Managing modern and complex crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, requires governments to mobilise a number of actors beyond the traditional emergency services, and to create a climate of trust in public action, which is essential to ensure its effectiveness. This chapter assesses the extent to which the mechanisms put in place in Luxembourg have enabled the government to adopt a co-ordinated and agile approach to responding to the pandemic across its different agencies. It then examines the effectiveness of the government’s crisis communications towards citizens, in terms of both the relevance and the coherence of its messaging. Finally, the chapter looks at the measures adopted by the Luxembourg government to deploy a co-ordinated response across society as a whole.

Evaluation of Luxembourg's COVID-19 Response

3. The management of the COVID-19 crisis in Luxembourg

Abstract

Key findings

Data from the OECD show that managing modern and complex crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, should involve a number of actors beyond traditional emergency services. It follows that government co-ordination is essential to steer and manage these different stakeholders. Crisis management also implies communicating with the public and ensuring decisions are transparent, especially since large-scale crises can have a huge impact on the public's trust in the authorities (OECD, 2015[1]; OECD, 2022[2]).

These issues, although heightened during the COVID-19 crisis, are not new. As early as 2014, the OECD Recommendation of the Council on the Governance of Critical Risks (see Box 3.1), adopted in 2014, recognises these challenges and offers recommendations to help governments to overcome them.

In Luxembourg, the interministerial management of the crisis, led by the highest level of government, was particularly agile. The national government spoke and responded with a single voice throughout the two-year health crisis. Although no information system existed for this purpose before the crisis, Luxembourg also very quickly put in place a reliable system for real-time monitoring of certain indicators that were key to managing the pandemic. However, the organisation of crisis management and the role of scientific expertise in policy-making must be more transparent in the future. This will require, among other things, the establishment of a permanent cross-disciplinary system of scientific advice, and more active involvement of civil society in crisis management.

Crisis communication has also been very effective overall in Luxembourg. Thanks to the existence of a clear crisis communication strategy prior to the pandemic, the crisis communication services were able to use a large number of channels to reach a wide audience and to be attentive to citizens' expectations. The government has also made significant efforts to make messages available in the country's official languages, as well as in some other languages frequently spoken by cross-border or immigrant communities. However, like many other OECD member countries, Luxembourg has experienced some difficulties in terms of coherence of messages. These difficulties are mainly related to the large number of sectoral and geographical measures adopted during the successive waves of the pandemic. They could be addressed by making a concerted effort to make the scientific reasoning for decisions explicit and by systematically evaluating the impact of communication measures.

Finally, with regard to the involvement of society as a whole in crisis management, vertical co-ordination between the national government and the municipalities and cities in Luxembourg worked better than in many other OECD member countries, even if the size of the country and the strong centralisation of its institutional system was a large contributing factor to this. Luxembourg also stands out for the active involvement of its parliament during the crisis, with the exception of a short state of emergency between mid-March and the end of June 2020. This involvement has ensured the continuity of the nation's democratic life. In addition, other forms of citizen consultation can be mobilised to build trust in public authorities in a representative democracy. In any case, Luxembourg should now focus on learning from this pandemic, in particular by investing in its public policy evaluation capabilities, to increase its resilience to future crises.

3.1. Introduction

This chapter focuses on the crisis management phase, which covers the policies and actions implemented by the government in response to the pandemic, i.e. once it had become a reality. “Crisis management” thus refers to the capacity of the government to react appropriately and at the right time, while ensuring co-ordination between all parts of the administration and of society (OECD, 2015[1]).

The management of modern and complex crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, should involve a number of actors beyond emergency services. As a result, increased co-ordination of these actors by the government is essential for managing the crisis and its many repercussions throughout society as closely as possible. This type of crisis also requires the government to maintain public trust, both to ensure the effectiveness of the measures adopted to mitigate the effects of the crisis and to maintain room for action in the future. Finally, the impact that large-scale crises can have on the public's trust in government requires that public authorities redouble their efforts to ensure the continuity of democratic life and to demonstrate the integrity, legitimacy and robustness of their decisions (OECD, 2015[1]; OECD, 2022[2]).

These issues, while undeniably heightened during the COVID-19 crisis, are not new. As early as 2014, the OECD Recommendation (see Box 3.1) required governments to make appropriate arrangements to manage risks and crises while maintaining strong interministerial co-ordination, to ensure transparent and meaningful crisis communication, and to enable a society-wide response to hazards and threats.

Box 3.1. The OECD Recommendation on the Governance of Critical Risks

The OECD Council adopted the Recommendation on the Governance of Critical Risks (hereinafter the “Recommendation”) at the Meeting at Ministerial Level held in May 2014. The High Level Risk Forum (HLRF) was instrumental in the development of this Recommendation. Since its adoption, 41 countries have signed up to the Recommendation.

The Recommendation focuses on critical risks, i.e. “threats and hazards that pose the most strategically significant risk, as a result of (i) their probability or likelihood and of (ii) the national significance of their disruptive consequences, including sudden onset events (e.g. earthquakes, industrial accidents or terrorist attacks), gradual onset events (e.g. pandemics) or steady-state risks (those related to illicit trade or organised crime).” The Recommendation is based on the principles of good risk governance that have enabled many member countries to achieve better risk management outcomes.

The Recommendation proposes that governments:

identify and assess all risks of national significance and use this analysis to inform decision making on risk management priorities (see Chapter 2 of this report)

put in place governance mechanisms to co-ordinate on risk and manage crises across government

ensure transparency around and the communication of information on risks to the public before a risk occurs and during the crisis response

work with the private sector and civil society, and across borders through international co-operation, to better assess, mitigate, prepare for, respond to and recover from critical risks.

Source: OECD (2014[3]), "Recommendation of the Council on the Governance of Critical Risks", OECD Legal Instruments, OECD/LEGAL/0405, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0405.

In line with this Recommendation, this chapter examines the extent to which the governance arrangements put in place in Luxembourg to manage the crisis enabled the government to adopt a co-ordinated and agile approach to responding to the pandemic across its different agencies. It also offers a look at the mobilisation and use of scientific expertise for crisis management in Luxembourg, and suggests strengthening the government advisory system for this purpose. The chapter then examines the strategies used by public authorities to issue crisis communications to citizens, in terms of both the relevance and the coherence of the messaging. Finally, the chapter looks at the measures adopted by the government of Luxembourg to deploy a co-ordinated response across society as a whole. The ways in which risks are identified and anticipated in Luxembourg are discussed in Chapter 2 of this report.

3.2. The interministerial management of the COVID-19 crisis in Luxembourg

According to the terminology adopted by the OECD, the crisis phase officially begins when a significant threat is clearly announced and anticipated, or when an undetected event causes a sudden crisis (OECD, 2015[1]). In Luxembourg, a state of emergency (also known as ‘state of crisis’, as defined in Article 32(4) of the Constitution) was officially declared on 18 March 2020 (see Box 3.2) (Government of Luxembourg, 2020[4]). Preparatory work and discussions, as well as interministerial meetings, partly in the form of a crisis unit, began on 24 January 2020 (see Chapter 2 on this subject).

Box 3.2. General timeline of the crisis in Luxembourg

Luxembourg detected the first case of COVID-19 in its territory on 1 March 2020.

First wave of the virus

The first measures to combat the effects of the pandemic were adopted on 13 March 2020 with the announcement that all schools and childcare facilities would be closed from 16 March.

On 15 March 2020, a special government meeting called on all residents to stay home as much as possible.

On 18 March, Luxembourg declared a state of emergency with the Grand Ducal Regulation of 18 March 2020 introducing a series of measures in the context of combating COVID-19 (Government of Luxembourg, 2020[4]). The state of emergency was extended for a further three months by a law issued on 24 March 2020.

Luxembourg's first lockdown ended at the end of May 2020, when the virus transmission rate reached very low levels. Some businesses were allowed to reopen on 20 April, and masks remained mandatory in situations where a distance of 2 metres could not be guaranteed.

On 19 May 2020, a large-scale voluntary testing scheme was also launched. During the first phase of this large-scale testing scheme, which took place from 27 May to 28 July, up to 17 drive-through and two pedestrian- and bike-access test sites spread throughout Luxembourg could perform up to 20 000 tests per day.

Gradual easing of measures

As the state of emergency ended on 24 June 2020, measures to combat COVID-19 were then implemented through laws. Two laws of 24 June 2020, one introducing a series of measures concerning individuals and the other introducing a series of measures concerning sports activities, cultural activities and establishments open to the public within the framework of the COVID-19 pandemic response, replaced the grand ducal regulations.

Restrictions on gatherings, the wearing of masks in shops and on public transport, and the quarantine or isolation of people infected with coronavirus were initially extended until the end of July.

Second and third wave of the virus

In October 2020, the second wave of COVID-19 hit most of Europe, and Luxembourgers experienced a series of new restrictions implemented to contain the virus. All bars, restaurants and cinemas closed on 26 November, as the country failed to reduce the number of new cases to under 500 per 100 000 people. Households were not allowed to have more than one guest at a time. A curfew imposed in November was extended until December 2020.

Luxembourg extended its restrictions until the middle of January 2021, and on 19 February it extended them again until 14 March 2021. The restrictions were then gradually lifted between the end of March and May 2021 with vaccines administered progressively to vulnerable populations.

Source: In the text.

In the face of such a situation, the OECD Recommendation stresses the importance of governance mechanisms and advises that members:

"Assign leadership at the national level to drive policy implementation, connect policy agendas and align competing priorities across ministries and between central and local government through the establishment of multidisciplinary, interagency-approaches (e.g. national coordination platforms) that foster the integration of public safety across ministries and levels of government" (OECD, 2018, p. 125[5]).

As such, the governance mechanisms proposed by the Recommendation take several forms, such as:

establishing specific structures to ensure interministerial co-operation

monitoring risk factors and implementing the crisis response

activating or creating mechanisms to gather expert advice on the pandemic.

This section of the chapter looks at how the government of Luxembourg used these three types of mechanisms and the extent to which they were able to cope with the complex and changing nature of the crisis.

3.2.1. Crisis leadership was provided at the highest level of government

As the OECD Recommendation states, strong leadership at the national level is essential for effective governance of the crisis. Such leadership is essential to facilitate co-operation and decision making across government and with external stakeholders, but it also plays a key role in crisis communication by helping to build trust in those managing the crisis (see the following section on crisis communication).

The Recommendation therefore calls, among other things, for the designation of a national institution to lead critical risk governance with co-ordination and incentive powers for the entire disaster risk management cycle (OECD, 2014[3]). The results of the OECD survey on critical risk governance show that most OECD member countries designate such a lead institution from within their central government, although the roles assigned to them vary considerably from country to country (OECD, 2018[5]).

In Luxembourg, the High Commission for National Protection and the ministry in charge of the primary sector affected by the crisis are responsible for this task. The High Commission for National Protection was created, in its current form, by the law of 23 July 2016 to ensure the management of national crises that require an urgent response and interministerial co-operation (see Box 3.3). In this context, the High Commission for National Protection is responsible for co-ordinating the contributions of ministries, agencies and services to crisis management, and for ensuring that all decisions taken in this regard are implemented and monitored.

Box 3.3. The High Commission for National Protection

The High Commission for National Protection was created, in its current form, by the law of 23 July 2016, based on the observation that the increasing occurrence of complex crises required a comprehensive approach to risk that included all sectors of society. At the national level, the High Commission for National Protection's missions are:

co-ordinating counter-terrorism measures

preventing, preparing for and managing crises

protecting critical infrastructures (see Chapter 2 for more information on the concept of critical infrastructure)

ensuring the functioning of the Government's Computer Emergency Response Team (GovCERT) and the National Agency for the Security of Information Systems (ANSSI).

In particular, with regard to crisis prevention, preparedness and management, the High Commission for National Protection's mission is to co-ordinate:

prevention measures, by

co-ordinating the contributions of ministries, agencies and government services

co-ordinating research programmes, policies and projects

conducting risk analysis and monitoring

co-ordinating the organisation of training courses and exercises.

anticipatory measures, by

developing and co-ordinating a national crisis management strategy

defining the type, structure, body and format of plans for crisis prevention and management measures and activities, and co-ordinating planning

initiating, co-ordinating and ensuring the execution of activities and measures related to the identification, designation and protection of critical infrastructure, whether public or private.

crisis management measures, by

initiating, conducting and co-ordinating crisis management tasks

ensuring the execution of all decisions taken

promoting a return to normality as quickly as possible

preparing a joint crisis management budget and ensuring its implementation

ensuring the establishment and operation of the National Crisis Centre.

Source: Government of Luxembourg (2016[6]), Loi du 23 juillet 2016 portant création d'un Haut-Commissariat à la Protection nationale [Law of 23 July 2016 establishing a High Commission for National Protection], https://legilux.public.lu/eli/etat/leg/loi/2016/07/23/n1/jo (accessed on 14 October 2022).

Within the framework of its responsibilities, the High Commission for National Protection is Luxembourg's point of contact for European and international institutions and organisations, and ensures effective co-operation with these entities. The creation of such an institution is in itself a step forward for risk governance, in that it allows for a comprehensive "all risks, all sectors" approach to crises – an approach that was all the more necessary in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Moreover, the High Commission for National Protection is hierarchically attached to the centre of government (CoG) (the Ministry of State) (see Box 3.4 for more information on the concept of centre of government). This choice, made by only a minority of OECD member countries (13 out of 34 respondents) according to the critical risk governance survey (OECD, 2018[5]), allowed Luxembourg to draw clear lines of responsibility very early on in the management of the crisis. The political leadership of the CoG is essential to maintain citizens' confidence in the government in the context of infringements (albeit temporary and proportionate) on fundamental freedoms for the purpose of limiting the effects of the pandemic.

Box 3.4. The OECD definition of a centre of government

The CoG is "the body or group of bodies that provide direct support and advice to heads of government and the council of ministers, or cabinet" (OECD, 2018[7]). A key institution in the executive branch, its mandate is to ensure that elected officials make decisions informed by evidence and expert analysis, and to facilitate co-ordination between government institutions.

The concept of the CoG does not refer to any specific organisational structure: its composition may vary according to the political system at play or contextual factors. The functional definition of the CoG may include institutions or agencies that perform essential cross-cutting government functions, such as planning, co-ordination, prioritisation and policy development, even though they may not report directly to the head of government. While the role of the CoG is traditionally more procedural (e.g. preparing the Council of Ministers agenda), in OECD member countries, it is generally moving towards strategic leadership and interministerial co-ordination.

Source: OECD (2020[8]), "Building resilience to the Covid-19 pandemic: the role of centres of government", OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/883d2961-en.

As such, where other OECD member countries had to appoint a single co-ordinator or point of contact within the CoG (e.g. Italy, Latvia and New Zealand) to more clearly articulate the national response to COVID-19 (OECD, 2020[8]), Luxembourg could rely on the existing leadership of the High Commission for National Protection. In addition, co-ordinators were appointed within the ministry responsible for the sector mainly affected by the crisis: the Minister for Health and the Health Director. Together, the High Commission for National Protection, the Minister for Health and the Health Director provided leadership in the response to the crisis. This dual approach allowed Luxembourg to benefit from specific health expertise that was particularly necessary for this crisis, and also enabled the CoG to focus on the interministerial dimension of crisis management while maintaining a view to the medium and long term.

3.2.2. The governance of the crisis unit allowed for great agility in the government's response

In addition to clear leadership, crisis management requires appropriate governance arrangements to co-ordinate the response efforts of the various government stakeholders. To this end, the OECD Recommendation on the Governance of Critical Risks calls for the creation of a crisis unit to co-ordinate disaster response efforts (OECD, 2014[3]). Such a crisis unit was also set out in Luxembourg's general risk governance framework. However, like many OECD member countries, Luxembourg had to alter the composition and structure of the crisis unit to respond effectively to the pandemic, which was complex and ever-changing and affected a wide range of areas.

Indeed, very few OECD member countries have experienced a pandemic in recent decades, with the exception of the SARS virus, which affected countries such as Canada, Korea and Singapore. While these countries may have been better prepared for the COVID-19 pandemic, many, like Luxembourg, found that their risk management governance plan was not necessarily suitable for this type of complex crisis (see Chapter 2 for more information on Luxembourg's overall crisis preparedness level). Cross-border and highly complex crises like the COVID‑19 pandemic require the active involvement of many public services and bodies at different administrative levels, as well as a high degree of agility in decision making in the face of many "unknowns" (OECD, 2015[1]). To better understand the distinction between complex and traditional crises, and what this means in terms of adapting crisis management, see Table 3.1.

Table 3.1. Managing new and complex crises

|

Traditional crises |

New and complex crises |

|---|---|

|

Centralised monitoring and control system |

Crisis identification/monitoring: scientific expertise plays an important role |

|

Standard procedures |

Flexible and versatile crisis management teams |

|

Strict lines of responsibility |

Leadership with strong capacity for adaptability |

|

Sectoral approaches |

International and multisectoral co-operation |

|

Principle of subsidiarity |

Management of response networks |

|

Feedback to improve procedures |

Ending the crisis and restoring confidence, and conducting evaluations to improve procedures |

Source: Prepared by the author based on (OECD, 2015[1]), The Changing Face of Strategic Crisis Management, OECD Reviews of Risk Management Policies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264249127-en.

In Luxembourg, the limits of the crisis unit – which was intended to serve as a platform for interministerial work within the framework of the influenza pandemic (Government of Luxembourg, 2006[9]) and Ebola (Government of Luxembourg, 2014[10]) ERPs –crisis became apparent very quickly in the face of the COVID-19. As a result, even before a state of emergency was declared in the country on 18 March 2020 (Government of Luxembourg, 2020[4]), Luxembourg had already decided to adapt the structure of the crisis unit. The structure of this crisis unit was reviewed and adapted several times over the following two years, with working groups being added or removed with the different waves of the virus (see Box 3.5 on the general timeline of the pandemic) in order to better reflect the concerns of the public authorities in relation to the health crisis.

Box 3.5. Evolution of the composition of Luxembourg's crisis unit over time

Interministerial preparation phase (24 January 2020 to 28 February 2020)

At the request of the Prime Minister, the High Commission for National Protection and the Ministry of Health submitted a note on the characteristics of the virus and the country's level of preparedness to Luxembourg's Governmental Council for its meeting on 24 January 2020. A number of subsequent interministerial meetings enabled the public authorities to analyse the country's level of preparedness in light of the influenza pandemic and Ebola ERPs, to place the first orders for PPE and to organise the repatriation of Luxembourg citizens.

First meeting of the crisis unit as provided for in the influenza pandemic ERP (1-15 March 2020)

After the first case of COVID-19 on Luxembourg territory was confirmed, the Prime Minister declared that the crisis unit of the influenza pandemic ERP was to be put into action. In addition to the High Commission for National Protection, this crisis unit was composed of representatives from most government ministries, as well as the Grand Ducal Police, the Grand Ducal Fire and Rescue Corps and the Crisis Communication Service.

Changes to the composition of the crisis unit (15 March 2020 to mid-May 2020)

The composition of the crisis unit, as set out in the influenza pandemic ERP, quickly proved to be inadequate given the scale of the pandemic, the large number of sectors it affected and the speed at which it evolved. The Luxembourg government therefore decided to adapt the structure of the crisis unit by expanding its composition to include non-state stakeholders and by forming permanent thematic working groups to deal with more technical issues. During this period, the Governmental Council also met two to three times a week to ensure the co-ordination of work at the ministerial level and to adopt the grand ducal regulations necessary for the crisis unit's decisions to be implemented.

Interministerial working group on the crisis exit strategy (mid-April 2020 to mid-June 2020)

A specific working group was created to make proposals to the government on the different phases of the exit from the crisis (easing of lockdown and accompanying measures, such as sectoral recommendations, distribution of protective equipment, implementation of a large-scale testing strategy, etc.). This working group was composed of representatives from the Ministry of State, the High Commission for National Protection, the Ministry of Health, the Health Directorate, the Ministry of Higher Education and Research, and the COVID-19 Task Force. This group had regular meetings with representatives from government departments to discuss the gradual lifting of the restrictions put in place during the lockdown phase.

Crisis unit version 2 within the Ministry of Health (mid-May to mid-October 2020)

The composition of the crisis unit was adapted to the new calmer epidemiological situation, bringing together fewer actors and focusing more on the services of the Ministry and the Health Directorate.

Crisis unit version 3 (mid-October 2020 to present)1

With the resurgence in the number of positive cases, the government decided to revert the structure of the crisis unit to the way it was during the period from 15 March to mid-May, with thematic working groups.

1. Day this report was finalised (summer 2022).

Source: High Commission for National Protection.

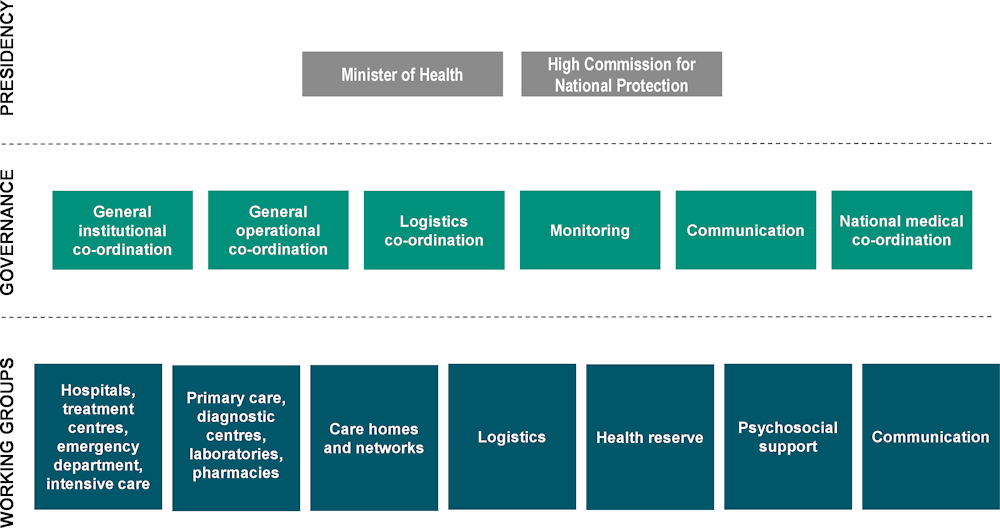

The crisis unit, chaired by the High Commission for National Protection and the Ministry of Health, is composed of several working groups, which oversee and work on separate areas, such as hospitals, diagnosis and contact tracing, testing, primary care, care homes and care networks, logistics, the health reserve and communication (see Figure 3.1 for an example of how these working groups are organised).

Figure 3.1. Composition of the crisis unit during the first wave of the pandemic

Source: Prepared by the author based on internal documents provided by the High Commission for National Protection.

It co-ordinates all the efforts made by both government stakeholders – in terms of procurement and logistics of medical supplies, and communication and monitoring of the pandemic – and non-governmental actors, such as hospitals, laboratories, primary care providers, pharmacies, etc. As such, these working groups were generally multidisciplinary and included representatives from several ministries and departments, as well as, in the case of some working groups such as the Testing working group, representatives from the private sector.

First of all, the government of Luxembourg showed flexibility and speed in implementing and putting into action these governance mechanisms to facilitate inter-agency co-operation in the management of the crisis. This flexibility and the mobilisation of actors from a wide range of backgrounds was particularly possible because communication between the state and non-governmental stakeholders in the country is fluid.

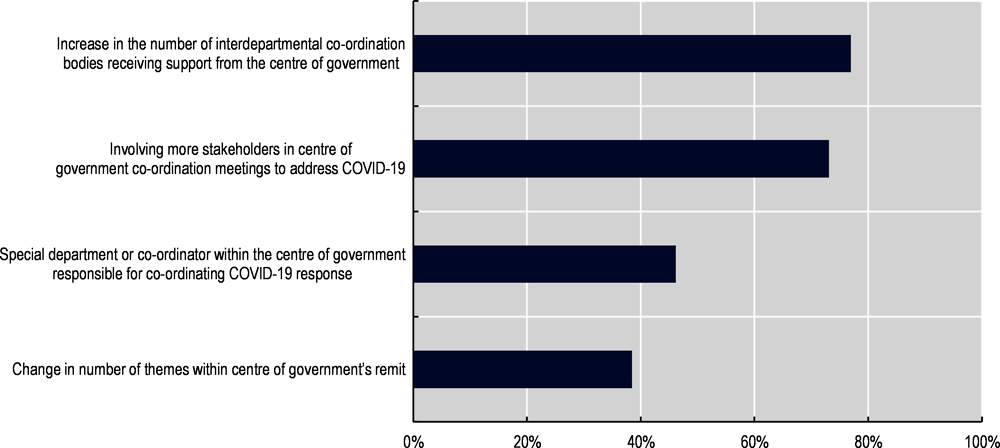

Moreover, while most OECD member countries also appear to have created ad hoc structures to manage the COVID-19 crisis (almost half of members created new institutional mechanisms to respond to the pandemic (OECD, 2021[11]), see Figure 3.2), Luxembourg stands out for the very high level of representation that its systems provide.

Figure 3.2. Evolution of the functions and structure of the centre of government during the crisis

Note: These data are from 26 OECD member countries: Austria, Belgium, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Mexico, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Korea, Sweden and Türkiye.

Source: OECD (2021[11]), Government at a Glance 2021, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1c258f55-en.

In fact, in principle, the various ministerial departments were represented in the working groups by the government's chief advisors. This allowed the decisions made in these working groups to be adopted quickly. However, the OECD's work shows that the presence of high-level figures gives more weight to the debates that take place in the crisis unit, increases accountability and speeds up decision making (OECD, 2022[2]).

In Luxembourg, the presence of the chiefs of staff or general co-ordinators of the various ministerial departments in these working groups made it possible to take decisions very quickly without them having to be systematically validated by a higher authority, and enabled technical subjects to be addressed with the relevant experts.

Luxembourg also significantly increased the frequency of Governmental Council meetings, which made it possible to adopt decisions that could not be made in working groups in this framework (for example, the grand ducal regulations implementing certain measures prepared by the working groups). The flexibility of the crisis unit's structure throughout the different waves of the pandemic, the multidisciplinary composition of the working groups and the high level of representation within them allowed Luxembourg to be reactive and innovative in managing the crisis. The stakeholders met by the OECD Secretariat emphasise the agility in crisis management enabled by these mechanisms.

In addition to the national mechanisms discussed in detail in this chapter, there was also a highly developed cross-border and European dimension to crisis management, based in particular on specific collaboration structures with neighbouring countries. The successful functioning of these mechanisms has been of particular importance for Luxembourg, which is one of the European countries most directly interconnected and interdependent with its neighbouring regions within a shared cross-border living area. Chapter 2 of this report addresses this dimension.

3.2.3. This structure may have reduced the clarity and transparency of decision making

The structure of the crisis unit in Luxembourg undeniably reflects the complexity of the shock caused by the pandemic. However, the creation of bodies to co-ordinate the government's response to the crisis, while useful for political decision making, risked producing challenges related to internal co-ordination between them, particularly with respect to gaps and overlaps in the respective responsibilities of the working groups. Coherence in policy making and the uniform application of these decisions is crucial to ensure the effectiveness of crisis management measures (OECD, 2020[8]). While this does not ultimately seem to have been a problem in Luxembourg, where exchanges between senior administration officials are usually fluid, it might be useful in the future to clarify the responsibilities and missions of each crisis management body in the form of terms of reference. Such terms of reference would avoid any doubt about the scope of competence of each of these bodies and, most importantly, clarify who has final responsibility over a decision. Furthermore, these terms of reference would ensure greater transparency in crisis management decision-making processes and are therefore an important instrument for accountability to citizens (OECD, 2022[2]).

Above all, it would have been desirable to include civil society more from the outset in the various working groups of the crisis unit during the COVID-19 pandemic. With a few exceptions (e.g. the participation of ASTI and Caritas in the social working group), no civil society stakeholders participated in the working groups. Even when this participation did occur (on an informal and ad hoc basis), there was a definite lack of formality in the consultation of civil society in these working groups. The role of civil society is increasing in the new crisis management environment. In the face of complex crises where there are many unknowns and which affect all sectors of society, citizens, voluntary organisations and national and international non-governmental organisations should be included in all response systems (OECD, 2015[1]). Greater involvement of civil society, or stakeholders from non-traditional sources of expertise, should be considered more seriously in the future in Luxembourg (see next section on the role of scientific expertise in the crisis).

Finally, the OECD Recommendation on the Governance of Critical Risks emphasises the importance of making information and the actions taken by risk management bodies to ensure the integrity of their decision-making processes available and accessible to the public. In times of crisis, while exceptional circumstances may require restricting access to sensitive or classified information, critical risk management decision-making procedures still benefit from being shared. Luxembourg has made this information widely available to the public. However, although the organisational chart of the crisis unit, the ad hoc working group and the interministerial group on the crisis exit strategy, as well as the associated list of experts, have been published on the government website, Luxembourg could consider further clarifying the lines of responsibility of the crisis unit vis-à-vis external stakeholders.

3.2.4. Although no information system existed for this purpose before the crisis, Luxembourg very quickly put in place a reliable system for real-time monitoring

In times of crisis, it is essential for governments to have access to real-time data to monitor risk factor developments and support hazard management decision making (OECD, 2022[12]). The COVID-19 crisis in particular has shown how evidence and information are crucial inputs for effective public action. However, collecting this data can be difficult for some countries as it requires the right digital tools and reporting procedures to enable analysis, decision making and implementation of those decisions (OECD, 2021[11]). Although Luxembourg did not have an adequate pandemic risk monitoring system in place prior to the crisis, it was able to remedy this situation quickly by developing new monitoring tools and protocols. This effort should be extended to other risks and key sectors to ensure robust risk monitoring.

Before the pandemic, Luxembourg had an imperfect information system capable of monitoring the evolution of infectious diseases. Although Luxembourg's public health protection law of 1 August 2018 (Official Journal of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, 2018[13]) obligated it to declare cases of around 70 communicable diseases, doctors had to report this information either in writing or by fax and, since 1 January 2019, by filling in an online form available at https://guichet.lu. Making declarations in this way did not allow for the analysis of fast-changing data. Medical testing laboratories had been issuing results electronically since 1 January 2019, but the system was not equipped to handle the high number of declarations produced in the pandemic. Moreover, this reporting obligation was limited to positive results for the majority of diseases. It was therefore not easy for the government to monitor the population's COVID-19 positivity rate and to obtain a complete, real-time overview of epidemiological developments in the country (Ministry of Health, 2021[14]).

In addition, the hospitalisation data available in information systems that existed before March 2020 were not sufficient to track the day-to-day evolution of the pandemic. For example, there was no health monitoring system in place for COVID-19 hospital admissions, intensive care bed occupancy rates, or COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 occupancy rates on regular wards, and the activity indicators for hospital emergency departments, provided for in the Grand Ducal Regulation of 25 January 2019, were not systematically collected (see Chapter 4 on public health policies in Luxembourg for more information on these systems). Another major challenge faced by the public authorities was the fact that the indicators collected in hospitals were not harmonised, making it impossible to compare them across different facilities. The government was also not aware of stock levels of PPE in non-hospital healthcare facilities. With regard to the long-term care sector, there were no harmonised indicators, either quantitative or qualitative, to document the activities and resources of the various facilities.

Based on this observation, very quickly after the first case of COVID-19 was detected in the country, the crisis unit's monitoring working group undertook a major effort to set up a system for daily and reliable monitoring of the spread of the virus, the pressure put on hospitals and other healthcare facilities by the virus, and other information essential for managing the crisis, such as stocks of PPE and the pandemic situation in neighbouring countries. To this end, the monitoring working group, in conjunction with the other crisis unit working groups (e.g. the hospital working group and the contact-tracing group) and healthcare system stakeholders:

Established data-sharing routines, including defining joint indicators to harmonise monitoring between the different actors and establishing a data quality control system.

Automated, as of 17 March 2020, data transfers from hospitals and testing laboratories using the new Qlik information system (see Box 3.6 for more information on this tool), and rapidly expanded data transfers from other sources (long-term care facilities, advanced care centres, etc.). The Qlik database also made it possible to visualise data in the form of tables and maps to help the crisis unit and the government make quick decisions.

Produced daily and weekly reports for the crisis unit and the Ministry of Health with updates on the epidemiological surveillance of COVID-19, COVID-related hospitalisations, the status of stocks of PPE and other materials needed to treat COVID cases, deaths due to COVID, and vaccines administered in Luxembourg.

Box 3.6. The Qlik database

The Qlik application brings together COVID-19 data from various actors (such as laboratories, hospitals, care homes, the General Inspectorate of Social Security, and advanced care centres) in thematic dashboards that allow users to follow the evolution of the pandemic and conduct relevant analyses.

It has been progressively improved by integrating other data (such as those from the mass screening programme and contact tracing, those relating to vaccination administration and coverage, those concerning advanced care centre activity, those concerning the status of wastewater, and individual data from the General Inspectorate of Social Security) to perform sectoral analyses and identify possible sources of outbreaks.

Automated daily reports were developed for several bodies (such as the Ministry of Education, the Ministry of Family Affairs and the Fédération des Hôpitaux Luxembourgeois [Luxembourg Hospitals Federation]). Aggregate data are also publicly available.

Source: OECD (2022[15]), information-gathering questionnaire for the Luxembourg Crisis Management Evaluation (see also Chapter 4 of this report).

The implementation of this monitoring system has served as a real aid to decision making for the crisis unit, and Luxembourg stands out for the speed with which it was able to set up these processes and this platform. This speed is partly due to the fact that the number of health actors involved in the response to the pandemic in Luxembourg is relatively small. As a result, the country was able to quickly establish rules for collecting indicators such as bed availability and PPE stocks with the hospital sector, because it only has four hospitals and a small number of specialist facilities. Other risks and hazards may, however, involve a larger number of actors. To increase the country's resilience to future crises, the High Commission for National Protection should strengthen its critical risk monitoring system and establish sustainable and standardised processes for collecting data from critical infrastructure and services.

Luxembourg should therefore consider increasing its monitoring of key intelligence indicators related to the main risks identified in Luxembourg, in concert with not only the infrastructure already identified as critical but also the country's essential services. Indeed, as discussed in Chapter 2, while critical infrastructure requires more advanced monitoring and preparation, other essential services cannot remain a blind spot in risk monitoring. For example, establishing clear and lasting rules and processes with actors from the long-term care system, adapted to the realities on the ground and allowing for monitoring of certain key data (PPE stocks, vacancies for essential qualified staff, the quantity and age of ventilators, and energy stocks in case of shortages, etc.), could prove an important tool to help manage other crises. In this context, Luxembourg could draw inspiration from the United Kingdom's National Situation Centre, which was created in September 2021 to monitor risks and model their effects as closely as possible to the CoG (see Box 3.7 for more information on this body).

Box 3.7. The United Kingdom's National Situation Centre

The United Kingdom's National Situation Centre, known as SitCen, is located in the Cabinet Office Civil Contingencies Secretariat at the centre of government. The COVID-19 crisis highlighted the importance of high-quality data in making better decisions. As a result, SitCen was created during the COVID-19 pandemic in September 2021 to collect and collate timely and reliable data on all aspects of risk and crisis management.

SitCen has three roles:

to provide public decision makers with an overview of public institutions and critical sectors using dashboards

to model past data to generate projections related to the materialisation of certain risks

to brief senior officials and ministers on the basis of these data.

The SitCen team works primarily on the set of risks identified in the national risk assessment, with the aim of preparing for the future and determining what policies to adopt in the event that one of these risks materialises.

Source: Prepared by the author.

Luxembourg could also consider revising its definition of critical infrastructure to include other essential stakeholders and services. This was done in Scotland, where social services are now considered essential services alongside the National Health Service (NHS).

With regard to pandemic preparedness specifically, establishing coherent data flows and corresponding databases that integrate all the relevant data collected by the different stakeholders (hospitals, contact-tracing systems, the Ministry of Health, etc.) is essential to enable quick and high-quality analysis for future pandemics (see Chapter 4 for more information on this topic). Furthermore, while the implementation of the Qlik information system has been critical to Luxembourg's response, the country must continue its efforts to develop a single information system, where databases are interoperable, with a unique identifier for patients and where health services are automatically integrated. Despite improvements linked to the pandemic and to the implementation of shared medical records, Luxembourg's information systems are still incompatible. As some OECD member countries have shown, an integrated health information system allows for better management of health crises. Canada, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Korea, Latvia, the Netherlands and Sweden all stand out for their integrated information systems that linked data from multiple health sectors and provided real-time data from the onset of the pandemic crisis (Oderkirk, 2021[16]) (see also Chapter 4). The challenge is to design systems that can be used not only to transmit information, but also for internal management purposes (this is particularly important given the time constraints typical of crisis periods) (OECD, 2022[2]).

3.2.5. The role of scientific expertise in public decision making should be strengthened more generally outside of crisis periods to increase its legitimacy

The last important aspect related to crisis management governance concerns the advisory role that experts and scientific bodies played in Luxembourg to help the public authorities make decisions. This role is also known in risk management as "sense-making".

As discussed in the previous section, the COVID-19 crisis required governments to make clear and legitimate decisions based on reliable data in a context where there were many unknowns and very little time for dialogue and information gathering (OECD, 2020[8]). Governments were also faced with the need to synthesise information from multiple sources and stakeholders and use it to inform plans and responses to the COVID-19 crisis (OECD, 2020[8]). To address this, the vast majority of OECD member countries called on scientific expertise to inform public decision making. While necessary in the face of so many unknowns, this risked threatening the public's trust in government and in expert advice, and calling into question the boundary between expertise and political decision making.

In Luxembourg, trust in government is stronger than average in OECD member countries (OECD, 2022[17]), but maintaining a high level of trust in the event of repeated crises and ensuring that the best expertise is available quickly may require setting up a permanent scientific advisory system with transparent governance to ensure that decisions are made with the best possible basis.

The creation of the COVID-19 Task Force gave Luxembourg a unified voice with specialist expertise

Many OECD member countries, such as Belgium, Colombia, Spain and Switzerland, created an ad hoc scientific committee in March 2020 to advise the government. In Luxembourg, this committee was named the COVID-19 Task Force. The Task Force was formed to provide the health system with the combined expertise available in Luxembourg's public research sector, under the co-ordination of the Ministry of Higher Education and Research. The missions of this Task Force were:

To co-ordinate scientific expertise from public research (Luxembourg Institute of Health, Luxembourg Institute of Socio-Economic Research, Luxembourg Institute of Science and Technology, National Health Laboratory, Luxinnovation, University of Luxembourg, and the Luxembourg National Research Fund) to support decision making by healthcare providers and the government.

To help identify and centralise a variety of priority activities, drawing on intersectoral expertise in biology, medicine, mathematics, informatics, epidemiology, economics, and social sciences.

To be the point of contact between the national research ecosystem, the clinical community and the authorities in order to promote joint projects (OECD, 2022[15]).

The creation of this Task Force in Luxembourg allowed for scientific advice to be centralised in the face of such uncertainty and rapidly evolving evidence.1 In France, however, the mission to control the quality of the management of the health crisis found that the dispersion of scientific expertise among several public health authorities may have made it difficult to pool knowledge and competences (Report of the Mission on quality control of the management of the health crisis, 2020[18]). In general, OECD data suggest that the creation of a new scientific advisory body improved government decision making on complex issues related to COVID-19 (OECD, 2022[2]).

However, even the most respected researchers and scientists, with their expertise, cannot ensure that the best evidence-based policies are adopted and implemented without the support of an effective national scientific advisory system. In Luxembourg, two scientific committees with competence in health matters existed prior to the pandemic: the Conseil Scientifique du Domaine de la Santé [Scientific Health Board], whose mission is to issue recommendations on medical and care best practices, and the Superior Council of Infectious Diseases, whose mission is to issue recommendations on infection prevention and control. The Superior Council of Infectious Diseases has been particularly active in developing the vaccine strategy and vaccine recommendations. However, there was no formalised system for gathering cross-sectoral scientific expertise (the Ministry of Higher Education and Research is normally responsible for co-ordinating scientific advice).

Trust in expert advice must be built over time. In addition, OECD data show that the new scientific bodies created to meet the needs of the crisis may have had difficulty accessing the data and information necessary for their analysis (OECD, 2022[2]). While this was not the case in Luxembourg, the government could consider establishing a permanent institutional structure to collect scientific advice at the highest level of government, along the lines of what has been done in the United Kingdom (see Box 3.8).

Box 3.8. The United Kingdom's Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies

The United Kingdom created the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE), which advises the Cabinet when a crisis requires expert guidance. SAGE meets in situations that require intergovernmental co-ordination, including when the Cabinet, in consultation with the Prime Minister, decides to put the Cabinet Office Briefing Rooms (COBR) into action. In this context, SAGE meets to provide scientific and technical advice on how a risk might develop and on potential scenarios and their impacts. The advisory group is both flexible and scalable in that its tasks are adapted to the nature of the risk and evolve as the crisis progresses.

Under the authority of the government's Chief Scientific Adviser, SAGE brings together experts from all sectors and disciplines to analyse data, evaluate existing research and commission new research. It may create subgroups or liaise with decentralised institutions or scientific groups, and it is empowered to access intelligence information.

To inform the government, SAGE presents strategic options documents that describe scientific and technical solutions and their advantages and disadvantages in relation to different response scenarios. At all stages, SAGE representatives attend COBR to explain scientific issues.

Source: OECD (2015[1]), The Changing Face of Strategic Crisis Management, OECD Reviews of Risk Management Policies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264249127-en.

To this end, Luxembourg would benefit from following the principles of a robust and credible scientific advisory system established by the OECD (see Box 3.9).

Box 3.9. General principles for a robust and credible system to provide science advice to the government

To ensure the availability of credible expertise, governments should create scientific advisory systems that:

1. Have a clear mandate, with defined roles and responsibilities for its various actors. This includes:

clear definition and demarcation of advisory and decision-making roles and functions

definition of the roles and responsibilities of each actor in the system

ex ante definition of the legal role and potential liability of all persons and institutions involved

availability of the institutional, logistics and personnel support necessary to accomplish the advisory mission.

2. Involve relevant stakeholders, including scientists and policy makers, as appropriate. This involves:

using a transparent participation process and following strict procedures for declaring, verifying and dealing with conflicts of interest

drawing on the scientific expertise needed in all disciplines to address the issue at hand

explicitly considering whether and how to engage non-scientific experts and civil society stakeholders in advice development

implementing effective procedures for timely information exchange and co-ordination with various national and international counterparts.

3. Produce sound, unbiased and legitimate advice. This advice should:

be based on the best scientific data available

explicitly assess and communicate scientific uncertainties

be free from political interference (and other special interest groups)

be generated and used in a transparent and responsible manner.

Source: OECD (2022[12]), Scientific advice in crisis: Lessons learned from COVID-19; OECD (2015[1]), The Changing Face of Strategic Crisis Management, OECD Reviews of Risk Management Policies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264249127-en.

Some challenges may have arisen in relation to governance of this scientific expertise

The OECD has identified several principles for establishing an effective national science advisory system (OECD, 2015[1]). These principles underline the importance of the governance of scientific expertise for ensuring the relevance and credibility of the resulting advice. Indeed, maintaining trust between decision makers and scientific evidence providers is essential for effective decision making when there is great uncertainty.

Firstly, including expertise from a variety of backgrounds ensures that decisions are informed by credible and neutral advice. In Luxembourg, the COVID-19 Task Force brought together multidisciplinary expertise in public health, economics, innovation, public-private partnerships and logistics. In contrast, many OECD member countries' scientific advisory committees are composed solely of epidemiologists, virologists, public health experts and medical experts (OECD, 2020[8]). Nevertheless, Luxembourg could extend the multidisciplinary dimension of its Task Force even further by including experts in ethics and rights in particular. This is what the Swiss government has done, for example, by creating the National COVID-19 Science Task Force (Swiss Federal Chancellery, 2020[19]).

There is also a role for civil society and practitioners in managing the link with scientific expertise. Civil society organisations could have been consulted in the process of developing scientific advice in Luxembourg. OECD data show that few countries have involved stakeholders on the ground and civil society organisations in their scientific advisory committees (OECD, 2022[2]). However, consultation with them, the private sector, citizens and international organisations can enhance the quality of the advice and strengthen the credibility and inclusiveness of the council. To include this dimension, Luxembourg could draw inspiration from the way Australia's National COVID-19 Coordination Commission operated during the crisis, with support from a board composed of representatives from all sectors, including non-profit organisations.

Secondly, transparency about the choices made in the composition of scientific advisory bodies, members’ declarations of private interest, and the bodies’ decision-making processes is crucial when authorities are confronted with health risks characterised by a high degree of uncertainty. This requires formal processes for consulting scientific committees and making decisions, and for such bodies to be transparent and have integrity (OECD, 2022[2]). In Luxembourg, the COVID-19 Task Force was mobilised informally based on an initiative from the research sector, so there was no transparency in the choices made regarding the composition of this body. Furthermore, decision-making processes were not subject to a clear ex ante process (who provides advice? Who makes decisions? Is the decision made by consensus, by majority, etc.?). This transparency and the establishment of explicit processes are all the more important to clarify the role of the scientific council with regard to political decision making, and to deal with cases of divergent opinions within the scientific community. In the future, Luxembourg could consider more clearly defining the mandate of the COVID-19 Task Force or any scientific advisory body by establishing a mandate or mission statement, as well as clearly defining the decision-making processes.

The transparency of scientific expertise could be increased

The scientific evidence that informs the policy response to COVID-19 is inherently incomplete and conditional. In such a dynamic situation, when policy makers and the public want assurance and certainty, the scientific community faces a real challenge. On the one hand, it may be difficult to reach a consensus. On the other hand, communicating uncertainties and alternative viewpoints to citizens may affect public trust in scientists and politicians.

In this context, many countries have controlled the nature and volume of the information made public. As a result, the publication of scientific advice is rarely systematic and often remains at the discretion of the government in OECD member countries. This was the case in Luxembourg, where most, but not all, of the Task Force's opinions were published online at www.researchluxembourg.org/en/covid-19-task-force/. Moreover, the Task Force chose not to publish dissenting opinions in order to ensure that the scientific advice given to the government was coherent.

Publishing dissenting opinions and systematically publishing opinions to the government strengthens the legitimacy and credibility of the scientific advice among the public. Maintaining transparency about the data behind scientific advice and which scientific advice is followed by governments promotes citizen confidence. To this end, the OECD Recommendation advises that governments ensure transparency with respect to the information used in decision making to promote stakeholder acceptance of the risk management decisions taken (OECD, 2021[11]). In particular, this requires governments to ensure transparency with regard to the assumptions that underlie analyses of scientific advice, as well as the uncertainties associated with them.

Luxembourg could follow the example of some other countries and publish the minutes of COVID-19 Task Force meetings and the opinions expressed. In Ireland, for example, the National Public Health Emergency Team is the official mechanism for co-ordinating the response of the health sector. It aims to facilitate the flow of information between the Department of Health and its agencies and provides a forum for coming to a consensus on strategic approaches to the crisis. Its meeting agendas are routinely posted on the Department of Health website, alongside meeting minutes, which include dissenting opinions and the actions and policies discussed (OECD, 2020[8]). This best practice could serve as inspiration for the COVID-19 Task Force in Luxembourg.

3.3. External crisis communication in Luxembourg

The OECD Recommendation of the Council on the Governance of Critical Risks advises governments to communicate risks to the public using targeted messaging, and methods tailored to different audiences, while ensuring that the information provided is accurate and reliable (OECD, 2014[3]). In this sense, the Recommendation stresses the importance of crisis communication, understood as communication from the government to the public and stakeholders on the evolution of the crisis and the actions to be taken in response to a risk that has materialised. Such communication should be targeted, adapted, accessible, precise and coherent (OECD, 2016[20]). In Luxembourg, as in many other OECD member countries, it has sometimes been difficult to strike this balance, given the fast-changing nature of the health measures to be communicated.

3.3.1. Luxembourg used a wide variety of channels, which allowed it to reach a large audience and to be attentive to citizens' expectations

During the coronavirus crisis, OECD member countries generally understood the importance of clear and coherent communication in responding to the crisis. In the face of a pandemic, whether or not the public accept the decisions taken has direct consequences on whether the mitigation measures imposed are followed and whether the fight against the effects of the virus is effective. As a result, governments greatly increased the frequency of their external communications to the public, using a variety of channels, ranging from press conferences and social media to online databases (OECD, 2020[8]).

In Luxembourg, the government made great efforts to communicate quickly and extensively on various channels to ensure its crisis communications reached as many people as possible. This initiative was consistent with the crisis communication strategy set out by the government in advance of the 2020 pandemic (Government of Luxembourg, Ministry of State, 2016[21]). Initially, the government used traditional crisis communication channels, such as the media, radio and television. As soon as the first cases were detected, press releases detailing the situation and its evolution were relayed to the print media. As the virus progressed, communication also accelerated both through press conferences streamed live to the public and via other media (print, radio, etc.). To encourage people to follow the public health rules in place, the government also put up posters in public places and throughout Luxembourg, for example in bus shelters.

The most important messages were also relayed on the social media pages of ministries and political figures, at www.covid19.lu and on the Telegram account of the Health Directorate, which was used to issue urgent communications to health professionals. Using social media is particularly important in a world where false information is widely shared by a large number of sources (OECD, 2015[1]); social networks have a key role to play in combating misinformation that threatens compliance with the emergency measures adopted (OECD, 2020[22]). However, traditional modes of communication cannot be ignored, as some population groups do not use social media. The combined use of social networks and traditional media, as was the case in Luxembourg, is best practice for public communication in times of crisis (OECD, 2020[22]; OECD, 2020[8]). To summarise, mass communication through a wide variety of channels enabled Luxembourg to relay public health instructions to as many people as possible.

In addition to this top-down communication from the government to the population and stakeholders, Luxembourg also made use of some two-way communication. A hotline was set up at the beginning of March 2020 to answer questions from citizens and, later, from companies on how to deal with the virus. This hotline allowed the government to not only answer citizens' questions, but also to develop a deeper understanding of the population's concerns. While crisis communication has traditionally favoured a top-down approach, with messages sent from the executive branch to citizens, this type of two-way communication can promote dialogue and help the authorities understand the questions and concerns of the population. The Luxembourg government also used other two-way communication tools such as Facebook Live and an email helpdesk, which were able to serve as an indicator of how communications were being received by the population and if there was a need for any additional information. Using this information, communication could be continuously adapted and improved.

It is imperative that Luxembourg pursues this approach when communicating other crises in the future, and it should also consider extending it to other channels. Some OECD member countries, such as France, for example, have set up WhatsApp accounts to both communicate key information to the population and to listen to their concerns and reactions to public health instructions (OECD, 2020[22]).

3.3.2. Luxembourg's crisis communication benefited from messaging adapted to different audiences but may have suffered from a lack of coherence

When citizens' expectations are at their highest, public communication must find the right words to give meaning to events (OECD, 2021[11]). This mission of meaning also refers to the capacity of the public authorities to address different populations by adapting messages to their different expectations, and to demonstrate the scientific rationale behind the emergency decisions taken. In Luxembourg, crisis communication was largely adapted to different audiences, supported by clear leadership and developed with the help of the scientific community, but may have suffered from a lack of coherence at times.

The first factor in creating meaning is clear messaging, supported by strong leadership, throughout the crisis. Leadership plays a major role in crisis communication, in that public authorities must convey messages that meet the public's legitimate need to know what is happening and what to do, while taking care not to create expectations that cannot be met (OECD, 2020[8]). In Luxembourg, crisis communication was managed in close consultation between the Ministry of State, the Ministry of Health and the Health Directorate during the first phase. The government spokesperson was endorsed directly by the Prime Minister and the Minister for Health during press conferences. While the Ministry of Health and the Health Directorate gradually took over the co-ordination of communication from summer 2020 onwards, the Ministry of State remained the main player in acute phases, such as during the second wave of the pandemic in autumn 2020.

The use of clear language and personalised communication materials are also essential to create meaning and share complex information with different segments of the population. Like other OECD member countries such as Sweden, Belgium and the United States, Luxembourg therefore chose to produce communication materials in several languages – in the country's three official languages and in certain other languages frequently used by cross-border communities. This proactive strategy allowed the messages to reach as many people as possible in their native language. OECD data shows that tailoring communication materials is one of the most effective ways to share complex information with different segments of the population (OECD, 2022[2]).

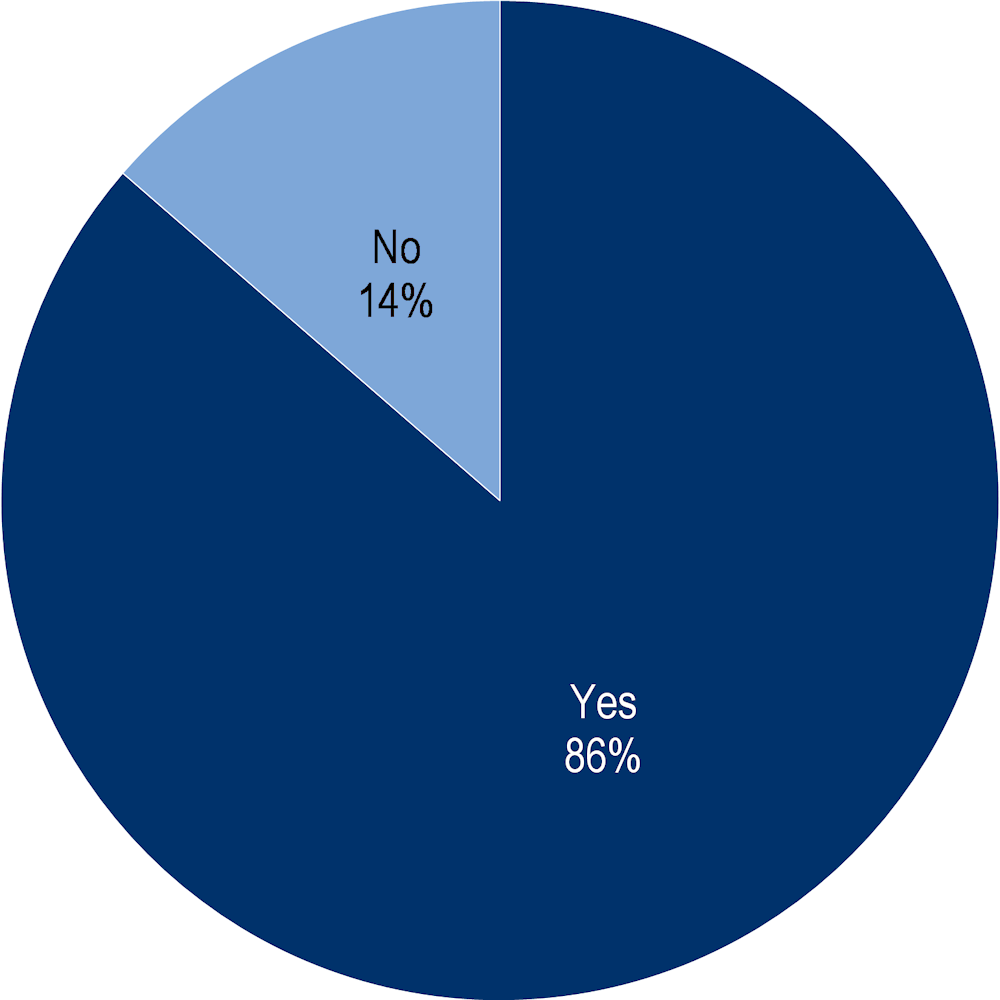

Despite this leadership and the high degree of personalisation of messages in Luxembourg, crisis communication sometimes lacked coherence. This challenge was not specific to Luxembourg, as OECD data shows that 12 out of 26 (46%) CoGs faced difficulties ensuring public communications were coherent during the COVID-19 crisis (OECD, 2021[11]). Aware of this challenge, the government of Luxembourg sought to equip municipalities with tools that would allow them to relay the main messages as closely as possible to the local population while maintaining coherence across regions. This government support was received very positively by the municipalities, 86% of which felt that it was sufficient to help them communicate with the general public (OECD, 2020[22]).

Figure 3.3. The tools made available to the municipality by the government to relay crisis communication messages were effective

Note: n = 44 out of the 102 municipalities that were sent the survey.

Source: OECD (2022[23]), OECD survey of municipalities on COVID-19 management.

Despite these tools and the existence of an explicit communication strategy, the Luxembourg government encountered difficulties with the coherence and clarity of messages about measures to contain the spread of the virus. As has been the case in other OECD member countries, the increased frequency of communication and quick changes in public policy have sometimes resulted in confusing messages that may have hindered the creation of meaning, and thus prevented mitigation and recovery measures from being effective. This was partly due to the rapidly changing state of scientific knowledge, as well as the huge number of different rules in place in the lockdown-easing phases and during the successive waves of the virus. Yet, OECD data show that clear and coherent communication is essential during emergencies to gain public trust and ensure people comply with the rules in place (OECD, 2022[2]).

To reduce confusion and build trust in government measures, it is important to state the scientific and technical arguments behind the health advice issued. In addition, the OECD Principles of Good Practice for Public Communication Responses to Mis- and Disinformation emphasise the importance of transparency and honesty in communication (OECD, 2022[2]; OECD, forthcoming[24]). Luxembourg has made efforts towards this by involving health professionals (doctors, virologists, scientists, etc.) in its communication campaigns, particularly with regard to vaccination. However, some communications related to the easing of lockdown and mask-wearing rules could have been accompanied by more scientific and technical explanations. In order to ensure that its messages were well received by the public, Luxembourg could have more systematically tested the effectiveness of its communication measures.

3.4. The involvement of society as a whole in crisis management in Luxembourg

OECD data show that in the event of a new and complex crisis, government crisis management must be complemented by agile partnerships with a broad network of stakeholders (OECD, 2018[5]). The OECD Recommendation of the Council on the Governance of Critical Risks, for example, advises countries to

"Engage all government actors at [the relevant] national and sub-national levels, to coordinate a range of stakeholders in inclusive [crisis management] policy making processes."

This is all the more true as the public authorities currently co-exist with an increasingly large network of actors and are facing increased pressure from society and the media. As a result, traditional approaches to crisis management based on command and control procedures are no longer sufficient. New and complementary approaches are needed to deal with the unexpected and respond to unprecedented shocks. This means that governments must conduct networked, society-wide crisis management, which involves working with subnational public entities and stakeholders from the private sector, the research community and civil society, as well as implementing policies to ensure the continuity of the nation's democratic life.

In Luxembourg, the government has become very aware of this need and has made significant efforts to mobilise a very wide range of stakeholders in its management of the crisis, including the private sector, the municipalities and even certain civil society organisations. However, more active consultation with civil society organisations is desirable to enable them to play a real role in decision making. The same applies to citizens who were not involved in crisis management at all.

3.4.1. Central government co-ordination with local stakeholders was generally effective, although sometimes late

OECD data suggest that subnational authorities were often at the forefront of the COVID-19 crisis insofar as they are often responsible for health, social welfare and transportation services. Co-operation between central and local governments was therefore both essential and complex in many member countries, since local situations differ from one subnational authority to another (OECD, 2020[25]).

In Luxembourg, however, local authorities have played a much smaller role in crisis management than in some other countries due to its geographical size and the fact that these local authorities (the 102 municipalities) have limited powers. Since the law of 27 March 2018 on the organisation of civil security and the creation of the Grand Ducal Fire and Rescue Corps, all national rescue services actors have been brought together as part of a national public establishment and the municipalities are no longer responsible for this matter. As a result, it was not necessary to involve the municipalities in the national crisis unit, as was the case in other OECD member countries. In Austria, for example, the National Crisis and Disaster Management committee co-ordinated the response between federal ministries, provinces, aid agencies and the media (OECD, 2020[8]).

Despite Luxembourg's high level of centralisation, however, the municipalities had to be mobilised for crisis management, both because of some of their own responsibilities (management of public records, some parts of social assistance, disposal of contaminated waste from hospitals, etc.), and to enable them to relay the actions of the national government (see Box 3.10 for more information on the role of municipalities and cities in crisis management in Luxembourg).

Box 3.10. The role of Luxembourg's municipalities and cities in crisis management

Compared to other OECD member countries, subnational authorities played a relatively limited role in managing the COVID-19 crisis in Luxembourg, focusing mainly on maintaining essential communal services, such as drinking water distribution, household waste, public records, urban planning, etc.

However, the 102 municipalities and cities in the country were able to play an important role in relaying the actions of the national government, by:

sharing prevention messages related to crisis management (preventive measures to be followed, areas where masks should be worn, etc.).

helping to distribute masks

establishing certified antigen test centres

helping to set up vaccination centres, in particular by:

providing administrative staff

providing reception facilities

providing logistics and IT support.

Source: Authors based on (OECD, 2022[15]), OECD information-gathering questionnaire for the Luxembourg Crisis Management Evaluation.

This crucial role was understood very early on by the Luxembourg government, which actively communicated with the municipalities and, more particularly, with the Association of Luxembourg Cities and Municipalities (SYVICOL) to relay the information needed for crisis management. As such, the Ministry of Home Affairs systematically relayed and explained national decisions through circulars sent to the municipalities, SYVICOL and communal public facilities. These circulars were also the subject of regular meetings between SYVICOL and the Ministry of Home Affairs to answer questions from burgomasters (municipality leaders) on the application of the national rules.

Forms of two-way vertical co-ordination were also put in place to allow the municipalities to ask questions about the application of country-wide measures. For example, the Ministry of Home Affairs and the Ministry of Health set up a 24/7 point of contact for burgomasters at the Health Inspectorate to improve communication between the national authorities responsible for public health and the municipalities. This contact was accessible by phone and by email.

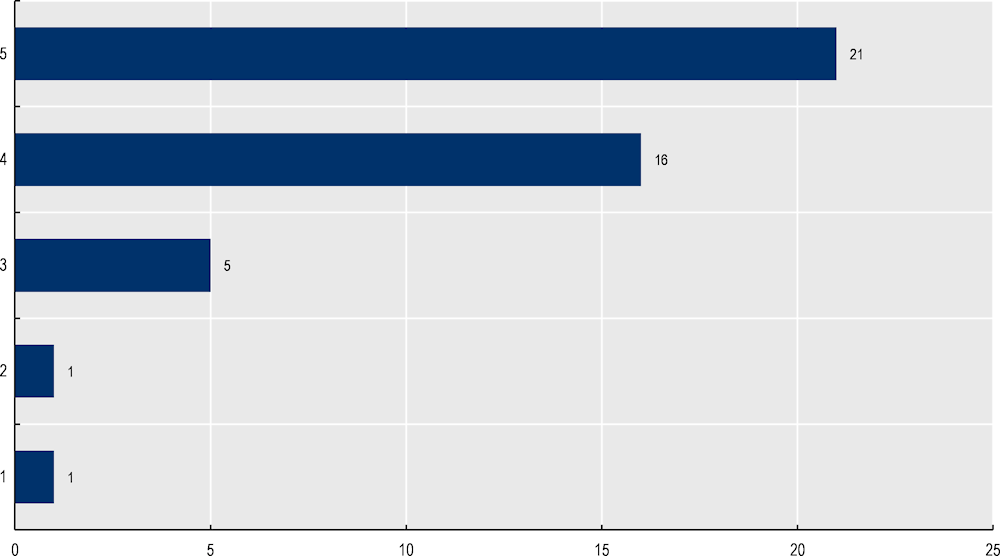

Finally, in order to amplify the effects of crisis communication for citizens, the Ministry of Home Affairs created a toolbox, available online, made up of communication tools (leaflets, icons, videos, etc.) to help municipalities relay the government's prevention messages. All of these measures were highly appreciated by the municipalities, the vast majority of which felt that they were effective in helping them fulfil their role as relays in crisis management (see Figure 3.4).

Figure 3.4. Effectiveness of the measures made available to municipalities by central government to support local crisis management

Note: n = 44 out of the 102 municipalities that were sent the survey.

Source: OECD (2022[23]), OECD survey of municipalities on COVID-19 management.

However, as in other OECD member countries, getting the right information to the local level or to front-line staff (such as police forces) in a timely manner may have been a challenge for the Luxembourg government in its response to the crisis (OECD, 2022[2]; OECD, 2022[15]). The same applies to the application of sometimes complex and evolving national rules, as discussed in section 3.3 of this chapter on crisis communication. These contextual factors, linked to the rapid evolution of the epidemiological situation and to rule changes, are however not specific to Luxembourg, and the very frequent communication between the Ministry of Home Affairs and the municipalities was able to somewhat limit the negative effects. Chapter 5 of this report provides more information on vertical communication between the national government and the education sector as a whole.

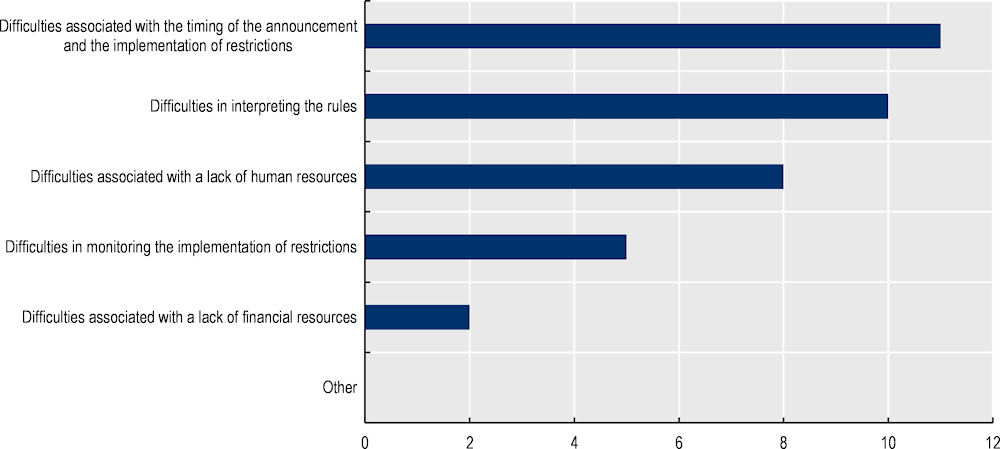

Figure 3.5. Key challenges in implementing and adapting national restrictions related to COVID-19

Note: n = 36 out of the 102 municipalities that were sent the survey.