This chapter presents findings on the self-regulation outcomes of five-year-olds in Estonia. It describes how children’s scores in inhibition, mental flexibility and working memory relate to their individual characteristics, family backgrounds and home learning environments.

Early Learning and Child Well-being in Estonia

Chapter 4. Children’s self-regulation skills in Estonia

Abstract

The importance of self-regulation development

Self-regulation describes the mental processes that allow individuals to focus attention, remember instructions and handle multiple tasks successfully. These skills allow the brain to filter out distractions, prioritise tasks and control impulses. The ability to regulate and manage reactions and impulses is essential for personal and professional success (Diamond, 2013[1]; Eisenberg, Spinrad and Eggum, 2010[2]; McClelland et al., 2015[3]).

The brain functions that make up self-regulation include the capacity to use inhibition, mental flexibility and working memory – among other skills – to manage thoughts and actions (Zelazo, Blair and Willoughby, 2016[4]). Together, these three skills are referred to as executive function. They describe the ability to inhibit impulse responses, direct and sustain short-term attention, revise initial plans and retrieve rules from memory.

Self-regulation is a strong predictor of later health, education and labour-market outcomes

The development of self-regulation skills in early childhood is associated with a wide range of outcomes later in life. These include facilitating the transition into – and success in – school (Blair and Raver, 2015[5]; Mcclelland et al., 2007[6]; Morrison, Cameron and Mcclelland, 2010[7]), higher academic achievement in adolescence, better labour-market outcomes as adults – including on employment and earnings – and better health outcomes (Duckworth, Quinn and Tsukayama, 2012[8]; Tangney, Baumeister and Boone, 2004[9]).

Self-regulation skills are important for a child’s transition to and participation in school (Blair and Peters Razza, 2007[10]; Neuenschwander et al., 2012[11]). Starting school is a time of major change in the physical surroundings and people – including both new peers and educators – that children are accustomed to. It also presents a new set of learning expectations and routines to follow (Dockett, 2001[12]). Children must manage competing stimuli to navigate classroom activities. Self-regulation skills facilitate the learning of new concepts and allow children to engage successfully in classroom activities. These skills also allow them to interact productively with their teachers and peers while managing their own responses (Shonkoff, Phillips and Council, 2000[13]).

A child’s ability to self-regulate is associated with the development of social-emotional, literacy and numeracy skills (Blair and Peters Razza, 2007[10]). For example, working memory (Raghubar, Barnes and Hecht, 2010[14]), inhibition and mental flexibility (Clark, Pritchard and Woodward, 2010[15]) are associated with the development of pre-arithmetic, simple and more complex mathematical skills. These skills allow children to better integrate information they receive in the classroom, and play an important role in academic achievement through late childhood and adolescence (Best, Miller and Naglieri, 2011[16]; Duncan et al., 2007[17]).

Children with more developed self-regulation skills in childhood also demonstrate better long-term health outcomes (Caspi et al., 1998[18]; Daly et al., 2015[19]; Moffitt et al., 2011[20]). This includes lower rates of obesity in adolescence (Evans, Fuller-Rowell and Doan, 2012[21]) and lower levels of anxiety and depression (Blair and Peters Razza, 2007[10]; Buckner, Mezzacappa and Beardslee, 2009[22]). Children and adolescents with more developed self-regulation skills are also less likely to use drugs or receive a criminal conviction (Ayduk et al., 2000[23]; Caspi et al., 1998[18]; Duckworth, Tsukayama and May, 2010[24]; Moffitt et al., 2011[20]).

Children’s environments are associated with their development of self-regulation skills

A combination of genetic and environmental factors shape self-regulation skills (Bridgett et al., 2015[25]; McClelland et al., 2015[3]). Children exposed to poverty, low economic status, abuse or neglect in their home environment are more likely to display deficits in their self-regulation skills than children living in more enabling environments (Noble, Norman and Farah, 2005[26]; Raver, Blair and Willoughby, 2013[27]).

Difficult childhood experiences and toxic stress can significantly impair the self-regulation development of children. Exposure to adverse home environments can limit their opportunities to develop self-regulation skills. Negative early experiences, including multiple and chronic environmental stressors, can cause structural changes in the neural connections of the areas of the brain that control self-regulation (Nelson et al., 2007[28]; McEwen, Nasca and Gray, 2016[29]). Children exposed to cumulative risks are also more likely to have parents who do not provide them with opportunities to practice their self-regulation skills (Wachs, Gurkas and Kontos, 2004[30]; Fuller et al., 2010[31]).

Disparities in socio-economic background are associated with differences in the physical structure and functioning of the parts of the brain that control self-regulation (Hackman and Farah, 2009[32]). The functioning of the prefrontal cortex in children from low socio-economic status backgrounds who are exposed to chronic environmental stressors, for example, is similar to that of individuals with damage to the prefrontal cortex (Kishiyama et al., 2009[33]).

Emotionally positive parenting, an encouraging home environment and high-quality early childhood education and care experiences enable the development of self-regulation skills

Self-regulation skills are malleable. While adverse childhood experiences and toxic stress impede the development of self-regulation skills, positive home environments and early childhood education and care (ECEC) experiences promote these skills.

Emotionally positive parent-child relationships contribute to self-regulation skills across the early years. Parenting styles that include clear and consistent rules and expectations encourage the positive development of self-regulation skills (Blair and Raver, 2012[34]). For example, parenting styles that focus on child autonomy within set limits predict stronger self-regulation in children compared to parenting styles focused on compliance (Bernier, Carlson and Whipple, 2010[35]).

Organised and predictable home environments provide children with a context to develop their self-regulation skills (McClelland et al., 2018[36]). Interactions between children and their parents and caregivers facilitate the regulation of emotions and behaviour. These interactions help children understand their emotions and express them more productively. This, in turn, allows children to regulate their responses to distracting stimuli in their environment (Heatherton and Wagner, 2011[37]).

As with the home environment, structured and predictable environments in ECEC centres are important for children’s self-regulation, engagement and academic outcomes (Ponitz et al., 2009[38]). High-quality ECEC environments enable children to develop self-regulation skills. Examples of high-quality ECEC include stimulating learning environments and positive interactions with teachers and peers.

The International Early Learning and Child Well-being Study (IELS) defines self-regulation skills as inhibition, mental flexibility and working memory

Although the precise definition of which skills and processes make up self-regulation varies across studies and disciplines (Booth, Hennessy and Doyle, 2018[39]), self-regulation skills are highly integrated and influence one another (Anderson and Reidy, 2012[40]). Completing everyday tasks requires adequate development in all of the interdependent parts.

A large body of literature has emphasised a number of key self-regulation skills (Diamond and Lee, 2011[41]; Garon, Bryson and Smith, 2008[42]). These have mostly centred on the influence of inhibition, mental flexibility and working memory skills on later outcomes (McClelland et al., 2010[43]). These three skills together are often referred to as executive function. Executive function skills make up the cognitive component of self-regulation.1 Accordingly, IELS defines self-regulation in the direct assessment as: 1) inhibition – the ability to control impulses and reactions; 2) mental flexibility – the ability to shift between rules according to changing circumstances; and 3) working memory – the ability to retain and process information (Figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1. The three key components of self-regulation

IELS measures self-regulation outcomes through developmentally appropriate and engaging activities

The IELS assessment explores how children’s early learning experiences – including their individual characteristics, home learning environment, and their families’ socio-economic contexts – relate to their self-regulation development. Each of the skills that make up self-regulation in IELS were measured using a single task, which was made up of a number of different items. There was, therefore, a separate task to measure inhibition, mental flexibility and working memory (Table 4.1). Audio and engaging illustrations guided the children through activities on a tablet under the supervision of a study administrator.

Table 4.1. The three skills assessed in the self-regulation domain

|

Content component |

Description |

Assessment task |

|---|---|---|

|

Inhibition |

Ability to resist impulsive responses based on new information |

Stop/go task |

|

Mental flexibility |

Ability to shift between rules according to changing circumstances or to apply different rules in different settings |

Switching task |

|

Working memory |

Ability to store information and manipulate it to complete a given task |

Odd-one-out task |

Inhibition

The inhibition activity assessed a child’s ability to inhibit a learned response in favour of an alternative response. The assessment introduced the child to an image and asked them to touch a button on the screen whenever this image appeared. It then introduced the child to a visually similar image and asked them to touch a different button whenever the new image appeared. Their ability to touch the different button whenever each different image appeared reflected their ability to inhibit their learned response. In sum, the task required the child to respond differently to each of two similar images, presented one after another in a pre-determined but unpredictable sequence.

Mental flexibility

The mental flexibility activity assessed a child’s ability to respond to rules that changed during the activity. The assessment introduced the child to two distinct animals and asked them to touch a different shape on the screen depending on which animal appeared. The assessment then introduced a new rule where the child was asked to touch the alternative shape when each animal appeared. Their ability to adapt to the new inverse rule indicated their mental flexibility.

Working memory

The working memory activity assessed a child’s ability to recall short visual sequences. The child was introduced to a visually distinct zebra placed in one of three rows on a bus. The other two rows on the bus were occupied by other animals. The child was then asked to remember in which of the three rows the zebra was seated and touch the corresponding row in a following image. The assessment was divided into several sections of increasing levels of difficulty involving more rows to remember. If the child did not complete the higher difficulty tasks, the assessment automatically proceeded to the next section.

IELS assesses how children’s self-regulation abilities relate to their individual characteristics, family backgrounds and home learning environments

This chapter presents the outcomes of the IELS assessments of the inhibition, mental flexibility and working memory outcomes of children in Estonia. The chapter details how children’s self-regulation outcomes relate to their individual characteristics, family backgrounds and home learning environments.

The self-regulation outcomes of children were measured directly through the assessments. Indirect information on children’s self-regulation development was also collected through questionnaires administered to children’s parents and educators. Parents and educators were asked to assess each child’s overall self-regulation development, defined as whether the child was attentive, organised or in control of their actions.

The chapter presents the results of both the direct assessment of children’s inhibition, mental flexibility, and working memory outcomes, as well as how parents and educators perceived children’s overall self-regulation development. It highlights similarities and differences between outcomes in Estonia and those in England and the United States.

Self-regulation skills of five-year-olds in Estonia

On average, the self-regulation skills of children in Estonia are above the overall mean of participating countries

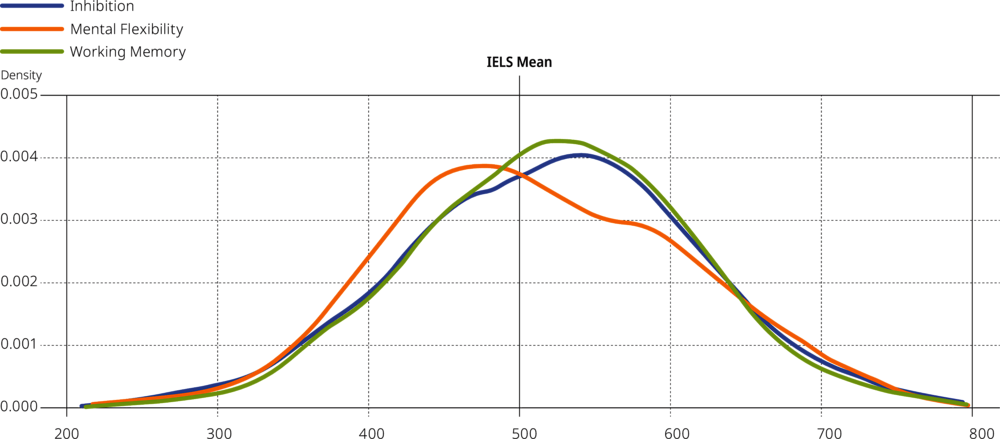

On average, five-year-olds in Estonia were about 20 points above the overall mean of participating countries (500 IELS points) on inhibition (520), 11 points above on mental flexibility (511) and 21 points above on working memory (521).

Average inhibition outcomes in Estonia were about equal to those in the United States and significantly higher than those in England. Average mental flexibility and working memory outcomes in Estonia were about equal to those in England and significantly higher than those in the United States.

The spread between the outcomes of the bottom quartile and those of the top quartile of children in Estonia was greater for mental flexibility (141 points) than for inhibition (130 points) or working memory (128 points). The spread in mental flexibility outcomes was also greater in Estonia than in the United States, meaning that the difference in outcomes between the top and bottom quartiles in Estonia was greater than in the United States. The spread in working memory outcomes was greater in Estonia than in England, meaning that the differences in outcomes between the top and bottom quartiles in Estonia are greater than in England. The spread in inhibition outcomes was about the same across the three countries.

The distribution of inhibition and working memory outcomes in Estonia was generally to the right of the overall mean of participating countries, reflecting Estonia’s higher average outcomes on inhibition and working memory at age five (Figure 4.2). There was greater distribution in the mental flexibility outcomes. The lower tail of the distribution was smaller than the upper tail, which results in an average score above the overall mean.

Figure 4.2. Distribution of self-regulation scores, Estonia

Note: Distributions produced using the first plausible value only.

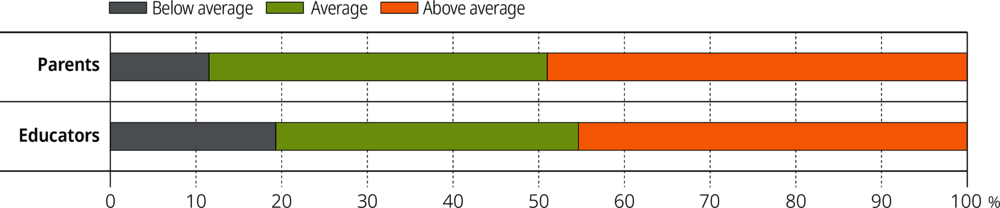

Parents in Estonia are less likely than educators to report that their child, or the child they teach, is developing below average self-regulation skills

Parents and educators were asked to comment on a child’s overall self-regulation development (e.g. attentiveness, organisation, in control of actions), which differed from self-regulation sub-domains measured by the IELS direct assessments of children. Parents in Estonia were about as likely as educators to report that their child, or the child they teach, was developing above average self-regulation skills. However, they were significantly less likely to rate their child as developing below average self-regulation skills: about 12% of parents compared to about 19% of educators (Figure 4.3).

Figure 4.3. Self-regulation development as reported by parents and educators, Estonia

This may be partly due to children behaving differently in a home environment than they would in an ECEC environment. Educators may also have more experience assessing the level of development of a child as they have access to a bigger group of children to provide a comparison, among other factors.

Individual characteristics and self-regulation skills

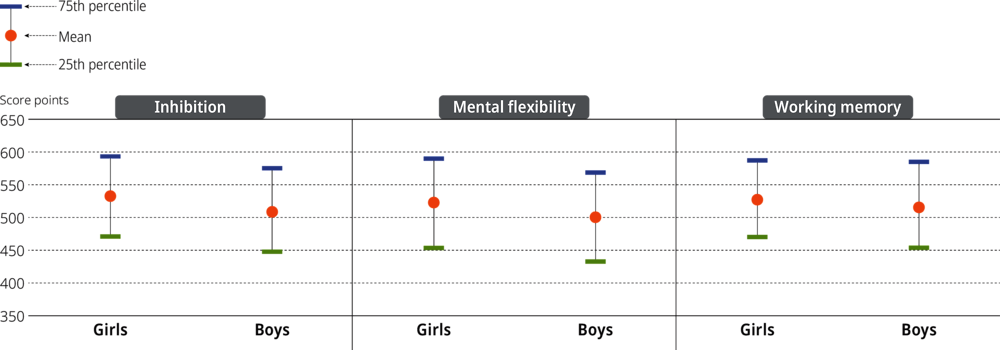

Girls have higher self-regulation outcomes than boys

A child’s individual characteristics are associated with their early learning outcomes. The self-regulation outcomes of girls were significantly higher than those of boys in Estonia. The gender gap was a statistically significant 24 IELS points on inhibition outcomes, 23 IELS points on mental flexibility outcomes and 12 IELS points on working memory outcomes (Figure 4.4). This gender difference in outcomes is consistent with the pattern observed for emergent literacy and numeracy skills, as well as the perceptions of parents and educators.

In the United States there were also significant gaps in the inhibition and working memory outcomes of girls and boys, although no differences in their mental flexibility outcomes. In England, the gender gap on inhibition outcomes was reversed, with the outcomes of boys in England higher than those of girls. There were no differences in the outcomes of boys and girls on mental flexibility and working memory.

Figure 4.4. Self-regulation scores by gender, Estonia

Note: Differences are statistically significant, except for working memory scores at the 75th percentile

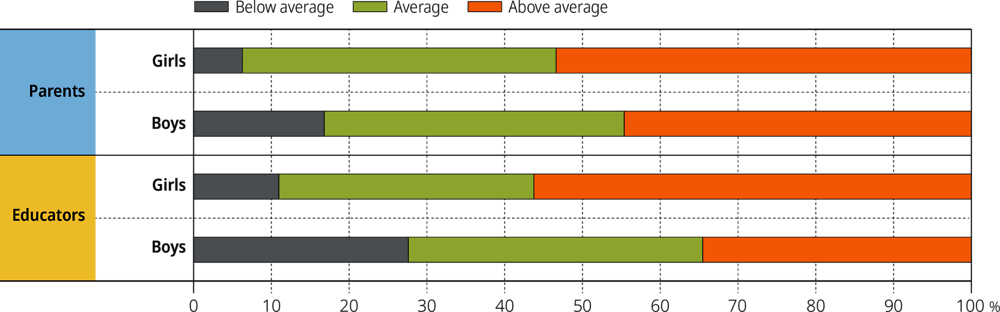

Parents and educators perceive girls as more likely than boys to have developed above average self-regulation skills

When asked to report on how they perceived children’s overall self-regulation development, both parents and educators in Estonia were, on average, more likely to report girls rather than boys as developing above average skills. Educators perceived about 56% of girls as developing above average skills compared to 35% of boys (Figure 4.5).

Figure 4.5. Self-regulation development as reported by parents and educators by gender, Estonia

Educators and parents also perceived boys as more likely to be developing below average self-regulation skills, with educators perceiving about 28% of boys and 11% of girls as developing below average self-regulation skills. The gender gap in parent and educator reports of self-regulation development was consistent with the outcomes of the direct assessment, where the inhibition, mental flexibility and working memory outcomes of girls were higher than those of boys.

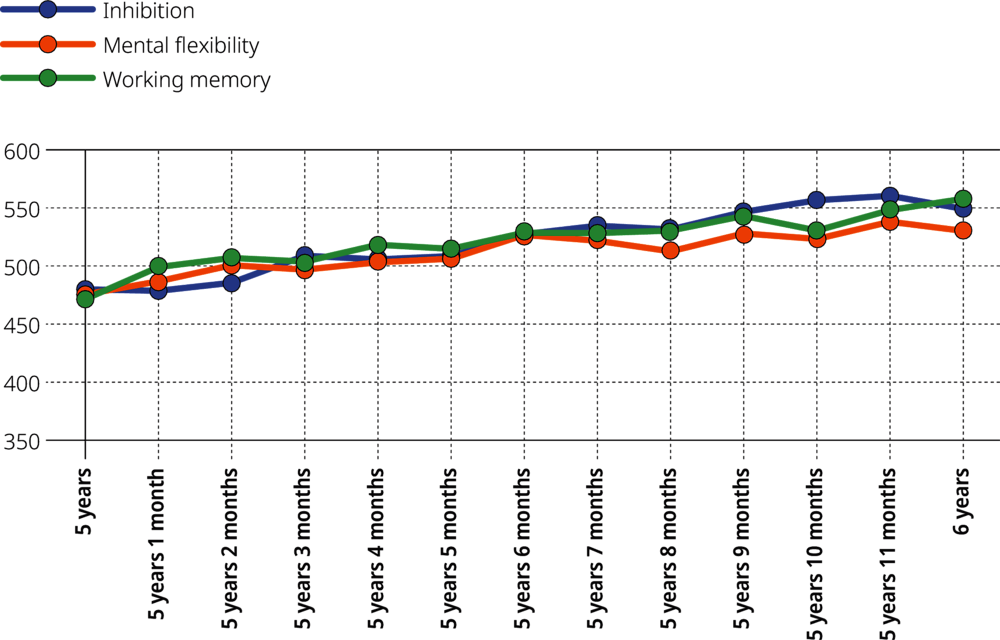

A child’s self-regulation outcomes increase with every month between their fifth and sixth birthday

Children’s self-regulation skills develop as they grow older. Between the ages of five and six, the average inhibition outcomes of children in Estonia increased by 69 IELS points, their mental flexibility outcomes by 55 points and their working memory outcomes by 86 points (Figure 4.6). By the age of five years four months, the average self-regulation skills of children in Estonia were higher than the overall mean of participating countries for each of the assessed skills.

Figure 4.6. Self-regulation scores by age of child in months, Estonia

The average difference in the inhibition and mental flexibility outcomes of children between the ages of five years one month and six years were similar across the three countries participating in IELS. The average difference working memory outcomes in that year of growth were similar in both England and the United States, but significantly lower in Estonia.

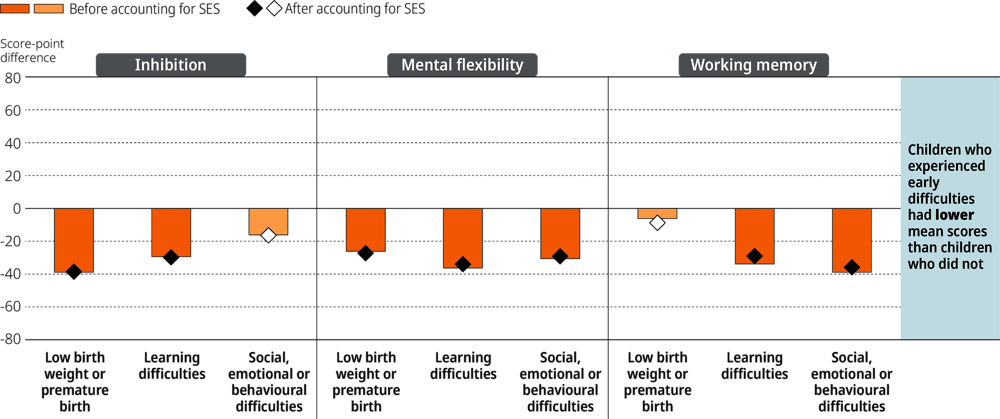

Children who had experienced low birth weight or premature birth, learning difficulties, or social, emotional or behavioural difficulties have lower average self-regulation outcomes than those who had not

IELS asked parents to indicate whether their child had ever experienced a number of potential difficulties that might affect their early learning outcomes. Results indicated that experiencing low birth weight2 or premature birth, learning difficulties, or social, emotional or behavioural difficulties early in life was negatively related to a child’s self-regulation skills at age five.

The inhibition and mental flexibility scores of children who experienced low birth weight or premature birth were lower than those of other children. The inhibition outcomes of children with low birth weight or premature birth were 39 points lower than those of other children, after accounting for socio-economic status and the experience of the other early difficulties (Figure 4.7). The difference in mental flexibility outcomes was about 27 points. There was no significant difference in the working memory outcomes of children who experienced low birth weight or premature birth and those who did not. The self-regulation outcomes of both girls and boys in Estonia were associated with having experienced low birth weight or premature birth.

Figure 4.7. Relative associations between early difficulties and self-regulation scores, Estonia

The self-regulation outcomes of children who had experienced learning difficulties were lower than those of children who had not experienced such difficulties: 30 points lower on inhibition, 34 points lower on mental flexibility and 29 points lower on working memory, after accounting for socio-economic status and the experience of the other early difficulties (Figure 4.7).

The association of having experienced learning difficulties with self-regulation outcomes was different for boys and girls. The outcomes of girls who had experienced learning difficulties were similar to those of girls who had not. The inhibition and mental flexibility outcomes of boys whose parents identified as having experienced learning difficulties were significantly lower than those of boys whose parents did not after accounting for socio-economic status and the experience of the other early difficulties.

Experiencing social, emotional or behavioural difficulties also had a negative association with mental flexibility and working memory outcomes. The outcomes of children who had experienced such difficulties were 29 points lower on mental flexibility and 36 points lower on working memory than the outcomes of children who had not after accounting for socio-economic status and the experience of the other early difficulties (Figure 4.7).

As with learning difficulties, the gender of the child who had experienced social, emotional or behavioural difficulties also influenced their self-regulation outcomes. There were no differences in the outcomes of girls who had experienced social, emotional or behavioural difficulties and those who had not across the three self-regulation domains. The mental flexibility and working memory outcomes of boys who had experienced social, emotional or behavioural difficulties were lower than those of boys who had not.

Home and family characteristics and self-regulation skills

A child’s parents play an important role in all of aspects of their upbringing, from the context of their home environment to their activities outside the home. The home environment that a child grows up in and their interactions with their parents and environment shape a child’s early learning experiences and opportunities.

Family background and socio-economic status were positively associated with a child’s self-regulation development. The combination of household income, parental occupation and parental educational completion – that together create the socio-economic index applied in this study – interact with a child’s individual characteristics to influence the development of their self-regulation skills. The children of parents with higher levels of education exhibit higher self-regulation skills. Families with higher economic resources are able to spend more money on early learning activities and materials for their children.

Children’s working memory outcomes increase with the socio-economic status of their family

The relationship between socio-economic status and self-regulation skills in Estonia, however, was less pronounced than in the other two countries that participated in the study. The socio-economic status of a child’s family in Estonia, for example, had no significant association with the inhibition and mental flexibility outcomes of five-year-old children (Figure 4.8).

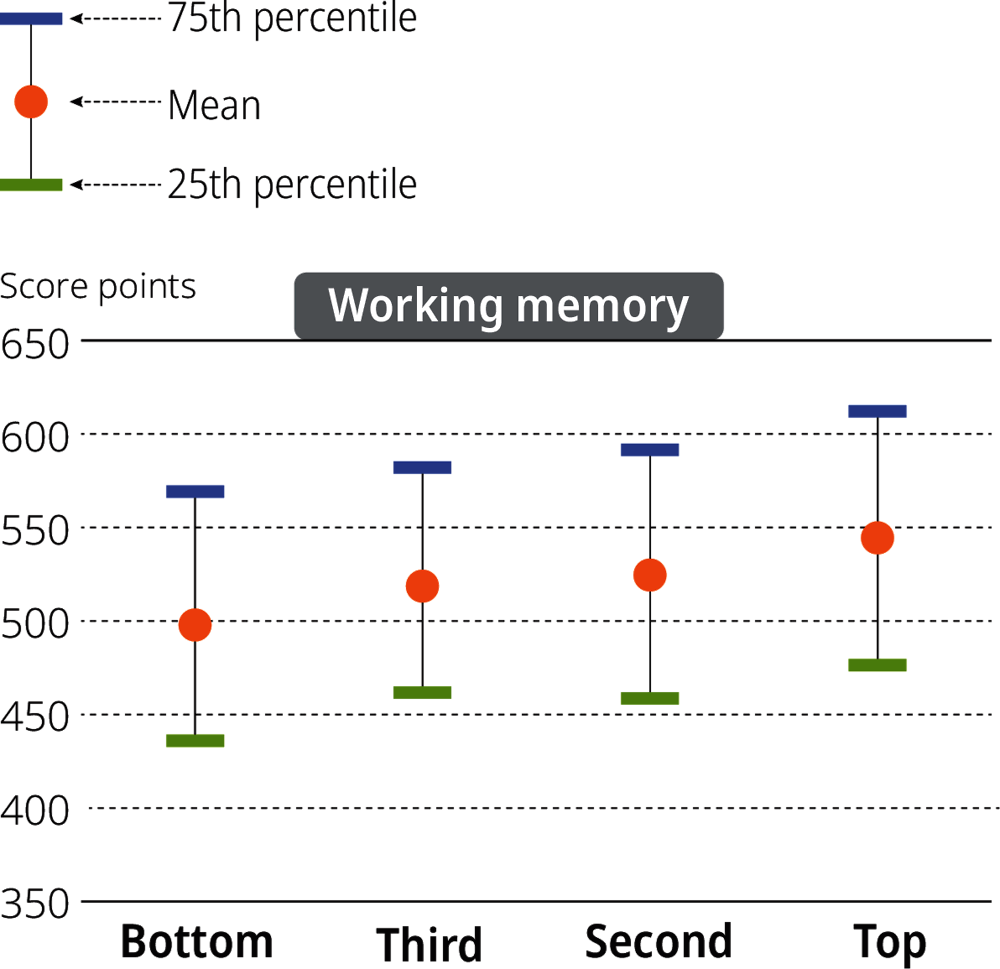

Figure 4.8. Working memory scores by socio-economic quartile, Estonia

The socio-economic status of children’s families, however, was significantly related to children’s working memory outcomes. The outcomes of children in Estonia from families in the lowest quartile of socio-economic status were, on average, 46 points below those of children in the most advantaged quartile (Figure 4.8). There was no difference in the association of socio-economic status with self-regulation outcomes for boys and girls.

Parents and educators are more likely to report a child as developing above average self-regulation skills if they are from a family in a higher socio-economic quartile

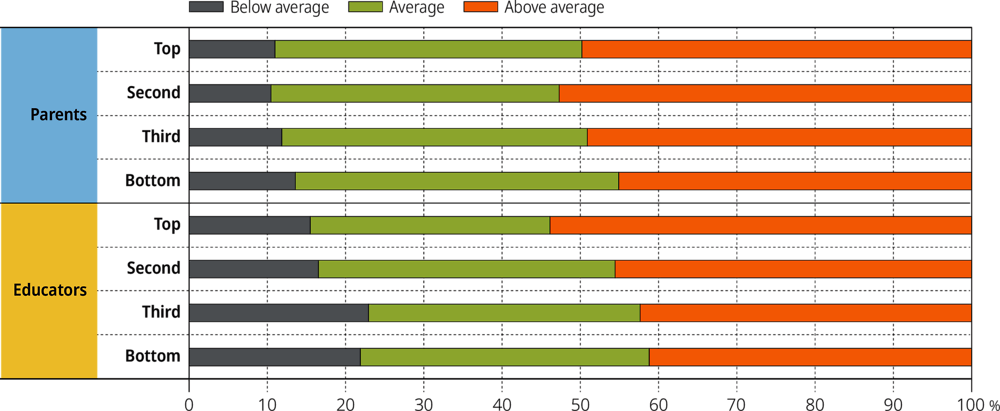

Both parents and educators were more likely to perceive a child from a family in the top quartile of socio-economic status as developing above average self-regulation skills than a child in the bottom quartile (Figure 4.9). They also perceived children from families in the top quartile as less likely to be developing below average self-regulation skills than a child in the bottom quartile.

Figure 4.9. Self-regulation development as reported by parents and educators by socio-economic quartile, Estonia

Parents and educators reported fewer differences in self-regulation development between children from families in the second, third and top quartiles, and reported children in those quartiles as about equally likely to be developing both above and below average self-regulation skills. Educators perceived children from families in the second and top quartiles as the groups least likely to be developing below average skills.

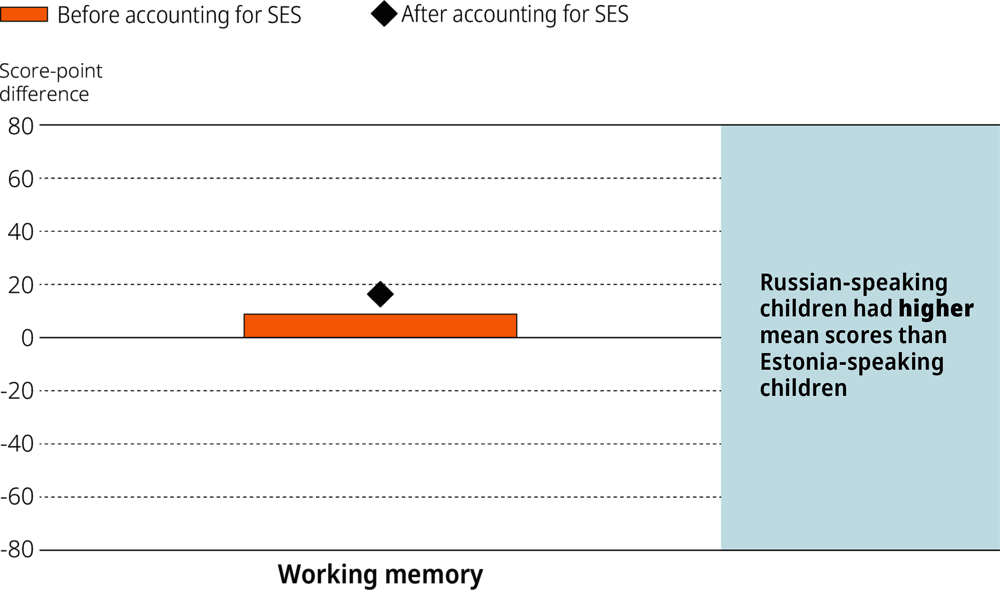

The working memory outcomes of Russian-speaking children are higher than those of Estonian-speaking children, after accounting for socio-economic status

The working memory outcomes of Russian-speaking children were significantly higher than those of their Estonian-speaking peers (by about 16 points), after accounting for socio-economic status (Figure 4.10). There were no significant differences in inhibition and mental flexibility outcomes.

Figure 4.10. Working memory scores by child language, Estonia

There were larger differences in the outcomes of girls than boys based on the child’s language. Russian-speaking girls scored 22 points higher on inhibition and 32 points higher on working memory than Estonian-speaking girls after accounting for socio-economic status. There were no significant differences in the outcomes of boys.

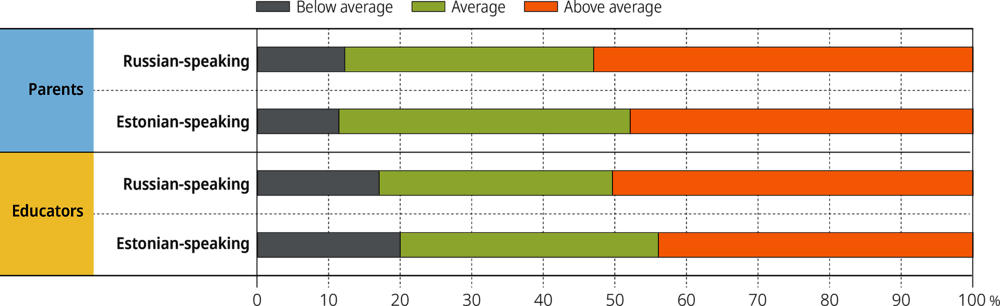

There are limited differences in how educators and parents of Estonian-speaking children and Russian-speaking children perceive their self-regulation development

Parents and educators in Estonia perceived about half of five-year-olds as developing above average self-regulation skills (Figure 4.11). This perception did not differ much between Estonian-speaking children and Russian-speaking children. These children were perceived as about equally likely to be developing below average and above average skills by both their parents and educators.

Figure 4.11. Self-regulation development as reported by parents and educators by child language, Estonia

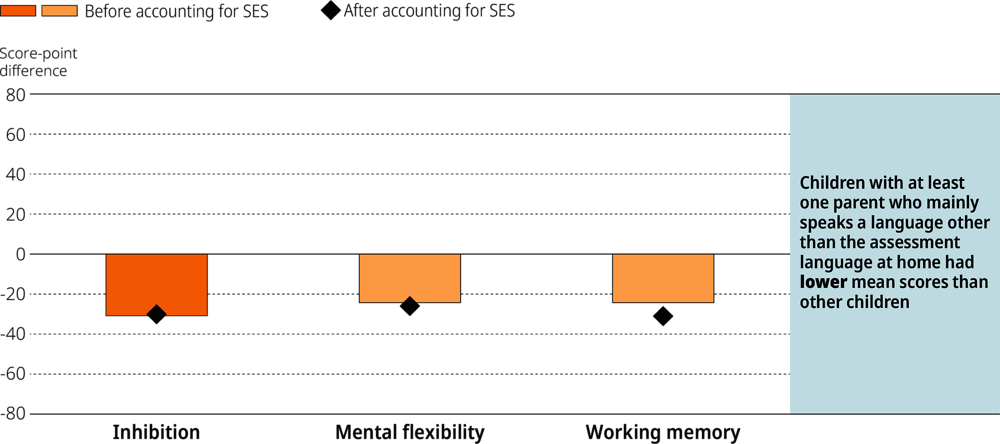

Children with at least one parent who mainly speaks a language other than the assessment language have lower self-regulation scores, after accounting for socio-economic status

In Estonia, 6% of five-year-olds lived in homes where at least one parent mostly spoke a language other than the assessment languages of Estonian or Russian. These children had significantly lower mean self-regulation scores after accounting for socio-economic status (by 31 points on inhibition, 26 points on mental flexibility and 31 points on working memory) (Figure 4.12).

Figure 4.12. Self-regulation scores by home language, Estonia

The association between home language and each of the self-regulation outcomes assessed in IELS was different for boys and girls, after accounting for socio-economic status. The inhibition, mental flexibility and working memory outcomes of the boys of parents (or the single parent) who primarily spoke a language other than the assessment language were significantly lower than those of boys whose parents both (or single parent) primarily spoke the assessment language. There were no differences in the outcomes of girls in these two groups.

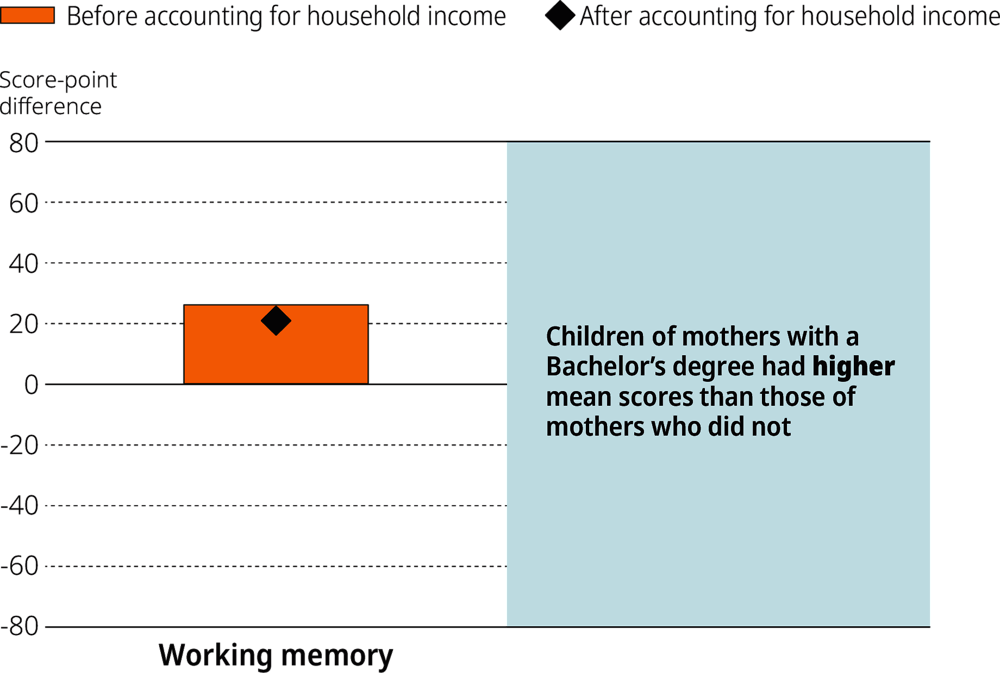

The working memory outcomes of the children of mothers with at least a bachelor’s degree are higher than those of the children of mothers who have not completed any tertiary education

Maternal education was a significant predictor of working memory outcomes. The children of mothers who had completed at least a bachelor’s degree had significantly higher working memory outcomes (21 points) than the children of mothers who had not completed tertiary education, after accounting for household income (Figure 4.13). A mother’s completion of a bachelor’s degree was not related to her children’s inhibition or mental flexibility outcomes after controlling for household income.

Figure 4.13. Working memory scores by mother’s educational attainment, Estonia

A mother’s completion of at least a bachelor’s degree was associated with the working memory outcomes of girls but not boys. The working memory outcomes of the girls of mothers who had completed at least a bachelor’s degree were 27 points higher than the girls of mothers who had not, after controlling for household income.

The association between a mother’s educational attainment and her child’s self-regulation scores was most pronounced in England, where any level of education above lower secondary predicted higher mental flexibility and working memory scores, after accounting for household income. In the United States, mental flexibility scores were higher for children of mothers who had completed at least a bachelor’s degree than for children of mothers who had completed only primary education.

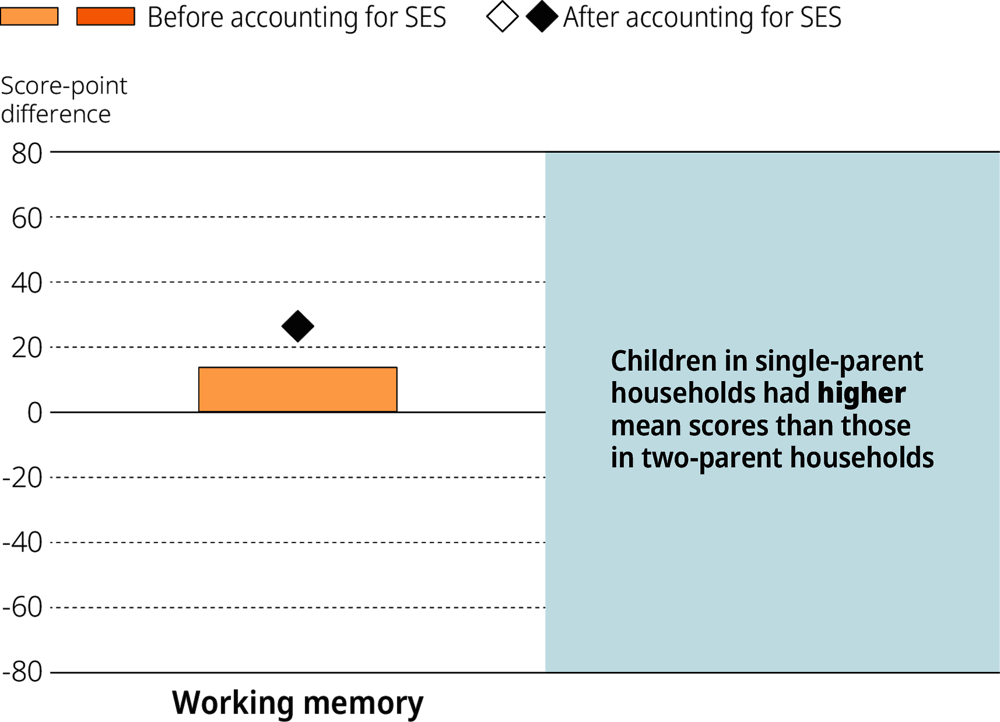

The working memory outcomes of children in single-parent households are higher than those of children in two-parent households, after accounting for socio-economic status

Family structure is associated with self-regulation skills in different ways. The presence of two parents in a home may increase the possibility that children have more stimulating interactions. It may also facilitate employment opportunities and increase household income.

In Estonia, however, the working memory outcomes of children in single-parent homes were higher than those of children in two-parent homes by 26 points, after accounting for socio-economic status (Figure 4.14). There were no significant differences in the inhibition and mental flexibility outcomes of children in single- and two-parent households.

Figure 4.14. Working memory scores of children in single-parent households and two-parent, Estonia

The relationship between family structure and working memory outcomes was different for boys and girls, after accounting for socio-economic status. There was no difference in the working memory outcomes of boys in single-parent homes and boys in two-parent homes, but there was a significant difference for girls, with the working memory outcomes of girls in single-parent homes 32 points higher than those of girls in two-parent homes.

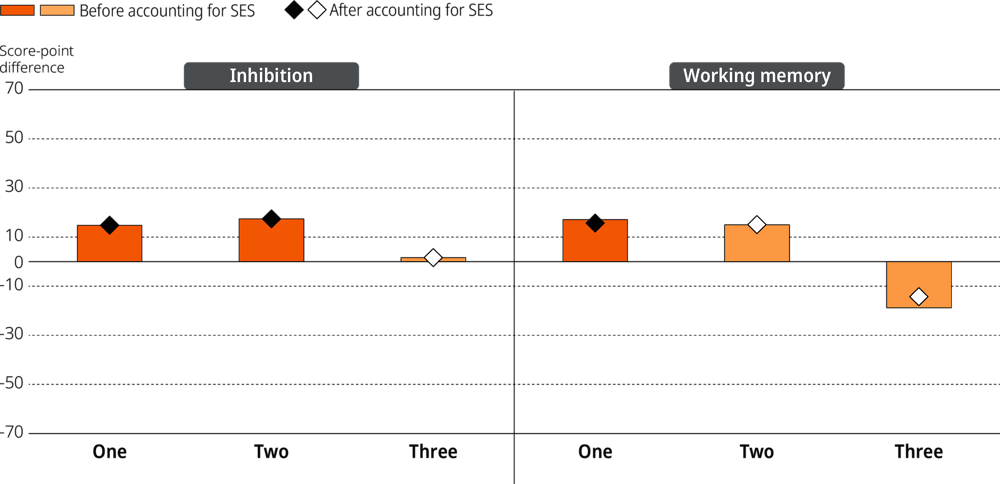

The inhibition and working memory outcomes of children with one or two siblings are higher than those of children with no siblings

The number of siblings a child had was related to their inhibition and working memory outcomes. The inhibition (15 points) and working memory outcomes (16 points) of children with one sibling were higher than those of children with no siblings, after accounting for socio-economic status (Figure 4.15). The inhibition outcomes of children with two siblings were 17 points higher than those with no siblings.

Figure 4.15. Inhibition and working memory scores by number of siblings, Estonia

The inhibition and working memory outcomes were different for boys and girls by number of siblings. The inhibition outcomes of boys with two siblings were 24 points higher than those of boys with no siblings, after accounting for socio-economic status. The outcomes of boys with one sibling or with more than two siblings, however, were no different from the outcomes of boys with no siblings. The working memory outcomes of boys with one or two siblings were 23 and 27 points higher, respectively, than those of boys with no siblings.

The association of siblings with self-regulation outcomes was different in the three countries participating in IELS. The number of siblings did not influence the self-regulation skills of children in England. In the United States, the working memory outcomes of children with one or two siblings were significantly higher than those of children with no siblings.

Home learning environment and self-regulation skills

A child’s home learning environment and the quality of their interactions with their parents influences early learning outcomes. A child’s access to developmentally-appropriate books, toys and activities, and the quality of their interactions with their parents, promotes their opportunities for early learning development.

In the context of this report, IELS defines a child’s home learning environment as the number of children’s books in their home, the frequency with which a child is read to, the frequency with which they are taken to an activity outside of the home and the level of parental involvement in activities taking place at the preschool. Additionally, parents were asked whether their child used a digital device and, if so, the frequency of that usage.

The number of children’s books in the home is predictive of a child’s mental flexibility and working memory outcomes

In Estonia, the number of children’s books that a child had access to in their home – including those from a public or preschool library – predicted their mental flexibility and working memory outcomes. This relationship held even after accounting for the income or socio-economic status of a child’s family. The number of books that a child had access to in their home was not related to their inhibition outcomes.

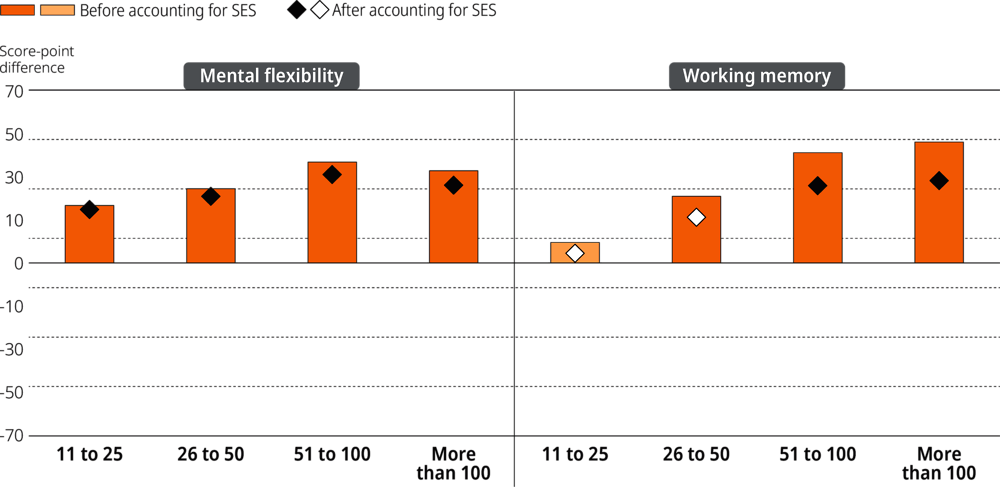

The mental flexibility outcomes of children with access to more than 10 books in their home were significantly higher than those of children with 10 books or fewer, even after accounting for socio-economic status. The gap in development between children with 10 books or fewer in their home and those with between 26 and 50, for example, was 27 points on mental flexibility outcomes (Figure 4.16).

Figure 4.16. Self-regulation scores by number of children’s books in the home, Estonia

The working memory scores of children with access to over 50 children’s books in their home were higher than those of children with access to 10 books or fewer. For example, the gap in working memory outcomes between children with 10 books or fewer in their home and those with between 51 and 100 was 31 points (Figure 4.16).

The number of books a child had access to in their home related differently to the self-regulation outcomes of boys and girls. The self-regulation outcomes of girls with more than 10 books were no different than the outcomes of girls with 10 books or fewer, after accounting for socio-economic status. The self-regulation skills of boys, however, increased with the number of children’s books in their home, even after accounting for socio-economic status. The mental flexibility outcomes of boys with access to any number of books above 10 were higher than those of boys with access to 10 books or fewer. Similarly, the inhibition and working memory outcomes of boys with any number of books greater than 25 were higher than those of boys with access to 10 books or fewer.

The inhibition and working memory outcomes of children read to at least once or twice a week are higher than those of children read to less often

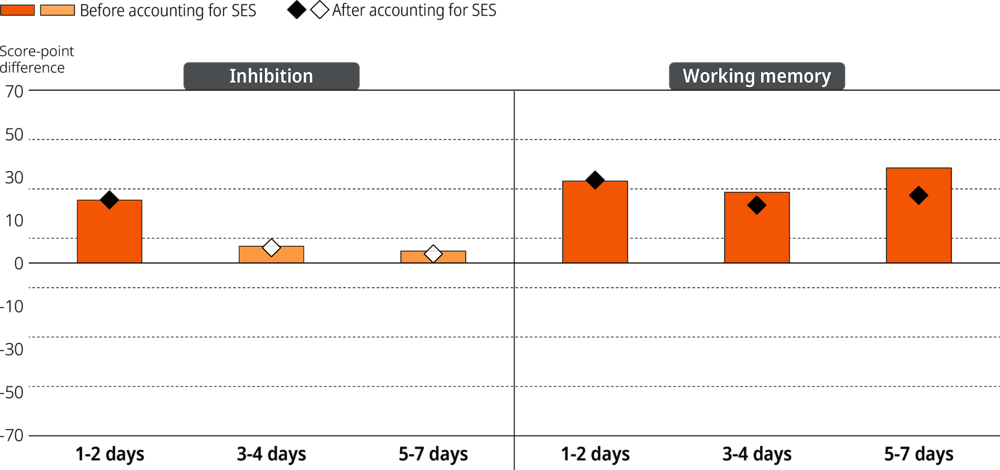

The frequency with which a child was read to from a book or e-book was significantly related to their inhibition and working memory outcomes, even after accounting for socio-economic status. It was not related to their mental flexibility outcomes.

The inhibition outcomes of children who were read to once or twice a week were 25 points higher than those of children read to less than once a week (Figure 4.17). The outcomes of children who were read to between three and seven days a week were no different from those of children who were read to once a week.

Figure 4.17. Inhibition and working memory scores by frequency child is read to, Estonia

The working memory outcomes of children read to once or twice a week were 33 points higher than those of children read to less than once a week, after accounting for socio-economic status (Figure 4.17). The outcomes of children read to between three and four days a week were 23 points higher than those of children read to less than once a week, and the outcomes of children read to almost every day were 27 points higher.

While the act of being read to is related to the development of a child’s emergent literacy skills, the quality and type of reading experience may be more important for self-regulation development. For example, direct interaction between a child and the reading material – either in the interactivity of the reading material or the reading experience with their caregiver – may be more important for self-regulation outcomes.

The mental flexibility outcomes of boys whose parents are moderately or strongly involved in activities taking place at preschool are higher than those of boys whose parents are slightly or not involved, after accounting for socio-economic status

On average, the self-regulation outcomes of children whose parents were perceived by educators as being slightly or not involved in activities taking place at preschool were no different from those whose parents were perceived as being strongly or moderately involved, after accounting for socio-economic status. While differences existed before accounting for socio-economic status, these were driven by the parents of children from higher socio-economic families being more involved in activities at their child’s centre.

The benefit of having an involved parent, however, was different for girls and boys. While there were no differences in the self-regulation outcomes of girls, the mental flexibility outcomes of the boys of parents moderately or strongly involved in activities at the centre were 22 points higher than those of the boys of parents slightly or not involved after accounting for socio-economic status.

The frequency with which a child is taken to a special or paid activity outside of the home is related to their inhibition and working memory skills, even after accounting for socio-economic status

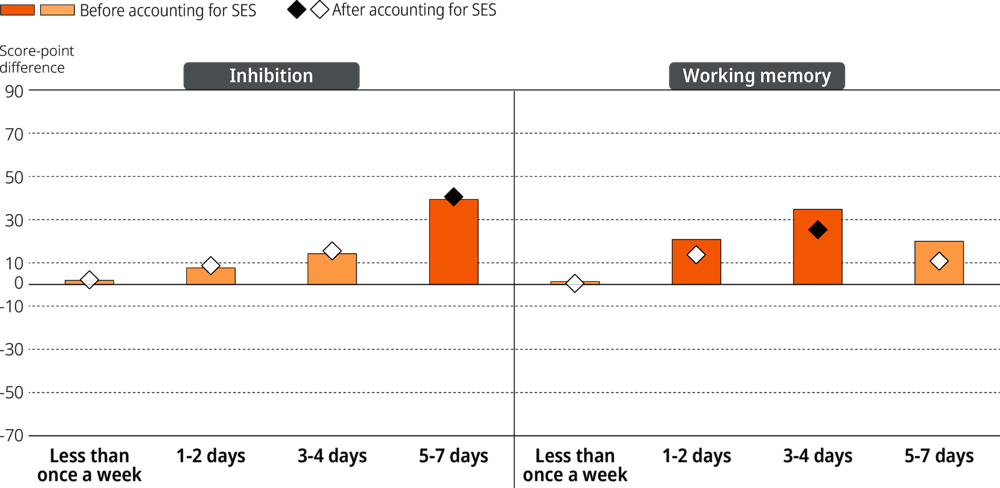

Taking a child to a special or paid activity outside of the home – such as a sports club or dance, swimming and language lessons – was positively related to their inhibition and working memory outcomes, even after accounting for socio-economic status.

The inhibition outcomes of children who attended a special activity five to seven days a week were 41 points higher than those of children who never attended an activity, after accounting for socio-economic status (Figure 4.18). Attending activities less frequently than five to seven days a week was not related to a child’s inhibition outcomes.

Figure 4.18. Inhibition and working memory scores by participation in special or paid activity outside of the home, Estonia

The working memory outcomes of children who attended an activity almost daily were no different from those who never attended an activity. However, the working memory outcomes of children who attended a special activity between three and four days a week were significantly higher (25 points) than those of children who never attended an activity (Figure 4.18).

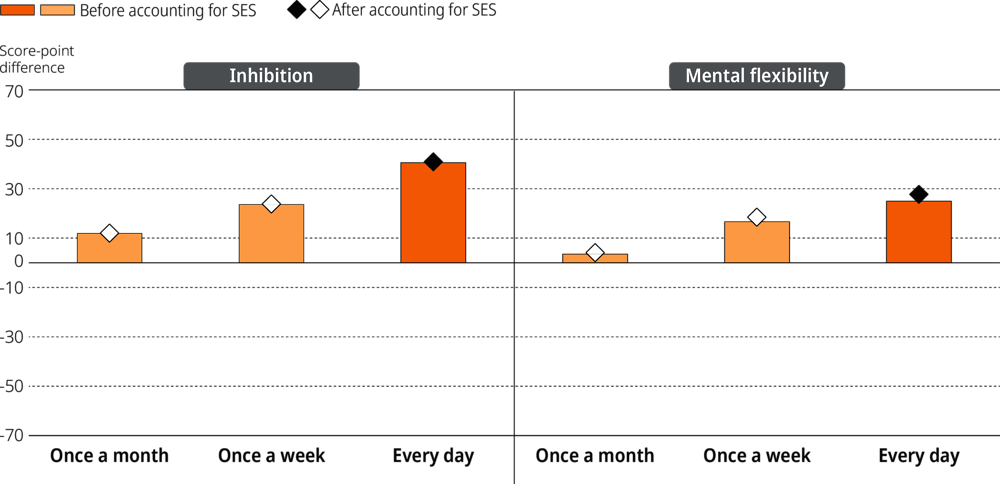

Five-year olds who use a digital device every day have higher inhibition and mental flexibility outcomes than those who hardly ever use one

The frequency with which a child used a digital device – including a desktop or laptop computer, tablet device or smartphone – was significantly related to their inhibition and mental flexibility outcomes in Estonia, after accounting for socio-economic status, but not related to their working memory outcomes.

The outcomes of children who used a device every day were 41 points higher on inhibition and 28 points higher on mental flexibility than those of children who never or hardly ever used a device, after accounting for socio-economic status (Figure 4.19). While the use of a digital device in and of itself may not have been related to a child’s outcomes, the types of activities that a child engaged in while on those devices may have contributed to the development of inhibition and mental flexibility skills.

Figure 4.19. Inhibition and mental flexibility scores by use of digital devices, Estonia

The observed difference in outcomes based on digital device use may be partly attributable to the assessment of a child’s self-regulation skills through a tablet-based direct assessment. However, the frequency of use that predicted different self-regulation outcomes differed by participating countries. Using a device every day predicted higher working memory outcomes in England, after accounting for socio-economic status. In the United States, using a device at least once a week predicted higher mental flexibility and working memory outcomes. The inconsistency with which digital device use predicted self-regulation outcomes implies that differences are more likely to be specific to a child within a given country, rather than to a tablet-based direct assessment.

Assessing the combined effects of child and family characteristics on self-regulation scores

Analysing how the variables that predict self-regulation outcomes presented in this chapter also relate to one another through a regression model gives insight into which factors contribute most to the observed outcomes. Such results do not provide a causal explanation of which factors lead to changes in a child’s self-regulation outcomes; however, they do provide a better understanding of which child-, family- and home-level variables predict self-regulation outcomes.

Variables that were significantly related to self-regulation scores were included in regression models to assess how well they explained variation in the scores. Variables that were not significant in the models were removed one at a time3 until all remaining variables were significantly related to the outcome.

The results of the regression models also provide an opportunity to quantify score point differences in terms of months of child development on a given skill. For example, the results of the regression model indicate that children’s inhibition scores increase by an average of over 7.5 points a month between the ages of five- and six-years old. This equates to about 93 points for the year between the ages of five- and six-years old. Their mental flexibility scores increase by over 5 points a month—or about 62 points a year—and their working memory scores increase by over 5.5 points a month—or over 67 points a year. This difference will be used to quantify what a score-point difference implies in terms of months of child self-regulation development.

Inhibition outcomes are related to children’s gender, experience of early difficulties and the primary language of their parents

A child’s individual characteristics and their home background uniquely predicted their inhibition outcomes, after accounting for all variables in the model (Table 4.2). The outcomes of boys were about 20 points lower than those of girls. This translates to a gap of over 2.5 months of inhibition development at the age of five.

Table 4.2. Results of the multiple regression model of inhibition, Estonia

|

Variable |

B |

SE |

p |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Child is a boy |

-20.96 |

6.00 |

0.00 |

|

Age (months) |

7.72 |

0.85 |

0.00 |

|

Low birth weight or premature birth |

-37.37 |

9.90 |

0.00 |

|

Learning difficulties |

-29.25 |

12.52 |

0.02 |

|

Home language* |

-25.91 |

11.93 |

0.03 |

|

Information on home language missing |

-15.79 |

22.71 |

0.487 |

|

Intercept |

456.62 |

11.65 |

|

Note: p-values in bold indicate statistical significance. B = regression coefficients. SE = Standard Error. The intercept is the estimated score of a child in the reference category of each categorical variable, aged 5 years 6 months, and with a mean value for socio-economic status.

* *Variable has a missing indicator to preserve cases in the dataset.

A child’s experience of early difficulties also predicted their inhibition outcomes at the age of five. The outcomes of children born prematurely or with a birth weight of under 2.5 kg were about 37 points – or under 5 months of development – lower than those of children who were not. The outcomes of children who had experienced learning difficulties were 29 points lower than the outcomes of those who had not. This equates to over 3.5 months of inhibition development.

As with a child’s individual characteristics, their home background was a significant predictor of inhibition outcomes. The inhibition outcomes of children who lived in homes where at least one parent primarily spoke a language other than the assessment language were lower than those of children in homes where both parents (or the single parent) primarily spoke the assessment language, after accounting for all other factors in the model. This gap was of about 26 points – or the equivalent of over 3 months of inhibition development.

Mental flexibility outcomes are related to children’s gender, experience of early difficulties and access to children’s books

A child’s individual characteristics and their home background uniquely predicted their mental flexibility outcomes, after accounting for all variables in the model (Table 4.3). The outcomes of boys were about 18 points lower than those of girls. This represents a gap of about 3.5 months of mental flexibility development at the age of five.

Table 4.3. Results of the multiple regression model of mental flexibility, Estonia

|

Variable |

B |

SE |

p |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Child is a boy |

-18.12 |

5.98 |

0.00 |

|

Age (months) |

5.16 |

0.88 |

0.00 |

|

Low birth weight or premature birth |

-26.12 |

10.00 |

0.01 |

|

Learning difficulties |

-28.50 |

12.00 |

0.02 |

|

Social, emotional or behavioural difficulties |

-27.78 |

10.16 |

0.01 |

|

Access to children’s books |

Reference group |

||

|

0 to 10 |

|||

|

11 to 25 |

23.88 |

10.98 |

0.03 |

|

26 to 50 |

31.30 |

9.94 |

0.00 |

|

51 to 100 |

41.59 |

11.00 |

0.00 |

|

More than 100 |

40.04 |

12.60 |

0.00 |

|

Intercept |

447.10 |

17.14 |

|

Note: p-values in bold indicate statistical significance. B = regression coefficients. SE = Standard Error. The intercept is the estimated score of a child in the reference category of each categorical variable, aged 5 years 6 months, and with a mean value for socio-economic status.

A child’s experience of early difficulties also predicted their mental flexibility outcomes at the age of five. The outcomes of children born prematurely or with a birth weight under 2.5 kg were about 26 points – or over 5 months of development – lower than those of other children born. The outcomes of children who had experienced learning difficulties were 28.5 points lower than the outcomes of those who had not. This equates to about 5.5 months of mental flexibility development. Similarly, the mental flexibility scores of children who experienced social, emotional or behavioural difficulties were over 27.5 points lower than those that did not. This equates to over 5 months of mental flexibility development.

A child’s home background was a significant predictor of mental flexibility outcomes. The scores of children with access to over 10 books were significantly higher than those of children with access to fewer than 10. For example, the average gap in outcomes between children with access to 10 books or fewer and those with between 26 and 50 books was over 30 points. This equates to about over 6 months of mental flexibility development.

Working memory outcomes are related to children’s experience of early difficulties, the socioeconomic status of their households, their household structures and their access to children’s books

A child’s individual characteristics, their family background and their home environment predicted their working memory outcomes, after accounting for all variables in the model (Table 4.4). Unlike their inhibition and mental flexibility outcomes, a child’s gender and their experience of low birth weight did not predict their working memory outcomes. However, the socio-economic background of a child’s family and being from a single-parent household did predict working memory outcomes.

Table 4.4. Results of the multiple regression model of working memory, Estonia

|

Variable |

B |

SE |

p |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Age (months) |

5.56 |

0.88 |

0.00 |

|

Learning difficulties |

-27.73 |

12.06 |

0.02 |

|

Social, emotional or behavioural difficulties |

-39.46 |

11.38 |

0.00 |

|

Socio-economic status quartile |

Reference group |

||

|

Bottom |

|||

|

3rd |

12.15 |

9.31 |

0.19 |

|

2nd |

15.06 |

10.02 |

0.13 |

|

Top |

33.11 |

11.66 |

0.01 |

|

Single parent* |

25.84 |

12.04 |

0.03 |

|

Information on number of parents missing |

-10.54 |

15.87 |

0.51 |

|

Access to children’s books |

Reference group |

||

|

0 to 10 |

|||

|

11 to 25 |

4.05 |

10.27 |

0.69 |

|

26 to 50 |

18.02 |

9.89 |

0.07 |

|

51 to 100 |

30.58 |

10.31 |

0.00 |

|

More than 100 |

32.42 |

14.07 |

0.02 |

|

Intercept |

463.24 |

12.54 |

|

Note: p-values in bold indicate statistical significance. B = regression coefficients. SE = Standard Error. The intercept is the estimated score of a child in the reference category of each categorical variable, aged 5 years 6 months, and with a mean value for socio-economic status.

The outcomes of children reported as having experienced learning difficulties were over 27 points below those of children who had not experienced such difficulties, equating to about 5 months of working memory development. The outcomes of children who had experienced social, emotional or behavioural difficulties were about 39.5 points below those of children who had not experienced such difficulties, equating to over 7 months of development.

The outcomes of children from households in the top quartile of socio-economic status were significantly higher than those of children in the bottom. The gap between the outcomes of children from the least advantaged quartile of families and those from the most advantaged was about 32 points, or about 6 months of working memory development.

Outcomes for children in single-parent homes were about 26 points higher than those of children in two-parent homes, equating to over 4.5 months of working memory development. A child’s outcomes also increased with access to more children’s books. For example, the average gap in outcomes between children with 10 books or fewer and those with between 51 and 100 was about 32 points. This roughly translates to about 6 months of working memory development.

Summary and conclusions

The self-regulation outcomes of children in Estonia are above the overall IELS mean of participating countries

The self-regulation outcomes of children in Estonia were higher than the IELS overall mean. The average inhibition outcomes in Estonia were about equal to those in the United States and higher than those in England. The average mental flexibility and working memory outcomes in Estonia were about equal to those in England and significantly higher than those in the United States.

These results suggest that five-years old children in Estonia are relatively more likely to successfully inhibit their responses when presented with a new set of information. These children are also more likely to successfully switch between rules and recall short visual sequences. This set of self-regulation skills is predictive of children’s future well-being, including how well they do at preschool and in non-academic activities where concentration and persistence correlate with success.

The self-regulation outcomes of girls, especially Russian-speaking girls, are higher than those of boys

In Estonia, the self-regulation outcomes of girls were significantly higher than those of boys across all self-regulation domains measured by IELS. Parents and educators in Estonia were also, on average, more likely to report girls rather than boys as developing above average skills. Russian-speaking children showed more prominent gender differences than Estonian-speaking children in working memory.

In the United States there were similar gaps in the inhibition and working memory outcomes of girls and boys; however, there was no difference in mental flexibility outcomes. In England, the gender gap on inhibition outcomes was reversed, with the inhibition outcomes of boys higher than those of girls. There were also no differences in the outcomes of boys and girls on mental flexibility and working memory in England.

Children who have experienced difficulties before the age of five have lower average self-regulation scores at age five

Experiencing learning difficulties earlier in life was significantly related to the self-regulation scores of five-year-olds in Estonia across all three self-regulation domains. The self-regulation scores of children who had experienced such difficulties before the age of five were significantly lower than those of children who had not. Experiencing low birth weight or premature birth was also related to the inhibition and mental flexibility skills of five-year-olds in Estonia, even after accounting for all factors in the regression models.

Experiencing learning difficulties before the age of five was a significant predictor of the self-regulation outcomes of five-year-old children, after accounting for all factors in the overall regression model. Experiencing social, emotional or behavioural difficulties early in life was also a significant predictor of a child’s working memory and mental flexibility outcomes at age five, when all factors were accounted for.

The socio-economic status of a child’s family is associated with their working memory outcomes

The working memory outcomes of five-year-olds from a household in a higher socio-economic bracket in Estonia were higher than those of children from low socio-economic backgrounds, even after accounting for all factors in the overall regression model. This implies that children from households with a lower socio-economic background are less likely to successfully recall short visual sequences than children from households with a higher socio-economic background.

The socio-economic status of a child’s household was a significant predictor of self-regulation outcomes in all participating countries – particularly in relation to mental flexibility and working memory – although the strength varied by country. Estonia had the smallest differences in children’s skills considering socio-economic status compared to England and the United States.

A child’s home learning environment is related to their self-regulation outcomes

A child’s home learning environment was predictive of their self-regulation outcomes in Estonia. The number of children’s books in their home and the frequency with which a child used a digital device, was read to and was taken to an activity outside of the home all related positively to different aspects of a child’s ability to self-regulate. Similarly, the level of parental involvement in activities taking place at the preschool was related to a boy’s mental flexibility skills.

References

[40] Anderson, P. and N. Reidy (2012), “Assessing executive function in preschoolers”, Neuropsychological Review, Vol. 22, pp. 345-360, http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ets2.12148.

[23] Ayduk, O. et al. (2000), “Regulating the interpersonal self: Strategic self-regulation for coping with rejection sensitivity.”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 79/5, pp. 776-792, https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2F0022-3514.79.5.776 (accessed on 28 June 2019).

[35] Bernier, A., S. Carlson and N. Whipple (2010), “From External Regulation to Self-Regulation: Early Parenting Precursors of Young Children’s Executive Functioning”, Child Development, Vol. 81/1, pp. 326-339, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01397.x.

[16] Best, J., P. Miller and J. Naglieri (2011), “Relations between executive function and academic achievement from ages 5 to 17 in a large, representative national sample”, Learning and Individual Differences, Vol. 21/4, pp. 327-336, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/J.LINDIF.2011.01.007.

[10] Blair, C. and R. Peters Razza (2007), “Relating Effortful Control, Executive Function, and False Belief Understanding to Emerging Math and Literacy Ability in Kindergarten”, Child Development, Vol. 78/2, pp. 647-663, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01019.x (accessed on 28 June 2019).

[5] Blair, C. and C. Raver (2015), “School Readiness and Self-Regulation: A Developmental Psychobiological Approach”, Annual Review of Psychology, Vol. 66/1, pp. 711-731, http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015221.

[34] Blair, C. and C. Raver (2012), “Individual development and evolution: Experiential canalization of self-regulation.”, Developmental Psychology, Vol. 48/3, pp. 647-657, http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0026472.

[39] Booth, A., E. Hennessy and O. Doyle (2018), “Self-Regulation: Learning Across Disciplines”, Journal of Child and Family Studies, Vol. 27, pp. 3767–3781, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1202-5.

[25] Bridgett, D. et al. (2015), “Intergenerational transmission of self-regulation: A multidisciplinary review and integrative conceptual framework.”, Psychological Bulletin, Vol. 141/3, pp. 602-654, http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0038662.

[22] Buckner, J., E. Mezzacappa and W. Beardslee (2009), “Self-Regulation and Its Relations to Adaptive Functioning in Low Income Youths”, American Journal of Olrhopsychrauy, Vol. 79/1, pp. 19-30, http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0014796.

[18] Caspi, A. et al. (1998), “Early failure in the labor market: Childhood and adolescent predictors of unemployment in the transition to adulthood”, American Sociological Review, Vol. 63/3, pp. 424-451, https://search.proquest.com/openview/a125bf198ee436749889e960111ac591/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=41945 (accessed on 28 June 2019).

[15] Clark, C., V. Pritchard and L. Woodward (2010), “Preschool executive functioning abilities predict early mathematics achievement.”, Developmental Psychology, Vol. 46/5, pp. 1176-1191, http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0019672.

[19] Daly, M. et al. (2015), “Childhood Self-Control and Unemployment Throughout the Life Span”, Psychological Science, Vol. 26/6, pp. 709-723, http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0956797615569001.

[1] Diamond, A. (2013), “Executive Functions”, Annual Review of Psychology, Vol. 64/1, pp. 135-168, http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143750.

[41] Diamond, A. and K. Lee (2011), “Interventions shown to aid executive function development in children 4 to 12 years old.”, Science, Vol. 333/6045, pp. 959-964, http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1204529.

[12] Dockett, S. (2001), “Starting School: Effective Transitions.”, Early Childhood Research & Practice, Vol. 3/2, https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED458041 (accessed on 3 July 2019).

[8] Duckworth, A., P. Quinn and E. Tsukayama (2012), “What No Child Left Behind Leaves Behind: The Roles of IQ and Self-Control in Predicting Standardized Achievement Test Scores and Report Card Grades.”, Journal of educational psychology, Vol. 104/2, pp. 439-451, http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0026280.

[24] Duckworth, A., E. Tsukayama and H. May (2010), “Establishing Causality Using Longitudinal Hierarchical Linear Modeling: An Illustration Predicting Achievement From Self-Control”, Social Psychological and Personality Science, Vol. 1/4, pp. 311-317, http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1948550609359707.

[17] Duncan, G. et al. (2007), “School Readiness and Later Achievement”, Developmental Psychology, Vol. 43/6, pp. 1428-1446, http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/[0012-1649.43.6.1428].supp.

[2] Eisenberg, N., T. Spinrad and N. Eggum (2010), “Emotion-related self-regulation and its relation to children’s maladjustment.”, Annual review of clinical psychology, Vol. 6, pp. 495-525, http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131208.

[21] Evans, G., T. Fuller-Rowell and S. Doan (2012), “Childhood Cumulative Risk and Obesity: The Mediating Role of Self-Regulatory Ability”, Pediatrics, Vol. 129/1, pp. e68-e73, http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-3647.

[31] Fuller, B. et al. (2010), “Maternal practices that influence Hispanic infants’ health and cognitive growth.”, Pediatrics, Vol. 125/2, pp. e324-32, http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-0496.

[42] Garon, N., S. Bryson and I. Smith (2008), “Executive function in preschoolers: A review using an integrative framework.”, Psychological Bulletin, Vol. 134/1, pp. 31-60, http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.134.1.31.

[32] Hackman, D. and M. Farah (2009), “Socioeconomic status and the developing brain”, Trends in Cognitive Sciences, Vol. 13/2, pp. 65-73, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/J.TICS.2008.11.003.

[37] Heatherton, T. and D. Wagner (2011), “Cognitive neuroscience of self-regulation failure”, Trends in Cognitive Sciences, Vol. 15/3, pp. 132-139, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/J.TICS.2010.12.005.

[33] Kishiyama, M. et al. (2009), “Socioeconomic Disparities Affect Prefrontal Function in Children”, Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, Vol. 21/6, pp. 1106-1115, http://dx.doi.org/10.1162/jocn.2009.21101.

[6] Mcclelland, M. et al. (2007), “Links Between Behavioral Regulation and Preschoolers’ Literacy, Vocabulary, and Math Skills”, Developmental Psychology, Vol. 43/4, pp. 947–959, http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.43.4.947.

[36] McClelland, M. et al. (2018), “Self-Regulation”, in Handbook of Life Course Health Development, Springer International Publishing, Cham, http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-47143-3_12.

[3] McClelland, M. et al. (2015), “Development and Self-Regulation”, in Handbook of Child Psychology and Developmental Science, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/9781118963418.childpsy114.

[43] McClelland, M. et al. (2010), “Self-Regulation: Integration of Cognition and Emotion”, in The Handbook of Life-Span Development, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/9780470880166.hlsd001015.

[29] McEwen, B., C. Nasca and J. Gray (2016), “Stress Effects on Neuronal Structure: Hippocampus, Amygdala, and Prefrontal Cortex.”, Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, Vol. 41/1, pp. 3-23, http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/npp.2015.171.

[20] Moffitt, T. et al. (2011), “A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth, and public safety.”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, Vol. 108/7, pp. 2693-8, http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1010076108.

[7] Morrison, F., C. Cameron and M. Mcclelland (2010), “Self-regulation and academic achievement in the transition to school”, in S. D. Calkins & M. Bell (ed.), Child development at the intersection of emotion and cognition, American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/12059-011.

[28] Nelson, C. et al. (2007), “Cognitive Recovery in Socially Deprived Young Children: The Bucharest Early Intervention Project”, Science, Vol. 318/5858, pp. 1937-1940, http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/SCIENCE.1143921.

[11] Neuenschwander, R. et al. (2012), “How do different aspects of self-regulation predict successful adaptation to school?”, Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, Vol. 113/3, pp. 353-371, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/J.JECP.2012.07.004.

[26] Noble, K., M. Norman and M. Farah (2005), “Neurocognitive correlates of socioeconomic status in kindergarten children”, Developmental Science, Vol. 8/1, pp. 74-87, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7687.2005.00394.x.

[38] Ponitz, C. et al. (2009), “A structured observation of behavioral self-regulation and its contribution to kindergarten outcomes”, Developmental Psychology, Vol. 45/3, pp. 605-619, https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Fa0015365 (accessed on 9 July 2019).

[14] Raghubar, K., M. Barnes and S. Hecht (2010), “Working memory and mathematics: A review of developmental, individual difference, and cognitive approaches”, Learning and Individual Differences, Vol. 20/2, pp. 110-122, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/J.LINDIF.2009.10.005.

[27] Raver, C., C. Blair and M. Willoughby (2013), “Poverty as a predictor of 4-year-olds’ executive function: New perspectives on models of differential susceptibility.”, Developmental Psychology, Vol. 49/2, pp. 292-304, http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0028343.

[13] Shonkoff, J., D. Phillips and N. Council (2000), Executive function in preschoolers: A review using an integrative framework., National Acadamies Press, Washington, DC, http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.134.1.31.

[9] Tangney, J., R. Baumeister and A. Boone (2004), “High Self-Control Predicts Good Adjustment, Less Pathology, Better Grades, and Interpersonal Success”, Journal of Personality, Vol. 72/2, pp. 271-324, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00263.x.

[30] Wachs, T., P. Gurkas and S. Kontos (2004), “Predictors of preschool children’s compliance behavior in early childhood classroom settings”, Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, Vol. 25/4, pp. 439-457, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/J.APPDEV.2004.06.003.

[4] Zelazo, P., C. Blair and M. Willoughby (2016), Executive Function: Implications for Education (NCER 2017-2000), National Center for Education Research, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education, http://ies.ed.gov/. (accessed on 28 June 2019).