institutions in the market.

Developments since 2004

While the reforms in 2004 lay the foundations of the market as it is structured today, the electricity market is still subject to an ongoing reform process. Many new laws and decrees since 2004 highlight this, as well as considerations for further reform. Changes in legislation include adjustments in the rules for concessions, extensions of existing concessions, the regulation of the CDE and a reduction in subsidies for low-income households7 (see Box 1.2). Moreover, the President of Brazil created the Investment Partnership Program (Programa de Parcerias de Investimentos – PPI) in 2016 (Lei nº 13.334, de 13 de Setembro de 2016., 2016[14]), giving privatisation and private investment in infrastructure an extra push. According to the programme’s website, the programme aims to expand and accelerate the transfer between the State and private sector. The President can assign projects to the programme in the energy sector, as well as other infrastructures such as airports and ports, after which they are auctioned by ANEEL. The programme led to a number of privatisations of generation, transmission and distribution projects since 2016.8

Looking forward, a number of discussions and developments might affect the market structure in the future. These include three major developments:

An ordinance by MME aims to gradually over time enable more consumers to choose their own supplier. In the current situation, only large consumers with a capacity above 2 MW can choose their own supplier, whereas the smaller ‘captive’ consumers have to buy their energy directly from their distribution company. As of 1 January 2023, all consumers with a capacity equal to or greater than 500 kW should be able to choose their own supplier. In order to allow the opening for the consumers below that threshold, and thereby open up the market for all consumers regardless of their capacity, ANEEL together with CCEE have been assigned to conduct a study on the necessary regulatory measures (Portaria nº 465, de 12 de Dezembro de 2019., 2019[13]).

On the 5th of November 2019, President Bolsonaro signed a bill with the intent to privatise Eletrobras, Brazil’s largest and state-controlled electricity company, by 2020. Given Eletrobras’s dominant position the electricity sector, with large activities in generation and transmission, a privatisation could have a significant impact on the Brazilian electricity market. Along with privatisation, the bill would make an end to the ‘golden share’ held by the Brazilian federal government, which would limit its influence over the company.

The MME has initiated a working group for the modernisation of the electricity sector. One of the aims of the modernisation is to improve pricing mechanisms in the wholesale market. While the current system is based on weekly prices, the public consultation showed a need for more granular prices (MME, 2019[15]). More granular pricing signals can improve the adequacy with which prices reflect scarcity of electricity, increasingly important in the context of a higher penetration of more volatile renewable sources in the electricity system. Other themes within the modernisation effort are i) ways to improve the market environment and expansion of the sector, ii) rationalisation of charges, iii) an energy reallocation mechanism, iv) the allocation of costs and risks, v) the insertion of new technologies into the system and vi) the sustainability of distribution services (Portaria nº 187, de 4 de Abril de 2019, 2019[16]).

Box 1.2. Social policy in the Brazilian electricity sector

In November 2003, the Brazilian government launched an ambitious programme to provide universal access to electricity for all Brazilians. The programme, named “Luz para Todos” (“Light for All”), aimed to bring electricity to Brazilians who did not have access to the network in 2003, of whom an estimated ten million lived in rural areas. The programme is a follow-up of the “Luz para Campo” (Light for the Countryside) programme. The programme intends to bring electricity to households mostly via renewable energy sources such as solar power and biomass sources, as the government saw this as the most efficient option to connect the consumers in sparsely populated areas such as the Amazon territory.

MME co-ordinates the programme and it is funded by two main sources. The first is a general reversion fund (Reserva Global de Reversão – RGR), which provides loans and collects its funding through concession fees and fines from the distribution companies. The second source is the Energy Development Account (Conta de Desenvolvimento Energético – CDE), which provides subsidies. The CDE itself is mainly funded through the tariffs that consumers pay for their electricity, and the fund’s budget is managed by CCEE and approved by ANEEL. Other sources of funding for the “Luz para Todos” programme come from federal states and municipalities, as well as the distribution companies.

The government initially intended to provide electricity to ten million Brazilians, as identified by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatistica – IBGE), by 2008. However, throughout the execution of the programme more households were identified and added to the programme, most of the times in areas that were difficult to reach. As a consequence both the scope and schedule of the programme have been modified and it is currently due to last until 2022 (as determined by decree No. 9.357/2018). According to the MME, the programme connected 3 405 169 households, or about 16.2 million inhabitants, by April 2018.

Rural and low-income households can also receive a subsidy on their electricity tariffs, financed through the CDE.1 Moreover, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, low-income households with a consumption below 220kW received a 100% discount in the months April to June 2020. ANEEL will approve the funds that the fund will transfer to distribution companies, in order to compensate households through reduced tariffs. Following Decree n. 9.642/2018, the discount in subsidies for rural consumers, rural distribution cooperatives and public service of water, sewage, sanitation and irrigation services will gradually decrease over time, at the rate of 20% per year as of 1 January 2019.

1. Next to subsidies for rural and low-income households, the CDE also provides subsidy for irrigation and aquaculture, sewage water sanitation and the consumers and producers of incentivised sources, amongst others.

Source: IEA (2017), Luz para Todos (Light for All) Electrification Programme, https://prod.iea.org/policies/4659-luz-para-todos-light-for-all-electrification-programme (accessed 14 April 2020); MME (n.d.), O Programa, https://www.mme.gov.br/luzparatodos/Asp/o_programa.asp (accessed 30 April 2020); Lei nº 12.212, de 20 de Janeiro de 2010 (2010), Presidência da República, http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2007-2010/2010/lei/l12212.htm; Decreto nº 9.357, de 27 de Abril de 2018. (2018). Presidência da República. http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2015-2018/2018/Decreto/D9357.htm; Decreto nº 9.357, de 27 de Abril de 2018. (2018). Presidência da República http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2015-2018/2018/Decreto/D9357.htm.

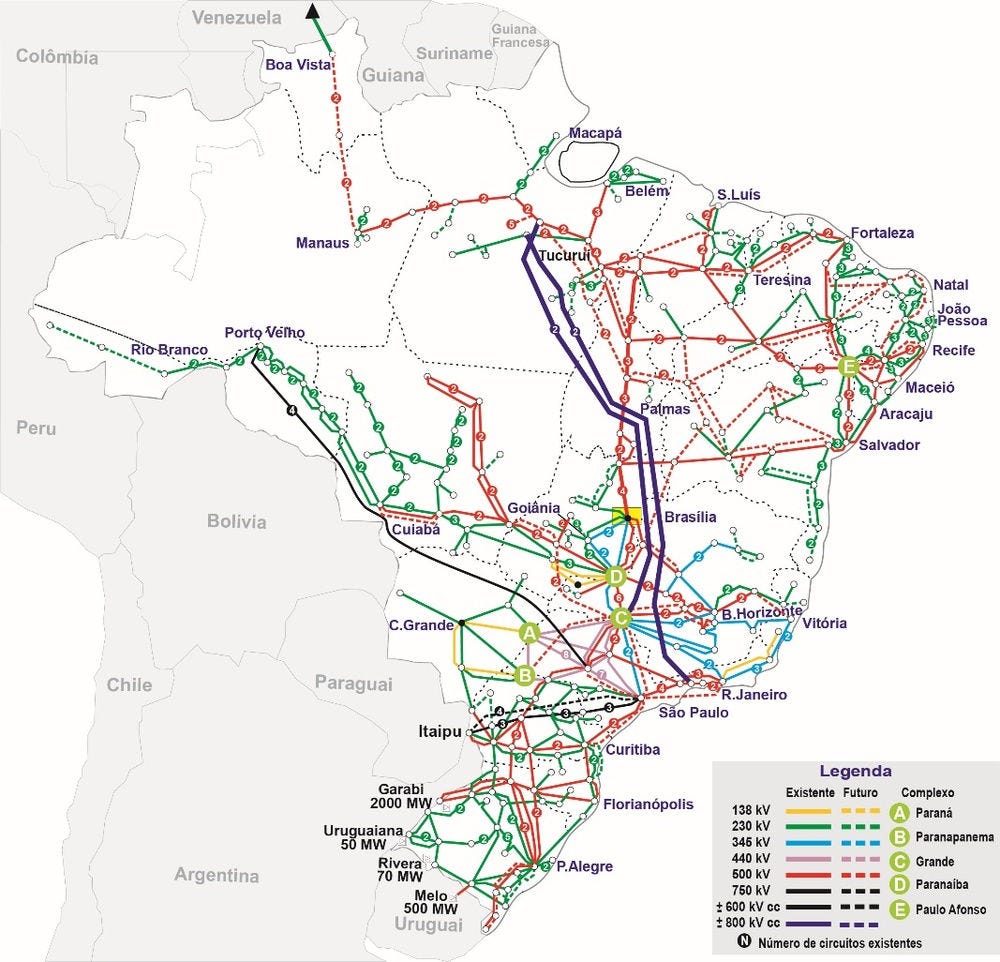

Market overview

Brazil’s main transmission network, the National Interconnected System (Sistema Interligado Nacional – SIN), consists of four interconnected subsystems (North, Northeast, Southeast and Centre-West, South). Together, they make up one of the largest interconnected subsystems in the world. The Brazilian network has interconnections with neighbouring Paraguay (through the Itaipu Binacional project), as well as Uruguay, Argentina and Venezuela. The system operator (ONS) expects the network to grow to 182 000 km of transmission lines by 2024 from 142 000 km in 2019 (see Figure 1.1). ONS envisages an extension of the grid towards the less well-connected Northwest of Brazil, connecting cities such as Boa Vista to the network, as well as further improving the existing grid in other parts of the country. In addition to the national grid, there are 235 so-called Isolated Systems (Sistemas Isolados) which are not connected to the SIN (ONS, n.d.[17]). These isolated networks are mainly located in the Amazon region in the northwest of the country, as well as on a number of Brazilian islands, and serve a relatively small consumer base.

While market reforms ordered the unbundling of vertically-integrated companies into separate companies,9 distribution companies still perform the role of electricity supplier for the majority of consumers that is subject to the regulated market. Moreover, generation, transmission and distribution companies need to dedicate a minimum percentage of their income to research and development projects (Lei n. 9.991, de 24 de Julho de 2000., 2000[18]).

A substantial change to the remuneration system resulted from Law No. 12,783/2013 (Lei nº 12.783, de 11 de Janeiro de 2013., 2013[19]). The law provided the option for holders of concessions that were due to expire to extend their concessions for a period of up to 30 years, against a remuneration system established by ANEEL.10 For distribution companies and transmission companies with extended concessions, the remuneration is based on efficient operational expenditure estimates using DEA methods (Lopes et al., 2020[20]), (Costa, Lopes and de Pinho Matos, 2015[21]). Extended hydro generation concessions subject to the quota regime are remunerated based on tariffs and quotas of physical guarantee of electricity to distribution companies as set by ANEEL (Lei nº 12.783, de 11 de Janeiro de 2013., 2013[19]).11 However, the hydrological risk, which has been a frequent subject of legal disputes,12 was transferred to the distribution companies for extended concessions, meaning distribution companies have to cover the costs of extra electricity purchases in case the amount of hydro power generated was below the physical guarantee.

Figure 1.1. National Integrated System Brazil

Note: The figure depicts the current state of the National Integrated System of Brazil, as well as projected future expansion until 2024 (dotted lines).

Source: ONS (n.d.), Mapas [Maps], http://www.ons.org.br/paginas/sobre-o-sin/mapas (accessed 14 April 2020).

Box 1.3. Eletrobras and Petrobras

Traditionally, Centrais Elétricas Brasileiras S.A. (Eletrobras) and Petróleo Brasileiro S.A. (Petrobras) dominated the energy sector in Brazil. Before the first wave of sector reforms in the 1990s, Eletrobras was the dominant actor in the electricity sector, active in generation, transmission, distribution and supply. Over time, Eletrobras was required to unbundle its vertically integrated companies, and its market share decreased due to both privatisations and new concessions for generation and transmission granted to other companies. Still, it owns four of the five largest companies for both transmission and generation, and remains the largest electricity company in the country. Eletrobras’s role in the execution of a number of government programmes further highlight its status in the Brazilian electricity sector. Eletrobras manages the “Luz para Todos“ programme, bringing electricity to millions of Brazilian households, under the co-ordination of MME. Moreover, when the privatisation of six distribution companies failed due to their poor performance, Eletrobras took over these companies in 1997, after which they were privatised in 2018 (The World Bank, 2019[22]). Until 30 April 2017, it also managed the budget and operations of the CDE and RGR, as well as a Fuel Consumption Account (Conta de Consumo de Combustíveis – CCC) to subsidise thermal energy generation. From May 2017 onwards, CCEE took over these operations (as determined by decree n. 9.022/2017).

Petrobras is Brazil’s state-owned oil and gas company, and the biggest company in Brazil in terms of revenues.1 Until the 1997 reforms (Law n. 9.478/1997), which opened up the market for competition, it enjoyed a monopoly in the oil and gas market. Since then, other companies have joined the market, but Petrobras maintains its dominant position. Besides its dominant position throughout the gas sector, it is also active in electricity generation, and owns the sixth largest electricity producer.

1. According to the Global Fortune 500 list.

Source: IEA (2017), Luz para Todos (Light for All) Electrification Programme, https://prod.iea.org/policies/4659-luz-para-todos-light-for-all-electrification-programme (accessed 14 April 2020); Vagliasindi, M. and J. Besant-Jones (2013), Power Market Structure, http://dx.doi.org/10.1596/978-0-8213-9556-1; The World Bank (2019), Improving Performance of Electricity Distribution in Brazil, https://www.worldbank.org/en/results/2019/04/24/improving-performance-of-electricity-distribution-in-brazil (accessed 14 April 2020); Lei No. 9.478, de 6 de Agosto de 1997. (1997). Presidência da República, http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l9478.htm; Decreto No. 9.022, de 31 de Março de 2017. (2017). Presidência da República, http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2015-2018/2017/Decreto/D9022.htm.

Table 1.2. Market structure and ownership in electricity sector

|

Distribution |

Transmission |

Generation |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Market structure |

53 distribution companies + 51 distribution cooperatives1 |

242 transmission companies |

8 054 generation plants |

|

Market share 10 biggest companies |

61.89% |

69.33% |

37.95% |

|

Government ownership estimates |

10 out 53 distribution companies under public control (state or municipalities) in 2019 |

World Bank estimated private ownership at 14% in 2008, which likely increased since the new concessions that have been granted to private companies since 2008 |

World Bank estimated private ownership at 27% in 2008, expected to grow to 44% over a period of 5-6 years and 50% in the longer term |

1. The distribution cooperatives are collective initiatives to provide electricity to areas that are not serviced by distribution companies.

Source: Information provided by ANEEL; Vagliasindi, M. and J. Besant-Jones (2013), Power Market Structure, http://dx.doi.org/10.1596/978-0-8213-9556-1.

Electricity generation

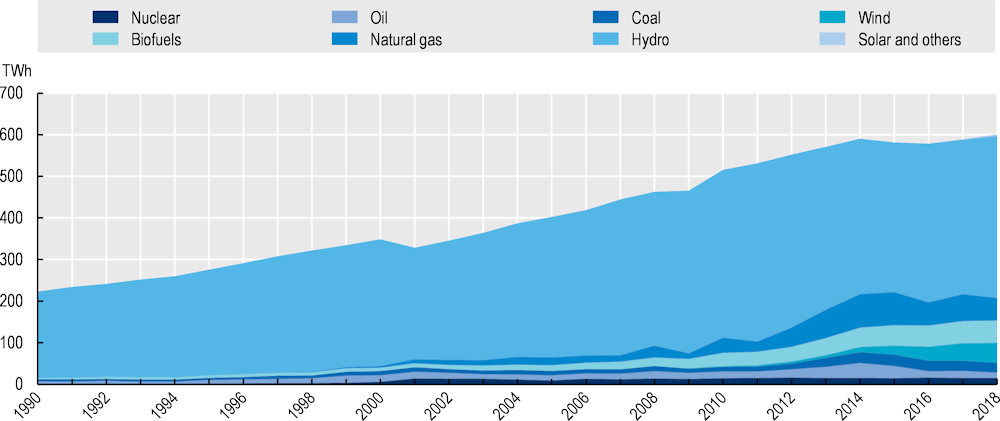

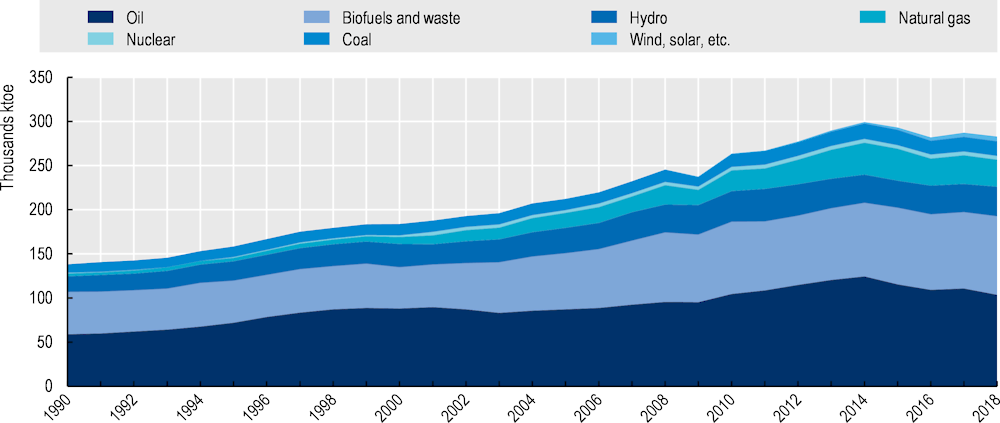

Electricity generation in Brazil is slowly transforming from a system dominated by hydro power to a more mixed system, due to the emergence of other types of electricity sources such as natural gas and renewable energy sources13 (wind, biofuels and solar). Hydro generation (in TWh) grew by 88% over the period 1990-2018, whereas total generation grew by 170% in the same period, explaining the decreasing dominance of hydro power (see Figure 1.2). While in 1990 93% of total electricity generation came from hydro power, this decreased to 65% by 2018 (IEA, 2020[23]). In terms of the total primary energy supply, renewables14 accounted for 45% of total energy supply in 2018 (see Figure 1.3), which ranks Brazil among the least carbon intensive countries in the World (IEA, 2020[24]).15

Looking into the future, the transmission system operator predicts the share of hydro power in total generation to be 62% (in TWh16) in 2024 (ONS, n.d.[25]). The IEA forecasts lower hydro capacity growth due to a lack of large-scale hydropower projects. Hydro power faces rising investment costs, as most of the remaining economical sites for hydro are limited and concerns over the environmental impact have been rising (IEA, 2019[26]). Together with the rise of sources such as wind and solar power, unevenly distributed throughout the country,17 this can create a more volatile energy system as the storage capacity in the system decreases. However, the stability of the system could improve due the rise of other generation sources, such as gas, as well as potential market reforms. Based on the Energy Operation Plan 2019-2013 by ONS, the total capacity of generation in the national transmission network will increase from 163 GW in April 2019 to 178 GW in December 2023, an increase of 9.3% (or 1.9% annually).18 ONS expects hydro power to grow by 4.5% over the same period, whereas gas-powered production will grow by 40%. According to ONS, the role of relatively flexible energy sources, such as gas, LNG and coal, will be crucial in future auctions.

Figure 1.2. Electricity generation in Brazil by source

Note: Classification in line with the IEA World Energy Statistics. Oil includes ‘fuel oil’, ‘refinery gases’, ‘gas/diesel oil excl. biofuels’ and ‘other oil products’. Coal includes ‘sub-bituminous coal’, ‘other bituminous coal’, ‘lignite’, ‘coal tar’, ‘coke oven gas’, ‘blast furnace gas’ and ‘other recovered gases’. Others includes ‘heat from chemical sources’.

Source: IEA (2020), “World energy statistics”, IEA World Energy Statistics and Balances, https://doi.org/10.1787/data-00510-en.

Figure 1.3. Total primary energy supply Brazil

Note: Classification in line with the IEA Extended World Energy Balances. Oil includes “crude oil”, "natural gas liquids”, “liquefied petroleum gases (LPG)”, “motor gasoline excl. biofuels”, “aviation gasoline”, “kerosene type jet fuel excl. biofuels”, “other kerosene”, “gas/diesel oil excl. biofuels”, “fuel oil”, “naphtha”, “lubricants”, “bitumen”, “petroleum coke” and “other oil products”. Biofuels and waste includes “primary solid biofuels”, “biogases”, “biogasoline”, “biodiesels”, “other liquid biofuels” and “charcoal”. Coal includes “coking coal”, “other bituminous coal”, “sub‑bituminous coal”, “lignite”, “coke oven coke” and “coal tar”. Wind, solar, etc. includes “solar photovoltaics”, “solar thermal” and “wind”.

Source: IEA (2020), IEA World Energy Statistics and Balances, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/enestats-data-en (accessed 4 May 2020).

Energy consumption

Table 1.3 summarises the electricity consumption by the different consumer classes in Brazil in 2019. According to the Energy Operation Plan by ONS, total demand for capacity in the system will increase from 68 733 MW in 2019 to 79 822 MW in 2023, or 3.8% annually. For 2019, EPE reports that 66% of total consumption came from the regulated market (ACR), while the other 34% was in the free market.19

Table 1.3. Electricity consumption 2019 in GWh by consumer classes in Brazil

|

ACR (captive market) |

ACL (free market) |

Total consumption |

Share in total consumption |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Residential |

142 777 |

4 |

142 781 |

30% |

|

Industrial |

29 136 |

138 548 |

167 684 |

35% |

|

Commercial |

72 371 |

19 703 |

92 075 |

19% |

|

Rural |

27 600 |

1 270 |

28 870 |

6% |

|

Public services, public power and street lighting |

44 294 |

3 266 |

47 560 |

10% |

|

Self-consumption |

3 114 |

143 |

3 257 |

1% |

|

Total |

319 292 |

162 934 |

482 227 |

100% |

Source: EPE (2020), Anuário Estatístico de Energia Elétrica 2020.

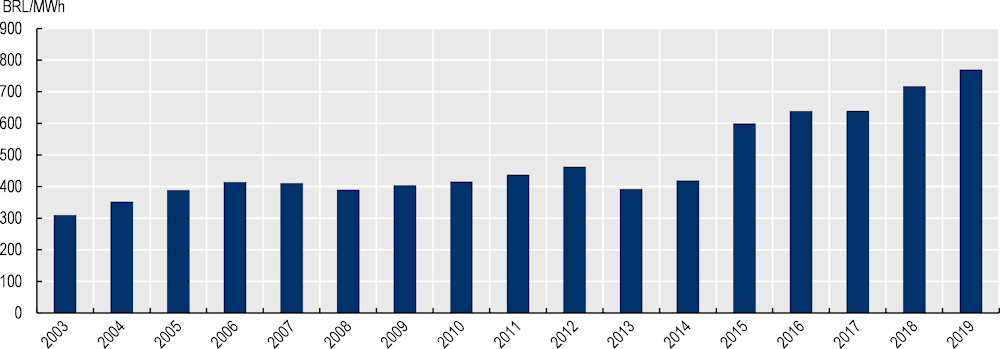

Figure 1.4. Average residential tariff (BRL/MWh) 2003-2019

Note: Prices refer to annual average prices as published by ANEEL for residential consumers. Prices are calculated by dividing total revenue by the electricity sales to residential consumers, and include all taxes.

Source: IEA (2020), IEA Energy Prices, 2020 edition (accessed 17 June 2020).

For 2010, the World Bank estimated the share of electricity in total expenditure for the average household at 4.91% (The World Bank, 2020[27]). The average residential tariff (including all taxes) increased from BRL 310 in 2003 to BRL 771 in 2019, which translates to an annual increase of 5.9% on average (see Figure 1.4). This increase is slightly higher than the annual inflation in Brazil over the period 2003-2019, which is 5.6%.20

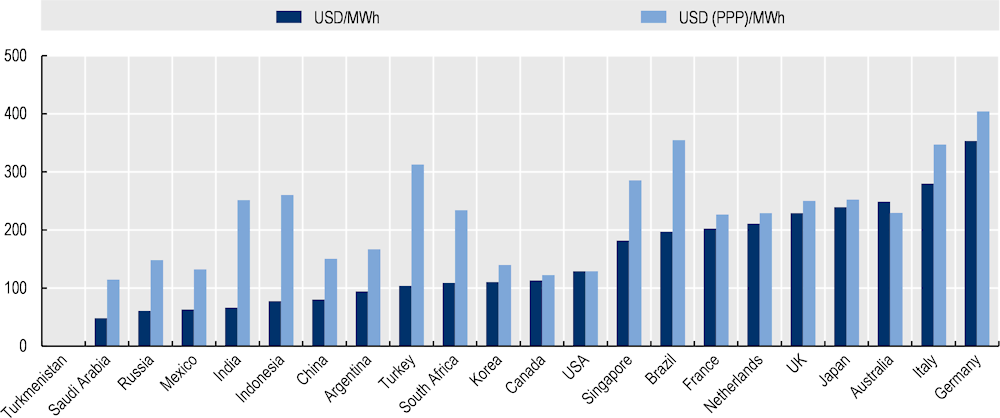

Put into international perspective, the residential tariffs in Brazil (for 2018) are somewhat at the higher end of the spectrum, significantly higher than tariffs in other Latin American countries (Mexico and Argentina) and countries that have hydro power as their main electricity source (such as Canada), as can be seen from Figure 1.5.

Figure 1.5. Residential electricity prices in global perspective in 2018

Note: The series USD (PPP)/MWh is calculated by using purchasing power parity adjusted exchange rates, to take into account differences in purchasing power between countries.

Source: IEA (2020), IEA Energy Prices, 2020 edition (accessed 17 June 2020).

Access to electricity in Brazil is widespread, partly due to the “Luz para Todos” initiative by the Brazilian government, which promotes electricity connections for households that did not have access to the network before (see Box 1.2). For 2018, IEA calculates that 99.8% of the Brazilian population has access to electricity, which is higher than the regional average for Central and South America (96.7%) (IEA, 2019[26]). Finally, ANEEL publishes information on the reliability of the electricity network on its website. Based on the information provided by distribution companies, the Brazilian consumer faced an average of 6.63 interruptions for 2019, resulting in an average 12.77 hours without electricity.21 These values show a significant decrease over time, as in 2010 consumers still faced an average of 11.31 interruptions, giving an average of 18.42 hours without electricity (ANEEL, n.d.[28]).

References

[11] ANEEL (2016), Informações para Empreendedores, https://www.aneel.gov.br/espaco-do-empreendedor/-/asset_publisher/uPv0Vn1PiOn9/content/encargos/654800?inheritRedirect=false (accessed on 4 September 2020).

[28] ANEEL (n.d.), Indicadores Coletivos de Continuidade (DEC e FEC), https://www.aneel.gov.br/indicadores-coletivos-de-continuidade (accessed on 15 June 2020).

[21] Costa, M., A. Lopes and G. de Pinho Matos (2015), “Statistical evaluation of Data Envelopment Analysis versus COLS Cobb–Douglas benchmarking models for the 2011 Brazilian tariff revision”, Socio-Economic Planning Sciences, Vol. 49, pp. 47-60, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.seps.2014.11.001.

[32] da Silva, A. et al. (2019), “Performance benchmarking models for electricity transmission regulation: Caveats concerning the Brazilian case”, Utilities Policy, Vol. 60, p. 100960, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jup.2019.100960.

[31] EPE (2019), Anuário Estatístico de Energia Elétrica 2019 - ano base 2018 (2019 Statistical Yearbook of electricity - 2018 baseline year), http://www.epe.gov.br/sites-pt/publicacoes-dados-abertos/publicacoes/PublicacoesArquivos/publicacao-160/topico-168/Anuário_2019_WEB.pdf.

[24] IEA (2020), Extended world energy balances, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/enestats-data-en (accessed on 4 May 2020).

[23] IEA (2020), “World energy statistics”, IEA World Energy Statistics and Balances (database), https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/data-00510-en (accessed on 14 April 2020).

[26] IEA (2019), Renewables 2019: Analysis and forecasts to 2024, International Energy Agency, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/b3911209-en.

[10] IEA (2005), Saving Electricity in a Hurry: Dealing with Temporary Shortfalls on Electricity Suppliers, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264109469-en.

[18] Lei n. 9.991, de 24 de Julho de 2000. (2000), Presidência da República, http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/LEIS/L9991.htm (accessed on 15 June 2020).

[8] Lei nº 10.848, de 15 de Março de 2004. (2004), Presidência da República, http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2004-2006/2004/Lei/L10.848.htm (accessed on 7 July 2020).

[19] Lei nº 12.783, de 11 de Janeiro de 2013. (2013), Presidência da República, http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2011-2014/2013/Lei/L12783.htm (accessed on 15 June 2020).

[14] Lei nº 13.334, de 13 de Setembro de 2016. (2016), Presidência da República, http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2015-2018/2016/Lei/L13334.htm (accessed on 7 July 2020).

[4] Lei nº 8.631, de 4 de Março de 1993 (1993), Presidência da República, http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/LEIS/L8631.htm (accessed on 7 July 2020).

[3] Lei Nº 9.074, de 7 de Julho de 1995 (1995), Presidência da República, http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l9074compilada.htm (accessed on 10 June 2020).

[5] Lei Nº 9.427, de 26 de Dezembro de 1996. (1996), Presidência da República, http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l9427cons.htm (accessed on 7 July 2020).

[6] Lei nº 9.478, de 6 de Agosto de 1997 (1997), Presidência da República, http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l9478.htm (accessed on 7 July 2020).

[7] Lei nº 9.648, de 27 de Maio de 1998 (1998), Presidência da República, http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/L9648cons.htm (accessed on 7 July 2020).

[20] Lopes, A. et al. (2020), “The Evolution of the Benchmarking Methodology Data Envelopment Analysis - DEA in the Cost Regulation of the Brazilian Electric Power Transmission Sector: a critical look at the renewal of concessions”, Gestão & Produção, Vol. 27/1, http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0104-530x3940-20.

[9] Melo, E., E. Neves and A. Da Costa (2009), The new governance structure of the Brazilian electricity industry: how is it possible to introduce market mechanisms.

[15] MME (2019), PROPOSTA COMPILADA DE APRIMORAMENTO CONTEMPLANDO, http://www.mme.gov.br/c/document_library/get_file?uuid=a57e14f4-35f5-ea25-b1c6-12f8b68f6a19&groupId=36131 (accessed on 15 June 2020).

[33] OECD (2020), “Key short-term indicators : Consumer Prices - Annual inflation”, Main Economic Indicators, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/mei-data-en (accessed on 14 April 2020).

[2] OECD (2008), OECD Reviews of Regulatory Reform: Brazil 2008: Strengthening Governance for Growth, OECD Reviews of Regulatory Reform, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264042940-en.

[34] ONS (2020), Boletim Mensal de Geração Eólica - Março/2020, http://www.ons.org.br/AcervoDigitalDocumentosEPublicacoes/Boletim_Geracao_Eolica_202003.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2020).

[30] ONS (2019), PEN Sumario Executivo 2019 - Plano da Operação Energética 2019 - 2023, http://www.ons.org.br/AcervoDigitalDocumentosEPublicacoes/PEN_Executivo_2019-2023.pdf.

[17] ONS (n.d.), O sIstema em numeros [The system in numbers], http://www.ons.org.br/paginas/sobre-o-sin/o-sistema-em-numeros (accessed on 14 April 2020).

[25] ONS (n.d.), Sistemas Isolados [Isolated Systems], http://www.ons.org.br/paginas/sobre-o-sin/sistemas-isolados (accessed on 14 April 2020).

[29] Paim, M. et al. (2019), “Evaluating regulatory strategies for mitigating hydrological risk in Brazil through diversification of its electricity mix”, Energy Policy, Vol. 128, pp. 393-401, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2018.12.064.

[16] Portaria nº 187, de 4 de Abril de 2019 (2019), DIÁRIO OFICIAL DA UNIÃO, http://www.in.gov.br/materia/-/asset_publisher/Kujrw0TZC2Mb/content/id/70268736 (accessed on 15 June 2020).

[13] Portaria nº 465, de 12 de Dezembro de 2019. (2019), DIÁRIO OFICIAL DA UNIÃO, http://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/portaria-n-465-de-12-de-dezembro-de-2019.-233554889 (accessed on 15 June 2020).

[12] Portaria nº 514, de 27 de Dezembro de 2018 (2018), DIÁRIO OFICIAL DA UNIÃO, http://www.in.gov.br/materia/-/asset_publisher/Kujrw0TZC2Mb/content/id/57219064/do1-2018-12-28-portaria-n-514-de-27-de-dezembro-de-2018-57218754 (accessed on 15 June 2020).

[27] The World Bank (2020), “Global Consumption Database”, World Development Indicators, http://datatopics.worldbank.org/consumption/country/Brazil (accessed on 14 April 2020).

[22] The World Bank (2019), Improving Performance of Electricity Distribution in Brazil, https://www.worldbank.org/en/results/2019/04/24/improving-performance-of-electricity-distribution-in-brazil (accessed on 14 April 2020).

[1] Vagliasindi, M. and J. Besant-Jones (2013), Power Market Structure, The World Bank, http://dx.doi.org/10.1596/978-0-8213-9556-1.

Notes

← 1. Next to the MME, the committee includes the ministers from the Ministry of the Economy, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Ministry of Agriculture, Casa Civil, the Ministry of Infrastructure, the Ministry of Science, Technology, Innovations and Communications, the Ministry of the Environment, the Ministry of Regional Development and the Ministry of the Institutional Security Office.

← 2. MAE no longer exists. It was replaced by the Electric Power Trading Chamber (Câmara de Comercialização de Energia Elétrica – CCEE) in 2004 as part of the second wave of reforms.

← 3. Based on information in the IEA World Energy Statistics data, 77% of total increase in generation (in GWh) between 1990 and 2000 can be attributed to an increase in hydro power generation.

← 4. The free market applies to consumers with a load above 2 MW as of 1 January 2020. This used to be 3 MW until 1 July 2019, and 2.5 MW between 1 July 2019 and 1 January 2020 (Portaria nº 514, de 27 de Dezembro de 2018, 2018[12]). Following ordinance 465/2019, the free market will expand further as the eligibility of consumers for the free market will increase. The free market will apply to all consumers with a load above 1 500 kW per 1 January 2021, to all consumers with a load above 1 000 kW per 1 January 2022, and per 1 January 2023 all consumers with a capacity above 500 kW should be able to buy their electricity freely (Portaria nº 465, de 12 de Dezembro de 2019., 2019[13]).

← 5. In 2018, 98% of all 12 831 free consumers are industrial or commercial consumers (EPE, 2019[31]).

← 6. The members include concession, permit and authorisation holders and consumers in the free market (ACL).

← 7. Changes in legislation include adjustments in the rules for concessions, see: law n. 13.299/2016 and decrees n. 8.828/2016, 9.143/2017, 9.192/2017 and 9.582/2018. For extensions of existing concessions, see: law n. 12.783/2013 and decrees n. 8.461/2015, 9.158/2017 and 9.187/2017. The regulation of the CDE follows from decree n. 9.022/2017. A reduction in subsidies for low-income households, among others, follows from decree n. 9.642/2018.

← 8. See: decrees n. 8.449/2015, 8.893/2016 and 9.271/2018.

← 9. Law n. 10,848/2004 determines that distribution companies may not carry out within the same company activities in electricity generation or transmission or the sale of energy to consumers in the free market, among other restrictions (Lei nº 10.848, de 15 de Março de 2004., 2004[8]).

← 10. The change led to a reduction in revenues for the companies involved (da Silva et al., 2019[32]).

← 11. The new remuneration system is based on an operational expenditures benchmark, as well as an allocation of quotas of physical guarantee of electricity to distribution concessionaires and quality standards as defined by ANEEL (Lei nº 12.783, de 11 de Janeiro de 2013., 2013[19]).

← 12. Among other cases, the Energy Reallocation Mechanism (Mecanismo de Realocação de Energia – MRE), a mechanism to limit the hydrological risk of hydro generators, has been at the basis of a wide range of legal procedures in the sector (Paim et al., 2019[29]).

← 13. Brazil aims to increase the use of renewables in its energy mix, as part of its pledge to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by 37% below 2005 levels in 2025, and 43% in 2030.

← 14. In Figure 1.3, renewables include the categories “hydro”, “biofuels and waste” and “wind, solar, etc.”.

← 15. In electricity generation, hydro, wind, solar and biofuels make up 82% of total generation in 2018 (in TWh), see Figure 1.2.

← 16. Based on capacity hydro power is expected to make up 60% of total generation in 2024, according to the Energy Operation plan 2019-2023 (ONS, 2019[30])

← 17. More than 80% of the installed wind power capacity is located in the Northeast (ONS, 2020[34]).

← 18. Annual growth rate = (1 + Total growth rate) ^ (1 / number of years) = (1 + 9.3%) ^ (1 / 4.667).

← 19. In total, for 2018 EPE reports 83 669 000 consumers in the regulated market (ACR) and 12 831 in the free market (ACL) (EPE, 2019[31]).

← 20. Based on CPI inflation measure as reported by the OECD Statistics database (OECD, 2020[33]). Calculated value is geometric mean over the period 2003-2019.

← 21. Analysis excludes interruptions shorter than 3 minutes. Information includes information on the reliability per distribution company, which shows a wide range of values among the companies. There are a number of distribution companies with no interruptions in 2019, while the highest duration of interruptions for a distribution company is 732.29 hours (more than 30 days) over 30.51 interruptions.