The OECD Recommendation on Public Procurement highlights the need to drive performance improvements by evaluating the effectiveness of the public procurement system, from individual procurements to the system as a whole, at all levels of government, where feasible and appropriate (OECD, 2015[8]) (see Box 2.1). Measurement frameworks are essential to assess progress and achievements periodically and consistently and identify any gaps in progress against objectives and targets.

Enhancing the Public Procurement Performance Measurement Framework in Hungary

2. Key aspects to consider in developing a procurement measurement framework

2.1. The objective of the performance measurement framework in Hungary

Box 2.1. The principle on Evaluation of the OECD Recommendation on Public Procurement

i) Assess periodically and consistently the results of the procurement process.

Public procurement systems should collect consistent, up-to-date and reliable information and use data on prior procurements, particularly regarding price and overall costs, in structuring new needs assessments, as they provide a valuable source of insight and could guide future procurement decisions.

ii) Develop indicators to measure performance, effectiveness and savings of the public procurement system for benchmarking and to support strategic policy making on public procurement.

Source: (OECD, 2015[8])

In line with international good practices, the measurement framework developed by Hungary aims at:

Providing a view of the achievement of the public procurement policy objectives set out in the performance measurement framework, through measurable indicators,

Contributing to the identification of areas that require further policy intervention to achieve the policy objectives, and

Supporting the objectives of Act XXVII of 2022 on the control of the use of EU budgetary resources.

The development and implementation of the measurement framework was subject to a Government Decision 1425/2022 (5. IX.) (hereinafter "the Government Decision"), which aimed at developing a performance measurement framework to assess the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of public procurement. This government decision that was published on 5 September 2022, tasked the minister in charge of public procurement policy (the Deputy State Secretariat for Public Procurement Supervision within the Prime Minister’s Office, PMO) to develop a measurement framework that covers at least the areas mentioned in Box 2.2 reflecting their commitments vis a vis the European Commission (with a deadline of 30 November 2022).

Box 2.2. Key areas to be covered by the measurement framework based on the Government Decision 1425/2022

1. the level and causes of unsuccessful public procurement procedures,

2. the percentage of contracts (number and value) fully terminated during contract execution,

3. the share of occurrence of delays in contract completion,

4. the share of cost overruns (including the percentage and volume of overruns),

5. the share of awarded public contracts that explicitly take into account whole life cycle or life-cycle costs,

6. the share of successful participation of micro- and small enterprises in public procurement, across sectors and by sector (based on division and group according to the Common Procurement Vocabulary (CPV),

7. the value of tender procedures with single bids, broken down by national and EU-funded procedures and in total, their ratio to the value of all procurement procedures in total, and by national and EU-funded procedures.

Source: (Hungarian government, 2022[4])

It is worth mentioning that no comprehensive public procurement measurement framework was in place before in Hungary. The measurement framework developed by the PMO goes beyond the areas foreseen in the government decision and its commitment vis a vis the European Commission. This is particularly relevant to highlight given the short time provided to the PMO to prepare and publish the measurement framework.

2.1.1. The measurement framework covers key issues of the procurement system,

Going beyond its initial objective, the measurement framework covers key issues of the procurement system including competition, capacity, the remedies system, centralisation, and the use of public procurement as a strategic lever to achieve wider policy objectives.

In line with the OECD public procurement measurement framework (see Box 2.3), the Hungarian measurement framework includes three main categories of indicators: compliance, efficiency and strategic indicators (OECD, 2022[9]).

Box 2.3. The OECD public procurement performance measurement framework

In 2023, the OECD published a framework for measuring efficiency, compliance and strategic objectives in public procurement. Given institutional and regulatory differences across countries, the proposed framework is designed to be flexible, customisable, and scalable, depending on the needs of the country or organisation wishing to use it. The measurement framework:

Assesses the performance of public procurement at three levels, focusing on procurement procedure (tender level, contracting authority level and national level), depending on the existence of data and possibility to aggregate them.

Identifies three categories of indicators, related to compliance, efficiency and achievement of strategic objectives.

Covers the whole procurement cycle (from planning to contract management).

Can be used by different stakeholders (contracting authorities, procurement authorities, central purchasing bodies, etc.).

In total, the OECD framework accounts for 259 indicators and 45 sub-indicators distributed as follows:

|

Category |

Total indicators |

Total sub-indicators |

|---|---|---|

|

Compliance |

68 |

32 |

|

Efficiency |

128 |

13 |

|

Strategic |

63 |

0 |

|

Total |

259 |

45 |

Source: (OECD, 2023[5])

The exact areas covered by the Hungarian measurement framework are reflected in the sub-categories (see Table 2.1).

Table 2.1. Areas covered by the public procurement measurement framework of Hungary

|

Category |

Sub-category |

|---|---|

|

Compliance |

Legal compliance |

|

Effectiveness of the remedies |

|

|

Transparency |

|

|

Efficiency |

Efficiency of public procurement procedures |

|

Cost-effectiveness /administrative costs |

|

|

Effectiveness of contract performance |

|

|

Competition |

|

|

Capacity |

|

|

Centralisation |

|

|

Strategic |

N/A |

Note: The strategic indicators do not include any sub-category.

Source: (Hungarian Government, 2022[6])

This section provides an overview of the challenges covered by the procurement measurement framework, the issues at stake and the recent developments.

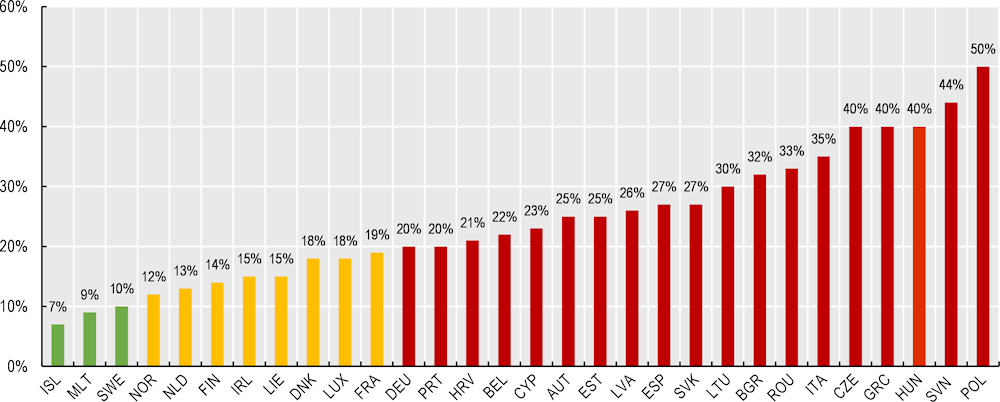

Competition issues and more particularly single bids (contracts awarded in procedures where there was just one bidder) triggered the development of the measurement framework. According to different stakeholders met during the fact-finding mission, the procurement market in Hungary remains vulnerable to anticompetitive practices. This issue was also highlighted in the European Commission annual country report (European Commission, 2022[1]). The proportion of single bid procurement in 2021 based on Tender Electronic Daily Data (TED), which is the online version of the 'Supplement to the Official Journal', remains among the highest in the European Union (see Figure 2.1) (European Commission, 2022[10]). The PMO performed in 2023 an analysis of the evolution of single bidding for both below and above threshold which shows that this indicator is decreasing in 2022. For above EU thresholds, the rate of single bidding dropped from 39.5% in 2021, to 32.9% in 2022, while for procedures below EU thresholds, the single bidding rate decreased from 22.1% in 2021 to 20.1% in 2022. However, the high number of single-bid procedure is not unique to Hungary. In fact, the EU Single Market Scoreboard relevant indicator shows that there are a number of EU Member States in which contracting entities encounter single bidders in more than one-third of their procedures, such as in Poland, Slovenia, Greece, Czechia, Italy, Romania and Bulgaria (European Commission, 2022[10]).

The lack of competition can have several impacts on the economy in terms of value for money and on society in terms of trust. Aware of these issues, the Hungarian government has an objective to decrease the rate of single bidding to 15% by 2024 (for both EU and non-EU financed procedures). It also requested the support of the OECD in improving competition in the public procurement market (OECD, forthcoming[11]).

Figure 2.1. Single bids in EU countries in 2021

Note The colour coding has been defined by the European Commission: Green – satisfactory performance; yellow – average performance; red – unsatisfactory performance.

Source: (European Commission, 2022[10])

Another key element for trust is the cost of access to the remedies system. In Hungary, the Public Procurement Act (hereinafter PPL) establishes the detailed rules for complaints mechanisms in compliance with the EU Remedies Directives. The Public Procurement Arbitration Board (PPAB) is the review body in charge of deciding legal disputes related to public procurement procedures. The PPAB operates in the framework of the Public Procurement Authority (PPA) but acts independently (see Section 2.2.2). The proceeding of the PPAB can be initiated upon application request submitted by those entitled by the PPL to do so (such as bidders) or ex officio (upon the initiation of bodies and persons specified by the PPL) (Hungarian government, 2021[12]).

Fees are applicable if the review procedure is initiated upon request. The administrative service fee equals to 0.5% of the estimated value of the procurement, but it is at least HUF 200 000 (approx. EUR 572). The legal framework also establishes a maximum fee of HUF 25°000°000 (approx. EUR 71°444) in the case of public procurement above the EU threshold, and HUF 6 °000°000 (EUR 17°146) in the case of a procurement below the EU threshold) (Hungarian government, 2015[13]). Various stakeholders, including NGOs in Hungary are repeatedly inviting the government to lower the fees to enable SMEs to afford the review procedure and to enhance participation on the public procurement market (Transparency International, 2018[14]). The first report of the Hungarian measurement framework also highlights the need to reduce the fees based on response to a survey that was addressed to different stakeholders (Hungarian Government, 2023[7]). Aware of the need to reduce the level of the remedies fees, the Hungarian government included it as one of the actions to its action plan on reducing single bids (Hungarian Government, 2023[15]). As such, an amendment to the Public Procurement Act which, among others, revises the fees has been submitted to parliament on 14 November 2023, with the aim of providing easier access to remedies.

Regarding centralisation, discussions with several stakeholders highlighted potential issues with the efficiency of the centralisation scheme in Hungary in particular regarding the use of framework agreements and its potential impact on competition and on value for money. The use of central purchasing bodies (CPBs) services takes place outside of the electronic public procurement system (EKR), limiting the availability of data on the exact volume or on the savings achieved and thus on the performance of CPBs (Integrity Authority, 2023[16]).

In terms of strategic public procurement, in its 2021 Monitoring Report to the European Commission, the Hungarian Government also highlighted the low uptake of sustainable public procurement (SPP) in Hungary and mentioned the lack of knowledge and the risk-averse behaviour of contracting authorities as the main obstacles to SPP. This reluctance regarding the use of social and green aspects is more tangible in the case of EU-funded projects due to the strict and overly restricting approach of audits carried out for EU-funded public procurements in terms of the appropriate use of green and social aspects as award criteria or special conditions for the contract performance. As a result, contracting authorities tend to keep their procurement procedure “simple”. In addition, among the contracting authorities persists the misconception that the application of SPP aspects is complicated and contributes to lengthy procedures and increased prices. Public organisations tend to stick to old routines and are very distrustful of new procurement processes. (European Commission, 2021[17]). As a result, the share of lots with an environmental aspect ranged between 5.4% in 2020 and 8.2% in 2022. Aware of these challenges, in January 2023, the Hungarian government adopted a Green Public Procurement (GPP) Strategy (2022-2027) (Hungarian Government, 2023[18]). The Strategy encourages contracting authorities to procure goods and services with a reduced environmental impact as widely as possible, in addition to the mandatory cases of applying GPP considerations in public procurement. The Strategy aims at achieving 30% of public procurement procedures with green considerations by 2027. To achieve this goal, the Strategy envisages a set of actions for ensuring that a system of support tools will be developed to enhance the skills and competences needed to conduct GPP effectively and to disseminate good practices. On the other hand, to ensure that the Strategy will deliver the expected impacts, its implementation requires structured monitoring which itself requires data. The Strategy itself foresees a mechanism for the monitoring and reviewing of the strategy implementation. It will be monitored by the Minister responsible for public procurement (PMO at the time of drafting the report) and a report on the implementation of the strategy will be submitted to the Government every three years (first half of 2025 and first half of 2028). Based on EKR data, the PMO will also monitor the evolution of the number and value of green public procurement and their share, as well as the evolution of the share of clean vehicles. The performance measurement framework could support this monitoring and reporting obligation. The PMO also collaborated with the OECD on a project to enhance the uptake of Life Cycle Costing (LCC) methodology through the development of dedicated tools (OECD, 2022[19]). These actions and initiative should support an enhanced implementation of GPP, and more generally SPP in the country.

Capacity is key to ensure the well-functioning of the public procurement system. Discussions with several stakeholders highlighted capacity issues within contracting authorities (European Commission, 2021[17]).

2.1.2. A framework that could be further improved to reflect additional procurement challenges

While the current measurement framework considers several public procurement areas and issues, it could be further improved in future revisions by integrating indicators focusing on integrity and monitoring/oversight of the public procurement system (see Section 3.3.3). However, it is worth mentioning that the framework already includes indicators linked (but not focusing) on these topics. For instance, transparency is key to ensure the integrity of the public procurement system and the measurement framework includes transparency related indicators.

In terms of integrity, since 2012, Hungary dropped 11 points in Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index and was ranking 77th out of 180 countries in 2022 (Transparency International, 2023[20]). This perception is also confirmed by other perception surveys. For instance, according to the responses to the survey of Eurostat in 2022 - Special Eurobarometer 523, the Hungarians’ perception of corruption is significantly higher in all aspects compared to the EU average. 91% of Hungarians think that corruption is very widespread in Hungary compared to the EU average (68%). Public procurement was ranked the third place in terms of area where Hungarians think corruption is widespread (after the political parties and politicians) (European Union, 2022[21]). A positive step taken by the government is the establishment in 2022 of the Integrity Authority to enhance oversight over the spending of EU funds; but also, the establishment of the Anti-Corruption Task Force, responsible for examining Hungary’s anti-corruption measures and putting forward proposals for their improvement. Hungary is also in the process of adopting a new Anti-Corruption Strategy in line with its obligations under the EU Commission’s conditionality procedure and Hungary’s Recovery and Resilience Plan.

Given that integrity is one of the drivers of trust for democratic governments (OECD, 2022[22]), the high perception of corruption could impact the trust in the public procurement system. In Hungary, the first annual report of the Integrity Authority on the integrity risks of the Hungarian public procurement system highlights that dysfunctionalities of the Hungarian public procurement system led to a lack of trust in the public procurement system (Integity Authority, 2023[23]). The Integrity Authority is also looking closely at indicators regarding integrity in public procurement that are published in its annual report. These indicators are based on the Methodology for assessing public procurement systems (MAPS). While the Integrity Authority report and the one on the public procurement measurement framework of the PMO are published in different months of the year, it could be beneficial for those two entities to join forces on integrity related indicators to provide a comprehensive picture of the public procurement system.

Oversight and control mechanisms are key to support accountability throughout the procurement cycle (OECD, 2015[8]). In Hungary, despite the existence of different institutions in charge of controlling public procurement spending (see Section 2.2.2), their controlling / auditing methodologies and practices vary from one institution to the other. All types of controls are stricter for EU funded procurement than for nationally funded ones. The stricter control is also reflected in data on single bids which is much lower for EU funded projects, with a rate of single-bidding of 13.3% for EU-funded projects versus a rate of 31.3% for projects funded by national resources in 2022. Several institutions, including the Integrity Authority and the European Commission (in its country report) highlighted that the public procurement control system showed weaknesses, and identified serious, systemic deficiencies and irregularities. Similarly to integrity indicators, the Integrity Authority report also looks at indicators related to effective control and audit systems (Integity Authority, 2023[23]; European Commission, 2020[24]). However, according to the Hungarian authorities, an audit of the public procurement control system for EU funded projects conducted in November 2022 by the European Commission concluded that the public procurement control system “works, but some improvements are needed”.

2.2. A framework that responds to the needs of different stakeholders

The development of the public procurement measurement framework is led by the public procurement policymaker, the Deputy State Secretariat for Public Procurement Supervision within the Prime Minister’s Office (hereinafter the PMO). One of the goals of the framework is to contribute to the identification of areas requiring further policy intervention. Given that public procurement is a multi-disciplinary area, different stakeholders could be consulted and involved in the development of the measurement framework. In line with international good practices, the Government Decision foresees consultations with independent non-governmental organisations active in the field of public procurement and public procurement experts in Hungary. These experts formed a working group. However, given the tight deadlines, no formal consultations were established with other key public procurement stakeholders.

2.2.1. Improving the consultation process with the working group

As part of its commitments to the European Commission, the Hungarian government committed to develop the public procurement performance measurement framework with the ”full and effective involvement” of independent non-governmental organisations (NGOs) active in the field of public procurement and public procurement experts. This commitment is reflected also in the Government decision (Hungarian government, 2022[4]). The independent NGOs and public procurement experts shall be selected through an open, transparent and non-discriminatory selection procedure based on objective criteria related to expertise and merit.

Hungary established a working group comprised of seven experts selected following a call for interest. These experts are expected to:

Share their opinions and suggestions on the design of the Framework (indicators, definitions and methodologies used)

Share their opinion and suggestions when analysing indicators and drawing conclusions from the data.

These opinions and suggestions should be taken into account and reflected in the final version of the documents.

However, discussions with members of the working group highlighted some issues that could be improved in the future.

In relation to the selection process, following a call for application, 15 applications were received, of which two by organisations and 13 by individuals while initially three posts were reserved for organisations. (European Commission, 2022[25]). The two organisations that applied and were selected are “Transparency International Hungary” and “the Association of Public Procurement Professionals”. This association represents experts that play a key role in the public procurement system. Indeed, the PPL introduced the category of “accredited public procurement consultant” (in Hungarian Felelős Akkreditált Közbeszerzési Szaktanácsadó, FAKSZ) as of 1 November 2015 (replacing the previous profession of “official public procurement consultants” introduced in 2004). The contracting authority must involve a certified public procurement consultant in certain public procurement procedures defined in the PPL (Hungarian government, 2021[12]). The involvement of a certified public procurement consultant is mandatory in case of:

i) procurement of goods and services, if the contract equals or exceeds the EU threshold;

ii) procurement of public works contracts, if the contract reaches HUF 700 million (approx. EUR 2 million); or

iii) procurements funded in part or in whole from EU funds, except for the implementation of the procurement procedure where the contract is awarded based on a framework agreement and when the values do not exceed those mention in i) and ii)

iv) contracts awarded based on a framework agreement (except in the case of a direct order placed under the conditions set out in the framework agreement) when the values exceed those mentioned in i) and ii).

FAKSZ were replaced by “state public procurement consultants” (in Hungarian: Állami Közbeszerzési Szaktanácsadó, ÁKSZ) as of 8 November 2023, although those having the title ‘FAKSZ’ may still conduct public procurement procedures related to the purchase of goods and services (but not works) until 30 June 2026. However, this change won’t affect the membership of the working group.

Most of the working group experts who applied to the call for application have a legal background. According to working group members, given the multidisciplinary nature of public procurement and the strong data component of indicators, ensuring a more diverse background (including on economics and statistics) of working group members could bring more added value to the development of the measurement framework and the underlying analysis.

Other important challenges that were highlighted by the working group are the late clarification and adoption of the rules of operations of the working group (after the selection of the working group members) and the pressing time to provide feedback. Indeed, the strong time constraints imposed on the PMO to develop the framework and to undertake the assessment and publish the results made the interactions with the working group more challenging. Indeed, for a consultation process to be efficient, adequate time should be provided to the different stakeholders to provide meaningful feedback. For example, the working group had ten days to provide feedback on the list of indicators of the measurement framework before discussing it during a dedicated meeting. Providing feedback under time pressure is particularly challenging for experts representing organizations as the provision of feedback requires internal consultations within their organisations. In its interactions with the working group and in the future development of the measurement framework, the PMO should consider providing adequate time for each member to provide more valuable comments.

2.2.2. Involving more stakeholders in the development and analysis of the measurement framework

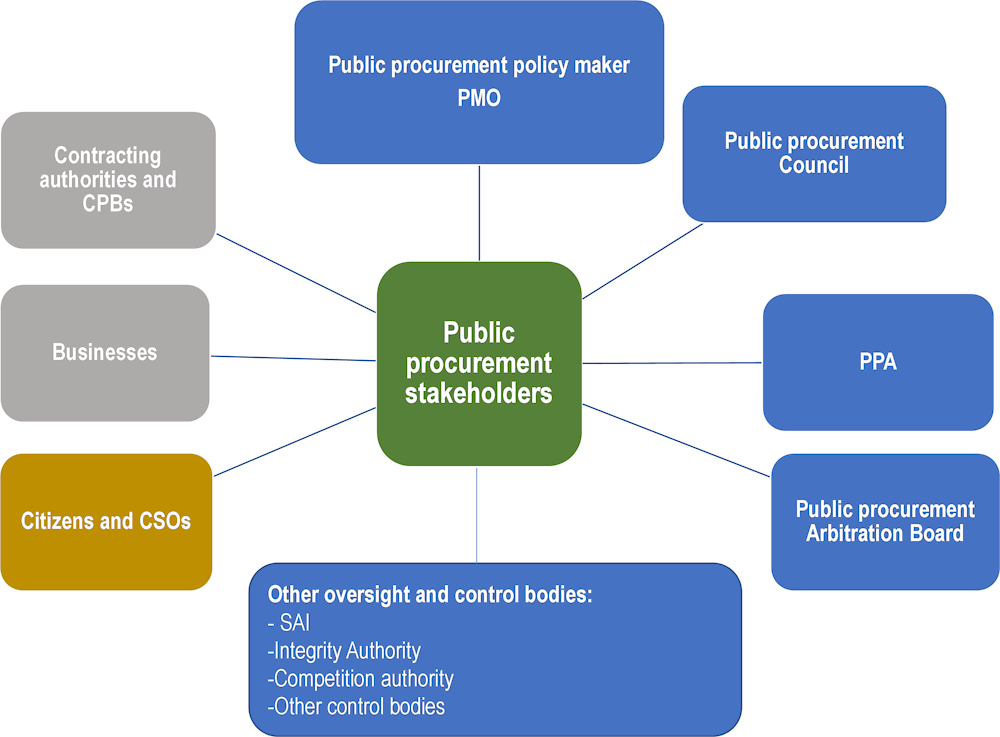

The measurement framework aims among other goals to “contributing to the identification of areas that require further policy action to achieve the legal policy objectives”. Different stakeholders can have a different perception of these areas. While the OECD welcomes the consultation with organisations and experts in the public procurement field through the established working group, it also highlights that other key stakeholders could bring valuable input to the measurement framework itself (beyond the provision of data) and to the underlying analysis. Stakeholder involvement could also bring a consensus on the measurement framework and the methodology used to be shared and used by all stakeholders. This is particularly relevant given that these stakeholders may collaborate on other topics. Figure 2.2 provides the public procurement stakeholder mapping in Hungary. The below section provides a description of the role of these stakeholders and how they could contribute to strengthen the work of the measurement framework.

Figure 2.2. Public procurement stakeholder mapping in Hungary

The Public Procurement Council: The Council has seventeen members representing different public interests, the contracting authorities and the bidders. Seven members are appointed directly by the government – representatives of various ministries – or by organisations under the control of the government (e.g. the tax authority). The other members represent organisations such as the Integrity Authority, the Competition Authority, various chambers of commerce and federations. The PPL mentions that the Council operates within the Public Procurement Authority (PPA). The President of the Council is the President of the PPA, who is also a member of the Council – included in the seventeen members (Hungarian government, 2021[12]). The Council decides on the appointment of the President of the PPA by a two-thirds majority of its members present at a dedicated meeting and exercises the employer’s rights over the President of the PPA. It also appoints and dismisses the President, the Vice-President and the arbitrators (“commissioners”) of the Public Procurement Arbitration Board, also by a two-thirds majority of its members present during a related meeting. Furthermore, it issues guidelines on the interpretation of public procurement law (Public Procurement Authority, n.d.[26]). Given that most relevant stakeholders part of the Council should be consulted separately, it is not necessary to directly involve the Council in the development of the public procurement measurement framework.

The Public Procurement Authority: The PPA is an autonomous state administration body reporting to Hungary’s National Assembly. The PPA is responsible for monitoring the application of the public procurement law, issuing guidance to support the practical implementation of the public procurement legislation and formulating opinions on draft legislations. It also collects and publishes operational and statistical information through its annual reports and operates the Official Public Procurement Journal (Közbeszerzési Értesítő in Hungarian) (Hungarian government, 2021[12]). In 2020, the Hungarian Central Statistical Office accredited the statistical activity of the PPA, and as a result, the PPA became member of the Official Statistical Service. In addition, the PPA operates the Public Procurement Database, the central register of public procurement procedures (currently used only as an archive for data on procedures conducted before the mandatory introduction of EKR). It also organises conferences, training and professional courses. The PPA controls the negotiated procedures without prior publication as well as monitors the amendment and performance of public contracts (Public Procurement Authority, n.d.[27]).

Furthermore, the PPA is providing public procurement data to the Parliament on an annual basis, through its annual reports (Hungarian government, 2021[12]) that present various aspects of the public procurement system, analysing trends in the public procurement market and presenting the activities of the PPA. The PPA also monitors the performance of the public procurement system based on indicators reflected in its annual report. However, for some indicators, such as the one related to single bids the PPA and the PMO have been using a different methodology (OECD, forthcoming[11]).

Given its role in the public procurement system, it is particularly relevant to involve the PPA in the performance measurement framework development and to ensure a consensus around the selected indicators and the methodologies used.

The Public Procurement Arbitration Board (PPAB): It is the review body in charge of deciding legal disputes related to public procurement procedures. The PPAB operates in the framework of the PPA but acts independently. The PPAB is composed of public procurement commissioners, a chairperson and a vice-chairperson. The proceeding of the PPAB can be initiated upon application submitted by those entitled by the PPL to do so (such as bidders) or ex officio (upon the initiation of bodies and persons specified by the PPL) (Hungarian government, 2021[12]). The PPAB could bring valuable input to compliance indicators of the framework and support the PMO in refining the methodology for indicators related to the remedies system.

The Integrity Authority (IA): It was established as an autonomous administrative body in October 2022 in the context of the European Commission’s conditionality procedure and Hungary’s commitments under its Recovery and Resilience Plan (European Commission, 2022[3]). It started its operation in 2023. The IA may act in all cases where an authority or body having the task or competence to use or control EU funds have not taken the necessary measures in order to prevent, detect and correct fraud, conflict of interest, corruption or any other violation of the law or irregularities that affect the financial interest of the European Union. It has competence to control projects and public procurement procedures financed entirely or partly from EU funds, and it may call other authorities having the competence to control the use of EU funds to initiate a procedure. When controlling cases, the IA can bring a case before the court. The tasks of the IA include the analysis of integrity risks, the preparation of an annual integrity report, and keeping the record on the legal persons (economic operators) excluded from the public procurement (Hungarian Government, 2022[28]).

The law establishes also an “Anti-Corruption Task Force” to work alongside the IA. The Task Force is independent from the Authority, and it has 21 members: the President of the IA, ten member representing governmental bodies (e.g. ministries, the tax authority, etc.) and ten independent non-governmental members active in the area of anti-corruption or public procurement. Its task is to examine the existing anti-corruption measures and to elaborate proposals in relation to the prevention, detection, prosecution and sanction of corrupt practices, and to prepare an annual report (independently from the IA), analysing corruption risks, the effects of anti-corruption measures, and, once adopted, the implementation of Hungary’s forthcoming Anti-Corruption Strategy.

The first IA’s Annual Report (Integrity Authority, 2023[16]) and the Integrity Risk Assessment Report of the Hungarian Public Procurement System (Integity Authority, 2023[23]) published in 2023 includes several findings in relation to public procurement based on EKR and data provided by some stakeholders including central purchasing bodies. Given its role in the public procurement system, the IA could bring valuable input to the framework, in particular to indicators relevant for the integrity of the public procurement system.

The Competition Authority is responsible for safeguarding competition, and it has the mandate to investigate public procurement cartels and take actions against anti-competitive behaviours. The Competition Authority uses several tools to discover cartels in the public procurement market, such as (i) leniency policy and cartel informant reward, (ii) Cartel Chat, an anonymous communication form freely accessible on its website where anybody can share information directly with the Authority, (iii) methodology about the promotion of the identification of signals concerning public procurement cartels. The Competition Authority also develops publications and learning materials for contracting authorities and economic operators, available for free on its website (Hungarin Competition Authority- GVH, 2006[29]). Although the Competition Authority is performing its tasks in terms of fighting against bid-rigging and promoting competition as part of its advocacy work, during the fact-finding meetings, several stakeholders expressed their expectations for a more active Competition Authority in fighting bid rigging and enhancing competition in the public procurement area. Given its role in the public procurement market, the Competition Authority could definitely bring valuable input to indicators in relation to competition for the future development of the public procurement performance measurement framework.

Businesses: In Hungary, data from 2023 shows there are more than 1.8 million of registered businesses in the country and most of them are micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (Hungarian Central Statistical Office, 2023[30]). In terms of sectorial activity, around one-fourth of all companies operate in the agriculture sector. Other sectors with significant business activity include real estate, scientific and engineering activities, trade and the construction sectors (Hungarian Central Statistical Office, 2023[31]). More than one-third of the business associations operate in Budapest, or in the county around the capital (Hungarian Central Statistical Office, 2023[32]).

The business association with the highest number of members is the Hungarian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (Hungarian Chamber of Commerce and Industry, n.d.[33]) which is a chamber with a general scope. However, there are specialised chambers, for example, for architects, and for engineers. There are also important national federations and associations with a significant lobbying power, such as the Confederation of Hungarian Employers and Industrialists (MGYOSZ), which is the largest and oldest business interest group in Hungary (MGYOSZ, n.d.[34]), the National Federation of Hungarian Building Contractors (ÉVOSZ), and the Federation for information and communication technologies (IVSZ).

Public procurement is the area where the public sector and the private sector meet to ensure the delivery of public services. Measuring the performance of the public procurement system in some cases relies also on the performance of the private sector partner. There are 41 898 businesses registered in the EKR, from which 88% are SMEs. As mentioned in Section 2.3.4, businesses were involved in the calculation of indicators through surveys. However, representatives from the private sector could bring valuable input to the measurement framework by for instance developing indicators in relation to their areas of concern but also by supporting an adequate design of surveys.

Control bodies: In addition to the control activities of the PPA and the IA, there are other relevant control bodies operating in the public procurement area. The State Audit Office (SAO) conducts external oversight of public procurement procedures, providing recommendations and legally binding obligations to correct the most serious irregularities. It also conducts evaluations of the public procurement system or prepares analysis of certain aspects of the public procurement system, such as green public procurement in 2020.

The Government Control Office (‘KEHI’) is the internal controlling body of the Government, it can control the use of public funds and the management of national assets. It is controlled by the minister responsible for the general political coordination, that is the minister of the Government Office of the Prime Minister (Miniszterelnöki Kormányiroda). The activity of the Government Control Office and its reports are not publicly available; therefore, it is not clear how active the Office is in the area of public procurement. However, legal remedy cases initiated by the Office before the PPAB can be found. In addition, the Office has a dedicated department for the control of public procurement.

In Hungary, the Directorate General for Audit of European Funds (EUTAF) is an independent authority carrying out ex-post audits of projects financed from EU funds, examining also the related public procurement procedures. The establishment of this authority derives from Regulation 2021/1060/EU on the common provisions of the EU funds that obliges Member States to set up an audit authority reporting directly to the European Commission. Therefore, EUTAF have ample data on public procurement procedures financed from EU funds.

Managing authorities bear the main responsibility for the effective and efficient implementation of EU funds and therefore they fulfil a wide range of functions, in relation to the selection of operations, programme management and controlling the use of EU funds by the beneficiaries. This entails detecting irregularities, including those related to public procurement procedures. The State Secretary for EU Developments and his Deputy State Secretary for the coordination of EU developments within the Prime Minister’s Office coordinate and to a certain extent supervise all the managing authorities.

Contracting authorities and CPBs: According to the PMO there are 9481 contracting authorities in Hungary in 2023. Data from EKR shows that around 73% of these contracting authorities are considered as “classical contracting authorities”, and more than 99% of contracting authorities are operating at the subcentral level. Around 25 contracting authorities represent the Central Government. Around 7% of all contracting authorities are companies, organisation that normally would not fall under the scope of the PPL, however, they finance their procurement from subsidies or public funds. Regarding centralisation, four CPBs are active in Hungary (see Box 2.4). Involving CPBs and a representative sample of contracting authorities could also bring valuable input to the framework and the analysis.

Discussions with CPBs highlighted the feeling that the measurement framework is not adapted to their needs. Further collaboration with CPBs and CAs (above the provision of data) could strengthen the measurement framework and ensure its use by key public procurement players.

Box 2.4. CPBs in Hungary

The Directorate General for Public Procurement and Supply (KEF)

KEF is the main (and oldest) CPB carrying out centralised public procurement activities for ministries, other government institutions and for “organisations having a separate chapter in the Central Budget Act”. For these organisations, the use of KEF is mandatory for those product categories that are listed in the Government Decree No. 168/2004 (i.e. office furniture, stationary and office products, vehicles, fuels, travel arrangements, health products and services, facility management services for inpatient specialist care facilities and energy). Other organisations (including contracting authorities at the local level) have the opportunity to join the central purchasing system on a voluntary basis. Besides the CPB function, KEF is also in charge of operating and maintaining government buildings and vehicle fleets.

The Digital Government Agency (DKÜ)

In 2018, the Government introduced further centralisation in the field of government ICT procurement and set up a new agency, the Digital Government Agency (Digitális Kormányzati Ügynökség, DKÜ) with the aim of unifying and centralising the government’s ICT procurement as well as making public ICT spending more transparent. DKÜ set up a repository of the ICT assets of the government. The relevant public bodies and companies are required to upload their annual IT development and procurement plans to the Centralised IT Public Procurement System (KIBER) by 31 March each year. It is mandatory for budgetary bodies under the direction or supervision of the Government, the budgetary bodies or institutions under their management or supervision, the Government Office of the Prime Minister, the foundations and public foundations established by the Government and the state-owned companies to make their IT purchases via the services offered by DKÜ.

The National Communication Office (NKH)

NKH is in charge of procuring all communication services and organizational development services for central government bodies.

2.3. Ensuring the availability and quality of data

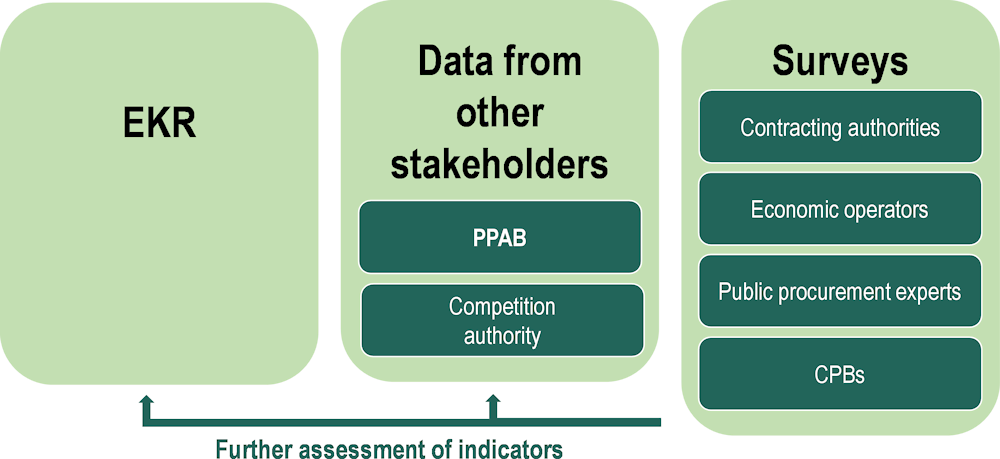

Data plays a crucial role in improving the value for money the public sector gets through public procurement. The 77 indicators of the public procurement measurement framework are based on three types of data sources:

i) data from the national e-procurement system EKR,

ii) data provided directly by relevant stakeholders, and

iii) surveys targeting relevant stakeholders (contracting authorities, economic operators, public procurement experts and CPBs).

These three sources were used for different reasons: some data of the measurement framework cannot be calculated through the e-procurement system, EKR and some data belong to other stakeholders and need to be provided directly by them.

Furthermore, the analysis of some indicators requires further information, including opinions and feedback from different stakeholders (Figure 2.3). While for part of the indicators the main approach to data collection during the permanent operation of the framework has not been yet set, data availability and quality should be considered beforehand.

Figure 2.3. Data sources used for the calculation and assessment of indicators

2.3.1. The e-procurement system: EKR

One of the main data sources of the performance measurement framework is EKR as 30 indicators (39% of indicators) are based on this data source. The use of the EKR is mandated by the PPL for all contracting authorities and contracting entities for initiating and conducting public procurement procedures both below and above EU public procurement thresholds. EKR is operated by “Új Világ Nonprofit Szolgáltató Kft”, a State-owned company under the control of the Prime Minister’s Office. The EKR was developed in late 2017 and became compulsory for all contracting authorities since the 15th of April 2018 (though central purchasing bodies may partially use their own platforms).

Discussions with several stakeholders highlighted that the quality of the data in the EKR system is improving compared to the first years of operation. This could be explained by the strict control of notices performed by PPA prior to their publication. However, there are still some issues related to the manual entry of some information by contracting authorities or economic operators (Integity Authority, 2023[23]). For instance, issues were identified in relation to the value of contracts. Therefore, the PMO and PPA should raise awareness within contracting authorities on the importance of ensuring a good quality of data entered manually.

2.3.2. Leveraging eForms to enhance data collection

All member states of the European Union, including Hungary, must implement eForms by the 25th of October 2023. eForms are an EU legislative open standard for publishing public procurement data, established under Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2019/1780. They are digital standard forms used by public buyers to publish notices on the Tenders Electronic Daily (TED) (European Commission, n.d.[40]). The eForms regulation established six standard forms, covering forty notices. The standard forms (eForms) contain fields with some mandatory and others optional (European Commission, 2020[41]).

As mentioned by the European Commission, eForms are at the core of the digital transformation of public procurement in the EU. Through the use of a common standard and terminology, they can significantly improve the quality and analysis of data. This will in turn increase the ability of governments to make data-driven decisions about public spending and make public procurement more transparent (European Commission, n.d.[40]).

Indeed, eForms are much more than solely the new templates for the collection of information to be published in TED; eForms represent the EU’s open standard for publishing public procurement data. This new data standard is expected to improve the availability, quality and (re)usability of procurement data (TED data) at EU level. Therefore, eForms implementation in the EU member states should not consider as a low-level form-filling exercise, but rather as a key tool to build a procurement data architecture that facilitates the uptake of digital technologies for procurement governance and a way to collect information on many policy priorities, such as green, social and innovation procurement data (OECD, forthcoming[42]). The eForms are also key for the public procurement dataspace (PPDS) which is another key element of the digital transformation of public procurement in the EU.

Therefore, the implementation of eForms and the choices that the Hungarian government will make are key for data collection and thus for the access and reliability of data. Discussions with the Hungarian representatives highlighted that the implementation of eForms will probably improve the data collection process. Most eForms fields with a relevance in data collection, especially in case of currently not available data will be mandatory or conditionally mandatory.

2.3.3. Integrating key systems with EKR

In the last decades, countries have been expanding functionalities of e-procurement systems to achieve better outcomes and deliver services more effectively and efficiently. Following these technological advances, vertical and horizontal integration of e-procurement systems with other governmental platforms are the next steps to achieve a fully integrated procurement system to provide government with full visibility on the use of public funds across different government departments and to achieve various efficiency gains for both the public and the private sector (OECD, 2023[5]).

Stakeholders including the PPAB, the Competition Authority and CPBs directly provided their data to the PMO for the calculation of some indicators (42.8 % of indicators). The PPAB was requested to provide data on the remedies system (13% of indicators), CPBs were asked to respond to a targeted survey to provide relevant data to the PMO for the calculation of indicators on centralization (28.6 % of indicators) and the Competition Authority also provided data to calculate one indicator.

Many of the indicators based on data provided by the PPAB and CPBs could have been provided directly to the PMO if the systems were integrated with EKR and if the data was structured. Regarding the remedies system, review procedures are initiated by submitting a request to the PPAB through the government's general website for electronic administration (www.magyarorszag.hu). Then, all information on the remedies system is registered in the PPAB internal system. Information on the procedures initiated and the decisions is published on sub-websites of the PPA dedicated to the PPAB with unstructured data (in PDF documents) (Public Procurement Authority, 2023[43]) (Public Procurement Authority, 2023[43]).

Public procurement procedures initiated by a CPB to conclude a framework agreement or a DPS are conducted in EKR according to the general rules. However, all four CPBs established their own e-procurement portals for contracting authorities to use when they want to procure goods, services or public works from established framework agreements or DPSs (call- offs or mini-competition). These portals rely on systems that are not integrated with EKR. Furthermore, discussions with stakeholders highlighted that each of these systems is different. Therefore, EKR does not include key data on public procurement from established framework agreements and DPSs. This lack of integration with EKR led to a lengthy process for the PMO to assess and clean the data received from CPBs.

While EKR and CPBs systems and the PPAB system could remain independent, their integration could contribute to enhancing the efficiency of the monitoring of the public procurement system and to take the necessary actions. For instance, some countries like Malta, Slovenia and Croatia developed a functionality in their e-procurement system for bidders to challenge public procurement system allowing the public procurement policy maker to have preliminary data on the remedies system (OECD, 2023[44]).

When the data was provided by other stakeholders, the PMO was responsible for data cleaning and classification. For instance, for the indicator on “the most frequently violated legal provisions”, the PMO had to assess all the documents and data provided by the PPAB and the identified infringements of the specific provisions of the PPL. Enhancing the collaboration with stakeholders providing data on the data classification could enable the PMO to ease the process of calculating indicators and thus enhance the monitoring of the public procurement system.

2.3.4. Enhancing data collection through surveys

In specific cases, when data is not available in the short term, stakeholders can consider using surveys to collect relevant data and build indicators (Appelt and Galindo-Rueda, 2016[45]). Surveys can also be used to assess perception of stakeholders in specific areas to complement the assessment of data or indicators.

In the framework of the measurement framework of Hungary two surveys were launched. One targeting economic operators, contracting authorities and public procurement experts (covering 14.3% of indicators) and another one for CPBs (covering 28.6 % of indicators). The development of the surveys benefited from valuable comments from the working group. To enhance the efficiency of surveys to calculate relevant indicators or to complement the analysis of some indicators, it is relevant to assess: i) the design of the survey, ii) the number of respondents and iii) the frequency of launching surveys. This is particularly relevant given the fact that for the general survey that was published online, PMO noticed that a significant number of stakeholders started to fill the questionnaire but did not complete it.

Improving the design of the surveys

The content of the survey could be further improved to enhance the quality of data and to further refine the analysis. The different areas of improvements are summarised in Table 2.2. The design of the general survey could also impact the number of respondents.

Table 2.2. Areas for improvement of the content of public procurement surveys in Hungary

|

Areas of improvement |

|

|---|---|

|

Order of questions |

Changing the order of some questions |

|

Categorising the questions based on the three categories of indicators of the framework |

|

|

Quality of data |

Clarifying the time period considered |

|

Providing clear definitions and guidance for some questions |

|

|

Refining the analysis |

Asking suppliers in which sector(s) they are active. |

|

Adding more response options |

|

|

Adding a breakdown |

|

|

Adding questions |

The order of some questions should be reviewed. General question could be brought to the beginning of the survey. For instance, the annual number of public procurement procedures carried out by an organisation should be asked in the beginning of the survey. Furthermore, it could be relevant to structure the questions around the three categories of indicators of the framework (compliance, efficiency and strategic objectives).

On the quality of data for the general survey, it is recommended to clarify the time period considered for several questions. For instance, one of the questions aims at identifying if stakeholders have been involved in a public procurement challenge before the PPAB (Have you ever been involved as an applicant or defendant in a review procedure before the PPAB?) This question does not mention any period and given the different changes of the remedies system, a time period will enable an improvement of the quality of data and the underlying analysis.

Another key aspect related to the quality of data is the provision of clear definitions and guidance for some questions. For instance, questions on “the costs of procurement and legal advisory services for contracting authorities” would need further guidance as they mention some costs that can be included but do not list all the potential costs. For instance, when calculating these costs, it is not clear if stakeholders should account for costs related to facilities (office space, IT equipment, etc.), staff time of management, etc. This might cause a different understanding of the questions by different respondents and impact the comparability of answers. The question for the costs incurred by suppliers also requires reviewing the guidance provided to ensure the comparability of data as it clearly mentions that it should include “consultancy services” but not “salary costs”. However, depending on the size of the economic operator, some may rely on their internal staff to prepare their bids rather than external consultants. Another relevant example is related to question on the number of staff employed to manage public procurement procedures. The question does not mention clearly “full staff equivalent” as in some small entities, employees can work partly on public procurement.

To further refine the analysis, some questions with response options can include additional options. For instance, for the question addressed to contracting authorities on the use of CPB services, only 3 options were available (i) Yes, under legal obligation, ii) Yes, on a voluntary basis, iii) No. However, other options could be envisaged as for some procurement categories a contracting authority might be obliged to use CPBs services and for others they use them on a voluntary basis. Another example is the one on the question related to the extent to which some “statements” help to increase the intensity of competition and the willingness to bid for public contracts”. Discussion with stakeholders highlighted that it could be relevant to add as a statement “sanctioning contracting authorities”.

The refinement of some questions might also require a breakdown. For instance, the question on the savings performed through the use of CPB services might highly depend on the procurement category. Having a general question might not help to refine the analysis and to provide a real picture on the potential savings achieved through centralisation.

Regarding additional questions to include in the survey, the PMO could add two categories of questions: i) those related to the additional indicator it may consider adding, and ii), additional general questions to further refine the analysis. For instance, it could be relevant to ask the different stakeholders about the main procurement categories where they are active, their procurement volume, etc.

Ensuring a larger number of responding stakeholders

The survey targeting different stakeholders was answered by 570 participants, 377 from contracting authorities, 31 from economic operators, 77 from public procurement experts and 85 were form the category “others”. While the PMO mentioned in its report on the public procurement measurement framework that particular attention was given to achieve a sufficient number of responses, the actual number is relatively low. Indeed, 41 898 economic operators were registered in 2022 in EKR (not all of them active in that year), so less than 0.07% of them responded to the survey. Regarding contracting authorities, around 10 % of the active ones in the past three years responded to the survey. Given that surveys are not only used to complement the analysis of indicators but also to calculate indicators, the relatively low number of responses may impact the assessment and related findings. In particular, the results of these indicators might not represent the real practices of the different procurement stakeholders. The low responses to the survey could be explained by different factors, including the lack of incentives to respond, the structure of the survey, the timeline to respond and the lack of advertisement of the survey.

The general survey was published in EKR and the PMO mentioned discussions with the Chamber of Commerce to ensure a wider dissemination of the survey to businesses. For the general survey, it was available during 26 days to stakeholders, and CPBs had 9 days to complete their questionnaire. The dissemination of the survey was impacted by the time constraint to finalise the public procurement measurement framework and to prepare the report on the measurement framework.

If the PMO wants to keep the survey open and does not want to use a sampling method, in future editions, it should decide on a minimum number of participants to ensure the results of the indicators are representative and “acceptable”. In parallel, it should consider allowing more time to respond and further disseminate the surveys using different means such as i) relevant stakeholders websites (e.g. the websites of the PPA, the Integrity Authority, the Competition Authority, the Hungarian Chamber of Commerce and Industry, etc), ii) the mobile application managed by the PPA, the “Daily Public Procurement” (Napi Közbeszerzés in Hungarian) that offers a customised free news channel for the users, on public procurement and, iii) social media. For instance, Scotland launched a survey dedicated to suppliers in 2020 and received 1556 responses by using different means to promote the survey (see Box 2.5). Furthermore, it is relevant to mention in the beginning of the survey the average time it may take to complete it to avoid having participants starting to fill the questionnaire but not completing it as they find it lengthy.

Box 2.5. Public Procurement Survey of Suppliers 2020 in Scotland

Between 2 November and 11 December 2020, le Government of Scotland carried out a survey of suppliers to the public sector in Scotland. The survey aimed to gather the views and experiences of suppliers in relation to several strategic topics of importance to the Scottish public sector procurement.

In total, it contained 67 questions covering a range of topics such as:

suppliers’ experiences of the bidding process and of delivering contracts (including subcontracting work);

training;

support and advice around tendering;

barriers to bidding and delivering contracts; and

the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on suppliers.

In total, 1 556 responses were received.

The feedback gathered through the survey and the analysis of the responses presented in a report were used to inform future thinking on the delivery of public procurement in Scotland. The findings were invaluable in helping to identify those areas of policy and practice where Scotland is doing well and to understand the impact of recent changes. More importantly, the results also identified areas where Scotland could be doing more – or doing things differently – to maximise the impact of public procurement and to ensure the delivery of public services that are high quality, continually improving, efficient and responsive to local people’s needs.

In order to maximise the number of responses, a multi-faceted approach was adopted to promoting the survey. This involved issuing survey invitations to suppliers registered on Public Contracts Scotland (PCS) and key stakeholders from business representative groups, including the construction sector. The survey was also publicised on the Scottish Procurement social media platforms and also through stakeholder groups – in particular, the Procurement Policy Forum, the Public Procurement Group, the Procurement Supply Group and the Supplier Development Programme.

Considering the frequency of launching surveys

Preparing, launching, disseminating, and assessing the answers of a survey is a heavy exercise both for the entity in charge of administering the survey and for those that are required to respond. As this is an exercise that should be repeated over time in Hungary, the PMO should consider fixing the frequency of launching surveys.

As mentioned earlier, surveys targeting different stakeholders are used on the one hand to calculate indicators but also to gather additional information to assess some indicators that are more of a descriptive nature and that might not substantially change from one year to the other (i.e. capacity within contracting authorities, cost of bidding, cost of procedures). It is therefore recommended to the Hungarian government to not launch these surveys on an annual basis and to devote more efforts to further disseminate these surveys in future editions.

Regarding the questionnaires sent to CPBs, given that CPBs represent an important share of public procurement spending in the country, it is recommended to launch the dedicated questionnaires on an annual basis while working in parallel in integrating CPB systems with EKR, the national e-procurement system.