This chapter discusses the regulatory framework and ASF’s attributions to audit public works and infrastructure. It analyses how such regulatory framework influences the orientation and objectives of ASF’s audits and suggests reforms to incorporate a wider infrastructure governance approach, beyond mere compliance.

Facilitating the Implementation of the Mexican Supreme Audit Institution’s Mandate

2. Regulatory framework and ASF powers to audit infrastructure in Mexico

Abstract

ASF’s legal framework and mandate

Even though the legal framework grants ASF wide powers to audit infrastructure, such audits tend to be compliance oriented and do not pay enough attention to value-for-money and other wider governance issues

ASF’s attributions are mainly established in Mexico’s Constitution and in the Auditing and Accountability Act (Ley de Fiscalización y Rendición de Cuentas de la Federación, LFRCF). Title III, Chapter II, Section V of the Political Constitution of the United Mexican States (Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos, CPEUM) regulates ASF and the audit of the public accounts. It establishes that ASF is granted technical and management autonomy to carry out its functions and decide about its internal organisation, functioning, and resolutions. One of its main responsibilities is ex post auditing of revenues, expenditures and debts; the management, custody, and allocation of funds and resources of the branches of government and federal public entities, as well as the performance relative to the objectives of federal programmes.

In line with the Constitutional mandate, the LFRCF establishes in Article 14 the objectives of the audit of the public accounts, which refers, among others, to the audits of public works, including:

I. Assessing the results of the financial management:

a) Reviewing that expenditure was carried out following the authorised concepts and budget lines, including, among others, the procurement of services, public works, and goods, leasing, subsidies, contributions, donations, transfers, contributions to funds, and other financial instruments.

b) Compliance with the applicable legal framework on government accounting; procurement of services, public works, goods, leasing, maintenance, use, destination, and sale of movable goods and buildings, warehouses, and other assets; material resources; and other rules applicable to the expenditure of public resources.

Likewise, Article 17, bullet VIII, of the LFRCF, refers to the ASF powers in the field:

VIII. Verifying public works, goods, and services procured by the audited entities to determine if the resources invested and spent were exercised according to the applicable rules.

The Internal ASF Bylaws (Reglamento Interior de la Auditoría Superior de la Federación) complement the regulatory framework by establishing that the General Directorate for Auditing Federal Investments (Dirección General de Auditoría de Inversiones Físicas Federales, DGAIFF) is in charge of auditing to verify that the planning, programming, budgeting, award, delivery, progress, and destiny of the public works and the procurement relative to federal investments were aligned with the applicable rules; that the expenditure is adequately demonstrated and justified, and that fiscal requirements were fulfilled. Likewise, DGAIFF verifies if procured public works, goods, and services were applied efficiently and according to the rules to fulfil the objectives and goals of the corresponding programmes.

The regulatory framework grants on ASF wide powers to audit the public works procured and executed with federal funding by the entities of the federal, state, and municipal public administrations, including planning, programming, budgeting, procurement, delivery, and termination. The sectors in which infrastructure is developed include, among others, energy, communications and transport, education, health, social development, environment, tourism, water, and government.

While the legal framework grants on ASF the powers to audit public works, such audits take place ex post and there is no explicit reference to the wider governance of infrastructure as a key enabler to projects’ success. Even though there is an increasing trend, it is not a common practice for ASF to audit and review infrastructure projects at the stages of project preparation or investment appraisal (stages 1 and 2 in the public investment cycle), as it usually concentrates on the tendering, execution, and contract management stages, and to some extent in the evaluation (stages 4, 5, and 6 of the cycle). Indeed, the orientation of the legal mandate influences the scope and focus of ASF’s audits, hindering a wider approach that could steer ASF strategies and policies. This is so despite the fact that ASF recognises that public works in Mexico should be assessed beyond their economic dimensions and consider:

if the execution of such public works renders benefits to society

if they contribute to economic, social, and urban development

if they contribute to fulfil the objectives and goals of the National Development Plan (Plan Nacional de Desarrollo, PND), i.e. to what extent they facilitate national development and strong, sustained, and sustainable growth.

Box 2.1. Results of the audits of the monument Trail of Light (Estela de Luz)

Trail of Light is a monument built in the iconic Reforma Avenue of Mexico City to commemorate the 200th anniversary of Mexico’s independence and the 100th anniversary of the revolution. ASF carried out 10 audits of the project during 2009-11 to ensure the construction was performed efficiently, effectively, and economically, according to the applicable regulations. As a result of the audits, ASF issued 106 observations, leading to 142 actions, 36 recommendations, 1 request for fiscal justification (promoción del ejercicio de la facultad de comprobación fiscal), 11 observation files, 86 files of sanctionable administrative responsibility (responsabilidad administrativa sancionatoria), and 2 fact reports (denuncias de hechos). Out of these audits, two were public works audits corresponding to the public accounts 2010 and 2011.

The main issues identified in the audits were the following:

Procurement of services with companies whose objectives were not aligned with the service requested or without the capacity to provide them, leading to outsourcing and the selection of procedures different from a public tender.

Unduly approval of exceptions to public tenders to carry out restricted invitations to procure works.

Modification and inclusion of additional works concepts in the catalogue presented by the project architect without technical justification and authorisation.

Modifying agreements leading to a significant cost overrun in the construction (from MXN 394.4 million to 1 146 million).

Excess and unjustified payments for MXN 248.9 million.

Delays in the presentation of technical documents for the execution of the works, leading to unnecessary deferrals and postponements.

Procurement of technical studies whose specifications did not met the requirements for the adequate delivery of the works.

Formal authorisation to kick off the construction based on inadequate technical studies, which eventually led to cost and time overruns in the construction.

Source: (ASF, 2012[1]).

Hence, a first recommendation consists on reviewing the ASF regulatory framework to explicitly mandate it to audit and review the governance of infrastructure projects from a comprehensive point of view and a whole investment cycle approach. In fact, as it will be discussed later, early engagement is key to improve the chances of success of infrastructure projects. ASF could raise the issue to the Legislative Commission for ASF Oversight (Comisión de Vigilancia de la ASF de la Cámara de Diputados) so that legislators recognise the potential for a reform that would empower ASF to advance audits on the wider governance of infrastructure projects. If such a reform were approved, it would then be up to ASF to adapt its strategies and policies to facilitate its implementation.

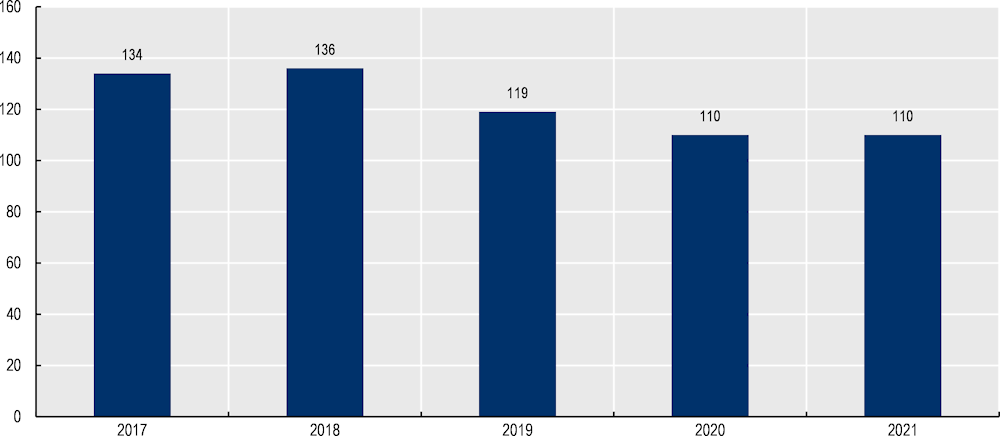

Another feature of ASF audits is that they are compliance oriented, i.e. they aim to ensure compliance with the legal framework relative to public works, not necessarily to create value-for-money. Articles 14, bullet I, index b, and 17, bullet VIII of the LFRCF, as well as the Internal Bylaws, are very explicit on ensuring that public works are undertaken according to the legal framework and applicable regulations. Indeed, over the last years, the infrastructure audits have concentrated on financial compliance (see Figure 2.1).1 This does not necessarily entail that value-for-money considerations will be a concern for auditors or even for the public officials with management responsibilities in public works and infrastructure projects. In fact, OECD has found that, in some cases, procurement officials in Mexico tend to worry more about compliance with the regulatory framework than with creating value-for-money (see Box 2.2). ASF audits should be more comprehensive to reverse this trend.

Figure 2.1. Evolution of ASF’s audits on physical investments compliance

Note: The number of audits in 2020 and 2021 were limited due to the restrictions stemming from the COVID-19 crisis and audit staff limitations.

Source: Information provided by ASF.

Box 2.2. Compliance approach of public procurement officials in the State of Nuevo León, Mexico

There is a difficult balance to strike between flexibility and control. At the national and state level in Mexico, there is a faulty assumption that more regulation will lead to less corruption. In fact, the strong compliance approach has limited the ability of procurement officials to seek value-for-money.

Indeed, the 2018 OECD review Public Procurement in Nuevo León, Mexico: Promoting Efficiency through Centralisation and Professionalisation found that, when undertaking procurement, public officials in Nuevo León privilege a compliance approach, rather than value-for-money. There are several reasons for this. First, procurement operations in Nuevo León are overregulated because of an incorrect assumption that more regulation leads to fewer opportunities for corruption. Second, audit findings have sparked high levels of public mistrust of government officials. This has in turn driven these officials to protect themselves by strictly observing the letter of the law – even if it hinders the potential for reaping value-for-money for the public sphere.

This close attention to legal compliance may be counterproductive, as officials sometimes end processes out of fear of not being able to meet a high level of legal compliance. They fear reprisal, or simply want to “be on the safe side”, i.e. they refrain from doing anything that is associated with the slightest risk of violating a law.

Source: (OECD, 2018[2]).

In line with the first previous recommendation, ASF could take the initiative to promote legislative reforms to prominently incorporate criteria for its audits beyond legal compliance, such as value-for-money and wider governance considerations for infrastructure projects. This would not only help to ensure projects’ success and contributions to national economic and social objectives, but it would also prevent a concentration on legal requirements even when the projects do not significantly contribute to meet such objectives. These recommendations are consistent with ASF’s plans to suggest reforms to widen and strengthen its powers relative to auditing public works and would empower it to build capacities and design tailored strategies. The UK National Audit Office (NAO), for example, has changed its approach to auditing infrastructure projects and programmes to focus on the underlying issues leading to project failure, while still routinely looking at the biggest and riskiest projects (Table 2.1).

Table 2.1. NAO’s audit approach to infrastructure projects and programmes

|

Traditional approach |

Revised approach |

|---|---|

|

|

Source: Presentation by NAO officials during the OECD webinar “Auditing the governance of infrastructure”, held on 2-4 June 2021.

References

[1] ASF (2012), Informe sobre la Fiscalización Superior del Monumento Estela de Luz 2009-2011, https://www.asf.gob.mx/uploads/56_Informes_especiales_de_auditoria/Estela_Luz_Nv.pdf.

[2] OECD (2018), Public Procurement in Nuevo León, Mexico: Promoting Efficiency through Centralisation and Professionalisation, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264288225-en.

Note

← 1. Audits carried out by the DGAIFF on infrastructure works are called “audits on physical investments compliance” (auditorías de cumplimiento a inversiones físicas).