This chapter discusses the use of digital technology to engage families in early childhood education and care (ECEC) settings. The use of digital technology is widespread in ECEC settings and family contexts. The chapter discusses how digital technology can change the frequency and outreach of interactions between ECEC staff and family members, while shedding light on the challenges of doing so, to promote high-quality family and community engagement. The chapter offers some suggestions on how policy can help better prepare ECEC settings and staff to balance digital and face-to-face engagement of families for the benefit of the entire ECEC community.

Empowering Young Children in the Digital Age

6. Family and community engagement in early childhood education and care in the digital age

Abstract

Key findings

Family engagement in ECEC is a well-established practice, with clear benefits for the relationships between families and ECEC staff, staff-child interactions, and children’s development and well-being. Digital technologies offer new ways for ECEC to engage with families, but they also bring new challenges.

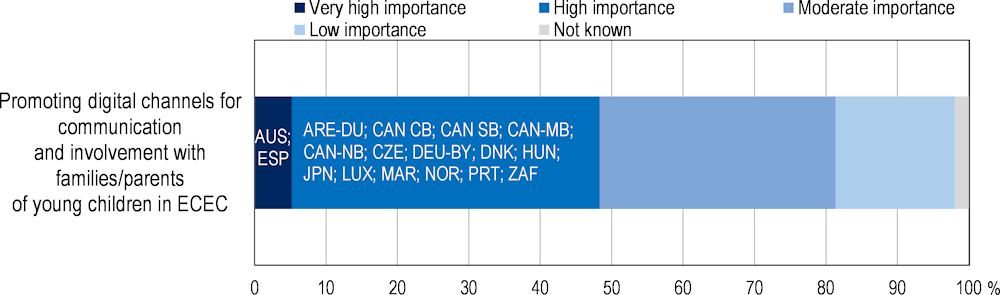

Results from the ECEC in a Digital World policy survey (2022) indicate that the majority of countries and jurisdictions find promoting digital channels for communication and involvement with families/parents of young children in ECEC a policy challenge of “high” or “moderate” importance.

On a positive note, there seems to be some evidence for the advantageous use of smartphones, apps and texts to increase real-time communication and engagement of multiple and more linguistically diverse family members, as was not possible before. The potential outreach to engage with a more diverse group of families seems promising and families seem to appreciate the flexibility offered by technology in terms of how and when they can be involved in meetings or events and decision making in ECEC.

At the same time, there is limited evidence associating the use of technology-abled engagement strategies with the quality of the interactions between ECEC staff, family members and children. Some efforts by ECEC staff to digitally engage families seem to lead to one-way forms of communication, while deeper engagement with families and parents still relies on face-to-face interactions. When using apps and other digital tools, more of the ECEC teacher’s time is spent on screen, not in face-to-face interactions with parents and children.

There is a potential risk that some types of digital communication can reduce the quality of interactions and real engagement between ECEC settings and parents. There are also concerns about teachers’ privacy and respect for personal time, particularly with texting and the use of social media. Finally, ECEC settings and staff still find using technologies challenging and unsupported, and report little pre-service training or available continuous professional development on how to establish meaningful parent-family communication and engagement through digital technologies.

Policy can help direct how to best promote family and community engagement in ECEC through digital technology.

Introduction

Family engagement in ECEC includes a variety of practices that allow for developing meaningful relationships between families and ECEC staff, which in turn can improve staff-child interactions in the settings, and children’s development and well-being. The benefits of family engagement practices also extend to the home environment, facilitating parenting and reducing the gap between the home and ECEC learning environments.

Digital technology is not the barrier for ECEC settings that it was once thought to be (Burris, 2019[1]; Murcia, Campbell and Aranda, 2018[2]), and it is now being widely adopted in early education systems (Donohue, 2016[3]). ECEC settings and teachers report using digital technologies and strategies to engage with families, irrespective of programme size (i.e. number of children enrolled), type (i.e. for-profit private, non-profit public, religious) and location (i.e. urban or rural) (Burris, 2019[1]).

Many families are now equipped with their own devices to benefit from this heightened level of engagement. The rise of mobile technologies presents novel opportunities for using technology to support family engagement and successful child development (Hall and Bierman, 2015[4]). COVID-19 has quickened the pace of digitalisation in ECEC settings and practices, and further changed expectations. Settings and families learnt in dramatic ways the importance of collaborating to support child development and well‑being while not being able to rely on face-to-face contact (Charania, 2021[5]). Many settings had to suddenly create new communication strategies with families but, given existing digital divides, not all families and children were able to benefit from these new digital communication strategies.

This chapter reviews the potential and challenges of using digital technology to engage families in ECEC settings. It starts by setting the scene on the prevalence of digital technologies in home environments. It then discusses how technology can change the frequency, outreach and quality of interactions between ECEC staff and family members. The question is not anymore about stopping the use of technology in ECEC, but there is a need to better understand how such practices actually contribute to process quality and children’s development and well-being. The chapter concludes with some policy pointers.

The changing landscape of the use of digital technology in home environments

Children today live in media-rich households with access to a variety of different devices and digital technologies that are a central part of their everyday lives (see, for example, OECD (2019[6]); Kapella, Schmidt and Vogl (2022[7])). Young children are using digital technologies in home environments with increasing frequency and intensity, for many different activities, and often in combination with or under the supervision of their parents. Parental surveys provide evidence that, over the last decade, for a large share of young children, their initiation using digital devices and online activities has been occurring earlier than before, and well before age 6 (see Chapter 2).

Digital technologies in the home environment and their role in family interactions

Digital technologies have become common tools for mediating family interactions. A recent study of parental mediation strategies integrating digital technology demonstrated that digital technologies can contribute to “doing family” in several dimensions. Using four country case studies (Austria, Estonia, Norway and Romania), Kapella, Schmidt and Vogl (2022[7]) demonstrated how experiencing digital technologies actively together within the family can shape family identity and create a feeling of “we-ness”, and co-use of digital technology can also serve as a springboard for conversations regarding (sensitive) topics and strengthen children’s resilience. Parents, for example, can function as positive role models, guides and supervisors of online activities, home teachers and filters of content that should not reach the child. Digital technology can also support the family care aspect, for example by obtaining and maintaining digital and media competences and supporting others’ well-being, staying in contact and connected with each other, and contributing to a feeling of security and being cared for beyond face-to-face interactions. These aspects become especially true for transnational families or families with members that are not co‑present (Kapella, Schmidt and Vogl, 2022[7]).

However, there are differences across and within countries in terms of families’ access to digital devices and the Internet, as not all families and children have access (Ayllón, Holmarsdottir and Lado, 2021[8]). Moreover, parents are challenged with the mediation of digital technologies, since they require a certain level of know-how, while the rapid development of digital technology demands that parents constantly adapt to new situations, information, new devices, etc. (Kapella, Schmidt and Vogl, 2022[7]). Finally, digital technologies can contribute to exacerbating the vulnerability of children or to the emergence of new vulnerabilities, for example, through children’s lack of digital competences, overprotection of parents, children as the main instructors and mediators on digital technology in the family, exposure to specific content or experiences, and exclusion of the child by other family members during their digital activities.

A changed landscape of expectations regarding the use of digital technology with and by children in post-pandemic times

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many countries implemented nationwide restrictions to slow the spread of the virus. These restrictions included the closure of ECEC centres and all other education services for children, the prohibition of visiting playgrounds, and strict social distancing measures, e.g. no contact with more than one person from outside one’s household. Emergency childcare was only available to a small number of families in relevant occupations.

This created a challenging situation for families with young children (Andresen et al., 2020[9]; Huebener et al., 2021[10]). Children stayed at home all day and parents had to provide early education and care while simultaneously having to meet all other demands, e.g. employment, household tasks. Some parents found it enriching to be able to spend more time with their child/children, while others experienced intense stress caused by the difficulty balancing work and family during confinement (Cohen, Oppermann and Anders, 2020[11]). Concerns about potential health risks and infection were a further burden and source of stress.

To handle these many demands, many families had to resort to digital technology to maintain their jobs. Parents and family members suddenly became role models for work practices in home office situations, normalising large amounts of (adult) screen time often under considerable stress, and with little or no training for this sharp transition. There is evidence of increases in children’s screen time during the COVID-19 pandemic (see Chapter 2). At the same time, parents suddenly felt in charge of the majority of their children’s learning activities. A study in Germany during the first lockdown in 2020 demonstrated that parents engaged, on average, in more home learning activities with their children during the lockdown, compared to before the lockdown. However, whereas most parents offered more home learning activities, some of the very stressed parents offered fewer home learning activities than before the lockdown (Oppermann et al., 2021[12]).

Engaging parents and families in early childhood education and care through digital technologies

Research has shown that parental engagement, especially when it ensures high-quality learning for children at home and good communication with ECEC staff, is strongly associated with children’s later academic success, socio-emotional development and adaptation in society (OECD, 2011[13]; 2019[14]; Sylva et al., 2004[15]). One purpose for ECEC staff to engage with parents is to raise parents’ awareness of the importance of activities in the centre, get their support for what is happening, and ensure that families and children develop good feelings about early education. These engagement initiatives can help improve the child’s interactions with adults inside the playroom, classroom or setting.

Practices that engage families and guardians in ECEC centres are well-established, and these include exchanging information with parents regarding daily activities and children’s development and well‑being, as well as encouraging parents to play and carry out learning activities at home with their children. Several examples of effective ECEC services that promote parental engagement (such as Head Start, the Perry Preschool and the Chicago Parent Centers in the United States) offer evidence that parental engagement matters (Bennett, 2008[16]).

Digital technologies offer new ways for ECEC to engage with families, but also bring new challenges. The ECEC in a Digital World policy survey (2022) asked countries about the important policy challenges regarding digitalisation and young children generally and digitalisation and ECEC specifically. Despite the potential for digital technologies to be a positive force in engaging parents, promoting digital channels for communication and involvement with families/parents of young children in ECEC as a policy challenge was rated as being of “high” or “moderate” importance by most countries and jurisdictions that responded to the survey (Figure 6.1).

Figure 6.1. Policy challenges related to family engagement in early childhood education and care

Notes: Responses are weighted so that the overall weight of reported responses for each country equals one. See Annex A.

The response category “very high importance” was limited to three out of ten response items maximum.

CAN CB: centre-based sector in Canada. CAN SB: school-based sector in Canada. CAN-MB: kindergarten sector only in Canada (Manitoba).

Source: OECD (2022[17]), ECEC in a Digital World policy survey, Table B.2.

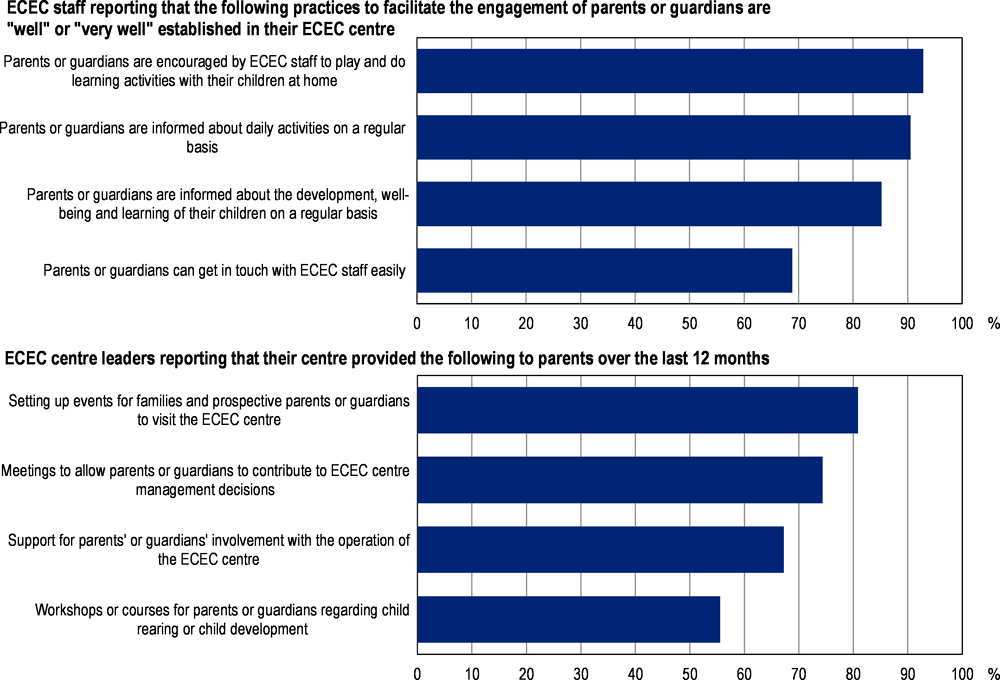

Common practices and levels of engagement

The OECD international survey of the ECEC workforce (TALIS Starting Strong) asked staff in 2018 (before the COVID-19 pandemic) to indicate the extent to which a number of practices to engage parents or guardians were well-established in their centre (OECD, 2019[14]). These family engagement practices included informal options for parents to easily contact staff, options to be informed on a regular basis about children’s daily activities or their development, as well as more active forms of engagement, such as encouraging parents or guardians to do play and learning activities with their children. On average across countries participating in TALIS Starting Strong 2018, very high percentages of ECEC staff in pre-primary education centres reported that practices to engage with parents or guardians were well-established in their centres, particularly opportunities to get in touch with staff. Moreover, across countries a high percentage of ECEC staff reported that, in their centre, parents were informed about their children’s development, learning and well-being, as well as about their daily activities. Interactions between staff and parents or guardians can also facilitate family involvement in ECEC events and inform parenting practices at home. On average across countries, a large percentage of staff (albeit smaller than for other activities) reported that they encouraged parenting activities, such as doing play and learning activities with their children at home (Figure 6.2).

Figure 6.2. Practices to promote family engagement in early childhood education and care settings

Note: Staff include centre leaders, teachers, assistants or any other unspecified staff groups.

Centre leader refers to the person with the most responsibility for the administrative, managerial and/or pedagogical leadership at the ECEC centre.

Items are sorted in descending order of the cross-country average percentage of respondents selecting each option.

Source: OECD (2019[18]), TALIS Starting Strong 2018 Database; OECD (2019[14]), Tables D.2.3 and D.2.4, https://www.oecd.org/education/school/oecdtalisstartingstrongdata.htm (accessed on 10 December 2022).

TALIS Starting Strong 2018 also asked ECEC leaders to report on whether some concrete activities were offered to parents or guardians to facilitate their engagement in the centre during the 12 months prior to the survey. On average across participating countries, a large percentage of leaders of pre-primary education centres reported setting up events for families and prospective parents or guardians to visit the centre, and setting up meetings to allow parents or guardians to contribute to management decisions. Workshops or courses regarding child-rearing or child development, which can influence interactions between children and parents, were less common (Figure 6.2). In general, the patterns observed in staff’s and centre leaders’ responses followed the same direction. Parents were frequently in contact with staff to learn about the centre, but activities aiming to help parents in their interactions with children were less widespread.

Changing ECEC approaches to the use of technology during the pandemic

The day-to-day work of ECEC settings and staff was significantly affected due to the closure of settings during the pandemic. Many settings had to suddenly create new communication strategies with families. In the OECD G20 study about how digital technology was used for maintaining education for young children in 2020, countries reported that digital communication took on a major role in maintaining relationships between parents and teachers at the primary level, but also at the pre-primary level (OECD, 2021[19]).

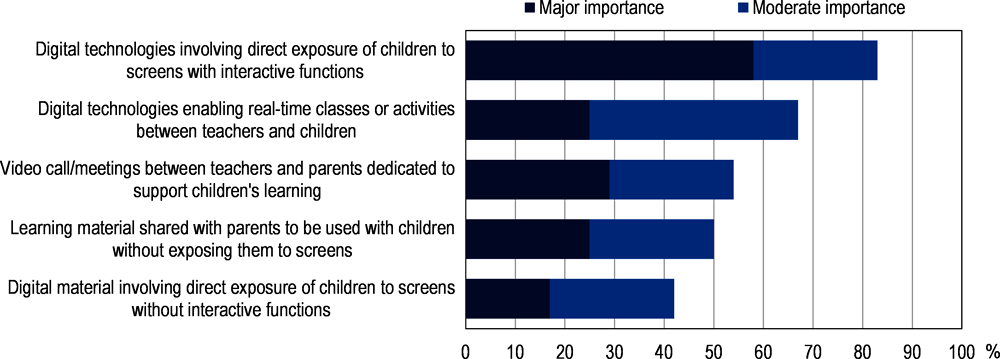

Prior to the pandemic, digital technologies were more commonly used as communication rather than pedagogical tools, with wide variation across countries in the extent to which digital tools were integrated into teaching practices. COVID-19 accelerated the pace of digitalisation in ECEC settings, and further changed expectations regarding the use of technologies with and by children. Settings and families learnt in dramatic ways the importance of collaborating to support child development and well-being while not being able to rely on face-to-face contact (Charania, 2021[5]). About three-quarters of the countries participating in the OECD survey on the use of digital technologies in ECEC during the pandemic reported that the main responsibility for organising educational programmes stayed with the schools and centres, even when children were at home in lockdown. Having teachers digitally share educational materials with parents and family members was reported to be of major importance by 60% of the participating countries (OECD, 2021[19]). Of note that, in the majority of countries, at the pre-primary education level the educational materials shared with parents did not require exposing children to screen time (Figure 6.3), and the estimated amount of time children were expected to be interacting with digital technology was generally low (i.e. less than an hour per day for the pre-primary level (OECD, 2021[19])).

Figure 6.3. Digital resources used for maintaining continuity of education for young children during the COVID‑19 pandemic

Note: Items are sorted in descending order by the share of countries selecting the response categories “major” or “moderate” importance.

Source: OECD Survey on Distance Education for Young Children; OECD (2021[19]).

Using digital technologies to strengthen family engagement in support of process quality

While many of the traditional frameworks of parent/family engagement in ECEC are based on face‑to‑face interactions (Epstein et al., 2005[20]), there are more and more examples of technology being used by ECEC teachers and settings to promote family engagement. This is increasingly common since the rapid growth in the use of smartphones. The COVID-19 pandemic is likely to have accelerated this trend.

In complement to the common methods of send-home newsletters and sometimes handwritten materials (such as notes or journals), digital technologies allow for more immediate communication, may be a less time-consuming method of sharing information and provide documentation over time. For example, applications allow ECEC staff to share photos, videos and notes with parents throughout the day, while the child is attending ECEC. Apps also allow teachers to record meals, activities and naptimes (Burris, 2019[1]). These communication strategies help parents stay informed of the day-to-day activities at the ECEC setting and feel more connected to their child while at work. At the same time, there is a concern that the time teachers spend on screens recording and reporting activities of the day may mean they have less time for face-to-face interactions between ECEC staff and children or ECEC staff and parents.

The ECEC in a Digital World policy survey (2022) asked participating countries and jurisdictions to indicate how common communication strategies were with parents/families through digital technologies in ECEC centres. Overall, countries seem to adopt a careful approach to technology use for information. In approximately 60% of participating countries or jurisdictions, it is estimated that at least two-thirds of centres for children ages 0-5 (or 3-5) use technology, such as websites, messages and notifications, to keep parents informed on general topics and for administrative purposes (Table 6.1).

Technology is also now being used to bridge the gap between the home and the ECEC learning environment. Some applications allow teachers to share an image of a child’s artwork or a video of a child taking their first steps at school, making children’s learning visual and accessible (Oke, Butler and O’Neill, 2021[21]). Families can view the child’s portfolio and review and download images, videos and alerts, ultimately changing how they perceive the work developed at the setting, their child’s development and their own potential involvement. In one US study, photo collages annotated with meaningful explanations of children’s play were emailed to parents daily. Parents receiving emails showed increased knowledge of child development, a better understanding of learning through play and an increased understanding of what was happening in the ECEC setting (Bacigalupa, 2015[22]).

In New Zealand, portfolios for documenting children’s learning are now being replaced by online ePortfolios (Goodman and Cherrington, 2015[23]). In one study of ePortfolios, parents reported that deeper conversations with children about learning, and furthering learning in the home, were a result of the inclusion of videos in the online version of the portfolios. Furthermore, teachers using ePortfolios described stronger relationships with parents (Hooker, 2019[24]). The use of digital platforms for making portfolios of children’s work/activities available to parents/families is generally reported for a third or fewer centres for children ages 0-5 (or 3-5) in countries and jurisdictions participating in the ECEC in a Digital World policy survey (2022). In the Czech Republic, Korea, the Slovak Republic, Spain and Switzerland, the majority of centres are reported to be implementing a wide variety of parent/family engagement strategies using digital tools, including the use of technology for educational purposes (Table 6.1).

ECEC staff also have the ability, supported by technology, to prepare and share lesson plans; take attendance; and convene and review important information about a child’s allergies, medical information and guardians. Families can inform the teacher if their child will be away due to illness or vacation, or update information that is otherwise time-sensitive. The benefits of family engagement through technology are true for “real-time” technology, but also for asynchronous tools that do not require teachers and parents to be logged in, or online, using an application at the same time. ECEC programmes have reported using these in-the-moment technologies, such as texting and applications with photos, in tandem with other tools, such as email, because it affords for a more individualised approach (Burris, 2019[1]).

Table 6.1. Communication with families through digital technologies in early childhood education and care settings

Estimated share of settings where the following resources and practices are available, by country or jurisdiction, 2022

|

Websites where general information about the centre/setting is posted for parents/families |

Possibilities for parents to contact/exchange with centre leaders using digital tools |

Possibilities for parents to contact/exchange with staff members using digital tools |

Messages or notifications to parents/families for administrative purposes |

Messages or notifications to parents/families for educational purposes |

Sharing of educational materials with parents/families through digital channels |

Digital platforms making portfolios of children's work/activities available to parents/families |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Australia |

Age 0 to 5 |

|||||||

|

Australia (Tasmania) |

||||||||

|

Belgium (Flanders PP) |

Age 3 to 5 |

|||||||

|

Belgium (Flanders U3: centre-based) |

Age 0 to 2 |

|||||||

|

Belgium (Flanders U3: home-based) |

Age 0 to 2 |

|||||||

|

Canada CB |

Age 0 to 5 |

m |

m |

|||||

|

Canada SB |

Age 3 to 5 |

m |

m |

|||||

|

Canada (Alberta: Day care) |

Age 0 to 5 |

|||||||

|

Canada (Alberta: Preschool) |

Age 3 to 5 |

|||||||

|

Canada (Alberta: Family day home) |

Age 0 to 5 |

|||||||

|

Canada (British Columbia) |

Age 0 to 5 |

|||||||

|

Canada (Manitoba¹) |

Age 3 to 5 |

|||||||

|

Canada (New Brunswick) |

Age 0 to 5 |

|||||||

|

Canada (Quebec) |

Age 0 to 5 |

|||||||

|

Czech Republic |

Age 3 to 5 |

|||||||

|

Denmark: Local-authority childminding |

Age 0 to 2 |

|||||||

|

Denmark: Private childminding |

Age 0 to 2 |

|||||||

|

Denmark: Local-authority day care centre |

Age 0 to 5 |

|||||||

|

Finland: Early Education centre |

Age 0 to 5 |

|||||||

|

Finland: Family day care |

Age 0 to 5 |

|||||||

|

France |

Age 3 to 5 |

|||||||

|

Germany |

Age 0 to 5 |

|||||||

|

Germany (Bavaria) |

Age 0 to 5 |

|||||||

|

Hungary |

Age 3 to 5 |

|||||||

|

Iceland |

Age 0 to 5 |

|||||||

|

Ireland |

Age 0 to 5 |

|||||||

|

Israel |

Age 3 to 5 |

|||||||

|

Italy |

Age 3 to 5 |

|||||||

|

Japan: Kindergarten |

Age 3 to 5 |

|||||||

|

Japan: Day care centre |

Age 0 to 5 |

|||||||

|

Luxembourg |

Age 3 to 5 |

|||||||

|

Morocco |

Age 3 to 5 |

|||||||

|

Norway |

Age 0 to 5 |

|||||||

|

Portugal |

Age 3 to 5 |

|||||||

|

Republic of South Africa |

Age 0 to 5 |

|||||||

|

Slovak Republic |

Age 3 to 5 |

|||||||

|

Slovenia |

Age 0 to 5 |

|||||||

|

South Korea |

Age 3 to 5 |

|||||||

|

Spain |

Age 3 to 5 |

|||||||

|

Sweden |

Age 0 to 5 |

|||||||

|

Switzerland |

Age 3 to 5 |

|||||||

|

United Arab Emirates (Dubai) |

Age 0 to 5 |

Notes: This question relates to periods when the opening of ECEC settings is not disrupted by special circumstances like the COVID-19 pandemic or other events leading to closures of premises.

Belgium (Flanders PP): pre-primary education in Belgium (Flanders). Belgium (Flanders U3): ECEC for children under age 3 in Belgium (Flanders). Canada CB: Centre-based sector in Canada. Canada SB: School-based sector in Canada. Canada (Manitoba): Kindergarten sector only in Canada (Manitoba).

In more than 66% of settings

In more than 66% of settings

Between 34% and 66% of settings

Between 34% and 66% of settings

In 33% of settings or less

In 33% of settings or less

Not known

Not known

m: Missing

Source: OECD (2022[17]), ECEC in a Digital World policy survey, Tables B.15, B.16 and B17.

Using digital technologies to engage a greater share of families

Using text messaging allows for an even more direct form of communication and, of all available technologies, texting can reach the biggest share of families, even among poor communities (Snell, Wasik and Hindman, 2022[25]). Surveys in the United States suggest that the Millennial generation (a group well-represented as parents in early childhood programmes) prefers texting as a form of communication over phone calls and email (Newport, 2014[26]). In a study of a texting approach to family engagement – Text to talk – Snell, Wasik and Hindman (2022[25]) reported that families overwhelmingly supported the use of texting as a preferred form of communication, while teachers reported how using texting built warm and engaged relationships with families. Due to the ease, accessibility and low (or no) cost of texting, messages were sent and shared across many family members almost immediately, offering a bridge between the many family members participating in the child’s life (e.g. the one dropping the child off, the one picking the child up and the one where the child spent occasional nights).

There are, nevertheless, concerns surrounding the use of texting between teachers and parents. Some teachers may not feel comfortable using their own private phone to communicate with parents, or with sharing children’s information in such concise segments of information to be contained in a text message. Moreover, there is perhaps more risk of inappropriate messaging from parents to staff than in face-to-face interactions, and possible effects on teacher stress of receiving such messages in written format and at all possible hours of the day. To address some of the concerns with teachers’ privacy and respect for personal time, digital service providers have developed services to allow teachers to text families privately and securely without using their own personal mobile phone number, making texting more practical and safer (Snell, Wasik and Hindman, 2022[25]). Some of the other concerns remain unaddressed.

One of the commonly reported advantages of using digital technologies in ECEC family engagement is the outreach to multiple and more diverse family members. This is important because previous studies had demonstrated that ECEC staff and leadership may have clear strategies and goals for creating a welcoming atmosphere for parents and children, but still they may fail to engage parents and guardians of children from families of diverse backgrounds (Crozier and Davies, 2007[27]). The outreach benefit of technology use is reported for texting, but also for a variety of other forms of technology (Burris, 2019[1]; Hooker, 2019[24]; Oke, Butler and O’Neill, 2021[21]; Snell, Wasik and Hindman, 2022[25]). By using technology to share pictures, updates and notes with families, ECEC teachers are able to reach out to family members even in cases where children do not live with both parents, have parents or family members who are away or travel for work, furthering the relationship between ECEC settings and family, and avoiding gaps in information with relevant family members. In one study in Ireland, the use of a cloud‑based early childhood management and parental communication application allowed ECEC settings to overcome common communication barriers with families from diverse backgrounds who have limited time, employment obligations and varying expectations for their child’s ECEC (Oke, Butler and O’Neill, 2021[21]). The type of personalised information that this cloud-based application allowed ECEC teachers to share with families built confidence between them, particularly when at least one member of the child’s family was unable to attend face-to-face meetings. Language barriers are also more easily addressed with technology, as families can translate messages received using services on their phone or teachers can use automatic translation services to translate before sending the message (Snell, Wasik and Hindman, 2022[25]).

Using digital technologies to promote positive parenting through ECEC

Family engagement in ECEC can help improve teacher-child interactions inside playrooms, classrooms or settings; it can also promote positive parenting at home. Traditionally, ECEC staff would rely on drop-off and pick-up times, in addition to occasional parent‑teacher meetings, to offer families suggestions of learning support activities to be developed at home. Using digital technologies in ECEC offers more opportunities to promote positive parenting by offering online links to resources, and access to social media groups and conferencing options to facilitate conversations, complementing the traditional referral to parenting books and flyers. In the ECEC in a Digital World policy survey (2022), using technology for educational purposes, for example by using messages or notifications to parents/families, or sharing educational materials with parents/families through digital channels is limited to a smaller share of centres in participating countries and jurisdictions; less than 20% of participating countries or jurisdictions report this communication practice for at least two‑thirds of centres for children ages 0-5 (or 3-5).

Evidence surrounding texting interventions for parenting shows promising results. In a US study about Head Start, parents from socio-economically disadvantaged backgrounds who received parenting tips via text message – Parent University – engaged in more learning activities at home, such as reading to children, teaching letters and/or words, talking while running errands, playing counting games, singing songs, etc. The impact of the intervention was particularly significant for fathers, who are often excluded from ECEC communication and participation, and parents of boys (Hurwitz et al., 2015[28]). Other experimental studies of texting in parenting interventions (outside or in parallel to the ECEC context) have also demonstrated significant increases in the quantity and quality of time spent by parents practising skills with preschoolers and younger children (Cortes et al., 2021[29]; Doss et al., 2019[30]; Hurwitz et al., 2015[28]; Mayer et al., 2019[31]; Meuwissen et al., 2017[32]; York and Loeb, 2014[33]). Results varied according to children’s pre-intervention literacy skills (Cortes et al., 2021[29]), whether text messages were personalised (Doss et al., 2019[30]), and whether parents perceived their investment in their children as having an impact in their future skills (Mayer et al., 2019[31]).

It is important to note that the scientific evidence around the benefits of texting, albeit hopeful and rigorous, is restricted to texting interventions developed by programmes outside of ECEC, or in collaboration with ECEC settings, but not exactly implemented by ECEC teachers or other staff. More evidence is necessary regarding the benefits and tensions of the use of texting, as well as of other forms of digital communication such as social media, by ECEC teachers, as part of their day-to-day practice. Using digital communication may change aspects of the teacher-parent relationship in unexpected ways. One study reported that parents receiving more information in the texts seemed to visit their children’s centre less often (Doss et al., 2019[30]). In a systematic review of teacher-student communication through social networks in higher levels of education, the use of social media platforms for communication with students seemed to decrease teacher-perceived credibility (Froment, García González and Bohorquez, 2017[34]).

Using digital technologies to encourage family involvement in ECEC setting activities

Technology is also used in ECEC settings to facilitate parent participation and volunteering in ECEC activities. Organising parent help and support in on-site and community events now requires fewer in-person meetings, which posed strains on available space in settings and limited participation for busy families. Through email and online surveys, teachers and ECEC leaders can quickly gather data on the availability and interest in events, projects and initiatives that require parent support (Burris, 2019[1]).

Technology can also support parents’ decision making, which is a central feature of family involvement (Epstein et al., 2005[20]). Traditionally, parents took important decisions during face-to-face meetings of parent-teacher organisations and parent advisory boards. Such decisions are often built upon regulations and handbooks provided and available at the ECEC settings during working hours. However, some families tended to be underrepresented in these committees because of limited availability due to multiple jobs, odd work hours, other family responsibilities and other time restrictions (Burris, 2019[1]). Technology, particularly online conferencing tools, now allows busy families to participate in decision making at hours most fitted to their schedule. Additionally, regulatory documents are now available online, making it easier for parents to be and stay informed. Nevertheless, existing digital divides between families may still limit access to these benefits of technology in decision making (see Chapter 7).

Challenges in family involvement through digital technology

ECEC settings use technology to facilitate involvement and communicate with families, but in some cases these engagement efforts may lead to one-way forms of communication (Burris, 2019[1]), where families are informed rather than involved in collaborative relationships around children’s development. This trend is somewhat reflected in the answers to the OECD ECEC in a Digital World policy survey (2022) by participating countries or jurisdictions. Possibilities for parents to contact/exchange with centre leaders or staff members using digital tools are less common than opportunities for centres to communicate with parents; approximately 45% of participating countries or jurisdictions report this communication practice for two-thirds of centres for children ages 0-5 (or 3-5).

Moreover, technology support of parents and families’ decision making is often the least reported use of technology by ECEC teachers (Burris, 2019[1]). Although there is great potential in using technology to engage with more and more diverse families, better evidence is needed on how often digital technologies are used beyond routine communication on administrative matters and how they actually improve engagement. When surveying ECEC teachers and parents in a texting intervention, both groups reported that most texts were dedicated to logistical issues (Snell, Wasik and Hindman, 2022[25]). These challenges were confirmed by countries and jurisdictions participating in the ECEC in a Digital World policy survey (2022), where possibilities for parents to contact/exchange with centre leaders or staff members using digital tools seem to be less common in centres than the use of technology in ECEC settings to send general information to parents.

The ECEC workforce still finds using technologies challenging. The topic of establishing mechanisms for meaningful parent-family communication and engagement through technology was often absent from the training of future teachers (Merkley et al., 2006[35]), including ECEC teachers, a couple of years ago and seems to now be commonly included in programmes of a small majority of countries and jurisdictions participating in the ECEC in a Digital World policy survey (2022) (see Chapter 5). Younger ECEC staff – out of college – tend to be more skilled and comfortable using smartphones and applications, and use these technologies more often to engage families. However, there is a higher degree of turnover in these staff (Burris, 2019[1]).

Despite gaps in ECEC staff digital competencies, teachers with access to technology are increasingly using social media, text messaging, email and educational applications to engage with families. While evidence does not point towards the need to discourage these practices, there is a need to better understand how these technologies are being used to engage families (Reedy and McGrath, 2010[36]), and how such practices actually contribute to process quality and children’s development and well-being.

There is also a potential risk that some types of digital communication can reduce the quality of interaction and real engagement between ECEC settings and parents. In some contexts, patterns of digital communication that developed during the COVID-19 restrictions remained in place after the restrictions were withdrawn, and in some cases, parents are still not being encouraged into settings to meet with ECEC staff face-to-face. There is a risk that ECEC centres may use digital communication tools because they are easier rather than because they are better.

These obstacles to the adequate use of technology by ECEC teachers and settings to promote family engagement offer reasons for concern in favour of a careful and supervised approach to digital communication in ECEC settings. Countries find it a challenge to promote such approaches. Even when all digital technology obstacles to family engagement are addressed in ECEC settings, existing digital divides between families may still limit access to these benefits of technology in decision making by families (see Chapter 7). Families from socio-economically disadvantaged backgrounds and families with children whose first language is different from the language(s) used in the ECEC centre may face a variety of economic and social stressors, such as the need to hold multiple jobs, limited control over work schedules or unstable housing, all of which may limit the time and resources parents may have to regularly devote to promoting children’s learning at home (Hurwitz et al., 2015[28]).

Digital technologies for communication and partnerships with communities and other actors

Involving and empowering parents or guardians as caregivers and educators of their children may require collaboration with other stakeholders, such as family support, social work and health services (Sim et al., 2019[37]). Community engagement can help connect families and ECEC services, as well as other services for children. Different services, such as formal ECEC services, day-care, health services and other child services, can work together to create a continuum of services that is reassuring for parents and can meet the needs of young children (OECD, 2011[13]).

Digital technologies may offer support for establishing and/or maintaining successful partnerships between ECEC centres and other schools, often softening transitions for ECEC children within pre-primary and to primary education. For instance, in Japan, collaboration between ECEC settings and elementary schools in the district of Minami Matsuo Hatsugano Gakuen was made difficult by the COVID-19 pandemic. To address these obstacles, casual online exchanges between leaders of integrated ECEC centres, nurseries and elementary schools were held once a month. As a result of these meetings, junior high school students demonstrated interest in engaging in “childcare training” of preschoolers through digital communication. In this “childcare training”, high school students shared with preschoolers quizzes, picture-story shows, storytelling and origami classes online. After the online “childcare training” took place, ECEC and other local educational communities maintained casual exchanges among children through digital technologies, for example to address questions from anxious preschoolers preparing to enter elementary school resources (see Case Study JPN_1 – Annex C).

Fostering digital skills and incorporating digital technology in ECEC settings can also help establish stronger connections with members of the community beyond educational settings. At higher levels of education, schools that are successful in using technology effectively establish strong partnerships with key stakeholders from universities, technology companies and other organisations (Levin and Schrum, 2013[38]; Burns and Gottschalk, 2019[39]). In ECEC settings, digital technology may offer families access to other resources through the ECEC setting and staff, such as digital resources and museums, promising childhood intervention programmes (e.g. in bullying), parenting training, etc.

ECEC staff may also help promote early digital literacy by inviting families to use online tools to extend knowledge and competencies acquired in the class or playroom. For instance, in Germany, to encourage language development and reading proficiency, the Federal Ministry for Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth provided funding for the implementation of the lesenmit.app initiative developed by the reading foundation Stiftung Lesen. The initiative offered families an overview of the apps available for promoting language and reading development, and also classified the available applications in regard to their pedagogical value, empowering families to read more and use better digital resources (see Case Study DEU – Annex C). Promoting early digital literacy through online tools may be a good complement to more traditional approaches of inviting families into the early learning environment, offering a lending library, sharing what the children are doing in the learning environment and making community connections.

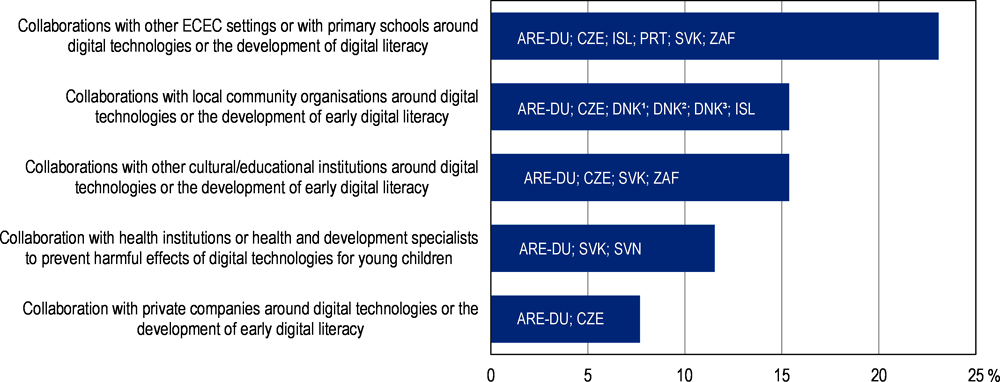

Despite these advances, the potential brought by digital technologies to expand connections with other institutions, schools, higher education institutions and agencies providing services to children, and their families seems under-tapped. ECEC staff and centre leaders report minimal technical assistance in using technology in their practice. In related OECD work, countries reported a low rate of partnerships between schools and programmers and digital experts despite the growing emphasis on equipping teachers with digital competences (Burns and Gottschalk, 2020[40]).

This trend is reflected in the answers to the ECEC in a Digital World policy survey (2022) by participating countries and jurisdictions regarding the frequency of partnerships and collaborations between ECEC settings and external actors around digital technologies (Figure 6.4). Only in a small number of countries and jurisdictions does collaboration using digital technologies with local partners, such as other ECEC settings, schools, cultural institutions, local community organisations, private companies, and health and development specialists, happen in at least a third of centres. In striking comparison, in the Czech Republic, the majority of centres are reported to implement a wide variety of strategies for collaboration and partnership with external actors of various sectors and types.

Figure 6.4. Partnerships between early childhood education and care settings and external actors about digital technologies

Note: Responses are weighted so that the overall weight of reported responses for each country equals one. Some countries and jurisdictions responded for multiple settings and therefore appear more than once with the same country and jurisdiction code. See Annex A.

DNK1: Local-authority childminding in Denmark. DNK2: Private childminding in Denmark. DNK3: Local-authority day care centre in Denmark.

Items are sorted in ascending order of the share of countries selecting each option.

Source: OECD (2022[17]), ECEC in a Digital World policy survey, Table B.21.

Policy pointers

Debating whether or not ECEC teachers and settings should be using technology to engage and communicate with parents, families and communities no longer seems worthwhile or practical. The use of digital technology is widespread in settings and family contexts. Policy can help direct how best to promote family and community engagement in ECEC through digital technology.

Policy pointer 1: Document and understand how digital technology can contribute to higher quality family and parent engagement

Policy can emphasise the importance of documenting by ECEC staff and leaders the process by which digital technology actually promotes high-quality approaches in family and community engagement.

Efforts should be extended to better understand the essential conditions by which digital engagement can actually benefit children. Efforts can be put on identifying the necessary time needed for staff to engage with families through digital technologies, the types of digital technologies that can be preferred for certain goals as well as the conditions to reach all families, and the specific conditions needed to reach families that are being excluded by other forms of traditional communication and engagement.

Research and documentation of practices on how information is provided and conveyed to, received by and accepted by/from families of children in ECEC are also needed, while bearing in mind existing digital divides. In countries with digital divides (in access) related to geographical areas or parents’ socio-economic background, using digital technology for communication with parents can exacerbate inequalities.

Policy pointer 2: Balance traditional, face-to-face forms of parental engagement with digital approaches

Because digital communication offers a faster and easier form of communication with parents, patterns of digital communication that developed during COVID-19 restrictions have, to some degree, remained in place after the restrictions were withdrawn and, in some cases, parents are still not being encouraged into settings to meet with ECEC staff face-to-face. Policy can underscore a more balanced approach to parent engagement, combining traditional face-to-face forms of parental engagement with digital approaches.

Policy can influence the engagement of ECEC staff and parents by incorporating this balancing aspect in curriculum frameworks and other policy levers and by continuing to encourage face-to-face communication with parents to offer opportunities for in-depth conversations, handle difficult topics and promote parental involvement in decision making.

There could be training on the respective advantages and drawbacks of face-to-face and digital modes of communication and encouragement to use digital technologies to expand, not replace, face-to-face communication unless this is clearly not needed. Consideration can be given to preparing staff to carefully and meaningfully use digital technologies for broader parental engagement, including concerning children’s learning, development and well-being, beyond simple information communication.

Policy pointer 3: Prepare ECEC staff and settings to maximise the potential of digital technologies for community engagement

Policy can direct resources to adequately prepare ECEC staff and settings to maximise the potential of using digital technologies to engage with communities, which seems under-tapped at the moment.

To maximise the benefits of the use and application of technology to engage communities, it is important to consider implications for teacher preparation programmes as well as in-service professional development.

Finally, although policy examples offer inspiration to countries wishing to invest in better and more impactful family and community engagement in ECEC through digital technology, actual implementation will depend on the connectivity of regions and countries’ technological infrastructure.

References

[9] Andresen, S. et al. (2020), Kinder, Eltern und ihre Erfahrungen während der Corona-Pandemie [Children, Parents and Their Experiences During the Corona Pandemic], University Press Hildesheim, https://doi.org/10.18442/121.

[8] Ayllón, S., H. Holmarsdottir and S. Lado (2021), “Digitally deprived children in Europe”, DigiGen – Working Paper Series, No. 3, https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14339054.

[22] Bacigalupa, C. (2015), “Partnering with families through photo collages”, Early Childhood Education Journal, Vol. 44/4, pp. 317-323, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-015-0724-3.

[40] Burns, T. and F. Gottschalk (eds.) (2020), Education in the Digital Age: Healthy and Happy Children, Educational Research and Innovation, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1209166a-en.

[39] Burns, T. and F. Gottschalk (eds.) (2019), Educating 21st Century Children: Emotional Well-being in the Digital Age, Educational Research and Innovation, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b7f33425-en.

[1] Burris, J. (2019), “Syncing with families: Using technology in early childhood programs”, American Journal of Education and Learning, Vol. 4/2, pp. 302-313, https://doi.org/10.20448/804.4.2.302.313.

[5] Charania, M. (2021), Family Engagement Reimagined: Innovations Strengthening Family-School Connections to Help Students Thrive, Christensen Institute, https://www.christenseninstitute.org/publications/family-engagement-reimagined (accessed on 15 November 2021).

[11] Cohen, F., E. Oppermann and Y. Anders (2020), Familien & Kitas in der Corona-Zeit. Zusammenfassung der Ergebnisse [Families & Kitas in Corona Time: Summary of the Results], University of Bamberg, Bamberg, https://www.uni-bamberg.de/fileadmin/efp/forschung/Corona/Ergebnisbericht_finale_Version_Onlineversion.pdf.

[29] Cortes, K. et al. (2021), “Too little or too much? Actionable advice in an early-childhood text messaging experiment”, Education Finance and Policy, Vol. 16/2, pp. 209-232, https://doi.org/10.1162/edfp_a_00304.

[27] Crozier, G. and J. Davies (2007), “Hard to reach parents or hard to reach schools? A discussion of home-school relations, with particular reference to Bangladeshi and Pakistani parents”, British Educational Research Journal, Vol. 33/3, pp. 295-313, https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920701243578.

[3] Donohue, C. (2016), Family Engagement in the Digital Age, Taylor & Francis.

[30] Doss, C. et al. (2019), “More than just a nudge”, Journal of Human Resources, Vol. 54/3, pp. 567-603, https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.54.3.0317-8637R.

[20] Epstein, J. et al. (2005), Epstein’s Framework of Six Types of Involvement, Center for the Social Organization of Schools, Batimore, MD.

[34] Froment, F., A. García González and R. Bohorquez (2017), “The use of social networks as a communication tool between teachers and students: A literature review”, TOJET: The Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology, Vol. 16/4, pp. 126-144.

[23] Goodman, N. and S. Cherrington (2015), “Parent, whānau, and teacher engagement through online portfolios in early childhood education”, Early Childhood Folio, Vol. 19/1, pp. 10-16, https://doi.org/10.18296/ecf.0003.

[4] Hall, C. and K. Bierman (2015), “Technology-assisted interventions for parents of young children: Emerging practices, current research, and future directions”, Early Childhood Research Quarterly, Vol. 33, pp. 21-32, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ECRESQ.2015.05.003.

[24] Hooker, T. (2019), “Using ePortfolios in early childhood education: Recalling, reconnecting, restarting and learning”, Journal of Early Childhood Research, Vol. 17/4, pp. 376-391, https://doi.org/10.1177/1476718X19875778.

[10] Huebener, M. et al. (2021), “Parental well-being in times of Covid-19 in Germany”, Review of Economics of the Household, Vol. 19/1, pp. 91-122, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-020-09529-4.

[28] Hurwitz, L. et al. (2015), “Supporting Head Start parents: Impact of a text message intervention on parent-child activity engagement”, Early Child Development and Care, Vol. 185/9, pp. 1373-1389, https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2014.996217.

[7] Kapella, O., E. Schmidt and S. Vogl (2022), “Integration of digital technologies in families with children aged 5-10 years: A synthesis report of four European country case studies”, DigiGen Working Paper Series, No. 8, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6411126.

[38] Levin, B. and L. Schrum (2013), “Technology-rich schools up close”, Educational Leadership, Vol. 70/6, pp. 51-55, https://www.learntechlib.org/p/132060 (accessed on 15 November 2022).

[31] Mayer, S. et al. (2019), “Using behavioral insights to increase parental engagement”, Journal of Human Resources, Vol. 54/4, pp. 900-925, https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.54.4.0617.8835R.

[35] Merkley, D. et al. (2006), “Enhancing parent-teacher communication using technology: A reading improvement clinic example”, Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, Vol. 6/1, pp. 11-42, https://citejournal.org/volume-6/issue-1-06/english-language-arts/enhancing-parent-teacher-communication-using-technology-a-reading-improvement-clinic-example.

[32] Meuwissen, A. et al. (2017), Text2Learn: An Early Literacy Texting Intervention by Community Organizations, Center for Early Education and Development, University of Minnesota, http://ceed.umn.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Text2LearnPaper.pdf.

[2] Murcia, K., C. Campbell and G. Aranda (2018), “Trends in early childhood education practice and professional learning with digital technologies”, Pedagogika, Vol. 68/3, https://doi.org/10.14712/23362189.2018.858.

[26] Newport, F. (2014), “The new era of communication among Americans”, Gallup, https://news.gallup.com/poll/179288/new-era-communication-americans.aspx (accessed on 15 November 2022).

[17] OECD (2022), ECEC in a Digital World policy survey, OECD, Paris.

[19] OECD (2021), Using Digital Technologies for Early Education during COVID-19: OECD Report for the G20 2020 Education Working Group, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/fe8d68ad-en.

[6] OECD (2019), How’s Life in the Digital Age?: Opportunities and Risks of the Digital Transformation for People’s Well-being, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264311800-en.

[14] OECD (2019), Providing Quality Early Childhood Education and Care: Results from the Starting Strong Survey 2018, TALIS, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/301005d1-en.

[18] OECD (2019), TALIS Starting Strong 2018 Database, http://www.oecd.org/education/school/oecdtalisstartingstrongdata.htm.

[13] OECD (2011), Starting Strong III: A Quality Toolbox for Early Childhood Education and Care, Starting Strong, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264123564-en.

[21] Oke, A., J. Butler and C. O’Neill (2021), “Identifying barriers and solutions to increase parent-practitioner communication in early childhood care and educational services: The development of an online communication application”, Early Childhood Education Journal, Vol. 49/2, pp. 283-293, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-020-01068-y.

[12] Oppermann, E. et al. (2021), “Changes in parents’ home learning activities with their children during the COVID-19 lockdown: The role of parental stress, parents’ self-efficacy and social support”, Frontiers in Psychology, Vol. 12, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.682540.

[36] Reedy, C. and W. McGrath (2010), “Can you hear me now? Staff-parent communication in child care centres”, Early Child Development and Care, Vol. 180/3, pp. 347-357, https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430801908418.

[37] Sim, M. et al. (2019), “Starting Strong Teaching and Learning International Survey 2018 Conceptual Framework”, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 197, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/106b1c42-en.

[25] Snell, E., B. Wasik and A. Hindman (2022), “Text to talk: Effects of a home-school vocabulary texting intervention on prekindergarten vocabulary”, Early Childhood Research Quarterly, Vol. 60, pp. 67-79, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2021.12.011.

[15] Sylva, K. et al. (2004), The Effective Provision of Pre-School Education (EPPE) Project: Technical Paper 12 – The Final Report: Effective Pre-School Education, Institute of Education, University of London, London.

[16] Tremblay, R., M. Boivin and R. Peters (eds.) (2008), Early Childhood Education and Care Systems: Issue of Tradition and Governance, Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development, University of Montreal, Montreal, Quebec, https://www.child-encyclopedia.com/pdf/expert/child-care-early-childhood-education-and-care/according-experts/early-childhood-education-and-care (accessed on 15 November 2022).

[33] York, B. and S. Loeb (2014), One Step at a Time: The Effects of an Early Literacy Text Messaging Program for Parents of Preschoolers, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, https://doi.org/10.3386/w20659.