Building on the previous section, this chapter analyses alternatives for ASF’s audits to contribute to the success prospects of infrastructure projects through early interventions and consideration of the principles of the OECD Recommendation on the Governance of Infrastructure. It also discusses strategic considerations for ASF’s unit to audit infrastructure, including those relative to equipment, technologies, and human resources. Finally, it assesses the importance of real-time interventions to maximise the impact of infrastructure audits.

Facilitating the Implementation of the Mexican Supreme Audit Institution’s Mandate

3. Strategic considerations for ASF’s unit to audit infrastructure in Mexico

Abstract

ASF’s contributions to the success of infrastructure projects

ASF could better balance its focus on corruption prevention and the long-term success of infrastructure projects

The objectives and the value proposition of public works and infrastructure audits should balance better corruption prevention and the long-term success of projects, on the one hand, and sanctioning, on the other, and promote early interventions.

ASF’s Organisation Manual defines the objectives of the DGAIFF, namely:

Reviewing the public works, services, and acquisitions related to federal physical investments included in the public accounts and the Financial Management Progress Report (Informe de Avances de Gestión Financiera) authorised in the Annual Audit Programme for the Public Account (Programa Anual de Auditorías para la Fiscalización Superior de la Cuenta Pública, PAAF).

Auditing resources obtained through financing by the federal states and municipalities, guaranteed by the Federation, for physical investments to determine if such resources were applied legally and efficiently to fulfil the objectives and goals of approved policies and programmes.

Determining irregularities detected in audits to the planning, programming, budgeting, award, delivery, and payment of public works, services, and acquisitions relative to federal physical investments and undertaking the actions needed to remedy the damages.

The strategic reorientation of public works and infrastructure audits should aim to balance better prevention vis-à-vis sanctioning objectives. Here again, it is easy to identify the compliance oriented approach and the focus on “determining irregularities” and “remedy damages”, instead of preventing those irregularities and damages from the beginning. This is not to say that enforcement and sanctioning integrity and other kind of breaches are irrelevant. Sanctions can indeed become powerful deterrents of corrupt behaviour, in the understanding that corrupt acts depart from rationalisation (i.e. estimating the balance between benefits and costs stemming from the corrupt act and the chances of being caught). However, beyond that, a wider governance approach of infrastructure audits would facilitate prevention by, for example, defining accountability and control mechanisms throughout the different layers of management of a project.

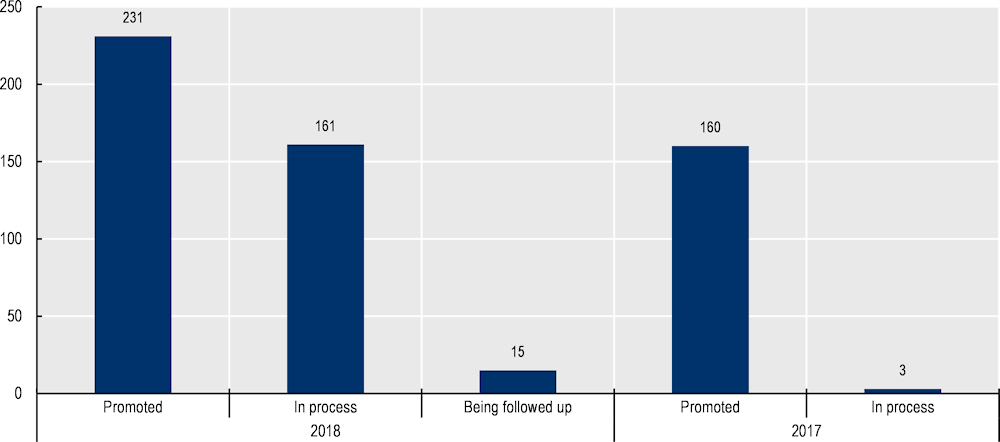

Figure 3.1. Evolution of administrative sanctions filed by ASF

Source: Information provided by ASF.

In addition, transparency and disclosure measures, for example, could prevent the undertaking of projects with weak social and economic justifications. To ensure the need and viability of future projects, ASF could assess, as part of its audits, the degree of transparency of the different impact and feasibility studies to select specific infrastructure projects. Indeed, public opinion has been particularly critical on the lack of transparency of the feasibility studies for projects like the Felipe Ángeles International Airport, one of the major infrastructure undertakings of Mexico’s current federal administration. For example, the aeronautical studies, which are key to demonstrate feasibility, have not been disclosed and are not accessible through the project’s website (www.gob.mx/nuevoaeropuertofelipeangeles), even though some technical studies are available (i.e. environmental impact, archaeology, etc.). Regarding this project, during February 2020, ASF signed an agreement with the Ministry of National Defence (Secretaría de la Defensa Nacional, SEDENA) to follow up the construction of the Airport. The agreement aims to strengthen ASF’s advanced and preventive interventions.

While this agreement illustrates the potential for preventive interventions by ASF, there is margin to allow for earlier interventions. Indeed, the earlier governance factors are considered, the better chance that issues will be prevented during the execution of the project and the higher the likelihood of a project’s long-term success. This is explicitly recognised, for example, in the UK’s Project Initiation Routemap (see Box 3.1).

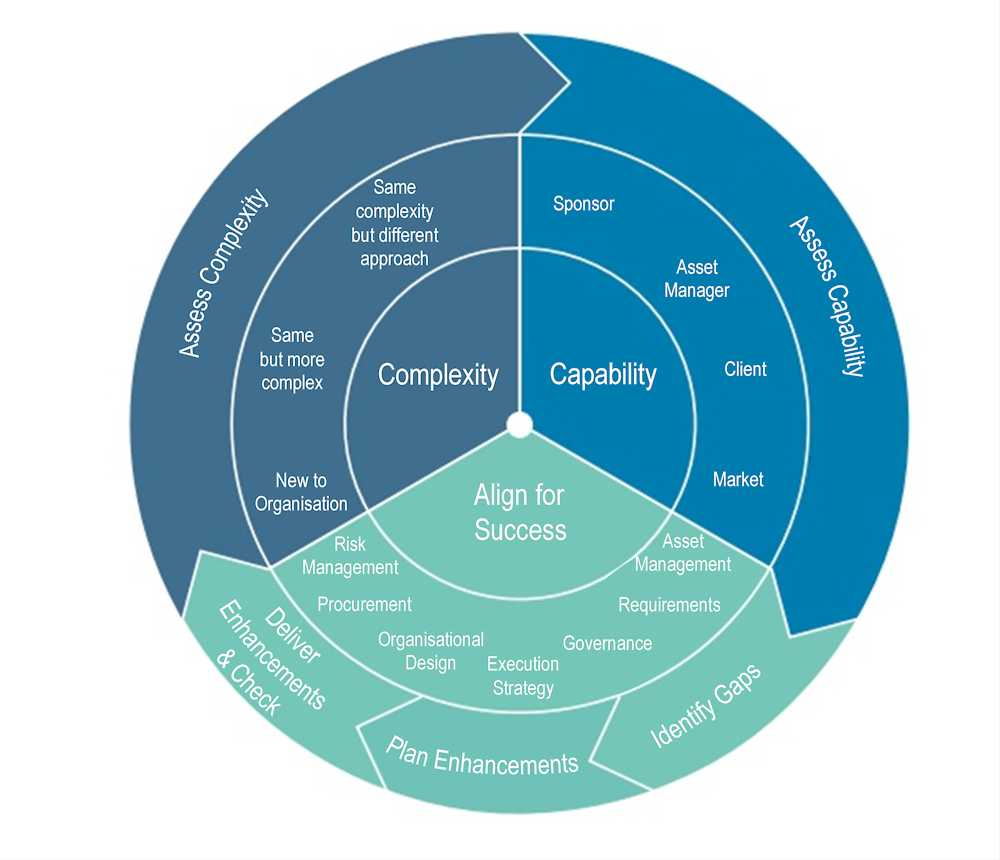

Box 3.1. The Project Initiation Routemap: Improving Infrastructure Delivery

In order to realise the benefits from infrastructure investment, the UK Government created the Infrastructure and Projects Authority (IPA) as the centre of expertise for project development and delivery. The IPA’s Cost Review and the National Audit Office (NAO) report on delivering major infrastructure projects identified the early stages of the project cycle as a common source of failures.

To address common pitfalls, the UK Government, working collaboratively with industry and the University of Leeds through the Infrastructure Client Group, developed the Project Initiation Routemap, which is a tool for strategic decision making. It supports the alignment of the sponsor and client organisations’ capabilities to meet the degree of challenge during initiation and delivery of a project. It provides an objective and systemic approach to project initiation founded on a set of assessment tools to determine:

Complexity and context of the delivery environment.

Capabilities of current and required sponsor, client, asset manager, and market.

Key considerations to enhance capabilities where complexity-capability gaps exist.

The Routemap helps organisations understand their current delivery environments and create the ones required. The intention is addressing issues as early as possible in the project life cycle. As Prof. Denise Bower, Executive Director of the Major Projects Association, put it “The issues that lead to poor execution of major projects are not usually rooted in individual shortcomings, they are systemic failures that should have been addressed during initiation”.

Source: (IPA, 2016[1]).

In a special report published in October 2017, ASF also advanced the preventive features of its work, suggesting particular risks for heightened attention by public managers and auditors, although not for a specific project. The ASF report General issues relative to public works and services related 2011-16 (Problemática General en Materia de Obra Pública y Servicios Relacionados con las Mismas 2011-2016) analyses 92 infrastructure projects whose procured amounts exceeded MXN 100 million and which suffered adjustments of at least 30% in the investment amount or the execution timeline (ASF, 2017[2]). This report follows up a previous one that had analysed 80 projects executed during 1999-2010. The major sources of issues for infrastructure delivery were classified in four categories:

Planning and programming: Incomplete planning relative to the scope of the project, its value-for-money, poor contract design, lack of definition of procurement procedure, and payment, considering insufficient funding, as well as lack of co-ordination to obtain the required licenses and permits and decisions based on political criteria, rather than technical ones.

Technical: Insufficient development of executive projects, which leads to engineering failures, lack of definition of the technology to be used in the execution of the works, or insufficient detail of the site of the works. Other technical shortcomings identified include lack of or poor previous studies (i.e. soil, environmental, geology, etc.), lack of definition of technical and quality norms, as well as general and particular specifications for the works, inadequate awards out of poor assessments, and lack of technical staff to prepare the projects and assess the bids submitted.

Economic: Delays in the allocation and availability of resources, late transfers between programmes, downsized budget during the execution stage, lack of capital by contractors, cost and timeliness in the delivery of supplies.

Execution: Unreal timelines or projected costs, which do not correspond to the complexity of the works, late processing of advanced payment, poor compliance by contractors and supervisors, lack of control in subcontracting, technical issues due to misalignment with construction specifications and quality standards for supplies and materials, delays in the formalisation of modification agreements, authorisation of cost adjustments, broken suppliers, poor supervision and control of the works, poor quality or unfinished works, social or union issues, and untimely operation tests.

The issues identified in the report are similar to the common causes of programme/project failure described in the UK Cabinet Office Review Guidance (see Box 3.2).

Box 3.2. The common causes of programme/project failure identified in the Cabinet Office Review Guidance

Lack of clear link between the project and the organisation’s key strategic priorities, including agreed measures of success.

Lack of clear senior management and ministerial ownership and leadership.

Lack of effective engagement with stakeholders.

Lack of skills and proven approach to project management and risk management.

Too little attention to breaking development and implementation into manageable steps.

Evaluation of proposals driven by initial price rather than long-term value-for-money.

Lack of understanding of and contact with the supply industry at senior levels in the organisation.

Lack of effective project team integration between clients, the supplier team, and the supply chain.

Source: (IPA, 2016[1])

This work is extremely valuable as it provides guidance to infrastructure project managers and auditors on important considerations to avoid problems during the different stages of the project cycle. In fact, this work could be the basis for ASF to develop a guide for auditors to carry out early interventions with specific criteria to review, just like the criteria enlisted in the Project Initiation Routemap (see Box 3.3).

Box 3.3. The Project Initiation Routemap: Criteria for Assessment

The Routemap tools assess the capabilities of the sponsor, client, asset managers, and the market, as well as the complexity of the project environment. The analyses facilitate the identification of areas of alignment and misalignment. It contains detailed checklists to use during the initial assessment steps, advice on how to undertake the gap analysis and what to include in the plans to enhance the project environment.

Complexity assessment: A set of 12 factors that determine complexity, which are strategic importance, stakeholders, requirements and benefit articulation, stability of overall context, financial impact and value-for-money, execution complexity, interfaces, range of disciplines and skills, dependencies, extent of change, organisational capability, and interconnectedness.

Capability assessment:

Sponsor: Improving the understanding of the requirements for the sponsor’s capability during the investment and delivery planning process.

Asset manager: Analysing key operational constraints and requirements.

Client: Considering the ability of the client organisation to engage effectively with the supply chain and manage the delivery outcomes.

Market: Understanding market ability and appetite to respond to requirements.

Align for success modules: Provide organisations (sponsors and clients) with advice to enhance capabilities relative to requirements, governance, execution strategy, organisational design and development, procurement, risk management, and asset management.

Figure 3.2. Organisation of the Project Initiation Routemap

Leveraging on the OECD Recommendation on the Governance of Infrastructure

ASF could guide its efforts to audit the governance of infrastructure based on the OECD Recommendation

The G20 Principles on Quality Infrastructure Investment highlight that “sound infrastructure governance over the life cycle of a project is a key factor to ensure long-term cost-effectiveness, accountability, transparency, and integrity of infrastructure investment” (G20, 2019[3]).

The governance of infrastructure depends on multiple institutional, social, economic, and environmental factors, and it should align with a framework that ensures strategic planning, performance, and resilience of public infrastructure throughout the life cycle of projects. Indeed, the governance of infrastructure projects has been recognised as a key determinant of success (or failure).

According to the UK Office of Government Commerce (OGC), five out of the eight causes of project failure identified in 2005 were attributable to weak governance. In contrast, OGC found that seven out of the ten common causes of confidence identified in 2010 were attributable to good governance. Similarly, PwC’s 2012 Global Study on Project Management Trends identified that weak governance was the main contributor to project failure. Likewise, the Infrastructure UK Cost Review Report 2010 and the NAO’s Guide to Initiating Successful Projects stress the importance of good governance by highlighting the need for a greater focus on the early stages of projects to ensure that they are set up to succeed, establishing the right delivery environment and capability to match the complexity of the project (OECD, 2015[3]).

In light of this, after a broad consultation that included internal and external stakeholders and that collected more than 426 comments from 67 participants from 29 countries, the OECD Council adopted the Recommendation on the Governance of Infrastructure on 17 July 2020. This is a tool to support governments to invest in infrastructure projects in a way that is cost effective, affordable, and trusted by investors, citizens, and all stakeholders. It introduces 10 principles that relate to how governments prioritise, fund, budget, deliver, operate, and monitor infrastructure assets (OECD, 2020[3]). As is the case with other OECD Council Recommendations, the one on the governance of infrastructure stems from policy dialogue, the experience and good practices of member countries and, in this sense, it indicates where country policies should converge.

The Recommendation emphasises the development of a long-term strategic vision for infrastructure and a coherent and accountable institutional framework to ensure a well-functioning infrastructure investment system. Additionally, it stresses the need for fiscally sustainable decision making throughout the planning, budgeting and delivery stages of infrastructure projects taking into account the entire life cycle costs. Strengthening public procurement processes in infrastructure and meaningful stakeholder engagement are also key aspects. The Recommendation further promotes coherent and efficient regulatory frameworks and a whole-of-government approach to manage threats to integrity. Finally, it encourages Adherents to ensure infrastructure is up to date with the impacts of technology and promotes harnessing digital technologies and data analytics to ensure evidenced-based decision making (see Figure 3.3).

Figure 3.3. The 10 principles in the OECD Recommendation on the Governance of Infrastructure

Brazil’s Federal Court of Accounts (TCU) adopted a governance approach to audit the country’s electric sector (see Box 3.4). Likewise, United Kingdom’s IPA recognises the value of good governance assurance to determine:1

Whether the project/programme has appropriate decision‑making processes and structures in place with defined responsibilities.

Whether mandates at all levels exist so there is clarity over who is responsible for what, and who accounts to whom for what.

Whether decisions are being made at the appropriate level in accordance with mandates.

Whether project/programme governance arrangements are evolving as the programme matures to reflect varying stakeholder requirements and emerging needs.

Whether project/programme governance is linked with the governance arrangements within the parent or target business.

IPA has focused on the governance of infrastructure, particularly in the early stages, and issued its Principles for Project Success (see Box 3.5).

Box 3.4. TCU audits of the governance of Brazil’s electric sector

TCU’s Department of External Control – Electric Power Infrastructure (SeinfraElétrica) and the Department of Special Operations in Infrastructure (SeinfraOperações) adopted a governance approach to audit the country’s electric sector. SeinfraElétrica is a team of 38 auditors who oversee the formulation and conduction of public policies, regulation, and privatisation of the electric and nuclear sectors. It also oversees the management and enterprises of State-owned companies (SOE’s). Some examples of SeinfraElétrica audits are the following:

Structuring of large hydroelectric projects.

Participation by thermoelectric plants in the national electric matrix.

Public policies on renewable energy.

Subsidies in electric bills.

Nuclear thermoelectric plant Angra 3.

Emergency activities related to COVID-19.

TCU conclusions indicate that sector plans are technical and transparent and the main principles applied are objective and up-to-date. However, TCU also points out several shortcomings, such as:

Long-term planning does not define expected results and scenarios.

Lack of indicators in sector plans.

Lack of co-ordination between sector institutions.

Absence of a forum to discuss strategic issues.

Lack of impact assessment studies before relevant decisions.

Source: Presentation by TCU officials during the OECD webinar “Auditing the governance of infrastructure”, held on 2-4 June 2021.

Box 3.5. IPA’s Principles for Project Success

The Principles for Project Success are intended as core propositions or “basic truths” to guide thinking and behaviour in project delivery. They are designed as short, memorable headlines supported by explanatory bullets and further resources. The basic assumption behind the Principles is that project success or failure is often determined in the early stages and whilst successful project initiation can take more time at the start, it will be repaid many times over later on in delivery.

The eight principles were developed following widespread consultation with project professionals across government and other sectors.

1. Focus on outcomes

2. Plan realistically

3. Prioritise people and behaviour

4. Tell it like it is

5. Control scope

6. Manage complexity

7. Be an intelligent client

8. Learn from experience

Strategic considerations for ASF’s unit to audit infrastructure

ASF could undertake a gap analysis to understand the resources and technologies required to fulfil its strategic objectives relative to auditing infrastructure governance

ASF is considering the implementation of new mechanisms and tools to enhance its infrastructure audit work. An important first step in this endeavour is defining strategic objectives for the adoption of such technologies, including building the capacities for remote audits. Indeed, surveys conducted within the SAI community concerning the impacts of the COVID-19 crisis revealed that the main challenge has been the lack of ICTs to conduct remote audits.2

Some of the most important tools ASF is considering include equipment for physical verification such as drones and GPS to quantify the volumes. These tools would support ASF in presenting results based on better evidence and assessing if the execution of the works met the objectives. Likewise, they will be useful to determine their performance and resilience, which are part of the OECD Recommendation on the Governance of Infrastructure. Other anticipated equipment include distance meters, odometers and batimetric catamarans.

While these resources will certainly improve ASF capabilities, it is important to have an assessment of those that would be required to deepen the work on infrastructure governance and meet strategic objectives, particularly on elements such as performance and resilience. ASF could complete such assessment and develop an investment plan aligned with perspectives to widen the portfolio of infrastructure audits.

The same kind of gap analysis is pertinent for human resources, not only in terms of staff numbers, but also of capacities and skills

According to the International Organisation of Supreme Audit Institution (INTOSAI) Development Initiative’s Strategic Management Handbook for SAIs, assessments can be carried out as a step in strategy development, so that capacity gaps are determined in relation to defined objectives and outputs (INTOSAI, 2020[5]).

Currently, the team to audit infrastructure is composed by 206 officials, including 33 of senior level management, 147 auditors, and 26 support staff. The prevailing expertise of the team to audit infrastructure is on architecture and civil engineering, but there are as well specialists on accounting, law, chemical and oil engineering, territorial planning, urban studies, communications, and hydraulics.

In order to strengthen its human capacities to audit infrastructure and public works, ASF should pursue the following actions:

Growing the staff base to allow for the establishment of multidisciplinary working groups to advance comprehensive audits including technical, legal, accounting, financial, and scientific issues to strengthen audit impact.

Training staff on infrastructure auditing and implementation of audit techniques following international professional standards, particularly for the construction of infrastructure relative to roads, dams, rail, airports, hospitals, energy production and transmission, telecommunications, ports, and residual water management, among others.

Certifying staff to increase results-based audit capacities.

While the plans to upgrade ASF’s staff base and infrastructure audit capacities and powers are ambitious, the senior leadership also recognises obstacles, such as the following:

Budget restrictions to hire staff and procure equipment, as well as to fund training initiatives.

Complex processes for legislative reforms.

Tight deadlines that restrict the time to review audit projects and outcomes.

The fact that real-time audits are subject to reports.

Strict timing criteria for the review and determination of actions hindering ASF capacities to recover resources or promote sanctions.

Lack of a homogeneous regulatory framework for public works.3

A wider approach to infrastructure audit, prescribed by law, would provide ASF with elements to make the case for stronger infrastructure audit capacities and therefore to ask Congress the required resources. More comprehensive infrastructure audits would pay for themselves by facilitating early interventions and increasing the chances for infrastructure projects success, thereby avoiding investments in poorly justified projects and advancing value-for-money.

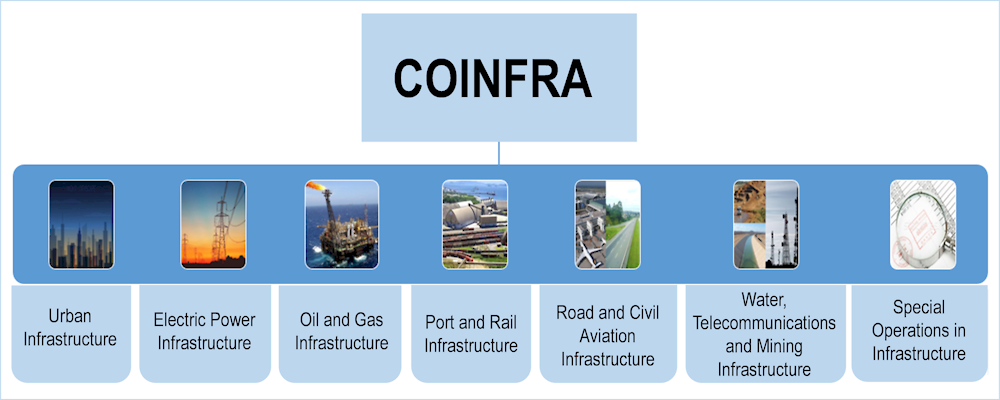

Regarding the organisational structure of the infrastructure audit team, it can be arranged according to sectors, such as in TCU’s organisational structure. The TCU Office of the General Coordinator for the Infrastructure Sector (Coinfra) is divided into seven branches for its 267 auditors, spread in the five regions of Brazil (see Figure 3.4).

Figure 3.4. Coinfra’s organisational chart

Source: Presentation by TCU officials during the OECD webinar “Auditing the governance of infrastructure”, held on 2-4 June 2021.

Box 3.6. Skills and expertise in support of NAO’s strategy

NAO developed a five-year strategy to ensure it provides effective support to Parliament in scrutinising public sector performance, while making insights available to those responsible for public services. Its strategic priorities are i) improving support for effective accountability and scrutiny; ii) increasing impact on outcomes and value-for-money; and iii) providing more accessible and independent insight. One of the strategic enablers to accomplish this strategy is attracting, retaining, and developing high quality people. In this context, NAO defined key areas of cross-cutting expertise:

Analysis

Commercial

Digital

Financial and risk management

People and operations

Major project delivery

Skills are developed through several mechanisms, including on-the-job learning, seminars, support to teams, training, embedding experts, and links with external organisations.

Source: Presentation by NAO officials during the OECD webinar “Auditing the governance of infrastructure”, held on 2-4 June 2021.

The potential of real-time audits

Real-time audits are key to allow ASF to timely intervene at the different stages of infrastructure projects

During interviews, ASF staff recognised that the fact that real-time audits can only be launched after legally justified reports of irregularities is a significant obstacle for timely interventions. The timing of audits was also recognised as a major challenge by NAO officials who participated in an OECD workshop on “auditing the governance of infrastructure” in June 2021.

As the 2021 OECD Progress report on the implementation of the Mexican Superior Audit of the Federation’s mandate: Increasing impact and contributing to good governance4 stresses, limitations to real-time audits render ASF reactive and unable to take preventive actions or conduct audits before receiving complaints. This capacity would be key to address the recommendation to balance better prevention and the long-term success of infrastructure projects, on the one hand, and sanctioning, on the other, and promote early interventions. In this sense, the reforms ASF could implement to advance its powers to conduct real-time audits would be key to adopt a wider governance approach in infrastructure auditing.

Not only real-time audits in infrastructure would help preventing risks of ineffective exercise of resources or plain corruption, but would also allow ASF to play a role in ensuring that infrastructure projects are planned and designed for success from the early stages. For example, real-time audits would allow the timely identification of inefficiencies (e.g. overspending on specific portfolios which might not be a priority for a major infrastructure undertaking) or red flags (e.g. several contracts awarded to the same construction firm) and suggest corrective measures, as well as maximise the deterrent effect of audits.

Congress should take prompt actions to review ASF’s legal framework and expand its powers to undertake real-time audits, particularly on infrastructure. This could take place by anticipating a broader set of triggers for real-time audits, beyond the report of irregularities, or by granting ASF ex ante audit powers.5 This is more relevant than ever in light of the questions surrounding the success perspectives of major infrastructure projects such as the Felipe Ángeles International Airport and the Dos Bocas Refinery. ASF is well placed to feed an evidence-based discussion on such perspectives through its independent and objective assessment. Furthermore, the infrastructure investment planned in the draft Expenditures Budget for 2022 can be a powerful lever for economic recovery, but will only see its impact maximised if the success of the projects and a timely execution are guaranteed. The fact that most observations in public works audits during 2015-17 refer to the execution stage (see Chapter 4 on “Risk analysis to inform audit programming and selection”) calls to allow ASF to undertake real-time audits.

References

[6] ASF (2017), Problemática General en Materia de Obra Pública y Servicios Relacionados con las Mismas 2011-2016, https://www.asf.gob.mx/uploads/256_Informes_Especiales/Informe_Especial_Obra_publica.pdf (accessed on 4 August 2021).

[5] G20 (2019), Principles on Quality Infrastructure Investment, https://www.mof.go.jp/english/policy/international_policy/convention/g20/annex6_1.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2021).

[3] Infrastructure and Projects Authority (2020), Principles for Project Success, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/901126/IPA_Principles_for_Project_Success.pdf.

[7] INTOSAI (2020), Strategic Management Handbook for Supreme Audit Institutions, https://www.idi.no/elibrary/well-governed-sais/strategy-performance-measurement-reporting/1139-sai-strategic-management-handbook-version-1/file (accessed on 12 August 2021).

[1] IPA (2016), Improving Infrastructure Delivery: Project Initiation Routemap, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1057650/2641_IPA_Modules_Handbook.18__2_.pdf.

[2] OECD (2020), Recommendation of the Council on the Governance of Infrastructure, OECD/LEGAL/0460, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/gov/infrastructure-governance/recommendation/.

[4] OECD (2015), Effective Delivery of Large Infrastructure Projects: The Case of the New International Airport of Mexico City, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264248335-en.

Notes

← 1. Presentation by IPA officials during the OECD webinar “Auditing the governance of infrastructure”, held on 2-4 June 2021.

← 2. INTOSAI Policy Finance and Administration Committee’s COVID-19 Initiative (forthcoming), Coronavirus Pandemic: Initial Lessons Learned from the International Auditing Community.

← 3. Currently, there are different legal regimes according to the funding sources of public works. If they are financed with federal resources, then the federal framework applies. However, if public works are financed with state or municipal resources, then the corresponding state legal framework applies. There are 32 federal states in Mexico and therefore 32 different state legal frameworks for public works. Additionally, the state productive enterprises, PEMEX and the Federal Electricity Commission (Comisión Federal de Electricidad, CFE), as well as Mexico’s National Autonomous University (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México), the Metropolitan Autonomous University (Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana), and the legislative and judicial powers, have their own regulatory frameworks for public works.

← 4. Available at https://www.oecd.org/governance/ethics/progress-report-on-the-implementation-of%20the-Mexican-Superior-Audit-of-the-Federation-s-mandate.pdf.

← 5. OECD has found that the idea of granting SAIs ex ante powers is controversial in some Latin American contexts given the potential for abuse of power.