This chapter analyses the potential of foreign direct investment (FDI) to improve labour market outcomes. It assesses the impact of FDI on employment creation and wage conditions across sectors and Tunisian governorates. It also examines how foreign firms in Tunisia contribute to gender equality and skills development, through training practices, but also to reducing possible skills imbalances.

FDI Qualities Review of Tunisia

3. FDI impact on job quality and skills

Abstract

3.1. Summary

An abundant, young and skilled workforce has made Tunisia an attractive destination for foreign direct investment (FDI). The contribution of FDI to labour market outcomes in Tunisia is crucial for an economy where informality and unemployment are high by international standards, particularly among the youth, women, the highly educated and in Tunisia’s hinterland regions. As in other countries of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, such as Jordan, stalling business dynamism, combined with skills imbalances, has limited employment opportunities for a steadily increasing and more educated Tunisian labour force. The public sector has absorbed a large number of new graduates and continues to offer attractive working conditions but also limits labour mobility from the public to the private sector.

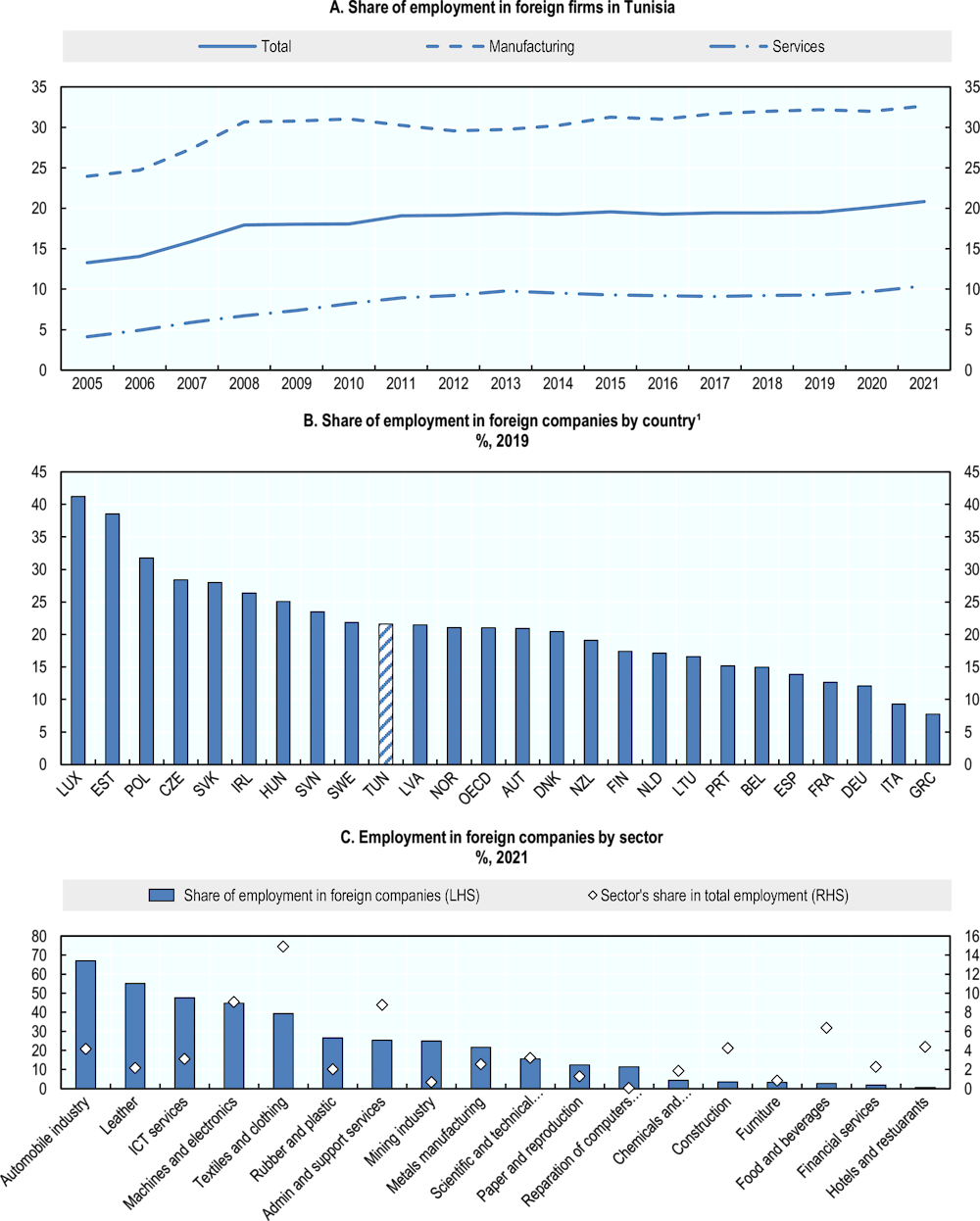

FDI in Tunisia has strongly contributed to job creation, improved living standards and enhanced skills, but its impact has been uneven across the population and regions. In 2021, one out of five private sector workers were employed in a foreign firm – 34% in manufacturing and 10% in services, among which 95% in foreign offshore firms. Tunisian offshore firms employed 22% of workers in Tunisian companies. The number of workers in foreign firms has doubled since 2005, but many jobs are in low-skilled occupations, created by multinationals exporting automotive components, textiles and clothing, and mechanical and electronics products. Jobs created in services rely more on high-skilled workers, particularly in ICT, business, scientific and technical services, where foreign firms account for 24% to 44% of sectoral employment. Despite attracting half of FDI inflows, jobs created by FDI in the metropolitan area of Tunis – the Grand Tunis – represent 28% of all FDI jobs compared to 34% for the coastal Northeast region.

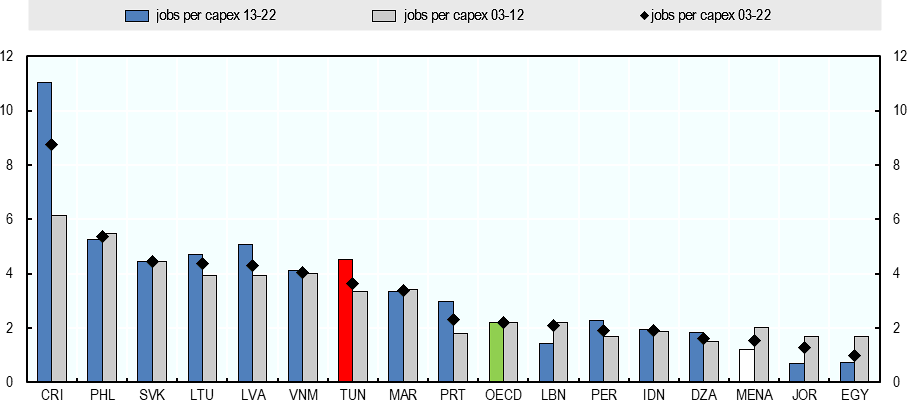

The job creation intensity of greenfield FDI Tunisia is one the highest of the MENA region – 3.6 jobs created on average for each million of USD invested - and significantly higher than the OECD average. It has also increased in the past decade, partly driven by a shift in FDI to labour-intensive assembling activities of the electronic components sector. Even if most jobs created are in Tunisia’s labour-intensive manufacturing activities, job creation from greenfield FDI in some services activities has also expanded in the past decade. Business services, R&D, sales and marketing – activities that may better fit the highly-educated young job seekers – contributed to 12% of new jobs created by greenfield FDI during 2013-2023, twice as much as in 2003-2012. On the other hand, the job creation intensity of FDI in textiles was halved, indicating a sharp decrease in the labour-intensity of the sector due to increased competitive pressures from other emerging markets with lower labour costs.

The job creation performance of FDI in Tunisia has only partly translated into wage and non-wage improvements, which are key to lift standards of living of the population, including women. Foreign firms pay, on average, only marginally higher wages than Tunisian firms, although large variations exist across sectors. Despite increases in recent years, wages in foreign industrial firms continue to be lower than among Tunisian peers as the former operate primarily in low-skilled, low-productivity activities of the automotive equipment and electrics-electronics sectors; exceptions exist in sectors such as minerals, mining, and machine repairing. The impact of foreign firms on gender outcomes is also mixed. The majority of employees in foreign firms are women but these women are mostly employed in low-skilled jobs. Furthermore, foreign firms do not necessarily contribute to improving access of women to managerial roles.

Foreign firms in Tunisia operate in a labour market with large skills imbalances – a misalignment between the demand and supply of skills leading to skills mismatches and shortage, partly stemming from a high number of university graduates and low job creation for the highly skilled. Foreign firms have little impact on improving this imbalance since they operate mostly in sectors relying on low-skilled workers. They also employ fewer skilled workers than foreign firms in other comparator countries. There is scope for skills and knowledge spillovers in the business services sector, as one fourth of firms are foreign. Furthermore, foreign firms are twice as likely to offer training to its employees as Tunisian firms, thereby supporting skills upgrading.

Policy directions

Align investment policy and promotion goals with Tunisia Vision 2035 and employment and skills development plans aiming to boost private sector employment and Tunisia’s ambition to become a knowledge-based economy. This implies a balanced approach towards job creation in the investment promotion strategy by continuing to target labour-intensive sectors for job creation, including outside of the Grand Tunis Area, while expanding efforts to target skill-intensive segments of the automotive and electronics sectors’ value chains and services sectors such as business services and ICT that support Tunisia’s digital transition.

Reassess existing restrictions on FDI against objectives of stimulating labour demand in the job-creating, skills-intensive services sectors. Restrictions on foreign ownership exist in business services, distribution, ICT, tourism, and transports, sectors where FDI has the potential to create jobs for both the low and highly-skilled Tunisian job seekers, including women. Overall, as indicated by the OECD Economic Survey of Tunisia 2022, pursuing pro-competition reforms will contribute to a more dynamic private sector that creates more and better jobs.

Improve investment promotion and facilitation efforts based on the existing skills base and labour market potential to lower information barriers for investors. This includes clear information on labour market characteristics, regulations, existing training programmes and incentives, and supporting investors in identifying suppliers with high labour standards. Tax incentives could support training by firms, including of women and local suppliers. Furthermore, consider introducing pre-employment training programmes to rapidly respond to skills needs of potential new investors or support them establishing their own training facilities.

Establish robust monitoring and evaluation mechanisms to effectively assess the impact of FDI on employment and job quality and anticipate skills shortage of foreign firms. This requires availability and access to representative firm-level statistics, based on the Répertoire National des Entreprises, providing information on foreign ownership, employment by gender, wages and non-wage working conditions, and spending on training. This necessitates improving coordination between the INS, FIPA, and APII. Consider involving FIPA in skill needs and anticipation exercises to design and implement active labour market policies and skills development programmes that target the skills needs of foreign firms.

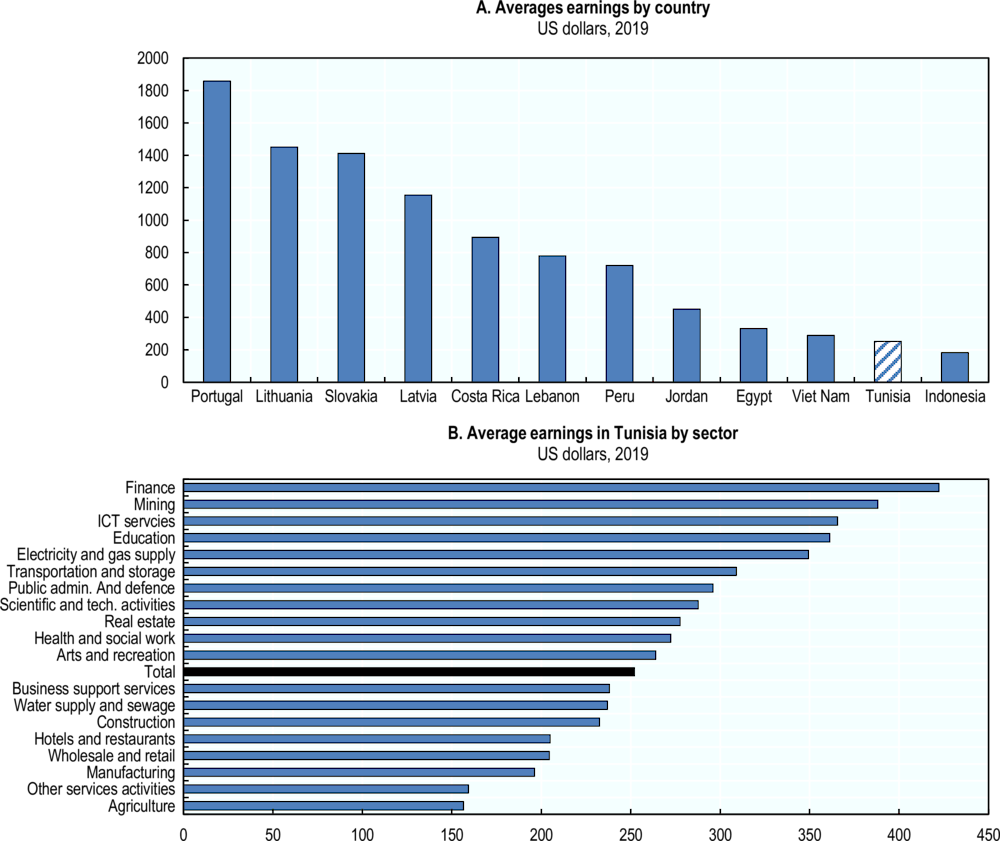

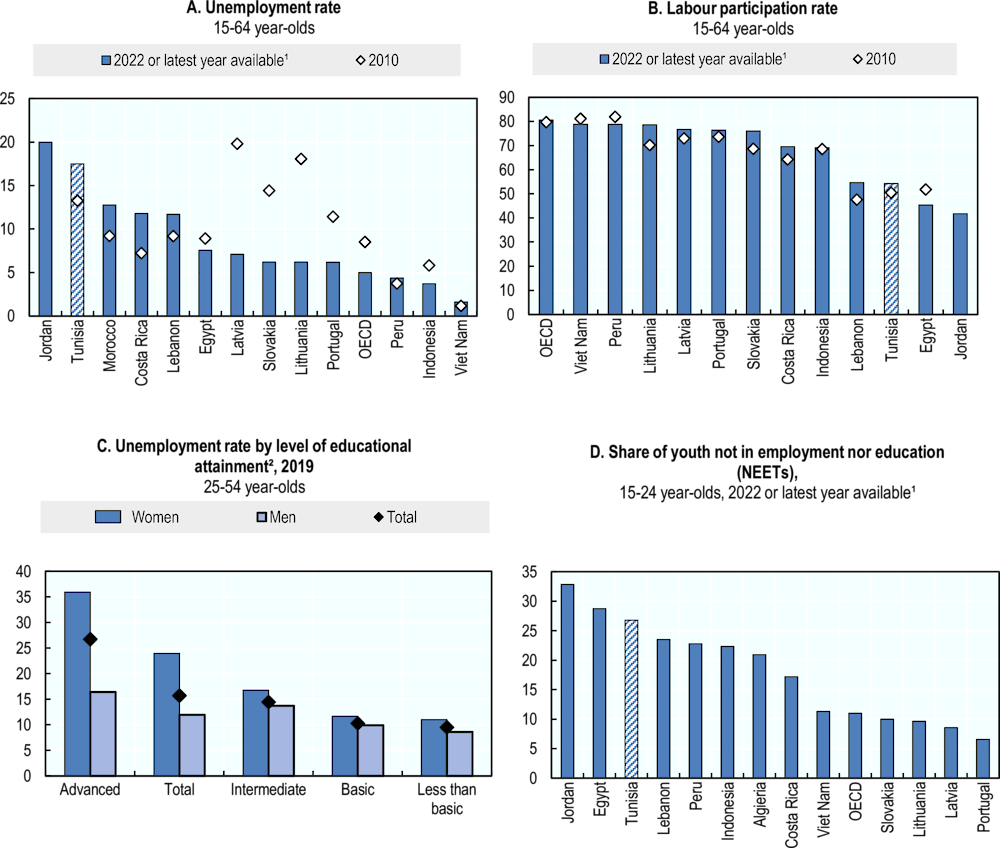

3.2. Key challenges and opportunities for Tunisia’s labour market

The Tunisian workforce is young and increasingly educated, but tremendous labour market challenges exist. Unemployment rose from 13% in 2010 to more than 16% in the fourth quarter of 2023; higher than in peer MENA countries, except Jordan (Figure 3.1, panel A). The unemployment rate of the 15-24 year-olds reached 40%. Labour force participation is similar to that of other MENA countries but remains low by international standards: only about half of the working-age population were either in formal employment or actively looking for work in 2019 (Figure 3.1, panel B). This is due to a particularly low labour participation of women, at 28% against 77% for men. A large share of the Tunisian population is in informal employment - almost 40% of total non-agricultural employment - and informality rate exceeded 65% of total employment in sectors such as agriculture, construction, and wholesale and retail trade in 2019 (INS, 2020[1]). Informality is often linked with job insecurity, lack of social security insurance and lower wages, thus contributing to precarity for workers and significant inequalities in the labour market.

3.2.1. Low business dynamism has led to limited employment growth opportunities

Highly educated Tunisian youth and women are facing the greatest challenges on the labour market. The Tunisian population has been growing steadily at a rate of 2% until the mid-1990s, resulting in a rapid expansion of the working-age population (Boughzala, 2019[2]). Rising access to education has improved the education outcomes of women, who make up more than 60% of university graduates. The share of working age population with a tertiary degree has quadrupled since the 1990s, but sluggish growth and low job creation, particularly for educated and skilled workers, have not been sufficient to absorb the increasing number of graduates (OECD, 2022[3]). Among the 25-55 year-olds with tertiary education, 27% were unemployed in 2019, almost twice the national average and one of the highest rates in the MENA region (Kthiri, 2019[4]). The unemployment rate for women with advanced degrees was even higher, at 36%, hampered by cultural gender roles and norms and limited availability of affordable childcare services (World Bank, 2022[5]) (Figure 3.1, panel C). Limited opportunities for youth are particularly concerning as two thirds of the unemployed are under the age of 30. Furthermore, 28% of youth were neither in education nor employment (of which two-thirds were women), a share higher than that of many peer economies and the OECD average of 11% (Figure 3.1, panel D).

Figure 3.1. Labour market conditions in Tunisia

Note: 1. Data refers to 2021 for Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, and 2019 for Lebanon and Tunisia. 2. Advanced: tertiary education; intermediate: upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary education; basic: primary and lower secondary education; less than basic: pre-primary education.

Source: ILO Labour Force Statistics (ILO, 2024[6]); OECD Labour Force Statistics, (OECD, 2024[7]), https://stats.oecd.org/

Despite periods of economic growth and important business climate reforms, job creation in Tunisia has been weak due to limited business dynamism and productivity growth, and this particularly affects the highly-educated youth and women (OECD, 2021[8]). Costly and anti-competitive administrative regulations, political uncertainty, and weak incentives to invest limit the entry and exit of firms on the market and hence the efficient reallocation of resources (see Chapter 2). Further reforms to improve product market competition, together with increased labour market flexibility, would improve business dynamism and help create formal jobs (Belgacem and Vacher, 2023[9]). Many Tunisian firms are small, often micro-enterprises that offer low-skilled and low-paid jobs, and the labour market lacks high-end jobs for the increasing number highly skilled workers (Boughzala, 2019[2]). The increasing number of graduates with tertiary education and the lack of adequate employment opportunities exacerbate the existing skills imbalances on the labour market.

3.2.2. Job creation has been uneven across sectors and regions

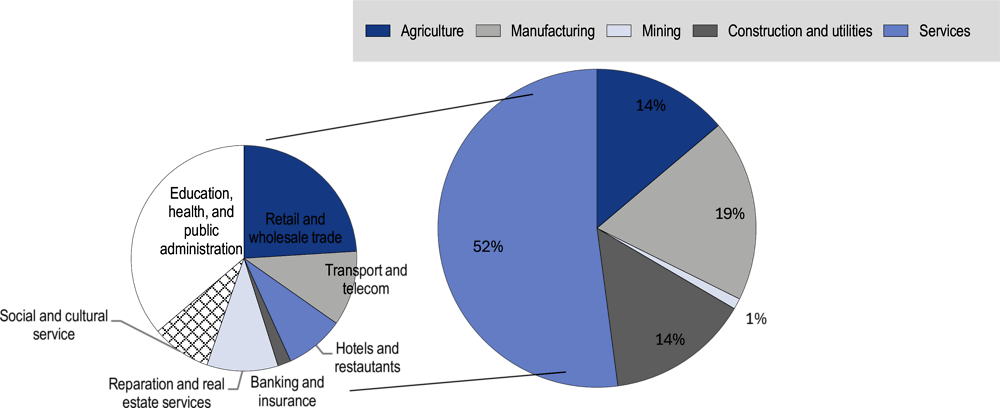

Many of the jobs in Tunisia are in low-productivity sectors with low-skilled employment. The services sector is the largest employer, with more than one fourth of jobs in either transport, repair, tourism, or retail (Figure ). Retail trade and the construction sector were the main sectors driving employment growth since 2007 (OECD, 2022[3]). The more productive banking and insurance sector accounts for only 2% of services employment and 1% of total employment. Manufacturing jobs in textiles, mechanical and electrical industries, and food and beverages, combined, make up three-quarters of all manufacturing employment (Figure 3.2). These sectors, while important for employment, rely mostly on jobs requiring intermediate or basic educational attainments and offer modest wages. Employment growth in the mechanical and electrical industries was the main contributor to employment growth in manufacturing since 2007, while the relative importance of textiles declined.

Figure 3.2. Employment in Tunisia is concentrated mostly in services

Share of employment by broad sectors, 2019

Despite limited productivity growth, the public sector has expanded in the past decade on the back of hiring expansion and wage increases. Employment in the public sector makes up about one-fifth of total employment and attracts highly educated youth and women – public administration has absorbed most of the university graduates since 2007 and has contributed significantly to overall employment growth (OECD, 2022[3]). While jobs in the public sector do not necessarily offer better starting salaries to recent graduates, many of these graduates find such jobs attractive because of additional benefits such as job security, guaranteed pay increases, long maternity leave or flexible working hours (World Bank, 2022[5]).

Unequal private sector development across regions has also contributed to disparities in the labour market, with unemployment ranging from below 10% in some coastal governorates to almost 30% in some southern and western regions. Mountainous and rural regions in the west and south face limited non-agricultural employment opportunities, especially for skilled workers (Boughzala and Hamdi, 2014[11]). The Northeast and Central East coastal regions have traditionally attracted labour-intensive economic activities thanks to their strategic location for maritime export, investments in infrastructure and the development of industrial clusters. While this has helped reduce unemployment, employers still struggle to find an adequate workforce in many sectors due to limited labour mobility across regions related to structural and cultural factors (OECD, 2022[3]).

3.3. The contribution of FDI to employment

3.3.1. Foreign companies employ one out of five workers in the private sector

Trade and investment liberalisation, the creation of the “offshore regime”, and a competitive and abundant labour force have contributed to attracting FDI with large consequences on firm and employment dynamics in Tunisia. The share of employment in foreign companies has been expanding, rising from 13% of formal private sector employment in 2005 to 21% in 2021 (Figure 3.3, panel A). Compared to other countries, this share is similar to the OECD average but lower than in some small open economies such as Czechia, Slovakia or Ireland (Figure 3.3, panel B). In absolute terms, private sector employment in foreign firms doubled between 2005 and 2021, while employment in domestic firms grew by 20%. Over 200 000 workers were employed in foreign companies in 2021, across all economic sectors.

Foreign presence has been prominent in manufacturing, with 34% of private sector employment in foreign companies in 2022, in contrast with services where this share was 10% (Figure 3.3, panel A). In some manufacturing sectors that have attracted large amounts of FDI, foreign firms account for at least 45% of employment – namely automotive components, leather and shoes, and mechanical and electronics (Figure 3.3, panel C). Combined, these sectors represent around 15% of total private sector employment and 31% of manufacturing employment. Foreign manufacturers’ contribution to employment in the food industry is low while the sector creates many jobs – the food sector is strongly regulated and has a large presence of SOEs (World Bank, 2014[12]). In the services sector, foreign firms’ presence is largest in ICT, business support services, and scientific and technical services, where they account for 24% to 44% of sectoral employment (INS, 2022[13]). Overall, services sectors are more restrictive to FDI than manufacturing. For instance, foreign firms account for about 1% of employment in transport and storage, tourism, education, and health.

Figure 3.3. Share of employment in foreign companies

% of foreign firms in total private sector employment

Note: Data in all figures refers to private sector employment. 1. For reasons of data comparability, country aggregates exclude agriculture, financial and insurance activities, education services, healthcare, arts, entertainment and recreation, other services, and public administration (corresponding to ISIC rev. 4 sectors B-N, excluding K).

Source: OECD calculations based on (INS, 2023[14]) Répertoire National des Entreprises; and (OECD, 2023[15]), OECD AMNE Database, https://www.oecd.org/sti/ind/analytical-amne-database.htm.

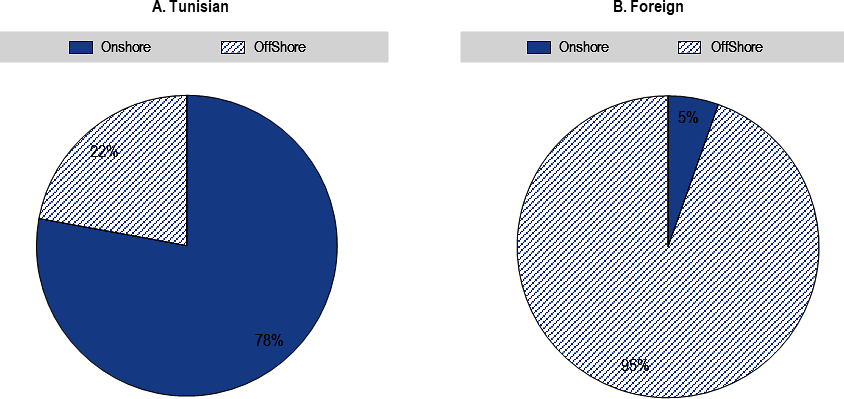

The majority of foreign manufacturers operate under the offshore regime, meaning that they export nearly all their production (see Chapter 2 for more analysis on the interlinkages between FDI and the offshore regime in Tunisia). In 2021, among the group of foreign firms, those in the offshore sector employed 95% of workers while representing 79% of the group, in stark contrast with Tunisian offshore firms that employed 22% of workers in Tunisian companies (Figure 3.4).Offshore companies play a critical role in shaping labour market outcomes in Tunisia, accounting for almost 40% of total private sector employment in 2021, although they represent only 4% of all firms. This discrepancy highlights the significant interlinkages and potential dependencies created by the offshore regime between trade, investment and employment outcomes in Tunisia. The large concentration of employment in offshore companies, makes jobs more vulnerable to global trade and economic turbulences.

Figure 3.4. Job creation by foreign companies create occurs mostly under the offshore regime

Share of employment in Tunisian and foreign firms by type of company, 2021

3.3.2. FDI-related job creation strongly varies across sectors and regions

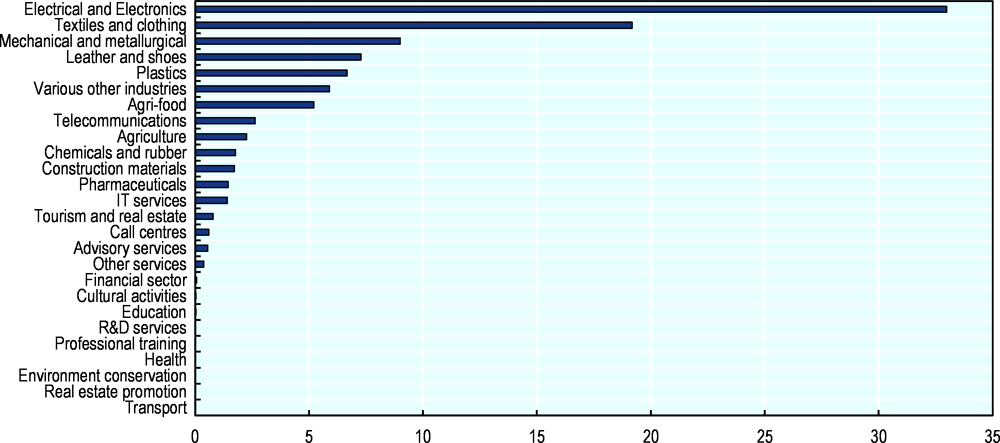

Over the past decade, there has been a large concentration of jobs created from FDI in manufacturing. Out of all the new jobs created from FDI between 2013 and 2022, and excluding the energy sector, over 90% were in manufacturing and 6.5% in services. The opposite holds for Tunisian firms. Moreover, two manufacturing sectors – electronics and textiles and clothing – created half of all jobs (Figure 3.5). One third of jobs created from FDI during that period was in electronics alone. This reflects the changing sectoral distribution of FDI in Tunisia and a shift to more labour-intensive manufacturing activities.

Figure 3.5. The distribution of jobs created from FDI in Tunisia by sector

Share of jobs created from FDI as a % of total jobs created (excluding energy), 2013-2022

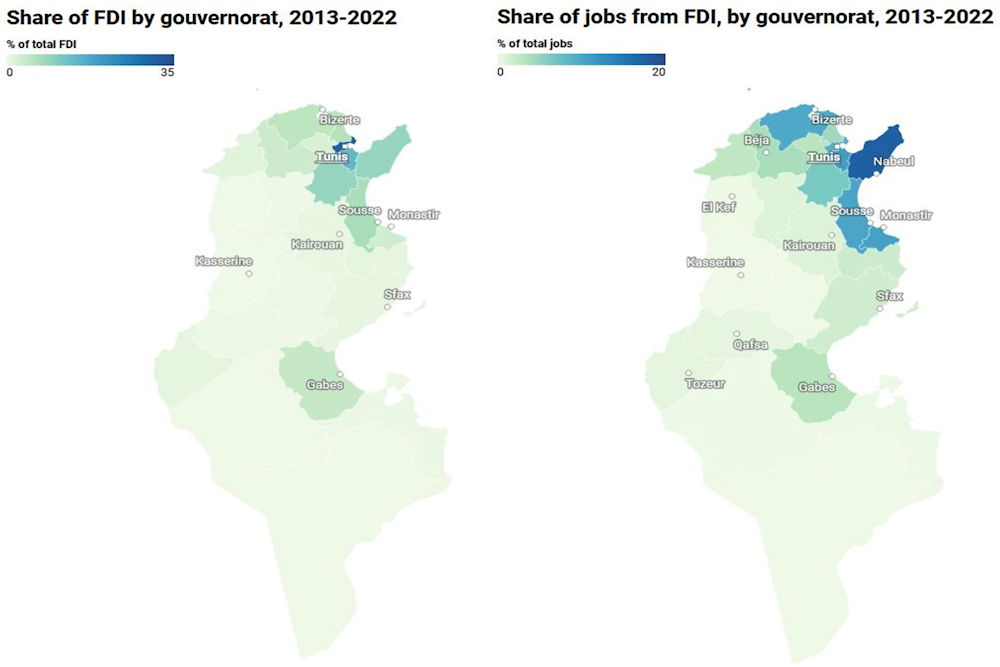

The benefits of FDI in terms of employment are not shared equally across regions and reflect the large regional disparities in foreign investment, as is the case in other countries (OECD, 2022[17]). However, these benefits are geographically more evenly distributed than FDI itself. The Tunis governorate attracted 31% of FDI flows between 2013 and 2022 and the metropolitan area of Tunis – the Grand Tunis – more than half of FDI flows (Figure 3.6, Panel A). At the same time, the share of jobs created from FDI was 9% in Tunis governorate and 28% in the Grand Tunis (Figure 3.6, Panel B). Foreign projects in the agglomeration of Tunis are more geared towards services and, in turn, less labour-intensive than in regions with stronger manufacturing activity. Most foreign companies are located in the Grand Tunis region and this could have had positive spillovers for job creation in the neighbouring regions. Previous studies on Tunisia have found evidence of agglomeration effects where FDI inflows in one region create some positive spillovers in nearby regions (Bouzid and Toumi, 2020[18]). However, it is not the southern governorates, where unemployment is highest, that have benefited the most from FDI. The coastal Northeast and Centre East regions accounted respectively for 34% and 25% of jobs created from FDI between 2013 and 2022. Access to ports and a good road network have proved essential to attract job-creating, export-oriented, manufacturing FDI in Tunisia’s textiles and automotive sectors.

Figure 3.6. Disparity in job creation from FDI across Tunisian governorates

Share by governorate in the total 2013-2022 FDI stock (excluding energy)

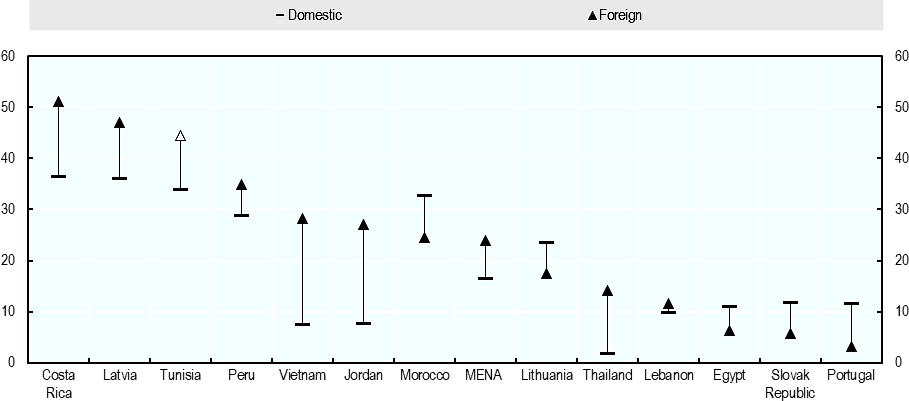

3.3.3. The job creation intensity of greenfield FDI has increased over the past decade

Employment from FDI in Tunisia inherently reflects the scale of foreign investment at the national level and its distribution across sectors. It is also the consequence of the job creation intensity of FDI, which provides an indication of the “value-for-money” impact of FDI on employment in the host country. From a policy perspective, investment promotion agencies, including Tunisia’s FIPA, dedicate ample resources to attracting greenfield FDI with the hope that it creates ample employment (OECD, 2021[8]). In Tunisia, each million USD of greenfield FDI announced between 2003 and 2022 is expected to have created 3.6 direct jobs on average, twice the average of the MENA region and significantly above the OECD average (Figure 3.7). The job creation intensity increased in the past decade with respect to years 2003-2012, as a result of FDI activity shifting away from capital-intensive mining towards labour-intensive manufacturing activities. However, this impact remains lower than in other small open economies such as Costa Rica, Lithuania and Slovakia.

Figure 3.7. Job creation intensity of greenfield FDI in Tunisia and comparator countries

Direct jobs created per mln USD of FDI invested, 2003-2022

Note: Data includes the energy sector.

Source: OECD calculation based on (Financial Times, 2024[19]) fDi Markets Database, https://www.fdimarkets.com.

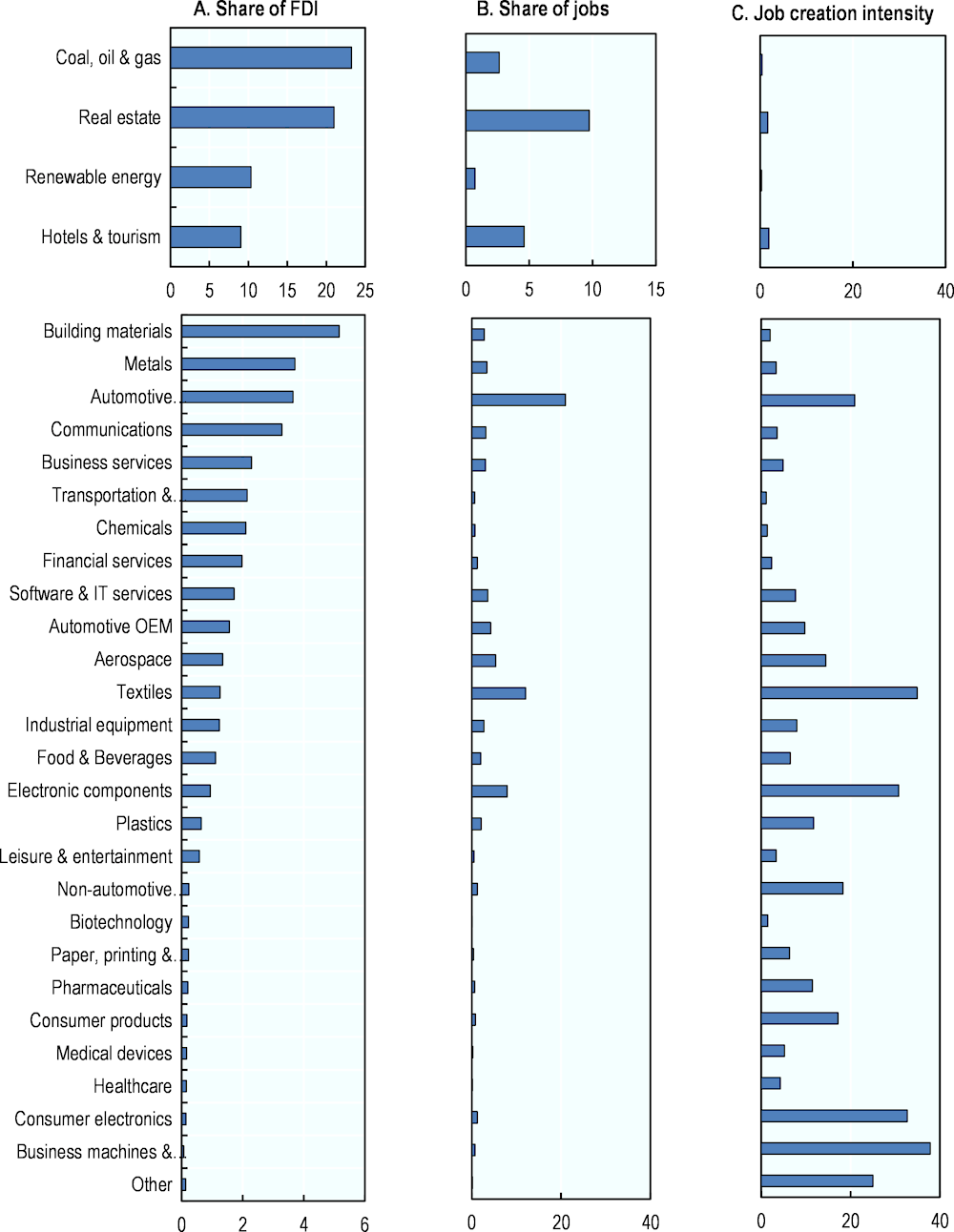

Tunisia’s strong job creation intensity of FDI relies on a few highly labour-intensive activities, indicating that modest changes in the distribution of investment can have large impact on job creation prospects. Over 2013-2022, sectors that attracted the most FDI were not necessarily those where job creation was greatest. The energy sector, which is excluded from FIPA’s statistics, real estate, and hotel and tourism, accounted together for two-thirds of FDI but only 18% of new jobs created from FDI (Figure 3.8, Panel A and B). The textiles and automotive industries created nearly 40% of jobs from FDI despite attracting only 6% of FDI. This illustrates striking differences in the job creation intensity across sectors, which varies from 0.25 jobs per million of USD invested in fossil fuel energy to 38 jobs in the business machines and equipment sector. Greenfield FDI in textiles and electronics created at least 30 new jobs per million USD and has been an important source of employment creation in Tunisia (Figure 3.8, Panel C).

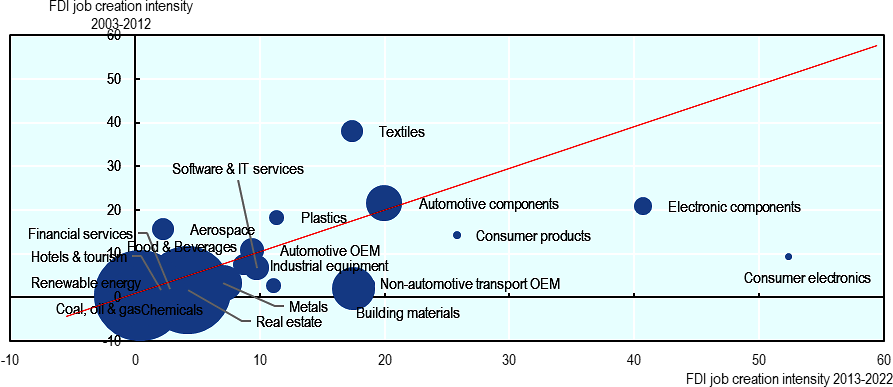

The job creation intensity of greenfield FDI in Tunisia has even increased in the past decade, indicating a structural shift in the composition of foreign investment both across and within sectors, i.e. in the type of activity. Job intensity can increase either through greater labour-intensity of activities within sectors or more FDI going towards labour-intensive sectors. Within sectors, while changes in the job creation intensity of FDI were limited in many sectors attracting big shares of FDI between the periods 2003-2012 and 2013-2022, there has been a shift within the most job-intensive sectors (Figure 3.9). The electronic components and consumer electronics sector were the two sectors with the highest job creation intensity in 2013-2022, each nearly doubling their job creation intensity with respect to the previous decade, suggesting a surge in labour-intensive activities within these sectors. On the other hand, the job creation intensity of the textiles sector was halved, indicating significantly lower labour-intensity as the sector faces increasing competitiveness pressures from other emerging markets (Ministère de l’Industrie, 2022[20]).

Figure 3.8. Contribution of greenfield FDI to job creation in Tunisia

Shares of greenfield FDI and jobs and job creation intensity, 2013-2022

Note: Many of the reported jobs created are estimates, The sectoral composition may differ from figure 3.5 due to differences in sector classification between the databases.

Source: OECD calculation based on (Financial Times, 2024[19]) fDi Markets Database, https://www.fdimarkets.com.

Figure 3.9. Job creation intensity of greenfield FDI changes over time and by sector

Jobs created per mln of USD, 2003-2012 and 2013-2022

Note: The size of the bubble reflects the sector’s share in total FDI during 2003-2022.

Source: OECD calculation based on (Financial Times, 2024[19]) fDi Markets Database, https://www.fdimarkets.com.

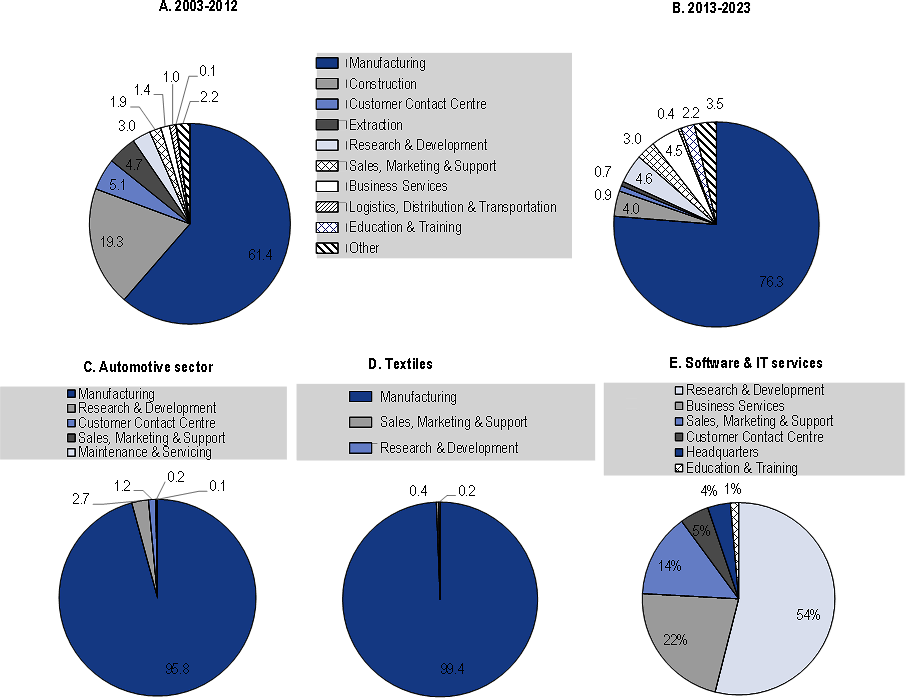

Sectoral shifts in greenfield FDI are interlinked with the changes in the type of activity of FDI projects between 2003-2012 and 2013-2023. While manufacturing and construction activities made up 80% of all FDI-related activities during the two periods, their relative shares changed substantially (Figure 3.10, panels A and B). The importance of construction decreased significantly because of a drop in FDI in the real estate sector, whereas the share of jobs from manufacturing activities increased on the back of a surge in FDI-related job creation in the electronics sector. Manufacturing has also been a key, if not the only, activity in the automotive and textiles sectors (Figure 3.10, panels C and D). This is typical of countries that receive labour-intensive FDI and similar patterns have been observed in peer countries (OECD, 2021[8]). Interestingly, there has been an increased importance of services activities. Business services, R&D, and sales and marketing activities contributed to 12% of new jobs created during 2013-2023, in contrast to 6% in the previous period (Figure 3.10, panels A and B). R&D was prominent in the software & IT services sector, where they contributed to 54% on new jobs created from FDI (Figure 3.10, panel E). At the same time, it was driven by the presence of one very job-intensive FDI project and does not necessarily define a trend in the sector.

Figure 3.10. Share of jobs created from greenfield FDI by type of activity

Share of jobs created from greenfield FDI, by type of activity

Note: Greenfield FDI corresponds to announced capital expenditure (CAPEX). Number of jobs and CAPEX are partly based on estimates.

Source: OECD calculations based on (Financial Times, 2024[19]) FDI Markets database, https://www.fdimarkets.com.

3.4. The contribution of FDI to job quality and gender outcomes

Beyond job creation, FDI influences wage and non-wage working conditions, including job stability, safety, and employment conditions, as well as gender outcomes on the labour market (OECD, 2022[21]). Foreign firms also influence employer-worker relations. As an adherent to the OECD Guidelines on Multinational Enterprises, Tunisian authorities are required to promote the Guidelines and perform related due diligence. The Guidelines provide several clauses related to workers’ rights, industrial relations and ensuring workers’ safety (Box 3.1). Overall, labour market institutions are crucial to ensure that FDI does not contribute to deteriorating working conditions. Collective bargaining and workers’ voice arrangements can particularly help ensure that workers benefit from FDI by supporting collective solutions to emerging issues and conflicts (OECD, 2022[21]). This section focuses the contribution of FDI to wage and gender outcomes.

Box 3.1. OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises: Employment and Industrial Relations

MNEs should, within the framework of applicable law, regulations and prevailing labour relations and employment practices and applicable international labour standards:

Respect the right of workers employed by the MNE to establish or join trade unions and representative organisations of their own choosing.

Observe standards of employment and industrial relations not less favourable than those observed by comparable employers in the host country. Where comparable employers may not exist, provide the best possible wages and conditions of work, within the framework of government policies.

To the greatest extent practicable, employ local workers and provide training, in co‑operation with worker representatives and, where appropriate, relevant governmental authorities.

Take adequate steps to ensure occupational health and safety in their operations.

In considering changes in their operations which would have major employment effects, provide reasonable notice of such changes to representatives of the workers, and, where appropriate, to the relevant governmental authorities, and co‑operate to mitigate practicable adverse effects.

In the context of bona fide negotiations with workers’ representatives on conditions of employment, or while workers are exercising a right to organise, not threaten to transfer activity in order to influence unfairly those negotiations or to hinder the exercise of a right to organise.

The Guidance sets out practical ways to help businesses avoid potential negative impacts of their activities and their supply chains. It aims to bolster policy efforts to strengthen confidence between enterprises and the societies in which they operate, and complements both the due diligence recommendations contained in the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and the ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work.

Source: OECD (2023[22]), OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises on Responsible Business Conduct, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/81f92357-en.

3.4.1. Foreign firms pay increasingly higher wages than Tunisian firms in the services sector

The economic performance of Tunisia in the past two decades has not gone hand in hand with strong improvements in wages which is key for lifting living standards. Despite nominal wages growing at an average rate of over 5% since 2000, average earnings in Tunisia are well below those of peer OECD and non-OECD countries (Figure 3.11, panel A). The monthly minimum wage in the non-agricultural sectors (Salaire minimum interprofessionnel garanti) was 390 Tunisian dinars (around 125 dollars) in 2022; a low level by international standards. Wages vary across sectors, with the highest earnings observed in finance, mining, and ICT services, which is due to the higher value added and higher productivity of these sectors (see Chapter 2) (Figure 3.11, panel B). Earnings in the manufacturing sector are below the national average, as jobs in the manufacturing sector in Tunisia usually require only basic skills. Competitive wages, combined with a growing labour market and proximity to European markets, have been important factors for FDI attractiveness in Tunisia.

Figure 3.11. Wages in Tunisia are low compared to those of peer countries

Increased FDI to Tunisia has contributed to improved working conditions, notably through higher wages, although the benefits have varied across sectors and may not have been felt by all segments of the population. The positive impacts of FDI might not materialise if for example foreign firms engage in irresponsible business practices or attract skilled workers away from domestic firms (OECD, 2022[21]). As foreign companies are often larger and more productive, they typically offer better wages, but the extent to which this outcome materialises largely depends on the sector where firms operate (OECD, 2019[24]). For example, firms operating in low-value added manufacturing sectors that rely on low-skilled workers have less of a margin for providing better wages than firms in high-tech manufacturing industries. Yet, excessive wage dispersions between foreign and domestic firms can also lead to increased wage inequalities. As Tunisia heavily attracts FDI in low value-added manufacturing sectors or activities, the economy-wide impact has been limited.

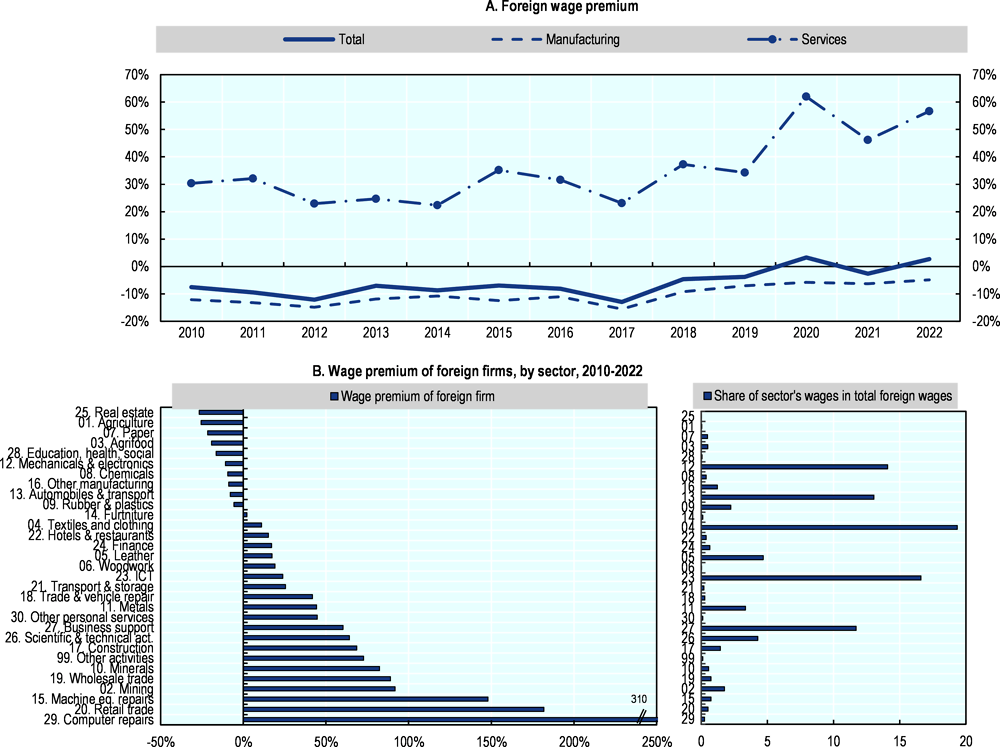

The foreign wage premium, which measures average wages per worker in foreign companies relative to domestic ones, has increased since 2010, albeit from negative levels. Average wages in foreign firms had been lower in the past, but increases in recent years led to the wage premium turning positive in 2020 (Figure 3.12, Panel A). In 2022, wages in foreign firms were on average 3% higher than in Tunisian firms, but a large discrepancy exists between wages in manufacturing and services sectors. In particular, the services sector experienced a significant increase after 2017, with the foreign wage premium doubling between 2010 and 2022, driven by increasing foreign wage premia in business services, professional and scientific activities and the computer repairs sector. In 2022, foreign firms paid almost 60% higher wages than domestic firms in services.

Services sectors where foreign firms paid higher wages than Tunisian firms include repair of computers and machines, and wholesale and retail trade (Figure 3.12, Panel B). In these sectors, foreign firms offered wages that were at least twice as high as those of Tunisian firms throughout the period 2010-2022. Repair of computers was the sector with the highest foreign wage premium of 310% but, at the same time, where only 1% of all companies are foreign. It suggests that there are a few large foreign companies that pay high wages, whereas many domestic firms are probably small micro firms with relatively low wages. Furthermore, foreign firms exhibit positive wage premia in two services sectors where they are strongly present – ICT services and business support services, which together account for almost a third of the total foreign wage bill and contributed to the rapid increase in the foreign wage premium in services. These sectors tend to be more skill-intensive. In turn, the foreign wage premium may partly reflect a skill premium.

In the manufacturing sector, despite slight increases in recent years, wages in foreign companies were, on average, lower than in Tunisian firms (Figure 3.12, Panel A). Some key sectors display a negative foreign wage premium, including food and beverages, chemicals and pharmaceuticals, automotive equipment, and mechanical and electronics (Figure 3.12, Panel B). Foreign firms may be motivated to invest in Tunisia’s manufacturing sectors due to comparatively low labour costs and hence would not have the incentive or margin to improve the wage conditions of their workers. It is also a reflection of the relatively lower labour productivity of foreign firms in the manufacturing sectors in Tunisia vis-à-vis domestic firms, such as in automobiles and electronics (see Chapter 2). At the same time, mining, metals, and machine equipment repair had strong foreign wage premia in 2022, reflecting the higher value-added of activities in these sectors. Nevertheless, these sectors account for a small share of the activity of foreign firms and contributed little to the overall wage premium. The significant differences in foreign wage premia across sectors, might suggest the cost-competitiveness motivation of foreign firms to invest in a particular sector.

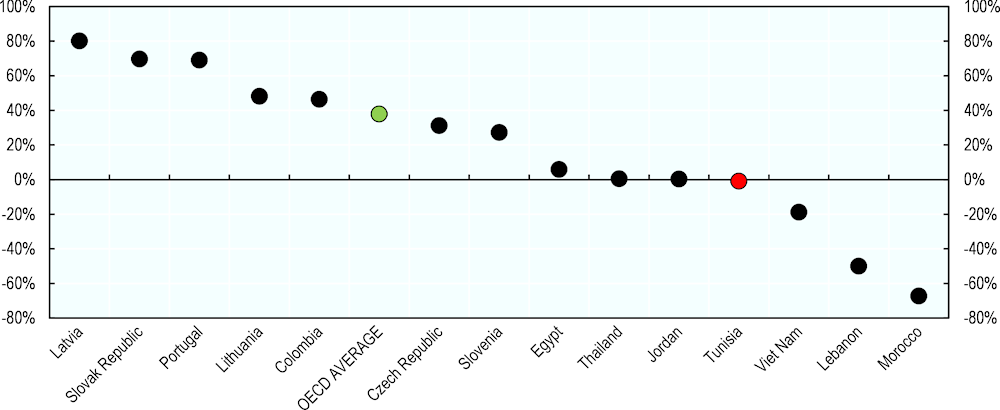

The foreign wage premium in Tunisia is low in comparison with the OECD average and some peer economies. Comparable data across selected countries, which covers primarily the manufacturing industry, shows that, in many countries, foreign firms pay higher wages than domestic ones, resulting in a positive foreign wage premium in these countries (Figure 3.13). However, in Tunisia the foreign wage premium was at around 0, while in OECD countries wages in foreign firms in the manufacturing sector are on average 40% higher than in domestic ones. This indicator varies slightly from the indicators in Figure 3.12, because of differences in sector coverages across the databases. It reflects the fact that foreign firms in Tunisia, like in Jordan or Thailand, are not significantly more productive than domestic firms or may be concentrated in sectors with more competitive labour costs.

Figure 3.12. Wage premium of foreign firms in Tunisia across sectors

Wage premium of foreign firms by sector, average wages for 2010-2022

Note: Panel A excludes agriculture, construction, and the trade sectors where informal employment is most prevalent.

Source: OECD calculations based on (INS, 2023[14]), the Répertoire National des Entreprises (RNE) sample.

Figure 3.13. Average wage premium of foreign firms

Foreign firms pay higher wages if index >0, 2020 or latest year available

Note: The World Bank Enterprise Survey for Tunisia and other economies is based on a sample of firms and includes primarily manufacturing sectors, with a strong representation of food and beverages, and textile and clothing industry.

Source: OECD calculations based on (World Bank, 2024[25]), World Bank Enterprise Survey.

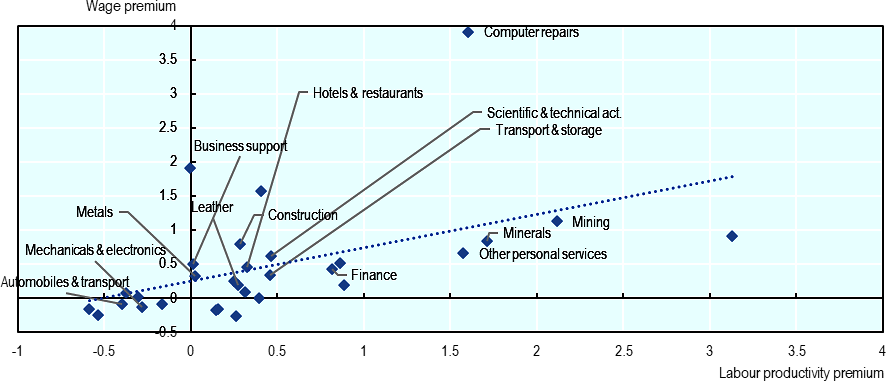

3.4.2. Foreign firms pay higher wages in sectors where they are more productive

Despite different trends of foreign labour productivity (Chapter 2) and wage premia, there is a positive correlation between premia at the sector level. Taking average premia for 2010-2022, sectors with higher labour productivity premia are more likely to offer higher wage premia, but the relationship is not proportional (Figure 3.14). It shows that improvements in labour productivity are an important catalyst for better wage benefits for workers, as foreign firms are usually larger, more technologically advanced, and hire more skilled workers (OECD, 2019[26]). In a sector with foreign firms are twice as productive as domestic ones, those firms pay 70% higher wages on average. Sectors where this relationship is the most prominent include financial services, mining, minerals and metals, scientific and technical activities, and other personal services. At the same time, there are notable exceptions – for example, in retail trade, there is no foreign labour productivity premium while foreign firms pay 200% more on average. Conversely, while foreign firms in wholesale trade are three times as productive as domestic ones on average, this translates to 90% higher wages. Nevertheless, as shown before, numbers in these sectors are likely to display anomalies and must be interpreted with caution.

Figure 3.14. The foreign wage premium is positively correlated with labour productivity premium

Average of 2010-2022 by sector

Note: The dotted line represents the linear trend.

Source: OECD calculations based on (INS, 2023[14]), the Répertoire National des Entreprises (RNE) sample.

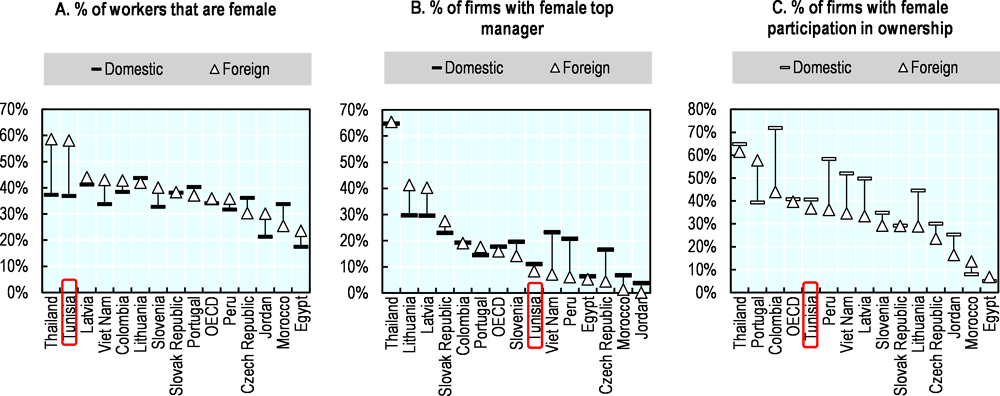

3.4.3. Foreign firms employ more women than Tunisian firms but not in managerial positions

FDI can also contribute to improvements in labour market outcomes through increased female labour participation, which could be important in countries like Tunisia where female labour participation is relatively low. Tunisian women are employed throughout all sectors of the economy, but there is a strong tendency for them to work in agriculture, public services, as well as textiles and electric and electronic industries (Boughzala, 2019[2]) – two manufacturing sectors with a strong presence of foreign firms. Female employment in manufacturing sectors is relatively high in Tunisia compared to peer MENA and OECD countries and is even higher among foreign firms; albeit the jobs are often in low-skilled occupations (Figure 3.15, panel A). Women make up 58% of workers in foreign firms on average, in contrast to 37% in domestic firms, as FDI in Tunisia is increasingly directed at sectors where female employment has been traditionally higher. On the other hand, domestic firms are more concentrated in the services sectors such as retail and transport, where male employment is more prevalent (Boughzala, 2019[2])).

Despite the high share of female employees, women rarely reach top managerial positions in Tunisia, like in other MENA countries. Only 10% of firms have a female top manager, with the share slightly higher in domestic firms (Figure 3.15, panel B). Results vary across countries, with the share of firms having female managers varying from 2% in Jordan to 65% in Thailand. In Tunisia, there still seems to be a glass ceiling for female promotion that is also present in foreign firms. Nevertheless, it is more common for women to participate in the firm’s ownership. Female participation in ownership is a characteristic in 40% of domestic firms and 36% of foreign firms, similarly to the OECD average and much higher than in other MENA countries (Figure 3.15, panel C).

Figure 3.15. Foreign firms’ contribution to gender outcomes is limited

Percentage, 2020 or latest year available

Source: OECD calculations based on (World Bank, 2024[25]), World Bank Enterprise Survey, https://www.enterprisesurveys.org/en/data.

3.5. The contribution of FDI to skills development

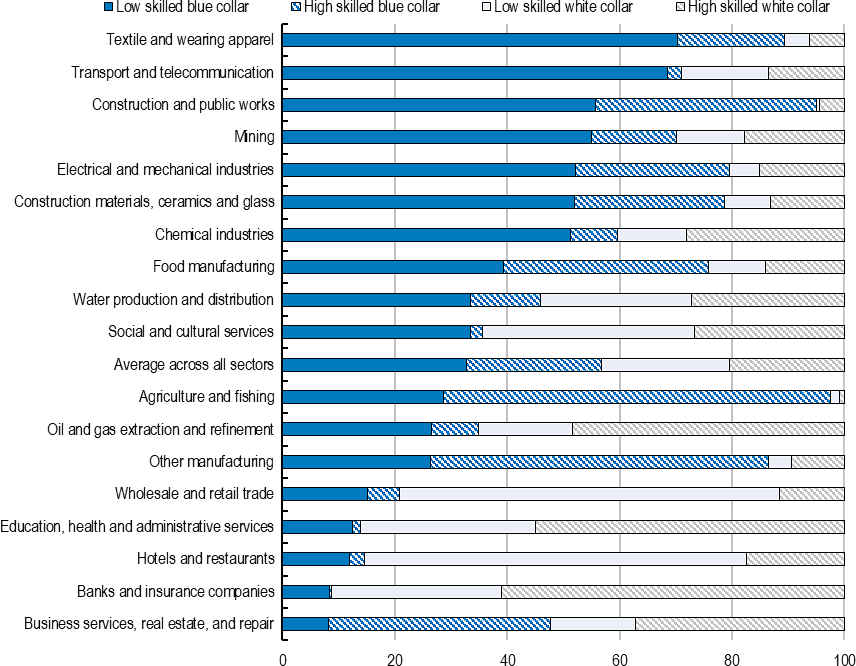

3.5.1. Tunisian workforce is mainly employed in low-skilled jobs

Despite a diversified economy, most of the jobs in Tunisia are in low-productivity sectors and predominantly low-skilled occupations. In part, this is a consequence of past economic policies to attract low value-added activities based on competitive labour costs such as textiles, electronics, retail, and construction (OECD, 2022[3]). In these sectors, which accounted for 43% of private employment in 2022, the share of low-skilled employment (both blue and white collar) ranged from almost 60% to over 80% (Figure 3.16). In very few sectors, the share of skilled workers exceeded 50%. They include the education, health and public administration sectors which attracts the majority of Tunisian university graduates and has been an important driver of skilled employment growth. The banking and insurance sector as well as business services are the other main sources of high-skilled employment, representing 10% of private employment.

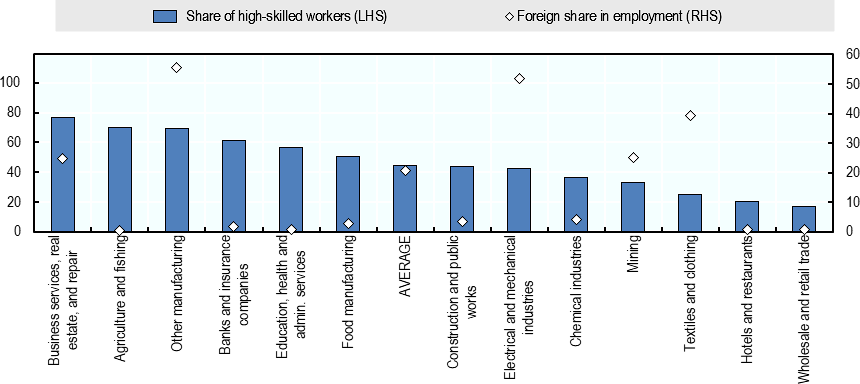

Figure 3.16. Skills composition of employment in Tunisia

Share of workers by occupation category and by activity, 2017 (in %)

Note: According to the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO 08) low-skilled blue collar workers comprise plant and machine operators and assemblers and elementary occupations. High-skilled blue collar workers include skilled agricultural and fishery workers and craft and related trades workers, whereas low-skilled white collar workers include clerks and service workers and shop and market sales workers. High-skilled white collar workers include legislators, senior officials and managers, professionals as well as technicians and associate professionals.

Source: (OECD, 2022[3]) based on Labour Force Survey of the National Institute of Statistics.

Lower-skilled labour is higher in sectors creating most of the FDI-related jobs. The textile and leather and the electric-electronic sectors account together for 60% of all the new jobs created from FDI during 2013-2022 and half of employment in foreign companies in 2022, but as low-value added industries, they are dominated by low-skilled blue-collar employees (Figure 3.17). Much of the activities in these sectors is based on assembling jobs that require basic skills. Similarly in the mining sector, where one in four firms is foreign, 67% of jobs are low-skilled. The skill-intensive financial services sector, while attracting 10% of FDI during the period 2013-2022, was not an engine of employment growth, as it contributed to less than 1% of new jobs created from FDI (Figure 3.5). There is scope for skills spillovers in the business services sector – another important sector for high-skilled jobs, as one fourth of firms in this sector are foreign. Furthermore, as FDI has been increasingly concentrated in higher-value activities, it has the potential to improve mid- or high-skills demand in some sectors, particularly in electronics.

Figure 3.17. Foreign employment is concentrated in sectors with predominantly low skills

Share of high-skilled workers and foreign share in employment by sector

Note: The share of high-skilled workers includes blue collar and white collar workers (see fig. 3.16).

Source: OECD calculations based on (INS, 2023[14]), the Répertoire National des Entreprises (RNE); and (OECD, 2022[3]).

The domination of low-skilled job offers together with high annual numbers of graduates results in skills mismatches on the Tunisian labour market. Skills mismatches occur when workers struggle to find employees with the right skills while job seekers do not find employment that meet their level of qualifications or education. This may be either because companies require advanced skills that are insufficient among workers or on the contrary, potential job seekers are overqualified for the type of jobs that are available on the market. The mismatches not only lead to higher unemployment and lower job satisfaction, but the inefficient allocation of labour is also associated with lower labour productivity (Adalet McGowan and Andrews, 2015[27]).

In Tunisia, the problem of an overqualified workforce is more common than in other MENA countries, resulting in unfilled vacancies despite high youth unemployment (OECD, 2022[28]). Over-education on the job is strongly correlated with age in Tunisia, with the youngest workers being the most affected (Kthiri, 2019[4]). Despite a rapid growth of the educated workforce, especially women, there has been limited employment creation for this group. During the period 2011-2017, the total number of university graduates exceeded by 25% the total employment creation during that period and was six times higher than new jobs in high-end occupations (World Bank, 2022[5]). In view of the lack of opportunities, many young people prefer to stay unemployed and wait for a well-paid and stable government job, emigrate abroad, or even exit the labour market, as is more often the case of women (Boughzala, 2019[2]). In addition, limited labour mobility from more deprived regions to those with more employment opportunities, further contributes to mismatches on the labour market.

As a result of the structural skills imbalances, many more companies in Tunisia than in other MENA and comparable countries are finding it difficult to hire adequately educated workers. Almost 40% of companies identify inadequately skilled workforce as a major constraint (against the MENA average of 20%), with the problem being even more pronounced in foreign firms (Figure 3.18). As many as 44% of foreign companies perceive an inadequately skilled workforce to be a major constraint, in contrast to 34% of domestic firms. Moreover, this share has increased in the past decade, from 34% for foreign firms and 28% for domestic firms in 2013 (World Bank, 2024[25]). Sectors where employers are most likely to have difficulties finding adequately qualified labour include the textiles and leather sector, construction and hotels, and ICT sector, where there is also a high share of foreign firms (ITCEQ, 2018[29]). While skills mismatches are the primary reason for recruitment constraints in Tunisia, other factors identified by firms in Tunisia include high salary expectations and geographical distances (Boughzala, 2019[2]).

Figure 3.18. Firms identifying an inadequately educated workforce as a major constraint

Percentage, 2020 or most recent year available

Source: OECD calculations based on (World Bank, 2024[25]), World Bank Enterprise Survey, https://www.enterprisesurveys.org/en/data.

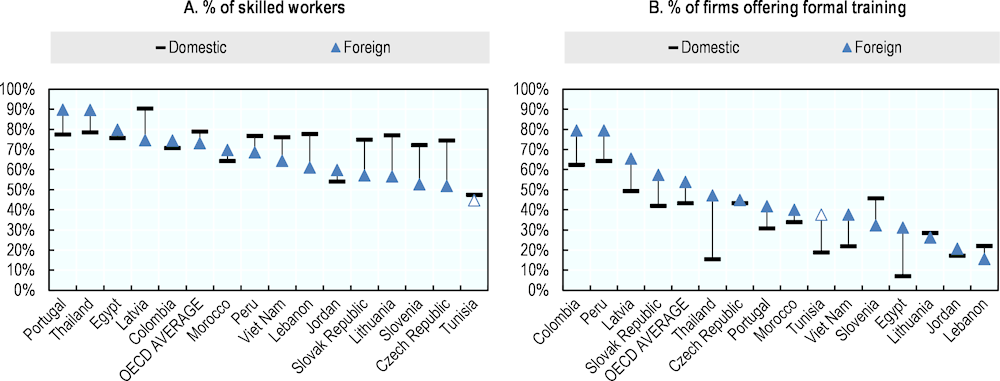

FDI can be an important channel for skills development even if most jobs are concentrated in low-skilled sectors. Foreign firms may contribute to increasing the overall skills supply as they are typically more likely to offer skilled jobs and on-the-job training compared to their domestic counterparts (OECD, 2019[26]). In Tunisia, the employment of skilled workers is relatively low, with only 50% of employers (domestic and foreign equally) hiring skilled workers, in contrast with 76% in the OECD and 73% in the MENA economies (Figure 3.19, panel A). Nevertheless, FDI in less skills-intensive sectors can still bring benefits if firms offer skills upgrading to its workers which improve the overall skills intensity of the workforce. This is the case of Tunisia where foreign firms are twice as likely to offer training to its employees, with 38% of foreign companies providing formal training versus 19% of domestic ones (Figure 3.19, panel B). While this rate is lower than that observed in comparable OECD countries, much more foreign firms in Tunisia provide training than in other MENA economies.

Figure 3.19. Firms hiring skilled workers and offering training

Percentage, 2020 or latest year available

Source: OECD calculations based on (World Bank, 2024[25]), World Bank Enterprise Survey, https://www.enterprisesurveys.org/en/data

References

[27] Adalet McGowan, M. and D. Andrews (2015), “Labour Market Mismatch and Labour Productivity: Evidence from PIAAC Data”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1209, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5js1pzx1r2kb-en.

[9] Belgacem, A. and J. Vacher (2023), “Why Is Tunisia’s Unemployment So High? Evidence From Policy Factors Approved by Amine Mati”, IMF Working Paper No. 2023/219, https://ssrn.com/abstract=4619837 (accessed on 6 January 2024).

[2] Boughzala, M. (2019), MARCHÉ DU TRAVAIL, DYNAMIQUE DES COMPÉTENCES ET POLITIQUES D’EMPLOI EN TUNISIE, European Training Foundation, https://www.etf.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2019-08/labour_market_tunisia_fr.pdf (accessed on 29 January 2024).

[11] Boughzala, M. and M. Hamdi (2014), “PROMOTING INCLUSIVE GROWTH IN ARAB COUNTRIES RURAL AND REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT AND INEQUALITY IN TUNISIA”, Global Economy & Development, Vol. Working Paper 71.

[18] Bouzid, B. and S. Toumi (2020), The Determinants of Regional Foreign Direct Investment and Its Spatial Dependence Evidence from Tunisia, World Bank Group.

[19] Financial Times (2024), fDi Markets database, https://www.fdimarkets.com.

[16] FIPA (2023), Rapports annuels des IDE.

[6] ILO (2024), Labour Force Statistics, https://ilostat.ilo.org/data/.

[23] ILO (2024), Statistics on wages, https://ilostat.ilo.org/topics/wages/.

[10] INS (2024), Répartition de la population active occupée selon le secteur d’activité, https://ins.tn/statistiques/151.

[14] INS (2023), Répertoire National des Entreprises (RNE) database.

[13] INS (2022), STATISTIQUES ISSUES DU RÉPERTOIRE NATIONAL DES ENTREPRISES - 12 Edition 2022.

[1] INS (2020), Indicateurs sur l’emploi informel 2019, https://ins.tn/publication/indicateurs-sur-lemploi-informel-2019 (accessed on 26 January 2024).

[29] ITCEQ (2018), Climat des affaires et compétitivité des entreprises : Résultats de l’enquête 2016, Institut Tunisien de la Compétitivité et des Etudes Quantitatives, http://www.itceq.tn/files/climat-des-affaires-competitivite/enquete2016-climat-des-affaires-competitivite.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2024).

[4] Kthiri, W. (2019), “Over-education in the Tunisian labour market: Characteristics and determinants”, EMNES Working Paper n.22, http://www.emnes.org (accessed on 20 March 2024).

[20] Ministère de l’Industrie, D. (2022), Stratégie Industrielle et d’Innovation 2035, http://www.tunisieindustrie.gov.tn/si2035/Livrable_7_Rapport_final.pdf.

[7] OECD (2024), Labour Force Statistics, https://stats.oecd.org/.

[15] OECD (2023), Analytical AMNE Database, https://www.oecd.org/sti/ind/analytical-amne-database.htm.

[22] OECD (2023), OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises on Responsible Business Conduct, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/81f92357-en.

[21] OECD (2022), FDI Qualities Policy Toolkit, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/7ba74100-en.

[28] OECD (2022), FDI Qualities Review of Jordan: Strengthening Sustainable Investment, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/736c77d2-en.

[3] OECD (2022), OECD Economic Surveys: Tunisia 2022, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/7f9459cf-en.

[17] OECD (2022), “The geography of foreign investment in OECD member countries: How investment promotion agencies support regional development”, OECD Business and Finance Policy Papers, No. 20, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1f293a25-en.

[8] OECD (2021), Middle East and North Africa Investment Policy Perspectives, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/6d84ee94-en.

[24] OECD (2019), FDI Qualities Indicators: Measuring the sustainable development impact of investment, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/investment/investment-policy/FDI-Qualities-Indicators-Measuring-Sustainable-Development-Impacts.pdf.

[26] OECD (2019), FDI Qualities Indicators: Measuring the sustainable development impacts of investment, https://www.oecd.org/investment/investment-policy/FDI-Qualities-Indicators-Measuring-Sustainable-Development-Impacts.pdf.

[25] World Bank (2024), World Bank Enterprise Surveys, https://www.enterprisesurveys.org/en/enterprisesurveys.

[5] World Bank (2022), Tunisia’s Jobs Landscape, World Bank Group.

[12] World Bank (2014), The Unfinished Revolution: Bringing Opportunity, Good Jobs And Greater Wealth To All Tunisians, World Bank Group, Washington D.C., https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/658461468312323813/the-unfinished-revolution-bringing-opportunity-good-jobs-and-greater-wealth-to-all-tunisians.