This chapter focuses on the evaluation process itself, from decisions on which evaluations to undertake to how findings are disseminated. Data show that organisations are putting increased emphasis on the early stages of the evaluation process to ensure high-quality end products that respond to evolving organisational priorities. The chapter also explores how the COVID-19 pandemic prompted innovative ways of working. Finally, it analyses how organisations collaborate with partner countries on evaluations – an area where there is room for improvement.

Evaluation Systems in Development Co-operation 2023

4. Evaluation processes

Abstract

4.1. Evaluation plans

Planning for evaluation is important to ensure evaluations reflect organisational priorities. An evaluation plan or work programme sets out the evaluations that will be conducted over a specific timeframe. These plans may also include supporting activities, such as training, capacity building, knowledge sharing and communications (OECD, 1991[1]). Our survey shows that 94 % of evaluation units prepare evaluation plans (46 out of 49 reporting organisations), and all but four reporting evaluation units publish their plans – providing useful transparency about their work.

Several members report adjusting their ways of working to ensure that the evaluation topics chosen are aligned with organisational priorities. For example, Norway and Germany both hold consultative meetings with senior management and staff in their respective ministries to identify topics of interest. In line with the findings of previous studies in this series, evaluation plans generally reflect the organisations’ strategic plans and priorities (OECD, 2010[2]; 2016[3]). The following issues were most frequently cited by survey respondents as guiding evaluation decisions: (i) issues of thematic interest; (ii) relevance of an initiative or area to the overall portfolio of an organisation; (iii) the level of ODA committed to an initiative or area; (iv) timeliness related to ongoing planning or review processes; (v) gaps in evidence; (vi) evaluation resources and capacity available; and (vii) possible collaboration with partners.

Using a consultative approach to design evaluation plans ensures they are useful. Many interviewees report that in designing evaluation plans, consultations are organised with management, programme and operational staff and advisory boards, as applicable. The aim is to identify relevant evaluations that will provide timely evidence on priority areas. This approach also helps to strengthen buy-in across the organisation, which will help ensure the findings are used. This is a shift from past practice, where the emphasis was on safeguarding evaluation plans from outside influence and programme staff were often kept at arm’s length to avoid bias in the selection of evaluation topics. Today, many EvalNet participants report taking a more consultative approach, further demonstrating the increased emphasis on using and learning from evaluations.

Based on responses, evaluation programming and planning seems to be an area where EvalNet participants’ practices have matured and are generally functioning well. However, the data do not allow us to draw conclusions on how successful they are overall in addressing the most relevant priorities (either for their own organisations or collectively for the DAC). A more comprehensive approach to develop and implement ongoing learning agendas across development partners for particular topics – such as one sustainable development goal – is one useful way to ensure evidence is generated systematically to address decision making priorities.

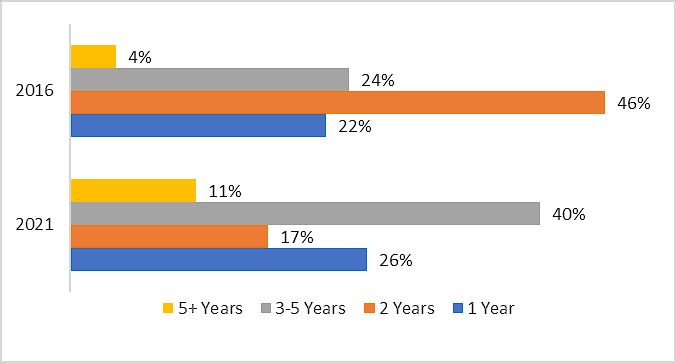

The time period covered by evaluation plans has increased since 2016, reflecting the greater focus on strategic evaluations integrated with organisational priorities. In 2016, the majority of evaluation work plans covered a one to two-year timeframe. This has increased to an average of three years in 2021 (Figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1. Duration of evaluation work plans, 2016 vs 2021

Note: Data on evaluation plans were reported by 44 out of 51 participating organisations.

4.2. Evaluation design

Each evaluation requires a focused design process to ensure it will produce robust and credible findings and meet organisational needs. There is no one-size-fits-all approach to evaluation. Rather, evaluation units draw on various approaches and methodologies depending on the specific context and objectives of an evaluation. As noted in Chapter 3, global and organisation-specific guidance supports evaluators in designing evaluations that are fit for purpose. This guidance is complemented by evaluability assessments (Box 4.1 gives an example from Australia), which are a key tool for enhancing the quality, feasibility and cost-effectiveness of evaluations.

Strong terms of reference (ToRs) are a key component of high-quality evaluations. Dialogue with the intended users, such as while developing the ToR, can also ensure evaluations are relevant and answer priority questions. During the survey and in EvalNet discussions, participating organisations highlighted that high-quality ToRs help set the stage for robust evaluations. These ToRs often include the evaluation objectives, approach/methodology, evaluation questions, quality assurance mechanisms, and roles and responsibilities. As with the evaluation planning process, increased effort is being made to consult relevant staff in the preparation of ToRs, seeking their input on evaluation questions that will provide the most useful evidence.

Box 4.1. Evaluability assessments in Austrian development co-operation

In 2022, Austria developed a Guidance Document on Evaluability Assessments to support the planning, implementation, and use of evaluability assessments in Austrian development co-operation. The document provides practical guidance and tools for assessing evaluability along four dimensions: (i) the quality of the intervention design; (ii) the availability of relevant data; (iii) the perceived usefulness of the evaluation by relevant stakeholders; and (iv) its feasibility in the temporal, geographical and institutional context. It also describes practical aspects of evaluability assessment and outlines individual steps in the implementation process. The guidance can be applied for assessing the evaluability of a range of interventions – strategies, policies, programmes, projects – and at different points of time in an intervention cycle: during the design phase, immediately after approval, prior to commissioning an evaluation, or as the first step of an evaluation.

Source: Austrian Development Agency (2022[4]), Evaluability Assessments in Austrian development cooperation: Guidance Document, https://www.entwicklung.at/fileadmin/user_upload/Dokumente/Evaluierung/GL_for_Evaluability_Assessments.pdf.

4.3. Conducting evaluations

Challenges cited in conducting evaluations include lack of resourcing, weak staff capacity and technical capacity of evaluators, lack of availability of data, and low support from senior management for a learning culture. While larger organisations reported fewer issues around resourcing and capacity, the quality of external evaluators and lack of data were common challenges raised across evaluation units.

Smaller bilateral organisations face the most challenges with external evaluators. As noted in Chapter 3, multilateral organisations often have larger centralised evaluation units than bilateral organisations. Organisations with fewer staff, understandably, rely more on external consultants in conducting evaluations. However, it can be challenging to find consultants with the right combination of relevant expertise to conduct high-quality evaluations.

Competitive procurement processes help select good external evaluators, but are not always sufficient to ensure high quality work. Efforts are made to set strong selection criteria, in line with well developed ToRs, in order to find consultants who will be able to deliver on the objectives of the evaluation. Often, a multi-stakeholder reference group is also established to support the evaluation and to select a qualified team. It is usually chaired by an official from the organisation but who is not directly engaged in the project to be evaluated.

The quality of evaluations is linked to strong results systems. Evaluation units regularly highlighted the lack of reliable and timely data as a major challenge in conducting evaluations. Results systems set the stage for better monitoring and data collection, which in turn allows for better evaluations (UNDG, 2011[5]). If results systems do not support the collection of necessary data, evaluations must gather more primary data or rely on external sources to manage data gaps, both of which require additional time and resources.

Evaluation units increasingly engage results teams. Participants report that given the importance of results data to inform evaluation, they are deepening collaboration with their organisation’s results teams. As described by interviewees, this often involves senior evaluation officials providing insights on results strategies and frameworks, as well as participating in internal working groups dedicated to strengthening results measurement systems and tools.

4.4. Evaluation in the context of COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic had a significant impact on how evaluations were conducted. On-site data collection and in-person engagement with stakeholders were no longer possible in many contexts. It was particularly difficult to work with local partners who did not have the capacity or resources to engage virtually. Because of this, many evaluations were interrupted, postponed, or cancelled.

New ways of working were explored to ensure the critical evaluation function was fulfilled during the crisis. This included working more with local evaluators, virtual data collection, secondary data analysis, and increased collaboration with partners to overcome challenges. Such ways of working were being tested before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, but their use was accelerated because of the crisis. During EvalNet meetings, most members report that they will continue to use virtual engagement and data collection methods.

“The pandemic has complicated the collection of data, but the situation has also provided an opportunity for valuable testing and the development of methodological approaches to data collection, including the use of machine learning and satellite data.”Norway, Department for Evaluation

More than three-quarters of participating organisations relied on local consultants to conduct evaluations during the pandemic. With their staff unable to travel, evaluation units engaged local evaluators to support in-country data collection and stakeholder engagement. Local evaluation organisations – such as the Mongolian Evaluation Association – reported increased demand and growing momentum in their national evaluation capacity development due to the travel restrictions. However, many organisations reported challenges in identifying evaluators with the right expertise to deliver high-quality work. Some also raised concerns that virtual methods and reliance on local partners could reduce the quality of evaluations. As noted, identifying suitable, qualified consultants – whether or local or international – is a widespread challenge for evaluation units.

“We – the Mongolia Evaluation Association – are really a product of COVID, I would say, because before COVID in Mongolia, it was mostly international evaluators flying in, and we acted only as local data collectors or working in the shadows. However due to flight restrictions, they were not able to come, and we took on a bigger role.”National partner from the Mongolian Evaluation Association

Virtual engagement and data collection were key for conducting evaluations during the pandemic. Remote assessment guidelines, along with training for evaluators, helped support the switch to online interviews and virtual data collection. In addition to ensuring evaluations could continue despite the pandemic, in some cases this also helped to gain broader participation in evaluation processes. For example, the ADB’s evaluation team working on its real-time pandemic response evaluation was able to interview more than two dozen ministers of finance (virtually), many more than would normally be the case. Participating organisations noted, however, that there is still value in conducting in-person evaluations, and that the quality of engagement is better in-person. In short, virtual interviews have an advantage of quantity over quality.

Big data was used to supplement evaluation-specific data collection in the constrained COVID-19 context. Big data refers to data characterised by high volume, velocity, and variety (OECD, 2021[6]). While virtual data collection was used to support many evaluations during the pandemic, participating organisations also reported the increased use of big data to complement and validate findings. Examples of big data sources used include country-owned administrative data, satellite imagery, and data on weather patterns and other characteristics of the natural environment (Box 4.2).

The COVID-19 pandemic also highlighted the critical importance of collecting real-time evidence to strengthen crisis response. During the pandemic there was an urgent need for evidence on which response and recovery measures were working and which did not, in order to scale up successful approaches. Evaluation units therefore shifted their focus from lengthier ex-post evaluation processes to generating early evidence and producing brief knowledge products to guide ongoing efforts. There was also a huge increase in rapid syntheses early in the pandemic, drawing lessons from past evaluative work to quickly inform the ongoing response, as discussed during EvalNet’s June 2020 meeting.

Participation in the COVID-19 Global Evaluation Coalition supported more co-ordinated efforts and sharing of data and evidence. The COVID-19 Global Evaluation Coalition was established by EvalNet members, partner countries and members of the UN Evaluation Group (UNEG) and the Evaluation Co-operation Group (ECG) of the multilateral development banks in 2020 to bring stakeholders together to share lessons and ensure that the global humanitarian and development communities are able to deliver results, even during times of crisis (COVID-19 Global Evaluation Coalition, 2020[7]). The COVID-19 Global Evaluation Coalition developed a new way of working1 to produce five rapid “Lessons from Evaluation” briefs (2023[8]), which were submitted to meetings of development ministers.

Box 4.2. Innovations in evaluation sparked by the COVID-19 pandemic

Satellite imagery in Kenya

The African Development Bank’s Independent Development Evaluation unit adapted its data collection techniques during the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, during the evaluation of the Last Mile Electricity Connectivity Project (LMCP) in Kenya in 2021, it drew on satellite images to assess progress.

Artificial intelligence for development analytics

UNDP’s Independent Evaluation Office, in partnership with the United Nations International Commuting Centre and Amazon Web Services, developed a cloud-based tool to review and extract key information from evaluation reports and other documents. The Artificial Intelligence for Development Analytics (AIDA) tool uses artificial intelligence and machine learning to search for specific information within more than 6 000 evaluation reports. AIDA identifies lessons from evaluations and displays them on a dashboard organised by country, sector, theme, modality, and timeframe.

Crisis response repositories

ADB’s Independent Evaluation Department launched an online repository of evaluation evidence related to crisis response and recovery, ensuring information on challenges and solutions were readily available to inform COVID-19 response. Similarly, the European Commission developed the EvalCrisis web platform, which hosts a collection of resources on conducting evaluations in times of crisis. The platform includes guidance documents, training webinars, blogs and podcasts.

Joint evaluations

Working through the COVID-19 Global Evaluation Coalition, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the Governments of Colombia, Finland and Uganda, and the Active Learning Network for Accountability and Performance (ALNAP), conducted a joint evaluation focused on how host states, development organisations, and non-state actors ensured the protection of refugee rights during the pandemic.

Real-time evaluation

The Islamic Development Bank’s Independent Evaluation Department undertook a real-time evaluation of the Bank’s COVID-19 Strategic Preparedness and Response Program. The evaluation used an amended version of the OECD evaluation criteria involving five different lenses: relevance, coherence, agility and responsiveness, effectiveness, and efficiency. The data collection methodologies used included virtual interviews, remote focus discussions, and online surveys. The evaluation provided timely feedback that guided operational improvements through mid-course adjustments as the programme moved into the next phase of the crisis response. It used evidence and drew lessons gleaned from the experience to identify opportunities for improvement, presented lessons learned, and offered guidance on the way forward.

Source: ADB (2020[9]), COVID-19 Response Resources, https://www.adb.org/site/evaluation/evaluations/covid-19-response; IEO, World Bank (2020[10]), Evaluation in the Age of Big Data: Prospects and Challenges for Independent Evaluation, https://ieg.worldbankgroup.org/event/datascience-and-evaluation.Taylor, G. et al. (2022[11]), Joint Evaluation of the Protection of Rights of Refugees during the COVID-19 Pandemic, https://www.covid19-evaluation-coalition.org/documents/Final%20Report%20 %20Refugees%20Rights%20During%20The%20Covid%2019%20.pdf.

4.5. Quality assurance

A focus on quality assurance is apparent throughout the full evaluation process. Quality assurance is not only a final step in the evaluation process. Evaluation units systematically integrate quality assurance checks at each stage of the evaluation process, including defining objectives, deciding methodology and approach, designing ToRs, procuring consultants and drafting and reviewing inception and final reports (Box 4.3). Several participants report recently conducting reviews of evaluation quality, including France, Japan, Norway, Sweden and ADB.

Independent entities are used to assess the quality of evaluation-related documents and products. All but eight members and observers have some kind of independent oversight entity, such as advisory bodies or steering committees, to provide regular quality checks. These entities often include representatives of relevant policy or programme teams, subject-matter specialists and external advisors with expertise in development evaluations. Independent entities review and provide input on context, methodological approach, data accuracy and analysis, overall findings and recommendations.

Each evaluation unit has its own quality procedures in place, and all but a handful require an independent quality assessment before approval and publication of evaluation reports. These quality assessments use the Quality Standards for Development Evaluation (OECD, 2010[12]) to determine the quality and credibility of an evaluation.

Box 4.3. Quality assurance in Sweden’s evaluations

Sweden’s Expert Group for Aid Studies’ (EBA) quality assurance process rests on widespread recognition of the properties required of a good evaluation, including utility, accuracy, and feasibility. However, the EBA recognises that it isn’t enough for an evaluation to only possess these qualities – it must also use probing questions to bring new knowledge to the field.

EBA therefore places an emphasis on factual questions when assessing quality and aims to avoid methodological reductionism: the questions come first, and the choice of scientific method comes second. The quality assurance process must be designed such that the properties that constitute quality can be tailored and adapted to different contexts. The quality assurance process is guided by the Expert Group, with the process involving a number of factors to ensure the quality of an EBA report at each stage (Table 4.1). The focus is on the elements that the Expert Group and the secretariat are able to influence.

Table 4.1. EBA’s quality assurance process

|

1. Assessments of and decisions on study proposals |

2. The process of reference group meetings |

3. Expert Group’s decision on publication |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

4.6. Working jointly

Fewer joint evaluations have been undertaken since 2010. Joint evaluations increase efficiency, improve credibility, reduce the burden on partner country governments and implementing partners, and create more opportunities for mutual learning (OECD, 2006[13]). Despite these well-known benefits, the share of joint evaluations undertaken by participating organisations has declined significantly since 2010, when nearly a quarter of all evaluations were joint (Figure 4.3).

Of the 2 321 evaluations undertaken by participating organisations in 2021, only 77 were conducted jointly, a slight increase from 2016. UNDP conducted the most (63 joint evaluations), followed by Australia’s DFAT (5), France’s MEAE (3), Norway’s Norad (2), Canada’s GAC (1), Germany’s BMZ/DEval (1), Sweden’s Sida (1) and Switzerland’s SDC (1). The remaining 36 organisations (out of 44 reporting organisations) reported that no joint evaluations took place in 2021. Meanwhile, partners in the United Nations Evaluation Group report that they are seeing a huge increase in the proportion of joint work in their portfolios, reflecting in part the ONE UN reforms (DAC, 2021[14]).

Figure 4.2. Share of joint evaluations undertaken by participating organisations, 2010 to 2021

Note: Data on joint evaluations were reported by 44 out of 51 participating organisations.

The general move away from joint evaluations and sharing evaluation plans is often attributed to limited staff resources. Collaborating across organisations, including participating in global initiatives such as EvalNet, requires an investment of time and effort. Participating organisations have noted that it is too challenging to engage in this way in the context of limited human resource capacity. This reflects broader trends in the development space, with many co-operation providers facing the need to respond to national priorities and a reprioritisation of the aid effectiveness agenda.

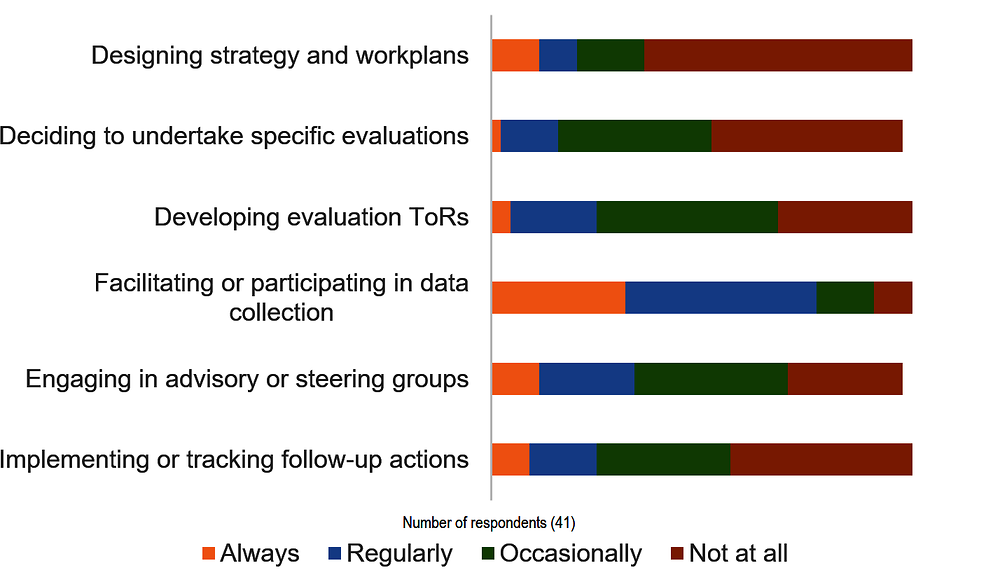

4.7. Partner country engagement

Partner country engagement in centralised evaluations remains low, despite commitments in this area. Partner country engagement in development co-operation, including in development evaluations, is important for ensuring local ownership of development activities and fostering mutual accountability. Partner country engagement in evaluations is also a way to strengthen local evaluation capacity (OECD, 2010[12]). The survey finds that partner country engagement is particularly low when preparing evaluation work plans, including deciding which evaluations to conduct within a specific timeframe (Figure 4.4). This may reflect the increasing attention paid to ensuring evaluations are aligned with organisational or domestic priorities.

Partner countries play a key role in stakeholder engagement and data collection. Over three-quarters of participating organisations (34 out of 44) reported that partner countries were always or regularly engaged in country-level data collection efforts, although the degree of engagement varies from active participation to facilitating connections.

Figure 4.3. Partner country engagement in evaluations

Note: Data on partner country engagement were reported by 41 out of 51 participating organisations.

4.8. Capacity strengthening

Evaluation units signal strong commitment to improving evaluation capacity across organisations and in partner countries. Given the importance of evaluation to strengthen accountability for results and inform future development efforts, significant emphasis is placed on strengthening the capacity of evaluation units, as well as of programme teams and partner country stakeholders. This support often draws on the standards, guidance and tools provided through EvalNet (OECD, 2022[15]).

Many reporting centralised evaluation units engage in capacity strengthening and quality assurance for decentralised evaluations. Centralised evaluation units are often tasked with providing technical support to staff working on decentralised evaluations, who are more often subject-matter experts than trained evaluators. This technical support includes training, advisory support during evaluation design and implementation, and providing quality assurance checks. Internal capacity strengthening often consists of training academies and online courses.

EvalNet participants are providing increased capacity support to partner countries through training programmes and knowledge exchange events (Box 4.4). Approximately three-quarters of participating organisations reported that they provide evaluation capacity building to partner country actors, including governments, evaluation societies, civil society, and individual evaluators. This is an increase from 2016, when half of respondents indicated that they provide support to partner country stakeholders.

Box 4.4. Member examples of building evaluation capacity

Training and courses

The Asian Development Bank (ADB), along with the Asia-Pacific Finance and Development Institute, finances the Shanghai International Program for Development Evaluation Training which trains government officials from ADB member countries to manage or undertake evaluations of projects funded by international finance institutions.

The Special Evaluation Office (SEO) within Belgium’s FPS Foreign Affairs is a leader in providing training to country-level partners. In partnership with the EGMONT Institute, the SEO organises evaluation training within partner countries. The SEO also funds an annual two-week intensive evaluation course, organised by the University of Antwerp, that brings together evaluation professionals from partner countries.

EvalNet members, including Germany, Switzerland and the Netherlands, support the International Program for Development Evaluation Training (IPDET). IPDET provides training to professionals in developing countries who commission, manage, practise or use evaluations.

Knowledge exchange

The African Development Bank (AfDB) is part of Twende Mbele, in partnership with CLEAR Anglophone Africa and six African governments (Benin, Ghana, Kenya, Niger, South Africa and Uganda). Twende Mbele is a network that facilitates collaboration in developing and implementing monitoring and evaluation systems.

Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs regularly hosts ODA Evaluation Workshops which bring together development partners and partner countries from the Asia-Pacific region for knowledge exchange and peer learning on development evaluation.

Source: SHIPDET (2022[16]), About SHIPDET, https://afdi.snai.edu/SAG_html.aspx?type=SHIPDET&h=5&l=English; University of Antwerp (2021[17]), Strengthening National Monitoring and Evaluation Capacities, https://www.uantwerpen.be/en/study/programmes/all-programmes/monitoring-and-evaluation-capacities/.

EvalNet members played a key role in establishing the Global Evaluation Initiative (GEI). GEI was established in 2020 to respond to high partner country demand for support for strengthening monitoring and evaluation systems. At the time, many EvalNet members and observer organisations, as well as regional and global evaluation initiatives, were providing individual support to their partner countries in this area. The GEI was established by the UNDP and the World Bank to consolidate these efforts, pooling resources for evaluation capacity building and leveraging the comparative advantages of individual organisations (UNDP, 2016[18]). GEI supports partner country governments in their efforts to improve national evaluation capacity, providing diagnostics, training, technical assistance and other support to local evaluation entities and professionals (GEI, 2022[19]). Today nearly half of participating organisations report that most of their evaluation capacity building in partner countries is channelled through GEI.

References

[9] ADB (2020), COVID-19 Response Resources, https://www.adb.org/site/evaluation/evaluations/covid-19-response (accessed on 24 August 2022).

[4] Austrian Development Agency (2022), Evaluability Assessments in Austrian development cooperation: Guidance Document, https://www.entwicklung.at/fileadmin/user_upload/Dokumente/Evaluierung/GL_for_Evaluability_Assessments.pdf.

[8] COVID-19 Global Evaluation Coalition (2023), Lessons from Evaluation, https://www.covid19-evaluation-coalition.org/lessons-from-evaluation/ (accessed on 2023).

[7] COVID-19 Global Evaluation Coalition (2020), COVID-19 Global Evaluation Coalition, https://www.covid19-evaluation-coalition.org/about/ (accessed on 24 August 2022).

[14] DAC (2021), Summary Record of the 25th Meeting of the DAC Network on Development Evaluation, Development Advisory Committee, OECD, Paris, https://one.oecd.org/document/DCD/DAC/EV/M(2020)1/En/pdf.

[19] GEI (2022), Global Evaluation Initiative, https://www.globalevaluationinitiative.org/who-we-are (accessed on 30 August 2022).

[10] IEO, World Bank (2020), Evaluation in the Age of Big Data: Prospects and Challenges for Independent Evaluation, https://ieg.worldbankgroup.org/event/datascience-and-evaluation (accessed on 24 August 2022).

[15] OECD (2022), Renewal of the Mandate of Network on Development Evaluation (EvalNet), OECD, https://one.oecd.org/official-document/DCD/DAC(2022)12/REV1/en.

[6] OECD (2021), Development Co-operation Report 2021: Shaping a Just Digital Transformation, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/ce08832f-en.

[3] OECD (2016), Evaluation Systems in Development Co-operation: 2016 Review, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264262065-en.

[2] OECD (2010), Evaluation in Development Agencies, Better Aid, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264094857-en.

[12] OECD (2010), Quality Standards for Development Evaluation, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264083905-en.

[13] OECD (2006), “Guidance for Managing Joint Evaluations”, OECD Papers, https://doi.org/10.1787/oecd_papers-v6-art6-en.

[1] OECD (1991), DAC Principles for Evaluation of Development Assistance, OECD Publishing, https://www.oecd.org/dac/evaluation/41029845.pdf.

[16] SHIPDET (2022), SHIPDET: About, SHIPDET, https://afdi.snai.edu/SAG_html.aspx?type=SHIPDET&h=5&l=English (accessed on 30 August 2022).

[11] Taylor, G. et al. (2022), Joint Evaluation of the Protection of Rights of Refugees during the COVID-19 pandemic, UNHCR, Geneva, https://www.covid19-evaluation-coalition.org/documents/Final%20Report%20-%20Refugees%20Rights%20During%20The%20Covid%2019%20.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2022).

[5] UNDG (2011), Results-based Management Handbook: Harmonizing RBM concepts and approaches for improved development results at country level, United Nations Development Group, https://unsdg.un.org/sites/default/files/UNDG-RBM-Handbook-2012.pdf.

[18] UNDP (2016), Evaluation and Independence - Existing evaluation policies and new approaches, United Nations Development Programme, New York, http://web.undp.org/evaluation/evaluations/documents/Independence_of_Evaluation.pdf.

[17] University of Antwerp (2021), Strengthening National Monitoring and Evaluation Capacities, https://www.uantwerpen.be/en/study/programmes/all-programmes/monitoring-and-evaluation-capacities/ (accessed on 30 August 2022).

Note

← 1. A first draft was produced by one member, then validated by other units with relevant work to add supporting evidence and triangulate findings. It was then published as a joint product.