This chapter describes the main features of the sectors regulated by Peru’s telecommunications regulator (Organismo Supervisor de Inversión Privada en Telecomunicaciones, OSIPTEL). It also provides an overview of Peru’s public institutions, and institutional and regulatory reforms.

Driving Performance at Peru's Telecommunications Regulator

Chapter 1. Regulatory and sector context

Abstract

Institutions

Peru has a centralised system of government which is comprised of the executive, legislative and judiciary branches.

Executive

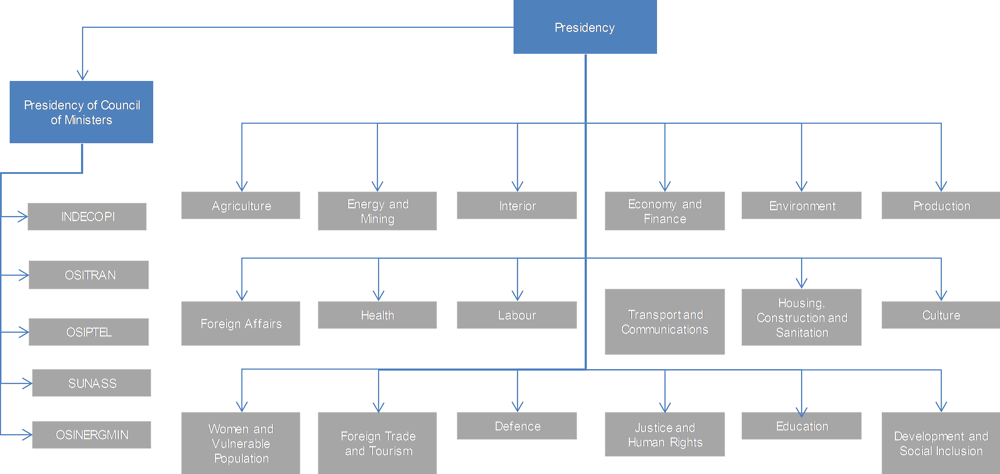

The President of the Republic, the Council of Ministers, and the Presidency of the Council of Ministers (Presidencia del Consejo de Ministros, PCM) constitute the core bodies of the executive branch (see Figure 1.1, (OECD, 2016[1]). Along with the PCM, the Ministry of Economy and Finance (Ministerio de Economía y Finanzas, MEF) and the Ministry of Justice and Human Rights (Ministerio de Justicia y Derechos Humanos, MINJUS) help shape the overall regulatory environment in Peru. In the telecommunications sector, the Ministry of Transport and Communications (Ministerio de Tranporte y Comunicaciones, MTC) and other public bodies, such as the National Institute for the Defense of Competition and Intellectual Property (Instituto Nacional de Defensa de la Competencia y Protección de la Propiedad Intelectual, Indecopi), also work closely with OSIPTEL to improve regulatory policy in the sector.

Figure 1.1. Structure of the executive branch of the Peruvian government

Note: The PCM also houses a large number of public entities, secretariats and commissions, which are not included in this figure.

Source: (OECD, 2016[2]), Regulatory Policy in Peru: Assembling the Framework for Regulatory Quality, OECD Reviews of Regulatory Reform, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264260054-en.

Presidency of the Council of Ministers (PCM)

The Presidency of the Council of Ministers (PCM) is responsible for co-ordinating national and sector policies within the executive, including line Ministries and public agencies. The PCM houses several secretariats and commissions, and manages and co-ordinates line ministries and public entities, as defined by law. The PCM oversees and provides guidance on the general administrative processes within OSIPTEL and plays a key role in appointing and nominating the President and the members of the Board of the regulator, as well as administering budget allocations and disbursements. The PCM is currently developing guidelines and functions to strengthen its regulatory oversight role in the Peruvian administration. While not formally defined in law, the President of the Council of Ministers in practice plays the role of Prime Minister and government spokesperson (OECD, 2016[1]).

The PCM houses several public entities, secretariats and commissions. Of these, OSIPTEL mainly interacts with two entities: the National Centre for Strategic Planning (Centro Nacional de Planeamiento estratégico, CEPLAN) and National Civil Service Authority (Autoridad Nacional del Servicio Civil, SERVIR):

CEPLAN is a specialised technical body that is responsible for overseeing the national development plan as well as ensuring that sectoral, strategic, and operational plans of concerned government bodies are developed according to the National System of Strategic Planning (SINAPLAN, see Box 1.1). CEPLAN also monitors compliance and ensures that objectives and indicators set by the executive body are not contradictory with other sectoral or national plans.

SERVIR sets human resources policies for the Peruvian public sector,1 including OSIPTEL. It is responsible for orienting, monitoring, and managing human resource development, such as those relating to performance evaluations, information systems, remuneration, incentives and codes of conduct. Under the new SERVIR employment regime (see Box 2.2) the Body of Public Managers (Cuerpo de Gerentes Públicos, CGP) will be also responsible for carrying out the selection process for managerial positions. Under the new SERVIR 412 public entities have started the implementation of the new regime; however, as of 2018, no public entity has fully implemented the regime. Therefore, SERVIR has not selected managerial positions at OSIPTEL so far.

Box 1.1. Peru’s National Strategic Development Plan (PEDN) and the National System of Strategic Planning (SINAPLAN)

In 2011, the government developed the National Strategic Development Plan (Plan Estratégico de Desarrollo Nacional, PEDN), which sets the strategic objective, policy guidelines, goals, and projects of the government for the next ten years. The plan consists of six strategic axes: “i) fundamental rights and dignity of persons; ii) opportunities and access to services; iii) state and governability; iv) economy, competitiveness, and employment; v) regional development and infrastructure; and vi) natural resources and environment” (CEPLAN, 2018[3]). The plan serves as guidance rather than a long‑term action plan and provides flexibility in meeting goals in the medium-term by establishing annual goals every five years. The national plan was last updated in October 2015 and entitled as to include scenarios and targets for the country by 2021 (CEPLAN, 2018[4]).

The PEDN therefore serves as the National Centre for Strategic Planning’s (CEPLAN) guidance for the application of the National System of Strategic Planning (Sistema Nacional de Planeamiento Estratégico, SINAPLAN). SINAPLAN is an articulated set of systems and co-ordination mechanisms to assure the viability of and co-operation in the national planning process and promote sustained development in the country (CEPLAN, 2018[4]).

Entities that make up the SINAPLAN include the three branches of government (executive, legislative, and judicial), autonomous constitutional organisations, sub-national governments, and the national forum that includes political parties and civil society organisations.

Source: (CEPLAN, 2018[3]), Politicas y Planes, http://www.ceplan.gob.pe/politicas-y-planes/ (accessed on 22 June 2018); (CEPLAN, 2018[4]), Qué es el Sinaplan?, http://www.ceplan.gob.pe/sinaplan/ (accessed on 22 June 2018); (OECD, 2016[5]), Multi-dimensional Review of Peru: Volume 2. In-depth Analysis and Recommendations, OECD Development Pathways, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264264670-en.

Ministry of Economy and Finance (MEF)

The Ministry of Economy and Finance (MEF) is responsible for the development of economic and financial policy in the country and plays an equally important role in regulatory quality efforts. MEF manages the performance-based budgeting system, which apply to all executive bodies and economic regulators, as well as other activities on regulatory policy related to administrative simplification, international regulatory co‑operation, inter-governmental co-ordination, performance-based regulation, ex ante impact assessments of regulation, and governmental transparency and consultation. It has the capacity to assess draft policies with potential impact on commerce and other cross‑cutting issues (OECD, 2016[2]).

The ex ante and ex post impact assessments began in 2010 under the leadership of the General Directorate of Public Budget (Dirección General de Presupuesto Público) of MEF, which directs, participates and supervises each of the stages of the evaluation process. Evaluated interventions can be activities, projects, programs or policies in progress or completed. To date, impact evaluations of public interventions of various sectors such as Education, Agriculture, Social Inclusion, Work, Citizen Security and Health have been developed.2 In parallel, the Subsecretariat for Simplification and Regulatory Analysis (Subsecretaría de Simplificación y Análisis Regulatorio) implements methodologies and actions for Regulatory Impact Analysis (RIA) in the regulatory training process, in its areas of competence. It also issues opinions and advises public entities on the adequacy of the regulatory impact analysis in the regulatory training process (article 45 Regulation of Organization and Functions of the PCM, Supreme Decree 22‑2017-PCM).

Attached to MEF is the Agency for the Promotion of Investment (Agencia de Promoción de la Inversión Privada, ProInversión), which is a specialised technical body responsible for the promotion of national investments through public-private partnerships (PPPs) in services, infrastructure, assets, and other state projects. It also responsible for providing information and orientation services to investors, mediating different views on investment projects, and creating a conducive environment for attracting private investments, in accordance with economic plans and integration policies, such as those related to the development of telecommunications infrastructure. ProInversión receives technical comments from OSIPTEL, MEF and the MTC when developing investment projects; however, only MEF and the MTC opinions are considered binding.

Ministry of Justice (MINJUS)

MINJUS acts as a legal advisory body for the executive branch. It has a broad mandate to improve the quality of the rule of law and act as a legal quality check for draft regulations. Together with the PCM and MEF, it is considered among the most influential ministries in the executive branch. MINJUS ensures that the executive branch performs its duties within the political constitution of Peru by providing legal advice and opinions on regulatory initiatives. It is also the agency within the executive branch responsible for co-ordinating with the judicial branch, the public prosecutor, and related entities within the judicial system.

Ministry of Transport and Communications (MTC)

The Ministry of Transport and Communications (MTC) is responsible for defining and developing policies for Peru’s transportation systems and telecommunications sector. It is in charge of designing, leading, promoting, and implementing actions aimed at providing efficient transportation and telecommunication systems and overseeing concession programmes within its sectors. This is done in conjunction with control bodies and sectoral institutions that supervise the proper operation of telecommunications and transport activities, namely two of the country’s four economic regulators: OSIPTEL and OSITRAN.

The MTC establishes the general policy and direction of the telecommunications sector and oversees the implementation of various projects, such as those undertaken through the Telecommunications Investment Fund (Fondo de Inversión en Telecomunicaciones, FITEL). The MTC is responsible for assessing, processing, and supervising requests related to the operation of open-signal radio, radio spectrum, and television stations and the provision of private telecommunications services.

Independent regulatory bodies

Regulatory authorities

Peru created four economic regulators in the 1990s as part of a broader policy built on the pillars of economic liberalisation, private investment attraction and regulated competition. These authorities exist today under the following names: the Supervisory Agency for Private Investment in Telecommunications (Organismo Suupervisor de Inversión Privada en Telecomunicaciones, OSIPTEL), the Supervisory Agency for Investment in Energy and Mining (Organismo Supervisor de la Inversión en Energía y Minería, OSINERGMIN),3 the Supervisory Agency for Investment in Public Transport Infrastructure (Organismo Supervisor de la Inversión en Infraestructura de Transporte de Uso Público, OSITRAN), and the National Superintendence of Sanitation Services (Superintendencia Nacional de Servicios de Saneamiento, SUNASS).4 They were created to foster competition and promote infrastructure investment following the liberalisation of the economy. The defining features of these entities are: 1) institutional design as administratively independent bodies of the central government; 2) funding scheme through industry contributions; and 3) collegiate decision-making body.

Competition and consumer protection authority

In addition to the four economic regulators, the National Institute for the Defense of Free Competition and the Protection of Intellectual Property (Instituto Nacional de Defensa de la Competencia y de la Protección de la Propiedad Intelectual, Indecopi)5 was created in 1992 as an independent regulatory body in charge of enforcing competition law and intellectual property law.6 Since 2010, Indecopi is also responsible for protecting consumers across the economy as the National Consumer Protection Authority, exercising its duties within the framework of the National Consumer Protection and Defense Policy, and based on four strategic pillars: 1) education, orientation, and dissemination; 2) protection of consumer health and safety; 3) mechanisms for the prevention and solution of conflicts between providers and consumers; and 4) strengthening of the National Integrated Consumer Protection System.

It has the authority to make binding decisions over sanctions or penalties for violations in accordance with Law 29571, Code for the Protection and Defense of the Consumer (Código de Protección y Defensa del Consumidor). Penalties are capped at 50 tax units (PEN 207 500) for minor infractions, 150 tax units (PEN 622 500) for serious infractions and 450 tax units (PEN 1.9 million) for very serious infractions.7

Since 2013, Indecopi has been conducting ex post reviews of regulations within their jurisdiction and has eliminated nearly 3 000 regulations in the country. Importantly, in the telecommunications sector, competition functions are retained by the economic sector regulator rather than Indecopi, except for unfair competition related to advertising. With regard to consumer protection, Indecopi is responsible for hardware-related issues whereas, OSIPTEL, which also has consumer protection functions within the telecommunications market, is responsible for service-related issues.

Indecopi chairs the National Consumer Protection Council, an inter-institutional working group created for the integration of the local and national statutory framework on consumer protection, as well as to bolster activities carried out for the benefit of consumers and to identify common information campaigns. The Council is made up of 16 representatives from the public and private sectors: ministries, utilities regulators, business associations, and consumers associations, in co-ordination with the PCM. At the time of writing, Osinergmin has been nominated to represent all other regulators on the Council.

Legislature

The legislative branch of Peru is conferred to the Congress. The Congress is a unicameral institution composed of 130 members elected to serve five-year terms. Its current composition is the result of a reform passed in 1993 following the Democratic Constituent Congress that resulted in the new Political Constitution (OECD, 2016[1]). The Congress holds the authority to pass legislation that requires regulators to develop secondary regulations. Furthermore, the Congress can call on ministries and the regulators for them to submit opinions on draft laws and attend sessions to respond to any questions that raised by Congress. There are currently twenty-three (23) standing committees, including the Commission for Consumer Defence and Regulators of Public Utilities (Comisión de Defensa del Consumidor y Organismos Reguladores de los Servicios Públicos, CODECO), the Commission for Budget (Comisión de Presupuesto y Cuenta General de la República), and Commission for Transport and Communications (Comisión Transporte y Comunicaciones).

Subnational governments

There are three subnational layers of government in Peru: the regional government, the provincial local government and the district local government (OECD, 2016[2]). These government levels have exclusive and joint functions which are described in the Peruvian Political Constitution (Constitución Política del Perú, CPP), the Organic Law of the Executive Power (Ley Orgánica del Poder Ejecutivo, LOPE, the Organic Law of Regional Governments (Ley Orgánica de Gobiernos Regionales, LOGR) and the Organic Law of Municipalities (Ley Orgánica de Municipalidades, LOM). Sub-national governments have the authority to enact regulatory measures in their region. OSIPTEL’s decentralised offices (DO) are responsible for inter alia liaising with regional governments.

Judiciary

The judiciary is responsible for interpreting and applying the laws in Peru to ensure equal justice. It is responsible for providing mechanisms for dispute resolutions through a hierarchical system. The judiciary is led by the Supreme Court and is supported by 28 superior courts with defined jurisdictions across the 25 regions in the country. Under each superior court are 195 primary courts responsible for each province and 1 838 Courts of justice of the Peace within each district (Poder Judicial del Peru, 2012[6]). In the telecommunications sector, dispute resolution between regulated entities, as well as between regulated entities and users, are first handled via OSIPTEL’s dispute resolution bodies. If the parties wish to appeal further, they can launch a “contentious administrative process” under Law No. 27584 via the judiciary. The judiciary makes the final decision on the case, which can be decided based on both the merit of the issue as well as the process. In addition, it is possible for regulated entities to utilise arbitration mechanisms for dispute resolutions, which is not part of the judiciary. Some entities prefer this route over entering into full judicial review.

Supreme audit institution

The Comptroller General of the Republic (Contraloría General de la República del Perú, CGR) was established in 1929 as the supreme audit institution of Peru. As the highest authority of the national control system, the CGR supervises, monitors and verifies the correct application of public policies and the use of state resources and assets. It is represented in each government body, including OSIPTEL, by the Institutional Control Body (Órgano de Control Institucional, OCI). The Chief Audit Officer of the OCI and is assigned by the General Comptroller of the Republic and its function is the correct and transparent management of resources and assets of OSIPTEL, safeguarding the legality and efficiency of its acts, as well as the achievement of its management goals, through the execution of control tasks. The rest of the audit staff are employed by the government agency. The OCI is responsible for all auditing all public spending; for example, by monitoring the procedure and evaluation process related to contracts, procurement, and other services.

Regulatory process and policy

Legislative process

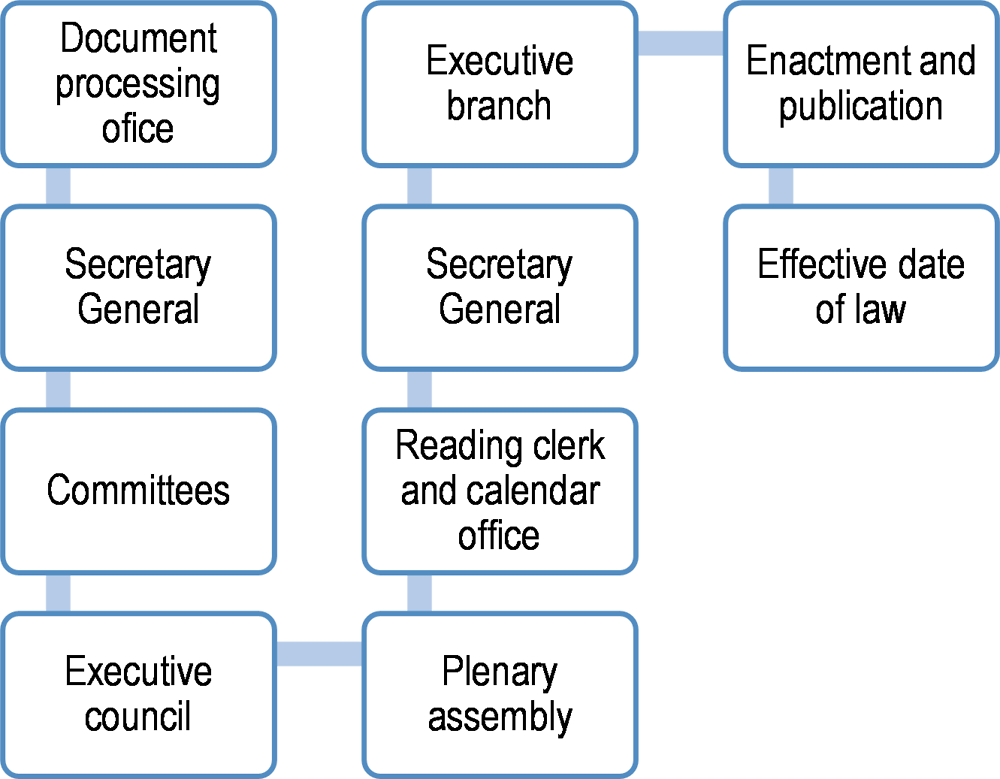

Aside from the members of Congress, the President, the judiciary, autonomous public bodies, professional associations, and the citizenry are authorised to submit bills to Congress for consideration (see Figure 1.2).

Once a draft bill is submitted, it is registered by the office of the Congress and processed by the Secretary General of the executive council, who is also responsible for identifying the committee(s) that receive(s) the bill and sets the hierarchy of each committee. The assigned committee deliberates and issues a report within 30 days of reception and classifies it as favourable, unfavourable, or flat rejection. If the proposition is received by other committees, committees are welcome to submit joint or individual reports. If approved, the committee reports are received by the executive council, which includes the Secretary General, the Parliamentary Director, and the reading clerk, who will also be organising the debate and co-ordinating the distribution of the copies to the members of parliament. The plenary assembly then accepts or rejects the bill. An accepted bill is then enrolled, reviewed, and certified by the Office of the Secretary General and passed to the executive branch. The president then signs the bill into law and orders its publication, which then comes into force once published in the official gazette, El Peruano. If there are objections, the President may return the bill to Congress within 15 days. Without a decision from the executive within 15 days, the Congress may pass the bill into law (Congreso de la República, 2017[7]).

If within its jurisdiction, regulatory agencies are entitled to formulate secondary legislations linked to the law, following the guidelines for the regulatory quality assessment of administrative procedures (Presidencia del Consejo de Ministros, 2018[8]).

Figure 1.2. Peru’s legislative process

Source: (Congreso de la República, 2017[9]), Legislative Process, http://www.congreso.gob.pe/eng/legislative_process/ (accessed on 26 June 2018).

Rule-making process in the executive body

The executive branch has the authority to issue subordinate regulations (decrees and resolutions). It is also responsible for approving bills (draft laws) that is submitted by the President to Congress, including any legislative decrees, emergency decrees, and resolutions, as defined by law (OECD, 2016[2]).

The rule-making process in the executive is not guided by a whole-of-government policy, but certain policies and framework serve as materials in the development of regulations (see Table 1.1).

Table 1.1. Frameworks and policies that guide rule-making in the executive body

|

|

Name |

Description |

|---|---|---|

|

Law No. 26889 |

Framework Law for Legislative Production and Systematisation |

|

|

Law No. 27444 |

General Administrative Procedure Law |

|

|

Reglamento |

|

|

|

Manual of legislative technique |

|

Source: (OECD, 2016[2]), Regulatory Policy in Peru: Assembling the Framework for Regulatory Quality, OECD Reviews of Regulatory Reform, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264260054-en.

When issuing subordinate regulations, the common practice among ministries is to draft a proposal, guided by the frameworks and policies outlined in Table 1.1, and posted on the website for public consultation. After consultation, the head of the ministry or agency approves the regulation. For ministries, vice-ministers would also need to approve the draft before it is sent to the minister. In cases when draft regulations require approval from three or four ministries and/or agencies, the proposal must be sent to the PCM to be discussed by the vice-ministerial co-ordinating council (CCV) or adopted by the Council of Ministers before it is sent to the President of the Republic for final approval. All approved proposals are published in the official gazette, El Peruano. (OECD, 2016[2])

Box 1.2. OECD Regulatory Policy Review of Peru

In 2016, the OECD conducted a review of the regulatory policy of Peru to assess the policies, institutions, and tools utilised by the government and regulatory bodies in the country in designing, implementing, and enforcing high-quality regulations. This review formed part of the OECD Peru country programme along with four other reviews of sectoral public policy in Peru.

The report provides an overall assessment of the political context of regulatory reform carried out by oversight bodies and relevant regulatory agencies in the country. It recognises the progress achieved to date, including the numerous tools and activities – such as a broad administrative simplification programme – utilised to improve the regulatory environment in the country. The report also highlights the challenges and improvements that remain in order to achieve a world-class regulatory framework and provides a set of recommendations and next steps, including:

establishing a regulatory oversight body, as a way to create more coherence in regulatory policy activities and tools across ministries, agencies, and offices;

issuing a policy statement – either through a law or a binding legal document – on regulatory policy, with clear objectives, strategies, and tools when managing the entire regulatory governance cycle;

measuring administrative burdens created by formalities and information obligations;

making inspection and enforcement of regulations an integral part of the regulatory policy framework, including through developing a set of guidelines related to ethical behaviour and corruption prevention;

promoting a coherent national regulatory framework that actively encourages the adoption and use of regulatory tools and best-practice sharing.

In addition, the report provides a brief overview of the governance arrangements of regulators and their interactions with the central government. It underscores the degree of independence exerted by regulators on budget and decision making, their transparency and accountability mechanisms, as well as an overview of the regulatory policy tools applied throughout the policy cycle. Economic regulators are considered to implement more sophisticated tools than other government bodies and have progressively improved its adoption and implementation.

Following the report, the Presidency of the Council of Ministers (PCM) has been proactive in developing initiatives and co-ordinating with ministries and regulatory bodies to improve the national regulatory framework. For example, in 2017, the PCM developed a set of guidelines for the regulatory quality assessment of administrative procedures to further improve the regulatory environment for citizens and businesses. The guidelines aim to guide government bodies under their purview in identifying, reducing and measuring administrative burdens created by formalities and information obligations in both the local and the national level.

Source: (OECD, 2016[2]), Regulatory Policy in Peru: Assembling the Framework for Regulatory Quality, OECD Reviews of Regulatory Reform, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264260054-en.

Sector context and main regulatory reforms

The telecommunications law enacted in 1991 created OSIPTEL as the economic regulator to lead the transformation and modernisation of the telecommunications sector and, in 1994, replaced the Committee of the Regulation of Telecommunications Tariffs. The privatisation of two state telephone companies, Compañía Peruana de Teléfonos (CPT) and Empresa Nacional de Telecomunicaciones (ENTEL), in 1994 also paved the way towards the modernisation of the Peruvian telecommunications sector.8

Prior to OSIPTEL’s creation, limited and inefficient coverage of telecommunications services was an issue, notably in the rural areas. During its first years of operation, OSIPTEL’s objectives were to increase investment, geographic coverage and quality of services. It also set the first consumer protection frameworks for the sector, including information relating to the design of user service platforms as well as maximum timelines for service solutions. The regulator’s and the government’s overarching goal of improving services in rural areas was supported with the creation of the Telecommunications Fund (Fondo de inversion en telecomunicaciones, FITEL) (Box 1.3)

Box 1.3. Telecommunications Investment Fund (FITEL)

The Telecommunications Investment Fund (Fondo de Inversión en Telecomunicaciones, FITEL) was established through Peruvian Telecommunications Law Supreme Decree 013-93 in 1994 and originally administered by OSIPTEL. In 2006, the Fund was transferred from OSIPTEL to the Ministry of Transport and Communications (MTC). FITEL is aimed at facilitating universal access to essential telecommunications services in rural areas and places of social interest.1

FITEL is managed by a three-member decision-making body: the President is the Minister of Transport and Communications, while the Minister of Economy and Finance and the President of OSIPTEL serve as the other members. FITEL is staffed with 120 people who carry out policy formulation, promotion and supervision functions. Policy is set by the MTC, while formulation is guided by MEF principles that require social and economic viability as well as benefit for the country. Promotion is also carried out in accordance with rules set by MEF.

The Fund subsidises the installation, operation, and use of public telecommunications services in the rural areas to achieve universal access. It is sourced from 1% of the gross income of service operators and carriers in the telecommunications sector as well as fines collected from non-compliance or violations. In 2018, the total budget for FITEL was nearly PEN 400 million.

Projects financed by FITEL include telecommunications projects and studies presented through a public tender by ProInversión. These projects can focus on activities related to investments in infrastructure, operation, maintenance and supervision, skills development, as well as procurement and purchase of new equipment or technology. The individual or enterprise with the lowest required subsidy wins the bidding process. (OSIPTEL, 2014[10])

Projects are prioritised in accordance with an annual plan. OSIPTEL attends monthly meetings with FITEL decision-making body, which allows them to present proposals for projects for approval and funding. To date, FITEL has carried out over 27 projects in the country and are currently executing 11 projects as of August 2018 (investment phase), with the majority focused on improving broadband connectivity in identified areas (FITEL, 2018[11]) to provide internet for health, education and security purposes.

Projects are deployed using either Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) or Projects in Assets (Proyectos en Activos), which allows ministries, regional governments and local governments to promote private investments of assets owned by the respective Private Investment Promotion Board (Organismo Promotor de la Inversión Privada, OPIP). For projects implemented under the latter scheme, OSIPTEL cannot issue binding opinions over issues that intersect with their competencies, i.e. concession contracts, tariffs, quality of service, essential facilities, and competition. OSIPTEL can also be tasked with creating ad hoc regulations in accordance with specific projects. Moreover, for telecommunications projects implemented under this scheme, responsibility for supervising the quality of services is assigned to FITEL, which can run the risk of duplicating efforts with OSIPTEL who supervise quality of service in all other areas of the telecommunications sector.

1. Qualified rural areas are based on the definition provided by the National Statistics and Information Institute (Instituto Nacional de Estadísticañ e Informática, INEI): (1) are less than 3 000 inhabitants (as measured by INEI); (2) have a shortage of basic services; and (3) have less than 2% of telephone density. Places of social interest include: (1) population centres first to third quintile of the poverty map, as defined by the Social Development and Compensation Fund (Fondo de Cooperación para el Desarrollo Social, FONCODES); (2) do not have at least 1 public service for essential telecommunications services; (3) have less than 1 public telephone line per 500 inhabitants; or (4) are localities located in the border districts. (MTC, 2010[12]).

Source: (MTC, 2010[13]), FITEL Telecomunicaciones para áreas rurales de Perú Agenda • ¿Qué es FITEL?, http://www.cedecap.org.pe/uploads/archivos/mesaplanesnacionales_irmamora-fitel.pdf (accessed on 05 November 2018); (OSIPTEL, 2014[10]), The Telecommunications Boom, OSIPTEL, https://www.osiptel.gob.pe/Archivos/Publicaciones/boom_telecomunicaciones/boom_telecomunicaciones_osiptel.html#6, (FITEL, 2018[11]), Estado de los Proyectos del Fitel, http://www.fitel.gob.pe/pg/proyectos-supervision.php (accessed on 22 June 2018); (MEF, n.d.[14]), Proyectos en Activos, https://www.mef.gob.pe/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=4437&Itemid=102247&lang=es (accessed on 02 November 2018), (MTC, 2010[12]), FITEL: Telecomunicaciones para áreas rurales de Perú, http://www.cedecap.org.pe/uploads/archivos/mesaplanesnacionales_irmamora-fitel.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2018).

In the 1990s, users had to pay for both calls initiated and received, which greatly constrained the expansion of public telecommunications services. Based on analysis and consultations, OSIPTEL introduced a new rate system that passed the cost to the calling party for fixed and mobile services in 1996 (OSIPTEL, 2014, p. 68[10]). This reform resulted in an increase of mobile-to-mobile and fixed-to-mobile traffic as well as a reduction of rates in the medium-term. Following the arrival of new operators in the fixed market, OSIPTEL established price cap rate formula that reduced rates on a quarterly basis and, through a productivity factor, transferred efficiency improvements obtained by the company to the users. A number of reforms followed suit, including those regulating long distance calls, public payphones, and fee collection.

For the first decade of existence, OSIPTEL’s mandate was focused on transitioning to a liberalised telecommunications market through promoting competition and facilitating new entrants into the market. Up to the early- to md-2000s, several companies entered the mobile market, namely TIM, Nextel, Bellsouth and America Móvil. TIM was later acquired by America Móvil, and Bellsouth was acquired by Telefonica. As of 2018, America Movil and Telefonica are still in the market, while in 2014 Nextel became ENTEL and Viettel entered the market.

Expansion of operators was part of a larger effort to expand services, especially in the mobile sector, that lasted from 2005 to 2014. Over this period, the quantity of districts with coverage went from less than 500 to more than 1 500. Following this period, OSIPTEL’s mandate shifted towards a regulatory policy concentrated on strengthening competition through access conditions and setting prices of essential facilities to promote rapid and efficient entry to the market. Most recently, this mandate has focused on promoting competition in the mobile markets and reducing barriers to entry, namely in regards to reducing costs for consumers to switch providers. This mandate is reflected in the regulator’s current slogan: promovemos la competencia y empoderamos al usuario (we promote competition and empower the user).

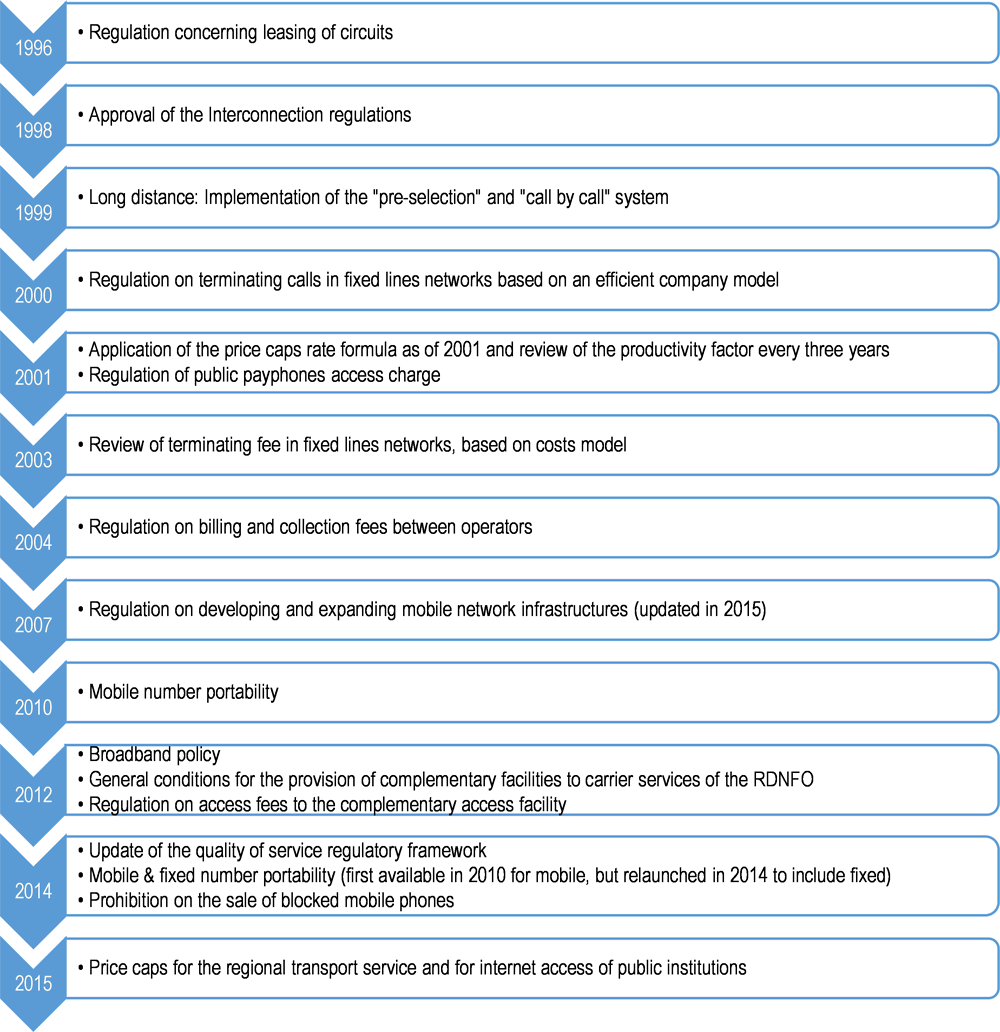

Even after OSIPTEL efforts, there were lots of uncover areas. Thus, other major reforms of the regulatory framework delivered by OSIPTEL include those in relation to the 2012 broadband policy via the establishment of the national fibre optical backbone (Red Dorsal Nacional de Fibra Optica, RDNFO) and promotion of broadband connections. Figure 1.3 describes other major reforms implemented by OSIPTEL to improve sector performance.

Figure 1.3. Major reforms to promote competition in the telecommunications sector

Source: (OSIPTEL, 2014[15]), El Boom de las Telecomunicaciones - OSIPTEL, https://www.osiptel.gob.pe/Archivos/Publicaciones/boom_telecomunicaciones/files/assets/basic-html/index.html#1/z#noFlash (accessed on 22 June 2018).

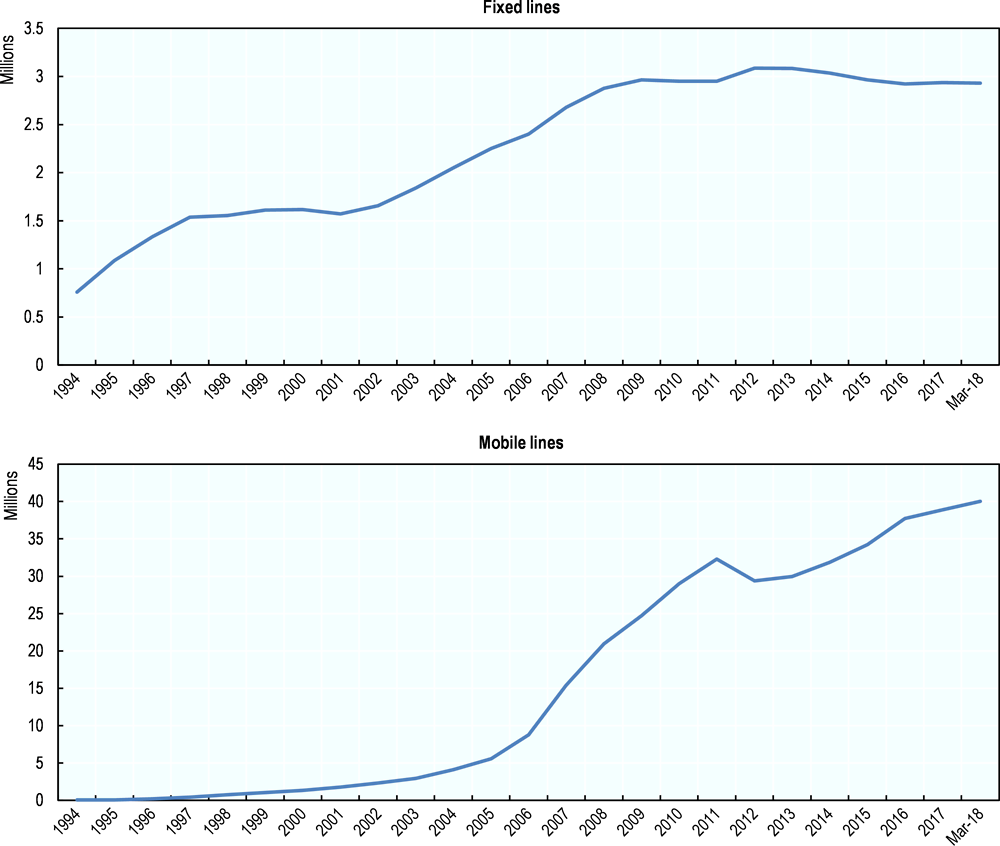

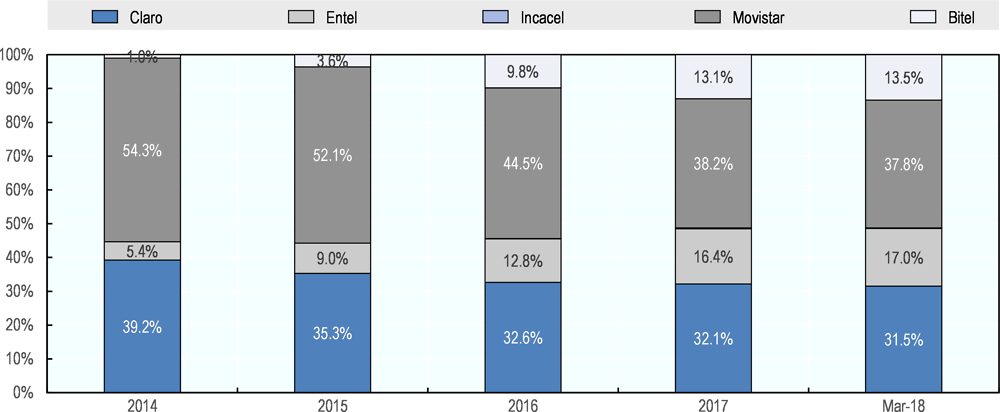

The Peruvian telecommunications sector underwent one of the most dynamic modernisation processes in the country, linked to the advent and growth of new services (mobile telephony and internet) and the arrival of new providers to the market. As of 2018, there are 5 large operators and more than 100 small- and medium-sized enterprises providing telecommunication services in the country, with Telefónica as the largest player and leader in mobile telephony. Table 1.2 shows the number of users for all sub-sectors in 2018, Figure 1.4 demonstrates the growth of fixed and mobile lines from 1994 to 2018, and Figure 1.5 shows the evolution of market concentration for mobile telephony 2014-17. UN statistics show that Peru’s population in 2017 was over 32 million, while the number of households was 8.3 million (Euromonitor International, 2018[16]).

Table 1.2. Users by telecommunication subsector (March 2018)

|

Sub-sector |

Number of users |

|---|---|

|

Mobile lines |

40 020 419 |

|

Mobile internet |

22 920 990 |

|

Fixed telephone |

2 930 161 |

|

Fixed internet |

2 350 218 |

|

Pay television |

1 979 762 |

Note: Consistent data on mobile internet was not available at the time of writing this report. According to (Euromonitor International, 2018[16]), total population of Peru in 2017 was approximately 32 million people.

Source: Information provided by OSIPTEL, 2018.

Figure 1.4. Growth of fixed and mobile lines in service in Peru, 1994-2013

Source: (OSIPTEL, 2014[15]), El Boom de las Telecomunicaciones - OSIPTEL, https://www.osiptel.gob.pe/Archivos/Publicaciones/boom_telecomunicaciones/files/assets/basic-html/index.html#1/z#noFlash (accessed on 22 June 2018).

Figure 1.5. Evolution of market concentration in mobile telephony, 2014-17

Source: (OSIPTEL, 2018[17]), Reporte Estadístico - Febrero 2018, https://www.osiptel.gob.pe/Archivos/Publicaciones/reporte-estadistico_feb2018/files/assets/basic-html/index.html#1 (accessed on 22 June 2018).

Mobile penetration is notably high in urban areas. In contrast, there remains an urban-rural divide in terms of access to fixed or fixed-to-mobile services, owing to the challenging geographical landscape as well as size of the country and remote location of smaller, more insulated communities. The rural population has diminished in relative terms, representing 22.5% of the total Peruvian population in 2017, compared to 28% in 2007.

References

[3] CEPLAN (2018), Politicas y Planes, http://www.ceplan.gob.pe/politicas-y-planes/ (accessed on 22 June 2018).

[4] CEPLAN (2018), Qué es el Sinaplan?, http://www.ceplan.gob.pe/sinaplan/ (accessed on 22 June 2018).

[7] Congreso de la República (2017), How does a bill become a law?, http://www.congreso.gob.pe/eng/legislative_process/ (accessed on 26 June 2018).

[9] Congreso de la República (2017), Legislative Process, http://www.congreso.gob.pe/eng/legislative_process/ (accessed on 26 June 2018).

[16] Euromonitor International (2018), Peru Country Factfile, https://www.euromonitor.com/peru/country-factfile (accessed on 29 August 2018).

[11] FITEL (2018), Estado de los Proyectos del Fitel, http://www.fitel.gob.pe/pg/proyectos-supervision.php (accessed on 22 June 2018).

[14] MEF (n.d.), Proyectos en Activos, https://www.mef.gob.pe/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=4437&Itemid=102247&lang=es (accessed on 02 November 2018).

[13] MTC (2010), FITEL Telecomunicaciones para áreas rurales de Perú Agenda • ¿Qué es FITEL?, http://www.cedecap.org.pe/uploads/archivos/mesaplanesnacionales_irmamora-fitel.pdf (accessed on 05 November 2018).

[12] MTC (2010), FITEL: Telecomunicaciones para áreas rurales de Perú, http://www.cedecap.org.pe/uploads/archivos/mesaplanesnacionales_irmamora-fitel.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2018).

[5] OECD (2016), Multi-dimensional Review of Peru: Volume 2. In-depth Analysis and Recommendations, OECD Development Pathways, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264264670-en.

[1] OECD (2016), OECD Public Governance Reviews: Peru: Integrated Governance for Inclusive Growth, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264265172-en.

[2] OECD (2016), Regulatory Policy in Peru: Assembling the Framework for Regulatory Quality, OECD Reviews of Regulatory Reform, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264260054-en.

[17] OSIPTEL (2018), Reporte Estadístico - Febrero 2018, https://www.osiptel.gob.pe/Archivos/Publicaciones/reporte-estadistico_feb2018/files/assets/basic-html/index.html#1 (accessed on 22 June 2018).

[15] OSIPTEL (2014), El Boom de las Telecomunicaciones - OSIPTEL, https://www.osiptel.gob.pe/Archivos/Publicaciones/boom_telecomunicaciones/files/assets/basic-html/index.html#1/z#noFlash (accessed on 22 June 2018).

[10] OSIPTEL (2014), The Telecommunications Boom, OSIPTEL, https://www.osiptel.gob.pe/Archivos/Publicaciones/boom_telecomunicaciones/boom_telecomunicaciones_osiptel.html#6.

[6] Poder Judicial del Peru (2012), Poder Judicial del Peru, http://www.pj.gob.pe/wps/wcm/connect/CorteSuprema/s_cortes_suprema_home/as_Inicio/ (accessed on 25 June 2018).

[8] Presidencia del Consejo de Ministros (2018), Guidelines for the Regulatory Quality Assessment of Administrative Procedures.

Notes

← 1. Some public sector agencies are exempted from SERVIR’s policies, as defined by Legislative Decree 1023.

← 2. See more: https://www.mef.gob.pe/es/evaluaciones-de-impacto.

← 3. The regulator was operating under the name OSINERG until 2007, when it was extended to cover the mining subsector and was then renamed OSINERGMIN.

← 4. SUNASS was created by the Law Decree No. 25965 of December 19th, 1992; OSIPTEL by the Legislative Decree No. 702 of July 11th, 1991; OSINERGMIN by the Law No. 26734 of December 31st, 1996; and OSITRAN by Law No. 26917 of 23 January 1998.

← 5. Indecopi was created by Executive Order No. 25868 of November 1992. Act 27444 and Legislative Decree No. 1256 serve as the legal basis for their methodology and approach.

← 6. The only exception across all regulated sectors is telecommunications, where competition law powers rest with the economic regulator (OSIPTEL) instead.

← 7. Article No. 110 of Law 29571, Code for the Protection and Defense of the Consumer. A cap for micro- and small-enterprises is set at 10% and 20%, respectively, of sales or gross income received.

← 8. Prior to 1994, CPT provided telephony services to metropolitan Lima and ENTEL offered national d and international services (OSIPTEL, 2014[16]).