This chapter presents findings on the emergent literacy and emergent numeracy of five-year-olds in Estonia. It describes how children’s scores in each of these early learning domains relate to their individual characteristics, family backgrounds, and home learning environments.

Early Learning and Child Well-being in Estonia

Chapter 3. Children’s emergent literacy and emergent numeracy skills in Estonia

Abstract

The importance of early literacy and numeracy development

The cognitive skills developed in early childhood are important for children’s well-being in the present, and foundational to their future success in life. Decades of longitudinal research have shown that early literacy and numeracy outcomes strongly predict later cognitive and educational outcomes (Duncan et al., 2007[1]). Early literacy and numeracy skills are also associated with a range of social-emotional and economic outcomes throughout life. Gaps in cognitive skills between children determined by their individual characteristics, home environments, and early childhood education and care (ECEC) experiences are observable by the time children start school and, once they exist, become increasingly difficult and costly to close. There is ample research evidence to suggest that when societies intervene early, the cognitive skills of children are amenable to improvement.

Gaps in literacy skills require early attention

The consequences of not addressing cognitive skills gaps early are serious. Adequate literacy skills are integral to successful functioning in most societies worldwide; however, approximately 33% of 15-year-old students across OECD countries in the 2018 Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) did not reach a baseline level of proficiency1 in reading, including 11% of 15-year-olds in Estonia (OECD, 2019[2]). Similarly, 20% of adults, on average, across OECD countries have low reading performance,2 including 13% of adults in Estonia (OECD, 2013[3]). These adults have poorer labour-market outcomes and poorer self-reported health than their peers with higher levels of literacy proficiency. They are also more likely to feel that they have little impact on the political process and are less likely to report that they have trust in others (OECD, 2013[3]).

The roots of low adult literacy are found in childhood. As skills beget skills, children who fall behind early in their literacy and language skills are likely to fall further behind over time (Kautz et al., 2014[4]; Rigney, 2010[5]). Measuring the early literacy skills of children can provide important information on where societies should focus attention and resources in order to promote quality and equity in early literacy development and, in turn, in children’s life chances. Assessing emergent literacy skills comprises an integral part of the International Early Learning and Child Well-being Study (IELS).

Early numeracy outcomes are strongly predictive of a range of later outcomes

Although emergent numeracy has been subject to less research attention than emergent literacy, longitudinal research has also identified numeracy skills in early childhood as important for outcomes throughout schooling and into adulthood. Studies have shown that numeracy competence as assessed at school entry is the strongest predictor of later mathematical achievement and strongly predicts achievement in other academic domains (Duncan et al., 2007[1]). Better numeracy skills in childhood are associated with higher socio-economic status in adulthood (Ritchie and Bates, 2013[6]) and with better self-reported health outcomes (OECD, 2016[7]).

On average, 24% of adults in OECD countries do not develop numeracy skills that go beyond the ability to undertake the most basic numerical operations,3 although the corresponding proportion in Estonia is lower, at 14% (OECD, 2013[3]). In most countries, adults with less developed information processing skills, including numeracy skills, are less likely to be employed and, when employed, tend to earn lower wages. While the cost of innumeracy to individuals and societies is high now, it is likely to grow even higher in an increasingly technological and scientific world (Raghubar and Barnes, 2017[8]). Given its established importance for later outcomes, emergent numeracy was selected as an important learning domain to be assessed in IELS.

A comprehensive assessment of early cognitive outcomes should consider a range of skills that are predictive of later competence

Emergent cognitive skills can be broadly categorised as constrained or unconstrained. Constrained skills are those that are finite, such as alphabet knowledge, and these are typically easily assessed. Unconstrained skills are not limited in the same way and include aspects of literacy such as vocabulary knowledge. Unconstrained skills develop over a longer period and draw on constrained skills in their formation (Snow and Matthews, 2016[9]). A comprehensive assessment of emergent literacy skills should include an assessment of both types of skill, which is the approach taken in IELS. While unconstrained emergent literacy skills are generally more challenging to assess, they tend to be more strongly associated with later reading success and were therefore the primary focus of the IELS emergent literacy assessment.

IELS assessed a range of constrained and unconstrained early cognitive skills

IELS assessed three skills deemed fundamental to later literacy competence: the unconstrained skills of listening comprehension and vocabulary knowledge, and the constrained skill of phonological awareness. The assessment of listening comprehension in IELS involved two main components: story-level listening comprehension and sentence-level listening comprehension. The former involved children listening to a story and responding to a series of audio-supported items relating to that story, while the latter involved listening to a series of standalone sentences and responding to a single item about the meaning of each one. Each vocabulary item in IELS required children to identify from a range of very common everyday word options (Tier 1 words4) the synonym of a more complex (Tier 2) word. Phonological awareness assessments required children to identify the first, middle and final phonemes (sounds) of short words. Print knowledge was not assessed in IELS, with the focus instead on the pre-reading literacy and language skills that are predictive of later reading success.5

The general principle of focusing on the assessment of unconstrained skills in IELS was also applied to the assessment of emergent numeracy skills. Emergent numeracy was defined in the study as the ability to recognise numbers and to undertake numerical operations and reasoning in mathematics. The emphasis in the assessment was on simple problem solving and the application of concepts and reasoning in the following content areas: numbers and counting, working with numbers, shape and space, measurement, and pattern. As with literacy, the emergent numeracy assessment was delivered on a tablet and involved children engaging with game-like activities. The emergent numeracy assessment used a mixture of drag-and-drop technology, where children moved items around the screen to construct solutions to problems, and hot-spot technology, where children tapped objects to indicate their preferred option when responding to an item.

This chapter presents the outcomes of the IELS cognitive assessments of children in Estonia. The metric for all learning outcome scales in IELS is the same. There is theoretically no minimum or maximum score in IELS. The results are instead scaled to have approximately normal distributions, with means around 500 and standard deviations around 100. The overall mean of 500 score points represents the average of the means of all participating countries.

In addition to directly assessing emergent literacy and emergent numeracy skills, the study collected indirect information on the children’s emergent literacy and emergent numeracy development through questionnaires administered to the children’s parents and educators, and this information is also presented in this chapter. Where parent and educator reports on aspects of children’s development are compared in tables, figures or text, these analyses are based on the children for whom both parent and educator ratings were available. Parent and educator questionnaires also collected contextual information about the children’s lives at home and at school. This chapter reports how children’s emergent literacy and emergent numeracy skills relate to their individual characteristics, family background characteristics, and home learning environments in Estonia. It also considers the relationships between children’s emergent literacy and emergent numeracy outcomes and their outcomes in other learning domains assessed in IELS. Similarities and differences between the outcomes of IELS in Estonia and those in the other participating countries, the United States and England, are highlighted throughout. The chapter concludes with summary and conclusions.

Emergent literacy and emergent numeracy skills of five-year-olds in Estonia

Five-year-olds in Estonia score at or close to the overall averages for emergent literacy and emergent numeracy in IELS

The mean score of children in Estonia on the IELS direct assessment of emergent literacy was 508 points, which was significantly higher than the mean score in the United States (477 points), but not significantly different from the mean in England (515). The score of children at the 25th percentile of emergent literacy in Estonia was 440 points (414 in the United States and 452 in England) and at the 75th percentile was 576 points (541 in the United States and 584 in England).

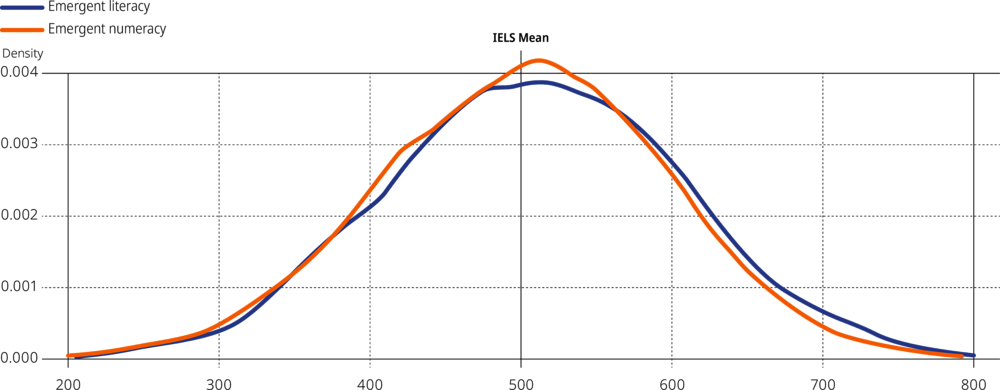

The mean score of five-year-olds in Estonia on the direct assessment of emergent numeracy was 500 points, the same as the overall IELS mean. Estonia’s mean emergent numeracy score was significantly higher than the mean score in the United States (471), significantly lower than the mean score in England (529), and equidistant from both. The score of children at the 25th percentile in emergent numeracy in Estonia was 435 points (409 in the United States, 465 in England), and at the 75th percentile was 567 points (537 in the United States, 599 in England). The distributions of the emergent literacy and emergent numeracy scores in Estonia are shown in Figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1. Distribution of emergent literacy and emergent numeracy scores, Estonia

Note: Distributions produced using the first plausible value only.

Parent and educator evaluations of children’s language development are broadly in line with children’s assessed early literacy skills, although parents tend to rate their children’s development more highly

Both parents and educators are important sources of information on the development of five-year-olds. Parents know most about their child’s developmental pathways and educators are trained professionals who work with young children on a daily basis. In IELS, both parents and educators were asked to indicate whether they deemed the child’s language and numeracy development to be less than average (either much less or somewhat less), average, or more than average (either somewhat more or much more).

Just 4% of children in Estonia had parents who described their receptive language development (defined as the extent to which the child understands, interprets and listens) as being below average, and over two-thirds (68%) had parents who assessed their development as above average. Additionally, over half (57%) of children were rated as having above average receptive language skills by their educators, approximately one third (31%) as having average skills, and just 12% as having below average skills (Table 3.1). Children evaluated by either parents or educators as having below average receptive language development had significantly lower mean emergent literacy scores than those rated as average, while those rated above average had significantly higher mean emergent literacy scores than those rated as average.

Table 3.1. Receptive language development as reported by parents and educators and emergent literacy scores, Estonia

|

|

Parents |

Educators |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

% of children |

Mean score |

% of children |

Mean score |

|

|

Below average |

4 |

431 |

12 |

435 |

|

Average (reference category) |

28 |

479 |

31 |

494 |

|

Above average |

68 |

533 |

57 |

541 |

Note: Mean scores in bold are significantly different from those of children in the “average” category. The table is based on the subsample of children for whom both parent and educator ratings were available.

In terms of expressive language development in Estonia (i.e. the degree to which the child uses language effectively, can communicate ideas, etc.), 8% of five-year-olds had parents who assessed their skills as below average, and 15% had educators who assessed their skills as below average. A majority of children (67%) had parents who rated their child’s expressive language development as above average, while 54% had educators who assessed them as having above average expressive language skills. Children rated as having average expressive language development by their parents or educators had significantly higher mean emergent literacy scores than children rated as below average, and significantly lower mean scores than children rated as above average (Table 3.2).

Table 3.2. Expressive language development as reported by parents and educators and emergent literacy scores, Estonia

|

|

Parents |

Educators |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

% of children |

Mean score |

% of children |

Mean score |

|

|

Less than average |

8 |

440 |

15 |

446 |

|

Average (reference category) |

26 |

478 |

31 |

495 |

|

More than average |

67 |

536 |

54 |

544 |

Note: Mean scores in bold are significantly different from those of children in the “average” category. The table is based on the subsample of children for whom both parent and educator ratings were available.

Most five-year-olds in Estonia have mastered key language skills, according to their parents and educators

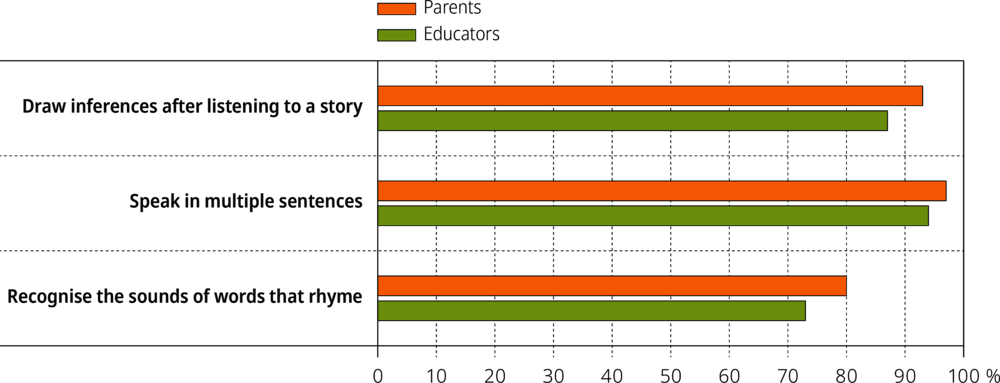

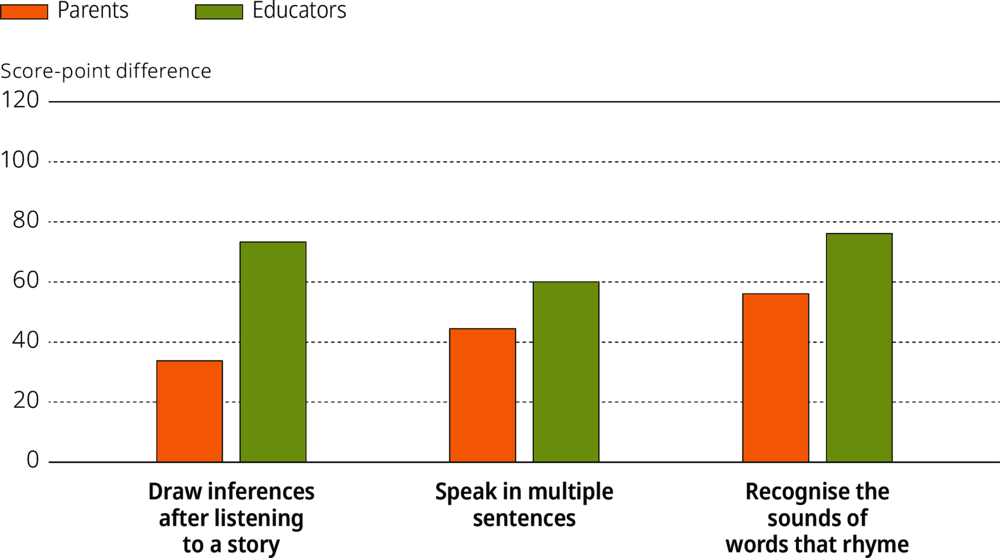

In addition to providing overall ratings of children’s language development, parents and educators were asked to indicate whether children had mastered a number of specific language and literacy-related skills. In Estonia, 93% of children had parents who indicated that their child could draw inferences after listening to a story about how a character felt or about what might happen next. Additionally, 97% of children had parents who indicated that their five-year-old could speak in multiple sentences (at least three) to explain something that had happened to him or her. A lower proportion (80%) of children had parents who indicated that their child could recognise the sounds of words that rhyme. Educators were less likely than parents were to indicate that children had mastered each skill (Figure 3.2), as was also the case in England and the United States. However, the gaps between parent and educator reports were smaller in Estonia than in any other country. In each case, children whose parents indicated that they had not mastered the skill had a significantly lower mean emergent literacy score than other children (Figure 3.3), with gaps ranging from 34 to 76 points, depending on the skill and informant in question.

Figure 3.2. Mastery of key language and literacy-related skills as reported by parents and educators, Estonia

Figure 3.3. Emergent literacy scores by reported mastery of key language and literacy-related skills, Estonia

Similar proportions of children were reported as having below average, average and above average numeracy development by their parents and educators

Children whose numeracy development was rated as average by their parents or educators had significantly higher mean emergent numeracy scores than children whose development was rated as below average, and significantly lower mean scores than children whose development was rated as above average (Table 3.3).

Table 3.3. Numeracy development as reported by parents and educators and emergent numeracy scores, Estonia

|

|

Parents |

Educators |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

% of children |

Mean score |

% of children |

Mean score |

|

|

Less than average |

10 |

421 |

11 |

396 |

|

Average (reference category) |

36 |

483 |

39 |

492 |

|

More than average |

54 |

533 |

49 |

538 |

Note: Mean scores in bold are significantly different from those of children in the “average” category. The table is based on the subsample of children for whom both parent and educator ratings were available.

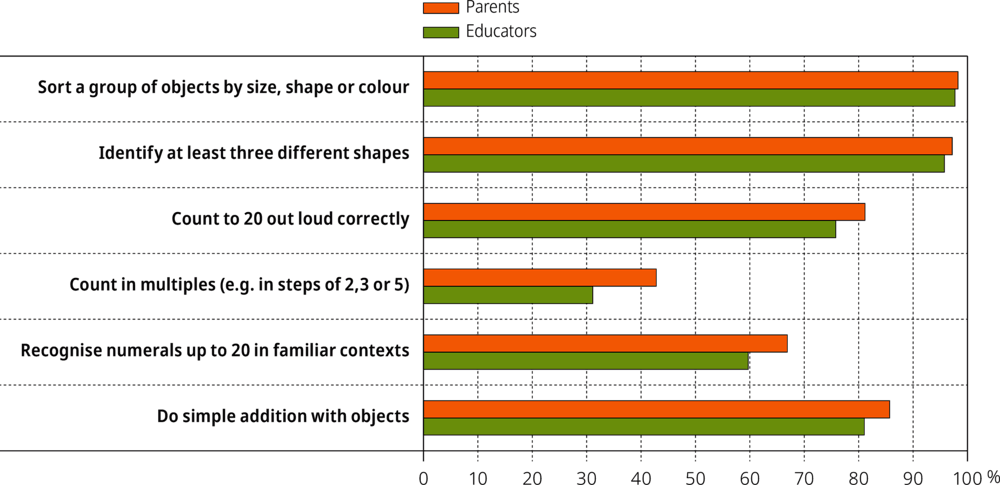

Parents and educators were asked to indicate whether each child had mastered a series of numeracy or mathematics-related skills. In all cases, parents were more likely than educators to indicate that their child had mastered the skill (Figure 3.4). Children were most likely to be reported by their parents and educators as being able to sort a group of objects by size, shape or colour (98% by both parents and educators), and to identify at least three different shapes (97% by parents and 96% by educators). Children were least likely to be reported by their parents and educators as being able to count in multiples (43% and 31%, respectively, the largest gap between parent and educator reports).

Figure 3.4. Mastery of key early mathematics skills as reported by parents and educators, Estonia

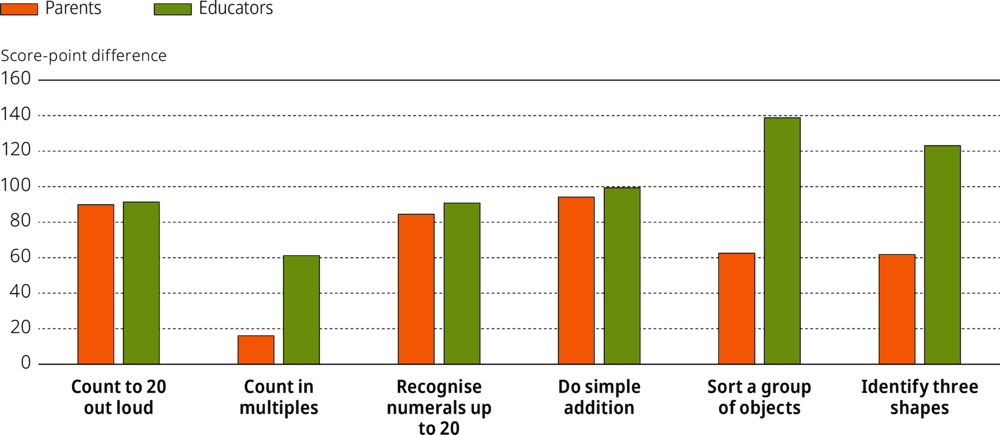

In all cases, children reported as having mastered a particular skill had significantly higher mean emergent numeracy scores than children reported as not having mastered this skill, as was also the case in England and the United States. Significant score-point gaps ranged from 16 points (between children who could and could not count in multiples, according to their parents) to 139 points (between children who could and could not sort a group of objects by size, shape or colour, according to their educators; Figure 3.5). The difference between the mean scores of children who could and could not count in multiples, according to their parents, was not statistically significant.

Figure 3.5. Emergent numeracy scores by reported mastery of key early mathematics skills, Estonia

Individual characteristics and emergent literacy and emergent numeracy skills

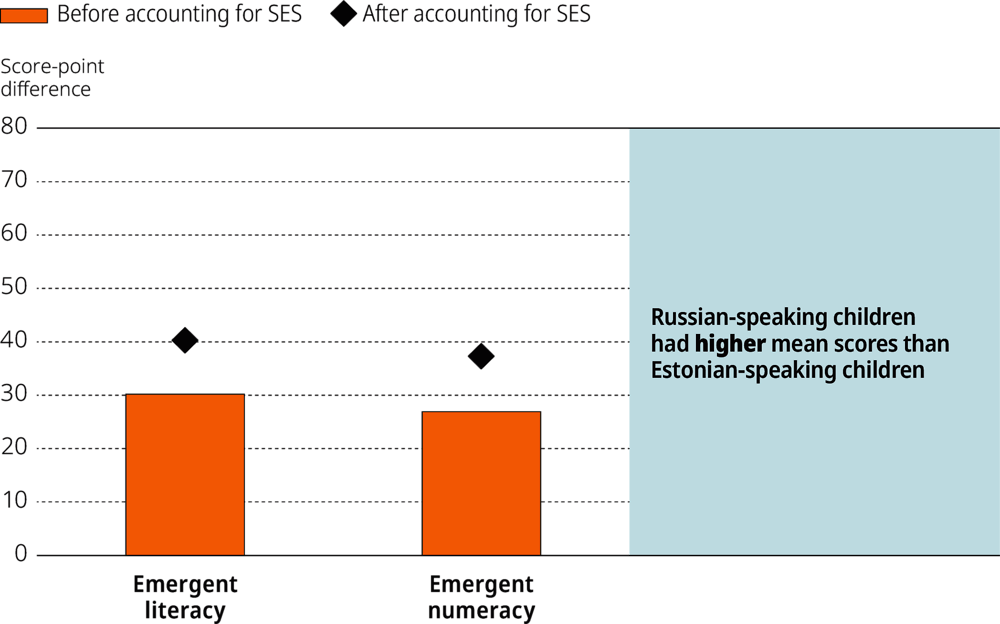

Russian-speaking children have better early literacy and numeracy skills at age five than Estonian-speaking children despite being, on average, of lower socio-economic status

In Estonia, 21% of children took the IELS assessment in Russian. These children had a mean emergent literacy score significantly higher than the mean score for those who took the assessments in Estonian (Figure 3.6), despite Russian-speaking children having significantly lower socio-economic status (SES) scores than Estonian-speaking children. The SES index constructed for use in IELS was based on household income, parent occupation and parental educational attainment.6

Figure 3.6. Emergent literacy and emergent numeracy scores by children’s language, Estonia

Note: All differences are statistically significant. ‘Russian-speaking children’ refers to children who took the assessment in Russian.

The mean emergent numeracy score of Russian-speaking children was also significantly higher than that of Estonian-speaking children and the gap increased after accounting for socio-economic status.

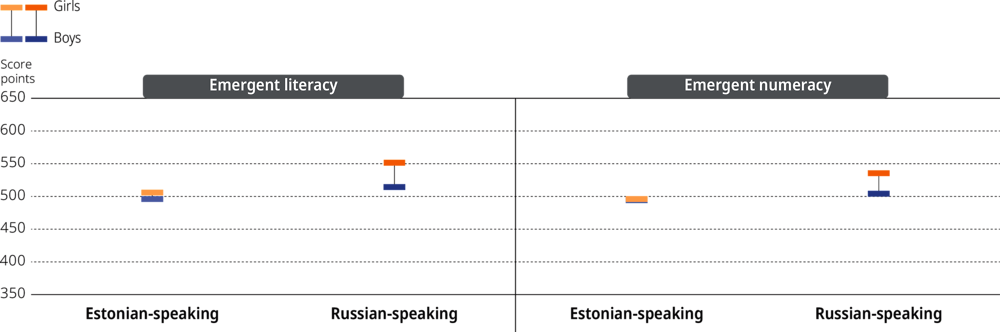

Russian-speaking girls have better early literacy and numeracy outcomes than Russian-speaking boys, but there are no significant gender gaps among Estonian-speaking children

There was a statistically significant gender gap in emergent literacy among Russian-speaking children, with girls outperforming boys by an average of 37 score points. In contrast, there was no significant gender gap in emergent literacy outcomes among Estonian-speaking children. Significant gender differences in emergent literacy (in favour of girls) were found in both England and the United States. In PISA 2018, the gender gap in reading in Estonia was 31 points, in favour of girls, similar to the 30-point gap on average across OECD countries (OECD, 2019[2])

Russian-speaking girls also had a mean emergent numeracy score that was significantly higher than that of Russian-speaking boys, but again, there was no significant gap between the mean emergent numeracy scores of Estonian girls and Estonian boys (Figure 3.7). In PISA 2018, boys in Estonia outperformed girls in mathematics by eight score points, while across OECD countries, boys outperformed girls by five points (OECD, 2019[2])

Figure 3.7. Mean emergent literacy and emergent numeracy scores of Estonian-speaking and Russian-speaking children by gender, Estonia

Note: Significant differences are shown in a darker tone. Russian-speaking children’ refers to children who took the assessment in Russian.

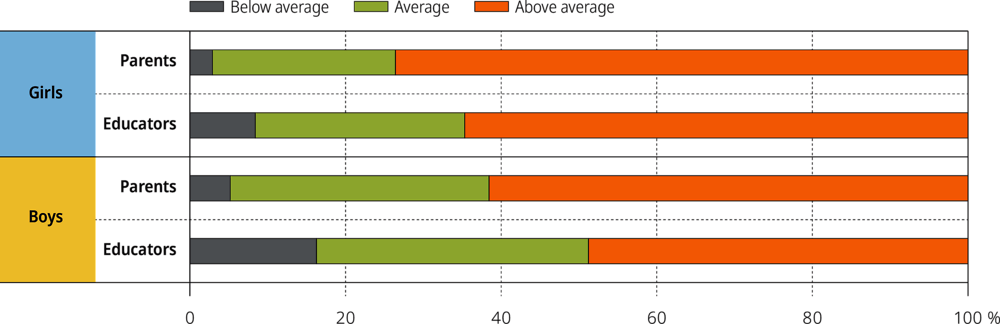

Girls are more likely than boys to have above average receptive and expressive language skills, according to their parents and educators

In line with their better average score on the IELS emergent literacy assessment, girls in Estonia were more likely than boys to have parents and educators who rated their receptive and expressive language development as above average. Girls were also less likely to have their language development rated as below average by their educators (Figure 3.8 and Figure 3.9).

Figure 3.8. Receptive language development as reported by parents and educators by gender, Estonia

Figure 3.9. Expressive language development as reported by parents and educators by gender, Estonia

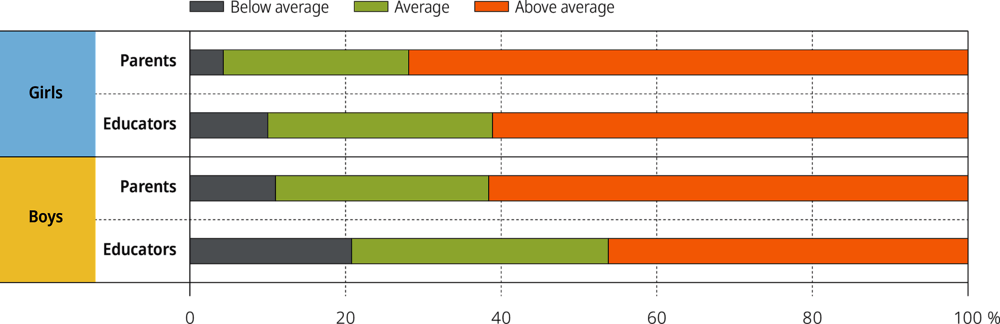

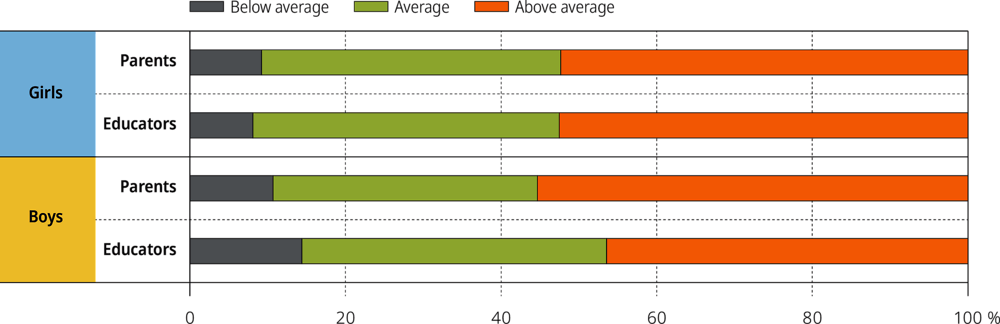

Girls and boys are equally likely to have average numeracy development, according to their parents and educators

Similar proportions of girls and boys were rated as having average numeracy development by their parents and educators, although girls were somewhat more likely to be rated as above average by their educators than boys. (Figure 3.10)

Figure 3.10. Numeracy development as reported by parents and educators by gender, Estonia

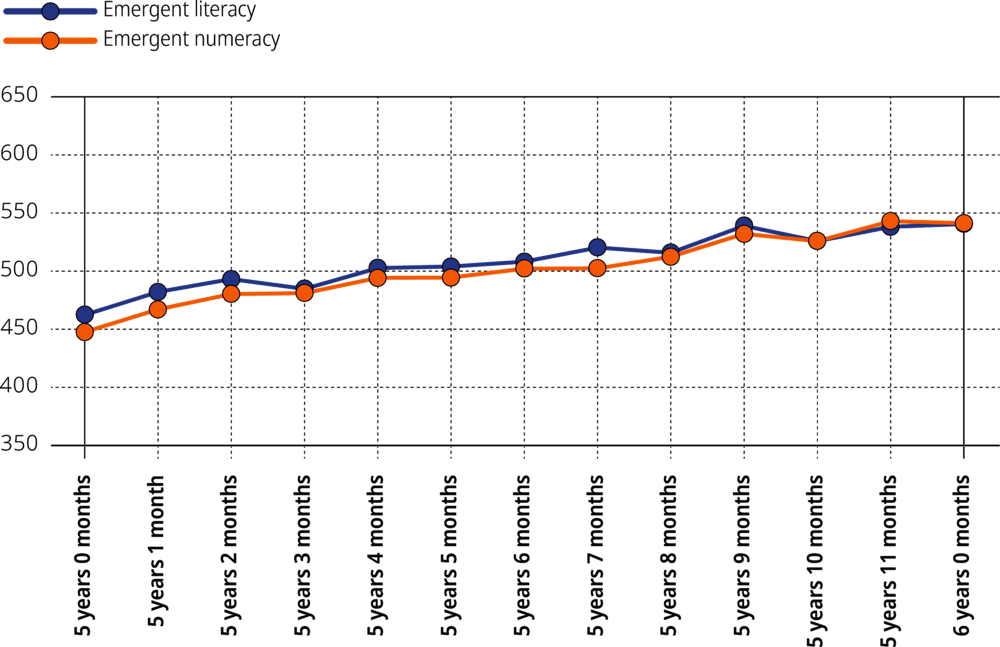

Age is positively related to emergent literacy and emergent numeracy skills in Estonia

For both emergent literacy and emergent numeracy there were significant positive correlations between children’s age in months and their scores on the assessments. In Estonia, the correlation between age and emergent skills was 0.20 for emergent literacy and 0.24 for emergent numeracy. For emergent literacy, the score-point difference between the oldest children (6 years 0 months)7 in the sample and the youngest children in the sample (5 years 0 months) was 78 points. For emergent numeracy, the corresponding gap was 94 points (Figure 3.11).

Figure 3.11. Emergent literacy and emergent numeracy scores by age of child in months, Estonia

The difference in the mean emergent literacy scores of children between the ages of five years one month8 and six years of age was 59 points in Estonia, 87 in England, and 92 in the United States. For emergent numeracy, the difference was 74 points in Estonia, 126 in England, and 110 in the United States.

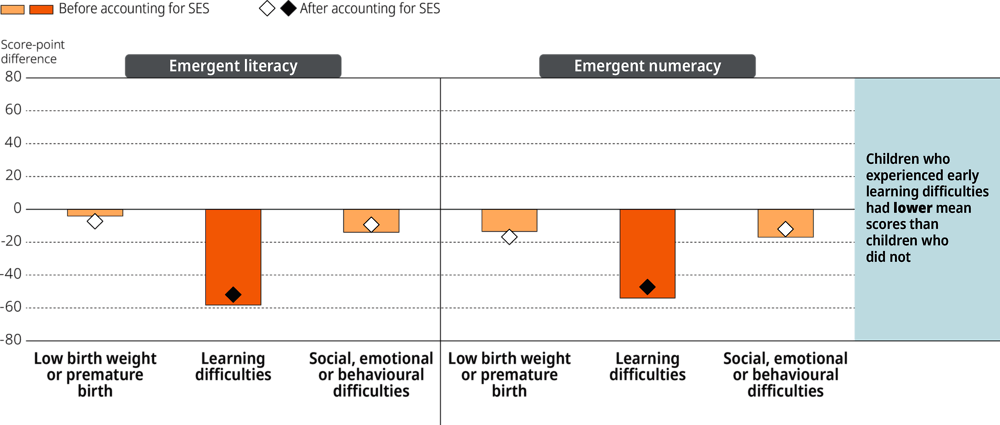

Having had low birth weight or premature birth, learning difficulties, or social, emotional or behavioural difficulties is associated with lower emergent literacy and emergent numeracy scores

Parents were asked to indicate whether their child had ever experienced a number of potential challenges or difficulties. In Estonia, 8% of children were reported by their parents as having had low weight at birth or premature birth (compared to 10% in the United States and 11% in England).9 These children had mean emergent numeracy scores that were significantly lower than those of their peers who did not have low birth weight and were not born prematurely, but there was no significant difference in mean emergent literacy scores. One in ten children (10%) in Estonia had experienced learning difficulties, according to their parents (13% in the United States, 10% in England). These children scored significantly lower in both emergent literacy and emergent numeracy, on average, than other children. Additionally, 10% of five-year-olds in Estonia had social, emotional or behavioural difficulties, according to their parents (12% in the United States, 8% in England). Again, these children had significantly lower mean emergent literacy and emergent numeracy scores than other children.

When each of the difficulties was examined in combination (i.e. examining the effect of one difficulty after accounting for the effects of other early difficulties) and after accounting for socio-economic status, having learning difficulties remained the only significant predictor of both emergent literacy and emergent numeracy scores (Figure 3.12).

Figure 3.12. Relative associations between early difficulties and emergent literacy and emergent numeracy scores, Estonia

There were statistically significant associations between gender and having learning difficulties or having social, emotional or behavioural difficulties in Estonia. Boys were twice as likely as girls to be reported as having learning difficulties (6.5% of girls and 13% of boys), and were also significantly more likely to have had social, emotional or behavioural difficulties (7% of girls and 14% of boys), according to their parents. These gender associations were also present in the United States and England. No significant gender differences were observed in relation to birth weight or premature birth.

There were also statistically significant associations between having experienced each of these challenges or difficulties and socio-economic status. In Estonia, 15% of children in the lowest SES quartile had learning difficulties, according to their parents, compared to 7% of children in the top SES quartile. Additionally, 15% of children in the lowest SES quartile in Estonia had social, emotional or behavioural difficulties, according to their parents, compared to 8% of children in the top SES quartile. There was no significant association between low birth weight/premature birth and socio-economic status in Estonia (such an association was present in the United States). Russian-speaking and Estonian-speaking children were equally likely to have experienced low birth weight or premature birth, learning difficulties, and social, emotional or behavioural difficulties.

Overall, 17% of children in Estonia had experienced one of the three challenges, according to their parents, 4% of children experienced two, and fewer than 1% experienced all three. In other words, 78% of five-year-olds in Estonia had experienced none of the challenges, which is similar to the percentage in England and the United States.

Home and family characteristics and emergent literacy and emergent numeracy skills

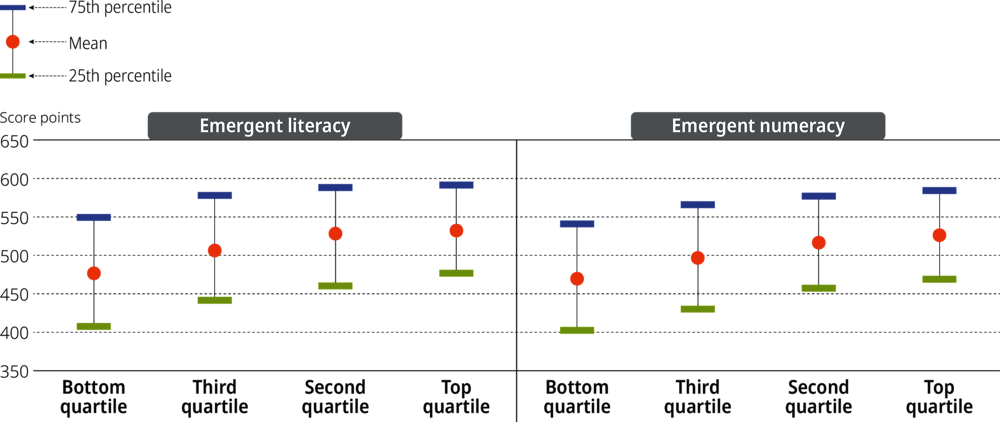

Socio-economic status is less strongly associated with emergent literacy and emergent numeracy scores in Estonia than in the other two countries that participated in the study

Socio-economic status was significantly positively correlated with emergent literacy (r = 0.20) and emergent numeracy (r = 0.23) outcomes in Estonia, but correlations were weaker than in England (r = 0.37 for emergent literacy and 0.34 for emergent numeracy) and the United States (r = 0.36 and 0.45, respectively).

The gap between the mean emergent literacy scores of children in the top and bottom SES quartiles in Estonia was 56 points, which is smaller than the corresponding gaps in England (93 points) and the United States (84 points). The gap between the mean emergent numeracy scores of those in the top and bottom SES quartiles in Estonia was 56 points, which is around half the size of the corresponding gap in the United States (110 points), and smaller than the 86-point gap in England.

Figure 3.13. Emergent literacy and emergent numeracy scores by socio-economic quartile, Estonia

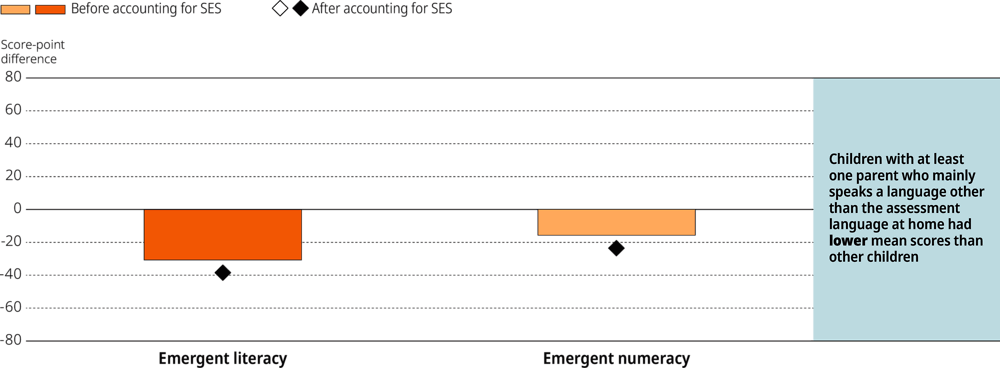

Children with at least one parent who mainly speaks a language other than the assessment language have lower emergent literacy scores

At the time of the assessment in Estonia, 6% of five-year-olds lived in homes where at least one parent mostly spoke a language other than the language through which they took the assessment (either Russian or Estonian). These children had significantly lower mean emergent literacy scores before and after accounting for socio-economic status (Figure 3.14). There was no significant difference between the mean emergent numeracy scores of children with at least one parent who spoke mainly a language other than the IELS assessment language and children whose parents mainly spoke the assessment language, after accounting for socio-economic status.

Figure 3.14. Emergent literacy and emergent numeracy scores by home language, Estonia

Family structure is not related to children’s emergent literacy and emergent numeracy skills in Estonia

In Estonia, 12% of five-year-olds lived in one-parent households. These children had similar levels of emergent literacy and emergent numeracy as children who lived in two-parent households. One in five (20%) five-year-olds in Estonia had no siblings, half (50%) had one sibling, one in five had two siblings (21%) and the remaining 9% had more than two siblings. The mean emergent literacy and emergent numeracy scores of children with one sibling did not differ significantly from those of children with no siblings or children with more siblings.

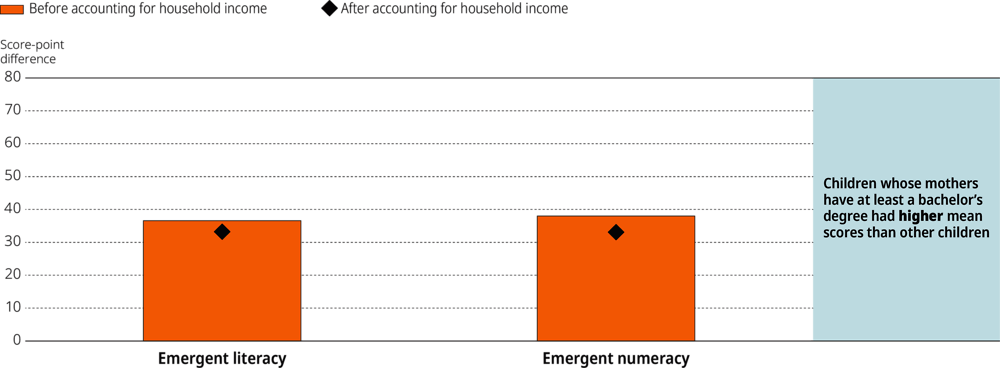

Children whose mothers have higher educational attainment have better early literacy and numeracy skills

In Estonia, as in the two other participating countries, mothers’ educational attainment was significantly positively related to children’s early literacy and numeracy outcomes (Table 3.4). In Estonia, 53% of children had mothers who had completed a bachelor’s degree or higher (compared with 39% in the United States and 40% in England). These children had higher mean emergent literacy and emergent numeracy scores than children whose mothers had completed less formal education, even after accounting for household income (Figure 3.15).

Table 3.4. Maternal educational attainment and emergent literacy and emergent numeracy scores, Estonia

|

|

% of children |

Literacy |

Numeracy |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Lower secondary |

8 |

474 |

467 |

|

Upper secondary |

19 |

495 |

484 |

|

Post-secondary, non-tertiary |

8 |

496 |

494 |

|

Short-cycle tertiary |

12 |

509 |

497 |

|

Bachelor’s degree |

32 |

527 |

516 |

|

Masters degree, doctorate or equivalent |

20 |

533 |

530 |

Note: There were too few children whose mothers’ highest level of educational attainment was primary school to present their mean scores in this report.

Figure 3.15. Emergent literacy and emergent numeracy by mother’s educational attainment, Estonia

Home learning environment and emergent literacy and emergent numeracy skills

The home is the first major context in which children learn, develop and grow. A home environment that is supportive of early learning, in terms of both stimulating resources and interactions, is an important determinant of children’s early cognitive outcomes. Collecting information on children’s home learning environments was an important focus of IELS.

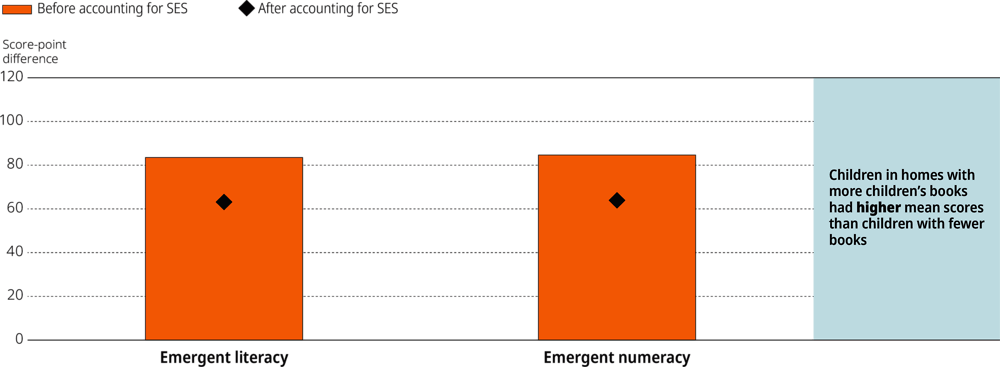

Children from homes with a greater number of children’s books have higher average emergent literacy and emergent numeracy scores

Children in homes with more children’s books had, on average, higher emergent literacy and emergent numeracy scores than children with fewer books (Table 3.5). Children in Estonia were less likely to come from homes with more than 100 books (10%) than in the United States (26%) or England (29%), but roughly equally likely to be in homes with 10 books or fewer (13%) as the United States (12%) and England (9%). The gap in emergent literacy between children with 10 books or fewer and those with more than 100 children’s books was 84 points (64 after accounting for socio-economic status). The corresponding gap for numeracy was 85 points (64 after accounting for socio-economic status; Figure 3.16).

Table 3.5. Number of books in the home and emergent literacy and emergent numeracy scores, Estonia

|

|

% of children |

Literacy |

Numeracy |

|---|---|---|---|

|

0-10 |

13 |

465 |

458 |

|

11 to 25 |

23 |

503 |

488 |

|

26 to 50 |

32 |

512 |

503 |

|

51 to 100 |

21 |

535 |

531 |

|

More than 100 |

10 |

548 |

543 |

Figure 3.16. Emergent literacy and emergent numeracy scores by number of children’s books in the home, Estonia

Children whose parents read books to them more frequently have better emergent literacy skills than those whose parents read to them less frequently

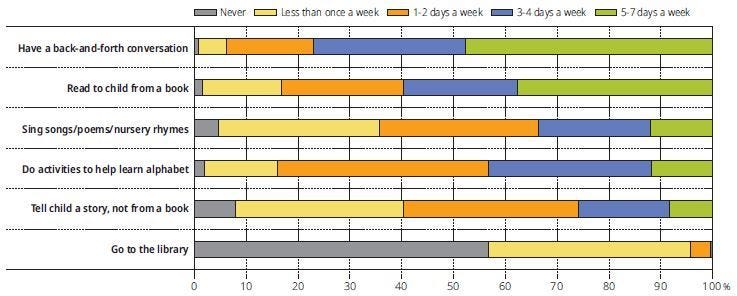

Figure 3.17 shows the percentage of children whose parents engaged in a range of language and literacy-related activities at home with varying frequency. Having a back-and-forth conversation with the child about how they feel and why was the activity most likely to be engaged in on at least five days each week (48% of children had parents who did this), followed by reading to the child from a book (38% of children). There were no significant associations between a child’s gender and the frequency with which their parents engaged in any of these activities with them at home. There were, however, significant associations between socio-economic status and the frequency with which the child was read to from a book, had back-and-forth conversations with the parent, and was sang to by a parent. For example, in Estonia, 18% of children in the bottom SES quartile were read to from a book on at least five days a week, compared to 57% of children in the top SES quartile. Similarly, 38% of children in the bottom SES quartile had back-and-forth conversations with their parents five to seven days a week, compared to 55% of children in the top SES quartile. Finally, 10% of children in the bottom SES quartile had parents who sang songs or nursery rhymes to them five to seven days a week, compared to 15% of children in the top SES quartile. Children from Russian-speaking families were somewhat more likely to be told stories (not from a book) on multiple days a week than children from Estonian-speaking families, but were somewhat less likely to have back-and-forth conversations with their parents on multiple days a week about how they feel and why.

Figure 3.17. Frequency of engagement in literacy-related activities at home, Estonia

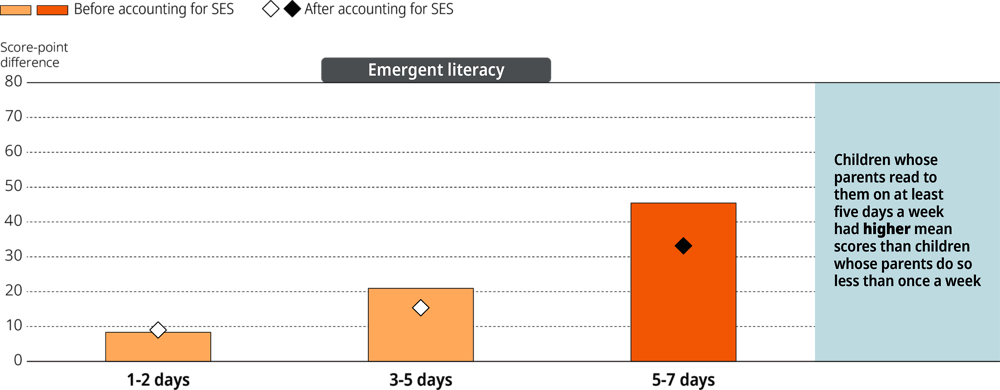

Children whose parents read to them from a book on at least five days a week had a significantly higher mean emergent literacy score than children whose parents did so less than once a week, holding socio-economic status constant (Figure 3.18). This was the only activity that was significantly associated with children’s emergent literacy scores in IELS after accounting for socio-economic status.

Figure 3.18. Emergent literacy scores by how often a child is read to from a book at home, Estonia

Most children have parents who engage in numeracy-related activities with them at home at least once a week

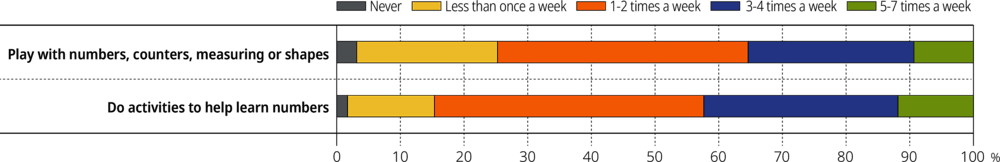

Figure 3.19 shows the percentages of children whose parents engaged in numeracy-related activities at home with them with varying frequency. In Estonia, 25% of children had parents who said they played with numbers, counters, measuring or shapes less often than one day a week with their child, and 15% had parents who said they engaged in activities designed to help them learn numbers less than once a week. These percentages are higher than in England or the United States.

Figure 3.19. Frequency of engagement in numeracy-related activities at home, Estonia

There was a statistically significant association between a child’s gender and the frequency with which parents engaged in activities with the child involving numbers, counters, measuring or shapes, with boys somewhat more likely to have parents engage in these activities with them more frequently. There were no significant associations between frequency of engagement with these activities and socio-economic status, or with being from an Estonian- or Russian-speaking background.

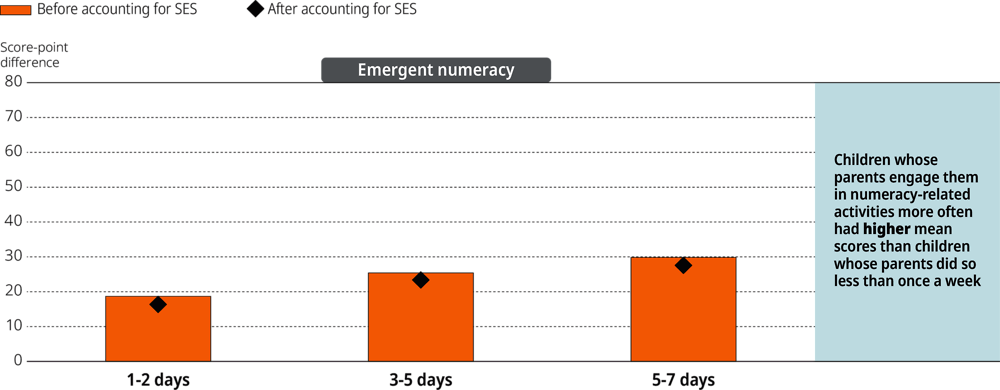

Children whose parents engaged with them in activities at home involving numbers, counters, measuring or shapes less often than once a week had a significantly lower mean emergent numeracy score than children whose parents did so more frequently, even after accounting for socio-economic status (Figure 3.20).

Figure 3.20. Emergent numeracy scores by frequency of numeracy-related activities at home, Estonia

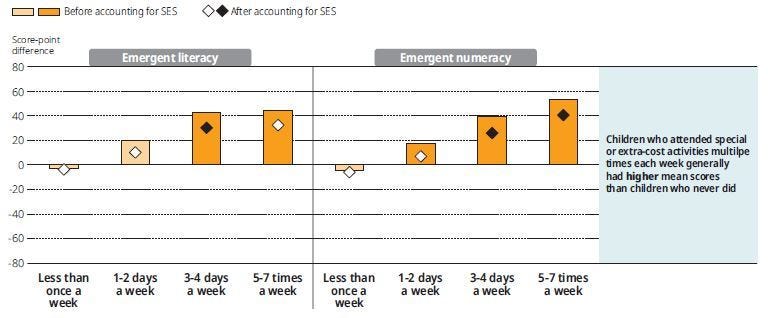

Attendance of special or extra-cost activities outside of the home is associated with higher emergent literacy and emergent numeracy scores

Parents were also asked how often their five-year-old child attended a special or extra-cost activity outside of the home (such as a sports activity, dance, scouts, swimming lessons, language lessons) In Estonia, 22% of five-year-olds never attended a special or extra-cost activity, 14% did so less than once a week, 40% on one or two days a week, 20% on three to four days a week, and 5% on five or more days a week. Generally, children who attended these activities had significantly higher mean scores than children who never did, even after accounting for socio-economic status (Figure 3.21).

Figure 3.21. Emergent literacy and emergent numeracy by frequency of participation in special or paid activities outside the home, Estonia

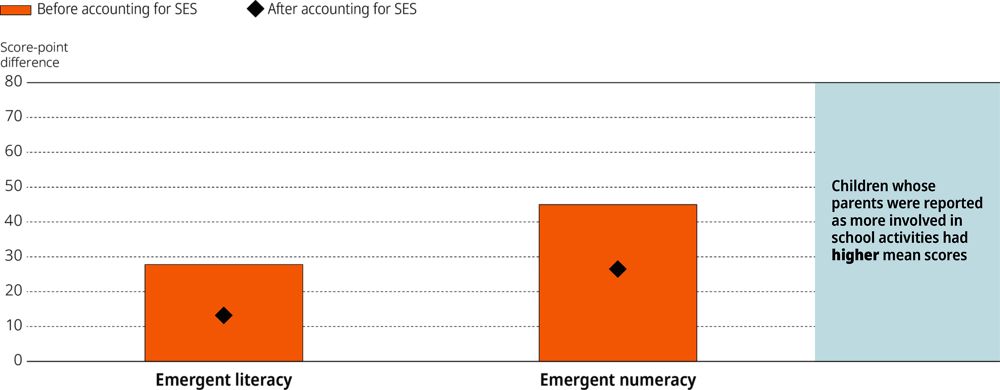

Children whose parents are more strongly involved in preschool activities have higher scores, on average, than other children

In Estonia, 80% of five-year-olds had parents who were either moderately or strongly involved in their preschool institution (according to educators), a higher percentage than in England (69%) or the United States (65%). These children had a mean emergent literacy score that was significantly higher than the 20% of children whose educators indicated that their parents were not involved or were only slightly involved in the preschool institution, after accounting for socio-economic status. Similarly, children whose parents were more involved had a significantly higher mean emergent numeracy score than those whose parents were less involved, even after accounting for socio-economic status (Figure 3.22).

Figure 3.22. Emergent literacy and emergent numeracy scores by parental involvement in preschool activities, Estonia

The mean emergent literacy and emergent numeracy scores of children who never used digital devices are not significantly different from those of children who did use them, regardless of frequency of use

In Estonia, 39% of five-year-olds used a desktop or laptop computer, tablet device or smartphone every day, similar to the proportion in England and lower than the 49% in the United States. A further 39% used at least one of these devices at least once a week; 13% at least once a month, but not weekly; and 9% never or hardly used such devices. In Estonia, 4% used a digital device for educational activities five to seven days a week, 8% did so three to four days a week, 20% did so one to two days a week, 36% did so less than once a week, and 31% never did. The mean emergent literacy and emergent numeracy scores of children who never used devices were not significantly different from those of children who did, regardless of frequency (before or after accounting for socio-economic status). However, children who used digital devices every day had a significantly lower mean emergent literacy score than those children who used them at least once a week but not every day, after accounting for socio-economic status.

Assessing the combined effects of child and family characteristics on emergent literacy and emergent numeracy scores

Analyses in this chapter have so far looked at relationships between emergent literacy and emergent numeracy outcomes and a series of background characteristics individually, or often after accounting for the effects of a third variable (such as socio-economic status). This section examines the effects of these characteristics in combination. In order to do this, variables that were significantly related to emergent literacy and emergent numeracy outcomes when examined individually were used in two regression models (one for emergent literacy and one for emergent numeracy) to assess how well they explained variation in the outcomes. It should be noted that no causal attribution can be made on the basis of these analyses.

Variables that were not significant in the models were removed one at a time10 until all remaining variables were significantly related to the outcome.

A range of individual characteristics and contextual factors significantly predict the emergent literacy scores of children in Estonia when examined in combination

Eight variables were significant predictors in the final model of emergent literacy in Estonia (Table 3.6). All else being equal, boys in Estonia had an emergent literacy scores that was 14 points lower than that of girls. Each month of increasing age was associated with an increase in emergent literacy scores of 5.4 points. Children with learning difficulties scored almost half a standard deviation lower (45 points) than other children, holding all other variables in the model constant. All else being equal, children from Estonian-speaking ECEC centres had a mean score that was 32 points lower than children from Russian-speaking centres. Children with at least one parent who spoke a language other than the language of the ECEC centre at home scored an average of 32 points lower than other children, all else being equal. Children whose parents read books to them five to seven times a week had a score that was 23 points higher than children whose parents did so less than once a week, holding all other variables in the model constant. A one standard deviation increase in socio-economic status was associated with an increase of 15 score points in emergent literacy. Children with more than 100 children’s books at home had an advantage of 54 points, on average, over children with 10 children’s books or fewer at home, all else being equal. The final model explains 15% of the variance in emergent literacy outcomes in Estonia.

Table 3.6. Results of the multiple regression model of emergent literacy, Estonia

|

Variable |

B |

SE |

p |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Child is a boy |

-14.3 |

7.06 |

.043 |

|

Age (months) |

5.4 |

0.85 |

.000 |

|

Russian speaking |

31.5 |

10.47 |

.003 |

|

Home language different to assessment language |

-31.9 |

12.44 |

.010 |

|

Learning difficulties |

-45.0 |

13.33 |

.001 |

|

Socio-economic status |

14.8 |

3.40 |

.000 |

|

Books in the home (reference category: 10 or fewer) |

|

|

|

|

11 to 25 |

26.2 |

9.49 |

.006 |

|

26 to 50 |

27.3 |

10.19 |

.007 |

|

51 to 100 |

44.9 |

10.96 |

.000 |

|

More than 100 |

54.4 |

14.09 |

.000 |

|

Frequency of being read to from a book (reference category: less than once a week/never) |

|

|

|

|

1-2 days a week |

7.3 |

9.88 |

.463 |

|

3-4 days a week |

4.6 |

9.97 |

.644 |

|

5-7 days a week |

22.5 |

8.64 |

.009 |

|

Intercept |

461.7 |

19.70 |

|

Note: p-values in bold indicate statistical significance. B = regression coefficients. SE = Standard Error.

The intercept is the estimated score of a child in the reference category of each categorical variable, aged 5 years 0 months, and with a mean value for socio-economic status.

A range of individual characteristics and contextual factors significantly predict the emergent numeracy scores of children in Estonia when examined in combination

Seven explanatory variables were significant in the final model of emergent numeracy (Table 3.7). Each month of increasing age was associated with an average increase of 6 points in emergent numeracy. All else being equal, children from Russian-speaking families had a mean emergent numeracy score that was 31 points higher than children from Estonian-speaking families. The gap between the scores of children with 10 or fewer children’s books and those with more than 100 children’s books at home was equivalent to 59 points on the emergent numeracy scale, all else being equal. A one standard deviation increase in socio-economic status was associated with an increase in the emergent numeracy score of 15 points. The frequency with which parents engaged in activities at home with the child involving numbers, counters, shapes or measuring was also a significant predictor of children’s early numeracy outcomes. Children whose parents did so most frequently had a mean emergent numeracy score that was 30 points higher than those whose parents did so less frequently, after accounting for the effects of the other variables in the model. Finally, children whose parents were described as moderately or strongly involved in activities at the child’s ECEC centre had a mean numeracy score that was 16 points higher than children whose parents were not involved or only slightly involved. The final model explains 19% of the variance in children’s emergent numeracy outcomes in Estonia.

Table 3.7. Results of the multiple regression model of emergent numeracy, Estonia

|

Variable |

B |

SE |

p |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Age (months) |

6.4 |

.84 |

.000 |

|

Russian-speaking |

31.1 |

11.27 |

.006 |

|

Socio-economic status |

15.4 |

3.89 |

.000 |

|

Learning difficulties |

-49.3 |

10.35 |

.000 |

|

Books in the home (reference category: 10 or fewer) |

|

|

|

|

11 to 25 |

18.2 |

8.89 |

.040 |

|

26 to 50 |

28.2 |

8.29 |

.001 |

|

51 to 100 |

51.4 |

9.24 |

.000 |

|

More than 100 |

59.0 |

11.70 |

.000 |

|

Frequency of activities at home with numbers, counters, shapes, measuring (reference category: less than once a week/never) |

|

|

|

|

1-2 days a week |

18.8 |

6.29 |

.003 |

|

3-4 days a week |

25.7 |

7.62 |

.001 |

|

5-7 days a week |

29.6 |

9.55 |

.002 |

|

Parent moderately/strongly involved in ECEC |

15.8 |

6.28 |

.012 |

|

Intercept |

405.5 |

10.90 |

|

Note: p-values in bold indicate statistical significance. B = regression coefficient. SE = standard error.

The intercept is the estimated score of a child in the reference category of each categorical variable, aged 5 years 0 months, and with a mean value for socio-economic status.

Relationship between early literacy and numeracy scores and outcomes in other learning domains

Children’s early language and numeracy skills are developing at the same time as children are developing a host of other skills, including self-regulation and a range of social-emotional competencies. Development in each of these areas is theorised to be mutually reinforcing. Young children with better language ability, for example, may be better able to engage successfully with their peers in interactions that support their prosocial development. Better prosocial skills may lead to further opportunities to interact with others in ways that support children’s vocabulary development and oral comprehension. As IELS assessed a broad range of children’s early learning outcomes, it enables relationships between these learning domains at the age of five to be examined.

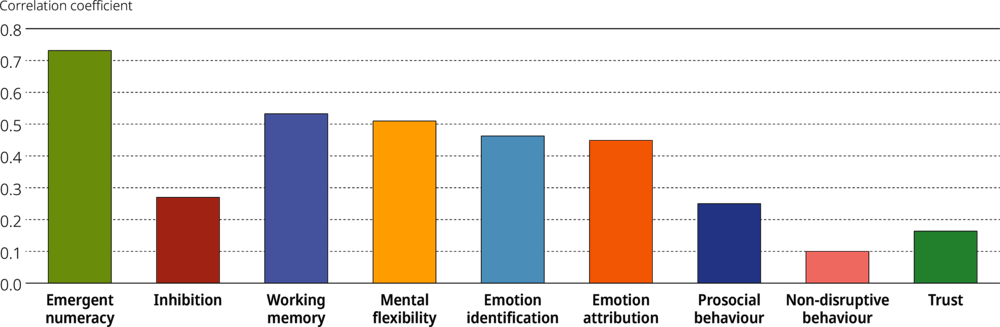

Emergent literacy and emergent numeracy skills are strongly related to each other, as well as positively related to self-regulation skills and social-emotional skills

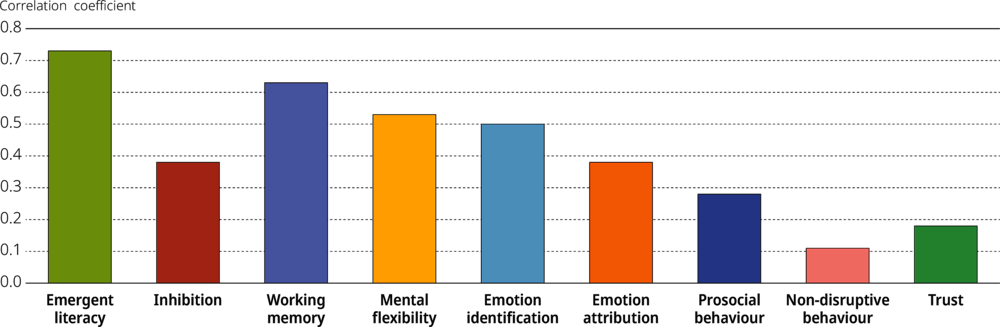

Figure 3.23 shows the correlations between emergent literacy scores and scores in other learning domains assessed in IELS in Estonia. Emergent literacy and emergent numeracy were strongly positively correlated (r = .73). Moderate to strong correlations were also observed between emergent literacy and the self-regulation skills of working memory and mental flexibility. Correlations between emergent literacy and most social-emotional skills were weaker, although still statistically significant and positive.

Emergent numeracy scores correlated most strongly with working memory, mental flexibility and emotion identification. Correlations between emergent numeracy and educator assessments of prosocial behaviour, non-disruptive behaviour and trust were weaker (Figure 3.24).

Figure 3.23. Correlations between emergent literacy scores and other learning domains, Estonia

Figure 3.24. Correlations between emergent numeracy scores and other learning domains, Estonia

Summary and conclusions

Five-year-old children in Estonia score at or close to the overall averages for emergent literacy and emergent numeracy in IELS

Overall, children in Estonia had mean emergent literacy and emergent numeracy skills that were close to the overall IELS averages. In emergent literacy, five-year-olds in Estonia had a mean score that was similar to the mean of children in England and significantly higher than the mean of children in the United States. In emergent numeracy, the mean score of children in Estonia was significantly higher than that of children in the United States, and significantly lower than that of children in England.

Russian-speaking children, especially girls, have better early literacy and numeracy outcomes than Estonian-speaking children

Russian-speaking children in Estonia had significantly higher mean scores than Estonian-speaking children in both emergent literacy and emergent numeracy, despite being of lower socio-economic status, on average.

In Estonia there was an overall gender gap in favour of girls in emergent literacy, but no equivalent gap for emergent numeracy. This is in line with the patterns in England and the United States. Looking at children from Estonian and Russian language backgrounds separately, however, revealed that the gap was only significant among Russian-speaking children: Estonian-speaking boys and girls had similar emergent literacy outcomes. While there was no significant difference in the mean emergent numeracy scores of Estonian-speaking boys and girls, Russian-speaking girls had a significantly higher mean emergent numeracy score than Russian-speaking boys.

Children who have experienced difficulties before the age of five have lower literacy and numeracy skills at age five

Children with learning difficulties and social, emotional or behavioural difficulties had significantly lower mean literacy and numeracy scores than children who did not. However, when all difficulties were examined in combination, only learning difficulties remained significantly associated with lower emergent literacy and emergent numeracy scores. Roughly similar proportions of children in Estonia were identified by their parents as having had low birth weight or premature birth, learning difficulties, and social, emotional or behavioural difficulties as children in England and the United States. As in those other countries, boys were significantly more likely to have learning difficulties and social, emotional or behavioural difficulties than girls. Children in the bottom SES quartile were also significantly more likely to experience these challenges, but there was no significant association with whether the child was Estonian-speaking or Russian-speaking.

Relationships between early literacy and numeracy outcomes and socio-economic background are weaker in Estonia than in either England or the United States

Score-point gaps between children in the top and bottom SES quartiles in Estonia were considerably smaller than those in England and the United States. Children with a home language other than the assessment language had similar emergent numeracy scores to other children, but had lower emergent literacy scores.

A higher proportion of children in Estonia had mothers with a bachelor’s degree or higher than in either England or the United States. Children whose mothers had obtained degrees had better emergent literacy and emergent numeracy outcomes than other children, even after accounting for household income.

A child’s home learning environment is related to their emergent literacy and emergent numeracy scores

The frequency with which children were read to by their parents was significantly related to their emergent literacy skills, even after accounting for SES. Children from low-SES backgrounds were less likely to have parents who read to them frequently, sang songs to them frequently and had back-and-forth conversations with them frequently. Children who attended special, extra-cost activities (such as sport, dance lessons, scouts) more frequently had higher mean scores in emergent literacy and emergent numeracy than those who never did, after accounting for socio-economic status.

In Estonia, a higher proportion of parents was described as being strongly or moderately involved in their children’s education than in either England or the United States. Children whose parents were more involved had higher mean emergent literacy and emergent numeracy scores than children whose parents were less involved, even after accounting for socio-economic status.

Children who never used digital devices at home did not differ significantly in their mean emergent literacy and emergent numeracy scores from children who did so, regardless of the frequency with which they were used. However, children who used digital devices every day had a significantly lower mean literacy score than those children who used them at least once a week but not every day, after accounting for socio-economic status.

A range of individual characteristics and contextual factors predict children’s emergent literacy and emergent numeracy outcomes in Estonia when examined in combination

There were several factors that when analysed in combination were found to be significant predictors of five year olds’ emergent literacy scores in Estonia. These were: gender, whether the child is Estonian-speaking or Russian speaking, having at least one parent at home who speaks a language other than the assessment language, learning difficulties, socio-economic status, age, number of children’s books at home, and frequency of being read to from a book.

There were also several factors that when analysed in combination were found to be significant predictors of five year olds’ emergent numeracy scores in Estonia. These were: whether the child is Estonian-speaking or Russian speaking, socio-economic status, age, number of children’s books at home, frequency of activities at home involving numbers, counters, shapes or measuring, learning difficulties, and level of parental involvement in activities at the ECEC centre.

Whether the child is Estonian-speaking or Russian-speaking, the child’s age, socio-economic status, learning difficulties, and number of children’s books at home were significant predictors in the final models of both emergent literacy and emergent numeracy. Having a language other than the assessment language at home, gender, and the frequency of being read to from a book were significant only in the emergent literacy model, while level of parental involvement at the ECEC centre and the frequency of engaging in activities at home involving numbers, counters, shapes or measuring were only significant in the model of emergent numeracy.

Early learning outcomes in Estonia are interrelated

Five-year-olds’ emergent literacy and emergent numeracy scores in Estonia were also positively related to their social-emotional scores and their self-regulation scores, in line with previous research that suggests that these skills are mutually reinforcing. The scores in these other learning domains of five-year-olds in Estonia are described in the following two chapters.

References

[10] Beck, I., M. McKeown and L. Kucan (2013), Bringing words to life : robust vocabulary instruction, The Guilford Press.

[1] Duncan, G. et al. (2007), “School Readiness and Later Achievement”, Psychological Association, Vol. 43/6, pp. 1428-1446, http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/[0012-1649.43.6.1428].supp.

[4] Kautz, T. et al. (2014), “Fostering and measuring skills: Improving cognitive and non-cognitive skills to promote lifetime success”, NBER Working Paper Series, No. 20749, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, http://dx.doi.org/10.3386/w20749.

[2] OECD (2019), PISA 2018 Results (Volume I): What Students Know and Can Do, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5f07c754-en.

[7] OECD (2016), Skills Matter: Further Results from the Survey of Adult Skills, OECD Skills Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264258051-en.

[3] OECD (2013), OECD Skills Outlook 2013: First Results from the Survey of Adult Skills, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264204256-en.

[8] Raghubar, K. and M. Barnes (2017), “Early numeracy skills in preschool-aged children: A review of neurocognitive findings and implications for assessment and intervention”, Clinical Neuropsychology, Vol. 31/2, pp. 329-351, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2016.1259387.

[5] Rigney, D. (2010), The Matthew Effect: How Advantage Begets Further Advantage, Columbia University Press.

[6] Ritchie, S. and T. Bates (2013), “Enduring links from childhood mathematics and reading achievement to adult socioeconomic status”, Psychological Science, Vol. 24/7, pp. 1301-1308, http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0956797612466268.

[9] Snow, C. and T. Matthews (2016), Reading and Language in the Early Grades, http://www.futureofchildren.org (accessed on 5 December 2019).

Notes

← 1. Scoring at or below proficiency level 1 in the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) reading.

← 2. Scoring at or below proficiency level 1 in the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) reading.

← 3. Scoring at or below proficiency level 1 in PIAAC numeracy.

← 4. Beck, McKeown and Kucan (2013[10]) propose a three-tier model of vocabulary development, where Tier 1 words are common words used in everyday speech (e.g. table, blue), Tier 2 words are high-frequency words that occur across contexts and are more common in written than spoken language (e.g. compare, coincidence). Tier 3 words are low-frequency words used in domain-specific contexts (e.g. thesis, ecosystem).

← 5. For more information, see the IELS assessment framework (OECD, 2020).

← 6. Where educational attainment information was available for two parents, the higher of the two was used.

← 7. While small numbers of children in the sample were aged 4 years 11 months or 6 years 1 month at the time of the assessment, there were too few to meet criteria for reporting and so their mean scores are not considered in this analysis.

← 8. There were too few children aged 5 years 0 months in the United States to reliably estimate their mean scores. Therefore, when comparing the size of score-point differences between older and younger children across all three participating countries, 5 years 1 month is the youngest age for which these comparisons can reliably be made.

← 9. A birth weight lower than 2.5 kg was defined as low.

← 10. In order of descending p-value.