This chapter introduces the concept of scale up policy. It first aims to disentangle the notion of SME scale up and high growth, and to identify the drivers of SME scaling up based on relevant literature. Building on lessons learned from the microdata work of the project about the profiles and pathways of scalers, it then discusses policy implications, presents rationale for policy intervention in support of scale-ups, and proposes an analytical framework for better understanding country approaches and policy mixes to unleashing SME potential to scale up. This analytical framework supports a series of thematic reports on scale up policies.

Financing Growth and Turning Data into Business

1. Rethinking SME scale up and growth policies

Abstract

In Brief

SMEs and start-ups that scale up have attracted increasing policy attention for their exceptional performance and contribution to job creation, innovation, growth and competitiveness. Public policies accordingly have tried to focus on those firms with the highest growth potential, often by targeting firms in narrow (tech-related) sectors, and engaging large budgetary support. Yet, the conditions for SME scale up remain poorly understood. There is still a lack of evidence on which firms could effectively become scalers, and there is no clear and comprehensive overview of what policy measures and framework conditions work in promoting scale-ups.

Unleashing SME Potential to Scale Up, a project jointly initiated by the European Commission and the OECD, intends to address existing knowledge gaps through empirical work on scalers’ profiles and trajectories, and analyses of country policy approaches in promoting SME scaling up through an extensive mapping of relevant policy initiatives and institutions in specific fields across the 38 OECD countries.

Firm growth is commonly measured by sales and employment. Firms grow through a range of strategies, including innovation, investment, market expansion or differentiation, as well as competition, cooperation or collusion.

Policies for scaling up often seek to increase the capacity of a firm to operate, in a sustained manner, at a higher level of performance, which eventually expresses itself in high growth. Scale-ups or high growth firms (HGFs) are defined according to Eurostat-OECD recommendations as enterprises with at least ten employees at the beginning of a three-year period that saw average annual growth of over 10%. Future analysis will also adopt a complementary 20% threshold.

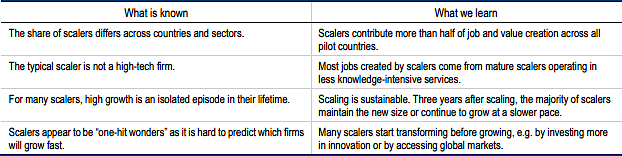

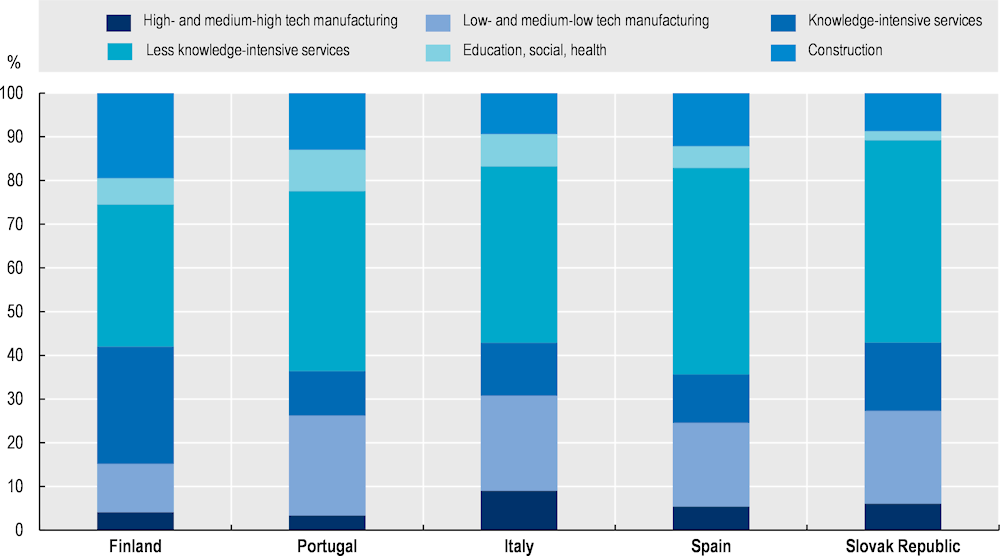

The microdata work, based on five pilot countries (Finland, Italy, Portugal, Slovak Republic and Spain) and literature provide evidence on the characteristics and transformation pathways of scalers, and helps draw a number of policy implications.

1. Scale up is not limited to high-tech start-ups. The typical scaler is neither a knowledge- nor tech-intensive firm. The majority are mature SMEs (six years old and over) operating in low-tech services. In addition, scalers can be found in all places and across all sectors.

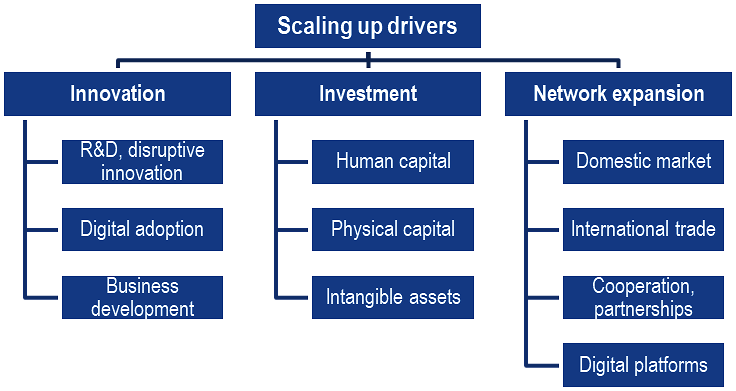

A narrow policy focus on high-tech start-ups is likely to exclude many actual and potential scale-ups, and support may not always be appropriate for those receiving it.

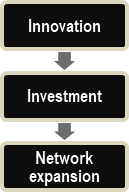

2. Scaling up often involves an inner transformation of the firm. In this context, scalers typically engage in different development trajectories by mobilising and combining – in different ways – three main growth drivers, i.e. i) innovation (including research and development, digital adoption, or business development), ii) investment (including in physical capital, skills or intangible assets), and iii) network expansion (e.g. in domestic or international markets, through cooperation and strategic partnerships, or by using digital platforms). Scaling up drivers are highly interconnected and mutually reinforcing.

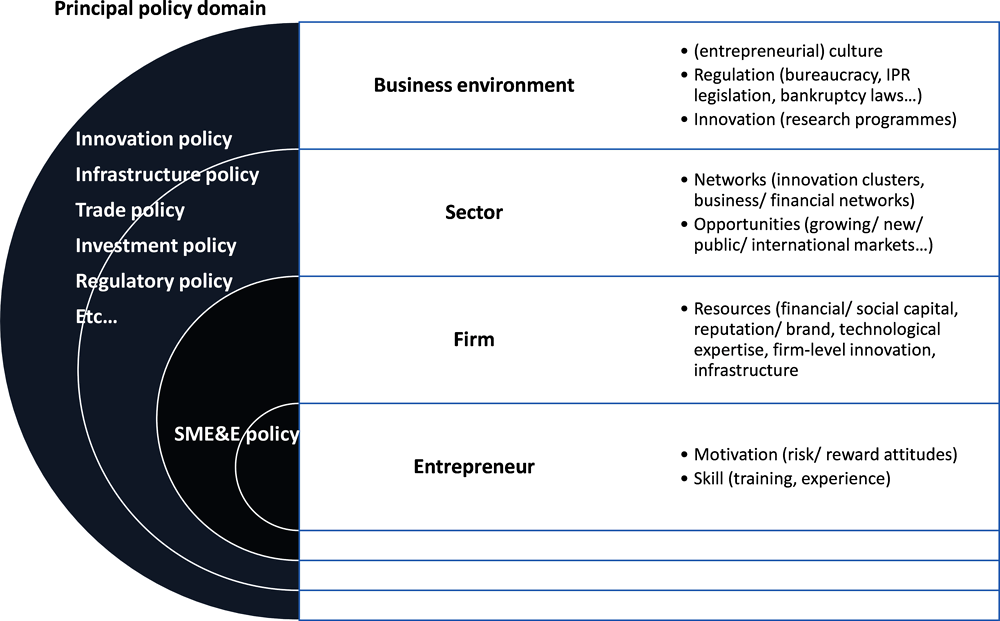

The diversity in SME growth profiles and trajectories requires scale-up policies that are equally diverse. Public intervention can take place at the intersection of a large number of policy domains, i.e. innovation, business R&D, SME digitalisation, entrepreneurship, skills, IPRs, trade, taxation, investment promotion, procurement, competition or cluster policies etc. Examples range from cutting red tape; new regulations on labour markets; promoting the diffusion of tech, non-tech or digital innovation; improving entrepreneurship education; easing access to finance, foreign markets, public procurement or knowledge infrastructure; as well as addressing distortions in competition from excessive market power of large firms etc.

An ecosystem to nurture scalers and a whole-of-government approach are needed. Scale-up policies are cross-cutting by nature, implying that it would not be sufficient for policy to target one single channel of intervention. A holistic approach is therefore needed to stimulate scale-ups, which can range from targeted support (e.g. for finance, skills, and leadership) to developing favourable entrepreneurial ecosystems. They also require policy coordination at and across different levels of government (local, regional, national, and even supra-national).

3. It is difficult to predict which firms are going to grow and target them before their transformation. The decision to innovate, invest, scale up or down depends on a number of market conditions, firm strategy and business owner ambitions, and is also determined by a local, cultural, and industry context that can influence the scaling up process and the willingness of firms to transform.

It is hazardous for policy to seek to pick future winners, and engage large amounts of public resources on these assumptions. There is a danger of little effectiveness and efficiency of policies if they are poorly targeted, especially since there is limited evidence on which targeted approaches can have the most impacts on generating scale-ups.

4. Scalers can maintain new scale over time, and even grow again, which means that most scalers that have undergone this transformation have gained capacity on a permanent basis.

Scale up policies are likely to pay off, although much remains unexplained, and more evidence is needed.

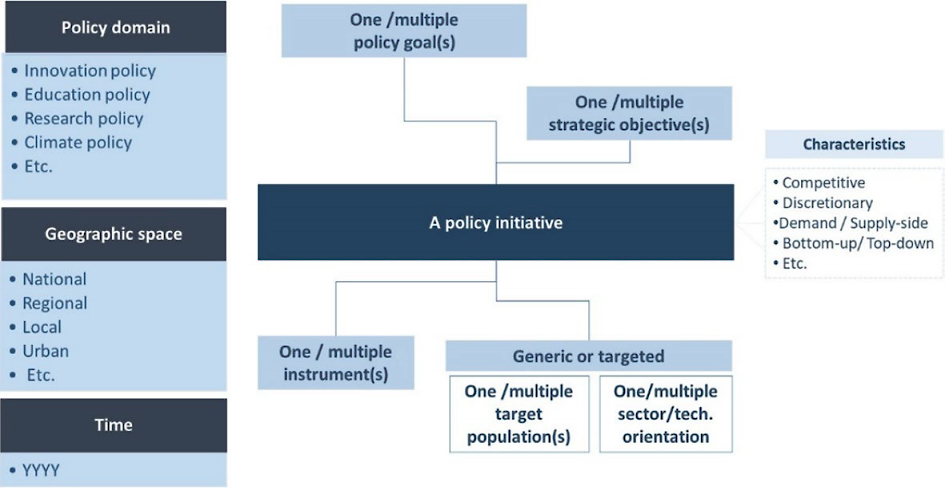

The project interprets scale-up policy as the range of public policy interventions that seek to promote SME scale up through improved conditions and incentives for innovation, growth, investment and network expansion. The scope of the work is intentionally broad, so as to capture the “ecosystem of policies” which shape the conditions and incentives of SME scaling up. The policy mix concept is central to the mapping exercise, which seeks to capture the set of policy rationales, governance arrangements and policy instruments that are mobilised, as well as the interactions that can take place between these elements. This work provides the foundations of a series of future policy reports on SME scaling up.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on economies and societies, but with uneven repercussions across firms, and the more recent war in Ukraine has introduced further and significant uncertainty. High supply constraints, which are expected to worsen, are feeding inflationary pressures. These developments go hand in hand with more structural challenges, already underway before and then speeded by the pandemic, and mainly related to tightening labour markets and new signs of skills shortages, reflecting, among other things, a shift in the required skills mix due to changing consumption patterns, labour force withdrawals, early retirement, or decline in worker migration (OECD, 2021[1]).

In this context, and as governments aim to build resilience and speed the transition towards more sustainable and inclusive growth, fast-growing small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and start-ups are called to play a key role1. High-growth firms (HGFs), also called scalers or scale-ups, have been attracting increasing policy attention for their exceptional performance and disproportionate contribution to value and job creation, as well as to the competitiveness of national and sub-national economies. They also play a significant role in innovation creation and diffusion, helping to generate broader economic and social spillovers, with their development and retention in domestic markets increasingly becoming a strategic policy issue.

Only a very small percentage of firms in OECD countries experience high growth. Between 2016 and 2018, for example, only 7% to 17% of firms with at least 10 employees experienced average annual growth over a three-year period of 10% or more (scale ups) in OECD countries2. Despite their small number, however, scale-ups account for half or more of gross job creation by SMEs in the OECD (OECD, 2021[2]).

Public policies accordingly have tried to focus on those firms with the highest growth potential, e.g. often by targeting them in very narrow (tech-related) sectors. For example, the 2022 work programme of the European Innovation Council provides funding opportunities worth over EUR 1.7 billion for breakthrough innovators to scale up and create new markets. EU Members States also agreed early this year to launch the pan-European Scale-up Initiative, which will provide EUR 10 billion for late-stage tech companies to leverage private funding (EIC, 2022[3]).3

Yet, despite high policy interest and an abundant academic literature, the conditions for, and determinants of, SME growth, and particularly high growth, remain poorly understood. Difficulties stem mainly from the diversity of growth journeys SMEs take during their business lifecycle, including alternate periods of very high growth followed by stagnation or even decline. Adding to the challenge, is the diversity of framework conditions, eco-systems and determinants that influence those journeys. These include market structure and adjustments (e.g. growing demand, new or emerging product markets), changes in competition conditions (e.g. entry costs), changes in regulatory and fiscal frameworks, increasing network effects (e.g. business linkages, increased user base), innovative approaches (e.g. new production or delivery processes) and agglomeration benefits (e.g. spatial concentration of resources) (Sutton, 1998[4]) (Sutton, 1991[5]). A critical additional element that is much more difficult to determine is the growth ambitions of the owner(s). As a result, little internationally comparable evidence is currently available that can help better understand the heterogeneity of firms’ paths and the complex mix of barriers and enablers that create the conditions for firms to grow (OECD, 2021[6]).

Compounding the often narrow focus on hi-tech scale-ups is the almost non-existent attention paid to SMEs whose primary purpose is to deliver societal gains. For many SMEs in the social economy, their primary purpose is not economic. Traditional measures of scaling up that look for example at turnover, or indeed (albeit to a lesser extent) job creation, are therefore not always well adapted to the underlying business models of social economy actors. This means that many of these firms may miss out on policy support that can help them scale up in their provision of societal services (often provided for free). Equally, existing measures of scale-ups may not adequately capture firms, whose business models are driven by other criteria, for example carbon-neutral or organic objectives, meaning, in turn, that analyses of factors that drive observed scale ups may not capture the factors that could help these firms scale up, and deliver on key policy objectives (e.g. inclusive and sustainable growth, where SMEs are playing an increasingly important role. (Koirala, 2019[7]) (OECD, 2021[8]) (OECD, 2021[9]) (OECD, 2023 forthcoming[10]).

This Chapter sets some conceptual bases for understanding scale-up policies and aims to provide the foundations for a series of policy reports on SME scaling up. It forms part of a multi-year project on Unleashing SME potential to scale up, carried out with the support of the European Commission, that intends to better understand the drivers of scaling up and how governments can create the right conditions for potential scalers to succeed. For the purposes of the present work, “scaling up” encompasses the capacity of a firm to operate, in a sustained manner, at a higher level of performance, that could be defined in different terms, and which may express itself in high growth (being in terms of turnover and/or employment).

This Chapter is structured as follows. The first section reflects on the measures of firm growth and performance, and how the concepts are linked to better understand the notions of high growth and scale up. It is mainly based on an academic literature review. The second section combines findings from academic literature with new evidence from the previous microdata work on scalers’ profiles and trajectories, and proposes on that basis a set of SME growth drivers, grouped under three overarching pillars i.e. innovation, investment and network expansion. The third section extrapolates on the policy implications of this work, and the last section proposes an analytical framework to monitor and benchmark how countries effectively promote SME scaling up. This framework serves as a common basis for mapping the policies and institutions involved in different aspects of scale‑up policies across OECD countries, and to understand commonalities and specificities in country approaches. The framework is applied in Chapters 2 and 3 of this report, respectively on SME access to growth finance and SME data governance, and will serve for future policy reports on Unleashing SME potential to scale up (Box 1.1).

Box 1.1. Unleashing SME Potential to Scale Up: a multi-year research project

The OECD project on Unleashing SME Potential to Scale Up is carried out with the support of the European Commission. Its pilot phase (2019‑21) is articulated across two pillars:

A measurement pillar to better understand the internal drivers and barriers to SME high growth, through empirical work based on business microdata (Box 1.2), and

A policy pillar to analyse national policy mixes and approaches to unleash the potential of scalers through a mapping of relevant initiatives and institutions across the 38 OECD countries (Box 1.6).

Findings of the measurement work have informed the present policy work and were published in a summary report (OECD, 2021[2]). Over the pilot phase 2019-21, the policy work has focused on two specific areas identified as relevant on the basis of the measurement results: SME access to ‘scale up’ finance, and SME data governance (access, protection, use) (see Chapters 2 and 3 of this report).

Scaling up is often the result of substantial transformations. Understanding why and how these changes in SMEs capacities and performance occur, and indeed the nature of the changes, and whether they are sustainable, is essential for effective policy design. While at this stage, the work is not normative in terms of identifying effective scale up policies, but rather provides a stocktake of measures implemented by countries in the above two areas, it does recognise the need for more evidence to inform better policies and stresses the importance of addressing the cross-cutting nature of measures that can support SME growth.

Firm size, growth and performance: concepts and definitions

Scalability has often been associated with a firm’s ability to grow rapidly without being hindered by the constraints imposed by its size (Monteiro, 2019[11]).Understanding how SMEs achieve and sustain a new scale of activity and the underlying changes in their performance and capacity is at the core of this project and report.

Firm size and size growth

Turnover and employment

The most often used indicators to measure firm size are sales and employment, although exact definitions and practices may differ across countries (OECD, 2017[12]) (Hauser, 2005[13]). Turnover is the total value of invoices emitted by an enterprise during the period of observation, corresponding to market sales of products or services supplied to third parties. Turnover includes all taxes and charges (e.g., transport and packaging), to the exclusion of value-added tax invoiced (VAT) and financial or extraordinary income. Subsidies from public authorities are also excluded. Employment refers to the total number of persons employed, i.e., who work for the enterprise including working proprietors or unpaid family workers.

Determinants of firm size

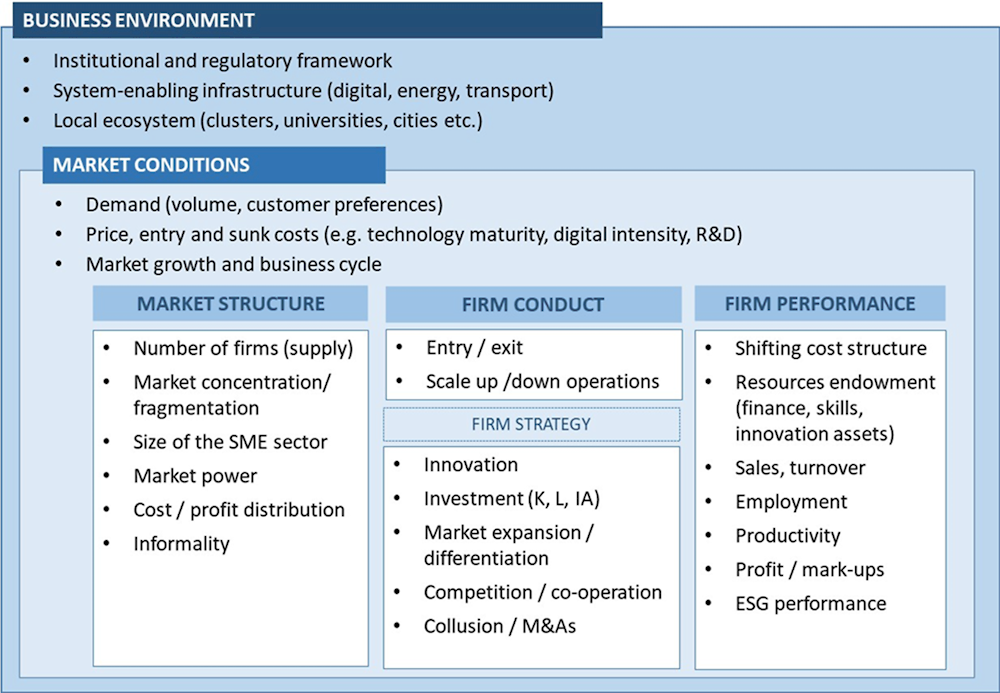

A number of market conditions determine the optimal size a firm should achieve to compete, and the opportunities businesses have to scale up or down operations. The following is adapted from the OECD SME and Entrepreneurship Outlook 2019 (OECD, 2019[14]).

Firms grow to their efficient size as long as they increase economies of scale, i.e., they can reduce average unit cost of production, which eventually determines the efficient scale of production (Figure 1.1). Firms look for an optimum balance between the transaction costs incurred by contracting out and the transaction costs incurred by internalising operations – hence growing through improved competitivity (Coase, 1937[15]).

Firms can also achieve external economies of scale, through market growth or agglomeration. Demand, or market size, set the total volume of output in the industry, and determine the number of active firms operating within the industry at the optimal scale of production (Panzar, 1989[16]). If the market expands, the number of active firms can increase, provided competition conditions support firm entry, or incumbents can grow. Hence, in larger markets, firms tend to be larger. By the same token, the spatial proximity of firms, workers and customers fosters external economies of scale and network effects and helps reduce production costs. These agglomeration economies, together with knowledge spillovers, explain in part the spatial concentration of firms and the increasing attractiveness of urban areas. There are different mechanisms underpinning agglomeration economies. First, when more firms locate in the area, the variety of goods and services increases, and greater specialisation is possible as demand for (specialised) local inputs increases (NB. specialisation is a key driver of SME performance). Second, a larger pool of workers allows SMEs to access a wider spectrum of skills and better fill vacant positions. Third, knowledge spillovers through staff mobility, trade or foreign investments can increase productivity. Combined, this effect can help SMEs reduce costs in accessing resources, infrastructure and markets, and therefore increase their productivity (OECD, 2019[14]).

The sunk costs firms have to incur to enter, or remain competitive in the market, also affect the optimal size they have to reach in order to offset fixed costs. Sunk costs can be related to the industry’s technological maturity, business sophistication or digital intensity, as well as the level of investments in advertising or research and development (R&D) that is required to remain at the frontier. More generally capital-intensive industries, high wage industries, or R&D-intensive industries have larger firms (Kumar, Rajan and Zingales, 2000[17]).

The broader business environment, whether local, national or international, is also an important determinant of the optimal firm size. Stringent taxation and regulation can deter formalisation, firm entry, and firm growth. Poor network infrastructure can increase factor and transaction costs, preventing smaller businesses to scale up operations. The business environment can also change market demand: regulation by opening or closing markets (e.g., certification), transport infrastructure by closing the gap with distant markets, or cities through land planning and agglomeration effects. For instance, countries that have better institutional development, as measured by the judicial system, have larger firms (Kumar, Rajan and Zingales, 2000[17]). In this sense, the business environment also determines the firm’s cost and profit structure, and the firm conduct in reaction (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1. Market structure, firm conduct and performance

Note: For investment, K refers to physical capital, L to skills and IA to intangible assets.

Source: Elaboration based on (OECD, 2019[14]), OECD SME and Entrepreneurship Outlook 2019.

Firms adapt their size to market conditions through a range of strategies, including innovation, investment, market expansion or differentiation, competition or cooperation, and collusion. The efficient firm size, and size evolution, therefore, depends on firm conduct, following a number of -separate or combined- strategies:

In case of the existence of economies of scale/ scope: economies of scale/scope are often technology-based. Firm growth is driven by technology adoption and product/process innovation;

In case of the existence of market transaction costs: firms enlarge up to the point that intrafirm governance costs offset the benefits of vertical integration and reduce efficiency, e.g., to respond quickly to the market. Firm growth can be further driven by organisational innovation to reduce bureaucratic costs. But flexible manufacturing technologies and technical standards, or inter-firm cooperation, can provide an alternative to integration as well;

In case of imperfect competition and market power: dominant firms can fix price or coordinate pricing, especially when products are homogeneous. The entry flow of new firms is insufficient for bringing prices down to average costs, and smaller firms are pushed out of business when oligopolists cut prices. Product differentiation –i.e., product and marketing innovation – enables greater freedom of liberty in price-setting and market competition;

In case of the existence of network effects: network effects increase as the firm increases its user base. Beyond a certain threshold of users (critical mass), the revenues cover the production costs and the unit cost decreases. Unlike economies of scale, the production capacity remains unchanged. Network effects can drive firm growth (in terms of revenues, profit or product portfolio) while the firm size (in terms of number of employees or capital investment) remains unchanged. Network effects are reinforced by the interoperability of systems, standardisation and/or co-operation, as well as the use of intellectual property right (IPRs) that are instrumental to the diffusion of the technology (e.g., software, protocols), brand, design etc.;

In case of the existence of agglomeration benefits: the spatial proximity of firms, workers and customers allows a reduction of production costs through both external economies of scale and network effects. Different mechanisms underpin agglomeration economies, including greater specialisation enabled by a concentration of activities, a larger pool of skills available and productivity spill-overs related to staff mobility, trade or foreign investments.

At the same time, the relationship between market conditions and firms is not one-way. Business strategies can also alter market conditions and, in particular, market structures that reflect the distribution of market power and firm costs, and thereby, the scope for innovating, profit making and growing (OECD, 2019[14]).

Overall, the optimal firm size is the scale of production a business should reach to achieve optimal performance. There is no ideal, especially since there may be trade-offs between different criteria of performance, but an equilibrium size distribution emerges that depends on resource endowment, technology, markets and institutions (Hallberg, 2000[18]). In addition, the firm size distribution evolves over time with changing production terms (factor endowment and economies of scale), disruptive technology and innovation, and changing cost structure, e.g., transportation costs (that can affect the spatial concentration of production and market size) or transaction costs (that can affect business demographics). It comes therefore as no surprise that firm growth is strongly related to performance growth, and often captured through different notions of this performance (i.e. sales, productivity).

Firm performance and performance growth

Firm performance is understood through different lenses that are not mutually exclusive and often prove to be interrelated. High growth, productivity, innovation and exporting have long been considered as indicators of entrepreneurial performance (OECD, 2017[12]). Due to size constraints and more narrow scope for economies of scale, SMEs mainly rely on innovation and product differentiation, and network and agglomeration effects for increasing profit and productivity.

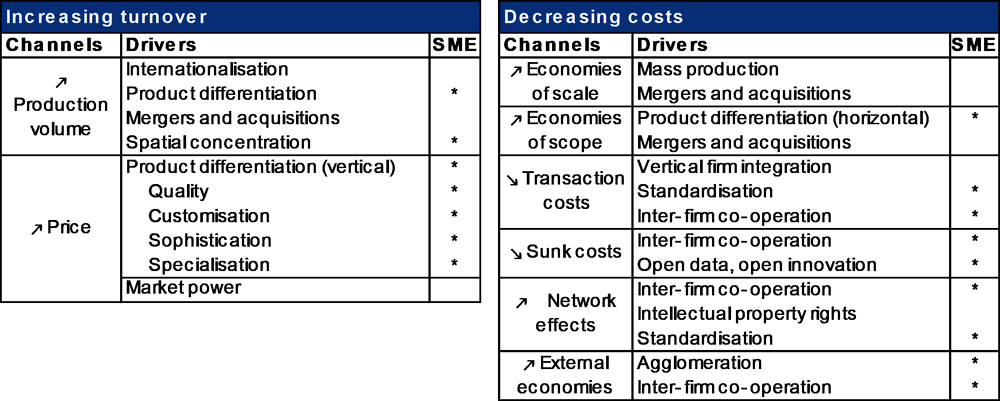

Based on a literature review (OECD, 2019[14]), Figure 1.2 provides a stylised representation of the different channels through which firms can increase profits and productivity, by increasing turnover (i.e. by increasing the volume of production or price) or reducing costs (i.e. by achieving internal or external economies of scale or scope, reducing sunk costs or reaping network effects). Figure 1.2 also identifies those channels that are more accessible to SMEs.

Figure 1.2. Levers of SME profit and productivity growth

Note: This representation does not account for external shocks that can affect firm’s turnover and costs, i.e. due to changes in market demand and supply (e.g. sudden increase in energy and commodities prices in times of war).

Source: Adapted from (OECD, 2019[14]), “Market conditions” in OECD (2019), OECD SME and Entrepreneurship Outlook 2019.

More recently, pressing environmental and societal considerations, changing consumer preferences and new investors’ requirements have prompted business actors to improve their environmental, social and governance (ESG) performance, adopt more responsible business conduct (RBC) and demonstrate greater corporate social responsibility (CSR). As a result, the core notion of firm performance remains market driven, but has become increasingly multifaceted.

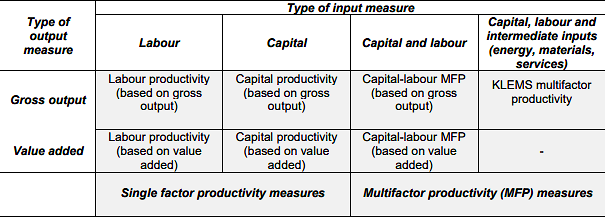

Productivity

Productivity measures the efficiency of production, i.e., the efficiency of resource use. It is commonly defined as a ratio between output volume and input volume, whereas exact measures differ depending on the purpose of measurement and the data available (Table 1.1) (OECD, 2001[19]). The most frequent one is labour productivity as the current price gross value added per person employed.

Table 1.1. Overview of main productivity measures

Source: (OECD, 2001[19]), Measuring Productivity. OECD Manual, https://www.oecd.org/sdd/productivity-stats/2352458.pdf.

Productivity gains come from a number of internal- and external-to-the-firm factors. Internal factors are typically levers on which business owners and managers can act to improve business performance (Marchese et al., 2019[20]). The most often reported ones in the literature are physical capital (i.e. investment in plants, machinery, buildings), skills development, digital adoption and ICT investment, business networks, including through participation in clusters and global supply chains, and innovation, including performing research and development (R&D). External factors refer to market, industry and local conditions (e.g., degree of competition, technology development, economies of agglomeration etc.), which shape firm conduct, especially strategic choices of business owners, and influence productivity growth and diffusion.

Profit, mark-ups, market shares and stock markets

Productivity gains can translate into price competitiveness if the firm can differentiate price on its market. For equal quality, price competitiveness is likely to allow firms to gain market share, i.e., a certain proportion of total output, or total sales, or capacity the firm accounts for in its industry or market.

Productivity gains could also translate into greater cost competitiveness and, all else equal, more profitability. Profit is the surplus earned above the normal return on capital (OECD, 1993[21]). Profits emerge as the excess of total revenue over the opportunity cost of producing the good/service.

Greater profitability can ease access to external finance, either by signalling value to investors or lowering risk perception for lenders, and it can increase self-funding capacity for reinvestment into production, innovation or market expansion activities, which can then create room for new productivity gains. Profitability can also increase the market value of the firm, determined in stock markets that are also often used to assess the long-term profitability of the firm.

There is however considerable controversy as to whether higher levels of profitability reflect the returns to superior efficiency and skills, or the exercise of market power. Mark-ups as measured as a ratio between output price and its marginal cost reflect profit and market power. Mark-ups generally increase with firm size, and firms with the highest levels of market power tend to enjoy larger mark-ups (De Loecker and Eeckhout, 2017[22]) and (Calligaris, Criscuolo and Marcolin, 2018[23])).

Innovation

By innovating, the firm seeks new opportunities and competitive advantage, and aims to generate more profits, through increased sales, greater brand awareness, new customer base or higher market shares (i.e., product innovation), or through greater cost efficiency and improved productivity (i.e., business process innovation) (Crépon, Duguet and Mairesse, 1998[24]). The OECD/Eurostat Oslo Manual defines innovation as: “a new or improved product or process (or combination thereof) that differs significantly from the unit’s previous products or processes and that has been made available to potential users (product) or brought into use by the unit (process)” (OECD/Eurostat, 2018[25]).

The term ‘innovation’ refers to both an activity and the (successful) outcome of this activity. It is an extremely broad concept that encompasses a wide range of diverse activities. R&D, for instance, is one of the activities that can generate innovations, or through which useful knowledge for innovation can be acquired or created. The diffusion of new technology is also central to the process of innovation, and the process of innovation diffusion. In that sense, innovation is at the same time a channel for improving SME performance and a measure of its performance.

Innovations derive from an accumulation of knowledge and information that constitutes the firm’s knowledge-based capital (KBC, also referred to as knowledge-based assets or innovation assets). Innovation requires complementary investments in technology, skills and organisational changes, which in turn require financial, human and knowledge-based capital, and a well-functioning of the markets where those strategic resources could be accessed. Moreover, business ability to invest and take risk, or share knowledge and assets, depends on institutional and regulatory frameworks, quality infrastructure and competition and market conditions (OECD, 2019[14]).

Innovation is therefore a complex and polyform phenomena that remains difficult to measure. In the absence of a composite or synthetic index, proxies of input, output and performance could be used to approximate a firm’s innovation capacity and performance (OECD, 2010[26]). Innovation inputs include R&D and innovation expenditure, adoption rates of new technologies or practices that are considered as productivity-enhancing (digital), acquisition of new machinery and equipment, hiring of highly skilled, investment in intangible assets (e.g., software, data), expansion of networks (use of platforms, establishment of cooperation partnerships, development of supply-chains linkages, etc.). Indicators of innovation output include patenting, licensing revenues, revenues from new product/services etc. Indicators of innovation performance are even rarer, and include gains in market shares, productivity, resource and cost efficiency etc.

Export and internationalisation

SME internationalisation and integration into global value chains (GVCs) could be direct through trade or indirect through supply chains and market mechanisms that involve international actors (OECD, 2018[27]) (OECD, 2021[9]).

Like innovation, internationalisation is both a channel for improving SME performance and a signal of their higher performance, the cause being difficult to dissociate from the consequence. SMEs are less often engaged in international activities but those that are show greater performance (Eurostat, 2018[28]). International SMEs are more profitable and more innovative than their domestic peers; they also have a larger network (St-Pierre, 2003[29]) (Baldegger and Schueffel, 2010[30]). Engaging in international markets can be expensive, a cost that usually only the most productive firms can afford (Melitz, 2003[31]) (Bernard, 2007[32]). For instance, trading costs related to learning about and adjusting to the foreign environment, or addressing increased internal organisational complexity, can weigh disproportionately on SME profitability as smaller firms trade smaller volumes. Participation in GVCs can also require complying with quality standards or obtain certifications that further increase the costs SMEs have to incur upfront and subsequently to adjust to changing conditions. The rise of ESG and RBC requirements ma heighten the relative cost of their internationalisation.

At the same time, integration into GVCs is of particular relevance for SMEs that can expand markets and networks abroad, specialise and compete within niche segments of GVCs that the fragmentation of production globally made accessible to smaller actors, and proceed to capacity upgrading through the exchanges that take place within the value chains (OECD, 2019[14]) (OECD, 2008[33]). Closer global integration has implications for non-exporter SMEs that operate in local markets as well, through increased competition, which can have disruptive effects on local economies and requires enhancing market knowledge and competitiveness of small businesses.

Through trade, SMEs can access cheaper or more sophisticated imported products and services, or technology embodied in imported products (Lopez Gonzalez, 2016[34]) (López González and Jouanjean, 2017[35]). Firms that use more imports are in fact more productive and better able to face the costs of exporting (Bas and Strauss-Kahn, 2015[36]) (Bas and Strauss-Kahn, 2014[37]). Imports and access to markets abroad can also be a way to build resilience through greater supplier redundancy and diversification in sourcing and production locations (OECD, 2023 forthcoming[10]).

Additionally, international investments can have positive spillovers on domestic SMEs (OECD, 2022 forthcoming[38]), (Criscuolo and Timmis, 2017[39]), (Lejarraga et al., 2016[40]) (OECD, 2019[41]) (OECD/UNIDO, 2019[42]). Technology and knowledge spillovers occur through value chain linkages when SMEs serve as local suppliers/buyers of foreign affiliates, through the strategic partnerships they build with foreign investors, through labour mobility, more often when foreign firms’ employees join local SMEs or set up a business locally, or through competition and imitation effects (OECD, 2022 forthcoming[38]). The magnitude of productivity and innovation spillovers depend on the qualities of FDI, the absorptive capacity of local SMEs, and some structural factors such as local economic geography and the policy and institutional framework. A greenfield investment, for example, is likely to involve the implementation of a new technology in the host country and a direct transfer of knowledge from the parent firm to the new affiliate (Farole and Winkler, 2014[43]).

There is therefore a variety of approaches and measures in use to assess SME internationalisation performance. Some focus on export performance, e.g. number of SMEs exporting, export volume and export growth, export profitability and export propensity (i.e. share of exports by SMEs divided by the share of output by SMEs) (Baldegger and Schueffel, 2010[30]) (OECD, 2017[12]). Transactions can be expressed in absolute value or value-added terms to account for re-exporting and multiple cross-border flows (OECD/WTO, 2011[44]). Others focus on SME linkages with foreign multinationals (MNEs) through supply chains (e.g., domestic sourcing of MNEs) and technology cooperation (e.g., licensing from foreign-owned firms) (see (OECD, 2022 forthcoming[38]) for a more comprehensive overview).

Sustainability and resilience performance

SMEs have turned into important drivers of inclusive and green growth with the potential to lead a transition to an eco-friendly, low-carbon economy and simultaneously, steer broad improvements in societal welfare (Koirala, 2019[7]) (OECD, 2021[8]). This reframing is taking place within a broader policy debate on how to better conciliate productivity and inclusiveness (OECD, 2018[45]) (Stiglitz, Fitoussi and Durand, 2018[46]) (OECD, 2019[14]), and to decouple economic growth from resource use and environmental degradation.

SMEs are key actors in building more resilient socio-economic ecosystems and supply chains. The COVID-19 crisis has revealed the vulnerability of GVCs and placed the issue of sovereignty at the forefront of the economic policy debate (OECD, 2021[9]). Resilience arises from supplier diversification and open markets to ensure supply, especially of essential goods. For non-essential goods, it relies on the ability of existing networks of suppliers –most likely SMEs- to bouncing back faster after a shock (OECD, 2021[47]). Instead of switching suppliers and partners and incurring more inherent sunk costs, businesses may entrust relationships within existing networks that have become a key aspect of risk management strategies in supply chains. Promoting responsible business conduct will therefore be critical (OECD, 2021[47]). Throughout the COVID-19 crisis, many companies have been looking to collaborate towards solutions to enhance supply chain resilience, e.g., by supporting their suppliers and business partners with accelerated payments (OECD, 2021[48]). But other reactions have exacerbated supply chain vulnerabilities, e.g., sudden order cancellations that had cascading effects on factory closures, product shortages and job losses.

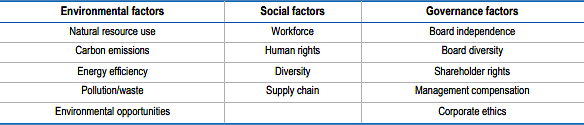

Consequently, SMEs’ performance is increasingly associated with sustainable business practices, from improving resource efficiency, to reducing environmental footprint, to raising ability to comply with ESG requirements and RBC standards (Figure 1.3) (Boffo and Patalano, 2020[49]). Environmental factors can include natural resource use, carbon emissions, energy efficiency, pollution and other sustainability initiatives. Social factors can include workforce related issues (health, diversity, training), and broader societal issues such as human rights, data privacy, and community engagement. Governance factors can include corporate ethics, gender and minorities’ diversity, or enforcing shareholder rights. A poor environmental record may make a firm vulnerable to legal action or regulatory penalties; poor treatment of workers may lead to high absenteeism, lower productivity, and weak client relations; and weak corporate governance can incentivise unethical behaviours related to pay, accounting and disclosure irregularities, and fraud.

Table 1.3. ESG Scoring: key criteria

Source: (Boffo and Patalano, 2020[49]) based on ESG Rating providers, OECD, selected themes for illustration.

One of the key ways in which investors and markets assess ESG performance is through ESG ratings, which they obtain from established ESG raters (Boffo and Patalano, 2020[49]). Among the major market data providers such as Bloomberg or Thomson Reuters, there is a wide range of rating practices in terms of the aspects of sustainability assessed, which data to include, how to weigh metrics etc. Even if ESG methodologies are becoming more robust, and there is more back testing of scores against performance, scoring remains in a state of transition. In fact, the metrics used by companies and data providers suffer from a lack of consistency and uneven transparency, and the correlation among the scores different raters assign to the same companies is low. In addition, the ESG scoring environment is still dominated by large capitalised companies, and SMEs are not yet under scrutiny, which has raised concerns about how small businesses could document their ESG/RBC performance and comply with requirements on markets and within supply chains, or access new sources of sustainable finance (OECD, 2021[9]) (OECD, 2021[8]).

High growth and scale up

SME growth is measured in different ways and different studies have used different criteria, i.e.

The indicator of growth. Growth is most commonly measured in terms of employment (number of employees) or turnover (sales) (Coad et al., 2014[50]). Of these, employment-based metrics are more commonly used as employee headcount is more often available in administrative datasets on enterprises. While both dimensions are likely to evolve in parallel, there is still a possible trade-off, with impacts on firm productivity (see (Monteiro, 2019[11]) and (OECD, 2021[2]) for discussion);

The metric of growth, often formulated as absolute versus relative growth, or a combination of both, as the Birch index (Schreyer, 2000[51]) ;

The period over which growth is measured, which is frequently over three to four years (Coad et al., 2014[50]); and

The process of – organic or internal versus acquired or external – growth (Delmar and Davidsson, 2000[52]).

High growth firms (HGFs) can be defined either as the percentage of enterprises in a population that experience the highest growth performance, e.g. the top 1%-5%-10% with the highest growth rate in a given period (Monteiro, 2019[11]) (Coad et al., 2014[50]) (Petersen and Aḥmad, 2007[53]), or firms that rank first according to a measure that combines relative (percentage) and absolute rates of expansion (Schreyer, 2000[51]), or firms growing at or above a certain rate over a certain period. For instance, (Autio, Sapienza and Almeida[54]) and (Halabisky, Dreessen and Parsley[55]) use sale growth of at least 50% during each of three consecutive financial years.

The Eurostat-OECD Manual on Business Demography Statistics recommends defining high-growth enterprises as enterprises with at least ten employees at the beginning of the period, and over 20% growth per annum averaged over a three-year period (OECD/Eurostat, 2008[56]) (Ahmad, 2006[57]). In the European Union, the Commission implementing regulation (EU) No. 439/2014 sets the definition of high-growth enterprises as follows: “all enterprises with at least 10 employees in the beginning of their growth and having average annualised growth in number of employees greater than 10% per annum, over a three-year period”. Both definitions are used in the literature (OECD, 2017[12]).

In the microdata work of this project, high-growth enterprises are defined as firms with at least 10 employees that grow 10% per year on average in employment and/or turnover over 3 years (Box 1.2), and additional analysis focuses on the higher – 20% per year – growth threshold. Recent trends in digitalisation and globalisation have reinforced the importance to consider (high) growth in both employment and turnover, as firms could reach new scales in turnover terms without growing in employment terms, i.e., scaling up by turnover criteria but not by employment criteria.

Box 1.2. Understanding Firm Growth – a pilot microdata work

Leveraging firm-level data sources from five OECD pilot countries (Finland, Italy, Portugal, Slovak Republic and Spain), the microdata work on Unleashing SME potential to scale up aimed in particular to capture the heterogeneity of scalers, the changes these firms undertake before, during, and after the high-growth phase, and the sustainability of their new scale (OECD, 2021[2]).

In the report, “scalers” are identified through employment- or turnover-based (high) growth, which are taken as a signal of a transformative process at play within the firm. High-growth enterprises are defined as firms with at least 10 employees that grow 10% per year on average in employment and/ or turnover over 3 years.

The work assesses the factors that accompany this growth, i.e., the dimensions through which the firm reached new scales or growth milestones, before, during and after its growth phase, thereby taking also into consideration the capacity of a firm to operate in a sustained manner at a larger scale. To identify the features that distinguish scalers from other firms, the analysis compares them with their “peers”, i.e., firms in the same sector, founded around the same time and of similar size before the scaler enters its high-growth phase.

Source: (OECD, 2021[2]).

The sequencing of high growth and performance increase can differ across different segments of the SME populations. The microdata work of this project has explored the trajectories of HGFs in five pilot countries and the transformations they go through before, during and after a high growth phase (Box 1.2), identifying several factors that enable SMEs to change scale before entering a high growth phase, thus confirming the co-existence of different models and pathways of transformation (OECD, 2021[2]).

Scale ups may not grow in employment and turnover at the same time (at least in the short run) and may not grow in employment at all. Consequently, focusing solely on employment growth would exclude a large share of firms that reach another scale of economic activity without exceptional employment growth (OECD, 2021[2]). Employment and sales growth have in fact been found to be weakly correlated (Wiklund, Patzelt and Shepherd, 2009[58]) and can refer to different types of business transformation, the former pointing towards an increase in resource and the latter towards greater market diffusion (product acceptance). The micro data work shows that only about one-third of turnover HGFs are also employment HGFs at the same time (OECD, 2021[2]). This could be all the most problematic as the use of different growth indicators influence our understanding of who successful scalers are (Coad et al., 2014[50]).

Increasingly, the use of digital technologies leverages the ability of small firms to grow in turnover without employment growth as digitalisation affects market structures and the cost competitiveness of SMEs (OECD, 2019[14]) (OECD, 2021[59]). Different forms of business growth are emerging, with enterprises able to achieve significant scale, market share and high productivity, without needs for more investments or new hiring. For instance, “lean start-ups” are emerging that leverage the Internet to lower fixed costs and outsource many aspects of the business to stay agile and responsive to the market (OECD, 2017[60]). SMEs may also grow without employment growth domestically when they outsource the most labour-intensive activities of production abroad, in countries where labour costs are lower (OECD, 2021[2]).

If for a subset of SMEs (probably the majority) changes in capacity lead to scaling up and high growth, in the case of demand-driven HGFs, growth in size comes without a clear link to any business transformation. The microdata work shows in these latter cases that the SME has no anticipatory strategy, neither shows intrinsic difference with its peers, but instead enjoys and adapts to a sudden windfall in demand (OECD, 2021[2]). Demand-driven scalers might benefit from unexpected market developments leading to a sudden windfall in demand. This can for example be the case of a company producing face masks in the outbreak of a pandemic. To expand production and satisfy increased demand, the firm needs to hire new workers in a short period of time. In such cases, factors driving firm growth might be temporary, which also means that scaling might not be sustainable, and the firm might go back to its initial size.

This raises the question of sustainability in scaling. High growth is a transitory phase. Once a firm reaches a new scale it is likely to maintain it. In particular, scaling up in turnover may be generated via improvements in firm productivity and resource efficiency, which are often targets that firms set for themselves. Profit-seeking firms intend to increase turnover (size) along with other measures of performance, such as stock returns. Most firms are able to at least consolidate their new scale following their high-growth phase (OECD, 2021[2]). About 60% of scale-ups succeed in maintaining their new scale during the three years after their initial high-growth phase and about 20% continue to grow in later stages – albeit with important differences across sectors.

Scaling up drivers: which levers do scalers use?

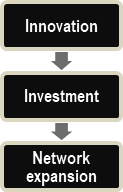

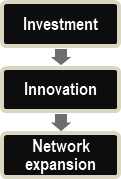

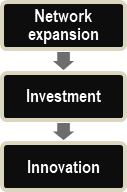

While there is a broad range of factors that could enable and incentivise SMEs and start-ups to scale up4, there is still a lack of certainty – and evidence – on which firms could effectively become a scaler, and in turn which policies are most effective for nurturing them. Building on key findings from a literature review and the microdata work5 of the project, three main SME scaling up drivers have been identified for the purpose of the present report to better understand the characteristics of scalers and the transformation process they go through during a high growth phase. These scale up drivers could be further decomposed into seven sub-drivers (Figure 1.4)

Innovation (including research and development - R&D- and disruptive innovation, digital adoption, or business development),

Investment (including in physical capital, skills or intangible assets), and

Network expansion (e.g. in the domestic market, through internationalisation, or cooperation and strategic partnerships, or through the use of digital platforms)

Figure 1.4. Synthetic overview of SME performance and scaling up drivers

Source: Author’s own elaboration.

SMEs that scale up typically mobilise a combination of these drivers, yet their sequencing might differ, depending on a complex mix of factors related to scalers’ profiles and their overall transformation model. The following sections dig into more detail into the role of each driver and its related sub-dimensions for SME scale up. A last section comments on the multiplier effect of these drivers.

Innovation

Scaling is the result of a forward-looking growth strategy grounded on innovation and productivity improvements (OECD, 2021[2]). At the onset of this transformation is an entrepreneurial mindset and an opportunity-oriented behaviour of business owners, managers, teams and/or individuals to grow a business. Likewise, the measurement part of the project has highlighted innovation as a key differentiating factor between scalers and non-scalers (Table 1.2) (OECD, 2021[2]).

Table 1.2. The central role of innovation in scalers’ transformation models

In particular, the “disruptive innovator” develops new products or processes, either by investing in R&D or other innovation assets, e.g. in digitalisation. This group of scalers is characterised by permanent differences compared to peers that are linked to innovation, such as greater workforce diversity. By contrast, the “gradual innovator” grows through productivity gains and additional market shares. Its growth model is very similar to that of the “disruptive innovator”, but the transformation is more incremental following a process that adds strength to strength in the case of the “gradual scaler”, while it is more sudden following a change that revolutionises firm operations in the case of the “disruptive innovator”.

R&D and disruptive innovation

Scalers are more R&D oriented (OECD, 2021[2]). R&D can generate new knowledge which could bring to the inventor a major competitive advantage, even leading to radical disruptions in markets and behaviours. R&D comprises creative and systematic work undertaken in order to increase the stock of knowledge – including knowledge of humankind, culture and society – and to devise new applications of available knowledge (OECD, 2015[61]). The most R&D-intensive sectors include computer and electronics manufacturing, software development and information and communication services, pharmaceuticals or automotive industries (OECD, 2022[62]). For instance, research on new materials could transform the computer and electronics industry. Flexible “bendable” electronics could enable new applications such as wearables, e-tattoos or potentially low-cost solutions based on direct 3D printing of electronic circuits. The graphene, an electrically conductive, chemically stable and the world’s strongest material, if used in manufacturing logic circuits, could solve the processing speed limitations of silicon transistors, and enable more efficient rechargeable batteries, and better and faster electronics (EC, 2019[63]).

Radical innovations are considered to transform the status quo, while a disruptive innovation takes root in simple applications in a niche market and then diffuses throughout the market, eventually displacing established competitors (Christensen, 1997[64]) (OECD/Eurostat, 2018[25]). Disruptive innovation typically originates in two market segments that incumbents overlook. The first relates to underserved market spaces where incumbents that typically target the most profitable and demanding customers with ever-improving products and services, pay less attention to less-demanding customers, which opens the door to a disrupter for providing low-end customers with a “good enough” product. The second consists in unlocking new-market footholds, where disrupters create a market where none existed. Put simply, they find a way to turn non-consumers into consumers (Christensen, Raynor and McDonald, 2015[65]). Radical and disruptive innovations are likely to be very rare and difficult to identify or measure within the limited observation period recommended for innovation surveys (OECD/Eurostat, 2018[25]).

Digital adoption

Scalers use more dedicated IT resources (OECD, 2021[2]). Digitalisation offers a range of opportunities for SMEs to improve performance, enhance productivity and compete, on a more even footing, with larger firms. Possible benefits have been extensively discussed in the 2021 OECD report on “The Digital Transformation of SMEs”, including: increased economies of scale; lower operation and transaction costs; reduced information asymmetries; greater capacity for product differentiation, business intelligence or automation; increased customer and market outreach; network effects, etc. (OECD, 2021[59]). For instance, SMEs can increase efficiency in their internal processes, gain knowledge about their clients and partners, and better anticipate fluctuations and risks in their business environment, from the adoption and combination of data intensive technologies, such as the Internet of Things and distributed ledger technologies (data generation and exchange), cloud computing (data storage), and artificial intelligence (AI) (data analytics) (Chapter 3).

Business development

Other forms of innovation through the adoption of new processes or practices can support business development and scale up, e.g. in areas like marketing, branding, organisation, or other non-tech areas, which may then translate into increased market share, improved access to new markets, or new products (OECD, 2019[66]) (OECD, 2019[14]). Given that smaller firms have less capacity to carry out in-house R&D due to size-related and resource constraints, incremental and non-technological innovation is more central to many SME business models. Business innovation surveys confirm that SMEs are more often engaged in organisational or marketing innovation than large firms, also reflecting a sectoral bias towards services where SMEs concentrate, and where innovation is in essence less capital- and technology-intensive.

Investments

The measurement work illustrates the importance of –all sorts of- investments for scalers. The “gradual innovator” invests in human and physical capital, and in intangible assets in anticipation of scaling. This type of scaler is characterised by persistent differences compared to peers in human capital (e.g. the share of educated workers and IT specialists). Investments are also particularly central to the model of the “more-of-the-same” scaler that grows without changing production processes (OECD, 2021[2]). This type of scaler is characterised by a higher investment rate and higher debt than peers in anticipation of scaling. This is the economist’s case of “economies of scale”, e.g. a manufacturing firm building a second production line and doubling capacity within the same establishment, or a software company that can increase production without additional costs once the sunk costs of product development are covered. New firms that need to quickly reach a viable scale to survive also fall into this group.

Physical capital

Investing in physical assets can be essential to scale up business operations, depending on the sector an SME is operating in. Physical assets include an extremely broad range of assets, with capital-intensive industries requiring especially machinery and industrial equipment, while service firms typically focus more on vehicles and ICT (OECD, 2015[67]). It was estimated that between 30-70% of the growth of output per worker (productivity) in OECD countries could be accounted for by capital accumulation in the short term, while all gains in the long term were caused by technological progress, often embodied into physical capital (Aghion and Howitt, 2007[68]).

Incidentally, physical capital, used as collateral, can also facilitate access to external funding for expansion, notably debt finance. Innovative companies, young firms and start-ups continue to face particular challenges in this area, although collateral requirements have tended to decline significantly in recent years (OECD, 2022[69]). Likewise, monetising physical assets can open access to alternative asset-based finance. In most cases, physical capital, such as land, inventory, machinery, equipment, and real estate can allow the firm to access working capital under more flexible terms than from conventional lending. That way, asset-based instruments can fill existing SME financing gaps (OECD, 2015[67]).

Skills and human capital

Scalers employ relatively more educated workers (OECD, 2021[2]). Skilled workers are a key asset for competition in a knowledge-based economy (Autor, 2013[70]) (Grundke et al., 2017[71]) and skills development has become critical in a context of a fast and irreversible digital transition and growing globalisation (OECD, 2019[14]). Highly skilled employees are more likely to perform complex tasks that can drive firm competitiveness and productivity growth (Acemoglu, 2002[72]). Empirical studies converge in fact towards a mutually reinforcing relationship between workforce skills, and innovation and productivity (Marchese et al., 2019[20]). Skilled employees are also vital for technology and innovation absorption, as well as breaking into new markets, or for adapting to organisational change during phases of transitions such as growth or exporting for the first time (OECD, 2015[73]). Improving the skills of workers can also strengthen SME position in GVCs by enabling specialisation and integration in high value-added activities (e.g. technologically-advanced industries, complex business services (OECD, 2017[74]). Incidentally, many business surveys identify access to workforce skills as a key constraint to firm growth (Siepel, Cowling and Coad, 2017[75]).

In addition, scaling up and high growth require leadership and management skills to cope with the disruptive transformation process firms are going through, and that can alter their organisational dynamics (OECD, 2010[76]). SME founders usually have specific expertise, while growth often requires an expanded skillset to address the emerging complexities: from commercial (e.g. marketing and serving of new offers), to project management (e.g. logistics, organisations of events), financial (e.g. capital and cash flow management) and strategic thinking (e.g. building internal leadership, coordinating sets of actions to fulfil new strategic objectives) (OECD, 2019[66]). Several studies argue that growth capabilities are largely shaped by leadership and management capability development upstream (Koryak et al., 2015[77]).

Intangible assets

Investment in intangible assets, such as computerised information, innovative property and economic competencies, has grown significantly with the rise of the knowledge- and data-driven economy (Andrews and Criscuolo, 2013[78]) (OECD, 2015[79]). As innovation turned more incremental, open and non-technological, new opportunities arose for smaller actors to innovate, and non-physical “intangible” innovation assets have become central to their competitive edge, such as firm-specific skills and know-how, data and brands, copyrights, designs, patents, trademarks and other intellectual property rights (IPRs), algorithms, databases and software, organisational settings and processes, or business models and networks etc. (see Chapter 3). Accordingly, corporate investment in intangible assets has outstripped investment in traditional tangible assets, such as machinery and physical equipment, accounting for over 70% of firms’ value in the United Kingdom and the United States already in early 2010s. For example, it is estimated that data assets only cover nearly 40% of today’s intangible investment (Corrado et al., 2022[80]).

Incidentally, promoting IPRs can be instrumental for improving scalers access to growth finance. Beyond the benefits of efficient IPR law and enforcement systems for ensuring the appropriation of innovation benefits and incentivising risk taking, IPRs can help SMEs gain additional revenues (e.g. through licensing) and serve as collateral or guarantee for bank lenders and investors (OECD, 2015[81]).

Network expansion

SME capacity of building and expanding networks is determinant for their innovation and growth outlook. Networks can improve SMEs access to clients or partners, knowledge and talent, data and technology, or finance, and allow them to benefit from innovation spillovers that could help them transform processes and business models and scale up performance (OECD, 2019[14]). In fact, SMEs due to their more limited internal capacity tend to be more dependent on external sources of knowledge, and their integration into local, national and global innovation networks could help them capture knowledge spillovers. Strong networks are also a key attribute of successful entrepreneurial ecosystems and critical in stimulating and growing start-ups.

SME network expansion can take different forms, e.g., through their supply chains, in domestic and/or international markets, via cooperation and partnerships, or through the use of digital platforms. How they can influence SME capacity and opportunity to scale up can vary depending on the nature of the network.

Domestic market expansion

The domestic markets remain the prime space where SMEs do business and most of them start their expansion journey domestically (OECD, 2019[14]) (OECD, 2019[66]). SMEs are predominantly local actors embedded in nearby markets and ecosystems, and their business linkages act as channels for knowledge spillovers (OECD, 2018[82]). Firms engaged in buyer-supplier relationships can enter in collaborative arrangements for undertaking product innovation, for competition or internationalisation purposes or for workforce training. Collaboration with customers can also be a channel, especially as SMEs tend to enjoy close relationships with end-users and better understanding of near-by market (OECD, 2019[14]).

In particular, public procurement offers considerable opportunities for SMEs to expand business operations, innovate, and boost competitiveness. In 2019, public procurement amounted to close to 30% of government expenditures in the OECD area and about 13% of GDP (OECD, 2021[83]). Through their significant procurement of very diverse goods and services (equipment and supplies, maintenance and repairs, energy, ICT, consulting, etc.) and the commissioning of services provided directly to consumers, national and subnational governments creates scope for engagement with small-scale local specialist providers, while also offering relative stability in demand, security of payment and spill-overs that might accrue through accreditation and recognition of being a supplier to government (e.g. for customer base expansion, or for negotiating other contracts and financing) (OECD, 2019[14]).

International trade

Scalers increase their global market presence, in some cases exporting (OECD, 2021[2]). Stronger participation by SMEs in global markets creates opportunities to scale up, by opening new markets, facilitating access to foreign technology and managerial know-how and creating spill-overs during the interactions along the value chains, broadening and deepening the skillset, and accelerating innovation.

SMEs integrate into GVCs as direct exporters (trading), upstream suppliers of exporting firms (supplying) or importers of foreign inputs and technologies (sourcing) (OECD, 2019[14]). GVCs, in particular, offer new opportunities for SMEs to specialise within production networks, rather than compete along the entire line of activities, which gives an edge to smaller actors. In turn, value creation within GVC results from the low replicability of products, i.e. firms’ capability to innovate and differentiate their output (OECD, 2013[84]) (Kaplinsky and Morris, 2002[85]).

Cooperation and partnerships

As SMEs draw on external economies of scale for increasing performance, collaboration, strategic partnerships, or alliances play a key role for scaling up. Collaborative arrangements are set up for multiple purposes, e.g. for sharing business risks, accessing and pooling resources, managing joint innovation activities, combining forces for commercialisation and marketing, or simply sharing knowledge and information (OECD, 2019[14]). For instance, a frequent way for SMEs to access global markets and improve global competitiveness is to establish alliances through business linkages or trade associations.

SME cooperation partnerships can involve (other) small and large firms, competitors and customers, domestic firms and multinationals, as well as knowledge providers, such as universities. This plurality reflects the multiplicity of actors engaged in business and knowledge networks, that generate (suppliers), distribute (intermediaries) and use (users) knowledge, serving multiple functions into knowledge networks and turning knowledge transfers into multidirectional and multidimensional flows (Kergroach, 2020[86]).

Digital platforms

An online platform is a digital service that facilitates interactions between two or more distinct but interdependent sets of users (whether firms or individuals) who interact through the service via the internet” (OECD, 2019[87]). Online platforms are very heterogeneous in their functionalities, structures and in the services they offer, and SMEs can carry out numerous key business functions by using them, such as marketing, advertising, branding, customer services and external communication (e.g. Google, Facebook), e-commerce and online marketplaces (e.g. Amazon, e-Bay), service delivery (e.g. Deliveroo, Uber, Airbnb) , financing and payment (e.g. PayPal), remote working and teleconferencing (e.g. Zoom), or for R&D, design and exploration (e.g. GitHub) (OECD, 2021[59]).

Digital platforms are instrumental in SME network expansion and provide important channels for SME growth. They enable greater access to new markets, sourcing channels and a multitude of digital networks. They provide scope for efficiencies that can drive economies of scale, leverage network effects, and, in turn, boost competitiveness and productivity (OECD, 2021[59]).

A central feature of online platforms relates to their ability to generate and deliver network effects, which make them particularly attractive for SMEs. Network effects imply that the usefulness of multi-side platforms is directly correlated to the size of their user-base (OECD, 2019[87]), the larger, the more likely to find a match (e.g. with service providers, suppliers, clients) and to reduce transaction costs and information asymmetry. A case in point are online marketplaces, where ancillary services such as review and rating systems, platform insurance on purchases and refunds, as well as guarantees on delivery times and logistic, greatly increase the trust of consumers, making it more likely for an SME to be able to sell to them via the platform than through its own app/website (OECD, 2021[59]).

However, not all digital platforms are likely to drive SME growth to the same extend and the growth of all types of businesses the same way. The platform economy embeds for instance the gig platforms which matches workers, most often self-employed, to customers (final consumers or businesses) on a per-service or per-task (“gig”) basis. These platforms, if they allow SMEs on the demand-side to reduce labour costs through increased employment flexibility and easier connection with specialised workers, appear more as a substitution solution to traditional self-employment or an income complement for own-account workers (Schwellnus et al., 2019[88]), with limited scope for growth on this side of the market, In addition, gig platforms remain few and have mainly grown in a small number of services such as personal transport and services and crafts.

Multiplier effects of scaling up drivers

Scaling up drivers are in fact highly interconnected and mutually reinforcing, and scalers almost always combine these drivers as they embark on their transformation journey, even though some drivers may play a more dominant role at certain stages (Table 1.3) (OECD, 2021[2]).

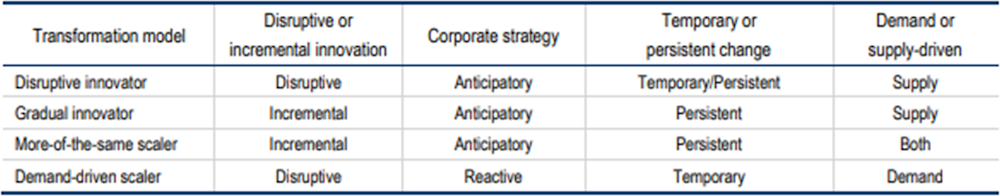

Table 1.3. Scaler profiles, scale up drivers and trajectories

|

Transformation model |

Measurable dynamic differences from peers |

Scaling up drivers at play |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Before scaling up |

During scale up (and after) |

Permanent differences |

||||

|

Disruptive innovator The firm develops technological innovation that translates into a competitive advantage. |

|

|

More workforce diversity

|

Sudden transformation due to new products or services that provide a competitive advantage, incl. e.g.

|

|

|

|

Gradual innovator The firm invests in human capital and new production processes to become more productive than its peers and gain market shares |

|

|

|

Gradual transformation, which requires accessing external capital (e.g. equity or bank credit) for investments in physical, human (and intangible) capital, i.e. for

|

|

|

|

Demand-driven scaler The firm faces an exogenous and temporary increase in demand. |

Higher debt Higher wage premium More workforce diversity More low-educated and low-skilled workers Higher share of current assets |

Unexpected increase in (local or international demand for a good or a service might be driven by improved access to supply chain partners or business networks To expand production and respond to the temporal increase in demand, the firm may need to invest in

Can result in further market expansion (domestically or internationally) |

|

|||

|

More-of-the-same scaler The firm scales by producing additional output using the same business model |

Lower productivity and profitability

|

|

Need for significant upfront investment, e.g. for new facilities or for building a second production line, as well as hire new staff to match expansion in production. |

|

||

Source: Authors’ own elaboration, based on (OECD, 2021[2]).

Innovation, as a start, is a case in point, as it requires investments and accessing networks.

1. Innovation remains strongly linked to multiple forms of investment, as it results from a process of knowledge and capital accumulation, whereby firms create, acquire, and recombine innovation assets which allows them to design and introduce new products, services, or processes (OECD, 2019[14]). To do so, firms typically need to invest in a combination of physical capital (e.g. technology, machinery and equipment), skills (e.g. firm-specific skills and know-how, new IT skills), as well as a range of intangible innovation assets (e.g. data and brands, organisational settings and processes, or business models and networks).

2. Digital adoption, for instance, not only implies investments in technical equipment such as hardware or software, but requires complementary investments in organisational changes and skills (e.g. training) to be effective. Moreover, existing evidence strongly suggests that for digital adoption to “pay off”, there is a need for digital skills to be diffused more widely across employees and managers and not be limited to ICT specialists (OECD, 2021[59]).

Likewise, firms almost never innovate in isolation and networks of innovation involving multiple actors are the rule rather than the exception (DeBresson, 1996[89]). SMEs therefore need access to relevant networks to source relevant knowledge, skills or equipment, and smaller firms in particular are more dependent on external knowledge obtained either through partnerships or spillovers (Love and Roper, 2015[90]). In this context, open innovation has brought about a paradigm shift whereby business efforts are no longer confined to corporate R&D labs but increasingly emerge through collaborative efforts between business partners that interact, exchange knowledge and information and share standards and infrastructure, thus facilitating access to multiple innovation assets and making the innovation endeavour also more accessible to SMEs (OECD, 2010[91]).New forms of innovation can reduce SME growth investment needs and increase their networking capacity.

1. The rise of digital platforms has partially remedied to SME investment needs, e.g. by enabling new models of knowledge sourcing and providing SMEs with greater access to a larger portfolio of innovation assets at reduced cost. Cloud computing for instance offers new solutions for SMEs to upgrade their IT systems without incurring upfront investment in hardware, and maintenance costs afterwards (OECD, 2021[59]).

2. The commercialisation of IPRs, i.e. formalised results of R&D and innovation, can create additional revenues, or serve as collateral or guarantee for bank lenders and investors, reducing needs for financial capital.

3. Aside from accelerating internal innovation, opening innovation has increasingly been seen as a way for expanding the markets for external use of innovation (Chesbrough, 2003[92]), with the phenomenon taking place at a much faster pace than in the past (Gassmann and Enkel, 2004[93]).

4. There is also a considerable body of empirical literature suggesting a positive link between innovation and exporting (Love and Roper, 2015[90]). SMEs which have a track record of innovation are more likely to export, more likely to export successfully and more likely to generate growth from exporting than non-innovating firms. (Wright et al., 2015[94]). Digital adoption in particular has greatly increased SME opportunities for business expansion abroad through a digitally-enabled access to international buyers, value chain partners and previously unreachable geographic markets (OECD, 2018[82]).

SMEs can source all forms of capital through various networks, and expand their networks with their capital stock.

1. Participation in GVCs create opportunities for SMEs to absorb spill-overs of technology and knowledge, and increase physical, human and intangible capital (OECD, 2008[33]) (OECD, 2019[14]) (OECD, 2022[95]).

2. Participation in GVCs can also provide SMEs with access to a broader range of financing instruments. This can include short-term trade finance instruments that enable deferred payment (e.g. intra-firm or inter-firm financing), as well as more dedicated tools such as letters of credit, advance payment guarantees, performance bonds, and export credit insurance or guarantees. (OECD, 2021[96]) (OECD, 2021[97]). In addition, medium- and long-term export financing instruments (e.g. buyer credits) are increasingly used as supply chain solutions for financing capital equipment. These instruments typically require longer repayment periods, with greater impact on SME scale up potential, as they enable investment in productive capital and network expansion.

3. The rise of industry, marketplace and crowdsourcing platforms has been instrumental for increasing SME access to strategic resources (finance, skills and innovation assets). Online platforms for instance enable better system interoperability and data sharing (OECD, 2017[60]), and they provide access to software, technology or data and databases (e.g. through cloud computing services), ideas and solutions (e.g. through crowdsourcing and collaborative platforms on specialised software solutions), user and client data (e.g. through e-commerce platforms) (OECD, 2019[14]) (OECD, 2021[59]).

4. In turn, there is particularly strong evidence on the importance of investments in skills and capital in fostering SME exports, as well as access to liquidity and R&D (Wright et al., 2015[94]).

5. In addition, investments in intangible assets can help SMEs open up new segments in markets and position more competitively vis-à-vis large enterprises. IPRs can provide an important signal for attracting customers and enticing venture capital investments (Holgersson, 2013[98]).

6. IPRs and their enforcement can create a sound competition environment and secure foreign direct investment with potential for building stronger innovation linkages with domestic SMEs, either through value chains or cooperation agreements (OECD forthcoming, 2022[99]).

Scaling up drivers are complementary and mutually reinforcing, marked by significant overlaps and interdependencies, that suggest the existence of virtuous – or vicious – circles in scaling up dynamics. The intertwining of scaling up drivers inevitably raises complexity for policy makers seeking to promote SME scaling up and presupposes the emergence of a dense nexus of interactions within the scale up policy mix.

Rethinking SME scale up policies