Since the adoption of the Paris Agreement, LAC countries strengthened their climate action, but with different policy approaches. Mexico, Colombia, Chile and Argentina rely primarily on market-based instruments such as carbon pricing and subsidies, and feed-in tariffs for renewable energy; while others (Costa Rica and Peru) rely primarily on non-market-based instruments, such as minimum energy performance standards and bans or phase-outs of fossil-fuel equipment or infrastructure. Despite this progress, there is room for increased action and greater policy stringency.

Although LAC countries expanded the use of environmentally related taxes, the revenue they raise remains modest (0.9% of GDP in 2020, less than half the OECD average of 2.1%). As in most other countries, the bulk of revenue is raised from taxing energy, in particular motor fuels, and transport.

LAC countries have increased their use of carbon pricing, through fuel excise duties, and in some cases (Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Uruguay), through explicit carbon taxes. In 2021 average net effective carbon rates were relatively low in most LAC countries. Costa Rica had the highest net ECR at EUR 47 per tCO2e, followed by Jamaica at EUR 32.4 and Mexico at EUR 19.9.

The highest net ECR is applied to the road transport sector, reaching, for example, EUR 121.8 per tCO2e in Uruguay and EUR 116 in Costa Rica. Off-road transport and agriculture are the next most priced sectors, up to EUR 81.6 per tCO2e and EUR 83.4 in Costa Rica, respectively.

The share of GHG emissions priced varies from 80% in Jamaica to less than 20% in Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Uruguay and Paraguay. All road transport emissions are subject to a positive net ECR in most LAC countries. Seven LAC countries price all emissions from off-road transport and agriculture and four countries price more than 98% of emissions from electricity generation.

The revenue potential from increasing effective carbon prices and reforming fossil fuel support goes from less than 0.3% of GDP in Costa Rica, to above 3% of GDP in Argentina, Ecuador and Jamaica. This is due to higher pre-existing carbon prices or lower fossil fuel subsidies.

Although LAC countries have reduced government support to fossil fuels between 2012 and 2019 (-32%), support more than doubled in 2021 with the rebound of the global economy. Support to fossil fuels is expected to increase further in 2022 as global consumption subsidies are anticipated to increase due to higher fuel prices and energy use.

Scaling up financing instruments, such as green, social, sustainable and sustainability‑linked bonds, debt‑for‑nature swaps, catastrophe bonds, and natural disaster clauses, can also help raise additional revenue to ensure flows of resources target climate action, as well as ESG ratings, Climate Risks Assessments and expenditure and finance taxonomies to complement the implementation of financing instruments.

Countries such as Colombia, Mexico, Brazil, Costa Rica, Peru, the Dominican Republic, Cuba and Ecuador are recipients of aid targeted towards climate change mitigation, adaptation and biodiversity from DAC members. Climate change mitigation received the largest sums, followed by biodiversity and climate change adaptation.

Environment at a Glance in Latin America and the Caribbean

Climate actions and policies

Key messages

Context

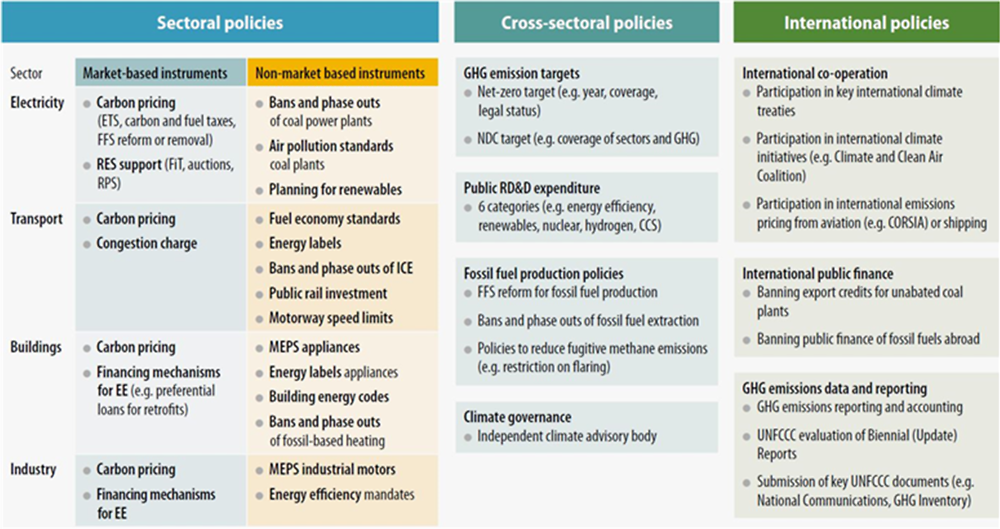

Environmental policy instruments are institutional vehicles through which policy makers implement policy objectives. They provide incentives to control or limit environmentally harmful activities or to promote beneficial ones through pollution abatement and control, cleaner technologies and innovation, and input or product substitution. They often operate as part of a “mix” where several instruments are applied to the same environmental issue to enhance their effectiveness and economic efficiency.

The transition to net-zero involves using the right policy levers and a combination of market-based and non-market-based instruments that is consistent with countries’ specific circumstances (see Box 4). Governments must align their climate objectives and actions across different policy domains including transport, housing, construction, spatial planning, agriculture and development co-operation. This is essential to ensure that other policies and measures do not hamper the effectiveness of climate policies, for example by providing support to fossil fuels. Governments must also consider the synergies between emission reduction and adaptation strategies, and the synergies with other environmental and broader well-being objectives such as biodiversity, cleaner air and improved health. Climate policies that are integrated with actions to reduce poverty and vulnerability are particularly important in the LAC region.

Progress and performance can be assessed by relating information on policies and policy instruments to their outcomes in terms of GHG emission reductions, improvements in air quality and biodiversity, and resilience to climate shocks, as well as by reviewing other non-environmental policy instruments for their unintended negative environmental impacts.

This section gives an overview of climate actions and policies in a subset of LAC countries where information is available, drawing on data from International Programme for Action on Climate. It also presents selected indicators on policy instruments for which data are available for most LAC countries: environmentally related taxes, net effective carbon rates and official development assistance for climate. The indicators displayed do not provide a complete overview of countries’ policies and policy mixes to achieve their climate-related objectives and their interpretation should consider the country specific contexts.

Box 4. Market-based and non-market-based policy instruments

Market-based instruments operate by affecting the relative prices of goods to incentivise or disincentivise certain behaviour, such as taxes, subsidies, emission trading schemes and climate finance instruments. Non-market-based instruments operate by providing mandates or standards to be enforced legally or through penalties, such as emission standards and permits, or by influencing behaviour indirectly through targets, information and education campaigns, and certification systems. These include instruments that are adopted to intentionally mitigate climate change and those that are adopted for other purposes (e.g. safety, energy affordability) but have effects on GHG emissions. Many of these instruments apply to economic activity sectors, the sub-national level and cities. Examples include the following:

Governments can tax and subsidise in a way that drives decarbonisation, for instance by applying carbon taxes and cutting fossil fuel support that undermines the effectiveness of environmental policies.

Governments can invest in innovation and new technology, efficient energy systems, resilient infrastructure and sustainable food and transport systems.

Governments can regulate to control emissions and lead the way with greener public procurement.

Governments can implement educational programmes and information campaigns to raise awareness and encourage businesses and consumers to act.

Overview of climate policies

Recent developments

It has been estimated that a 2.5°C global warming scenario could cost LAC between 1.5% and 5.0% of its GDP by 2050 (ECLAC, 2015[53]). Accelerated climate action is therefore needed. It should focus on measures to incentivise clean energy and energy efficiency, phasing-out fossil fuel subsidies and other support measures, decarbonising the transport sector, and reducing deforestation (OECD et al., 2022[5]).

The OECD has developed a monitoring framework and database to track climate mitigation policies across countries, called the Climate Actions and Policies Measurement Framework (CAPMF). It covers a subset of LAC countries, including Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Mexico and Peru (Box 5). These countries strengthened their climate action between 2015, when the PA was adopted, and 2020 in terms of both policy adoption and policy stringency, although individual countries progressed at different paces.

The number of policies adopted increased. The countries which have seen the largest increase in policy adoption are Argentina and Colombia, that introduced 9 and 7 new policies, respectively. In absolute terms, Mexico has the largest number of policies, boasting 35 (out of 56 policies covered by the CAPMF) registered policies in 2020, followed by Chile with 27, Argentina, Brazil and Colombia with 24, Costa Rica with 16 and Peru with 13 policies.

Some countries rely primarily on market-based instruments, such as Mexico, Colombia, Chile and Argentina where carbon pricing and subsidies and feed-in tariffs for renewable energy abound. Other countries, such as Costa Rica and Peru, rely primarily on non-market-based instruments, such as minimum energy performance standards and bans or phase-outs of fossil-fuel equipment or infrastructure.

While policy coverage and policy stringency do not measure effectiveness, they provide an initial assessment. In LAC, despite progress made since 2015 and the long-term ambition announced by many countries, policies and actions on climate remain insufficient. There is space for countries to enhance the effectiveness of their policy mixes and to strengthen policy stringency, defined as the degree to which climate actions and policies incentivise or enable GHG emissions mitigation at home or abroad.

Since countries have different emission profiles, drivers, and socio-economic constraints, there is no one-size-fits-all policy approach. Differences between countries reflect the complex interactions between climate ambitions, pre-existing conditions, political and institutional constraints and social preferences. At the same time, in an interconnected world, differences in climate ambition and policy adoption can lead to competitive disadvantages for ambitious countries, which ultimately may slow down climate action (Figure 29). Countries must choose the best policy mix and instruments for effective climate action in the context of their national circumstances. A whole-of-government approach dealing with economic development and poverty issues may be necessary to overcome institutional and socio-economic barriers.

Box 5. The Climate Actions and Policies Measurement Framework (CAPMF)

The CAPMF is a harmonised climate-mitigation policy database. It was developed by the OECD under the International Programme for Action on Climate) as part of a broader effort to develop indicators to support evidence-based policy analysis and government decision-making in the climate change policy-sphere. The CAPMF can help countries monitor climate actions and support national and international policy analysis.

The CAPMF includes climate mitigation actions and policies coherent with UNFCCC and IPCC frameworks. It is the most comprehensive, harmonised climate policy database to support countries to implement their NDCs and enable analysis on policy effectiveness. It covers:

1. Broad range of policies: 128 policy variables, grouped into 56 policy instruments and other climate actions.

2. Country Coverage: 51 countries and EU27, accounting for 85% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, including: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Mexico, and Peru.

3. Time Series: 2000-2020 period.

All data are publicly available. Policymakers and practitioners can explore the data and the policy insights at https://oecd-main.shinyapps.io/climate-actions-and-policies/.

Figure 31. Climate Actions and Policies Measurement Framework

Environmentally related taxes and financial instruments

Recent trends and developments

The LAC region faces the challenge of financing the green transition under a tight fiscal space. In addition there is a risk of reduced future income due to the region’s dependence on exports of GHG intensive products whose demand is projected to shrink over the next two decades (UNDP, 2022[54]). Governments thus need to find new ways to mobilise additional revenues. One approach is to implement instruments that simultaneously incentivise behavioural change and that can capture additional income, such as environmentally‑related taxes, emission trading systems (ETS) and other financial instruments.

Tax revenue in LAC countries remains low, accounting for about 21.9% of GDP in 2020, compared to 33.5% in the OECD (OECD et al., 2022[5]). This gap is explained by the region’s relatively low revenue from income taxes and social security contributions (OECD et al., 2022[5]). Environmentally related taxation provides an alternative income source to increase tax revenue and achieve environmental objectives. In recent years, LAC countries made increasing use of environmentally related fiscal instruments. Mexico introduced a carbon and fertiliser tax, Colombia a tax on plastic bags, Chile a carbon tax and a tax on local air pollution. These are positive developments. However, there is room for increasing the rates and broadening the coverage of these instruments. Revenue from environmentally related taxes in LAC amounted to only 0.9% of GDP on average in 2020, less than half the OECD average of 2.1% of GDP. As in most countries, the bulk of the revenue is raised from taxing energy, in particular motor fuels, and transport; pollution and resource tax bases play a minor role (Figure 32; Figure 33).

Furthermore, scaling up tools of debt, such as green, social, sustainable and sustainability‑linked (GSSS) bonds, debt‑for‑nature swaps, catastrophe bonds, and natural disaster clauses, can also help raise additional revenue and ensure flows of resources target climate action. The GSSS market in the region reached an accumulated USD 73 billion from 2014 to September 2021, of which green bond issuance accounted for USD 31 billion, followed by social with USD 17 billion (OECD et al., 2022[5]). Other measures such as Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) ratings, Climate Risks Assessments and expenditure and finance taxonomies, increasingly adopted in the region, can support and encourage the implementation of such instruments (S&P Global, 2022[55]).

Comparability, interpretation and data availability

Environmentally related taxes can have important environmental impacts even if they raise little (or no) revenue. However, indicators on environmentally related taxes should be used with care when assessing the “environmental friendliness” of the tax systems. For such analyses, additional information, describing the economic and taxation structure of the country, is necessary. For example, information on revenue from fees and charges, and from royalties related to resource management may be relevant but is not included.

Comparisons of environmentally related tax revenue provide a useful starting point for analysing the impact of environmental taxation, however, comparing only the levels of revenue does not provide the full picture of a country’s environmental policy, as it does not provide information on tax rates, exemptions or coverage. The OECD Policy Instruments for the Environment (PINE) database provides additional information on tax rates and exemptions, allowing a more comprehensive assessment of the environmental impacts of these taxes. In addition, governments may choose to implement environmental policy using a range of other instruments, including fees and charges, expenditures (both direct and subsidies) and regulation, some of which are also detailed in the PINE database (see http://oe.cd/pine for information on the use of alternative instruments in countries).

Carbon pricing

Recent trends and developments

Carbon pricing is an important policy instrument that encourages decarbonisation efforts and can accelerate the transition to net-zero. As part of their efforts to cut GHG emissions, LAC countries have increased their use of carbon pricing through the implementation of carbon taxes. Although considered by many LAC countries, Emission Trading Systems are yet to be implemented. Most countries, however, have adopted carbon pricing implicitly using fuel excise taxes. A good measure of carbon pricing is effective carbon rates (ECR) that consider the price on carbon emissions arising from fuel excise taxes, carbon taxes, and tradeable carbon emission permits. In the region, effective carbon pricing is most commonly applied in the road transport sector, followed by agriculture and fisheries, off-road transport, industry, buildings and the electricity sector.

Explicit carbon rates

Explicit carbon taxes have only recently been implemented in the region, at low rates and with limited coverage. Chile applies an explicit carbon tax of EUR 4.18 per tCO2e to power generation, but does not tax the transport and building sectors, this implies an average explicit carbon tax of EUR 1.40 per tonne of CO2, for all national emissions, which is the highest in the region. Argentina, Colombia and Mexico apply explicit carbon taxes mainly in the transport and agriculture sectors, with average explicit carbon taxes of EUR 0.73, EUR 0.79 and EUR 1.16 respectively over their total national emissions. These differences stem mostly from differences in taxation levels across different energy products which in turn have different emissions coverage. In 2022, Uruguay framed its fuel tax as an explicit carbon tax in the transport sector, which has not yet been reflected in the data shown in this section.

Effective carbon rates

The OECD also estimates Net ECR that account for government measures that decrease pre-tax prices through direct budgetary transfers (i.e. fossil fuel subsidies) (Figure 34) (OECD, 2022[56]). This helps refine estimates of market incentives for decarbonisation. Net ECR estimates are available for 14 LAC countries.

In most LAC countries, average net ECR are relatively low compared to OECD countries and well below the EUR 30 per tonne of CO2 benchmark,1,albeit higher than explicit carbon taxes. In 2021, Costa Rica had the highest net ECR at EUR 47 per tCO2e, followed by Jamaica at EUR 32.4 and Mexico at EUR 19.9 (Figure 34). Variations across sectors are significant. The highest net ECR is applied to the road transport sector, reaching, for example, EUR 121.8 per tCO2e in Uruguay and EUR 116 in Costa Rica. Off-road transport (i.e. pipelines, rail transport, aviation and maritime transport) and agriculture are the next most priced sectors, up to EUR 81.6 per tCO2e and EUR 83.4 in Costa Rica, respectively.

The share of emissions covered by carbon pricing is also relevant to assess the potential impact of these instruments. For example, 79.6% of GHG emissions in Jamaica are subject to a positive net ECR, the highest in the region, followed by 56% of emissions covered in Chile, 46% in Costa Rica and 42% in Mexico. In Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Uruguay and Paraguay, less than 20% of emissions are priced (Figure 35)

These national averages mask sectoral differences. All road transport emissions are subject to a positive net ECR in most LAC countries. Seven LAC countries price all emissions from off-road transport and agriculture and four countries price more than 98% of emissions from electricity generation. The country with the largest fossil fuel subsidies is Ecuador, where subsidies provided to the building, transport (road and off-road), agriculture, fisheries and electricity sectors, resulted in a negative carbon price of EUR -17 per tCO2e.

Governments can increase carbon prices through the introduction of new carbon taxes, increases in carbon tax rates, the phasing out of carbon tax reductions or exemptions, or by increasing the stringency of minimum standards for carbon price benchmarks.

Revenue potential from carbon taxation and reform of support to fossil fuels

The revenue foregone from adopting carbon taxation can be estimated as the difference between actual revenue (calculated from prices paid applied to their emissions base) and the potential revenue raised if all emissions were priced at three benchmarks rates (EUR 30, EUR 60, EUR 120) consistent with different decarbonisation scenarios and climate goals (Marten and van Dender, 2019[57])

The revenue potential from increasing effective carbon prices to the EUR 120 carbon benchmark differs substantially across countries. Higher pre-existing carbon prices (or lower fossil fuel subsidies) reduce the remaining revenue potential from pricing carbon to a given benchmark. As a result, some countries would raise revenue of less than 0.3% of GDP (e.g. Costa Rica), while others could raise revenue above 3% of GDP (e.g. Argentina, Ecuador and Jamaica) (Figure 37). Source: OECD (2022), Pricing Greenhouse Gas Emissions: Turning Climate Targets into Climate Action, OECD Series on Carbon Pricing and Energy Taxation, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/e9778969-en.

Figure 37. indicates the incremental revenue potential of more modest reform options, starting from reforming fossil fuel subsidies (removing negative carbon prices), followed by raising prices to a carbon benchmark of EUR 60. Higher revenue from carbon pricing could be used to provide targeted support to improve energy access and affordability, enhance social safety nets, and support other economic and social priorities.

Reforming government support to fossil fuels is an important lever for decarbonising the economy and mitigating greenhouse gas emissions. In addition to freeing substantial fiscal resources, these reforms could improve price signals to accelerate the development of lower carbon alternatives. The range of government interventions that can ultimately encourage the production or consumption of fossil fuels is very broad. As documented in the OECD Inventory of support measures for fossil fuels, Argentina, Chile, Colombia, and Mexico have all seen an increase in the amount of fossil fuel subsidies since 2016.

In Argentina, Chile and Colombia, most of support is waived in the form of direct transfers, whereas in Brazil, Costa Rica and Mexico, support is provided through the tax code in the form of tax expenditures. Most other LAC countries support fossil fuels through induced transfers (i.e. market regulation and price support for lower end-user price relative to the full cost of supply). The largest amount of government support is directed towards the production and consumption of petroleum (OECD, 2023[58]). LAC countries have reduced (by 32%) government support to fossil fuels between 2012 and 2019, however, they more than doubled in 2021 compared to 2020 as energy prices rose with the rebound of the global economy. They are expected to have further increased as global consumption subsidies were anticipated to skyrocket in 2022, due to higher fuel prices and energy use (IEA, 2023[59]).

Comparability, interpretation and data availability

The OECD has estimated effective carbon rates (ECR) net of pre-tax support measures for fossil fuels. ECR estimate the price on carbon emissions arising from fuel excise taxes, carbon taxes, and tradeable carbon emission permits; they do not account for government measures that decrease pre-tax prices of fossil fuels. Direct budgetary transfers are one example of such measures. They are often provided to users to alleviate fuels costs and take the form of reimbursements to final consumers or to energy suppliers to compensate a (below-market) regulated price that ultimately benefits final consumers. By effectively reducing pre-tax fossil fuel prices, they act as a negative carbon price. This support type has been integrated to the ECR framework to construct effective carbon rates net of pre-tax direct transfers – i.e. Net ECR indicators. Only 14 LAC countries are analysed in the Net ECR database. However, it does provide a guide to progress in the region and suggests a way forward for dealing with data gaps.

Official Development Assistance

Recent developments

In 1992, at the Earth summit in Rio de Janeiro, three environmental conventions were established: the UNFCCC, the CBD and the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification. Country parties committed to assist developing countries in the implementation of the Rio Conventions.

The OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) is an international forum gathering 31 of the largest aid providers, with the mandate to contribute to the implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The OECD-DAC Statistical system monitors the streamlining of the objectives of the Rio conventions and of environmental objectives in development co-operation activities through a set of Rio markers on biodiversity, climate change adaptation, and climate change mitigation. LAC countries receive aid from DAC donors, whereby climate change mitigation is prioritised with the largest sums, followed by biodiversity and climate change adaptation. A scoring system of three values is used, in which development co-operation activities are “marked” as targeting the environment or the Rio Conventions as the “principal" objective or a “significant" objective, or as not targeting the objective. Considering both aid that principally and significantly target these environmental aims, Colombia stands out as a principal recipient of DAC aid, followed by Mexico, Brazil, Costa Rica, Peru, the Dominican Republic, Cuba and Ecuador.

At the 15th Conference of Parties of the UNFCCC in Copenhagen in 2009, developed countries committed to a collective goal of mobilising USD 100 billion per year by 2020 for climate action in developing countries, in the context of meaningful mitigation actions and transparency on implementation. USD 83.3 billion was provided and mobilised by developed countries for climate action in developing countries in 2020. While increasing by 4% from 2019, this was USD 16.7 billion short of the USD 100 billion per year by 2020 goal (OECD, 2022[60]).

Between 2016 and 2020, mitigation finance accounted for 73% of total climate finance provided and mobilised in Americas, while adaptation finance represented 18%. Public finance was mainly provided in the form of loans (81% of total public finance for climate) while 17% war provided as grants. Grants typically support capacity building, feasibility studies, demonstration projects, technical assistance, and activities with low or no direct financial returns but high social returns. Public climate finance loans are often used to fund mature or close-to mature technologies as well as large infrastructure projects with a future revenue stream, which are predominant for mitigation finance as well as in middle-income countries (OECD, 2022[60]).

About 26% of private climate finance was mobilised for the Americas. Almost two-thirds (64%) of private climate finance mobilised for Small Island Developing States was allocated to the countries and territories in the Caribbean region (OECD, 2022[60]). The ability of donor countries to mobilise private finance for climate action in developing countries is influenced by the composition of bilateral and multilateral providers’ portfolios (mitigation-adaptation, instruments and mechanisms, geography, and sectors), policy and broader enabling environments in developing countries, as well as general macroeconomic conditions. Adaptation continued to represent a small share of total private climate finance mobilised. In contrast to many mitigation projects, notably in the energy sector, adaptation projects often lack the revenue streams needed to secure large-scale private financing. It is also challenging to mobilise private finance for activities that increase the resilience of smaller actors, e.g. small enterprises, and farmers.

Comparability, interpretation and data availability

A large majority of activities targeting the objectives of the Rio Conventions fall under the DAC definition of "aid to environment". The Rio markers permit their specific identification. The same activity can be marked for several objectives, e.g. climate change mitigation and biodiversity. These overlaps reflect that the three Rio Conventions are interlinked and mutually reinforcing. However, care needs to be taken not to double-count the amounts when compiling the total for aid in support of more than one Convention: biodiversity-, climate change- and desertification-related aid should not be added up as this can result in double or triple-counting.

Note

← 1. EUR 30/tonne of CO2 represents a historic low-end price benchmark of carbon costs in the early and mid-2010s, consistent with a slow decarbonisation scenario by 2060; EUR 60/t represents a low-end 2030 and mid-range 2020 benchmark according to the High-Level Commission on Carbon Prices. EUR 120/t represents a central estimate of the carbon price needed in 2030 to decarbonise by mid-century under the assumption that carbon pricing plays a major role in the overall decarbonisation effort.