Public policy evaluations allow lessons to be drawn from the crisis in order to strengthen the future resilience of countries. This chapter presents the analytical and methodological framework for the evaluation that forms the basis of this report. It also presents the structural strengths and weaknesses present in Luxembourg that may have impacted the margin for manoeuvre that the government had when facing the crisis. It ends with a brief overview of the main measures adopted by Luxembourg at the beginning of the crisis.

Evaluation of Luxembourg's COVID-19 Response

1. Evaluating the response to the COVID-19 crisis in Luxembourg

Abstract

1.1. Introduction

Responding to the crisis has presented an unprecedented challenge for most Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) member countries, due to both the magnitude of the crisis and the severity of its impact on health, the economy, educational continuity and the well-being of citizens more generally. In response to this situation, OECD member countries have deployed significant human, financial and technical resources in a relatively short period of time to manage and mitigate the consequences of the crisis. Luxembourg is no exception.

Two and a half years into the pandemic, this report aims to draw lessons from this period in order to strengthen the country's future resilience. This evaluation thus aims to provide an understanding of what worked and what did not work, for whom and why in Luxembourg's response to COVID-19. This report builds on the OECD's work on government evaluations of COVID-19 responses, and is based on a mixed method to ensure that its results are robust. The assessment therefore focuses on a set of evaluative criteria in order to provide a comprehensive understanding of the public value chain in responding to the crisis. In order to answer all of these evaluative questions, while taking into account the context in which the Luxembourg government operates, this chapter first provides a methodological framework, before examining the country's structural strengths and presenting an overview of the measures adopted to address the crisis.

1.2. How can the response to the COVID-19 crisis be evaluated?

1.2.1. This report is part of the OECD's work on evaluations of COVID-19 responses

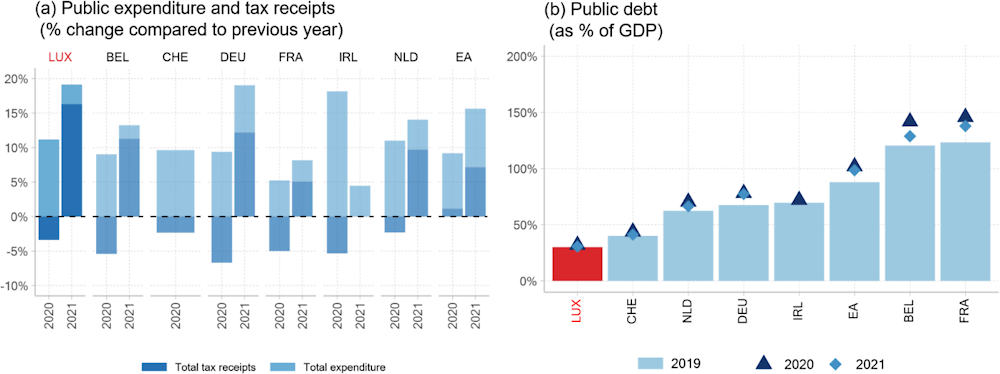

The OECD's work on government evaluations of COVID-19 responses identifies three types of measures that countries should assess to better understand what worked and what did not work in their response to the pandemic (OECD, 2022[1]) (see Figure 1.1):

Pandemic preparedness: measures taken by governments to anticipate a pandemic before it occurs and to prepare for a global health emergency with the necessary knowledge and capacity (OECD, 2015[2]).

Crisis management: policies and actions implemented by the public authorities in response to the pandemic once it has materialised, to co-ordinate government action across government, to communicate with citizens and the public, and to involve the whole-of-society in the response to the crisis (OECD, 2015[2]).

Response and recovery: policies and measures implemented to mitigate the impact of the pandemic and the resulting economic crisis on citizens and businesses, support economic recovery and reduce well-being losses. These measures include lockdowns and other restrictions to contain the spread of the virus, as well as financial support for households, businesses and markets to mitigate the impact of the downturn, health measures to protect and care for the population, and social policies to protect the most vulnerable.

Figure 1.1. Framework for evaluating measures taken in response to COVID-19

Note: These phases are presented as a circle because they are not necessarily chronological.

Source: OECD (2022[1]), "First lessons from government evaluations of COVID-19 responses: A synthesis", OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/483507d6-en.

These three types of measures correspond to the main phases of the risk management cycle, as defined in the OECD Recommendation of the Council on the Governance of Critical Risks (OECD, 2014[3]). The empirical relevance of this evaluation framework, presented in Figure 1.1, is also proven by analysis of the first available government evaluations (OECD, 2022[1]) (see Box 1.1 for more information on this study).

Box 1.1. OECD work on government evaluations of COVID-19 responses

The OECD publication “First lessons from government evaluations of COVID-19 responses” summarises the key lessons learned from evaluations produced by OECD member country authorities during the first 15 months of the pandemic response. To this end, 67 evaluations from 18 OECD member countries were analysed.

To identify key lessons from these evaluations, the OECD Secretariat conducted a qualitative and systematic content study, identifying recurring themes through coding and a quantified approach. This analysis shows that the vast majority of evaluations in the sample address one or more of the three major phases of risk management as defined by the OECD Recommendation on the Governance of Critical Risks: pandemic preparedness, crisis management, and response and recovery.

In addition, initial assessments show that many countries have reached similar conclusions, allowing for several important findings that can not only be factored into strategies currently being implemented in the wake of the COVID-19 crisis, but also help to build countries' resilience in the future. In particular, the conclusions that emerge from the evaluations studied are:

Overall, pandemic preparedness was inadequate, especially considering the enormous human and financial cost of global health crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Countries acted both quickly and massively to mitigate the economic and financial consequences of the pandemic, but will need to monitor the longer-term fiscal costs of doing so.

There can be no trust without transparency, which requires regular and targeted crisis communication, but above all the involvement of stakeholders and the public in risk-related decision making.

Source: OECD (2022[1]), "First lessons from government evaluations of COVID-19 responses: A synthesis", OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/483507d6-en.

1.2.2. This evaluation is based on robust qualitative and quantitative data

Firstly, this evaluation uses comparative data taken from the OECD's work on government evaluations of COVID-19 responses (OECD, 2022[1]). Indeed, this work provides an overview of what has and has not worked, for whom and why on these three types of measures in 18 OECD member countries.

These comparative data, which provide a general international framework, are complemented by two surveys conducted to collect country-specific evaluation data. The first survey was administered to the authorities of the central government of Luxembourg responsible for implementing the various measures to control the pandemic. A second survey was administered to the local actors who had a key role in the response to the crisis: the 102 municipalities and cities, the 171 primary education institutions and the 4 hospitals. Other OECD multi-country survey data were used where relevant; for example, a survey on health system resilience to COVID-19 was used in Chapter 3 on the resilience of Luxembourg's health sector. Administrative microdata were also used in the analysis of the impacts that the pandemic had on the economy and the labour market in Chapters 6 and 7. An anonymous form containing these microdata was made available to the OECD teams by the National Institute for Statistics and Economic Studies of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg (STATEC) and the General Inspectorate of Social Security of Luxembourg.

These quantitative data were also cross-referenced with qualitative interviews with key stakeholders in crisis management at the national and local levels. The institutions met by the OECD teams were identified jointly by the OECD and the Ministry of State. The OECD teams were able to meet with a wide range of stakeholders, including ministries, representatives from communes and schools, the health sector (hospitals and medical centres), deputies, representatives of civil society (trade unions, the Red Cross, Caritas, and ASTI, an organisation promoting integration and inclusion in Luxembourg), the Consultative Human Rights Commission, private laboratories, the Patiente Vertriedung patients' association, the Syndicat des Pharmaciens or Union of Pharmacists, the Cercle des Médecins Généralistes or Society of General Practitioners, the Association des Médecins et Médecins Dentistes or Association of Doctors and Dentists, employers' associations (Luxembourg Employers' Association, Luxembourg Confederation of Commerce, Chamber of Skilled Trades and Crafts, Federation of Luxembourgish Industrialists), the Confédération des Organismes Prestataires d'Aides aux Services or Confederation of Organisations Providing Assistance to Services], the Ligue Luxembourgeoise d'Hygiène Mentale or the Luxembourg Association for Mental Health, and the Economic and Social Council of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg.

1.2.3. The evaluation analyses the measures adopted by Luxembourg, their implementation processes and the results obtained

In order to understand what was and was not successful in the preparation for and response to the COVID-19 pandemic in Luxembourg, this report aims to assess and draw lessons from the relevance, coherence, effectiveness, efficiency, impact and sustainability of the measures put in place during the three risk management phases (see Box 1.2 for an explanation of these different criteria).

Box 1.2. Evaluation criteria of the Development Assistance Committee

The OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) has become the main benchmark body for evaluating projects, programmes and policies in all areas of public action. Each criterion represents a different filter or perspective through which the intervention can be analysed.

Taken collectively, these criteria play a normative role. Together, they describe the characteristics expected of all interventions: that they are appropriate for the context, that they are consistent with other interventions, that they achieve their objectives, that they produce results economically, and that they have lasting benefits.

Relevance: the extent to which the interventions’ objectives and design respond to beneficiaries’ needs and priorities, align with national, global and partner/institutional policies and priorities, and remain relevant even as the context changes.

Coherence: the extent to which the interventions are consistent with other interventions being carried out within a country, sector or institution.

Effectiveness: the extent to which the interventions achieved, or are expected to achieve, their objectives and their results, including differential results across groups.

Efficiency: the extent to which the interventions deliver, or are likely to deliver, results in an economic and timely way.

Impact: the extent to which the interventions have generated or are expected to generate significant positive or negative, intended or unintended, higher-level effects.

Sustainability: the extent to which the net benefits of the interventions continue or are likely to continue.

Source: OECD (2021[4]), Applying Evaluation Criteria Thoughtfully, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/543e84ed-en.

In particular, Chapter 2 of this report analyses the relevance and effectiveness of the risk anticipation and preparedness measures established in Luxembourg before the crisis. Chapter 3 looks at the relevance, coherence, effectiveness and efficiency of the government crisis management mechanisms. The following chapters assess the effectiveness, efficiency, impact and sustainability of the public health measures (Chapter 4), education measures (Chapter 5), economic and fiscal policies (Chapter 6) and social policies (Chapter 7) adopted by Luxembourg in response to the pandemic crisis. Table 1.1 summarises the various evaluation questions that this report attempts to answer.

Table 1.1. The evaluation questions addressed in this report

|

Evaluation criterion |

Evaluation question |

Pandemic preparedness |

Crisis management |

Response and recovery |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Public health policy |

Education policy |

Economic and fiscal policy |

Social and labour policy |

||||

|

Relevance |

Is the intervention addressing the problem? |

x |

x |

||||

|

Coherence |

Is the intervention aligned with the other interventions ? |

x |

|||||

|

Effectiveness |

Is the intervention achieving its objectives? |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|

Efficiency |

Are resources being used optimally? |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|

|

Impact |

What difference is the intervention making? |

x |

x |

x |

x |

||

|

Sustainability |

Will the benefits last? |

x |

x |

x |

x |

||

Source: Prepared by the author.

To do this, it is important to understand the structural strengths and weaknesses at play in Luxembourg that were likely to affect the government's room for manoeuvre in its response to the crisis and, in particular, the performance of the policies adopted. To this end, this introductory chapter presents the main demographic, geographic, public governance, economic and social issues in Luxembourg that may have affected the government's ability to prepare for, manage and respond to the COVID-19 crisis.

1.3. Understanding the context: What were Luxembourg's strengths and challenges in responding to the crisis?

Several factors can affect a government's ability to deal with a crisis. Firstly, each country has its own particular characteristics, which can pose challenges for policy development and implementation, even in times when democratic life is functioning normally. In the case of a crisis of this magnitude, there are even more of these factors as combating the threats posed by the pandemic required a huge response from the authorities in all areas of public life. As such, to assess a government's response to the crisis, one must first understand the extent to which that government was able to take these factors into account in order to deploy measures appropriate for the national context (these fall under the relevance and coherence criteria).

Moreover, assessing the effectiveness of a given government's response to the crisis requires, among other things, its results to be compared with those of other countries. This comparative analysis cannot be completed without a detailed understanding of the direct and indirect impacts that these political, economic and social factors may have had on measures to mitigate the effects of the pandemic. A small country like Luxembourg, which is very open to the global economy, therefore does not face the same challenges or have the same assets when controlling a pandemic as an island country, for example. In this context, this section presents the particular geographical, demographic, political, economic and social features of Luxembourg that may have represented a challenge or an asset in the face of the crisis.

1.3.1. Luxembourg is a small, multilingual and very open country

Luxembourg is the second smallest country in the European Union (EU) in terms of both surface area (2 586 km2) and population (645 397 inhabitants as at 1 January 2022), after Malta. With 259.4 inhabitants per km2 in 2021, it is among the five countries with the highest population density in the EU and in the OECD, where the average is 38.7 inhabitants per km2 (OECD, forthcoming[5]).

Divided into 12 cantons, the country is composed of two main regions, the more Germanic Oesling in the north, and Guttland bordering France in the south (STATEC, 2021[6]). Although Luxembourgish is the official national language, the country also has French and German as official administrative languages (STATEC, 2017[7]). The country is therefore trilingual and its residents know and use an average of four languages (two-thirds of the working population can speak four or more languages), which is an economic advantage and an integration factor vis-à-vis its main economic partners and neighbouring countries (STATEC, 2017[7]).

In addition to its central European location, it is politically and economically well-integrated. The country shares borders with France, Germany and Belgium and actively promotes cross-border co-operation with its neighbours (France Diplomatie, 2022[8]). Luxembourg is a founding member of the EU and the eurozone, the OECD, NATO and the Benelux countries, among others.

Luxembourg also has a high level of immigration from neighbouring countries and other EU member states. While Luxembourg's population increased by 44% between 2001 and 2021, the share of the population with Luxembourgish nationality fell by 10 percentage points, from 63% to 53%, in the same period (University of Luxembourg, 2021[9]). This immigration comes mainly from French-speaking groups and other groups who speak an EU language (notably Portuguese, Belgian and German nationals). While the country's size and population has undeniably been an asset in terms of managing a crisis of this magnitude insofar as it has facilitated decision making and the implementation of measures, this high degree of openness to and dependence on workers from other countries has been a major challenge for Luxembourg. The country depends on these workers both economically (see Chapters 6 and 7) and to keep its health sector functioning (see Chapter 4). Furthermore, Luxembourg is a relatively densely populated country, which may, in the event of a pandemic, call for special provisions in terms of managing the risks of the disease spreading. Chapter 4 of this report provides more details on the measures adopted by Luxembourg to address this issue, in particular with regard to the policy of large-scale testing and vaccination of the population, and assesses their effectiveness in this context.

1.3.2. The population of Luxembourg is growing and remains young overall

The country has experienced dynamic population growth (European Commission, 2020[10]), averaging 2% over the past five years, compared to an average of 0.6% across all OECD member countries (OECD, forthcoming[5]). Between 2007 and 2016, the population grew by 21%, which is well above the EU average of 2.8% for the same period (STATEC, 2017[7]). This strong growth in Luxembourg's population is mainly due to a high immigration rate. In 2019, international migrants represented 47.4% of the country's population, well above the OECD average of 13.2% (OECD, forthcoming[5]).

This influx of cross-border workers and immigrants over the last two decades is also the reason why Luxembourg's population is relatively young (OECD, forthcoming[5]); the country's population is also proportionally younger than the OECD average. Thus, while 15.6% of the population was under 15 years of age in 2021 (compared to 17.8% on average for OECD member countries in 2020), only 14.4% of the population was over 65 (compared to an average of 17.4% for OECD member countries in 2020) (OECD, forthcoming[5]). Having a relatively small proportion of older people in the population may have been an asset to the country in controlling the pandemic, as this group is typically more vulnerable to the effects of the virus. It is in this context in particular that Luxembourg's positive aggregate COVID-19 mortality rate should be understood (see Chapter 4). However, further analysis of the differential impacts of the pandemic shows that the mortality rate among 80-year-olds is significantly higher in Luxembourg than in other OECD member countries (see Figure 4.3 in Chapter 4). Chapter 4 assesses the measures adopted in care homes for older people with respect to these impacts.

1.3.3. Luxembourg's political system is stable and enjoys a high level of public confidence

Luxembourg's political system has been stable for several decades

Luxembourg, whose official name is the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, is a parliamentary democracy with a constitutional monarchy. The Grand Duke, a hereditary sovereign, is the head of state. Under the 1868 Constitution of Luxembourg (Government of Luxembourg, 1868[11]), he alone exercises the executive power and ensures the execution of laws. In practice, however, executive power is exercised by the government, which is headed by the prime minister. Over the past three decades, Luxembourg's government, which operates on the basis of parliamentary majorities, has largely demonstrated political continuity and stability, although there have been some changes to political leadership and the ruling coalitions (see Table 1.2) (OECD, 2022[12]).

Table 1.2. Governments of Luxembourg between 1992 and 2002

|

Government |

Prime minister |

Term start date |

Term end date |

Parties in the coalition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Santer-Poos II |

Jacques Santer |

9 December 1992 |

13 July 1994 |

CSV, LSAP |

|

Santer-Poos III |

Jacques Santer |

13 July 1994 |

26 January 1995 |

CSV, LSAP |

|

Juncker-Poos |

Jean-Claude Juncker |

26 January 1995 |

4 February 1998 |

CSV, LSAP |

|

Juncker-Poos |

Jean-Claude Juncker |

4 February 1998 |

7 August 1999 |

CSV, LSAP |

|

Juncker-Polfer |

Jean-Claude Juncker |

7 August 1999 |

31 July 2004 |

CSV, DP |

|

Juncker-Asselborn I |

Jean-Claude Juncker |

31 July 2004 |

23 July 2009 |

CSV, LSAP |

|

Juncker-Asselborn II |

Jean-Claude Juncker |

23 July 2009 |

4 December 2013 |

CSV, LSAP |

|

Bettel-Schneider I |

Xavier Bettel |

4 December 2013 |

5 December 2018 |

DP, LSAP, DG |

|

Bettel-Schneider II |

Xavier Bettel |

5 December 2018 |

Term ends in 2023 |

DP, LSAP, DG |

Note: CSV is the Christian Social People's Party. LSAP is the Luxembourg Socialist Workers' Party. DP is the Democratic Party. DG is the Green Party.

Source: OECD (2022[12]), Digital Government Review of Luxembourg: Towards More Digital, Innovative and Inclusive Public Services, OECD Digital Government Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b623803d-en.

This strong political continuity may have been an asset in a context where all sections of society had to work together in a climate of trust.

Legislative power is concentrated in one parliamentary chamber

The legislative power of Luxembourg is exercised by the Chamber of Deputies, a unicameral parliament composed of 60 members or deputies elected for a five-year term by direct universal suffrage, with proportional representation (STATEC, 2021[6]). The Chamber of Deputies votes on bills proposed by the government, or on bills submitted by private members (Government of Luxembourg, 1868[11]). As explained in Chapter 3, in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, Luxembourg having a unicameral legislature allowed its parliament to act in an agile way, and enabled the government to pass the laws it needed to manage the crisis remarkably quickly without having to prolong the state of emergency longer than necessary.

Luxembourg citizens have trust in the institutions and public authorities

Trust in and satisfaction with public authorities and public services in Luxembourg is on average higher than in other OECD member countries, and has remained stable over time (OECD, 2019[13]; OECD, 2021[14]). In 2020, the trust that Luxembourgers had in their government was the fourth highest among OECD member countries, with 78% of citizens saying they trusted their government that year, compared to an OECD average of 51% (OECD, 2021[14]). This trust also extends to the education system (77% of Luxembourgers were satisfied with the country's education system in 2019) (OECD, 2019[13]). In 2019, 80% of Luxembourgers were satisfied with their healthcare system, compared to an average of 70% in OECD member countries (OECD, 2019[13]). Citizens also believe that Luxembourg's public authorities have learned from the crisis and will be better prepared for future public health crises (68% of citizens think their government would be prepared for another pandemic), more so than in all other OECD member countries.

In summary, all the trends show that the public authorities in Luxembourg have largely benefited from the trust of citizens, which is essential for dealing with external shocks the magnitude of the COVID-19 pandemic. This was indeed crucial to ensure the effectiveness of the pandemic containment measures insofar as a lack of trust could have led to citizens not complying with the rules of social distancing and mask-wearing, or not participating in vaccination campaigns. This climate of confidence may also have enabled the government to obtain rapid approval of the measures it proposed from the Chamber of Deputies.

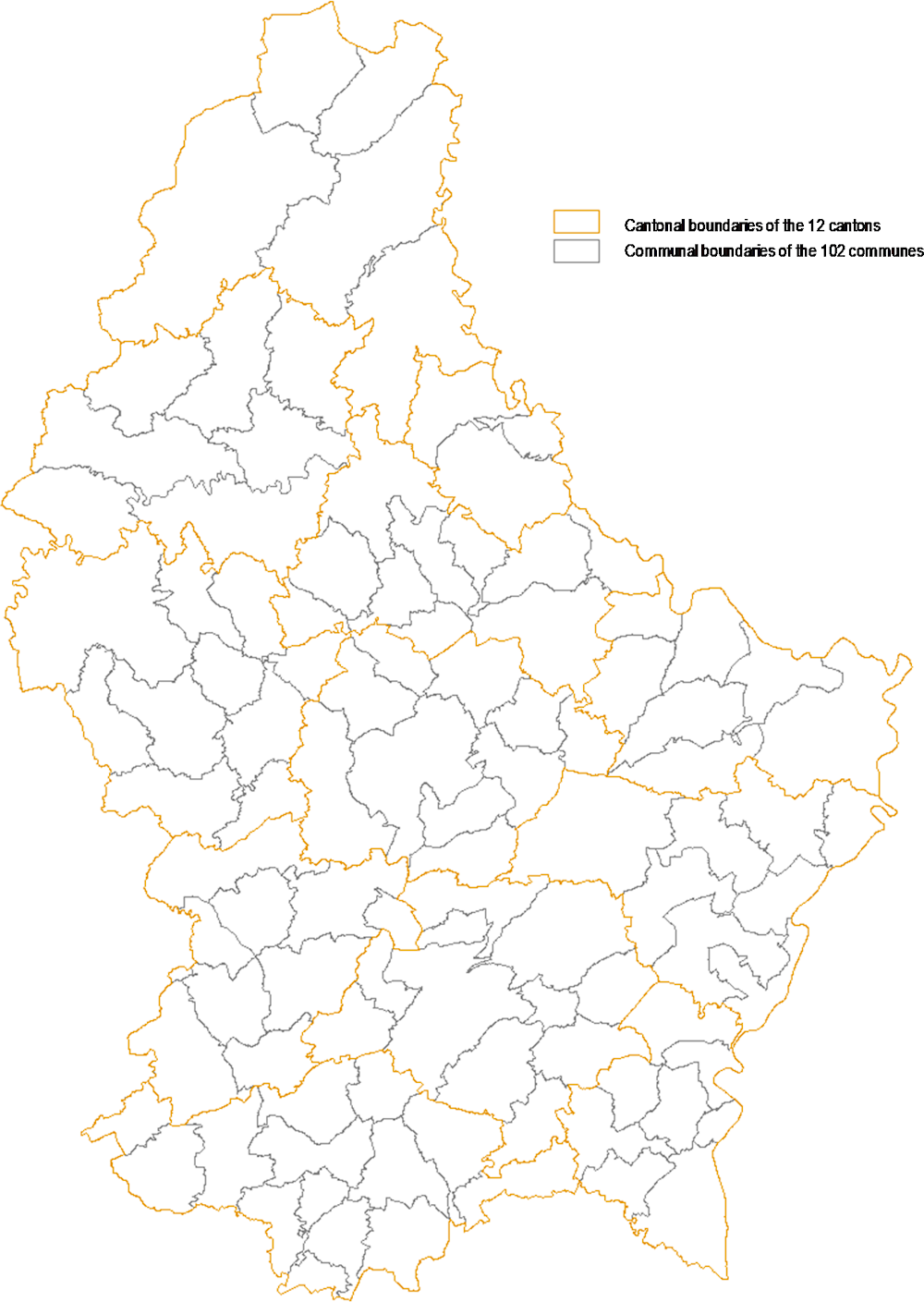

1.3.4. Public governance in Luxembourg is highly centralised

Luxembourg's political and administrative structure is characterised by a high degree of centralisation, although some powers are decentralised to the municipal level. As such, at the local level, Luxembourg's public administration is organised into three districts, 12 cantons and 102 communes, of which 12 have the status of city, with the city of Luxembourg being the largest (Figure 1.2). In reality, however, the 12 cantons have no administrative powers; only the 102 communes have their own powers. Each commune has a deliberative assembly in the form of a communal council, which is elected directly by the inhabitants of the commune in question (Congress of Local and Regional Authorities, 2015[15]). The burgomaster holds the executive power of the commune (Congress of Local and Regional Authorities, 2015[15]).

Figure 1.2. Administrative and territorial organisation of Luxembourg

Source: Luxembourg.

In Luxembourg, municipalities have legal personality, manage their own assets and collect taxes through local representatives, under the control of the central power represented by the Minister for Home Affairs (Information and press services of the Luxembourg government, n.d.[16]). Municipalities autonomously manage municipal interests (records, public services, transportation, health, social welfare, sports, regional economic development and tourism, housing, culture and education), and are consulted by central government on the administration of national policy.

Despite this, power remains highly centralised within central government. This allowed the Luxembourg government to manage the crisis in a generally fast and agile manner (see Chapter 3 for more information on this subject). Municipalities were regularly informed of decisions taken at the national level and served as representatives for the government's actions. However, unlike other OECD member countries where crisis management was shared between the national and local levels, decision making and the implementation of measures has been the exclusive responsibility of central government in Luxembourg. This high degree of centralisation has largely facilitated decision making and the uniform application of measures across the country (see Chapter 3), although countries where responsibility is shared have often also been able to establish unified governance to include both central and local governments (OECD, 2020[17]).

1.3.5. Luxembourg's healthcare system is robust, but faces some structural inequality and risk factors

An effective and efficient health system supported by strong infrastructure

Health outcomes in Luxembourg are generally above the EU average (OECD, forthcoming[5]). In 2015, for example, more than two out of three people believed they were in very good or good health, placing the country among the top 15 European countries in this regard (STATEC, 2017[7]). In addition, while one in three people over the age of 16 reported suffering from a long-term illness or health problem in the 28 EU countries (including the United Kingdom) in 2015, this figure was only 23% in Luxembourg in the same period (STATEC, 2017[7]).This trend has also been reflected during the pandemic: while the prevalence of COVID-19 infections has been high in Luxembourg, the death toll has been much lower than in other OECD member countries. As such, while the prevalence of COVID-19 in Luxembourg is the fourth highest among OECD member countries, this infection rate reflects the country's high capacity to detect COVID-19 infections and the wide variety of testing strategies implemented in the country (see Chapter 4 on health policies during the crisis).

These positive results are set against a background of lower health spending relative to gross domestic product (GDP) than in other OECD member countries. Public and private spending in the Luxembourg health system is lower than in OECD member countries on average and as a percentage of their respective GDPs: in 2019, this spending amounted to 5.4% of Luxembourg's GDP, compared to an average of 8.8% of GDP across all OECD member countries (OECD, forthcoming[5]). This is partly due to the fact that many cross-border workers choose to seek medical care in their own country (OECD, forthcoming[5]). However, the social health insurance system in Luxembourg offers broad access to healthcare (OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2022[18]).

The health system is well resourced with strong infrastructure and a stable workforce. The number of nurses and nursing assistant practitioners is high and increased between 2010 and 2017 (STATEC, 2021[6]). Luxembourg also has the highest number of long-term care beds in facilities and hospitals per capita among the OECD member countries (81.6 per 1 000 inhabitants, compared to 46.6 for all OECD member countries as a whole) (STATEC, 2021[6]). In addition, while intensive care bed capacity doubled during the first wave of the pandemic, no additional beds had to be mobilised (see Chapter 4 of this report).

However, some structural weaknesses in the health system may have presented challenges in the run-up to the crisis

The Luxembourg health system is structurally dependant on people from other countries in terms of healthcare and medical staff, making it vulnerable to border closures during the first COVID-19 lockdown. The share of doctors living abroad but practising in Luxembourg almost doubled between 2008 and 2017, from 15.6% to 26.4% (IGSS, 2021[19]). In 2019, 62% of healthcare professionals and 49% of doctors practising in Luxembourg were living abroad (Lair-Hillion, 2019[20]). Moreover, despite the presence of cross-border workers, Luxembourg has very few doctors compared to other OECD member countries. With approximately 3 doctors per 1 000 inhabitants in 2019, Luxembourg is well below the OECD average (3.6 per 1 000 inhabitants), despite an increase of 39% since 2000 (OECD, 2021[21]). During the pandemic, the country avoided a shortage of healthcare staff thanks to a wide range of measures, including a reserve of health workers that allowed more than 700 professionals to be mobilised during the first wave of infections. However, in a crisis where the international mobility of the population was relatively low, the low density of the city care network could have presented a challenge for relieving congestion in hospitals. For this reason, Chapter 4 recommends that Luxembourg become less dependant on health professionals from other countries and invest more in its health workforce to increase its resilience to future crises.

Health inequalities that affect the less affluent and educated

Health is one of the main inequalities in Luxembourg (obesity, depression, smoking and alcohol consumption): the more educated people are, the better paid they are and the more their health risks are reduced (STATEC, 2017[7]). People's perceptions of good health increase with education and income (STATEC, 2017[7]). In Luxembourg, as in other countries, the proportion of people with chronic conditions also decreases as education levels rise (STATEC, 2017[7]). The share of adults with symptoms of depression also decreases with education level; similarly, these symptoms are, on average, less prevalent among the wealthiest members of the population (STATEC, 2017[7]). In this context, the less educated and less affluent may have been more vulnerable to the effects of COVID-19 in terms of physical and mental health. As such, the results explained in Chapter 4 demonstrate that the elderly and vulnerable sections of Luxembourg's population have been disproportionately affected by the pandemic.

1.3.6. Luxembourg has a unique and very autonomous education system

Luxembourg's unique education system has enjoyed high levels of investment but faces challenges when it comes to equity

In Luxembourg, education is provided to a smaller student population than in the vast majority of OECD member countries. As it stands in 2022, Luxembourg has 170 public fundamental institutions (primary schools and nurseries) and 41 public secondary schools. This population is, nevertheless, multilingual and highly multicultural and the country's three official languages all play a role in the education system.1 Also, given the migratory trends in Luxembourg, the education system (both primary and secondary education) is seeing an increasing number of students whose main language at home is not Luxembourgish.

Annual expenditure per student in schools in Luxembourg is more than twice the OECD average. Despite this high level of spending, Luxembourg performs below the OECD average in all three areas assessed (reading, maths and science) in the Programme for International Student Assessment survey (see Chapter 5 for more information on this subject). Above all, students' socio-economic status is more likely to affect performance in Luxembourg than in most of the OECD member countries, especially in reading (University of Luxembourg, 2021[9]). This context underlines the particular importance for Luxembourg to keep its schools open and to ensure educational continuity in order to prevent these vulnerable populations from dropping out. Chapter 5 of this report highlights the fact that the country stands out for the low number of days that schools were closed, although these efforts did not address all the challenges posed by the crisis.

The education sector has a high degree of autonomy in Luxembourg

The Ministry of Education, Children and Youth has wide-ranging responsibility over the functioning of the Luxembourg education system. It is responsible for early childhood education and care, primary education, secondary education, adult education, and other services related to the care of children in formal education (specialised centres of excellence in educational psychology) and non-formal education formats (crèches and mini-crèches, drop-in centres, school centres, childminders, and youth centres).

The broad responsibilities of the Ministry of Education are conducted with a high degree of autonomy from other government sectors. For example, the Ministry of Education, Children and Youth has its own statistical data collection service. The degree of autonomy enjoyed by the ministry and the breadth of its responsibilities have played a key role during the pandemic, involving significant efforts for co-ordination between central government and the wider education sector (see Chapter 5 for details).

1.3.7. Luxembourg had budgetary room for manoeuvre before the crisis, even if the long-term sustainability of public finances was not certain

Luxembourg's public finances were sound before the crisis

Prior to the crisis, Luxembourg's public finances were relatively healthy, which facilitated the financing of important economic support measures during the pandemic (European Commission, 2019[22]; France Diplomatie, 2022[8]). Luxembourg's public spending amounted to 42.4% of GDP in 2021, compared to 48.5% on average in OECD member countries in 2020 (OECD, forthcoming[5]). The country's public revenues amount to 43.3% of GDP, exceeding the OECD average of 38.1% (OECD, forthcoming[5]). In 2019, the general government balance showed a surplus of about 2.7% of GDP (European Commission, 2020[10]).

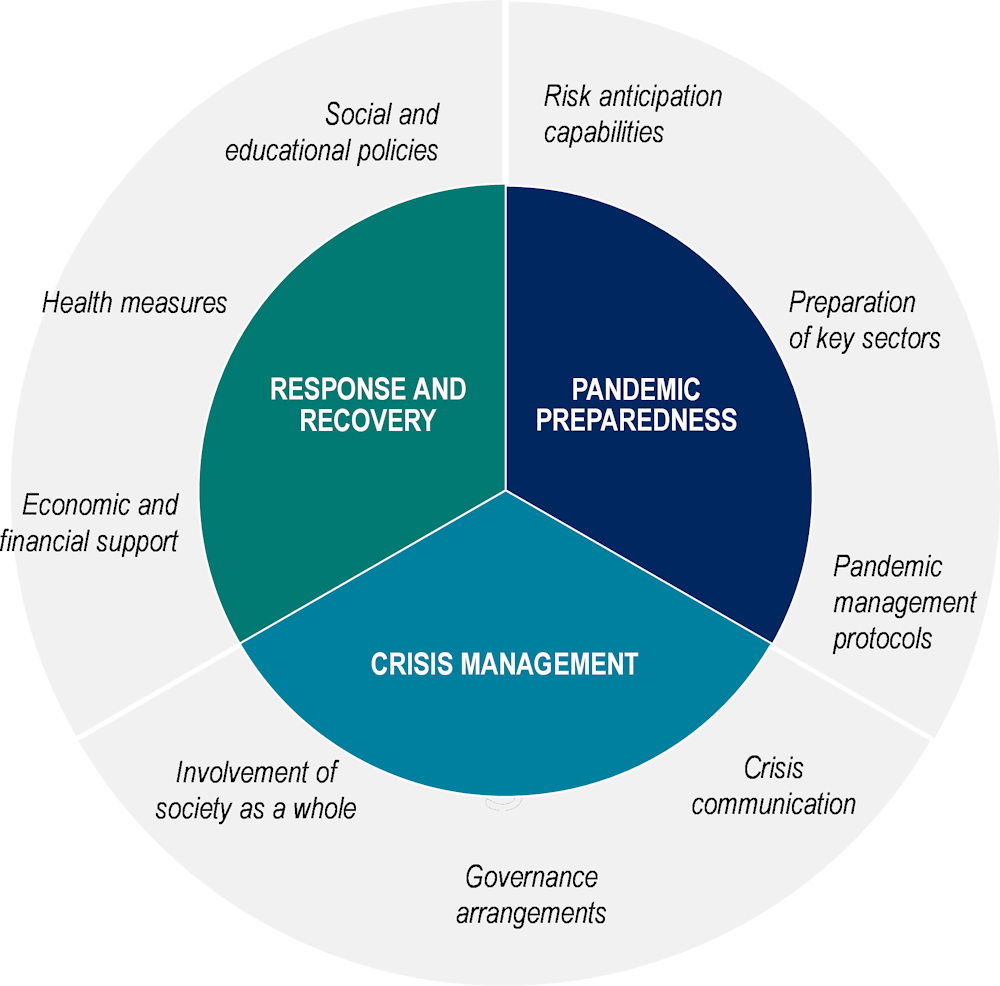

In 2020, government debt was low, and it was projected pre-crisis that it would continue to decline throughout the year, from an already low level of about 20% of GDP in 2019 (European Commission, 2020[10]). Luxembourg's gross debt was also among the three lowest in the OECD in 2017, with a gap of almost 80 percentage points from the OECD average (OECD, 2019[13]).

This pre-crisis situation allowed the government to provide huge levels of support to the economy with a limited impact on public balances

The health crisis sharply reduced economic activity levels, forcing all governments of OECD member countries to increase public spending. The challenge was to stabilise and then revive the economy while facing a general decline in tax revenues. In this context, Luxembourg was able to increase its public spending significantly to support the economy (Figure 1.3). The government was also able to take advantage of this room for manoeuvre to make huge investments in health (for example by doubling the number of intensive care beds or creating more advanced 2.0 medical centres) and in education (for example investing in online teaching).

Figure 1.3. Luxembourg's public debt level has remained contained despite a strong political response to the COVID-19 crisis

Even in this context, the increase in government debt and the government deficit was significantly lower than in most other OECD member countries (as a percentage of GDP); in 2020, Luxembourg was in the bottom half of OECD member countries with a deficit balance of -4.1% of GDP. This is mainly due to the resilience of tax revenues and economic growth that the country continued to experience during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as to exceptionally favourable financing conditions and relatively easy access to capital markets to finance the support measures being implemented (Benmelech and Tzur-Ilan, 2020[23]; Romer, 2021[24]). Chapter 6 of this report provides more information on this topic.

However, the long-term sustainability of public finances in the face of an ageing population remains uncertain

There are, however, some uncertainties about the long-term sustainability of Luxembourg's public finances (European Commission, 2020[10]). Between now and 2070, Luxembourg is expected to face one of the largest increases in age-related spending (pensions, long-term care and healthcare costs) among EU member states (European Commission, 2020[10]). Long-term projections for pensions and long-term care expenditure indicate risks to the sustainability of public finances (European Commission, 2020[10]). OECD projections also indicate that pension and healthcare spending will add significantly to budgetary pressure by 2060 (OECD, forthcoming[5]). The European Commission's projections show a similar trend, with total age-related expenditure expected to rise from 16.9% of GDP in 2019 to 27.3% of GDP in 2070, with most of this increase due to old-age pensions (European Commission, 2021[25]). As will be discussed in Chapter 4, this ageing population and the impact of age-related spending on public finances will undoubtedly be an issue in the future in a country where the long-term care sector is still suffering from some lack of investment. The sustainability of the measures adopted by the Luxembourg government during the crisis must therefore be assessed in the light of these challenges.

1.3.8. Luxembourg's economy is open and highly service-based

Luxembourg's economy is dynamic, open and highly dependent on the service sector

Prior to the pandemic, Luxembourg was experiencing economic growth that was moderate but above the average among EU countries (European Commission, 2020[10]); its annual real GDP growth (adjusted for inflation) averaged 3.2% between 2010 and 2018, compared to an EU average of 1.4%. This dynamism was also reflected in its standard of living, which was higher than the OECD average. On a per-capita basis, Luxembourg's GDP was USD 117 700 PPP in 2021, compared to an OECD average of USD 46 100 PPP per capita in 2020 (OECD, forthcoming[5]).

The structure of Luxembourg's economy has been a strength in the face of the shock caused by the crisis. However, the country has faced some challenges related to the significant slowdown in household consumption and its heavy dependence on foreign trade, which makes a significant contribution to its economic activity. Luxembourg has one of the highest levels of market integration among OECD member countries, with exports and imports more than double GDP (European Commission, 2020[10]).

In addition, the country's economy is mostly composed of services, which represent 87.5% of the economy, compared to 71.1% on average in OECD member countries (OECD, forthcoming[5]). Agriculture, forestry and fishing (0.2% compared to an OECD average of 2.7%), and industry (12.3% compared to an OECD average of 26.2%) account for a much smaller share (OECD, forthcoming[5]). On the other hand, the information and communication technologies services sector is growing faster than the Luxembourg economy as a whole, totalling 24% between 2010 and 2016.

Finally, Luxembourg's economy is distinguished by the role of the financial sector, which represented 25% of GDP and 11% of employment in 2020 (European Commission, 2020[10]), placing Luxembourg in first place in Europe and second place worldwide for the domiciliation of investment funds, for example (France Diplomatie, 2022[8]).

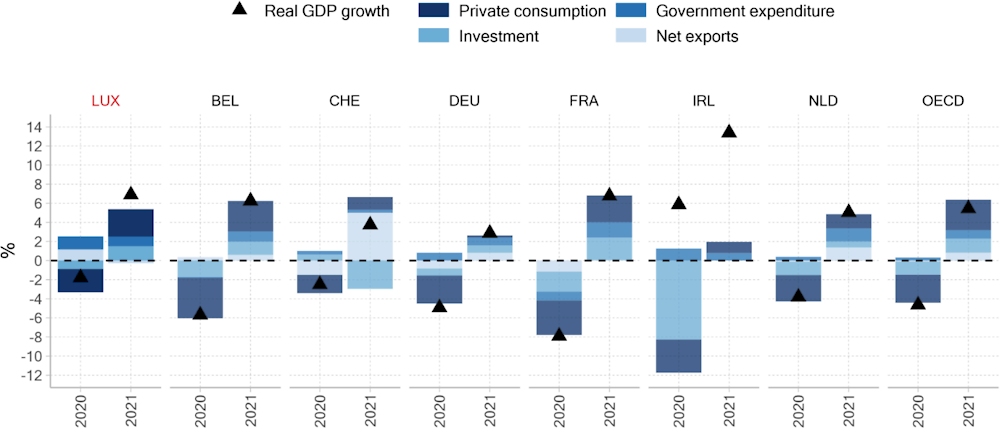

This has been a strength in the face of the shock caused by the pandemic

While high market integration also means greater exposure to external shocks, the Luxembourg economy has proved resilient overall to the COVID-19 pandemic: the downturn in 2020 was relatively mild, and its recovery has been robust, raising growth above pre-pandemic levels. GDP grew by 6.9% in 2021 after contracting by 1.8% in 2020. The slowdown in 2020 was mainly due to a drop in private consumption due to health restrictions, as was the case in all countries (see Figure 1.4). However, this decline was somewhat smaller in Luxembourg. This is due in particular to the decisive action taken by the government at the start of the crisis, with the introduction of COVID support measures equivalent to more than 4.2% of GDP (see also Chapter 6 on this subject).

Figure 1.4. The decline in GDP was mainly due to a fall in private consumption and investment

Note: The OECD value is the unweighted average of OECD member countries for which data are available.

Source: OECD, quarterly national accounts.

However, Luxembourg's better performance is also the result of the good dynamics of the services sectors, and in particular those related to financial services and information and communication technologies, which have remained relatively unaffected by the pandemic (General Directorate of the Treasury, 2021[26]). This sectoral specialisation has therefore allowed Luxembourg to continue its economic activity despite the health restrictions in place: the services sector, where most jobs can be done remotely, accounted for 55% of GDP in 2020. The acceleration of the digital transition in the services sector (development of working from home and remote services) has been one of the levers of growth in this sector in most European economies. Luxembourg's performance, however, went well beyond this, with activity growing by 11.4% (and value added growing by 0.66%) during the crisis. In the face of the crisis, this weight of the financial sector in Luxembourg's economy has also proved to be an asset, as it has enabled the country to successfully contain the decline in activity (France Diplomatie, 2022[8]). Finally, the information and communication services sector, which accounted for 8.3% of Luxembourg's GDP in 2020, with the notable inclusion of Amazon EU's headquarters, recorded a 17% increase in its value added in 2020, driven in particular by e-commerce.

1.3.9. The Luxembourg labour market is relatively dynamic but highly dependant on cross-border workers

The unemployment rate is low in Luxembourg but hides a contrasting reality

In 2019, before the crisis, Luxembourg had a strong job creation rate, which resulted in low unemployment (European Commission, 2019[22]). In 2020, the unemployment rate was 5.2%, compared to an OECD average of 7.1%. However, this figure hides inequalities in access to employment. The participation rate of those aged over 55 is among the lowest in the OECD (OECD, forthcoming[5]), at 45%. In 2020, the rate of unemployment among young people in Luxembourg increased (to 16.9%), exceeding the average for OECD member countries (12.8%), and many were at risk of being excluded from the labour market (OECD, forthcoming[5]). In addition, the long-term unemployment rate (one year or more) was 1.7% in Luxembourg in 2020, slightly above the OECD average of 1.3% (OECD, forthcoming[5]).

Heavy reliance on cross-border workers could have been a risk factor

Employment growth has always been supported by high levels of net immigration and cross-border workers, which, together with workers from other countries, make up an increasing share of Luxembourg's workforce (OECD, forthcoming[5]). In Luxembourg, cross-border workers, i.e. people who do not live in Luxembourg but travel there daily to work, represent 41% of salaried employment. Approximately 200 000 cross-border workers, 105 000 of whom reside in France, travel to Luxembourg every day from their country of origin (France Diplomatie, 2022[8]).

While immigration and a high level of cross-border workers are generally a demographic and economic benefit to the country (see previous sections on this topic), the border restrictions and closures that were put in place during the pandemic risked having a significant impact on the workforce and the country's economy. However, the Luxembourg government actively worked to prevent the closure of Luxembourg's borders throughout the pandemic to allow for the passage of cross-border workers (some of whom were considered key workers because they were employed in the health sector). Similarly, some employment support measures were specifically targeted at immigrant workers. Some of the following sections detail the measures taken by the Luxembourg government to keep the borders open and support cross-border work during the crisis.

1.3.10. In Luxembourg, the risk of poverty and social exclusion is relatively low, but growing

Inequality, poverty and social exclusion indicators in Luxembourg are close to or slightly better than the EU average, despite some signs of deterioration (European Commission, 2020[10]). In 2015, it was estimated that economically vulnerable individuals made up 30.8% of the population, compared to an average of 35.7% among OECD member countries (OECD, 2019[13]). Additionally, Luxembourg's relative poverty rate was 10.5% in 2019, compared to an average of 11.7% among OECD member countries in 2018 (OECD, forthcoming[5]). In Luxembourg, social benefits have a significant impact on poverty (European Commission, 2020[10]).

Nevertheless, income inequality has increased in recent years (European Commission, 2020[10]), although it remains below the OECD average: it had a Gini coefficient of 0.305 in 2019, compared to an OECD average of 0.317 (OECD, forthcoming[5]). Rising housing prices also increase the risk of inequality (France Diplomatie, 2022[8]).

Taking this context into account, household income support in Luxembourg has been provided through, among other things, Social Inclusion Income, an activation benefit consisting of an activity allowance, and the Rent Subsidy scheme (see Chapter 7 for more information on this subject).

1.4. How has Luxembourg responded to the crisis?

It is in this geographical, demographic, economic and social context that, since the start of 2020, Luxembourg has put in place policies to prepare for the arrival of the pandemic. At the beginning of January 2020, the government monitored developments in the COVID-19 situation before activating its crisis management mechanism. On 22 January, the High Commission for National Protection conducted an assessment of the situation in the People’s Republic of China and the following day, the Luxembourg Ministry of Health issued a press release outlining the measures to be taken if the novel coronavirus was detected in Luxembourg, alongside recommendations for people travelling to China.

In parallel, throughout January and February, the government initiated an interministerial preparedness phase to assess the needs and readiness of the various ministries, critical infrastructure and essential services for the health crisis. On 1 March 2020, when Luxembourg detected the first case of COVID-19 on its territory, the prime minister launched an initial crisis unit. Chapter 2 of this report assesses all of these pre-crisis measures, which were taken to anticipate the pandemic and prepare the country's response to it.

A state of emergency was declared in Luxembourg on 18 March 2020 (Government of Luxembourg, 2020[27]) (called ‘state of crisis’ in Luxembourg), by which point the government had already adopted, through the decrees of 13 March and 16 March 2020, measures to restrict movement and close down non-essential activities, similar to a “lockdown” (Government of Luxembourg, 2020[28]; Government of Luxembourg, 2020[29]). The main measures adopted in this sense were:

the closure of all schools and childcare facilities, as well as higher education (University of Luxembourg) and continuing professional development facilities as at 16 March 2020

the banning of visits to care homes for older people

a ban on hospital inpatient visits

the closure of cultural sites normally open to the public

a ban on travel except for activities considered essential (grocery shopping, commuting, visiting health facilities, etc.)

the suspension of cultural, social, celebratory, sports and recreational activities

the closure of hotel restaurants and bars, except for room service

the suspension of non-emergency activities in hospitals.

Essential activities, such as waste management, administrative services and hospital services, continued as normal. This was the beginning of the first phase of the pandemic. As in many OECD member countries, these travel restrictions and the rules for social distancing and mask-wearing would change over the following two years. Box 1.3 provides a general timeline of the crisis in Luxembourg.

Box 1.3. General timeline of the crisis in Luxembourg

Luxembourg detected the first case of COVID-19 in its territory on 1 March 2020.

First wave of the virus

On 18 March, Luxembourg declared a state of emergency with the Grand Ducal Regulation of 18 March 2020 introducing a series of measures in the context of combating COVID-19 (Government of Luxembourg, 2020[27]). The state of emergency was extended for a further three months by a law issued on 24 March 2020.

Luxembourg's first lockdown ended at the end of May 2020, when the virus transmission rate reached very low levels. Some businesses were allowed to reopen on 20 April, and masks remained mandatory in situations where a distance of 2 metres could not be guaranteed.

On 19 May 2020, a large-scale voluntary testing scheme was also launched. During the first phase of this large-scale testing scheme, which took place from 27 May to 28 July, up to 17 drive-through and two pedestrian- and bike-access test sites spread throughout Luxembourg could perform up to 20 000 tests per day.

Gradual easing of measures

As the state of emergency ended on 24 June 2020, measures to combat COVID-19 were then implemented through laws. Two laws of 24 June 2020, one introducing a series of measures concerning individuals within the framework of the COVID-19 pandemic response and the other introducing a series of measures concerning sports activities, cultural activities and establishments open to the public, replaced the grand ducal regulations.

Restrictions on gatherings, the wearing of masks in shops and on public transport, and the quarantine or isolation of people infected with coronavirus were initially extended until the end of July 2020.

Second and third wave of the virus

In October 2020, the second wave of COVID-19 hit most of Europe, and Luxembourgers experienced a series of new restrictions implemented to contain the virus. All bars, restaurants and cinemas closed on 26 November, as the country failed to reduce the number of new cases to under 500 per 100 000 people. Households were not allowed to have more than one guest at a time. A curfew imposed in November was extended until December 2021.

Luxembourg extended its restrictions until the middle of January 2021, and on 19 February it extended them again until 14 March 2021. They were then gradually lifted between the end of March and May 2021, once the vaccination campaign had been able to effectively begin protecting the most vulnerable people.

Source: In the text.

Once the state of emergency was adopted, Luxembourg's authorities implemented means to co-ordinate all parts of administration and society in their response to the crisis. To this end, the government changed how the crisis unit was structured and set up scientific and civil society advisory bodies. Frequent communication with the public through all channels (print media, television, radio, social media, etc.) was also conducted. Parliament also adapted its working methods to the crisis in order to reduce the time it took to review legislative texts. With a few changes, these mechanisms have been maintained throughout the crisis in Luxembourg and are still in place at the time of writing in mid-2022.

These co-ordination and communication efforts were also accompanied by important measures to mitigate the impacts of the COVID-19 crisis with regard to:

public health (e.g. through a proactive contact-tracing campaign, a highly personalised vaccination campaign, the establishment of a health reserve, etc.)

education (including deploying digital tools and keeping schools open during the second and third waves of the pandemic)

the economic and budgetary fields (in particular through the deployment of EUR 2.8 billion in financial assistance to businesses over two years)

the labour market and social policies (e.g. by supporting employment through short-time work or by introducing exceptional family leave).

These policies are discussed in the following chapters of this report.

Key findings of the report and areas of focus for the future

Two and a half years after the onset of the crisis, it is important to draw useful lessons from it in order to strengthen countries' future resilience. In this context, policy evaluations, such as the one conducted in this report, help countries understand what has worked and what has not, for whom and why. They also provide information to citizens and stakeholders on whether public spending achieved its intended objectives and results.

Evaluating governments' response to the pandemic involves looking at the full range of measures adopted in this regard throughout the risk management cycle: in crisis preparedness, in crisis management, and response and recovery policies. Within this framework, this report assesses Luxembourg's pandemic response in each of these phases and draws the following main conclusions:

Even before the crisis, Luxembourg had a mature risk management system. The country was also able to quickly and effectively co-ordinate the efforts of all those involved in crisis management, both at the local and interministerial levels and internationally – aided by smooth relations between the government and the communes, and agile crisis management governance.

While Luxembourg stands out for the very active involvement of its parliament throughout the crisis, which helped to ensure the continuity of the nation's democratic life, greater participation of civil society in all aspects of crisis management is desirable.

The direct health impact appears to have been lower in Luxembourg than the average for other OECD member countries. However, the pandemic has disproportionately affected elderly and disadvantaged populations and the indirect consequences of the pandemic are also of concern.

The mobilisation of resources and actors around the interministerial crisis unit was remarkable, and enabled new systems to be developed rapidly and health services to expand to absorb the shock of the health crisis. Luxembourg must now continue its efforts in developing new care delivery models, to put more emphasis on risk prevention and a multidisciplinary approach to care.

Luxembourg differs from other OECD member countries in terms of the low number of days that schools were closed, allowing for good educational continuity. However, the priority given to reopening schools has not always addressed all the challenges posed by the crisis, particularly in terms of inequality in student outcomes and negative effects on student well-being. The government must strengthen the measures it has in place to provide differentiated support to certain categories of students in order to contain the growth of educational inequalities.

Luxembourg's fiscal effort is in line with that of other comparable OECD member countries. This has enabled the public authorities to, overall, allocate enough assistance and support to preserve the financial situation of companies and maintain a relatively high level of employment. Despite this, initial direct subsidies given to businesses could have been larger, and support for self-employed workers has been insufficient.

Support was granted quickly and easily to companies, despite some initial hesitation. This agility allowed them to obtain assistance quickly – a decisive factor in safeguarding their liquidity. In the future, however, sectors particularly affected by the crisis, such as hotels, cafes and restaurants (HORECA), will require increased monitoring.

The labour market and social policies in Luxembourg were relatively well prepared for the COVID-19 pandemic. Existing mechanisms for job retention and to compensate for loss of income (sick leave, family leave, unemployment benefit, etc.) were extended and strengthened, and new measures have been adopted to meet emerging needs. Nevertheless, there is still room for policies to be refined to ensure that support reaches all those who need it and that no one is left behind should another such crisis occur in the future.

Finally, Luxembourg must strive to evaluate the impact of the measures adopted during the crisis more systematically in order to draw the relevant lessons.

References

[23] Benmelech, E. and N. Tzur-Ilan (2020), “The Determinants of Fiscal and Monetary Policies During the Covid-19 Crisis”, NBER Working Papers, Nr 27461, https://doi.org/10.3386/w27461.

[15] Congress of Local and Regional Authorities (2015), La démocratie locale au Luxembourg.

[25] European Commission (2021), Luxembourg 2021 Country Report.

[10] European Commission (2020), Luxembourg 2020 Country Report.

[22] European Commission (2019), Luxembourg 2019 Country Report.

[8] France Diplomatie (2022), Présentation du Luxembourg.

[26] General Directorate of the Treasury (2021), Commerce extérieur du Luxembourg, Mission économique du Luxembourg, https://www.tresor.economie.gouv.fr/Pays/LU/commerce-exterieur (accessed on 13 June 2022).

[28] Government of Luxembourg (2020), Arrêté ministériel du 13 mars 2020 portant sur diverses mesures relatives à la lutte contre la propagation du virus covid-19.

[29] Government of Luxembourg (2020), Arrêté ministériel du 16 mars 2020 portant sur diverses mesures relatives à la lutte contre la propagation du virus covid-19.

[27] Government of Luxembourg (2020), Règlement grand-ducal n165 du 18 mars 2020 portant introduction d’une série de mesures dans le cadre de la lutte contre le COVID-19.

[11] Government of Luxembourg (1868), “Constitution du Luxembourg”, Official Journal of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, https://legilux.public.lu/eli/etat/leg/recueil/constitution/20200519 (accessed on 13 June 2022).

[19] IGSS (2021), Rapport général sur la sécurité sociale au Grand-Duché de Luxembourg, Inspection générale de la sécurité sociale, https://igss.gouvernement.lu/fr/publications/rg/2020.html (accessed on 13 June 2022).

[16] Information and press services of the Luxembourg government (n.d.), À propos... des institutions politiques au Luxembourg.

[20] Lair-Hillion, M. (2019), État des lieux des professions médicales et des professions de santé au Luxembourg.

[12] OECD (2022), Digital Government Review of Luxembourg : Towards More Digital, Innovative and Inclusive Public Services, OECD Digital Government Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b623803d-en.

[1] OECD (2022), “First lessons from government evaluations of COVID-19 responses: A synthesis”, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/483507d6-en.

[4] OECD (2021), Applying Evaluation Criteria Thoughtfully, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/543e84ed-en.

[14] OECD (2021), Government at a Glance 2021, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1c258f55-en.

[21] OECD (2021), Health at a Glance 2021: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/ae3016b9-en.

[17] OECD (2020), “Building resilience to the Covid-19 pandemic: the role of centres of government”, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/883d2961-en.

[13] OECD (2019), Government at a Glance 2019, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/8ccf5c38-en.

[2] OECD (2015), The Changing Face of Strategic Crisis Management, OECD Reviews of Risk Management Policies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264249127-en.

[3] OECD (2014), “Recommendation of the Council on the Governance of Critical Risks”, OECD Legal Instruments, OECD/LEGAL/0405, OECD, Paris, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0405.

[5] OECD (forthcoming), OECD Economic Surveys: Luxembourg 2022, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[18] OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (2022), Luxembourg: Country Health Profile 2021, State of Health in the EU, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/3c147ce7-en.

[24] Romer, C. (2021), “The Fiscal Policy Response to the Pandemic”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, pp. 89–110, https://www.jstor.org/stable/27093821.

[6] STATEC (2021), Le Luxembourg en chiffres 2021, Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques.

[7] STATEC (2017), Cahier économique 123. Rapport Travail et Cohésion Sociale, Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques.

[9] University of Luxembourg (2021), Rapport national sur l’éducation : Luxembourg 2021.

Note

← 1. In the “traditional” education system, pre-primary education is provided in Luxembourgish, primary education is provided in German (including children's literacy), and most secondary education is in French or German.