Viet Nam stretches across the eastern part of mainland Southeast Asia. The country's economy continues to grow at a strong pace, and its level of human development, including income, life expectancy and education, is high. Population concentration and high fixed broadband penetration distinguish this country from its regional peers, which makes this report examine Viet Nam as a cluster of its own. The chapter outlines the geographic, economic and social conditions for broadband connectivity in Viet Nam. It proceeds by examining the performance and structure of the market and reviewing Viet Nam’s communication policy and regulatory framework, including broadband strategies and plans. It then reviews competition, investment and innovation in broadband markets; broadband deployment and digital divides; the resilience, reliability, security and capacity of networks; and the country’s assessment of broadband markets. It offers recommendations to improve in these areas.

Extending Broadband Connectivity in Southeast Asia

6. Extending broadband connectivity in Viet Nam

Abstract

Policy recommendations

1. Establish an independent regulatory body with remit over the communication sector.

2. Conduct regular competition assessments of relevant markets.

3. Implement reforms of state ownership in the communication sector and consider facilitating ownership by private entities.

4. Clarify co-ordination mechanisms between VNTA and VCC, where needed.

5. Consider lowering restrictions on private entities, both foreign and Vietnamese, to enter the market and invest to deploy networks, and eliminate FDI restrictions.

6. Reduce the administrative burdens associated with network deployment.

7. Facilitate co‑ordination of civil works and joint use of passive infrastructure.

8. Facilitate spectrum assignment and increase spectrum availability, especially for mobile communication services.

9. Leverage synergies between programmes to promote provision and adoption of connectivity services.

10. Take actions to improve the affordability of access devices.

11. Promote and invest in the improvement of digital skills.

12. Publish open, verifiable, granular and reliable subscription, coverage and quality-of-service data.

13. Promote measures to improve the quality and resilience of international connectivity.

14. Support and promote smart and sustainable networks and devices and encourage communication network operators to periodically report on their environmental impacts and initiatives.

15. Assess the state of connectivity regularly to determine whether public policy initiatives are appropriate, and whether and how they should be adjusted.

Note: These tailored recommendations build on the OECD Council's Recommendation on Broadband Connectivity (OECD, 2021[1]), which sets out overarching principles for expanding connectivity and improving the quality of broadband networks. The number of recommendations is not an appropriate basis for comparison as they depend on several factors, including the depth of contributions and feedback received from national stakeholders. In addition, recommendations do not necessarily carry the same weight or importance.

6.1. Geographic, economic and social conditions for broadband connectivity

Viet Nam occupies the eastern part of mainland Southeast Asia, stretching about 1 650 km from north to south and about 50 km wide from east to west at its narrowest point. Viet Nam’s main geographical features are the Nui Truong Son Ridge, which runs from northwest to southeast in central Viet Nam and dominates the interior, and two extensive deltas formed by the Hong (Red) River in the north and the Mekong (Cuu Long) River in the south. Between these two deltas is a long and relatively narrow coastal plain, although several spurs of the Nui Truong Son Ridge form sections of the coast.

This geography determines the distribution of the 98.5 million inhabitants (2021) (OECD, 2023[2]), who are mainly concentrated in the flat areas, especially in the two delta regions. Ha Noi and Hai Phong are the main urban centres in the north, Đà Nẵng City is the largest urban centre in the central region and Ho Chi Minh City is the country's main urban centre in the south. Urban centres account for the largest share of the population (41.6% in 2015) and 2.4% of the land mass (2015) (European Commission, Joint Research Centre, 2015[3]). 1 Outside of these urban areas, 39.3% of the population live in areas classified as urban clusters (2015), which account for 6.5% of the land mass (2015) (European Commission, Joint Research Centre, 2015[3]).2 19.1% of the population live in the less densely populated or rural areas, which account for 91.1% of the land mass (2015) (European Commission, Joint Research Centre, 2015[3]).3 These areas are located in the mountainous areas in the north and northwest, and along the central area of the country (European Commission, Joint Research Centre, 2015[3]).

In all regions, villages are usually located along rivers, canals and roads, forming a single elongated settlement. In the Hong River Delta and the central coastal plain, they tend to be densely clustered. In the Mekong Delta in the south, most settlements are loosely clustered farmsteads, some scattered among rice fields (Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 2023[4]).

Since the political and economic reforms (Đổi Mới) initiated in 1986, Viet Nam has undergone an economic transformation from a centrally planned economy to a “socialist-oriented” market economy. In the late 1990s, Viet Nam began to increase its participation in international fora such as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) and the World Trade Organization (WTO). Commitments under the series of Free Trade and Economic Partnership Agreements (FTAs) with its major trading partners have reinforced this reform momentum.4

Viet Nam's development record over the past 30 years has been remarkable. Since the late 1990s, the country's economy has experienced a strong upturn, driven by tourism, manufacturing and export earnings. Sustained by robust growth over the past decades, Viet Nam has transitioned from an agrarian to industrial economy (OECD, 2023[2]). Viet Nam’s average real gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate over 2017-21 was 5.4%, including over the COVID-19 crisis, compared to the OECD average of 1.5% (OECD, 2023[2]). Viet Nam’s GDP per capita reached USD PPP 13 284 by 2022, placing it sixth in the region, just ahead of the Philippines (USD PPP 10 497) and behind Indonesia (USD PPP 14 687) (IMF, 2023[5]).

Following its economic growth, Viet Nam ranks as a lower-middle income country (World Bank, 2023[6]). In May 2021, the Congress of the National Assembly approved the Five-Year Socio-Economic Development Plan (SEDP) 2021-2025 and the Ten-Year Socio-Economic Development Strategy (National Assembly, Socialist Republic of Viet Nam, 2021[7]; Congress of Viet Nam, 2021[8]). These plans set long-term economic goals to achieve upper-middle income status by 2030 and high-income status by 2045.

Viet Nam has also made significant progress in other areas of human development. Between 1990 and 2021, life expectancy at birth , mean years of schooling and expected years of schooling all increased in Viet Nam (UNDP, 2023[9]). Viet Nam classifies as a country with a “high” level of human development (see Table 6.1), along with Indonesia in the region (UNDP, 2022[10]).

Considering the socio-economic and demographic conditions that are closely related to broadband development, Viet Nam is considered a cluster in itself for this publication (see Chapter 1). This is mainly due to its high concentration of population in urban centre and urban cluster areas (41.6% and 39.3% of the population, respectively) (European Commission, Joint Research Centre, 2015[3]) and high fixed broadband penetration (21.7 subscriptions per 100 inhabitants, 2022 (ITU, 2023[11]), second in the region after Singapore.

Table 6.1. Human development (2021) and degree of urbanisation (2015), Viet Nam

|

Life expectancy (years, 2021) |

Expected years of schooling (children, 2021) |

Mean years of schooling (adults, 2021) |

Gross domestic product per capita (current prices, PPP, 2022) |

Population living in urban centres (%, 2015) |

Population living in urban clusters (%, 2015) |

Population living in rural areas (%, 2015) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Viet Nam |

73.6 (5) |

13.0 (7) |

8.4 (7) |

13 284 (6) |

41.6 |

39.3 |

19.1 |

|

OECD average |

80.0 |

17.1 |

12.3 |

53 957 |

48.8 (2022 data) |

28.11 (2022 data) |

23.11 (2022 data) |

Note: The numbers in parentheses refer to the simple ranking (i.e. no weighting) of SEA countries for each indicator. The OECD average for human development indicators is a simple average across OECD member countries. The urbanisation indicators for SEA countries refer to the population percentage in urban centres, urban clusters and rural areas, respectively. For the OECD, figures are given for the rate of the population living in predominantly urban, intermediate, and rural regions, respectively.

Source: [Human development indicators] UNDP (2022[10]), Human Development Report 2021/2022: Uncertain Times, Unsettled Lives: Shaping our Future in a Transforming World, www.undp.org/egypt/publications/human-development-report-2021-22-uncertain-times-unsettled-lives-shaping-our-future-transforming-world. [GDP per capita, SEA countries] IMF (2023[5]), World Economic Outlook Database, April 2023, www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2023/April (accessed on 28 June 2023). [GDP per capita, OECD] OECD (2023[12]), Gross domestic product (GDP) (indicator), https://doi.org/10.1787/dc2f7aec-en (accessed on 30 June 2023). [Urbanisation indicators for SEA] European Commission, Joint Research Centre (2015[3]), Global Human Settlement Layer (GHSL), https://ghsl.jrc.ec.europa.eu/CFS.php. [urbanisation indicators for OECD] OECD (2023[13]), OECD.Stat (database),” Regions and cities: Regional statistics: Regional demography: Demographic indicators by rural/urban typology, Country level: OECD: share of national population by typology”, https://stats.oecd.org/ (accessed on 28 August 2023).

6.2. Market landscape

6.2.1. Market performance

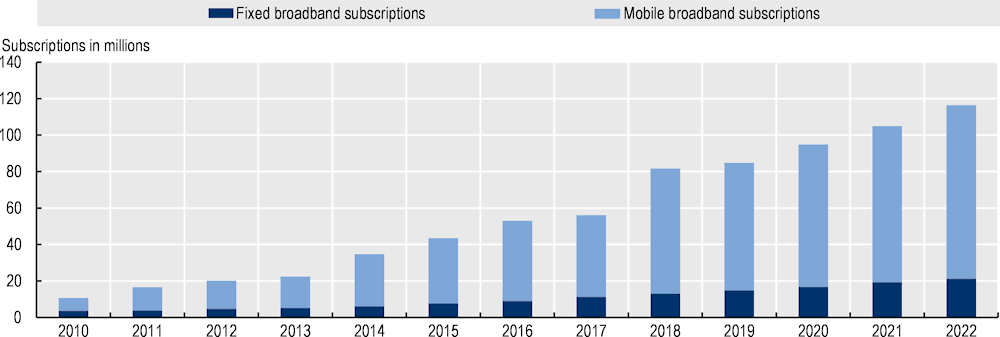

The number of broadband subscriptions in Viet Nam has grown significantly over the past decade, mainly driven by mobile broadband. The total number of broadband subscriptions surpassed 116 million in 2022, with mobile broadband accounting for 82% of total subscriptions (ITU, 2023[11]) (Figure 6.1).

Mobile broadband subscriptions grew at a high pace over the past decade (2010-22), averaging a year-on-year growth rate of 26.5% and reaching 95.2 million subscriptions in 2022 (ITU, 2023[11]). From 2013-14, mobile broadband subscriptions jumped 66.9%. In 2017-18, they rose again by 53.1%, which roughly corresponds to the network rollout of 4G networks between 2016-17 (see Figure 6.9) (ITU, 2023[11]). Fixed broadband growth is more moderate, but still shows steady year-on-year growth, averaging 16% between 2010 and 2022 and reaching 21.3 million subscriptions in 2022 (ITU, 2023[11]).

In terms of penetration, Viet Nam’s high fixed broadband subscription rate for the region stands out. Its 21.7 subscriptions per 100 inhabitants in 2022 is second in the region only to Singapore (27.4 subscriptions) and well above the regional average of 9.5 subscriptions (ITU, 2023[11]). Mobile broadband penetration in Viet Nam reaches 96.9 subscriptions per 100 inhabitants in 2022. It is, however, below the regional average of 103.7 subscriptions, ranking eighth in the region (ITU, 2023[11]).

Figure 6.1. Broadband subscriptions, 2010-22

Note: Fixed broadband subscriptions refer to fixed subscriptions to high-speed access to the public Internet (TCP/IP connection) at downstream speeds equal to, or greater than, 256 kbit/s. This includes cable modem, DSL, fibre-to-the-home/building, other fixed (wired)-broadband subscriptions, satellite broadband and terrestrial fixed wireless broadband. It includes fixed WiMAX and any other fixed wireless technologies. This total is measured irrespective of the method of payment. It excludes subscriptions with access to data communications (including the Internet) via mobile-cellular networks. It includes both residential subscriptions and subscriptions for organisations. Mobile broadband subscriptions (active mobile-broadband subscriptions in ITU Database) refer to the sum of active handset-based and computer-based (USB/dongles) mobile-broadband subscriptions that allow access to the Internet. It covers actual subscribers, not potential subscribers, even though the latter may have broadband-enabled handsets. Subscriptions must include a recurring subscription fee or pass a usage requirement if in the prepayment modality – users must have accessed the Internet in the last three months (ITU, 2020[14]).

Source: ITU (2023[11]), World Telecommunication/ICT Indicators Database 2023 (27th edition/July 2023), www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Pages/publications/wtid.aspx (accessed on 22 August 2023).

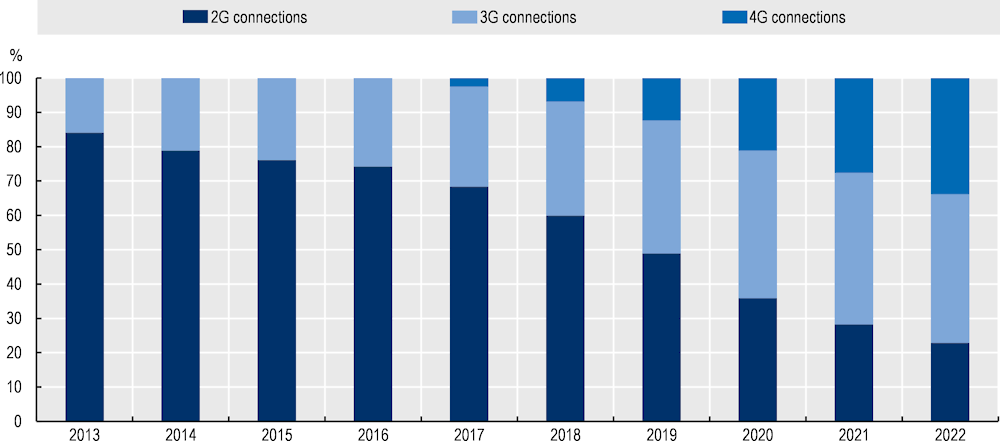

The most common mobile technology in 2022 remains 3G, accounting for 43.3% of mobile connections, followed by 4G with 33.9% and 2G with 22.9% (Figure 6.2) (GSMA Intelligence, 2023[15]). 4G connections have been growing steadily since 2017, while 2G connections have decreased since 2013 (GSMA Intelligence, 2023[15]). Viet Nam differs from its regional neighbours with 3G as the most common mobile technology. 4G is most prevalent in seven of the ten Southeast Asian countries, with 3G the most prevalent in only Brunei Darussalam, Lao People’s Democratic Republic (Lao PDR) and Viet Nam (GSMA Intelligence, 2023[15]). 5G in Viet Nam is at a nascent stage, mainly confined to trials in urban areas, which explains why Figure 6.2 does not show 5G connections. Viet Nam trails other countries in the region that have already deployed 5G, such as Singapore, Thailand and Philippines.

Figure 6.2. Percentage of mobile connections per technology, 2013-22

Source: GSMA Intelligence (2023[15]), Database, www.gsmaintelligence.com/data/ (accessed on 9 November 2023).

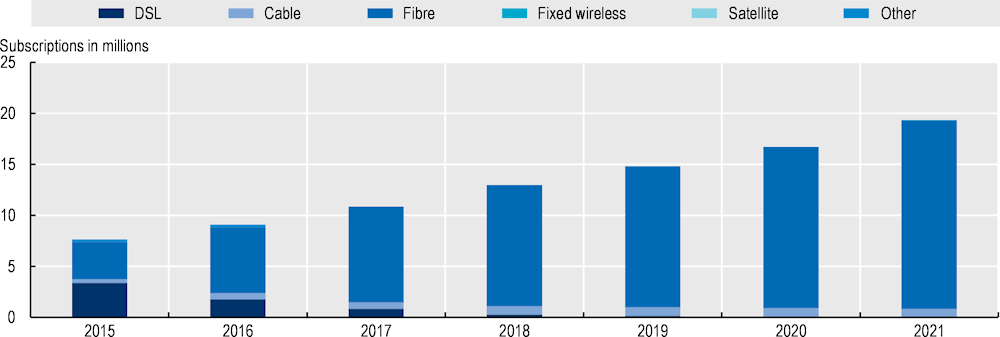

Fixed broadband in Viet Nam is dominated by fibre-to-the-home (FTTH), which is by far the most common technology in the country. Fibre accounted for an impressive 95.5% of fixed broadband subscriptions in 2021 and has grown rapidly in recent years (ITU, 2023[11]). In 2015, fibre accounted for around half of fixed broadband subscriptions (47%), with digital subscriber line (DSL) accounting for roughly the other half (44%) (ITU, 2023[11]). DSL fell sharply to represent only 0.3% of subscriptions in 2021, illustrating how Viet Nam leap-frogged technology by investing in fibre (ITU, 2023[11]). Cable modem technology, although in the minority, grew until 2019 then remained relatively stable, accounting for around 4% of subscriptions in 2019 (ITU, 2023[11]) (Figure 6.3).

Figure 6.3. Fixed broadband subscriptions by technology, 2010-21

Source: ITU (2023[11]), World Telecommunication/ICT Indicators Database 2023 (27th edition/July 2023), www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Pages/publications/wtid.aspx (accessed on 22 August 2023).

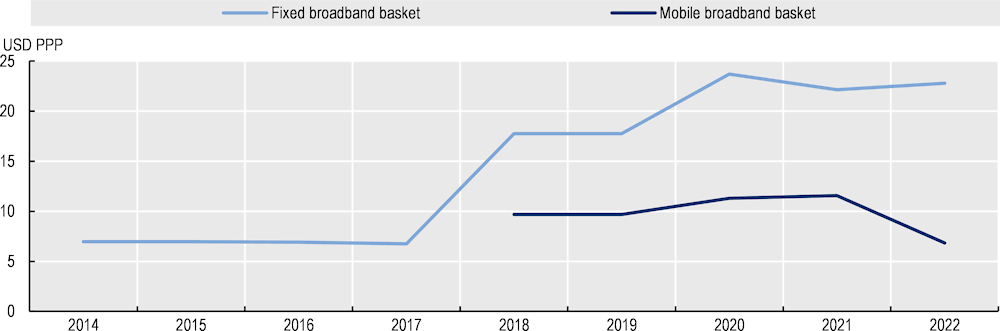

Viet Nam’s prices for entry-level fixed communication service baskets (5 GB) are higher than entry-level mobile service baskets (70 min + 20 SMS + 500 MB), as is the case in other SEA countries (Figure 6.4). From 2014-17, fixed prices were around USD PPP 7.0, before rising to USD PPP 17.8 in 2018 and reaching USD PPP 22.8 in 2022 (ITU, 2023[11]).

Despite this increase in price, fixed prices for Viet Nam were the lowest in the region in 2022, by a wide margin. Cambodia had the second lowest fixed prices USD PPP 41.1 (ITU, 2023[11]). They also appear to be affordable, as in 2022 they represented only 2.6% of gross national income (GNI) per capita (Figure 6.12) (ITU, 2023[11]).

Mobile communication prices for a basic package have also been relatively stable. From 2018 to 2021, they rose from around USD PPP 9.7 to USD PPP 11.6, before dropping to USD PPP 6.8 in 2022 (Figure 6.4) (ITU, 2023[11]). In 2022, Viet Nam had the second lowest mobile prices in the region (USD PPP 6.8), behind Myanmar (USD PPP 5.2) (ITU, 2023[11]). Mobile prices are also affordable. They represented around 2% of GNI per capita from 2018 to 2021, falling to 0.8% of GNI per capita in 2022 (Figure 6.12) (ITU, 2023[11]).

Figure 6.4. Prices for entry-level fixed and mobile communication services, USD PPP, 2014-22

Note: The fixed broadband basket refers to the price of a monthly subscription to an entry-level fixed-broadband plan. For comparability reasons, the fixed-broadband basket is based on a monthly data usage of a minimum of 1 GB from 2014 to 2017, and 5 GB from 2018 to 2022. For plans that limit the monthly amount of data transferred by including data volume caps below 1GB or 5 GB, the cost for the additional bytes is added to the basket. The minimum speed of a broadband connection is 256 kbit/s. The mobile broadband basket is based on a monthly data usage of a minimum of 500 MB of data, 70 voice minutes, and 20 SMSs. For plans that limit the monthly amount of data transferred by including data volume caps below 500 MB (low-consumption), the cost of the additional bytes is added to the basket. The minimum speed of a broadband connection is 256 kbit/s, relying on 3G technologies or above. The data-and-voice price basket is chosen without regard to the plan’s modality, while at the same time, early termination fees for post-paid plans with annual or longer commitment periods are also taken into consideration (ITU, 2020[16]). Mobile basket prices are not available from 2014 to 2017.

Source: ITU (2023[11]), World Telecommunication/ICT Indicators Database 2023 (27th edition/July 2023), www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Pages/publications/wtid.aspx (accessed on 22 August 2023).

6.2.2. Market structure

In the 1990s, Viet Nam began liberalising the communication sector as part of the political and economic reforms towards a “socialist-oriented” market economy (Đổi Mới). The country gradually became more open and integrated internationally, becoming a member of ASEAN in 1995, APEC in 1998 and acceding to the WTO in 2007. Legislative changes also supported this shift. The Ordinance on Post and Telecommunications was passed in 2002 (and later replaced by the 2009 Law on Telecommunications (No. 41/2009/QH12), hereafter “Telecom Law”). This regulated the licensing of communication infrastructure and service providers and allowed the entry of private companies. Subsequently, the Competition Law of 2004 (replaced in 2018) introduced pro-competitive provisions such as ex ante regulation of operators with significant market power.

Notwithstanding these efforts to open the market, state-owned enterprises in the country remain important players in both the fixed and mobile communication markets. Article 17 of the 2009 Telecom Law notes the state holds controlling shares in operators providing communication services, “whose network infrastructure is of particular importance to the operation of the entire national telecommunications infrastructure and directly affects economic development and the society, ensuring national defence and security” [unofficial translation] (Government of Viet Nam, 2009[17]).

State-owned enterprises (SOEs) in the communication sector include the Viet Nam Posts and Telecommunications Group (VNPT), the Military Industry-Telecoms Group (Viettel) and Mobifone Telecommunications Corporation. The Department of Technology and Infrastructure unit of the Commission for the Management of State-owned Capital in Enterprises manages Mobifone and VNPT (CMSC) (CMSC, n.d.[18]). The state owns 100% of shares in both companies (OECD, 2022[19]). Viettel is also 100% state-owned, under the Ministry of Defence (Art. 1) (Government of Viet Nam, 2018[20]).5 The State Capital Investment Corporation (SCIC) owns just over 50% of shares in the FPT Telecom Joint Stock Company, another player in the fixed market (OECD, 2022[19]). The SCIC is a state-owned holding company that acts as a shareholder to invest in enterprises in key sectors that are usually privatised to some degree (OECD, 2022[19]). Of the operators with state ownership, Viettel has a high economic importance to the country. Viettel’s revenues, along with those of Electricity of Viet Nam and Petro Viet Nam, make up half of the total revenues brought in by Viet Nam’s more than 2 000 state-owned (fully or majority-owned) enterprises (OECD, 2022[19]).

In recent years, Viet Nam has taken steps to improve the governance of SOEs. In 2018, for example, it established the CMSC with the objective of “enhancing efficiency, facilitating equitization and separating ownership of the country’s largest 19 SOEs and state corporate groups from the state’s regulatory function” (OECD, 2022[19]). Overall, the total number of SOEs has decreased from 12 000 in the 1990s to around 2 100 in 2022 (OECD, 2022[19]).

The government has also put in place regulation to further streamline the SOE sector. For example, Decision No 22/2021/QD-TTg defines which SOEs should undergo ownership conversion and divestment over 2021-25. It also determines the level of state holdings following the proceedings according to certain classification criteria (Government of Viet Nam, 2021[21]). According to Decision No. 22/2021/QD-TTg, the state will own between 50-65% of SOEs providing communication services with network infrastructure that are critical to national communication infrastructure and that impact socio-economic development and national security (Government of Viet Nam, 2021[21]). In April 2023, the government directed the Ministry of Planning and Investment to assist relevant stakeholders to implement Decision No. 22/2021 (Government of Viet Nam, 2023[22]). However, the specific details regarding divestment plans of communication operators were unclear at the time of writing.

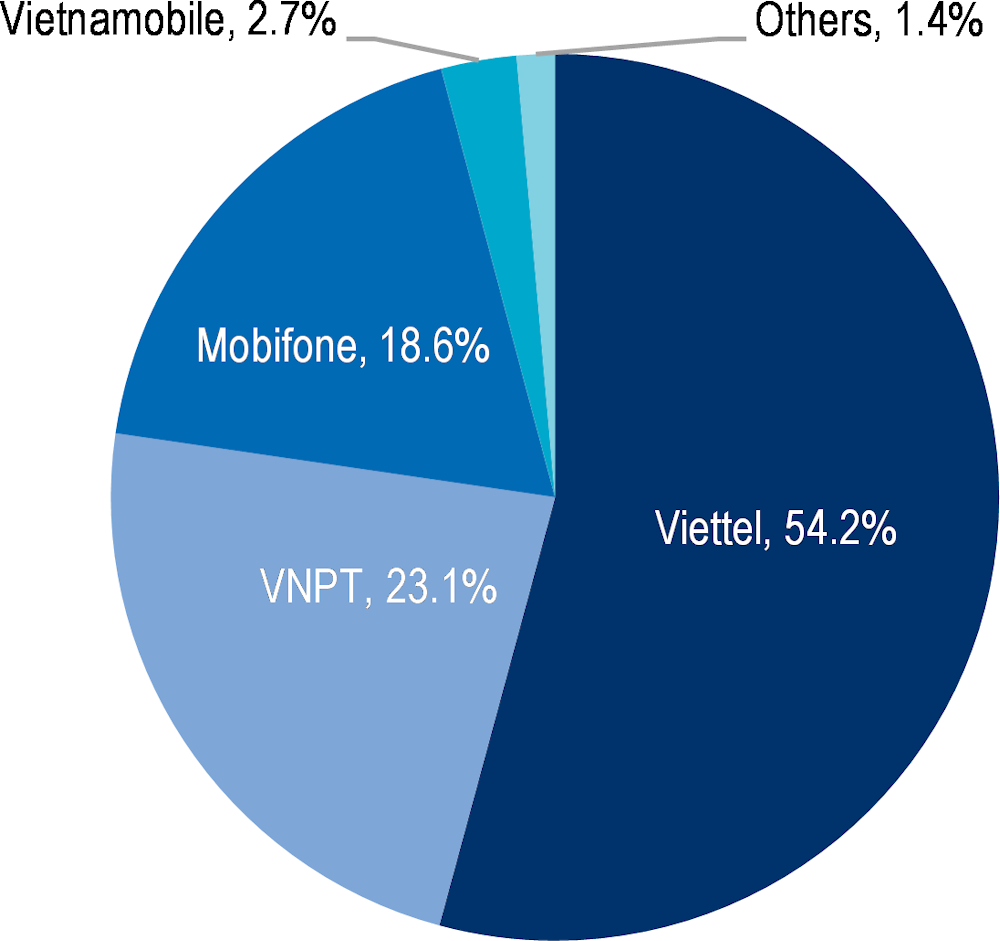

These changes may affect how SOEs operate. This may, in turn, impact Viet Nam’s mobile market, which is characterised by operators with state ownership. Of the four main players in the mobile market, (Viettel, VNPT, Mobifone and Vietnamobile), only Vietnamobile is privately owned.6 As shown in Figure 6.5, Viettel is the leader with over half the market (54.2%) based on mobile broadband subscriptions, followed by VNPT (23.1%), Mobifone (18.6%) and Vietnamobile (2.7%) in 2021. A few other operators collectively hold the remaining 1.4% of the market. Together, state-owned operators account for around 96% of mobile market shares.

Figure 6.5. Mobile market shares based on mobile broadband subscriptions, Q4 2021

Note: Included in the “Others” category are I-Telecom, ASIM, Gtel and Mobicast.

Source: OECD elaboration based on data from Vietnamese authorities.

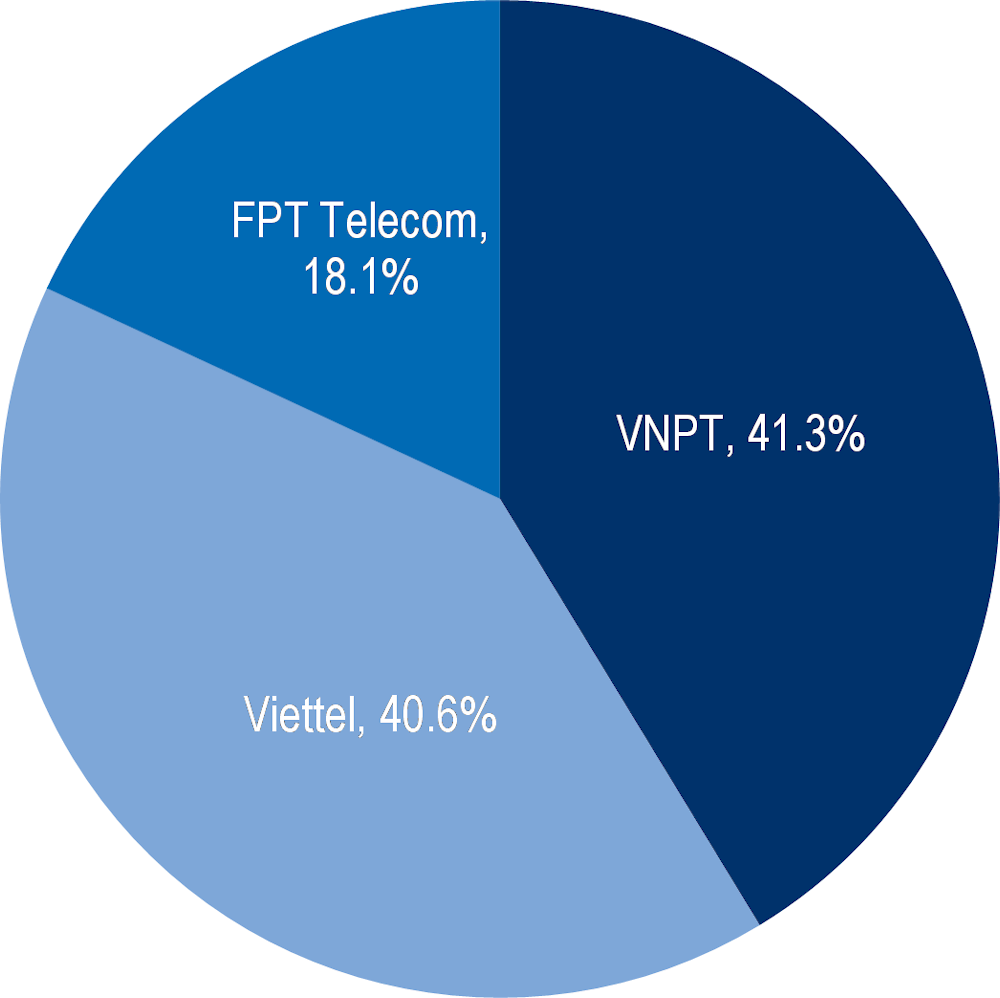

In the fixed market, the state owns shares in all three operators: VNPT, Viettel and FPT Telecom. VNPT leads the market with 41.3%, followed closely by Viettel with 40.6%, based on fixed broadband subscriptions in 2021. FPT Telecom holds the remaining proportion (18.1%) (Figure 6.6).

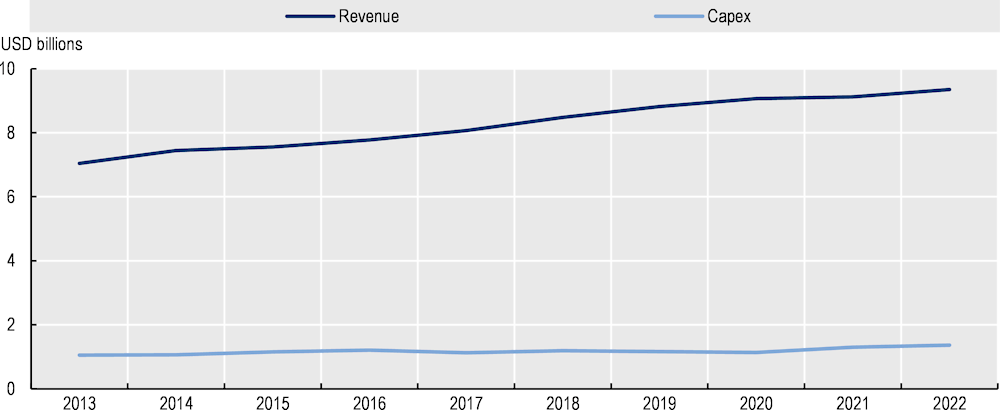

Figure 6.6. Fixed market shares based on fixed broadband subscriptions, Q4 2021

Viet Nam’s communication markets seem to be growing at a healthy pace, considering the growth of broadband subscriptions in the last decade. While data on revenues and investment are unavailable for the fixed market, estimates for the mobile market show steady growth. Total revenues, in nominal terms, of the mobile sector have been steadily increasing from USD 7.04 billion in 2013 to around USD 9.35 billion in 2022, a growth rate of 33% over that period (Figure 6.7) (GSMA Intelligence, 2023[15]). Total investment (Capex) in mobile networks, in nominal terms, kept pace, growing 29% over 2013-22, from USD 1.05 billion to USD 1.36 billion in 2022 (Figure 6.7) (GSMA Intelligence, 2023[15]). Revenue and investment figures for three of the four main mobile operators were unavailable (Viettel, VNPT and Mobifone, which all have state ownership), making comparisons by operator impossible. At the regional level, Viet Nam’s mobile sector compared to SEA peers places Viet Nam third in terms of revenues and fourth in total Capex spent in nominal terms in 2022 (GSMA Intelligence, 2023[15]).

Figure 6.7. Mobile revenues and investment (total Capex), 2013-22

Note: Breakdown by operator is not included due to data availability.

Source: GSMA Intelligence (2023[15]), Database, www.gsmaintelligence.com/data/ (accessed on 9 November 2023).

The remarkable expansion of broadband networks in Viet Nam, coupled with the high quality of fixed networks and relative affordability of broadband services, suggests the Vietnamese market has generally performed well. This has taken place in a relatively concentrated market, where most of the main players have state ownership. However, the large investments needed for deployment of 5G, which is still in its infancy in Viet Nam, and the extension of fibre networks beyond urban areas, could benefit from the entry of private capital to complement public sector investment.

6.3. Communication policy and regulatory framework

6.3.1. Institutional framework

The Ministry of Information and Communications (MIC) is the main body responsible for the communication sector in Viet Nam. As set out in Decree No. 48/2022/ND-CP, its duties include drafting and implementing policies to develop the Vietnamese communication market; issuing communication licences, rules and regulations; and assigning spectrum (Government of Viet Nam, 2022[23]). It also has the remit to regulate the communication sector, including the competition thereof (Government of Viet Nam, 2022[23]). The decree lists several units affiliated with MIC, including the Authority of Telecommunications (VNTA) and the Authority of Radio Frequency (ARFM), whose powers, function and structure are defined by the Minister of Information and Communications (Government of Viet Nam, 2022[23]). VNTA helps MIC monitor and regulate the communication sector, including on competition matters (VNTA, 2020[24]). For its part, ARFM assists MIC in its duties related to radio frequency, including allocation, assignment and use (ARFM, 2022[25]). MIC is also responsible for the broadcasting sector, with support from the Authority of Broadcasting and Electronic Information (Government of Viet Nam, 2022[23]).

The institutional framework of Viet Nam establishes MIC as both the policy-making entity and regulator, as VNTA is an affiliated unit of the ministry. This is problematic given the prevalence of state ownership of communication operators, with the government having full ownership in several fixed and mobile operators. To avoid conflict of interest, the government should not be both a regulator and a regulated entity. This was outlined in Recommendation 2.7 of the OECD Peer Reviews of Competition Law and Policy: Viet Nam (OECD, 2018[26]):

Policy and line agencies (e.g. the Ministries responsible for making policy in telecommunications, energy and transport or the agencies responsible for enforcing laws in those areas) should perform their functions without favour or discrimination between businesses that are state owned or privately owned.

Operators with state ownership, especially those with 100% state ownership (Mobifone, VNPT, Viettel), seem to largely enact policies set by the government. The government also appoints key leadership positions, for instance at VNPT, meaning there is governmental influence in these companies.

In addition, the lack of an independent regulator and the prevalence of operators with state ownership in both markets introduce a risk that public and private entities may receive different regulatory treatment. The existence of only one main privately-owned player in the mobile market (which even then only has around 3% market share) may create the perception of discrepancy in the treatment of private companies, although there is no formal evidence of this. As one concrete example of how this may play out, the state both assigns licences for the use of spectrum – a critical but scarce resource – and receives them through its SOEs. This can result in a potential conflict of interest where other private operators are vying for the right to use spectrum.

In addition, the 2021 OECD Broadband Recommendation calls for regulatory decisions in the communication sector to be made, “in an independent, impartial, objective (evidence- and knowledge-based), proportionate, and consistent manner” (OECD, 2021[1]). Similarly, the 2012 Recommendation of the OECD Council on the Regulatory Policy and Governance advocates for regulators to make objective, impartial and consistent decisions, avoiding conflicts of interest (OECD, 2012[27]). The Annex to the Recommendation suggests considering independent regulators where regulatory decisions can have a significant economic impact on the regulated parties (OECD, 2012[27]). This clearly applies to the communication sector.

Separating regulatory functions from policy-making functions helps promote independent, impartial and objective regulatory decisions, based on evidence and insulated from political influence. Indeed, 84% of communication regulators in the OECD member countries are independent, as established by legislation (OECD, 2022[28]).

Recommendation

1. Establish an independent regulatory body with remit over the communication sector. As MIC acts as both the policy-making entity and regulator through its affiliated unit (VNTA), there is no independent regulator in the country. An independent regulator, equipped with the tools to monitor and enforce regulation over the communication sector, is considered good practice across the OECD. Especially given the prevalence of state ownership of important players in the communication sector, Viet Nam should establish an independent regulatory body with remit over the communication sector to strengthen its institutional framework, in line with OECD Recommendations (OECD, 2021[1]; OECD, 2012[27]).

6.3.2. Regulatory framework

The 2009 Law on Telecommunications (No. 41/2009/QH12) (Telecom Law) and the Law on Radio Frequencies (No. 42/2009/QH12) provide the backbone of Viet Nam’s regulatory framework governing the communication sector. As the broad legislation over the communication sector in Viet Nam, the Telecom Law covers several areas. These include MIC’s responsibilities and powers, licensing, interconnection and infrastructure sharing, technical standards and network deployment planning (Government of Viet Nam, 2009[17]). Secondary legislation (“decrees”) define further provisions to implement the Telecom Law, such as Decree 25/2011/ND-CP (Government of Viet Nam, 2011[29]) and the amending Decree 81/2016/ND-CP (Government of Viet Nam, 2016[30]). At the time of writing, revisions to the Telecom Law are currently being discussed (MIC, 2023[31]). Some of the proposed amendments currently under discussion pertain to competition management.

According to the licensing framework outlined in the Telecom Law, there are two types of administrative licences: one for the commercial provision of communication services in Viet Nam (“commercial licence”) and one for communication operations (“operations licence”) [unofficial translation] (Government of Viet Nam, 2009[17]). The “commercial” licence is given to operators, either with or without their own network infrastructure. Meanwhile, the “operations” licence covers firms wishing to either install submarine cables, operate a private network or test communication networks and services (Government of Viet Nam, 2009[17]). Operators applying for a commercial licence to establish a fixed or mobile terrestrial communication network, or a satellite fixed or mobile communication network, must meet capital and investment thresholds, among other licence conditions (Government of Viet Nam, 2011[29]).

Fees apply for the right to both operate a public telecommunication network and provide telecommunication services to the public, according to Art. 41 of the Telecom Law and Art. 30 of the implementing Decree 25/2011/ND-CP. The right to operate a public network requires a fixed annual fee, set on a case-by-case basis depending on the type, scope and scale of the network (Government of Viet Nam, 2011[29]). The annual fee for the right to provide communication services is set as 0.5% of annual revenues from the services included in the licence (Government of Viet Nam, 2018[32]). However, this annual fee cannot be lower than a fixed rate that is set for each type of service. Operators must also contribute to the Viet Nam Public-Utility Telecommunication Service Fund, depending on the service (Government of Viet Nam, 2011[29]). For communication services, operators must contribute 1.5% of revenues accrued from providing these services to the Fund, according to the Prime Minister’s Decision 2269/2021/QD-TTg (Government of Viet Nam, 2021[33]).

The Law on Radio Frequencies is another key text defining the communication framework in the country. It empowers MIC to manage spectrum resources in the country, including to allocate frequency bands nationally, assign spectrum, define technical standards for radio equipment and restrict harmful interference (Government of Viet Nam, 2009[34]).

6.3.3. Broadband strategies and plans

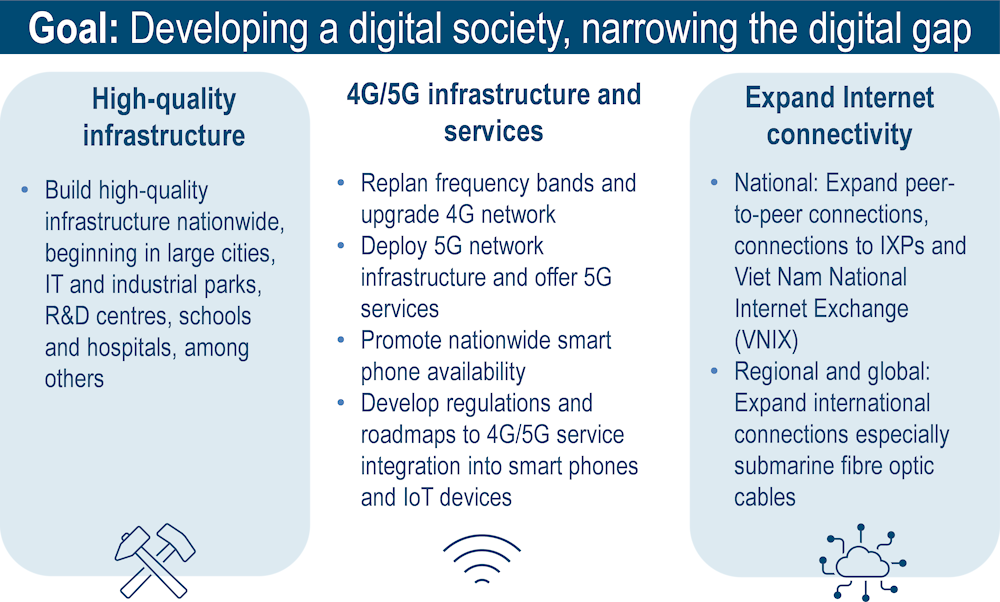

Developing the communication industry is included in the government’s broad Five-Year (2021-2025) and Ten-Year (2021-2030) Plans, underscoring its importance to foster digital transformation (National Assembly, Socialist Republic of Viet Nam, 2021[7]; Congress of Viet Nam, 2021[8]). Furthermore, the “National digital transformation programme to 2025, orientation to 2030”, approved in June 2020, includes goals under three main policy objectives: i) developing digital government and improving operational efficiency; ii) developing the digital economy and improving global competitiveness; and iii) developing a digital society and closing digital divides (Government of Viet Nam, 2020[35]). This programme builds on past strategies, such as the strategy articulated in the Prime Minister’s 2010 Decision 1755/2010/QD-TTg, which included goals related to broadband communication infrastructure (Government of Viet Nam, 2010[36]).

Under the last objective, to develop a digital society and close digital divides, the programme has set specific targets for communication infrastructure. By 2025, 80% of households and 100% of municipalities should be connected to the Internet via fibre, and 4G or 5G services and smartphones should be universally available. By 2030, fibre and 5G should be universally available. Compared to countries in the region, but also OECD countries, these targets are ambitious. The programme also includes specific actions to achieve these targets, such as building high quality infrastructure, improving 4G/5G networks and services, and expanding Internet connectivity, as outlined in Figure 6.8.

Figure 6.8. Actions to achieve communication infrastructure targets under Viet Nam’s National Digital Transformation Programme to 2025, orientation to 2030

Note: The graphic focuses on those actions related to communication infrastructure and connectivity goals and does not represent all actions and targets included under the programme.

Source: OECD elaboration based on Viet Nam (2020[35]), Quyết định số 749/QĐ-TTg của Thủ tướng Chính phủ: Phê duyệt “Chương trình Chuyển đổi số quốc gia đến năm 2025, định hướng đến năm 2030“ [Decision No. 749/QD-TTg of the Prime Minister: Approving the “National Digital Transformation Programme to 2025, with orientation to 2030”], https://chinhphu.vn/default.aspx?pageid=27160&docid=200163.

6.4. Competition, investment and innovation in broadband markets

6.4.1. Competition

Considering the level of competition in Viet Nam’s communication markets, as noted above, both the fixed and mobile market are characterised by a few strong players, most of which have state ownership. In the mobile market, Viettel leads with 54.2% of total mobile broadband subscriptions, followed by VNPT (23.1%), Mobifone (18.6%) and Vietnamobile (2.7%) in 2021. The remaining 1.4% is shared among a few small operators (Figure 6.5). This results in a Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) rating of 3 825, calculated based on these market shares. As Viettel holds over half of the market and VNPT, the next closest competitor, has only half of that (23.1%), competitive pressure from other operators may be limited. This poses a risk that Viettel may leverage its position, which Vietnamese authorities have acknowledged. In 2015, Circular 15/2015/TT-BTTTT revised the 2012 designation of providers of mobile communication services (voice, messaging and Internet access) with a “dominant” market position from Viettel, Mobifone and VNPT to only Viettel (MIC, 2015[37]; Government of Viet Nam, 2012[38]). This designation remains today. If the revisions to the Telecom Law on competition are passed according to expectations, this designation will be subject to a more comprehensive and systematic re-evaluation according to national authorities. Despite this relative concentration, mobile broadband prices are affordable, around 0.8% of GNI per capita in 2022 (Figure 6.12) (ITU, 2023[11]).

In the fixed market, three players split the total number of fixed broadband subscriptions: VNPT, Viettel and FPT Telecom. VNPT and Viettel both hold around 40% of the market each, with FPT Telecom holding the remainder (18.1%) in 2021 (Figure 6.6). The HHI for the fixed market, considering these market shares, is 3 683. This could be classified as a highly concentrated market according to certain classifications, such as those put forward by US Department of Justice (2010[39]). In 2012, Circular 18/2012/TT-BTTTT defined all three players as having a dominant position in the fixed broadband Internet access market, a classification still in effect (Government of Viet Nam, 2012[38]). Naming all three operators in the fixed market as having a “dominant” position is counter intuitive. As in the mobile market, the prevailing designation in the fixed market will undergo reassessment following the revised Telecom Law’s expected enactment, according to national authorities.

Despite the market’s concentration around three main players, prices for fixed broadband seem to be affordable. In 2022, entry-level fixed broadband prices represented only 2.6% of gross national income (GNI) per capita (Figure 6.12) (ITU, 2023[11]). This has likely driven the strong fixed broadband penetration in the country, as discussed below.

When considering overall competition in the communication sector, the question of state ownership is important to note. While enterprises with state ownership dominate the market, there is not just one state-owned operator. Rather, there are three in each market (fixed and mobile), whose very presence applies a degree of competitive pressure compared to a monopoly market structure. Therefore, the Vietnamese framework seems to encourage competition among the SOEs. The competing operators with state ownership is an important distinction in the Vietnamese market, setting it apart from traditional thinking surrounding state-run communication markets.

However, Viet Nam does not seem to be particularly conducive to privately owned operators. This is likely due in part to Article 17 in the Telecom Law regarding the state holding controlling shares in operators of particular importance (Government of Viet Nam, 2009[17]). A related question is how Article 17 would be applied if a private operator becomes an important player in the market and whether there is a risk of discriminatory treatment to avoid such a scenario, although there is no evidence of this to date. Some degree of preference for state-owned operators may occur in practice and even this perception may deter the entry of new private operators into the market. This is supported by findings in the 2022 OECD Review of the Corporate Governance of State-Owned Enterprises in Viet Nam (OECD, 2022[19]):

On the issue of competitive neutrality, no formal statutory discrimination between SOEs and private firms is detected. However, the proximity of SOEs to policy makers, continued conflation of the exercise of ownership rights, the government’s explicit use of SOEs as a main vehicle for the implementation of the State’s industrial or sectoral policies, policy formulation and regulatory responsibilities within the same government ministries/agencies have led to a perception of discrimination and discrepancy while distorting the playing field.

Thus, introducing an independent communication regulator, continuing planned reforms of the SOE sector and potentially revising Article 17, may make Viet Nam’s communication markets more conducive to private entities. This, in turn, may also stimulate further competition in the market and spur private investment in communication networks.

Underpinning this landscape, the 2018 Competition Law (No. 23/2018/QH14) establishes the general competition regulatory framework across industries in Viet Nam. Namely, it legally establishes companies’ right to freely compete (Government of Viet Nam, 2018[40]). Importantly, Article 8 explicitly prohibits state agencies from hindering market competition, including to discriminate between enterprises, giving the legal basis for competitive neutrality (Government of Viet Nam, 2018[40]). This is important as the government – driven by national interests – owns shares in all three main fixed operators and three of the four main mobile operators.

Enterprises may be considered to have dominant market position if they have significant market power (SMP), as defined in Art. 26 of the Competition Law, or have a market share of 30% or more (Government of Viet Nam, 2018[40]). An entity may be determined to have SMP based on several characteristics, such as the market landscape and respective market share, barriers to entry, and the financial position of the firm and its competitors, among others (Government of Viet Nam, 2018[40]).

Under this broad framework, the Telecom Law prohibits communication companies from conducting anti-competitive behaviour, as defined under the Competition Law. The Telecom Law further bans operators with either a dominant market position or those with essential facilities from conducting specific anti-competitive acts. Such acts include withholding technical information on essential facilities or other necessary information for a competitor to offer communication services (Government of Viet Nam, 2009[17]). The law further defines MIC as the lead agency for competition matters in the sector. MIC co‑ordinates with the Ministry of Industry and Trade (MoIT) to uphold the competition provisions of the Telecom Law. Under MIC, VNTA is the “specialised management agency in telecommunications” with the remit to manage and regulate competition related to establishment of communication networks and provision of services (Government of Viet Nam, 2011[29]).

In case of proceedings such as mergers, acquisitions or joint ventures that would result in a combined market share of between 30-50%, the firms must notify VNTA and the competition authorities prior to undertaking the venture (Government of Viet Nam, 2011[29]). Where the combined market share would be greater than 50%, the Minister of Industry and Trade must approve the proceeding, after receiving the approval from the Minister of Information and Communications (Government of Viet Nam, 2011[29]).

The Competition Law establishes MoIT as the lead government agency on competition matters. It also creates the “Viet Nam Competition Commission” (VCC) [English translation], which conducts competition assessments (Government of Viet Nam, 2018[40]). In February 2023, five years after the Competition Law’s passing, Decree No. 03/2023/ND-CP established the powers, structure and mandate of the VCC under MoIT (Government of Viet Nam, 2023[41]). The decree allows VCC to properly assume its functions and issue decisions. Accordingly, in March 2023, the prime minister appointed the chair and seven members to the VCC (VCC, 2023[42]). As one of its duties, VCC monitors violations of the competition framework, including by “state agencies” [unofficial translation of Art. 2(4)] (Government of Viet Nam, 2023[41]). VCC replaces the Viet Nam Competition and Consumer Authority.

Regulatory oversight is key to upholding the competition framework outlined above. The Telecom Law defines MIC, through VNTA, as the responsible body to manage competition in the communication sector. VCC has a broader remit to manage competition in the country and enforces violations of the competition framework by other government agencies, which is of particular importance to the communication sector. According to national authorities, VNTA manages competition through a “pre-inspection” approach in the communication sector (defined under the Telecom Law), while VCC manages competition through a “post-inspection” approach in the communication sector as well as all other sectors (defined under the Competition Law). As VNTA and VCC carry out their respective mandates in the communication sector, Viet Nam should monitor and clarify in case any uncertainties arise.

Further, the Telecom Law notes that MIC and MoIT should co‑ordinate on competition matters in the communication sector (Art 19(7)) (Government of Viet Nam, 2009[17]). This co‑ordination would likely occur through their respective bodies (e.g. VNTA and VCC). However, the nature of this co-ordination is not defined in the Law and may require further clarification. Ensuring appropriate co-ordination mechanisms on cross-cutting issues like competition to promote regulatory coherence is a key tenet of the 2012 OECD Recommendation on Regulatory Policy and Governance (OECD, 2012[27]). Enacting this regulatory framework depends on the ability of VNTA to co‑ordinate with VCC and enforce it effectively to promote fair competition in the market.

Recommendations

2. Conduct regular competition assessments of relevant markets. The last classifications of dominance in the mobile and fixed markets were conducted in 2015 and 2012, respectively. Viet Nam could consider reassessing these markets, and other relevant markets as needed, taking into account the planned amendments to the Telecom Law that are currently being discussed. Based on these assessments, regulatory measures could be enacted as necessary (e.g. asymmetric regulation on dominant operators) to increase the level of competition.

3. Implement reforms of state ownership in the communication sector and consider facilitating ownership by private entities. Viet Nam’s plans regarding SOE ownership conversion and divestment over 2021-25 are welcome and should be implemented in a timely manner. In particular, Viet Nam could consider further reform of state ownership in the communication sector. Further, Viet Nam could consider amendments to Article 17 of the Telecom Law regarding state ownership of communication operators of particular importance, to open the communication sector to wider participation by private entities. These actions could help make Viet Nam’s communication sector more conducive to private actors, lowering barriers to entry and participation to stimulate further competition in the market.

4. Clarify co-ordination mechanisms between VNTA and VCC, where needed. The Telecom Law notes that MIC and MoIT should co‑ordinate on competition matters in the communication sector, which would occur through their respective bodies (e.g. VNTA and VCC). However, the co-ordination mechanism does not seem to be explicitly defined and may require further clarification in case issues arise as VNTA and VCC carry out their respective mandates governing competition in the communication sector.

6.4.2. Investment

Viet Nam’s policies influence how much operators invest to expand and upgrade their networks. This influence may be even more pronounced as the state holds shares in several large players and may shape operators’ investment strategies. As a key policy objective in Art. 4(1), the Telecom Law promotes investment to deploy communication infrastructure to support socio-economic development (Government of Viet Nam, 2009[17]). As part of the criteria to obtain a licence to establish a network in the country, prospective operators must meet certain capital thresholds and agree to investment commitments depending on the type of network (Government of Viet Nam, 2011[29]). For example, operators of a nationwide fixed terrestrial communication network using frequency bands and numbering must have VND 300 billion (USD 12.7 million) as capital (Government of Viet Nam, 2011[29]). They must also commit to investing at least VND 1 trillion (USD 42.3 million) in the first 3 years of the licence and at least VND 3 trillion (USD 126.9 million) over 15 years (Government of Viet Nam, 2011[29]).7 For a mobile terrestrial communication network using spectrum bands, operators must have a legal capital of VND 500 billion (USD 21.1 million). They must also commit to invest at least VND 2.5 trillion (USD 105.7 million) for the first 3 years and at least VND 7.5 trillion (USD 317.2 million) over 15 years (Government of Viet Nam, 2011[29]).8 These requirements seek to verify that a prospective operator has the financial means to deploy networks, given the capital-intensive nature of operating and maintaining communication networks.

Mobile operators seem to be investing above the legal thresholds set in their licensing conditions. For example, Vietnamese operators had a Capex of USD 1.36 billion in 2022 (nominal terms) (Figure 6.7), spending more in a year (albeit together) than the required investment commitment per operator over 15 years (USD 317.2 million) (GSMA Intelligence, 2023[15]). With respect to regional peers, Thailand and Indonesia lead in terms of overall Capex in 2022, followed by the Philippines and Viet Nam in fourth place (GSMA Intelligence, 2023[15]).

The Telecom Law further allows the shared use of communication infrastructure under Article 45 (Government of Viet Nam, 2009[17]). Network operators can form contractual sharing agreements directly. The VNTA will only intervene in certain instances. These include cases where parties cannot reach an agreement to share essential facilities, where the shared use of passive infrastructure is required to meet planning rules, or where the shared infrastructure will be used to provide “public-utility” (e.g. universal service) communication services (Government of Viet Nam, 2009[17]).

From informational interviews, Vietnamese mobile operators seem primarily to share passive infrastructure (e.g. towers, base stations). However, MIC has recently encouraged greater sharing, including of active infrastructure. While operators note certain technical challenges to sharing of active elements, they have taken some early action. In 2021, the three largest mobile operators, Viettel, VNPT and Mobifone, signed a 5G network-sharing agreement during their 5G trials. This included the sharing of active elements, such as multi-network radio access (MIC, 2021[43]; MIC, 2021[44]). MIC announced plans to issue regulations on sharing 5G infrastructure to further support these sharing activities (MIC, 2021[43]). Promoting network sharing can help foster investment and promote quicker network deployment. At the same time, attention should be paid to ensure that active infrastructure sharing does not lead to less competition in the market.

Viet Nam’s regulatory framework related to foreign direct investment (FDI) is governed by the Telecom Law, the Law on Investment and by the international or regional treaties to which Viet Nam has adhered. The Telecom Law requires foreign investors to register their business and obtain an “investment certificate”, in addition to applying for the relevant telecommunication licences (Government of Viet Nam, 2009[17]). Both direct and indirect investment in communication services is allowed (Government of Viet Nam, 2011[29]).

Certain restrictions apply to investment in communication services. Article 17 of the Telecom Law asserts that the state holds a controlling number of shares in communication network service providers of particular importance. This effectively limits the market’s openness to private entities, foreign or Vietnamese. In addition, Viet Nam’s commitments to the WTO Agreement for Trade in Services specifies that foreign capital (investment) must not exceed 65% for non-facilities-based service providers and 49% for facilities-based service providers (WTO, 2007[45]). Joint ventures with communication service suppliers duly licensed in Viet Nam are allowed for both types (non-facilities-based and facilities-based operators) (WTO, 2007[45]). Therefore, foreign operators that either own their own networks (facilities-based) or only rent capacity (non-facilities based) are not allowed to operate in the country without a Vietnamese partner.

In addition to its WTO commitments, Viet Nam also adheres to regional trade agreements, which may allow less restrictive thresholds for signing countries. For example, the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), to which Viet Nam is a signatory, allows slightly lower restrictions. Under the CPTPP, foreign investment for non-facilities-based services is permitted via purchase of shares in a Vietnamese company or through a joint venture up to 65% (up to 70% for virtual private networks) (Government of Viet Nam, n.d.[46]).

The limitation in the CPTPP on non-facilities-based services ends for signatories five years after the agreement entered into force, presumably 5 years after Viet Nam signed the agreement in 2019 (Government of Viet Nam, n.d.[46]; WTO, 2023[47]).9 Thus, no foreign investment or joint venture requirement should remain for CPTPP parties for non-facilities-based services after 2024.

However, restrictions remain for CPTPP signatories for facilities-based services, even after five years. Foreign investment for facilities-based services must occur through a joint venture or via purchase of shares in a Vietnamese firm. It is capped at 49% for basic services, or 51% for value-added services (VAS) (Government of Viet Nam, n.d.[46]). This 51% limit for VAS facilities-based services will increase to 65% in 2024 for CPTPP signatories (Government of Viet Nam, n.d.[46]). Foreign service suppliers under the CPTPP may fully own submarine cable transmission capacity that lands in Viet Nam and are permitted to sell capacity to any licensed operator in Viet Nam (Government of Viet Nam, n.d.[46]).

Viet Nam’s legal framework restricts FDI and limits the entry of private players, both foreign and Vietnamese, also evident given the dominance and prevalence of operators with state ownership. Nevertheless, the information and communication sector has more broadly attracted FDI, close to USD 655 million in 2022 (Ministry of Planning and Investment, 2022[48]). Considering inward FDI stock across all economic sectors, Viet Nam ranks fourth among ASEAN countries in 2021, behind Singapore, Thailand and Indonesia (UNCTAD, 2022[49]).10

Similar ownership restrictions exist in other SEA countries. Thailand, for example, has similar caps although several operators in both the fixed and mobile markets have foreign investors. Viet Nam’s case differs from Thailand due to the prevalence of SOEs and given legal restrictions. These facts may hinder the ability of foreign firms to participate in the market more than the FDI restrictions themselves. However, the removal of FDI restrictions would help further open the market to foreign players and provide additional investment incentives. Mexico, for example, eliminated restrictions on FDI in telecommunication and satellite communication services, allowing the entry of foreign companies. Subsequently, companies such as AT&T and Eutelsat, have made important investments in the country (OECD, 2017[50]).

Annual fees for communication operators may also affect investment. Operators must pay a licence fee as well as an operating fee, according to the Telecom Law (Art. 35) (Government of Viet Nam, 2009[34]). In addition, they must contribute to the Viet Nam Public-Utility Telecommunication Service Fund. In addition to these, operators must pay an annual fee for spectrum usage, as well as a one-time fee to obtain the spectrum rights (e.g. auction price, in cases where spectrum rights are auctioned).

Fees to obtain a telecommunication licence and to contribute to a universal service fund are common across OECD countries. However, annual spectrum usage fees, on top of one-time fees to obtain spectrum rights increases financial burden and may risk hindering investment. While some OECD countries have an annual spectrum fee, these are most often set to recover costs (OECD, 2022[51]).

The level of total fees levied on network operators should be carefully assessed to determine their impact on operators’ long-term financial health and their ability to invest in network deployment. However, during informational calls with Vietnamese operators for this report, the level of fees did not seem to pose a problem or impact their propensity to invest. In addition, current levels of investment seem to be sufficient, with Viet Nam ranking fourth in the region in terms of overall Capex in 2022 (nominal terms).

Recommendation

5. Consider lowering restrictions on private entities, both foreign and Vietnamese, to enter the market and invest to deploy networks, and eliminate FDI restrictions. As Viet Nam’s framework limits FDI and the entry and participation of private firms, both foreign and national, in the market, authorities could consider lowering these barriers. To that end, they could remove FDI restrictions and encourage private sector capital for investment in communication networks. Such actions can support the deployment of new 5G networks and extension of FTTH networks beyond urban areas, which will require substantial investments.

6.4.3. Innovation

To establish an enabling environment to support innovation, the Telecom Law established a one-year trial licence for entities wishing to test their networks and services (Government of Viet Nam, 2009[17]). To obtain the trial licence, applicants must test services not already included in their licence or that use resources already allocated. In addition, tests must adhere to relevant regulations and standards (Government of Viet Nam, 2009[17]).

This trial licence, which has relatively low requirements to obtain it, has helped support development of new technologies and services, such as 5G. In 2019, MIC issued trial licences to Viettel, VNPT and Mobifone to trial 5G services (MIC, 2019[52]). In 2023, MIC reported the operators had trialed 5G in 40 cities or provinces (MIC, 2023[53]). Despite these trials, 5G network deployment remains at a limited scale in the country. To foster 5G, MIC has called on operators to develop 5G (MIC, 2021[44]). However, the government’s slow release of additional mobile spectrum seems to have delayed 5G network deployment. Thus, the expedient assignment of additional spectrum is needed to ensure operators can deliver on 5G plans, as noted in the section on “spectrum management” below.

The government has also established strategies to target certain technologies for further development. Similarly, in December 2020, the prime minister issued Decision No. 38/2020/QD-TTg, setting forth a list of advanced technologies and high-tech products that are prioritised for investment and development (Government of Viet Nam, 2020[54]). The list includes several technologies related to communication, such as next-generation network technology, virtualisation and computing technology, and technology for integration and optimisation of telecommunication systems (Government of Viet Nam, 2020[54]). The Decision does not specify how these technologies will be prioritised, allowing relevant ministries to implement them through their own policies in support of these goals.

6.5. Broadband deployment and digital divides

6.5.1. Broadband deployment

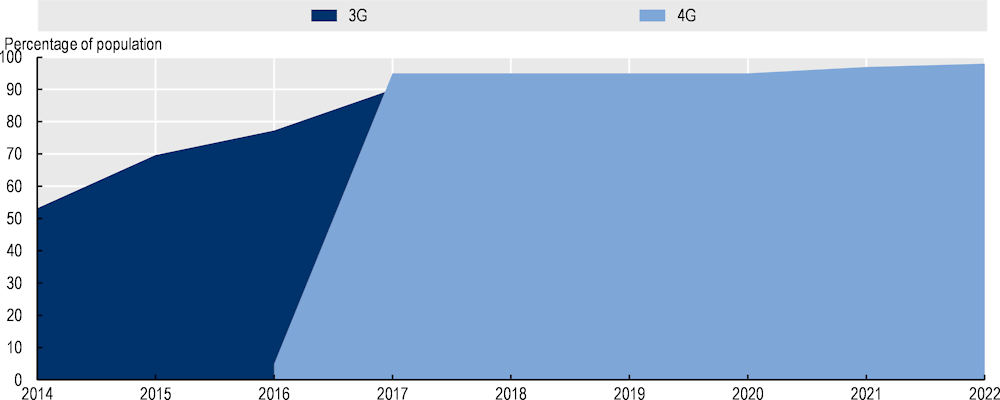

Viet Nam has made significant progress in broadband development, especially in the second half of the last decade. Mobile broadband (3G, 4G) coverage reaches almost the entire population (98% by 2022) (GSMA Intelligence, 2023[15]). 3G networks have been progressively deployed over the last decade, reaching 95% of the population by 2020. They continued at a slower pace to reach the current level of 98% (GSMA Intelligence, 2023[15]). 4G networks, on the other hand, have had a much more rapid rollout since 2016, with 95% population coverage already in 2017 (GSMA Intelligence, 2023[15]) (Figure 6.9). The rollout of 5G, however, is still in a trial phase, with connectivity only available in urban areas (December 2022) (Opensignal, 2023[55]).11 Viet Nam lags its regional peers in 5G deployment, with Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand already having commercial 5G deployments (GSMA, 2022[56]).

Figure 6.9. Mobile broadband coverage, 2014-22

Source: GSMA Intelligence, (2023[15]), Database, www.gsmaintelligence.com/data/ (accessed on 9 November 2023).

Although no coverage data are available, Viet Nam has relatively high fixed penetration, second in the region with 21.7 subscriptions per 100 inhabitants. This indicates a considerable percentage of the population has access to such networks (Figure 6.1). Moreover, data on fixed subscriptions by technology show a leap towards FTTH/B in recent years (Figure 6.3).

Several factors favour achievement of a high population coverage (households passed) for a given wireline network rollout. First, most people live in highly concentrated in urban and suburban areas (81% of the population) (2015) (European Commission, Joint Research Centre, 2015[3]). Second, people are typically settled along rivers, canals and roads. The opposite is true for low density areas, where 19% of Viet Nam's population live (2015) (European Commission, Joint Research Centre, 2015[3]), making investment in these areas much less profitable and resulting in a coverage gap.

In terms of backbone networks, there are three major fibre networks according to the ITU Broadband Map. Two are operated by the dominant fixed and mobile network operators, VNPT and Viettel respectively, and the Greater Mekong Subregional Information Superhighway operates the third (ITU, 2023[57]). They have a total route length of 264 389 route kilometres (2020) (ITU, 2023[57]).12 The network has a relatively high coverage area, with 44% of the population within 10 km of a transmission network node, above the SEA average (43%); 90% are within 25 km (2020) (ITU, 2023[57]). These networks are complemented by Viet Nam's own satellite, VINASAT, which provides connectivity to mountainous areas, islands and border areas (as well as maritime communications).

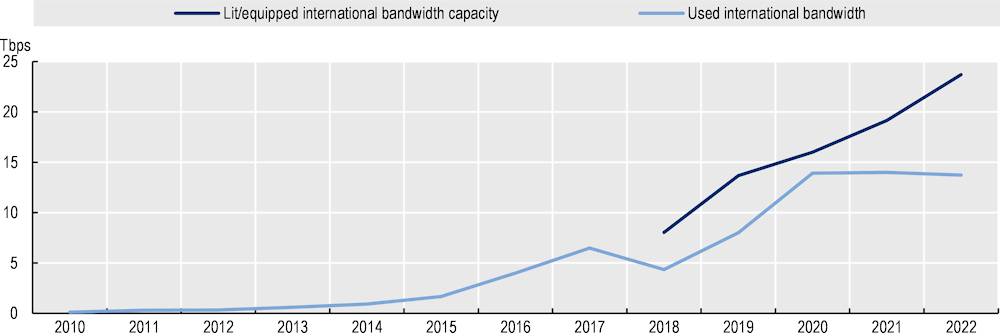

In terms of international connectivity, Viet Nam has an equipped capacity of 23.7 terabits per second (Tbps) (2022) (ITU, 2023[11]). This represents 6% of the region’s capacity, fourth behind the 54% provided by Singapore, the 23% by Malaysia and the 12% by Indonesia (2022) (ITU, 2023[11]). The data show a significant increase in Viet Nam’s used international bandwidth in recent years (Figure 6.10). This coincides with the rollout of 4G networks and the surge in mobile broadband subscriptions, reaching 14 Tbps in 2022, 58% of installed capacity (ITU, 2023[11]).

Figure 6.10. International bandwidth, 2010-22

Note: Lit/equipped international bandwidth capacity refers to the total lit capacity of international links, namely fibre-optic cables, international radio links and satellite uplinks to orbital satellites in the end of the reference year (expressed in Mbit/s). If the traffic is asymmetric (i.e., different incoming and outgoing traffic), then the highest value out of the two should be provided. Average usage of all international links, including optical fibre cables, radio links and traffic processed by satellite ground stations and teleports to orbital satellites (expressed in Mbit/s). The average is calculated over the twelve-month period of the reference year. If the traffic is asymmetric (i.e. different incoming and outgoing traffic), then the highest value out of the two should be provided. All international links used by all types of operators, namely fixed, mobile and satellite operators should be taken into account. The combined average usage of all international links can be reported as the sum of the average usage of each link (ITU, 2020[14]).

Source: ITU (2023[11]), World Telecommunication/ICT Indicators Database 2023 (27th edition/July 2023), www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Pages/publications/wtid.aspx (accessed on 22 August 2023).

Viet Nam’s international connectivity is provided by terrestrial and submarine cables and its satellite system, VINASAT. The country has seven submarine cable landing stations, a relatively low number for the region despite its long coastline (e.g. Thailand has 11 landing stations). The seven stations connect Viet Nam to some of the longest cable systems, including the SeaMeWe-3 cable, the Asia Africa Europe-1 (AAE-1) cable (bypassing Singapore) and the Asia-America Gateway (AAG) cable system. It is also part of two systems connecting countries within the Eastern Asia region: the Southeast Asia-Japan Cable 2 (SJC2) and the Tata TGN-Intra Asia (TGN-IA) cable (TeleGeography, 2023[58]). This submarine cable system connects Viet Nam to several regions of the world, including in Africa, Europe, Oceania and other Asian regions (Table 6.3).

At the intra-SEA level, Viet Nam is not connected to any regional cable systems, unlike other countries in the region (e.g. Malaysia-Cambodia-Thailand cable, Thailand-Indonesia-Singapore cable). However, the long-distance cable systems provide Viet Nam with connectivity to all SEA countries (except the landlocked Lao PDR). Six of the seven cables connect Viet Nam to Singapore and Thailand, four to Malaysia and the Philippines, two to Myanmar and Brunei Darussalam, and one each to Cambodia and Indonesia (Table 6.2).

Table 6.2. Viet Nam’s connections with other SEA countries via submarine cables

|

Cable system |

Brunei Darussalam |

Cambodia |

Indonesia |

Lao People's Democratic Republic |

Malaysia |

Myanmar |

Philippines |

Singapore |

Thailand |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Asia Africa Europe-1 (AAE-1) |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|||||

|

Asia Direct Cable (ADC) |

x |

x |

x |

||||||

|

Asia Pacific Gateway (APG) |

x |

x |

x |

||||||

|

Asia-America Gateway (AAG) Cable System |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

||||

|

SeaMeWe-3 |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

||

|

Southeast Asia-Japan Cable 2 (SJC2) |

x |

x |

|||||||

|

Tata TGN-Intra Asia (TGN-IA) |

x |

x |

Source: OECD elaboration from TeleGeography (2023[58]), Submarine Cable Map, www.submarinecablemap.com/ (accessed on 22 February 2023).

Table 6.3. Viet Nam's connections with other regions via submarine cables

|

Cable system |

Northern Africa |

Sub-Saharan Africa |

North America |

Eastern Asia |

Southern Asia |

Western Asia |

Northern Europe |

Southern Europe |

Western Europe |

Australia and New Zealand |

Micronesia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Asia Africa Europe-1 (AAE-1) |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|||||

|

Asia Direct Cable (ADC) |

x |

||||||||||

|

Asia Pacific Gateway (APG) |

x |

||||||||||

|

Asia-America Gateway (AAG) Cable System |

x |

x |

x |

||||||||

|

SeaMeWe-3 |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

||

|

Southeast Asia-Japan Cable 2 (SJC2) |

x |

||||||||||

|

Tata TGN-Intra Asia (TGN-IA) |

x |

Source: OECD elaboration from TeleGeography (2023[58]), Submarine Cable Map, www.submarinecablemap.com/ (accessed on 22 February 2023).

An international terrestrial cable network called the Greater Mekong Subregional Information Superhighway (GMS IS) connects Cambodia, Lao PDR, Myanmar, Thailand, Viet Nam and Yunnan Province in the People’s Republic of China (hereafter “China”) (ADB, 2005[59]). The GMS IS in Viet Nam is deployed along the coastal route between Ha Noi and Ho Chi Minh City, with direct links to Cambodia, Lao PDR and China (ITU, 2023[57]). Finally, Viet Nam also has its own satellite system, VINASAT-1 and VINASAT-2, operated by VPNT. The satellites provide connectivity to remote areas, border areas and islands, and improve international connectivity. They are also used for national security and defence. MIC recently announced a plan to replace VINASAT-1 and VINASAT-2 in 2023 (Khang, 2022[60]).

The Viet Nam National Internet Exchange (VNIX), created in 2003, is managed and operated by the Viet Nam Internet Centre (VNNIC), a unit under MIC. VNIX operates under the principle of non-profit neutrality for peering services between agencies, organisations and enterprises. However, in parallel, VNIX operates as a commercial platform, allowing connected organisations to buy or sell services to each other, including Internet access and cloud services (VNNIC, 2023[61]). VNIX has five nodes distributed throughout the country, two in Ha Noi (north), two in Ho Chi Minh City (south) and one in Đà Nẵng (central). The distributed nodes of the VNIX have performed well in handling this growing Internet traffic. Quality indicators, such as fixed broadband latency and jitter, are among the lowest in the region, along with Singapore and Brunei Darussalam.

Table 6.4. Internet exchange points, 2023

|

Name |

City |

|---|---|

|

Viet Nam National Internet Exchange |

Ho Chi Minh City |

|

Viet Nam National Internet Exchange |

Hanoi |

|

Viet Nam National Internet Exchange |

Da Nang city |

Source: PCH (2023[62]), Internet Exchange Directory, www.pch.net/ixp/dir (accessed 5 December 2023).

6.5.2. Digital divides

Despite the major development of broadband in Viet Nam over the last decade, there are marked differences in Internet usage depending on several factors. Although the Internet usage rate in Viet Nam is relatively high (79% of the population) (2022) (ITU, 2023[11]), there is a pronounced geographical gap between urban and rural areas. As of 2020, the gap reached 18 percentage points (64% of individuals in rural areas use the Internet vs. 82% in urban areas) (ITU, 2023[11]). There is also a significant gender gap of six percentage points in favour of men (2022) (ITU, 2023[11]). There are no publicly available data to determine whether the country has an age-related divide.

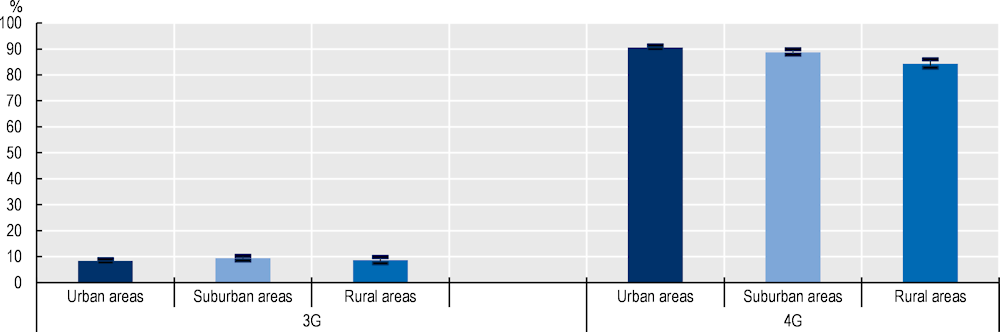

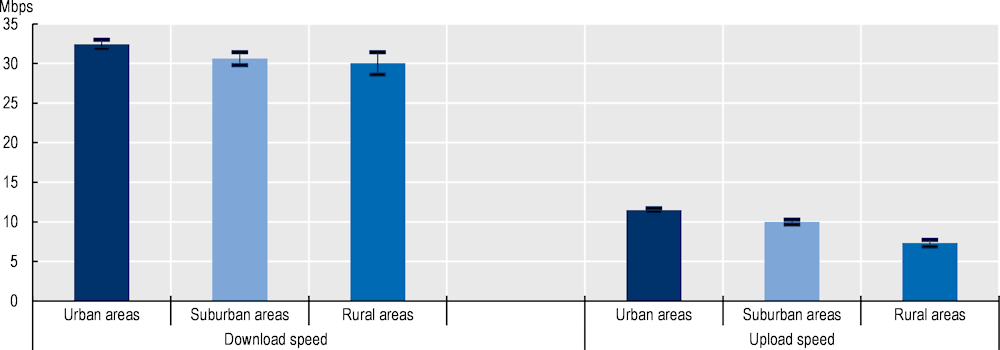

Several causes on both the supply and demand sides may explain these gaps. Looking in more detail at supply-side reasons, mobile network availability, understood as the proportion of time users have a 3G and 4G connection (Opensignal, 2023[63]), shows some differences between urban, suburban and rural areas (Figure 6.11). According to Opensignal, 4G network availability is 6.3 percentage points lower in rural areas than in urban areas, although still relatively high at 84.3% of the time (December 2022 - February 2023) (Figure 6.11) (Opensignal, 2023[55]). Despite the high level of mobile network availability, the lower quality of mobile broadband services in rural areas may contribute to the geographical divide (Figure 6.13).

With regard to fixed broadband, data disaggregated by degree of urbanisation are not available. However, interviews with local stakeholders indicate that coverage seems to be concentrated in densely populated areas. This may limit connectivity for some users who need the performance generally offered by these networks (e.g. higher upload speed and reliability), such as business users (small and medium-sized enterprises) and public administrations.

Figure 6.11. Network availability, percentage of time (3G, 4G), December 2022 – February 2023

Notes:

1. Data was collected by Opensignal from its users over 90 days (1 December 2022–28 February 2023).

2. 3G availability shows the proportion of time that all Opensignal users had a 3G connection. 4G availability shows the proportion of time Opensignal users with a 4G device and a 4G subscription – but have never connected to 5G – had a 4G connection. 5G availability shows the proportion of time Opensignal users with a 5G device and a 5G subscription had an active 5G connection (Opensignal, 2023[63]).

3. Confidence intervals (as represented by error bars) provide information on the margins of error or the precision in the metric calculations. They represent the range in which the true value is likely to be, considering the entire range of data measurements.

4. The results for urban areas, suburban areas and rural areas have been obtained by averaging, in each of these categories, the results of the users’ tests in geographical locations classified as “urban centres” for urban areas, “dense urban areas”, “semi-dense urban areas” and “suburban areas” for suburban areas, and “low density rural areas”, “rural areas” and “very low density rural areas” for rural areas. This territory classification has been taken from the Global Human Settlement Layer Dataset (European Commission, Joint Research Centre, 2022[64]). This applies the definitions of degree or urbanisation established in the methodology developed by the European Commission, Food and Agriculture Organization, UN-Habitat, International Labour Organization, OECD and World Bank (European Commission, Eurostat, 2021[65]).

Source: © Opensignal Limited - All rights reserved (2023[55]), http://www.opensignal.com.

Informational interviews identified two main barriers to deploying networks in rural areas to address the coverage and speed gaps. First, the high cost of network deployment and low demand undermined the business case. Second, there were long delays and administrative burdens in obtaining construction permits, especially at the local level. This situation seems to indicate the limited practical effectiveness of government measures to facilitate permits for network construction (see section on policy and regulation).

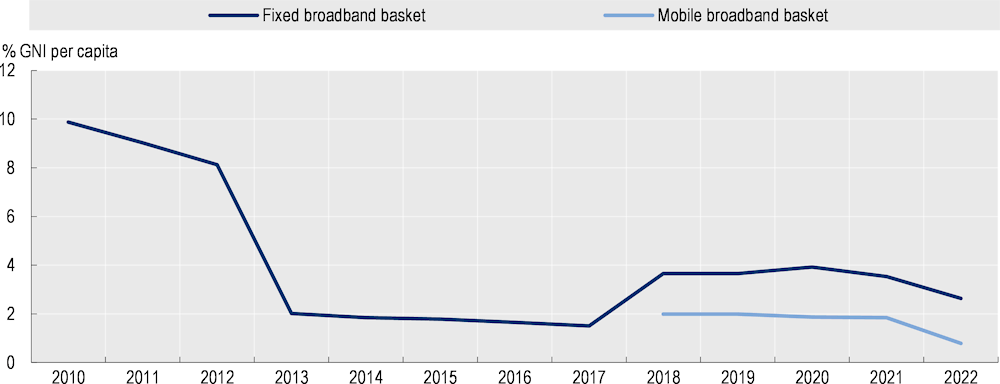

Broadband prices in Viet Nam are relatively affordable in terms of purchasing power. They are close to the target of less than 2% of GNI per capita for entry-level broadband services set by the Broadband Commission in support of the SDGs (Broadband Commission for Sustainable Development, 2022[66]).13 Fixed broadband prices fell dramatically from 2012 to 2013, from 8.1% of GNI per capita to 2.0%. In the following years, they stayed below 4%, falling to 2.6% in 2022 (Figure 6.12) (ITU, 2023[11]). Mobile broadband prices are also relatively affordable. They remained at around 2% of GNI per capita between 2018 and 2021, falling to 0.8% of GNI per capita in 2022 (ITU, 2023[11]) (Figure 6.12). These data suggest the price of broadband connectivity does not appear to be a determining factor in the digital divide between different socio-economic groups.

However, affordability for devices can also influence adoption of communication services. According to Tarifica, mobile device prices are relatively high relative to income levels in Viet Nam, with the benchmark price of entry-level internet-enabled handset reaching 19.49% of average monthly income (2022) (Tarifica, 2023[67]).14 This value is above the price in countries with similar GDP, such as Indonesia ( 7.74 %), and well above countries such as Singapore (0.39%). (Alliance for Affordable Internet, 2021[82])

Figure 6.12. Prices for fixed and mobile broadband services (percentage GNI per capita), 2010-22

Note: The fixed broadband basket refers to the price of a monthly subscription to an entry-level fixed-broadband plan. For comparability reasons, the fixed-broadband basket is based on a monthly data usage of a minimum of 1 GB from 2010 to 2017, and 5 GB from 2018 to 2022. For plans that limit the monthly amount of data transferred by including data volume caps below 1GB or 5 GB, the cost for the additional bytes is added to the basket. The minimum speed of a broadband connection is 256 kbit/s. The mobile broadband basket is based on a monthly data usage of a minimum of 500 MB of data, 70 voice minutes, and 20 SMSs. For plans that limit the monthly amount of data transferred by including data volume caps below 500 MB (low-consumption), the cost of the additional bytes is added to the basket. The minimum speed of a broadband connection is 256 kbit/s, relying on 3G technologies or above. The data-and-voice price basket is chosen without regard to the plan’s modality, while at the same time, early termination fees for post-paid plans with annual or longer commitment periods are also taken into consideration (ITU, 2020[16]). Mobile basket prices are not available from 2010 to 2017.

Source: ITU (2023[11]), World Telecommunication/ICT Indicators Database 2023 (27th edition/July 2023), www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Pages/publications/wtid.aspx (accessed on 22 August 2023).

On the demand side, data reveal that a lack of digital skills can be a barrier to Internet usage. Only 26% of the population reported having the most widespread skill, “using copy and paste tools within a document” (2021) (ITU, 2023[11]). This was one of the lowest percentages of the countries examined in this report, along with Thailand (23% of the population for the same skill) (2020) (ITU, 2023[11]). The remaining digital skills covered by the ITU survey, such as “sending e-mails with attached files” or “creating electronic presentations with presentation software” have lower percentages (ITU, 2023[11]). Data on digital literacy by age or location are not available, preventing conclusions on their influence on the age and geographical divide. The national authorities consulted also point to the lack of digital skills as a key constraint to broadband adoption.

6.5.3. Policies and regulation