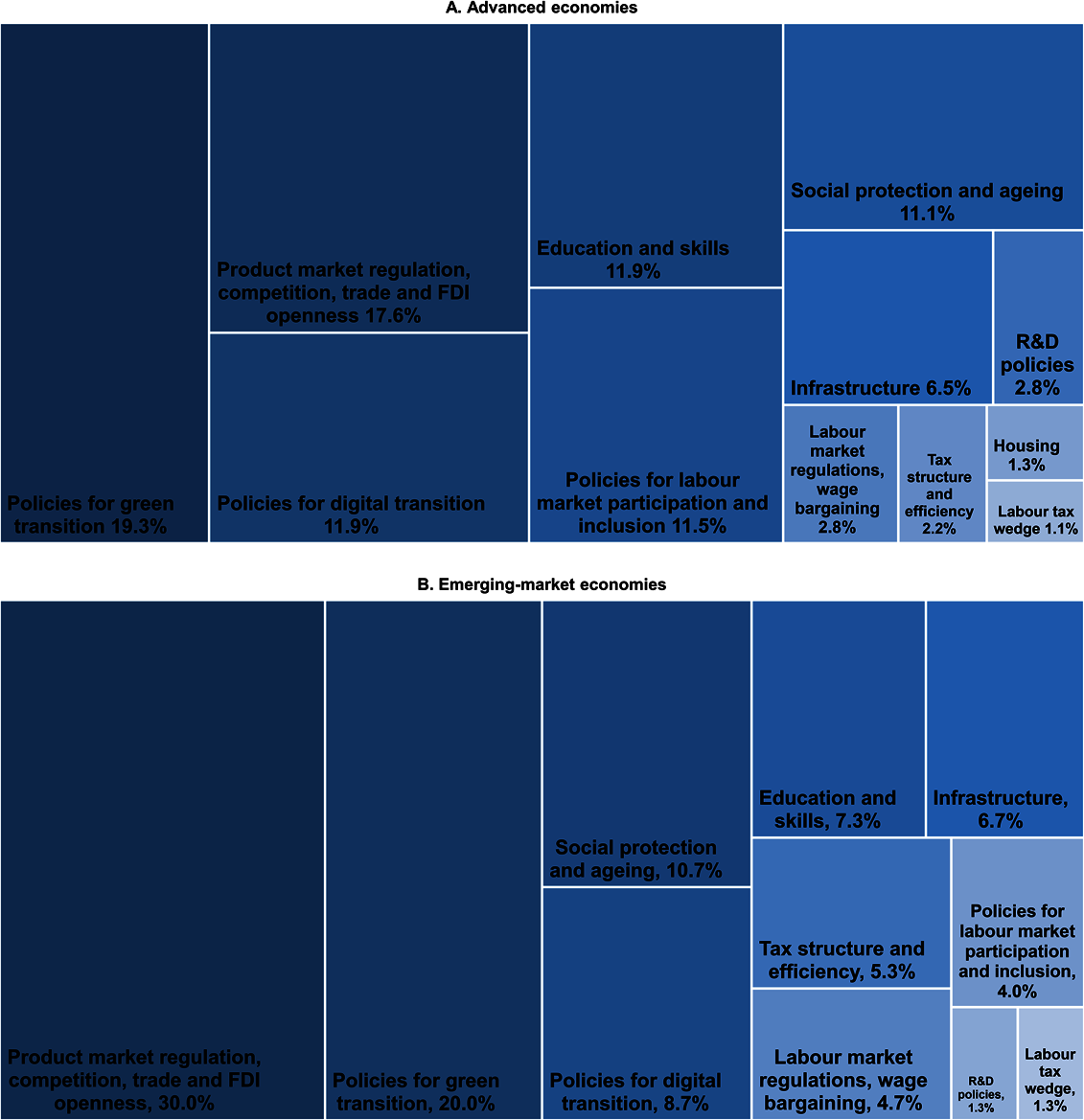

The past decade witnessed a dramatic decline in potential output growth, which primarily reflects slower trend labour productivity growth. In turn, weak productivity growth can be traced back to low investment levels and slow capital accumulation. Competition is a key area where public policies can strengthen firms’ incentives to upgrade their technologies, organisational structures, and business practices. The regulatory environment should encourage the entry of new firms and let them grow and enable unsuccessful firms to downscale or close. Insolvency regimes that do not over-penalise business failure facilitate this process. Reducing both economy-wide and sector-specific regulatory burdens, streamlining regulations, simplifying permit and licensing procedures and reducing the scope of state-owned enterprises while improving their governance, are other recommendations that could help in reviving productivity growth.

In other areas, public infrastructure investment can also act as a catalyst for private investments. The capacity and regulation of infrastructure in areas such as energy and transport could be enhanced in several countries. A sound legal framework is also critical to removing bottlenecks to growth, and a handful of OECD and non-member countries are recommended to take steps to strengthen the rule of law and judicial efficiency. Increasing public support for R&D is also warranted on a general basis, as investing in innovation involves considerable uncertainty while associated outcomes often have some public good qualities. Tax systems could also be made more growth- and equity-friendly, by shifting the tax burden towards immovable property, broadening the tax base, and reducing the fragmentation of the tax system. A shift to environmental taxation would also contribute to improving the sustainability of economic growth and wellbeing, provided measures are taken to ensure that lower-income households are not disproportionately affected.

Moreover, as knowledge remains a key driver for growth and innovation, furthering investments in education, upskilling and reskilling programs are also frequently identified recommendations. There is also a continuing need to promote labour market participation and improve work incentives, especially among vulnerable and under-represented groups. Reforms to foster inclusive and flexible labour markets, while limiting labour market dualism and incentives for early retirement, would be all essential steps in this regard. Moreover, and while progress has been achieved over the last decade, more could be done to increase female labour market participation, notably through the provision of childcare and parental leave, and improved tax incentives.

Beyond domestic borders, protectionist policies should be avoided. Globalisation has brought many benefits in terms of higher productivity, lower prices, greater variety of goods and accelerated income convergence of many emerging-market economies. However, globalisation is currently facing political headwinds, as national security and strategic considerations have gained traction, risking a more fragmented economic and political order. Chapter 2 of this edition provides new OECD material which reviews selected characteristics of trade integration via global value chains, identifies gaps in our understanding of the risks related to such chains, and outlines possible strategies to address global value chain risks. These include diversifying supply chains, friend or near shoring and inventory management, with the latter two likely to entail higher costs.