This chapter takes stock of ASF’s initiatives to collect data to identify shortcomings in infrastructure management and delivery and how these efforts can feed into a wider governance approach. It also suggests specific criteria and methodologies to strengthen audit programming and selection, which in turn could influence the assessment of the impact of ASF’s work.

Facilitating the Implementation of the Mexican Supreme Audit Institution’s Mandate

4. Risk analysis to inform audit programming and selection in Mexico

Abstract

Infrastructure audits programming and selection

ASF could apply criteria relative to impact on well-being to select infrastructure audits

ASF’s risk analysis to inform public works audits selection and programming is based on the following criteria:

Public accounts: Ministries and entities (dependencias y entidades) which got the highest budgets for public works (Chapter 6000).

Strategic works: Ministries and entities with major projects in terms of social and economic impact.

Statistics: Ministries and entities with previous observations or repetition of observations in audits.

ASF may also include in the PAAF those public works capturing significant media attention or where congressional and citizen requests exist.

As acknowledged in the 2021 OECD Progress Report, ASF has established the practice of measuring the results of its work by estimating the Return of Investment (ROI). In fact, the report documents a decreasing ROI for the period 2016-18. However, as suggested, ASF could also consider its qualitative contributions to good governance and well-being. This applies perfectly to infrastructure audits, meaning that ASF could select audits based on their contribution to the well-being of citizens and incorporate such contributions to the estimation of its benefits. For example, in the current context of COVID-19 and in order to improve the number of hospital beds per inhabitant, ASF could prioritise works aimed to develop infrastructure in the health sector.1Likewise, ASF could consider works necessary to avoid catastrophic losses as a result of natural disasters. Mexico is highly exposed to natural disasters (i.e. earthquakes, floods, hurricanes, etc.) and infrastructure (i.e. dams, ports, etc.) can strengthen its resilience and protect citizens in high-risk areas.

One way to assess the contributions to well-being in the cases mentioned above would be to apply counterfactual analysis. Counterfactual analysis enables evaluators to attribute cause and effect between interventions and outcomes. The counterfactual measures consist on what would have happened to beneficiaries in the absence of an intervention, and impact is estimated by comparing counterfactual outcomes to those observed under the intervention. ASF could employ counterfactual analysis to complement other sources to measure its impact, such as performance audits and ROI.

Box 4.1. Counterfactual impact evaluation

Questions related to the sign and magnitude of programme and infrastructure impacts arise frequently in evaluation. For example, does investment in new public infrastructure increase housing values? The evaluation problem has to do with the “attribution” of the change observed to the intervention that has been implemented. Is the change due to the policy or would it have occurred anyway?

The challenge for quantifying the effect is finding a credible approximation to what would have occurred in the absence of the intervention, and to compare it with what actually happened. The difference is the estimated effect, or impact, of the intervention on the particular outcome of interest (in this case, housing values).

There are two basic ways to approximate the counterfactual: i) using the outcome observed for non-beneficiaries; or ii) using the outcome observed for beneficiaries before they are exposed to the intervention. However, caution is due in interpreting these differences as the “effect” of the intervention. Likewise, comprehensive evaluation should rely on different methods that complement each other.

Source: (European Commission, n.d.[1]).

ASF has systematically collected data to identify the most common failures in infrastructure delivery, which should be helpful to focus resources on preventive interventions in the different stages of the infrastructure cycle

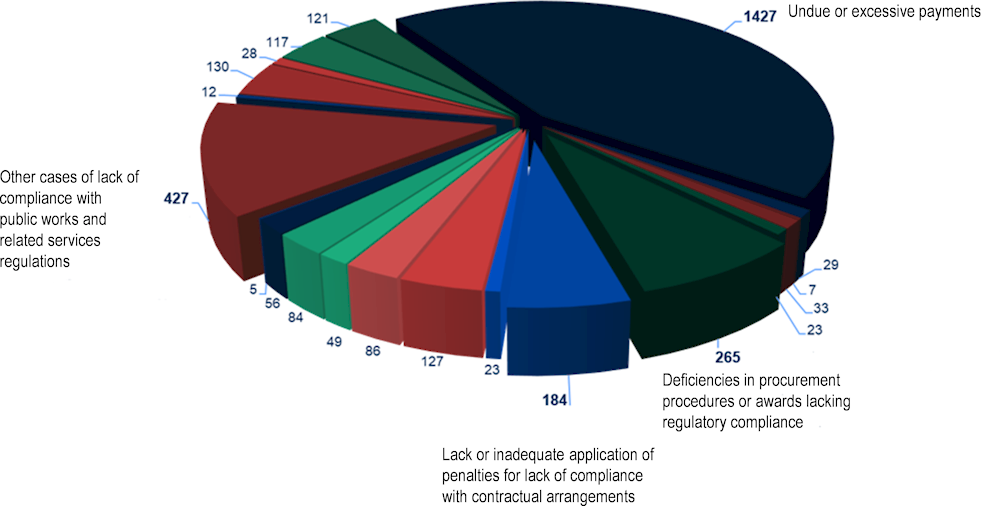

In addition to the findings and recommendations of the ASF report General issues relative to public works and services related 2011-16 (see section 3.1), ASF has continued strategically tracking recurrent observations related to public works. For example, out of a sample of 3 233 observations stemming from the audits to the public accounts 2015-17, there are four main categories concentrating 71.23% of the observations (2 303 observations), which are i) undue or excessive payments; ii) deficiencies in procurement procedures or awards lacking regulatory compliance; iii) lack or inadequate application of penalties for lack of compliance with contractual arrangements; and iv) other cases of lack of compliance with public works and related services regulations (see Figure 4.1 and Table 4.1).

Figure 4.1. Top recurrent observations relative to public works stemming from the audit of public accounts 2015-17

Source: Information provided by ASF.

Table 4.1. Recurrent observations relative to public works stemming from the audit of public accounts 2015-17

|

Observation |

Public account |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

|

|

Lack or expiration of manuals, internal rules, or legal guidelines |

7 |

1 |

4 |

|

Lack or inadequate formalisation of contracts, agreements, or requests |

51 |

49 |

30 |

|

Inadequate setting, control, or archive of files |

6 |

15 |

7 |

|

Lack of authorisation or justification for expenses |

51 |

32 |

34 |

|

Lack of documents justifying expenses or documents not fulfilling fiscal requirements |

63 |

41 |

17 |

|

Undue or excessive payments |

580 |

510 |

337 |

|

Lack of or late reimbursement of resources or interests to the Federation Treasury (TESOFE) or state treasuries |

13 |

11 |

5 |

|

Lack of retention or payments of taxes, fees, or any other fiscal obligation |

5 |

0 |

2 |

|

Lack of execution of advanced payments, credit titles, guarantees, insurances, or debts |

15 |

7 |

11 |

|

Lack of, insufficiency, late delivery, or inadequate formalisation of advanced payment guarantees, compliance. hidden vices, etc. |

10 |

7 |

6 |

|

Deficiencies in procurement procedures or awards lacking regulatory compliance |

160 |

89 |

16 |

|

Lack or inadequate application of penalties for lack of compliance with contractual arrangements |

90 |

54 |

40 |

|

Unneeded purchasing of goods and services |

10 |

10 |

3 |

|

Inadequate planning, authorisation, or programming of the works |

50 |

50 |

27 |

|

Deficiencies in the management or control of the works schedule and inadequate supervision |

35 |

24 |

27 |

|

Lack of or deficiencies in the termination of works contracts or in the acceptance/approval of works |

20 |

19 |

10 |

|

Poor quality works |

20 |

41 |

23 |

|

Lack of or deficiencies in licenses, land use permits, feasibility studies, construction permits, environmental impact assessments, and structural estimations |

31 |

16 |

9 |

|

Lack of operation of finished works |

2 |

3 |

0 |

|

Other cases of lack of compliance with public works and related services regulations |

186 |

160 |

81 |

|

TOTAL |

1 405 |

1 139 |

689 |

Source: Information provided by ASF.

The strategic collection and analysis of data has been useful to identify critical risks to guide audit selection. For example, the analysis of the observations in the public accounts audits of 2015-17 indicate that many of the weaknesses in infrastructure delivery are found in the contract management phase. This fact would lead to pay special attention during audits to the work of supervisors. Findings like this stress once again the need to take a wider governance approach to infrastructure audit, encompassing all the stages of the public investment cycle, in this case the execution stage. It also highlights the importance of reforms to carry out real-time audits to continually review the execution of the infrastructure.

Likewise, there are plenty of observations focusing on early stages (i.e. planning), which calls for early ASF interventions to ensure that infrastructure projects are set for success. For example, if ASF could perform real-time audits, it could make sure projects meet all regulatory requirements (i.e. licences and permits), feasibility studies, and even sustainability considerations, therefore addressing different principles of the OECD Recommendation on the Governance of Infrastructure. Issues such as compliance with regulatory requirements (i.e. feasibility and environmental studies, licenses, etc.) could also be the subject of periodic performance assessments, linking project success with the findings of such studies. This would also provide valuable insights as to the extent to which such requirements are fulfilling the policy objectives they pursue.

Finally, there are also many observations dealing with the tender stage (i.e. assessment of bids, award of contracts, etc.). The OECD experience in working with public procurement (including in infrastructure development) shows that a sound procurement system includes:

procurement rules and procedures that are simple, clear and ensure access to procurement opportunities

effective institutions to conduct procurement procedures and conclude, manage and monitor public contracts

appropriate e-Procurement tools and coverage

suitable, in numbers and skills, human resources to plan and carry out procurement processes

competent contract management.

When auditing the procurement procedures applied in infrastructure development, ASF could also rely on the principles of the OECD Recommendation on Public Procurement (see Box 4.2).

Box 4.2. The OECD Recommendation on Public Procurement

The Recommendation on Public Procurement is the overarching OECD guiding principle that promotes the strategic and holistic use of public procurement. It is a reference for modernising procurement systems and can be applied across all levels of government and state-owned enterprises. It addresses the entire procurement cycle while integrating public procurement with other elements of strategic governance such as budgeting, financial management and additional forms of services delivery. It recommends adherents to:

1. Ensure an adequate degree of transparency of the public procurement system in all stages of the procurement cycle.

2. Preserve the integrity of the public procurement system through general standards and procurement-specific safeguards.

3. Facilitate access to procurement opportunities for potential competitors of all sizes.

4. Recognise that any use of the public procurement system to pursue secondary policy objectives should be balanced against the primary procurement objective.

5. Foster transparent and effective stakeholder participation.

6. Develop processes to drive efficiency throughout the public procurement cycle in satisfying the needs of the government and its citizens.

7. Improve the public procurement system by harnessing the use of digital technologies to support appropriate e-procurement innovation throughout the procurement cycle.

8. Develop a procurement workforce with the capacity to continually deliver value-for-money efficiently and effectively.

9. Drive performance improvements through evaluation of the effectiveness of the public procurement system from individual procurements to the system as a whole, at all levels of government where feasible and appropriate.

10. Integrate risk management strategies for mapping, detection and mitigation throughout the public procurement cycle.

11. Apply oversight and control mechanisms to support accountability throughout the public procurement cycle, including appropriate complaint and sanctions processes.

Source: (OECD, 2015[2]).

References

[1] European Commission (n.d.), Evalsed Sourcebook: Method and Techniques, https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docgener/evaluation/guide/evaluation_sourcebook.pdf#page=172 (accessed on 13 October 2021).

[3] OECD (2021), Hospital beds (indicator), https://doi.org/10.1787/0191328e-en (accessed on 22 September 2021).

[2] OECD (2015), “Recommendation of the Council on Public Procurement”, OECD Legak Instruments, OECD/LEGAL/0411, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/gov/public-procurement/OECD-Recommendation-on-Public-Procurement.pdf.

Note

← 1. In 2019, Mexico had one hospital bed per 1 000 inhabitants, being the OECD country with the lowest ratio (OECD, 2021[3]), Hospital beds (indicator), https://doi.org/10.1787/0191328e-en (accessed on 22 September 2021).